1. Introduction

Large rotors are an important part of many industrial equipment, widely used in power generation, aerospace, metallurgy, chemical industry, mining and other fields [

1,

2]. Since the rotor experiences enormous stress and centrifugal force during high-speed rotation, the rotor steel must have sufficiently high yield strength and tensile strength to prevent plastic deformation and fracture. The medium-carbon, low-alloy Cr -Ni-Mo-V steel has excellent mechanical properties and good workability and is often used in various large rotors [

3]. Its excellent mechanical properties are mainly due to the strengthening of the alloying elements and the complex microstructure formed during heat treatment. Tempering treatment, as a common heat treatment process, can effectively adjust the microstructure of the material and optimize its performance by controlling the tempering temperature and holding time [

4].

During the tempering process, the microstructure of the Cr–Ni–Mo–V rotor steel undergoes several transformation processes. In particular, the martensite formed after quenching decomposes with increasing tempering temperature and forms tempered martensite. In addition, the change in shape of the carbide is one of the important factors that affect the tempering temperature on the properties of Cr–Ni–Mo–V rotor steel [

5,

6]. Tempering at high temperatures usually promotes the formation of large carbides, while tempering at low temperatures contributes to the refinement of these carbides, which in turn affects the mechanical properties of the material [

7]. Although a large number of publications have discussed the effects of tempering temperature on the properties of Cr–Ni–Mo–V rotor steel [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12], there is still a lack of systematic research on the subtle mechanism between tempering temperature and microstructure.

At different tempering temperatures, the change in the matrix and the precipitated phase of the steel has a considerable influence on its properties. In general, the strength of the steel is high and the plasticity is low at low tempering temperatures. The higher the tempering temperature, the lower the strength of the steel, but the higher the toughness [

13]. Therefore, the choice of appropriate tempering temperature to compensate for the strong plasticity of Cr–Ni–Mo–V rotor steel has become a key problem to be solved in its application. However, the mechanism of the influence of tempering temperature on the microstructure and properties of Cr–Ni–Mo–V rotor steel is still controversial. In existing studies, the mechanical properties of Cr–Ni–Mo–V rotor steel generally decrease with the increase of tempering temperature, mainly because the dislocation density of the matrix decreases and the coarsening of carbide precipitation leads to a weakening of the dislocation strengthening and solution strengthening effects [

14,

15,

16]. However, some studies have found that the secondary strengthening effect of Cr–Ni–Mo–V rotor steel usually occurs with the increase of tempering temperature, which is mainly influenced by the precipitation and strengthening of carbide [

17,

18,

19]. Therefore, it is of great theoretical significance and technical benefit to investigate the influence mechanism of microstructure evolution on the properties of Cr–Ni–Mo–V rotor steel during tempering.

The aim of this study is to systematically analyze the evolution of the microstructure and mechanical properties of Cr–Ni–Mo–V rotor steel at different tempering temperatures and to reveal the mechanism of the influence of tempering temperature on the properties of Cr–Ni–Mo–V rotor steel. Specifically, in this study, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), X-ray diffraction (XRD) and other characterization techniques are used in combination with mechanical property testing to investigate the influence of tempering temperature on the microstructure evolution of Cr–Ni–Mo–V rotor steel and further clarify the mechanism of the influence of tempering temperature on the mechanical properties of the steel. The aim of this research is to provide a theoretical basis for optimizing the heat treatment process of Cr–Ni–Mo–V rotor steel and to promote its wide application in the field of large rotors.

2. Materials and Methods

In this test, the Cr–Ni–Mo–V rotor steel material was taken from the annealed physical rotor after forging, and its specific chemical composition is shown in

