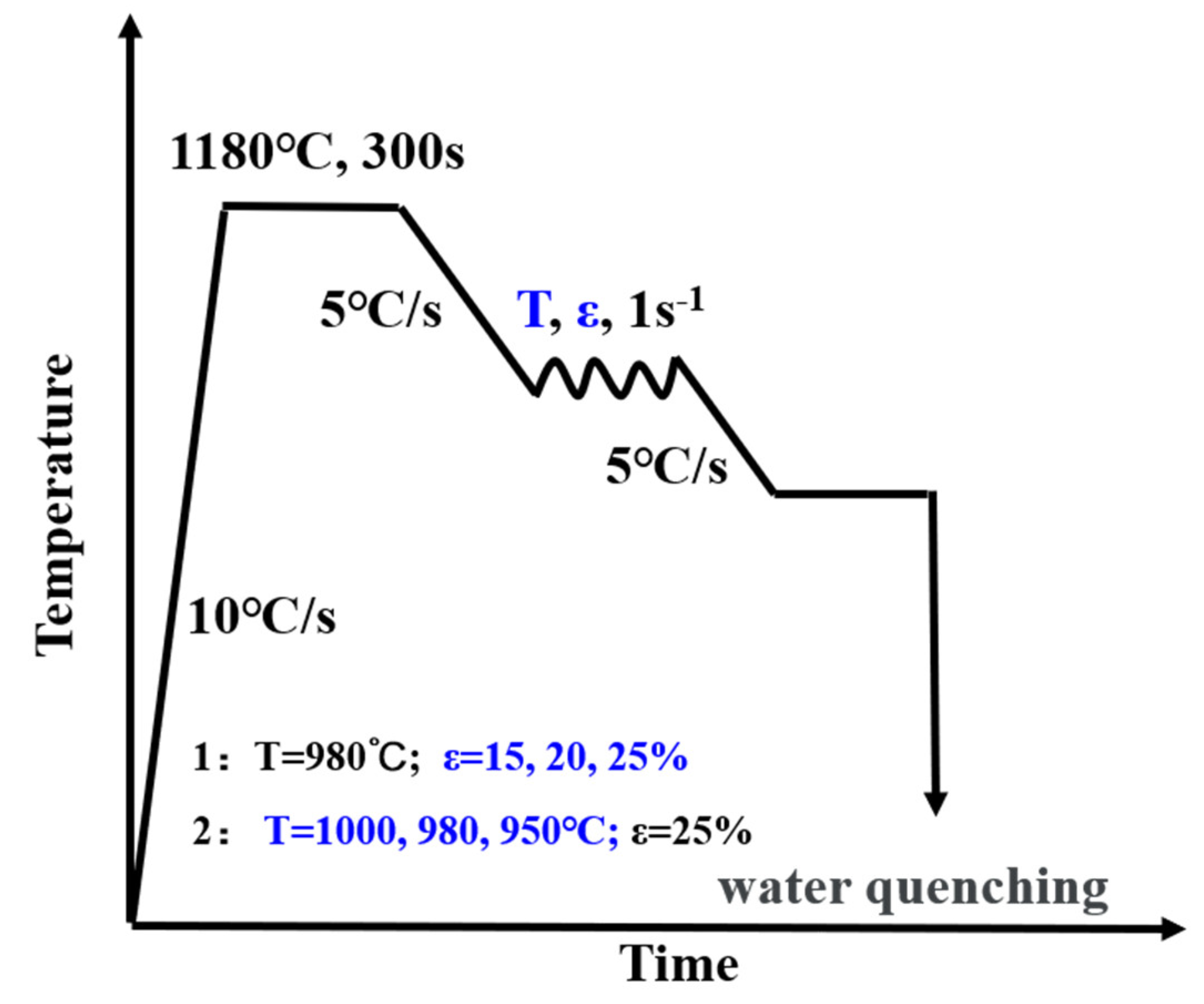

4.1. Thermodynamic Calculations for Experimental Steels

First, Thermo-Calc thermodynamic software was used to calculate the equilibriμm phase diagrams of the test steels and to analyze the relationship curves of the content of each phase and the alloying element components in the second phase with the change of temperature. The results of this calculation provide a theoretical basis for the prediction and calculation of the subsequent second phase precipitation behavior, and also provide an important reference for the exploration of the second phase precipitation mechanism under different process conditions.

