1. Introduction

In recent years, the steel industry has been working towards the strategic goals of "carbon neutrality" and "peak carbon emissions," making carbon emission reduction a shared priority [

1]. This effort involves streamlining industrial production processes and adopting lightweight designs for products to minimize carbon footprint [

2]. Among the various types of steel, advanced high-strength steel (AHSS) stands out for its exceptional strength and plasticity, offering numerous applications to enhance equipment safety and achieve lightweight objectives [

3]. Current materials research focuses on pushing the performance of AHSS to ultra-high-strength levels, targeting 2 GPa. The realm of AHSS includes dual-phase steel (DP) [

4], complex-phase steel (CP) [

5], transformation-induced plasticity-aided steel (TRIP) [

6], twinning-induced plasticity steels (TWIP) [

7], austenitic stainless steels (ASS) [

8], quenching and partitioning processed steel (Q&P) [

9], and carbide-free bainitic (CFB) steel [

10]. In 2003, Speer et al. [

11] introduced the quenching and partitioning (Q&P) process, where steel is quenched and cooled within the martensite transformation temperature range after partial or full austenitization. This process facilitates the diffusion of carbon atoms from oversaturated martensite to untransformed austenite, thereby enriching the carbon content in the austenite. The outcome is a microstructure composed of martensite and well-stabilized retained austenite (RA) at room temperature. The martensite contributes to a higher ultimate tensile strength (UTS, 800-1500 MPa), while the TRIP effect enabled by RA leads to a significant increase in total elongation (TE, 10.0-30.0%) [

12,

13].

The mechanical properties of Q&P steel are intricately tied to several key factors, including the volume fraction, size, morphology, and distribution of its constituent phases, as well as precise control over heat treatment parameters. Over time, researchers have sought to optimize the Q&P heat treatment process parameters to enhance the overall mechanical performance of the steel. For example, by fine-tuning the quenching temperature, the initial volume fractions of martensite and untransformed austenite can be accurately determined [

14]. Moreover, elevating the quenching temperature has the added effect of promoting the formation of blocky RA [

15]. The choice of partitioning temperature allows for manipulation of the extent of martensite transformation. The combined impact of partitioning temperature and partitioning time plays a crucial role in the carbon partitioning process, thereby influencing the stability of RA [

16,

17]. Additionally, some researchers have explored the influence of heating rate on the microstructural evolution and mechanical properties of Q&P steel [

18]. Ultra-fast heating can delay the recrystallization of deformed ferrite, and increase the nucleation rate of austenite, resulting in a finer austenite grain size. As evidenced by the results, subjecting Q&P steel to ultra-rapid heating (at a rate of 300℃/s) yields a significant strength boost, raising it from 980 MPa to 1180 MPa compared to conventionally heated Q&P steel.

Traditional Q&P treatments have conventionally been carried out on offline heat treatment production lines subsequent to hot rolling. This method entails high energy consumption and often results in low production efficiency. Responding to the growing need for more streamlined and efficient production processes, an increasing number of researchers are now directing their focus towards post-hot rolling direct quenching and partitioning (DQP) processes [

19]. In contrast to the traditional Q&P approach, DQP treatment involves a dynamic partitioning process. It leverages the residual heat from hot-rolled steel plates for partitioning, effectively reducing the energy consumption associated with repeated reheating cycles. Furthermore, the DQP process offers several advantages, including the ability to attain the desired microstructure and excellent mechanical properties [

19,

20,

21,

22]. For instance, Tan et al. [

20] applied DQP and isothermal partitioning processes to low-carbon steel, investigating the distinctions in microstructure and mechanical properties under these various treatments. The findings revealed that, in comparison to isothermal partitioning, DQP samples exhibited narrower martensite laths and higher dislocation densities. These characteristics became more pronounced with an increase in the cooling rate during the dynamic partitioning process, resulting in higher tensile strength (1300-1600 MPa) and similar elongation (14%-18%). In a separate study, R. Parthiban et al. [

21] compared the mechanical properties of cast steel subjected to quenching and partitioning treatment, DQP treatment following thermo-mechanical controlled processing (TMCP), and offline quenching and partitioning treatment (SQP) after TMCP. The results demonstrated that the tensile strength and elongation changed from 882 MPa and 18.5% for cast steel to 1398 MPa and 11% for TMCP-DQP treatment, and 1327 MPa and 13% for TMCP-SQP treatment. This illustrates that the high-density dislocations and fine grains produced through the TMCP process can significantly enhance the hardening ability of steel without notably affecting its elongation.