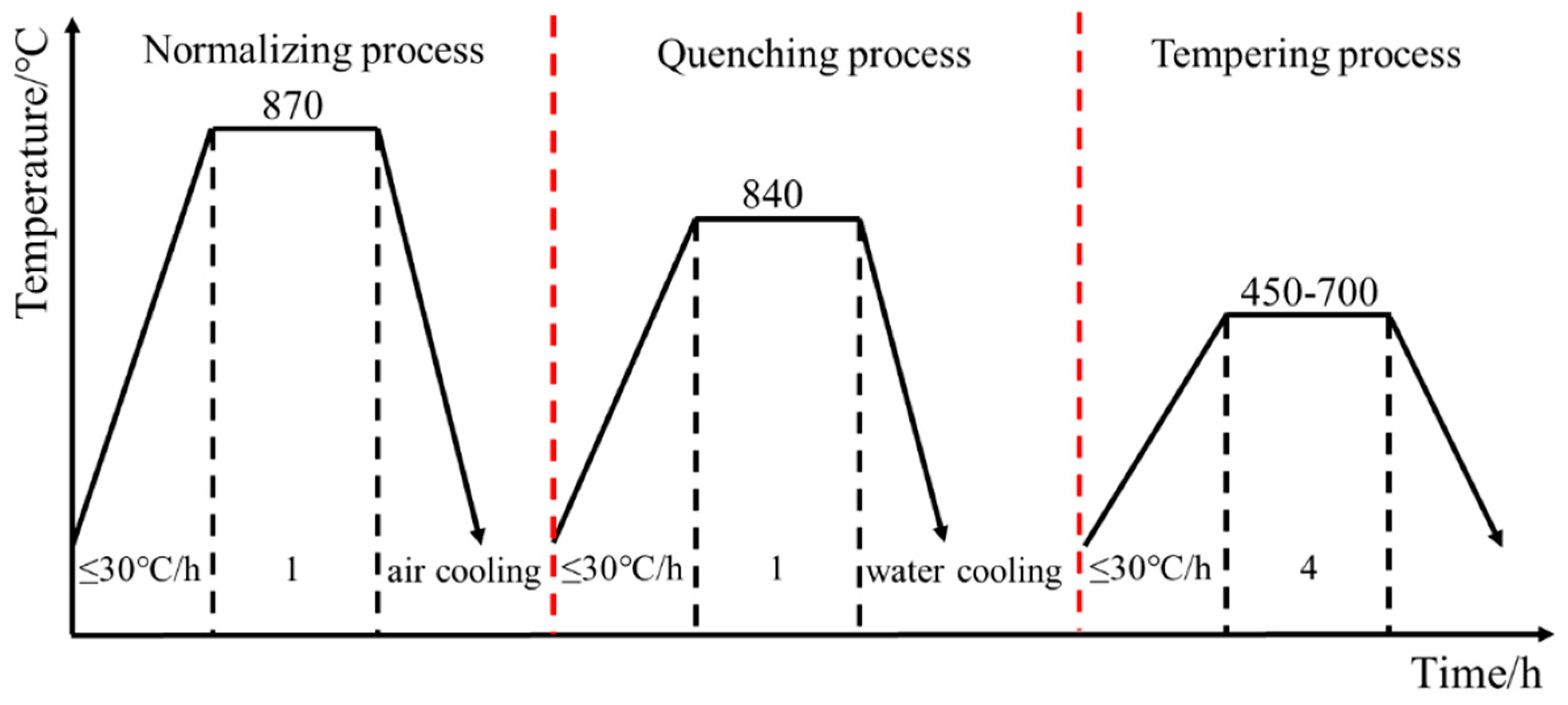

Table 1. The heat treatment process of Cr–Ni–Mo–V rotor steel is shown in

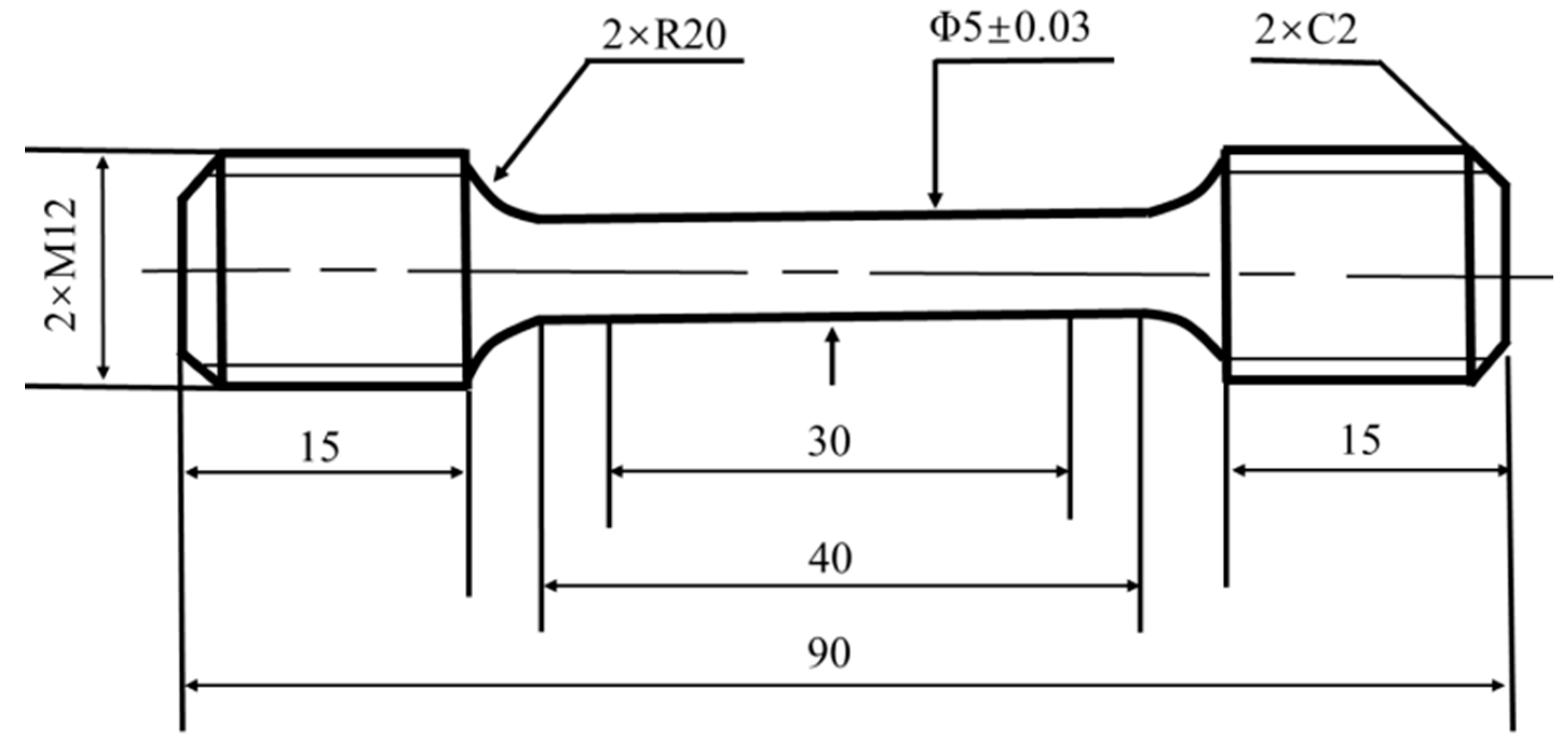

Figure 1. After the end of heat treatment, the bar material tempered at different temperatures was processed into tensile specimens at room temperature, as shown in

Figure 2.

The microstructure was analyzed with the scanning electron microscope JSM-7001F (SEM). The SEM specimen was mechanically ground, polished and then etched in a 4% nitroalcohol solution. The microstructure of Cr–Ni–Mo–V rotor steel was characterized using the Tecnai F30 transmission electron microscope (TEM). A TEM specimen with a thickness of 60 μm was hand-ground with sandpaper and then punched into a disk with a diameter of 3 mm. Finally, the disk was further thinned by dual-beam electropolishing with an 8% by volume perchlorate-ethanol solution at about -20 ◦C and a voltage of 40 V. The hardened Cr–Ni–Mo–V rotor steel samples were cut with a surface area of 10×10×10mm, sandpaper and mechanically polished, and XRD analysis was performed. The scanning angle 2θ was 10~100°, and the scanning speed was 4°/min. The XRD results were calibrated using MDI Jade5.0 software to determine the distance between the crystal faces of the sample. The tensile properties of the samples were tested by Z600E 600N electronic tensile testing machine according to GB/T 228.1-2010, and then the fracture morphology was observed by SEM.

3. Results and Discussion

Authors should discuss the results and how they can be interpreted from the perspective of previous studies and of the working hypotheses. The findings and their implications should be discussed in the broadest context possible. Future research directions may also be highlighted.

