1. Introduction

Currently, experimental activities and educational resources have undergone several transformations that play a fundamental role in the field of educational science [

1,

2], especially in higher education in mechatronics, where experiments in laboratories are an indispensable part of the course so that students can obtain effective skills and practical experience [

4,

5,

6]. The use of laboratories is essential, but the use of these environments by students in educational institutions is becoming an obstacle, as machines and equipment are not always available to keep up with the technological demands of students and the market and are limited in quantity and time [

7,

8,

9]. However, educational institutions, teachers, and students seek tools to help the teaching and learning process [

10,

11]. One of the solutions is the use of remote laboratories with physical equipment because, with this type of access, it is possible to practice skills, improve experimental activities, and create environments using actual equipment and scenarios [

12].

The fundamental concepts of remote laboratories are as follows: According to Rodriguez-Calderón [

13], a remote laboratory is a technology composed of software and hardware that provides a real learning experience with remote access via the Internet. Verslype et al. [

14,

15] described remote labs as enabling students to evaluate and monitor the progress of experiments remotely, regardless of the availability of physical laboratories and equipment. Similarly, Orduña et al. [

16] defined remote laboratories as software and hardware tools that allow students to access actual university equipment. Zine et al. [

17] also highlighted that remote labs serve as educational resources that extend beyond the capabilities of virtual laboratories. Moreover, Vries and Wörtche [

18] emphasized that remote laboratories are natural laboratories where equipment and students are physically separated. In summary, remote laboratories are software and hardware tools that generate a real learning experience, granting remote access to physical experiments via the internet [

19,

20]. These tools offer several advantages, including equipment sharing between institutions [

6,

21], flexible scheduling [

22,

23], personalized learning experiences, and fostering self-discipline among students to complete tasks [

24]. However, most remote laboratories also present challenges, such as a lack of standardization, environments that fail to provide flexibility in developing experiments [

25,

26], and insufficient engagement and immersion between students and experiments [

27,

28]. Remote laboratories play a crucial role in student education [

29], as they facilitate learning experiences that involve high-value technological equipment and provide access to multiple resources, including experimental monitoring and correction. To enable the tracking of student experiments, this system employs the principles of digital twin technology. Furthermore, artificial intelligence algorithms will be integrated with the digital twins of the experiments to automate the correction process in the teaching and learning environment within remote laboratories.

To understand digital twin (DT) technology, its definition is presented by several authors: Kuvshinnikov, Kovshov, and Korchagin [

30] describe digital twins as a set of heterogeneous data processed by software tools. Wang et al. [

31] explained that digital twins capture real-world data across various disciplines, quantities, scales, and probabilities. Prohaska and Kennes [

32] define the DT as a continuous connection between a real object or process and its digital counterpart, with data transferable in both directions. Espinosa and Escamilla [

33] emphasized the concept of dynamic replicas of the real environment for achieving a DT, whereas Mihai et al. [

34] highlighted DT as an emerging and transformative technology with significant potential for the future of industries and society.

This concept is particularly relevant for integrating physical machines into the virtual world [

35,

36], facilitating interactions and analyses in mechatronics applications [

37], replicating and executing the behavior of experimental peripherals [

38], emulating environments across various domains [

28,

39,

40], and democratizing and enhancing learning processes in educational platforms [

41,

42].

Artificial intelligence (AI) is an intelligent machine designed to perform tasks that typically require human intellect, including voice recognition, natural language processing, learning, and problem-solving capabilities [

43]. With advancements in AI, particularly generative AI utilizing large language models (LLMs), applications have expanded across various domains.

AI has significantly elevated technological support in education, fostering greater interactivity and innovation. It has assisted educators in managing their teaching processes more effectively while serving as an educational tool that offers students a wide array of learning opportunities [

44,

45].

According to Lundström, Maleki, and Ahlgren [

46], an LLM is an advanced machine learning tool that leverages text understanding and generation to assist in various tasks, particularly in the educational field. Nevertheless, within the education sector, applications involving images have benefited from computer vision combined with convolutional neural networks (CNNs), which aid in object detection in classrooms and laboratories and in image classification for educational activities.

In this work, digital twins and remote laboratories are the technological elements contributing to the evolution of the teaching and learning process in the field of mechatronics. However, the challenge of this proposal lies in how to perform the automatic correction of students' experiments in remote laboratories. Consider the following scenario: a student wants to verify whether their activity is functioning correctly. This typically depends on the professor’s evaluation to check the performance of what the student has accomplished in the didactic experiment. However, what if the student is studying at 3 a.m.? Who will correct this activity? Or who will assist the student in solving the activity?

Given this scenario, the fundamental idea was to utilize digital twin technology as a base tool capable of capturing data from the professor’s experiment (Professor’s digital twin) and the student’s experiment (Student’s digital twin) and then compare these data to perform automatic corrections. In this way, the student’s experiment can be evaluated at any time. While digital twins facilitate data capture in remote laboratories, it will also be necessary to leverage convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and the GPT chat API to assist in correcting experiments by analyzing the images and data captured during the experiment's execution.

A CNN is a neural network with convolutional, pooling, and fully connected layers designed for processing two-dimensional data and is typically used for feature extraction, such as object detection and image classification [

40,

47,

48,

50]. Generative AI, with ChatGPT being the most famous example, is a tool with the potential to enhance higher education by improving and facilitating educational experiences for both students and professors [

51,

52,

53,

54].

Therefore, these two technologies assist in the correction of experiments in remote laboratories in the system of this work, given that technology-assisted correction has already proven to be helpful in distance education school management platforms (e-learning) and that it leaves a digital trail where it is possible to transform the data generated during experiments into information [

55,

56].

The article is organized as follows: Section II presents related works involving the topics of digital twins in remote laboratories and learning assessment systems. Section III outlines the project design. Section IV details the components developed and implemented in the system. Section V describes the procedures of the experiments conducted to evaluate the implementation of the correction system in remote laboratories within the field of mechatronics and their results. Section VI discusses critical aspects of the system, and Section VII presents the conclusions drawn from the study.

2. Related Work

The works related to this research were divided into two groups: works related to the themes of digital twin technologies and remote laboratories and the themes of correction in the educational field and automatic assessments in education using generative AI or CNNs.

-

A.

Digital Twin in Remote Laboratories

In Fernández, Eguía, and Echeverría [

57], the article describes the use of the digital twin to validate the control system of a robotic cell. It compares conventional and study methods using the developed digital twin in a remote laboratory. A robotic cell and a PLC (programmable logic controller) were used for this system, where a digital model of the robot with the PLC was created. The OPC-UA protocol was employed to collect and apply information from the digital model to the physical model. The students were then divided into groups to evaluate the actual and virtual processes. The virtual model was observed to be highly beneficial for taking the first steps in the proposed teaching activity. However, the realism of commissioning raised doubts among the students, making the actual model essential for the final validation of the process. This research did not store student data to display educational progress or provide feedback on whether the proposed activity was executed correctly.

Jungwirth et al. [

58] presented the results of an analysis of mechatronics education programs in Austria and Taiwan, showing how increased digitization and smart manufacturing applications have driven the evolution of these courses. Based on this analysis, the article details the development of a digital twin demonstrator designed to teach and motivate students to use digitization and digital twin technology to demonstrate practical applications in mechatronics education. This experiment used low-cost materials, making them accessible to anyone interested in assembly. Both countries' courses utilized this demonstrator; however, if a professor wanted to assign a current activity, its assessment would rely on manual verification by the professors. An automatic correction system with feedback for the students would be highly beneficial.

In Guc, Viola, and Chen [

38], a remote laboratory was developed as a complementary teaching and learning tool for the ME-142 mechatronics course at the University of California. This study employed MATLAB/Simulink to control the position and speed of a motor as an experiment for the students. The experiment aimed to encourage students to design their experiments by the end of the course. The theoretical framework created by Viola and Chen [

38] was used as a reference for the construction of the digital twin. Through developing the digital twin, students can upload their experiments to a remote-access web application and use it whenever needed. The most notable aspect of this work was the use of the framework for developing the digital twin. However, no record of the resulting history is stored in remote laboratories, and no corrections have been made to the experiments conducted.

In Martínez, Sanchez, and Chávez [

59], a digital twin was developed for the commercially available CNC mini-milling machine 3018 PRO. This milling machine was incorporated into a remote laboratory, with its virtual model created via the Unity platform. Data exchange between the physical and virtual environments was facilitated through the Modbus protocol, and a PLC was implemented to acquire the milling machine’s electrical signals, communicating with the Codesys environment. This setup created elements to streamline communication and utilize the developed platform. This work featured high-precision simulation characteristics, as Unity allows the integration of calculations that enhance movement accuracy, closely replicating real-world behavior in the virtual environment. However, this study has not yet been evaluated on an educational platform and lacks tools for students to conduct academic activities.

In Mušič, Tomažič, and Logar [

3], a distance-learning course on programmable logic controllers was implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic. A combination of tools was employed to maintain a strong focus on practical experiments, including simulation, remote access to available laboratories, and interactive sessions with the instructor. In this course, students could conduct their experiments remotely and use the digital twin provided by Festo's Cirus software. This allowed the students to view a 3D virtualization of the experiment and practice their activities. However, the course did not offer automatic activity correction, as the students had to visually determine whether their experiment was successful because of their judgment or with the tutor’s support.

In Riveros et al. [

60], a digital twin of a large-scale industrial process is presented, which is available to students to analyze both the physical and virtual models, allowing error verification to be implemented. This research uses teaching plans to conduct experiments with students. An excellent system was developed, which has its digitization developed in the Unity engine and has a virtual reality model for better visualization by students. Students can verify the operation by digitization or viewing cameras in the laboratory, but it is up to the teacher to verify whether their experiment is correct.

-

B.

Student assessment in laboratories

Fletcher et al. [

61] presented the implementation of a remote laboratory as part of a computer network course offered in a massive open online course (MOOC) format. This lab was implemented online because of the excessive costs of a physical laboratory and allows multiple simultaneous classes, enabling students to execute network applications via simulators and physical equipment through remote access without the need to install specific software. This tool also allows automatic evaluation, simplifying the professor's workload, as it enables the control of individual parameters defined for each student during the course. For corrections, activity configurations are managed through .json files containing the necessary information to initiate the student's task, and a Python program is responsible for verifying whether the activity is correct and generating personalized reports and feedback.

In Bachiri and Mouncif [

62], a system was implemented to assist in correcting questions in massive open online courses (MOOCs). These courses are characterized by many students, requiring substantial effort for corrections. While objective questions facilitate automatic correction, open-ended (subjective) questions pose a significant challenge in such courses. This research aims to address the issue of automatic correction for open-ended questions. Since these courses involve participants worldwide, translation into English is required before AI processing. To achieve this goal, a learning management system was developed to integrate natural language processing, using artificial intelligence techniques to make MOOCs more engaging and personalized. For this purpose, language standardization was applied, and the SQuAD v1 database—containing approximately 100,000 questions generated from Wikipedia articles—was used. Through AI algorithms, responses are automatically corrected for MOOCs. Using AI algorithms for text analysis helps verify the correctness of the responses. In the system proposed here, data are obtained from digital twins and can be transformed into strings for AI analysis.

In Nalawati and Yuntari [

63], a study is shown that applies text mining techniques using the Ratcliff/Obershelp algorithm to determine the similarity value between two strings; that is, even in the case of open (subjective) responses between the students' responses, it is possible to obtain a similarity with the key to the teacher's response. In this research, the Ratcliff/Obershelp algorithm was used with sixth-grade students, considering the tolerance of the student's error rate. The research presented an average accuracy of 91.00% regarding the correction rate. For this purpose, an application in Python was developed for the students to use as a response platform. The Ratcliff/Obershelp algorithm can help in this proposal by verifying the teacher's digital twin data similarity with the student's digital twin data. This use can be evaluated within the proposal.

Hassan et al. [

64], a study motivated by the pandemic period, demonstrated the LMS (laboratory learning management system), a comprehensive laboratory learning system with management capabilities. The LLMS provides numerous services for conducting assessments and automatic corrections, including storing student behavior data via artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms. This system detects whether students are experiencing difficulties and whether they are performing experiments based on mouse dynamics (click counts and movements) through AI learning. It also features a virtual assistant that describes experiments using audio, text, and video support. While the system supports remote access with virtual experiments, it has not been applied to remote laboratories involving hands-on activities.

In Dias, Purnamawati, and Idkhan [

65], an e-learning web system with an automatic response scoring application for writing correction was developed. This system was based on natural language processing (NLP), with the text being processed. The system operates based on a base response, frequency calculations, and weight assignment and seeks to calculate the similarity of the student's responses. After this writing was corrected, the students' scores were entered. This method can analyze data collected from the digital twin to identify similarities between the teacher's and the student's responses.

Tulha, Carvalho, and Castro [

66] presented an implementation of a project proposing the development of an educational platform with remote laboratories that utilize data mining based on learning analytics interventions called LEDA (laboratory experimentation data analysis). This approach applies to association rules and clustering techniques using learning data, including clicks, the number of controlled components, and the time spent on the activity. For this purpose, a data mining technique focusing on association rules and clustering was employed, specifically the Apriori algorithm. When students perform a didactic activity, the Apriori algorithm can gather information about their progress, highlighting their strengths and weaknesses. Additionally, the K-means algorithm was used to focus on individual student experiences. These algorithms can be utilized to process the data collected from the digital twin implemented in this work. Furthermore, as image capture is implemented, the grouped data can be assessed to evaluate behavior during data mining.

A summary of the characteristics of the related works can be found in

Table 1 - Comparative analysis of related works.

3. Concept Design

The design of this paper will be based on the development of a didactic twin capable of learning the experiments developed by the teacher, where these experiments will be conducted in remote laboratories in the mechatronics area and automatic correction at the time of use by the students. To learn the experiments, this didactic twin uses the concepts of digital twin technology, taking as a reference the framework developed by Viola and Chen [

36], in addition to works that presented essential characteristics about the acquisition and processing of data in experiments with digital twins, among these studies, we mention the bidirectional digital twin presented by Protic et al. [

67], where this research presents a digital model that can be sent to two cobots of different architectures and the prediction of failures shown by Classens, Heemels and Oomen [

68]. It was also used as a reference for the work of Mershad, Damaj, and Hamieh [

15], which used IoT sensors and modules to evaluate laboratory experiments with the help of learning management systems (LMSs).

