3.1. Effects of Rolling Processing on Surface Morphology and Roughness

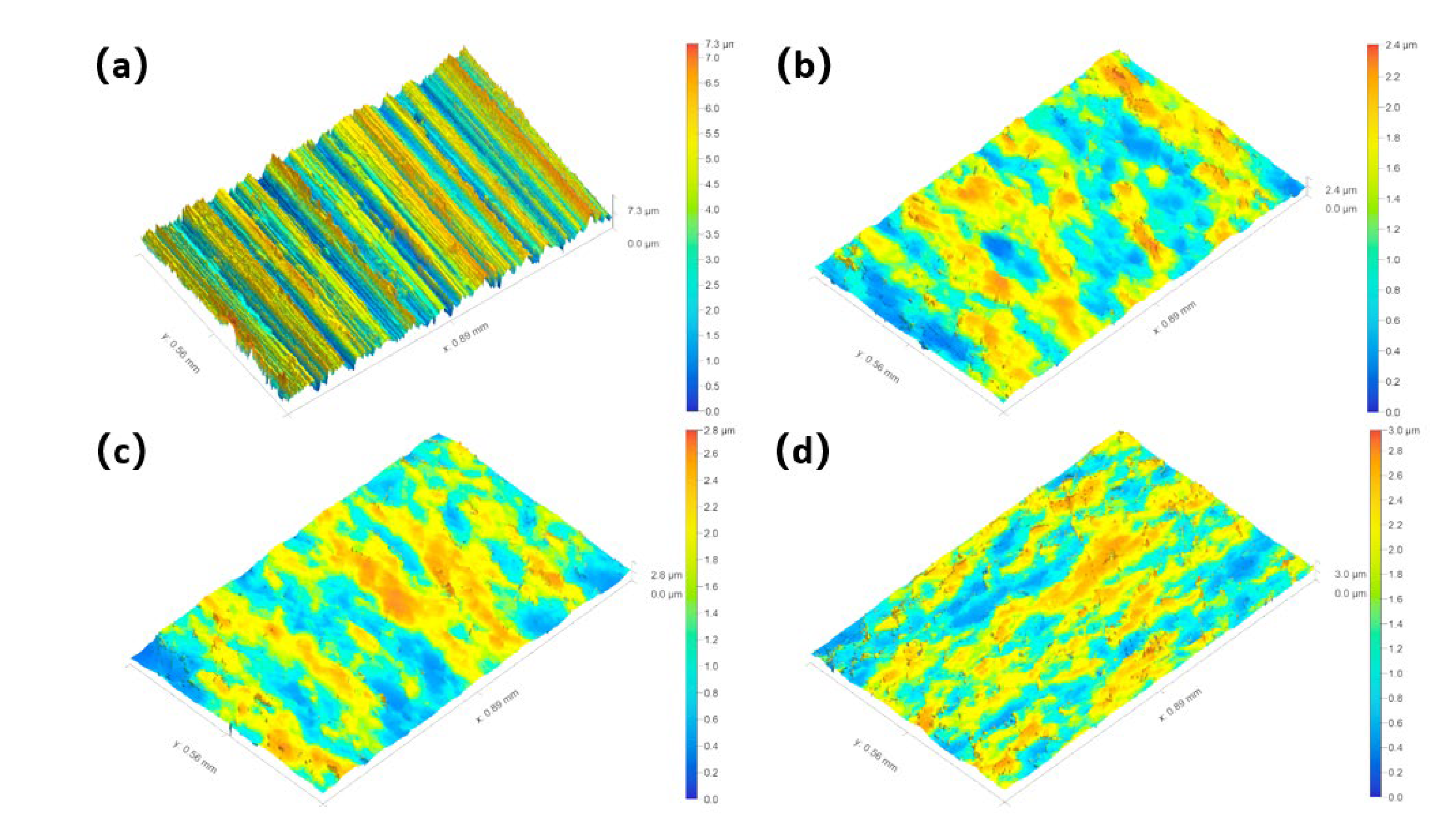

Figure 3.1 displays the three-dimensional surface morphologies of four different specimens: hard-turned (HT), USRP-0.20 MPa, USRP-0.35 MPa, and USRP-0.50 MPa. The as-turned 35CrMo steel surface exhibits numerous deep scratches and grooves. After USRP treatments under different parameters, the surface topography undergoes significant changes. Under the combined effect of ultrasonic high-frequency impact and rolling, pronounced plastic deformation occurs on the material surface, effectively eliminating scratches and grooves and achieving a "peak-removing and valley-filling" effect, resulting in a near-mirror finish.

As the static pressure of the ultrasonic roller increases, fine metallic particles gradually become visible on the sample surface, accompanied by the formation of a relief-like morphology resembling a layered structure[

7,

8], which is attributed to enhanced flow-induced plastic deformation near the surface. However, when the static pressure exceeds a critical threshold, over-rolling occurs, introducing excessive plastic deformation and new surface defects such as cracks, protrusions, or depressions, thereby increasing surface roughness.

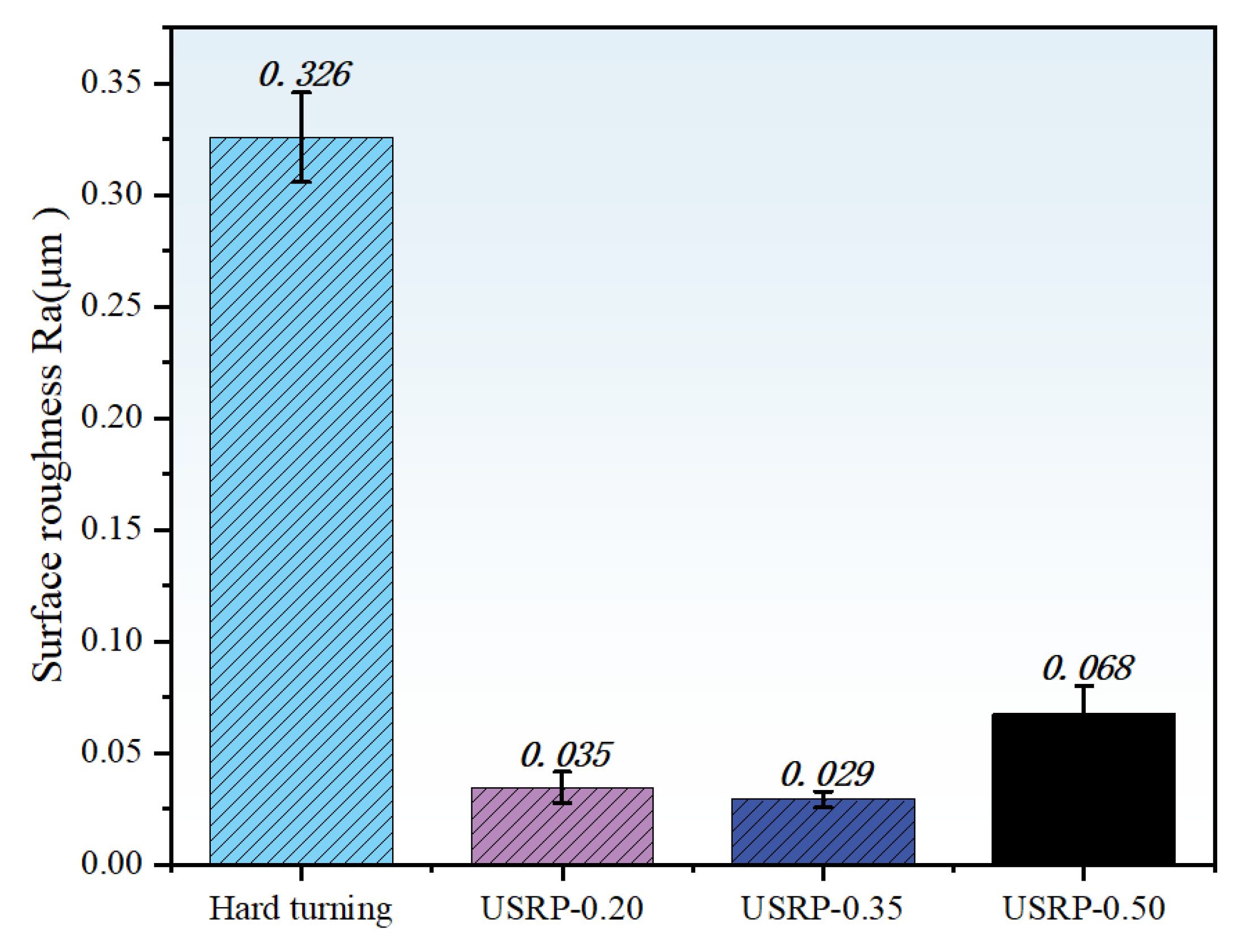

In summary, USRP effectively reduces surface roughness, provided that the static pressure is controlled to avoid the negative effects associated with over-rolling. Based on the quantitative analysis of surface topographies (

Figure 3.1), the surface roughness values under different conditions were obtained, as summarized in

Figure 3.2. The results indicate that compared to the hard-turned sample (with an arithmetic mean deviation,

Ra = 0.326 μm), the

Ra values of the USRP-0.20 MPa and USRP-0.35 MPa samples were significantly reduced to 0.034 μm and 0.043 μm, respectively. However, when the static pressure increased to 0.50 MPa, the

Ra value rebounded to 0.067 μm, consistent with the previous analysis.

