Submitted:

24 April 2024

Posted:

26 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

“The apple trees were coming into bloom but no bees droned among the blossoms, so there was no pollination and there would be no fruit. The roadsides, once so attractive, were now lined with browned and withered vegetation as though swept by fire. These, too, were silent, deserted by all living things. Even the streams were now lifeless.”(Rachel Carson: Silent Spring)

2. Materials and Methods

Data Selection

Changes in Methods and Their Statistical Balancing

Data processing

Sampling Sites

3. Results

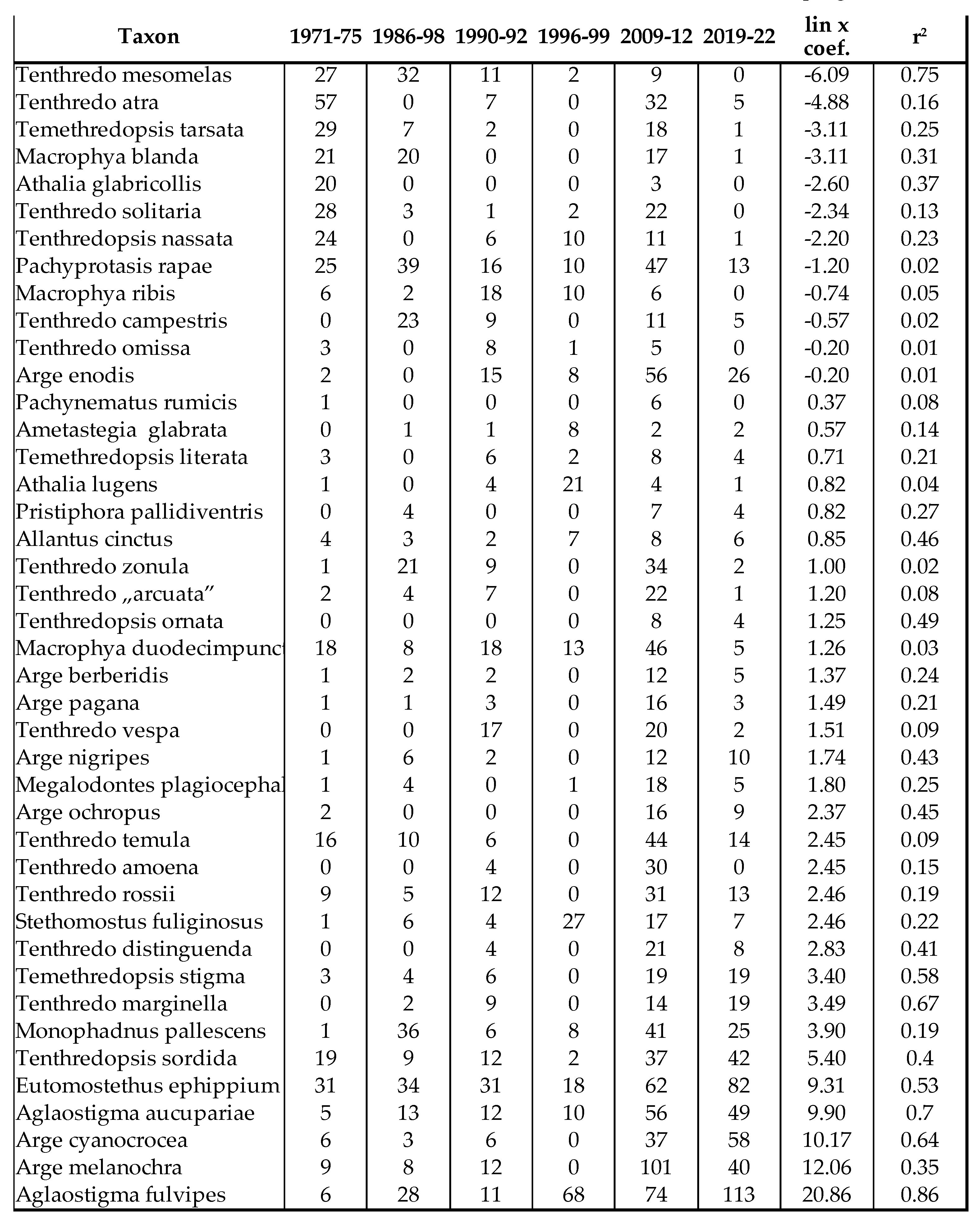

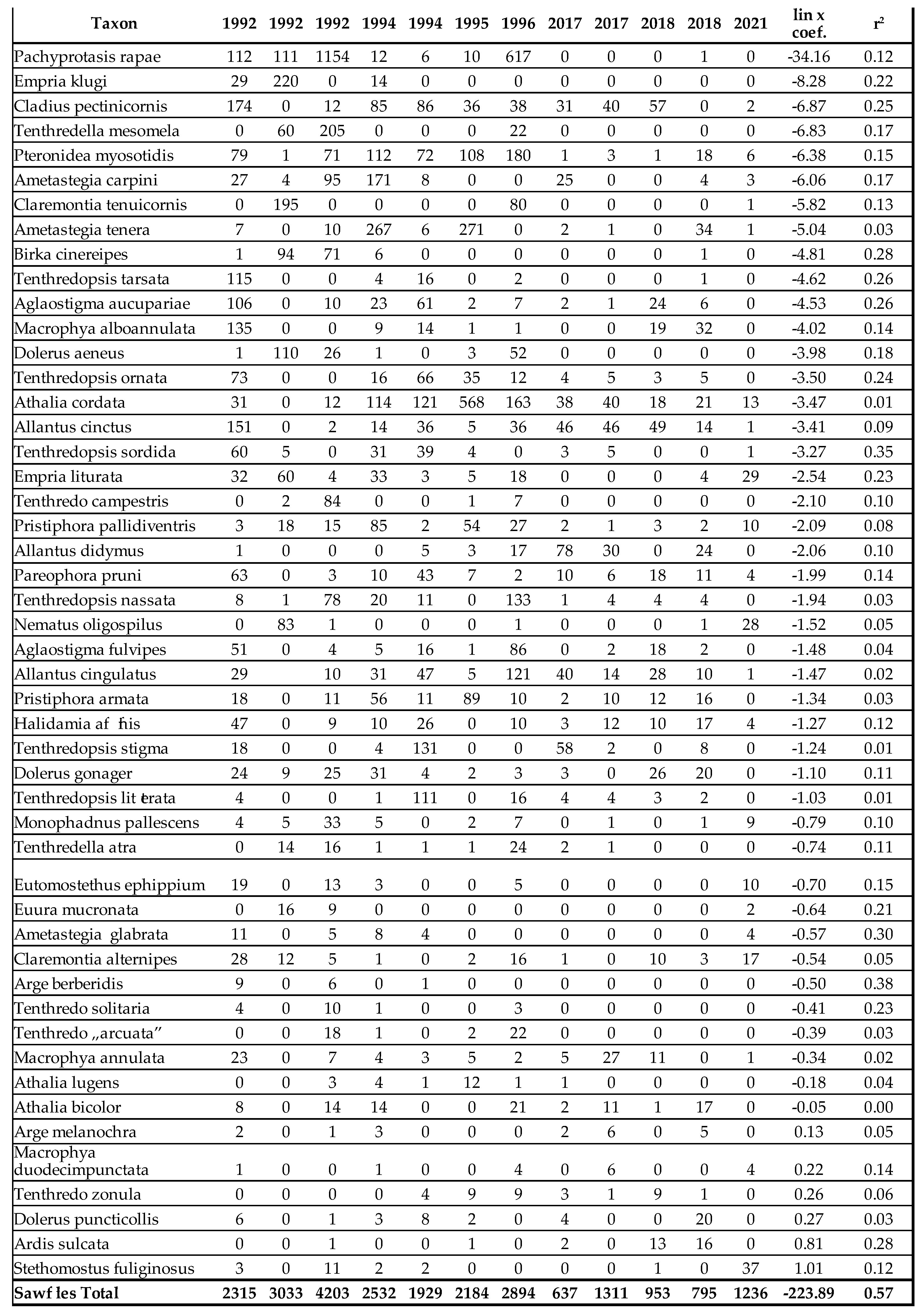

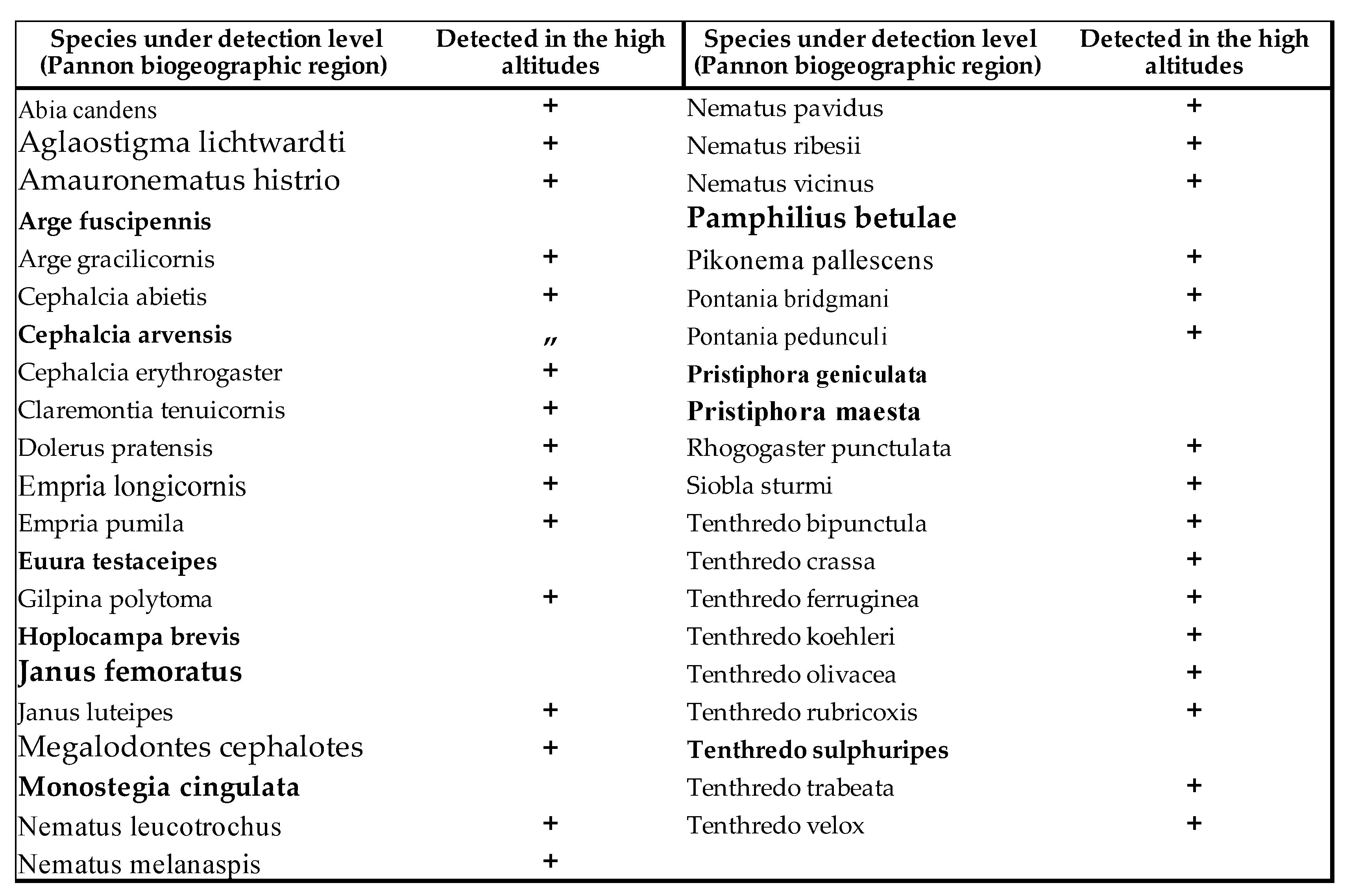

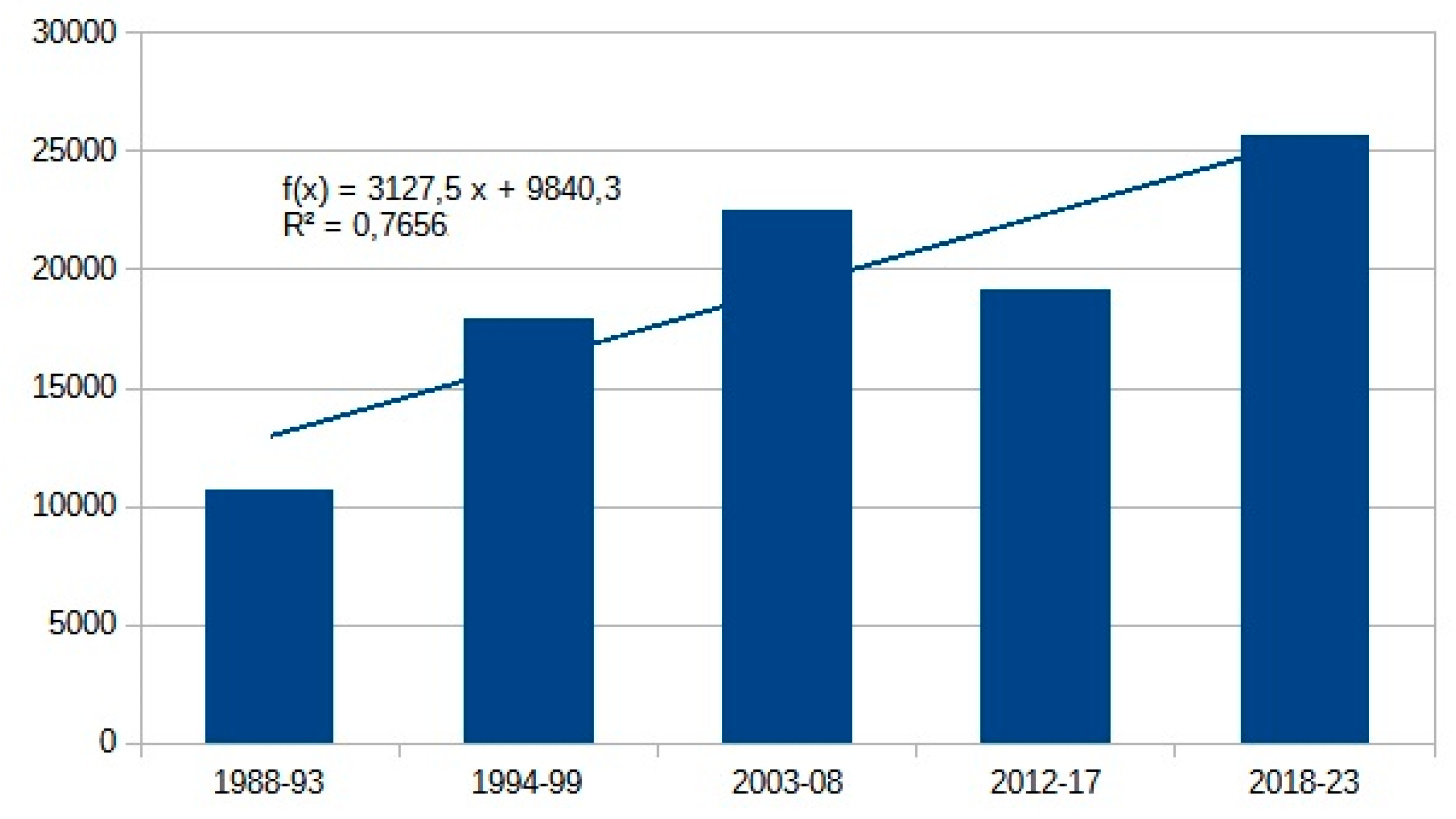

Symphyta

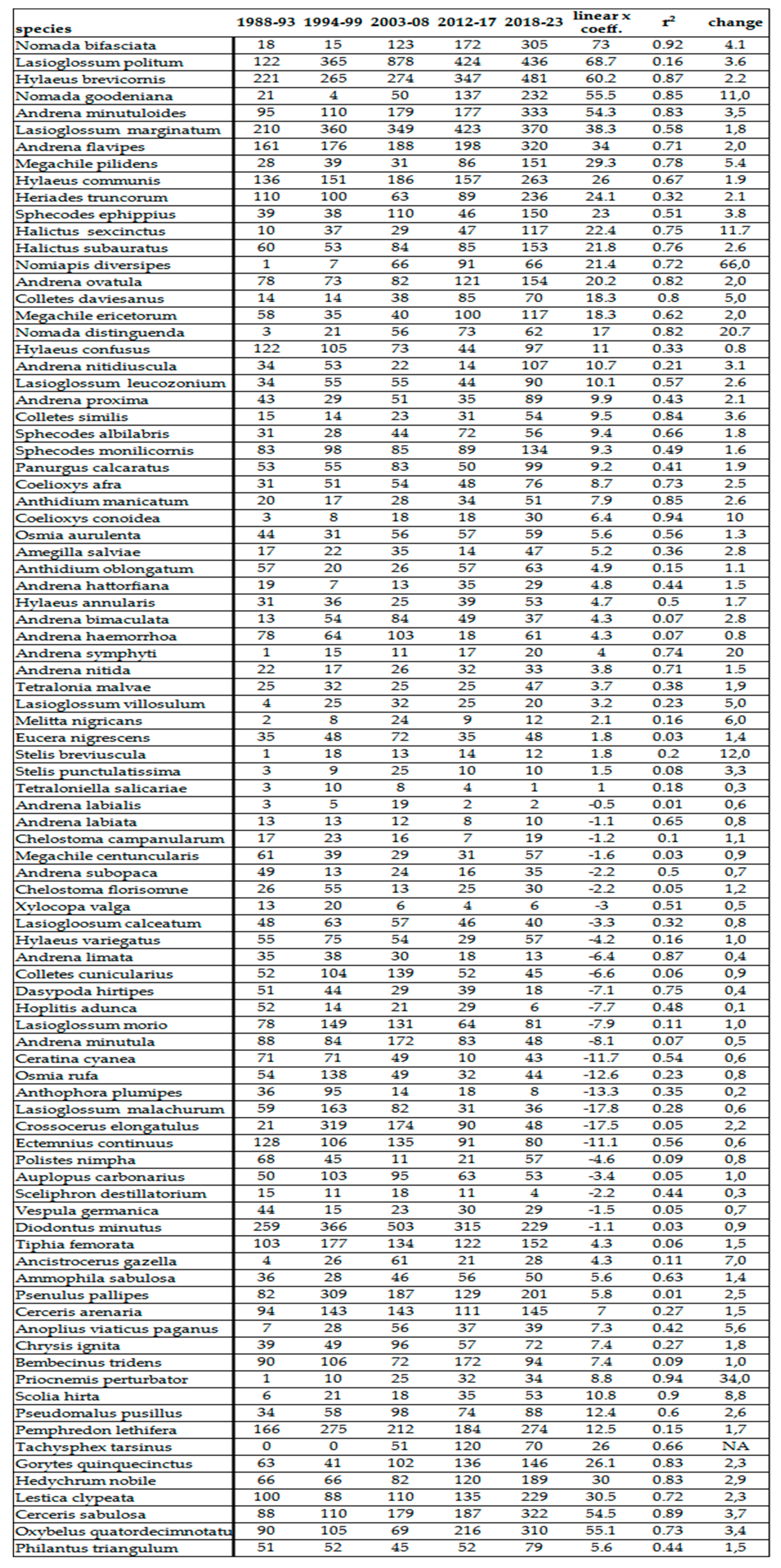

