1. Introduction

The current globalization and energetical situation have caused the need of adapting to global business practices and looking for alternatives to fabricate high added value products to sustain competitiveness in the industrial sector. Hence, the development of new manufacturing processes with less energy and raw material consumption achieving lighter structural components with better mechanical characteristics has become a real necessity.

In this way, the application of steels that combine high mechanical characteristics with good weldability and toughness characteristics has become a solution for material saving, enhancing the possibilities of components lightweighting. In this field, low alloyed Mn-Cr-Ni martensitic resistant steels show a good opportunity due to the fact that the martensitic microstructure leads to high mechanical characteristics combined with a good weldability due to the low alloying and carbon content and good toughness related with Ni additions. However, the main drawback of these steels is that they are susceptible to temper embrittlement (TE), which is one of the main causes of the brittle fractures observed in components in service, hindering their wide application in the industrial sector.

Initially, the TE was mainly related to the segregation of impurities (P, Sb, As, Sn) at the prior austenitic grain boundaries during tempering through a critical temperature range between 350-550 ºC [

1,

2]. Moreover, these studies investigate the effect of carbide-forming elements (Cr, Mn, Mo) on the TE by stating that when they were added to steel, the content of the impurities (mainly phosphorus) on the grain boundaries changes. However, this was not always confirmed, in fact, it was shown that an addition of Mo reduces the susceptibility to TE with unchanged phosphorus concentration on the grain boundaries, and increased content of Cr, Mn and Ni did not cause the phosphorus content on the grain boundaries to increase[

3,

4].

More recent studies have investigated the relationship of the TE with the phosphorous segregation at grain boundaries for different steel applications. Several works have studied this phenomenon for reactor pressure vessels steels (RPV) [

5,

6,

7]. Park et al [

6] attributed the TE of Ni-Mo-Cr high strength low alloy RPV steels to the grain boundary segregation of phosphorous and nickel. Nevertheless, same contents of these elements shown different TE behavior in studied steels after a tempering at 450 ºC for 2000 h which they think that could be related to the Mn contents. They stablished that the behavior of TE is not largely affected by the formation of M(3)P phosphide or the coarsening of chromium carbides in these steels. Additionally, the influence of the martensitic microstructure in the phosphorous segregation of Ni–Cr–Mo low alloy steel was studied by changing the cooling rate after austenitization [

5], determining that the increased volume fraction of martensite reduces the resistance to TE, showing an increased ductile-brittle transition-temperature and increasing the phosphorous segregation at prior austenite boundaries. Moreover, Guo et al [

7] studied the TE on an advanced SA508-4N Ni–Cr–Mo RPV steel using samples doped with phosphorous quenched from 890 to 1100 °C to obtain different prior austenite grain sizes and then tempered at 650 °C, followed by ageing at different lower temperatures to achieve different phosphorous segregation levels at prior austenite grain boundaries. They stablished that the ductile-brittle transition temperature of the steel augments linearly with increasing phosphorous grain boundary segregation level. Moreover, Yang et al. [

8] determined the effect of silicon addition in the TE phenomenon for automotive Quenching and Partitioning (Q+P) steels determining that the silicon addition increases the ductility of these steels inhibiting the precipitation of carbides during the tempering at 550 °C, but promotes the degree of phosphorus segregation at grain boundaries reducing the impact toughness. Dong et al. [

9] determined that increased P content of 0.02% caused little TE by segregation during thermal treatments of Dual-Phase steels. Zhao et al. [

10] analyzed the combined effect of phosphorous segregation, yield strength and grain size on the embrittlement of a Cr-Mo low alloy steel, concluding that the phosphorus boundary segregation and yield strength are directly correlated to the fracture appearance transition temperature of the steel but the prior austenite grain size is not directly linked to this temperature although it influences phosphorus boundary segregation and yield strength. Furthermore, the TE of martensitic stainless steels which are widely used in steam turbine blades has been also studied. While some authors related the TE to segregation of impurities in the prior austenite grain boundaries (mainly for tempering temperatures between 400-550 ºC), others attribute it to precipitation of the carbides during tempering [

11,

12,

13]. This relationship with carbides precipitation in grain boundaries during tempering at 400ºC of the TE, mainly of the Fe3C carbide, was also determined by Tavares et al. [

14] for a 9 %Ni low carbon steel. Min et al. [

15] suggest that intergranular fracture of a low-carbon steel at intermediate temperature occurs by formation of cementite forms at prior austenite grain boundaries, that active segregation of P at the cementite-matrix interface and microcracks start in this interface. Then, S segregates at the resulting free surfaces and thereby nucleates formation of microcracks, which grow and coalesce until a sufficient number of them link, then fracture occurs.

The effect of tempering conditions in the TE has been also widely studied. Mishnev et al. [

16] examined the effect of tempering after water quenching on the strength and fracture toughness of two ultra-high strength steels with chemical compositions of 0.34 %C-1.77 %Si -1.35 %Mn-0.56 %Cr-0.2 %Mo-0.04 %Nb-0.03 %Ti-0.002 %B and 0.44 %C-1.81 %Si-1.33 %Mn-0.82 %Cr-0.28 %Mo and observed TE at 400 ºC as decreased values of the Charpy V-notch impact energy, associating it to an increment of the grain size for fracture.

Dudko et al. [

17] studied the tempering behaviour of a low alloy high strength steel by tempering the specimens during 1 h at temperatures of 200 ºC, 280 ºC, 400 ºC, 500 ºC, 600 ºC and 650 ºC after an austenization at 900 ºC during 40 min followed by water quenching. They determined that the increase of tempering from 500 ºC to 650 ºC leads to a gradual increase of toughness from 20 to 33 J/cm

2. Moreover, they noticed that molybdenum suppresses the TE of the steel. Jialong et al. [

18] also observed this effect with the molybdenum addition in a martensitic stainless steel.

Euser et al. [

19] established that the rapid tempering reduced the TE in the medium carbon high strength 4340 (low silicon) steel due to the suppression of retained austenite decomposition but TE was maintained at different tempering rates for 300-M (high silicon) steel. Fort that, they studied the impact toughness values in the steels after rapid (1, 10, or 100 s) and conventional (3600 s) tempering. Judge et al. [

20] stablished that this short-time tempering at high temperatures (500 to 700 °C) improves the impact toughness via carbide (cementite) refinement. However, Wei et al. [

21] indicate that short tempering can result in Mn segregation at lath boundaries leading to the embrittlement of a high strength steel and observed that with the extension of tempering time, the segregation of Mo at the lath boundary can balance the negative effects of Mn segregation and recover the high toughness.

