Submitted:

18 March 2025

Posted:

19 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. FCDD (Fully Convolutional Data Description)

2.1. Deep One-Class Classification

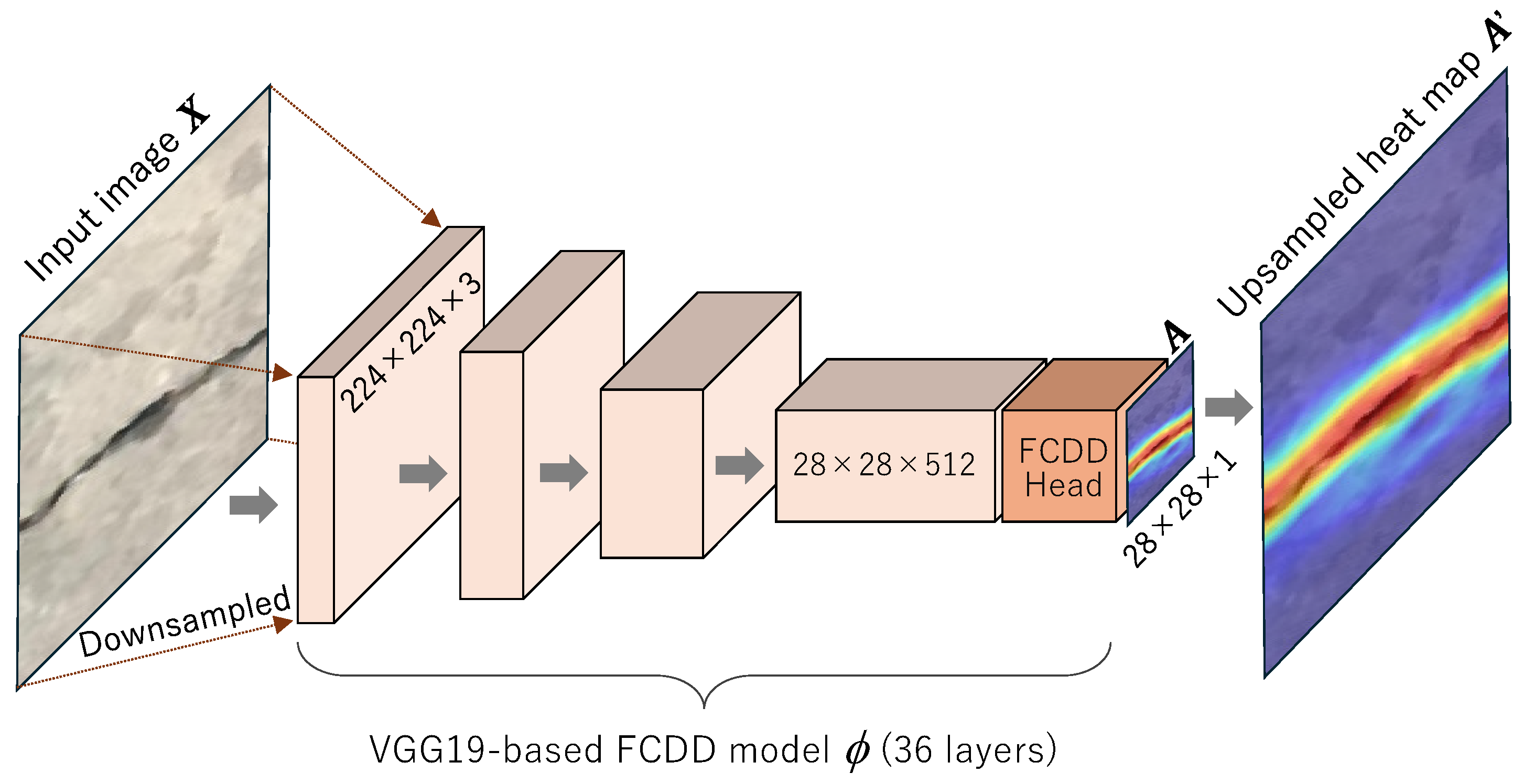

2.2. Fully Convolutional Data Description Model

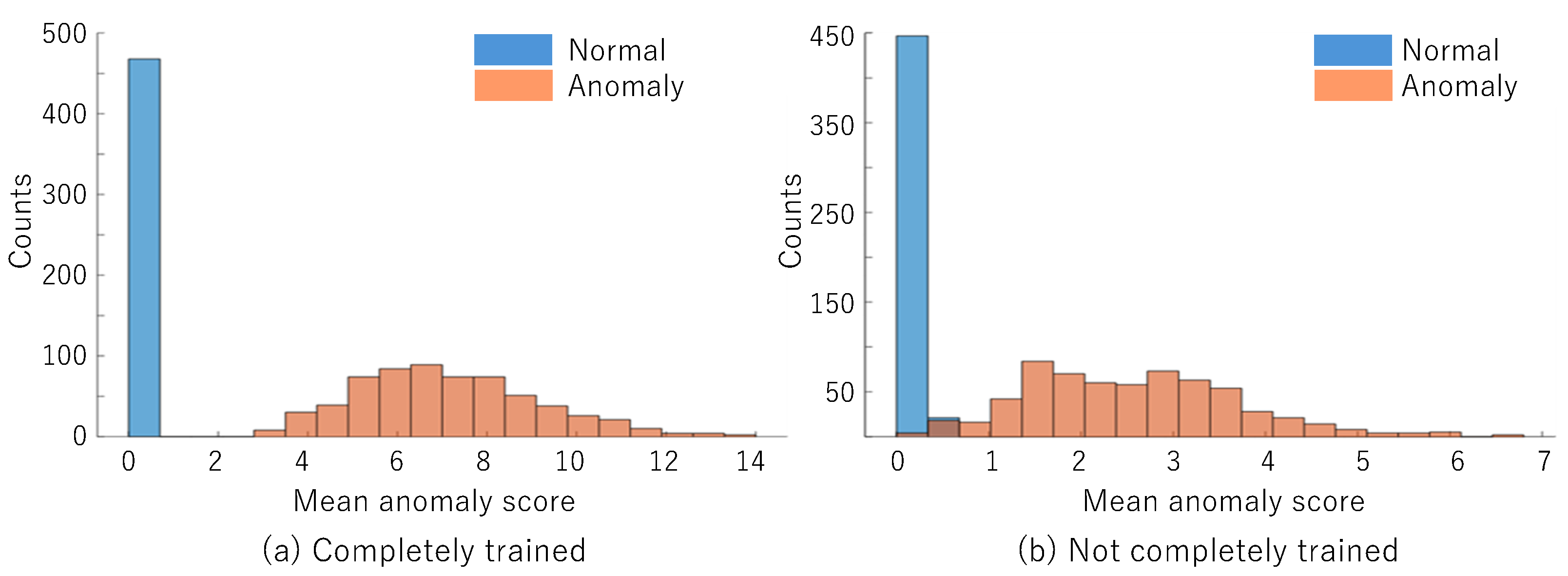

2.3. How to Determine the Threshold Value for Prediction by FCDD

