1. Introduction

3D printing, as a method of additive manufacturing, has garnered significant interes due to its applications in numerous industries [

1,

2,

3]. This technology can be found in various fields, including the aerospace, mechanical, and automotive industries, as well as in construction and many areas of medicine. For instance, it is used to print preoperative models, prosthetics, implants, and bone tissues. 3D printing achieves results that are challenging to replicate using traditional manufacturing methods, which undoubtedly enhances the effectiveness of treatment [

2,

4].

FDM (Fused Deposition Modeling) stands out for its simplicity and accessibility. However, despite its numerous advantages, print defects are common, often resulting from improperly selected parameters. The advancement of artificial intelligence has facilitated the optimization of production processes through data analysis and pattern recognition [

5,

6]. The application of artificial intelligence in 3D printing opens new perspectives in quality control, enabling more precise detection of defects and enhancing the overall efficiency of production processes [

7,

8,

9].

Nowadays, artificial intelligence serves as a cornerstone of technology in many aspects of life, with its applications including, among others, speech recognition. [

10], image processing [

11], natural language processing [

12], intelligent robots, autonomous vehicles, and healthcare systems [

13,

14]. Most existing AI systems have narrowly dedicated purposes for a defined range of tasks and, in this context, are referred to as narrow intelligence (ANI) [

15]. It selects routes in navigation systems after entering a destination address, maps applications on smartphones, and provides a list of optimized solutions for route planning that minimize travel time or costs [

16]. It is also responsible for collecting information about internet users and precisely targeting advertisements tailored to them. Thanks to real-time bioinformatics analysis, new methods of personal identification can be introduced, enabling payment systems based on fingerprints or facial recognition technology [

15]. These methods have also become common for unlocking mobile phones. The applications are characterized by precise categorization and a minimal scope of frequently asked questions.

The author of the article “A Tool of Conversation: Chatbot” [

17] explains that the titular tool refers to a program designed to mimic intelligent text-based or spoken communication. Chatbots, relying on written forms of conversation, recognize user input and, through pattern matching, access information to provide predefined responses. [

18]. When artificial intelligence finds an answer in its available database after receiving user input, the user receives a response based on a predefined pattern [

19]. A chatbot is implemented using pattern matching, meaning it recognizes the sequence of a sentence, and the stored response pattern is adapted to the unique variables of the sentence. However, chatbots cannot process or respond to complex questions and are unable to perform complex tasks [

17,

20]. Vision systems for defect detection using artificial intelligence ensure accuracy, efficiency, effective identification of defects, and precise differentiation between defective and non-defective elements. The authors of the article “Identifying an Image Classification Model for Welding Defects Detection” [

21] discussed three different artificial neural network (ANN) architectures, each with unique features and distinct applications. Analysis revealed that the EfficientNetB-b7 model, while demonstrating high performance in terms of neural network training time (3 minutes and 15 seconds), had the poorest accuracy among the three tested models, making 20 defects during testing. The second-best model was MobileNet-v2, which made 18 defects with a training time of 20 minutes and 43 seconds. The most accurate model, YOLOv7, made the fewest defects 13 in total while requiring 41 minutes for training. Additionally, it left 7 cases unanswered, indicating that when uncertain, it refrains from guessing the correct answer [

21].

An AI chatbot is a computer program that uses artificial intelligence technology, enabling it to understand commands and provide responses in real time [

22]. Application developers program chatbots in a way that closely resembles human-sent messages, making recipients feel that the chatbot’s responses are genuine and reliable, as the delivery of information is as user-friendly as possible [

23]. Chatbots are a relatively new technology, and their databases may contain inaccurate information, so it is important to remember that they can make defects [

20]. Additionally, chatbots are incapable of feeling emotions or exhibiting empathy; this is merely a deliberate design choice by application developers to engage users. Any message that appears to demonstrate empathy is a computer-generated response based on patterns learned by the chatbot [

24,

25].

The aim of this study is to determine whether the available technology (the research was conducted from September 2024) can accurately detect defects in 3D printing and correctly provide printing parameters to rectify defects in the analyzed samples of printed objects. It was examined whether chatbots are capable of accurately recognizing the content of g-code files and whether they have the ability to modify them. Additionally, the study analyzed whether AI can independently generate a g-code file containing a model ready for printing. study focuses on evaluating the usefulness of AI chatbots in monitoring and optimizing 3D printing processes, which could lead to improved production quality in the future.

2. Research Methodology

The 3D models were printed using the FlashForge Adventurer 4 printer. The model files were first exported in STL format, converted to g-code using FlashPrint 5 software, and then printed. Inventor Professional 2024 was used to design the models, the FlashPrint 5 software was used to modify the printing process parameters to intentionally introduce defects in the 3D prints. Model designs were exported to STL format using the initial software and then, after modifications, converted to g-code in FlashPrint 5. The models were then printed on the 3D printer.

The AI models, in the form of publicly available chatbots, were required to meet the criteria of being able to process files and images. The study evaluated three chatbots with such capabilities. These were:

Gemini

Gemini Advanced

Chat GPT-4o

The process parameters for each defect were selected individually. The basic parameters, included in every conversation with the chatbot, were as follows:

Nozzle size – 0.4 [mm]

Material type – PLA lub ABS

Filament diameter – 1.75 [mm]

Extruder temperature – from 200° to 220°C for PLA and from 220 to 250°C for ABS

Platform temperature – 20°- 60°C for PLA and 90° - 110°C for ABS

Layer height –0.2 [mm]

First layer height – 0.3 [mm]

Base print speed – 50 [mm/s]

Number of perimeters – usually 2 – 3 perimeters

Top solid layers – usally 4 layers

Bottom solid layers – usally 3 layers

Infill density –20%

Raft inclusion – usually yes

Cooling fan control – enabled (after printing the first layer)

The study focused on identifying issues in 3D prints using the FDM method. To analyze defects and improve print quality, five questions were posed to the chatbots.

1. What do you see in the photo~

2. What type of technology was used~

3.Name the defect in the 3D print using the FDM method visible in the photo.

4. Specify the print parameters that need to be adjusted to improve the print quality.

5. The following parameters were used for the print: [For each 3D printing defect, modified print settings differing from those for a correct print were provided. The input values, correct settings, and corrections suggested by the chatbot are presented in Appendix 1.] Can you provide specific print values to achieve a correct 3D model print~

In the second experiment, it was tested whether chatbots could accurately verify the geometry of a model after receiving a g-code file and modify the file. For this purpose, each chatbot was asked the following series of questions:

1. Do you recognize the contents of the file~

2. This g-code contains instructions for creating a model with a specific geometry. Are you able to identify the shape of the model’s geometry~

3.Describe the appearance of the model based on the movements of the 3D printer’s extruder as contained in the g-code.

4. Provide a specific answer without analysis to the questions: What is it, and what are its dimensions~ Your answer should follow this example: “Cube 20 [mm] x 20 [mm] x 20 [mm].”

5. Please generate a file containing the modified g-code.(For example: Increase the height from 10 [mm] to 20 [mm].)

For each model, the last command (the fifth) in the conversation with the chatbot is presented in the table below (

Table 1).