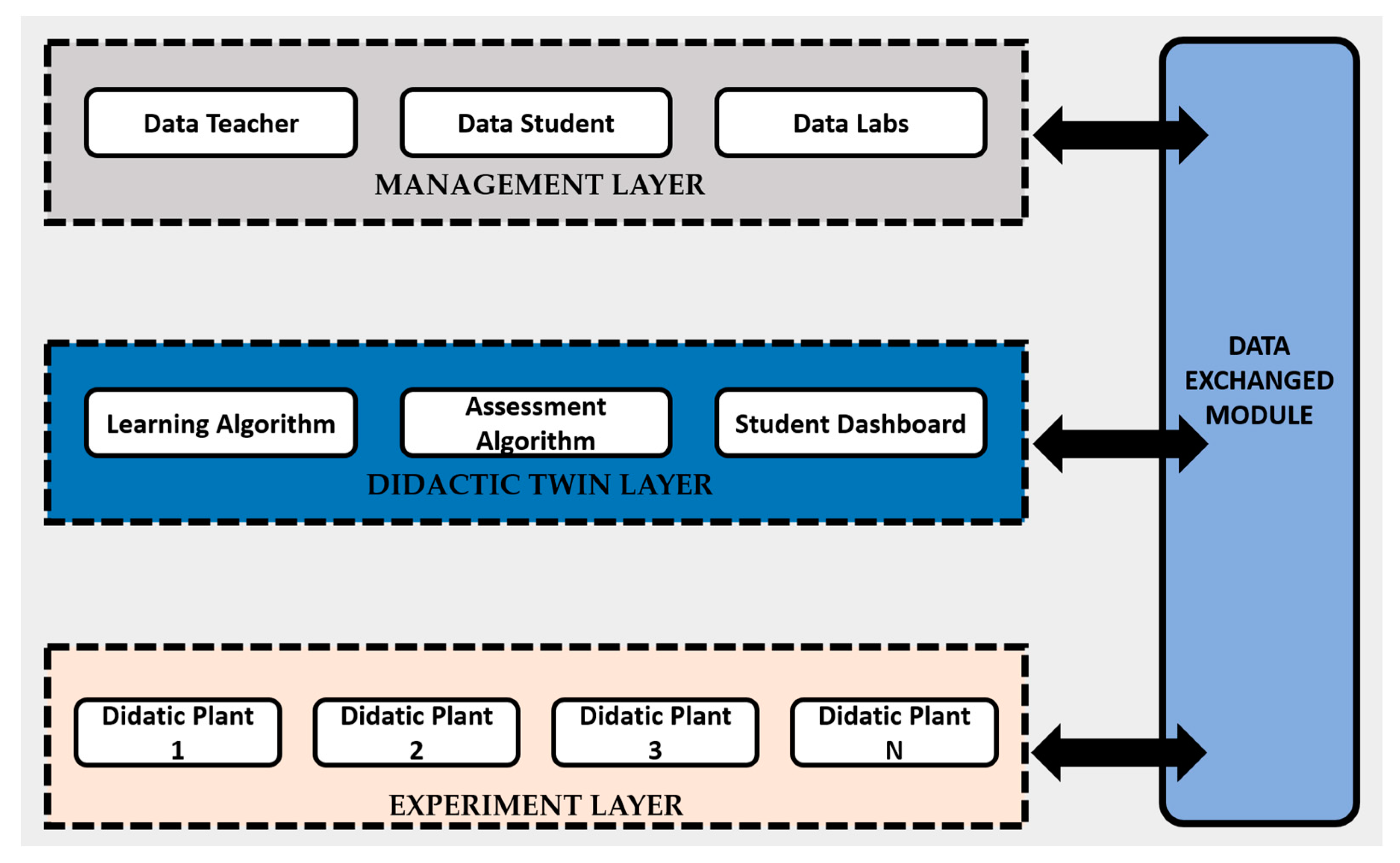

The design of this system is divided into three layers: an experimental layer, a didactic twin layer, and a management layer, as shown in

Figure 1.

In the following subsections, all the layers that are part of the design of this system are presented.

3.1. Experimental layer

The experimental layer is the layer of the system where all the experiments are located and have didactic plants as the main component, as the plants will have the following elements:

Its primary function is to acquire data from didactic experiments and send them to the data exchange module, as well as to indicate the availability of the Remote Laboratory for executing the student's experiments.

It controls the didactic process by receiving signals from the input elements of the experiment through the controller's input module. After these signals are received, they are processed, and the processing results are transmitted to the output module to act on the output elements of the didactic experiment.

These are processes designed to develop students' technical skills through practices that combine theoretical and practical concepts. The experiments that make up the didactic plant in the field of mechatronics generally have inputs and outputs that transmit and receive control signals from the controller. The professor can design these experiments according to the technical and academic needs of the student's training.

The camera of the didactic plant serves as a tool to verify whether the didactic experiments are correct or incorrect according to the activity proposed by the professor. This image-based evaluation aids in correcting the activities proposed by the professors and helps the students identify areas for improvement in their programming and studies.

3.2. Didactic Twin Layer

The didactic twin layer is responsible for processing and organizing the data received from the didactic plant, storing the professor's experimental data, and correcting the student's activities. This layer is divided into three modules:

When the teacher executes the didactic experiment, a module is responsible for exchanging data with Data Exchanged. It stores the professor's digital twin and learns the experiment being performed with the help of generative AI. Additionally, it saves this learning as a proposed activity model for the student.

The module is responsible for searching for the experimental pattern, being the teacher's digital twin, and comparing it with the student's execution, called the student's digital twin, and returning the student's activity response. The image collected by the experimental camera at the time of the evaluation is applied to the classifier to verify whether the response pattern at the end of the activity is correct, with the response of a CNN classifier trained to provide this result.

The module is responsible for showing the response data obtained to the student, in addition to graph views and the experimental history.

3.3. Management layer

The management layer is the system layer responsible for providing a registration area and storing data on students, teachers, experiments, and remote labs. This layer is divided into three modules:

The module is responsible for registering, storing, and managing all teacher data, such as experiments created, corrections made, registered laboratories, and activity models proposed for students.

The module is responsible for registering, storing, and managing student data, such as experimental history, errors, labs accessed, and progress.

The module is responsible for registering, storing, and managing laboratory data, such as registered labs, educational institutions, and access points.

3.4. Data Exchanged Module

The Data Exchanged module is responsible for exchanging data between layers and storing data in the database.

4. System implementation

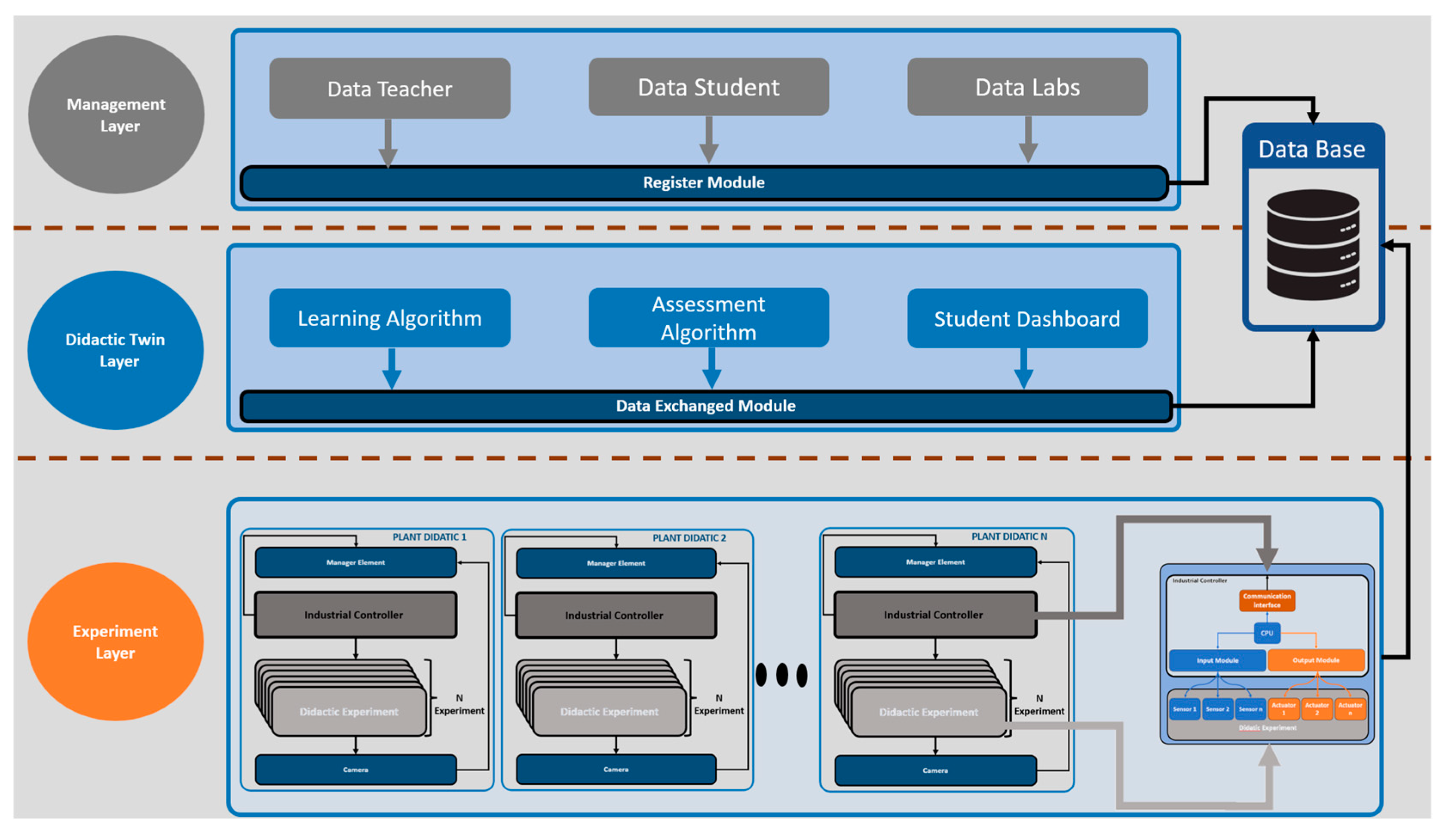

The system was implemented to help with correction activities in remote mechatronics laboratories and will follow the design shown in the previous section of the work. Therefore, a detailed architecture is presented to help us understand the system flow. This detail is presented in

Figure 2.

The following subsections present all the implementations of this experimental correction system in remote laboratories in the mechatronics area.

