1. Introduction

The sphagnum ecosystems, also known as sphagnets, raised bogs or peat lands, represent the vegetation sediment of non-aerated marshes consisting of carbonized remains belonging to avascular bryophytes of the genus

Sphagnum L., vascular cormoephytes of the genera

Carex L.,

Eriophorum L.,

Scheuchzeria L.,

Calluna Salisb.,

Epilobium L.,

Pedicularis L.,

Andromeda L.,

Empetrum L.,

Oxycoccus Hill,

Drosera L.,

Swertia L.,

Menyanthes L.,

Pinus L., in which the vegetative organs do not decompose, do not mineralize but become turbid due to acid to strongly acid pH (i.e. 4.5-5.2) forming deposit layers with peat thicknesses of up to 5.6 m in the Călățele-Beliș raised bog [

1], thicknesses of roughly 4 m, in the Dorna raised bog in the Gilău Mountains [

2], a peat thickness of 4.5 m in Molhașul cel Mare from Izbuc Padiș Plateau [

3], and a thickness of only 0.5-2 m in the slopes of Vârfuraș Mountains, Micău Mountain [

4].

Raised bog as ecosystem (habitat type) is the foundation of the oligotrophic-mesotrophic phytocenoses of the Carici echinatae-Sphagnetum association which was built by swamping the meadows of Nardus stricta L., Festuca rubra L., Deschampsia caespitosa (L.) P. Beauv., around the springs and the spruce forests located in intramontane depressions Valea Iadului valley – Poiana Remețului meadow at the altitude of 611 m, Făget Mountain plateaus at the altitude of 1,170 m, Moliviș Mountain at the altitude of 1,325 m, Vârfuraș Mountain subalpine plateau at the altitude of 1,590-1,602 m, Nimăiasa Mountain at the altitude of 1,545-1,579 m, on organic, very acidic soils-histosols, with a variable content of organic matter.

The ecosystems (habitats) of peat bogs in Romania were studied for the first time and published in a monographic work by Emil Pop, a Romanian botanist and academician [

1].

Brief scientific data on the sphagnum ecosystems (peatlands) in the Apuseni Mountains have been provided by the papers of various authors: Stâna de Vale Depression [

5], Valea Iadului valley – Poiana Remețului meadow [

6], Gilău Mountains-Someșul Rece, peatlands from Blajoaia and Dorna [

2], Bihor Mountains - Tinovul cel Mare raised bog from the source of Someșul Cald under Padiș Plateau [

7], Padiș Plateau, Barsa, Biserica Moțului peak, Piatra Arsă, Cuciulat [

8], Vlădeasa Massif in the sphagnets of Mount Micău, Mount Nimăiasa, Mount Vârfuraș [

4].

The purpose of this work is finding and describing the peat bogs phytocoenoses gathered in the Carici echinatae-Sphagnetum association (Balázs 1942) Soó 1955, from the raised bogs ecosystems spread over the Vlădeasa Massif, Western Carpathians.

The research outcomes aim at attaining some major objectives:

Finding the floristic composition of the vegetation, the biodiversity of the sphagnets and the classification of the species in a synthetic table of association by to their affinity to the coenotaxa, alliance, order and the class of vegetation to which they are subordinated;

Statistical analysis of the abundance-dominance and constancy of species in the structure of the living soil cover;

Ecological characterization of the cormoflora of the soil ecosystems in the light of the distribution of species by the type of bioform, phytogeographic element, by categories of the ecological indexes of edaphic moisture, air temperature and chemical reaction of the soil;

Highlighting the dynamics, development trend of the phytocoenoses of the ecosystem at a certain stage of life;

Economic and scientific capitalisation of the biotic and abiotic material elements of the ecosystem complex that characterizes the sphagnets;

Establishing the sustainable management of the ecosystems (habitats) of the sphagnum and the related measures necessary to maintain the favourable conservation status of the rare, vulnerable, critically endangered, threatened, relict, endemic species they shelter.

2. Materials and Methods

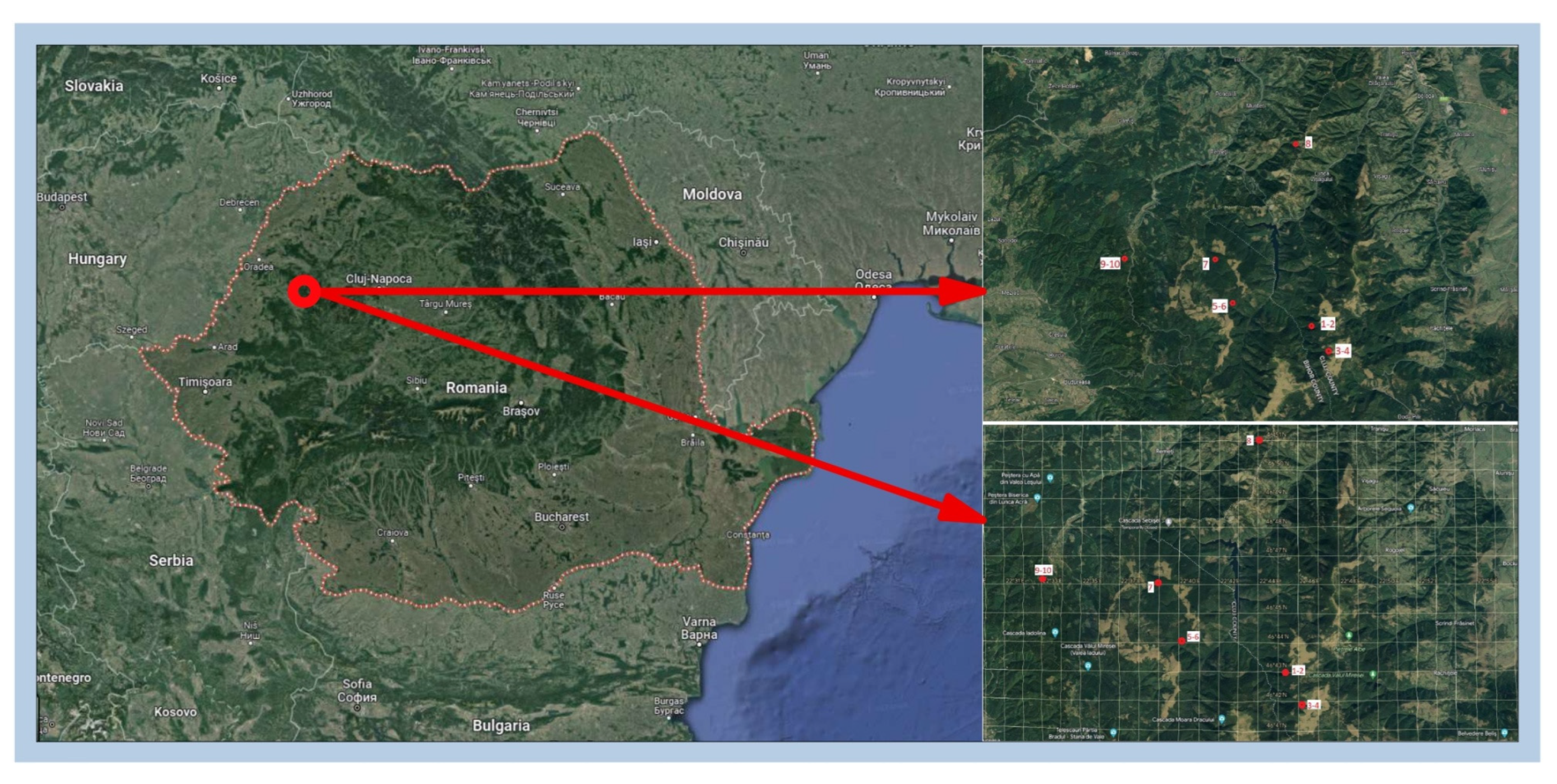

We conducted our research in the period 2020-2021 in the raised bogs of the Vlădeasa Massif, the Mount Vârfuraș site (latitude: 46°43’355’’N, longitude: 22°45’970’’ E; latitude: 46°43’293’’N, longitude: 22°45’799’’E), Mount Nimăiasa (latitude: 46°42’254’’N, longitude: 22°46’930’’E; latitude: 46°42’090’’N, longitude: 22°46’712’’E), Moliviș Mountain (latitude: 46°44’933’’N, longitude: 22°40’358’’E; latitude: 46°45’489’’N, longitude: 22°40’229’’E), Făget Mountain (latitude: 46°46’291’’N, longitude: 22°39’214’’E), Valea Iadului valley intramontane basin (latitude: 46°51’313’’N, longitude: 22°44’507’’E; latitude: 46°46’777’’N, longitude: 22°33’605’’E; latitude : 46°46’777’’N, longitude: 22°33’601’’E), in highlands between 0.5-2 ha, characterized by a humid and cool climate, with an average annual temperature of 0.9C°[

9].

Figure 1.

Map of the territory including the phytocenoses of the turbo-gleic meadows in the Western Carpathians.

Figure 1.

Map of the territory including the phytocenoses of the turbo-gleic meadows in the Western Carpathians.

The biological material consists in the communities of peat bogs plants belonging to the Carici echinatae-Sphagnetum association that develop in oligo-mesotrophic, mesotrophic-eutrophic bog ecosystems, explosively colonized by peat moss from the species Sphagnum recurvum P.Beauv., Sphagnum magellanicum Brid., Sphagnum angustifolium C.Jens., Sphagnum fuscum (Schimp) Klinggr., in alliance with boreal, circumpolar phanerogamous plants (Carex echinata Murray, Carex flava L., Carex lasiocarpa Ehrh., Carex rostrata Stokes, Eriophorum vaginatum L., Drosera rotundifolia L.), arctic-alpine (Juncus alpinoarticulatus Chaix, Hieracium aurantiacum L.), alpine-European (Epilobium nutans F.W. Schmidt, Homogyne alpina (L.) Cass.), alpine-Carpatho-Balkan (Senecio subalpinus W.D.J. Koch), Carpatho-Balkan ((Pedicularis limnogena A. Kern., Swertia punctata Baumg.), and hygrophilic and mesohygrophilic plants, on peat and gleic soils placed in contact initially with siliceous mud rocks (crystalline shales, sandstones, alluvium) from which the peat isolates itself as it grows ever larger, bulges in the middle, and slopes in all directions toward its periphery.

In order to shed light on the structure of the living soil cover of sphagnets, we used the phytocoenological research method of the Central European School developed by Braun-Blanquet [

10] and tailored to the particularities of Romania’s vegetation by Borza et Boșcaiu [

11], and the classical, practical methods developed by Ivan Doina, Donita N.,[

12], Ivan Doina, Spiridon L. [

13], Ivan Doina [

14]. In the study of the living soil cover, we adopted the vegetal association as the basic coenotaxonomic units in the context of the definition given by Géhu et Rivas-Martinez [

15].

In order to reveal the floristic structure of the phytocoenoses gathered in the Carici echinatae-Sphagnetum association, we carried out 10 phytocenological surveys in sphagnum ecosystems of the Vlădeasa Massif, including a two surveys in Vârfuraș Mountain (at 1,590 m, and 1,602 m altitude), two surveys in Nimăiasa Mountain (at 1,545 m, and 1,579 m altitude), two surveys in Moliviș Mountain (at 1,287 m, and 1,325 m altitude), one survey in Făget Mountain (at 1,170 m altitude), one survey in Bășag Summit (at 1,043 m altitude), and two surveys in Poiana Remețului Depression (at 605 m, and 611 m altitude) during the optimal vegetation period (i.e. in the timeframes 03.07-21.08.2021 and 02.08-16.08.2020).

