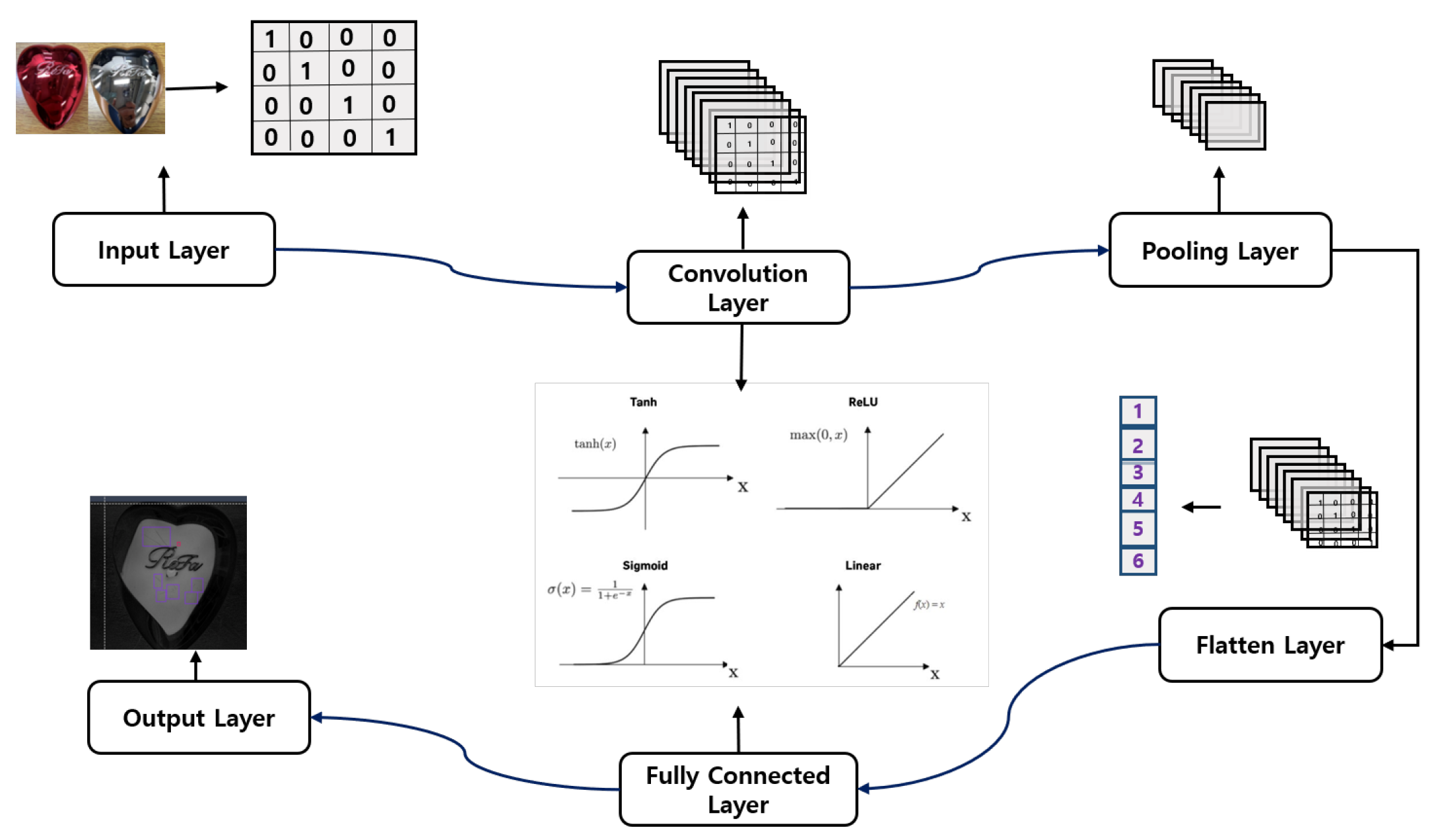

2.1.1. CNN Architectural Overview

A typical CNN architecture is composed primarily of six-layer namely:

