Submitted:

15 November 2023

Posted:

15 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental materials and procedure

3. Results

3.1. Microstructure characterization

3.2. Mechanical Property Characterization

4. Discussion

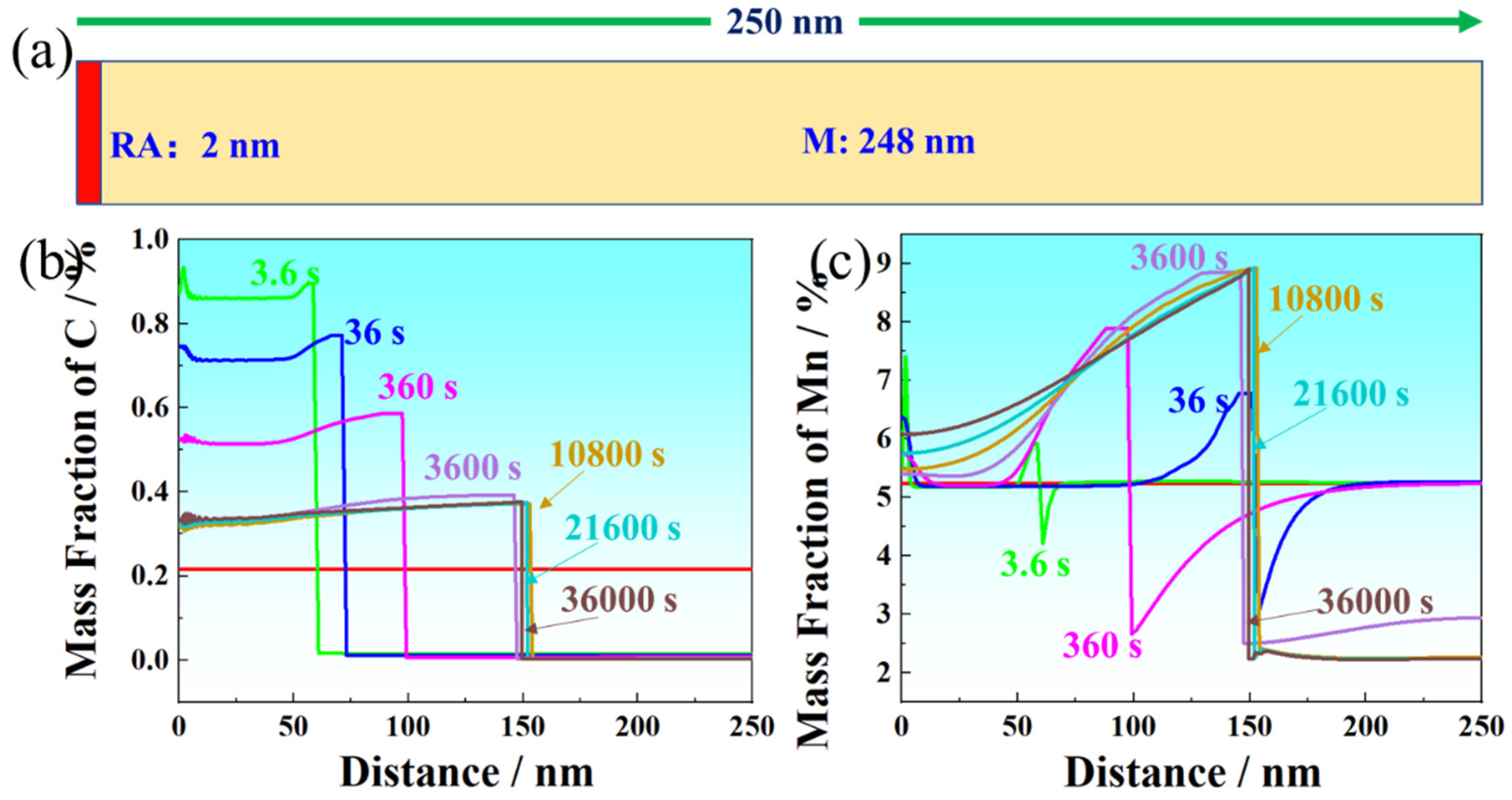

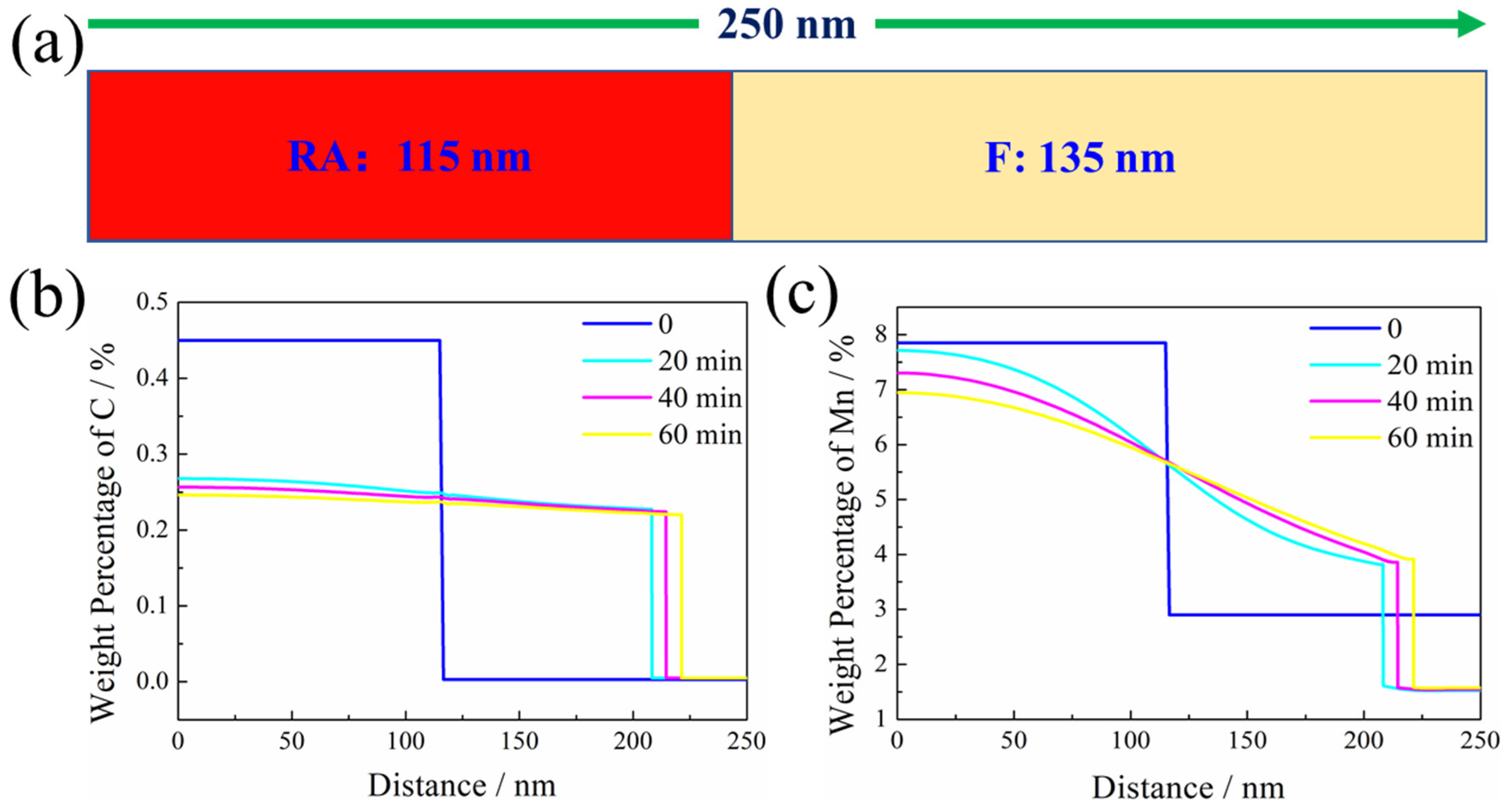

4.1. Phase transformation mechanism analysis

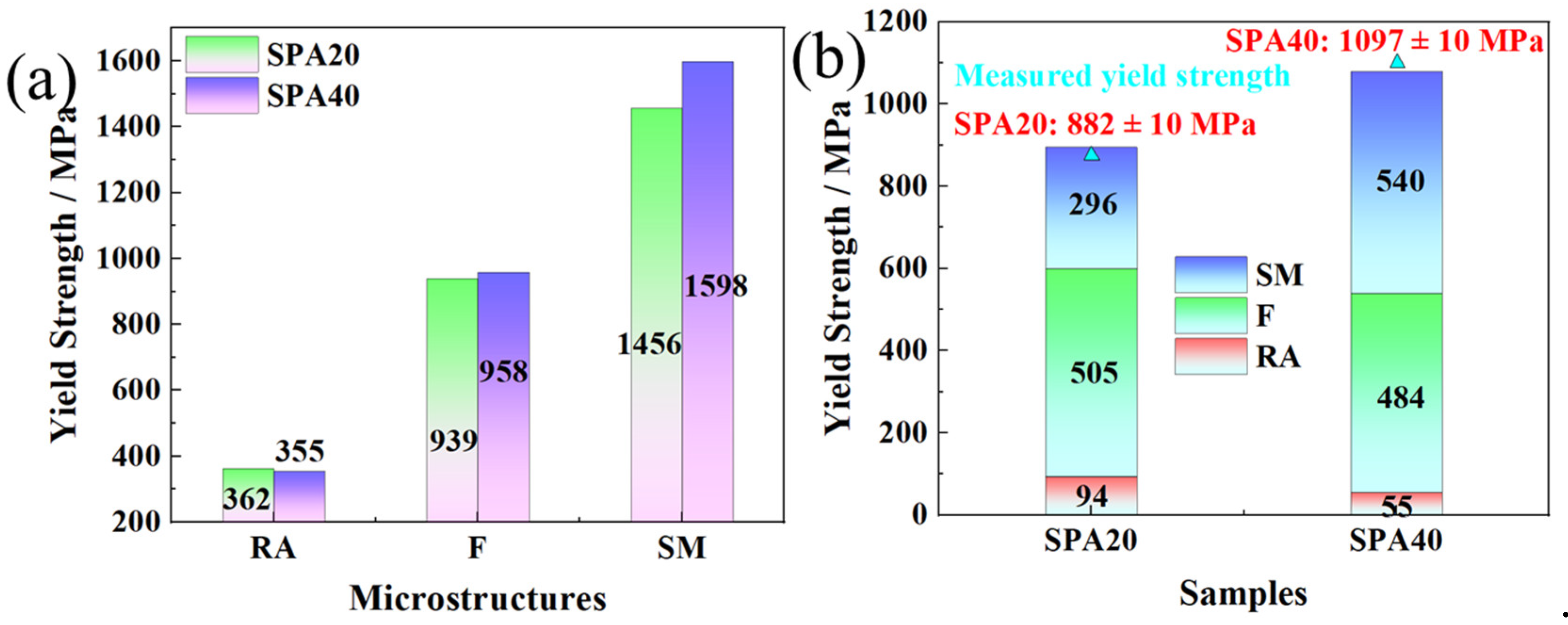