The floristically and physiognomically homogeneous sample areas sizing between 4-40 m2 were selected from the most representative phytocoenoses of the oligo-mesotrophic, mesotrophic-eutrophic, turbid marshy meadow eco-systems.

The inventoried sample areas were included into the analytical phytosociological table with species ordered by the coenotaxa to which they belong, according to the criterion of constancy, each species providing scientific information on the mean abundance-dominance in the association, belonging to the type of lifeform , phytogeographic element, belonging to the ecological indices (moisture, temperature, chemical reaction of the soil) and to the type of genetic karyotype.

In order to classify the phytocoenosis species of the sphagnum ecosystems in the association with the higher coenotaxa units, alliance, order, vegetation class, we reviewed the classic, traditional ecological & floristic systems of the authors Tüxen [

16], Braun-Blanquet [

10], Soó [

17], Borza et Boșcaiu [

11], as well as the more recently developed ecological & floristic systems [18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25].

Classification of species by bioform categories was carried out according to the system developed by Raunkier [

26], improved by Braun-Blanquet [

10], Ellenberg et al. [

27], and the scientific papers recently published [28, 29, 30].

Classification by categories of phytogeographic elements was made according to the works of Meusel et Jäger [

31], Sanda et al. [

28]. Distribution of species by the categories of ecological indices of moisture (M), temperature (T), and chemical reaction of the soil (R) was done according to Sanda et al. [

28].

Classification of species into genetic categories of ploidy was made according to the works of Sanda et al. [

28] and Ciocârlan [

30].

The research results were processed in tables and represented graphically as spectra reflected as percentages in histograms and diagrams.

3. Results

The phytocoenoses of sphagnum ecosystems built by Sphagnum recurvum P.Beauv., Sphagnum angustifolium C.Jens., Sphagnum magellanicum Brid. and Carex echinata Murray grows in the mountainous and subalpine region of the Vlădeasa Mountains on flat land or mild slopes near springs or streams on a substrate of organic soils, oligotrophic-mesotrophic histosols with a variable content of organic matter (ranging between 35.5-80.5%) with pH values ranging from very acidic to acidic (i.e. pH=4.5-5.5); it is about sites characterized by a humid, cool climate, with an average annual precipitation of 850-1,250 mm and low temperatures oscillating between 0.3-0.9°C.

3.1. Floristic composition or the specific biodiversity

Revealing the floristic composition of the living soil cover in the phytocoenoses of sphagnum ecosystems was one of the first objectives we propose, the information obtained on the list of species being necessary for the preparation of the association table which represents the basic scientific foundation in the interpretation of the research results. The floristic inventory of the phytocoenoses of the ecosystem gathered in the association Carici echinatae-Sphagnetum (Balázs 1942) Soó 1955 encompasses 56 species, of which 50 cormophytes, six bryophytes, which signifies a relatively high biodiversity of a community of phytoindividuals building an exuberant, exclusivist vegetation found only in the sphagnum ecosystems of the Vlădeasa Mountains, characterized by floristic, ecological and physiognomic individuality (see

Table A1 Appendix A).

The species that build and install the physiognomy of the association’s ecosystem are

Carex echinata Murray with a coverage of 50.5% (ADm) maximum constancy (K=V) and

Sphagnum recurvum P.Beauv., with a coverage of 33.05% (ADm), high constancy (K=IV) placed in a codominance relationship (see

Figure 2 below).

Alongside the dominant and characteristic species of the association, in the floristic composition of the phytocoenosis vegetate the characteristic and differential species of the alliance coenotaxa, order, Caricion nigrae et Caricetalia nigraeas follows: Juncus effusus L., Sphagnum magellanicum Brid., Sphagnum angustifolium C.Jens, Sphagnum palustre L., Veronica scutellata L., class Scheuchzerio-Caricetea nigrae: Eriophorum latifolium Hoppe, Carex flava L., Pedicularis limnogena A. Kern., Carex lasiocarpa Ehrh., Swertia punctata Baumg., Juncus alpinoarticulatus Chaix., Menyanthes trifoliata L., Epilobium nutans F.W. Schmidt, Dactylorhiza cordigera Soó, etc….

Transgressive species from the Oxycocco-Sphagnetea class are frequently found in the association: Drosera rotundifolia L., Eriophorum vaginatum L., Sphagnum fuscum (Schimp.) Klinggr., Polytrichum strictum Brid., as sharing the same habitat. At the periphery of the association some species from the spruce forests bordering the coenosis that belong to the Vaccinio-Piceetea class sporadically penetrate: Moneses uniflora (L.) A. Gray, Leucanthemum waldsteinii Pouzar, Homogyne alpina (L.) Cass., and, with a frequency greater frequency, the mesohygrophilous and hygrophilous species immigrated from the mountain and subalpine meadows with which the association comes into contact, such as those from the Molinio-Arrhenathereteaclass: Caltha palustris ssp. laeta L., Myosotis scorpioides L., Galium palustre L., Deschampsia caespitosa (L.) Beauv., Leontodon hispidus L., Anthoxantum odoratum L., Holcus lanatus L., Agrostis gigantea Roth., etc., from the Nardo-Callunetea class: Potentilla erecta (L.) Raeusch, Crepis paludosa (L.) Moench, Danthonia decumbens (L.) DC., Filipendula ulmaria (L.) Maxim., Nardus stricta L., Hieracium aurantiacum L., etc….

3.2. Ecological characterization of the flora and vegetation of sphagnum ecosystems

It is another important objective subjected to research, in which accumulation of scientific information provided helped us to understand the complex interrelationships between plant species that coexist within the ecosystem and their entire coenosis in relationship with environmental factors acting both from within and outside on the habitat of the peat bogs.

3.2.1. Composition by categories of bioforms

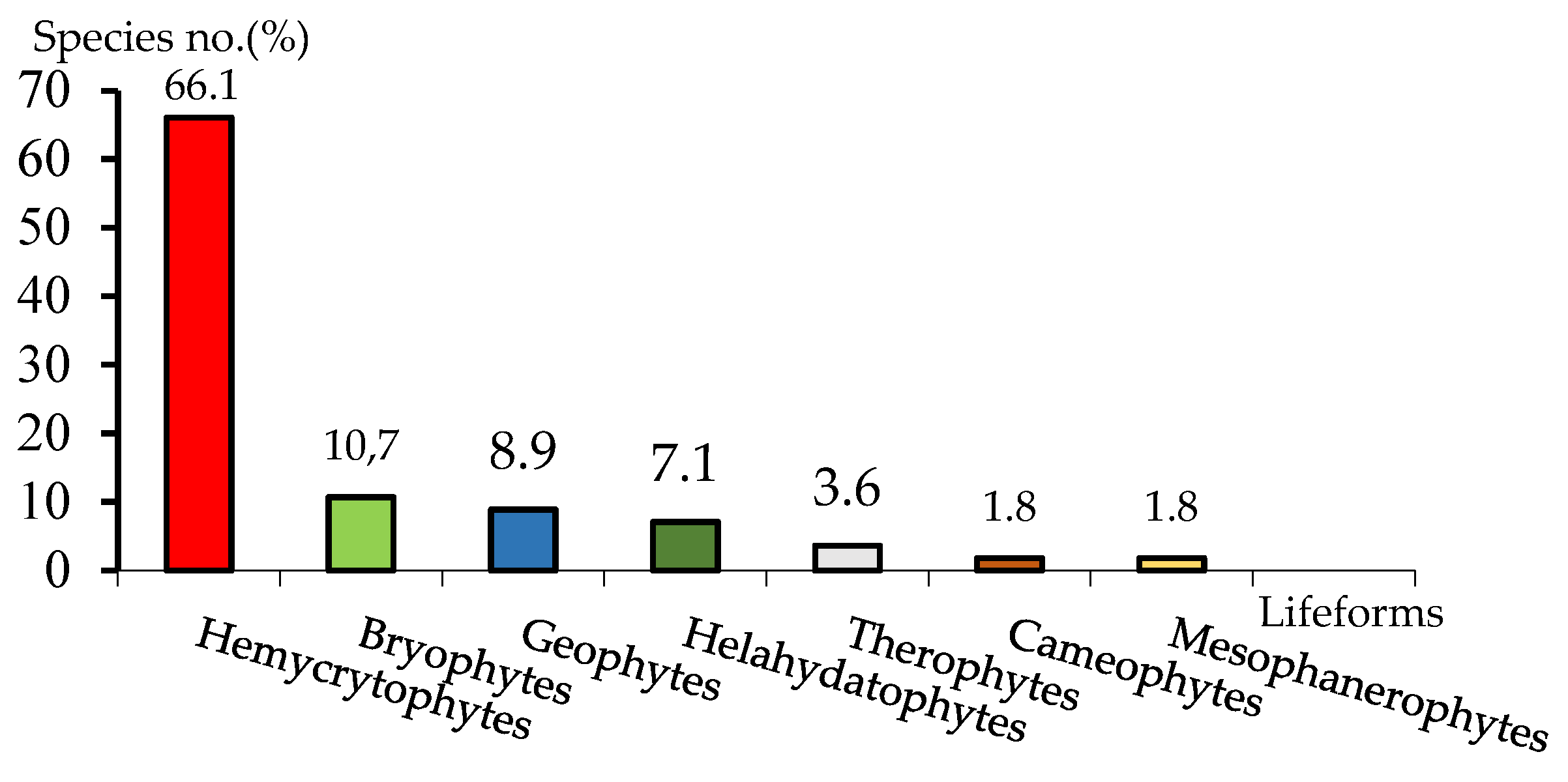

Being familiar with the composition of the phytocenosis by categories of bioforms is important as the type of bioform shows us how the living organism of the plant or the species adapts to the living environment (terrestrial, aquatic) in order to protect its regenerative buds (through which the life perpetuation is ensured) during vegetative rest, frosty winters or excessively dry summers such as those in arid places. The spectrum of bioforms (se

Figure 3 below) shows the dominance in the phytocenosis of hemicryptophytes (66.1%) adapted to a temperate-moderate climate, whose supremacy is imposed as we climb the altitude steps of the Vlădeasa Mountains relief, followed by a landslide by bryophytes (10.7%), geophytes (8.9%), helahydatophytes (7.1%), therophytes (3.6%), and cameophytes (1.8%).