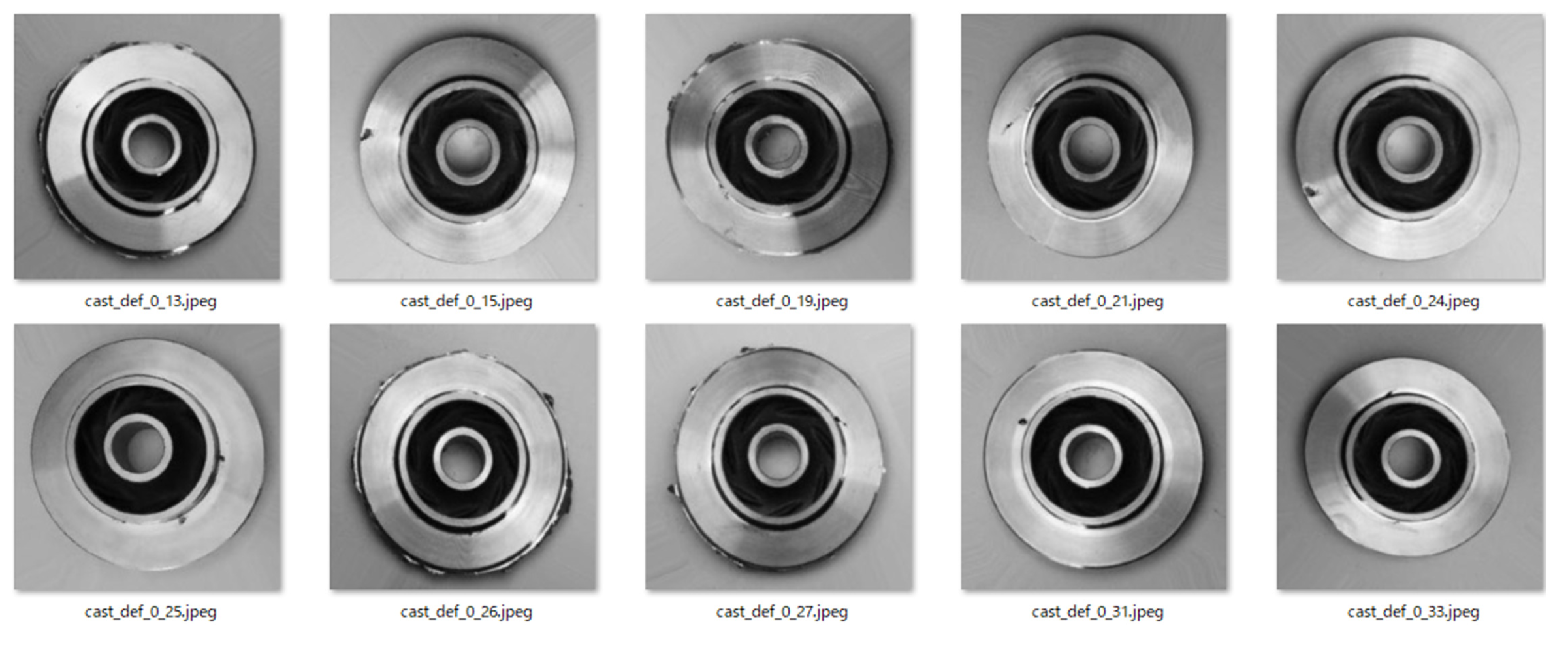

3. Comparison of Transfer Learning-Based CNN and FCDD

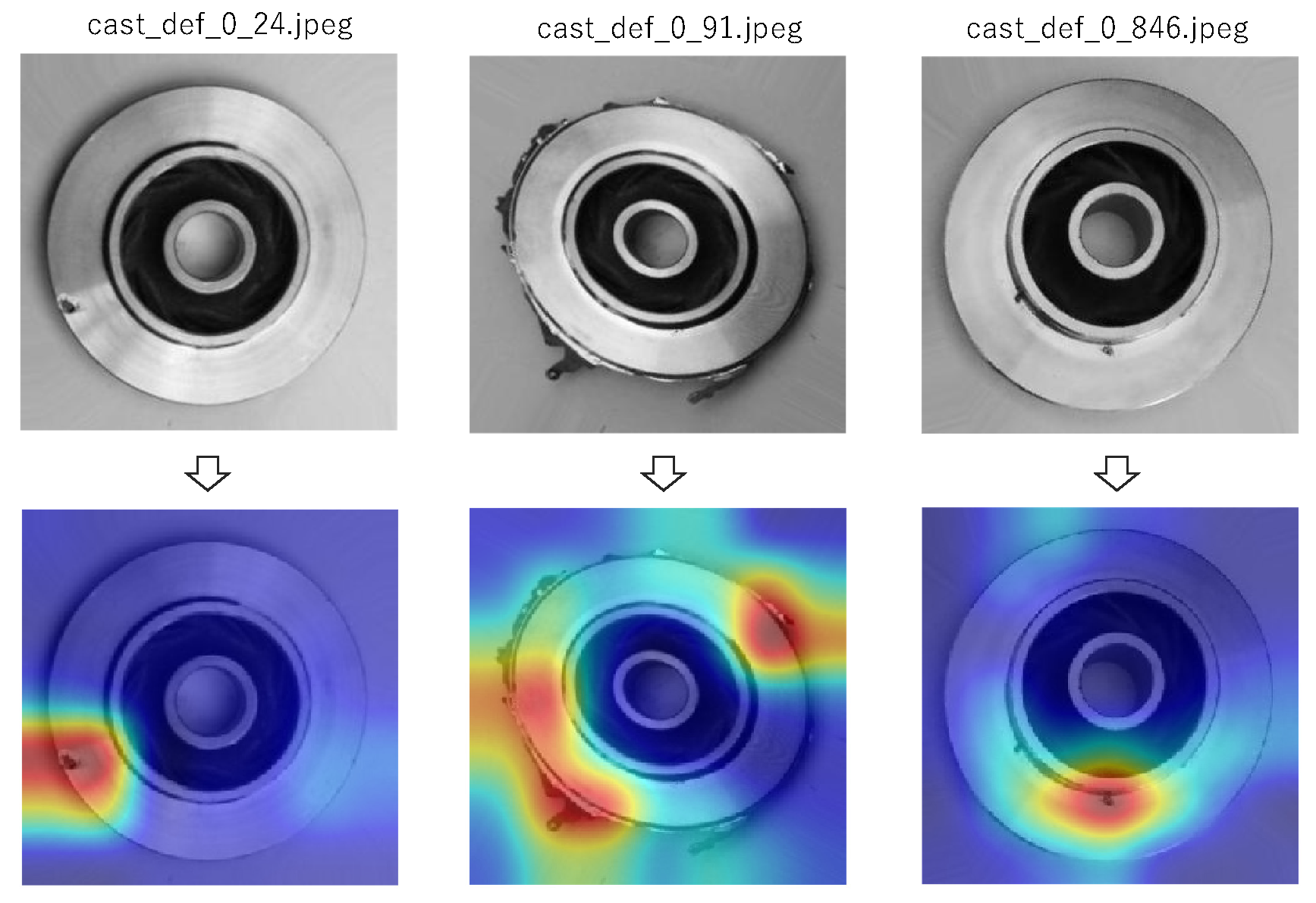

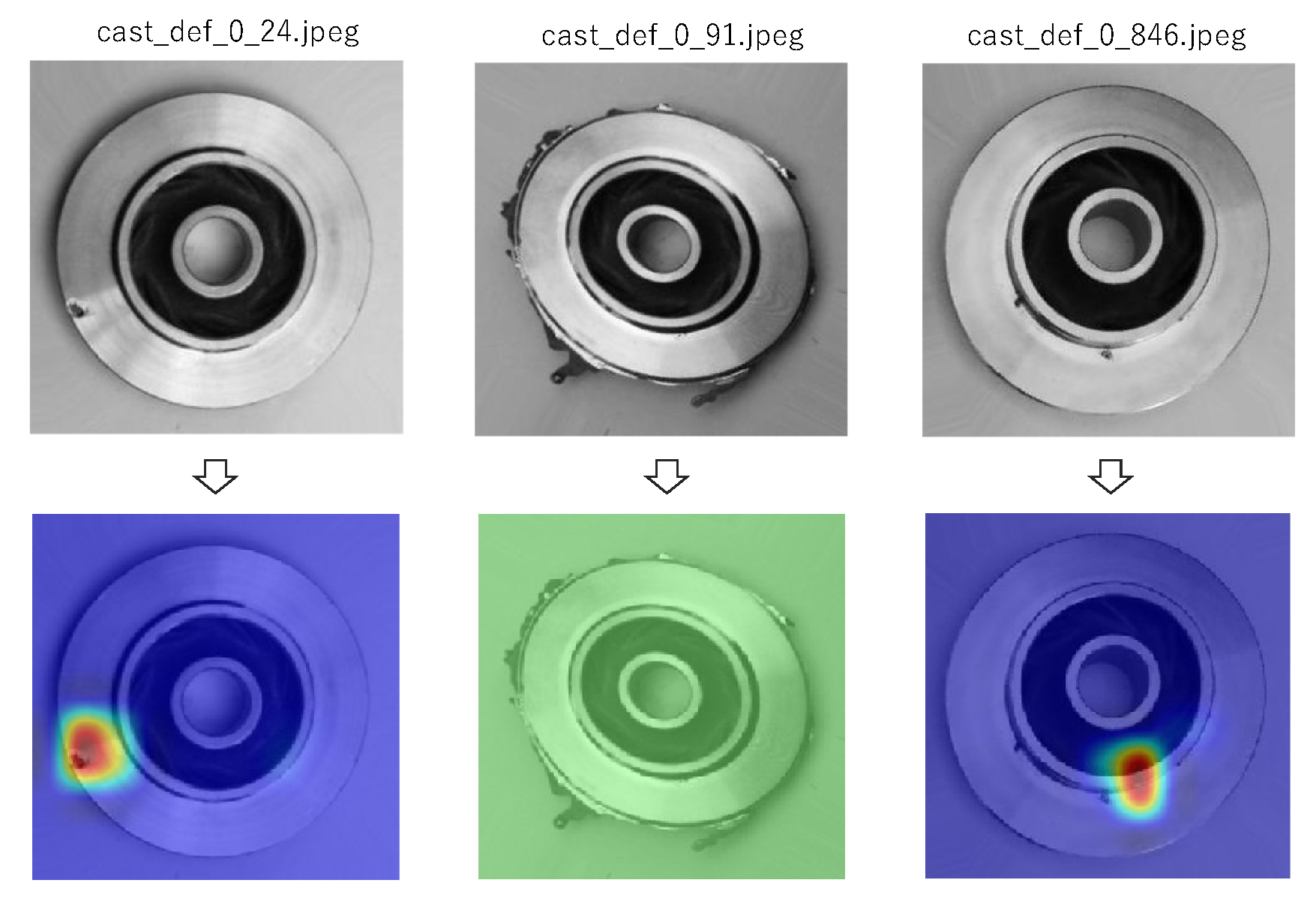

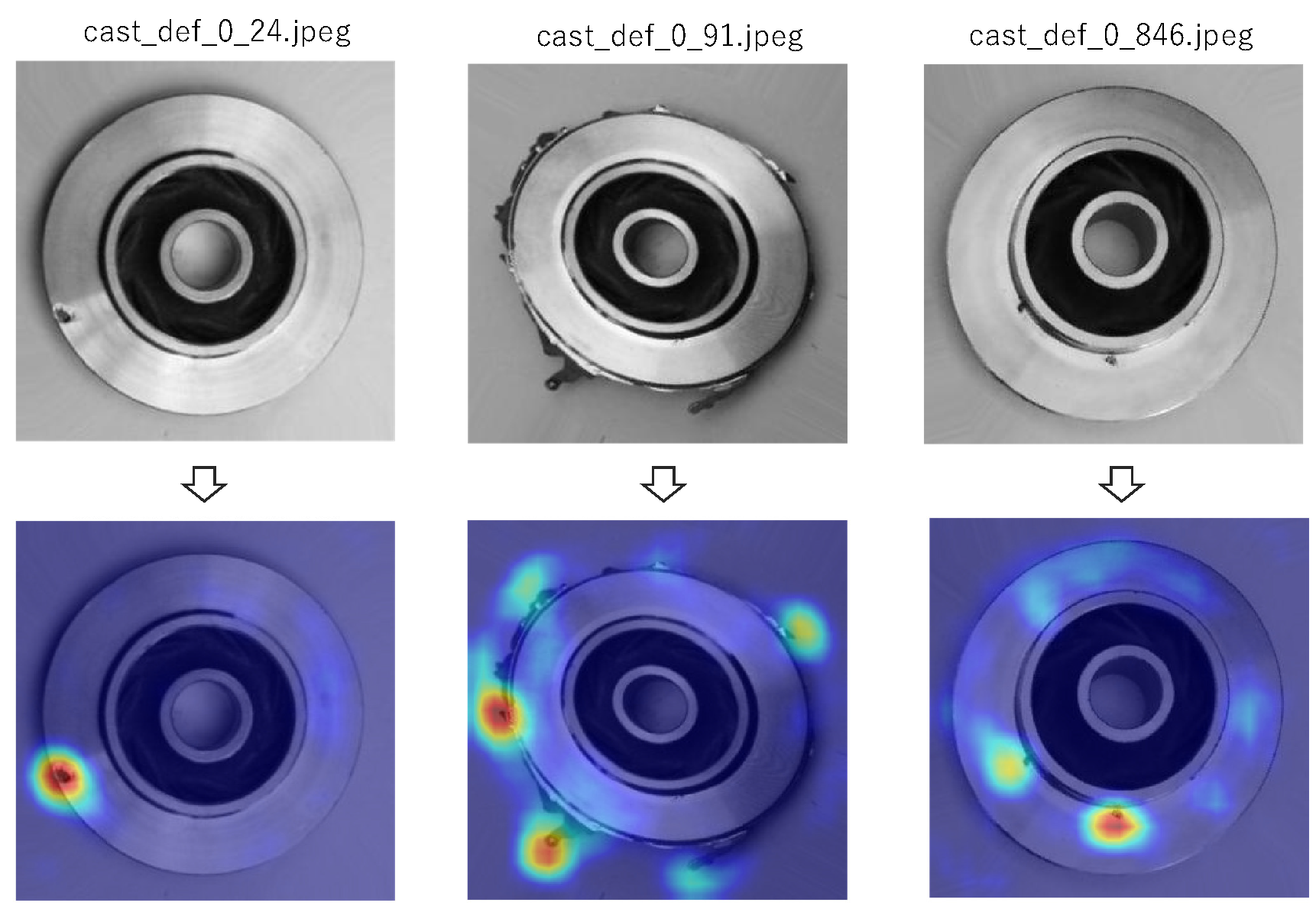

3.1. In case of Transfer Learning-Based CNN Model Based on VGG19

3.2. In case of FCDD

4. Further Comparisons of CNN and FCDD