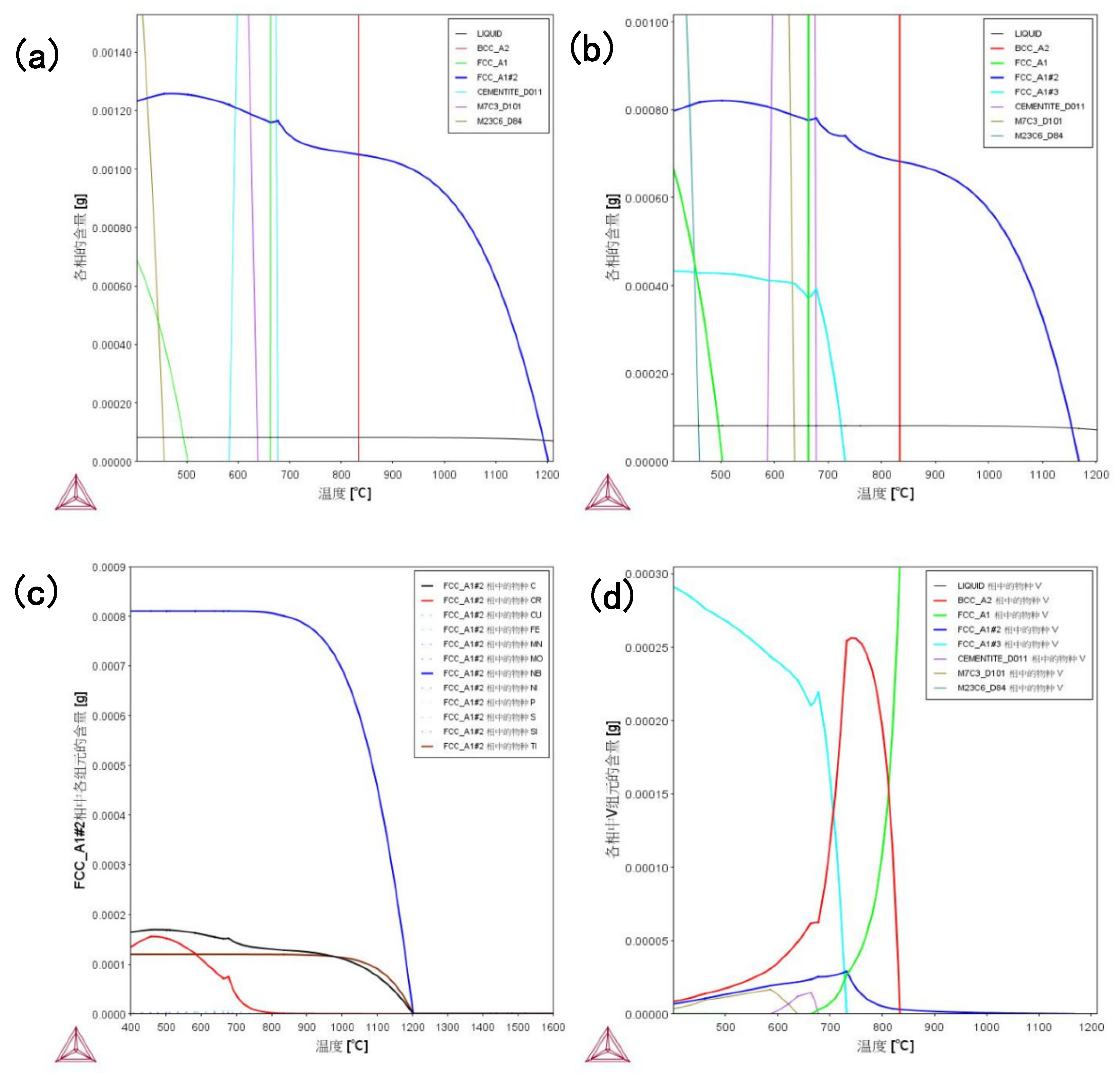

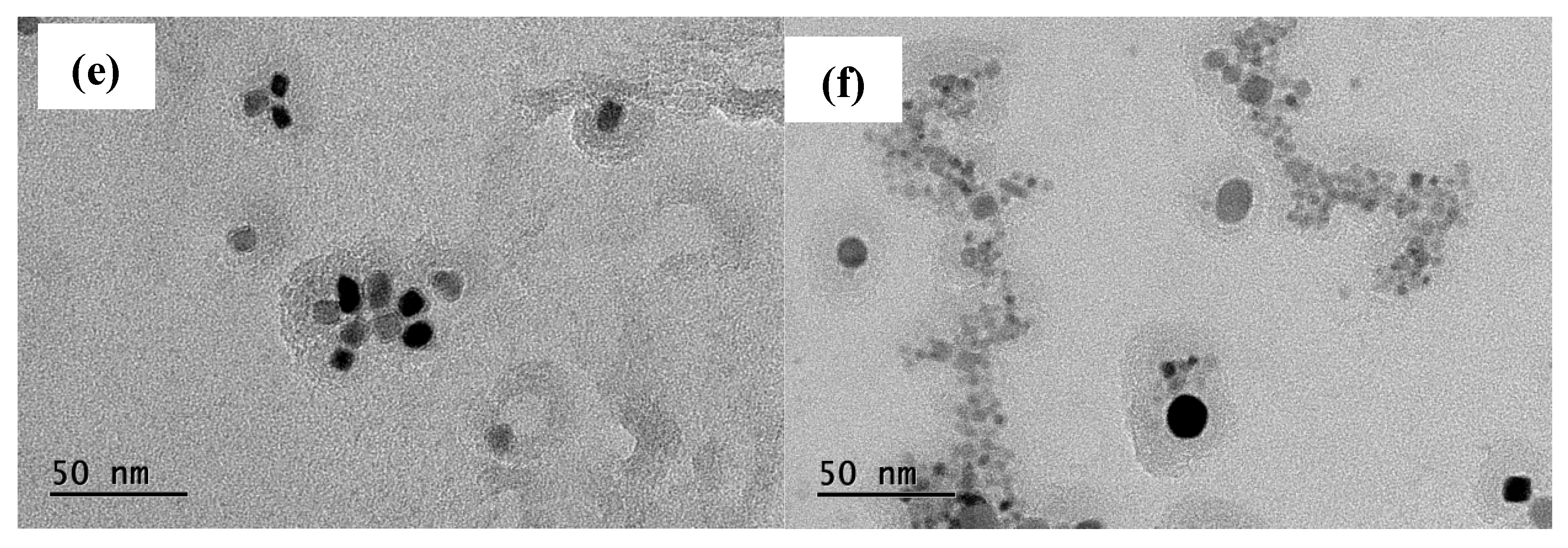

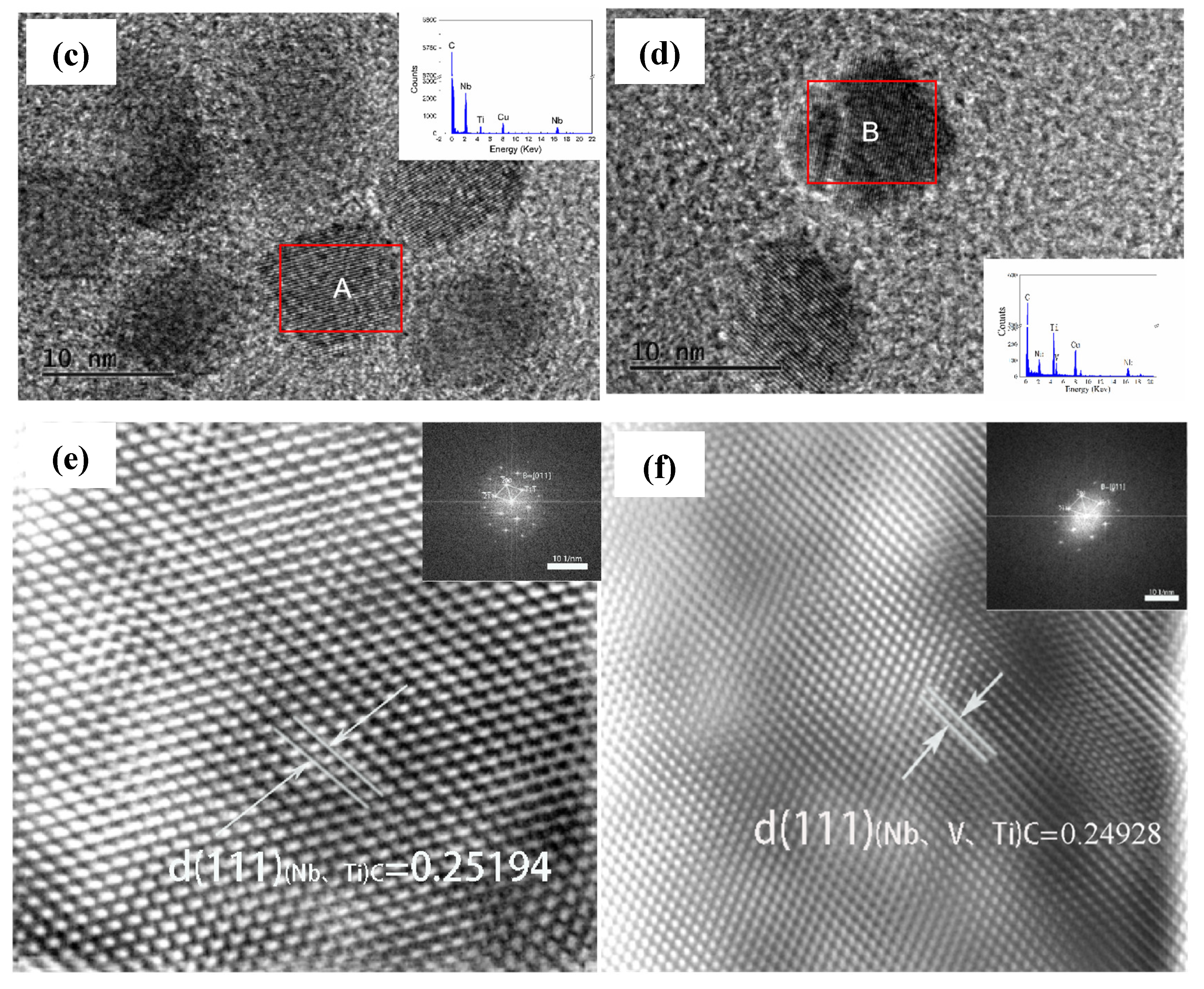

Figure 8(a) and (b) demonstrate the temperature dependence of each phase content in high Nb and Nb-V steels, respectively, where FCC_A1#2 represents the MC-type second phase. The results show that the MC second phase starts to precipitate below 1200 °C, with the fastest precipitation rate around 980 °C, and the trend of precipitation slows down below 900 °C. This is mainly due to the dissolution of MC phase in the high temperature stage, and the precipitation amount increases abruptly near 980°C due to the decrease of solubility, and then the precipitation rate slows down due to the decrease of precipitable elements.

Figure 8.

Thermodynamic calculations of experimental steels: Nb Steel (a, c) and Nb-V Steel (b, d).

Figure 8.

Thermodynamic calculations of experimental steels: Nb Steel (a, c) and Nb-V Steel (b, d).

Unlike high Nb steels, Nb-V steels also show FCC_A1#3 precipitation phase below 900°C, which is due to the addition of V element to change the precipitation behavior. the higher solubility of V in austenite makes it difficult to precipitate at high temperature, and instead, the second phase of nano-sized MC is precipitated in ferrite, which enhances the precipitation strengthening effect. This allows Nb-V steels to still have precipitation strengthening potential at the low temperature stage, which affects the final organization and properties.

