Introduction

The concept of cognitive reserve has revolutionised our understanding of brain resilience and its capacity to delay the onset of clinical symptoms in neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD). First proposed by Stern (2002), cognitive reserve posits that variability in cognitive processes can explain why some individuals remain clinically asymptomatic despite significant neuropathological burden. This theory contrasts with earlier deterministic models that directly linked neuropathology to clinical outcomes, thus reframing the relationship between brain structure, function, and disease manifestation.

Neurodegenerative diseases are characterised by progressive neuronal loss and synaptic dysfunction, which ultimately compromise the brain’s functional integrity. AD, in particular, is a hallmark example of such diseases, involving amyloid-beta plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, and widespread neuronal death (Hardy & Selkoe, 2002). Yet, the clinical trajectory of AD varies significantly among individuals, with some exhibiting profound pathological changes but little or no cognitive impairment. This variability is increasingly attributed to the concept of cognitive reserve, which acts as a buffer against functional decline.

Section 1.1. Defining Cognitive Reserve: Beyond Brain Volume

Cognitive reserve is not merely an anatomical construct, such as brain volume or cortical thickness; it encompasses the dynamic, adaptive capacity of neural systems to optimise performance under stress or damage. Stern (2009) defines cognitive reserve as the efficiency, capacity, and flexibility of neural networks that enable individuals to cope with neuropathology. This adaptive capability arises from lifelong experiences such as education, occupational complexity, intellectual engagement, and physical activity, which enhance the brain’s functional and structural connectivity (Scarmeas & Stern, 2003).

Recent advances in neuroimaging have further elucidated the neural correlates of cognitive reserve. Studies using functional MRI (fMRI) and diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) have demonstrated that individuals with higher cognitive reserve exhibit greater connectivity in compensatory networks, particularly in the prefrontal cortex and parietal regions, during cognitively demanding tasks (Barulli & Stern, 2013). These findings underscore the significance of network topology and functional redundancy in mitigating the effects of neuronal loss.

Section 1.2. The Role of Network Complexity in Cognitive Reserve

Network neuroscience provides a robust framework for understanding cognitive reserve. The human brain is a complex, small-world network characterised by high clustering and short path lengths, which facilitate efficient communication across regions (Bullmore & Sporns, 2009). The resilience of such networks to damage is determined by their topology, including measures of modularity, connectivity, and robustness to node removal. Highly connected, modular networks are more capable of reorganising and maintaining functionality despite localised damage (Achard et al., 2006).

In the context of neurodegeneration, cognitive reserve can be viewed as an emergent property of network complexity. For instance, Meunier et al. (2009) demonstrated that modular brain networks with rich-club organisation are more resilient to progressive damage. Similarly, van den Heuvel and Sporns (2011) showed that highly central hubs in the brain, such as the posterior cingulate cortex and precuneus, play a pivotal role in maintaining network integrity. These findings suggest that individuals with more complex neural networks are better equipped to compensate for neuronal loss, aligning with the cognitive reserve hypothesis.

Section 1.3. Computational Modelling of Cognitive Reserve

While empirical studies have provided valuable insights into cognitive reserve, computational models offer a complementary approach to exploring its underlying mechanisms. Computational neuroscience enables the simulation of dynamic processes, such as neuronal loss and network reorganisation, under controlled conditions. This approach allows researchers to test specific hypotheses about the relationship between network topology and resilience to damage.

Several models have been developed to simulate the effects of neurodegeneration on brain networks. For example, Honey and Sporns (2008) used a computational framework to examine how progressive node removal impacts functional connectivity in small-world networks. Their findings revealed that network topology significantly influences resilience, with more interconnected networks exhibiting slower functional decline. Extending these principles, our study aims to model the impact of progressive neuronal loss on randomly generated neural networks, simulating the degenerative process in AD.

Section 1.4. Research Objectives and Significance

The primary objective of this study is to investigate the relationship between initial network complexity and resilience to neuronal loss, thereby providing computational evidence for the cognitive reserve hypothesis. Specifically, we aim to address the following questions:

How does network size and complexity influence the rate of functional decline in the face of progressive neuronal loss?

What topological features contribute to network resilience, and how do these features relate to cognitive reserve?

Can computational models inform the development of therapeutic interventions aimed at enhancing cognitive reserve?

