Submitted:

05 December 2024

Posted:

06 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.2. Climate Change in Central Europe

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Hymenoptera, Diptera

2.2. Nocturnal Macrolepidoptera

2.3. Butterflies, Rhopalocera

2.4. Mathematical Methods and Data Standardization

2.5. Non Native and Invasive Species, Mediterranean Influx

3. Results

3.1. Hymenoptera

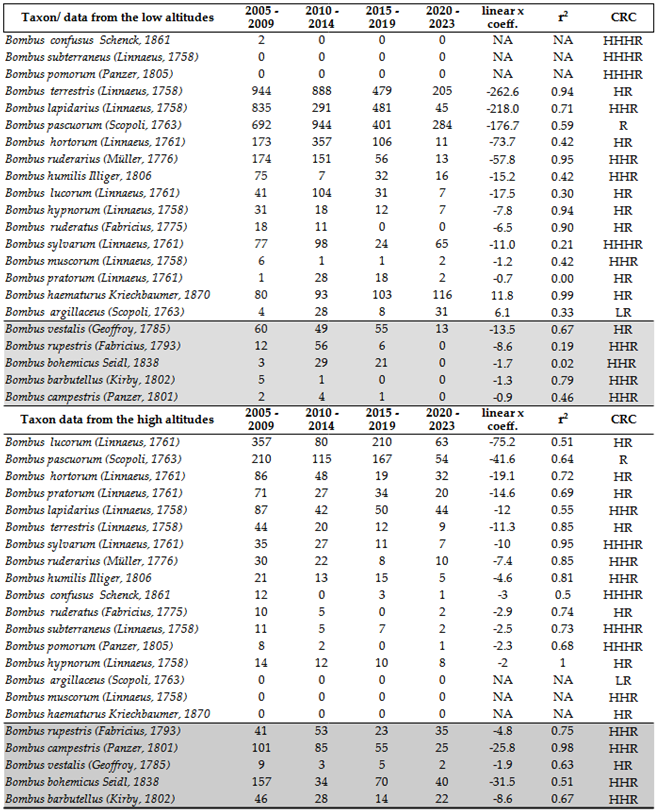

3.1.1. Bumblebees

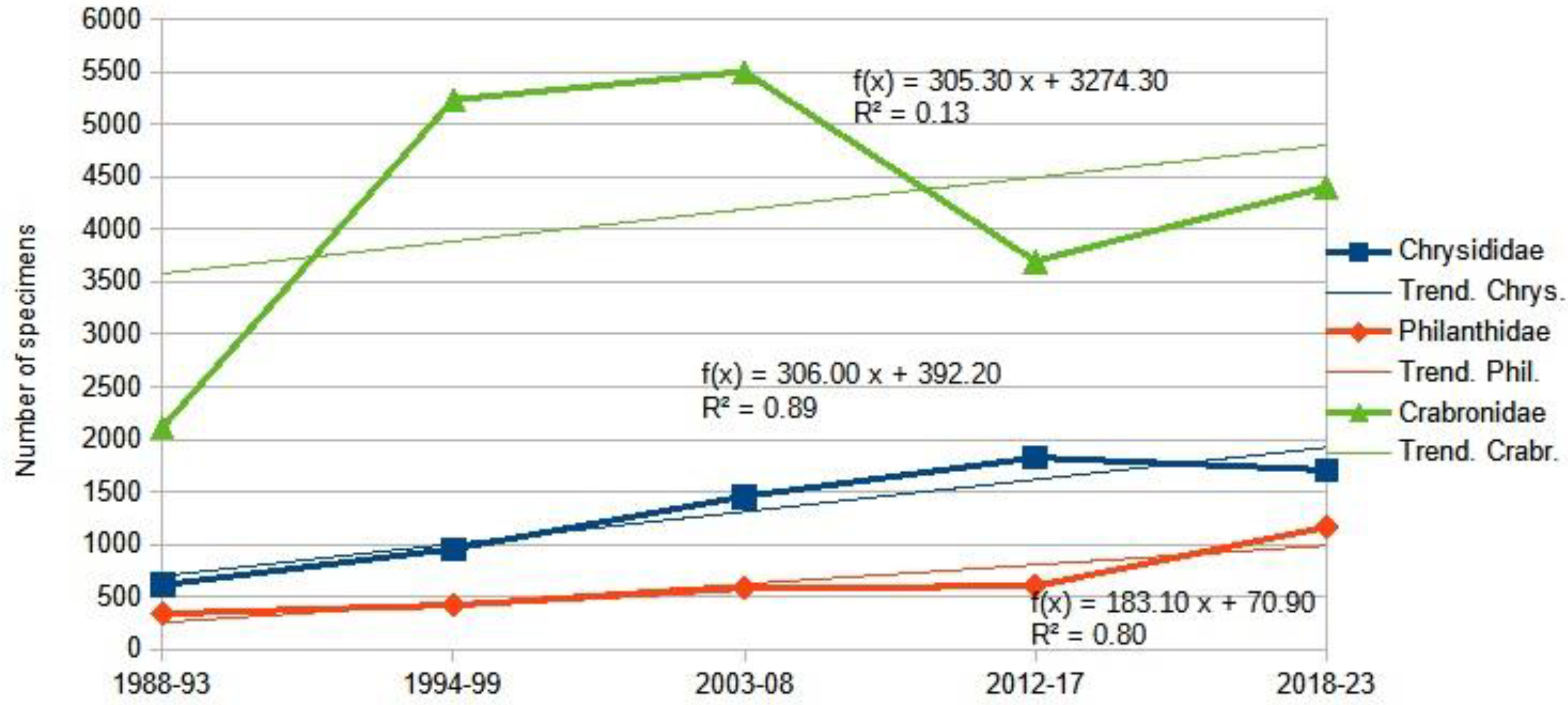

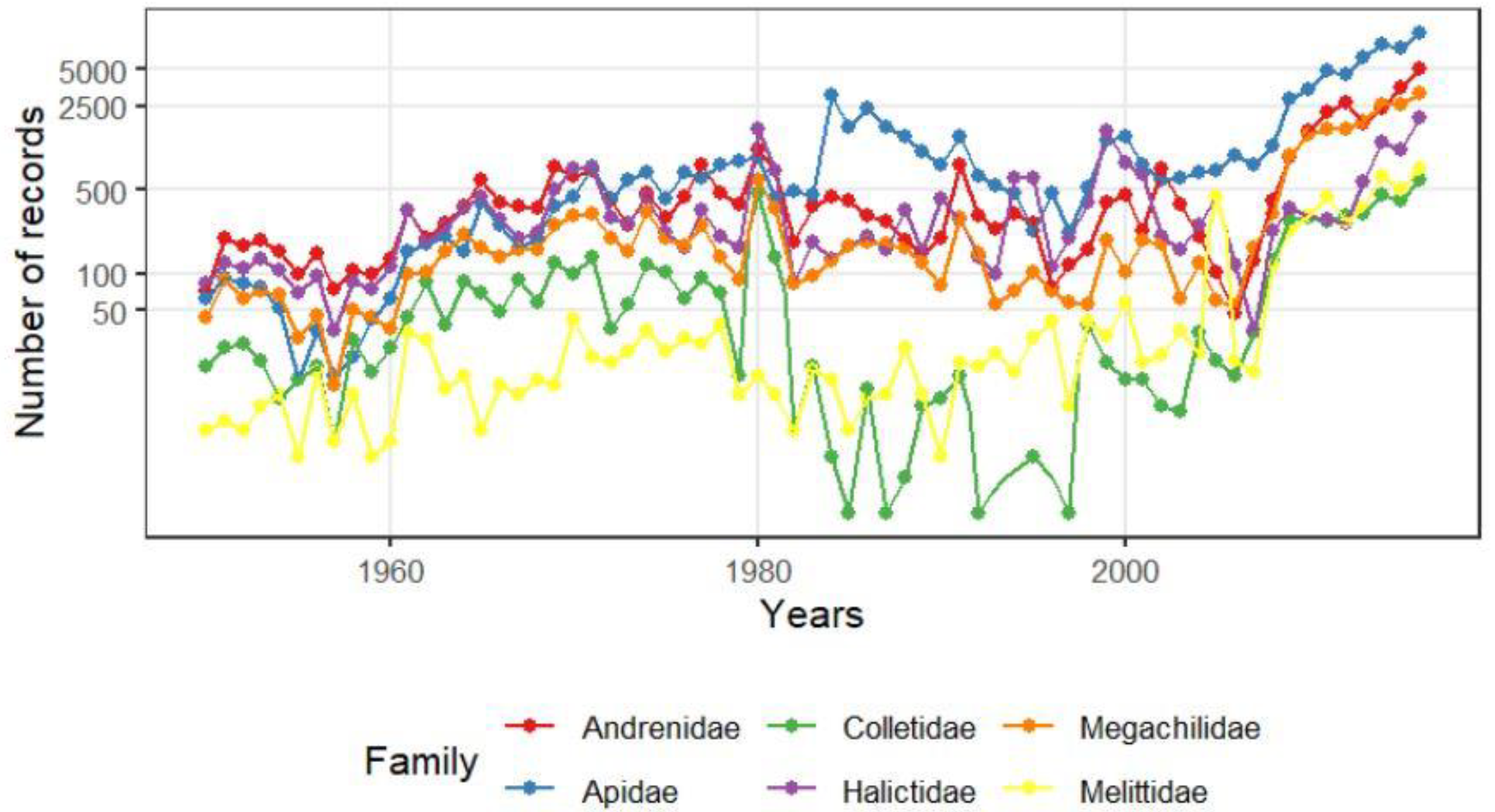

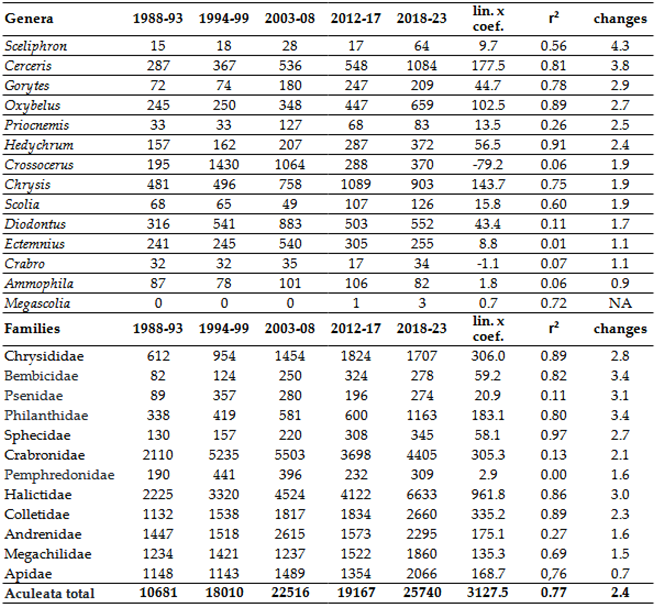

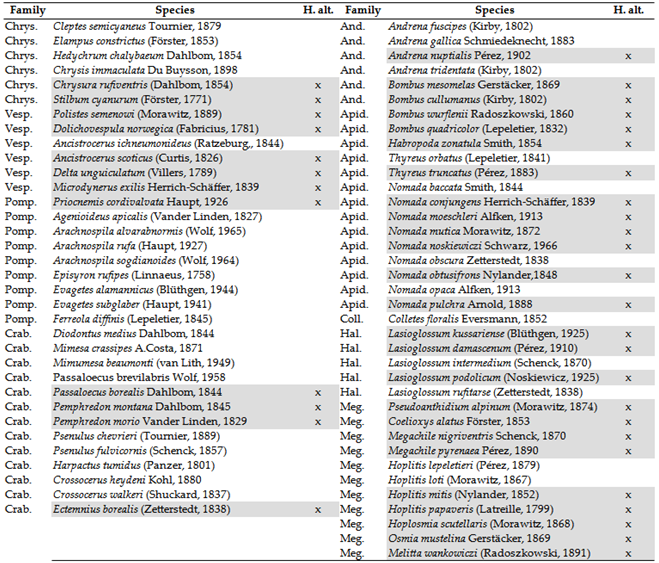

3.1.2. Aculeata

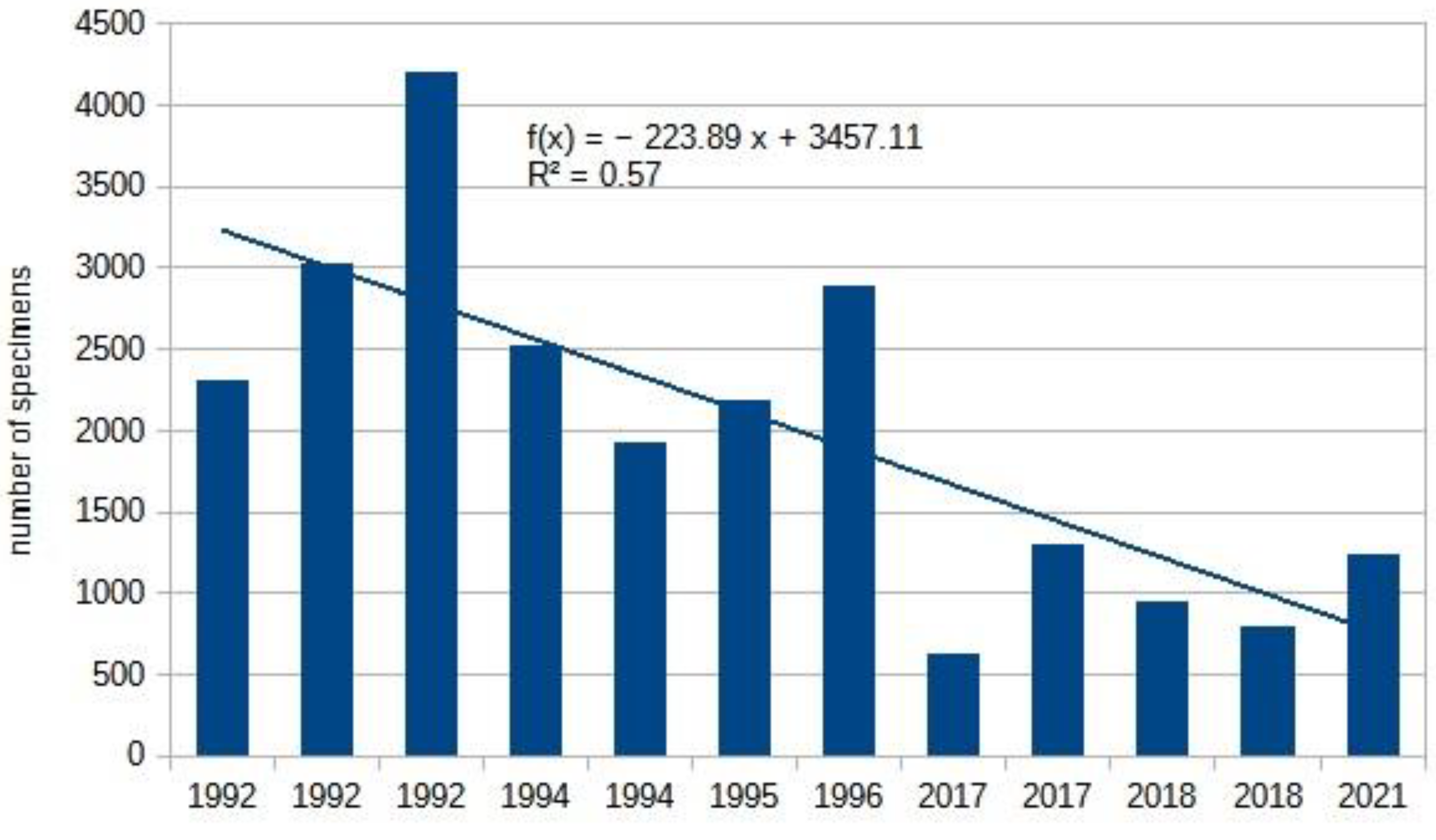

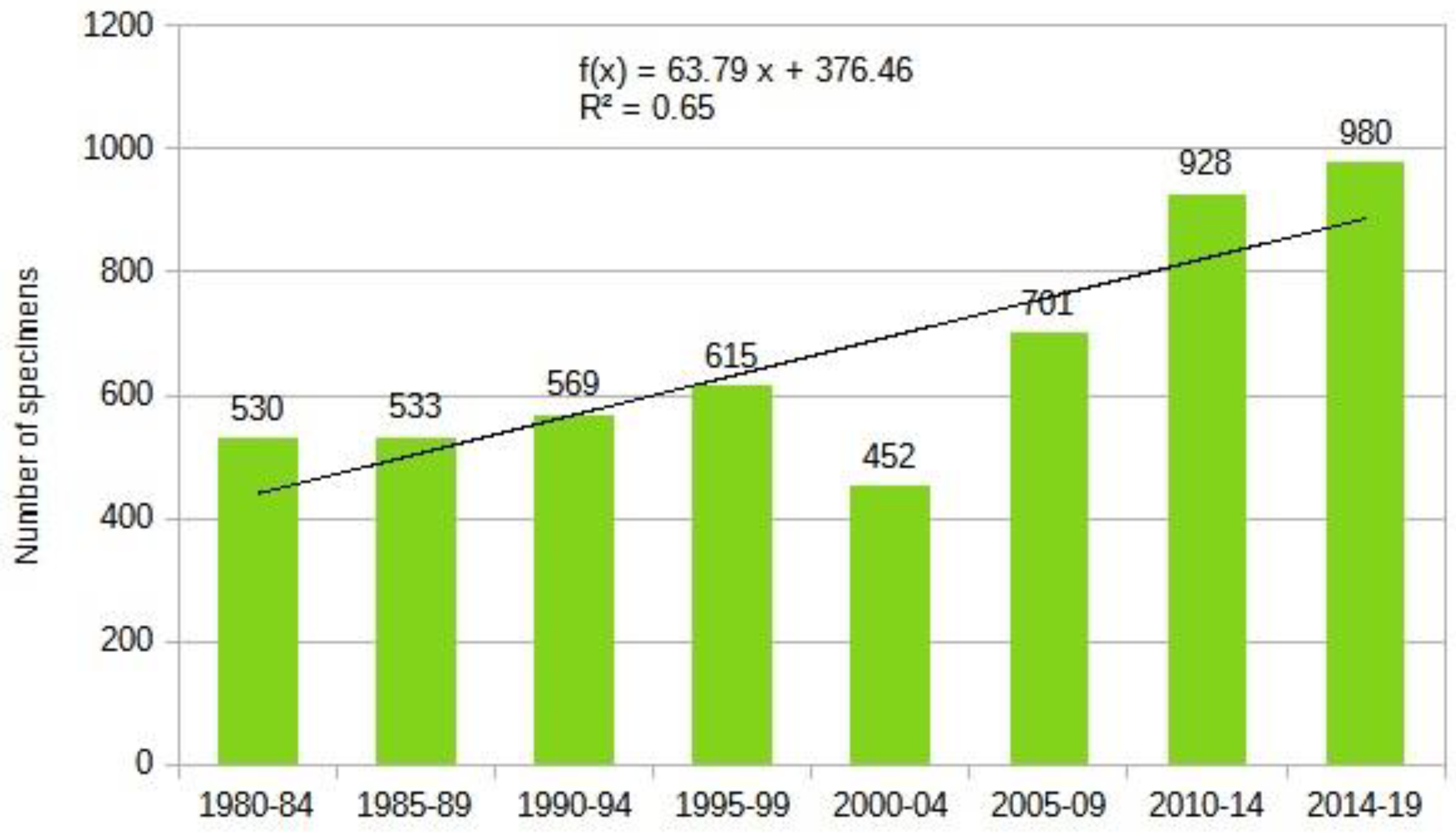

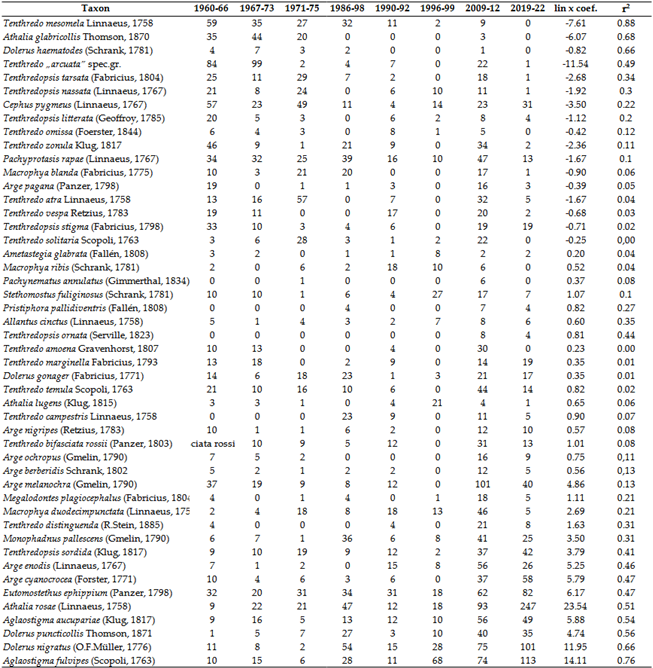

3.1.3. Sawflies, Symphyta

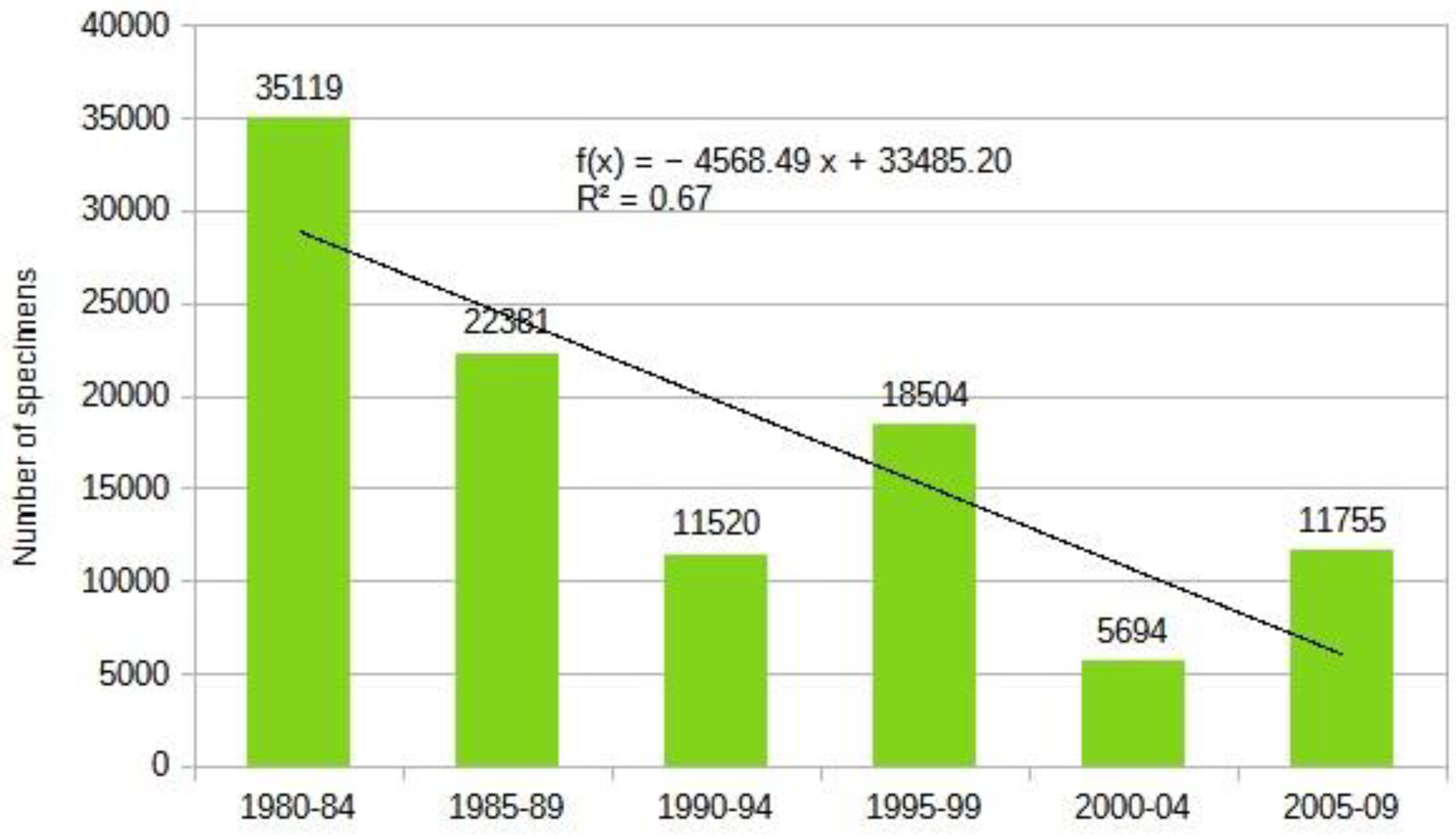

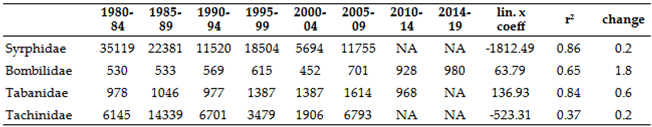

3.2. Diptera

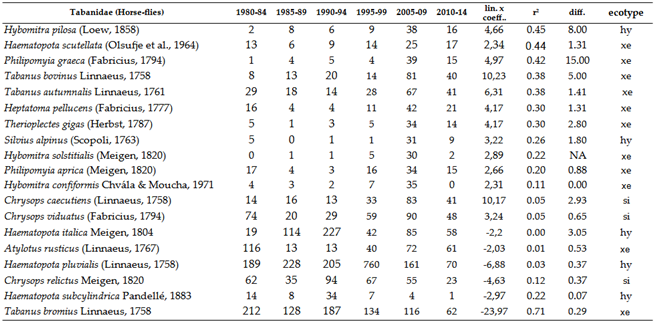

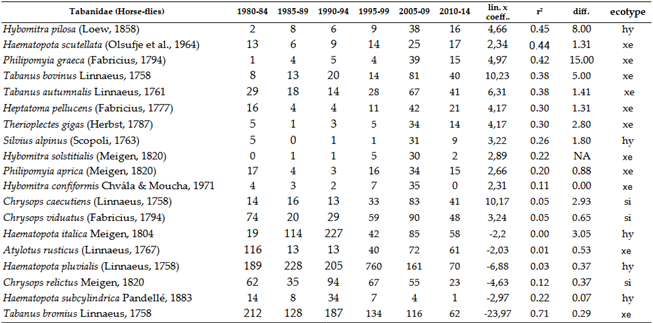

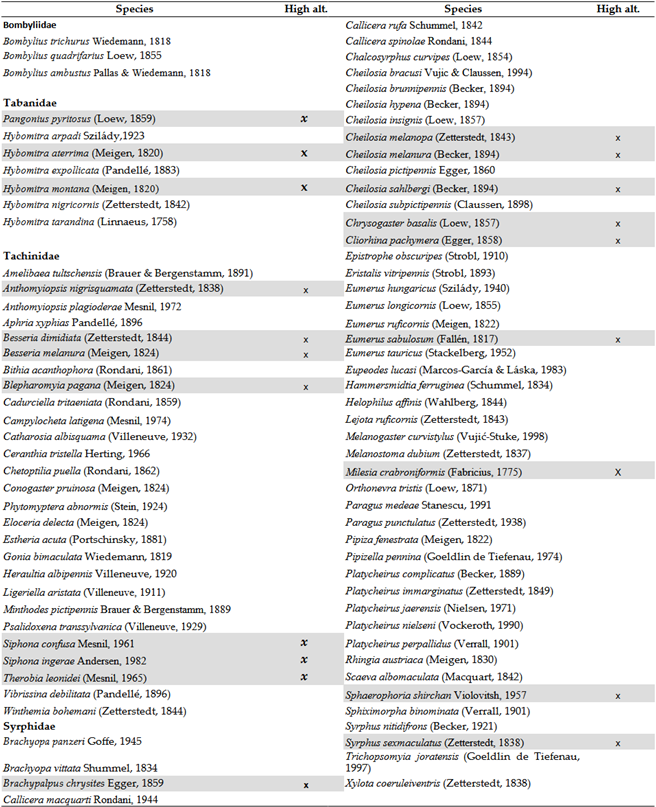

3.2.1. Horse-Flies, Tabanidae

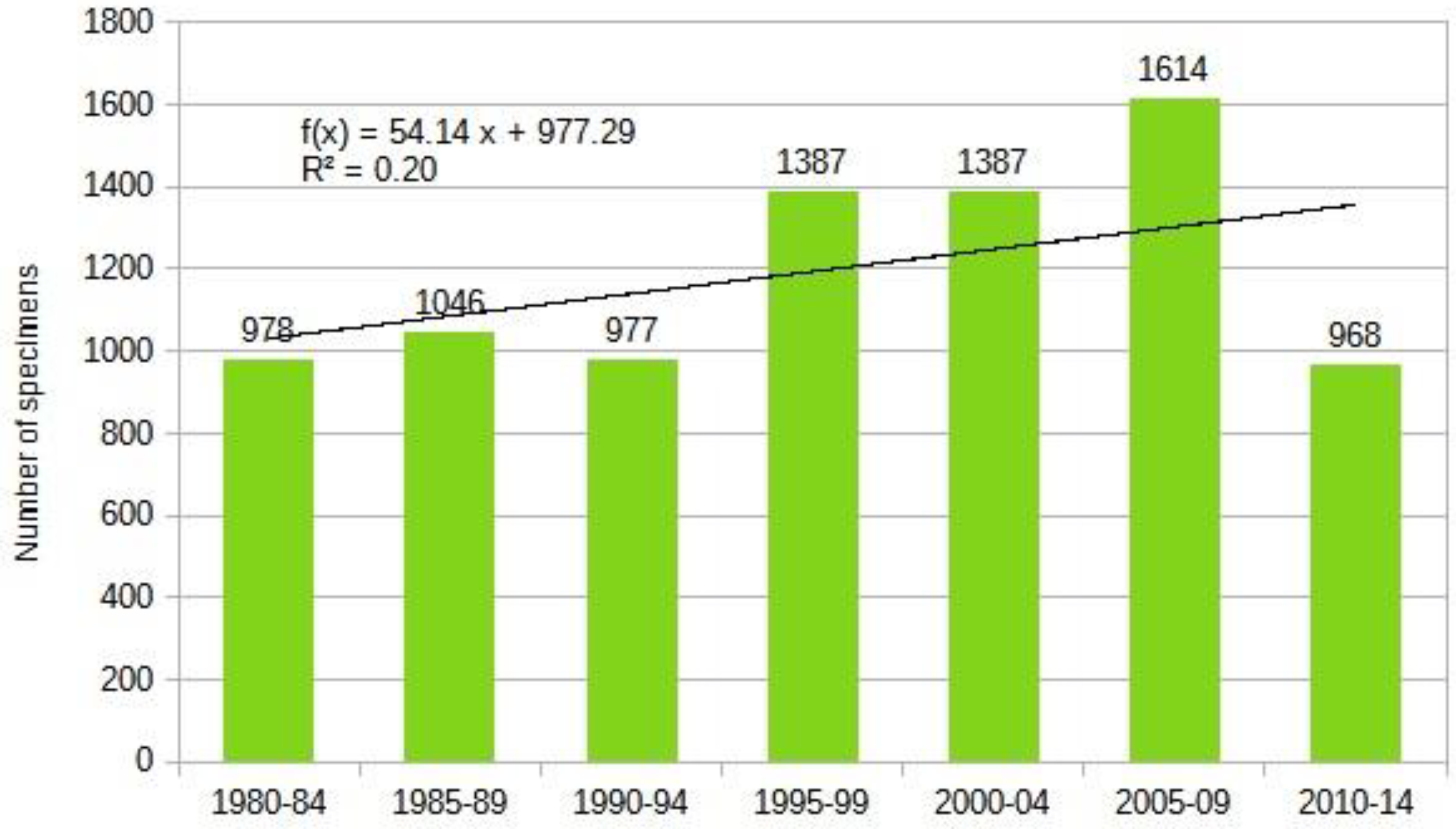

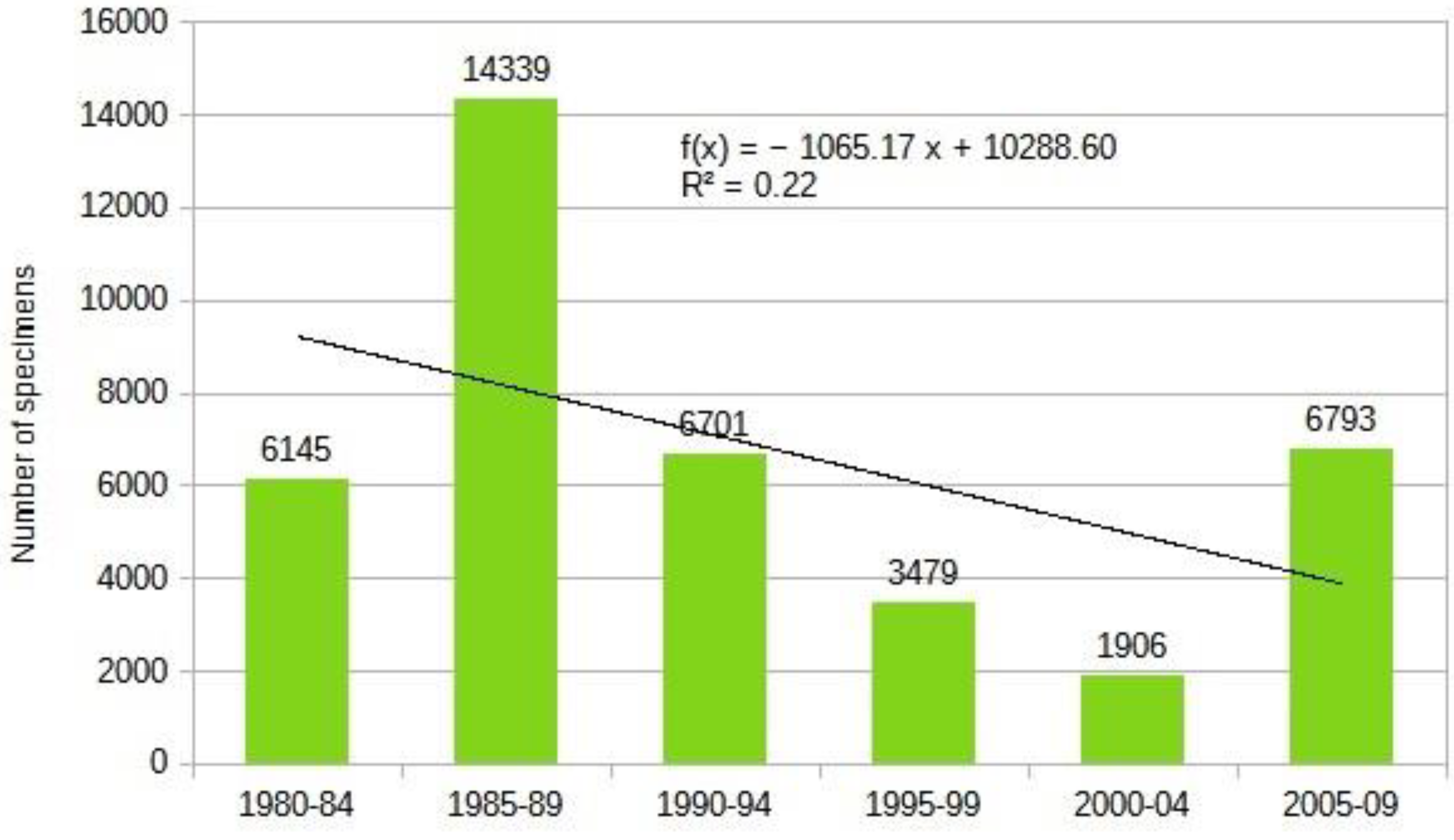

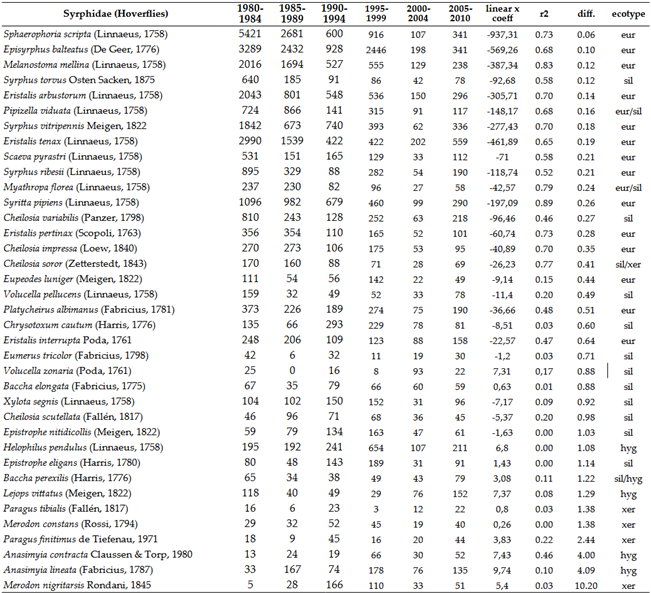

3.2.2. Hoverflies, Syrphidae

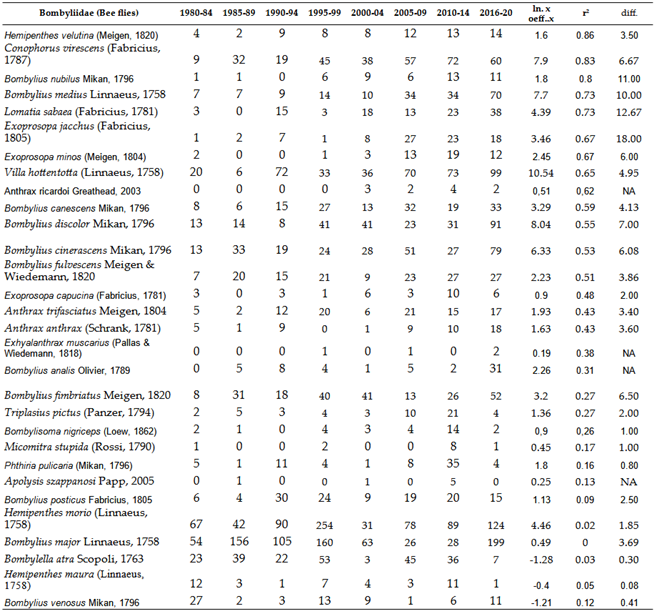

3.2.3. Bee Flies, Bombyliidae

3.2.4. Tachinidae

3.3. Lepidoptera

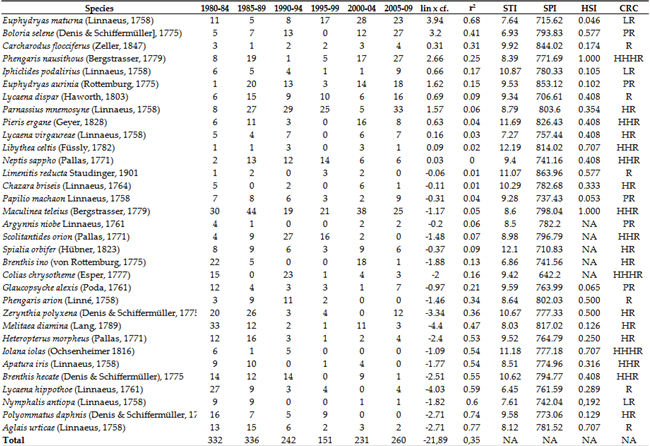