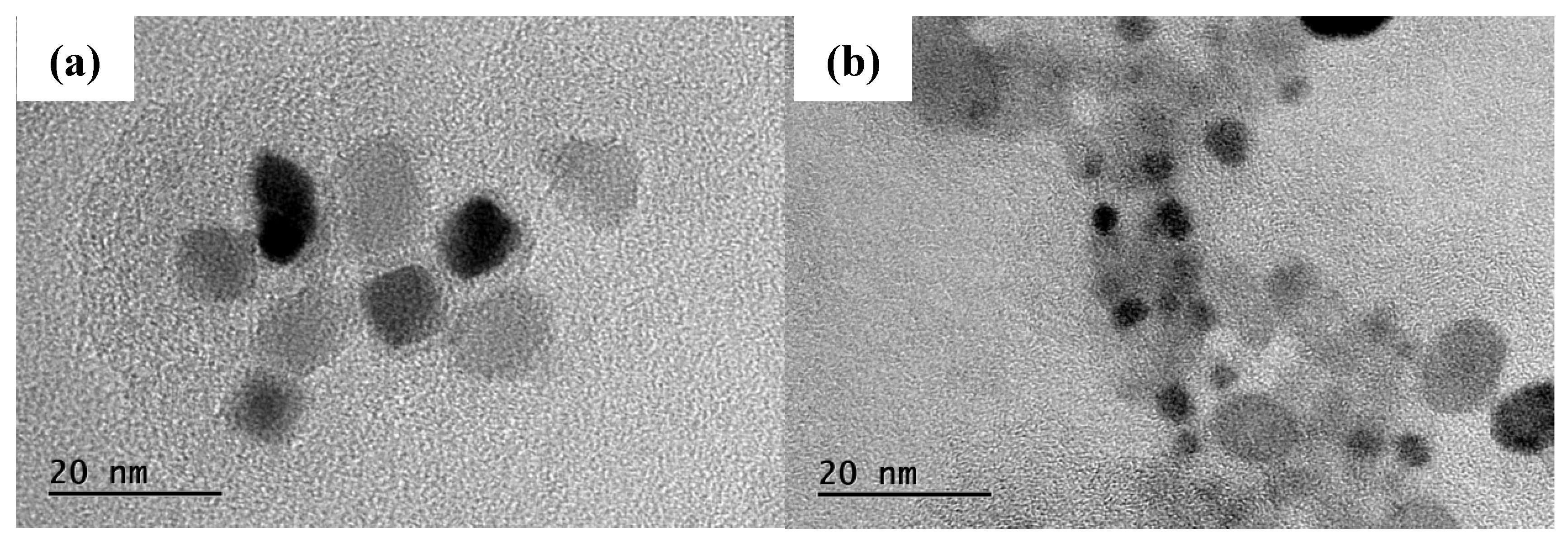

The elemental composition of the MC second phase is further analyzed in Figure 8(c), where the MC phase in high-Nb steels is mainly (Nb, Ti)C, which has high thermal stability and strengthening effect, whereas the precipitated phase of Nb-V steels may contain Nb, V, and Ti at the same time, which makes the precipitated phase finer and more uniform, and contributes to the enhancement of material strength and toughness. This suggests that the Nb-V alloying strategy can effectively optimize the precipitation behavior, which provides an important basis for tissue modulation and property enhancement.

Figure 8.

Thermodynamic calculations of two experimental steels: Nb Steel (a) and Nb-V Steel (b).

Figure 8.

Thermodynamic calculations of two experimental steels: Nb Steel (a) and Nb-V Steel (b).