3.1. Mechanical Properties After Quenching and Tempering

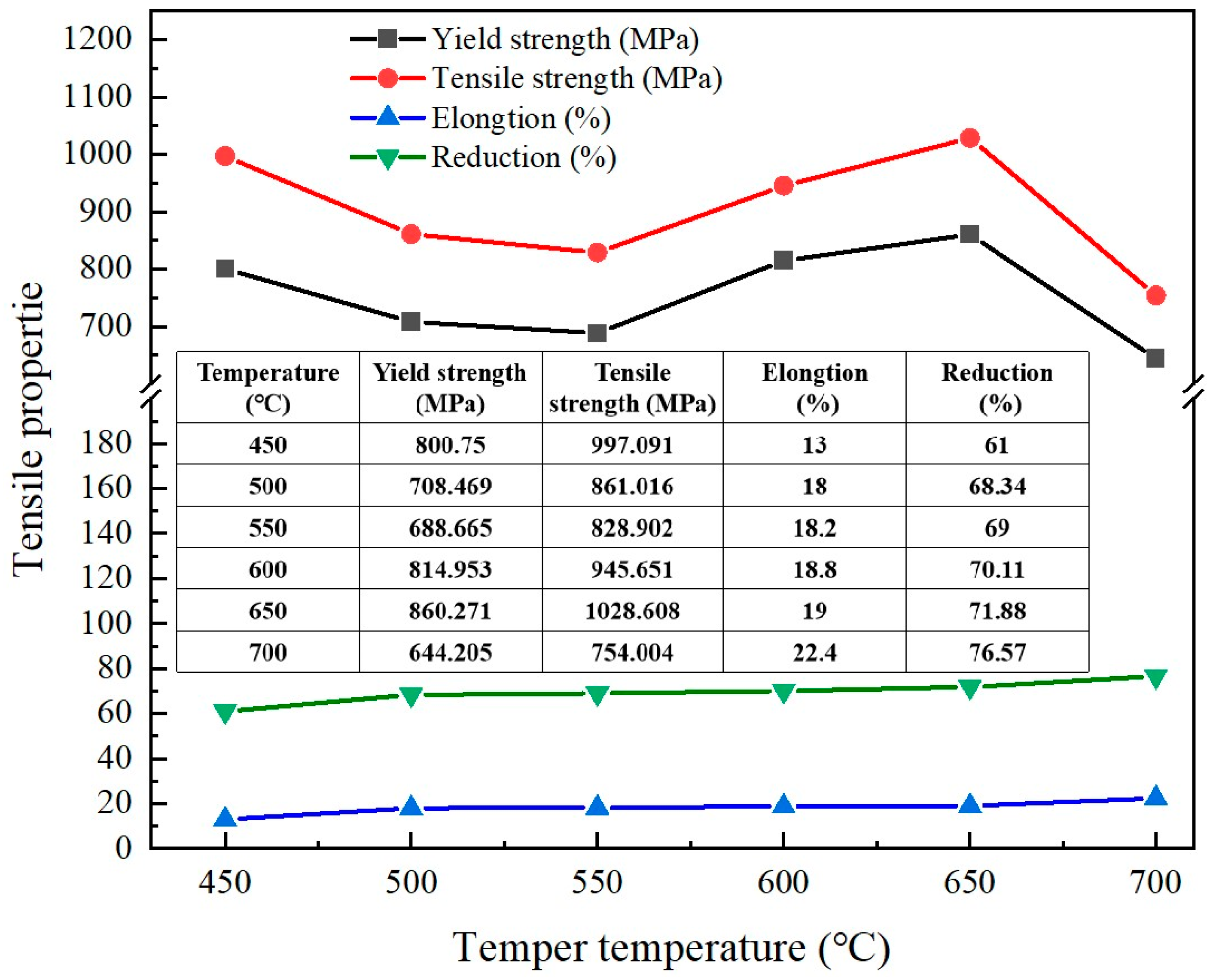

Figure 3 shows the mechanical tensile properties of Cr–Ni–Mo–V rotor steel at room temperature under different tempering conditions. As can be seen from

Figure 3, as the tempering temperature increases from 450 ℃ to 700 ℃, the tensile strength and yield strength first decrease, then increase, and then decrease again, while the elongation and section shrinkage show a gradually increasing trend, which is mainly related to the martensitic recovery and recrystallization of Cr–Ni–Mo–V rotor steel sheet and the dissolution and precipitation of carbide. In the range of 450 ℃ to 550 ℃, the tensile strength and yield strength decrease from 997.091MPa and 800.75MPa to 828.902MPa and 688.655MPa, respectively, and the elongation and section shrinkage increase from 13% and 61% to 18.2% and 69%, respectively. In the range of 550-650 ℃, the tensile strength and yield strength increase to 1028.608MPa and 860.271MPa, respectively, and the elongation and cross-sectional shrinkage increase to 19% and 71.88%, respectively. In the range of 650-700 ℃, the tensile strength and yield strength decrease to 754.004MPa and 644.205MPa, respectively, and the elongation and cross-sectional shrinkage increase to 22.4% and 76.57%, respectively. The comprehensive mechanical properties show that the Cr–Ni–Mo–V rotor steel has the best comprehensive mechanical properties when it is tempered at 650 ℃. This may be related to the recovery and recrystallization of martensitic lamellae in the microstructure of Cr–Ni–Mo–V rotor steel and the evolution of the type and volume of carbides [

20,

21].