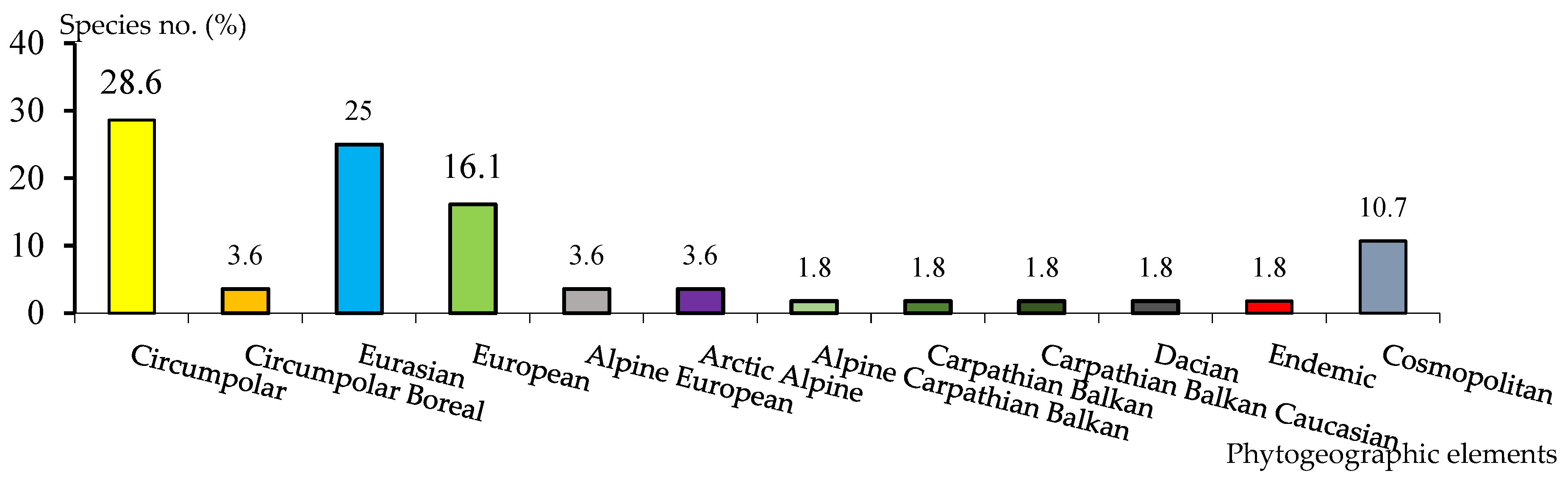

3.2.2. Composition by categories of phytogeographic elements (geoelements)

The knowledge of the proportions of geoelements that make up the flora of the populations of the sphagnum ecosystems in the Vlădeasa Massif, provides us with information on the origin and florigenetic diversity, of the areal-geographical interferences triggered by the migration of plant species in phytohistorical times. The geographical area and the current distribution of the species within the territory (see

Figure 4 below) highlight a very diversified phytogeographic picture made up of a procession of species in which circumpolar, and circumpolar-boreal elements are dominant (i.e. 32.2%) followed by genetic and geographical elements of origin in the Arctic Circle, then followed by Eurasian (25%), European (16.1%), and cosmopolitan (10.7%) species. To a smaller extent, the stenochoric, Alpine-European, Arctic-Alpine (7.2%), Alpine-Carpatho-Balkan, Carpatho-Balkan, Carpatho-Balkan-Caucasian (5.4%), Endemic (1.8%), Dacian (1.8%) species are present. The presence of Alpine-Carpatho-Balkan, Carpatho-Balkan, Carpatho-Balkan-Caucasian species in the territory confirms the connections and phytohistorical interferences of the flora and vegetation of the sphagnum ecosystems of the Vlădeasa Massif, the Western Carpathians with that of the Balkan Mountains, especially with the lands to the south of the Danube. Moreover, the presence of alpine-European, arctic-alpine species in the phytocenosis are proof of the floristic-phytohistorical connections between the Romanian Carpathians and the Europe’s Alps.

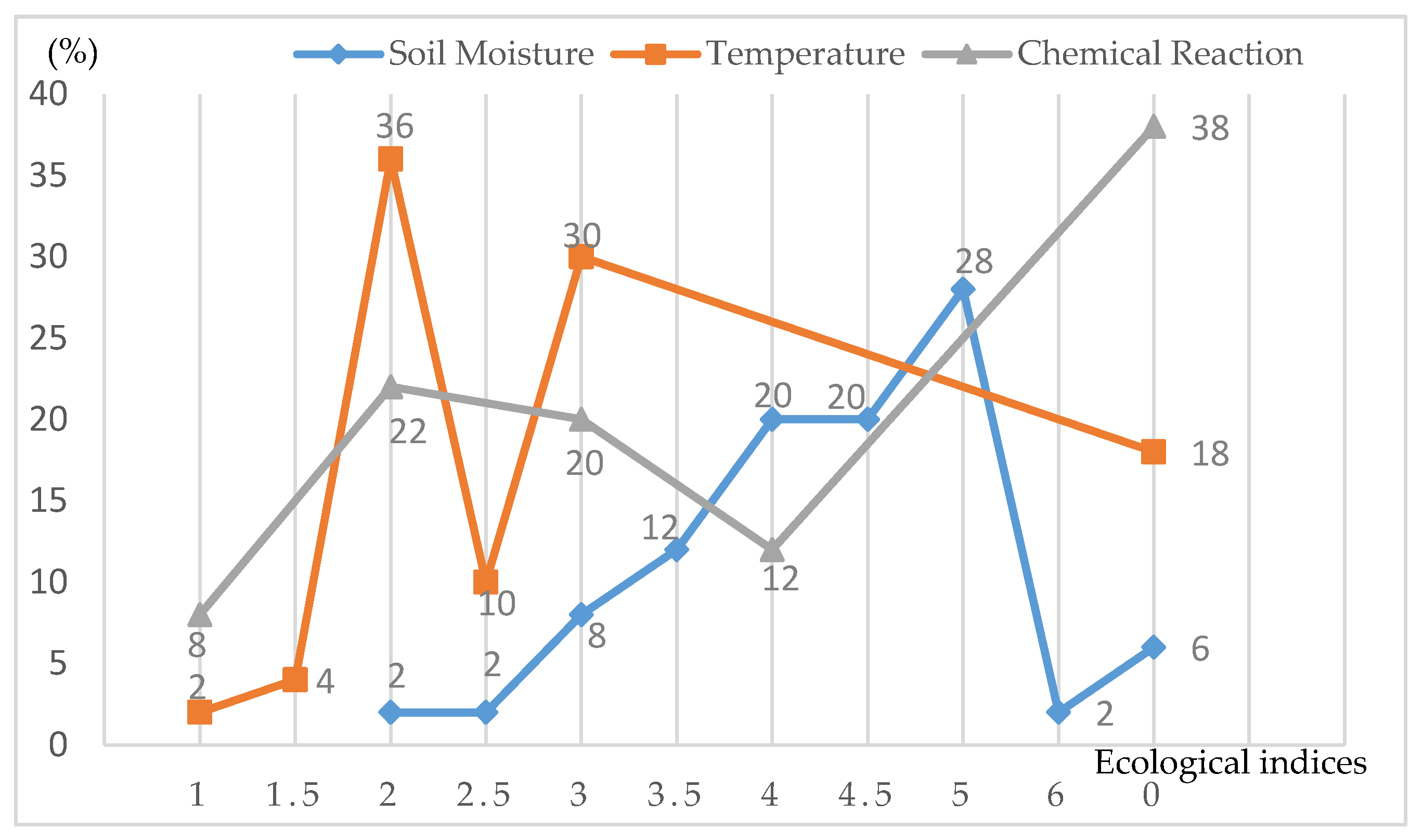

3.2.3. Composition by ecological categories with moisture, temperature and chemical reaction of the soil

The analysis of the composition of peat bogs phytocoenoses by the ecological categories of edaphic moisture (M), air temperature (T), chemical reaction of the soil (R) is important because the ecological valences (preferences) of the species in relation to the main ecological factors, which highlight the ecological specificity of the habitat, are taken into account for the sites where the plants grow (see

Table 1 below).

The ecological indices (factors) diagram (see

Figure 5 below) suggests that depending on the soil moisture, the majority in the phytocenosis is represented by the mesohygrophilic species (i.e. (U

4-4,5=40%) followed by the hygrophilic ones (i.e. U

5-5,5=28%) and eurihydric species (i.e. U

0=6%). In terms of temperature, in the phytocenosis, the dominant species are microthermal species (T

2-2,5=46%) followed by micromesothermal (T

3-3,5=30%), eurythermal (T

0=18%) and cryophilic ones (T

1-1,5=6%). With regard to the chemical reaction of the soil in the phytocenosis, the euriionic species are dominant (R

0=38%) accompanied by acidophilic (R

2=22%), acid-neutrophilic (R

3=20%) and strong acidophilic species (R

1=8%).

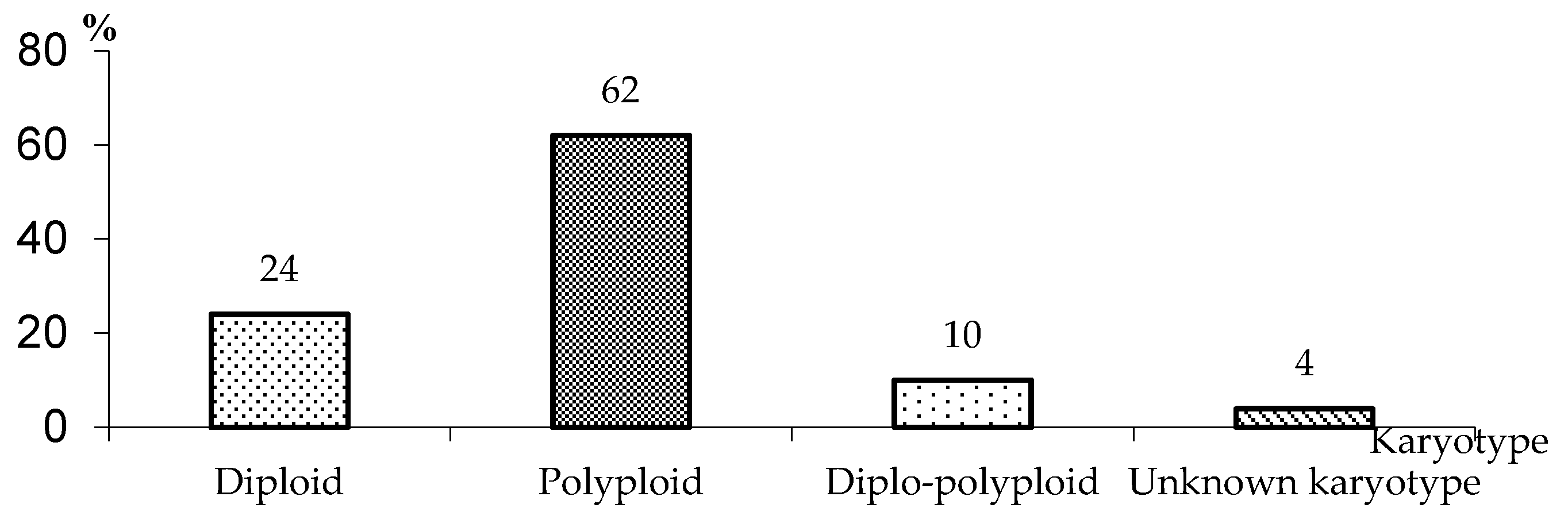

3.2.4. Composition by karyotype genetic types

Knowledge of the composition of the ecosystem (habitat) of the phytocenosis by genetic types or the genetic structure of plant populations is necessary if the number of chromosome pairs-the basic genetic karyotype is studied when the presence of a relationship between the karyological constitution of plant species and distribution thereof is established within the territory in the sense of increasing the share of polyploids. Thus, when the number of basic chromosome pairs (x) multiplies, a wide range of plant cells and organisms occurs: diploid (2x), triploid (3x), tetraploid (4x), pentaploid (5x), hexaploid (6x) that form a polyploid series, this phenomenon being called polyploidy. Polyploidy provides the phytoindividuals of the ecosystem with increased resistance in extreme (unfavourable) living conditions and a high interspecific competition capacity in the colonization of a bare land, compared to diploid individuals that do not manifest expansion tendency. The karyological spectrum (see

Figure 6 below) of the flora of the phytocoenoses gathered in the

Carici echinatae-Sphagnetum association is dominated by polyploid species (62%) followed by a landslide by diploid (24%) and diplo-polyploid (10%) species.