Despite the influence of the tempering temperatures and times in the TE phenomena has been widely studied in several works, the cooling rate after the high temperature tempering has not been studied as an influence factor in the TE mechanism. In this paper this influence in a low alloyed Mn-Cr-Ni martensitic resistant steel has been examined. This steel shows a good combination of mechanical, weldability and toughness characteristics which makes it suitable for fabrication of structural components and thus, very interesting from the industrial point of view. The aim of the study is to determinate if the TE is influenced by cooling rates after tempering and if certain cooling conditions can avoid the undesirable TE of the selected steel. The tempering temperature has been stablished at 650 ºC, in order to avoid tempering between 350-550 ºC related in previously described investigations with TE during the tempering treatment itself and due to the good combination of mechanical properties and toughness reached after tempering at 650 ºC shown in steels with similar chemical composition [

22] . For the investigation, Charpy impact tests and metallurgical analysis using emission Scanning Electron and Transmission Electron microscopes were carried out on specimens cooled in different cooling media after the tempering to find a relation between the cooling rates with the microstructures or grain boundary segregations and TE of this steel.

Moreover, the influence of the molybdenum addition in the effect of the TE suppression for this steel has been examined.

2. Material and Methodology

2.1. Material and Specimens

The material used for this study was a Mn-Cr-Ni low alloyed martensitic steel with the chemical composition specified in

Table 1. The mechanical properties of the selected steel after the quenching and tempering heat treatment are summarized in

Table 2. For the study six specimens of 60x70x60 mm obtained from the third radius of a hot rolled, quenched and tempered bar of 165 mm diameter were used.

2.2. Methodology

Specimens were subjected to two subsequent solubilization- quenching heat treatments in order to ensure the maximum homogeneity and to reproduce the usual solubilization treatment made in this steel after the welding and previous to the quenching and tempering.

The first cycle was performed at 940 ºC for 1 h and the second one at 880 ºC for 1 h, followed by water quenching in both cases. After, specimens were tempered at 650 ºC for 1h and cooled at different rates. The cooling media employed are specified in

Table 3.

All the heat treatments were performed in a muffle furnace Carbolite CSF 1200.

Then, Charpy impact test were performed following ASTM E23 standard. Specimens of 55 × 10 × 10 mm3 with a 45 ° V notch at the center were tested at -20 ºC temperature. Three tests per each cooling rate were performed and the average was considered as the impact toughness value.

Hardness tests were carried out in Charpy specimens using a Vickers Future Tech- FM 700 tester and 1 kg load according to ASTM E92 standard and the average of three hardness readings was reported as the hardness value.

The microstructure change with the tempering cooling rate was examined under Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM JEOL JSM T 330 microscope) and the Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM, Philips CM 200). For the analysis in the Transmission Electron Microscope, extraction replicas needed to be prepared. For that, after Beaujard etching of the polished specimens, a vacuum metallization of the samples was carried out in a Baltec, MED 004 equipment and a subsequent etching using Nital was carried out into the deposited carbon film. The extracted films were then rinsed with distilled water and samples thus prepared were collected over copper grid. The chemistry of the carbides was determined by Energy Dispersive X-Ray Spectra (EDS) using an Oxford Link Analytical sonde.