3.2. Microstructure Evolution During Tempering

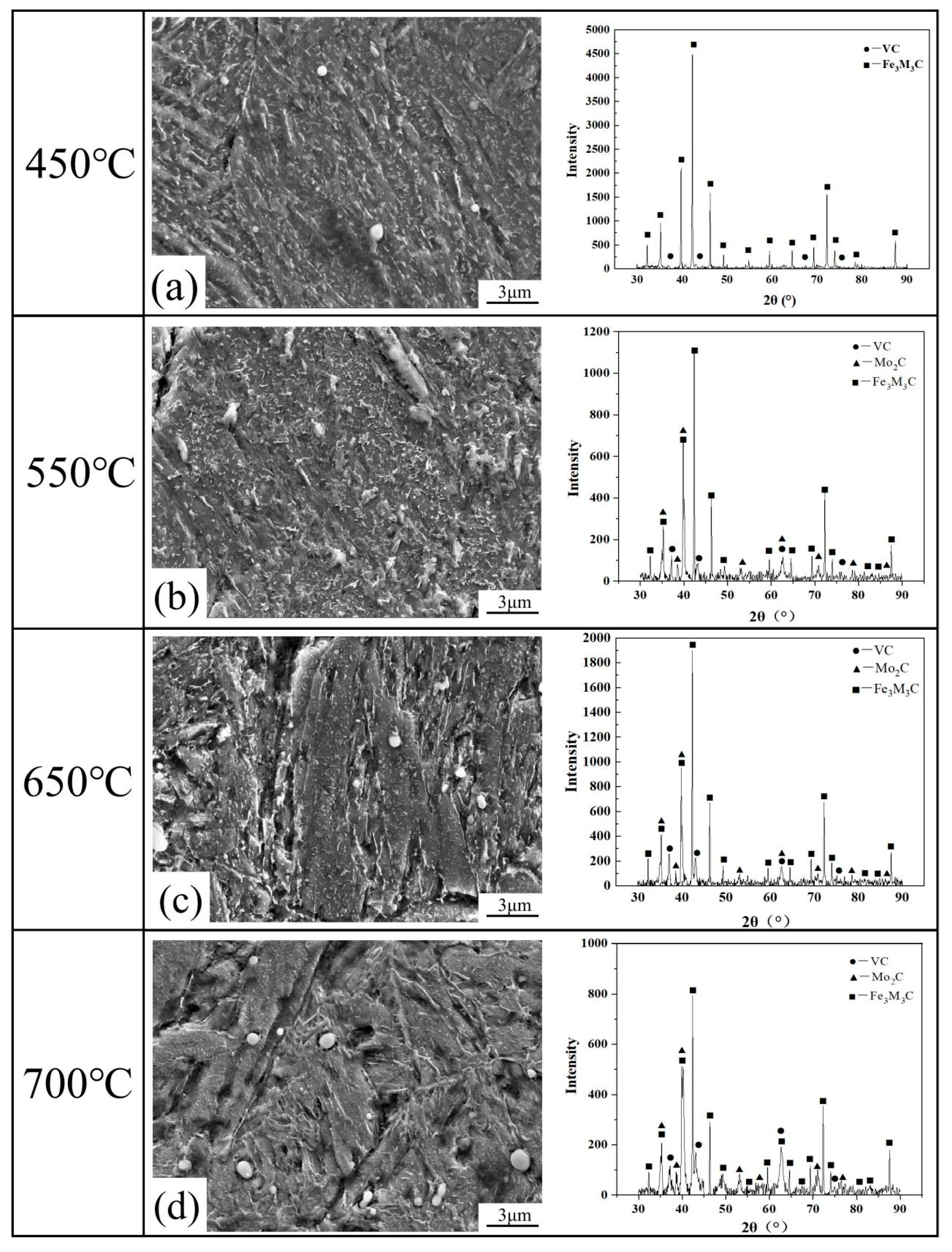

The SEM microstructure and carbide energy spectrum analysis of Cr–Ni–Mo–V rotor steel at different tempering temperatures are shown in

Figure 4. From

Figure 4(a), it can be seen that at an annealing temperature of 450 ℃, the microstructure of Cr–Ni–Mo–V rotor steel consists of lath martensite, a large amount of rod-shaped Fe3Mo3C and a small amount of spherical VC. From

Figure 4(b), it can be seen that when the temperature rises to 550 ℃, a large amount of rod-shaped Fe3Mo3C in Cr–Ni–Mo–V rotor steel is distributed in the grain boundary and a small amount of VC and Mo2C is distributed in the grain. Compared to 450 ℃, the content and volume of Fe3Mo3C in the tempered microstructure increased at 550 ℃, and it was concluded that a large amount of Fe3Mo3C precipitated and grew in this temperature range. From

Figure 4(c), it can be seen that when the temperature increases to 650 ℃, the content of Fe3Mo3C decreases significantly, while a large amount of VC and Mo2C is dispersed out. From

Figure 4(d), it can be seen that when the temperature rises to 700 ℃, the content of Fe3Mo3C in the matrix is low and VC and Mo2C are gradually coarsened and the precipitation promoting effect on Cr–Ni–Mo–V rotor steel is weakened.

In summary, in the tempering range from 450 ℃ to 550 ℃, a large amount of Fe3Mo3C and a small amount of VC and Mo2C are precipitated from the matrix, indicating that the decrease in strength in this temperature range may be related to the weakening of solution strength [

22]. In the tempering range from 550 ℃ to 650 ℃, the amount of Fe3Mo3C in the matrix decreases and the amount of VC and Mo2C increases, suggesting that the increase in strength may be related to precipitation hardening. In the tempering range from 650 ℃ to 700 ℃, the amount of Fe3Mo3C in the matrix is low and the amount of VC and Mo2C increases, suggesting that the decrease in strength is related to the weakening of precipitation hardening [

23].