While the current AHSS produced through the DQP process exhibits impressive mechanical properties, surpassing the 2 GPa tensile strength threshold remains a formidable challenge. A comprehensive examination of the synergistic effects of TMCP technology and dynamic partitioning processes on the mechanical properties of steel, as well as the underlying microstructure evolution mechanisms, is currently lacking. Therefore, building upon prior investigations [

23,

24,

25], this study aimed at developing an AHSS with a tensile strength of 2.2 GPa, while preserving exceptional plasticity and toughness. Compared to traditional hot-rolled quenching and tempering (HR-QT), this objective will be accomplished by a process that integrates thermo-mechanical rolling with direct quenching and partitioning (TMCP-DQP). Multiple characterization techniques will be employed to examine phase compositions, martensitic structural characteristics, RA volume fractions, and internal carbon content. Furthermore, the study will dissect the microstructure evolution mechanisms of steel during the TMCP-DQP process.

4. Discussion

Compared to HR-QT steel, the outstanding mechanical performance of TMCP-DQP steel is closely related to its microstructural evolution, as illustrated in

Figure 9. In the first stage of the austenitization process (

Figure 9b), an appropriate holding time ensures a uniform element distribution while preventing excessive grain coarsening of the austenite grains, which could lead to a deterioration in mechanical performance. Subsequently, during the two-stage controlled rolling process (

Figure 9c), the grains are elongated and refined, and the dislocation density generated by intragranular deformation increases significantly. Due to the higher temperature, dynamic recrystallization is evident, ensuring that the PAG remain fine when cooling to M

s (300 ℃), as depicted in

Figure 5. This fine state serves as the foundation for the formation of a refined substructure during martensitic transformation. Immediately after the controlled rolling, accelerated water cooling is applied (

Figure 9d). This limits the growth of over-saturated and deformation-induced carbides during the cooling process and restricts the excessive growth of grains and subgrain coarsening that may occur after the second-stage rolling. This is advantageous for obtaining fine martensite laths, which contributes significantly to the strength and toughness of the material. During the air-cooling process from the cooling endpoint temperature (450 ℃) to M

s (300 ℃), static recovery occurs within the subcooled austenite (

Figure 9e). During this phase, dislocations generated by deformation are rearranged, leading to a reduction in dislocation density and the elimination or reduction of residual stresses. This helps avoid plastic damage that can occur when a large number of transformation dislocations coexist with deformation-induced dislocations during the martensitic transformation. As the temperature decreases to M

s, the measured air cooling rate of the experimental steel is 0.3 ℃/s (

Figure 2b), which is higher than the critical cooling rate of 0.05 ℃/s required for martensitic transformation, leading to the formation of martensite (

Figure 9f). During this transformation phase, on the one hand, the martensitic transformation process is relatively "slow". On the other hand, the remaining austenite that has not yet transformed continues to experience carbon atom diffusion partitioning with the newly transformed martensite (

Figure 9g). The partitioning time is sufficient to stabilize the untransformed austenite. This mechanism is similar to the one-step Q&P process. Finally, as the temperature drops below M

f, high-carbon RA with a volume fraction of 7.7 vol%, and a multitude of lath martensite is achieved. The RA exists as thin films within the fine gaps between the laths (

Figure 8a).

The stability of RA is crucial for the mechanical properties of ultra-high-strength steels. The most effective method to enhance the stability of RA is to promote carbon enrichment. Additionally, the size and morphology of austenite also play a crucial role in this process [