3. Results and Discussion

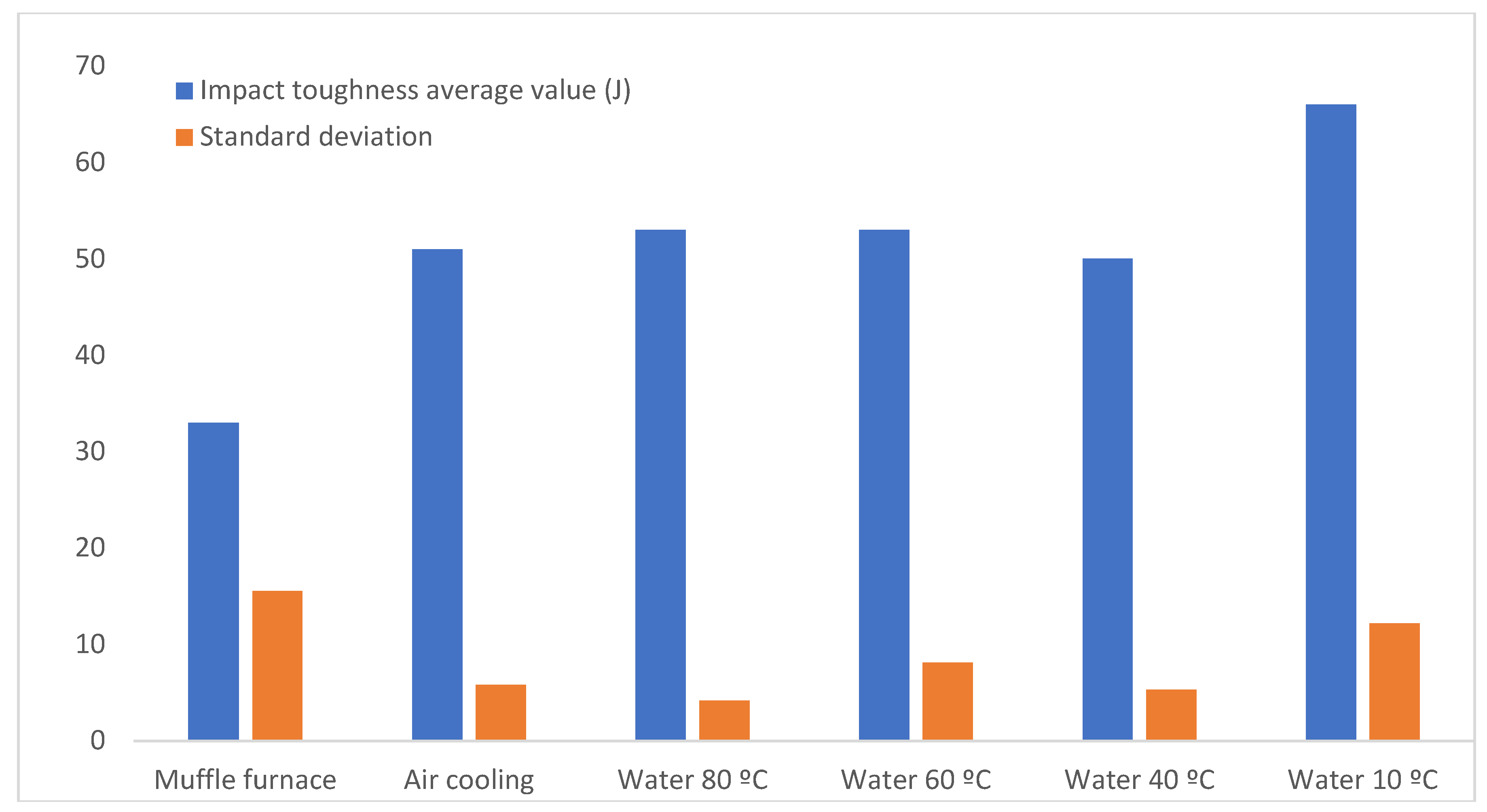

The variation of the impact toughness values with the tempering cooling media are shown in Figure 1. It can be seen that the fastest cooling rate after the tempering (specimens cooled in water at 10 ºC) leads to the highest toughness, whereas the slowest cooling rate (specimens cooled in the muffle furnace) shows the lowest toughness. Intermediate cooling rates show similar impact toughness values.

Figure 2.

Variation in the impact toughness with tempering cooling media.

Figure 2.

Variation in the impact toughness with tempering cooling media.

Hardness results are shown in

Table 4. No significant hardness differences can be noticed between the specimens cooled at different cooling rates. This can be justified because all specimens have been summitted to same quenching and tempering temperature and time conditions, which leads to similar ultimate strength and hardness after quenching and tempering treatment despite the different cooling rates after high temperature tempering. However, toughness results indicate that for same quenching and tempering conditions, the influence of the cooling rate after the high temperature tempering is significant in impact toughness values.

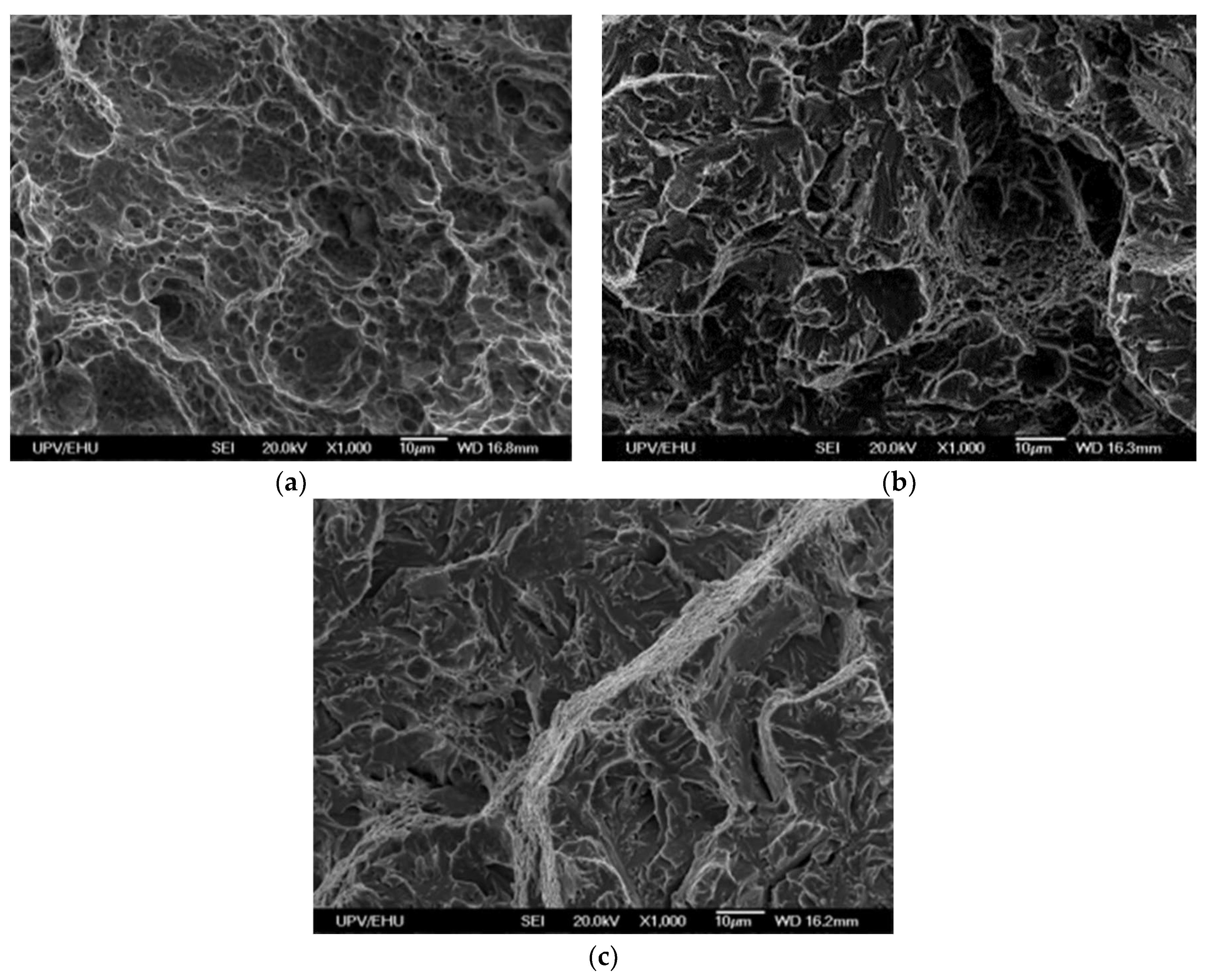

In order to have an explanation of the difference in impact toughness values observed in Figure 1 the specimens with lowest and highest toughness impact values were chosen for the fractography study shown in

Figure 2a,

Figure 2b and

Figure 2c.

The specimen cooled at water at 10 ºC after tempering (fastest cooling), shows a fibrous fracture with presence of voids/dimples indicating ductile mode of failure. However, for the specimen cooled in the muffle furnace (slowest cooling), the fracture mode shows a pseudo-cleavage mode of fracture, showing brittle zones and grain boundary embrittlement or intergranular fracture. This observation is in agreement with minimum impact toughness observed for the specimens cooled in this cooling rate condition.