The final test aimed to determine whether chatbots could independently generate a complex component in the form of g-code ready for printing. The object to be created was a gear with specified parameters. The command sent to the chatbot is presented below:

Generate a g-code file that represents a gear with the following parameters:

Tooth module (m): 1 [mm]

Number of teeth (z): 20

Pitch diameter (d): 20 [mm]

Outer diameter (de): 22 [mm]

Root diameter (df): 17.5 [mm]

Gear thickness (b): 5 [mm]

Tooth angle (α): 20o

Tooth profile: involute

3. Results

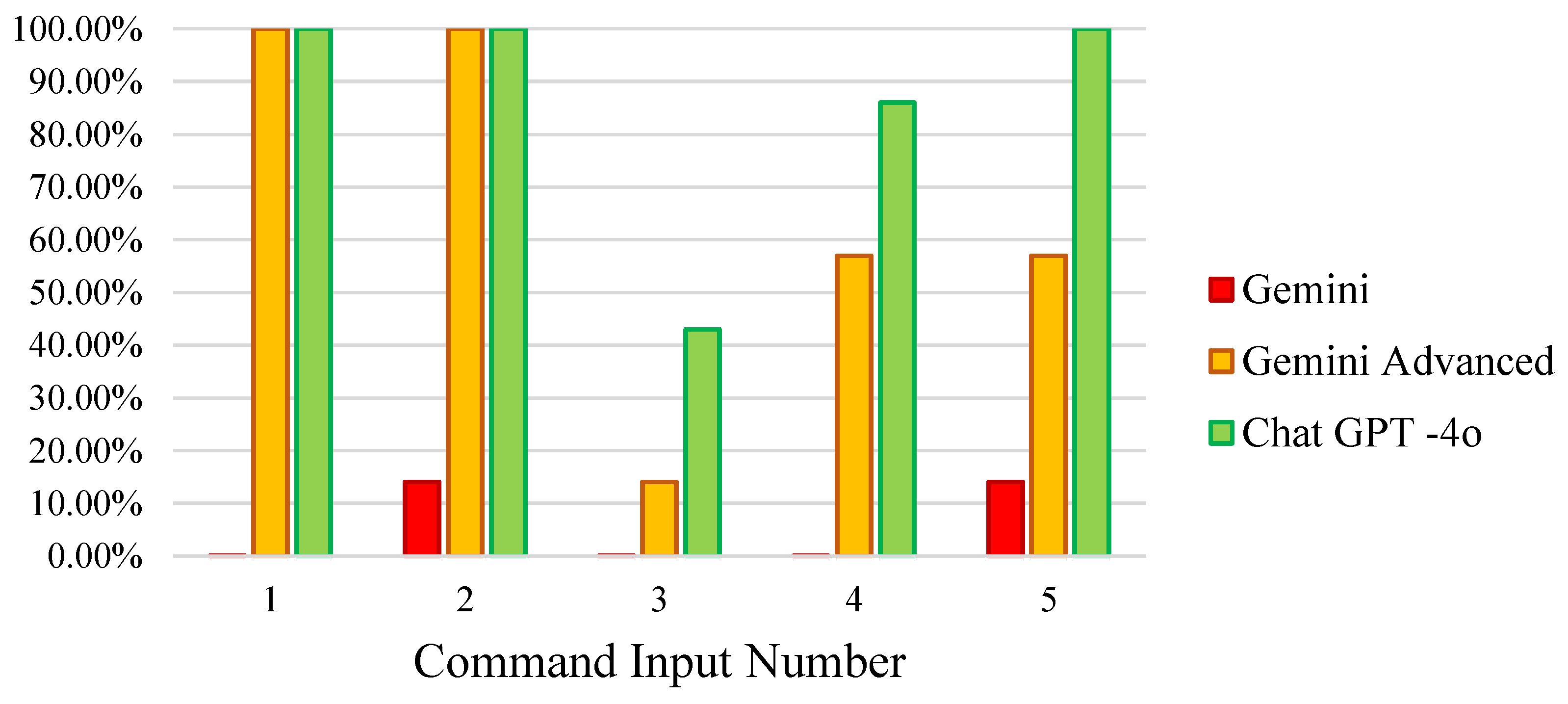

To accurately verify whether chatbots can detect defects and correctly adjust printing parameters, a percentage evaluation of correct responses provided by the chatbots was presented, followed by a visual assessment of the models produced after the suggested changes were implemented. The percentage results were calculated based on responses for each verified defect and are shown in the figure below (

Figure 1).

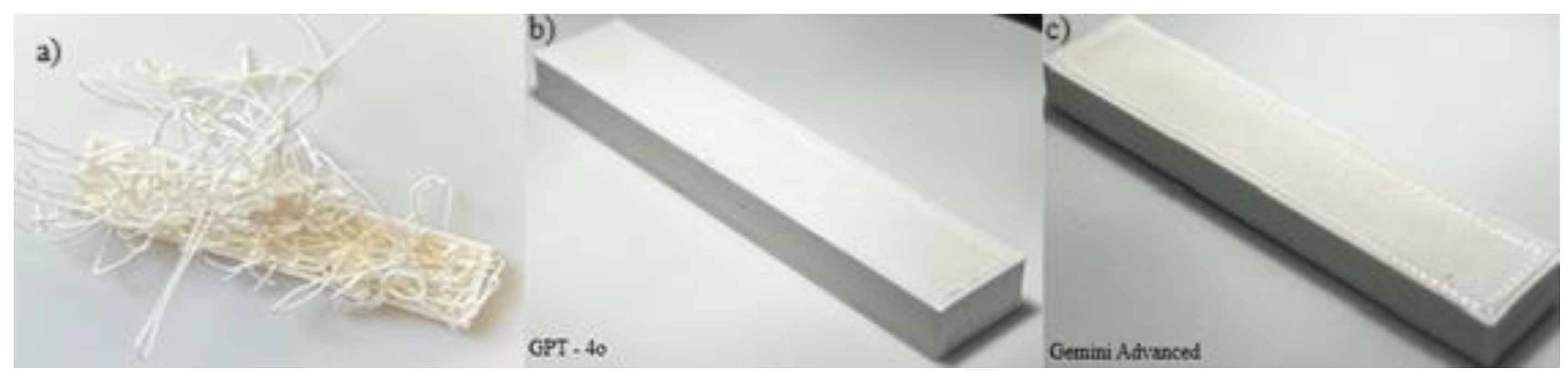

The figure below (

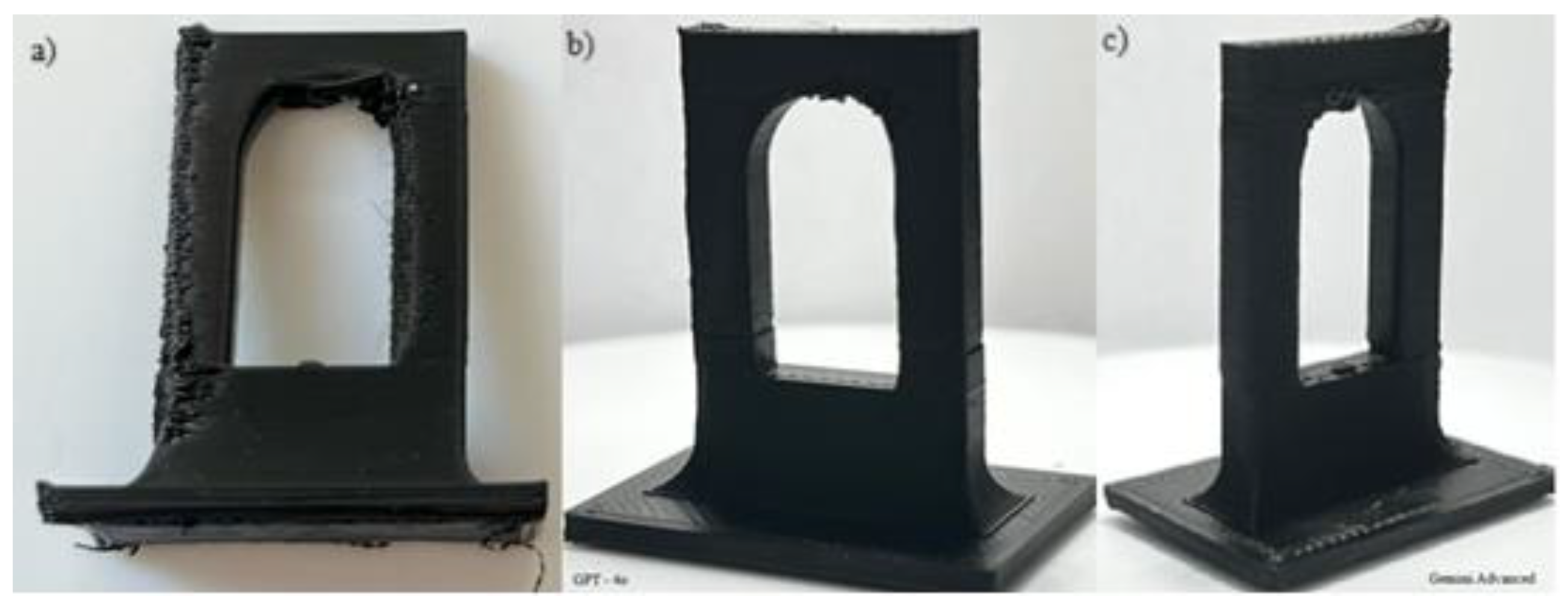

Figure 2) shows a comparison of three printed objects from the same project. On the left is a print with the “spaghetti effect” defect, while next to it are images of the prints after applying the parameters suggested by Chatbot GPT-4o and Gemini Advanced. Further analysis of the basic chatbot version was discontinued.

