Submitted:

11 December 2024

Posted:

11 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

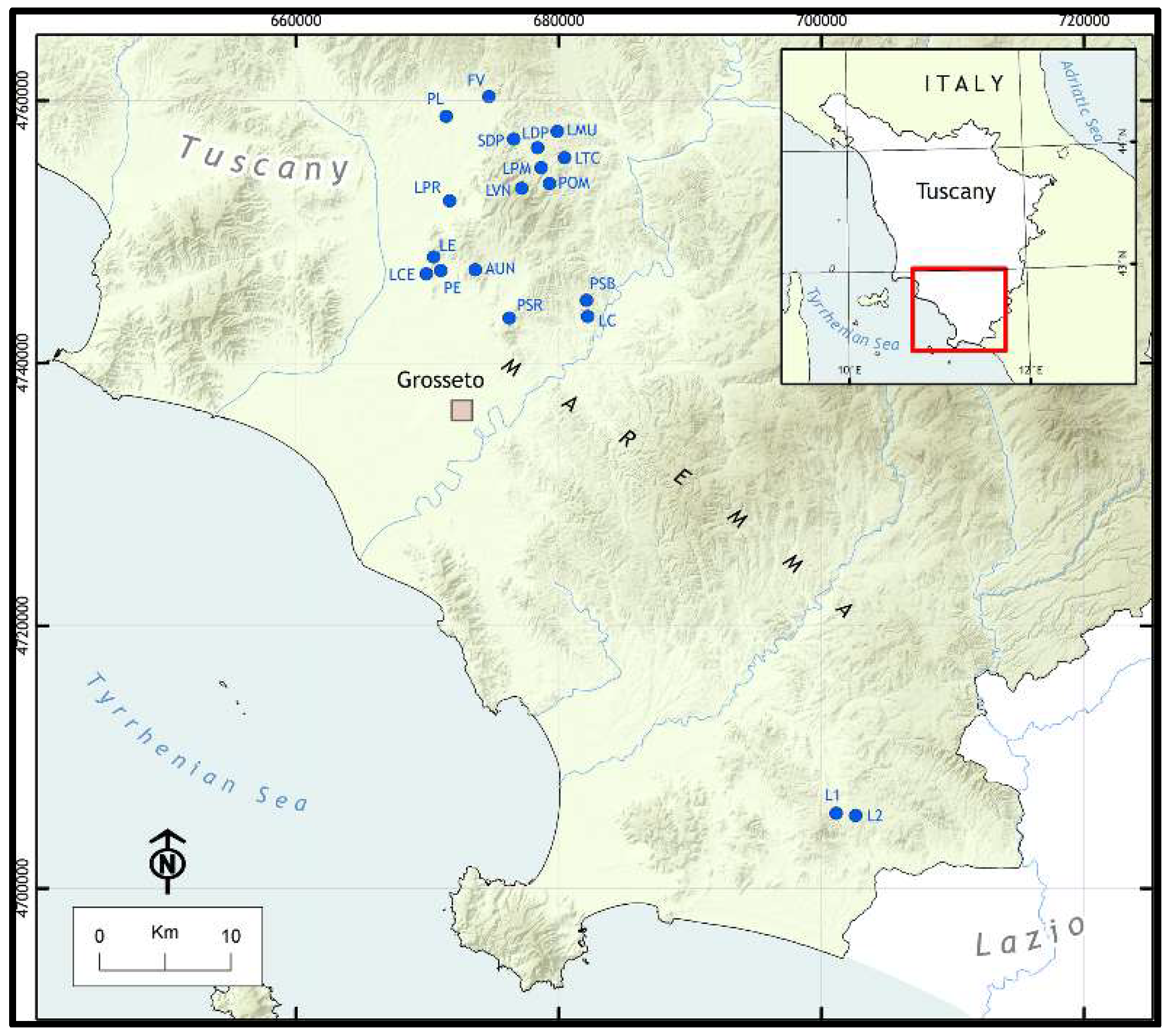

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Climate and Bioclimate

2.3. Geological Outline

2.4. Data Set and Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion and Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Dudgeon, D.; Arthington A.H., Gessner M.O.; Kawabata, Z., Knowler, D.J.; Lévêque, C., et al. Freshwater biodiversity: importance, threats, status and conservation challenges. Biological Reviews 2006, 81, 163–182. [CrossRef]