4.2. Strengthening contribution analysis

- (V, Mo)C precipitation strengthening

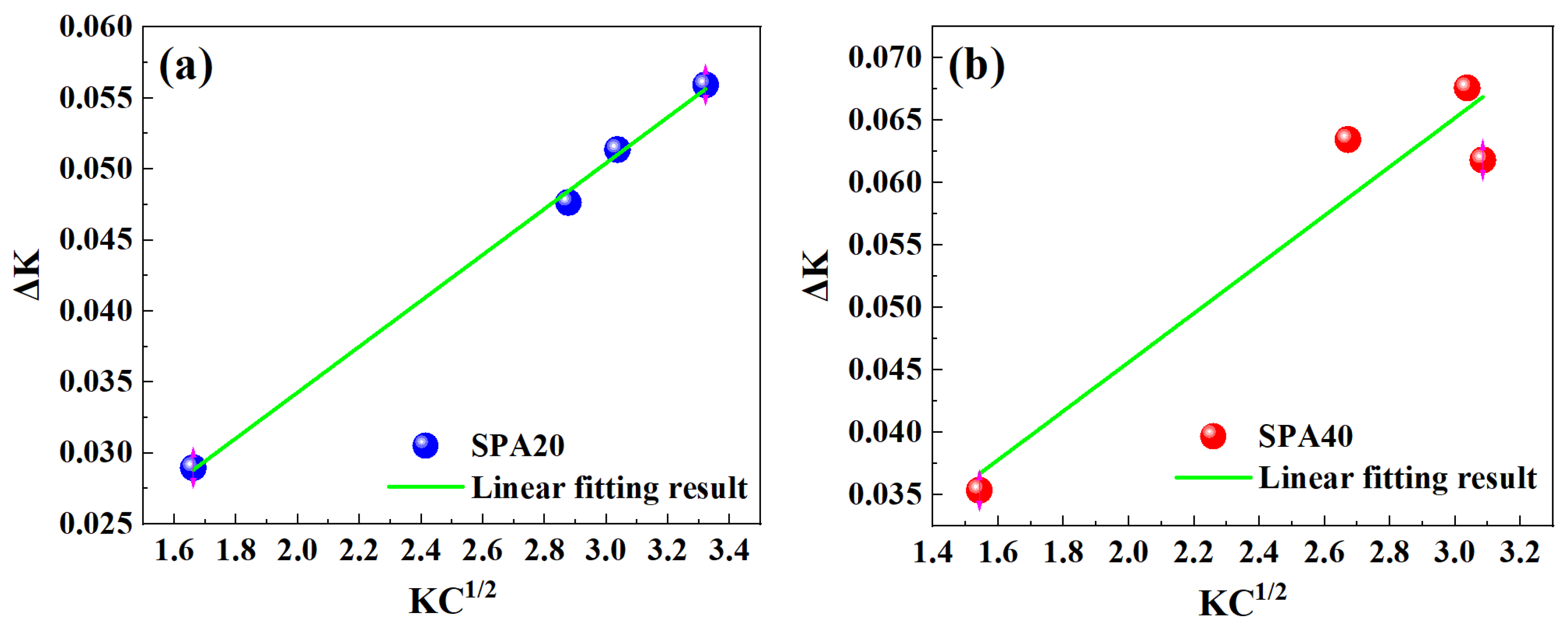

- Dislocation density and strengthening in ferrite and SM

- Yield strength of RA

- Yield strength of ferrite

- Yield strength of SM

- The calculated yield strength of the studied steel

5. Conclusions

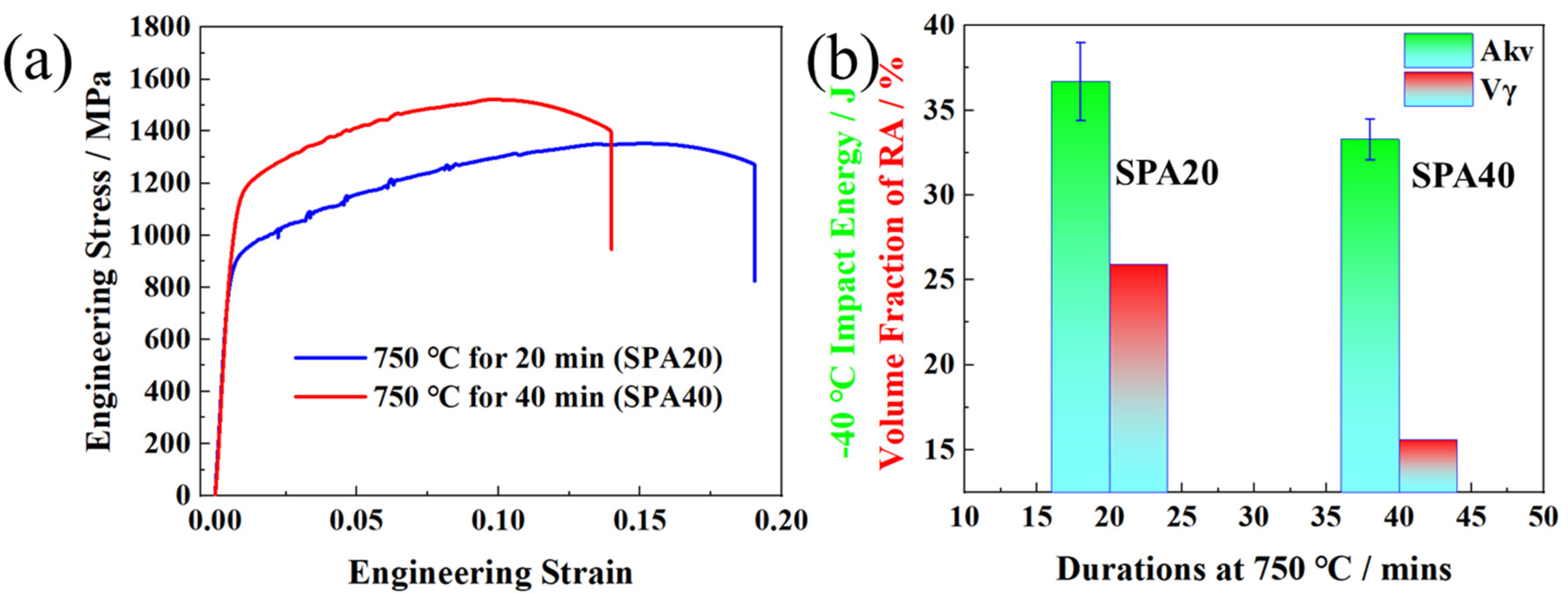