4.1. Implementing the Experimental Layer

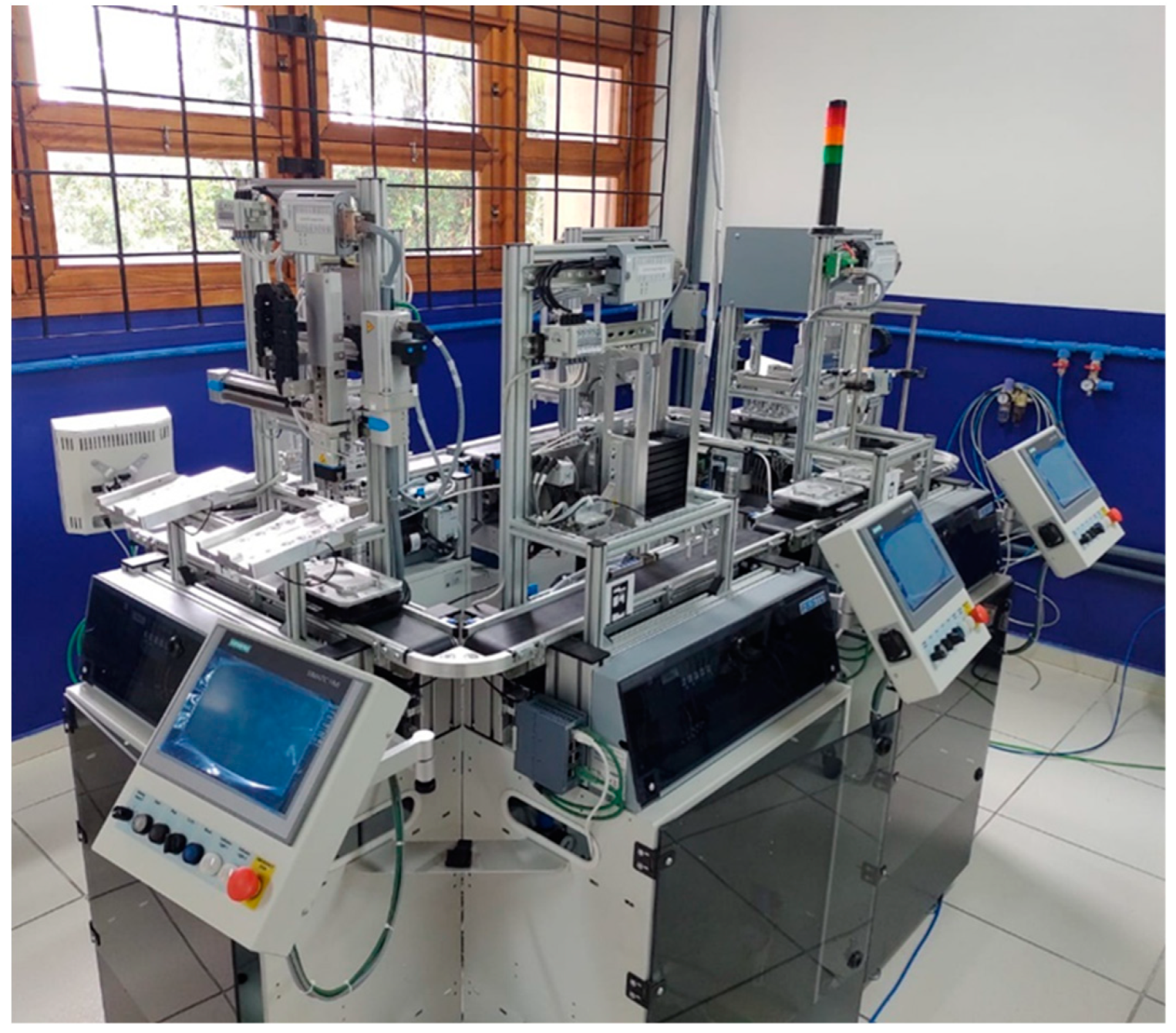

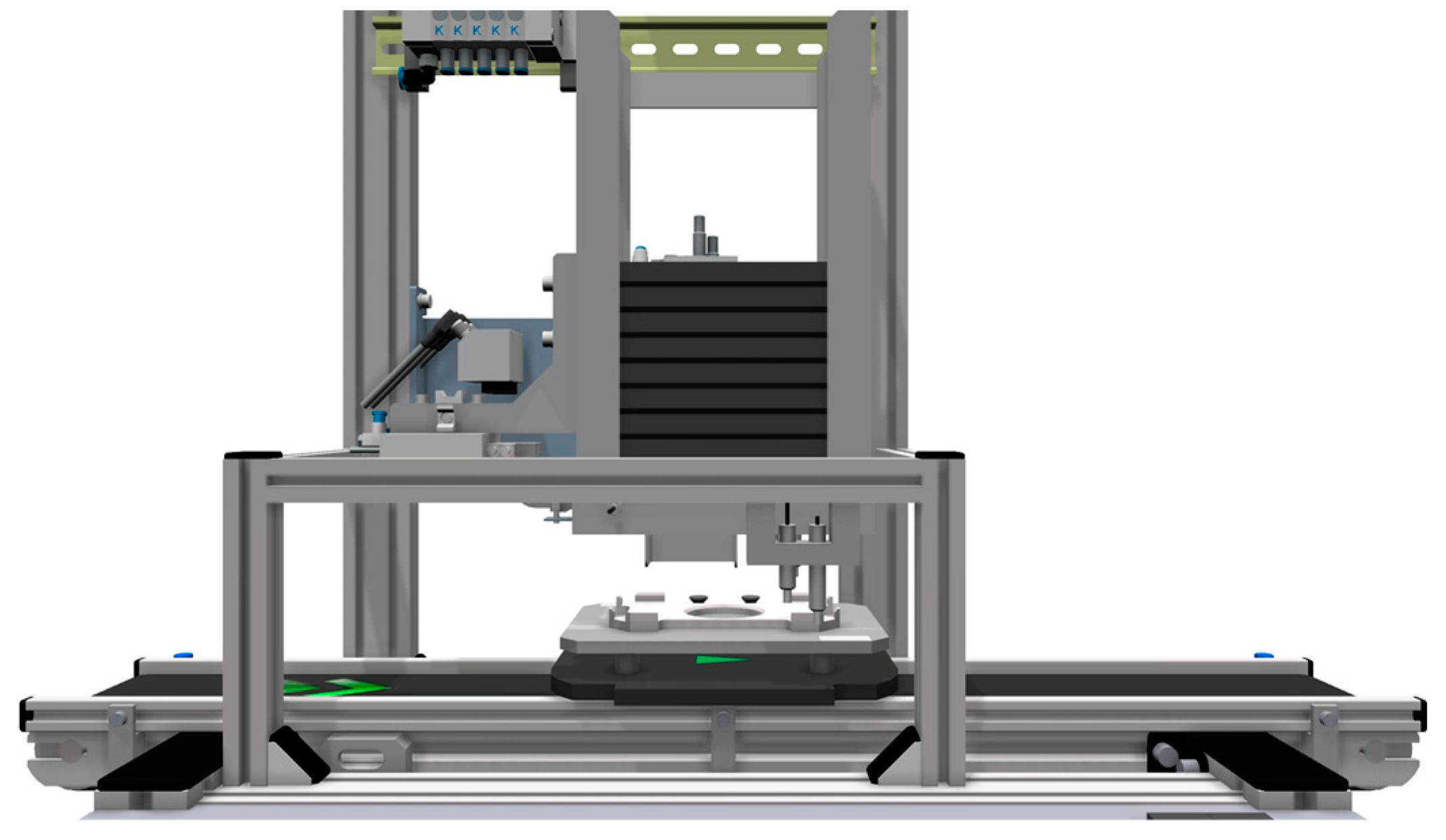

The experiment layer was implemented via the teaching plans of the Industry 4.0 laboratory of the Federal University of Amazonas, specifically the teaching plans of the CP-LAB line of the company Festo, where a remote access structure was created to use these plans as Remote Laboratories.

Figure 3 shows the teaching plan that was used and its actual components.

The implementation of the elements of the teaching plan will be presented according to the conception of the work where the teaching plan has the following elements:

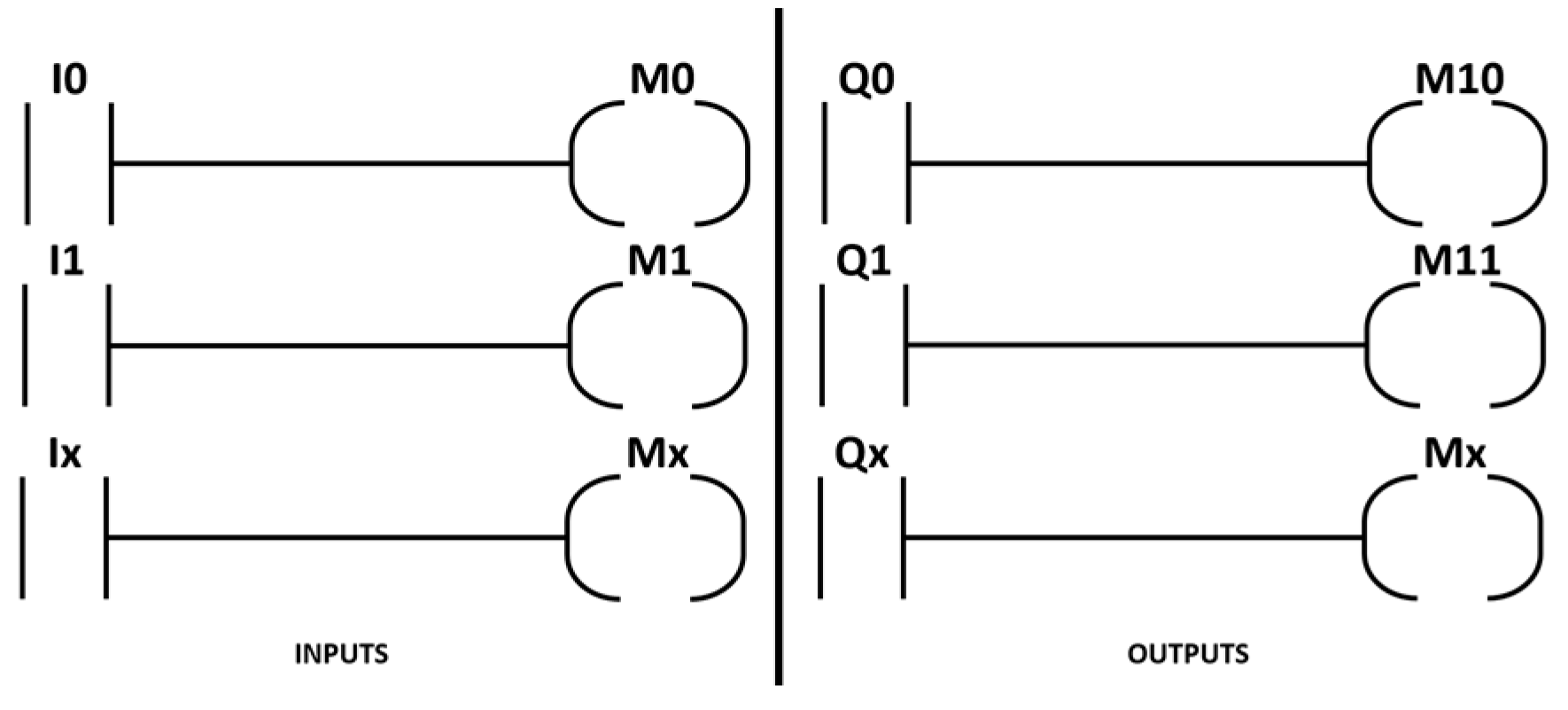

In implementing this system, the industrial controllers can be programmable logic controllers—PLCs, microcontrollers, or computers. Nevertheless, in this teaching plan, the controller will be the Siemens S7-1500 PLC, where a mask for Ladder language was developed to facilitate the capture of data sent to the management element regardless of the communication protocol used.

Figure 4 shows the mask used when the controller is a PLC because, with this device, the activity code generated by the student is not modified in its logic. This mask takes all the PLC inputs and outputs and takes their signals to known memories, where these memories can be configured to share their states through the communication protocols existing in the PLC. For example, in the PLC of this implementation, the OPC-UA protocol was used to share the memory data.

Figure 4 addresses Ix and Qx, representing the possible inputs and outputs in the PLC.

The student's program is inserted into the remote laboratory controller through the management layer in the Lab DATA element, where the student uploads it to the area of each experiment, which can be in ladder mode for PLCs or Python in the case of PCs and microcontroller platforms.

A plant called Mag_front was used to implement this system, which is part of the CP_LAB line. The Mag_front plant inserts the rear part of the cell phone into the teaching plant's transport cart. This plant has sensors and buttons as input elements of the PLC, and the conveyor belt, pneumatic actuators, and signaling devices are output elements to be activated by the PLC.

Figure 5 shows the virtual drawing of the teaching plant.

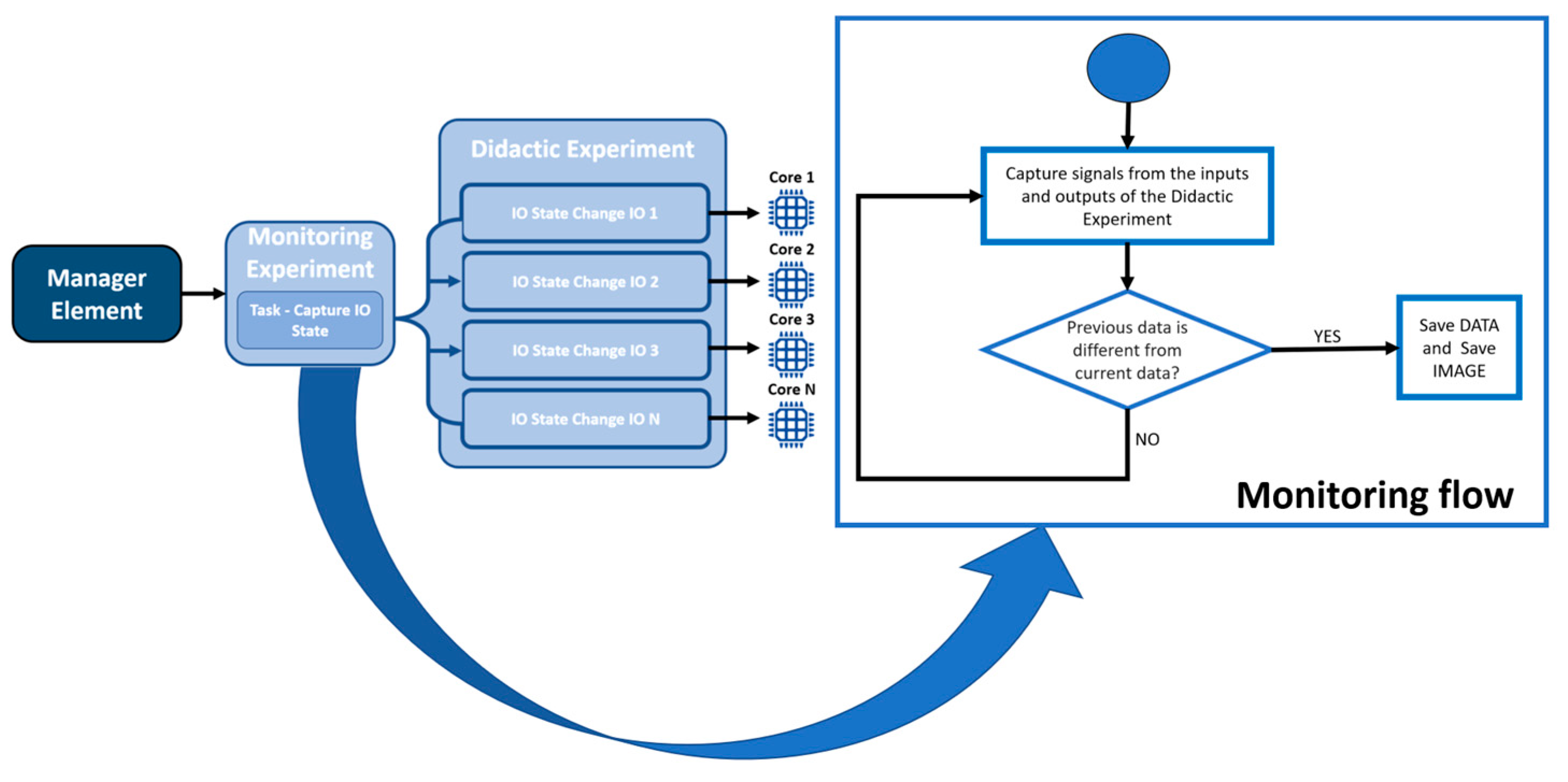

The management element was implemented to monitor and capture experimental data through the communication protocol selected when registering information in the management layer. In the case of this educational experiment, OPC-UA was chosen to capture the data. The management element is a software that was implemented to run on the computer in the remote laboratory where the experiments are being conducted, checking the data that were modified during the execution of the experiment. The architecture of this element works by waiting for changes in the state of the inputs and outputs of the educational experiment. For each modification, the data were captured effectively, and the execution of the management element was divided into multiple processes, which resulted in increased monitoring speed to capture all the data.

Figure 6 shows the capture methodology designed to meet the rapid state changes in an experiment and the monitoring flow of the management element software.

The manager element stores the information in the temporary database in the form of steps according to the changes taking place in the didactic experiment. In this work, the definition of a step is the storage of the status of all the inputs and outputs used in the didactic experiment, and each change in one of the inputs and outputs is considered a new step and, again, the element stores the step.