These specimens were also selected for detailed metallographic investigations to identify main differences between them and determine the possible reasons for the observed embrittlement in the specimen cooled in the muffle furnace (slowest cooling rate) for this steel.

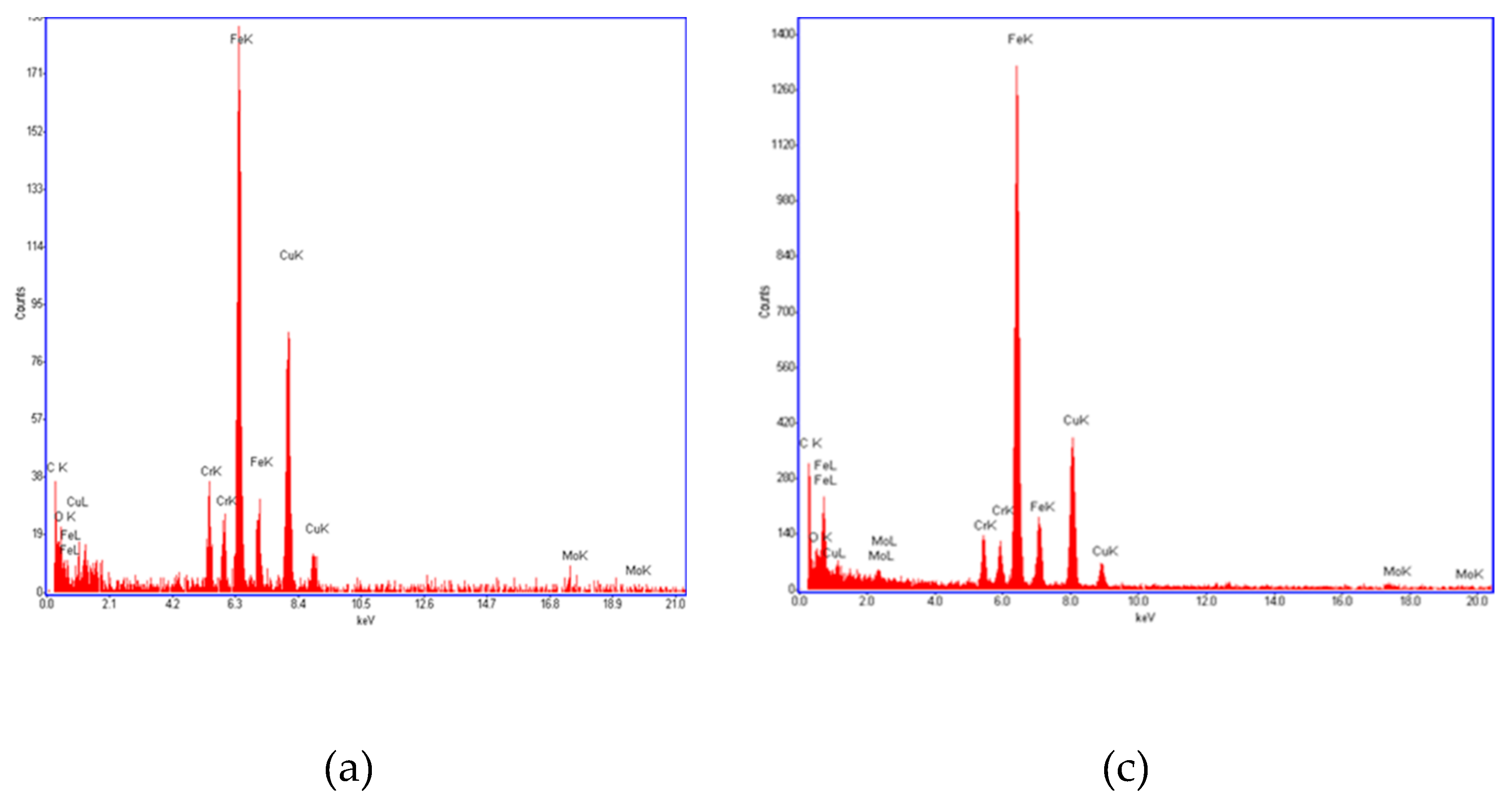

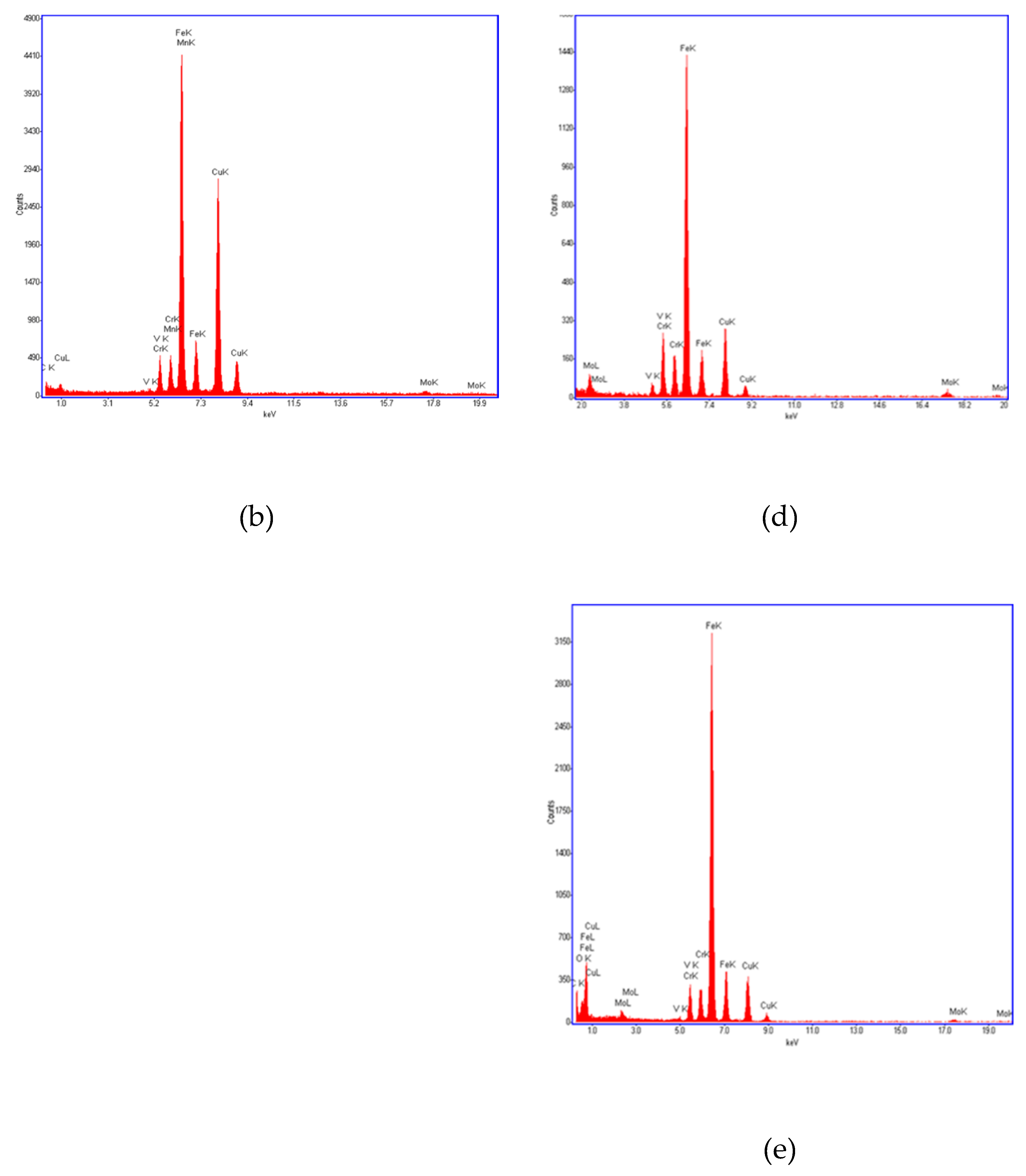

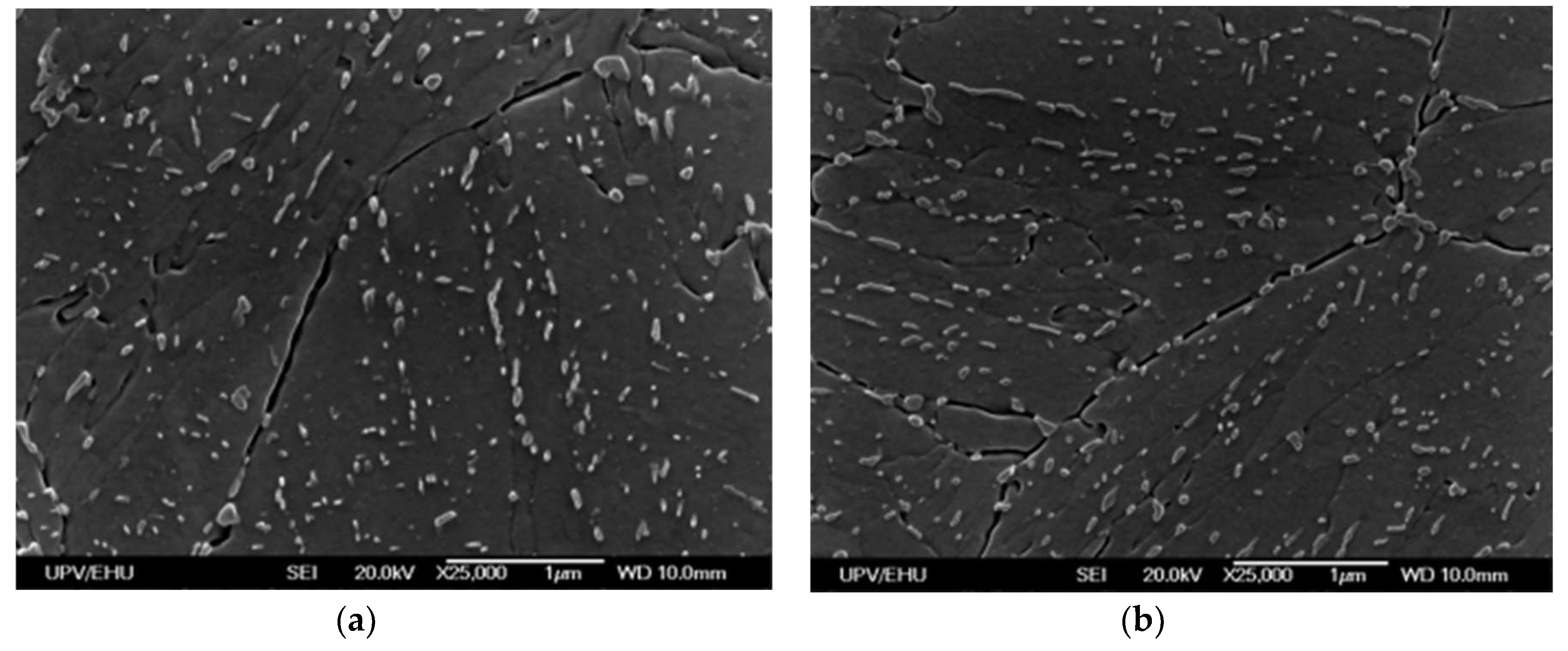

Figure 3a and

Figure 3b show the microstructural analysis in SEM microscope for each case.

Samples are composed by tempered martensite with presence of bainite. In both samples mainly elongated with some globular carbides precipitation generated during the tempering can be distinguished inside the prior austenite grains where the martensite laths have been formed [

23,

24,

25]. However, in the sample with lowest impact toughness value, these carbides appear also along the prior austenite grain boundaries. This is the main cause of the grain boundaries weakness appreciated during the fractography analysis and it is related with the diffusion phenomena that tempering carbides can suffer in temperature ranges between 450-550 ºC during the slow cooling after the tempering, allowing their location in prior austenite grain boundaries and not only inside the prior austenite grain as happens for high cooling rates.