These findings demonstrate that while USRP generally improves surface quality, excessive static pressure may introduce adverse effects, thereby diminishing the enhancement in surface integrity. Therefore, precise control of the rolling parameters is essential in practical applications to achieve optimal surface quality.

Figure 3.

2. Surface roughness of 35CrMo before and after ultrasonic rolling.

Figure 3.

2. Surface roughness of 35CrMo before and after ultrasonic rolling.

3.2. Residual stress distribution after rolling process

Residual stress refers to the internal stress that remains in a material after external forces are removed, typically resulting from material heterogeneity, manufacturing processes (such as welding, forging, or quenching), or differences in thermal expansion coefficients. Residual stresses can be categorized into residual tensile stress and residual compressive stress. Residual tensile stress may promote crack propagation and degrade mechanical properties, whereas residual compressive stress helps inhibit crack initiation and growth, thereby enhancing fatigue resistance. USRP induces severe plastic deformation in the near-surface region, leading to the formation of a high gradient of residual compressive stress[

9,

10].

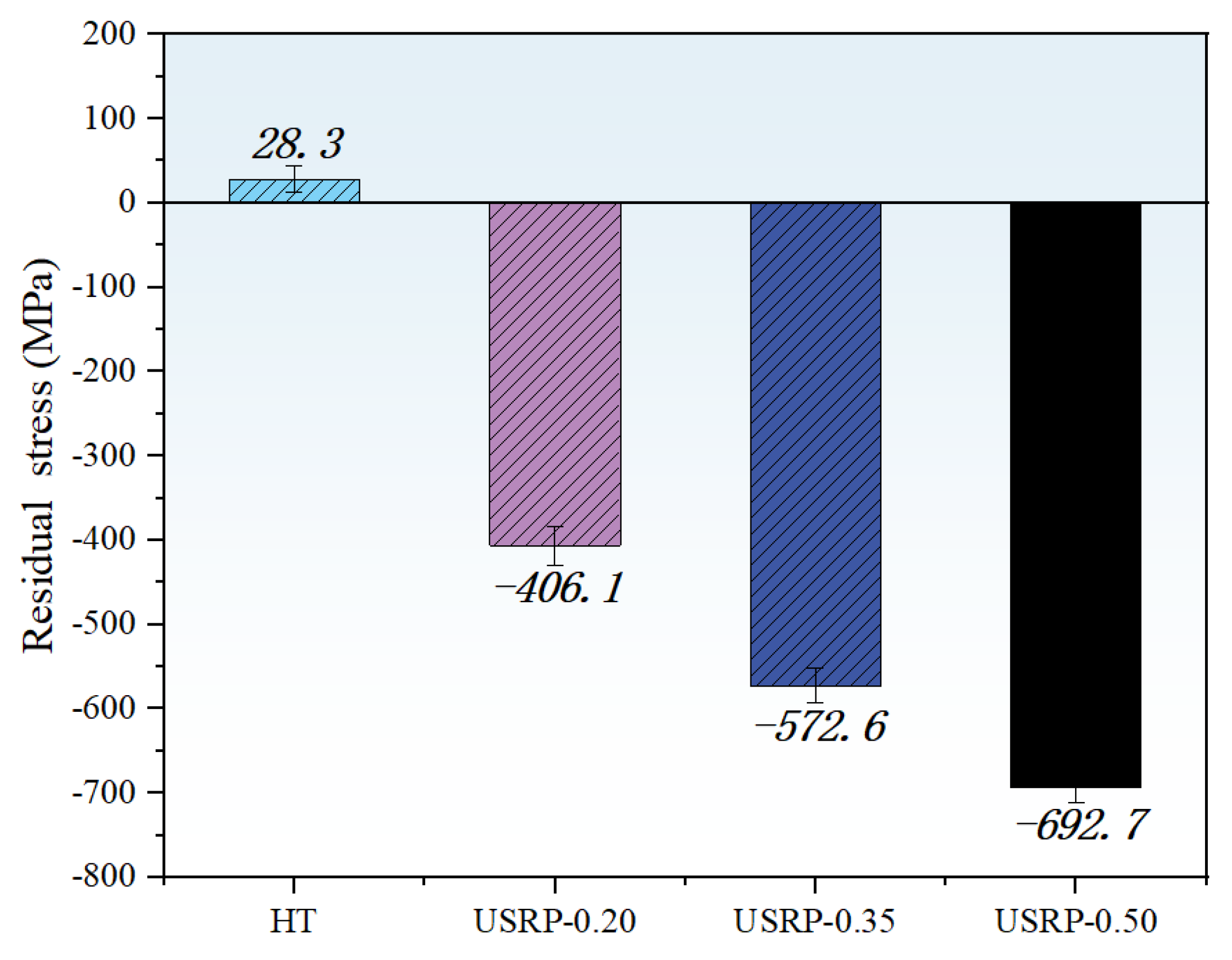

Figure 3.3 shows the changes in surface residual stress of 35CrMo steel before and after USRP treatment. For the HT sample, the residual stress was measured parallel to the turning marks, while for the USRP-treated samples, the measurement direction was aligned with the tool path (consistent with the turning direction). The untreated turned specimen exhibited a residual tensile stress of approximately 28.3 MPa, indicating that the hard turning process introduced tensile deformation in the surface. After USRP treatment, the surface of the 35CrMo steel showed compressive residual stresses. These stresses primarily originate from lattice distortion induced by compressive deformation during the rolling process[

11].

As the static pressure increased, the surface compressive residual stress significantly intensified, rising from –401.6 MPa under USRP-0.20 MPa to –692.7 MPa under USRP-0.50 MPa. This indicates that higher rolling pressure effectively enhances the residual compressive stress state at the surface.

Figure 3.

3.Surface residual stress of 35CrMo before and after ultrasonic rolling: (a) Hard turning; (b) USRP-0.20 MPa; (c) USRP-0.35 MPa; (d) USRP-0.50 Mpa.

Figure 3.

3.Surface residual stress of 35CrMo before and after ultrasonic rolling: (a) Hard turning; (b) USRP-0.20 MPa; (c) USRP-0.35 MPa; (d) USRP-0.50 Mpa.

It is noteworthy that the residual compressive stress formed in the surface and near-surface regions of 35CrMo steel is primarily induced by plastic deformation during the rolling process. Specifically, the external force applied by the tool head causes the material to undergo severe plastic strain, resulting in substantial dislocation multiplication and a notable increase in surface compressive stress. Furthermore, mutual mechanical interaction between refined grains also contributes to the generation of compressive stress.

Residual compressive stress effectively inhibits crack initiation and propagation, whereas residual tensile stress may reduce the load-bearing capacity of the material. Therefore, the high compressive residual stress layer introduced by USRP can significantly enhance the load-carrying capacity of 35CrMo steel and prolong the service life of components. It should be noted, however, that excessive rolling pressure may not further increase the compressive residual stress but instead impair surface integrity through the introduction of microcracks or other defects, thereby diminishing the overall strengthening effect..