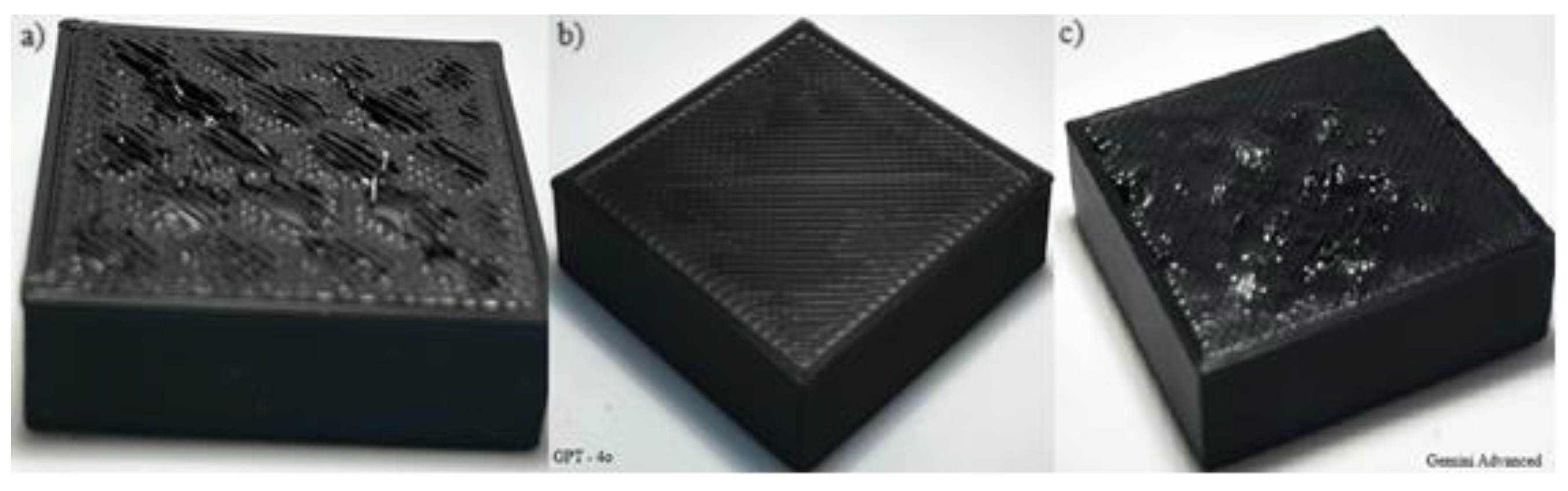

Below (

Figure 3) is the under-extrusion defect in the 3D print and the difference in the quality of the prints depending on the parameters generated by each specific chatbot.

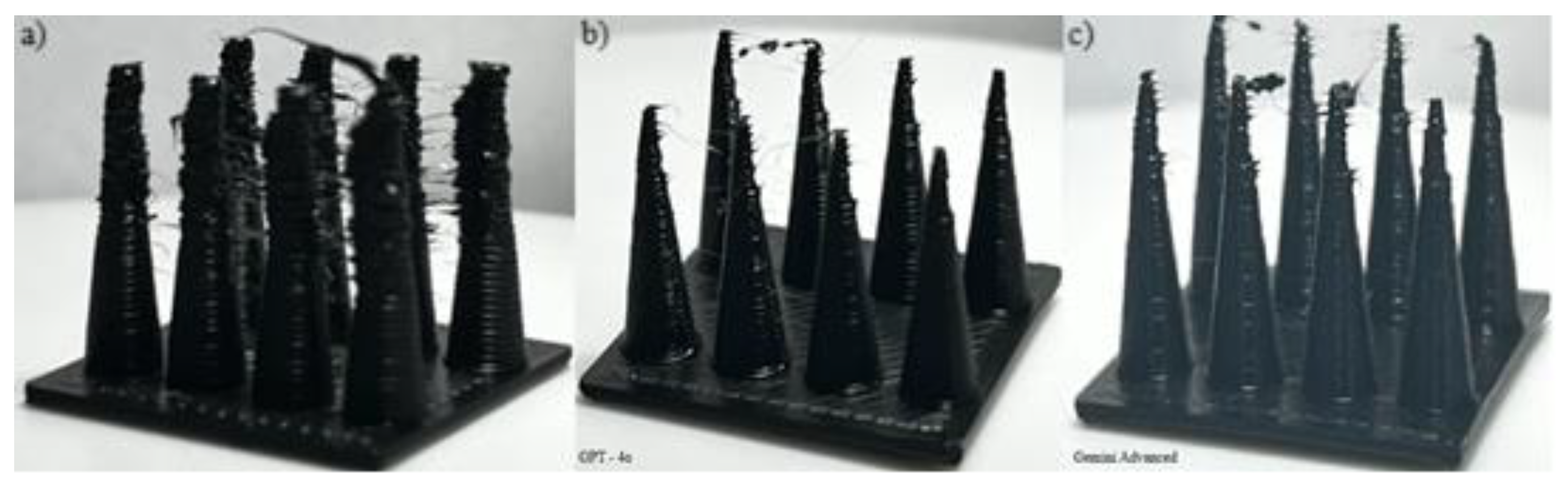

The figure below (

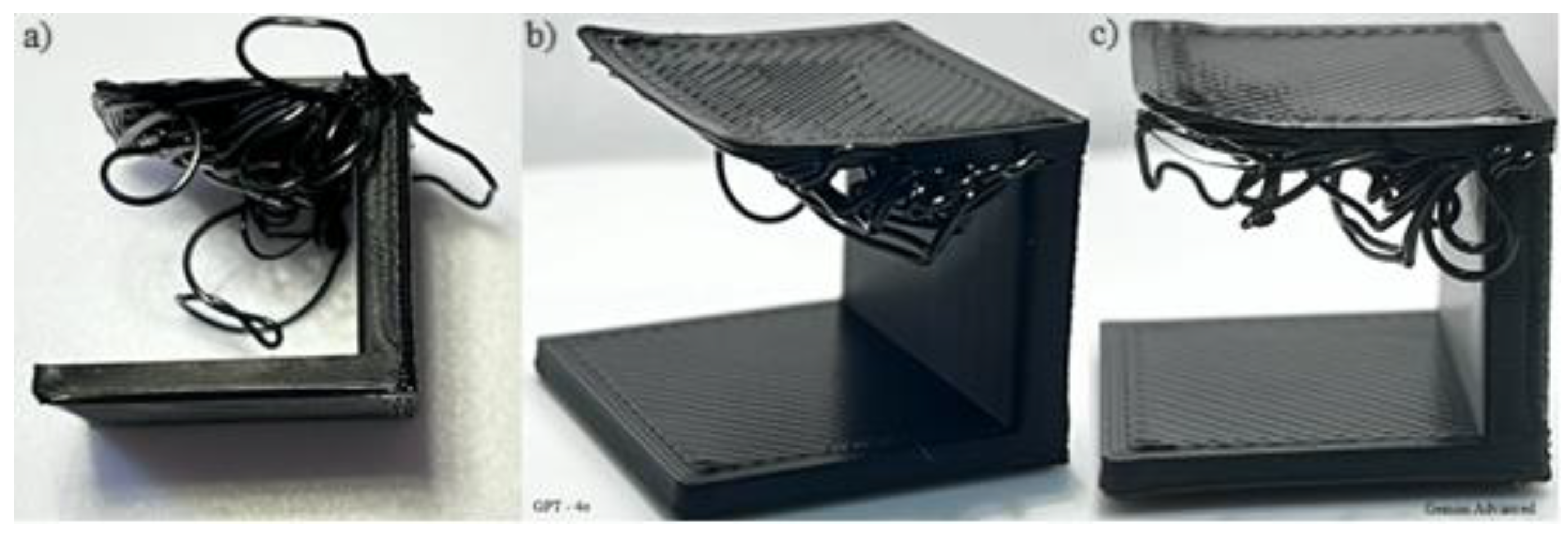

Figure 4) shows the defect of stringing (oozing) and images of the object after applying the suggested changes from Chatbot GPT-4o and Gemini Advanced.