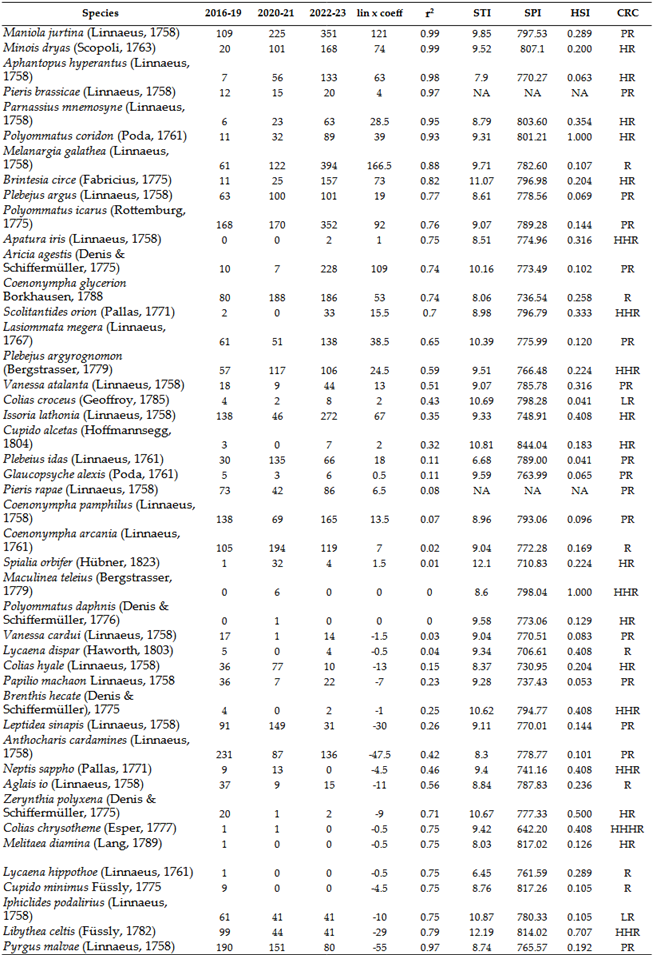

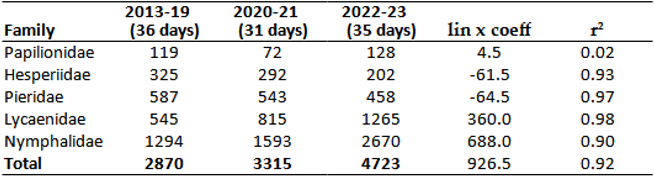

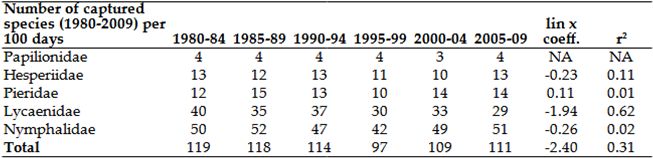

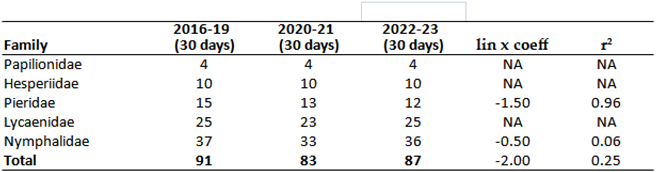

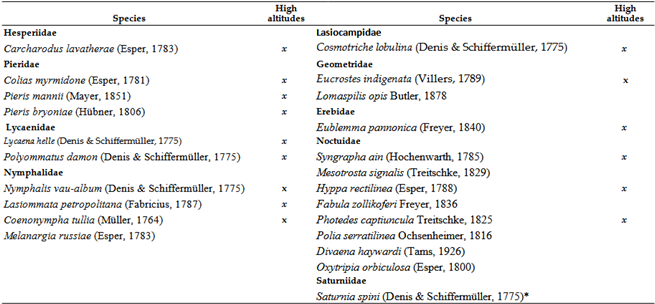

3.3.1. Butterflies, Rhopalocera

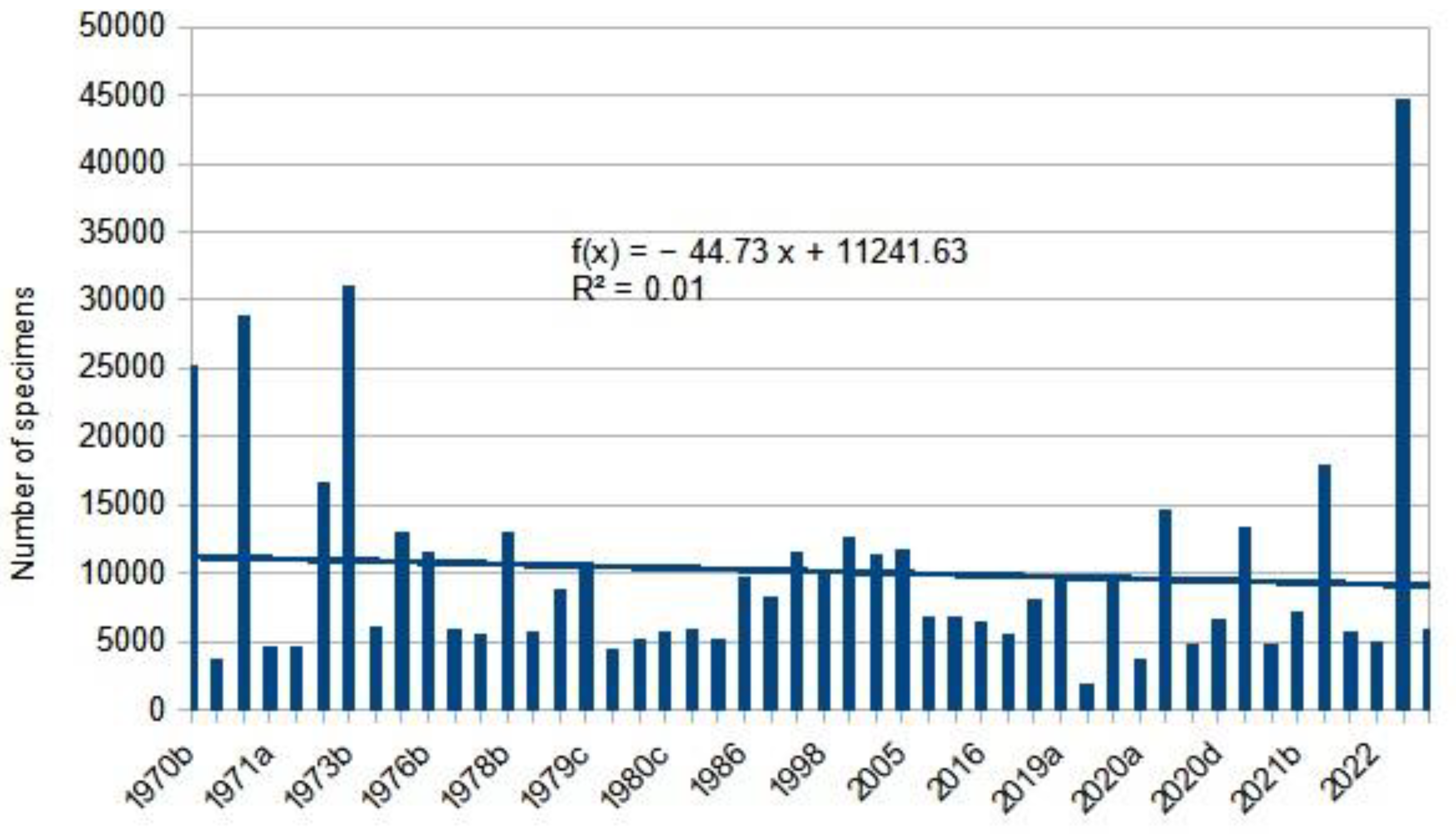

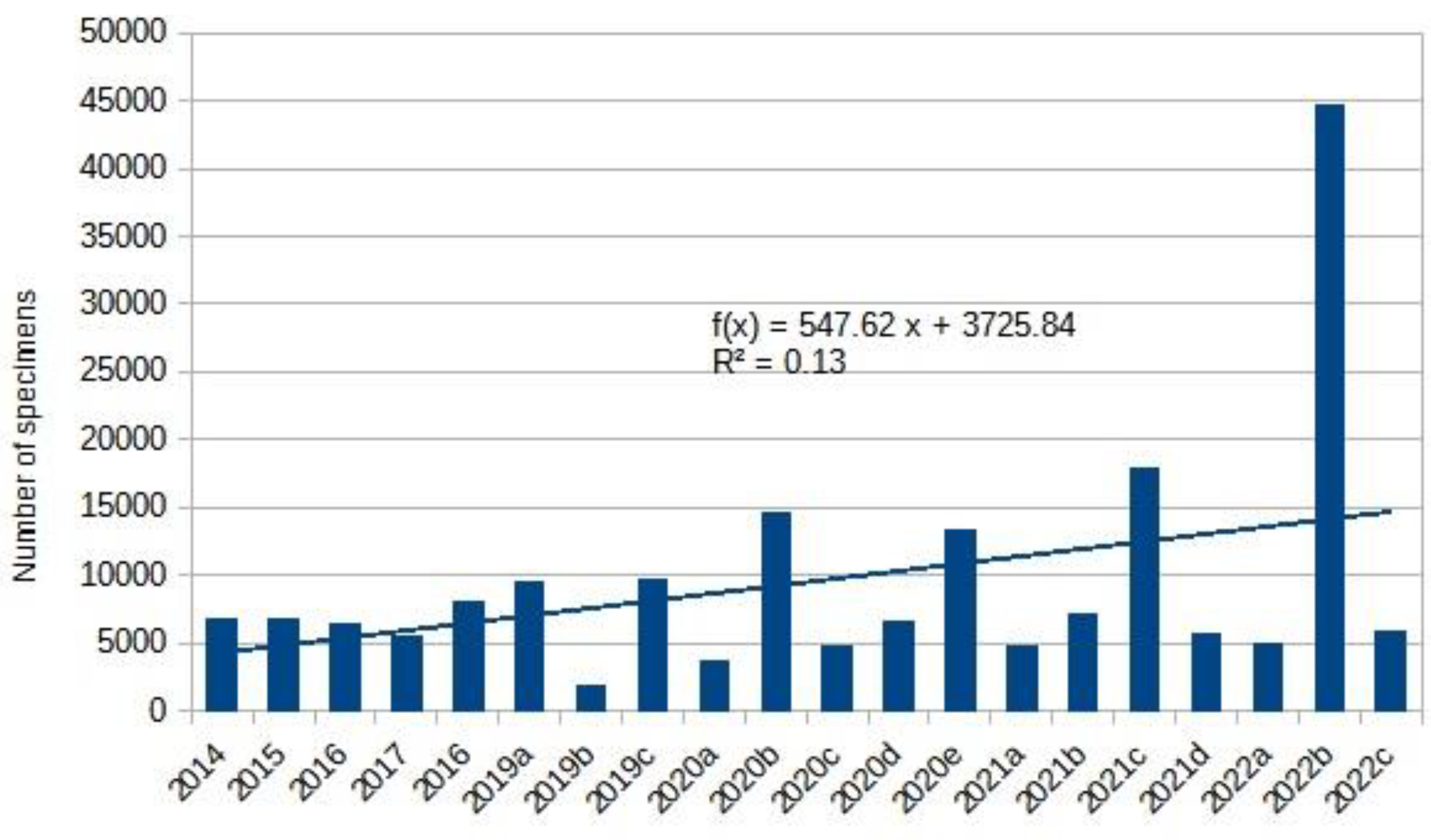

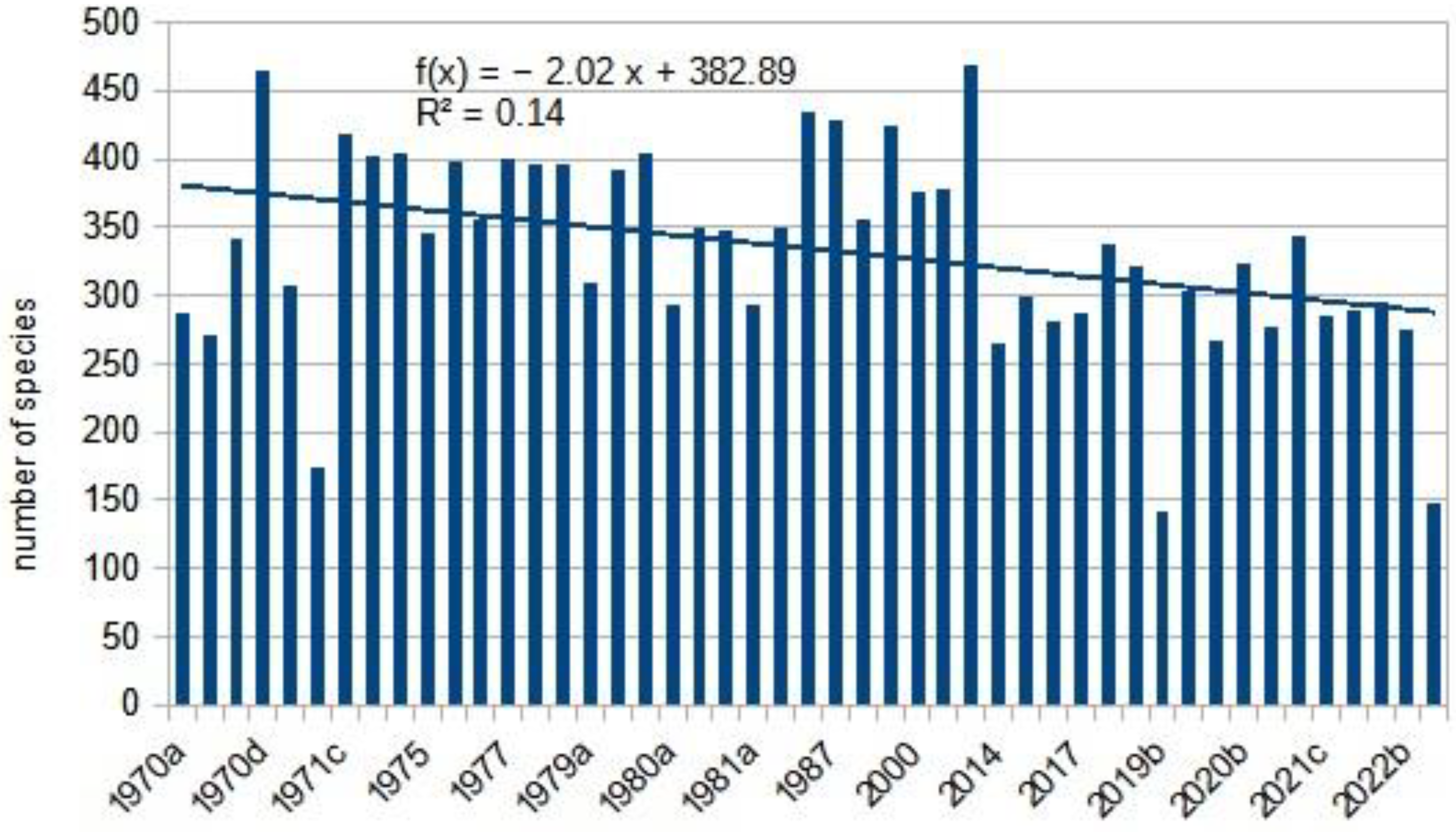

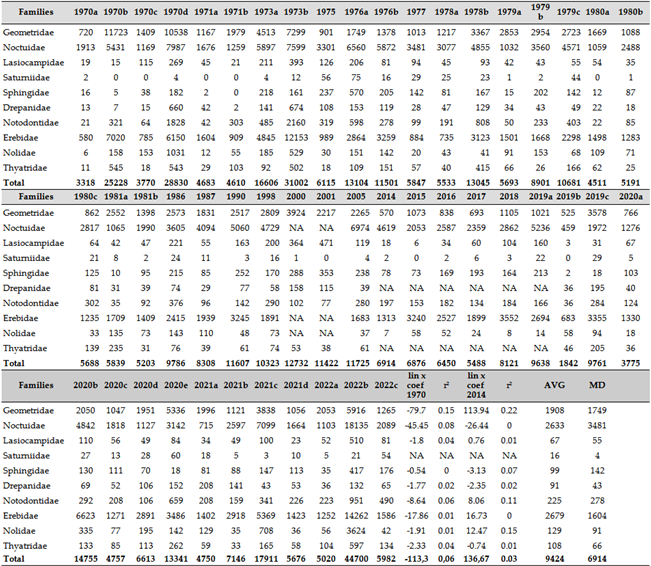

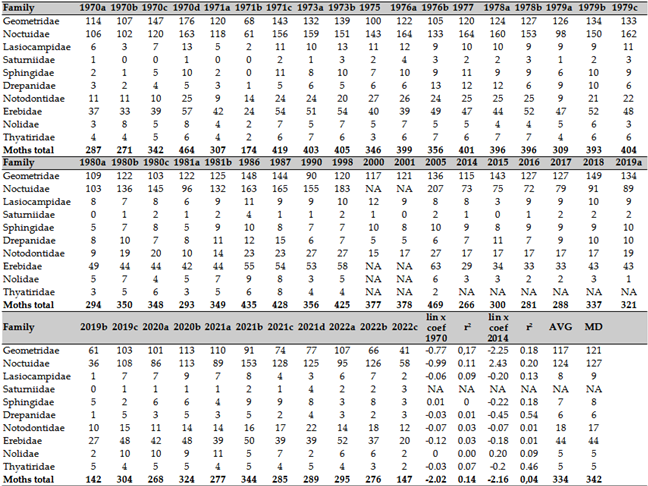

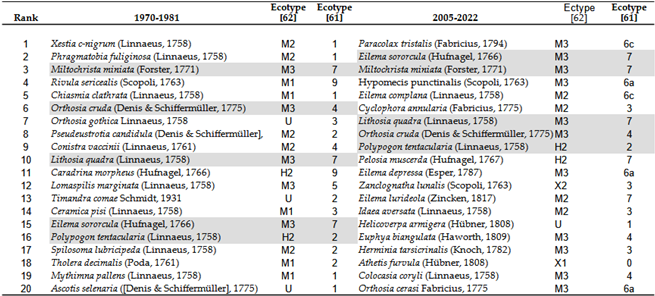

3.3.2. Nocturnal Macrolepidoptera

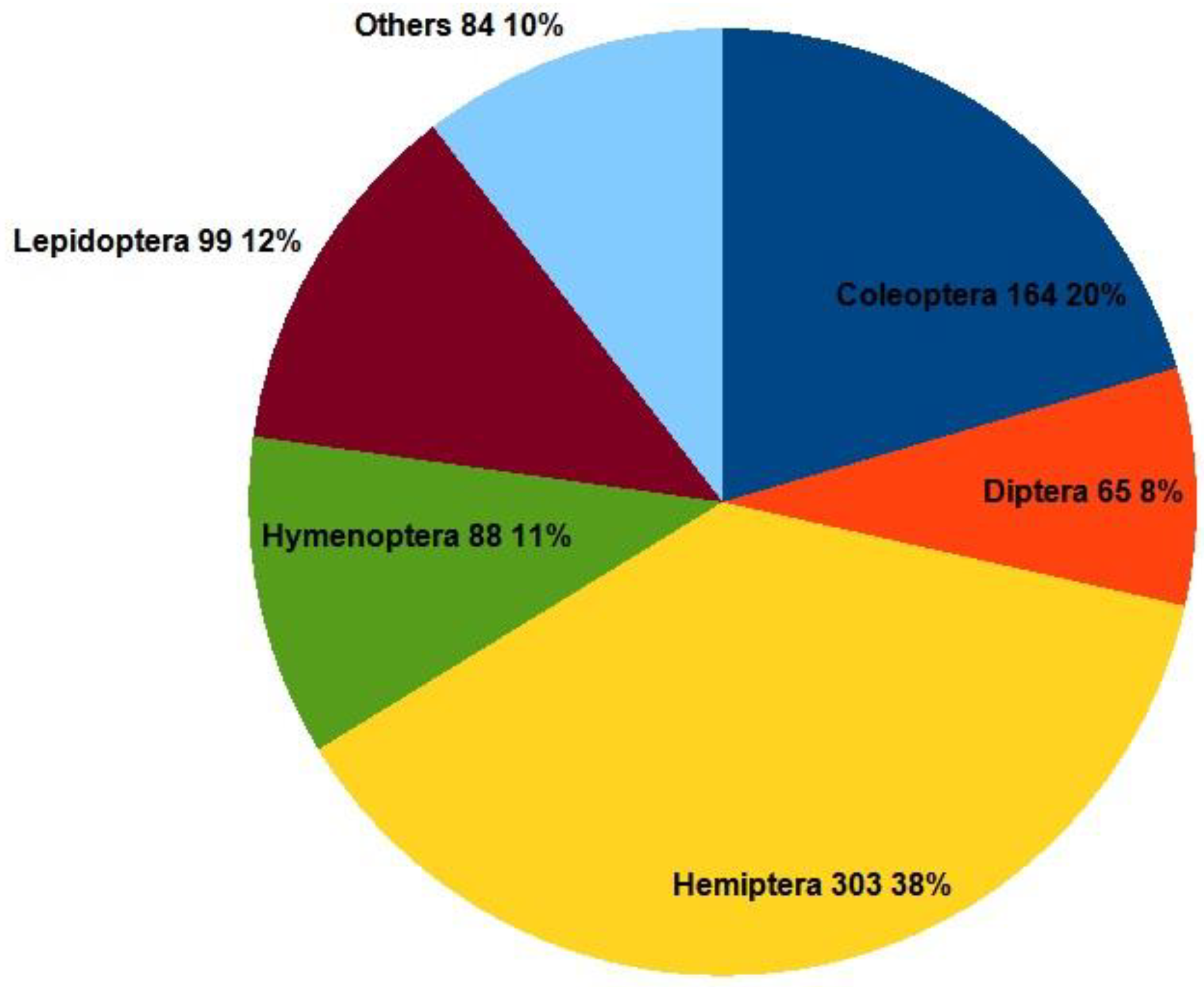

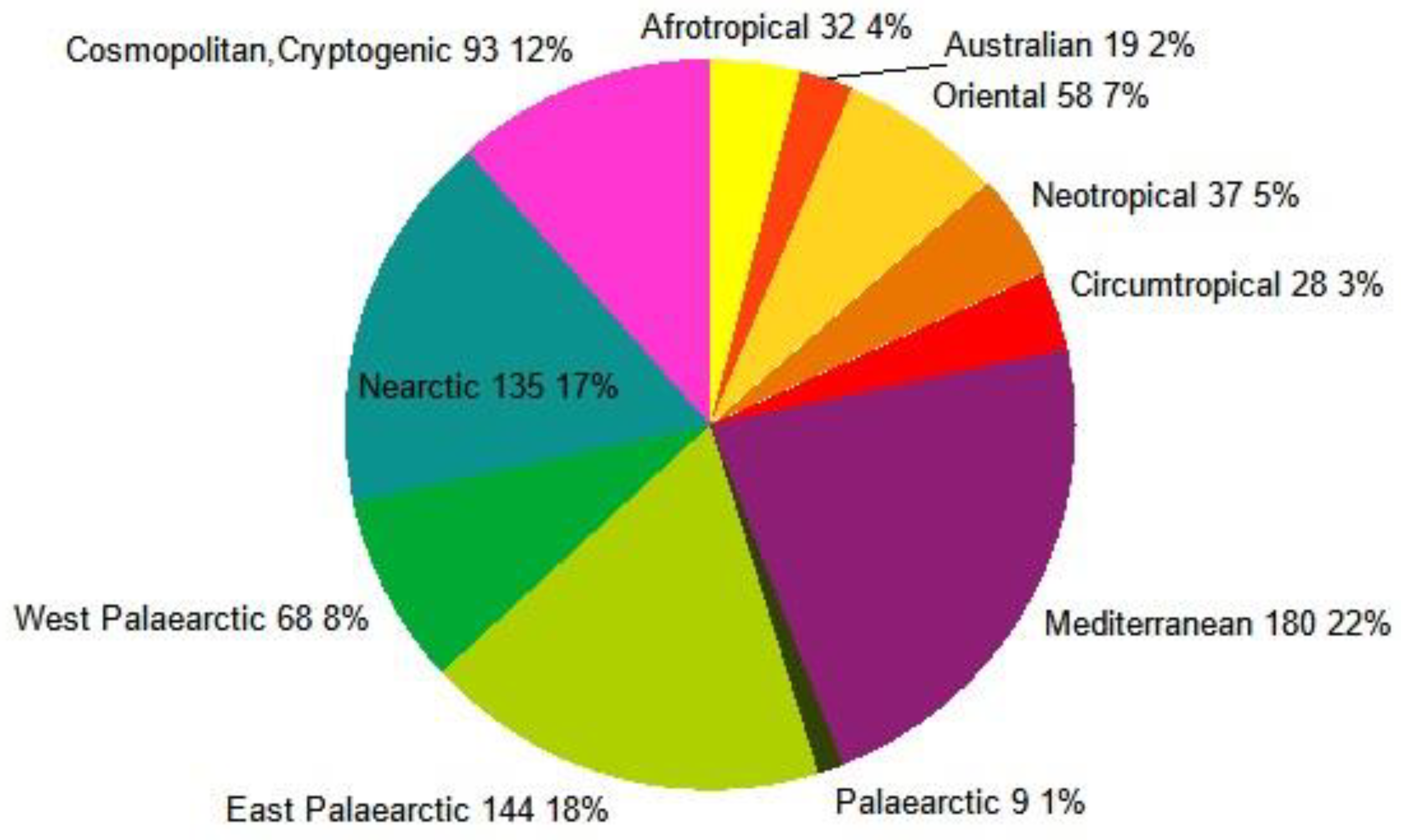

3.4. Non Native Species, Mediterranean Influx

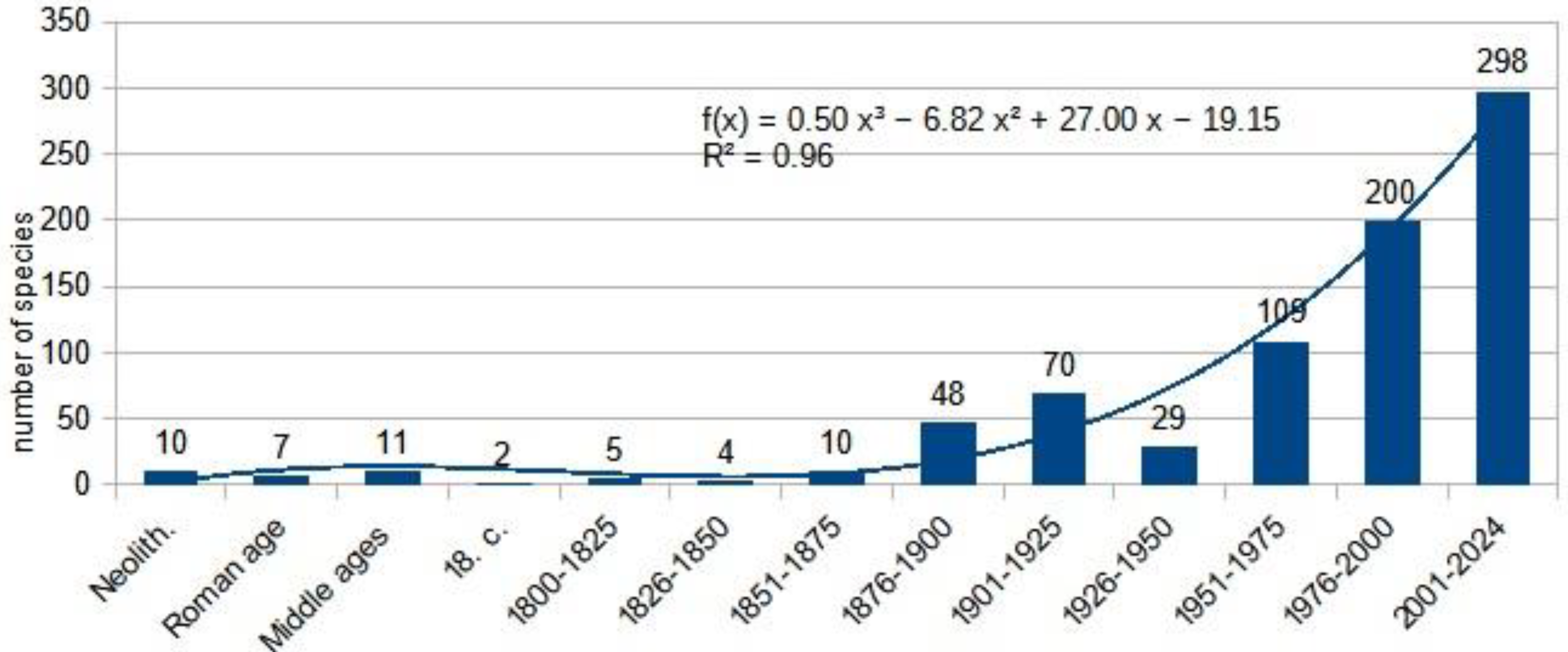

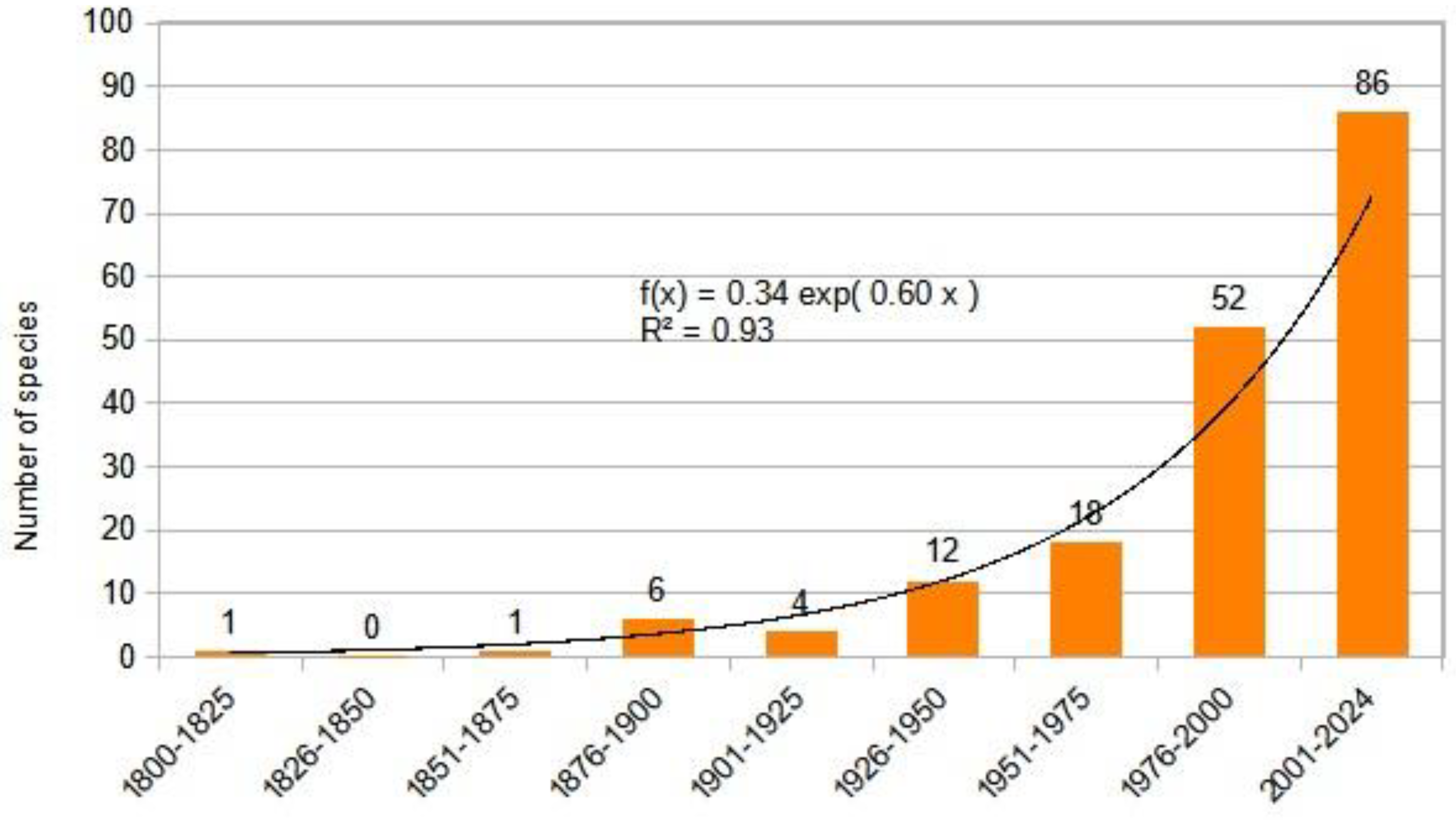

3.4.1. Non Native Species

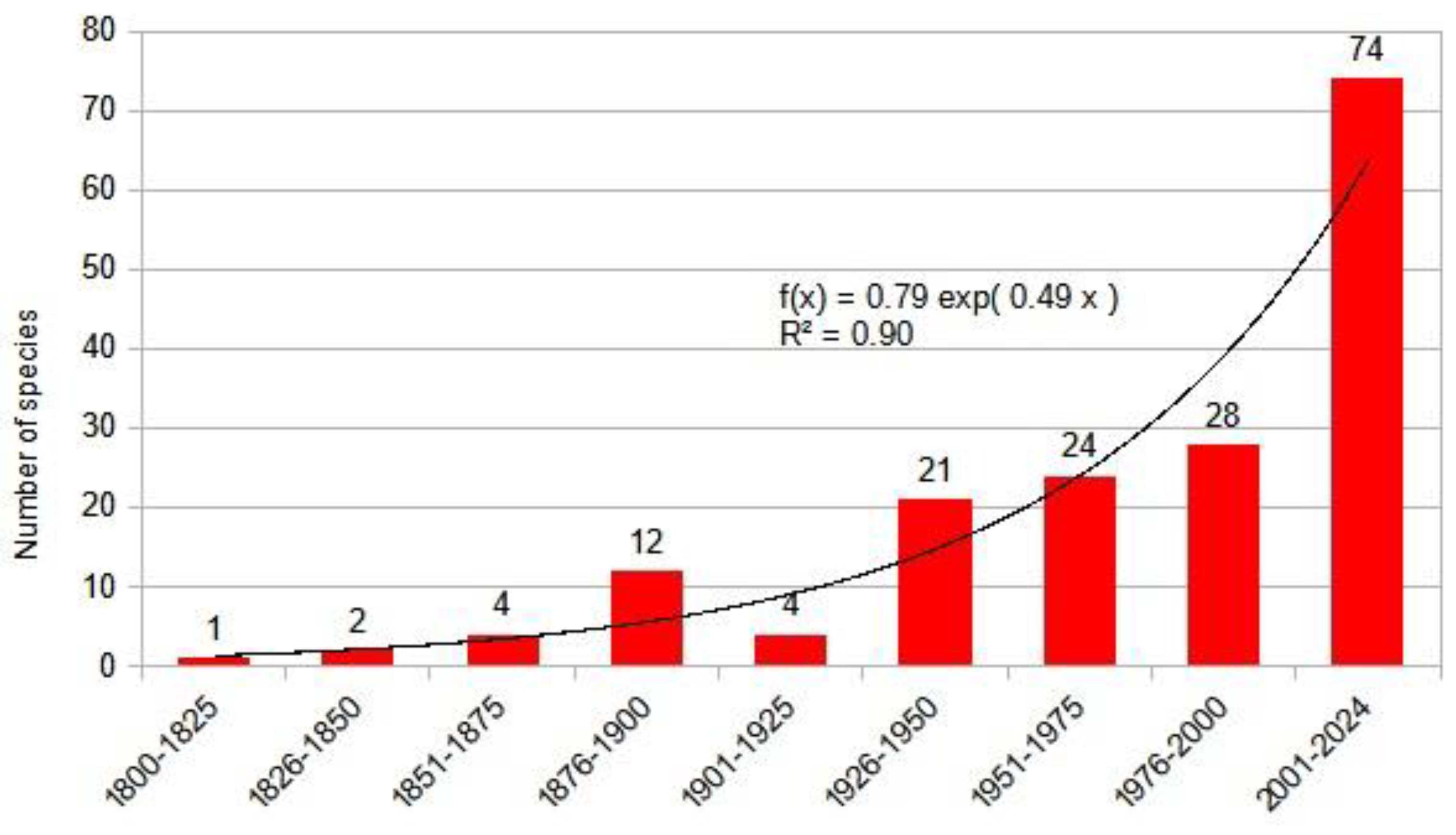

3.4.2. Mediterranean Influx

4. Discussion

4.1. Hymenoptera

4.1.1. Bumblebees

4.1.2. Aculeata

4.1.3. Sawflies, Symphyta

4.2. Diptera

4.2.1. Bombyliidae

4.2.2. Horse-Flies, Tabanidae

4.2.3. Hoverflies, Syrphidae

4.2.4. Tachinid Flies, Tachinidae

4.3. Lepidoptera

4.3.1. Butterflies, Rhopalocera

4.3.2. Moths, Nocturnal Macrolepidoptera

4.4. Alien and Invasive Species, Mediterranean Influx

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Parmesan, C.; Ryrholm, N.; Stefanescu, C.; et al. Poleward shifts in geographical ranges of butterfly species associated with regional warming. Nature. [CrossRef]