3.3. Microscopic morphology after rolling process

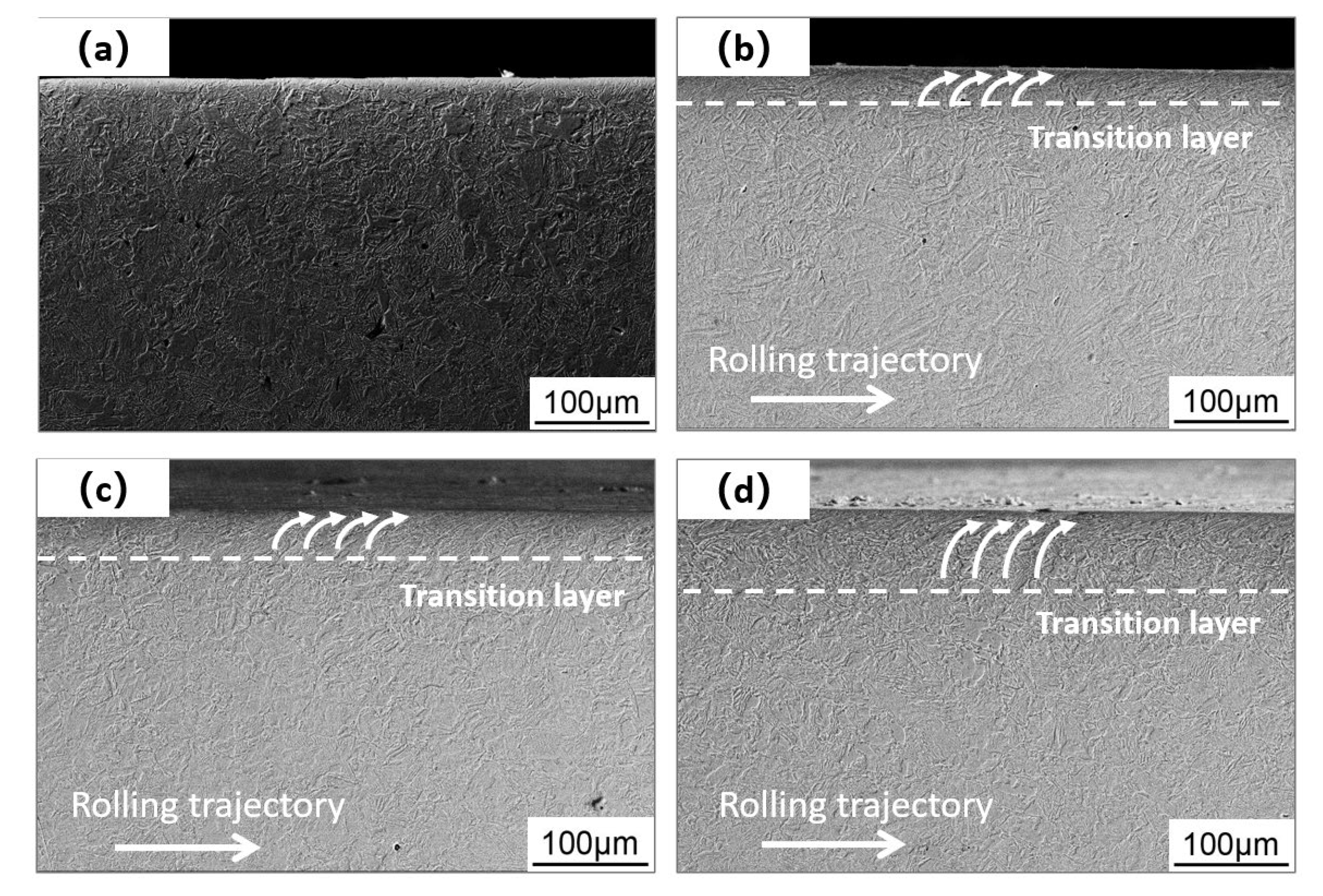

This The microscopic morphology of the four specimens exhibits distinct flow-induced plastic deformation characteristics in their surface layers. Systematic microstructural observations reveal significant transformations within the material.

As illustrated in

Figure 3.4, SEM imaging demonstrates that USRP induces pronounced alterations in the morphological features of the 35CrMo steel surface microstructure. The surface edges become remarkably sharp, while the original "white layer zone" transitions into an extremely thin "black layer zone"[

12]. This transformation directly reflects a fundamental shift in the deformation mechanism of the surface layer.

Comparative analysis indicates that conventional turning primarily induces tensile deformation aligned parallel to the surface, whereas ultrasonic surface rolling imposes intense compressive deformation predominantly oriented perpendicular to the surface. Further microstructural characterization reveals that ultrasonic surface rolling processing not only induces compressive deformation along the normal direction but also generates distinct micro-torsional features in the surface martensite and tempered sorbite structures, with preferential alignment parallel to the rolling tool trajectory. Crucially, increasing static pressure within the process parameters significantly enhances both the magnitude and penetration depth of this torsional deformation, manifesting as (i) intensified plastic strain in surface metallic structures, (ii) pronounced grain fragmentation and refinement, and (iii) increasingly complex plastic flow patterns[

13,

14], ultimately forming gradient-strengthened layers with characteristic thicknesses of 35 μm, 50 μm, and 75 μm.

Figure 3.

4.Microstructure of the longitudinal section of 35CrMo before and after ultrasonic surface rolling: (a) Hard turning; (b) USRP-0.20 MPa; (c) USRP-0.35 MPa; (d) USRP-0.50 MPa.

Figure 3.

4.Microstructure of the longitudinal section of 35CrMo before and after ultrasonic surface rolling: (a) Hard turning; (b) USRP-0.20 MPa; (c) USRP-0.35 MPa; (d) USRP-0.50 MPa.

Microstructural observation alone is insufficient to comprehensively elucidate the gradient strengthening mechanism induced by ultrasonic rolling on the 35CrMo surface.

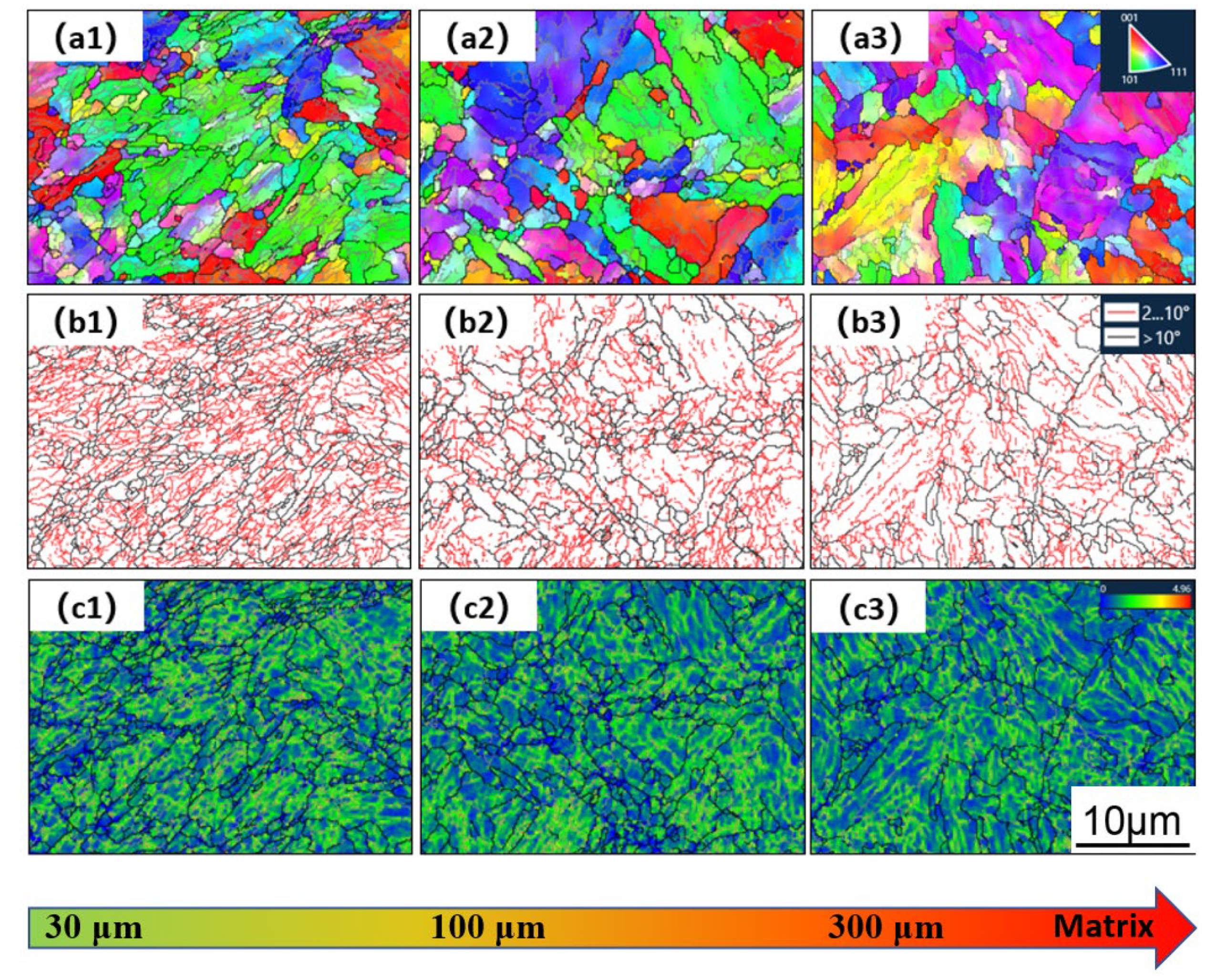

Figure 3.5 presents the EBSD morphologies of the most severely deformed USRP-0.50MPa specimen at varying depths. Since the ultrafine grains in the topmost layer are prone to damage and difficult to capture, the analysis initiates from the subsurface grain layer. The results demonstrate that martensite at different depths undergoes varying degrees of plastic deformation. Notably, significant grain refinement occurs in the subsurface region (~30 μm below the surface), exhibiting a gradient distribution characteristic with increasing depth (

Figure 3.5(a)). Specifically, within the 30~100 μm depth range, the extent of plastic deformation gradually diminishes. While grain sizes increase compared to the surface layer, they maintain a high density of subgrain boundaries, forming a transitional deformed microstructure. Beyond 300 μm toward the matrix, the subgrain boundary density drops sharply, and grains progressively revert to the original heat-treated coarse crystals of the 35CrMo matrix. This phenomenon arises from the plastic deformation of surface grains under high-frequency impact and rolling. Such a surface-to-core gradient distribution not only ensures high surface strength but also prevents abrupt property transitions that could lead to hardened layer exfoliation, achieved through progressive subgrain boundary transitions.