The defect known as warped corners (

Figure 5) is presented below, along with images of the model after applying the suggested changes from Chatbot GPT-4o and Gemini Advanced.

The figure below (

Figure 6) shows an image of the visible defect on the printed object, referred to as under-extruded material, along with images of the print after applying the suggested changes to the 3D printing process by Chatbot GPT-4o and Gemini Advanced.

The figure below (

Figure 7) illustrates a 3D printing defect known as overhangs (also referred to as weak bridges) and an image of the print after applying the suggested changes by Chatbot GPT-4o and Gemini Advanced.

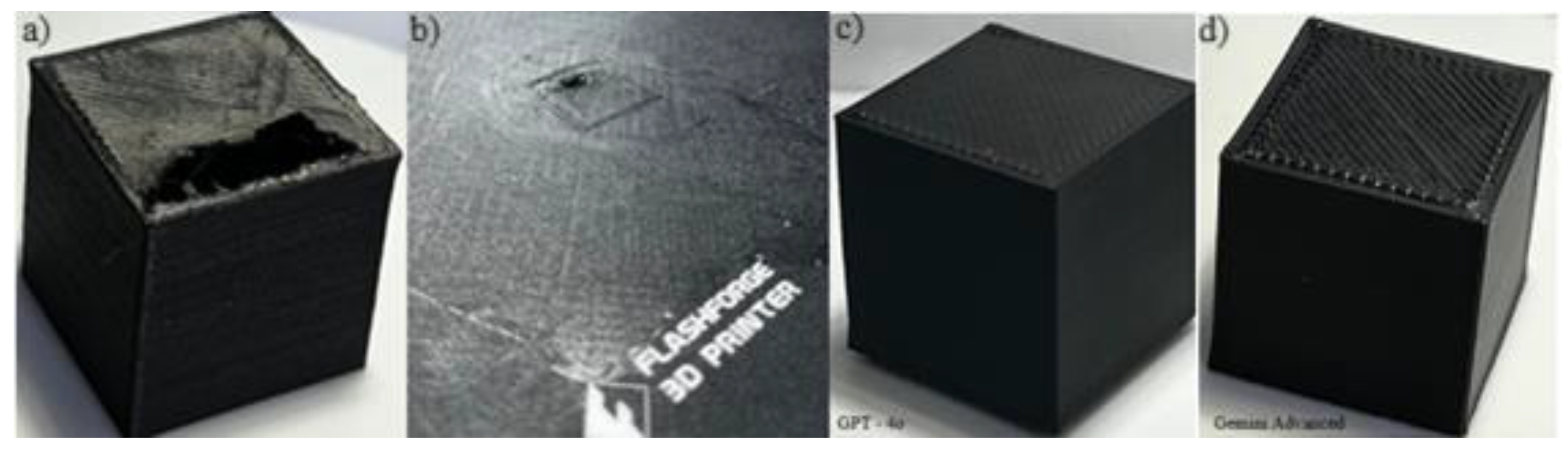

The figure below (

Figure 8) shows a printed model with a defect caused by material overheating. The material adhered to the 3D printer’s build platform, resulting in damage to both the printed object and the surface. Next to it, the printed trials after applying the changes suggested by Chatbot GPT-4o and Gemini Advanced are presented.