- Roy, D. B.; Sparks, T. H. Phenology of British butterflies and climate change. Global Change Biology 2000, 6(4):407-416.

- Shuman, E. K. Global Climate Change and Infectious Diseases. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Med, 1: 2(1).

- Patz, J. A.; Epstein, P. R.; Burke, T. A.; Balbus, J. M. Global climate change and emerging infectious diseases. Jama 1996, 275(3), 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Team eBird European Bee-eaters Expand Their Range Northwards. Last modified June 10, 2022. Available online: https://ebird.org/news/ebird-impacts-european-bee-eaters-expand-their-range-northwards. (accessed on 11. 10. 2024).

- Haris, A.; Józan, Z.; Roller, L.; Šima, P.; Tóth, S. Changes in Population Densities and Species Richness of Pollinators in the Carpathian Basin during the Last 50 Years (Hymenoptera, Diptera, Lepidoptera). Diversity 2024, 16, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency (EEA) Biogeographical regions in Europe. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/figures/biogeographical-regions-in-europe-2 (accessed on 19. 11. 2024).

- Führer, E. A klímaváltozáshoz alkalmazkodó erdõgazdálkodás kihívásai — III. ( Challenges for forest management adapting to climate change – III.). Erdészeti Lapok.

- Gálos, B.; Jacob, D.; Mátyás, Cs. . Effects of Simulated Forest Cover Change on Projected Climate Change – a Case Study of Hungary. Acta Silv. Lign. Hung, 7.

- Sharma, H. C. Biological Consequences of Climate Change on Arthropod Biodiversity and Pest Management. In: International Conference on Insect Science, Bangalore, India, 14-. 17 February.

- Karuppaiah, V.; Sujayanad, G. K. Impact of Climate Change on Population Dynamics of Insect Pests. World Journal of Agr. Sci. 2012, 8(3), 240–246. [Google Scholar]

- Helmholtz-Zentrum für Umweltforschung – UFZ Klimawandel und Biodiversität. Available online: https://www.ufz.de/index.php?de=37140 (accessed on 12. 10. 2024).

- Bauer, T.; Wiblishauser, M.; Gerlach, T. (2022): Wärmeliebende Insekten als Zeiger des Klimawandels – Beispiele und Potenziale bürgerwissenschaftlicher Arterfassungen. Anleigen Natur 2022, 44(1), 141–148. [Google Scholar]

- Bebber, D.; Ramotowski, M.; Gurr, S. Crop pests and pathogens move polewards in a warming world. Nature Clim. Change. [CrossRef]

- Rannow, S.; Neubert, M. Managing Protected Areas in Central and Eastern Europe Under Climate Change. In Ser. Advances in Global Change Research, S: Beniston, M., Publisher, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Szabics, A. Hová folynak el vizeink – a vízhiány okai Magyarországon (Where does our water go – the causes of water shortages in Hungary). Available online: https://www.mnb.hu/letoltes/szabics-andras-zsolt-hova-folynak-el-vizeink-a-vizhiany-okai-magyarorszagon.pdf (accessed on 14. 10. 2024).

- Reich, Gy. Nemzeti Vízstratégia (Kvassay Jenő terv) (National Water Strategy, J. Kvassay Plan). Ludovika University of Public Service, Budapest, Hungary, 2019, pp. 1-57.

- World Bank Group (WBG) Climate Change Knowledge Portal. Available online: https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/ (accessed on 24. 10. 2024).

- Pittioni, B. Die klimaökologische Formel als Hilfsmittel der biogeographischen Forschung. Wetter u. Leben, 1949, 2, 161–167. [Google Scholar]

- Pittioni, B. Das Problem der Formenbildung. Ein Deutungsversuch mit Hilfe der klimaökologischen Formel. Bonner zool. Beitr, -2.

- Hagen, M. D. Zur Schwebfliegenfauna des Raumes Hagen (Diptera, Syrphidae). Abh. Westfäl. Prov.-Mus. Naturk.

- Rasmont, P. , Franzén M., Lecocq T., Harpke A., Roberts S. P. M., Biesmeijer, J. C., Castro, L.; Cederberg, B.; Dvořák, L.; Fitzpatrick Ú.; Gonseth, Y.; Haubruge, E.; Mahé, G.; Manino, A.; Michez, D.; Neumayer, J.; Ødegaard, F.; Paukkunen, J.; Pawlikowski, T.; Potts, S. G.; Reemer, M.; Settele, J.; Straka, J.; Schweiger, O. Climatic Risk and Distribution Atlas of European Bumblebees. Biorisk.