Input layer

Convolutional layer

Pooling layer

Flatten layer

Fully connected layer

Output layer

The pictorial illustration of the CNN layers is shown in

Figure 2. A CNN is composed of unique layers, each performing a specific task, which collectively makes it a standout algorithm. Understanding its architecture is paramount to ensuring proper implementation and achieving the desired output. In this overview, our core focus will be on image understanding tasks, which include processing, classification, and fault detection using CNNs (Conv2D).

The first layer of a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) is the input layer, which determines the nature and form of the input based on the task the CNN is configured to perform. In an image input scenario, the building blocks of computer vision are structured in pixels. Pixels represent the numerical equivalents of each color grade, typically ranging from 0 to 255 [

39]. Each color in an image is graded based on this scale, which helps to sequentially organize image inputs into a matrix format. This matrix format transforms the image into a digital layout that the CNN can process. For a comprehensive understanding of the image structure, the brightness, shade, and tint of the image pixels are determined by their pixel value grading [

39,

40].

Input layer: The input layer of the CNN is crucial as it determines and maintains the nature of the input, which directly influences the performance and efficiency of the model. This layer defines the format and structure of the raw data input. To ensure optimal performance of the overall model, factors such as image resolution, data augmentation, normalization, and input channels must be addressed to align with the format of the input layer [

45]. The input layer recognizes three input channel formats: (1) grayscale, (3) RGB (red, green, blue), and (4) alpha channel (RGBA, where A represents transparency). Augmentation helps prepossess the image to enable the CNN model to learn and extract the required features for optimal performance [

46].

To normalize a given image’s pixel values for an input instance, each pixel intensity

, where

x,

y, and

c represent the height, width, and channel of the image pixel, is divided by 255. This process scales the pixel values from the range 0–255 to a normalized range of 0–1. This normalization ensures consistency across the dataset, thereby maintaining stability during the training of the CNN model. Mathematically, image pixel value normalization can be represented as shown in Equ.

1:

Where stands for the normalized image pixel value, I presents the original pixel value.

The output of the input layer, fed to the convolutional layer, is known as a tensor. This tensor is interpreted by the convolutional layer for further processing and feature extraction.

Convolutional layer: The convolutional layer is a unique and pivotal component of the CNN architecture, primarily responsible for feature extraction. It comprises multiple sub-layers that work simultaneously to process the tensor and extract useful features such as edges, textures, and corners. Its working principle involves filters (also known as kernels), which are small matrices of learnable weights [

47]. These filters convolve through the input array, performing a dot product operation with specified strides, ultimately producing a feature map.

At each given position, an element-wise multiplication is performed between the filter values and the corresponding pixels of the input image. The results are then summed up. For a given normalized image pixel fed to a kernel

K, the equation of the convolution operation in the convolutional layer is presented in Equation

2.

Where stands for the output values at positions i and j in the th feature map. U, V, and V represents the filter’s height, width, and input channels receptively, stands for the filter weight at positions u and v for the c-th channel of the k-th filter, and is bias.

The filter size determines the level of details captured in a given image input. Traditionally, filter sizes are often 3×3, 5×5, and 7×7, and the choice is typically based on the user’s preference. Convolutional layers are commonly stacked to ensure detailed feature extraction. Primarily, the first layer extracts low-level features such as edges and corners, while the mid-level layers extract intermediate features such as shapes and patterns. Deeper layers focus on extracting high-level features, which are essential for a comprehensive understanding of distinct and complex patterns. Stacking ensures a progressive increase in the neuron receptive field and allows the network to learn hierarchical representations, which are crucial for complex tasks [

48]. Filters, which are learnable weights that extract features, determine the number of different features learned by the network in a given stacked layer. The network learns the weights of these filters during training, adapting to recognize specific features [

39].