The camera of the teaching plant was implemented with a webcam connected to the computer of the remote laboratory. This camera is activated by the didactic twin layer and by the management element at each step of the change in state of the experiment. The image of this camera can also be viewed by the student at any time to check the execution of the experiment conducted by his/her programming. For example, in this application, it can be seen if the back of the cell phone has come down from the magazine in the transport car.

4.2. Implementing the Didactic Twin Layer

To implement the didactic twin layer, a web application was developed in Python via the Streamlit framework, where this application can be accessed by the student to conduct their experiments. This application was developed in the following modules:

4.2.1. Learning Algorithm Module

To implement learning about how experiments work, the teacher must perform the didactic experiment according to the expected solution for the student's task. When the experiment is executed by the teacher, the learn didactic experiment button must be clicked so that the algorithm responsible for learning begins execution. The algorithm developed in this module is divided into two parts:

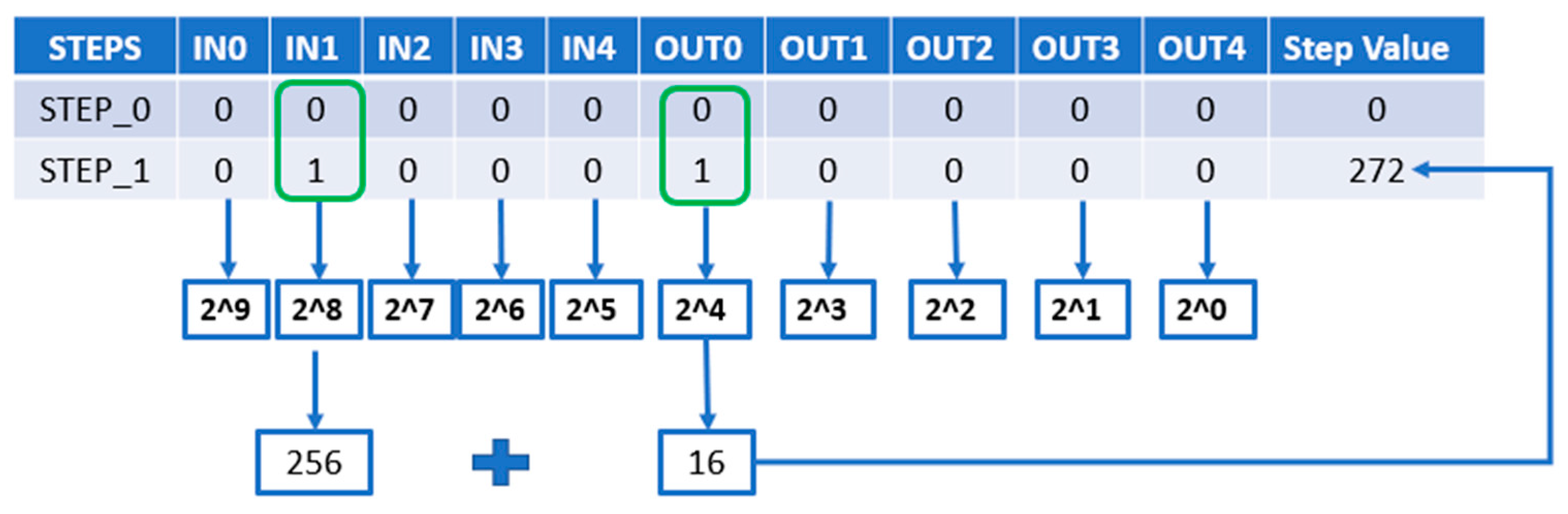

The preprocessing element was implemented to organize the data in the database, where it has a temporary table fed by the management element, and when the experiment is running, the data are passed to the learning algorithm module, each change in state that occurs, and the entire step must be stored.

Figure 7 shows the green markings to show the change in the state of IN1 and OUT0, generating a new step and the methodology for organizing the data of the input and output signals implemented in the preprocessing element.

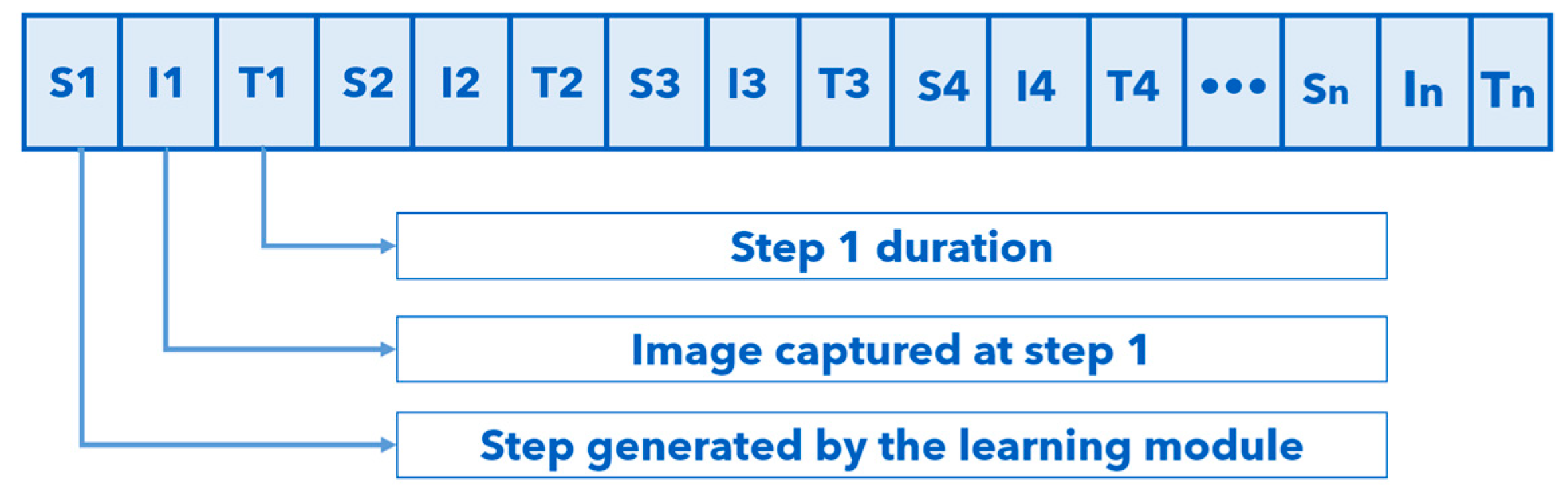

Figure 7 shows the steps received in the database with the states of all the inputs and outputs of the experiment. For each step, weights are calculated so that each step has a value. This value aims to facilitate the search for a pattern for the teaching experiment. Based on the transformation from binary to decimal, this method was chosen because the digital inputs and outputs of the experiment become a large binary number in which zero represents the inactive state and one represents the active state of the system. Therefore, for each step captured, the preprocessing element transforms it to an integer (

Figure 7), facilitating the learning of the experiment by the generative AI. As the steps are generated, the preprocessing element stores the time between the previous step and the new step, in addition to a photo being captured to complete the digital twin of the teacher's experiment. The preprocessing element only finishes capturing data when it reaches a timeout or when the experiment pattern element has a response.

Figure 8 is the result of the execution of the preprocessing element that stores the experimental data. These data were found by repeating steps or by associating the path with the correct answer. S stands for step, where the step is formed by the transformed integer of each input and each output; that is, it goes from input I1 to In and Q1 to Qn. When the step occurs and is different from the previous step Sn, an image is captured, called in (image), where n represents the step number and Tn is the time that the step took to execute, where n is the number of steps that are occurring.

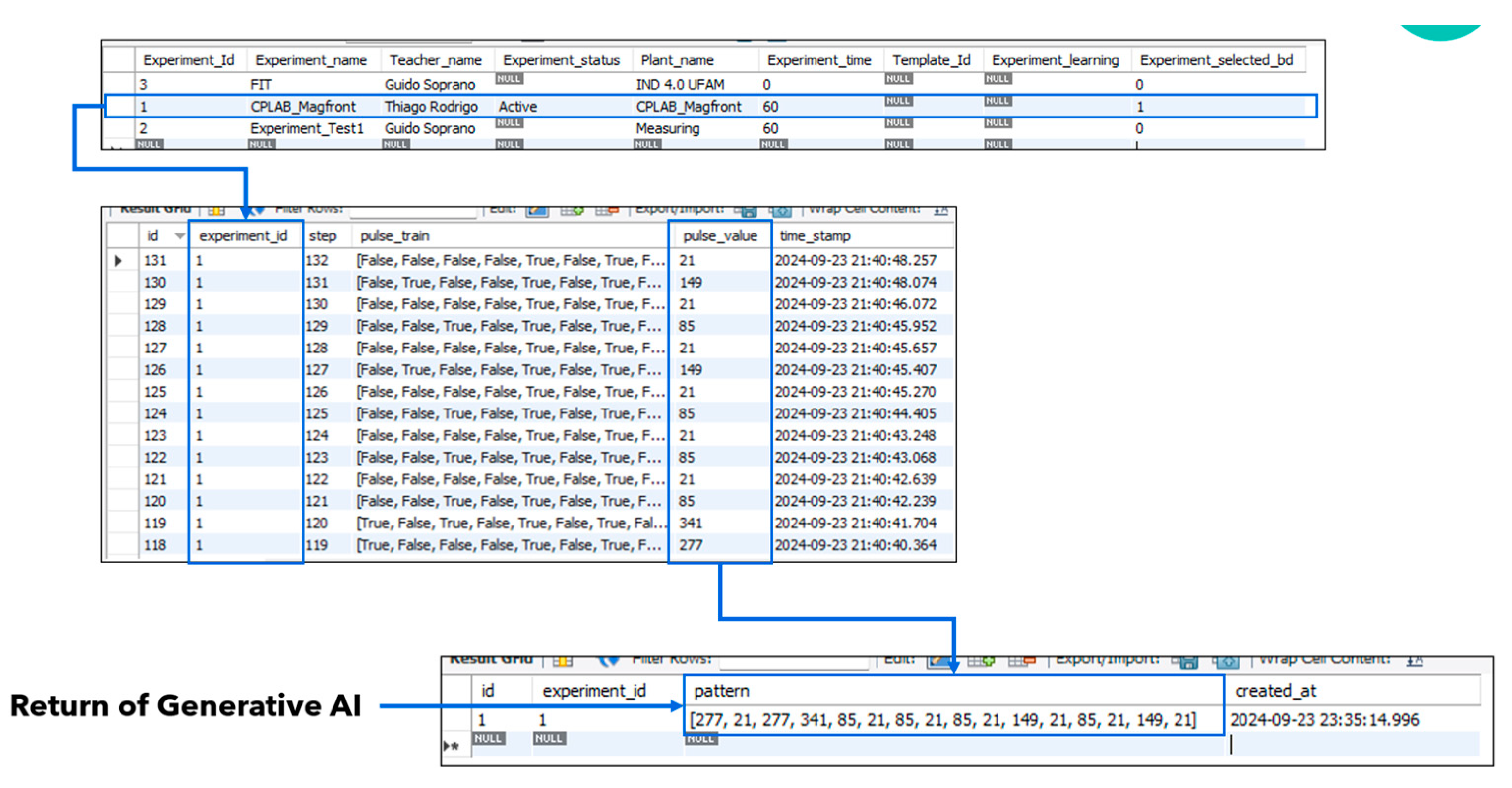

The experiment pattern element was implemented to take the data organized by the preprocessing element and insert it into an API to request help from the generative AI, which will show the main sequence that occurred most often in the experiment and the variations according to the functioning of each activity performed by the teacher. The generative AI algorithm only receives the numbers from each step because it performs well in returning the standard sequence and its variations. When a pattern from the experiment is returned, this pattern is called the digital twin of the teacher's experiment. For the experimental pattern to be returned, the following question was passed to the generative AI API: what is the main pattern of the sequence below? Before this question, a numerical sequence that has a pattern will be passed.

Figure 9 shows the data that were organized by preprocessing and the return given by the API via the generative AI.

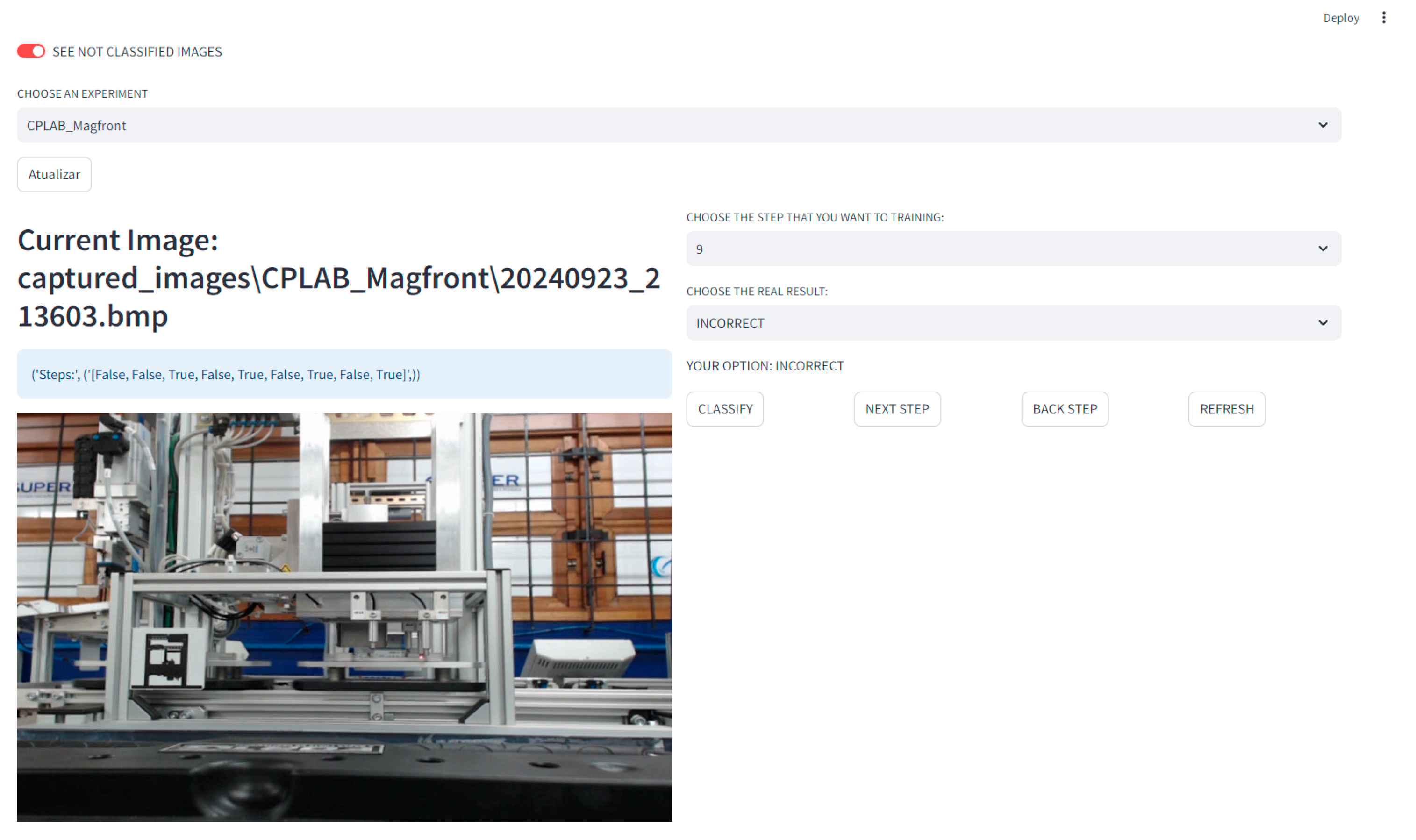

In this element, the teacher also selects images to train a classifier of the results of the student's activity. A classifier was implemented via the YOLOv8 architecture to serve as a double check on the correctness of the experiments, but for the classifier to be trained, the teacher must classify the photos according to his or her experience of right or wrong.