3.3. Vegetation dynamics of ecosystems

The stable climactic balance of the peatland ecosystem of the Vlădeasa Massif can be maintained for hundreds, even thousands of years if endo-ecogenetic, exo-ecogenetic and anthropogenic factors do not act on it; if these factors manifest in this ecosystem they can trigger deep and rapid changes in the structure and physiognomy of the living soil cover. Deforestation, grazing, mowing, application of mineral fertilizers are only a few examples of anthropo-zoogenic factors that can unbalance the phytocenoses of the association and implicitly the entire ecosystem. Simultaneously with the elimination of permanent sources of water (springs, streams flowing from the slopes), a depletion occur in terms of excess moisture in the raised bogs, a lower pH of the soil and water to the weakly acidic or slightly neutral range, when the decline of the ecosystem begins and resulting in the succession of vegetation in a first stage towards the phytocoenoses of the Carici-Nardetum strictae association (Resmeriță 1984) Resmeriță et Pop 1986 (Syn: Hygronardetum montanum Resmeriță et Csürös 1963, Buia 1963; Hygronardetum subalpinum Resmeriță et Csürös (1960) 1963, Hygronardetum strictae alpinum Buia et al. 1962). Subsequently, the phytocoenoses of the hygro-nardetes ecosystem can be replaced respectively they can evolve towards the phytocoenoses from Molinio-Arrhenatheretea class buil by the species Caltha palustris ssp. laeta L., with a coverage of 0.8 ADm, present in 7 surveys out of a total of 10, Myosotis scorpioides L., with a coverage of 0.25 ADm, present in 5 surveys, Galium palustre L., ADm 0,2, present in 4 surveys, Deschampsia caespitosa (L.) Beauv., ADm 0.15, present in 3 surveys, Gymnadenia conopsea (L.) R. Br., ADm 0.1, present in 2 surveys and Ranunculus repens L., ADm 0.05, present in only one surveys.

3.4. Economic and scientific relevance

The raised bogs (peat bogs or peatlands) are unproductive lands whose vegetation is grazed by animals only in years with summers characterized by an excessive drought, while grass mowing is done on small areas, it is incomplete, and the fodder thus obtained is of lower quality. There are few cases where peat bogs have been converted into hayfields.

Peat in large reserves can be used in a country’s energy industry, peat coke being an excellent energy material. In the chemical industry, peat tar is obtained from dry peat, as well as important chemical compounds such as phenols, cresols, paraffin, etc... In the construction industry, heat insulators, plates and bricks for civil engineering works can be obtained from processed peat. In the pharmaceutical industry, substitutes for cotton wool and medicinal charcoal have been produced from peat. Peats can also be used in medicine, in modern balneology with special therapeutic effects due to their physical properties and the nature of the chemical components, e.g. the medicinal peats from the basins of the following rivers: Bilbor, Dorna, Neagra Broștenilor, Mureș and Olt (upper basin). In agriculture, peat can be used as a nitrogen-based fertilizer by saturating it with ammonia, for fertilizing sandy agricultural lands, those poor in organic substances or excessively calcareous. Peat together with animal dung is used as a cellulosic nutrient substrate (compost) in the culture of the following mushrooms Agaricus (Psaliota) bisporus, Pleurotus ostreatus, Pleurotus florida, Pleurotus sajor-caju, etc. In the domestic industry, peat is used to insulate the walls of houses and ice cold storages. In order to prevent environmental pollution with industrial residues, peat is used in the ecological reconstruction of mineral dumps, ash deposits in the surroundings of thermal power plants by covering and isolating pollutants with a layer of peat soil and fallow meadow covers. Peat soil is also used as substrate material and fertilizer in the culture of flower for pots. From a scientific perspective, peat bogs, especially the ecosystems of the peat bogs, form a multi-millenary documentary archive by the fact that in the successive horizons of their sediment, the pollen grains of some glacial relict plant species and more, and which lived in distant phyto-history periods are preserved, based on the study of which the succession and evolution of vegetation on Earth can be reconstructed.

3.5. Current state of play, potential threats, ecosystem management and the issue of biodiversity protection of representative raised bogs in the Western Carpathians

The association’s phytocenoses are included in the Romanian habitat R5410: Southeast Carpathian mesotrophic bogs with

Carex echinata Murray and

Sphagnum recurvum P.Beauv, and in the European ones EMERALD: 54.4 Acid fens; EUNIS: D2.22

Carex nigra (L.) Reichard,

Carex canescens L.,

Carex echinata fens, DIRECTIVA HABITATE (92/43/EEC), Habitats Manual from Romania, Changes brought according to the amendments proposed by Romania and Bulgaria to the Habitats Directive [

32]. The raised bogs included in this habitat (ecosystem) host relict species:

Drosera rotundifolia L. (VU, [

33]),

Eriophorum vaginatum L., endemites:

Pedicularis limnogena A. Kern. (LR, [

34]), vulnerable:

Dactylorhiza maculata (L.) Soó (LC, [

35]),

Dactylorhiza cordigera (Fr.) Soó (LC, [

35]),

Gymnadenia conopsea (L.) R. Br. (LC, [

35]),

Menyanthes trifoliata L. (LC, [

35]),

Swertia punctata Baumg.,

Epilobium nutans F.W. Schmidt,

Glyceria plicata Chevall,

Leucanthemum waldsteinii Pouzar which are included in the "Red List" [

36].

Currently, there are approximately 436 active marshes in Romania, occupying a total area of 7,000 ha, of which 14 marshes are protected or proposed for protection [

1], the protected marshes representing a percentage of 11.8%, which is insufficient should we refer to the large number of swamps and the total swampy areas occupied by them. In the Apuseni Mountains there are a number of about 100 active marshes (peat lands) that occupy a total area of about 186 ha, of which three marshes (oligotrophic swamps) are protected, being declared protected areas or proposed for obtaining the natural monuments status.

3.5.1. Călățele oligotrophic swamp

It is located in the northwest of the Gilău Mountains, 5 km away from Călățele commune, Cluj county, at the altitude of 916 m. It has an area of 12 ha, the peat layer reaches a thickness of 5.6 m and a volume of 300,000 m3. In 1951, the intensive exploitation of the peat for fuel began, on which occasion a large channel was drawn through the axis of the peat land, through the ponds and the central hollow. The artificial drainage started in 1951 caused the water level in the peat land to drop, the ponds and the central portion dried up and a number of 10 rare, relict species disappeared definitively and irretrievably, among which we mention: Scheuchzeria palustris L., Rhyncospora alba (L.) Vahl., Carex buxbaumii Wahlenb., Eleocharis carniolica W.D.J. Koch, Sphagnum balticum (from the only site in România), Andromeda polifolia L., Empetrum nigrum L., Betula pubescens Ehrh., etc.. From the information gathered from the locals in the area, it appears that the ecological reconstruction of the ecosystem has not been done due to the lack of water source, and the recovery of biodiversity and the conservation of rare, endangered, relict species is no longer possible after the ecological catastrophe occurred 72 years ago, when environmental protection and nature protection in Romania were affected by a legal vacuum.

In the eruptive block of the Gilău Mountains there are also cases of partially exploited peatlands such as peatland from Dorna in an area of 1.5 ha, located on the Răcătău Valley, at the altitude of 1,220 m, left tributary of the Someșul Rece river where a temporary interruption took place of the hydrological regime since 1956. After the completion of the exploitation works of the peat deposit, the water supply from the Răcătău river bed was restored, by the application of a management plan with well-chosen objectives, and thus it was possible to activate the peat layer of roughly 4 m thick and the re-establishment of the vegetation of the ecosystem consisting of the following species: Eriophorum vaginatum L., Sphagnum recurvum P.Beauv., Sphagnum magellanicum Brid., Sphagnum russowii Warnst., Epilobium palustre L., Carex pauciflora Lightf., Carex echinata Murray, Drosera rotundifolia L., Andromeda polifolia L., Empetrum nigrum L., etc. This is one of the few examples with reference to the wet-marsh areas of the Apuseni Mountains where the recovery of biodiversity, conservation and sustainable restoration of an ecosystem belonging to the natural habitat of community interest NATURA2000:7120 Degraded raised bogs still capable of natural regeneration has been achieved, Habitats Directive-92 /43/CEE of May 21, 1992 [32, 37].

3.5.2. Molhașul cel Mare oligotrophic swamp from Izbuc - Padiș block mountains, Someșul Cald spring.

It is the largest, most beautiful and representative peat land in the Apuseni Mountains encompassing eight so-called “bottomless" lakes that keep it active all the time, with a living soil cover that regenerates exuberantly in its bulged region. It is located near Someșul Cald river spring at an altitude of 1,160 m. It occupies an area of 8 ha, the average thickness of the peat layer reaching 4 m, and the peat deposit volume is estimated at 320,000 m3, being the most voluminous in the Apuseni Mountains. On the banks of lakes and ditches filled with water, plant communities grow but they require in situ conservation measures of the biodiversity made up of rare, relict species such as: Rhynchospora alba (L.) Vahl, Scheuchzeria palustris L., Carex limosa L., Carex echinata Murray, Lycopodium innundatum L., Pedicularis limnogena A. Kern., Menyanthes trifoliata L., Sphagnum cuspidatum Ehrh., Epilobium palustre L.. On the plateau and on the convex part of the raised bog, species belonging to the genus Sphagnum L. grow abundantly as compact cushions covered by Empetrum nigrum L., Andromeda polifolia L., Vaccinium oxycoccus L., Vaccinium microcarpum (Rupr.) Schmalh, Drosera rotundifolia L., Eriophorum vaginatum L., Eriophorum angustifolium Honck., Eriophorum scheuchzeri Hoppe, Carex pauciflora Lightf. The peat bog is included in the habitat (ecosystem) NATURA2000:7150 Depressions on peat substrates of the Rhynchosporion EMERALD:54.6 of exceptional scientific importance. The ecosystem is protected and monitored within the Apuseni Mountains Natural Park. In the Balomireasa-Căpățâna-Creasta Dobrinului, Gilău Mountains block mountains, at the headwaters of Someșul Rece river, there is a marshy complex made up of numerous bogs, some populated with Pinus mugo Turra (Pino mugo-Shagnetum Kästner et Flösner included in the forestry real estate), others in the form of marshy (Eriophoro vaginati-Sphagnetum recurvi Hueck 1925, Caricetum limosae Br.-Bl.) of which the most representative are the following ecosystems: Căpățănii oligotrophic swamps (Mocirle, Tăul Sărat/ Salty tarn) and Vârful Băii peak (Căpățănii tarn) protected by the protected areas act.