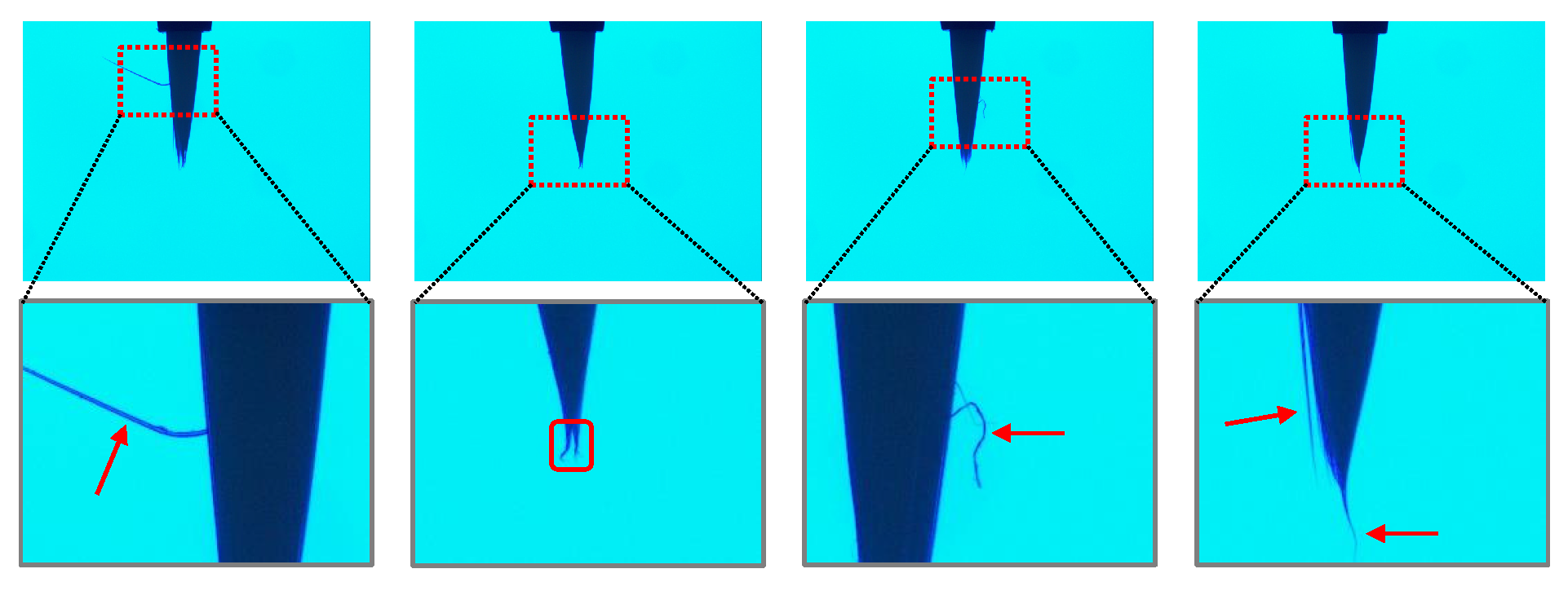

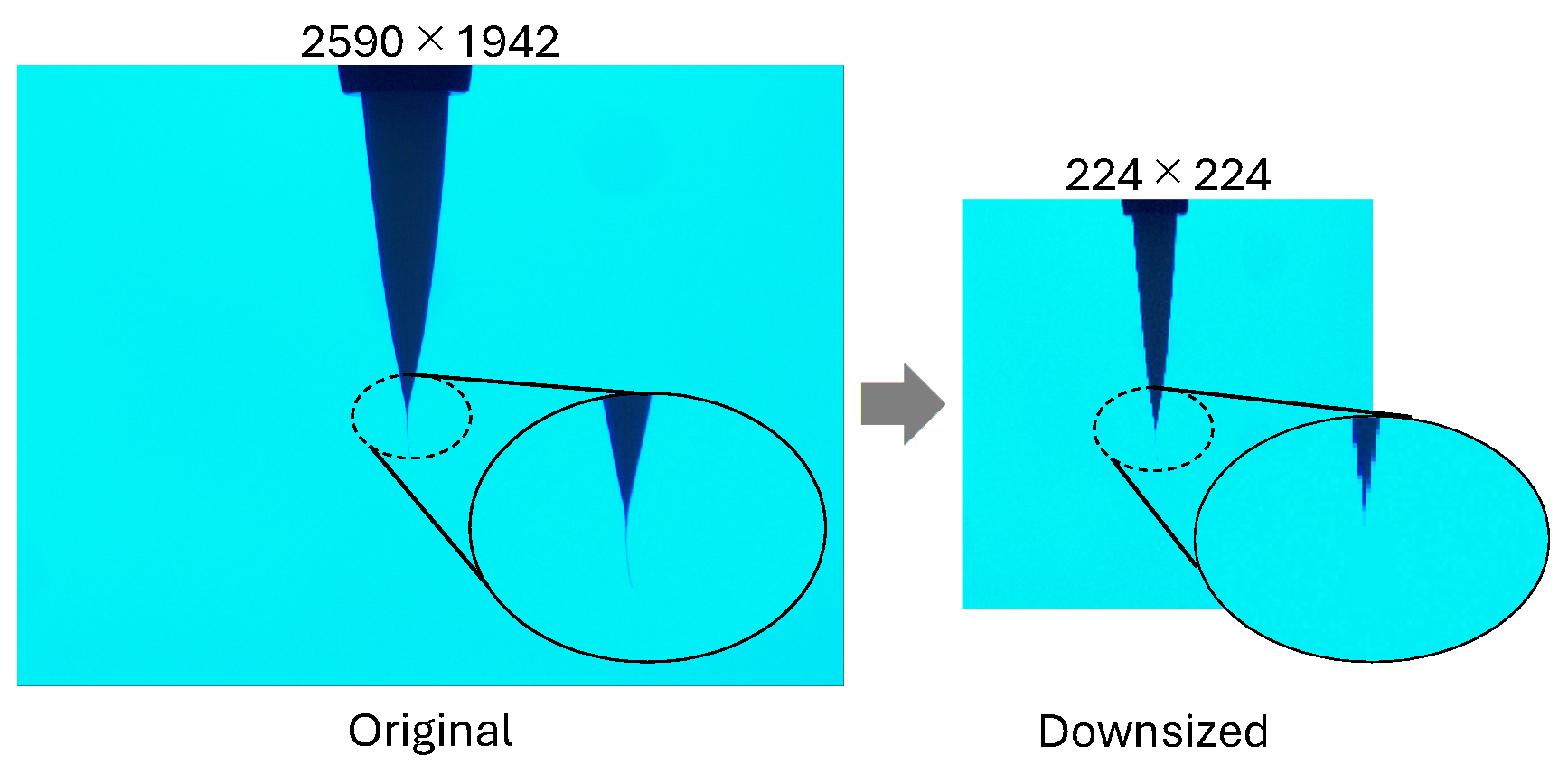

4.1. Defect Detection and Visualization of a Fibrous Industrial Material

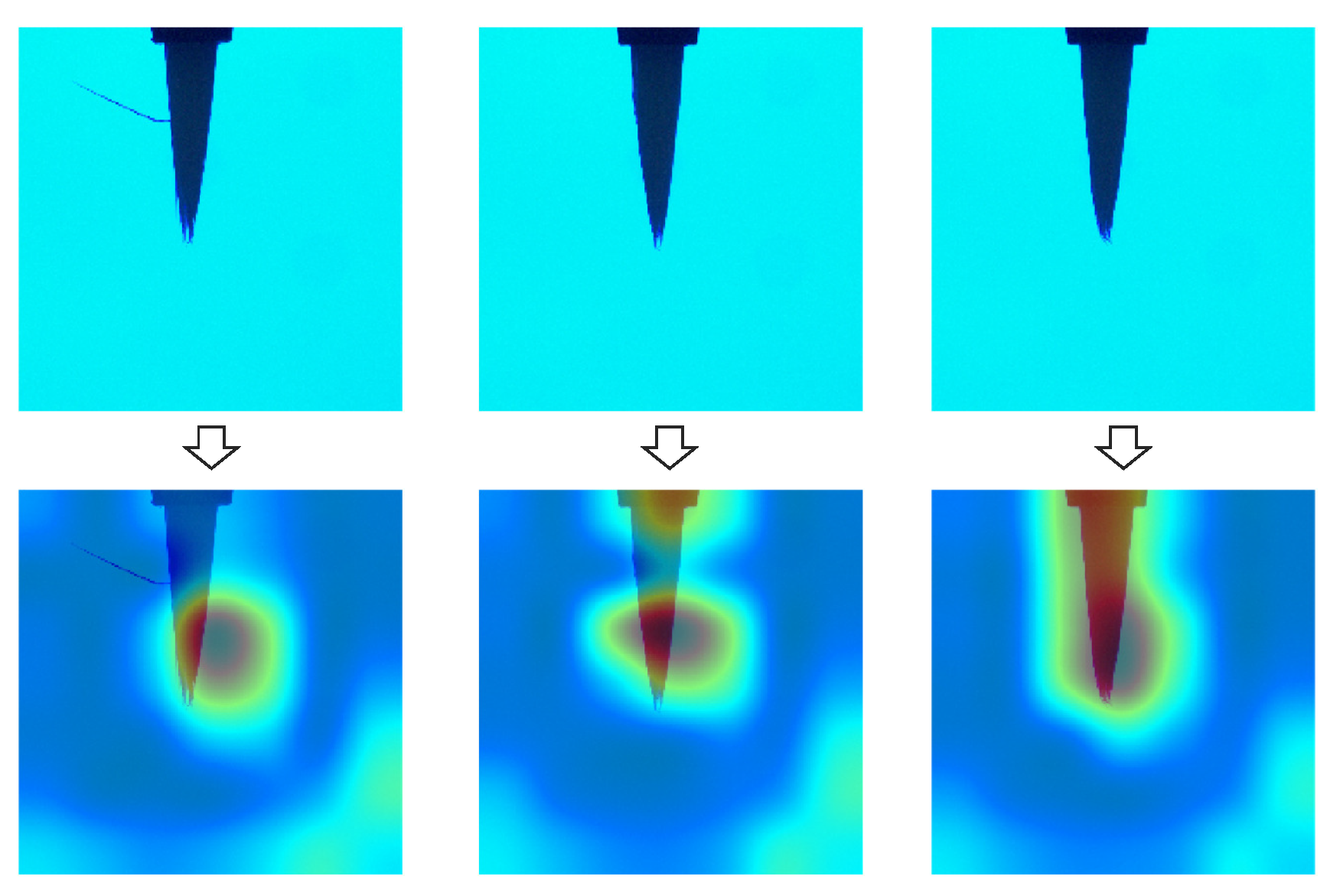

4.1.1. In case of Transfer Learning-Based CNN Model Based on VGG19

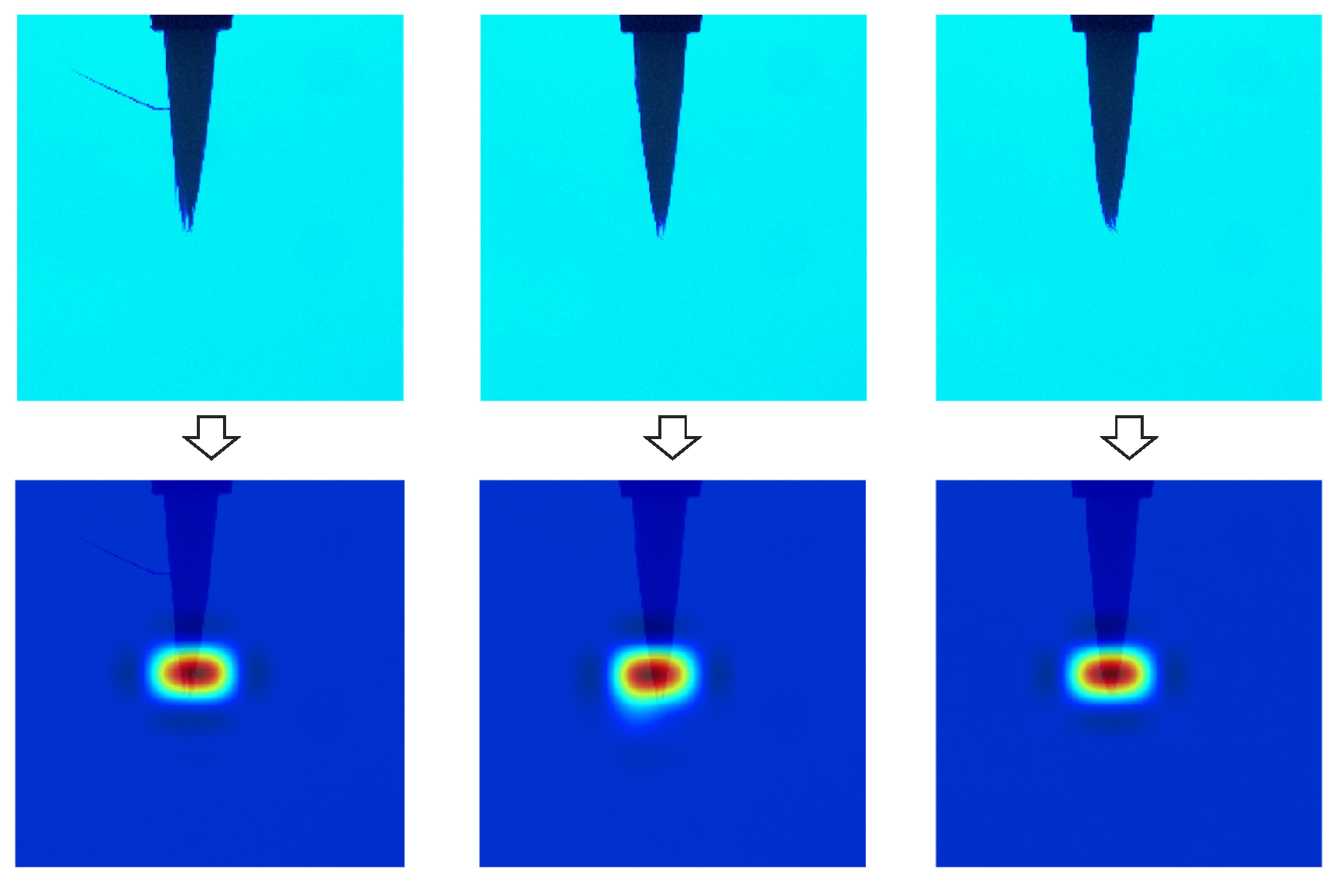

4.1.2. In case of FCDD

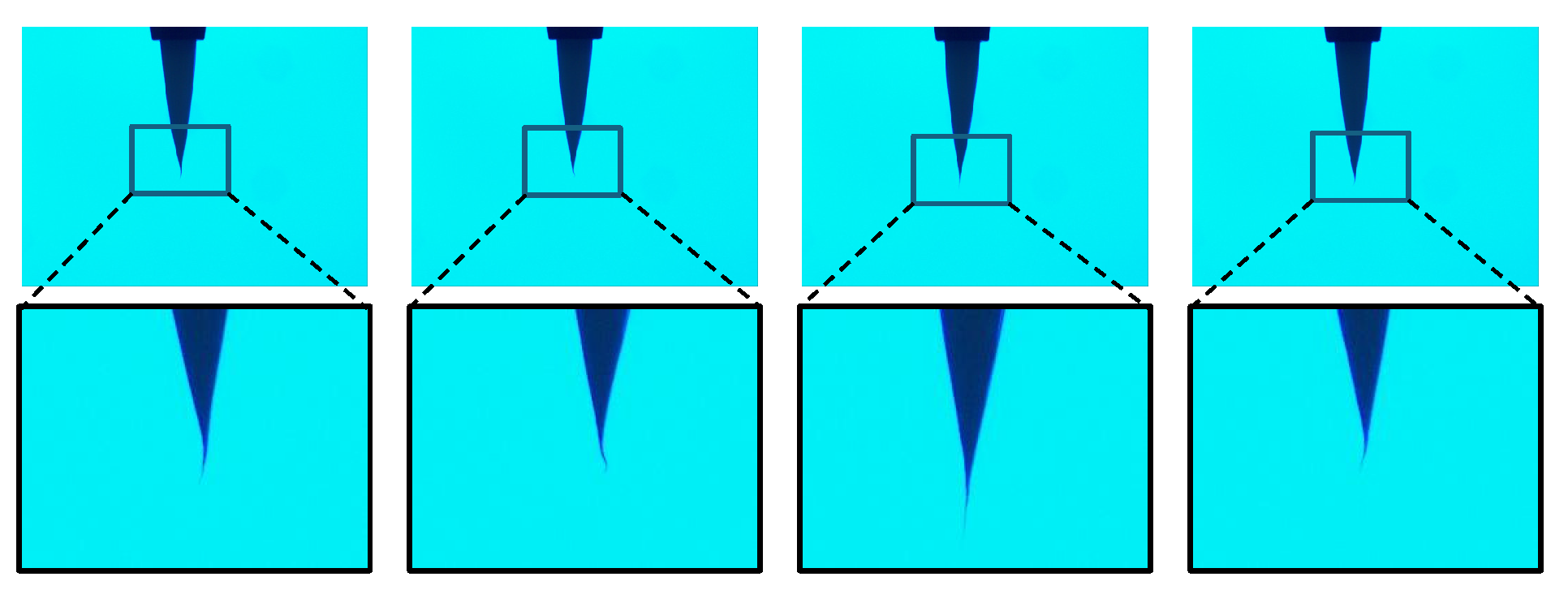