Figure 10 shows the screen for the teacher to classify the images that were trained automatically.

4.2.2. Assessment Algorithm Module:

The evaluation algorithm module was developed to monitor and evaluate the students’ experiments based on the teacher's digital Twin. This application was divided into two elements:

The assessment experiment element occurs when the student starts running the experiment. The student's program is inserted into the experiment by clicking the Start My Experiment button, and the application begins checking the differences between the teacher's and student's solutions. However, to obtain the student's solution, it is necessary to use the same process as the teacher's experiment: capture the data from the management element, pass it through the learning algorithm, and finish with the pattern returned by the generative AI API. In this correction process, the digital twin data from the teacher's and the student's experiments are initially saved in .txt files to be later uploaded to the database. This procedure occurs because of the speed of the input and output signals when executed in the experimental process. These files also serve as a backup in case of latency in communication with the database and are saved on the local machine of the remote laboratory. This application works with three files: one being the correction template (digital twin of the teacher for that experiment), the current correction file (student experiment), and a response file. Number 1 (one) is stored for equal steps in the response file, and 0 (zero) is stored for each difference; these files are uploaded to the database in table form.

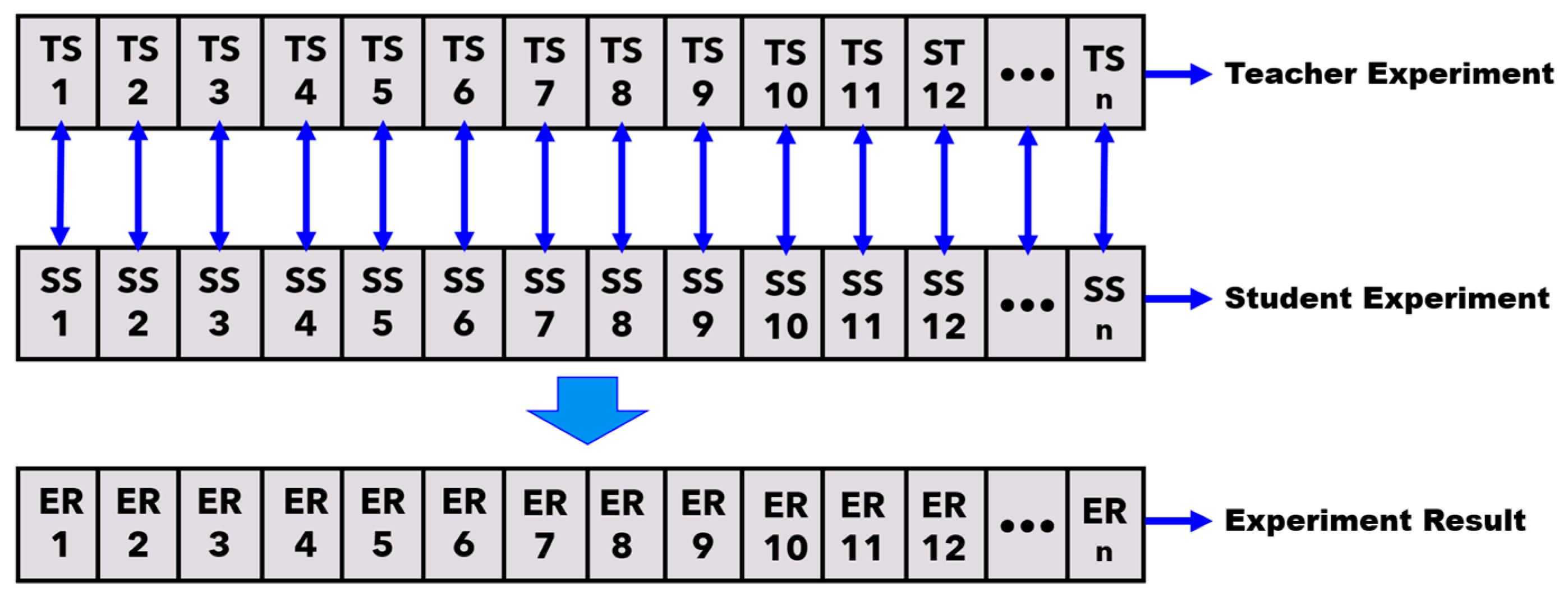

Figure 11 shows how the experimental correction methodology was applied, where TS stands for the teacher step, SS for the student step, and ER for the experimental result; all steps are integers that were taken from the AI generative return pattern and were compared only, and the response was inserted into the database table to be available for the next element.

