Submitted:

02 August 2025

Posted:

04 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Inputs and Outputs in 3D Printing

1.1.1. What Is FDM 3D Printing

1.1.2. Materials and Properties

- PLA (Polylactic Acid): Easy to print, biodegradable, relatively low melting point (around 180-220°C) and a glass transition temperature between 60-65°C

- ABS (Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene): Stronger and more heat-resistant than PLA (with a melting point around 220-260°C and a glass transition temperature of ~105°C), but harder to print

1.1.3. The Print Head and Resolution

1.2. Our Goals

- Improving print surface quality and

- Enhancing printing speeds without compromising the quality of our parts.

2. Hardware-Software Setup

2.1. General Data About a Commercial Printer (Tevo Black Widow)

2.2. The Setup of Our Particular Printer

3. Quality and Speed Improvements

3.1. Quality Improvements

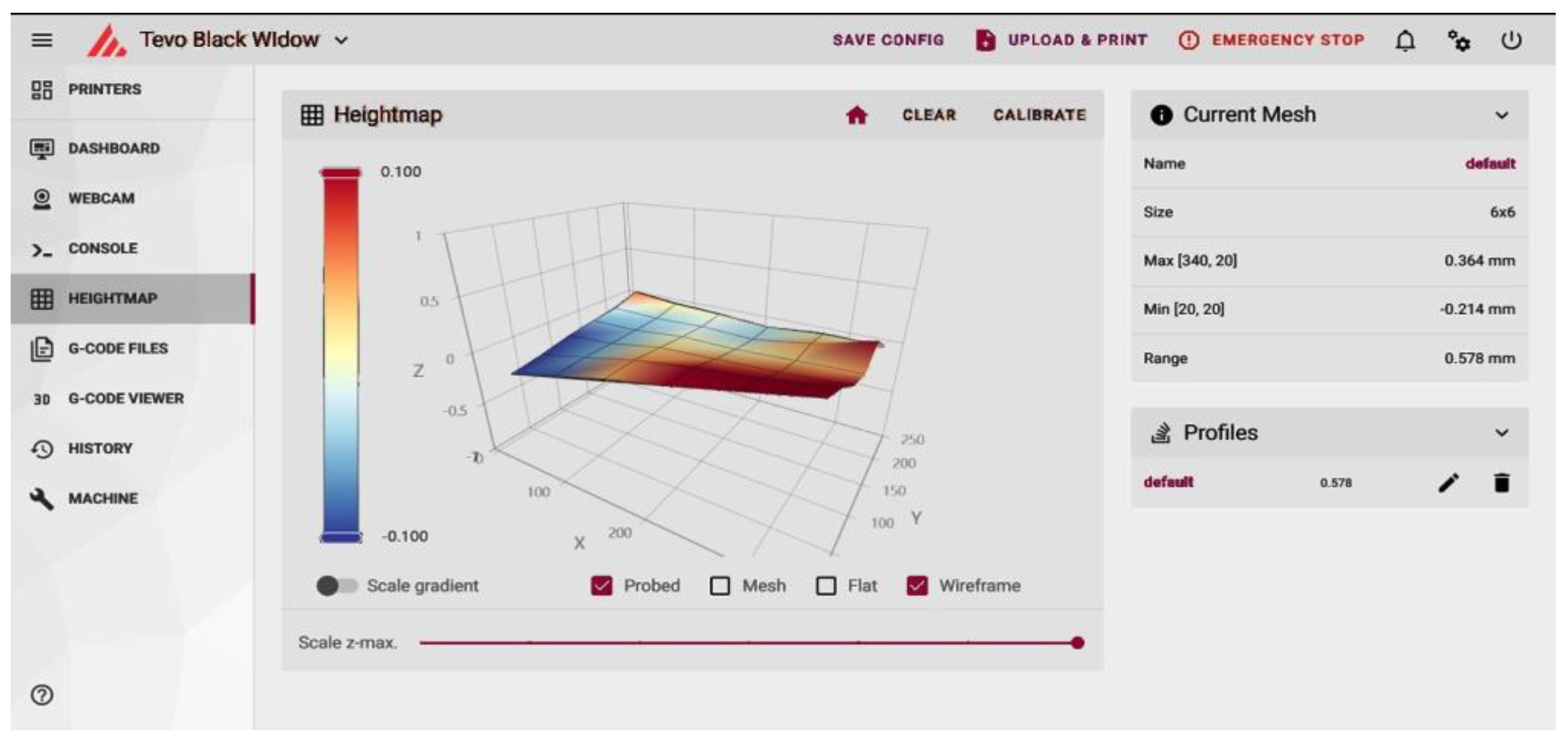

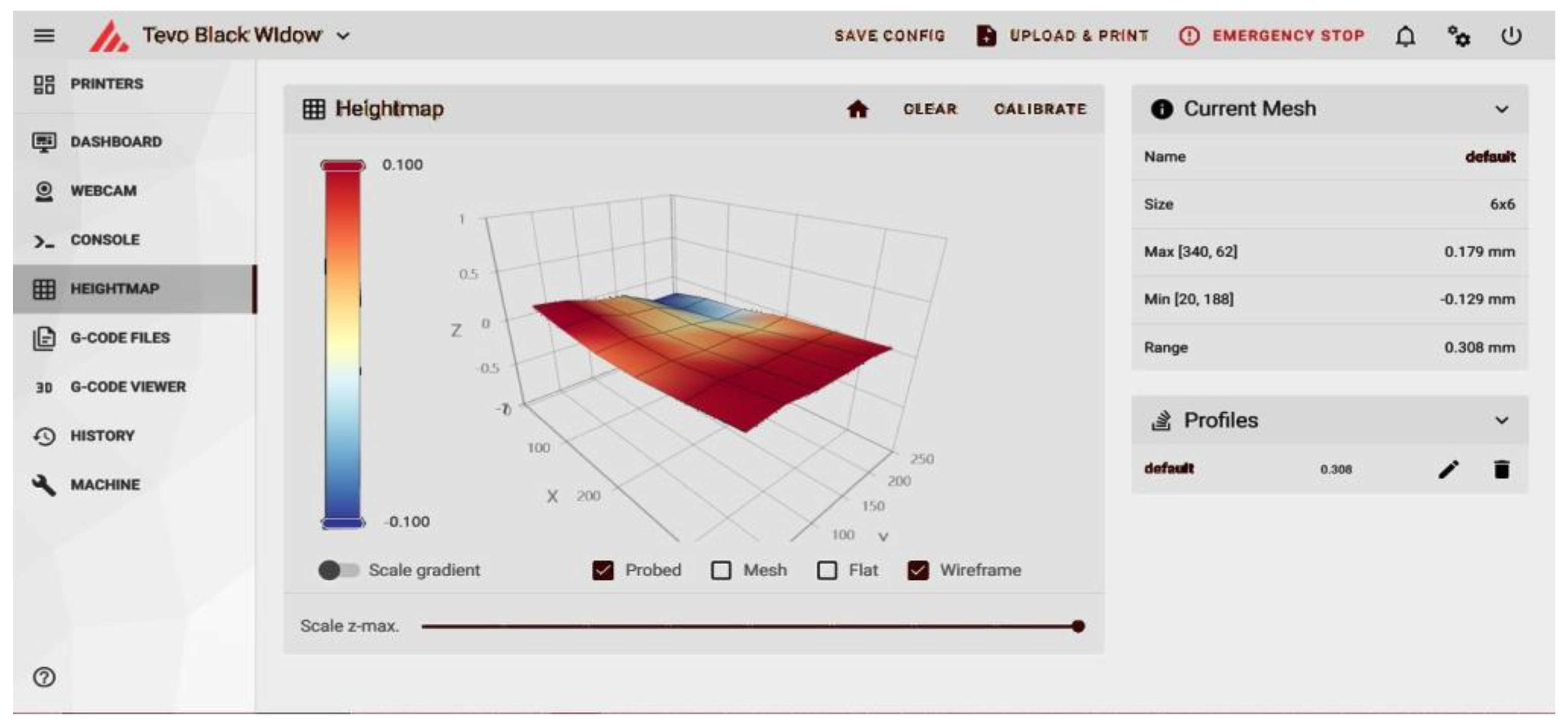

3.1.1. Measuring and Visualising the Flatness of the Bed