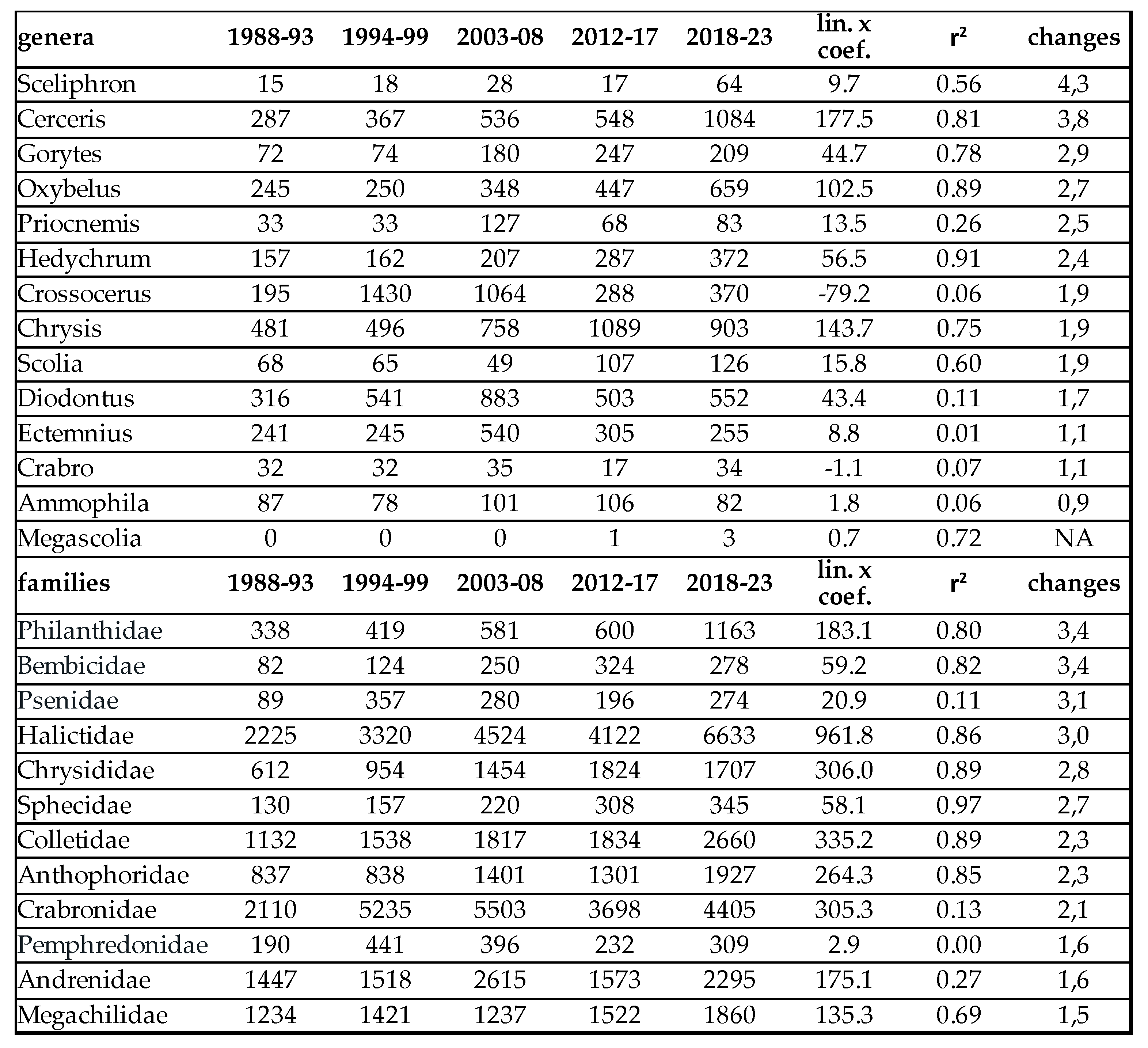

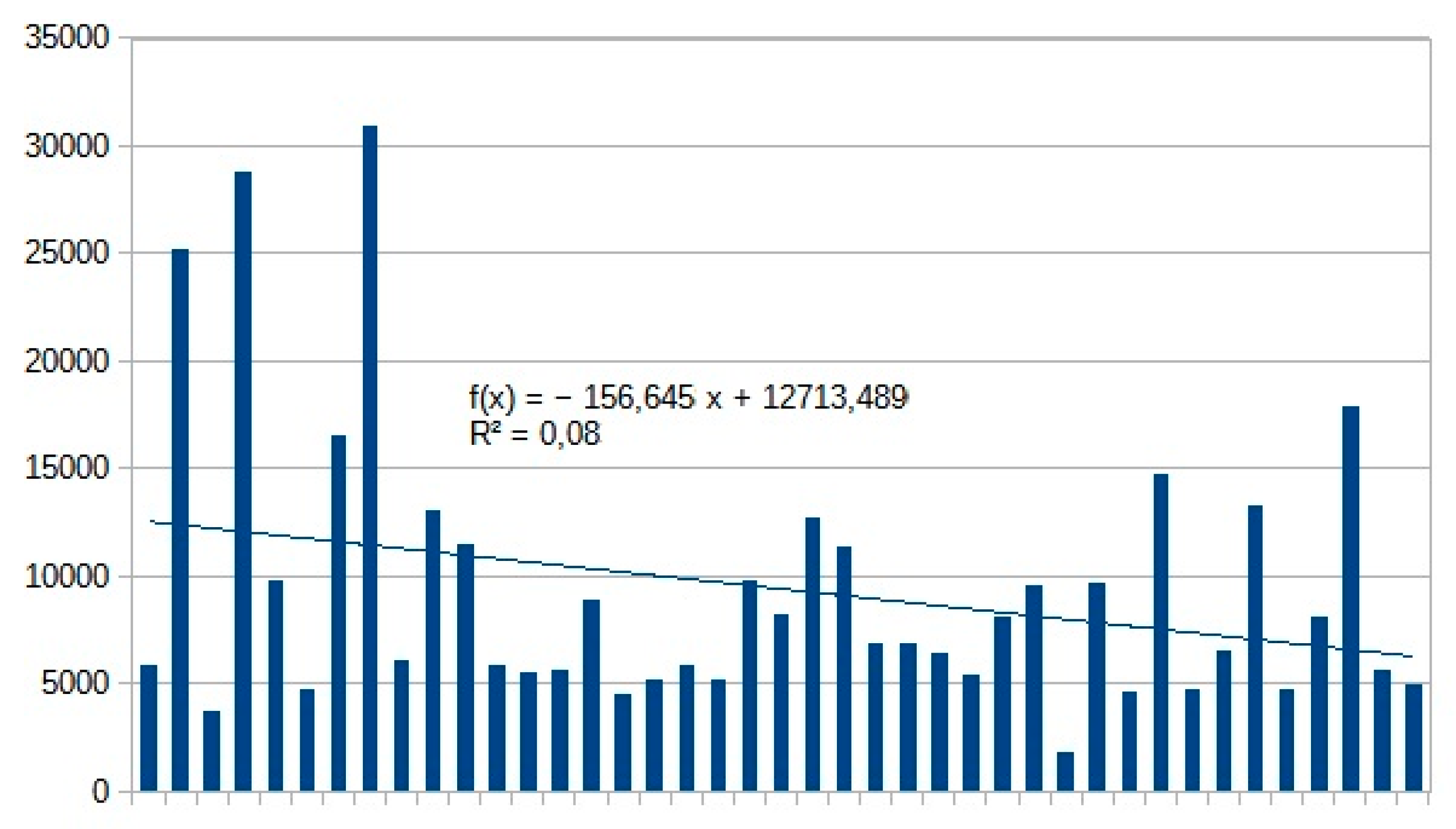

Aculeata

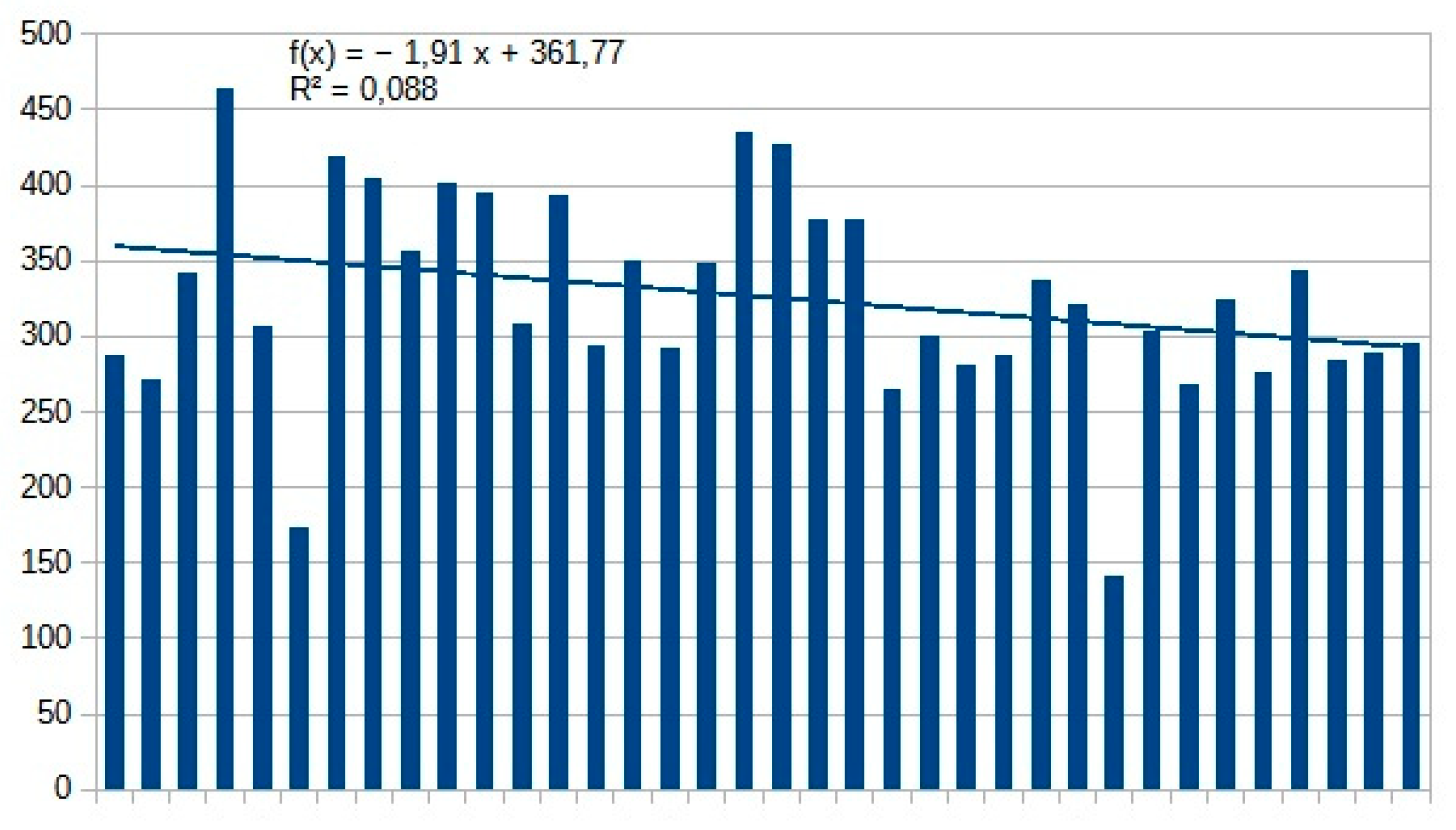

Bumblebees (Bombus spp.)

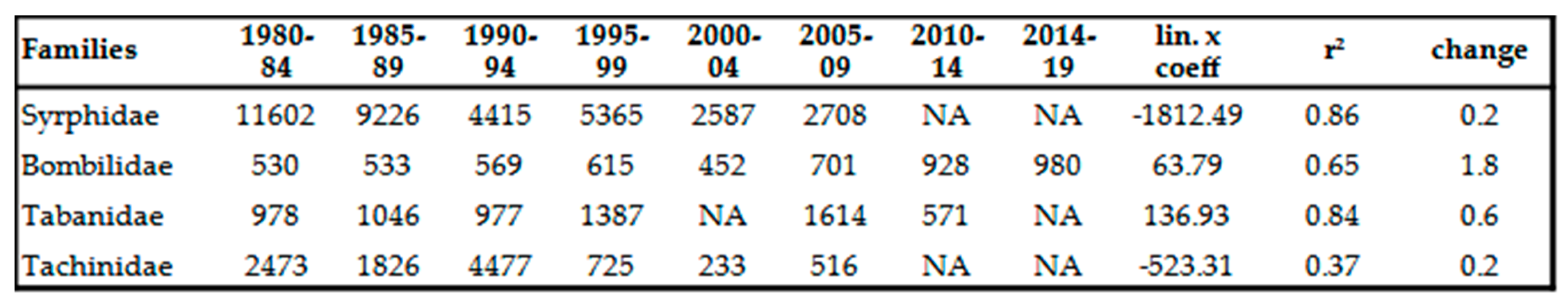

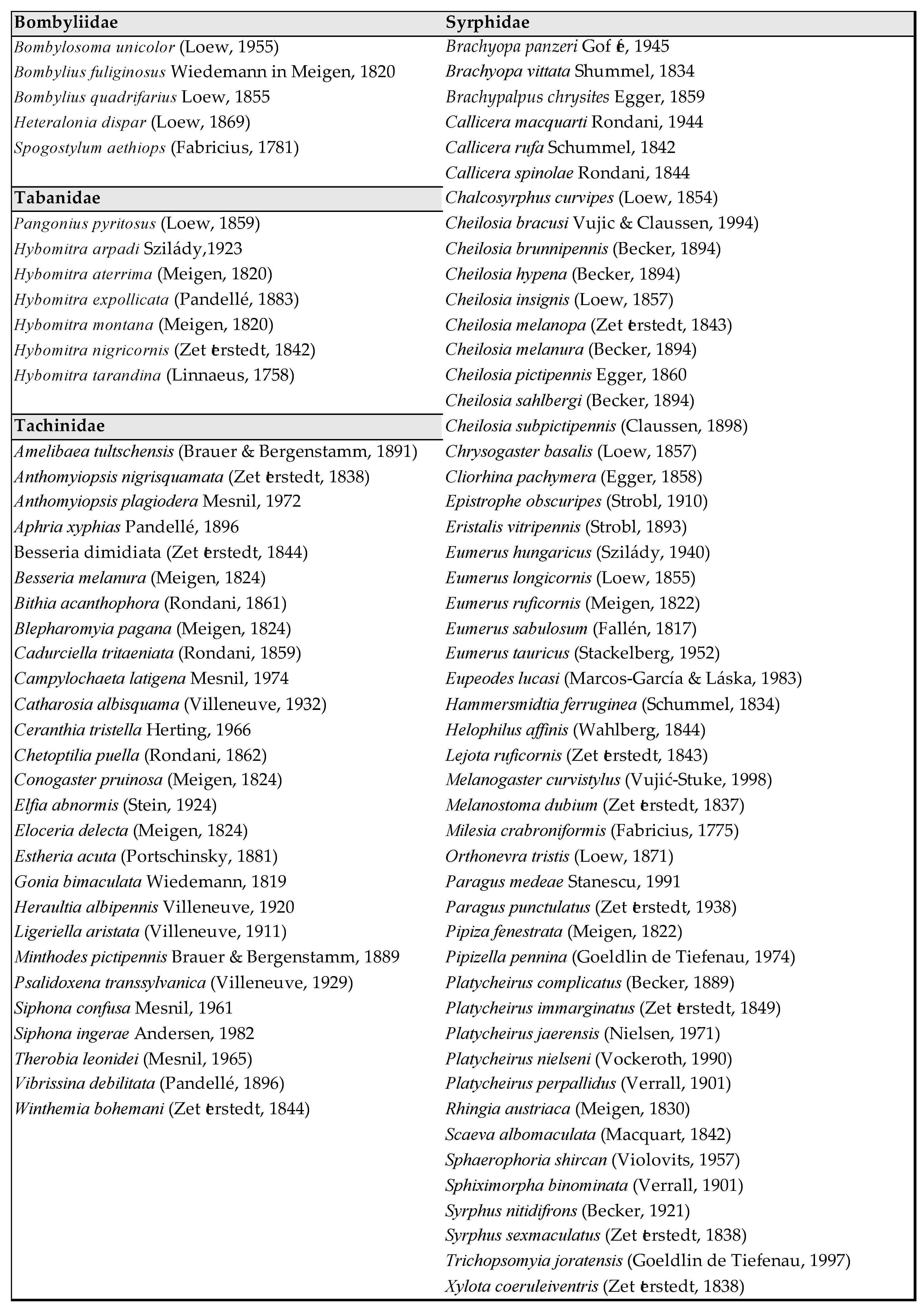

Diptera

Syrphidae (Hoverflies)