By addressing these questions, our study seeks to bridge the gap between theoretical models of cognitive reserve and their empirical validation. The findings have significant implications for understanding the variability in clinical trajectories of AD and other neurodegenerative diseases. Furthermore, the computational approach provides a novel tool for exploring the mechanisms underlying cognitive reserve, offering potential avenues for the development of personalised interventions.

Section 1.6. Empirical Evidence for Cognitive Reserve

Empirical studies have consistently demonstrated the protective effects of cognitive reserve in neurodegenerative diseases. For example, Wilson et al. (2002) found that higher levels of educational attainment were associated with a reduced risk of developing AD, even after controlling for other demographic factors. Similarly, Katzman et al. (1988) reported that individuals with more years of formal education exhibited fewer clinical symptoms of dementia despite significant neuropathological burden. These findings highlight the role of lifelong intellectual engagement in building cognitive reserve.

Neuroimaging studies have further supported these observations. For instance, Arenaza-Urquijo et al. (2013) demonstrated that individuals with higher cognitive reserve show reduced functional connectivity disruptions in the default mode network, a key network implicated in AD. Moreover, studies using task-based fMRI have revealed that higher cognitive reserve is associated with greater recruitment of compensatory networks during memory and executive function tasks (Scarmeas et al., 2004).

Section 1.7. Computational Studies on Network Resilience

Computational approaches have been instrumental in advancing our understanding of cognitive reserve. Network-based models provide a powerful tool for simulating the effects of progressive damage on neural systems, enabling researchers to explore how network topology influences resilience. For example, Kaiser et al. (2007) used a computational model to examine the impact of random and targeted node removal on small-world networks, demonstrating that highly connected networks are more robust to random damage.

Building on these principles, our study adopts a computational approach to investigate the role of network complexity in cognitive reserve. By systematically removing neurons from randomly generated networks, we aim to simulate the progressive neuronal loss observed in AD and assess its impact on network integrity. This approach allows us to quantify the relationship between network size, topology, and resilience, providing new insights into the mechanisms underlying cognitive reserve.

Section 1.8. Implications for Therapeutic Interventions

Understanding the mechanisms of cognitive reserve has important implications for the development of therapeutic interventions. Strategies aimed at enhancing cognitive reserve, such as cognitive training, physical exercise, and lifestyle modifications, have shown promise in mitigating the effects of neurodegeneration (Livingston et al., 2017). Moreover, emerging evidence suggests that interventions targeting network topology, such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and neurofeedback, may further enhance the brain’s resilience to damage.

Our study contributes to this growing body of research by providing a computational framework for exploring the effects of network complexity on resilience. The findings have the potential to inform the design of personalised interventions that optimise cognitive reserve and delay the onset of clinical symptoms in neurodegenerative diseases.

Section 1.9 Summary

The study of cognitive reserve represents a paradigm shift in our understanding of brain resilience and its role in neurodegenerative diseases. By integrating insights from neuroscience, network theory, and computational modelling, we aim to elucidate the mechanisms that enable some individuals to cope with significant neuropathological burden. Our findings are expected to advance the theoretical foundations of cognitive reserve and provide practical implications for the development of therapeutic strategies. This interdisciplinary approach underscores the importance of bridging theoretical and empirical research to address one of the most pressing challenges in neuroscience: understanding and mitigating the impact of neurodegenerative diseases.

Section 2. Methodology

Objective

The primary objective of this study is to investigate the relationship between neural network complexity and its resilience to progressive neuron loss, mimicking neurodegenerative processes such as Alzheimer’s disease. Specifically, the study sought to examine how network size and initial topology impact the maintenance of connectivity as neurons are systematically removed.

Section 2.1. Computational Model

We modeled the neural network as a directed graph , where:

represents the set of nodes (neurons),

represents the set of directed edges (synaptic connections).

The directed graph was constructed using a random graph model, with connections established probabilistically to simulate the stochastic nature of neural connections (Albert & Barabási, 2002). Each node was assigned a random spatial position in a 2D Cartesian plane.

The model simulated progressive neuron loss by iteratively removing nodes and assessing the resultant network connectivity.

Section 2.2. Network Initialisation

For a given network size or :

Nodes were assigned random coordinates in a bounded 2D space , where .

-

Each directed edge

between nodes

and

was probabilistically generated based on a Bernoulli distribution:

The probability was chosen empirically to ensure a sufficiently connected initial network.