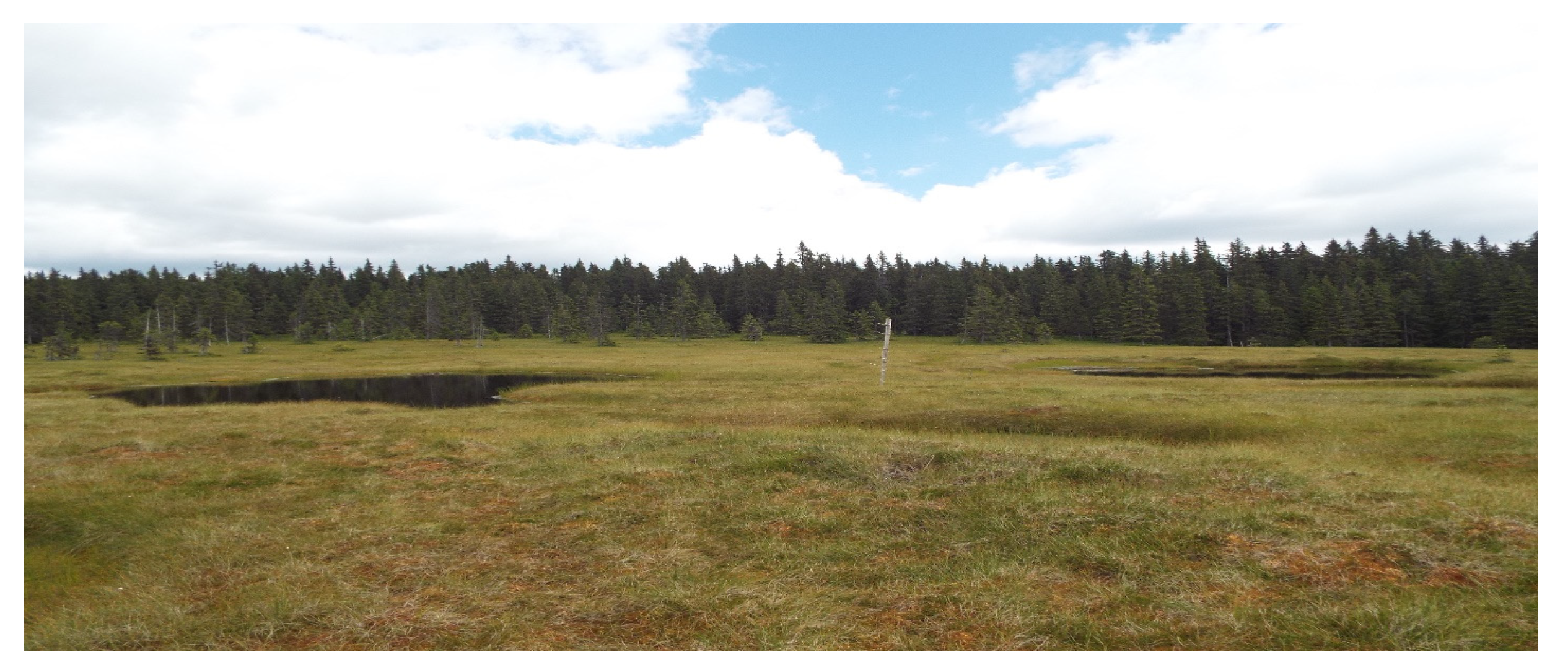

They make up a complex of marshy ecosystems consisting of two large peat bogs separated from each other by a strip of spruce, located at an altitude of 1,590-1,603 m (see

Figure 7 below). The first peat bog covers a surface of 5 ha and it is colonized by a population (10-15 samples) of

Pinus mugo Turra (juniper) concentrated on an area of about 50 m

2. The second covers an area of 8 ha, with a thickness of the peat layer of 4.5 m, the total volume of peat reaching 250,000 m

3 is devoid of mountain junipers, but having instead in the middle a so-called "bottomless" lake with brown water - blackish, sour (salty tarn) and several ponds along its length populated at the edges by

Scheuchzeria palustris L.,

Carex limosa L.,

Carex pauciflora Lightf.,

Drosera intermedia Hayne,

Sphagnum cuspidatum Ehrh. Etc. These two marshes are considered by specialists to be the most primitive, wild and authentic ecosystems (habitats) in the Western Carpathians, being proposed to be declared and preserved

in situ as Natural Monuments.

This large and representative marshy ecosystem is place at an altitude of 1,630 m, close to Căpățănii peak, being surrounded by a marshy spruce grove. It covers an area of 3.5 ha, the peat layer ranges between 4-5 m thick, the total peat volume is estimated at 120,000 m

3. In the middle of the forest there are two deep lakes and numerous ditches and ponds, on the periphery of which there are growing rare species, glacial relicts, ,

Scheuchzeria palustris L.,

Lycopodium innundatum L.,

Carex limosa L.,

Carex magellanica Hiitonen,

Drosera rotundifolia L.,

Pedicularis limnogena A.Kern,

Eriophorum scheuzeri Hoppe,

Eriophorum vaginatum L.,

Vaccinium microcarpum (Rupr.) Schmalh, etc…, on a compact moss carpet consisting of

Sphagnum cuspidatum Ehrh.,

Spagnum magellanicum Brid. (see

Figure 8 below).

In situ conservation, and the very existence and functioning of wetland ecosystems is closely related to the constant maintenance of the parameters of ecological factors: water from the water table (springs, streams) and nutrients from precipitation (atmospheric humidity), chemistry (pH) of water and soil, and a cool habitat environment with low temperatures. When the listed basic requirements are not met, there may occur an imbalance of the sphagnum ecosystems or even their destruction. The threats regarding the destabilization of the balance of phytocenoses and wetland ecosystems are numerous, of different origins and with negative impact on the environment and nature.

Among the most well-known and which occur with a higher frequency, we mention:

- -

Exploitation of peat from high peats, although strictly regulated, is done only in isolated cases and after prior obtaining legal approvals, e.g. the degraded high peats from Călățele and Dorna (Someșul Rece river valley), Cluj county;

- -

Logging, forest clearings around the wetland ecosystems can trigger imbalances and dysfunctions in the hydrological and microclimate regime in the raised bogs habitat;

- -

Drainage of peat lands and the collection of the waters that feed them generate serious dysfunctions in the balance and self-regulation of the ecosystem, one of the basic requirements being the permanent presence of excess water;

- -

Grazing and the transit of animals through wetlands produces soil subsidence and destruction of the peat moss layer (Sphagnum L. sp.) and triggers the modification of the floristic composition of the grassy layer, which ultimately leads to the disappearance of glacial relict, rare, endemic species, the loss of biodiversity and the degradation of the entire ecosystem;

- -

Construction of roads with consolidated infrastructure leads to anthropization, destruction and pollution of the forest ecosystem, and to dysfunctions in the hydrological regime of the habitat.

- -

Within the surveyed territory, 23 taxa were found (see

Table 2 below) representing rare plants, glacial relicts, endemites in different stages of endangerment: vulnerable – VU (

Pedicularis limnogena A. Kern,

Rhynchospora alba (L.) Vahl.,

Scheuchzeria palustris L.), critically endangered – CR (

Drosera intermedia Hayne), in critical risk - CR (Drosera intermedia Hayne), in low risk - LR (Pedicularis limnogena A. Kern), of least concern - LC (

Carex limosa L.,

Lycopodium inundatum L.,

Eriophorum scheuchzeri Hoppe,

Dactylorhiza cordigera (Fr.) Soó,

Dactylorhiza maculata (L.) Soó,

Gymnadenia conopsea (L.) R.Br.

Dryopteris dilatata (Hoffm.) A.Gray), and near threatened – NT ((

Carex magellanica ssp.

irrigua Hiitonen,

Drosera rotundifolia L.,

Empetrum nigrum L.,

Dryopteris cristata (L.) A.Gray,

Menyanthes trifoliata L.,

Swertia punctata Baumg.,

Vaccinium microcarpum (Rupr.) Schmalh,

Vaccinium oxycoccos L.) included on the red lists at national and European level [33, 34, 35, 38, 39, 40].

At international level, according to the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) criteria, the conservation status of many cormophytes is not yet sufficiently known, Data Deficient (DD) [35, 38, 40]; this state of play requires a permanent monitoring of these plants populations by the custodians of the site together with the specialists from the Scientific Council in charge with the site in question.

4. Discussion

With regard to the floristic composition of the phytocoenoses of

Carici echinatae-Sphagnetum association, the results obtained on the biodiversity vary within reasonable limits, from 56 cormophytes and bryophytes in the Sphagnetum ecosystems we surveyed in the Vlădeasa Mountains, to 27 species listed in the floristic list by Pop et al. [

2] in the Gilău Mountains on the Someșului Rece Valley, and 49 species found by Togor [

8] in the Bihor Mountains-Padiș Mountain Massif. It turns out that the raised bogs investigated by us in the Vlădeasa Massif have the highest biodiversity followed by those studied by Togor [

8] in Padiș Mountain Massif as an expression of the seasonal conditions specific to the place depending relief, altitude and soli acidity.

The analysis of the ecological valences of the species in relation to the influence of environmental factors (soil moisture, air temperature, chemical reaction of the soil) shows us a similarity of the values quantified in the comparison of the results for the three geographical regions with some small exceptions. Thus, in relation to moisture, the phytocoenoses associated with the eco-system have a mesohygrophilic U

4-4,5=40%) to hygrophilic (U

5-5,5=28%) nature in the Vlădeasa Mountains i.e. the territory surveyed by us, very close to a mesohygrophilic (U

4-4,5=36,59%) to hygrophilic (U

5-5,5=31,71%) character in the Bihor Mountains, Padiș Plateau [

8] and a higher percentage hygrophilic (U

5-5,5=51,8%) to meso-hygrophilic (U

4-4,5=29,61%) specificity in the Gilău Mountains, Someșul Rece river valley [

2] where the degree of water absorption of the soil in the stream bed of the Someșul Rece river valley is much more pronounced as a result of the proportion of peatlands in the stream bed of this river, see

Table 3 below.

In terms of temperature, the similarity of the quantified values is even more accentuated (pronounced), the phytocoenoses of the peatlands association in the three geographical regions entailing a microthermal (T

2-2,5=46%) to micromesothermal (T

3-3,5=30%) character in the Mountains Vlădeasa territory surveyed by us, a microthermal (T

2-2,5=56,09%) to micromesothermal (T

3-3,5=24%) nature in the Bihor Mountains, Padiș Plateau [

8], and micromesothermal (T

3-3,5= T

2-2,5=59,2%) to eurythermal ((T

0=22,2%) nature in the Gilău Mountains, and Someșul Rece river valley [

2] – see

Table 3. The small differences in the percentages of the results are explained by similar pedoclimatic conditions of the resorts where the phytocoenoses of the association develop.

In relation to the chemical reaction of the soil, the phytocoenoses of the peatlands present an ionic amphitolerant (R

0=38%) to acidophilic (R

2=12%) character in the territory surveyed by us, an acidophilic (R

2=34,15%) to ionic amphitolerant (R

0=24,39%) nature in the Bihor Mountains, Padiș Plateau [

8] and an acidophilic (R

2=33,3%) to strongly acidophilic (R

1=25,9%) specificity in the Gilău Mountains, Someșul Rece river valley [

2] – see

Table 3. The different results in percentages regarding the chemical reaction of the soil in view of the phytocoenoses in the habitas of 3 geographical regions are due to different nature of the substrate of calcareous rocks in the Padiș Plateau, acidophilic in Vlădeasa Mountains and strongly acidophilic in the Gilău Mountains. As an expression of the adaptation of the species from 3 resorts to a temperate continental climate.