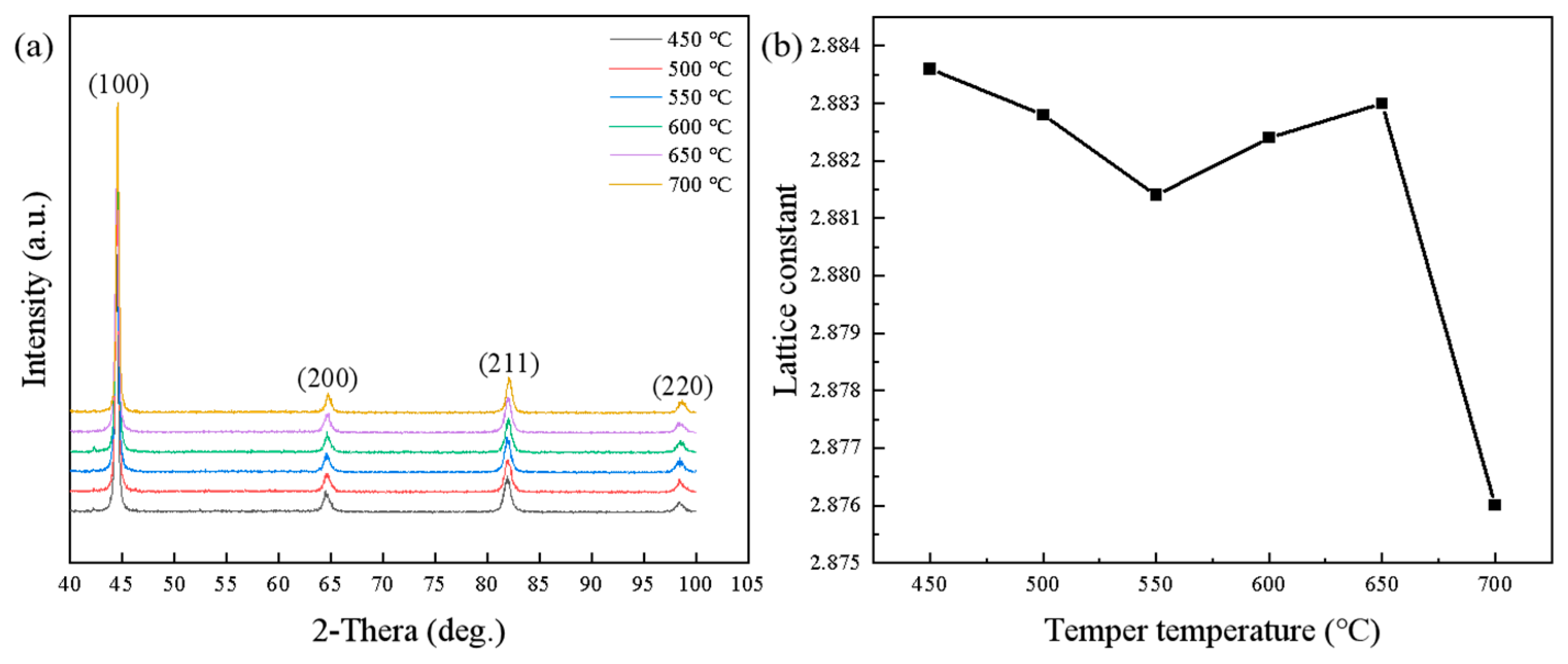

Figure 5 shows the changes in the lattice constant of alpha-Fe in Cr–Ni–Mo–V rotor steel at different tempering temperatures. From

Figure 5(b), it can be seen that the crystal face spacing of the matrix has a decreasing trend when tempered at 450 ℃-550 ℃, an increasing trend when tempered at 550 ℃-650 ℃, and a decreasing trend when tempered at 650 ℃-700 ℃, which is basically consistent with the changing trend of strength with tempering temperature. The change of crystal face spacing of the matrix also reflects the solid solution and precipitation of alloying elements, which is also confirmed by the precipitation and resolution law of Fe3Mo3C carbide in the matrix and the precipitation and coarsening law of VC and Mo2C carbide in

Figure 4.

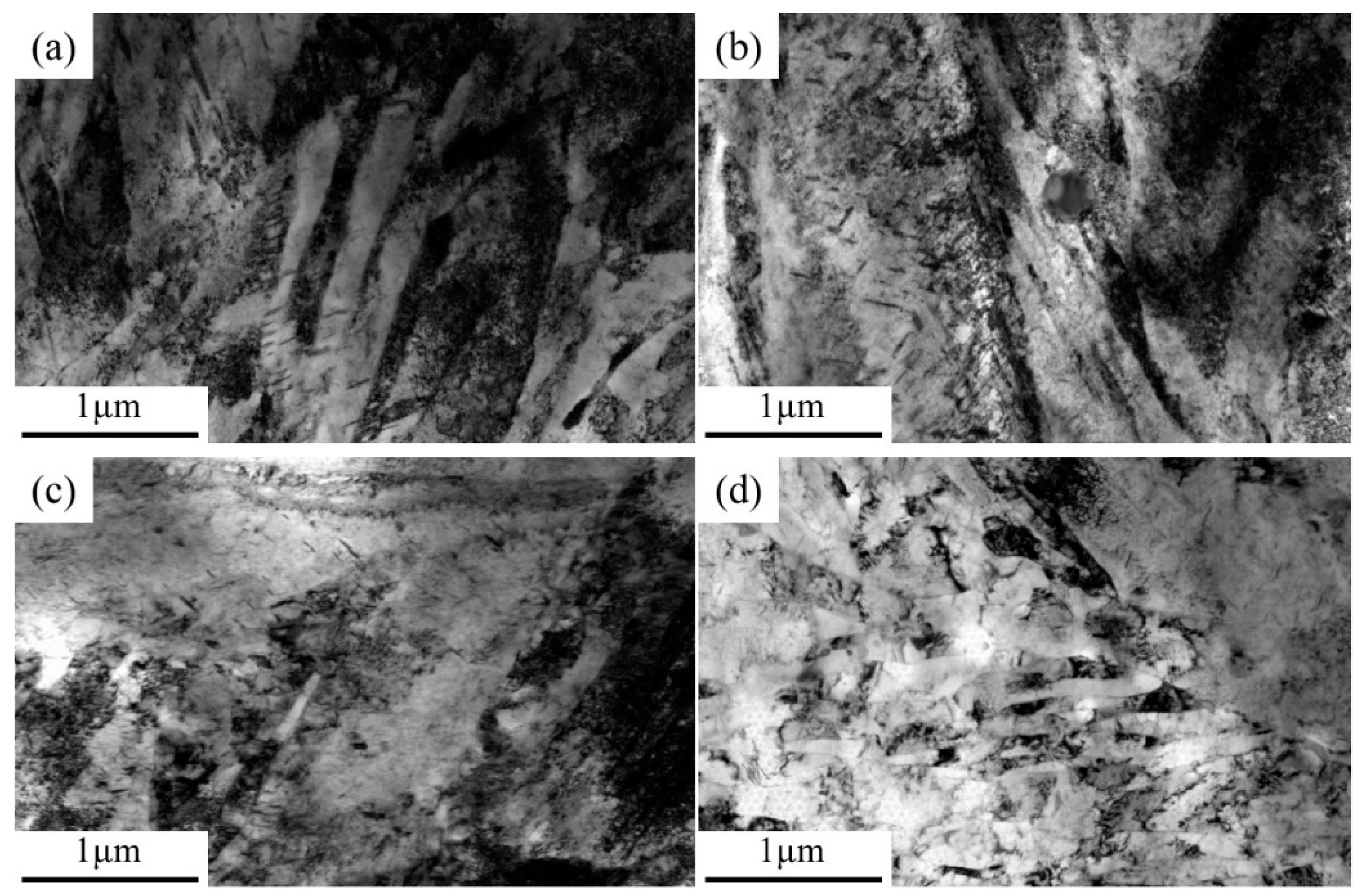

Figure 6 shows the TEM microstructure of Cr–Ni–Mo–V rotor steel at different tempering temperatures. From