Figure 3.

5.Microstructure at different depths below the surface of 35CrMo after USRP: (a1)–(a3) Inverse pole Figure (IPF); (b1)–(b3) Distribution of large- and small-angle grain boundaries;(c1)-(c3) KAM mapping.

Figure 3.

5.Microstructure at different depths below the surface of 35CrMo after USRP: (a1)–(a3) Inverse pole Figure (IPF); (b1)–(b3) Distribution of large- and small-angle grain boundaries;(c1)-(c3) KAM mapping.

Figure 3.5(b) presents the grain boundary distribution characteristics in the specimen's surface layer, where low-angle grain boundaries are marked in red and high-angle grain boundaries in black. As illustrated, the population density of LAGBs progressively decreases with increasing depth within the plastically deformed zone.

Figure 3.5(c) further displays the kernel average misorientation (KAM) mapping of the cross-section, revealing that the geometrically necessary dislocation (GND) density follows a similar depth-dependent trend as LAGBs. This phenomenon is attributed to the cumulative plastic strain effect induced by USRP, wherein shear-generated dislocations continuously accumulate at prior martensite lath boundaries. Such accumulation promotes the formation of both geometrically necessary boundaries (GNBs) and incidental dislocation boundaries (IDBs), which collectively accelerate the transformation of lath martensite into nanocrystalline grains[

15,

16]. Microstructural investigations demonstrate that within the top 30 μm severely deformed layer , the lath martensite undergoes fragmentation into equiaxed nanocrystals under high-energy impacts. In contrast, the subsurface region (∼100 μm depth) develops ultrafine grains with short lamellar structures. During this process, intensive dislocation annihilation occurs near the surface, forming subgrain boundaries that subsequently evolve into high-angle grain boundaries under high stress-strain conditions. According to the Hall-Petch relationship, the refined grain size contributes proportionally to the material's yield strength. This substantial grain refinement effectively enhances both strength and toughness, providing a theoretical foundation for 35CrMo steel strengthening.

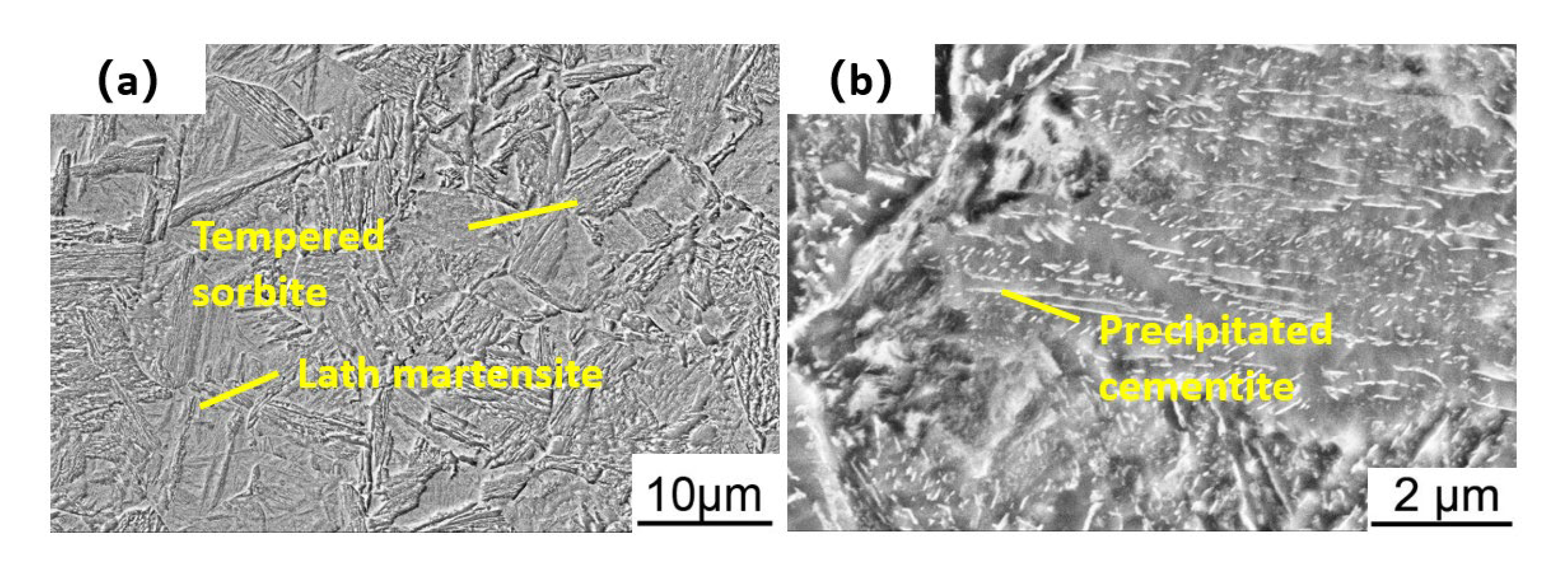

To gain deeper insight into the ultrafine grain formation mechanism under USRP, the USRP-0.50 MPa sample, which experienced the most severe deformation, was selected for detailed analysis of the near-surface microstructure before and after processing using transmission electron microscopy (TEM). As shown in

Figure 3.6, the primary microstructure of the untreated material consists of three constituents: undecomposed martensite, lamellar tempered sorbitte, and retained austenite. It is worth noting that the tempering temperature significantly influenced the microstructure, resulting in incomplete tempering. The resulting sorbitic structure clearly exhibits martensitic characteristics, accompanied by carbide aggregation, indicating insufficient diffusion during the tempering process.

Figure 3.

6.Microstructure of tempered 35CrMo steel: (a) Microstructure in the tempered state; (b) Precipitated cementite.

Figure 3.

6.Microstructure of tempered 35CrMo steel: (a) Microstructure in the tempered state; (b) Precipitated cementite.

Figure 3.6(a) shows that the microstructure of the untreated sample is predominantly martensitic. The matrix contains a high density of parallel lath martensite with clearly defined boundaries and a moderate dislocation density. Additionally, a small amount of thin-film retained austenite is present between the martensite laths.

TEM analysis indicates that the selected-area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern corresponding to

Figure 3.7(a) exhibits overlapping diffraction spots from both α (ferrite/martensite) and γ (austenite) phases, confirming that the crystallographic relationship between the retained austenite and the martensitic matrix is close to the Kurdjumov–Sachs (K–S) orientation relationship[

17]. Furthermore, a number of short rod- or bar-shaped carbides are observed within the material.

Table 3.1 presents the EDS point analysis results (elemental content in weight percentage) for the locations marked in

Figure 3.7. The atomic ratio of Fe to C, calculated based on their atomic weights (Fe/C ≈ 22/7), confirms that the precipitate is Fe₃C.

Figure 3.

7.Microstructure of the surface layer of 35CrMo in the turned state: (a) STEM; (b) Highmagnification morphology; (c) Matrix SAED; (d) Carbide and EDS.

Figure 3.

7.Microstructure of the surface layer of 35CrMo in the turned state: (a) STEM; (b) Highmagnification morphology; (c) Matrix SAED; (d) Carbide and EDS.