36,

37,

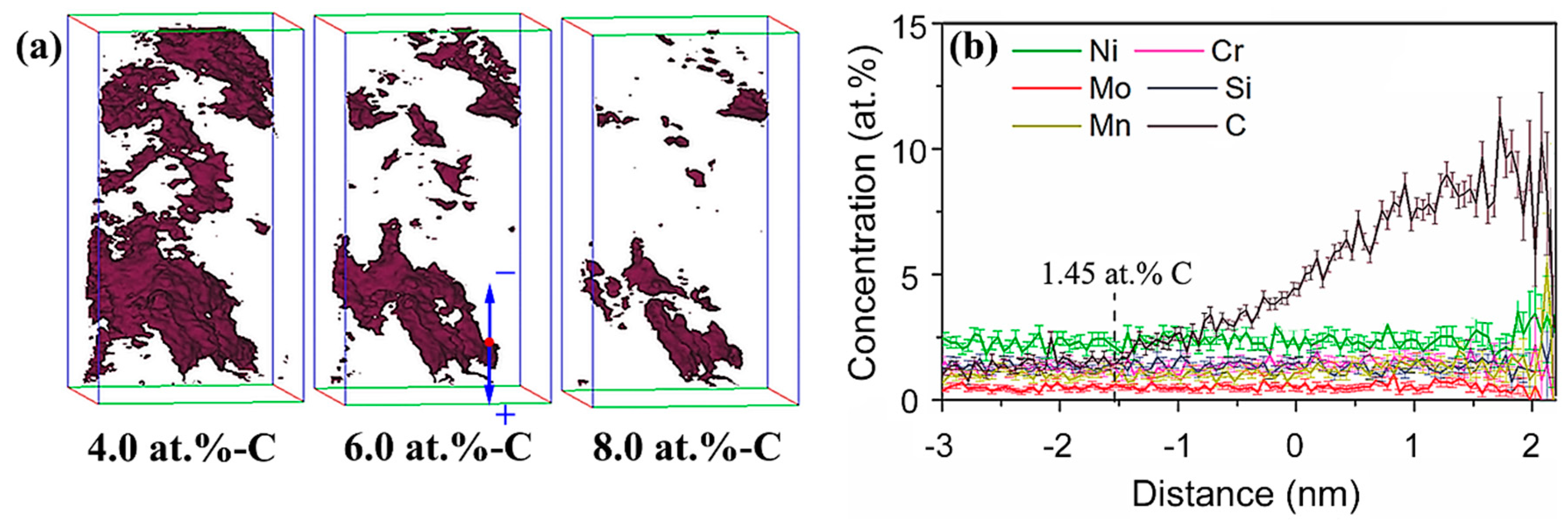

38]. To visually characterize the morphology of RA in TMCP-DQP steel and detect its enriched carbon concentration, a three-dimensional atom probe (3DAP) layer analysis was employed. Integrated Visualization and Analysis Software (IVAS) was used to analyze the elemental distribution in the obtained regions. The "equal concentration surface" method was used to mark regions with a specified carbon concentration value, thus forming an equal concentration surface. In this case, a carbon concentration threshold value of 4.0 at.% was defined as the boundary for the RA regions, and equal concentration surface analysis parameters of 4.0, 6.0, and 8.0 at.% carbon concentrations were chosen to obtain the three-dimensional distribution of carbon-enriched microregions in the steel, as shown in

Figure 9a. It can be observed that the shape of the RA regions defined by the 4.0 at.% equal concentration surface is primarily film-like, with some areas containing smaller, highly carbon-enriched block-like regions. As the equal concentration surface gradually increases to 6.0 and 8.0 at.%, the RA regions enclosed by the equal concentration surface slightly reduced in size, with an increased proportion of block-like regions. This indicates that the distribution of carbon elements inside the entire RA region is not entirely uniform, and there exists a transition layer where the carbon concentration gradually increases towards the interior.

Composition analysis was performed on the RA in

Figure 10a. A carbon concentration of 6.0 at.% was selected as the reference plane, with the position representing a statistical concentration of carbon at 6.0 at.% marked as 0 nm. The concentration distribution of the major alloying elements at different distances from the reference plane is shown in

Figure 10b. It is obvious that the carbon concentration varies significantly with position, with a transition region of only 2 nm from enrichment to the equal concentration surface, while the concentrations of other elements remain nearly constant with position. As the sampled region used for concentration statistics becomes smaller in higher concentration regions, there is a relatively larger concentration error displayed in the graph. The average carbon content in the RA phase reached 7.1 at.%, which closely matches the XRD results. In stark contrast, the carbon content in the martensite phase was slightly lower than the average carbon content of the experimental steel. Comparing the content of other alloying elements in the RA and martensite regions, it is evident that only carbon atoms underwent partitioning during the dynamic partitioning process.

Table 3.

content of some elements in both the martensite and retained austenite phases (at.%).