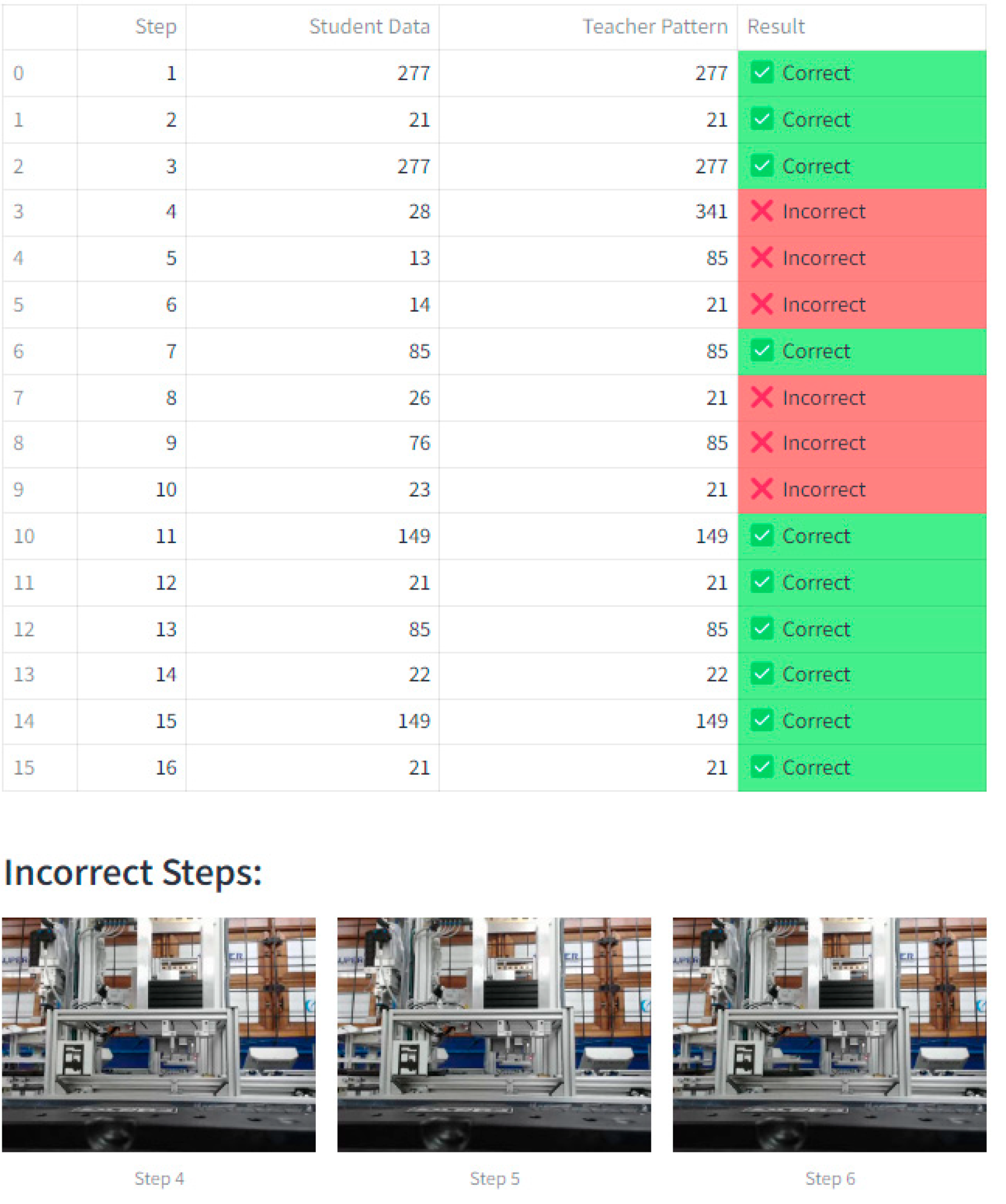

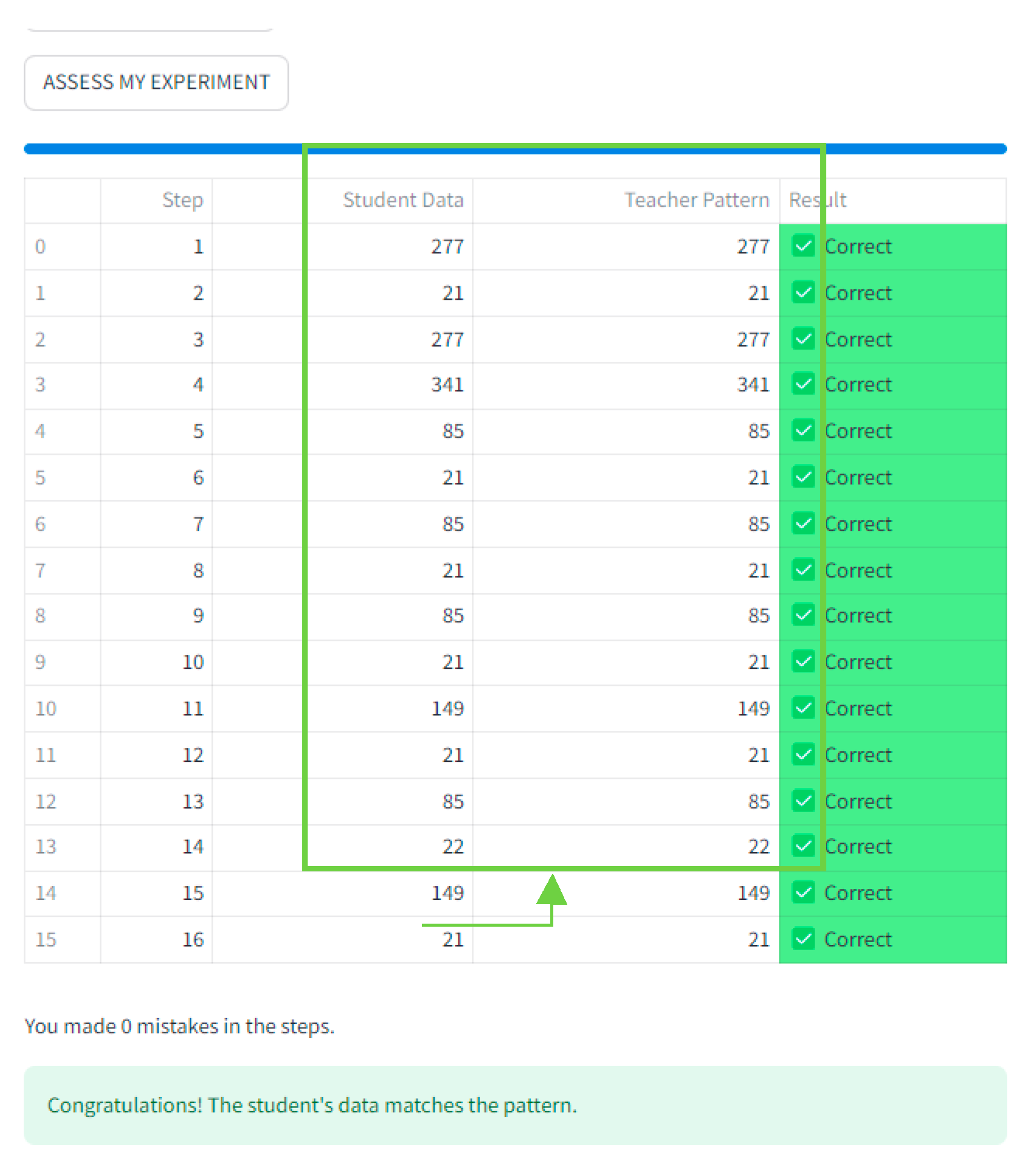

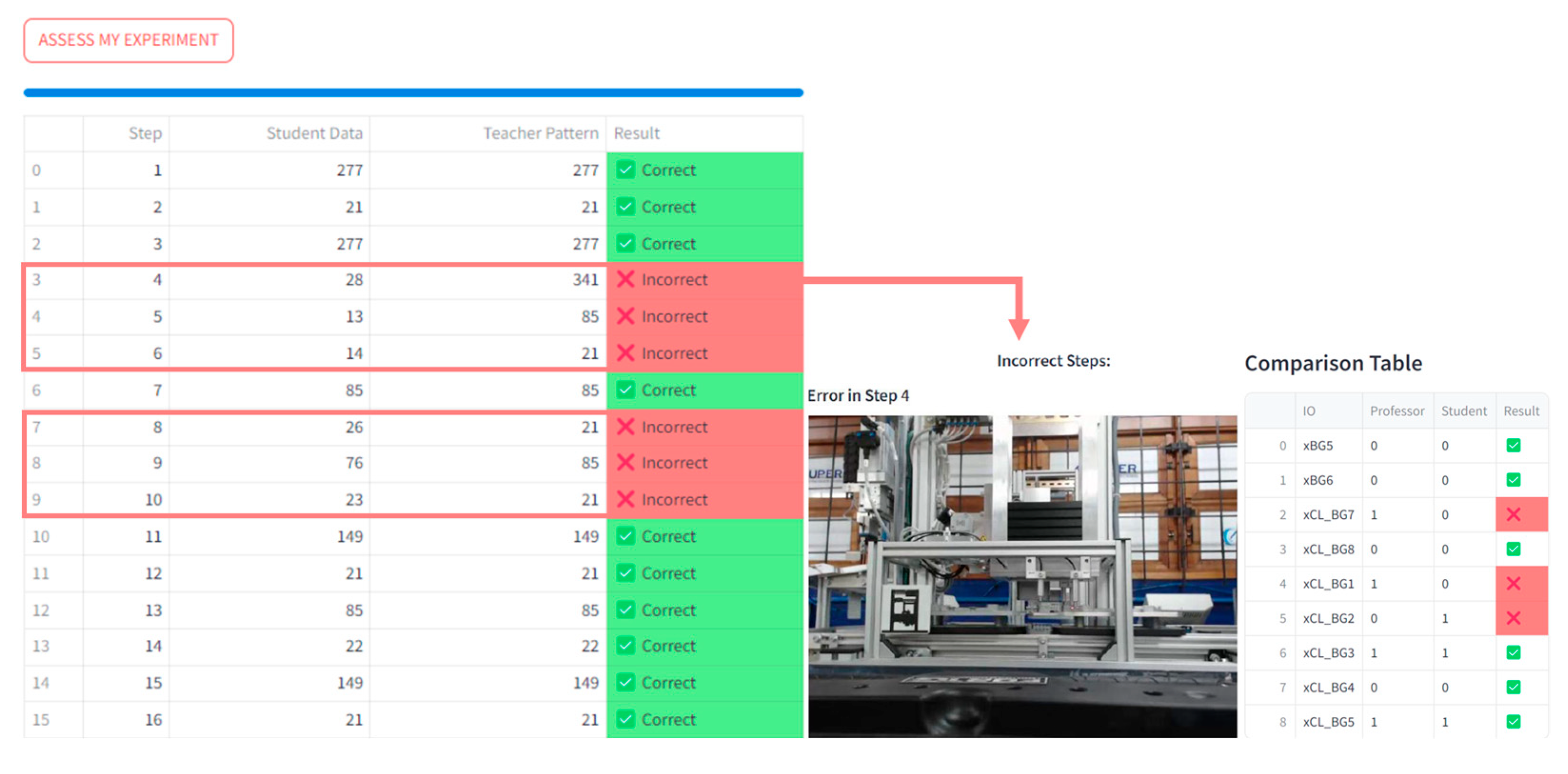

The Assessment Result element was implemented to come into action when the student clicks on the Assess My Experiment button. Then, the experimental response data is collected and prepared to show to the student. First, this element checks the response table created by the assessment experiment, capturing the differences between the experiments and organizing the images of the steps according to the correctness of the experiment. If there are errors, the images of the incorrect Steps are retrieved and presented to the student as a form of learning. In addition, red is inserted for each incorrect step in the response table shown to the student. If there are correct answers, green is inserted for each correct step in the response table.

Figure 12 shows the student response screen created by the assessment results element. It presents a table with each step, with a column with the student's and teacher's data and the colors and words correct and incorrect as a result, in addition to presenting the steps in which the student got wrong.

This correction becomes complete when the formation of the didactic twin is finished. This didactic twin stores the characteristics of the student's digital twin, the execution images of the student's experiment, and the student's monitoring data. This didactic twin can evolve into a comprehensive learning report for the student, which will be incredibly useful for the course teacher or educational institution's decision-making. All this information will be available on the Student Dashboard module.

This module was implemented to meet all requests from modules part of the didactic twin layer to access database information. All methods were implemented to select, update, insert, and delete operations on the system database tables.

4.2.3. Student Dashboard Module:

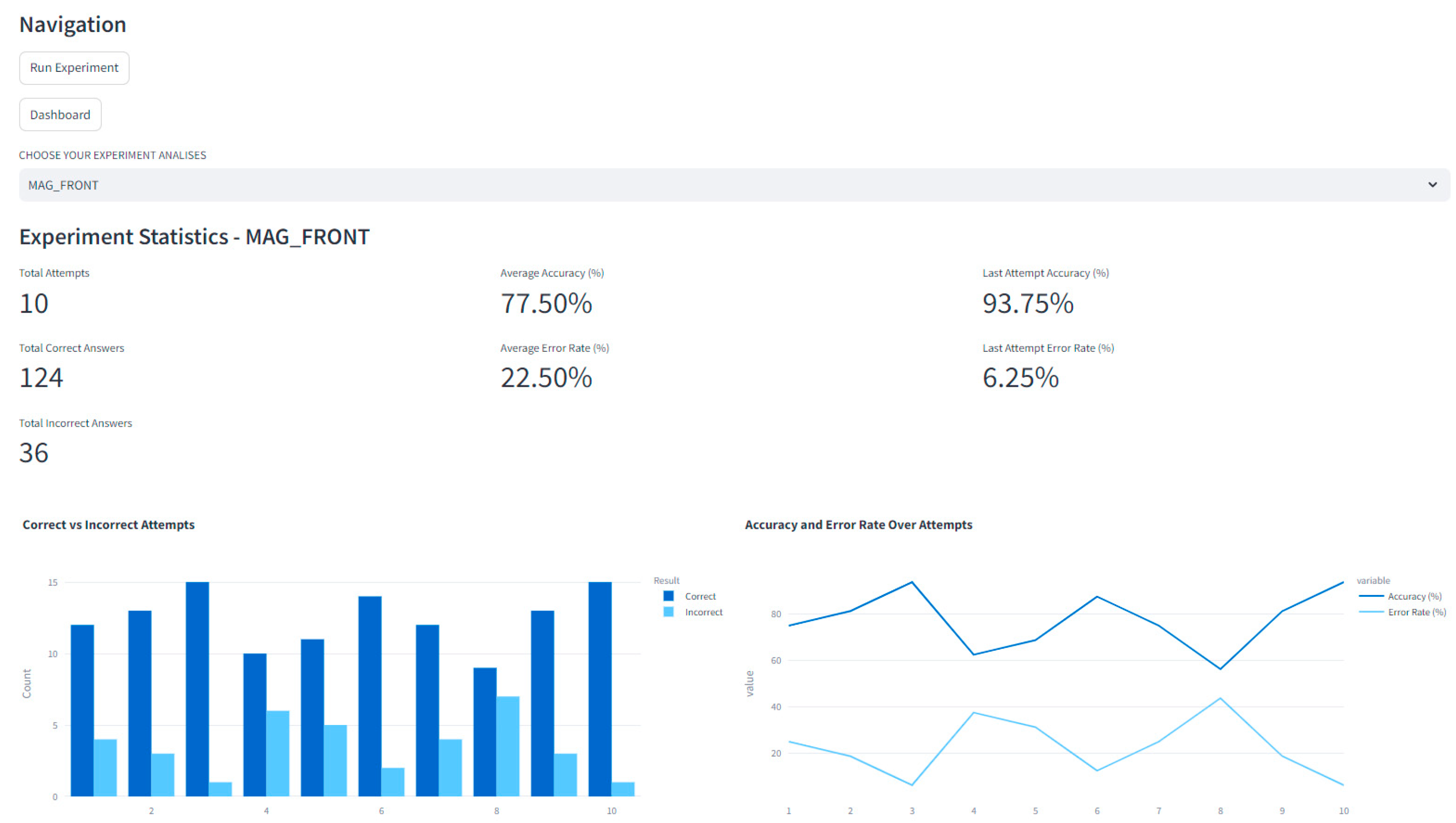

The Student Dashboard module was developed to monitor students' experiments, showing their performance in each experiment, their profile, and their history of progress in the activities indicated by the teacher. For each experiment, information was made available through graphs created to present the student's performance, showing the attempts of the experiment, the number of errors, which Steps the student managed to get right in all attempts, and the accuracy of the last experiment.

Figure 13 shows the graphs available to the students.

4.3. Implementing the Management Layer

An application comprising the Web interface and the didactic twin layer was developed to implement the management layer. The teacher and the student can also access it, but its primary purpose is to manage all the registrations and updates in the system. Therefore, this application was developed with the following modules:

4.3.1. Data Teacher Module:

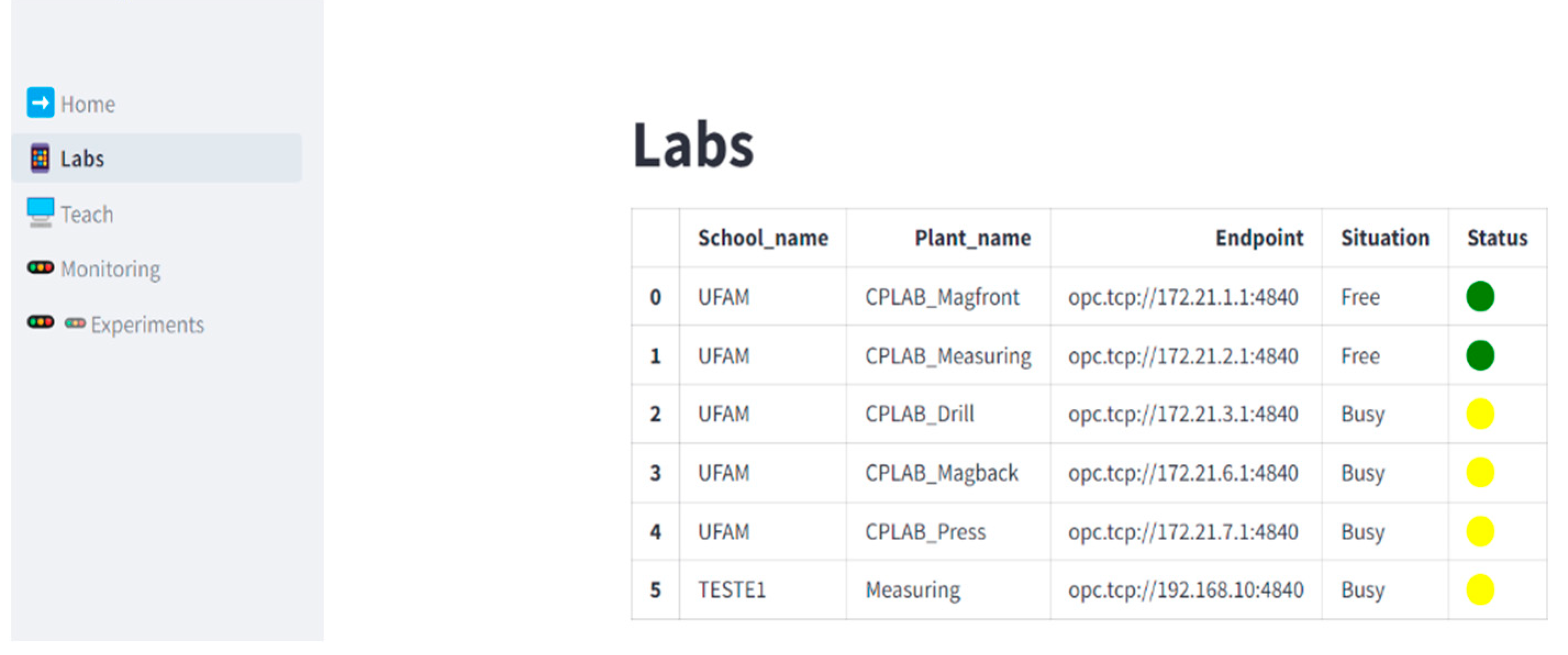

The Data Teacher module was developed to register and manage information that is the teacher's responsibility, such as data on educational institutions, laboratories, and their experiments. These data are part of the teacher's profile. From the registration, it is possible to check the status of each laboratory registered in this system.

Figure 14 shows the screen of the laboratories registered by the teacher and their respective statuses, where green means it is ready for use, yellow means it is currently occupied, and red means that the laboratory is not in operation. For each laboratory, a table is created with the information stored in the database. For example, each laboratory is linked to an educational institution and has an access point to establish communication between the laboratory and the laboratory.

4.3.2. Data Student Module:

The Data Teacher module was developed to register and manage the information that is the student's responsibility. First, the student must enter their personal information to enter the system and have a registered profile. After registering, the student can check the inputs and outputs of each laboratory and the status of each input and output.

4.3.3. Data Labs Module:

The Data Teacher module was developed to register and manage laboratory-specific information, such as the laboratory's name, operating hours of the experiments, how many experiments there are, type of communication protocols, and description of the experiments.