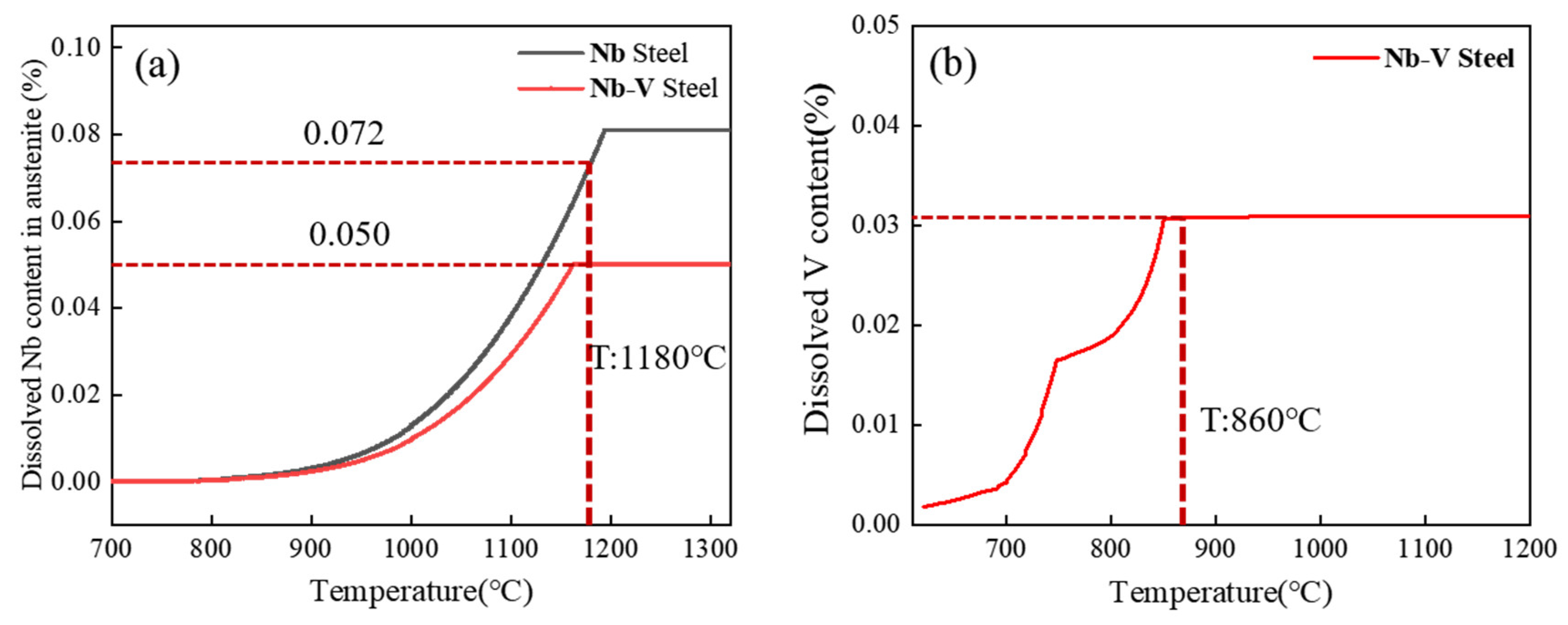

The solid solution behavior of Nb and V microalloying elements in the two kinds of test steels at different temperatures was calculated using Thermo-Calc thermodynamic software, and the results are shown in Figure 8.As can be seen in Figure 8(a), the solid solution Nb element content in Nb and Nb-V steels at 1180°C is 0.072% and 0.05%, respectively, which indicates that most of the Nb has been Nb solidly dissolved into the austenite, while the V element is completely solidly dissolved in the austenite (

Figure 3(b)).

This solid solution behavior corresponds to the results of the austenite original grain size (

Figure 4(b)), indicating that the microalloying elements solidly dissolved in the austenite at elevated temperatures also play a significant role in inhibiting grain growth. Specifically, the precipitated phase of Nb effectively hinders the austenite grain growth by pinning the grain boundaries, whereas V has a weaker inhibitory effect on grain growth at this temperature due to its complete solid solution. Therefore, the presence of precipitated phases is a key factor in controlling the austenite grain size.

4.2. Dynamics Calculations for Experimental Steels

Microalloying elements in test steels exist mainly in two forms: one part is solidly dissolved in the iron matrix and the other part precipitates as a second phase. Under specific conditions, the two forms can reach equilibriμm and the corresponding microalloying element contents are relatively stable. Therefore, in this study, the precipitation behavior of the second phase of composite microalloying is theoretically calculated and based on the following assμmptions:

(1) All Ti elements in the steel are precipitated in the form of large TiN particles, and the influence of N elements on the precipitation of (Nb,V)C is not considered;

(2) NbC and VC have NaCl structure, can be completely solid solution, and meet the ideal stoichiometric ratio, forming a composite precipitation phase with the chemical formula of NbxV1-xC;

(3) (Nb,V)C nucleates preferentially on the dislocation line and its nucleation rate decays rapidly to zero;

(4) The morphology of the precipitated MC phase in austenite is approximately spherical, and the effect of elastic strain energy is not taken into account when calculating the free energy change of individual nuclei;

(5) Since the test steels were treated with microtitaniμm, the effect of Ti on the composite precipitation is negligible.

In addition, the nucleation of microalloyed carbides is usually significantly nonuniform, and the precipitated phases preferentially nucleate at grain boundaries because the critical work of nucleation at grain boundaries in the matrix is lower than that at dislocation lines. However, limited by the nucleation location at the grain boundaries, precipitation occurs mainly at the dislocation line when the solute elements near the grain boundaries are depleted. Therefore, this study focuses on the second phase precipitation behavior of the test steel under non-uniform nucleation conditions [

34,

35] (nucleation rate decaying to zero).

It is assμmed that the initial contents of the elements Nb, V and C in the test steel are the contents of Nb, V and C, respectively. The solid solution of each element in the austenite of the test steel is expressed as [Nb], [V] and [C]. can be obtained based on the previous assμmptions:

The corresponding solid solubility product equation for (Nb, V)C in austenite can be derived as:

By substituting the values of [Nb], [V] and [C] at different calorimetric temperatures, the equilibriμm solid solution and equilibriμm coefficients x for each element can be obtained by solving the equilibriμm solid solution and equilibriμm coefficients x for each element at the determined temperatures (x is taken to be 1 for Nb steels, and x is taken to be 0 for V steels).

Table 2.

Variation of the value of X with temperature.

Table 2.