The analysis of the bioforms from the phytocoenoses of the surveyed peatlands highlights quantitative results close to those obtained by us, illustrated by the dominance of hemi-cryptophyte species in all three geographical regions, in a percentage of 66.1% in the Vlădeasa Massif surveyed by us, 70.73% in the Padiș Bihor Mountains block mountains [

8], 55.5% in the Gilău Mountains, Someșul Rece river valley [

2], succeeded by bryophytes of the genus

Sphagnum L. (10.7%) in the Vlădeasa Mountains, geophytes (19,.51%) in the Bihor Mountains-Padiș Plateau, cameophytes (37%) in the Gilău Mountains, Someșul Rece river valley (see

Table 4 below).

Territorial distribution of the geoelements of the

Carici echinatae-Sphagnetum association according to the origin within the geographical area shows very similar results to those obtained by us, supported by the predominance of circumpolar, circumpolar-boreal species in all three geographical regions in percentages of 32.2% in the Vlădeasa Mountains i.e. a territory surveyed by us, 46.2% in the Bihor Mountains, Padiș Plateau [

8], 63.5% in the Gilău Mountains, Someșul Rece river valley [

2] followed by Eurasian species 25.1% in the Vlădeasa Mountains, 25.3% in the Bihor Mountains, Padiș Massif, and 18% in the Gilău Mountains, Someșul Rece river valley (see

Table 5 below).

In conclusion, instead, the presence of some differences regarding the compared data of the analysed results may be explained by the different environmental conditions (local pedoclimatic factors) that characterize the habitats of the raised bogs (i.e. altitude, water and soil chemistry) from the three geographical regions and which are obviously different both from each other and in terms of geomorphological structure and landforms.

5. Conclusions

Following the phytocenological, ecological, eco-protective and economic study of peatland phytocenoses from the Vlădeasa Massif, Western Carpathians, we have drawn the following conclusions:

Vegetation of the ecosystems of the surveyed peatland has a predominantly mesohygrophilic (40%) to hygrophilic (28%), microthermic (46%) to micromesothermic (24%), ionic amphitolerant (38%) to acidophilic (22%) character;

Composition of phytocoenoses by ecological categories of bioforms is dominated by hemicryptophyte (66.1%) and bryophytes (10.7%) species, as main components of the herbaceous layer of peatland ecosystems;

Composition of phytocoenoses by categories of phytogeographic elements (geo-elements) is dominated by circumpolar, circumpolar-boreal (32.2%), alpine-European, arctic-alpine (7.2%) plants which have overlapped in the long process of evolution and speciation with Eurasian (25%), European (16%), and Cosmopolitan (10.7%) plants. The share of Carpatho-Balkan, Alpine-Carpatho-Balkan, Carpatho-Balkan-Caucasian species in a percentage of 5.4% suggests the existence of floristic-phytohistorical links between the vegetation of the Western Carpathians and that of the Balkan Mountains, the European Alps and the Caucasus Mountains;

Composition of peatland vegetation by karyotype genetic types is favourable to the development of polyploid species (62%) whose basic genotype, multiplied several times, provides their resilience to extreme living conditions (very high acidity of water and soil, low temperatures) of the habitat, a high interspecific competition capacity in the colonization of the land.

With regard to the current state of the ecosystem, biodiversity conservation, potential threats and peatlands management, we pointed out some of the most frequent and harmful human interventions (e.g. exploitation of peat deposits, road construction, drainage of sediments and collection of water, grazing and the transit of animals through the habitat) that lead to the destabilization of the ecological balance and the degradation of the ecosystem.

Peat deposit has a special economic value, being available for use in almost all fields: energy, construction, domestic, chemical, and pharmaceutical industries, medicine, agriculture, but it also has a paleontological & scientific value in the archiving of pollen grains and fossil relicts of ancient plants and animals.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.I.N.B. and I.F.P.; Data curation, L.I.N.B.; Formal analysis, I.F.P. and E.A.M.; Investigation, L.I.N.B., I.F.P. and I.C.M.; Methodology, I.F.P., I.C.M., and I.A.V.; Software, I.F.P., and I.A.V.; Validation, L.I.N.B., I.F.P., E.A.M., I.C.M., and I.A.V.; Resources, L.I.N.B., I.F.P. and I.C.M.; Writing-original draft, L.I.N.B., I.C.M., and E.A.M.; Writing-review and editing, I.F.P., Visualization, I.F.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study may be obtained on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The research undertaken was made possible by the equal scientific involvement of all authors concerned.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Plant association Carici echinatae-Sphagnetum (Balázs 1942) Soó 1955.

Table A1.

Plant association Carici echinatae-Sphagnetum (Balázs 1942) Soó 1955.

| Bio. |

P.e. |

M |

T |

R |

2n |

Survey no. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

K |

ADm |

| - |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Altitude (mamsl ) |

1602 |

1590 |

1579 |

1545 |

1325 |

1287 |

1170 |

1043 |

611 |

605 |

|

|

| - |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Grassy layer coverage (%) |

60 |

90 |

80 |

70 |

70 |

90 |

80 |

100 |

100 |

90 |

|

|

| - |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Exposure |

S |

- |

- |

E |

- |

- |

N |

SV |

- |

- |

|

|

| - |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Slope(°) |

0-2 |

- |

- |

2-4 |

- |

- |

0-2 |

2-4 |

- |

- |

|

|

| - |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Surface (m2) |

16 |

4 |

8 |

12 |

2 |

10 |

4 |

8 |

20 |

40 |

|

|

| H |

Cp |

5 |

2 |

1 |

P |

As. Carex echinata |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

2 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

4 |

4 |

V |

50.5 |

| Brchs |

Cp-Bo |

- |

- |

- |

- |

As. Sphagnum recurvum

|

3 |

3 |

4 |

1 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

+ |

. |

. |

IV |

33.05 |

| Caricion nigrae et Caricetalia nigrae |

| H |

Cosm |

4.5 |

3 |

3 |

P |

Juncus effusus |

+ |

. |

. |

+ |

. |

+ |

+ |

2 |

. |

+ |

III |

2 |

| H |

Cp |

5 |

0 |

2 |

P |

Epilobium palustre |

. |

+ |

+ |

. |

. |

+ |

+ |

+ |

. |

. |

III |

0.25 |

| Brchs |

Cosm |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Sphagnum magellanicum |

. |

. |

. |

. |

+ |

. |

1 |

5 |

+ |

. |

II |

9.35 |

| Brchs |

Cp |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Sphagnum angustifolium |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

5 |

5 |

I |

17.5 |

| Brchs |

Cosm |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Sphagnum palustre |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

+ |

. |

. |

I |

0.05 |

| H(Hh) |

Cp |

4 |

3 |

4 |

D |

Veronica scutellata |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

+ |

. |

. |

. |

I |

0.05 |

| Scheuchzerio-Caricetea nigrae |

| H |

Eua |

5 |

0 |

4.5 |

P |

Eriophorum latifolium |

+ |

+ |

. |

+ |

1 |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

. |

IV |

0.85 |

| H |

Cp |

4.5 |

3 |

0 |

P |

Carex flava |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

. |

. |

+ |

+ |

1 |

+ |

IV |

0.85 |

| H |

Carp-B |

5 |

2 |

2 |

N |

Pedicularis limnogena |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

II |

0.2 |

| Hh(H) |

Cp |

5 |

2.5 |

2.5 |

P |

Carex lasiocarpa |

. |

. |

. |

. |

+ |

. |

+ |

. |

. |

. |

I |

0.1 |

| H |

Carp-B-Cauc |

5 |

1.5 |

0 |

P |

Swertia punctata |

+ |

+ |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

I |

0.1 |

| H |

Arct-Alp |

4 |

2 |

2 |

P |

Juncus alpinoarticulatus |

. |

. |

. |

+ |

. |

. |

+ |

. |

. |

. |

I |

0.1 |

| G |

D |

4,5 |

2 |

2 |

P |

Dactylorhiza cordigera |

. |

. |

+ |

+ |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

I |

0.1 |

| Hh |

Cp |

5 |

3 |

3 |

P |

Menyanthes trifoliata |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

+ |

+ |

I |

0.1 |

| H |

Alp-E |

5 |

2 |

2 |

N |

Epilobium nutans |

. |

. |

. |

+ |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

I |

0.05 |

| G |

E |

4 |

2 |

2 |

P |

Dactylorhiza maculata ssp. maculata |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

+ |

. |

. |

. |

. |

I |

0.05 |

| H |

Eua |

4.5 |

3 |

3 |

P |

Ranunculus flammula |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

+ |

. |

. |

I |

0.05 |

| Hh(H) |

Cp |

5 |

2 |

0 |

P |

Carex rostrata |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

+ |

I |

0.05 |

| H |

E |

4,5 |

2 |

4.5 |

P |

Carex lepidocarpa |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

+ |

I |

0.05 |

| Oxycocco-Sphagnetea |

| H |

Cp |

5 |

2.5 |

1 |

D |

Drosera rotundifolia |

. |

. |

+ |

+ |

. |

. |

. |

+ |

+ |

+ |

III |

0.25 |

| H |

Cp |

4.5 |

0 |

1.5 |

D |

Eriophorum vaginatum |

1 |

. |

+ |

. |

. |

+ |

. |

+ |

. |

. |

II |

0.65 |

| Brchs |

Cp |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Sphagnum fuscum |

1 |

1 |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

I |

1 |

| Brchs |

Cp-Bo |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Polytrichum strictum |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

+ |

. |

. |

. |

. |

I |

0.05 |

| Vaccinio-Piceetea |

| G(H) |

Cp |

3 |

2 |

2.5 |

D |

Moneses uniflora |

+ |

. |

+ |

1 |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

II |

0.6 |

| H |

End |

4 |

2 |

3 |

D |

Leucanthemum waldsteinii |

. |

. |

. |

. |

+ |

. |

+ |

. |

. |

. |

I |

0.1 |

| H |

Alp-E |

3.5 |

2.5 |

2.5 |

P |

Homogyne alpina |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

+ |

. |

. |

. |

I |

0.05 |

| Molinio-Arrhenatheretea |

| H |

Cp |

5 |

2 |

0 |

P |

Caltha palustris ssp. laeta |

. |

1 |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

. |

. |

IV |

0.8 |

| H(Hh) |

Eua |

5 |

3 |

0 |

P |

Myosotis scorpioides |

. |

+ |

. |

+ |

+ |

. |

+ |

+ |

. |

. |

III |

0.25 |

| H |

Cp |

5 |

3 |

0 |

DP |

Galium palustre |

. |

. |

. |

. |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

. |

. |

II |

0.2 |

| H |

Cosm |

4 |

0 |

0 |

DP |

Deschampsia caespitosa |

. |

+ |

+ |

+ |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

II |

0.15 |

| H |

Eua |

2.5 |

0 |

0 |

D |

Leontodon hispidus |

+ |

. |

+ |

+ |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

II |

0.15 |

| H |

Cosm |

3 |

3 |

0 |

P |

Prunella vulgaris |

+ |

. |

. |

+ |

. |

+ |

. |

. |

. |

. |

II |

0.15 |

| G |

E |

3.5 |

2 |

3 |

P |

Gymnadenia conopsea |

. |

+ |

. |

. |

+ |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

I |

0.1 |

| H(G) |

Eua |

4.5 |

0 |

4 |

P |

Agrostis gigantea ssp. gigantea |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