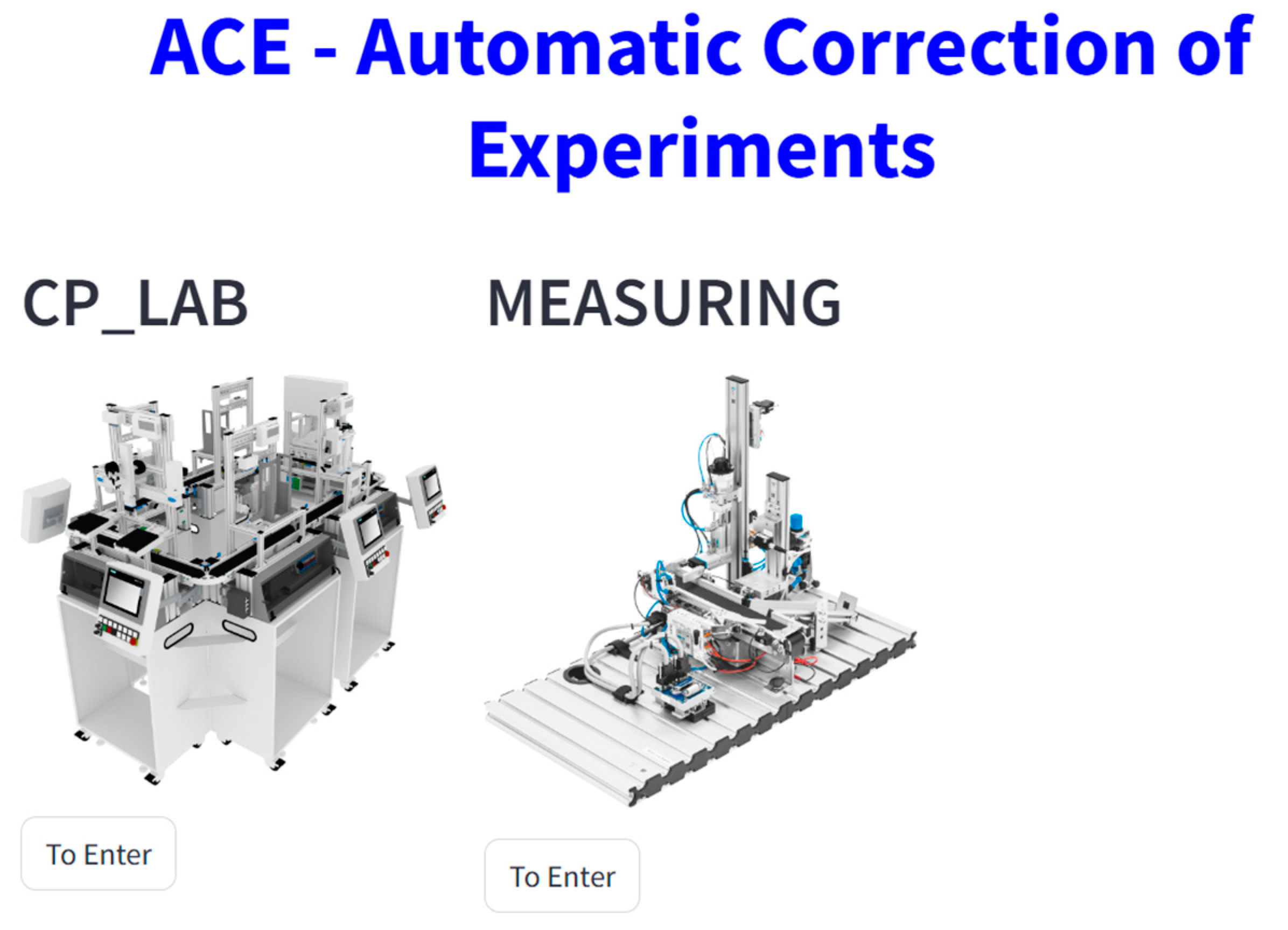

Figure 15 shows the home page of the laboratories registered and available for remote experiments.

5. Results and tests

The scenario created to evaluate this system followed the following steps:

A teaching plant from the Industry 4.0 Laboratory of the Federal University of Amazonas called CP-LAB was used. This plant has six modules that form a teaching process for producing cell phones (

Figure 4). Only the process of inserting the back cover of the cell phone was used to evaluate this system.

Figure 5 shows a scenario called CPLAB_Magfront. This experiment uses a conveyor belt to carry the transport pallet, a parts storage unit, a mechanism to carry out production, and sensors to indicate the start and end of the process conveyor belt. The back cover is inserted into the parts storage unit to begin the cell phone assembly process.

Through the management layer, the teacher registered a teaching plan in the system called CPLAB_Magfront. This registration inserted the inputs and outputs of the teaching plan, communication endpoint, and experiment. The teacher created the experiment Teste_magfront. Among the registered information, it is necessary to pay special attention to whether the laboratory endpoint and the inputs and outputs were inserted correctly for the proper functioning of the activity developed by the teacher. After registration, the teacher must execute the proposed experiment and click the learning experiment button.

Neste momento, a aplicação do elemento gerenciador inicia no acompanhamento do experimento para realizar a captura dos passos, que verifica as mudanças de estado de cada entrada e saída cadastrada para salvar os passos da execução. A cada passo salvo é coletado o tempo do passo anterior para o próximo passo, além de ativar a aplicação de captura de imagens. Esse aprendizado formar o digital Twin do experimento do professor e as informações foram armazenadas num arquivo .txt e no banco de dados como template do experimento do professor para do Teste_magfront.

At this point, the application of the management element starts monitoring the experiment to capture the steps, which checks the changes in the state of each registered input and output to save the execution steps. With each saved step, the time from the previous step to the next step is collected, in addition to activating the image capture application. This learning forms the digital twin of the professor's experiment, and the information is stored in a .txt file and the database as a template for the professor's experiment for Teste_magfront.

The results of the tests performed will be presented according to the functioning of the two programs to verify whether the system can learn the experiment according to the teacher's proposal, forming the digital twin of the teacher's experiment and if the correction of the student's experiment performed by the system is correct in comparison with the experiment conducted by the teacher. Initially, the learning of the teacher's experiment was verified; in this learning, two APIs were evaluated, one from Gemini and another from the GPT chat. Both methods did not yield reliable results when the input and output values were entered directly to find a pattern; at this point, they were evaluated numerous times, and all had the same behavior. Then, it was necessary to input the preprocessing element so that the numbers could be transformed into integers and later applied to the APIs. This methodology detected no errors in finding a pattern for the experiment via the GPT chat API. For the correction of the students’ experiment, it was verified that the comparison was satisfactory because the learning was correctly executed.

The learning was carried out via the teacher's program, so the correct program was executed to simulate the student's program, remembering that the teacher must register the activity by informing the student of the activity's instructions; for example, the treadmill must be turned on, the stop actuator must be activated when the transport car reaches the stop, and the back cover of the cell phone must be injected and then continue with the cover.

Figure 16 shows that the student data and teacher pattern columns are the same in all steps, so the experiment is correct.

Since the incorrect program was made for the same experiment, the standard that already existed for the activity of this experiment was used, so the incorrect program was executed to simulate the student's program, remembering that the experiment was already registered, and the same experimental statement was used. Then, the incorrect program was executed; this operation was programmed so as not to inject the back cover of the cell phone.

Figure 17 shows the incorrect steps and the images with each incorrect step of the student's experiment, where Steps 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, and 9 are incorrect, and the comparison table shows which input or output is erroneous at step 4. In this example, the sensors were not activated because there was no command to inject the back cover of the cell phone.

6. Discussion

The results of this work are essential for verifying that it is possible to integrate technologies such as digital twins, convolutional neural networks, and generative AI to correct didactic experiments in the mechatronics area. With digital twin technology, the capture of experimental data needs to be performed as quickly as possible because of the speed of the actuators and sensors, so the application of the management element was developed in multiprocessors to reduce the latency time in data capture. The methodology was a critical point because, in the initial tests, the input and output signals were sent directly to the generative AI API, and the return was not satisfactory, so the process of using integers to find the experimental pattern was necessary. With the pattern found by generative AI, it is possible to compare what was developed by the teacher with the student's experiment. It was verified that the tests performed met the correction of didactic experiments with digital inputs and outputs, but they were not evaluated with analog input and output experiments. Therefore, it is possible to perform these tests and investigate other experimental correction APIs via LLM for future work.

7. Conclusions

The system proposed in this article achieved its objective, as a test experiment was developed to simulate the students' programs, a correct program and an incorrect program that verified whether the architecture of this system could help in the automatic correction of experiments in remote access laboratories. This system was developed through layers—all layers communicated via a database. Nevertheless, this data exchange was essential so that the data from the experiments could be analyzed by algorithms that process the data acquired by the experiment layer and then processed by the didactic twin layer. The responses and support for these activities are in the management layer. In this work, a concept called the didactic twin was also created; this element is nothing more than each step of the experiment plus the duration of the step and an image at the time of the step. With the didactic twin, it was possible to automatically correct students' experiments by taking the steps of the experiment and transforming these steps into an easier way for the generative AI to find the pattern of the experiments, even if the experiment had more than one solution in the processes of the Mechatronics area.

The system developed is a proposal that aims to evaluate the result of an experiment and the entire path that the student developed to reach the definitive answer. Therefore, this architecture is a tool that helps us correct the teachers' experiments automatically. The functioning of this architecture with three layers facilitates understanding, helps in the organization of the experiments, and contributes to the evaluation process in the remote laboratories of the Mechatronics area. The digital twin of the teacher's experiment and the functioning of the student's experiment are compared to verify whether the correction is correct or incorrect. However, the teacher can still choose the most significant step of the correction to classify the experiment.

The significant contribution of this article was the development of a system capable of helping in the correction of experiments, and that avoids possible data in which the generative AI API finds a pattern; this pattern is the learning of the experiment and can always be used when the student is going to correct the experiments without the need for the teacher to be present to carry out the correction.

Acknowledgments

This work was performed as an activity related to a doctoral thesis in the graduate program of PPGEE-UFAM (Electrical Engineering Program of the Federal University of Amazonas - Brazil). The National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), the Federal Agency for Support and Evaluation of Graduate Education (CAPES), and FAPEAM (Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Amazonas) supported this research by providing financial resources through scholarships and fellowships.

References

- T. C. Caetano, C. C. Moreira, and M. F. R. Junior, "Computer-Aided Experiments (CAE): A Study Regarding a Remote-Controlled Experiment, Video Analysis, and Simulation on Kinematics," in IEEE Transactions on Education, vol. 67, no. 2, pp. 245-255, April 2024. [CrossRef]

- V. Young, S. Cho, C. Talley, R. C. Voicu, C. Tekes, and A. Tekes, "A Modular Control Lab Equipment and Virtual Simulations for Engineering Education," SoutheastCon 2024, Atlanta, GA, USA, 2024, pp. 717-721. [CrossRef]

- G. Mušič, S. Tomažič and V. Logar, "Distance Learning of Programmable Logic Control: An Implementation Example," 2022 29th International Conference on Systems, Signals, and Image Processing (IWSSIP), Sofia, Bulgaria, 2022, pp. 1-4. [CrossRef]

- A. Birk and D. Simunovic, "Robotics Labs and Other Hands-On Teaching During COVID-19: Change Is Here to Stay?," in IEEE Robotics & Automation Magazine, vol. 28, no. 4, pp. 92-102, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. J. D. Martínez, "Design Experience of Laboratory Practices in COVID Times.," 2023 Future of Educational Innovation-Workshop Series Data in Action, Monterrey, Mexico, 2023, pp. 1-5. [CrossRef]

- L. Kunzhe and I. Kholodilin, "Developing Virtual Laboratories for Understanding the Automation Course," 2023 Seminar on Electrical Engineering, Automation & Control Systems, Theory and Practical Applications (EEACS), Saint Petersburg, Russian Federation, 2023, pp. 208-213. [CrossRef]

- D. Krūmiņš et al., "Open Remote Web Lab for Learning Robotics and ROS With Physical and Simulated Robots in an Authentic Developer Environment," in IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, vol. 17, pp. 1325-1338, 2024. [CrossRef]

- V. Young, S. Cho, C. Talley, R. C. Voicu, C. Tekes, and A. Tekes, "A Modular Control Lab Equipment and Virtual Simulations for Engineering Education," SoutheastCon 2024, Atlanta, GA, USA, 2024, pp. 717-721. [CrossRef]

- A. Gampe, A. Melkonyan, M. Pontual and D. Akopian, "An Assessment of Remote Laboratory Experiments in Radio Communication," in IEEE Transactions on Education, vol. 57, no. 1, pp. 12-19, Feb. 2014. [CrossRef]

- V. F.de Lucena Jr., A. Brito, P. Gönner, N. Jazdi, “A Germany-Brazil experience report on teaching software engineering for electrical engineering undergraduate students,” 2006 Software Engineering Education Conference, Proceedings, pp. 69 - 76. [CrossRef]

- V. F. de Lucena Jr., J. P. de Queiroz-Neto, I. B. Benchimol, A. P. Mendonça, V. R. da Silva, M. Ferreira Filho M. “Teaching software engineering for embedded systems: An experience report from the Manaus research and development pole.” 2007 Proceedings - Frontiers in Education Conference, FIE 2007. [CrossRef]

- G. Carro Fernandez et al., "Mechatronics and robotics as motivational tools in remote laboratories," 2015 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Tallinn, Estonia, 2015, pp. 118-123. [CrossRef]

- R. Rodriguez-Calderón, "In-home laboratory for learning automation at no cost," 2021 IEEE World Conference on Engineering Education (EDUNINE), Guatemala City, Guatemala, 2021, pp. 1-4. [CrossRef]

- S. Verslype, L. Buysse, J. Peuteman, D. Pissoort, and J. Boydens, “Remote laboratory setup for software verification in an embedded systems and mechatronics course,” in 2020 XXIX International Scientific.