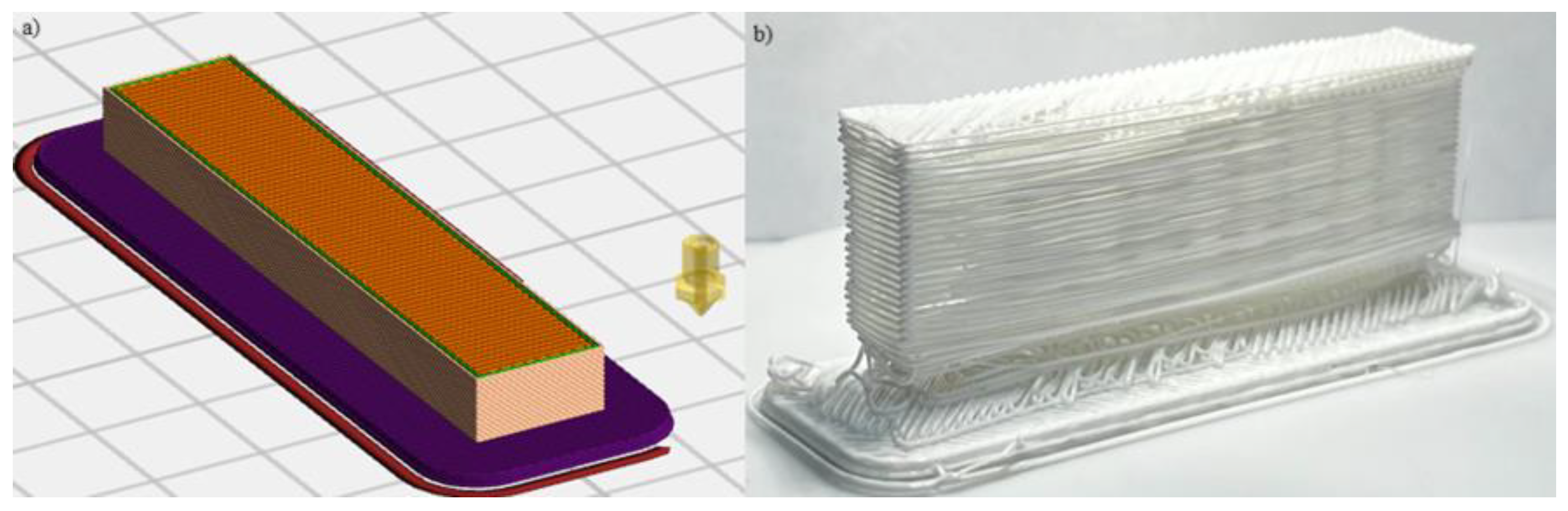

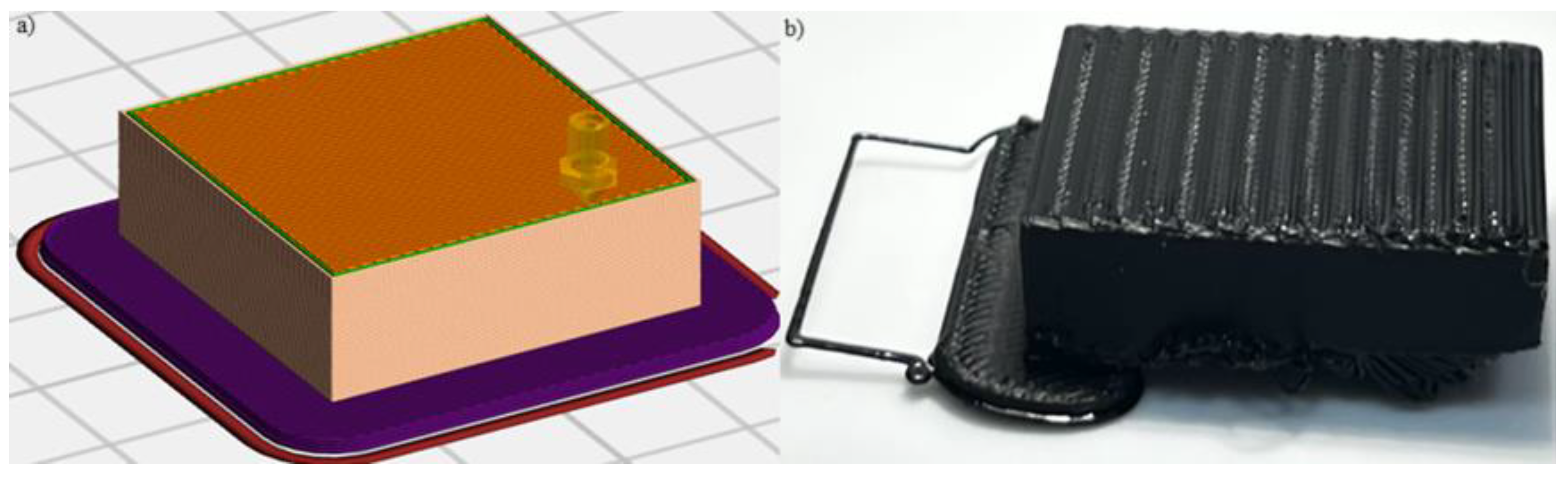

In the second experiment, it was tested whether chatbots could recognize the contents of a g-code file and modify it correctly. It turned out that only one of the three chatbots tested was able to recognize the contents of a g-code file: Chatbot GPT-4o. The first model was a rectangular prism with dimensions of 12x60x6 [mm]. The chatbot was asked to increase the model’s height. In the first case, the chatbot identified the shape as a rectangle and provided incorrect dimensions for the object. It stated that the object measured 12.30x36.3x50 [mm]. The chatbot was then asked to increase the model’s height from 6 [mm] to 20 [mm]. The chatbot sent a file with the modified g-code. The figure below (

Figure 9) shows the g-code visualization in the slicer before the modification by the chatbot (

Figure 9a) and the printed object on the right (

Figure 9b) based on the g-code generated by the chatbot.

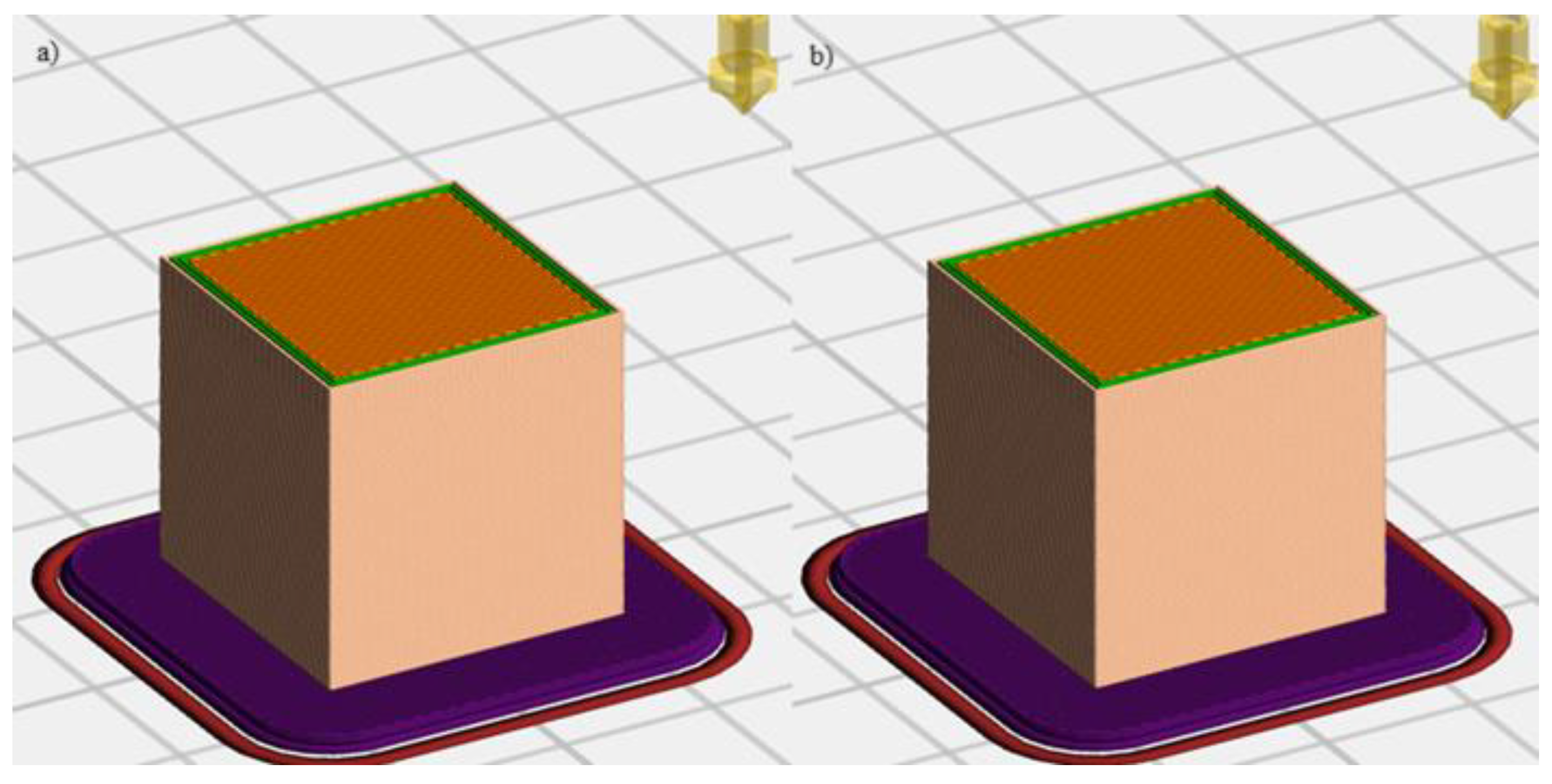

In the second case, the chatbot was asked to reduce the width. An additional complication for the chatbot was that the model sent to it was shaped like an inverted box and did not contain any infill. The second model was a rectangular prism (as a shell without one wall) with dimensions of 30x30x10 [mm]. Chatbot GPT-4o identified it as a rectangle with dimensions 30x60x14 [mm], which means it incorrectly recognized the shape of the uploaded model once again.

Figure 10 below shows the g-code visualization in the slicer before the modification by the chatbot (

Figure 10a) and the printed object on the right (

Figure 10b) based on the g-code generated by the chatbot.