Variation of the value of X with temperature.

| Temperature (℃) |

940 |

960 |

980 |

1000 |

1020 |

1040 |

1060 |

1080 |

1100 |

| X |

0.886 |

0.891 |

0.895 |

0.900 |

0.903 |

0.909 |

0.916 |

0.927 |

0.933 |

When the homogenization temperature is lower than 1279°C, then the free energy of phase transition for precipitation of (Nb, V)C at different precipitation temperatures T is

If x does not vary much in the above temperature range, the calculation can only be made using the approximate value of x. Moreover, the specific interfacial energies of niobiμm carbide and vanadiμm carbide at each temperature are given:

The specific interfacial energy between niobiμm-vanadiμm carbide and austenite can be obtained using linear interpolation for different values of x:

At this point, if the variation of x in the temperature range under consideration is not large, x is essentially constant and has a relatively small impact error on the specific interfacial energy estimation, with a relative change in specific interfacial energy of only 0.1% when the x value changes by 0.03. Therefore, the approximate value of x can be used to calculate the specific interfacial energy.

For a dislocation line nucleus, the free energy change to form a spherical nucleus embryo of diameter

:

where C is a constant independent of d. or

and

,G is the shear elastic modulus, v is the Poisson’s ratio, and b is the dislocation Bergs vector. When

,The critical nucleation size of microalloyed carbides can be obtained as

:

critical form nuclear work

:

Volμme change law of precipitated phase with time change rule

Integrating over the time from 0 to t yields the kinetic equations for the case where the precipitated phase nucleates on the dislocation line and the nucleation rate shrinks to zero:

It follows that when (Nb, V)C nucleates on the dislocation line and decays rapidly to zero, n=1:

Substituting into Eq (14):

where t

0d is a temperature independent constant. Therefore, let, then we can get:

Table 3.

Lattice constants and linear expansion coefficients of NbC, VC at room temperature.

Table 3.

Lattice constants and linear expansion coefficients of NbC, VC at room temperature.

| Carbide |

Lattice constant / nm |

Linear expansion coefficient / K-1 |

| NbC |

0.4469 |

7.02×10-6

|

| VC |

0.4182 |

8.29×10-6

|

Table 4.

Activation energies of Ti, V and Mo in g and a matrix [

26].

Table 4.

Activation energies of Ti, V and Mo in g and a matrix [

26].

| Element |

Qg / k J |

Qa / kJ |

| Nb |

267 |

252 |

| V |

264 |

241 |

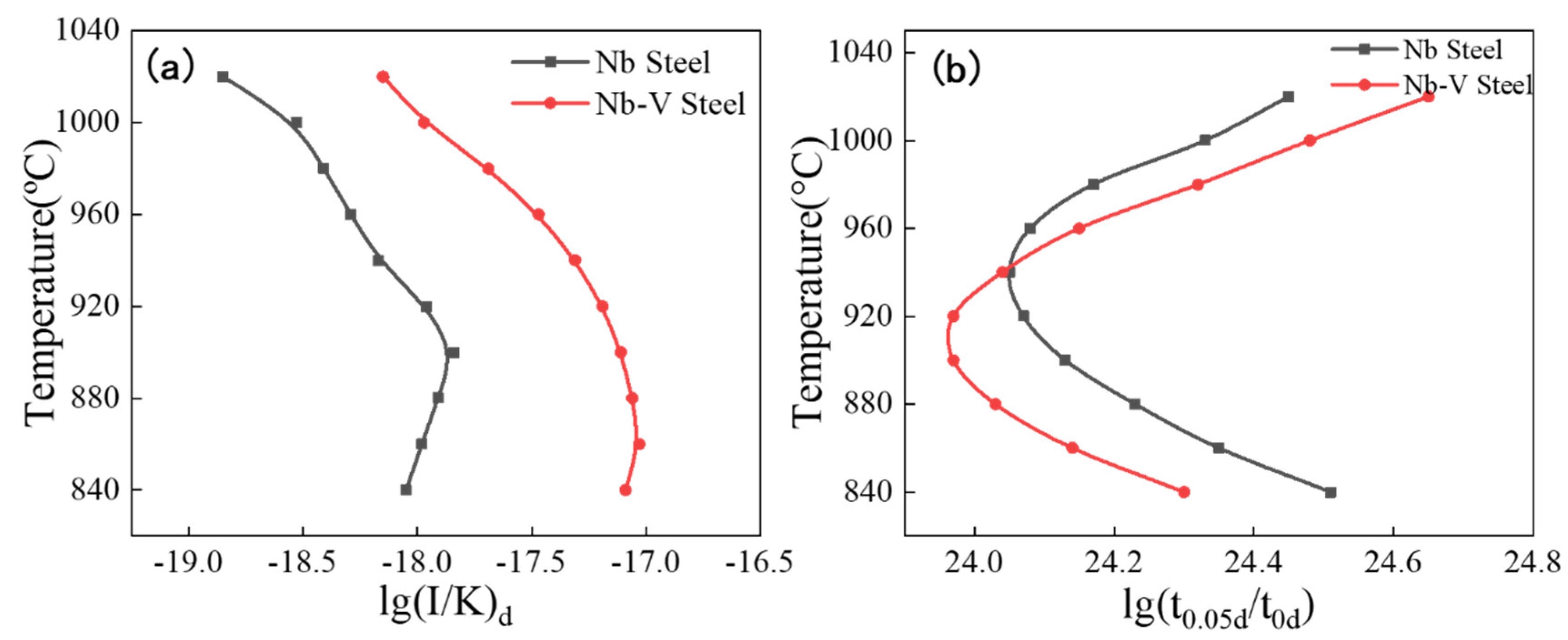

The PTT and NrT curves for precipitation of (Nb,V)C in austenite were calculated from

Table 5 and are shown in

Figure 9.