- Lukáš, J.; Tyrner, P. Zlatěnky (Hymenoptera: Chrysididae) Státní přírodní reservace Devínská Kobyla. Klapalekiana 2000, 36, 113–123. [Google Scholar]

- Vepřek, D. První doplněk Check list of Czechoslovak Insects III (Hymenoptera: Sphecidae). Sbor. Pri. Kubu Uher. Hrad. 2000, 5, 233–239. [Google Scholar]

- Bogusch, J.; Straka, J.; Kment, P. Annotated checklist of the Aculeata (Hymenoptera) of the Czech Republic and Slovakia. Acta Ent. Mus Nat Pragae. Suppl. 2007, 11, 1–300. [Google Scholar]

- Deván, P. Kutavky (Sphecidae), hrabavky (Pompilidae), zlatenky (Chrysididae) NPR Tematínska lesostep na lokalite Lúka a v PR Kňaží vrch (Považský Inovec, západné Slovensko) získané Malaiseho pascou v rokoch 1999 - 2000. Nat. Tut. 2004, 8, 143–151. [Google Scholar]

- Smetana, V. Čmele a spoločenské osy (Hymenoptera: Bombini, Polistinae et Vespinae) v poľnohospodárskej krajine Poľany a Podpoľania. Nat. Tut. 2009, 13(1), 107–114. [Google Scholar]

- Smetana, V. Výsledky prieskumu vybraných skupín blanokrídlovcov (Hymenoptera: Aculeata) na Ramsarskej lokalite Poiplie. Acta Mus. Tek. 2010, 8, 71–77. [Google Scholar]

- Smetana, V.; Roller, L.; Beneš, K.; Bogusch, P.; Dvořák, L.; Holý, K.; Karas, Z.; Macek, J.; Straka, J.; Šima, P.; Tyrner, P.; Veprěk, D.; Zeman, V. Blanokrídlovce (Hymenoptera) na vybraných,lokalitách Borskej nížiny. Acta Mus. Tek. 2010, 8, 78–111. [Google Scholar]

- Smetana, V.; Šima, P.; Bogusch, P.; Erhart, J.; Holý, K.; Macek, J.; Roller, L.; Straka, J. Blanokrídlovce (Hymenoptera) na vybraných lokalitách v okolí Levíc a Kremnice. Act. Mus. Tek. 2015, 10, 44–68. [Google Scholar]

- Šima, P.; Straka, J. First records of Heriades rubicola Pérez, 1890 (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae) and Nomada moeschleri Alfken, 1913 (Hymenoptera: Apidae) from Slovakia. Ent. Carpath. 2016, 28(1), 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Tyrner, P.; Majzlan, O. Zlatěnkovití (Hymenoptera: Chrysididae) Pohoří Burda a jeho okolí. Ochr. pr., Banská B, 27.

- Smetana, V.; Roller, L.; et al. Blanokrídlovce (Hymenoptera) na vybraných lokalitách v CHKO Malé Karpaty. Act. Mus. Tek. 2020, 12, 75–141. [Google Scholar]

- Tóth, S. Magyarország zengőlégy faunája (Diptera, Syrphidae). Hoverflies of Hungary (Diptera, Syrphidae). e-Acta Nat. Pan.

- Tóth, S. Magyarország fürkészlégy faunája (Diptera, Tachinidae). Tachinid flies of Hungary (Diptera, Tachinidae). e-Acta Nat. Pan.

- Fazekas, I.; Tóth, S. A hazai bögölyök nyomában (Diptera, Tabanidae). Horse-flies of Hungary (Diptera, Tabanidae). Pannon Intézet, Pécs, Hungary 2023, pp. 1-124.

- Zombori, L. Sawflies from Fertő-Hanság National Park (Hymenoptera, Symphyta). In The Fauna of the Fertő-Hanság National Park; Mahunka, S. Ed.; Publisher, Hungarian Natural History Museum, Budapest, Hungary 2002; pp. 545-552.

- Haris, A. Sawflies of the Zselic Hills, SW Hungary Hymenoptera, Symphyta. Nat. Som. 2009, 15, 127–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haris, A. Sawflies of the Vértes Mountains Hymenoptera, Symphyta. Nat. Som. 2010, 17, 209–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haris, A. Sawflies of the Börzsöny Mountains North Hungary Hymenoptera, Symphyta. Nat. Som. 2011, 19, 149–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haris, A. Sawflies of Belső-Somogy (Hymenoptera, Symphyta). Nat. Som. 2012, 22, 141–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haris, A. Second contribution to the sawflies of Belső Somogy Hymenoptera, Symphyta. Nat. Som. 2018, 31, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haris, A. Sawflies from Külső-Somogy, South-West Hungary (Hymenoptera, Symphyta). Nat. Som. 2018, 32, 147–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haris, A. Sawflies of the Keszthely Hills and its surroundings. Nat. Som. 2019, 33, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haris, A. Sawflies of Southern part of Somogy county Hymenoptera, Symphyta. Nat. Som. 2020, 35, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haris, A. Sawflies of the Cserhát Mountains Hymenoptera, Symphyta. Nat. Som. 2021, 37, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haris, A. Second contribution to the knowledge of sawflies of the Zselic Hills (Hymenoptera, Symphyta). A Kaposvári Rippl-Rónai Múzeum Közleményei (Commun. Rippl-Rónai Mus. Kaposvár). [CrossRef]

- Haris, A.; Vidlička, L.; Majzlan, O.; Roller, L. Effectiveness of Malaise trap and sweep net sampling in sawfly research (Hymenoptera, Symphyta). Biologia 2024, 79, 1705–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zombori, L. A Bakonyi Természettudományi Múzeum levéldarázs-gyűjteménye (Hymenoptera, Symphyta) I. (The collection of sawflies (Hymenoptera, Symphyta) of the Bakony Natural History Museum I.). Veszprém m. múz. közl.

- Zombori, L. A Bakonyi Természettudományi Múzeum levéldarázs-gyűjteménye (Hymenoptera, Symphyta) II. (The collection of sawflies (Hymenoptera, Symphyta) of the Bakony Natural History Museum II.). Veszprém m. múz. Közl, 14.

- Zombori, L. A Bakonyi Természettudományi Múzeum levéldarázs-gyűjteménye (Hymenoptera, Symphyta) III. (The collection of sawflies (Hymenoptera, Symphyta) of the Bakony Natural History Museum III.). Veszprém m. múz. Közl, 15.

- Zombori, L. A Bakonyi Természettudományi Múzeum levéldarázs-gyűjteménye (Hymenoptera, Symphyta) IV. (The collection of sawflies (Hymenoptera, Symphyta) of the Bakony Natural History Museum IV.). Fol. Mus. Hist. Nat. Bakonyiensis.

- Józan, Z. A Zselic darázsfaunájának (Hymenoptera, Aculeata) állatföldrajzi és ökofaunisztikai vizsgálata. Zoologeographic and ecofaunistic study of the Aculeata fauna (Hymenoptera, Aculeata) of Zselic. Somogyi Múzeumok Közleményei.

- Józan, Z. A Béda-Karapancsa Tájvédelmi Körzet fullánkos hártyásszárnyú (Hymenoptera, Aculeata) faunájának alapvetése. Aculeata (Hymenoptera, Aculeata) fauna of the Béda-Karapancsa Landscape Protection Area. Dunántúli Dolg. Természettudományi Sor, 6.

- Józan, Z. A Baláta környék fullánkos hártyásszárnyú faunájának (Hym., Aculeata) alapvetése. Aculeata fauna of Lake Baláta (Hym., Aculeata). Somogyi Múzeumok Közleményei.

- Józan, Z. A Mecsek kaparódarázs faunájának (Hymenoptera, Sphecoidea) faunisztikai, állatföldrajzi és ökofunisztikai vizsgálata. Faunistical, zoogeographical and ecofaunistical investigation on the Sphecoids fauna of the Mecsek Montains (Hymenoptera, Sphecoidea). Nat. Som, 3.

- Józan, Z. A Barcsi borókás fullánkos faunája, III. (Hymenoptera, Aculeata). Aculeata fauna of Barcs Juniper Woodland (Hymenoptera, Aculeata). Nat. Som, 26.

- Infusino, M.; Brehm, G.; Di Marco, C.; Scalercio, S. Assessing the efficiency of UV LEDs as light sources for sampling the diversity of macro-moths (Lepidoptera). Eur. J. Entomol. 2017, 114, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Liang, G.; Lu, Y. Response of Different Insect Groups to Various Wavelengths of Light under Field Conditions. Insects 2021, 12, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Langevelde, F.; Ettema, J. A.; Donners, M. Wallis De Vries, M. F.; Groenendijk, D. Effect of spectral composition of artificial light on the attraction of moths. Biol. Cons. 2011, 144(9), 2274-2281.

- Sage, W.; Utschick, H. Nachtfalter (Lepidoptera, Macroheterocera) im NSG "Untere Alz" und ihre Bedeutung für die Pflege- und Entwicklungsplanung. Berichte der Anl. 1997, 21, 149–177. [Google Scholar]

- Kanarskyi, Y.; Geriak, Y.; Lashenko, E. Ecogeographic structure of the Moth fauna in upper Tisa River basin. Transylv. Rev. Syst. Ecol. Res. 2011, 11, 143–168. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, J.L.; McCollin, D. The value of museum and other uncollated data in reconstructing the decline of the chequered skipper butterfly Carterocephalus palaemon (Pallas, 1771). J. Nat. Sci. Coll. 2022, 10, 31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, C. L.; Guralnick, R. P.; Zipkin, E. F. Challenges and opportunities for using natural history collections to estimate insect population trends. J. Anim Ecol. 2023, 92(2), 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGie, H.; Hancock, G.; Reilly, M.; Robinson, J.; Riddington, K.; Brown, C.; Machin, R.; et al. Museum collections and biodiversity conservation. Publisher: Curating Tomorrow, Liverpool, UK, 2019; pp. 1-104.

- McDermott, A. To understand the plight of insects, entomologists look to the past. PNAS News Feature 2020, 118(2), e2018499117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeppsson, T.; Lindhe, A.; Gardenfors, U.; Forslund, P. The use of historical collections to estimate population trends, A case study using Swedish longhorn beetles (Coleoptera, Cerambycidae). Biol. Cons. 2010, 143, 1940–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, M. A. Identifying declining and threatened species with museum data. Biol. Cons. 1998, 83(1), 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K. A. Museum Collections - Resources for Biological Monitoring. frican Invertebrates. [CrossRef]

- Nowicki, P.; Settele, J.; Henry, P. Y; Woyciechowskia, M. Butterfly Monitoring Methods, The ideal and the Real World. Isr. J. Ecol. Evol. 2008, 54, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settele, J.; Kudrna, O.; Harpke, A.; Kühn, I.; van Swaay, Ch.; Verovnik, R.; Warren, M.; Wiemers, M.; Hanspach, J.; Hickler, Th.; Kühn, E.; Halder, I.; Veling, K.; Vliegenthart, A.; Wynhoff, I.; Schweiger, O. Climatic Risk Atlas of European Butterflies. Biorisk.

- Schweiger, O.; Harpke, A.; Wiemers, M.; Settele, J. Climber, climatic niche characteristics of the butterflies in Europe. ZooKeys 2014, 367, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, A.; Wilby, A.; Menéndez, R. South European mountain butterflies at a high risk from land abandonment and amplified effects of climate change. Insect Cons. and Div. 2023, 16(6), 838–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudrna, O.; Harpke, A.; Lux, K. , Pennerstorfer, J.; Schweiger, O., Ed.; Settele, J. et al. Distribution Atlas of Butterflies in Europe. Publisher: Gesellschaft für Schmetterlingschutz, Halle, Germany, 2011; pp. 1–576. [Google Scholar]

- Roques, A; Marc Kenis, M.; Lees, D.; Lopez-Vaamonde, C.; Rabitsch, W.; Rasplus, J-Y.; Roy, D. B. Alien terrestrial arthropods of Europe. Biorisk, 1028.

- Brewer, S. ; Cheddadi,R.; de Beaulieu, J. L.; Reille, M. The spread of deciduous Quercus throughout Europe since the last glacial period. For. Ecol. Manage.

- Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) Available online:. Available online: https://www.gbif.org (accessed on 26. 11. 2024).

- Panagiotakopulu, E.; Buckland, P. C. Early invaders - Farmers, the granary weevil and other uninvited guests in the Neolithic. Biological Invasions. [CrossRef]

- Ripka, G. Checklist of the Aphidoidea and Phylloxeroidea of Hungary (Hemiptera, Sternorrhyncha). Folia ent. Hung. 2008, 69, 19–157. [Google Scholar]

- Zahradnik, P. A Check-list of Ptinidae (Coleoptera, Bostrichoidea) of the Balkan Peninsula. Fol. Heyrovskyana, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Soós, A. Über die Sepsiden, Piophiliden und Drosophiliden des Karpatenbeckens. Fragm. faun. Hung. 1945, 8(1-4), 18-29.

- Ripka, G. Jövevény kártevő ízeltlábúak áttekintése Magyarországon I. (Overview of non-native insect pest arthropods in Hungary I.) Növényvédelem 2010, 46(2), 45-58.

- Skuhrava, M.; Skuhrava, V. Gall midges (Diptera, Cecidomyiidae) of Hungary. Annls hist.-nat. Mus. natn. Hung, 91.

- Lienhard, Ch. Beitrag zur Kenntnis der Psocopteren-Fauna Ungarns (Insecta). Ann. Hist.-Nat. Mus. Natl. Hung, 78.

- Fazekas, I. Dr. Kuthy Béla entomológiai gyűjteménye II. Microlepidoptera (Lepidoptera). Nat. Som. [CrossRef]

- Jenser, G. Behurcolt kártevő Thysanoptera fajok. (Introduced Thysanoptera pests). Növényvédelem.

- László, M.; Katona, G. P.; Péntek, L. A.; Nagy, A. V. Spread of the invasive Giant Asian Mantis Hierodula tenuidentata Saussure, 1869 (Mantodea, Mantidae) in Europe with new Hungarian data. Bonn zool. Bull. 2023, 72(1), 133–144. [Google Scholar]

- Teodorescu, I. Contribution to Database of Alien/Invasive Homoptera Insects in Romania. Rom. J.. Biol. Zool.

- Kóbor, P. Magyarország invaziv cimerespoloskái (Heteroptera, Pentatomidae). (Invasive stink bugs of Hungary (Heteroptera, Pentatomidae)). Növényvédelem.

- Jelinek, J.; Audisio, P.; Hajek, J.; Baviera, C. .; Moncourtier, B.; Barnouin, Th. Epuraea imperialis (Reitter, 1877). New invasive species of (Coleoptera) in Europe, with a checklist of sap beetles introduced to Europe and Mediterranean areas. Atti. Accad. Pelorit. Pericol. Cl. Sci. Fis. Mat. Nat, (2.

- Szinetár, Cs.; Kenyeres, Z. Introducing of Ameles spallanzania (Rossi, 1792) (Insecta, Mantodea) to Hungary raising questions of fauna-changes. Nat. Som. 2020, 35, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitzui, E.; Dobrin, I.; Dumbrava, M.; Gutue, M. The Range Expansion of Ovalisia festiva (Linnaeus, 1767) (Coleoptera, Buprestidae) in Eastern Europe and Its Damaging Potential for Cupressaceae. Trav. du Mus. Nat. Hist. Grigore Antipa, 58. [CrossRef]

- Merkl, O.; Hegyessy, G. Negyvenkét bogárcsalád adatai a sátoraljaújhelyi PIM – Kazinczy Ferenc Múzeum gyűjteményéből (Coleoptera, Polyphaga, Bostrichiformia, Cucujiformia, Elateriformia, Staphyliniformia). (Data on forty-two beetle families from the collection of the PIM – Kazinczy Ferenc Museum at Sátoraljaújhely) Folia hist. Nat. Mus. Matraensis 2022, 46, 45–134.

- Vas, Z.; Rékási, J. , Rózsa, L. A checklist of lice of Hungary (Insecta, Phthiraptera). Ann. Hist.-Nat. Mus. Nat. Hung.

- Adam, C.; Constantinescu, I.C.; Drăghici A., C.; Fusu M., M.; Gheoca, V.; Iancu, L.; Iorgu I., Ș.; Irimia A., G.; Maican, S.; Manu, M.; Petrescu A., M.; Popa A., F.; Rădac I., A.; Ruști D., M.; Sahlean C., T.; Szekely, L.; Șerban, C.; Tăușan, I. Lista preliminară a speciilor alogene invazive și potențial invazive de nevertebrate terestre din România (Preliminary list of invasive and potentially invasive alien species of terrestrial invertebrates in Romania). Ministerul Mediului, Apelor şi Pădurilor & Universitatea din Bucureşti.Bucureşti, Romania, 2020; pp. 1-40.

- Bednár, F.; Hemala, V.; Čejka, T. First records of two new silverfish species (Ctenolepisma longicaudatum and Ctenolepisma calvum) in Slovakia, with checklist and identification key of Slovak Zygentoma. Biologia. [CrossRef]

- Papp, L.; Pecsenye, K. Drosophilidae (Diptera) of Hungary. Acta Biol. Debrecina, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, Ch. J.; Ehrmann, R. Invasive Mantodea species in Europe. Articulata 2018, 33, 73–90. [Google Scholar]

- Tóth, J. A fajspektrum változásának lehetséges okai. Behurcolt új erdészeti kártevõk Magyarországon. ( Possible causes of the change in the species spectrum. New introduced forest pests in Hungary.) Mag, Kutatás, Termesztés, Kereskedelem 2001, 6, 9-17.