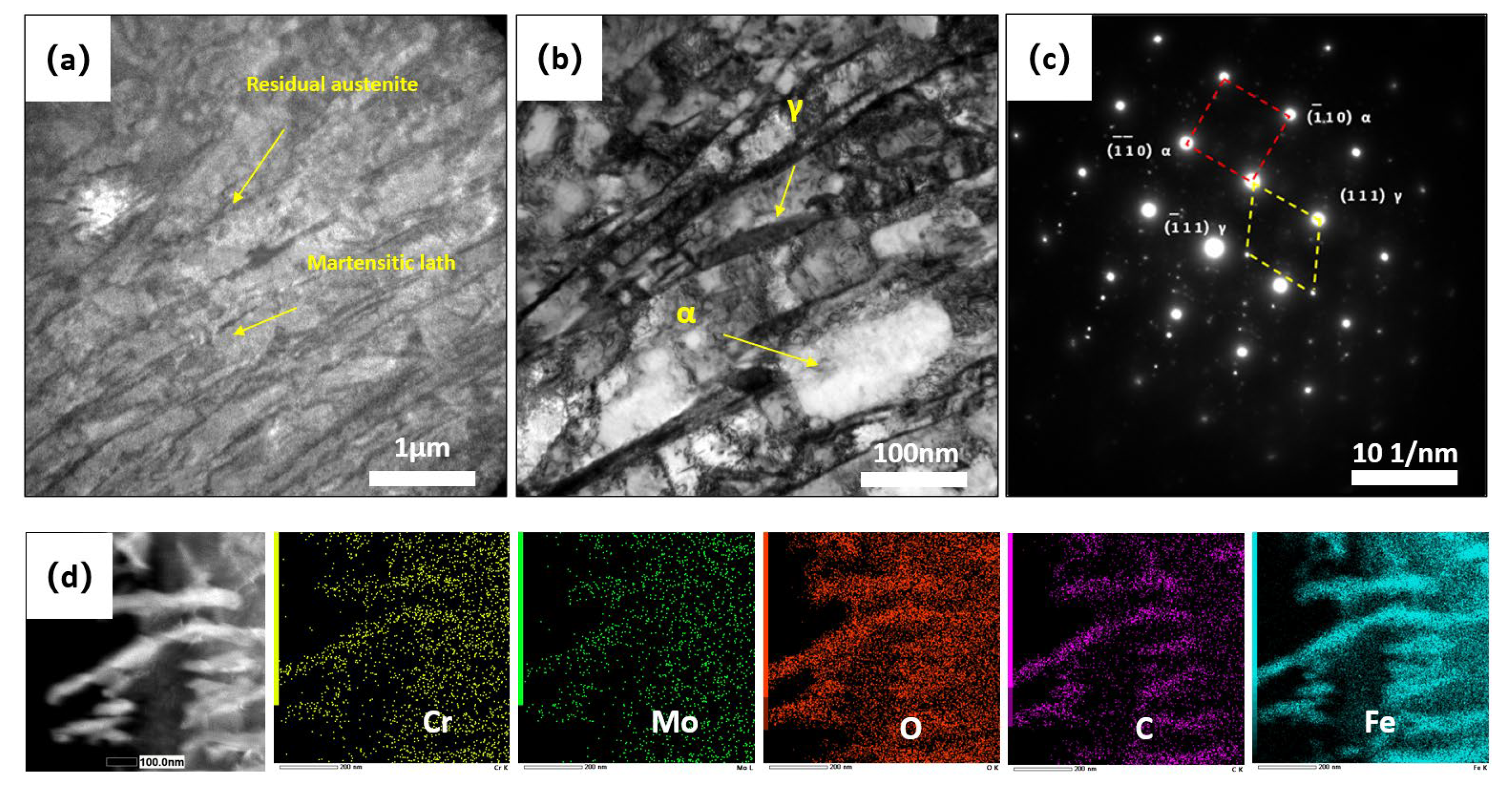

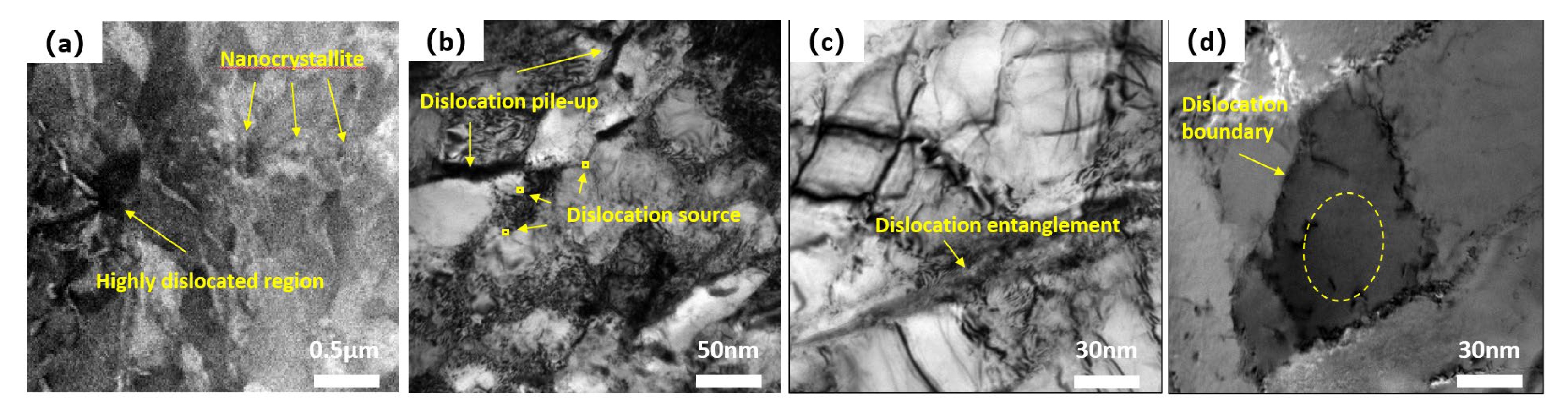

Following USRP, significant microstructural modifications are observed in the near-surface region of 35CrMo steel (

Figure 3.8). In contrast to the untreated microstructure characterized by lath martensite and thin-film retained austenite, the high-energy impacts and rolling effects introduced by USRP induce severe plastic deformation in the surface layer. The original martensite laths undergo elongation and fragmentation under shear stress, ultimately transforming into fine equiaxed nanocrystalline grains. Concurrently, dislocation density within grain boundaries increases substantially, leading to progressive blurring of lath boundaries.

As a body-centered cubic (BCC) material with high stacking fault energy, 35CrMo steel primarily accommodates plastic deformation through dislocation slip mechanisms. The USRP treatment facilitates microstructural reorganization through two dominant effects: formation of nanocrystalline grains via severe plastic deformation and significant enhancement of dislocation density

Figure 3.

8.Microstructure of the surface layer of 35CrMo in the USRP state: (a) STEM; (b) Highmagnification morphology; (c) Dislocation evolution; (d) Subcrystalline texture.

Figure 3.

8.Microstructure of the surface layer of 35CrMo in the USRP state: (a) STEM; (b) Highmagnification morphology; (c) Dislocation evolution; (d) Subcrystalline texture.

STEM was further employed to analyze dislocation behavior and substructure evolution within the severe plastic deformation region (

Figure 3.8).As evidenced in

Figure 3.8(b), the high-magnification microstructural analysis reveals significant grain refinement in the surface layer following ultrasonic surface rolling processing.

Figure 3.8(c) provides detailed insight into the dislocation dynamics, demonstrating that dislocation lines nucleate from multiple sites along martensite boundaries and propagate preferentially from high-density to low-density regions, exhibiting characteristic dynamic propagation behavior. The dislocations migrate through the martensite matrix until their motion is effectively hindered by either martensite lath boundaries or high-angle grain boundaries, resulting in the formation of distinct dislocation pile-up zones.

In regions of severe dislocation entanglement, the system undergoes energy minimization through two primary mechanisms: (i) dislocation annihilation and (ii) rearrangement into lower-energy configurations. This process facilitates the formation of well-defined dislocation cells and substructures. Progressive deformation leads to the accumulation and subsequent absorption of dislocations at low-angle subgrain boundaries, as quantitatively demonstrated in

Figure 3.8(d). This phenomenon is accompanied by a measurable reduction in dislocation density and a concomitant increase in misorientation angles of subgrain boundaries. The effect of impact and rolling forces generated by the USRP tool effectively induces the development of high-density dislocation tangles and substantial grain refinement to the nanoscale regime .These microstructural modifications collectively contribute to remarkable enhancements in surface performance characteristics like wear resistance and microhardness.

The present findings demonstrate that USRP treatment effectively optimizes the surface integrity of 35CrMo steel through controlled microstructural refinement and dislocation engineering, offering significant potential for industrial applications requiring superior mechanical performance.