Tabanidae (Horse-flies)

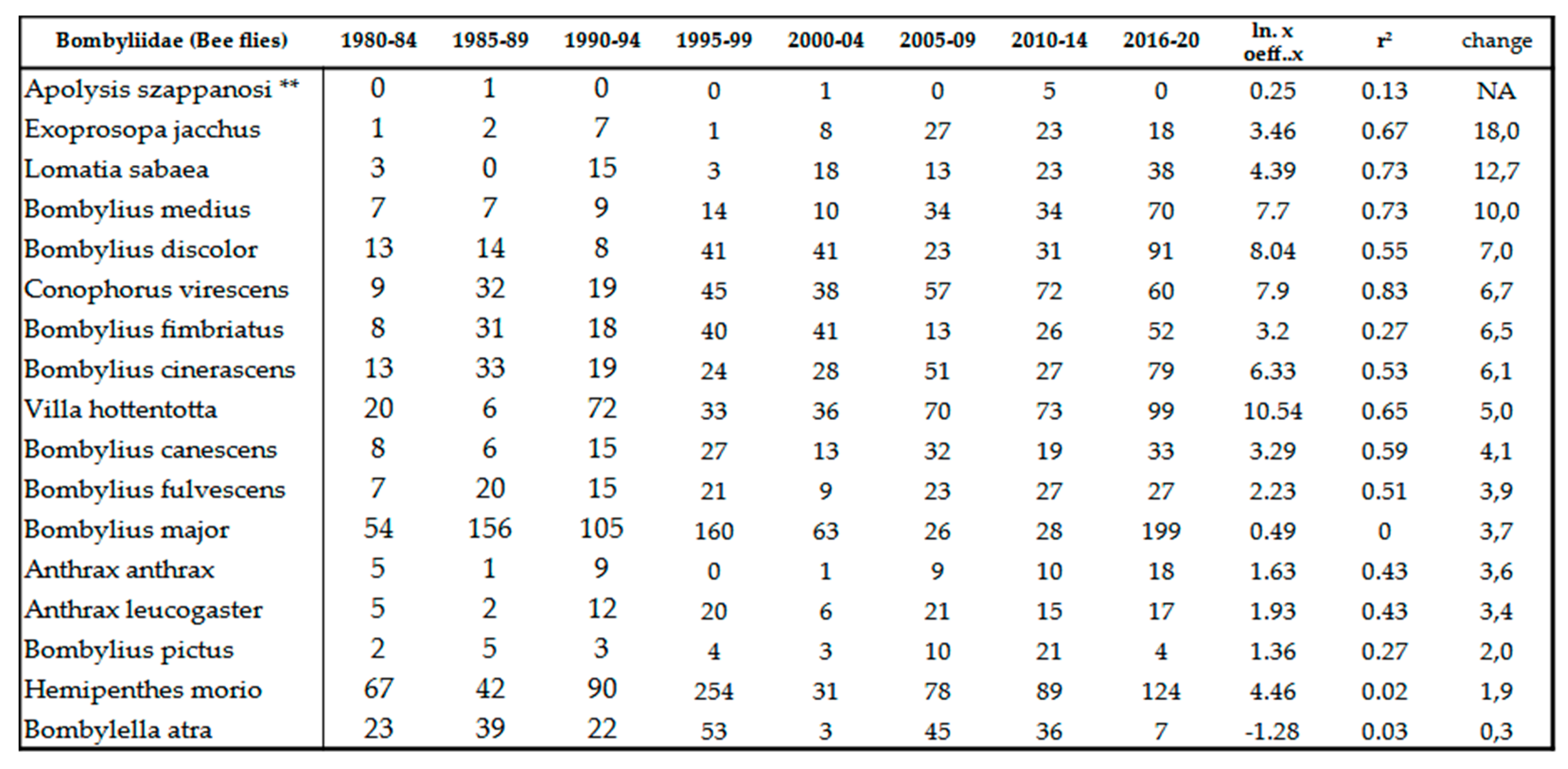

Bombyliidae (Bee Flies)

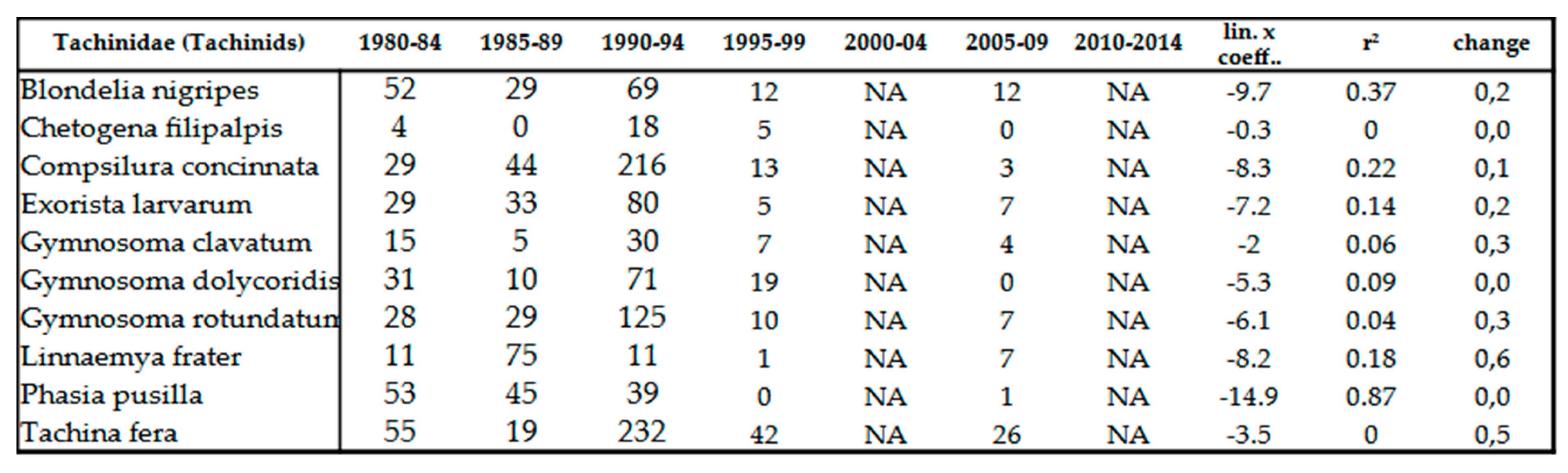

Tachinidae (Tachinids)