Table 3.

content of some elements in both the martensite and retained austenite phases (at.%).

| Phase |

C |

Si |

Mn |

Cr |

Ni |

Mo |

| M |

1.45 |

1.36 |

1.02 |

1.24 |

2.25 |

0.27 |

| RA |

7.1 |

1.38 |

1.16 |

1.39 |

2.34 |

0.32 |

The diffusion of carbon during the partitioning process is highly sensitive to both time and temperature [

39]. Short-duration partitioning treatments, typically lasting a few tens of seconds, facilitate carbon diffusion from martensite to RA, leading to carbon enrichment in the RA and enhancing its stability. The difference in carbon chemical potential between the two phases provides the driving force for carbon partitioning. On the other hand, in the TMCP-DQP process, longer partitioning times can lead to the formation of carbides due to the enrichment of carbon diffusion, as shown in

Figure 7. Therefore, during the self-tempering process of martensite, there is a competitive relationship between effective carbon partitioning and carbide formation processes [

40].

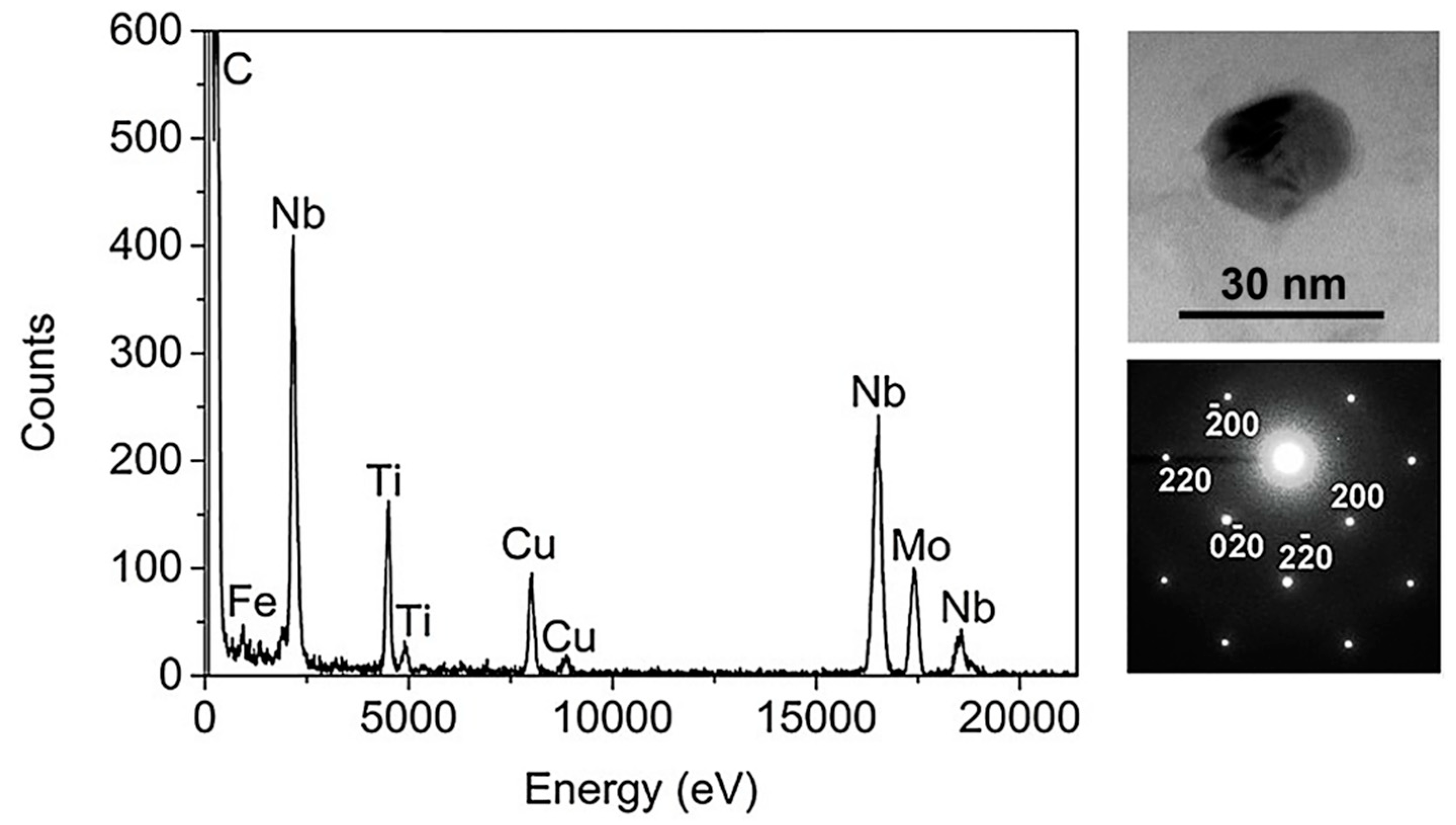

To observe the carbide particles in TMCP-DQP steel in greater detail, representative carbides were obtained using an extraction and replication technique. TEM images and selected area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns of these carbide particles are shown in