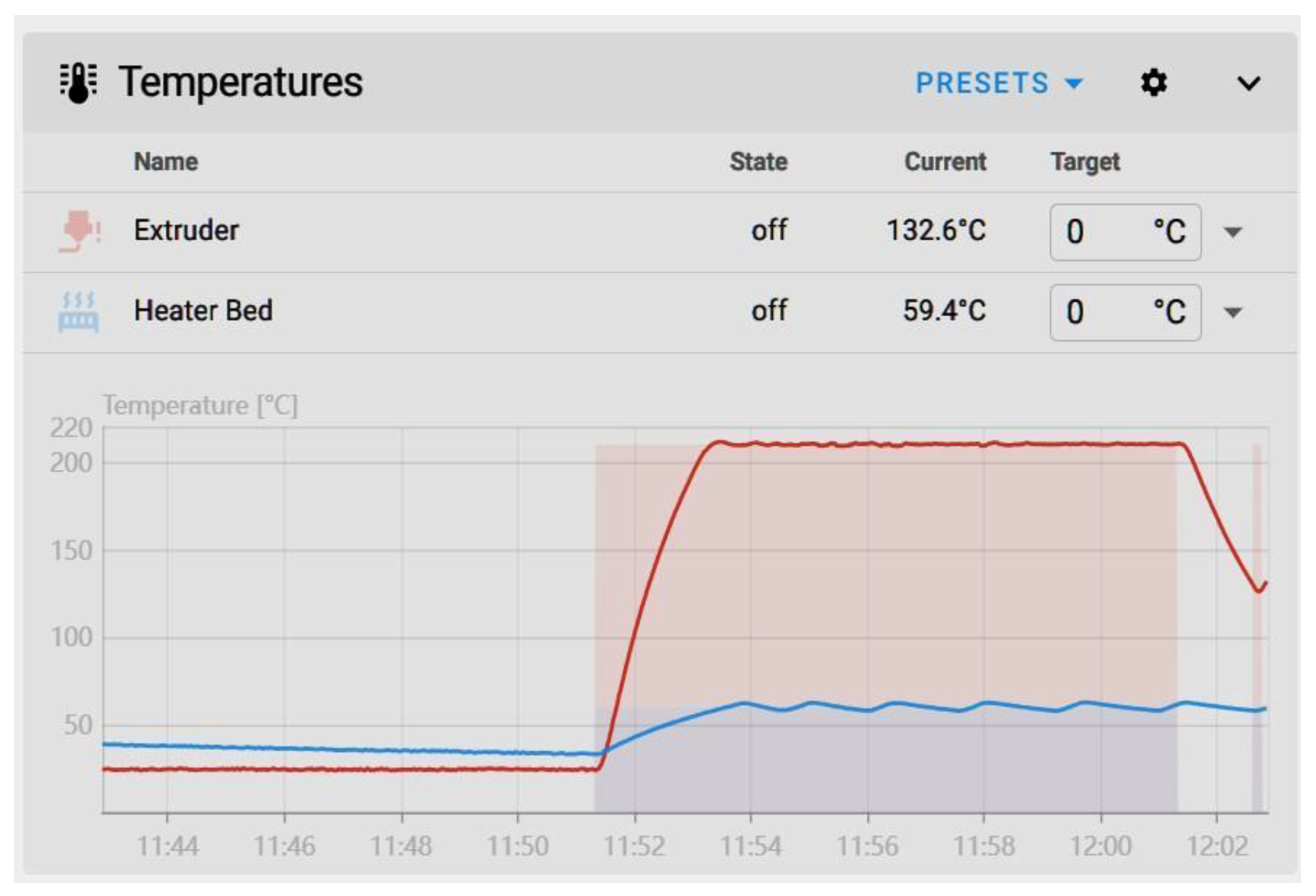

3.2. What Is PID Tuning and How It Works

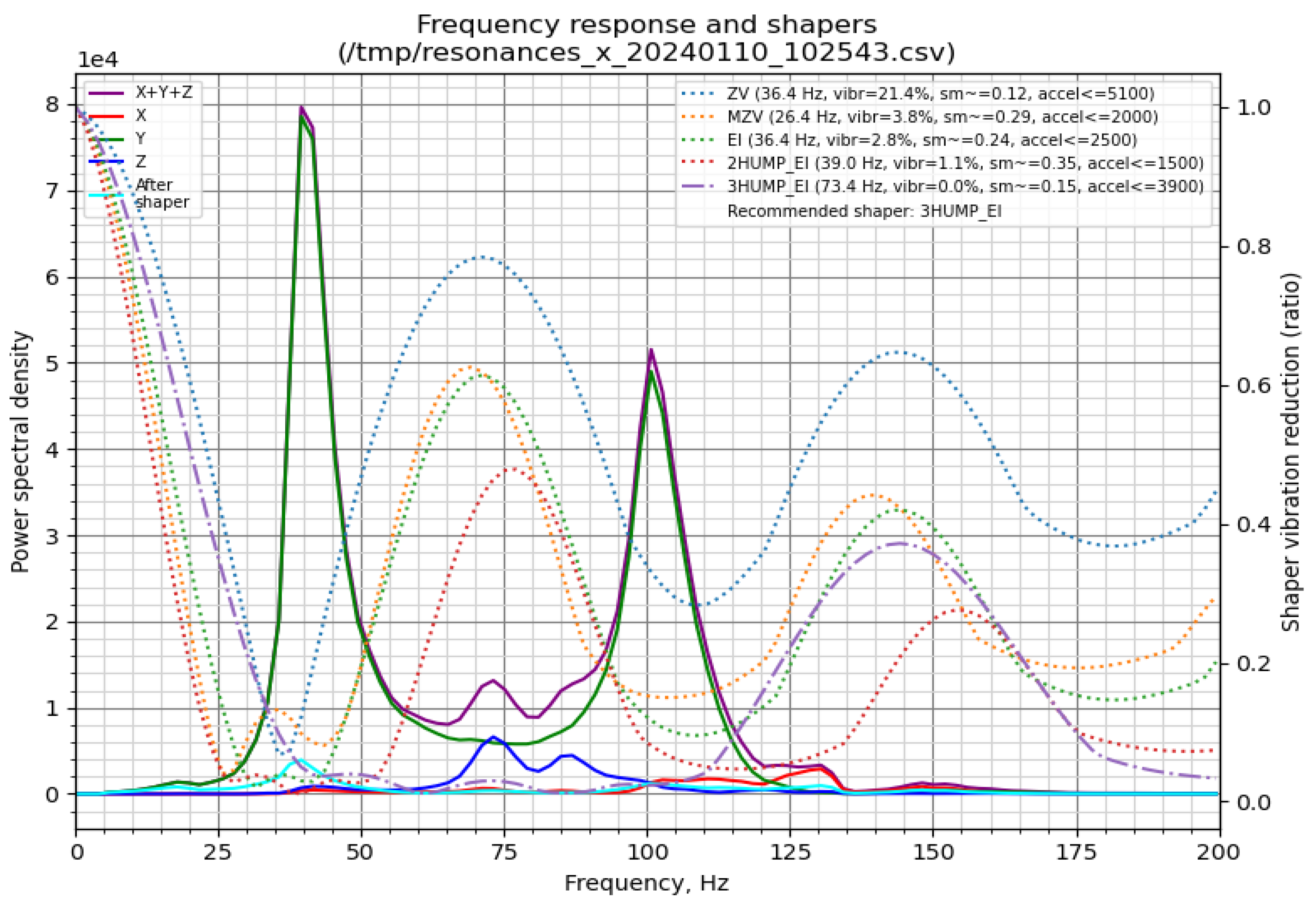

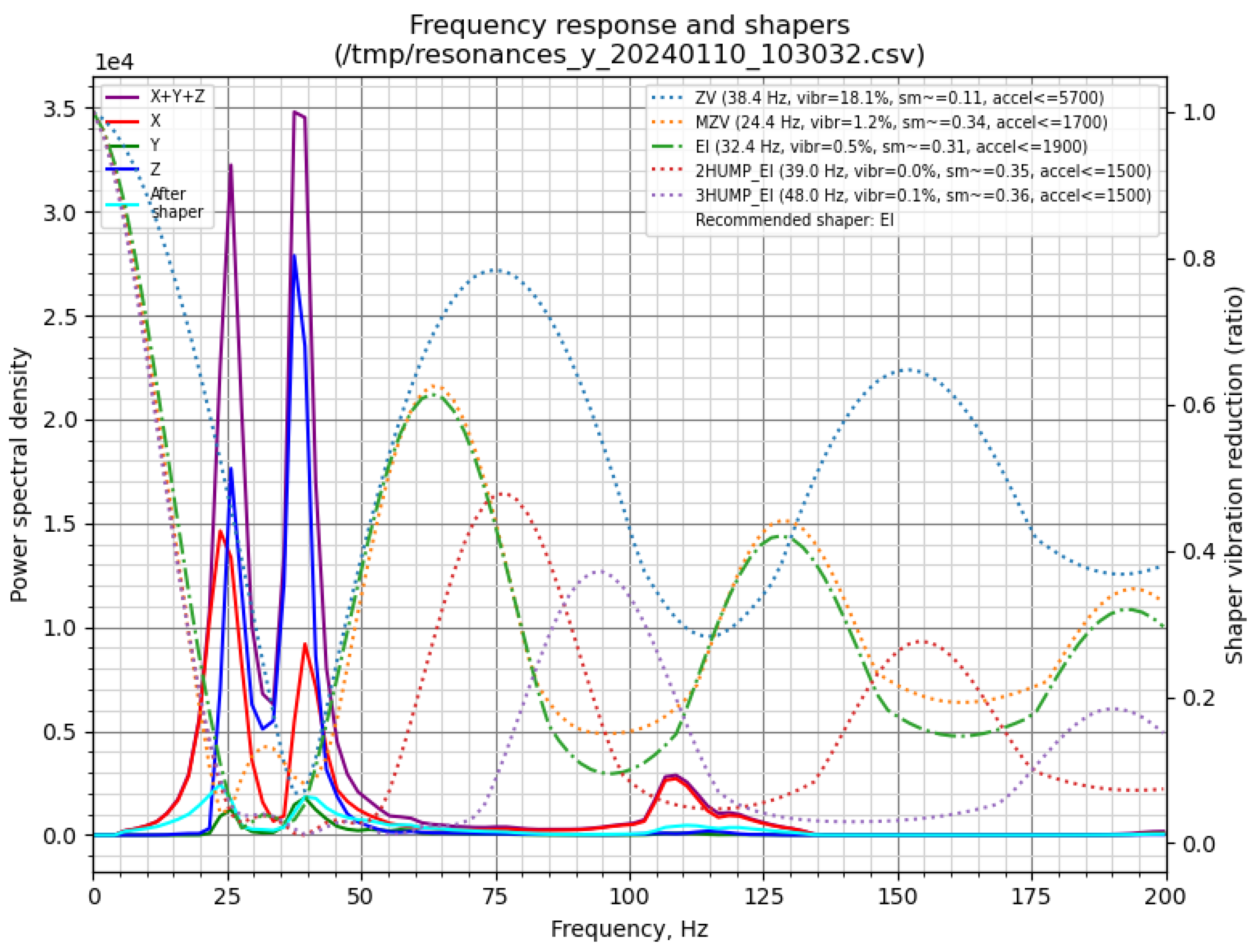

3.3. Input Shapers and Mechanical Vibrations

- ZV (Zero Vibration) is the simplest input shaper, consisting of two equal impulses. It is designed to cancel a single resonance frequency and introduces minimal delay. However, it offers limited vibration suppression and is sensitive to errors in the estimated frequency. Is a shaper with fast execution and minimal latency but sensitive to model inaccuracies.

- MZV (Modified Zero Vibration) improves on ZV by adding a third impulse, enhancing robustness and reducing residual vibration. It handles small errors in resonance estimation better but introduces slightly more delay. MZV has better suppression and modest robustness but is still sensitive to frequency drift. MZV is recommended for general-purpose compensation.

- EI (Extra Insensitive) is designed to be less sensitive to inaccuracies in resonance frequency detection. It balances vibration suppression and robustness better than ZV or MZV. It is moderately complex, with a longer impulse duration. EI is robust to resonance drift, good overall performance but has slightly higher delay. EI is suitable for systems with changing or uncertain resonances

- 2HUMP_EI extends EI by using additional impulses, allowing better suppression of both primary and harmonic frequencies. It is highly robust and reduces ghosting in prints but introduces notable execution delay. 2HUMP_EI has great suppression and improved print surface quality, but offers a slower response. 2HUMP_EI is ideal for printers with strong structural resonance and visible ghosting.

- 3HUMP_EI is the most advanced of the EI family. 3HUMP_EI uses even more impulses to flatten vibration over a wider frequency range. It achieves excellent ghosting suppression at the cost of the highest delay. It offers best overall suppression and extremely smooth prints but high latency and may limit speed or require tuning acceleration. Is best for high-speed or coreXY printers with demanding accuracy requirements.