- De Groot, R.; Brander, L.; Van Der Ploeg, S.; Costanza, R.; Bernard, F.; Braat, L.; Christie, M.; Crossman, N.; Ghermandi, A.; Hein, L.; et al. Global estimates of the value of ecosystems and their services in monetary units. Ecosyst Serv. 2012, 1, 50–61. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.L.; Yin, J.X.; Jiang, Y.Z.; Wang, H. Relationship between the hydrological conditions and the distribution of vegetation communities within the Poyang lake national nature reserve, China. Ecological Informatics 2012, 11, 65–75. [CrossRef]

- Mitsch, W.J.; Bernal, B.; & Hernandez, M.E. Ecosystem services of wetlands. International Journal of Biodiversity Science, Ecosystem Services & Management 2015, 11(1), 1-4. [CrossRef]

- Gardner, R.C.; Barchiesi, S.; Beltrame, C.; Finlayson, C.M.; Galewski, T.; Harrison, I.; Paganini, M.; Perennou, C.; Pritchard, D.E.; Rosenqvist, A.; Walpole, M. State of the World’s Wetlands and their Services to People: A compilation of recent analyses. Ramsar Briefing Note no. 7; Switzerland: Ramsar Convention Secretariat, Gland, Swiss, 2015.

- Acreman, M.; Hughes, K. A.; Arthington, A. H.; Tickner, D.; Dueñas, M. A. Protected areas and freshwater biodiversity: A novel systematic review distils eight lessons for effective conservation. Conservation Letters 2020, 13(1). [CrossRef]

- Hrivnák, R.; Kochjarová, J.; Oťaheľová, H.; Paľove-Balang, P.; Slezák, M.; Slezák, P. Environmental drivers of macrophyte species richness in artificial and natural aquatic water bodies–comparative approach from two central European regions. Annales de Limnologie-International Journal of Limnology 2014, 50(4): 269–278. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, N.G.; Grillas, P.; Al Hreisha, H.; Balkız, Ö.; Borie, M.; Boutron, O.; ... & Sutherland, W.J. The future for Mediterranean wetlands: 50 key issues and 50 important conservation research questions. Regional environmental change 2021, 21, 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Ballut-Dajud, G.A.; Sandoval Herazo, L.C.; Fernández-Lambert, G.; Marín-Muñiz, J.L.; López Méndez, M.C.; Betanzo-Torres, E. A. Factors affecting wetland loss: A review. Land 2022, 11(3), 434. [CrossRef]

- Reid, A.J.; Carlson, A.K.; Creed, I.F.; Eliason, E.J.; Gell, P.A.; Johnson, P.T.; et al. Emerging threats and persistent conservation challenges for freshwater biodiversity. Biological Reviews 2019, 94(3), 849–873. [CrossRef]

- Fluet-Chouinard, E.; Stocker, B.D.; Zhang, Z.; Malhotra, A.; Melton, J.R.; Poulter, B.; ... & McIntyre, P.B. Extensive global wetland loss over the past three centuries. Nature 2023, 614(7947), 281-286. [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Weng, B.; Yan, D.; Wang, K.; Li, X.; Bi, W.; ... & Liu, Y. Wetlands of international importance: Status, threats and future protection. International journal of environmental research and public health 2019, 16(10), 1818. [CrossRef]

- Janssen, J.S., Rodwell, M.; Criado S.; Gubbay, T.; Haynes, A.; Nieto, N.; et al. European Red List of Habitats. Publications Office of European Union: Luxembourg, 2016. ISBN 978-92-79-61588-7. [CrossRef]

- Zivkovic, L.; Biondi, E.; Pesaresi, S.; Lasen, C.; Spampinato, G.; Angelini, P. The third report on the conservation status of habitats (Directive 92/43/EEC) in Italy: processes, methodologies, results and comments. Plant Sociology 2017 54(2), 51–64. [CrossRef]

- Gigante, D.; Acosta, A.T.R.; Agrillo, E.; Armiraglio, S.; Assini, S.; Attorre, F. et al. Habitat conservation in Italy: the state of the art in the light of the first European Red List of Terrestrial and Freshwater Habitats. Rendiconti Lincei. Scienze Fisiche e Naturali 2018, 29(2): 251–265. [CrossRef]