- K. Mershad, A. K. Mershad, A. Damaj and A. Hamieh, "Using Internet of Things for Automatic Student Assessment during Laboratory Experiments," 2019 IEEE International Smart Cities Conference (ISC2), Casablanca, Morocco, 2019, pp. [CrossRef]

- P. Orduña et al., "An Extensible Architecture for the Integration of Remote and Virtual Laboratories in Public Learning Tools," in IEEE Revista Iberoamericana de Tecnologias del Aprendizaje, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 223-233, Nov. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Zine, Othmane & Errouha, Mustapha & Zamzoum, Othmane & Derouich, Aziz & Talbi, Abdennebi. (2019). SEITI RMLab: A costless and effective remote measurement laboratory in electrical engineering. International Journal of Electrical Engineering Education. 56. 3-23. [CrossRef]

- E. W. de Vries and H. J. Wörtche, "Remote Labs and their Didactics in Engineering Education: A Case Study," 2021 44th International Convention on Information, Communication and Electronic Technology (MIPRO), Opatija, Croatia, 2021, pp. 1598-1600. [CrossRef]

- S. Grassini and L. Lombardo, "Education in I&M: New Insights in Remote Teaching and Learning of Instrumentation and Measurement: The iHomeX Remote Lab Project," in IEEE Instrumentation & Measurement Magazine, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 26-30, February 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. P. Reid and T. D. Drysdale, "Student-Facing Learning Analytics Dashboard for Remote Lab Practical Work," in IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, vol. 17, pp. 1037-1050, 2024. [CrossRef]

- V. Sarac, "Learning Fundamentals of Electrical Engineering by the Aid of Virtual Laboratories," 2024 23rd International Symposium INFOTEH-JAHORINA (INFOTEH), East Sarajevo, Bosnia, and Herzegovina, 2024, pp. 1-5. [CrossRef]

- F. Schauer, M. Krbecek, P. Beno, M. Gerza, L. Palka and P. Spilaková, "REMLABNET II - Open remote laboratory management system for university and secondary schools research based teaching," Proceedings of 2015 12th International Conference on Remote Engineering and Virtual Instrumentation (REV), Bangkok, Thailand, 2015, pp. 109-112. [CrossRef]

- W. Gutierrez Maroquin, M. Fernandez and W. Mantilla Avila, "The Joint Training, a SENA Learning Model for Latin America," in IEEE Latin America Transactions, vol. 14, no. 6, pp. 2997-3002, June 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. AbuShanab, M. Winzker, R. Brück and A. Schwandt, "A study of integrating remote laboratory and on-site laboratory for low-power education," 2018 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain, 2018, pp. 405-414. [CrossRef]

- L. F. Zapata-Rivera and C. Aranzazu-Suescun, "Enhanced Virtual Laboratory Experience for Wireless Networks Planning Learning," in IEEE Revista Iberoamericana de Tecnologias del Aprendizaje, vol. 15, no. 2, pp. 105-112, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Nau and K. Henke, "GOLDi Labs as Fully Integrated Learning Environment," 2024 IEEE World Engineering Education Conference (EDUNINE), Guatemala City, Guatemala, 2024, pp. 1-6. [CrossRef]

- S. Alsaleh, A. Tepljakov, A. Köse, J. Belikov, and E. Petlenkov, "ReImagine Lab: Bridging the Gap Between Hands-On, Virtual, and Remote-Control Engineering Laboratories Using Digital Twins and Extended Reality," em IEEE Access, vol. 10, pp. 89924-89943, 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. d. Silva, J. García-Zubía, U. Hernández-Jayo and J. B. D. M. Alves, "Extended Remote Laboratories: A Systematic Review of the Literature From 2000 to 2022," in IEEE Access, vol. 11, pp. 94780-94804, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Boltsi, K. Kalovrektis, A. Xenakis, P. Chatzimisios e C. Chaikalis, "Ferramentas digitais, tecnologias e metodologias de aprendizagem para estruturas de educação 4.0: uma pesquisa orientada para STEM", em IEEE Access, vol. 12, pp. 12883-12901, 2024. [CrossRef]

- V. Kuvshinnikov, E. Kovshov and V. Korchagin, "Digital Educational Resources in Industrial Radiography," 2024 7th International Conference on Information Technologies in Engineering Education (Inforino), Moscow, Russian Federation, 2024, pp. 1-5. [CrossRef]

- G. Wang, H. Li, S. Ye, H. Zhao, H. Ding and S. Xie, "RFWNet: A Multiscale Remote Sensing Forest Wildfire Detection Network With Digital Twinning, Adaptive Spatial Aggregation, and Dynamic Sparse Features," in IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, vol. 62, pp. 1-23, 2024, Art no. 4708523. [CrossRef]

- S. Prohaska and L. Kennes, "Evaluating the Use of Virtual Twins in a Control Systems Course," 2023 IEEE 2nd German Education Conference (GECon), Berlin, Germany, 2023, pp. 1-6. [CrossRef]

- M. C. Elias-Espinosa and E. Bastida-Escamilla, "Evaluating Digital Twins as Training Centers: A Case Study," 2022 10th International Conference on Information and Education Technology (ICIET), Matsue, Japan, 2022, pp. 1-5. [CrossRef]

- S. Mihai et al., "Digital Twins: A Survey on Enabling Technologies, Challenges, Trends and Future Prospects," in IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, vol. 24, no. 4, pp. 2255-2291, Fourthquarter 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Rayhana, L. Bai, G. Xiao, M. Liao, and Z. Liu, "Digital Twin Models: Functions, Challenges, and Industry Applications," in IEEE Journal of Radio Frequency Identification, vol. 8, pp. 282-321, 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Barbie and W. Hasselbring, "From Digital Twins to Digital Twin Prototypes: Concepts, Formalization, and Applications," in IEEE Access, vol. 12, pp. 75337-75365, 2024. [CrossRef]

- F. Martell-Chavez, J. M. López-Téllez, C. A. Paredes-Orta and R. Espinosa-Luna, "Virtual laboratories for teaching automation, robotics, and optomechatronics," 2023 IEEE World Engineering Education Conference (EDUNINE), Bogota, Colombia, 2023, pp. 1-4. [CrossRef]

- F. Guc, J. Viola and Y. Chen, "Digital Twins Enabled Remote Laboratory Learning Experience for Mechatronics Education," 2021 IEEE 1st International Conference on Digital Twins and Parallel Intelligence (DTPI), Beijing, China, 2021, pp. 242-245. [CrossRef]

- L. Buysse, Q. Van den Broucke, S. Verslype, J. Peuteman, J. Boydens and D. Pissoort, "FPGA-based digital twins of microcontroller peripherals for verification of embedded software in a distance learning environment," 2021 XXX International Scientific Conference Electronics (ET), Sozopol, Bulgaria, 2021, pp. 1-4. [CrossRef]

- M. C. Elias-Espinosa and E. Bastida-Escamilla, "Evaluating Digital Twins as Training Centers: A Case Study," 2022 10th International Conference on Information and Education Technology (ICIET), Matsue, Japan, 2022, pp. 1-5. [CrossRef]

- C. A. Bolu et al., "Appropriate Online Laboratories for Engineering Students in Africa," 2022 IEEE IFEES World Engineering Education Forum - Global Engineering Deans Council (WEEF-GEDC), Cape Town, South Africa, 2022, pp. 1-5. [CrossRef]

- A. Niedźwiecki, S. Jongebloed, Y. Zhan, M. Kümpel, J. Syrbe and M. Beetz, "Cloud-Based Digital Twin for Cognitive Robotics," 2024 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Kos Island, Greece, 2024, pp. 1-5. [CrossRef]

- N. Papulovskaya and I. Izotov, "Internet of Things Online Laboratory: non-Virtual Training," 2024 7th International Conference on Information Technologies in Engineering Education (Inforino), Moscow, Russian Federation, 2024, pp. 1-4. [CrossRef]

- S. I. Ching Wang, E. Zhi Feng Liu, Y. Y. Huang and H. Yu Sang, "When Drone Meets AI Education: Boosting High School Students’ Computational Thinking and AI Literacy," 2024 Pacific Neighborhood Consortium Annual Conference and Joint Meetings (PNC), Seoul, Korea, Republic of, 2024, pp. 45-52. [CrossRef]

- H. Yu and Y. Guo, "Harnessing the Potential of Chat GPT in Education: Unveiling its Value, Navigating Challenges, and Crafting Mitigation Pathways," 2023 5th International Workshop on Artificial Intelligence and Education (WAIE), Tokyo, Japan, 2023, pp. 48-52. [CrossRef]

- Lundström, N. Maleki and F. Ahlgren, "Online Course Improvement Through GPT-4: Monitoring Student Engagement and Dynamic FAQ Generation," 2024 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Kos Island, Greece, 2024, pp. 1-6. [CrossRef]

- S. Pang, D. Kong, D. Liu, R. Pan, H. Wang and X. Wang, "Evaluation of LoRa Network Link Quality in Complex Urban Environments Based on Static and Dynamic Parameters," in IEEE Access, vol. 12, pp. 125369-125383, 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Nur Handayani, Muladi, I. Ari Elbaith Zaeni, W. Cahya Kurniawan and R. Andrie Asmara, "Development of e-Collab Classroom for CNN Practice on Electrical Engineering, Universitas Negeri Malang," 2020 4th International Conference on Vocational Education and Training (ICOVET), Malang, Indonesia, 2020, pp. 47-51. [CrossRef]

- Z. Li, F. Liu, W. Yang, S. Peng and J. Zhou, "A Survey of Convolutional Neural Networks: Analysis, Applications, and Prospects," in IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems, vol. 33, no. 12, pp. 6999-7019, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Saini, S. Dhyani, S. Sharma, M. Awasthi, N. Yamsani and P. Singh, "Machine Learning for Enhanced Student Learning and Engagement in Interactive Classrooms," 2024 2nd International Conference on Advancement in Computation & Computer Technologies (InCACCT), Gharuan, India, 2024, pp. 23-28. [CrossRef]

- A. de la Torre and M. Baldeon-Calisto, "Generative Artificial Intelligence in Latin American Higher Education: A Systematic Literature Review," 2024 12th International Symposium on Digital Forensics and Security (ISDFS), San Antonio, TX, USA, 2024, pp. 1-7. [CrossRef]

- R. Murali, N. Ravi and A. Surendran, "Augmenting Virtual Labs with Artificial Intelligence for Hybrid Learning," 2024 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Kos Island, Greece, 2024, pp. 1-10. [CrossRef]

- M. Mukhammadsidiqov, S. Akmalov and K. Akhmedov, "An Intensive Review and Assessment of Impacts of AI in the Field of Teaching (EdU)," 2024 4th International Conference on Advance Computing and Innovative Technologies in Engineering (ICACITE), Greater Noida, India, 2024, pp. 1013-1017. [CrossRef]

- S. A. Benson, "Embracing Technologies to Facilitate Student Learning and Future Readiness," 2024 International Symposium on Educational Technology (ISET), Macau, Macao, 2024, pp. 344-346. [CrossRef]

- G. Ren, T. Wang and D. Wang, "Construction and Application of Interactive Assessment Environment Based on Document Cloud," 2021 Tenth International Conference of Educational Innovation through Technology (EITT), Chongqing, China, 2021, pp. 234-239. [CrossRef]

- Elmoazen, Ramy & Saqr, Mohammed & Khalil, Mohammad & Wasson, Barbara. (2023). Learning analytics in virtual laboratories: a systematic literature review of empirical research. Smart Learning Environments. 10. 1-20. 10.1186/s40561-023-00244-y.

- A. Fernández, M. A. Eguía and L. E. Echeverría, "Virtual commissioning of a robotic cell: an educational case study," 2019 24th IEEE International Conference on Emerging Technologies and Factory Automation (ETFA), Zaragoza, Spain, 2019, pp. 820-825. [CrossRef]

- M. Jungwirth, P. Hehenberger, S. Merschak, W. -C. Lee and C. -Y. Liao, "Influence of Digitization in Mechatronics Education Programmes: A Case Study between Taiwan and Austria," 2020 21st International Conference on Research and Education in Mechatronics (REM), Cracow, Poland, 2020, pp. 1-7. [CrossRef]

- M. A. G. Martínez, I. Y. Sanchez and F. M. Chávez, "Development of Automated Virtual CNC Router for Application in a Remote Mechatronics Laboratory," 2021 International Conference on Electrical, Computer, Communications and Mechatronics Engineering (ICECCME), Mauritius, Mauritius, 2021, pp. 1-6. [CrossRef]

- L. F. R. Riveros, V. H. B. Tristancho, J. E. S. Sanabria and H. D. V. Amado, "Digital Twins, Didactic Strategy for Teaching Industrial Automation," 2022 Congreso de Tecnología, Aprendizaje y Enseñanza de la Electrónica (XV Technologies Applied to Electronics Teaching Conference), Teruel, Spain, 2022, pp. 1-4. [CrossRef]

- L. Fletcher, J. F. Botero, N. Gaviria, É. F. Aza, and J. Vergara, "RECoNE: A Remote Environment for Computer Networks Education," 2020 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Porto, Portugal, 2020, pp. 787-791, doi 10.1109/EDUCON45650.2020.9125383.

- Y. -a. Bachiri and H. Mouncif, "Applicable strategy to choose and deploy a MOOC platform with multilingual AQG feature," 2020 21st International Arab Conference on Information Technology (ACIT), Giza, Egypt, 2020, pp. 1-6. [CrossRef]

- R. E. Nalawati and A. Dini Yuntari, "Ratcliff/Obershelp Algorithm as An Automatic Assessment on E-Learning," 2021 4th International Conference of Computer and Informatics Engineering (IC2IE), Depok, Indonesia, 2021, pp. 244-248. [CrossRef]

- H. A. Hassan, M. M. Eid, M. M. Elmesalawy and A. M. Abd El-Haleem, "A New Intelligent System for Evaluating and Assisting Students in Laboratory Learning Management System," 2022 14th International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Communication Networks (CICN), Al-Khobar, Saudi Arabia, 2022, pp. 566-571. [CrossRef]

- S. Disa, Purnamawati and A. M. Idkhan, "Web e-Learning: Automated Essay Assessment Based on Natural Language Processing Using Vector Space Model," 2022 4th International Conference on Cybernetics and Intelligent System (ICORIS), Prapat, Indonesia, 2022, pp.1-4. [CrossRef]

- C. N. Tulha, M. A. G. Carvalho, and L. N. de Castro. “LEDA: A Learning Analytics Based Framework to Analyze Remote Labs Interaction.” 2022, In Proceedings of the Ninth ACM Conference on Learning @ Scale (L@S '22). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 379–383. [CrossRef]

- A. Protic, Z. Jin, R. Marian, K. Abd, D. Campbell, and J. Chahl, "Implementation of a Bi-Directional Digital Twin for Industry 4 Labs in Academia: A Solution Based on OPC UA," 2020 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management (IEEM), Singapore, Singapore, 2020, pp. 979-983. [CrossRef]

- Heemels and T. Oomen, "Digital Twins in Mechatronics: From Model-based Control to Predictive Maintenance," 2021 IEEE 1st International Conference on Digital Twins and Parallel Intelligence (DTPI), Beijing, China, 2021, pp. 336 339. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).