- The initial microstructure was a dual-phase structure containing ferrite and RA after intercritically tempered at 650 °C for 6 h, and the RA content was about 30%. Once subject to SPA process, the microstructure was consisted of ferrite, RA and SM and the content of them were 53.8%, 25.9% and 20.3 for SPA20, and 50.6%, 15.6% and 33.8% for SPA40.

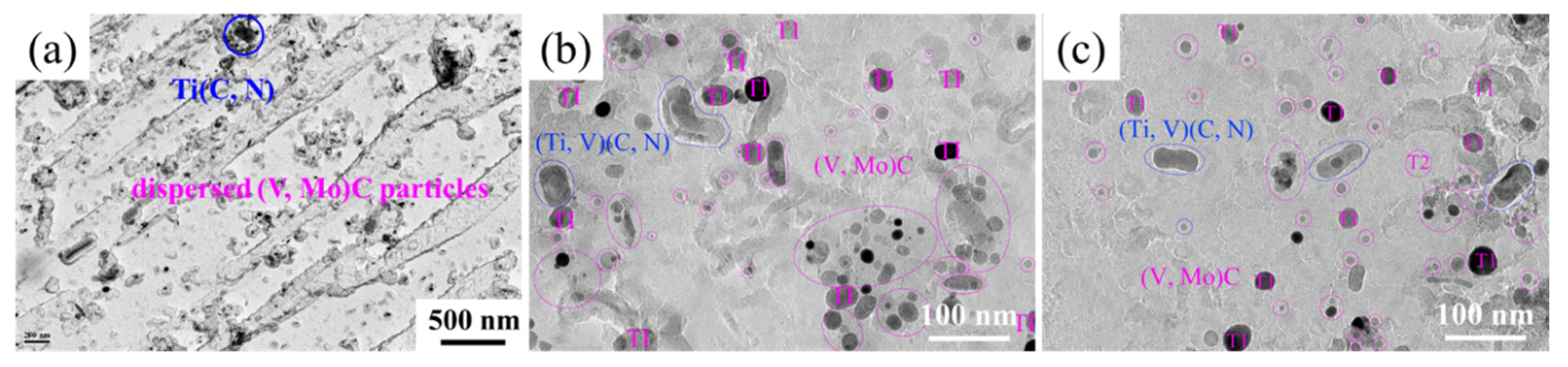

- The mean (V, Mo)C particle size was about 17.2 nm of IT650, while the mean particle size was about 18.0 nm of SPA process. The morphology of (V, Mo)C particle was disc-like, while it tended to be near-spherical morphology after subjected to the SPA process.

- The yield strength increased by about 215 MPa from SPA20 to SPA40 of 1097 MPa, while there was acceptable shrinkage in total elongation from 19.0% to 14.0 % and in -20 °C impact energy from 36.7 J to 33.3 J.

- Protected by SM, the stable RA displayed the positive effect on yield strength, while it showed little effect on ductility and toughness. The ultrafine-grain ferrite and SM, formed during SPA process, jointly strengthened above 1000 MPa for SPA40. The (V, Mo)C provided the precipitation strengthening increment about 108 MPa.