Figure 11. The carbide particles have sizes ranging from approximately 15 to 30 nm. The chemical composition of these precipitates was analyzed through Energy-Dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectroscopy. The results of the EDX analysis revealed that these precipitate particles within the TMCP-DQP steel contain not only Nb and Ti elements but also small amounts of Mo, indicating that they are carbides containing Nb, Ti, and Mo. Quantitative EDX analysis results showed the Nb/Ti and Ti/Mo elemental ratios within these particles to be about 2.99 ± 0.60 and 2.09 ± 0.84, respectively. According to the corresponding diffraction patterns in

Figure 10, these carbide particles exhibit a NaCl-type crystal lattice structure, confirming that they are MC-type carbides [

41].

The ultrahigh strength exceeding 2 GPa in TMCP-DQP steel presented in this study can be attributed to several critical factors. First, it benefits from the controlled rolling process and the dynamic recrystallization that leads to the formation of fine austenite during the phase transformation process. This results in the development of a fine substructure (Packet and Block structures, as illustrated in

Table 1), which initiates grain refinement strengthening. Additionally, the presence of fine martensite platelets in the microstructure, along with dislocations generated through deformation and phase transformation, contributes to further strengthening. Furthermore, the ultrafine twinned microstructure plays an essential role in enhancing the martensite. Moreover, during the self-tempering process between the M

s and M

f temperatures in TMCP-DQP steel, nanoscale carbides precipitate, providing an additional strengthening effect. In contrast, HR-QT steel experiences a re-austenitization process, leading to some coarsening of the PAG and microstructures. This process results in wider martensite platelets. The variation in tempering degrees affects the density of phase transformation dislocations and the growth of carbide particles, ultimately leading to a reduction in strength. Furthermore, the excellent ductility of TMCP-DQP steel benefits from the TRIP effect, achieved through the dynamic carbon partitioning process during the self-tempering phase between M

s and M

f temperatures. This effect effectively alleviates stress concentration, promotes strain hardening, and delays necking [

42,

43,

44]. Additionally, the relaxation phase before martensitic transformation eliminates a portion of the dislocations. During the martensite transformation, the slow cooling process leads to low-temperature self-tempering, which, to some extent, helps eliminate internal stresses. In contrast, HR-QT steel lacks stable RA and necessitates an increase in tempering temperature to approximately 250℃ to eliminate quenching brittleness and achieve equivalent ductility and impact resistance to TMCP-DQP steel. However, this inevitably results in a loss of strength, making it challenging to achieve both ultrahigh strength and excellent ductility simultaneously.

5. Conclusions

(1) The Fe-0.4C-1Mn-0.6Si (wt.%) steel, processed through the TMCP-DQP technique, has demonstrated excellent mechanical properties while significantly shortening the manufacturing process. It achieves a tensile strength of 2233 MPa, accompanied by an elongation of 11.9%, a hardness of 624 HBW, and an impact energy of 28.5 J at -20 ℃. In contrast, steel treated by HR-QT processing exhibits a wide range of tensile strengths, from 2162 MPa to 1700 MPa, and elongation ranging from 5.2% to 12.2%. The Brinell hardness values and impact energies span from 539.6 HB to 684.8 HB and 16.5 J to 29.1 J, respectively. Both tensile strength and hardness decrease as tempering temperature rises, whereas elongation and impact toughness initially increase and then decrease with increasing tempering temperature. Mild temper embrittlement is observed at tempering temperatures greater than 250℃. The most favorable comprehensive mechanical performance is achieved at a tempering temperature of 250 ℃, with a tensile strength of 1930.7 MPa and an elongation of 12.2%.