- Kontschán, J.; Kiss, E.; Ripka, G. Új adatok a hazai levélbolhák (Insecta, Psylloidea) előfordulásaihoz III. (New Data to Occurrences of the Hungarian Jumping Plant Lice (Insecta, Psylloidea) III.). Növényvédelem.

- Kontschán, J.; Ripka, G. Új adatok a hazai levélbolhák (Insecta, Psylloidea) előfordulásaihoz II.(New Data to Occurrences of the Hungarian Jumping Plant Lice (Insecta, Psylloidea) II.). Növényvédelem.

- CABI, Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International, Exotic Insect Biocontrol Agents Released in Europe. Available online: https://cabidigitallibrary.org by 80.98.245.128 (accessed on 16.10. 2024).

- Szeőke, K.; Csóka, Gy. Jövevény kártevő ízeltlábúak Magyarországon – Lepkék (Lepidoptera). (An overview of the alien arthropods in Hungary Lepidoptera). Növényvédelem.

- Merkl, O. New beetle species in the Hungarian fauna (Coleoptera). Folia ent. Hung. 2006, 67, 19–36. [Google Scholar]

- Kinál, F.; Puskás, G. Occurrence of Ectobius vittiventris (Costa, 1847) (Blattellidae, Ectobiinae) in Hungary. Állattani Közlemények. [CrossRef]

- Vas, Z.; Kőszegi, K.; Takács, A. First record of the Nearctic blue mud-dauber wasp Chalybion californicum (de Saussure, 1867) from Hungary (Hymenoptera, Sphecidae). Folia ent. Hung. 2024, 85, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OEPP/EPPO, PM 6/3 (5) Biological control agents safely used in the EPPO region. OEPP/EPPO, Luxembourg, 2021; pp.

- Schlitt, B. P.; Lajtár, L.; Orosz, A. New grape-feeding leafhoppers in Hungary – first records of Erasmoneura vulnerata (Fitch, 1851) and Arboridia kakogawana (Matsumura, 1931) (Hemiptera, Clypeorrhyncha, Cicadellidae). Folia ent. Hung. 2024, 85, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondorosy, E. Adventív poloskafajok Magyarországon (Invasive alien bugs (Heteroptera) in Hungary). Növényvédelem.

- Kohútová, M; Obona, J. Príspevok k poznaniu inváznych druhov hmyzu z územia Slovenska. Contribution to the knowledge of invasive insect species from Slovakia. Folia Oec.

- Groot, M. An overview of alien Diptera in Slovenia. Acta ent. Slovenica 2013, 21(1), 5–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kontschán, J.; Bodnár, D.; Ripka, G. Új adatok a hazai levélbolhák (Insecta, Psylloidea) előfordulásaihoz III.(New Data to Occurrences of the Hungarian Jumping Plant Lice (Insecta, Psylloidea) III.). Növényvédelem.

- Kozár, F.; Benedicty, Zs.; Fetykó, K.; Kiss, B.; Szita, É. An annotated update of the scale insect checklist of Hungary (Hemiptera, Coccoidea). ZooKeys 2013, 309, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Józan, Z. Új kaparódarázs fajok (Hymenoptera, Sphecidae) Magyarország faunájában. New sphecid wasps (Hymenoptera, Sphecidae) in the fauna of Hungary. Somogyi Múzeumok Közleményei.

- Báldi, A.; Csányi, B.; Csorba, G.; Erős, T.; Hornung, E. , Merkl, O.; Orosz, A., Papp, L.; Szinetár, Cs., Varga, A.; Vas, Z.; Vétek, G. Ronkay, L.; Samu, F.; Soltész, Z.; Szép, T.; Vörös, J.; Zöldi, V.; Zsuga, K. Behurcolt és invazív állatok Magyarországon. (Introduced and invasive animals in Hungary). Magyar Tudomány.

- Radac, I. A. Expansion of some native or alien species of seed beetles and true bugs in Romania (Insecta, Coleoptera, Heteroptera). PhD. Thesis, Babeș-Bolyai University, Faculty of Biology and Geology, Kolozsvár, Romania, 2022; pp. 1–146. [Google Scholar]

- Kiss, A. A sáskajárások néhány területi és tájtörténeti vonatkozása a Kárpát-medencében. (Some territorial and landscape historical aspects of locust migrations in the Carpathian Basin). 9th Conference on landscape history, Keszthely, Hungary, 21. 06. 2012.

- Merkl, O. Hívatlan bogárvendégek Magyarországon. (Uninvited beetle guests in Hungary). Természettudományi Közlöny.

- Havasréti, B. A filoxérától a kígyóaknás szőlőmolyig. Few Words about the Phylloxera and the Grape Leaf Miner Moth. -Légkör, 2016, 61(4), 161-163.

- Zikic, V.; Stankovic, S.; Ilic, M.; Kavallieratos, N. G. Braconid parasitoids (Hymenoptera, Braconidae) on poplars and aspen (Populus spp.) in Serbia and Montenegro. North-West. J. Zool.

- Hári, K.; Fail, J.; Streito J., C.; Fetykó K., G.; Szita, É. , Haltrich A.; Vikár D.; Radácsi P.; Vétek G. First record of Aleuroclava aucubae (Hemiptera Aleyrodidae) in Hungary, with a checklist of whiteflies occurring in the country. Redia, 1926. [Google Scholar]

- Csősz, S.; Báthori, F.; Gallé, L.; Lőrinczi, G.; Maák, I.; Tartally, A.; Kovács, É.; Somogyi, A. Á.; Markó, B. The Myrmecofauna (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) of Hungary, Survey of Ant Species with an Annotated Synonymic Inventory. Insects 2021, 12, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tóth, J. Behurcolt és új erdészeti kártevők Magyarországon. (Introduced and new forest pests in Hungary). Erdészeti lapok.

- Csóka, Gy. Recent Invasions of Five Species of Leafmining Lepidoptera in Hungary. 31-36. In Proceedings, integrated management and dynamics of forest insects. Liebhold, A. M.; McManus, M. L.; Otvos, I. S.; Fosbroke, S. L. C. (Eds.); Publisher: Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northeastern Research Station, Madison, U. S. 167 pp. [CrossRef]

- Szőke, V. First records of two spongillafly species from Hungary (Neuroptera, Sisyridae). Folia ent. Hung. 2024, 85, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, D.; Korda, M.; Traser, Gy. Two species of Collembola new for the fauna of Hungary. Opusc. Zool. 2011, 42(2), 199–206. [Google Scholar]

- Szabóky, Cs. New data to the Microlepidoptera fauna of Hungary, part XX (Lepidoptera, Autostichidae, Batrachedridae, Elachistidae, Sesiidae, Tineidae, Tortricidae). Folia ent. Hung. 2023, 84, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeőke, K.; Avar, K. Athetis hospes (Freyer, 1831) Nyugat-Magyarországon (Lepidoptera, Noctuidae). (Athetis hospes (Freyer, 1831) in West-Hungary (Lepidoptera, Noctuidae). Nat. Som, 33. [CrossRef]

- Kóbor, P. Platycranus metriorrhynchus, A new Mediterranean plant bug in Hungary (Heteroptera, Cimicomorpha, Miridae, Orthotylinae). Acta Phytopathol. Entomol. Hung. 2023, 58(2), 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koczor, S.; Kiss, B.; Szita, É.; Fetykó, K. Two Leafhopper Species New o the Fauna of Hungary (Hemiptera, Cicadomorpha, Cicadellidae). Acta Phytopathol. Entomol. Hung. 2012, 47(1), 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balázs, K.; Rédey, D. Acrosternum heegeri Fieber, 1861 (Hemiptera, Heteroptera, Pentatomidae), another Mediterranean bug expanding to the north. Zootaxa 2017, 4347(2), 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katona, G.; Balázs, S.; Dombi, O.; Tóth, B. First record of Spodoptera littoralis in Hungary (Lepidoptera, Noctuidae). Folia ent. Hung. 2020, 81, 119–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, Z. First record of Geocoris pallidipennis from Hungary (Hemiptera, Geocoridae). Folia ent. Hung, 1711; 81. [Google Scholar]

- Móra, A.; Sebteoui, K. Trithemis arteriosa (Burmeister, 1839) (Odonata, Libellulidae) in Hungary, can aquarium trade speed up the area expansion of Mediterranean species? North-West. J. Zool. 2020, 16(2), 237–238. [Google Scholar]

- Torma, A. Three new and a rare true bug species in the Hungarian fauna (Heteroptera, Dipsocoridae, Reduviidae, Lygaeidae). 2005, Folia ent. Hung. 66, 35-38.

- Takács, A.; Kőszegi, K. New records of Coleophoridae and Crambidae from Hungary (Lepidoptera). Folia ent. Hung. 2024, 85, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiam, J.; Németh, T. An uninvited guest, the fifth species of silverfish in Hungary (Zygentoma, Lepismatidae). Folia ent. Hung. 2024, 85, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ketelaere, A.; Magyar, B. First report of Ecclitura primoris Kokujev, 1902 in Hungary (Hymenoptera, Braconidae). Folia ent. Hung. 2024, 85, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlitt B., P.; Székely, Á.; Orosz, A. First records of Ziczacella heptapotamica (Kusnezov, 1928) and Asymmetrasca decedens (Paoli, 1932) from Hungary (Hemiptera, Clypeorrhyncha, Cicadellidae). Folia ent. Hung. 2024, 85, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukátsi, M.; Horváth, D. Natural enemy of Ambrosia artemisiifolia L. is spreading in Central Europe, first records of the ragweed leaf beetle (Ophraella communa LeSage, 1986) from Austria and Slovakia (Coleoptera, Chrysomelidae). Folia ent. Hung, 85. [CrossRef]

- Tóth, B.; Dombi, O.; Takács, A. Coleophora texanella Chambers, 1878, a new alien species in Hungary (Lepidoptera, Coleophoridae). Folia ent. Hung. 2024, 85, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, B.; Balogh, B. Occurrence of Grammodes bifasciata (Petagna, 1786) in Hungary (Lepidoptera, Erebidae). Folia ent. Hung. 2024, 85, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balogh, B.; Tóth, B. First occurrence of Hypena lividalis (Hübner, 1796) in Hungary (Lepidoptera, Erebidae). Folia ent. Hung. 2024, 85, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlitt B., P.; Horváth, Á.; Orosz, A. A Mediterranean gatecrasher, Neoaliturus inscriptus (Haupt, 1927) new to the Carpathian Basin (Hemiptera, Auchenorrhyncha, Cicadellidae). Folia ent. Hung. 2024, 85, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertelsmeier, C.; Bonnamour, A.; Brockerhoff, E. G.; Pyšek, P.; Skuhrovec, J.; Richardson, D. M.; Liebhold, A. M. Global proliferation of nonnative plants is a major driver of insect invasions. BioScience 2024, 74(11), 770–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csóka, Gy. A gyapottok bagolylepke (Helicoverpa armigera) terjedése Magyarországon. (The spread of the cotton bollworm (Helicoverpa armigera) in Hungary). In, Magyarország környezeti állapota 2015. Riesz, L. (Ed.); Publisher: Hermannn Ottó Nonprofit Intézet, Budapest, Hungary, 2016; pp. 62–64. [Google Scholar]

- Csóka, Gy.; Hirka, A.; Szőcs, L. Rovarglobalizáció a magyar erdőkben. (Insect globalization in Hungarian forests). Erdészettudományi Közlemények.

- Csóka, Gy.; Stone, G. N.; Melika, G. Non-native gall-inducing insects on forest trees, a global review. Biological Invasions 2017, 19, 3161–3181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriston, É.; Bozsó, M.; Krizbai, L.; Csóka, Gy. és Melika, G. Klasszikus biológiai védekezés Magyarországon a szelídgesztenye gubacsdarázs, Dryocosmus kuriphilus (Yasumatsu, 1951) ellen, előzetes eredmények. (Classical biological control against the chestnut gall wasp, Dryocosmus kuriphilus (Yasumatsu, 1951), preliminary results). Növényvédelem.

- Duhay, G. Behurcolt bogárfajok Magyarországon. (Introduced beetles in Hungary). In Tények könyve 1998 A.Kereszty Ed.; Publisher: Greger-Delacroix Kiadó, Budapest, Hungary, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- García-Morales, M.; Denno, B. D.; Miller, D. R.; Miller, G,L.; Ben-Dov, Y.; Hardy, N. B. ScaleNet, A literature-based model of scale insect biology and systematics. Database. 2016. Available online: http://scalenet.info (accessed on day month year). [CrossRef]

- Ellis, W. N. Plant parasites of Europe, leafminers, galls and fungi. Available online: https://bladmineerders.nl (accessed on day month year).

- Bourgoin, Th. FLOW (Fulgoromorpha Lists on The Web), a world knowledge base dedicated to Fulgoromorpha. Version 8, Available online:. Available online: http://www.hemiptera-databases.org/flow (accessed on day month year).

- Blackman, R.; Eastop, V. Blackman & Eastop's Aphids on the World's Plants. Available online: https://aphidsonworldsplants.info/ (accessed on day month year).

- Szénási, V. Two new weevil species in Hungary (Coleoptera, Curculionidae, Entiminae). Folia ent. Hung. 2016, 77, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission: Joint Research Centre. European Alien Species Information Network (EASIN) Available online:. Available online: https://easin.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ (accessed on day month year).

- Sáfián, Sz.; Katona, G.; Tóth, B. First report of the palm borer moth, Paysandisia archon (Burmeister, 1879), in Hungary (Lepidoptera, Castniidae). Folia ent. Hung. 2023, 84, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson-Delmotte, V.; Zhai, P.; Pirani, A. ; Connors, S.L. et al. IPCC, 2021: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Publisher: Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1-2391. [CrossRef]

- Ditlevsen, P.; Ditlevsen, S. Warning of a forthcoming collapse of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation. Nature, Nat. Com, 4254; 14. [Google Scholar]

- Gagosian, R. B. Abrupt climate change. Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. World Economic Forum, Davos, Switzerland, , 2003, Retrieved from https://www.whoi. 27 January.

- Ziska, L. H.; Blumenthal, D. M.; Runion, G. B.; Raymond Hunt, R. E. Diaz-Soltero, H. Invasive species and climate change, an agronomic perspective. Climatic Change, 1007. [Google Scholar]

- iNaturalist Available online:. Available online: https://www.inaturalist.org/places/romania (accessed on 27.11. 2024).

- Calmasur, Ö. New records and some new distribution data for the Turkish Nematinae (Hymenoptera: Symphyta: Tenthredinidae) fauna. Türk. entomol. Derg, 4: 44 (3). [CrossRef]

- Strumia F, Yildirim E (2007). Contribution to the knowledge of Chrysididae fauna of Turkey (Hymenoptera, Aculeata). Frust. Ent, 30.

- John Ascher, John Pickering: World Bee Diversity Interactive checklists of world bees by country. Available online: https://www.discoverlife.org/nh/cl/counts/Apoidea_species.html (accessed on 07. 11. 2024).

- Juho Paukkunen Sawflies, wasps, ants and bees – Hymenoptera https://laji.fi/en/taxon/MX.43122 (accessed on 03.08.2024). (accessed on 03.08.2024).

- Yildirim, E. The distribution and biogeography of Pompilidae in Turkey (Hymenoptera: Aculeata). Entomologie faunistique. Faun. Ent. 2011, 63(1), 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Yildirim, E.; Özbek, H. An Evaluation on The Fauna of Vespoidea (Hymenoptera, Aculeata) of Turkey, Along with New Records and New Localities for Some Species. Turk. J. Zool. 1999, 23(6), 591–604. [Google Scholar]

- Haris, A.; Vidlička, L.; Majzlan, O.; Roller, L. Effectiveness of Malaise trap and sweep net sampling in sawfly research (Hymenoptera: Symphyta). Biologia 2024, 79, 1705–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balázs, A.; Haris, A. Sawflies (Hymenoptera: Symphyta) of Cerová vrchovina Upland (South Slovakia). Nat. Som, 6: 33. [CrossRef]

- Szabó, S.; Árnyas, E.; Varga, Z. Long-term light trap study on the macro-moth (Lepidoptera: Macroheterocera) fauna of the Aggtelek National Park. Acta zool. Acad. Sci. Hung. 2007, 53(3), 257–269. [Google Scholar]

- Varga, J.; Korompai, T.; Horokán, K.; Hirka, A.; Gáspár, C.; Kozma, P.; Csóka, G.; Csuzdi, C. Analysis of the Macrolepidoptera fauna in Répáshuta based on the catches of a light-trap between 2014–2019. Acta Univ. Esterházy Sect. Biol, 47.