Acknowledgements

References

- B. He, B. Hu, H. Yen, G. Cheng, Z. Wang, H. Luo, M. Huang, High dislocation density–induced large ductility in deformed and partitioned steels, Science 357(6355) (2017) 1029-1032. [CrossRef]

- F. Yang, H. Luo, C. Hu, E. Pu, H. Dong, Effects of intercritical annealing process on microstructures and tensile properties of cold-rolled 7Mn steel, Materials Science and Engineering: A 685 (2017) 115-122. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang, M. Zhang, Q. Cen, W. Wang, X. Sun, A novel process combining thermal deformation and intercritical annealing to enhance mechanical properties and avoid Lüders strain of Fe-0.2 C–7Mn TRIP steel, Materials Science and Engineering: A 839 (2022) 142849. [CrossRef]

- Q. Guo, H.W. Yen, H. Luo, S.P. Ringer, On the mechanism of Mn partitioning during intercritical annealing in medium Mn steels, Acta Materialia 225 (2022) 117601. [CrossRef]

- G. Bansal, D. Madhukar, A. Chandan, K. Ashok, G. Mandal, V. Srivastava, On the intercritical annealing parameters and ensuing mechanical properties of low-carbon medium-Mn steel, Materials Science and Engineering: A 733 (2018) 246-256. [CrossRef]

- D. Zhang, G. Liu, K. Zhang, X. Sun, X. Liang, Q. Yong, Effect of Nb microalloying on microstructure evolution and mechanical properties in low carbon medium manganese steel, Materials Science and Engineering: A 824 (2021) 141813. [CrossRef]

- H. Luo, J. Shi, C. Wang, W. Cao, X. Sun, H. Dong, Experimental and numerical analysis on formation of stable austenite during the intercritical annealing of 5Mn steel, Acta Materialia 59(10) (2011) 4002-4014. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, L. Wang, K.O. Findley, J.G. Speer, Influence of temperature and grain size on austenite stability in medium manganese steels, Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A 48 (2017) 2140-2149. [CrossRef]

- M.I. Latypov, S. Shin, B.C. De Cooman, H.S. Kim, Micromechanical finite element analysis of strain partitioning in multiphase medium manganese TWIP+ TRIP steel, Acta Materialia 108 (2016) 219-228. [CrossRef]

- S. Sadeghpour, M.C. Somani, J. Kömi, L.P. Karjalainen, A new combinatorial processing route to achieve an ultrafine-grained, multiphase microstructure in a medium Mn steel, Journal of Materials Research and Technology 15 (2021) 3426-3446. [CrossRef]

- L. Liu, Q. Yu, Z. Wang, J. Ell, M. Huang, R.O. Ritchie, Making ultrastrong steel tough by grain-boundary delamination, Science 368(6497) (2020) 1347-1352. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhang, Y. Xu, D. Han, Z. Tong, Improving yield strength and elongation combination by tailoring austenite characteristics and deformation mechanism in medium Mn steel, Scripta Materialia 218 (2022) 114790. [CrossRef]

- J. Hu, L. Du, M. Zang, S. Yin, Y. Wang, X. Qi, X. Gao, R. Misra, On the determining role of acicular ferrite in VN microalloyed steel in increasing strength-toughness combination, Materials Characterization 118 (2016) 446-453. [CrossRef]

- Q. Zhou, L. Qian, J. Tan, J. Meng, F. Zhang, Inconsistent effects of mechanical stability of retained austenite on ductility and toughness of transformation-induced plasticity steels, Materials Science and Engineering: A 578 (2013) 370-376. [CrossRef]

- R. Ding, Z. Dai, M. Huang, Z. Yang, C. Zhang, H. Chen, Effect of pre-existed austenite on austenite reversion and mechanical behavior of an Fe-0.2 C-8Mn-2Al medium Mn steel, Acta Materialia 147 (2018) 59-69. [CrossRef]

- Y.G. Yang, Z.L. Mi, M. Xu, Q. Xiu, J. Li, H.T. Jiang, Impact of intercritical annealing temperature and strain state on mechanical stability of retained austenite in medium Mn steel, Materials Science and Engineering: A 725 (2018) 389-397. [CrossRef]

- G. Liu, B. Li, S. Xu, S. Tong, X. Wang, X. Liang, X. Sun, Effect of intercritical annealing temperature on multiphase microstructure evolution in ultra-low carbon medium manganese steel, Materials Characterization 173 (2021) 110920. [CrossRef]