Figure 6(a), under the tempering condition of 450 ℃, the martensitic lattice microstructure in Cr–Ni–Mo–V rotor steel is still the main microstructure form, with a large number of rod-shaped carbides distributed in the grain boundaries and a small number of spherical carbides distributed in the martensitic lattice and boundary, which corresponds to

Figure 4(a). In addition, dislocation proliferation and entanglement occur near the carbides, and low recovery of the martensite lamella leads to a high dislocation density [

24]. The obstruction of dislocation movement by the carbide and the high dislocation density in the martensitic lamellae therefore favor the maintenance of a high strength of the material [

25]. From

Figure 6(b), it can be seen that when the tempering temperature increases to 550 ℃, a large amount of rod-shaped Fe3Mo3C precipitates at the grain boundary, and a small amount of spherical VC and Mo2C in the grains leads to a weakening of the strengthening effect of the solution, in which the hindering effect of dislocation is weakened by the increase in the volume of Fe3Mo3C and the dislocation density decreases due to the higher degree of martensitic recovery of Lat. Therefore, the strength of Cr–Ni–Mo–V rotor steel decreases as a result of solution strengthening, dislocation strengthening and precipitation strengthening.

Figure 6(c) shows that cellular structures were formed during tempering at 650 ℃ due to the local recrystallization of martensitic laths, which leads to a decrease in dislocation density. In particular, the dissolution of rod-shaped Fe3Mo3C led to an increased strength increase of the matrix in solid solution, while the diffusion of spherical VC and Mo2C increased the hindrance of dislocations [

26]. Therefore, the strength of Cr–Ni–Mo–V rotor steel increases with the enhancement of solution strength and precipitation strength. It can be seen from

Figure 6(d) that when the tempering temperature increases to 700 ℃, almost all martensitic lamellae recrystallize and form cellular structures, which leads to a further reduction in dislocation density. At the same time, the high tempering temperature leads to excessive precipitation and growth of VC, Mo2C and Fe3Mo3C carbides [

27]. Therefore, strengthening by dislocation, strengthening by solution and strengthening by precipitation are weakened simultaneously, resulting in a significant decrease in material strength. The above microstructural changes can clearly explain the evolution of the mechanical properties of Cr–Ni–Mo–V rotor steel at different tempering temperatures (

Figure 3).

3.3. Fracture Morphology

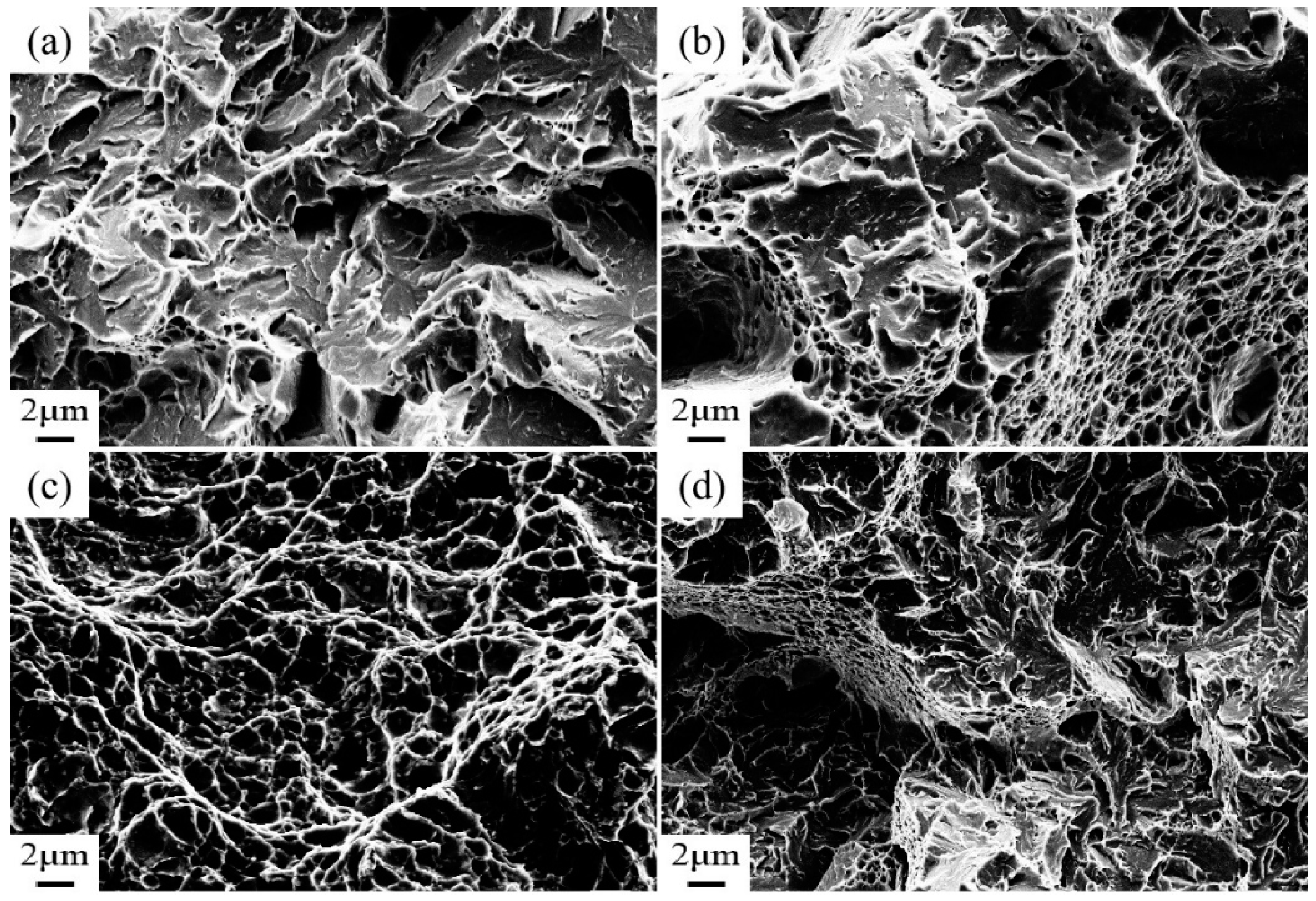

The microstructure of fracture of Cr–Ni–Mo–V rotor steel tensile specimens at different temperatures is shown in