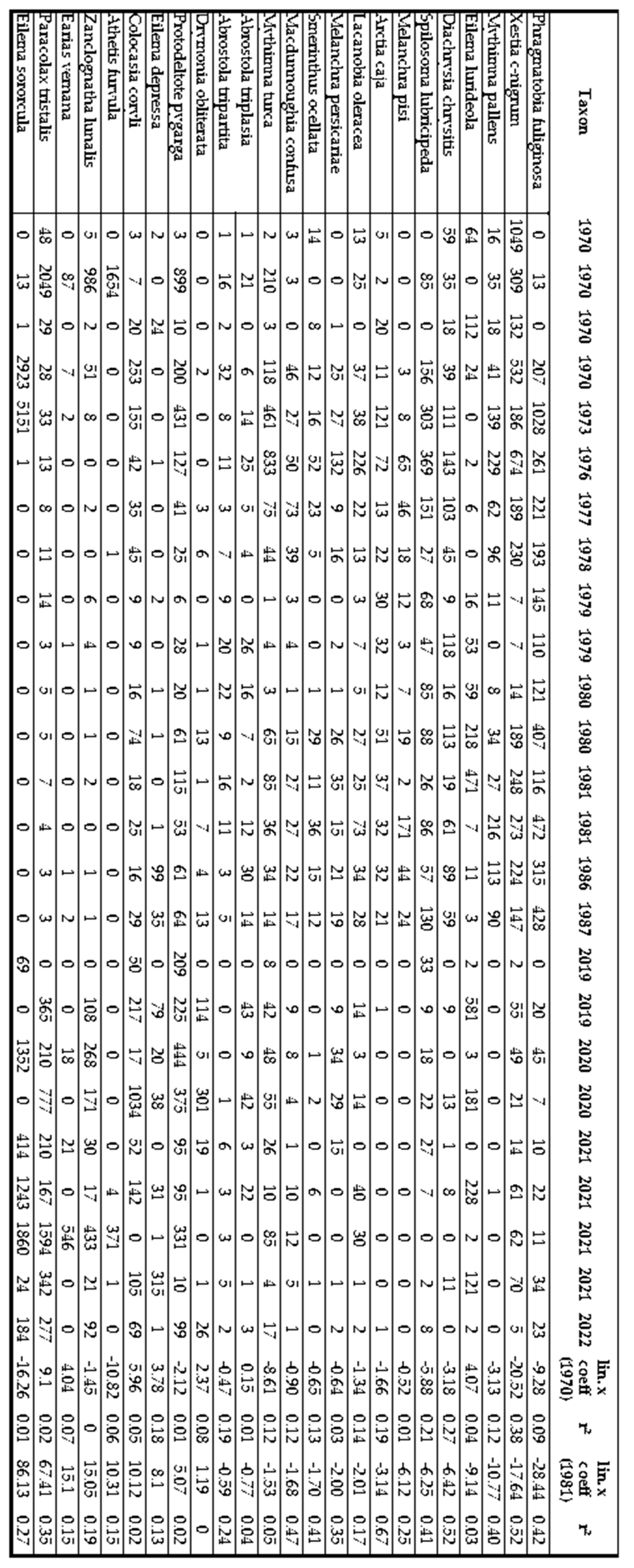

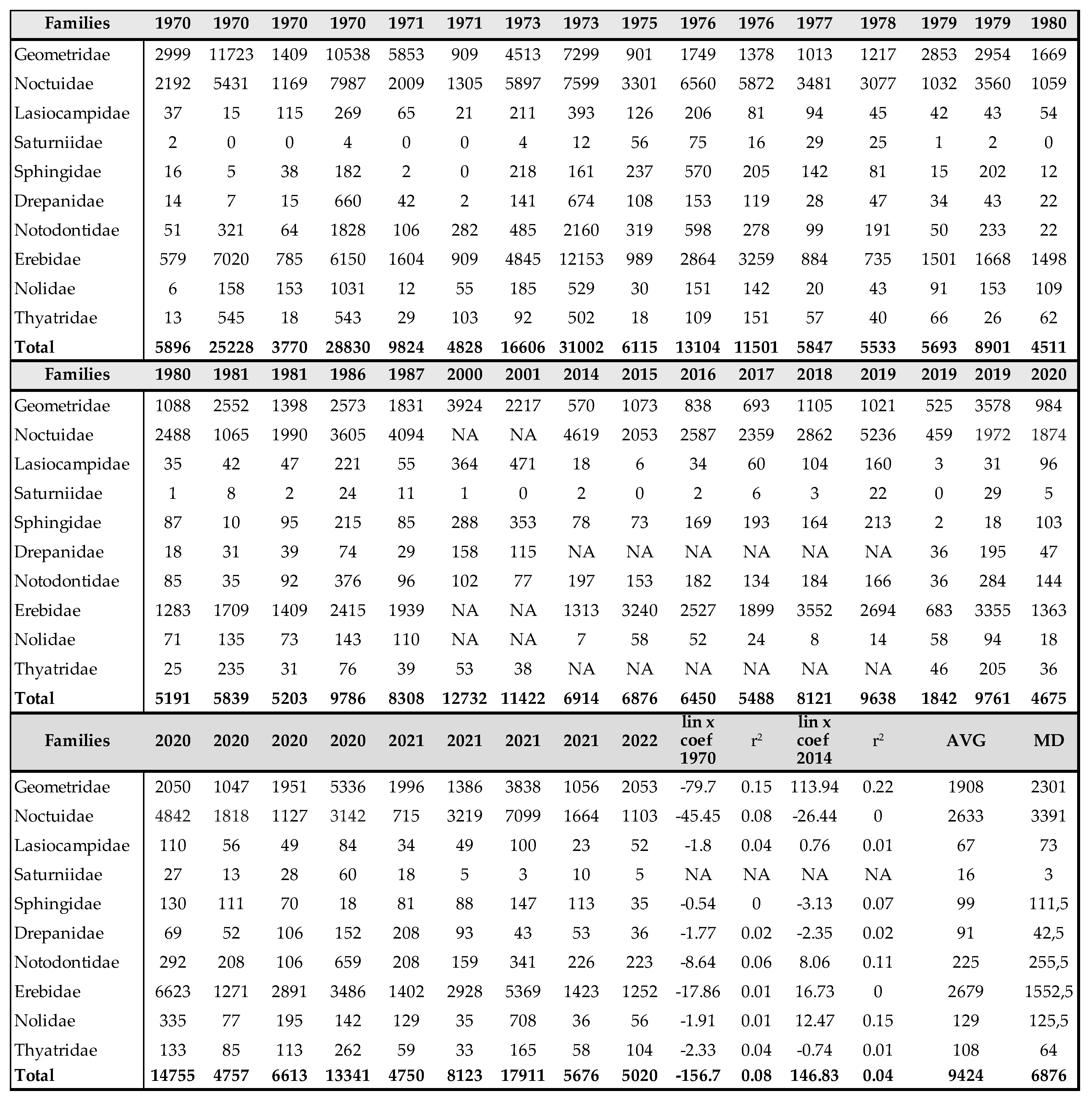

Lepidoptera

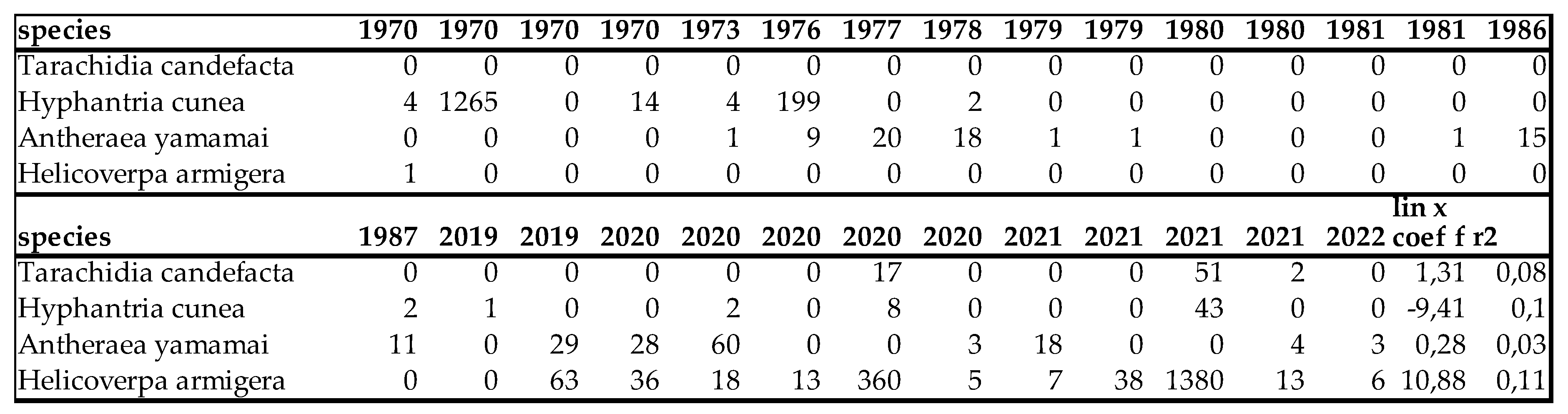

Nocturnal macrolepidoptera

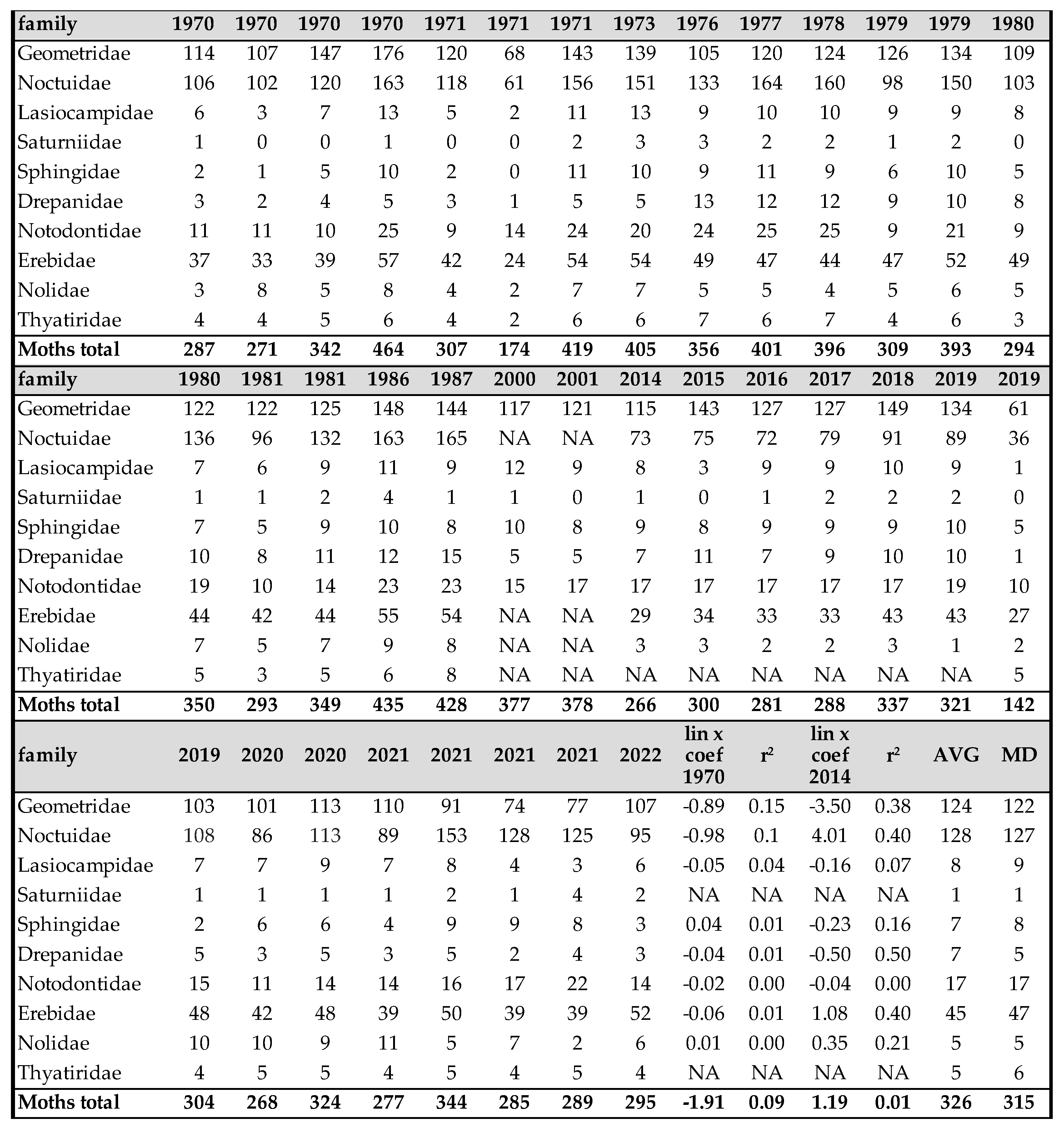

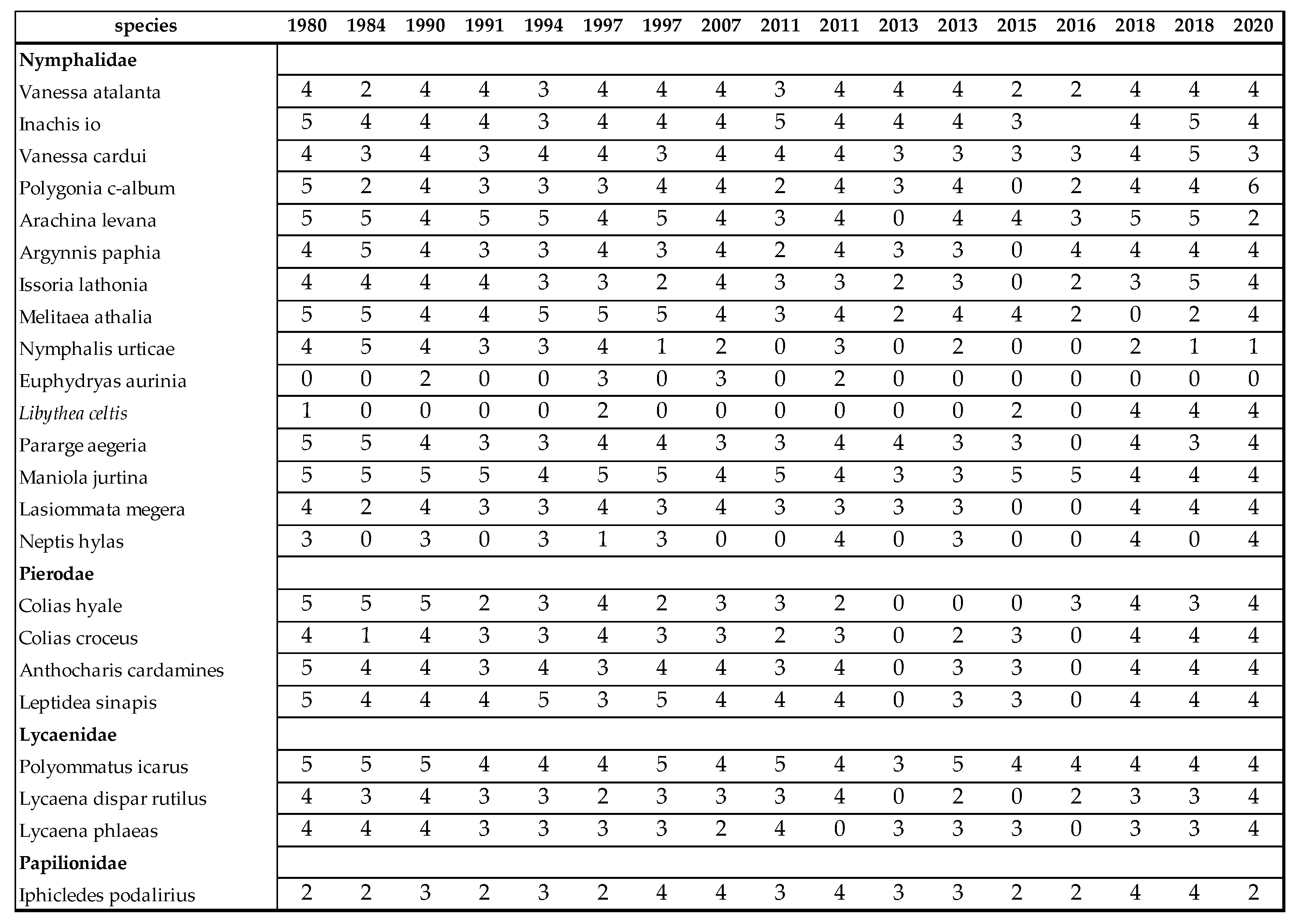

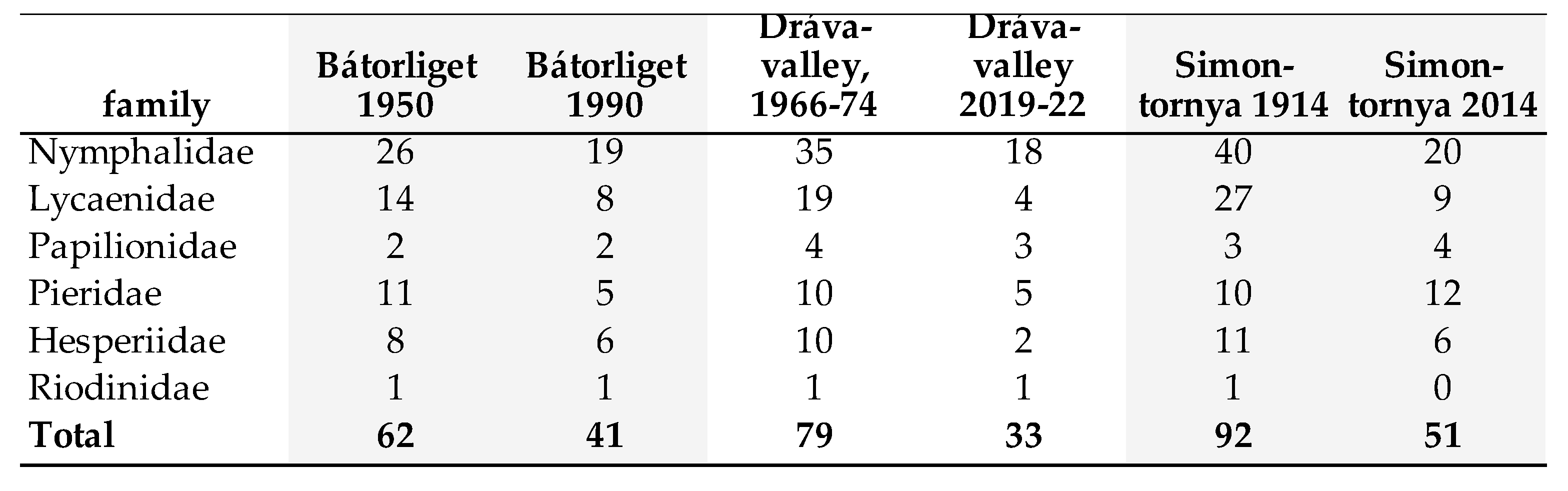

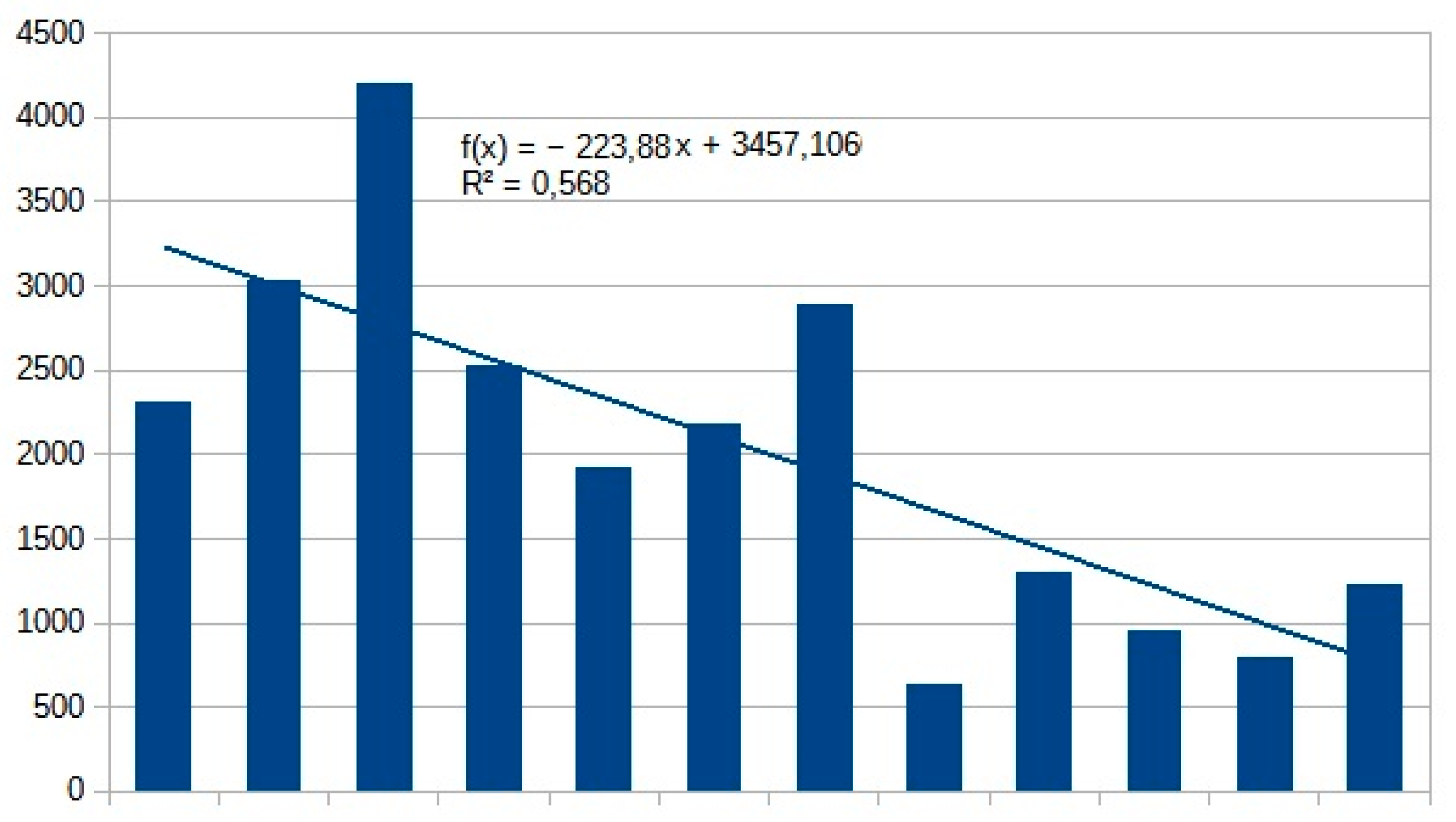

Butterflies (Rhopalocera)

4. Discussion

Symphyta

Aculeata

Bumblebees (Bombus spp.)

Diptera

Lepidoptera

Nocturnal macrolepidoptera

Butterflies (Rhopalocera)

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Molnár, A.V.; Takács, A. Megporzási válság. A pollináció mint természeti szolgáltatás. Ökológia. Természettudományi közlöny, 2016, 147, 303–305. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes, C.J. Pollinator decline – an ecological calamity in the making? Sci. Prog. 2018, 101, 121–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halmos, G.; A hosszútávú vonuló énekesmadár fajok állományváltozásának és populációdinamikájának vizsgálata. Doctoral thesis. ELTE Department of Systematic Zoology and Ecology, 2009, 117. Available online: https://teo.elte.hu/minosites/tezis2009/halmos_g.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2024).

- Potts, S.G.; Imperatriz-Fonseca, V.; Ngo, H.T.; Biesmeijer, J.C.; Breeze, T.D.; Dicks, L.V.; Garibaldi, L.A. , Hill, R.; Settele, J. and Vanbergen, A.J. Summary for policymakers of the assessment report of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services on pollinators, pollination and food production. Secretariat of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, Bonn, Germany. 2016; 36 pp.

- Dicks, L.V.; Breeze, T.D.; Ngo, H.T.; Senapathi, D.; Jiandong, A.; Aizen, M.A.; Basu, P.; Buchori, D.; Galetto, L.; Garibaldi, L.A.; et al. A global-scale expert assessment of drivers and risks associated with pollinator decline. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 5, 1453–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluser, S.; Peduzzi, P. Global Pollinator Decline: A Literature Review. A scientific report about the current situation, recent findings and potential solution to shed light on the global pollinator crisis. UNEP/DEWA/GRID-Europe, 2007; 10 pp.

- Marks, R. Native Pollinators. Fish Wildl. Habitat Manag. Leafl. 2005, 34, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service Protecting pollinators in the EU. European Parliament Briefing. 2021, 8 pp.

- Zombori, L. Adatok Nagykovácsi levéldarázsfaunájához I. (Hymenoptera, Symphyta). Folia Ent. Hung. 1973, 26, 217–224. [Google Scholar]

- Zombori, L. Jegyzetek Nagykovácsi levéldarázs faunájáról (Hymenoptera: Symphyta) II. Folia Ent. Hung. 1975, 28, 223–229. [Google Scholar]

- Zombori, L. Adatok Nagykovácsi levéldarázs-faunájához (Hymenoptera: Symphyta) III.-IV. Folia Ent. Hung. 1975, 28, 369–381. [Google Scholar]

- Zombori, L. Sawflies from the Agtelek National Park (Hymenoptera: Symphyta). In The fauna of the Aggtelek National Park, II. Mahunka, S. Ed., Hungarian Natural History Museum, Budapest. 1999, pp. 573–580.

- Zombori, L. Sawflies form Fertő-Hanság National Park (Hymenoptera: Symphyta). In The fauna of the Fertő-Hanság National Park, Mahunka, S. Ed., Hungarian Natural History Museum, Budapest. 2002, pp. 545–552.

- Haris, A. Sawflies of the Zselic Hills, SW Hungary Hymenoptera: Symphyta. Nat. Som. 2009, 15, 127–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haris, A. Sawflies of the Vértes Mountains Hymenoptera: Symphyta. Nat. Som. 2010, 17, 209–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haris, A. Sawflies of the Börzsöny Mountains North Hungary Hymenoptera: Symphyta. Nat. Som. 2011, 19, 149–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haris, A. Sawflies of Belső-Somogy (Hymenoptera: Symphyta). Nat. Som. 2012, 22, 