- N. Nakada, K. Mizutani, T. Tsuchiyama, S. Takaki, Difference in transformation behavior between ferrite and austenite formations in medium manganese steel, Acta materialia 65 (2014) 251-258. [CrossRef]

- S. Liu, Z. Xiong, H. Guo, C. Shang, R. Misra, The significance of multi-step partitioning: Processing-structure-property relationship in governing high strength-high ductility combination in medium-manganese steels, Acta materialia 124 (2017) 159-172. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zou, Y. Xu, Z. Hu, X. Gu, F. Peng, X. Tan, S. Chen, D. Han, R. Misra, G. Wang, Austenite stability and its effect on the toughness of a high strength ultra-low carbon medium manganese steel plate, Materials Science and Engineering: A 675 (2016) 153-163. [CrossRef]

- Y. Han, J. Shi, L. Xu, W. Cao, H. Dong, TiC precipitation induced effect on microstructure and mechanical properties in low carbon medium manganese steel, Materials Science and Engineering: A 530 (2011) 643-651. [CrossRef]

- G. Tirumalasetty, M. Van Huis, C. Fang, Q. Xu, F. Tichelaar, D. Hanlon, J. Sietsma, H. Zandbergen, Characterization of NbC and (Nb, Ti) N nanoprecipitates in TRIP assisted multiphase steels, Acta Materialia 59(19) (2011) 7406-7415. [CrossRef]

- R.S. Varanasi, B. Gault, D. Ponge, Effect of Nb micro-alloying on austenite nucleation and growth in a medium manganese steel during intercritical annealing, Acta Materialia 229 (2022) 117786. [CrossRef]

- F. HajyAkbary, J. Sietsma, A.J. Böttger, M.J. Santofimia, An improved X-ray diffraction analysis method to characterize dislocation density in lath martensitic structures, Materials Science and Engineering: A 639 (2015) 208-218. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang, J. Hua, M. Kong, Y. Zeng, J. Liu, Z. Liu, Quantitative analysis of martensite and bainite microstructures using electron backscatter diffraction, Microscopy Research and Technique 79(9) (2016) 814-819. [CrossRef]

- X. Li, A. Ramazani, U. Prahl, W. Bleck, Quantification of complex-phase steel microstructure by using combined EBSD and EPMA measurements, Materials Characterization 142 (2018) 179-186. [CrossRef]

- S. Xu, X. Sun, X. Liang, J. Liu, Q. Yong, Effect of hot rolling deformation on microstructure and mechanical properties of a high-Ti wear-resistant steel, Acta Metall Sin 56(12) (2020) 1581-1591.

- D.M. Field, D.S. Baker, D.C. Van Aken, On the prediction of α-martensite temperatures in medium manganese steels, Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A 48 (2017) 2150-2163. [CrossRef]

- Q.L. Yong, Secondary Phases in Steels, Metallurgical Industry Press, Beijing, 2006.

- Z. Wang, Y. Zhang, G. Miyamoto, T. Furuhara, Formation of abnormal nodular ferrite with interphase precipitation in a vanadium microalloyed low carbon steel, Scripta Materialia 198 (2021) 113823. [CrossRef]

- G. Gao, B. Gao, X. Gui, J. Hu, J. He, Z. Tan, B. Bai, Correlation between microstructure and yield strength of as-quenched and Q&P steels with different carbon content (0.06–0.42 wt% C), Materials Science and Engineering: A 753 (2019) 1-10. [CrossRef]

- X. Ma, C. Miao, B. Langelier, S. Subramanian, Suppression of strain-induced precipitation of NbC by epitaxial growth of NbC on pre-existing TiN in Nb-Ti microalloyed steel, Materials & Design 132 (2017) 244-249. [CrossRef]

- W. Zhao, D. Zhou, S. Jiang, H. Wang, Y. Wu, X. Liu, X. Wang, Z. Lu, Ultrahigh stability and strong precipitation strengthening of nanosized NbC in alumina-forming austenitic stainless steels subjecting to long-term high-temperature exposure, Materials Science and Engineering: A 738 (2018) 295-307. [CrossRef]

- J. Yang, H. Bhadeshia, The dislocation density of acicular ferrite in steel welds, Welding Research Supplement 69 (1990) 305-307.