+ |

+ |

I |

0.1 |

| H |

Eua |

0 |

0 |

0 |

P |

Anthoxantum odoratum |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

+ |

. |

. |

. |

I |

0.05 |

| H |

E |

3 |

2 |

0 |

P |

Alchemilla vulgaris |

. |

. |

+ |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

I |

0.05 |

| TH |

Eua |

4.5 |

3 |

3 |

D |

Cirsium palustre |

. |

. |

. |

+ |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

I |

0.05 |

| G |

Cp |

5 |

2 |

0 |

P |

Equisetum palustre |

. |

. |

. |

. |

+ |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

I |

0.05 |

| Th |

E |

3 |

3 |

0 |

P |

Euphrasia stricta |

. |

. |

. |

. |

+ |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

I |

0.05 |

| H |

Cosm |

3,5 |

3 |

0 |

D |

Holcus lanatus |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

+ |

. |

. |

. |

. |

I |

0.05 |

| H |

Eua |

4 |

0 |

0 |

P |

Ranunculus repens |

. |

. |

. |

. |

+ |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

I |

0.05 |

| H |

Eua |

4 |

2,5 |

0 |

D |

Succisa pratensis |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

+ |

. |

I |

0.05 |

| Nardo-Callunetea |

| H |

Eua |

4 |

1 |

0 |

P |

Potentilla erecta |

+ |

. |

. |

. |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

IV |

0.35 |

| H |

E |

3.5 |

1.5 |

3 |

DP |

Crepis paludosa |

. |

+ |

+ |

. |

+ |

+ |

. |

. |

. |

. |

II |

0.2 |

| H |

E |

0 |

3 |

2 |

P |

Danthonia decumbens |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

+ |

+ |

I |

0.1 |

| H |

Eua |

4.5 |

2 |

0 |

DP |

Filipendula ulmaria |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

+ |

+ |

. |

. |

I |

0.1 |

| H |

E |

0 |

0 |

1.5 |

D |

Nardus stricta |

. |

. |

. |

. |

+ |

+ |

. |

. |

. |

. |

I |

0.1 |

| H |

Arct-Alp |

3.5 |

2 |

4 |

P |

Hieracium aurantiacum |

. |

. |

. |

+ |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

I |

0.05 |

| H |

Eua |

4 |

3 |

3 |

D |

Hypericum maculatum |

. |

. |

. |

+ |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

I |

0.05 |

| Ch |

Eua |

2 |

2 |

2 |

P |

Veronica officinalis |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

+ |

. |

. |

. |

I |

0.05 |

| Querco-Fagetea |

| mPh |

Eua |

4 |

3 |

3 |

DP |

Frangula alnus |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

+ |

. |

. |

I |

0.05 |

| Betulo-Adenostyletea |

| H |

Alp-Carp-B |

3.5 |

2 |

3 |

P |

Senecio subalpinus |

. |

+ |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

I |

0.05 |

| Montio-Cardaminetea |

| Hh |

Cp |

6 |

3 |

4.5 |

P |

Glyceria plicata |

. |

. |

. |

. |

+ |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

I |

0.05 |

| Nanocyperetalia |

| H(Hh) |

E |

4.5 |

2.5 |

0 |

D |

Juncus bulbosus |

. |

. |

. |

. |

+ |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

I |

0.05 |

References

- Pop, E. Peat bogs in the Romanian People’s Republic. Publishing House of the Academy of the Romanian People’s Republic, Bucharest, 1960.

- Pop, I., Cristea, V., Hodișan, I., Rațiu. O. Vegetation of the peat bogs from Blăjoaia and Dorna (upper course of the Someșului Rece valley, Cluj county). Contribuții Botanice magazine, Cluj-Napoca, 1986, pp. 123-129.

- Burescu, P., Togor, G. C. Phytocoenological studies on oligotrophy peat bog of Bihorului Mountains. Studia Universitatis ,,Vasile Goldiș,, Life Sciences Series, Issue 20, Arad, 2010; 2, 71-81.

- Pop, I.F, Burescu, L.I.N., Burescu-Morar, E.A., Vlad, I.A., 2023. Contributions to the phytocoenological study of oligo-mesotrophic peat bogs/marshy meadows in the Vlădeasa Mountains, Western Carpathians, Romania. Romanian Agricultural Research, 2023, NO.40/2023.

- Rațiu, O. Contributions to the knowledge of the vegetation in the Stâna de Vale basin, Contribuții Botanice Publishing House, Cluj-Napoca, 1965, pp. 151-175.

- Rațiu, O., Gergely I., Șuteu S., Marcu, A. Flora and phytosyntactic units from the Valea Iadului valley (Bihor County). Economic and scientific relevance. Ecological characterization II Contribuții Botanice, Cluj-Napoca, 1983; pp. 65-97.

- Pop, I., Hodișan I., Cristea, V. La vegetation de certaines tourbieres de la Valleé Izbuc (Depart. Cluj). (The vegetation of some peatlands of the Izbuc Valley (Cluj Dept.)). Contribuții Botanice magazine, Cluj-Napoca, 1987; pp. 111-120.

- Togor, G.C. Flora and vegetation in the northern Bihor Mountains. Doctoral thesis. University of Oradea, Romania, 2016.

- Cristea, M. Climatic risks in the Criș rivers basin, Abaddaba Publishing House, Oradea, 2004.

- Braun-Blanquet, J. Pflanzensoziologie (Plant sociology). Springer-Verlag, Wien-New York, 1964; 3, 12-24.

- Borza, A., Boșcaiu, N. An introduction to the study of the living soil cover. Publishing House of the Romanian Academy: Bucharest, 1965.

- Ivan, D., Doniță, N. Practical methods for ecologic and phytogeographically study of vegetation, University of Bucharest, 1975.

- Ivan, D., Spiridon, L. Phytocoenology and Vegetation of Romania. A practical courses guide. University of Bucharest, 1983.

- Ivan, D. Vegetation of Romania. Editura Tehnică Agricolă, Bucharest, 1992.

- Géhu, J.M. & Rivas-Martinez, S. Notions fondamentales de phytosociologie (Fundamentals of Phytosociology). In: Dierschke H., Syntaxonomy, Ber.Int.Symp.Int.Vereinigung Vegetationskunde. Cramer, Berlin, 1981; pp. 5-33.

- Tüxen, R. Das System der nordwestdeutschen Pflanzengesellschaften (The system of Northwest German plant communities), Mitt.D.Flour. Soz. Arbeitsgem.m.n., Germany, 1955 ; 5, 155-156.

- Soó, R. A maggyar flora és vegetácio rendszertani, növényföldrajzi kézikönyve (A systematic and phytogeographical manual of the Hungarian flora and vegetation). Acad. Kiado, I-VI, Budapest, 1964-1980.

- Oberdorfer, E. Süddeutche Pflanzengesellschaften (South German plant communities), III-Walder und Gebüsche. Gustav Fischer Verlag, J́ena, 1992.

- Pott, R. Die Pflanzengesellschaften Deutschlands (Plant communities of Germany), 2 Aufl, Welmer Verlug, Stuttgart, 1995.

- Borhidi, A. Critical revision of the Hungarian plants communities, Janus Pannonius Univerity Press, Pécs, 1996; pp. 43-94.

- Mucina, L. Conspectus of classes of European vegetation. Folia Geobot. Phytotax, Prahva, 1997; 32,117-172.

- Rodwell, J.S, Schamènée, J.H.J., Mucina, L., Pignatti, S., Dring, J́. & Moss, D. The diversity of European vegetation: An overview of phytosociological alliances and their relationships to EUNIS habitats. National Center for Agriculture, Nature Management and Fisheries, Wageningen, 2002.

- Sanda, V., Őllerer, K., Burescu, P. Phytocoenoses in Romania. Syntax, structure, dynamics and evolution. Ars Docendi Publishing House: University of Bucharest, Bucharest, 2008.

- Coldea, G., Oprea, A., Sârbu, I., Sârbu, C., Ștefan, N., The vegetable association of Romania. Cluj University, Press Publishing House: Cluj-Napoca, Cluj Napoca, 2012.

- Chifu, T., Irimia, I., Zamfirescu, O. Phytosociological diversity of Romania’s vegetation. Natural herbaceous vegetation. European Institute Publishing House: Iași, 2014.

- Raunkier, C. Plant life forms. Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1937.

- Ellenberg, H., Weber, H.E., Dull, R., Wirth, V., Werner, W., Paulisen, D. Indicator values of plants in Central Europe. Scripta Geobot., 1992; 18, 7-97.

- Sanda, V., Biță, N.C., Barabaș, N. Flora of spontaneous and cultivated cormophytes in Romania. Ion Borcea Publishing House: Bacău, Bacău, 2003.

- Burescu, P., Toma, I. Handbook of practical botany York. Publishing House of the University of Oradea, Oradea, 2005.

- Ciocârlan, V. The illustrated flora of Romania. Pteridophyta and Spermatophyta. Ceres Publishing House: Bucharest, Bucharest, 2009.

- Meusel, H. & Jäger, E. J́. Comparative Chorology of Central European Flora, 3. ˶Gustav Fischer Verlag˝ Publishing House: J́ena, Jena, 1992.

- Doniță, N., Popescu, A., Paucă-Comănescu, M., Mihăilescu, S., Biriș, I.A. Habitats in Romania. Changes according to the amendments proposed by Romania and Bulgaria at Habitats Directive (92/43/EEC). Tehnică Silvică Publishing House, Bucharest, 2006.

- Sârbu, A., Sârbu I., Oprea, A., Negrean, G., Cristea, V., Coldea, G., Cristurean, I., Popescu, G., Oroian, S., …, Stan, I., Frink, J. Special areas for the protection and conservation of plants in Romania. Victor B Victor Publishing House, București, 2007.

- Dihoru, Gh., Negrean, G. Red list of vascular plants from Romania. Publishing House: Academy of the Romanian People’s Republic, Bucharest, 2009.

- Bilz, M., Kell, S.P., Maxted, N., Lansdown, R.V. European Red List of Vascular Plants, Publication Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2011.

- Oltean, M., Negrean, G., Popescu, A., Roman, N., Dihoru, G., Sanda, V., Mihăilescu, S. Red plant list of superior plants from Romania Stud. Sint. Doc. Ecol., Acad. Romn., București, 1994, 1, 1-52.

- Gafta, D., Mountford, J.O. (coord.), Alexiu, V., Anastasiu, P., Bărbos, M., Burescu, P., Coldea, Gh., Drăgulescu, C., Șuteu, A. Interpretation manual of NATURA2000 habitats in Romania, Risoprint Publishing House, Cluj-Napoca, 2008.

- Boșcaiu, N., Coldea, Gh., Horeanu, C. The Red list of extinct, endangered, vulnerable and rare vascular plants from Romania's flora, Ocrot. Nat. Med. Înconj., Bucharest; 1994; 1, 45-56.

- Dihoru, Gh., Dihoru, A. Rare, endangered and endemic plants from Romania's flora - Red List. Acta Bot. Horti Bucuresti (1993-1994), Bucharest, 1994; pp. 173-197.

- Oprea, A. Critical list of vascular plants from Romania, “Al. I. Cuza” University Press; Iași, 2005.