- Szentkirályi, F.; Leskó, K.; Kádár, F. Hosszú távú rovarmonitorozás a várgesztesi erdészeti fénycsapdával. 2. A nagylepke együttes diverzitási mintázatának változásai. (Long-term insect monitoring with forestry light trap of Várgesztes. 2. Changes of pattern of species diversity of Macrolepidopteran assemblages). Erdészeti Kutatások, 91.

- Szentkirályi, F.; Leskó, K.; Kádár, F. Climatic effects on long-term fluctuations in species richness and abundance level of forest macrolepidopteran assesmblages in a Hungarian mountainous region. Carpth. J. Earth Environ. Sci. 2007, 2, 73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Biella, P. ; Cornalba,M.; Rasmont, P., Neumayer, J., Mei, M., Eds.; Brambilla, M. Climate tracking by mountain bumblebees across a century: Distribution retreats, small refugia and elevational shifts. Global Ecol. Cons. 2023, 54, 03163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manino, A.; Patetta, A.; Porporato, M.; Quaranta, M.; Intoppa, F.; Piazza, M. G.; Frilli, F. Bumblebee (Bombus Latreille, 1802) distribution in high mountains and global warming. Redia 2007, 90, 90,125–129. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr, J.T.; Pindar, A.; Galpern, P.; Packer, L.; et al. Climate change impacts on bumblebees converge across continents. Science, 6244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulson, D.; Lye, G. C.; Darvill, B. Decline and conservation of bumble bees. Ann. Rev. Ent. 2008, 53, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnóczkyné Jakab, D.; Tóth, M.; Szarukán, I.; Szanyi, S.; Józan, Z.; Sárospataki, M.; Nagy, A. Long-term changes in the composition and distribution of the Hungarian bumble bee fauna (Hymenoptera, Apidae, Bombus). J. Hym. Res, 2: 96. [CrossRef]

- Ban-Calefariu, C.; Sárospataki, M. Contributions to the knowledge of Bombus and Psithyrus Genera (Apoidea: Apidae) in Romania. Trav. Mus. Nat. Hist. Grigore Antipa 2007, 50, 239–258. [Google Scholar]

- Šima, P.; Smetana, V. ; Current distribution of the bumble bee Bombus haematurus (Hymenoptera: Apidae, Bombini) in Slovakia. Klapalekiana 2009, 45, 209–212. [Google Scholar]

- Šima, P.; Smetana, V. Quo vadis Bombus haematurus? An outline of the ecology and biology of a species expanding in Slovakia. Act. Mus. Tek. 2018, 11, 41–65. [Google Scholar]

- Biella, P.; Ćetković, A.; Gogala, A.; Neumayer, J.; Sárospataki, M.; Šima, P.; Smetana, V. Northwestward range expansion of the bumblebee Bombus haematurus into Central Europe is associated with warmer winters and niche conservatism. Insect Sci. 2021, 28, 861–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manole, T. Biodiversity of insect populations from Apoidea superfamily in agricultural ecosystems. Rom. J. Plant Prot. 2014, 7, 111–128. [Google Scholar]

- Czyżewski, S.; Kierat, J.; Zapotoczny, K. First record of Bombus haematurus Kriechbaumer, 1870 (Hymenoptera: Apidae) in Poland. Act. zool.a crac, 7: 67.

- Kosior, A.; Celary, W.; Olejniczak, P.; Fijał, J.; Kro´l, W.; Solarz, W.; Płonka, P. The decline of the bumble bees and cuckoo bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae: Bombini) of Western and Central Europe. Oryx. [CrossRef]

- Šima, P. & Smetana, V. Čmele (Hymenoptera: Bombini) Liptovskej kotliny a Tatranského podhoria. (Bumble bees (Hymenoptera: Bombini) at selected localities of the Liptovská kotlina basin and the Tatranské podhorie foothill). Nat. Tut.

- Šima, P. & Smetana, V. Bombus (Cullumanobombus) semenoviellus (Hymenoptera: Apidae: Bombini) new species for the bumble bee fauna of Slovakia. Klapalekiana.

- Rahimi, E.; Barghjelveh, S.; Dong, P. Estimating potential range shift of some wild bees in response to climate change scenarios in northwestern regions of Iran. J. Ecol Environ. 1: 2021, 45, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raider, R.; Reilly, J.; Bartomeus, I.; Winfree, R. Native bees buffer the negative impact of climate warming on honey bee pollination of watermelon crops. Global Change Biology 2013, 19, 3103–3110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchenne, E.; Thébault, E.; Michez, D.; Gérard, M.; Celine Devaux, C.; et al. Long-term effects of global change on occupancy and flight period of wild bees in Belgium. Global Change Biology 2020, 26(12), 6753–6766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okely, M.; Engel, M.S.; Shebl, M.A. Climate Change Influence on the Potential Distribution of Some Cavity-Nesting Bees (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae). Diversity 2023, 15, 1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tryjanowski, P.; Pawlikowski, T.; Pawlikowski, K.; Banaszak-Cibicka, W.; Sparks, T. H. Does climate influence phenological trends in social wasps (Hymenoptera: Vespinae) in Poland? Eur. J. Entomol, 2: 107.

- Pawlikowski, T.; Pawlikowski, K. Phenology of Social Wasps (Hymenoptera: Vespinae) in the Kujawy Region (Northern Poland) under the the influence of climatic changes 1981–2000. Bull. Geog. Ser. Phys. Geogr. 2009, 1, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verheyde, F.; Vertommen, W.; Rhebergen, F.; De Ketelaere, A.; Doggen, K. & van Loon, M. Notes on the population dynamics of Euodynerus dantici (Rossi, 1790) and first records of its associated parasitoid Chrysis sexdentata Christ, 1791 in the Low Countries. Bull. ann. Soc. r. belge entomolog.

- Hallmann, C. A.; Sorg, M.; Jongejans, E.; Siepel, H.; Hofland, N.; Schwan, H.; Stenmans, W.; Müller, A.; Sumser, H.; Hörren, T.; et al. More than 75 percent decline over 27 years in total flying insect biomass in protected areas. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laczó, F. Pesticide use, issues and how to promote sustainable agriculture in Hungary. PAN Germany & Center for Environmental Studies Foundation, CES.,Brussels, Belgium, 2004; pp. 1-4. Retrieved from https://www.pan-germany.org/download/fs_hu_eng.pdf (accessed on 15. 11. 2024). (accessed on 15. 11. 2024).

- Goulet, H.; Huber, J. T. Hymenoptera of the world: an identification guide to families. Canada Communication Group, Ottawa, Canada 1993; pp. 668.

- Benson, R. B. 1968: Hymenoptera from Turkey, Symphyta. Bull. Brit. Mus. Nat. Hist. Ser. Ent. 1968, 22(4), 111–207. [Google Scholar]

- Barbir, J.; Martín, L.O.; Lloveras, X.R. Impact of Climate Change on Sawfly (Suborder: Symphyta) Polinators in Andalusia Region, Spain. In Handbook of Climate Change and Biodiversity; Filho, W. L., Barbir, J., Preziosi, R., Eds.; Climate Change Management; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; 323p. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Martínez, G.; González-Gaona, E.; López-Martínez, V.; Espinosa-Zaragoza, S.; López-Baez, O.; Sanzón-Gómez, D.; Pérez-De la O, N.B. Climatic Suitability and Distribution Overlap of Sawflies (Hymenoptera: Diprionidae) and Threatened Populations of Pinaceae. Forests 2022, 13, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemer, N. Forest Pests Outbreaks and Climate Change. Second Thematic Workshop on Climate Change and Preparedness for Pandemic Situations, Beirut, Lebanon, 28. 09. 2021. Retrieved from https://civil-protection-knowledge-network.europa.eu/system/files/2022-08/Forest-Insects-and-Climate-Change-Sept-28.pdf (accessed on 21. 10. 2024). (accessed on 21. 10. 2024).

- Evenhuis, N.L.; Greathead, D. J. World Catalog of Bee Flies (Diptera: Bombyliidae). Backhuys Publishers, Leiden. The Netherlands, 1999; pp.

- Roberts, H.; El-Hawagry, M. S. A. New records of bee flies (Bombyliidae, Diptera) from the United Arab Emirates. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Contr. 2024, 34(29), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeates, D. K. The evolutionary pattern of host use in the Bombyliidae (Diptera): a diverse family of parasitoid flies. Biol J Linn Soc Lond. 1997, 60, 149–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, C. M. Complex long-term dynamics of pollinator abundance in undisturbed Mediterranean montane habitats over two decades. Ecological Monographs.

- Havkenberget, K.; Jaric, D.; Krcmar, S. Distribution of Tabanids (Diptera: Tabanidae) Along a Two-Sided Altitudinal Transect. Environ. Entomol. 2009, 38(6), 1600–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herczeg, T.; Száz, D.; Blahó, M.; Barta, A.; Gyurkovszky, M.; Farkas, R.; Horváth, G. The effect of weather variables on the flight activity of horseflies (Diptera: Tabanidae) in the continental climate of Hungary. Parasitol. Res, ,: 114, 1087. [Google Scholar]

- Dransfield, B.; Brightwell, B. InfluentialPoints.com Biology, images, analysis, design. https://influentialpoints.com/Gallery/Tabanus_bromius_band-eyed_brown_horsefly.htm (accessed on 23. 09. 2024). (accessed on 23. 09. 2024).

- Hallmann, C.A.; Ssymank, A.; Sorg, M.; de Kroon, H.; Jongejans, E. Insect biomass decline scaled to species diversity: General patterns derived from a hoverfly community. PNAS, 2021, 118(2). e2002554117. [CrossRef]

- Barendregt, A.; Zeegers, Th.; van Steenis, W.; Jongejans, E. Forest hoverfly community collapse: Abundance and species richness drop over four decades. Insect. Conserv. Divers. 2022, 15(5), 510–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatter, W.; Ebenhöhm, H.; Kimam, R.; Scherer, F. 50-jährige Unterschungen an migrierenden Schwebfliegen, Waffenfliegen und Schlupfwespen belegen extreme Rückgänge (Diptera: Syrphidae, Stratiomyidae; Hymenoptera: Ichneumonidae). Ent. Zeit. 2020, 130(3), 131–142. [Google Scholar]

- Reemer, M.; Smit, J. T.; Zeegers, Th.; Basisrapport voor de Rode Lijst Zweefvliegen. EIS Kenniscentrum Insecten. EIS 2024–03. Available online: https://www.eis-nederland.nl/rapporten (accessed on 19. 11. 2024).

- Zeegers, Th.; van Steenis, W.; Reemer, M.; Smit, J. T. Drastic acceleration of the extinction rate of hoverflies (Diptera: Syrphidae) in the Netherlands in recent decades, contrary to wild bees (Hymenoptera: Anthophila). J. van Syrphidae 2024, 3(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN SSC HSG/CPSG European Hoverflies: Moving from Assessment to Conservation Planning. A report to the European Commission by the IUCN SSC Conservation Planning Specialist Group (CPSG) and the IUCN SSC Hoverfly Specialist Group (HSG). Conservation Planning Specialist Group, Apple Valley, MN, USA. 2022, pp. 1-84.

- Zeegers, Th. Second addition to the checklist of Dutch tachinid flies (Diptera: Tachinidae). Nederl. Faun. Meded, 5: 34.

- Ziegler, J. Recent range extensions of tachinid flies (Diptera: Tachinidae, Phasiinae) in north-east Germany and a review of the overall distribution of five species. Stud. Dipt.

- Stireman, J. O.; Dyer, L. A.; Janzen, D. H.; et al. Climatic unpredictability and parasitism of caterpillars: Implications of global warming. PNAS Biol. Sci, 1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environmental Statistics and Reporting team, Department for Environment Food & Rural Affairs: Butterflies in the United Kingdom and in England: 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/butterflies-in-the-wider-countryside-uk (accessed on 19. 09. 2024).

- Panigaj, L.; Panigaj, M. Changes in lepidopteran assemblages in Temnosmrečinská dolina valley (the High Tatra Mts, Slovakia) over the last 55 years. Biologia 2008, 63(4), 582–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, R. J.; Markl, G.; Gottschalk, T. K. Aestivation as a response to climate change: the Great Banded Grayling Brintesia circe in Central Europe. Ecol. Ent. 2021, 46, 1342–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, C.; Fartmann, Th. Conservation of a strongly declining butterfy species depends on traditionally managed grasslands. J. Ins. Cons. [CrossRef]

- Hudák, T. A nappali lepkefauna vizsgálata Székesfehérváron (Lepidoptera: Rhopalocera). Investigation on the butterfly fauna of Székesfehérvár (Lepidoptera: Rhopalocera). Nat. Som, 31.

- Fox, R.; Dennis, E. B.; Purdy, K.; Middlebrook, I.; Roy, D. B.; Noble, D.; Bothham, M. S.; Bourn, N. A. D. The State of the UK's Butterflies 2022. Publisher: Butterfly Conservation, Wareham, UK, 2023; pp. 1-28. Retrieved from https://eidc.ac.uk/ (accessed on 22. 10. 2024). (accessed on 22. 10. 2024).

- Uhl, B.; Wölfing, M.; Bässler, C. Mediterranean moth diversity is sensitive to increasing temperatures and drought under climate change. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 14473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betzholtz, P.-E.; Forsman, A.; Franzén, M. Associations of 16-Year Population Dynamics in Range-Expanding Moths with Temperature and Years since Establishment. Insects 2023, 14, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, T. H.; Dennis, L. R. H.; Croxton, Ph. J.; Cade, M. Increased migration of Lepidoptera linked to climate change. Eur. J. Entomol. 2007, 104, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Közösen a Természetért Alapítvány (Together for the Nature Foundation):Ízeltlábúak (Arthropodes). Available online: https://www.izeltlabuak.hu/ (accessed on day month year).

- Uherkovich, Á. Long-term monitoring of biodiversity by the study of butterflies and larger moths (Lepidoptera) in Sellye region (South Hungary, co. Baranya) in the years 1967–2022. Nat. Som, 9.

- Hufnagel, L.; Sipkay, Cs. A klímaváltozás hatása ökológiai folyamatokra és közösségekre. (The impact of climate change on ecological processes and communities). Budapesti Corvinus University, Budapest, Hungary, 2012; pp.

- Fox, R.; Dennis, E. B.; Harrower, C. A.; Blumgart, D. ; Bell. J. R.; Cook, P.; Davis, A. M.; Evans-Hill, L. J.; Haynes, F.; Hill, D.; Isaac, N. J. B,; Parsons, M. S.; Pocock, M. J. O.; Prescott, T.; Randle, Z.; Shortall, C. R.; Tordoff, G. M.; Tuson, D.; Bourn, N. A. D. The State of Britain’s Larger Moths 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Solarz, W.; Najberek, K.; Tokarska-Guzik, B.; Pietrzyk-Kaszyńska, A. Climate change as a factor enhancing the invasiveness of alien species. Environ. Socio.-econ. Stud, 11. [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, A.P.; Ponti, L. Analysis of invasive insects: links to climate change. In Invasive Species and Global Climate Change, Ziska L. H., Dukes J.S., (Eds.); CABI Publishing, Wallingford, UK, 2014, pp. 45-61. DOI 10.1079/9781780641645. 0045. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature), Invasive Alien Species and Climate Change. Available online: https://iucn.org/resources/issues-brief/invasive-alien-species-and-climate-change (accessed on 12. 09. 2024).

- Petrosyan, V.; Osipov, F.; Feniova, I.; Dergunova, N.; Warshavsky, A.; Khlyap, L.; Dzialowski, A. The TOP100 most dangerous invasive alien species in Northern Eurasia: invasion trends and species distribution modelling. NeoBiota 2023, 82, 23–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Zhou, G.; Cheng, X.; Xu, R. Fast Economic Development Accelerates Biological Invasions in China. Fast Economic Development Accelerates Biological Invasions in China. PLoS ONE 2007, 2(11), e1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyšek, P.; Hulme, P. E.; Simberloff, E. et. al. Scientists’ warning on invasive alien species. Biol. Rev, 1511; 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambdon, P. W.; Pyšek, P.; Basnou, C.; Hejda, M.; et al. Alien flora of Europe: species diversity, temporal trends, geographical patterns and research needs. Preslia 2008, 80, 101–149. [Google Scholar]

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).