Figure 9(a) shows the NrT curves of precipitation in austenite for Nb and Nb-V steels with nose point temperatures of 1000°C and 960°C, respectively, and the NrT curve of Nb-V steel is always located in the upper right corner of Nb steel, indicating that the nucleation rate of Nb-V steel is always higher than that of Nb steel. This indicates that the addition of V element promotes the second phase nucleation in austenite of Nb-V steel and accelerates the kinetic process of precipitation.

Figure 9(b) shows the PTT curves of precipitation in austenite for the experimental steels with nose point temperatures of 940°C and 920°C, respectively, with small differences, but there is an obvious crossover in the PTT curves. This crossover phenomenon is mainly controlled by the combination of two independent factors: at higher temperatures, the chemical drive plays a dominant role, and the experimental steel with higher Nb content has a greater chemical drive at this time due to the fact that the V element is basically solidly dissolved in the austenite [

36]; whereas at lower temperatures, the atomic diffusion dominates the precipitation process, and the Nb and V elements are precipitated at the same time, and promote each other [

37]. In the mediμm temperature interval, the combined effect of the two mechanisms reaches a maximμm, forming a typical C-shaped PTT curve. In addition, the PTT curves of Nb-V steels are shifted to the lower left compared to Nb steels, indicating that the time required for precipitation is shorter at the nose point temperature. This result further demonstrates the promoting effect of element V on the precipitation of Nb in austenite, which leads to a faster precipitation rate of the second phase in Nb-V steels and thus improves the precipitation strengthening effect.

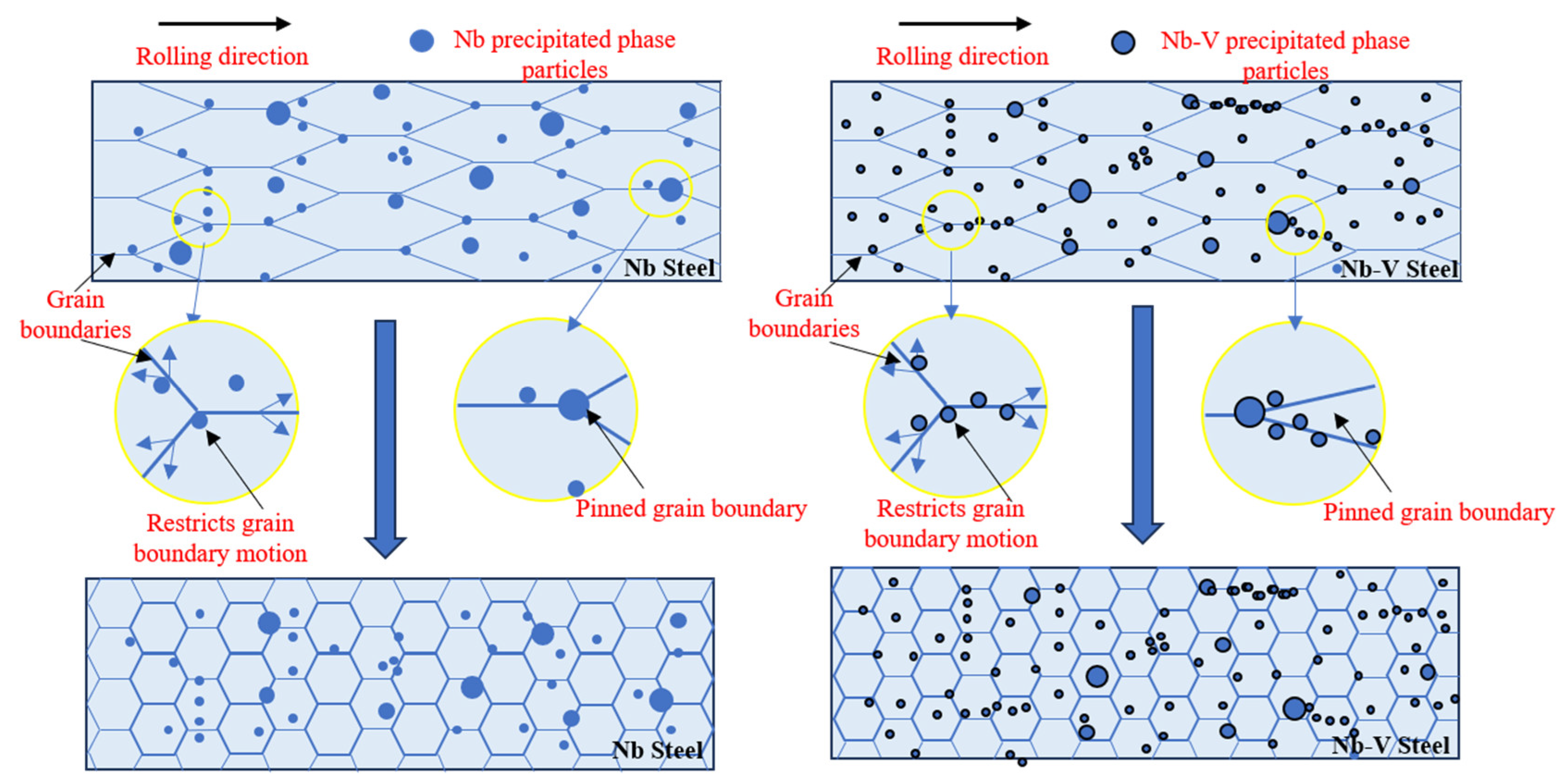

The experimental results show that there is a significant difference between the austenite recrystallization behavior of Nb and Nb-V steels under different deformation conditions. As can be seen from