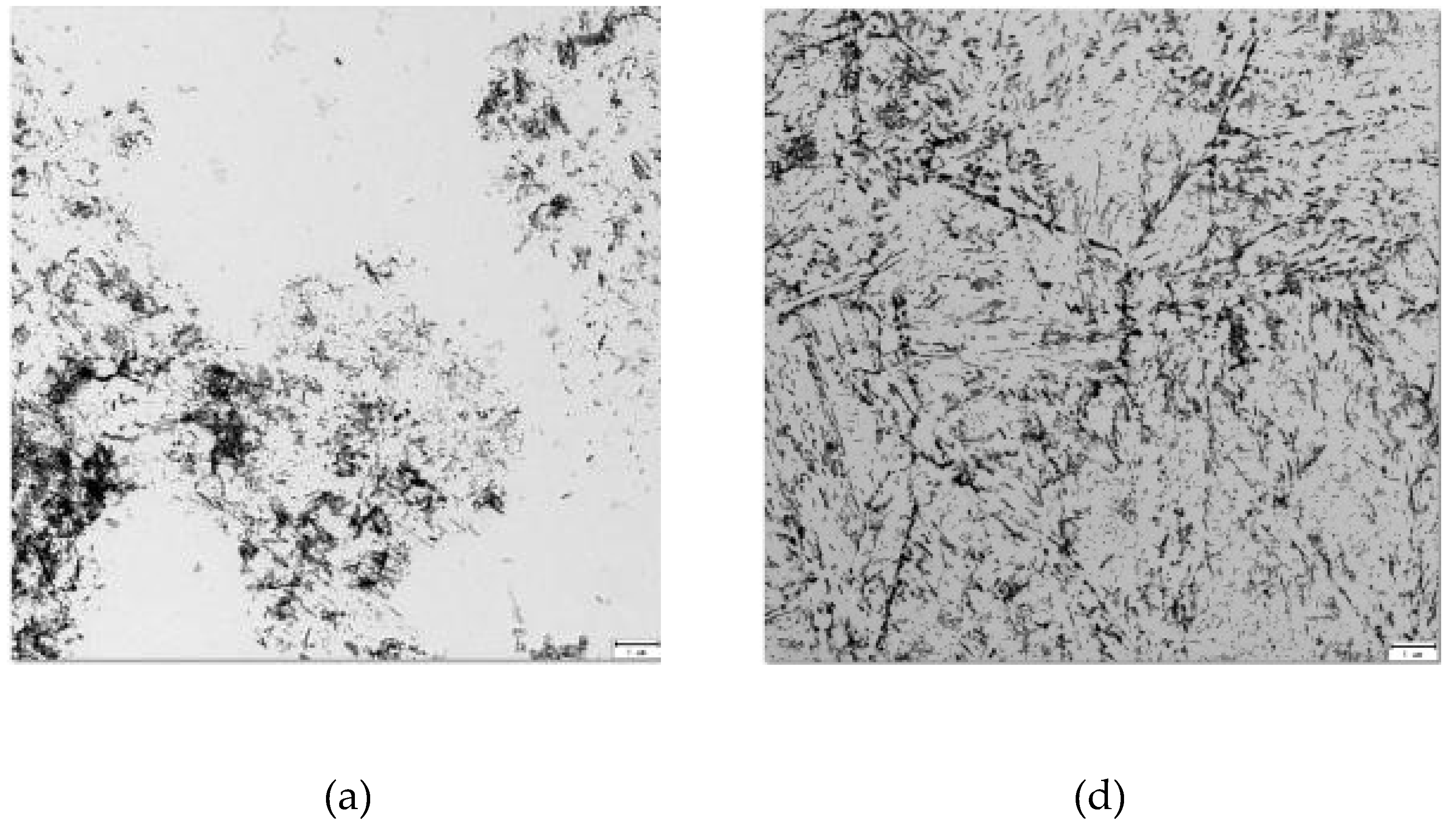

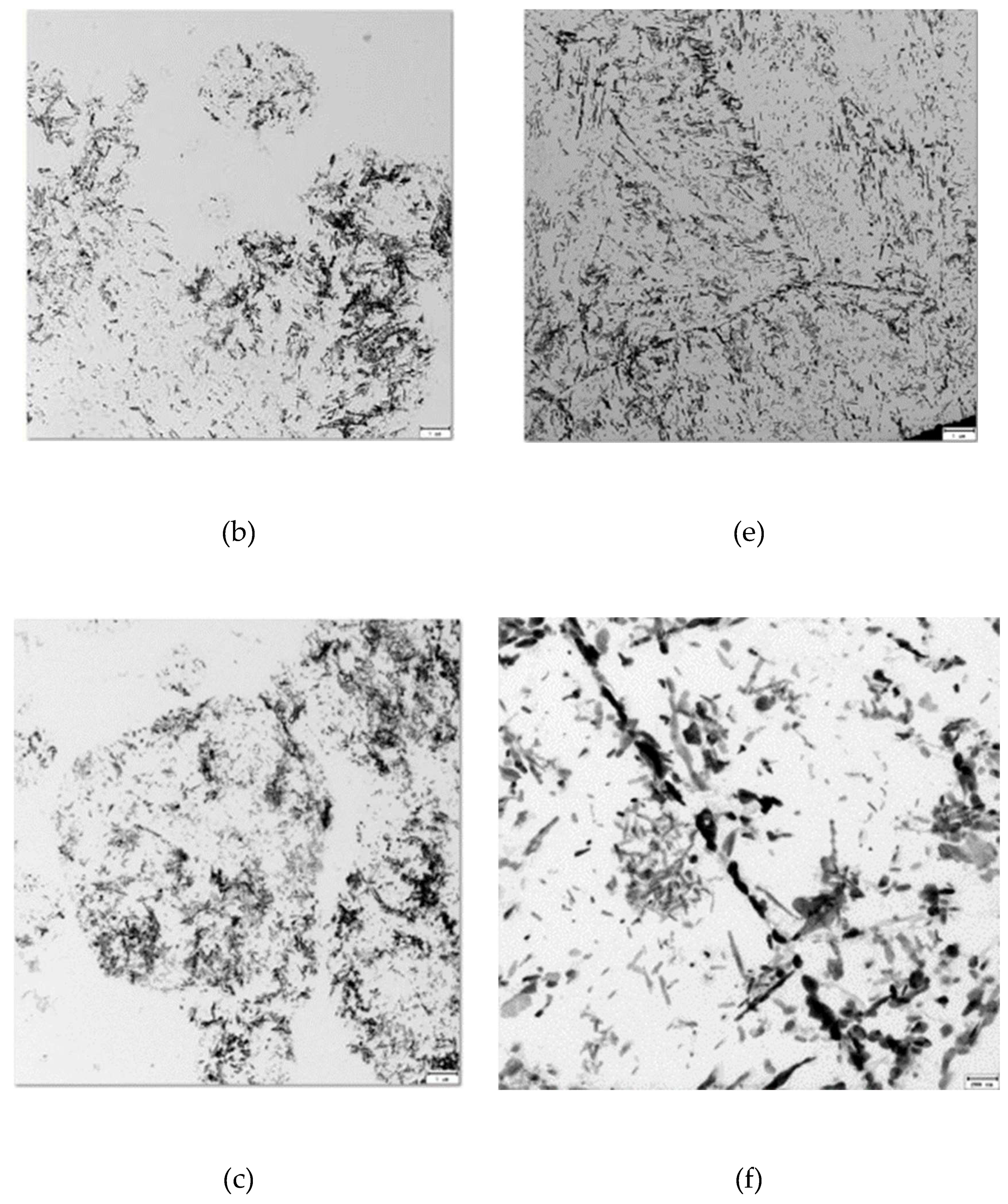

Figure 4a,

Figure 4b,

Figure 4c,

Figure 4d,

Figure 4e and

Figure 4f show the study in the TEM microscope of the prepared extraction replicas from each specimen. It can be seen that for the specimen with high cooling rate after tempering, images (a) (b) and (c), the carbides are located mainly inside prior austenite grains, while for the specimen with slowest cooling rate the carbides are located also at grain boundaries, as it is shown in images (d) (e) and (f).

A TEM- EDS spectra of the carbides seen inside the prior austenite grains and along the grain boundaries was carried out. In both cases mainly iron, chromium, molybdenum and vanadium carbides were found, being the cementite the carbide found in most proportion [

26,

27]. No significant chemical differences between carbides located inside or at grain boundaries of prior austenite grains have been seen. Neither differences can be noticed between carbides of each specimen as it can be appreciated in spectra shown in

Figure 5a,

Figure 5b,

Figure 5c,

Figure 5d,

Figure 5e.

Moreover, despite the segregation of impurities (P, Sb, As..) along the prior austenite grain boundaries, specially surrounding Fe3C carbides, is associated to the TE of different steels [

28,

29,

30] no evidence of such segregation is observed in the steel of the present study.

Finally, it has been noticed that the addition of molybdenum in 0.65 % has not actuated as TE inhibitor in case of slow post tempering cooling rates in this steel.

Figure 6.

TEM- EDS spectra of carbides obtained from specimens cooled at different cooling rates conditions after tempering: (a) (b) carbides inside the prior austenite grains in specimen cooled in water at 10 ºC (c) carbides inside the prior austenite grains in specimen cooled in the muffle furnace, (d) (e) carbides in prior austenite grain boundaries in specimen cooled in the muffle furnace.

Figure 6.

TEM- EDS spectra of carbides obtained from specimens cooled at different cooling rates conditions after tempering: (a) (b) carbides inside the prior austenite grains in specimen cooled in water at 10 ºC (c) carbides inside the prior austenite grains in specimen cooled in the muffle furnace, (d) (e) carbides in prior austenite grain boundaries in specimen cooled in the muffle furnace.

4. Conclusions

In this work the influence of the cooling rate after high temperature tempering in the TE of a low alloyed Mn-Cr-Ni martensitic resistant steel was studied. Results of the investigation determinate the high influence of the cooling rate after the high temperature tempering in the TE phenomena of the selected steel:

The impact toughness is higher after post tempering water cooling compared to air or muffle furnace cooling.