3.4. Comparative Analysis

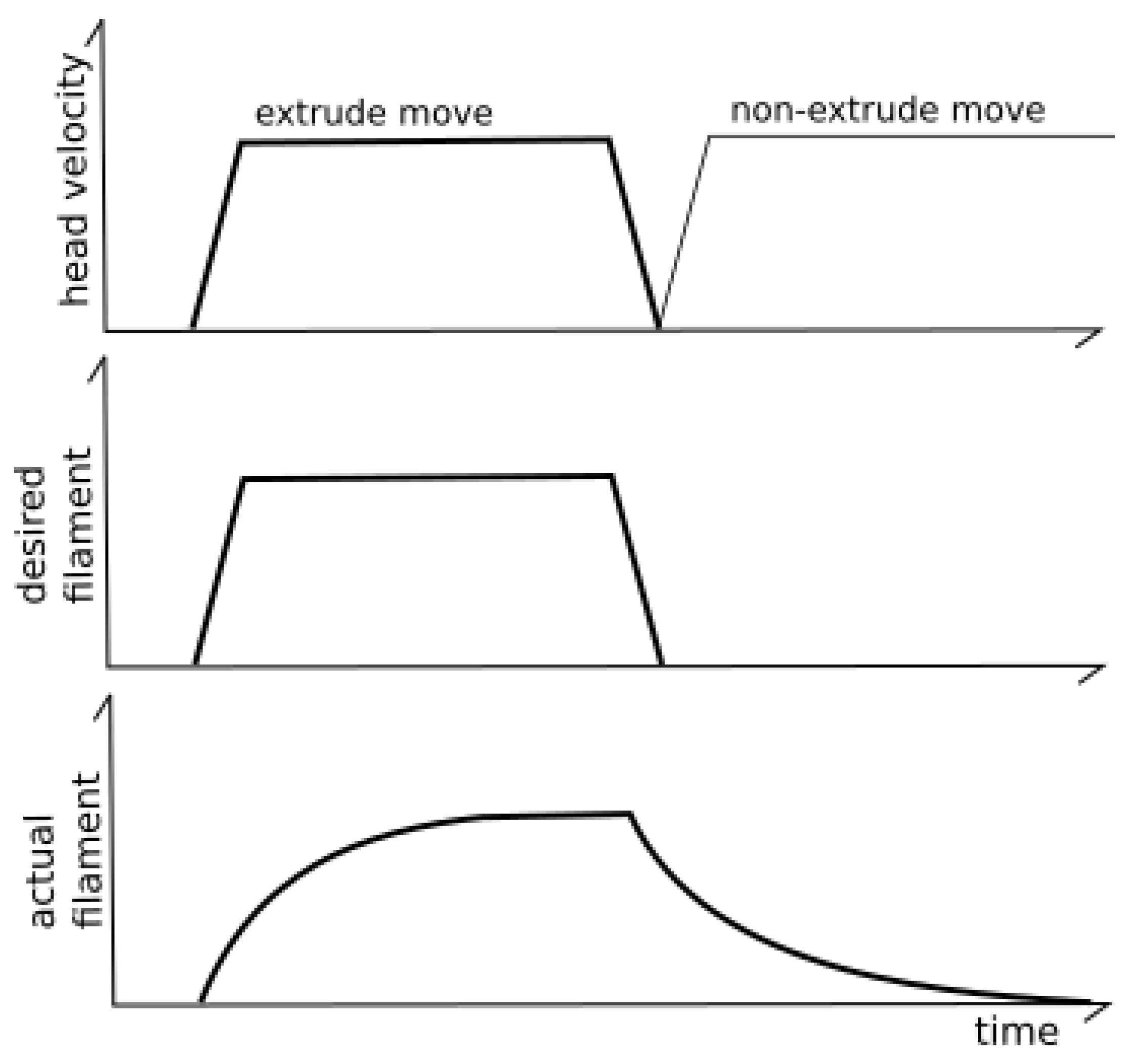

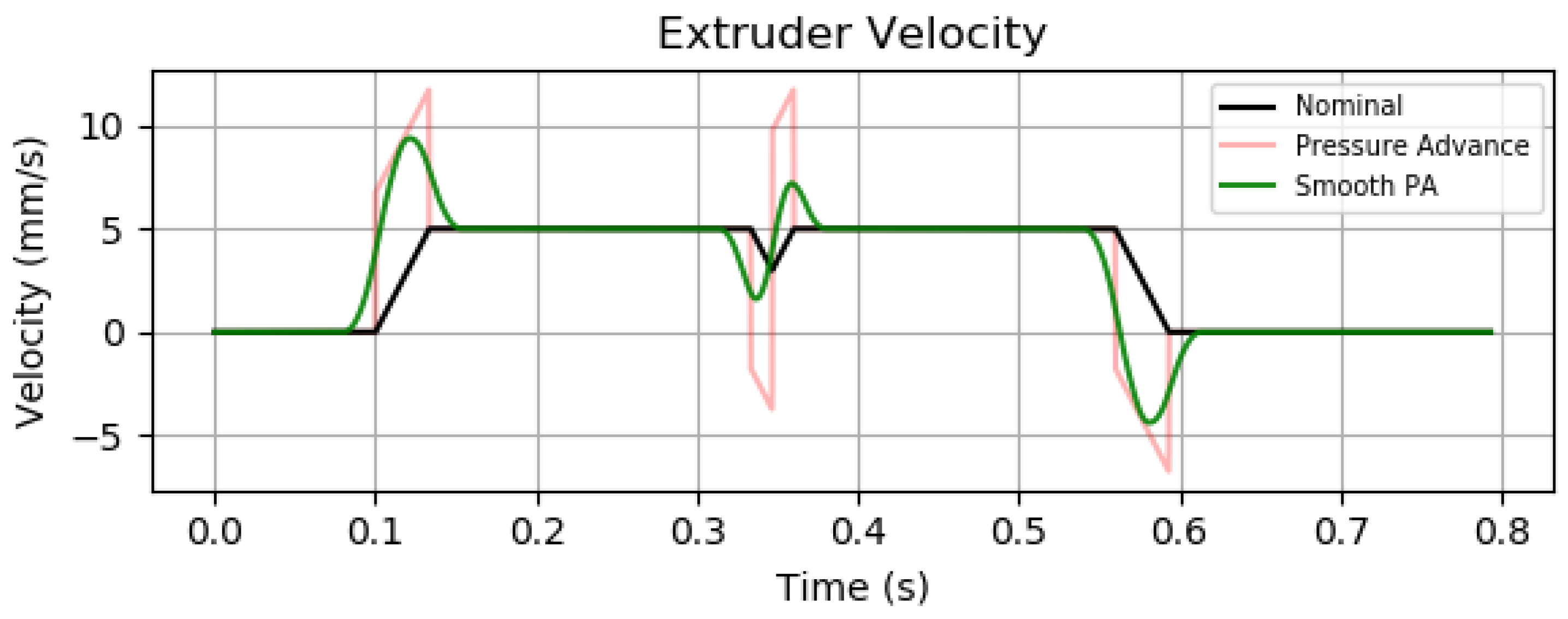

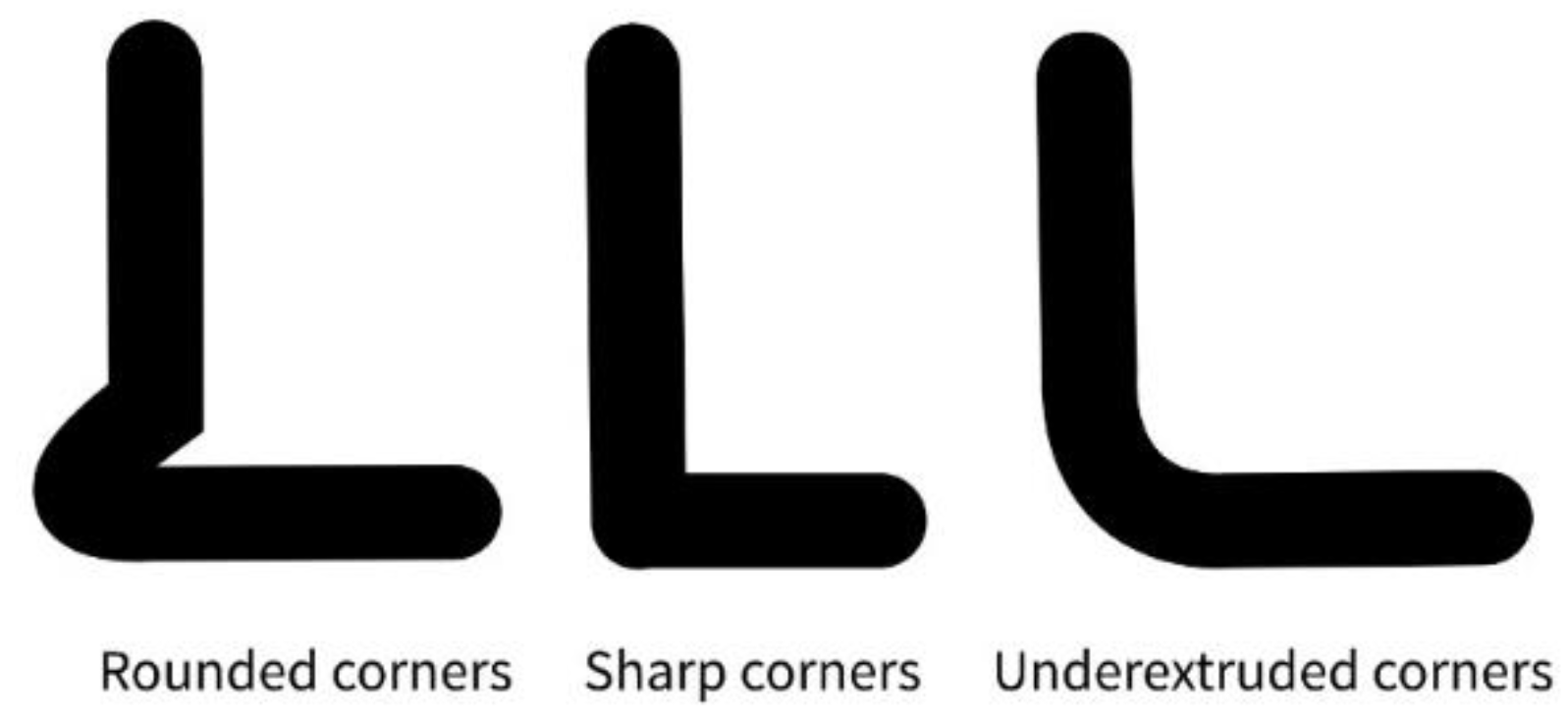

3.4. Pressure Advance

4. Performance Improvements

4.1. Theoretical Limits

4.2. Real-World Performance Improvements

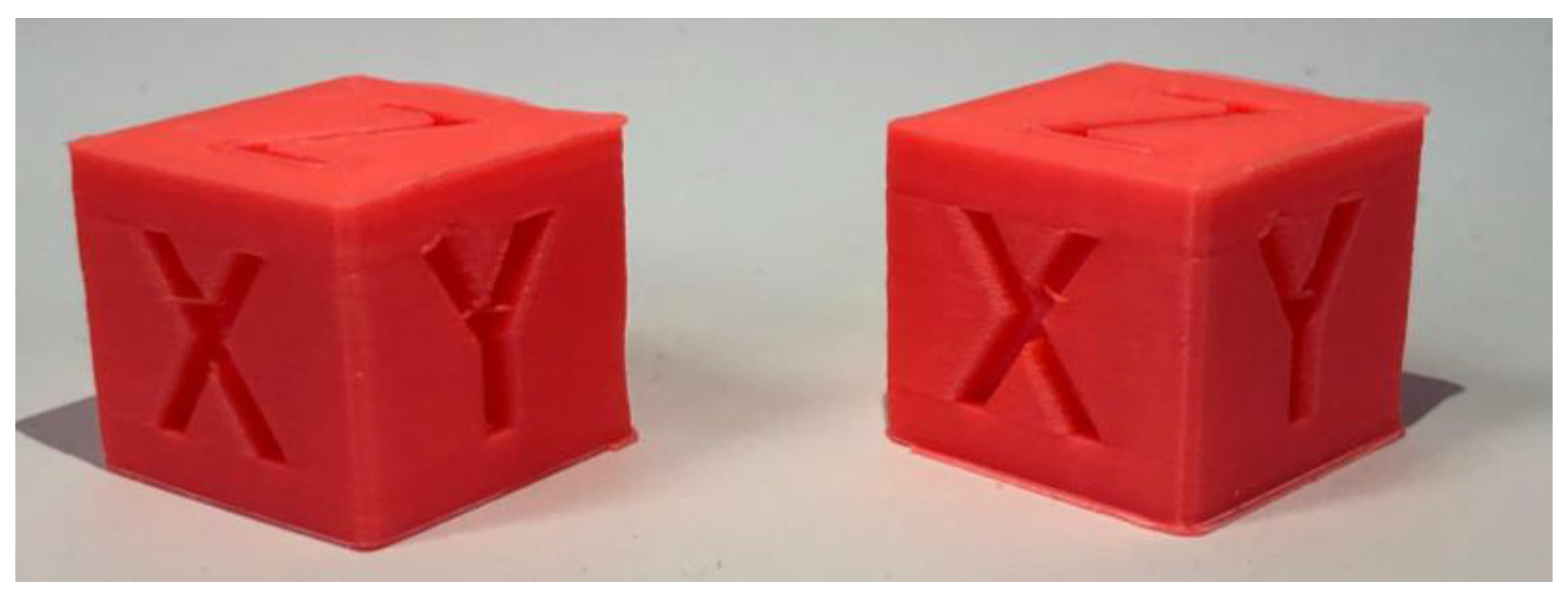

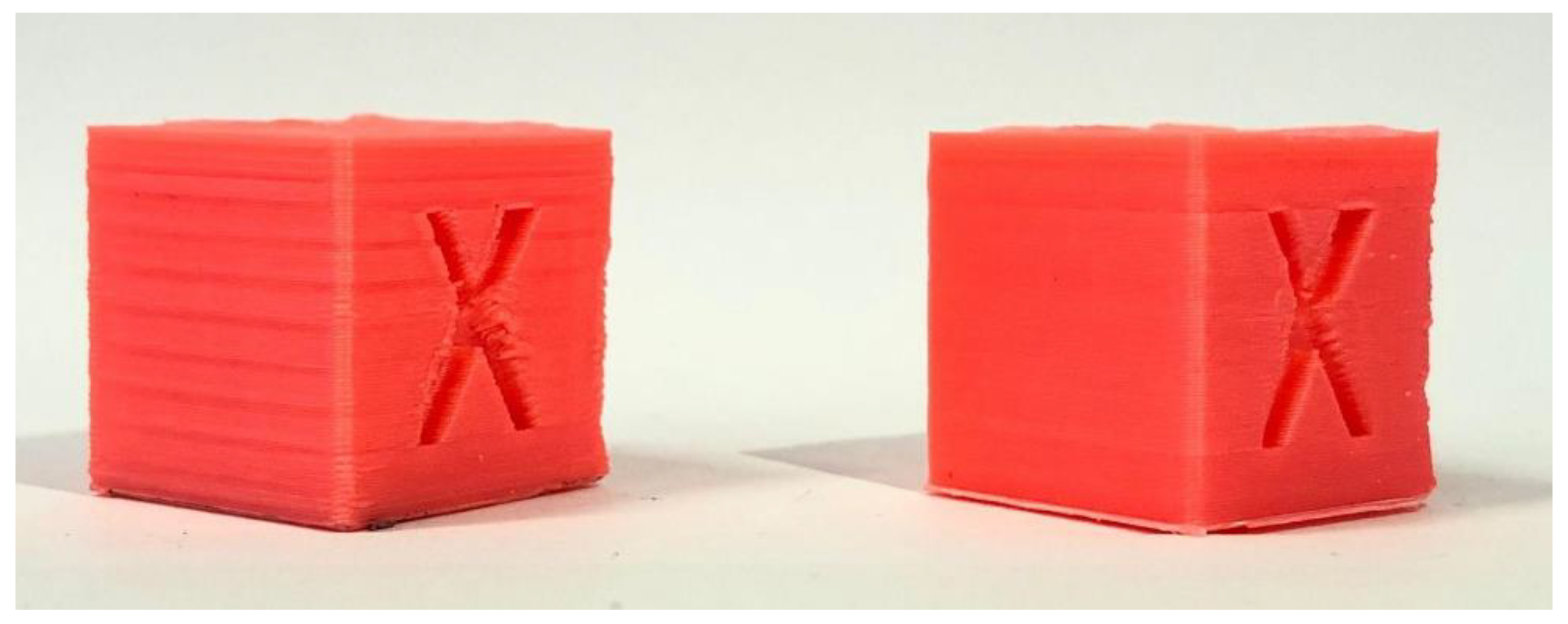

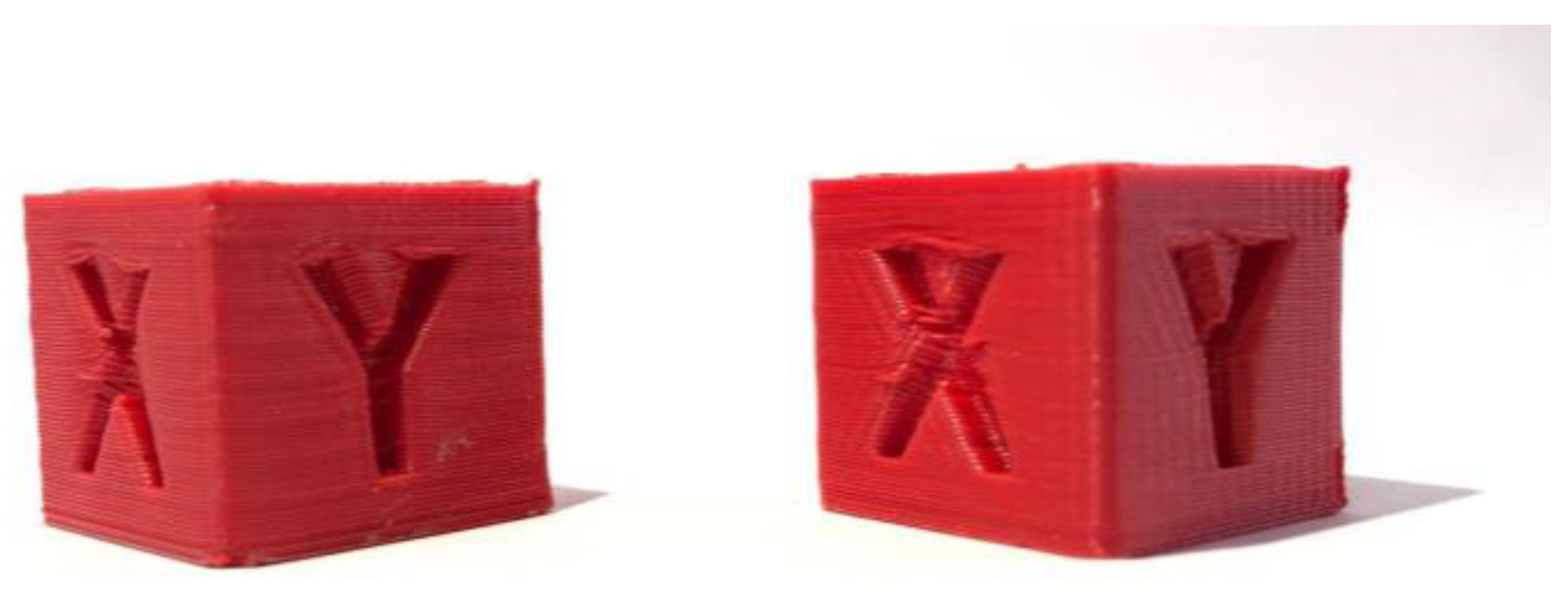

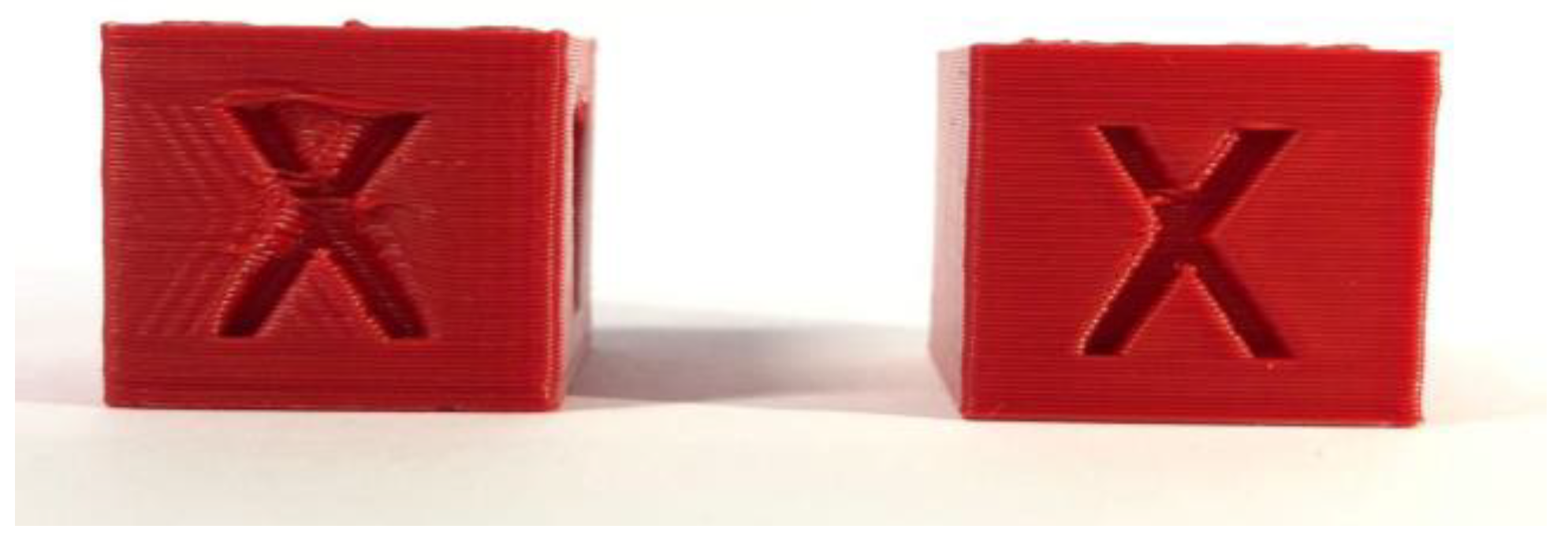

4.2.1. Calibration Cube

- Print speed: 100 mm/s

- Generate support: no

- Build plate adhesion: brim