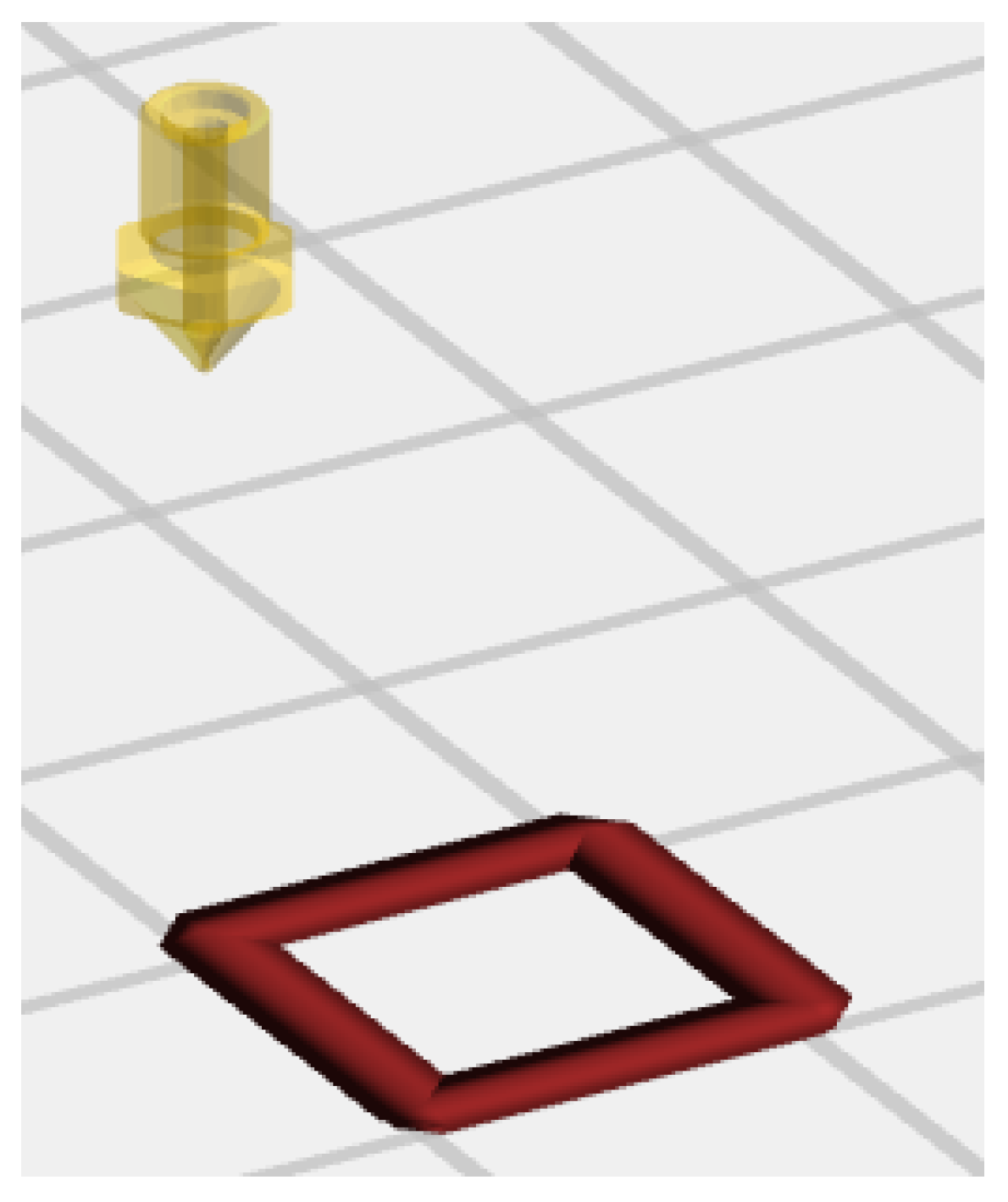

In the third trial, a cube with dimensions 20x20x20 [mm] was sent to the chatbot, and the task was to modify the model to create a cube with a 5 mm diameter through-hole in the center. In this case, the chatbot did not provide a clear answer regarding the identification of the model’s shape (see Appendix 3: Conversations with Chatbot GPT-4o). The visualization of the g-code in the FlashPrint 5 slicer before and after the conversation with Chatbot GPT-4o is shown in the figure below (

Figure 11).

No changes were observed in the g-code sent by the chatbot (

Figure 12), which led to the decision to abandon the attempt to print the model.

The final experiment aimed to determine whether Chatbot GPT-4o could generate a file with a 3D model based on specific geometry parameters. To accurately verify the chatbot’s capabilities, detailed geometric parameters were provided to be considered when generating the file. Chatbot GPT-4o generated a g-code file, which was intended to serve as the basis for printing the 3D model. The result of this process is presented below (

Figure 12).

The obtained geometry represents the outline, which is not sufficient to proceed with the decision to print it.

4. Discussion

Research was conducted on the use of AI chatbots in the FDM 3D printing process. Three different AI models were analyzed: Gemini, Gemini Advanced, and GPT-4o. The study demonstrated that advanced chatbots can detect defects in 3D-printed objects. By analyzing print images, AI successfully recognized defects, such as stringing, warped corners, and the spaghetti effect, confirming its utility in monitoring print quality. GPT-4o chatbot had the highest accuracy in identifying print defects, demonstrating its ability to optimize 3D printing process parameters by appropriately adjusting the input variables.

The study also showed that available chatbots can reduce the risk of defects, leading to improved quality of final products. After verifying the chatbot responses by printing models, it was determined that both the Gemini Advanced and GPT-4o chatbots are effective tools for performing tasks related to adjusting print parameters. However, limitations were encountered with the AI technology when dealing with small defects or incomplete databases. Additionally, chatbots are not always able to predict the correct impact of parameter modifications on the final result. The study of g-code file identification and modification revealed that GPT-4o AI technology can modify file contents, but not correctly. It was established that identifying the object in the print file and generating a g-code file model were too complex tasks for AI chatbots.

The results suggest that implementing AI systems into daily 3D printing operations could significantly enhance defect identification and print quality optimization.

5. Results

Advanced chatbots are capable of detecting defects in 3D-printed objects through image analysis. Chat GPT-4o demonstrated the highest accuracy in error identification. Both GPT-4o and Gemini Advanced chatbots perform tasks related to the correction of printing parameters effectively.

The study on g-code file content identification and modification revealed that GPT-4o’s AI technology can modify file content; however, the modifications were not accurate.

It was found that creating models in g-code files and modifying these files proved to be too demanding a task for AI-based chatbots.

Funding

The research presented in this article was conducted as part of the master’s thesis titled “The Use of Artificial Intelligence in 3D Printing Using the FDM Method” by Fabian Filipiak, supervised by Krzysztof Łukaszewski at the Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, Poznan University of Technology, 2024. The funding source is research project number 0613/SBAD/4770, financed by the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the author, upon reasonable request.

Appendix 1

Table 1.

Parameters entered into the chatbot and the received responses for the 3D printing defect known as the spaghetti effect.

Table 1.

Parameters entered into the chatbot and the received responses for the 3D printing defect known as the spaghetti effect.

| No. |

Parameter Name |

Default Value |

Entered Value |

ReReesponse from Gemini Advanced |

Response from GPT-4o |

| 1. |

Nozzle Size |

0.4 [mm] |

0.4 [mm] |

0.4 [mm] |

0.4 [mm] |

| 2. |

Material Type |

PLA |

PLA |

PLA |

PLA |

| 3. |

Filament Size |

1.75 [mm] |

1.75 [mm] |

1.75 [mm] |

1.75 [mm] |

| 4. |

Extruder Temperature |

220°C |

220°C |

225–230

228°C |

200–210

205°C |

| 5. |

Platform Temperature |

55°C |

0°C |

50–60

55°C |

50–60

55°C |

| 6. |

Layer Height |

0.2 [mm] |

0.2 [mm] |

0.2 or 0.15

0.2 |

0.2 [mm] |

| 7. |

First Layer Height |

0.3 [mm] |

0.3 [mm] |

0.3 [mm] |

0.2 [mm] |

| 8. |

Base Print Speed |

50 [mm/s] |

150 [mm/s] |

120–130

125 [mm/s] |

40–60

50 [mm/s]

|

| 9. |

Number of Perimeters |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

| 10. |

Top Solid Layers |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

| 11. |

Bottom Solid Layers |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

| 12. |

Infill Density |

15% |

5% |

5% |

5% |

| 13. |

Raft Inclusion |

YES |

NO |

NO |

NO |

| 14. |

Cooling Fan Control |

On (after first layer) |

On (after first layer) |

On (after first layer) |

On (after first layer) |

| 15. |

Travel Speed |

100 [mm/s] |

150 [mm/s] |

100–120

110 [mm/s] |

150 [mm/s] |

| 16. |

Minimum Speed |

6 [mm/s] |

20 [mm/s] |

20 [mm/s] |

20 [mm/s] |

| 17. |

First Layer Print Speed |

15 [mm/s] |

60 [mm/s] |

60 [mm/s] |

60 [mm/s] |

| 18. |

First Layer Travel Speed |

70 [mm/s] |

190 [mm/s] |

100 [mm/s] |

190 [mm/s] |

| 19. |

Maximum Speed for Initial Layers |

30 [mm/s] |

195 [mm/s] |

60–80

70 [mm/s] |

195 [mm/s] |

Table 2.

Parameters entered into the chatbot and the received responses for the 3D printing defect known as under-extrusion.

Table 2.