Figure 7. As shown in

Figure 7(a), the microcracks at the tempering temperature of 450 ℃ mainly propagate through the grain boundaries or within the grains without significant plastic deformation regions. The tensile fracture is mainly a brittle fracture, which has the characteristics of a transgranular fracture with flat or small crack extension. When the tempering temperature increases to 550 ℃, as shown in

Figure 7(b), most of the fracture surface is a brittle fracture with transgranular crack and grain boundary fracture, accompanied by small local plastic deformation of the dimpling structure. The tensile fracture exhibits a quasi-brittle fracture. Compared to tempering at 450 °C, the fracture at tempering at 550 °C may exhibit more grain boundary fractures, and small dimple structures may appear locally, indicating a slight improvement in plasticity but not a significant ductile fracture pattern. As shown in

Figure 7(c), when the tempering temperature increases to 650 ℃, the fracture has an obvious dimple structure, and the dimple shape is deep but small, showing an obvious ductile fracture. When the tempering temperature increases to 700 ℃, the tensile fracture properties still remain ductile, and the fracture surface still has a dimple structure, but the dimple shape becomes shallow and large. To summarize, when the tempering temperature increases from 450 ℃ to 700 ℃, the tensile fracture properties of Cr–Ni–Mo–V rotor steel gradually change from cleavage fracture to dimple fracture.

From

Figure 4(a) and

Figure 6(a), it can be seen that when tempering at 450 ℃, a large amount of Fe3Mo3C at the grain boundary easily causes stress concentration, which leads to crack initiation and propagation, and a low elongation and cross-sectional shrinkage lead to insufficient plastic deformation [

28]. Therefore, the microcracks start at the grain boundary and then break intergranularly or transgranularly. It can be seen from

Figure 4(b) and

Figure 6(b) that during tempering at 550 ℃, a large amount of Fe3Mo3C gradually grows at the grain boundaries and martensitic lath boundaries, the dislocation density within the grains decreases, and the precipitation of alloying elements weakens the effect of solution strength and dislocation strength [

29]. Therefore, microcracks can occur simultaneously at the grain boundary and inside the grain, leading to a quasi-crack fracture. As shown in

Figure 4(c) and

Figure 6(c), Fe3Mo3C recirculation at the grain boundary and martensite lath enhances solid solution strengthening of the matrix, and spherical VC and Mo2C precipitate in large amounts at the martensite lath boundary. Therefore, the microcrack can easily occur in the grain, and the high strain and cross-sectional shrinkage make the microstructure susceptible to local plastic deformation, so the fracture is a pitting fracture [

30]. It can be seen from

Figure 4(d) and

Figure 6(d) that during tempering at 700 ℃, spherical VC and Mo2C are gradually coarsened at the boundary of the martensite lamellae, which is conducive to crack initiation and propagation. Therefore, the dimple shape becomes flatter and larger compared to the tensile fracture after tempering at 650 ℃.

4. Conclusions

This section is not mandatory but can be added to the manuscript if the discussion is unusually long or complex.

(1) The microstructure of the Cr–Ni–Mo–V rotor steel in this work is mainly tempered martensite. With the increase of tempering temperature, tensile strength and yield strength first decrease, then increase and then decrease again, while elongation and section shrinkage gradually increase, with 650 ℃ having the best comprehensive mechanical properties.

(2) The strength of Cr–Ni–Mo–V rotor steel is mainly influenced by dislocation strengthening in the matrix, solid solution strengthening of carbon and alloying elements and precipitation strengthening of carbides. The tensile strength and plasticity are the best after tempering at 650 ℃, which is mainly due to the comprehensive effect of Fe3Mo3C dissolution leading to solid solution strengthening of the matrix and precipitation strengthening of VC and Mo2C.

(3) When the tempering temperature increases from 450 ℃ to 700 ℃, the tensile fracture properties of Cr–Ni–Mo–V rotor steel gradually change from cleavage fracture to pitting fracture, which is mainly affected by the dissolution, precipitation and growth of Fe3Mo3C, VC and Mo2C in the structure.

Author Contributions

All authors have made contributions and agree with the above views. Chao Zhao: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing, Reviewing. Xinyi Zhang: Methodology; Xiaojie Liang and Guowang Song: Project administration. Bin Wang and Liqiang Guo: Investigation. Pengjun Zhang and Shuguang Zhang: Supervision.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Shanxi Province (CN) (Nos. 202203021222065), Shanxi Province Key Research and Development Program Project (CN) (Nos. 2022ZDYF039), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 52405435).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. Data will be made available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that no conflict of interest.

References

- Peng, Y.; Liu, C.; Yang, L.; Hou, S.; Cheng, R.; Zhang, H.; Ni, H. Improving cleanliness of 30Cr2Ni4MoV low-pressure rotor steel by CaO–SiO2–MgO–Al2O3 slag refining. J Iron Steel Res Int 2022, 29, 1434–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Zhao, J.; Yang, Z.; Jin, Y.; Zhang, C. Microstructure prediction of multi-directional forging for 30Cr2Ni4MoV steel by the secondary development of Deform software and BP neural network. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2022, 119, 2971–2984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, M.; Zhang, P.; Zhu, Y.; Li, S. Experiment research on the transformation plasticity by tensile/compressive stress and transformation kinetics during the martensitic transformation of 30Cr2Ni4MoV steel. Mater Res Express 2019, 6, 1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Wang, Q.; Li, Z. Microstructural evolution of high-nickel steel during quenching, lamellarizing, and tempering heat treatment. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2024, 33, 8618–8630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, T.Y.; Li, W.; Wang, N.M.; Wang, W.; Yang, K. Microstructural evolution during tempering and intrinsic strengthening mechanisms in a low carbon martensitic stainless bearing steel. Materials Science and Engineering: A 2022, 836, 142736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.F.; Zheng, D.Y.; Yang, X.F.; Wang, S.Y.; An, M.; Yan, G.B.; Xia, Y.Z.; Xing, F. Effect of carbide precipitation behavior at high temperatures on microstructure and mechanical properties of M50 steel. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2022, 18, 1155–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Cheng, X.; Wei, J.; Luo, R. Characterization of Carbide Precipitation during Tempering for Quenched Dievar Steel. Materials 2022, 15, 6448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Fan, J.; Wang, R.; Yu, Z.; Kang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Tuo, L.; Eckert, J.; Yan, Z. Microstructural evolution during tempering process and mechanical properties of Cr–Ni–Mo–V/Nb high strength steel. J Iron Steel Res Int 2024. [CrossRef]