- Ironing: enabled

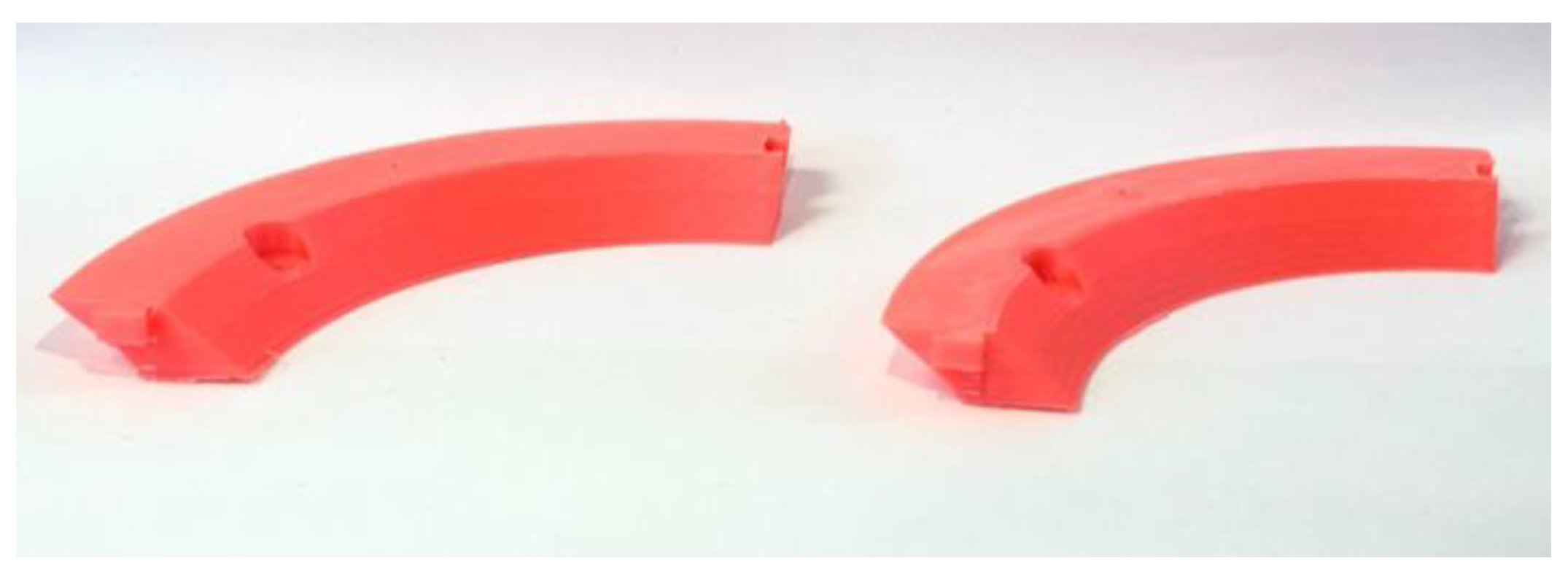

4.2.2. Speaker Ring

- Print speed: 100mm/s

- Generate support: yes

- Build plate adhesion: brim

- Infill: gyroid

- Ironing: enabled

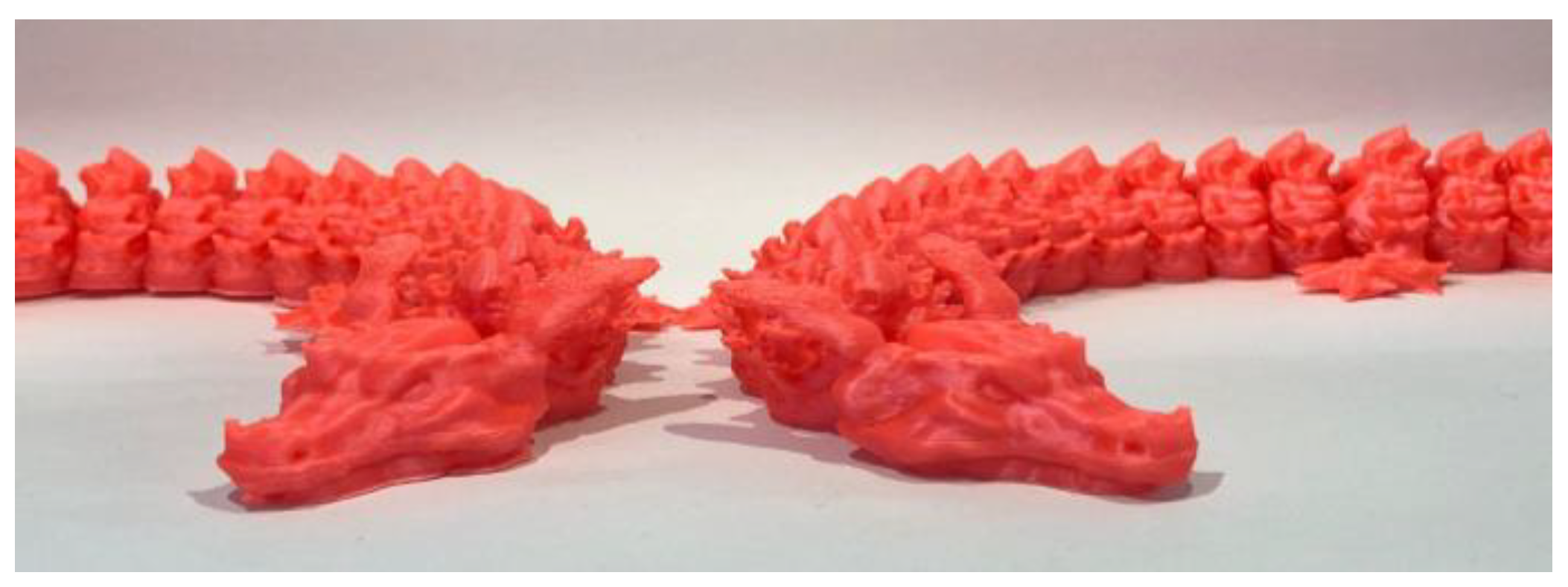

4.2.3. A Complex 3D Object (Articulated Dragon)

- Print speed: 100 mm/s

- Generate support: yes

- Build plate adhesion: brim

4.3. Limitations of Our Testing

- Try more nozzle sizes and types, we stuck with only 0.4 mm nozzles

- Try more materials besides PLA and see if the performance is any different with other common materials like PETG or ABS

- Try PLA from a multitude of manufacturers, as it could have an impact on maximum print speed or printing times

- Try multiple printer configurations like Core XY or Delta printers, we only tested on a bed slinger type of printer

- Try different slicer options or settings to print faster or better quality parts

- Try different extruder hotends that could melt plastic better or worse than ours

5. Conclusions

References

- Abbasi, M.; Váz, P.; Silva, J.; Martins, P. Head-to-Head Evaluation of FDM and SLA in Additive Manufacturing: Performance, Cost, and Environmental Perspectives. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.N.; Ishak, M.R.; Mohammad Taha, M.; Mustapha, F.; Leman, Z. A Review of Natural Fibre-Based Filaments for 3D Printing: Filament Fabrication and Characterisation. Materials 2023, 16, 4052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bed Mesh. Klipper 3D Printer Firmware. Available online: https://www.klipper3d.org/Bed_Mesh.html (accessed on January 13, 2024).