For instance, a layer with 16 filters will generate 16 feature maps, each corresponding to a different learned feature. The size of the kernel determines the level of detail captured; smaller filters capture finer details, while larger filters capture more context but are more computationally expensive. Strides and padding are other important features of the convolutional layer, as they significantly influence the nature of the convolutional layer’s output [

49]. Strides control the step size of the filter during convolution; a stride of 1 ensures that all pixels are processed. However, a stride greater than 1 might not capture all the pixels and will reduce the spatial dimensions of the output.

On the other hand, padding determines the inclusion of input edges in the convolution computation. For instance,

padding adds zeros around the input pixels, resulting in an output with the same spatial dimensions as the input.

padding, on the other hand, does not pad with zeros, resulting in a smaller output due to the reduction caused by the kernel’s dimensions [

45,

49].

Pooling layer: The pooling layer, also called downsampling, helps to refine the extracted features from the convolutional layer by reducing the dimensionality of the feature map. While performing this reduction, it retains the most significant features, thereby enhancing the network’s performance [

39,

45]. This ensures the model maintains its accuracy and computational efficiency. The pooling layer employs three types: max pooling, average pooling, and global pooling. Max pooling selects the strongest feature (maximum value) in a given pooling window. Average pooling, on the other hand, computes the average value in the pooling window. Global pooling operates by applying max or average pooling over the entire feature map, reducing it to a single value per channel [

39,

50].

However, for pooling to be implemented, the pooling window size must be determined, as it defines the dimension of the region over which the pooling operation can be applied to the feature map. This determines the nature of the downsampling in a given pooling layer. Hence, selecting an appropriate window size is paramount in determining the quality and nature of the downsampling performed by the pooling layer. For instance, smaller window sizes, like 2×2, retain finer details of feature maps while downsampling. Larger windows, such as 3×3, offer a more aggressive dimensional reduction, which might lead to the loss of fine details. However, their advantage lies in their ability to capture more contextual features compared to smaller window sizes.

Additionally, while the window size is crucial, the stride is also important as it controls the movement of the pooling window during the pooling operation, similar to its role in the convolutional layer. The stride has a direct impact on the dimensions of the pooling layer’s output. Larger strides result in greater dimensional reduction, whereas smaller strides retain more spatial details in the output feature map. Mathematically, the output of the pooling layer can be represented as follows:

where

represents the output and its dimensions,

represents the input and its dimensions, and

stands for the pooling window and its dimensions.

P and

S represent padding and strides, respectively.

In addition to Equation

3, the equations for max pooling and average pooling are shown below in Equations eqm,eqa, respectively.

Flatten layer: This layer’s functionality is pivotal as it serves as a bridge between the convolutional layer, through the pooling layer, to the fully connected layer. Its core function is to transform the multidimensional feature map input from the pooling layer into a one-dimensional vector, enabling easier feature processing for the fully connected layer without loss of information [

51,

52]. For instance, if the output from the pooling layer is of size 3 × 3 with 64 feature maps, the flattening layer reshapes the output into a one-dimensional vector of size 3 × 3 × 64 = 576. This format is compatible with the fully connected layer, helping the CNN achieve its output by transitioning from multi-dimensional features to a final decision.

Fully connected layers and output layer: The fully connected layer, also known as the dense layer, is a layer in a neural network that functions by connecting every neuron in the given layer to every neuron in the previous layer. This differs from the convolutional layer, where neurons are only connected to a specific region of the input; this concept is referred to as dense connectivity [

39]. The primary function of the fully connected layer is to aggregate and process the extracted features to accomplish tasks such as regression, classification, prediction, fault detection, etc [

39,

45]. Fully connected layers, characterized by their dense connectivity, utilize weights to determine the strength of the connections and biases to shift the weighted sum of the inputs. The combination of the weighted sum and bias is then passed through an activation function to introduce non-linearity, which allows the layer to learn efficiently, even in complex tasks.