The network topology was visualised using a 2D scatter plot, with edges represented as arrows between connected nodes.

Neuron Removal Process

At each iteration :

A node was randomly selected and removed from the graph.

The updated graph was evaluated for:

Section 2.3. Topological Assessment

To quantify the integrity of the network at each step, we used the following metrics:

Section 2.4. Mathematical Equations for Simulations

The out-degree for all remaining nodes was recalculated at each step.

The SCC was identified using a depth-first search algorithm.

- 4.

Simulation Stopping Condition: The process terminated when or when the network contained fewer than 2 nodes.

Scenarios

Two scenarios were simulated:

- 2.

Large Network ( 30 Neurons):

Initial conditions: .

Purpose: To simulate a more complex architecture with potentially higher cognitive reserve.

Section 2.4. Visualisation

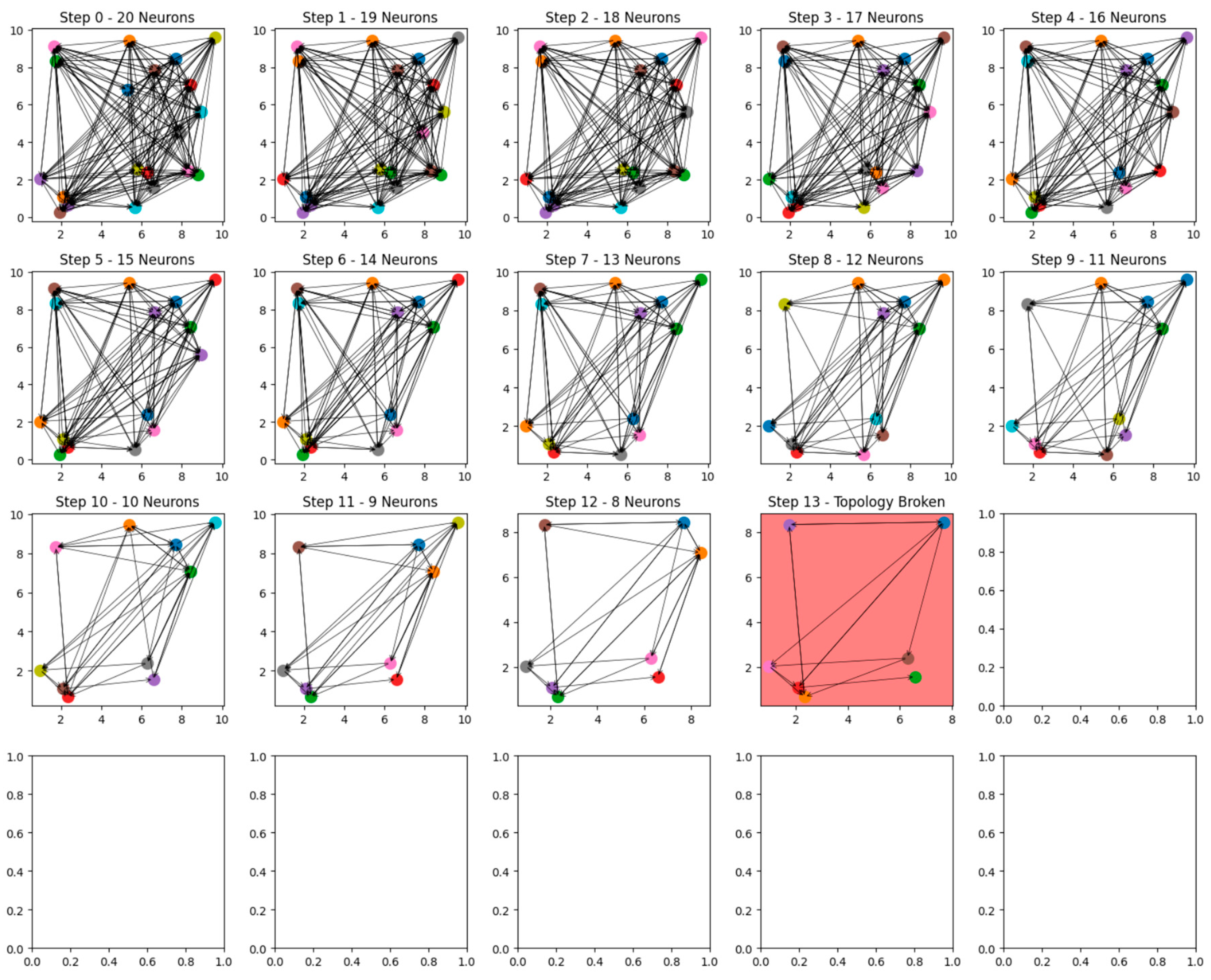

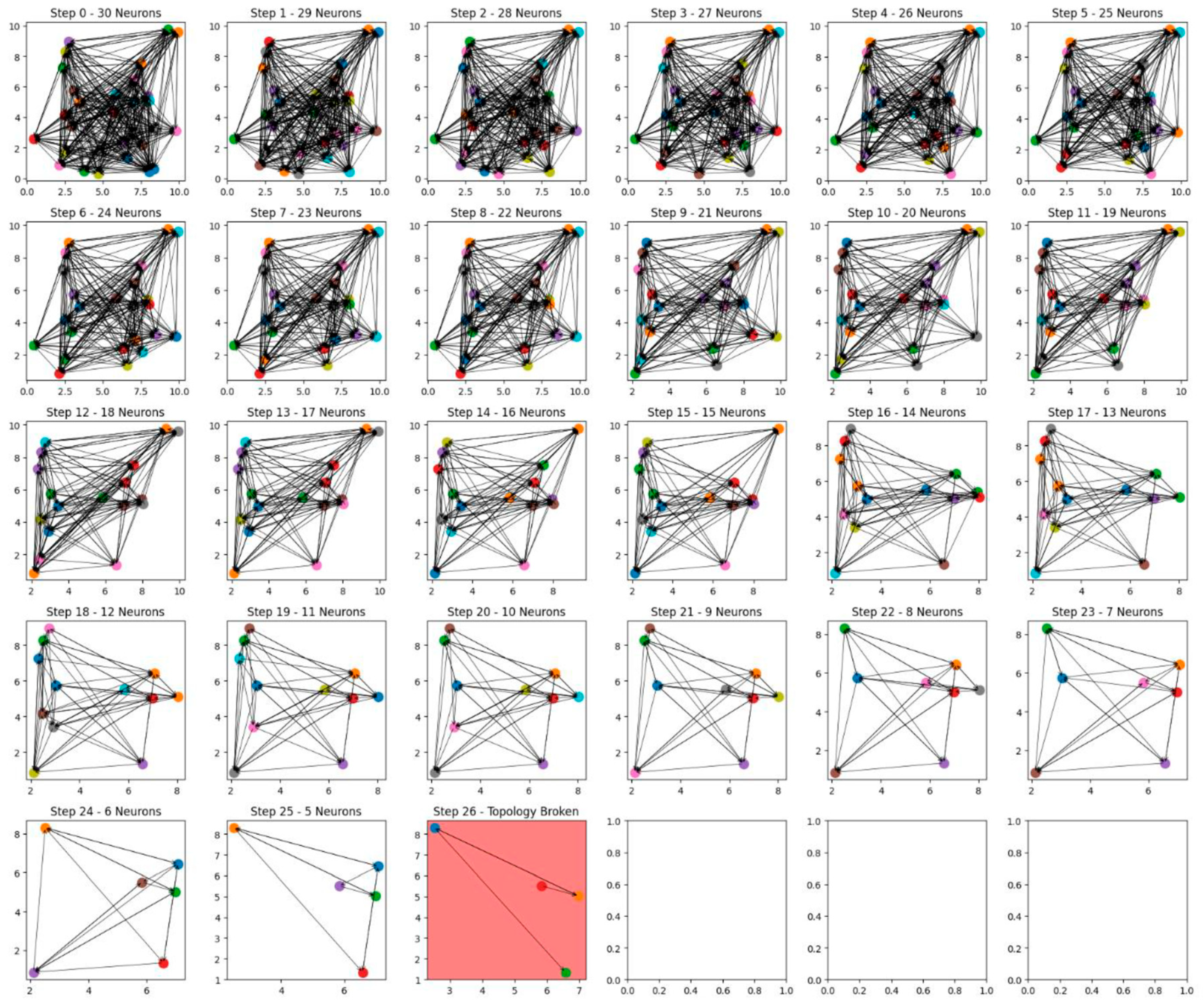

At each iteration k, the network state was visualised using matplotlib. Nodes were colour-coded for clarity, and the iteration at which the topology broke (defined by T_c ) was highlighted with a distinct red background.