- Lazzaro, L.; Bolpagni, R.; Buffa, G.; Gentili, R.; Lonati, M.; Stinca, A. et al. Impact of invasive alien plants on native plant communities and Natura 2000 Habitats: state of the art, gap analysis and perspectives in Italy. Journal of Environmental Management 2020, 274, 111140 . [CrossRef]

- Viciani, D.; Vidali, M.; Gigante, D.; Bolpagni, R.; Villani, M.; Acosta, A.T.R. et al. A first checklist of the alien-dominated vegetation in Italy. Plant Sociology 2020, 57(1), 29–54. [CrossRef]

- Gennai, M.; Gabellini, A.; Viciani, D.; Venanzoni, R.; Dell’Olmo, L.; Giunti, M. et al. The floodplain woods of Tuscany: towards a phytosociological synthesis. Plant Sociology 2021, 58(1): 1–28. [CrossRef]

- Van den Broeck, M.; Waterkeyn, A.; Rhazi, L.; Grillas, P. & Brendonck, L. Assessing the ecological integrity of endorheic wetlands, with focus on Mediterranean temporary ponds. Ecological Indicators 2015, 54; 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Geijzendorffer, I.R.; Beltrame, C.; Chazee, L.; Gaget, E.; Galewski, T.; Guelmami, A.; ... & Grillas, P. A more effective Ramsar Convention for the conservation of Mediterranean wetlands. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 2019, 7, 21. [CrossRef]

- Fois, M.; Cuena-Lombraña, A. & Bacchetta, G. Knowledge gaps and challenges for conservation of Mediterranean wetlands: Evidence from a comprehensive inventory and literature analysis for Sardinia. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 2021, 31(9), 2621-2631. [CrossRef]

- Leberger, R.; Geijzendorffer, I.R.; Gaget, E.; Gwelmami, A.; Galewski, T.; Pereira, H.M.; Guerra, C.A. Mediterranean wetland conservation in the context of climate and land cover change. Regional Environmental Change 2020, 20, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Gallego-Fernandez, J.B.; García-Mora, M.R.; Garcia-Novo, F. Small wetlands lost: a biological conservation hazard in Mediterranean landscapes. Environmental Conservation 1999, 26(3), 190-199.

- De Meester, L.; Declerck, S.; Stoks, R.; Louette, G.; Van De Meutter, F.; De Bie, T.; ... & Brendonck, L. Ponds and pools as model systems in conservation biology, ecology and evolutionary biology. Aquatic conservation: Marine and freshwater ecosystems 2005, 15(6), 715-725. [CrossRef]

- Angiolini, C.; Viciani, D.; Bonari, G.; Zoccola, A.; Bottacci, A.; Ciampelli, P. et al. Environmental drivers of plant assemblages: are there differences between palustrine and lacustrine wetlands? A case study from the northern Apennines (Italy). Knowledge and Management of Aquatic Ecosystems 2019, 420, 34. [CrossRef]

- Viciani, D.; Angiolini, C.; Bonari, G.; Bottacci, A.; Dell’Olmo, L.; Gonnelli, V.; Zoccola, A.; Lastrucci L. Contribution to the knowledge of aquatic vegetation of montane and submontane areas of Northern Apennines (Italy). Plant Sociology 2022, 59(1), 25–35. [CrossRef]

- Lastrucci, L.; Angiolini, C.; Bonari, G.; Bottacci, A.; Gonnelli, V.; Zoccola, A.; Mugnai, M.; Viciani, D.; Contribution to the knowledge of marsh vegetation of montane and submontane areas of Northern Apennines (Italy). Plant Sociology 2023, 60(1), 25–36. DOI 10.3897/pls2023601/03.

- Perennou, C.; Gaget, E.; Galewski, T.; Geijzendorffer, I.; Guelmami, A. Evolution of wetlands in Mediterranean region. Water resources in the Mediterranean Region 2020, 297-320. [CrossRef]

- Lastrucci, L.; Foggi, B.; Selvi, F.; Becattini, R. Contributo alla conoscenza della vegetazione e della flora delle aree umide nel comprensorio di Capalbio (Provincia di Grosseto, Italia centrale). Archivio Geobotanico 2007, 10(1-2), 1-30.