Parameters entered into the chatbot and the received responses for the 3D printing defect known as under-extrusion.

| No. |

Parameter Name |

Default Value |

Entered Value |

ReReesponse from Gemini Advanced |

Response from GPT-4o |

| 1. |

Nozzle Size |

0.4 [mm] |

0.4 [mm] |

0.4 [mm] |

0.4 [mm] |

| 2. |

Material Type |

PLA |

ABS |

ABS |

ABS |

| 3. |

Filament Size |

1.75 [mm] |

1.75 [mm] |

1.75 [mm] |

1.75 [mm] |

| 4. |

Extruder Temperature |

240°C |

240°C |

245°C – 255°C

250°C |

240°C

|

| 5. |

Platform Temperature |

105°C |

105°C |

105°C |

1.75 [mm] |

| 6. |

Layer Height |

0.2 [mm] |

0.2 [mm] |

0.2 [mm] |

0.2 [mm] |

| 7. |

First Layer Height |

0.3 [mm] |

0.3 [mm] |

0.3 [mm] |

0.3 [mm] |

| 8. |

Base Print Speed |

50 [mm/s] |

120 [mm/s] |

80–100

90 [mm/s] |

40–60

50 [mm/s]

|

| 9. |

Number of Perimeters |

2 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

| 10. |

Top Solid Layers |

4 |

2 |

2 |

4–5

4 |

| 11. |

Bottom Solid Layers |

3 |

0 |

2 |

1–2 |

| 12. |

Infill Density |

15% |

15% |

15% |

20–25 %

20% |

| 13. |

Raft Inclusion |

YES |

YES |

YES |

YES |

| 14. |

Cooling Fan Control |

On (after first layer) |

On (after first layer) |

On (after first layer) |

On (after first layer) |

| 15. |

Support Distance form the Model (Height) |

0,15 [mm] |

0,17 [mm] |

0,17 [mm] |

0,17 [mm] |

| 16. |

Number of Middle Raft Layers |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

| 17. |

Speed of the First Top Layer |

50% |

100% |

100% |

50–70%

60% |

| 18. |

Overlapping of the Perimeter |

20% |

0% |

0% |

0% |

Table 3.

Parameters entered into the chatbot and the received responses for the 3D printing defect known as stringing.

Table 3.

Parameters entered into the chatbot and the received responses for the 3D printing defect known as stringing.

| No. |

Parameter Name |

Default Value |

Entered Value |

ReReesponse from Gemini Advanced |

Response from GPT-4o |

| 1. |

Nozzle Size |

0.4 [mm] |

0.4 [mm] |

0.4 [mm] |

0.4 [mm] |

| 2. |

Material Type |

PLA |

ABS |

ABS |

ABS |

| 3. |

Filament Size |

1.75 [mm] |

1.75 [mm] |

1.75 [mm] |

1.75 [mm] |

| 4. |

Extruder Temperature |

240°C |

265°C |

265°C |

240–250

245°C |

| 5. |

Platform Temperature |

105°C |

105°C |

110°C |

105°C |

| 6. |

Layer Height |

0.2 [mm] |

0.2 [mm] |

0.2 [mm] |

0.2 [mm] |

| 7. |

First Layer Height |

0.3 [mm] |

0.3 [mm] |

0.3 [mm] |

0.3 [mm] |

| 8. |

Base Print Speed |

50 [mm/s] |

20 [mm/s] |

15 [mm/s] |

40–60

50 [mm/s] |

| 9. |

Number of Perimeters |

2 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

| 10. |

Top Solid Layers |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

| 11. |

Bottom Solid Layers |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

| 12. |

Infill Density |

15% |

15% |

15% |

15% |

| 13. |

Raft Inclusion |

YES |

NO |

NO |

YES |

| 14. |

Retraction length |

6 [mm] |

3 [mm] |

6 |

5–7

6 [mm] |

| 15. |

Retraction Speed |

30 [mm/s] |

15 [mm/s] |

40 [mm/s] |

30–35

30 [mm/s] |

| 16. |

Extrusion Speed |

30 [mm/s] |

20 [mm/s] |

20 [mm/s] |

20 [mm/s] |

Table 4.

Parameters entered into the chatbot and the received responses for the 3D printing defect known as warped corner.

Table 4.

Parameters entered into the chatbot and the received responses for the 3D printing defect known as warped corner.

| No. |

Parameter Name |

Default Value |

Entered Value |

ReReesponse from Gemini Advanced |

Response from GPT-4o |

| 1. |

Nozzle Size |

0.4 [mm] |

0.4 [mm] |

0.4 [mm] |

0.4 [mm] |

| 2. |

Material Type |

PLA |

ABS |

ABS |

ABS |

| 3. |

Filament Size |

1.75 [mm] |

1.75 [mm] |

1.75 [mm] |

1.75 |

| 4. |

Extruder Temperature |

240°C |

240°C |

250–255

253°C |

240°C |

| 5. |

Platform Temperature |

105°C |

40°C |

90–110°C

100°C |

100°C |

| 6. |

Layer Height |

0.2 [mm] |

0.2 [mm] |

0.2 [mm] |

0.2 [mm] |

| 7. |

First Layer Height |

0.3 [mm] |

0.3 [mm] |

0.3 [mm] |

0.3 [mm] |

| 8. |

Base Print Speed |

50 [mm/s] |

50 [mm/s] |

50 [mm/s] |

50 [mm/s] |

| 9. |

Number of Perimeters |

2 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

| 10. |

Top Solid Layers |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

| 11. |

Bottom Solid Layers |

3 |

3 |

3 |

5 |

| 12. |

Infill Density |

15% |

15% |

15% |

15% |

| 13. |

Raft Inclusion |

YES |

NO |

YES |

YES |

| 14. |

Cooling Fan Control |

On (after first layer) |

On (after first layer) |

On (after first layer) |

Disabled |

| 15. |

Infill Pattern |

Hexagonal |

Linear |

Linear |

Linear |

| 16. |

Infill start angle |

– |

45° |

45° |

45 |

| 17. |

Cross Hatch Angle |

– |

90° |

90° |

90 |

Table 5.

Parameters entered into the chatbot and the received responses for the 3D printing defect known as under- extruded material.

Table 5.

Parameters entered into the chatbot and the received responses for the 3D printing defect known as under- extruded material.

| No. |

Parameter Name |

Default Value |

Entered Value |

ReReesponse from Gemini Advanced |

Response from GPT-4o |

| 1. |

Nozzle Size |

0.4 [mm] |

0.4 [mm] |

0.4 [mm] |

0.4 [mm] |

| 2. |

Material Type |

PLA |

ABS |

ABS |

ABS |

| 3. |

Filament Size |

1.75 [mm] |

1.75 [mm] |

1.75 [mm] |

1.75 [mm] |

| 4. |

Extruder Temperature |

240°C |

215°C |

230–240

235 °C |

230–240

235 °C |

| 5. |

Platform Temperature |

105°C |

105°C |

110 °C |

110 °C |

| 6. |

Layer Height |

0.2 [mm] |

0.2 [mm] |

0.2 [mm] |

0,1–0,15

0,15 [mm] |

| 7. |

First Layer Height |

0.3 [mm] |

0.3 [mm] |

0.3 [mm] |

0.3 [mm] |

| 8. |

Base Print Speed |

50 [mm/s] |

100 [mm/s] |

60–80

70 [mm/s] |

40–60

50 [mm/s] |

| 9. |

Number of Perimeters |

2 |

2 |

2 |

3–4

3 |

| 10. |

Top Solid Layers |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

| 11. |

Bottom Solid Layers |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

| 12. |

Infill Density |

15% |

15% |

20-25%

20% |

15% |

| 13. |

Raft Inclusion |

YES |

YES |

NO |

YES |

| 14. |

Cooling Fan Control |

On (after first layer) |

On (after first layer) |

On (after first layer) |

On (after first layer) |

| 15. |

Support type |

Linear |

Tree-like |

Tree-like |

Tree-like |

Table 6.

Parameters entered into the chatbot and the received responses for the 3D printing defect known as overhangs.

Table 6.