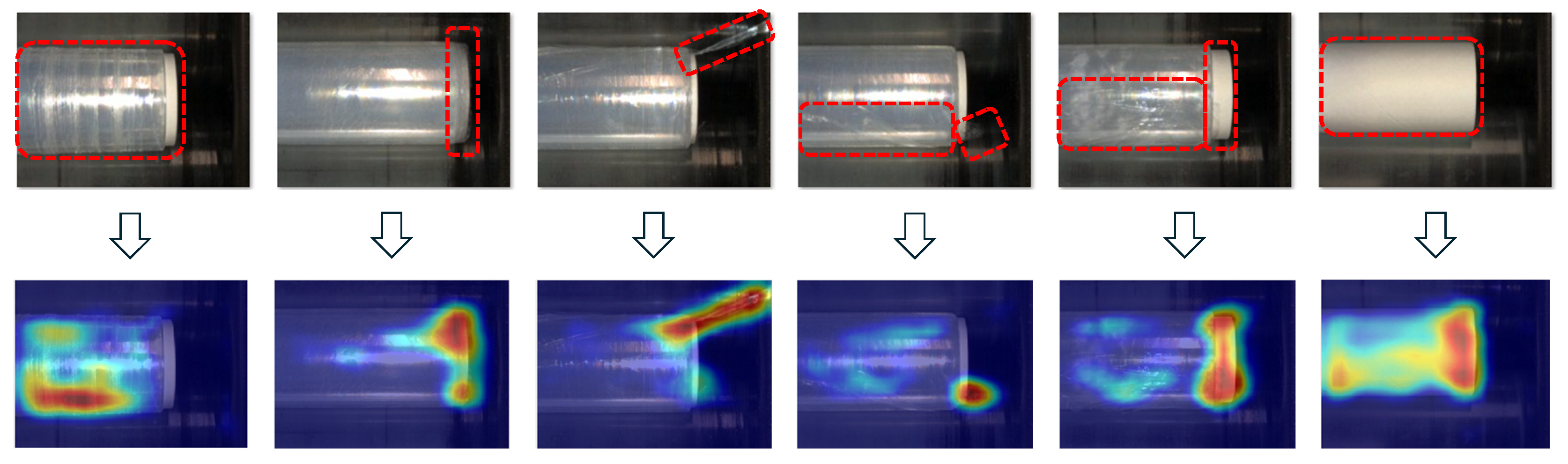

4.2. Defect Detection and Visualization of a Wrap Film Product

4.2.1. In case of Transfer Learning-Based CNN Model Based on VGG19

4.2.2. In case of FCDD

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADAM | Adaptive Moment Estimation Optimizer |

| CAE | Convolutional Auto Encoder |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| FCDD | Fully Convolutional Data Description |

| FCN | Fully Convolution Network |

| Grad-CAM | Gradient-Weighted Class Activation Mapping |

| HSC | Hyper Sphere Classifier |

| SGDM | Stochastic Gradient Decent Momentum Optimizer |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| VAE | Variational Auto Encoder |

References

- P. Liznerski, L. Ruff, R.A. Vandermeulen, B.J. Franks, M. Kloft, K.R. Muller, “Explainable Deep One-Class Classification," Procs. of ICLR2021, pp. 1–25, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S.J. Jang, S.J. Bae, “Detection of Defect Patterns on Wafer Bin Map Using Fully Convolutional Data Description (FCDD),” Journal of Society of Korea Industrial and Systems Engineering, Vol. 46 No. 2, pp.1–12, 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Yasuno, M. Okano, J. Fujii, “One-class Damage Detector Using Deeper Fully Convolutional Data Descriptions for Civil Application,” Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning, Vol. 3, No. 2, pp. 996–1011, 2023. [CrossRef]