Section 3. Results

Section 3.1. Summary of Observations

The results, as visualised in the attached graphs, indicate:

These findings underscore the relationship between network complexity and resilience, providing computational evidence for the cognitive reserve hypothesis.

The results of this study provide a comprehensive visual and quantitative demonstration of how neural network size and complexity influence resilience to progressive neuron loss. Two sets of simulations were conducted: one with a network of 20 neurons and another with 30 neurons. The sequential removal of neurons in each scenario offers insight into the role of initial network topology in delaying structural collapse, shedding light on the underlying principles of cognitive reserve.

The first set of results focuses on the 20-neuron network. Initially, the network exhibits a robust and densely interconnected topology, with all neurons maintaining outgoing connections. The random distribution of neurons and their connections results in a network capable of sustaining its structural integrity through compensatory pathways, even as individual neurons are removed. However, as the simulation progresses, the density of connections diminishes. By the 12th removal step, the network begins to show signs of strain, although the largest strongly connected component (SCC) remains intact. At the 13th step, a critical threshold is reached, and the removal of one more neuron leads to a breakdown in the network’s topology. This event is visually marked by a red background in the graph, signifying the point at which connectivity collapses, leaving the remaining neurons largely isolated and incapable of maintaining functional interactions.

In contrast, the second simulation with a network of 30 neurons demonstrates significantly greater resilience. The initial state of this network features a higher level of connectivity and redundancy, which allows it to redistribute functionality more effectively as neurons are progressively removed. Throughout the first 25 removal steps, the network retains its structural integrity, and the SCC remains robust, reflecting the enhanced compensatory mechanisms afforded by its larger size and more intricate topology. It is not until the 26th step that the network reaches its critical threshold, marked again by a red background, indicating the collapse of its functional connectivity. The delayed breakdown of the larger network underscores the protective effect of increased network complexity, as its richer interconnectivity enables it to withstand a higher degree of progressive damage.

A comparative analysis of the two networks reveals the profound impact of initial size and connectivity on resilience. The smaller, 20-neuron network collapses after 13 removal steps, while the larger, 30-neuron network remains functional until 26 neurons are removed. This nearly twofold increase in resilience demonstrates the significant role that greater network size and complexity play in delaying the breakdown of functional topology. The larger network’s ability to sustain connectivity for a longer duration highlights the importance of compensatory pathways and redundancy in mitigating the effects of neuron loss.

These findings align closely with the cognitive reserve hypothesis, which posits that individuals with more complex neural networks can better withstand neuropathological damage. The results of this study suggest that the protective effect of cognitive reserve is rooted in the initial size and complexity of the network. Larger and more interconnected networks exhibit an enhanced capacity for maintaining functionality under stress, reflecting the theoretical principles of network neuroscience. The resilience observed in the larger network mirrors the empirical findings in studies of human brain networks, where individuals with greater cognitive reserve show delayed onset of clinical symptoms in neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s.

The visual progression in the graphs reinforces these conclusions, illustrating the gradual erosion of network integrity with each step of neuron removal. The red backgrounds in the final stages serve as clear indicators of the critical points at which the networks fail, providing a striking contrast between the resilience of the 20-neuron and 30-neuron networks. The larger network’s ability to delay breakdown underscores its capacity to redistribute connectivity and maintain functionality, even as the number of remaining neurons dwindles.

In summary, the results provide compelling evidence for the relationship between network complexity and resilience, offering computational support for the cognitive reserve hypothesis. The larger, more interconnected network demonstrates a clear advantage in delaying the breakdown of functional topology, highlighting the protective effects of increased initial size and connectivity. These findings not only enhance our understanding of cognitive reserve but also provide a valuable framework for exploring interventions aimed at bolstering brain resilience in the context of neurodegenerative diseases.

Section 4. Discussion

The resilience of neural networks to progressive damage has long been a topic of significant interest in neuroscience, particularly in the context of neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Cognitive reserve (CR) provides a compelling framework to explain individual differences in clinical outcomes despite similar levels of neuropathology (Stern, 2002). By computationally modelling neural networks and simulating progressive neuron loss, this study sheds light on the mechanisms underlying CR and its implications for understanding and potentially mitigating neurodegeneration.