- Lastrucci, L; Bonari, G; Angiolini, C; Casini, F; Giallonardo, T; Gigante, D. et al. Vegetation of Lakes Chiusi and Montepulciano (Siena, central Italy): updated knowledge and new discoveries. Plant Sociology 2014, 51(2), 29–55. [CrossRef]

- Lastrucci, L.; Ferretti, G.; Mantarano, N.; Foggi, B. Vegetation and habitat of conservation interest of the lake Acquato (Grosseto – Central Italy). Plant Sociology 2019, 56(1), 19–30. [CrossRef]

- Selvi, F. A critical checklist of the vascular flora of Tuscan Maremma (Grosseto province, Italy). Flora Mediterranea 2010, 20, 47-139.

- Giovacchini, P.; Falchi, V.; Vignali, S.; Radi, G.; Passalacqua, L.; Corsi, F.; Porciani, M.; Farsi, F. Atlante degli anfibi della provincia di Grosseto (2003-2013) Quaderni Volume n. 6 della Collana “Quaderni delle Aree Protette”; Provincia di Grosseto, 2015.

- Thornthwaite, C.W.; Mather, J. R. Instruction and tables for computing potential evapotraspiration and the water balance. Pubbl. Climatol. 1957, 10 (3): 1-311.

- Pesaresi, S.; Biondi, E.; Casavecchia, S. Bioclimates of Italy. Journal of Maps 2017, 13, 955–960. [CrossRef]

- Blasi, C.; Capotorti, G.; Copiz, R.; Guida, D.; Mollo, B.; Smiraglia, D.; Zavattero, L. Classification and mapping of the ecoregions of Italy. Plant Biosyst. 2014, 148(6), 1255–1345. [CrossRef]

- Gelmini, R. Ricerche geologiche nel Gruppo di M. Leoni (Grosseto; Toscana). I) La geologia di M. Leoni tra Montepescali e il fiume Ombrone. Mem. Soc. Geol. It. 1969, 8, 755-796.

- Lazzarotto, A. Elementi di Geologia. In: Giusti, F. (ed) La Storia Naturale della Toscana Meridionale; Pizzi editore: Siena, Italy, 1993; pp. 19-87.

- Aldinucci, M.; Brogi, A.; Sandrelli, F. The metamorphic units of the eastern side of Monte Leoni (Northern Apennines, Italy). Boll. Soc. Geol. It. 2005, 124, 313-332.

- Carmignani, L.; Conti, P.; Cornamusini, G.; Pirro, A. Geological map of Tuscany (Italy). Journal of Maps 2013, 9, 487–497. [CrossRef]

- Motta, S. Note Illustrative della carta geologica d’Italia; foglio 128 Grosseto; Servizio Geologico d’Italia, 1969.

- Selvi, F.; Stefanini, P.; Biotopi naturali e aree protette nella Provincia di Grosseto. Componenti floristiche e ambienti vegetazionali. Città di Castello; TipoLitografia Petruzzi Provincia di Grosseto: Città di Castello, Italy, 2006.

- Braun-Blanquet, J. Plant sociology: The study of plant communities; McGraw-Hill: New York, United States, 1932.

- Braun-Blanquet, J. Pflanzensoziologie. Grundzüge der Vegetationskunde; Springer, 3rd ed.: Wien, Austria, 1964; pp. 1–330.

- Dengler, J.; Berg, C.; Jansen, F. New ideas for modern phytosociological monographs. Ann. Bot. (Roma) 2005, 5, 193–210.

- Dengler, J.; Chytrý, M.; Ewald, J. Phytosociology in Jørgensen, S.E.; Fath, B.D.; Encyclopedia of Ecology, Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2008; pp. 2767–2779.

- Biondi, E. Phytosociology today: Methodological and conceptual evolution. Plant Biosyst. 2011, 145 (Suppl. S1), 19–29. [CrossRef]

- Pott, R. Phytosociology: A modern geobotanical method. Plant Biosyst. 2011, 145 (Suppl. S1), 9–18. [CrossRef]

- Van der Maarel, E. Transformation of cover-abundance values in phytosociology and its effects on community similarity. Vegetatio 1979, 39, 97–114.