(2) TMCP-DQP steel exhibits a microstructure dominated by lath martensite, including RA in a film-like form, nanoscale rod-shaped carbides, and a small number of fine twin boundaries. The average width of the martensite laths is 363.5 nm, with a substantial presence of dislocation tangles on the lath boundaries. The relative content of RA reaches 7.7 vol.%, with an average carbon content of 7.1 at.%. Compared to HR-QT steel, the TMCP-DQP process results in a finer microstructure and substructure. The PAG size is 11.91 μm, subsequently forming packet and block structures with widths of 5.12 μm and 1.63 μm during the subsequent phase transformation.

(3) The ultra-high strength of TMCP-DQP steel is attributed to grain refinement caused by fine austenite formed during controlled rolling and dynamic recrystallization and fine martensite laths generated in the subsequent martensitic transformation. Furthermore, the nanoscale carbides and dislocations generated by deformation and phase transformation provide additional strengthening to the TMCP-DQP steel. The good ductility and toughness of TMCP-DQP steel result from the TRIP effect induced by the stable RA obtained through the dynamic carbon partitioning process during the air-cooling stage. Additionally, the relaxation stage before martensite transformation eliminates a portion of the dislocations generated from deformation, and the low-temperature self-tempering during slow cooling of the final stage to some extent alleviates internal stresses. These combined factors ensure that TMCP-DQP steel not only achieves ultra-high strength of 2.2 GPa but also exhibits outstanding ductility and toughness.

Figure 1.

Heat treatment process of the studied steel. (a)TMCP-DQP (b)HR-QT.

Figure 1.

Heat treatment process of the studied steel. (a)TMCP-DQP (b)HR-QT.

Figure 2.

Temperature versus time curve (a) and differential curve (b) during the air cooling stage in the TMCP-DQP process.

Figure 2.

Temperature versus time curve (a) and differential curve (b) during the air cooling stage in the TMCP-DQP process.

Figure 3.

Mechanical performance of TMCP-DQP steel and HR-QT steel at different tempering temperatures. (a) Engineering stress-strain curves, (b) tensile strength and elongation, (c) Brinell hardness and impact energy, (d) comparison of TMCP-DQP steel with other steels with similar C (0.4 wt.%) content in terms of product of strength and elongation versus tensile strength.

Figure 3.

Mechanical performance of TMCP-DQP steel and HR-QT steel at different tempering temperatures. (a) Engineering stress-strain curves, (b) tensile strength and elongation, (c) Brinell hardness and impact energy, (d) comparison of TMCP-DQP steel with other steels with similar C (0.4 wt.%) content in terms of product of strength and elongation versus tensile strength.

Figure 4.

Microstructures of TMCP-DQP steel and HR-QT steel. (a) SEM image of TMCP-DQP steel, (b-d) SEM images of HR-QT200, HR-QT300, and HR-QT400 steels, (e) LAGBs and HAGBs in TMCP-DQP steel, (j-l) LAGBs and HAGBs in HR-QT200, HR-QT300, and HR-QT400 steels (LAGBs between 2° and 15° are represented by blue lines, while HAGBs with orientation differences greater than 15° are represented by black lines), (i) EBSD inverse pole figure (IPF) map of TMCP-DQP steel, (j-l) EBSD inverse pole figure (IPF) map of HR-QT200, HR-QT300, and HR-QT400 steels.

Figure 4.

Microstructures of TMCP-DQP steel and HR-QT steel. (a) SEM image of TMCP-DQP steel, (b-d) SEM images of HR-QT200, HR-QT300, and HR-QT400 steels, (e) LAGBs and HAGBs in TMCP-DQP steel, (j-l) LAGBs and HAGBs in HR-QT200, HR-QT300, and HR-QT400 steels (LAGBs between 2° and 15° are represented by blue lines, while HAGBs with orientation differences greater than 15° are represented by black lines), (i) EBSD inverse pole figure (IPF) map of TMCP-DQP steel, (j-l) EBSD inverse pole figure (IPF) map of HR-QT200, HR-QT300, and HR-QT400 steels.

Figure 5.

Prior austenite grain images of TMCP-DQP steel and HR-QT steel. (a, b) prior austenite grain boundaries obtained by the etching method for TMCP-DQP steel and HR-QT400 steel, (c, d) prior austenite grain images obtained by EBSD data reverse reconstruction method for TMCP-DQP steel and HR-QT400 steel.

Figure 5.

Prior austenite grain images of TMCP-DQP steel and HR-QT steel. (a, b) prior austenite grain boundaries obtained by the etching method for TMCP-DQP steel and HR-QT400 steel, (c, d) prior austenite grain images obtained by EBSD data reverse reconstruction method for TMCP-DQP steel and HR-QT400 steel.