Figure 2.

Carici echinatae-Sphagnetum (Balázs 1942) Soó 1955, Nimăiasa Mountain (original: 21.08.2021).

Figure 2.

Carici echinatae-Sphagnetum (Balázs 1942) Soó 1955, Nimăiasa Mountain (original: 21.08.2021).

Figure 3.

Spectrum of bioforms from the association Carici echinatae-Sphagnetum (Balázs 1942) Soó 1955.

Figure 3.

Spectrum of bioforms from the association Carici echinatae-Sphagnetum (Balázs 1942) Soó 1955.

Figure 4.

Spectrum of phytogeographic elements in the association Carici echinatae-Sphagnetum (Balázs 1942) Soó 1955.

Figure 4.

Spectrum of phytogeographic elements in the association Carici echinatae-Sphagnetum (Balázs 1942) Soó 1955.

Figure 5.

Ecological index diagram for the association Carici echinatae-Sphagnetum (Balázs 1942) Soó 1955.

Figure 5.

Ecological index diagram for the association Carici echinatae-Sphagnetum (Balázs 1942) Soó 1955.

Figure 6.

The karyological spectrum of the association Carici echinatae-Sphagnetum (Balázs 1942) Soó 1955.

Figure 6.

The karyological spectrum of the association Carici echinatae-Sphagnetum (Balázs 1942) Soó 1955.

Figure 7.

Căpățânii swamps (28.08.2020), GPS: latitude: 46°29’07’’N, longitude: 23°07’44’’E original.

Figure 7.

Căpățânii swamps (28.08.2020), GPS: latitude: 46°29’07’’N, longitude: 23°07’44’’E original.

Figure 8.

Vârful Băii peak (28.08.2022), GPS: latitude: 46°29’08’’ N, longitude: 23°07’45’’E, original.

Figure 8.

Vârful Băii peak (28.08.2022), GPS: latitude: 46°29’08’’ N, longitude: 23°07’45’’E, original.

Table 1.

Ecological indices for the association Carici echinatae-Sphagnetum (Balázs 1942) Soó 1955.

Table 1.

Ecological indices for the association Carici echinatae-Sphagnetum (Balázs 1942) Soó 1955.

| Ecological indices |

1 |

1.5 |

2 |

2.5 |

3 |

3.5 |

4 |

4.5 |

5 |

6 |

0 |

Total species |

| M |

sp. no. |

- |

- |

1 |

1 |

4 |

6 |

10 |

10 |

14 |

1 |

3 |

50 |

| % |

- |

- |

2 |

2 |

8 |

12 |

20 |

20 |

28 |

2 |

6 |

100 |

| T |

sp. no. |

1 |

2 |

18 |

5 |

15 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

9 |

50 |

| % |

2 |

4 |

36 |

10 |

30 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

18 |

100 |

| R |

sp. no. |

4 |

11 |

10 |

6 |

- |

- |

19 |

50 |

| % |

8 |

22 |

20 |

12 |

- |

- |

38 |

100 |

Table 2.

Current status and in situ conservation status of vascular plant biodiversity in peat bogs of the Apuseni Mountains, Romania.

Table 2.

Current status and in situ conservation status of vascular plant biodiversity in peat bogs of the Apuseni Mountains, Romania.

| No. |

Species |

Sites no. |

Sozological categories of protection according to bibliographic sources |

| [36] |

[35] |

[40] |

[34] |

| 1 |

Andromeda polifolia L. |

1 |

R, RG |

|

|

|

| 2 |

Carex limosa L. |

3 |

R, RG |

LC |

NT |

|

| 3 |

Carex magellanica ssp. irrigua Hiitonen |

1 |

R, RG |

|

NT |

|

| 4 |

Carex pauciflora Lightf |

3 |

RG |

|

|

|

| 5 |

Dactylorhiza cordigera (Fr.) Soó |

1 |

R |

LC |

NT |

|

| 6 |

Dactylorhiza maculata (L.) Soó |

1 |

R, NT |

LC |

|

|

| 7 |

Drosera intermedia Hayne |

1 |

RG, CR |

|

CR |

CR |

| 8 |

Drosera rotundifolia L. |

4 |

R, RG |

|

NT |

|

| 9 |

Dryopteris cristata (L.) A.Gray |

1 |

R, RG |

|

|

NT |

| 10 |

Dryopteris dilatata (Hoffm.) A.Gray |

1 |

|

|

LC |

|

| 11 |

Empetrum nigrum L. |

3 |

R, RG |

|

NT |

|

| 12 |

Epilobium nutans F.W. Schmidt |

1 |

R |

|

|

|

| 13 |

Eriophorum scheuchzeri Hoope |

2 |

R |

LC |

NT |

|

| 14 |

Eriophorum vaginatum L. |

6 |

RG |

|

|

|

| 15 |

Gymnadenia conopsea (L.) R.Br. |

2 |

R |

LC |

NT |

|

| 16 |

Lycopodium inundatum L. |

2 |

R, RG |

LC |

NT |

NT |

| 17 |

Menyanthes trifoliata L. |

2 |

R |

|

NT |

|

| 18 |

Pedicularis limnogena A.Kern. |

4 |

VU |

|

VU |

LR |

| 19 |

Rhynchospora alba (L.) Vahl. |

1 |

R, RG |

|

VU |

VU |

| 20 |

Scheuchzeria palustris L. |

3 |

VU, RG |

|

VU |

|

| 21 |

Swertia punctata Baumg. |

1 |

R, RG |

|

NT |

|

| 22 |

Vaccinium microcarpum (Rupr.) Schmalh |

2 |

R |

|

NT |

|

| 23 |

Vaccinium oxycoccos L. |

2 |

R |

|

NT |

|

Table 3.

The comparative spectrum of the ecological indices (M=soil moisture, T=air temperature, R=chemical reaction of the soil) for the phytocoenoses of the Carici echinatae-Sphagnetum association analysed separately from the regions of the Vlădeasa Massif, Bihor. Mountains, and Gilău Mountains.

Table 3.

The comparative spectrum of the ecological indices (M=soil moisture, T=air temperature, R=chemical reaction of the soil) for the phytocoenoses of the Carici echinatae-Sphagnetum association analysed separately from the regions of the Vlădeasa Massif, Bihor. Mountains, and Gilău Mountains.

| Place |

Ecological indices |

Level of ecological indices and number of species/% |

| 1 |

1.5 |

2 |

2.5 |

3 |

3.5 |

4 |

4.5 |

5 |

6 |

0 |

| Raised bogs of Vlădeasa Massif |

M (Sp. No)

(%) |

- |

- |

1 |

1 |

4 |

6 |

10 |

10 |

14 |

1 |

3 |

| - |

- |

2 |

2 |

8 |

12 |

20 |

20 |

28 |

2 |

6 |

T (Sp. No.)

(%) |

1 |

2 |

18 |

5 |

15 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

9 |

| 2 |

4 |

36 |

10 |

30 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

18 |

R (Sp. No).

(%) |

4 |

11 |

10 |

6 |

- |

- |

19 |

| 8 |

22 |

20 |

12 |

- |

- |

38 |

|

Raised bogs of Padiș Plateau, Bihor Mountains [8] |

M (Sp. No.)

(%) |

- |

- |

- |

- |

8 |

15 |

13 |

- |

5 |

| - |

- |

- |

- |

20 |

36.59 |

31.71 |

- |

12 |

T (Sp. No.)

(%) |

- |

- |

23 |

10 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

8 |

| - |

- |

56 |

24 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

20 |

R (Sp. No.)

(%) |

9 |

14 |

- |

8 |

- |

- |

10 |

| 21.95 |

34.15 |

- |

19.51 |

- |

- |

24.39 |

|

Raised bogs of Blăjoaia, Gilău Mountains [2] |

M (Sp. No.)

(%) |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

3 |

5 |

14 |

- |

4 |

| - |

- |

- |

- |

- |

3.7 |

11.1 |

18.5 |

51.8 |

- |

14.8 |

T (Sp. No.)

(%) |

- |

- |

14 |

2 |

5 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

6 |

| - |

- |

51.8 |

7.4 |

18.5 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

22.2 |

R (Sp. No.)

(%) |

7 |

9 |

5 |

1 |

- |

- |

5 |

| 25.9 |

33.3 |

18.5 |

3.7 |

- |

- |

18.5 |

Table 4.

Comparative spectrum of bioforms for the phytocoenoses of the Carici echinatae-Sphagnetum association analysed separately for the habitats of the Vlădeasa Massif, Bihor Mountains, and Gilău Mountains.

Table 4.

Comparative spectrum of bioforms for the phytocoenoses of the Carici echinatae-Sphagnetum association analysed separately for the habitats of the Vlădeasa Massif, Bihor Mountains, and Gilău Mountains.

| Place |

Bioforms |

H |

Brchs |

G |

Hh |

T |

Ch |

mPh |

Total species |

| TH |

Th |

| Raised bogs of Vlădeasa Massif |

Sp. no. |

37 |

6 |

5 |

4 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

56 |

| Percentage (%) |

66.1 |

10.7 |

8.9 |

7.1 |

1.8 |

1.8 |

1.8 |

1.8 |

|

Raised bogs of Padiș Plateau, Bihor Mountains [8] |

Sp. no. |

29 |

8 |

8 |

- |

- |

- |

3 |

1 |

49 |

| Percentage (%) |

70.73 |

16.2 |

19.51 |

- |

- |

- |

7.32 |

2.44 |

|

Raised bog of Blăjoaia, Gilău Mountains [2] |

Sp. no. |

12 |

5 |

- |

2 |

- |

- |

8 |

- |

27 |

| Percentage (%) |

55.5 |

18.5 |

- |

7.4 |

- |

- |

37.0 |

- |

Table 5.

Comparative spectrum of the phytogeographic elements for the phytocoenoses of the Carici echinatae-Sphagnetum association analysed separately from the Vlădeasa Massif, Bihor Mountains, and Gilău Mountains regions.

Table 5.

Comparative spectrum of the phytogeographic elements for the phytocoenoses of the Carici echinatae-Sphagnetum association analysed separately from the Vlădeasa Massif, Bihor Mountains, and Gilău Mountains regions.

| Place |

Phytogeographic elements |

Cp |

Cp-Bo |

Eua |

E |

Ec |

Alp-E |

Arct-Alp |

Alp-Carp-B |

Carp-B |

Carp-B-Cauc |

D |

End |

Cosm |

| Raised bogs of Vlădeasa Massif |

Species no. |

16 |

2 |

14 |

9 |

- |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

6 |

| Percentage (%) |

28.6 |

3.6 |

25 |

16.1 |

- |

3.6 |

3.6 |

1.8 |

1.8 |

1.8 |

1.8 |

1.8 |

10.7 |

|

Raised bogs of Padiș Plateau, Bihor Mountains [8] |

Species no. |

14 |

5 |

11 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

3 |

| Percentage (%) |

34.1 |

12.1 |

25.3 |

4.8 |

2.4 |

2.4 |

2.4 |

2.4 |

2.4 |

- |

2.4 |

- |

7.3 |

|

Raised bogs of Blăjoaia, Gilău Mountains [2] |

Species no. |

10 |

4 |

4 |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

3 |

| Percentage (%) |

45.4 |

18.1 |

18.1 |

4.5 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

13.6 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).