- Arrigoni, P.V. A classification of plant growth forms applicable to the floras and vegetation types of Italy. Webbia 1996, 50(2), 193-203.

- R Core Team -2024 R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna; Austria. URL https://www.R-project.org/.

- Oksanen, J.; Blanchet, F.G.; Friendly, M.; Kindt, R.; Legendre P.; McGlinn D. et al. 2024 Vegan: Community Ecology Package. R package version 2.6-6.1. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan.

- Portal to the Flora of Italy 2024 [accessed 2024 Sep] http://dryades.units.it/floritaly.

- Bartolucci, F.; Peruzzi, L.; Galasso, G.; Alessandrini, A.; Ardenghi, N.M.G.; Bacchetta, G.; Banfi, E.; Barberis, G.; Bernardo, L.; Bouvet, D.; Bovio, M.; Calvia, G.; Castello, M.; Cecchi, L.; Del Guacchio, E.; Domina, G.; Fascetti, S.; Gallo, L.; Gottschlich, G.; Guarino, R.; Gubellini, L.; Hofmann, N.; Iberite, M.; Jiménez-Mejías, P.; Longo, D.; Marchetti, D.; Martini, F.; Masin, R.R.; Medagli, P.; Peccenini, S. et al. A second update to the checklist of the vascular flora native to Italy. Plant Biosyst. 2024, 158(2), 219–296. [CrossRef]

- Mucina, L.; Bültmann, H.; Dierßen, K.; Theurillat, J.P.; Raus, T.; Čarni, A. et al. Vegetation of Europe: hierarchical floristic classification system of vascular plant, bryophyte, lichen, and algal communities. Applied Vegetation Science 2016, 19(suppl. 1), 3–264. [CrossRef]

- Biondi, E.; Blasi, C. 2015 Prodromo della Vegetazione Italiana. [accessed 2024 Sept] http://www.prodromo-vegetazione-italia.org/.

- Theurillat, J.P.; Willner, W.; Fernández-González, F.; Bültmann, H.; Čarni, A.; Gigante, D. et al. International Code of Phytosociological Nomenclature. 4th edition. Applied Vegetation Science 2021, 24, e12491. [CrossRef]

- Bazzichelli, G.; Abdelahad, N.; Alghe d’acqua dolce d’Italia. Flora analitica delle Caroficee - Ministero dell’Ambiente, Università degli Studi di Roma La Sapienza; Centro Stampa Università: Rome, Italy, 2009.

- Mangeat, M.; Contribution à la connaissance de la Characée Nitella hyalina (De Candolle) C. Agardh, 1824, dans le nord-est de la France. Les Nouvelles Archives de la Flore jurassienne et du nord-est de la France 2014, 12, 48-61.

- Csiky, J.; Purger, D.; Blaženčić, J. New occurrence and distribution of Nitella hyalina (DC .) Agardh (Characeae) and the first report on Nitelletum hyalinae Corillion 1957, in Croatia. Arch. Biol. Sci. 2014, 66(1), 203-208. [CrossRef]

- Šumberová, K. Vegetace volně plovoucích vodních rostlin (Lemnetea). Vegetation of free floating aquatic plants. In: Chytrý M. Ed.); Vegetace České republiky 3 Vodní a mokřadní vegetace. [Vegetation of the Czech Republic 3 Aquatic and wetland vegetation]; Academia: Praha, Czech Republic, 2011; pp. 43–99.

- Šumberová K. Vegetace vodních rostlin zakořeněných ve dně (Potametea). Vegetation of aquatic plants rooted in the bottom. In Chytrý M. (Ed.). Vegetace České republiky 3 Vodní a mokřadní vegetace. [Vegetation of the Czech Republic 3 Aquatic and wetland vegetation]. Academia: Praha, Czech Republic, 2011; 100-247.

- Hrivnák, R.; Aquatic plant communities in the catchment area of the Ipel' river in Slovakia and Hungary. Part II. Class Potametea. Thaiszia 2002, 12, 137-160.

- Lastrucci, L.; Landucci, F.; Gonnelli, V.; Barocco, R.; Foggi, B.; Venanzoni, R. The vegetation of the upper and middle River Tiber (Central Italy). Plant Sociology 2012, 49(2), 29-48. DOI: 10.7338/pls2012492/02.