Section 4.1. Relationship Between Network Complexity and Resilience

Our findings support the hypothesis that larger and more complex neural networks are more resilient to neuronal loss. The critical threshold for topology breakdown (TcT,_cTc) was significantly higher in the larger network (30 neurons) compared to the smaller network (20 neurons). This aligns with the theoretical principles of network neuroscience, which posit that more interconnected and modular networks can better redistribute functionality and maintain structural integrity in the face of damage (Bullmore & Sporns, 2009).

One of the key determinants of network resilience is its connectivity profile, including factors such as degree distribution and clustering coefficient. Networks with a scale-free topology, where a small number of highly connected hubs dominate the connectivity, are particularly robust to random node removal (Barabási, 2009). While our model used a random graph framework, the larger network’s greater connectivity and redundancy likely conferred advantages in maintaining its structural integrity. These results echo empirical findings from human brain networks, where individuals with higher CR show greater functional connectivity in key regions such as the prefrontal cortex and parietal lobe (Scarmeas & Stern, 2003).

Section 4.2. Implications for Cognitive Reserve

The concept of CR has far-reaching implications for understanding the variability in neurodegenerative disease progression. By demonstrating that larger and more interconnected networks are more resilient, our study provides computational evidence for the CR hypothesis, which posits that enriched neural networks delay the onset of clinical symptoms despite underlying pathology (Stern, 2009). This has significant implications for both theoretical and clinical neuroscience.

From a theoretical perspective, CR can be viewed as an emergent property of network complexity. The ability of neural networks to reorganise and compensate for damage is not determined solely by their size but also by their topological features, such as modularity and the presence of rich-club hubs (van den Heuvel & Sporns, 2011). These hubs act as integrative nodes that facilitate global communication, ensuring the continuity of information flow even when peripheral nodes are damaged. The computational model used in this study reinforces the importance of such features by illustrating how networks with higher initial complexity exhibit delayed topology breakdown.

Clinically, CR provides a valuable framework for developing personalised interventions aimed at enhancing brain resilience. Lifestyle factors such as education, intellectual engagement, and physical activity have been shown to increase CR by promoting synaptogenesis and neuroplasticity (Valenzuela & Sachdev, 2006). Understanding the mechanisms by which these factors influence network topology could inform the design of targeted therapies to strengthen CR and slow disease progression.

Section 4.3. Limitations of the Model and Future Directions

While the computational model used in this study provides valuable insights, it also has limitations that warrant discussion. First, the model employs a random graph framework, which, while useful for simulating general network properties, may not fully capture the specific topological characteristics of real neural networks. Human brain networks exhibit small-world properties, characterised by high clustering and short path lengths, which optimise both local and global communication (Achard et al., 2006). Incorporating small-world topology into future models could enhance their biological realism and provide more nuanced insights into the mechanisms of CR.

Second, the model does not account for neuroplasticity, the brain’s ability to reorganise itself by forming new connections in response to damage. In real neural systems, the loss of a neuron often triggers compensatory mechanisms that redistribute functionality across the network (Gomez-Ramirez & Costa, 2017). Including dynamic rewiring algorithms in future simulations could provide a more accurate representation of how neural networks adapt to progressive damage.

Third, the model focuses exclusively on structural connectivity, neglecting functional aspects such as oscillatory synchronisation and dynamic coupling. Functional connectivity plays a crucial role in cognitive processes and is often disrupted in neurodegenerative diseases (Babiloni et al., 2016). Integrating functional connectivity into the model could offer a more comprehensive understanding of how CR operates at both structural and functional levels.

Finally, the study examines only two network sizes (20 and 30 neurons), which, while sufficient to demonstrate the general relationship between network complexity and resilience, may not fully capture the scale and variability of real brain networks. Future studies should explore a broader range of network sizes and densities to generalise the findings and investigate potential non-linear relationships.

Section 4.4. Theoretical Contributions to Network Neuroscience

This study contributes to the growing body of literature on network neuroscience by highlighting the importance of topological features in determining network resilience. The findings align with previous work showing that modularity, rich-club organisation, and global efficiency are key predictors of network robustness (Rubinov & Sporns, 2010). By demonstrating these principles in the context of progressive neuronal loss, the study provides a computational framework for understanding how network topology influences the brain’s capacity to resist and adapt to damage.

The results also have implications for the study of brain ageing and neurodegeneration. Ageing is associated with a decline in network efficiency and a shift from small-world to more random-like topology (Achard & Bullmore, 2007). Understanding how these changes impact network resilience could provide valuable insights into the ageing brain’s susceptibility to neurodegenerative diseases and the role of CR in mitigating these effects.