3.4. Analysis of surface properties after rolling processes

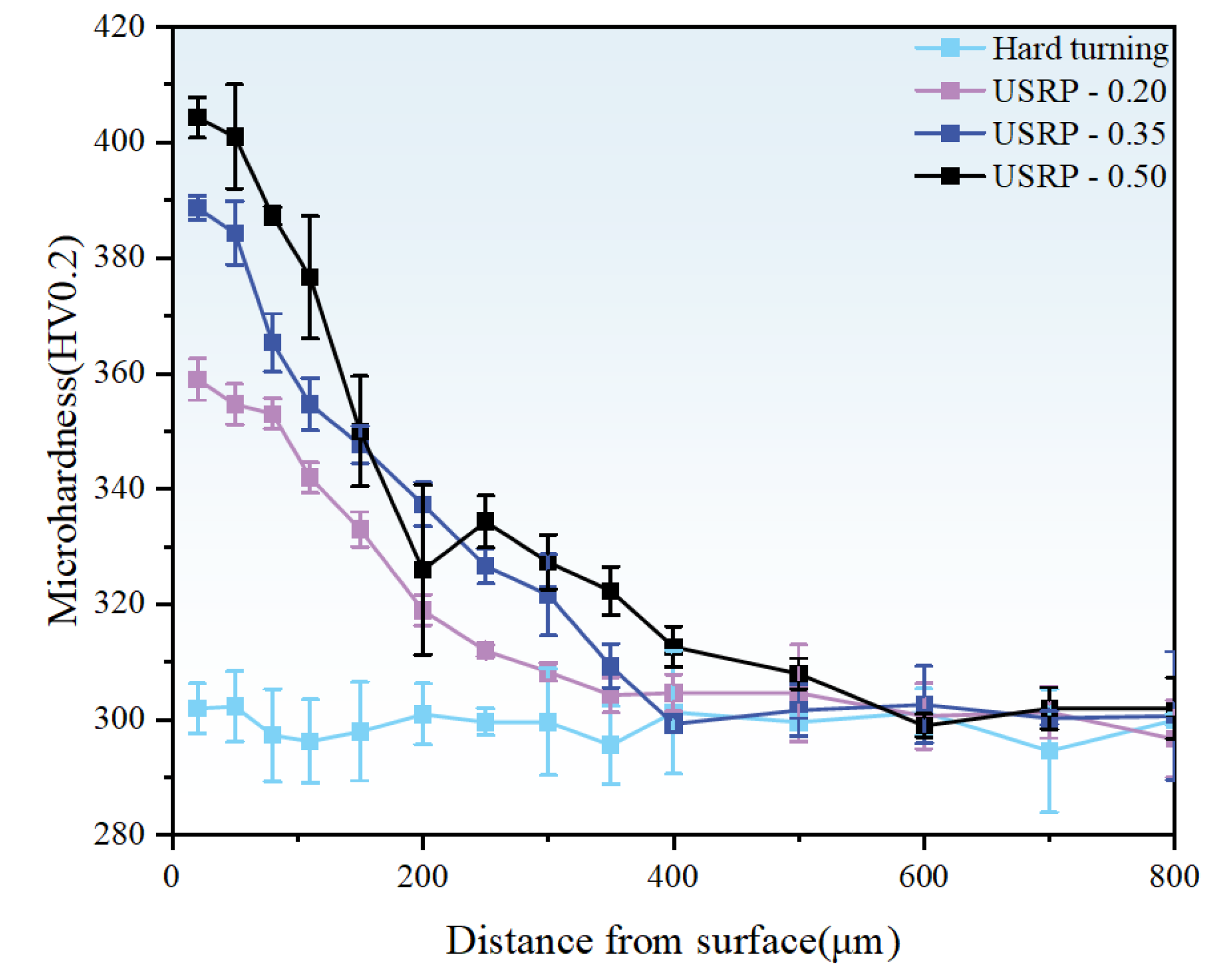

Systematic evaluation of the mechanically processed specimens revealed substantial improvements in surface mechanical properties. As illustrated in

Figure 3.9, microhardness measurements along the depth profile demonstrate distinct differences between conventionally turned specimens and those subjected to ultrasonic surface rolling processing under varying parameters. The baseline hardness of the turned specimens averaged 306 HV, showing only marginal surface hardening (typically <5% increase) attributable to conventional machining-induced work hardening effects.

In contrast, USRP-treated specimens exhibited remarkable surface strengthening, with the degree of enhancement showing clear pressure dependence. Three distinct processing pressures (0.20 MPa, 0.35 MPa, and 0.50 MPa) produced progressively greater surface hardening, achieving peak hardness values of 359 HV (+17.3%), 388 HV (+26.7%), and 405 HV (+32.3%) respectively. More importantly, the hardness profiles revealed characteristic gradient distributions, with values decreasing gradually from the surface to the unaffected bulk material. This gradient behavior became more pronounced with increasing rolling pressure, with the effective hardened layer depth extending to approximately 300 μm at the maximum applied pressure of 0.50 MPa.4. Discussion

Authors should discuss the results and how they can be interpreted from the perspective of previous studies and of the working hypotheses. The findings and their implications should be discussed in the broadest context possible. Future research directions may also be highlighted.

Figure 3.

9.Gradient hardness variation in the surface layer of 35CrMo before and after ultrasonic rolling.

Figure 3.

9.Gradient hardness variation in the surface layer of 35CrMo before and after ultrasonic rolling.

This phenomenon can be theoretically explained from the perspective of material micromechanisms: USRP effectively activates surface work hardening by promoting extensive dislocation multiplication within the material. Simultaneously, the process induces microstructural modifications including grain refinement, carbide refinement and deformation, all of which collectively contribute to the significant enhancement of microhardness[

18]. From a microstructural standpoint, the gradient variation of microhardness along the depth direction exhibits strong correlation with the graded distributions of grain size, grain boundary density, and dislocation concentration.Theoretical analysis suggests that the microhardness enhancement can be satisfactorily interpreted through Taylor's dislocation strengthening mechanism and the Hall-Petch effect[

19]. Furthermore, residual stress state represents another crucial factor influencing surface strengthening. Experimental investigations reveal that USRP treatment can induce considerable residual compressive stress with substantial penetration depth in the specimen surface layer, which aligns well with the findings reported by Carlsson and Larsson[

20,

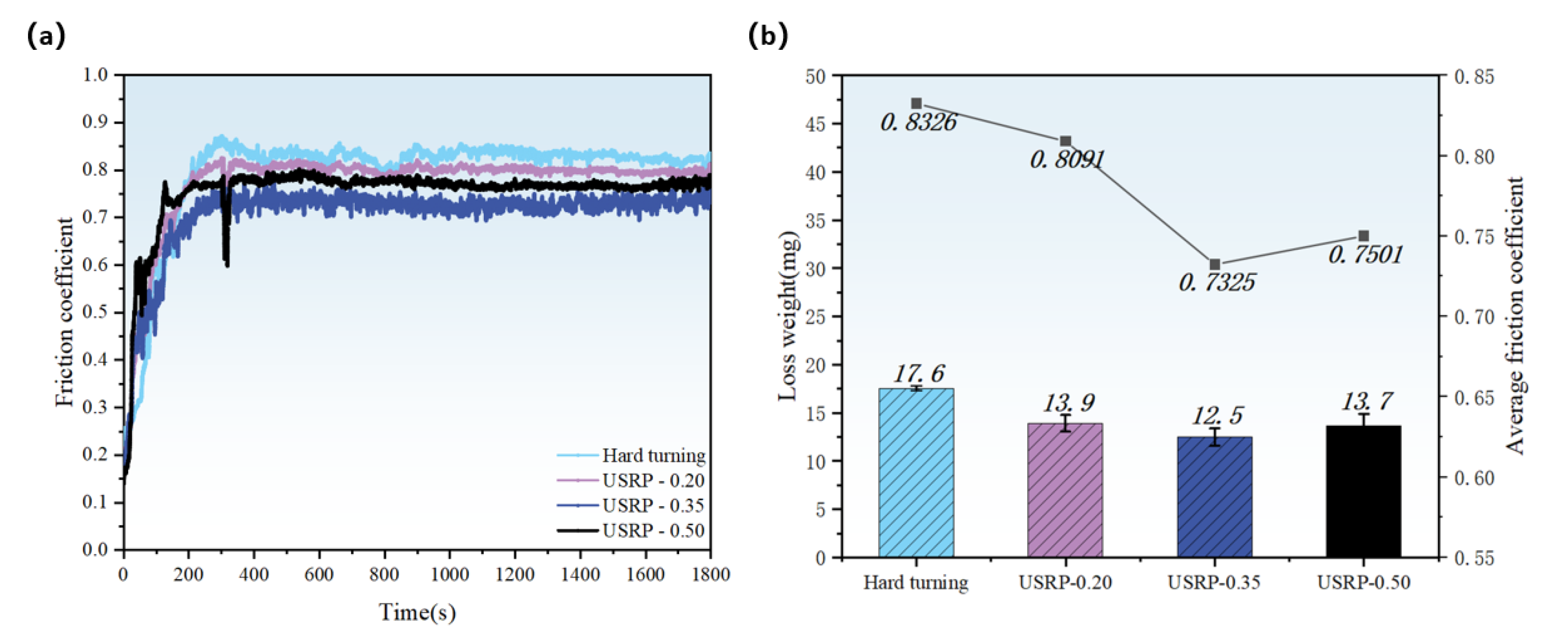

21]. Notably, under the present experimental conditions, USRP treatment not only remarkably improves surface hardness but also achieves an effective hardening depth that significantly exceeds the thickness of the gradient refined grain layer. This phenomenon may be attributed to the synergistic effects of high-density dislocations and residual stress fields induced by the process.The wear resistance of the metal surface also demonstrates substantial improvement after rolling treatment. The friction coefficient, serving as a direct indicator of material durability, typically correlates with wear severity and material loss rate - higher values generally correspond to more severe wear phenomena and faster material degradation. Experimental data (

Figure 3.10) reveal that during the initial stage of friction tests, significant fluctuations in friction coefficient occur due to the absence of a stable tribo-oxidation film on the workpiece surface. As relative motion proceeds between contact surfaces, oxidation reactions gradually take place and form a protective oxide layer. This oxide film effectively prevents direct contact between friction pairs, consequently reducing friction coefficient fluctuations and establishing a stable wear regime in the system.