- Landucci, F.; Gigante, D.; Venanzoni, R. An application of the Cocktail method for the classification of the hydrophytic vegetation at Lake Trasimeno (Central Italy). Fitosociologia 2011, 48(2), 3-22.

- Brullo, S.; Scelsi, F.; Spampinato, F. La vegetazione dell’Aspromonte. Laruffa Editore: Reggio Calabria, Italy, 2001.

- Tardella, F.M.; Di Agostino, V.M. Vegetation of the "Altipiani di Colfiorito" wetlands (central Apennines, Italy). Plant Sociology 2020, 57(2), 113-132. [CrossRef]

- Sburlino, G.; Tomasella, M.; Oriolo, G.; Poldini, L.; Bracco, F. La vegetazione acquatica e palustre dell'Italia nord-orientale. 2 – La classe Potametea Klika in Klika et V. Novák 1941. Fitosociologia 2008, 45(2), 3-40.

- Caldarella, O.; Lastrucci, L.; Bolpagni, R.; Gianguzzi, L. Contribution to the knowledge of Mediterranean wetland vegetation: Lemnetea and Potamogetonetea classes in Western Sicily. Plant Sociology 2021, 58(1), 107–131. [CrossRef]

- Felzines, J.C.; Contribution au prodrome des végétations de France: les Potametea Klika in Klika & V. Novák 1941. Doc. Phytosoc 2016, série 3, 3, 218-437.

- Passarge, H.; Mitteleuropäische Potamogetonetea I. Phytocoenologia 1992, 20(4), 489-527.

- Lastrucci, L.; Saiani, D.; Mugnai, A.; Ferretti, G., Viciani, D. Distribution novelties of the genus Callitriche (Plantaginaceae) in Italy from the study of the Herbarium Centrale Italicum collections. Mediterr. Bot. 2024, 45(2); e87474. [CrossRef]

- Brullo, S., Minissale, P. Considerazioni syntassonomiche sulla classe Isoëto-Nanojuncetea. Itinera Geobotanica 1998, 11, 263–290.

- Gigante, D.; Maneli, F.; Venanzoni, R. Mediterranean temporary wet systems in inland Central Italy: ecological and phytosociological features. Plant Sociology 2013, 50(2), 93-112. [CrossRef]

- Lastrucci, L.; Foggi, B.; Gonnelli, V.; Gusmeroli, E.; La vegetazione delle aree umide dei substrati ultramafici dell’Alta Valtiberina (Arezzo; Italia centrale). Studia Botanica 2006, 24 (2005), 9-44.

- Rivas-Martínez, S.; Costa, M.; Castroviejo, S.; Valdés, E. Vegetación de Doñana (Huelva, España). Lazaroa 1980, 2, 5-189.

- Lastrucci, L.; Viciani, D.; Nuccio, C.; Melillo, C. Indagine vegetazionale su alcuni laghi di origine artificiale limitrofi al Padule di Fucecchio (Toscana, Italia Centrale). Ann. Mus. Civ. Rovereto 2008, 23(2007), 169–203.

- Dítě, D.; Eliáš, P. Jr.; Dítě, Z.; Šimková, A. Recent distribution and phytosociological affiliation of Ludwigia palustris in Slovakia. Acta Soc Bot Pol. 2017, 86(1), 3544. [CrossRef]

- De Foucault, B.; Contribution au prodrome des végétations de France: les Littorelletea uniflorae Braun-Blanq. & Tüxen ex Westhoff, Dijk, Passchier & Sissingh 1946. J. Bot. Soc. Bot. France 2010, 52, 43-78.

- Wattez, J.R.; Gehu, J.M. Groupements amphibies acidoclines relictuels ou disparus du nordde la France. Doc. Phytosociol. 1982, N.S. 6, 263-278.

- Dierssen, K.; Die Vegetation des Gildehauser Venns (Kreis Grafschaft Bentheim). Beih. Ber. Naturhist. Ges. 1973, 8, 1-120.

- Passarge, H. Pflanzengesellschaften Norostdeutschlands 2 II. Helocyperosa uns Caespitosa. J. Cramer in der Gebrüder Borntraeger Verlagsbuchhandlung: Berlin, Stuttgart, Germany, 1999; 451 pp.