Section 4.5. Practical Implications for Neurodegenerative Disease Research

The computational approach used in this study offers a novel tool for exploring the mechanisms underlying neurodegenerative diseases. By simulating the progressive loss of neurons, the model provides a controlled environment for testing hypotheses about the relationship between network topology and resilience. This has practical implications for developing diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

For example, graph-theoretical measures of brain connectivity, such as clustering coefficient and path length, have been proposed as biomarkers for early detection of neurodegenerative diseases (Pievani et al., 2011). The model could be used to simulate how these measures change in response to different patterns of neuronal loss, providing insights into their diagnostic utility. Additionally, the model could inform the design of network-based interventions, such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) or cognitive training, aimed at enhancing CR by strengthening specific topological features.

Section 4.6. Broader Implications for Cognitive Neuroscience

Beyond its applications to neurodegenerative diseases, the findings have broader implications for understanding the principles of cognitive organisation and resilience. The relationship between network complexity and resilience may extend to other domains, such as learning and memory, which depend on the brain’s ability to dynamically reorganise its connections in response to new information (Bassett et al., 2011). Investigating how these principles operate in healthy brain networks could provide insights into the general mechanisms of cognitive function and dysfunction.

Moreover, the study highlights the value of computational models as a complement to empirical research. While experimental studies provide direct evidence of neural processes, computational models allow for the systematic manipulation of variables and the testing of theoretical hypotheses. The integration of these approaches is essential for advancing our understanding of complex systems like the brain.

Section 4.7. Ethical and Societal Considerations

The findings also raise important ethical and societal considerations. As our understanding of CR improves, there is a growing potential for interventions aimed at enhancing brain resilience. While these interventions hold great promise, they also raise ethical questions about access and equity. For example, lifestyle factors that promote CR, such as education and intellectual engagement, are often shaped by socioeconomic status (Valenzuela & Sachdev, 2006). Ensuring that interventions are accessible to all individuals, regardless of socioeconomic background, is essential for addressing health disparities in neurodegenerative diseases.

Additionally, the use of computational models in neuroscience raises questions about the balance between simplification and biological realism. While models are valuable tools for hypothesis testing, they inevitably involve assumptions and approximations that may limit their applicability to real-world systems. Ensuring transparency and critical evaluation of model assumptions is essential for their responsible use in research and clinical applications.

Section 4.8. Future Prospects

Looking ahead, the integration of computational and experimental approaches offers exciting prospects for advancing our understanding of CR and neurodegeneration. Advances in neuroimaging and network analysis are enabling increasingly detailed characterisations of brain connectivity, providing empirical data to validate and refine computational models (Sporns, 2011). Additionally, emerging techniques such as optogenetics and connectomics are opening new avenues for studying the dynamic processes that underpin CR at the cellular and network levels.

One promising direction for future research is the development of personalised models of brain resilience. By incorporating individual variability in factors such as network topology, genetic predisposition, and lifestyle, these models could provide tailored predictions of disease progression and inform personalised intervention strategies. Such approaches would represent a significant step toward the goal of precision medicine in neurodegenerative diseases.

Section 5. Conclusions

This study provides a computational framework to explore the cognitive reserve hypothesis by simulating progressive neuron loss in directed neural networks. The findings demonstrate that larger and more complex networks exhibit greater resilience to neuron loss, supporting the notion that network topology and size play critical roles in delaying the onset of functional breakdown. The results align with existing empirical evidence, suggesting that cognitive reserve emerges from the intricate interplay of neural connectivity and compensatory mechanisms.

Our model underscores the importance of network complexity as a determinant of resilience and highlights the value of computational simulations in advancing our understanding of brain dynamics. By illustrating how network topology influences robustness, this study contributes to the theoretical foundations of cognitive reserve and offers practical insights into the development of interventions aimed at mitigating neurodegenerative diseases.

However, the model’s limitations, including its reliance on static connectivity and exclusion of neuroplasticity, call for further research incorporating dynamic and biologically realistic features. Future studies integrating computational models with empirical data will be pivotal in elucidating the mechanisms underlying cognitive reserve and translating these insights into clinical applications. Ultimately, this research reinforces the potential of network neuroscience to bridge theoretical and practical domains, offering new perspectives on brain resilience and its implications for health and disease.