Quantitative results from the friction and wear tests (

Figure 3.10) clearly demonstrate that USRP significantly improved the tribological properties of 35CrMo steel. The as-turned specimen exhibited the most substantial fluctuation in the coefficient of friction and the highest mass loss, indicating poor frictional stability and inferior wear resistance. In comparison, all USRP-treated specimens showed markedly enhanced frictional stability. The effectiveness of the treatment was found to be highly dependent on the applied static pressure. Specifically, the USRP-0.35 MPa sample displayed the smallest variation in friction coefficient and the lowest mass loss, representing a 28.9% reduction compared to the as-turned condition. The mass losses of the USRP-0.20 MPa and USRP-0.50 MPa samples were reduced by 21.1% and 22.2%, respectively. This behavior suggests that insufficient static pressure results in inadequate surface hardening, while excessively high pressure may introduce surface damage and microscopic defects, thereby increasing the risk of material degradation. More precisely, low static pressure leads to insufficient enhancement of surface hardness, whereas high static pressure can impair surface integrity through the formation of micro-defects, ultimately compromising wear performance.

Furthermore, under the three static pressure conditions investigated (listed in order of increasing magnitude), the USRP-treated specimens exhibited mass loss reductions of 21.1%, 28.9%, and 22.2% relative to the as-turned sample, unequivocally confirming the efficacy of USRP in improving the wear resistance of 35CrMo steel.

Figure 3.

10.Tribological parameters of 35CrMo before and after ultrasonic rolling: (a) Friction coefficient curve; (b) Wear volume and average friction coefficient.

Figure 3.

10.Tribological parameters of 35CrMo before and after ultrasonic rolling: (a) Friction coefficient curve; (b) Wear volume and average friction coefficient.

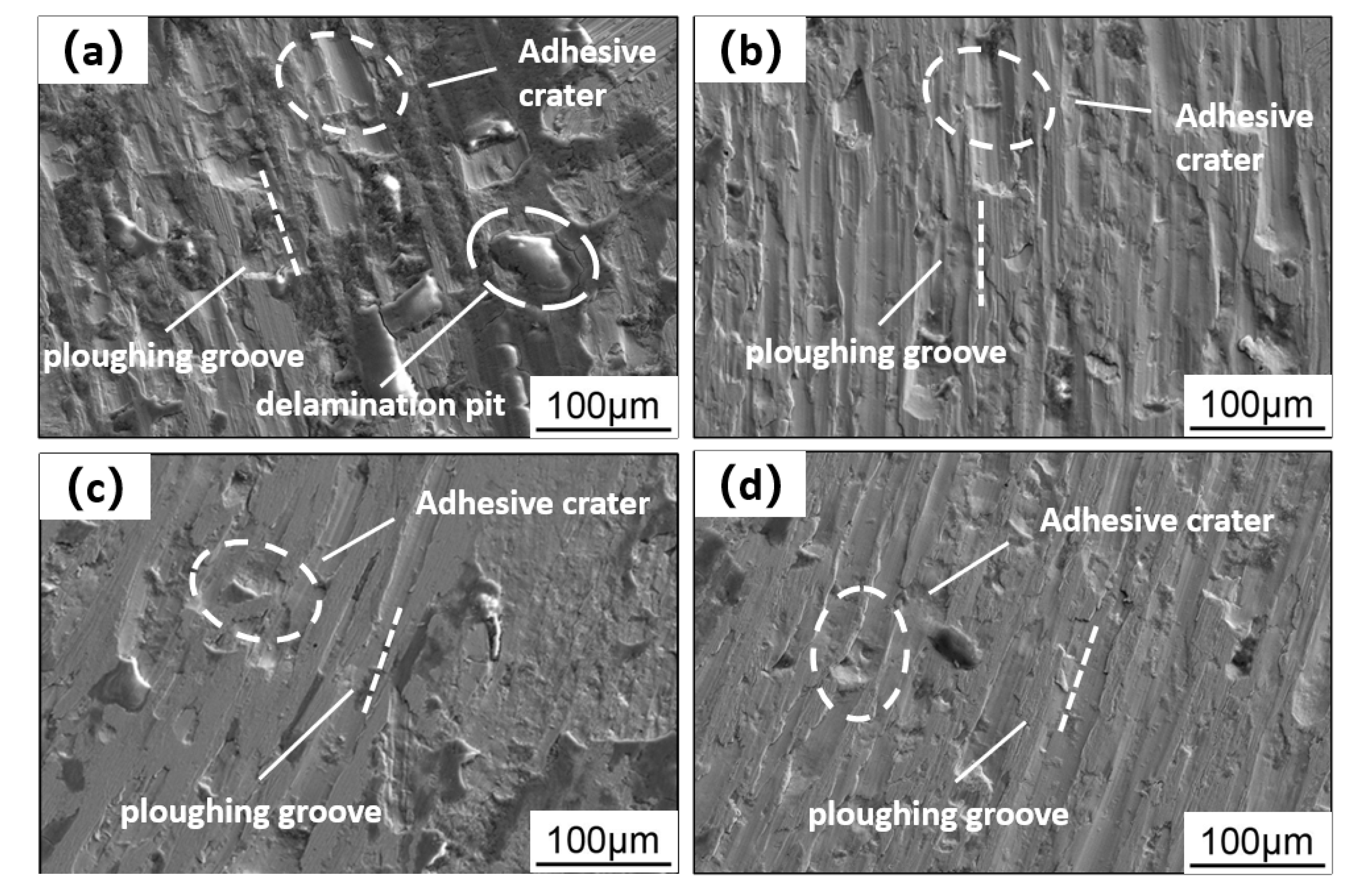

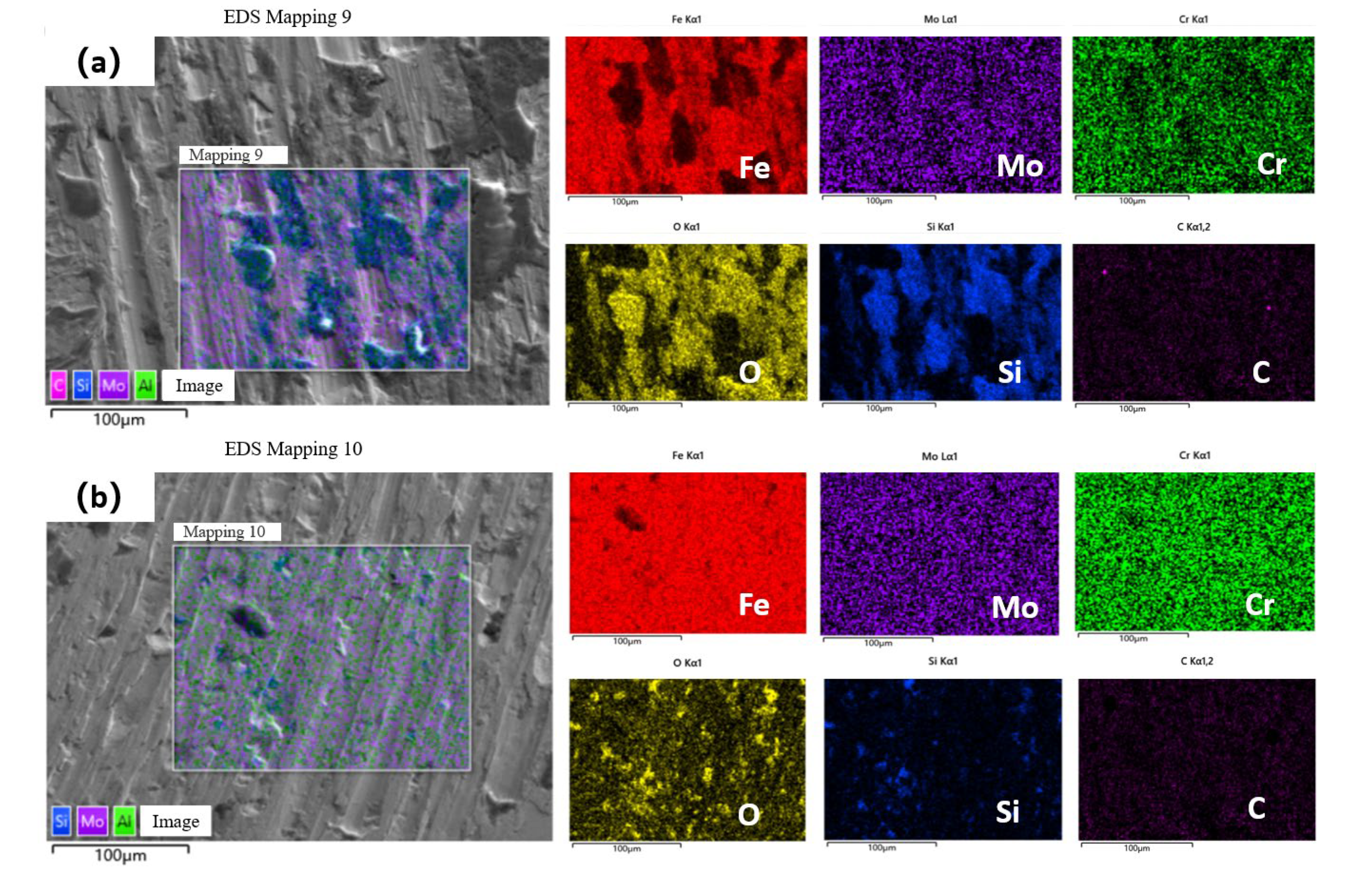

SEM examination of the worn surface morphology (

Figure 3.11), combined with elemental distribution analysis (

Figure 3.12), revealed the principal failure features and mechanisms of 35CrMo steel during the wear process. As shown in

Figure 3.11, all worn surfaces exhibited characteristic morphological patterns. Grooves formed by the penetration and plowing action of the hard SiC counterpart into the 35CrSteel surface during sliding, providing clear evidence of abrasive wear. Spalling areas accompanied by microcracks indicated that under repeated shear stress, localized stresses exceeding the fatigue strength of the material surface initiated crack formation and propagation, ultimately leading to delamination wear. Adhesion pits resulting from local bonding at contact points with the counterpart and subsequent material tearing under shear stress were identified as characteristics of adhesive wear.