- Landucci, F.; Gigante, D.; Venanzoni, R.; Chytrý, M. Wetland vegetation of the class Phragmito-Magno-Caricetea in central Italy. Phytocoenologia, 2013, 43, 67–100. [CrossRef]

- Landucci, F.; Šumberová, K.; Tichý, L.; Hennekens, S.; Aunina, L.; Biță-Nicolae, C. et al. Classification of the European marsh vegetation (Phragmito-Magnocaricetea) to the association level. Applied Vegetation Science 2020, 23, 297–316. [CrossRef]

- Lastrucci, L.; Lazzaro, L.; Coppi, A.; Foggi, B.; Ferranti, F.;Venanzoni, R.; Cerri, M.; Ferri, V.; Gigante, D.; Reale, L. Demographic and macro-morphological evidence for common reed dieback in central Italy. Plant Ecology & Diversity 2017, 10, 2-3, 241-251. [CrossRef]

- Lastrucci, L.; Cerri, M.; Coppi, A.; Ferranti, F.; Ferri, V.; Foggi, B. et al. Understanding common reed die-back: a phytocoenotic approach to explore the decline of palustrine ecosystems. PlantnSociology 2017, 54(2) Suppl.1, 15–28. [CrossRef]

- Venanzoni, R.; Properzi, A.; Bricchi, E.; Landucci, F.; Gigante, D. The Magnocaricetalia Pignatti 1953 (Phragmito-Magnocaricetea Klika in Klika et Novák 1941) Plant Communities of Italy. In: Pedrotti, F. (ed.) Climate Gradients and Biodiversity in Mountains of Italy, Geobotany Studies. Springer International Publishing, 2018, 135-173.

- Lastrucci, L.; Gambirasio, V.; Prosser, F.; Viciani, D. First record of Sparganium oocarpum in Italy and new regional distribution data for S. erectum species complex. Plant Biosyst. 2024, 158 (4). [CrossRef]

- Stančić, Z. Marshland vegetation of the class Phragmito-Magnocaricetea in Croatia. Biologia 2007, 62, 297-314. [CrossRef]

- Biondi, E.; Bagella, S. Vegetazione e paesaggio vegetale dell’arcipelago di La Maddalena (Sardegna nord-orientale). Fitosociologia 2005, 42(2) suppl.1, 3-99.

- Venanzoni, R., Gigante, D. Contributo alla conoscenza della vegetazione degli ambienti umidi dell’Umbria (Italia). Fitosociologia 2000, 37 (2), 13–63.

- Hrivnák, R.; Spoločenstvá zväzu Oenanthion aquaticae v povodí rieky Ipeľ [The plant communities of Oenanthion aquaticae in the catchment area of the river Ipeľ]. Bull. Slov. Bot. Spoločn 2003, 25, 169 – 183.

- Di Natale, S.; Lastrucci, L.; Hroudova, Z.; Viciani D. A review of Bolboschoenus species (Cyperaceae) in Italy based on herbarium data. Plant Biosyst. 2022, 156(1), 261–270. [CrossRef]

- Biondi, E.; Casavecchia, S.; Raketic, Z. The guazzi vegetation and the plant landscape of the alluvial plane of the last stretch of the Musone River (Central Italy). Fitosociologia 2002, 39(1), 45-70.

- Biondi, E.; Baldoni, M.; La vegetazione del fiume Marecchia (Italia Centrale). Biogeographia 1994, 17, 51-87.

- Biondi, E.; Vagge, I.; Baldoni, M.; Taffetani, F. La vegetazione del Parco Fluviale Regionale del Taro (Emilia Romagna). Fitosociologia 1997, 34, 69-110.

- Rivas-Martínez, S.; Fernández–González; F., Loidi, J.; Lousã, M.; Penas, Á. Syntaxonomical Checklist of vascular plant communities of Spain and Portugal to association level. Itinera Geobotanica 2001, 14, 5-341.

- Rivas-Goday, S. Contribución al conocimiento del Schoenetum nigricantis de Vasconia. Bol. Real Soc. Esp. Hist. Nat. 1945, 43, 261-273.

- Lastrucci, L.; Paci, F.; Raffaelli, M. The wetland vegetation of the Natural Reserves and neighbouring stretches of the Arno river in the Arezzo province (Tuscany; Central Italy). Fitosociologia 2010, 47(1), 29–59.