Figure 6.

TEM images of TMCP-DQP steel and HR-QT steel. (a) martensite laths in TMCP-DQP steel, (b) twin structure and diffraction pattern in TMCP-DQP steel, (c) martensite laths in HR-QT300 steel.

Figure 6.

TEM images of TMCP-DQP steel and HR-QT steel. (a) martensite laths in TMCP-DQP steel, (b) twin structure and diffraction pattern in TMCP-DQP steel, (c) martensite laths in HR-QT300 steel.

Figure 7.

Carbide morphology in TMCP-DQP steel and HR-QT steel. (a) SEM image of carbides in HR-QT300 steel, (b) TEM images of carbides in TMCP-DQP steel along with corresponding EDS analysis, (c) SEM image of carbides in HR-QT300 steel, (d) TEM images of carbides in HR-QT300 steel.

Figure 7.

Carbide morphology in TMCP-DQP steel and HR-QT steel. (a) SEM image of carbides in HR-QT300 steel, (b) TEM images of carbides in TMCP-DQP steel along with corresponding EDS analysis, (c) SEM image of carbides in HR-QT300 steel, (d) TEM images of carbides in HR-QT300 steel.

Figure 8.

Morphology of retained austenite in both TMCP-DQP steel and HR-QT300 steel. (a) TEM morphology of retained austenite in TMCP-DQP steel, (b) XRD results of TMCP-DQP steel before and after tensile testing, as well as HR-QT300 steel.

Figure 8.

Morphology of retained austenite in both TMCP-DQP steel and HR-QT300 steel. (a) TEM morphology of retained austenite in TMCP-DQP steel, (b) XRD results of TMCP-DQP steel before and after tensile testing, as well as HR-QT300 steel.

Figure 9.

Microstructural evolution schematic of TMCP-DQP steel. (a) TMCP-DQP process, (b) austenitization microstructures, (c) post-TMCP microstructures, (d) microstructures during rapid water cooling, (e) microstructures during the relaxation phase, (f) carbon partitioning schematic, (g) martensite structure schematic.

Figure 9.

Microstructural evolution schematic of TMCP-DQP steel. (a) TMCP-DQP process, (b) austenitization microstructures, (c) post-TMCP microstructures, (d) microstructures during rapid water cooling, (e) microstructures during the relaxation phase, (f) carbon partitioning schematic, (g) martensite structure schematic.

Figure 10.

Retained austenite in TMCP-DQP steel. (a) three-dimensional distribution of retained austenite at different carbon equal concentration surfaces, (b) distribution of the major alloying elements at various distances from the 6.0 at.% carbon equal concentration surface.

Figure 10.

Retained austenite in TMCP-DQP steel. (a) three-dimensional distribution of retained austenite at different carbon equal concentration surfaces, (b) distribution of the major alloying elements at various distances from the 6.0 at.% carbon equal concentration surface.

Figure 11.

Typical morphology of the precipitate particles in TMCP-DQP steel along with their corresponding EDX spectra and electron diffraction patterns.

Figure 11.

Typical morphology of the precipitate particles in TMCP-DQP steel along with their corresponding EDX spectra and electron diffraction patterns.

Table 1.

Dominant chemical compositions of the studied steel (wt.%).

Table 1.

Dominant chemical compositions of the studied steel (wt.%).

| Elements |

C |

Si |

Mn |

Cr |

Ni |

Mo |

Nb |

Ti |

Fe |

| wt.% |

0.40 |

0.61 |

1.06 |

1.20 |

2.05 |

0.54 |

0.062 |

0.016 |

Bal. |

Table 2.

Microstructures and substructures size statistics for TMCP-DQP steel and HR-QT steel.

Table 2.

Microstructures and substructures size statistics for TMCP-DQP steel and HR-QT steel.

| |

Prior austenite grain size/μm |

Packet width/μm |

Block width/μm |

| TMCP-DQP |

11.91±0.61 |

5.12±0.21 |

1.63±0.06 |

| HR-QT200 |

15.05±0.47 |

5.63±0.18 |

2.37±0.08 |

| HR-QT300 |

15.05±0.47 |

6.26±0.16 |

2.73±0.08 |

| HR-QT400 |

15.05±0.47 |

7.47±0.16 |

3.02±0.05 |