- DelRio, F.W.; Martin, M.L.; Santoyo, R.L.; Lucon, E. Effect of Tempering on the Ductile-to-Brittle Transitional Behavior of Ni-Cr-Mo Low-Alloy Steel. Exp Mech 2020, 60, 1167–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Liu, Q.; Cai, Z.; Sun, Q.; Huo, X.; Fan, M.; He, Y.; Li, K.; Pan, J. Effect of tempering heat treatment on the microstructure and impact toughness of a Ni–Cr–Mo–V steel weld metal. Materials Science and Engineering: A 2022, 850, 143521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera-Villatoro, E.F.; Vázquez-Gómez, O.; Vergara-Hernández, H.J.; Gallegos-Pérez, A.I.; López-Martínez, E.; Díaz-Villaseñor, P.G.; Garnica-González, P. Non-isothermal tempering kinetics in a Cr–Mo–V medium-carbon low-alloy steel: a modeling proposal. J Therm Anal Calorim 2023, 148, 13791–13802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Wang, D.; Pang, Q.; Li, W.; Du, L. Effect of quenching-super intercritical quenching-tempering process on the evolution of microstructure and the yield ratio of Ni–Cr–Mo steel. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2024, 32, 915–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhao, X.; Qi, J.; Zhu, W.; Feng, Y.; Chen, L.; Wang, G. Effect of tempering on the microstructure and properties of a new multi-functional 460 MPa Grade construction structural steel. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2022, 18, 1092–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yu, W.; Tang, D.; Li, Y.; Lv, D.; Shi, J.; Du, Q.; Mei, D.; Fan, J. Effect of direct quenched and tempering temperature on the mechanical properties and microstructure of high strength steel. Mater Res Express 2020, 7, 126509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, H.; Wang, Q.; Liang, Z.; Gao, S.; Sun, L.; Gao, X.; Yang, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, F. Effect of rapid tempering at high temperature on microstructure, mechanical properties and stability of retained austenite of medium carbon ultrafine bainitic steel. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2024, 28, 3144–3154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Han, S.; Yang, C.; Geng, R.; Yuan, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, C. Evolution of Microstructures and Mechanical Properties with Tempering Temperature in a Novel Synergistic Precipitation Strengthening Ultra-High Strength Steel. Materials 2024, 17, 5314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.; Hu, C.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, H.; Wei, X.; Dong, H. Carbide transformation behaviors of a Cr-Mo-V secondary hardening steel during over-ageing. Mater Res Express 2020, 7, 36511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravikanth, K.V.; Verma, A.; Singh, J.B.; Vishwanadh, B.; Rai, S.K.; Karri, M. Effect of prior microstructure on carbide precipitation in a Cr-Mo-V pressure vessel steel at 650 °C. J Nucl Mater 2024, 602, 155359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claesson, E.; Magnusson, H.; Hedström, P. Scanning precession electron diffraction study of carbide precipitation sequence in low alloy martensitic Cr-Mo-V tool steel. Mater Charact 2023, 202, 113032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Q.; Kou, Z.; Wu, J.; Hou, T.; Xu, P. Effect of Tempering Temperature on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of 35CrMo Steel. Metals-Basel 2023, 13, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Fu, B.; Tang, Y.; Kong, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, N. Microstructure and mechanical properties of 9Cr18Mo martensitic stainless steel fabricated by strengthening-toughening treatment. Materials Science and Engineering: A 2023, 869, 144783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Yang, J.; Li, X.; Sun, M.; Ren, Y.; Li, M.; Yang, H.; Wang, H. A heat-resistant steel with excellent high-temperature strength-ductility based on a combination of solid-solution strengthening and precipitation hardening. Materials Science and Engineering: A 2024, 915, 147218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, W.; Ning, A.; Guo, H. Nanoscale precipitates and comprehensive strengthening mechanism in AISI H13 steel. International Journal of Minerals, Metallurgy, and Materials 2016, 23, 1056–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Luo, K.; Wang, J.; Lu, J. Carbide-facilitated nanocrystallization of martensitic laths and carbide deformation in AISI 420 stainless steel during laser shock peening. Int J Plasticity 2022, 150, 103191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Xiao, L.; Sui, Y.; Sun, W.; Chen, X.; Zhou, H. Achieving ultrahigh strength by tuning the hierarchical structure of low-carbon martensitic steel. Materials Science and Engineering: A 2023, 881, 145370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Cao, Y.; Chen, J.; Ye, H.; Zhao, C.; Huang, J. Microstructure Stabilities of Newly Developed Hot-Working Die Steel and H13 Steel at Elevated Temperature. Steel Res Int 2023, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Zhang, J.; Fu, J.; Lian, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Huang, J. Low-Cycle Fatigue Behavior of the Novel Steel and 30SiMn2MoV Steel at 700 °C. Materials 2020, 13, 5753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Song, K.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, G. Microstructure evolution and fracture mechanism of H13 steel during high temperature tensile deformation. Materials Science and Engineering: A 2019, 746, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Feng, H.; Li, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, H.; Jiang, Z. Effect of isothermal tempering time and temperature on microstructure and hardness of 3Cr5Mo2SiVN hot-work die steel. Mater Charact 2024, 212, 114010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meshkabadi, R.; Pouyafar, V.; Soltanikia, R. Investigation on Microstructure, Hardness and Fracture Energy of AISI H13 Hot Work Tool Steel by Cyclic Heat Treatment. J Mater Eng Perform 2024, 33, 6620–6629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).