Mathematically, the output for a single neuron in a fully connected layer can be expressed as shown in Equation

6 below.

Where F is the output of the neuron, is the activation function, represents the summation of all input, and is the weight of the i-th input. and b represent the input vector and bias, respectively.

The activation function plays a vital role in fully connected layers, just as it does in convolutional layers, where it focuses on processing and retaining spatial features extracted by filters. This ensures that neurons detect complex patterns and hierarchies in the input image. In fully connected layers, activation functions enable the layer to learn and understand the complexity of data by introducing non-linearity to the neural network. Without activation functions, each neuron would only be capable of performing linear tasks, as they would merely compute a linear combination of their inputs [

53,

54].

Some of the commonly used activation functions are mathematically presented in Equation re,softx,sg below.

Where x is the input and e represents Euler’s number.

Each activation function performs a specific task, so it is important to understand its functionality before utilizing it for a given task. For instance, ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit) is best employed in intermediate layers to prevent vanishing gradients and ensure efficient training. It activates a neuron only when the input is positive; a neuron is considered activated if it produces a non-zero output [

53,

54]. Softmax is typically used for multi-class classification tasks, as it converts the outputs of the fully connected layer into probabilities. Sigmoid, unlike Softmax, is used for binary classification tasks, as it maps outputs to the range of 0 and 1. These activation functions define the output layer of the CNN architecture, as the choice of function solely depends on the task to be performed [

39,

55].

Some limitations of the fully connected layer include high computational cost and susceptibility to overfitting. However, these limitations can be controlled or mitigated by properly tuning the parameters of a neural network. This involves selecting optimal parameters, such as the number of layers, filters, padding, strides, and others, to achieve the desired results at an efficient computational cost [

56]. Additionally, techniques such as batch normalization, L1, L2, early stopping, and dropout, generally referred to as regularization techniques, can further help address these challenges.

Regularization refers to techniques and methodologies employed to prevent overfitting by improving a model’s ability to generalize to unseen data [

56]. It achieves this by adding constraints to the model to prevent the model from memorizing the training dataset, thereby ensuring optimal performance. Batch normalization improves the training of neural networks by normalizing the inputs to each layer. When implemented efficiently, it stabilizes the learning process and enables faster convergence.

L1, L2, and Elastic Net are referred to as penalty-based regularization techniques because they introduce penalty terms to the loss function to constrain the model’s parameters. The L1 regularization technique adds a penalty proportional to the absolute values of the weights, encouraging sparsity. This reduces the model’s complexity, making feature selection effective. However, its pitfall is that it might overlook relevant features in some cases. The L2 regularization technique, on the other hand, does not drive weights to zero but instead ensures even weight distribution and prevents overfitting by penalizing the squared values of the weights, reducing their magnitude without pushing them to zero. Elastic Net regularization combines L1 and L2 penalties, striking a balance between sparsity and weight stability[

39,

45,

56].

Early stopping prevents overfitting by monitoring the model’s performance on the validation set during the training phase and halting the process when the performance stops improving. Dropout, on the other hand, reduces overfitting by randomly dropping out (setting to zero) a portion of the neurons during the training phase [

39,

45]. This ensures the model learns redundant and robust features.