- Configuration checks. Klipper 3D Printer Firmware. Available online: https://www.klipper3d.org/Config_checks.html (accessed on January 14, 2024).

- Determining maximum Volumetric Flow Rate. Available online: https://ellis3dp.com/Print-Tuning-Guide/articles/determining_max_volumetric_flow_rate (accessed on 14.01.2024).

- Doicin, C.V.; Ulmeanu, M.E. Quantitative Network Design Analysis in a Multimodal Transportation Company Serving the Additive Manufacturing Industry, U.P.B. Sci. Bull. Bull, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ghinea, M.; Agud, M.; Bodog, M.; Agud, M.A. Pneumatic cylinders controlled by two different controllers, Arduino and MyRIO: An educational approach, International Journal of Education and Information Technologies, 2022, 15, 110-120.

- Glass Transition Temperatures of PLA & PETG available on: https://all3dp.com/2/pla-petg-glass-transition-temperature-3d-printing/ (accessed on , 2025). 11 January.

- Hui, D.; Imbalzano, G.; Kashani, A.; Ngo, T. D.; Nguyen, K. T. Q. Additive manufacturing (3D printing): A review of materials, methods, applications and challenges. In Composites Part B: Engineering, Editor Hui, D., Feo L.; Publisher: Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Iacob, M.C.; Popescu, D.; Alexandru, T.G. Printability of Thermoplastic Polyurethane with Low Shore Hardness in the Context of Customised Insoles Production, U.P.B. Sci. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Input shaper tuning examples and field data. Available online: https://www.reddit.com/r/klippers (accessed on July 23, 2025).

- Ismail, L.S.; lupu, C.; Alshareefi, H.; Luu, D.L. Design of PID Controller for Nonlinear Magnetic Levitation System Using Fuzzy-Tuning Approach, U.P.B. Sci. Bull., Series C, 2022, 84(2), 45-62. 84(2).

- Kantaros, A.; Soulis, E.; Petrescu, F.I.T.; Ganetsos, T. Advanced Composite Materials Utilised in FDM/FFF 3D Printing Manufacturing Processes: The Case of Filled Filaments. Materials 2023, 16, 6210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinematics. Klipper 3D Printer Firmware. Available online: https://www.klipper3d.org/Kinematics.html (accessed on January 16, 2024).

- Klipper PID Tuning - How To Guide. Available online: https://www.obico.io/blog/klipper-pid-tuning/, (accessed on April 8, 2024).

- Kristiawan, R.B.; Imaduddin, F.A.; Dody, U.; Arifin, Z. A review on the fused deposition modeling (FDM) 3D printing: Filament processing, materials, and printing parameters, Open Engineering, 2021, 11(1), 639-649.

- MainSail web interface for Klipper. Available online: https://docs.mainsail.xyz (accessed on day month year).

- Mhatre, S.; Nair, R.; Thakare, O.; Gund, A.M. Implementation Of PID Controller Using Arduino Microcontroller. IJSART.

- Nguyen, A. Hard Real-time Linux on a Raspberry Pi for 3D Printing. Master’s thesis, San Jose State University, 2022.

- PID controller implementation using Arduino. Microcontrollerslab. Available on: https://microcontrollerslab.com/pid-controller-implementation-using-arduino/ (accessed on , 2024). 13 January.

- Pressure Advance. Klipper 3D Printer Firmware. Available online: https://www.klipper3d.org/Pressure_Advance.html (accessed on January 15, 2024).

- Resonance Compensation - Klipper Documentation. Available online: https://www.klipper3d.org/Resonance_Compensation.html (accessed on July 23, 2025).

- Resonance.py – Input shaper definitions. Available online: https://github.com/Klipper3d/klipper/blob/master/klippy/extras/resonance.py. (accessed on July 23, 2025).

- Resonance Compensation. Klipper 3D Printer Firmware. Available online: https://www.klipper3d.org/Resonance_Compensation.html (accessed on January 14, 2024).

- Reverson, F.Q.; Domingos da Silveira, G.; Francassi da Silva, J.A.; Pereida de Jesus, D. Understanding and improving FDM 3D printing to fabricate high-resolution and optically transparent microfluidic devices. Lab on a Chip. 2021, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Speaker Adapter Ring 5.25 to 6.5 inch [3D Model]. Available online: https://www.thingiverse.com/thing:3467433. (accessed on March 30, 2025).

- Saikat, C.; Shankar, C. A multi-criteria decision-making approach for 3D printer nozzle material selection. Reports in Mechanical Engineering,.

- Singh, T. R.; Seering, W. P. Preshaping Command Inputs to Reduce System Vibration, Journal of Dynamic Systems, Measurement, and Control, 1990b, 112(1), 76–82.

- Singh, T.; Vadali, J. Robust Time-Delay Control, Journal of Dynamic Systems, Measurement, and Control, 1993, 115(2B), 303–310.

- Singh, T.; Huang, T. Optimal Multiple-Mode Input Shapers, Journal of Dynamic Systems, Measurement, and Control, 1996, 118(4), 781–786.

- Tevo Black Widow 3D Printer Kit V3. Available online: https://www.3dprintersbay.com/tevo-black-widow-3d-printer (accessed on 20.01.2023).

- Thingiverse - XYZ 20mm Calibration Cube [3D Model]. Available online: https://www.thingiverse.com/thing:1278865. (accessed on 18.05.2024).

- Thingiverse - articulated flame dragon [3D Model]. Available online https://www.thingiverse.com/thing:5337105. (accessed on 11.04.2024). (accessed on 11.04.2024).

- The Best ABS Print & Bed Temperature Settings available on: https://all3dp.com/2/abs-print-bed-temperature-all-you-need-to-know/#i-5-hot-end, (accessed on , 2024). 21 November.

- Vaughan, J.; Singh, T.; Chow, M. Enhancing the robustness of time-delay control, in Proceedings of the American Control Conference (ACC), Portland, OR, USA, 2005.

- Vaughan, J.; Singh, T. Robust time-delay filters for flexible systems, Journal of Dynamic Systems, Measurement, and Control, 2004, 126(2), 255–261.

- Wei, X.; Zhang, S.; Sun, L.; Zhao, X.; Sun, M.; Yu, R.; Zhou, X.; Li, Y. Geometric Accuracy and Dimensional Precision in 3D Printing-Based Gear Manufacturing: A Study on Interchangeability and Forming Precision. Polymers 2025, 17(3), 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhow, P.; Qi, F.; Hu, Y.; Chen, L.; Chen, Y. Numerical Simulation of Factors Affecting the Weight Distribution Uniformity of Vibrating through Materials, U.P.B. Sci. 2024. [Google Scholar]

| Scheme . | Vibration Reduction | Print Quality (Ghosting) | Execution Delay | Notes |

| ZV | Basic | Medium | Low | Simplest form, fast but limited |

| MZV | Good | Better than ZV | Slightly more | Compromise between reduction and delay |

| EI | Robust | Good | Moderate | Insensitive to resonance drift |

| 2HUMP_EI | Very good | Low ghosting | Higher | Better smoothing of high-frequency noise |

| 3HUMP_EI | Excellent | Minimal ghosting | Highest | Best for high-speed printers with complex resonance |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).