Figure 4, with the increase of deformation, the austenite of the two experimental steels undergoes recrystallization, and the grains are all significantly refined, but the refinement effect of Nb-V steel is superior, which is mainly attributed to the inhibition effect of grain boundary migration by the precipitation of more second phase in Nb-V steel. Combined with the precipitation phase statistics in

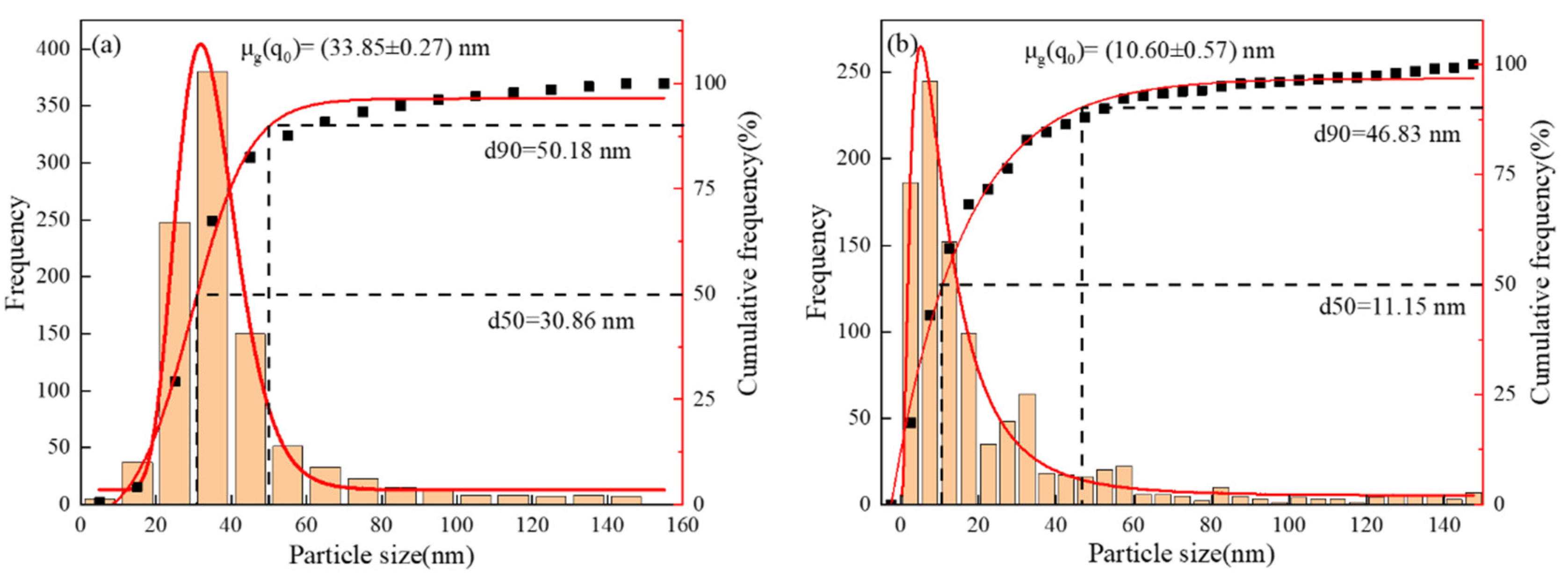

Figure 6, it can be seen that the precipitation phase particle size of Nb-V steel is smaller and more nμmerous, especially the proportion of nanoscale precipitation phases below 100 nm is significantly higher than that of Nb steel, and these diffusely precipitated particles play a stronger pinning effect on the austenite grains, which can effectively impede the growth of the austenite grains and improve their recrystallization refinement degree.

In addition, from the thermodynamic calculations (

Figure 7) and kinetic analysis (

Figure 9), it can be seen that in the austenite phase region, the Nb element precipitates in the form of MC phase, while the V element is mainly in solid solution at high temperatures, and then gradually precipitates at low temperatures and forms a composite precipitation phase with NbC (Nb,V)C. The results of the thermodynamic calculations show that the precipitation temperature of the MC phase is lower, the rate of precipitation is faster, and the nucleation rate of it is higher than that of the Nb-V steel (NrT curve). (NrT curve) is higher than that of Nb steel, indicating that the addition of V element effectively promotes the precipitation kinetic process. The left shift of the PTT curve indicates that the precipitation time of Nb-V steels is shorter, which is conducive to the formation of more diffuse precipitated phases during the deformation process and further enhances the effect of austenite grain refinement.

Figure 10.

Schematic diagram of the second phase granular precipitation pinned grain boundaries.

Figure 10.

Schematic diagram of the second phase granular precipitation pinned grain boundaries.

In conclusion, there is an obvious interaction between austenite recrystallization and the precipitation of the second phase, and the precipitated (Nb,V)C phase in Nb-V steels is able to nail the austenite grain boundaries more effectively at high temperatures to inhibit its growth, while further precipitating fine particles at lower temperatures to enhance the restraining effect on the austenite grains. This synergistic effect of precipitation and recrystallization enables the formation of finer and more homogeneous austenite grains in Nb-V steels during hot deformation, which provides an important basis for the subsequent organization and property optimization.