The specimen cooled at water at 10 ºC after tempering (fastest cooling), shows a fibrous fracture with presence of voids/dimples while the specimen cooled in the muffle furnace (slowest cooling) shows a pseudo-cleavage mode of fracture, showing brittle zones and grain boundary embrittlement or intergranular fracture.

High cooling rates after the tempering prevent the carbides positioning in the prior austenite grain boundaries which deal to better combination of toughness and mechanical properties of the specimens.

Slow cooling rates contribute to the formation of carbides along the prior austenite grain boundaries, which is the main cause of the grain boundaries weakness appreciated during the fractography analysis and the TE mechanism.

Mainly iron, chromium, molybdenum and vanadium carbides were found at prior austenite grain boundaries. No significant chemical differences between carbides located inside or in the grain boundaries of prior austenite grains have been found.

The addition of molybdenum in 0.65% does not eliminate the TE phenomena in this steel for cases where the cooling rate is too slow.

So, this study shows a way to avoid TE phenomena of low alloyed Mn-Cr-Ni martensitic resistant steels after a high temperature tempering in order to obtain a good combination of mechanical and toughness characteristics. Being the TE one of the main drawbacks shown in service by these steels, the realized analysis allows the expansion of these kind of steels, especially interesting from an industrial point of view.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Olatz Bilbao and Franck Girot; Methodology, Olatz Bilbao and Franck Girot; Validation, Franck Girot, Jone Muñoz and Amaia Torregaray; Formal analysis, Olatz Bilbao, Franck Girot and Jone Muñoz; Investigation, Olatz Bilbao; Data curation, Olatz Bilbao; Writing – original draft, Olatz Bilbao; Supervision, Franck Girot, Jone Muñoz and Amaia Torregaray.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article. Other data that has been used is confidential.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Olefjord, “Temper embrittlement,” International Metals Reviews, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 149–163, 1978. [CrossRef]

- M. Militzer and J. Wieting, “Segregation mechanisms of temper embrittlement,” Acta Metallurgica, vol. 37, no. 10, pp. 2585–2593, 1989. [CrossRef]

- C. J. McMahon, “The influence of Mo on P-lnduced temper embrittlement in Ni-Cr steel,” Metallurgical Transactions A, vol. 8, no. 7, pp. 1055–1057, 1977. [CrossRef]

- V. v. Zabil’skii, “ Temper embrittlement of structural alloy steels (review),” Metal Science and Heat Treatment, vol. 29, no. 1, pp. 32–42, 1987. [CrossRef]

- S. G. Park, K. H. Lee, M. C. Kim, and B. S. Lee, “Effects of boundary characteristics on resistance to temper embrittlement and segregation behavior of Ni–Cr–Mo low alloy steel,” Materials Science and Engineering: A, vol. 561, pp. 277–284, Jan. 2013. [CrossRef]