- T. Ungár, A. Borbély, The effect of dislocation contrast on x-ray line broadening: A new approach to line profile analysis, Applied Physics Letters 69(21) (1996) 3173-3175. [CrossRef]

- T. Ungár, I. Dragomir, Á. Révész, A. Borbély, The contrast factors of dislocations in cubic crystals: the dislocation model of strain anisotropy in practice, Journal of Applied Crystallography 32(5) (1999) 992-1002. [CrossRef]

- S. Takebayashi, T. Kunieda, N. Yoshinaga, K. Ushioda, S. Ogata, Comparison of the dislocation density in martensitic steels evaluated by some X-ray diffraction methods, ISIJ International 50(6) (2010) 875-882. [CrossRef]

- M. Santofimia, T. Nguyen-Minh, L. Zhao, R. Petrov, I. Sabirov, J. Sietsma, New low carbon Q&P steels containing film-like intercritical ferrite, Materials Science and Engineering: A 527(23) (2010) 6429-6439. [CrossRef]

- S. Morito, H. Yoshida, T. Maki, X. Huang, Effect of block size on the strength of lath martensite in low carbon steels, Materials Science and Engineering: A 438 (2006) 237-240. [CrossRef]

- K. Zhang, Z.D. Li, X.J. Sun, Q.L. Yong, J.W. Yang, Y.M. Li, P.L. Zhao, Development of Ti–V–Mo complex microalloyed hot-rolled 900-MPa-grade high-strength steel, Acta Metallurgica Sinica (English Letters) 28 (2015) 641-648.

- J. Chen, M. Lv, S. Tang, Z. Liu, G. Wang, Correlation between mechanical properties and retained austenite characteristics in a low-carbon medium manganese alloyed steel plate, Materials Characterization 106 (2015) 108-111. [CrossRef]

| Samples | RA / % | ferrite / % | SM / % |

| SPA20 | 25.9 | 53.8 | 20.3 |

| SPA40 | 15.6 | 50.6 | 33.8 |

| Samples |

Yield Strength / MPa |

Tensile Strength / MPa |

Total Elongation / % |

Akv at -20 °C / J |

Vγ / % |

| SPA20 | 882 ± 10 | 1341 ± 11 | 19.0 ± 1.5 | 36.7 ± 2.3 | 25.9 |

| SPA40 | 1097 ± 10 | 1521 ± 2 | 14.0 ± 1.0 | 33.3 ± 1.2 | 15.6 |

| Samples | Dislocation density (/m2) and strengthening (MPa) in ferrite | Dislocation density (/m2) and strengthening (MPa) in SM |

| SPA20 | 1×1014 / 149 | 1.375×1015 / 552 |

| SPA40 | 1×1014 / 149 | 2.109×1015 / 683 |

| Samples | C | Si | Mn | Mo |

| SPA20 | 0.6169 | 0.35 | 8.8 | 0.15 |

| SPA40 | 0.5753 | 0.35 | 7.0 | 0.15 |

| Samples | C | Si | Mn | Mo | EGS / μm |

| SPA20 | 0.05 | 0.3 | 2.8 | 0.2 | 1.26 |

| SPA40 | 0.05 | 0.3 | 2.5 | 0.2 | 1.19 |

| Samples | / MPa |

/ MPa |

/ MPa |

/ MPa |

/ MPa |

/ MPa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPA20 | 50 | 215 | 490 | 149 | 108 | 940 |

| SPA40 | 50 | 204 | 520 | 149 | 108 | 958 |

| Samples | C | Si | Mn | Mo | EGS / μm |

| SPA20 | 0.05 | 0.35 | 8.8 | 0.2 | 1.26 |

| SPA40 | 0.05 | 0.35 | 7.0 | 0.2 | 1.19 |

| Samples | / MPa |

/ MPa |

/ MPa |

/ MPa |

/ MPa |

/ MPa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPA20 | 50 | 352 | 490 | 553 | 108 | 1456 |

| SPA40 | 50 | 352 | 504 | 683 | 108 | 1598 |

| Samples | , calculated yield strength | yield strength Measured yield strength | |||

| SPA20 | 362 | 939 | 1456 | 895 | 882 |

| SPA40 | 355 | 958 | 1598 | 1080 | 1097 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).