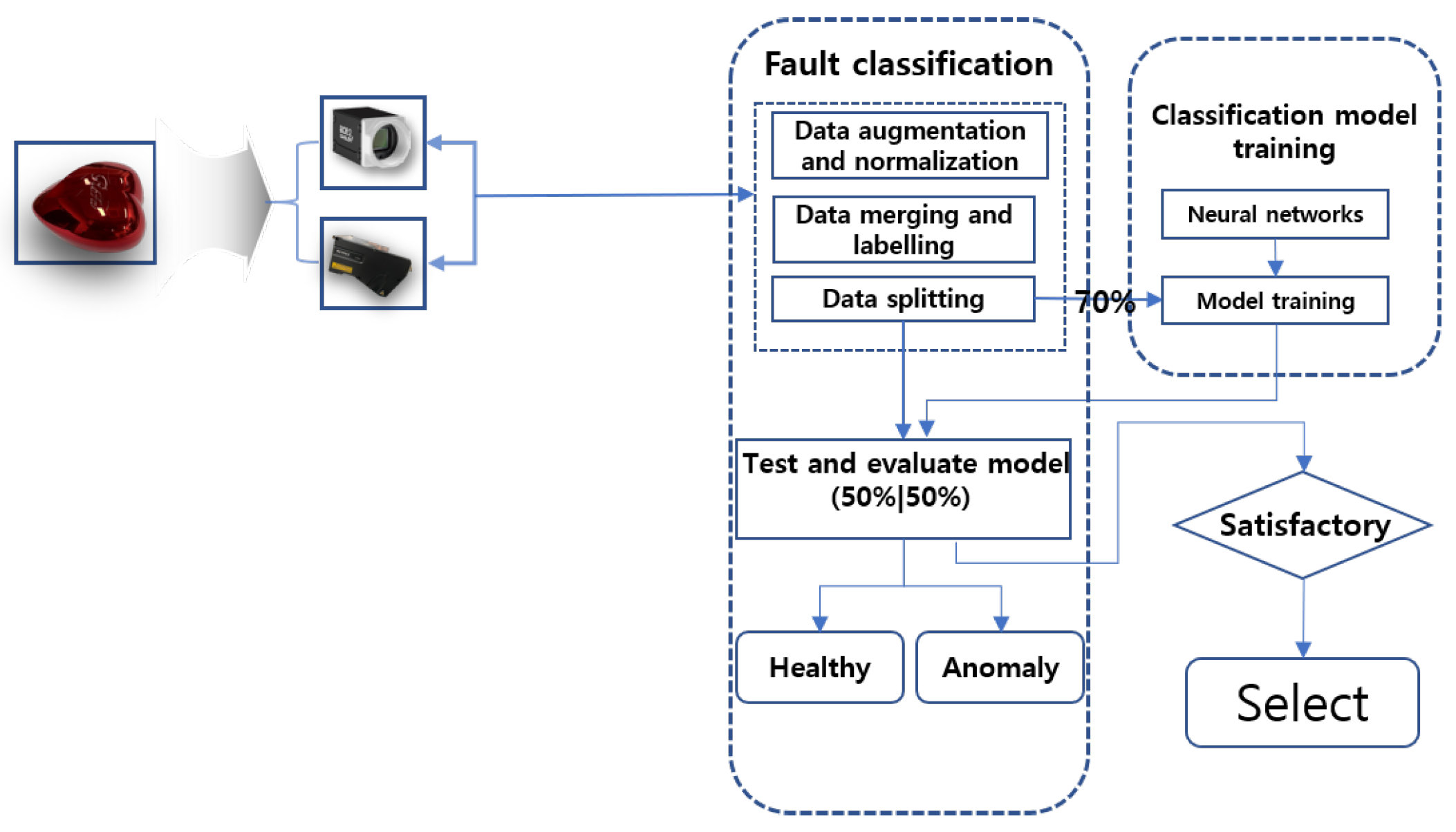

Data augmentation is another key technique used to mitigate overfitting, especially when training a model on limited datasets. It involves generating additional training samples by applying transformations to the existing data [

39]. These transformations can include zooming, adjusting brightness and intensity, and applying horizontal or vertical flips. Data augmentation increases the variability and complexity of the training data, ensuring the model generalizes better and doesn’t overfit to oversimplified datasets. Even for enormous datasets, data augmentation can be employed to add complexity by simulating real-world variations, such as changes in lighting, scaling, or orientation. This ensures the model generalizes better and doesn’t overfit, regardless of the dataset size.