Additionally, elemental mapping analysis, particularly oxygen distribution as shown in

Figure 3.12, revealed regions of oxide enrichment on the worn surfaces. This confirms that wear debris generated during the friction process reacted with environmental oxygen, indicating the presence of oxidative wear mechanisms.

Figure 3.

11.Wear surface morphology of 35CrMo before and after ultrasonic rolling: (a) Hard turning; (b) USRP-0.20 MPa; (c) USRP-0.35 MPa; (d) USRP-0.50 Mpa.

Figure 3.

11.Wear surface morphology of 35CrMo before and after ultrasonic rolling: (a) Hard turning; (b) USRP-0.20 MPa; (c) USRP-0.35 MPa; (d) USRP-0.50 Mpa.

Figure 3.

12.Distribution of elements on the wear surface of 35CrMo before and after ultrasonic rolling: (a) Hard turning; (b) USRP-0.50 Mpa.

Figure 3.

12.Distribution of elements on the wear surface of 35CrMo before and after ultrasonic rolling: (a) Hard turning; (b) USRP-0.50 Mpa.

During the sliding wear tests, the hard SiC counterface established point contact with the 35CrMo surface, generating characteristic ploughing grooves through abrasive action. Simultaneously, the embedding and scratching of wear debris manifested as primary features of abrasive wear. When the tensile stress induced by the shearing friction pair exceeded the surface yield strength of the material, microcrack initiation occurred, subsequently leading to delamination wear. Furthermore, the frictional process caused softening and eventual detachment of wear debris, forming adhesive craters that indicate adhesive wear mechanisms. Notably, our observations revealed that partially retained wear debris underwent chemical reactions with atmospheric oxygen under repeated compression, resulting in oxidative wear. In summary, the predominant wear mechanisms observed in 35CrMo specimens comprise abrasive wear, delamination wear, adhesive wear, and oxidative wear. Comparative analysis of wear morphologies before and after USRP treatment reveals substantial mitigation of all wear modes, manifested by three key improvements: (i) reduced ploughing groove depth, (ii) diminished adhesive crater volume, and (iii) decreased delamination frequency. Elemental distribution analysis (

Figure 3.12) further confirms effective suppression of oxidative wear following USRP treatment. Notably, the wear resistance enhancement exhibits significant process parameter dependence, with USRP-0.35 demonstrating optimal performance. This superiority primarily stems from optimized surface characteristics, particularly enhanced hardness and improved surface finish, which collectively inhibit multiple wear mechanisms.

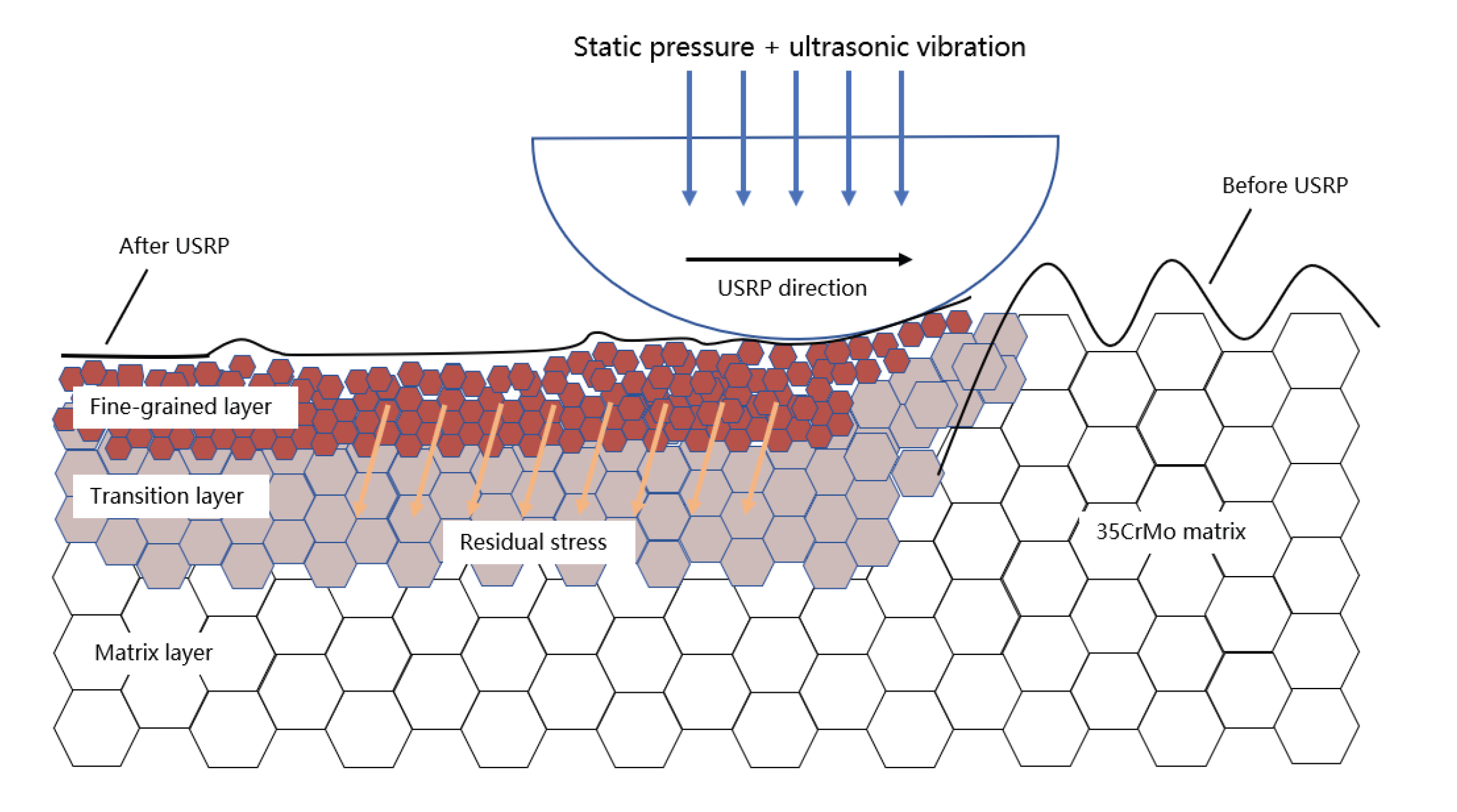

Figure 3.

13.Mechanism of surface USRP gradient structure modification in 35CrMo.

Figure 3.

13.Mechanism of surface USRP gradient structure modification in 35CrMo.

Figure 3.13 illustrates the underlying mechanisms by which USRP enhances the wear resistance of 35CrMo steel. As previously discussed, the severe plastic deformation induced by USRP promotes substantial grain refinement, leading to a marked increase in surface microhardness. This gradient-distributed hardened layer significantly improves the workpiece's wear resistance. Moreover, grain refinement increases the density of grain boundaries, which effectively restricts intergranular slip and reduces frictional resistance, thereby enhancing the material's anti-friction properties.

Beyond grain refinement, the introduction of residual compressive stress plays a pivotal role in wear performance enhancement. Under USRP, surface grains are subjected to compressive stress; when the workpiece experiences tangential friction, the grains undergo tensile deformation, partially releasing the residual compressive stress. This stress relaxation counteracts external frictional forces, reducing the actual load borne by the grains and improving anti-friction performance. Additionally, residual compressive stress reduces the volume and intergranular spacing of surface grains. This microstructural modification strengthens the material's resistance to micro-cutting, representing a key factor in wear resistance improvement.

The present findings demonstrate that USRP significantly improves tribological performance through three principal mechanisms: (i) microstructural refinement of surface grains, (ii) development of gradient hardness distributions, and (iii) generation of beneficial residual compressive stress fields, which collectively enhance both wear resistance and anti-friction characteristics.