Parameters entered into the chatbot and the received responses for the 3D printing defect known as overhangs.

| No. |

Parameter Name |

Default Value |

Entered Value |

ReReesponse from Gemini Advanced |

Response from GPT-4o |

| 1. |

Nozzle Size |

0.4 [mm] |

0.4 [mm] |

0.4 [mm] |

0.4 [mm] |

| 2. |

Material Type |

PLA |

ABS |

ABS |

ABS |

| 3. |

Filament Size |

1.75 [mm] |

1.75 [mm] |

1.75 [mm] |

1.75 [mm] |

| 4. |

Extruder Temperature |

240°C |

255°C |

240–250

245 °C |

245–250

247 °C |

| 5. |

Platform Temperature |

105°C |

105°C |

105°C |

105°C |

| 6. |

Layer Height |

0.2 [mm] |

0.2 [mm] |

0.2 [mm] |

0.2 [mm] |

| 7. |

First Layer Height |

0.3 [mm] |

0.3 [mm] |

0.3 [mm] |

0.3 [mm] |

| 8. |

Base Print Speed |

50 [mm/s] |

50 [mm/s] |

40–45

43 [mm/s] |

40–50

45 [mm/s] |

| 9. |

Number of Perimeters |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

| 10. |

Top Solid Layers |

4 |

4 |

4 |

5 |

| 11. |

Bottom Solid Layers |

3 |

3 |

3 |

4 |

| 12. |

Infill Density |

15% |

10% |

10% |

10% |

| 13. |

Raft Inclusion |

YES |

YES |

YES |

YES |

| 14. |

Cooling Fan Control |

On (after first layer) |

On (after first layer) |

On (after first layer) |

Off |

| 15. |

Full Infill Layer Speed |

50% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

Table 7.

Parameters entered into the chatbot and the received responses for the 3D printing defect known as material overheating.

Table 7.

Parameters entered into the chatbot and the received responses for the 3D printing defect known as material overheating.

| No. |

Parameter Name |

Default Value |

Entered Value |

ReReesponse from Gemini Advanced |

Response from GPT-4o |

| 1. |

Nozzle Size |

0.4 [mm] |

0.4 [mm] |

0.4 [mm] |

0.4 [mm] |

| 2. |

Material Type |

PLA |

ABS |

ABS |

ABS |

| 3. |

Filament Size |

1.75 [mm] |

1.75 [mm] |

1.75 [mm] |

1.75 [mm] |

| 4. |

Extruder Temperature |

240 °C |

265 °C |

230–250

240 °C

|

240–250

245 °C

|

| 5. |

Platform Temperature |

110 °C |

110 °C |

90–100

95 °C |

110 °C |

| 6. |

Layer Height |

0.2 [mm] |

0.2 [mm] |

0.2 [mm] |

0.2 [mm] |

| 7. |

First Layer Height |

0.3 [mm] |

0.3 [mm] |

0.3 [mm] |

0.3 [mm] |

| 8. |

Base Print Speed |

50 [mm/s] |

120 [mm/s] |

50–80

65 [mm/s] |

50 –60

55 [mm/s] |

| 9. |

Number of Perimeters |

3 |

2 |

2 |

3–4

3 |

| 10. |

Top Solid Layers |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

| 11. |

Bottom Solid Layers |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

| 12. |

Infill Density |

15% |

40% |

40% |

40% |

| 13. |

Raft Inclusion |

YES |

NO |

NO |

YES |

| 14. |

Cooling Fan Control |

On (after first layer) |

OFF |

On (after first layer) |

OFF |

| 15. |

First Layer Print Speed |

10 [mm/s] |

20 [mm/s] |

20 [mm/s] |

20 [mm/s] |

| 16. |

Retraction Length |

6 [mm] |

3 [mm] |

3 [mm] |

3 [mm] |

References

- „PKN - Drukowanie 3D: Wytwarzanie Przyrostowe,” PKN (Polski Komitet Normalizacyjny). Available online: https://www.pkn.pl/informacje/2019/06/drukowanie-3d-wytwarzanie-przyrostowe.

- B3D, „B3D,” [Online]. Available: https://b3d.com.pl/technologie-przyrostowe-podstawowe-informacje/. [Data uzyskania dostępu: 19 08 2024].

- Sung Mould & Plastic, „Sung Mould & Plastic,” [Online]. Available: https://sungplastic.com/pl/additive-method-subtractive-method-in-production/. [Data uzyskania dostępu: 19 08 2024].

- R. Mendaza-DeCal, S. R. Mendaza-DeCal, S. Peso-Fernandez i J. Rodriguez-Quiros, „Orthotics and prosthetics by 3D-printing: Accelerating its fabrication flow,” Research in Veterinary Science, 2023.

- „3D w praktyce,” [Online]. Available: https://3dwpraktyce.pl/. [Data uzyskania dostępu: 19 08 2024].

- „CADxpert,” [Online]. Available: https://cadxpert.pl/5-popularnych-technologii-druku-3d-fdm-sla-sls-polyjet-dmls/. [Data uzyskania dostępu: 19 08 2024].

- Z. Zhu, D.W.H. Z. Zhu, D.W.H. Ng, H.S. Park, M.C. McAlpine, „3D-printed multifunctional materials enabled by artificial-intelligence-assisted fabrication technologies,” Nat. Rev. Mater., pp. 27 - 47, 2020.

- Liang Ma, Shijie Yu, Xiaodong Xu, Sidney Moses Amadi, Jing Zhang, Zhifei Wang, „Application of Artificial Intelligence in 3D Printing Physical Organ Models,” College of Materials Science and Engineering, Zhejiang University of Technology, Hangzhou, 310000, China, 2023.

- J. Go, A.J. J. Go, A.J. Hart, „Fast desktop-scale extrusion additive manufacturing,” Addit. Manuf, p. 276–284, 2017.

- Hinton G, Deng L, Yu D, Dahl GE, et al., „Deep neural networks for acoustic modeling in speech recognition: the shared views of four research groups.,” IEEE Signal Process Mag, p. 82–97, 2012.

- He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J., „Deep residual learning for image recognition.,” w Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition., 2016.

- Palagi S, Fischer P, „Bioinspired microrobots,” Nature Reviews Materials (w skrócie “Nat Rev Mater”), pp. [CrossRef]

- Yu KH, Beam AL, Kohane S., „Artificial intelligence in healthcare,” Nat Biomed Eng, p. 719–31, 2018.

- Me A, Mc A, Fkhg A, et al., „Harnessing artificial intelligence for the next generation of 3D printed medicines.,” Adv Drug Deliv Rev, 2021.

- Stone P, Brooks R, Brynjolfsson E, et al., „Artificial Intelligence and Life in 2030. One hundred year study on artificial intelligence: report of the 2015–2016 study panel,” Stanford University, Stanford, 2016.

- Yuchen Jiang, Xiang Li, Hao Luo, Shen Yin, Okyak Kaynak, „Quo Vadis Artificial intelligence,” 2022.

- Menal Dahiya, „A Tool of Conversation: Chatbot,” A Tool of Conversation: Chatbot, 2017.

- C. R. Anik, C. C. R. Anik, C. Jacob, A. Mohanan, „A Survey on Web Based Conversational Bot Design,” JETIR, pp. 96-99, 2016.

- B. P. Kiptonui, „Chatbot Technology: A Possible Means of Unlocking Student Potential to Learn How to Learn,” Educational Research, pp. 218-221, 2013.

- R. S. Russell, „Language Use, Personality and True Conversational Interfaces,” AI and CS University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, 2002.

- Hector Quintero, Elisa Elizabeth Mendieta, Cesar Pinzon-Acosta, „Identifying an Image Classification Model for Welding Defects Detection,” w Technological University of Panama, Central, Panama, 2024.

- B. Setiaji, F. W. B. Setiaji, F. W. Wibowo, „Chatbot Using A Knowledge in Database,” w IEEE 7th International Conference on Intelligent Systems, Modelling and Simulation, Thailand, 2016.

- J. Pereira, Ó. Díaz, „Using health chatbots for behavior change: A mapping study,” Journal of Medical Systems, 2019.

- Conversational AI: Dialogue Systems, Conversational Agents, and Chatbots, „M. McTear,” Synthesis Lectures on Human Language Technologies, 2020.

- E. Adamopoulou, L. E. Adamopoulou, L. Moussiades, „An Overview of Chatbot Technology,” w IFIP International Conference on Artificial Intelligence Applications and Innovations, Cham, 2020.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).