- S. G. Park, M. C. Kim, B. S. Lee, and D. M. Wee, “Evaluation of temper embrittlement effect and segregation behaviors on Ni-Mo-Cr high strength low alloy RPV steels with changing P and Mn contents,” Journal of Korean Institute of Metals and Materials, vol. 48, no. 2, pp. 122–132, Feb. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Y. Guo, M. Wang, K. Wang, and S. H. Song, “Relation of embrittlement to phosphorus grain-boundary segregation for an advanced Ni–Cr–Mo RPV steel,” Journal of Materials Research and Technology, vol. 18, pp. 2240–2249, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Yang, L. Wang, Z. Sun, J. Liu, S. Liu, and X. Jin, “Effect of silicon addition on phosphorus segregation at grain boundary and temper embrittlement of Fe-C-Mn-xSi steels,” Mater Lett, vol. 320, p. 132342, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. Dong et al., “The influence of phosphorus on the temper embrittlement and hydrogen embrittlement of some dual-phase steels,” Materials Science and Engineering: A, vol. 854, p. 143379, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhao and S. Song, “Combined Effect of Phosphorus Grain Boundary Segregation, Yield Strength, and Grain Size on Embrittlement of a Cr–Mo Low-Alloy Steel,” Steel Res Int, vol. 89, no. 8, Aug. 2018. [CrossRef]

- G. Yang, C. Wang, X. quan Liu, and Z. dong Liu, “Embrittlement Mechanism due to Slow Cooling During Quenching for M152 Martensitic Heat Resistant Steel,” Journal of Iron and Steel Research International, vol. 17, no. 6, pp. 60–66, Jun. 2010. [CrossRef]

- J. Li, C. Zhang, and Y. Liu, “Influence of carbides on the high-temperature tempered martensite embrittlement of martensitic heat-resistant steels,” Materials Science and Engineering: A, vol. 670, pp. 256–263, Jul. 2016. [CrossRef]

- G. Chakraborty et al., “Study on tempering behaviour of AISI 410 stainless steel,” Mater Charact, vol. 100, pp. 81–87, Feb. 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. S. M. Tavares, R. P. C. da Cunha, C. Barbosa, and J. L. M. Andia, “Temper embrittlement of 9%Ni low carbon steel,” Eng Fail Anal, vol. 96, pp. 538–542, 2019. [CrossRef]

- J.-H. Min et al., “Embrittlement mechanism in a low-carbon steel at intermediate temperature,” Mater Charact, vol. 149, pp. 34–40, 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. Mishnev, Y. Borisova, T. Kniaziuk, S. Gaidar, and R. Kaibyshev, “Quench and Tempered Embrittlement of Ultra-High-Strength Steels with Transition Carbides,” Metals (Basel), vol. 13, no. 8, 2023. [CrossRef]

- V. Dudko, D. Yuzbekova, S. Gaidar, S. Vetrova, and R. Kaibyshev, “Tempering Behavior of Novel Low-Alloy High-Strength Steel,” Metals (Basel), vol. 12, no. 12, 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Tian, K. Chen, H. Li, and Z. Jiang, “Suppressing grain boundary embrittlement via Mo-driven interphase precipitation mechanism in martensitic stainless steel,” Materials Science and Engineering: A, vol. 833, p. 142529, 2022. [CrossRef]

- V. K. Euser, D. L. Williamson, K. O. Findley, A. J. Clarke, and J. G. Speer, “The Role of Retained Austenite in Tempered Martensite Embrittlement of 4340 and 300-M Steels Investigated through Rapid Tempering,” Metals (Basel), vol. 11, no. 9, 2021. [CrossRef]

- V. K. Judge, J. G. Speer, K. D. Clarke, K. O. Findley, and A. J. Clarke, “Rapid Thermal Processing to Enhance Steel Toughness,” Sci Rep, vol. 8, no. 1, p. 445, 2018. [CrossRef]

- X. Wei, T. Gong, X. Cao, G. Zhao, and Z. Zhang, “Effects of Lath Boundary Segregation and Reversed Austenite on Toughness of a High-Strength Low-Carbon Steel,” Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A, vol. 55, no. 5, pp. 1484–1494, 2024. [CrossRef]

- V. Yadav, A. K. Singh, and G. Sahoo, “Effect of tempering temperature on microstructure and mechanical properties of low alloy high strength steel,” Journal of Metals, Materials and Minerals, vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 16–21, 2018.

- E. Claesson et al., “Carbide Precipitation during Processing of Two Low-Alloyed Martensitic Tool Steels with 0.11 and 0.17 V/Mo Ratios Studied by Neutron Scattering, Electron Microscopy and Atom Probe,” Metals (Basel), vol. 12, no. 5, 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. Tkachev et al., “Effect of quenching and tempering on structure and mechanical properties of a low-alloy 0.25C steel,” Materials Science and Engineering: A, vol. 868, p. 144757, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Teramoto et al., “Influence of Iron Carbide on Mechanical Properties in High Silicon-added Medium-carbon Martensitic Steels,” ISIJ International, vol. 60, no. 1, pp. 182–189, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Li, T. Jia, L. Ma, X. Zhao, and Z. Wang, “Investigation on Temper Embrittlement of TS1100 MPa Grade Ultra-High Strength Steel,” Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A, vol. 51, no. 10, pp. 5306–5317, 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Morsdorf, A. Kashiwar, C. Kübel, and C. C. Tasan, “Carbon segregation and cementite precipitation at grain boundaries in quenched and tempered lath martensite,” Materials Science and Engineering: A, vol. 862, p. 144369, 2023. [CrossRef]

- X. Wei, T. Gong, X. Cao, G. Zhao, and Z. Zhang, “Effects of Lath Boundary Segregation and Reversed Austenite on Toughness of a High-Strength Low-Carbon Steel,” Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A, vol. 55, no. 5, pp. 1484–1494, 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. Yang, T. Xu, H. Zhao, C. Hu, and H. Dong, “Regulation Law of Tempering Cooling Rate on Toughness of Medium-Carbon Medium-Alloy Steel,” Materials, vol. 17, no. 1, 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Schibler, C. D’Ambra, M. Roberts, M. V Manuel, T. W. Krause, and A. Saleem, “Temper embrittlement in HY-80 steel: Microstructure, magnetic and microhardness properties,” NDT & E International, vol. 132, p. 102728, 2022. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).