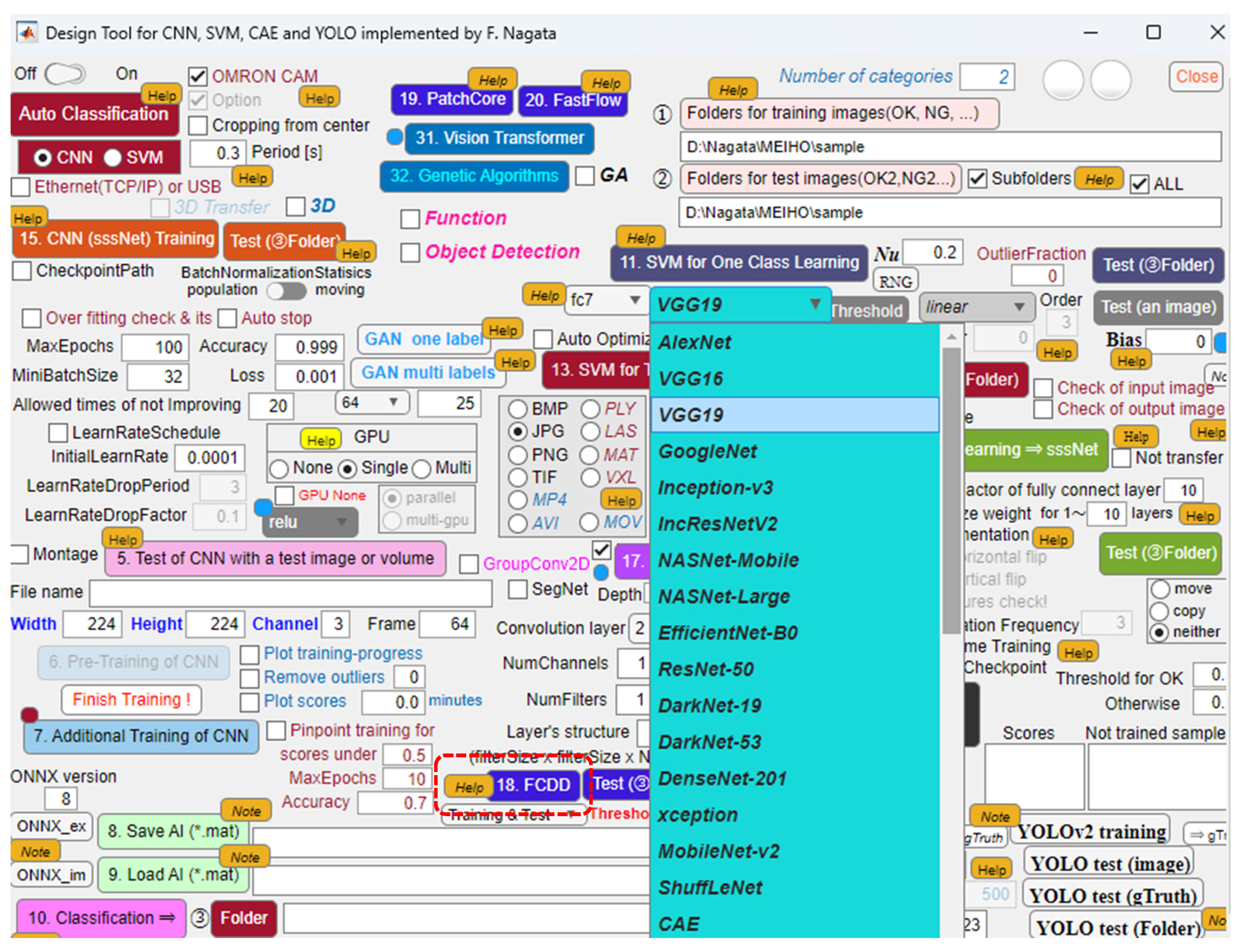

- F. Nagata, K. Nakashima, K. Miki, K. Arima, T. Shimizu, K. Watanabe, M.K. Habib, “Design and Evaluation Support System for Convolutional Neural Network, Support Vector Machine and Convolutional Autoencoder," Measurements and Instrumentation for Machine Vision, pp. 66–82, CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group, July, 2024.

- F. Nagata, S. Sakata, H. Kato, K. Watanabe, M.K. Habib, Defect Detection and Visualization of Understanding Using Fully Convolutional Data Description Models, Procs. of 16th IIAI International Congress on Advanced Applied Informatics, pp. 78–83, 2024.

- L. Ruff, R.A. Vandermeulen, B.J. Franks, K.R. Muller, and M. Kloft, “Rethinking assumptions in deep anomaly detection," arXiv preprint arXiv:2006.00339, 2020.

- P.J. Huber, “Robust Estimation of a Location Parameter," The Annals of Mathematical Statistics, Vol. 35, No. 1, pp. 73–101, 1964.

- Kaggle: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2020. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/ravirajsinh45/real-life-industrial-dataset-of-casting-product?resource=download-directory (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- K. Arima, F. Nagata, T. Shimizu, A. Otuka, H. Kato, K. Watanabe, M.K. Habib, “Improvements of Detection Accuracy and Its Confidence of Defective Areas by YOLOv2 Using a Dataset Augmentation Method," Artificial Life and Robotics, Springer, Vol. 28, No. 3, pp. 625–631, 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Shimizu, F. Nagata, K. Arima, K. Miki, H. Kato, A. Otsuka, K. Watanabe, M.K. Habib, “Enhancing Defective Region Visualization in Industrial Products Using Grad-CAM and Random Masking Data Augmentation," Artificial Life and Robotics, Springer, Vol. 29, No. 1, pp. 62–69, 2023. [CrossRef]

- K.P., Murphy, “Machine Learning: A Probabilistic Perspective," The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2012.

- D. Kingma, J. Ba, “Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization." Procs. of the 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2015), 15 pages, 2015.https://arxiv.org/pdf/1412.6980.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- R.R. Selvaraju, M. Cogswell, A. Das, R. Vedantam, D. Parikh, D. Batra, “Grad-CAM: Visual Explanations from Deep Networks via Gradient-based Localization," Procs. of IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), pp. 618–626, 2017.

- M.D. Zeiler, R. Fergus, Computer Vision – ECCV 2014: 13th European Conference, Proceedings, Part III (Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 8691), pp. 818–833, Springer, 2014.

- T. Shimizu, F. Nagata, M.K. Habib, K. Armina, A. Otsuka, K. Watanabe, Advanced Defect Detection in Wrap Film Products: A Hybrid Approach with Convolutional Neural Networks and One-Class Support Vector Machines with Variational Autoencoder-Derived Covariance Vectors, Machines, Vol. 12, No. 9, pp. 1-20, 2024. [CrossRef]

| Predicted | Anomaly (NG) | Normal (OK) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| True | |||

| Anomaly (NG) | 99 | 1 | |

| Normal (OK) | 0 | 100 | |

| Predicted | Anomaly (NG) | Normal (OK) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| True | |||

| Anomaly (NG) | 99 | 1 | |

| Normal (OK) | 0 | 100 | |

| Predicted | Anomaly (NG) | Normal (OK) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| True | |||

| Anomaly (NG) | 50 | 5 | |

| Normal (OK) | 5 | 41 | |

| Predicted | Anomaly (NG) | Normal (OK) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| True | |||

| Anomaly (NG) | 50 | 5 | |

| Normal (OK) | 6 | 40 | |

| Predicted | Anomaly (NG) | Normal (OK) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| True | |||

| Anomaly (NG) | 618 | 10 | |

| Normal (OK) | 23 | 445 | |

| Predicted | Anomaly (NG) | Normal (OK) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| True | |||

| Anomaly (NG) | 620 | 8 | |

| Normal (OK) | 11 | 457 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).