- Lastrucci, L.; Foggi, B.; Mantarano, N.; Ferretti, G.; Calamassi, R.; Grigioni, A. La vegetazione del laghetto “Lo Stagnone” (Isola di Capraia; Toscana). Atti Soc. Tosc. Sci. Nat.; Mem. Ser. B 2010, 116 (2009), 17–25.

- Tomei, P.E.; Guazzi, E. Le zone umide della Toscana; lista generale delle entità vegetali. Atti Mus. Civ. St. Nat. Grosseto 1993, 15, 107-152.

- Tomei, P.E.; Guazzi, E.; Kugler, P.C. Le zone umide della Toscana: indagine sulle componenti floristiche e vegetazionali. Ed. Regione Toscana: Firenze, Italy, 2001; pp. 167.

- Selvi, F. Flora vascolare del Monte Leoni (Toscana Meridionale). Webbia 1998, 52, 265-306.

- European Commission -1992 Council Directive 92/43/EEC of 21 May 1992 on the conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora. Off J Eur Union 206, 7–50.

- European Commission -2013 Interpretation Manual of European Union Habitats - Version EUR 28; April 2013 European Commission DG-ENV; Brussels; 146 pp.

- Evans, D. The habitats of the European Union Habitats Directive. Biology and Environment. Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy 2006, 106, 167–173.

- Evans, D. Interpreting the habitats of Annex I. Past, present and future. Acta Botanica Gallica 2010, 157, 677–686.

- Biondi, E.; Blasi, C.; Burrascano, S.; Casavecchia, S.; Copiz, R.; Del Vico, E. et al. Manuale Italiano di interpretazione degli habitat della Direttiva 92/43/CEE. Società Botanica Italiana. Ministero dell’Ambiente e della Tutela del Territorio e del Mare, 2009; http://vnr.unipg.it/habitat.

- Biondi, E.; Burrascano, S.; Casavecchia, S.; Copiz, R.; Del Vico, E.; Galdenzi, D. et al. Diagnosis and syntaxonomic interpretation of Annex I Habitats (Dir. 92/43/EEC) in Italy at the alliance level. Plant Sociology 2012, 49(1), 5-37. [CrossRef]

- Bunce, R.G.H.; Bogers, M.M.B.; Evans, D.; Halada, L.; Jongman, R.H.G.; Mücher, C.A.;…Olsvig-Whittaker, L. The significance of habitats as indicators of biodiversity and their links to species. Ecological Indicators 2013, 33, 19–25. [CrossRef]

- Gigante, D.; Foggi, B.; Venanzoni, R.; Viciani, D.; Buffa, G. Habitats on the grid: The spatial dimension does matter for red-listing. Journal for Nature Conservation 2016, 32, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Viciani, D.; Dell’Olmo, L.; Ferretti, G.; Lazzaro, L.; Lastrucci, L.; Foggi, B. Detailed Natura 2000 and Corine Biotopes habitat maps of the island of Elba (Tuscan Archipelago; Italy). Journal of Maps 2016, 12(3), 492–502. [CrossRef]

- Viciani, D.; Dell’Olmo, L.; Foggi, B.; Ferretti, G.; Lastrucci, L. & Gennai, M. Natura 2000 habitat of Mt. Argentario promontory (southern Tuscany; Italy). Journal of Maps 2018, 14(2), 447-454. [CrossRef]

- Angiolini, C.; Viciani, D.; Bonari, G.; Lastrucci, L. Habitat conservation prioritization: A floristic approach applied to a Mediterranean wetland network. Plant Biosyst. 2017, 151(4), 598–612. [CrossRef]

- Casavecchia, S.; Allegrezza. M.; Angiolini, C.; Biondi, E.; Bonini, F.; Del Vico, E. et al. Proposals for improvement of Annex I of Directive 92/43/EEC: Central Italy. Plant Sociology 2021, 58(2), 99–118. [CrossRef]

- Eckert, I.; Bruneau, A.; Metsger, D.A. et al. Herbarium collections remain essential in the age of community science. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7586. [CrossRef]

- Liu, D. World view. Nature, 2024, 633, 741 https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-024-03072-3.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).