141–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haris, A. Second contribution to the sawflies of Belső Somogy Hymenoptera: Symphyta. Nat. Som. 2018, 31, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haris, A. Sawflies from Külső-Somogy, South-West Hungary (Hymenoptera: Symphyta). Nat. Som. 2018, 32, 147–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haris, A. Sawflies of the Keszthely Hills and its surroundings. Nat. Som. 2019, 33, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haris, A. Sawflies of Southern part of Somogy county Hymenoptera: Symphyta. Nat. Som. 2020, 35, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haris, A. Sawflies of the Cserhát Mountains Hymenoptera: Symphyta. Nat. Som. 2021, 37, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haris, A. Second contribution to the knowledge of sawflies of the Zselic Hills (Hymenoptera: Symphyta). A Kaposvári Rippl-Rónai Múzeum Közleményei (Commun. Rippl-Rónai Mus. Kaposvár) 2022, 08, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haris, A.; Vidlička, L.; Majzlan, O.; Roller, L. Effectiveness of Malaise trap and sweep net sampling in sawfly research (Hymenoptera: Symphyta). Biologia, 2024; online. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roller, L. Sawfly (Hymenoptera, Symphyta) community in the Devínska. Kobyla Nat Reserve Biol. Bratisl. 1998, 53, 213–221. [Google Scholar]

- Roller, L. Seasonal flight activity of sawflies Hymenoptera, Symphyta in submontane region of the West Carpathians, Central Slovakia. Biol. Bratisl. 2006, 61, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Józan, Z. A Zselic méhszerű (Hymenoptera, Apoidea) faunájának alapvetése. The Apoidea (Hymenoptea) fauna of the Zselic Downs. Janus Pann. Múz. Évk. 1989, 34, 81–92. [Google Scholar]

- Józan, Z. A Zselic darázsfaunájának (Hymenoptera, Aculeata) állatföldrajzi és ökofaunisztikai vizsgálata. Zoologeographic and ecofaunistic study of the Aculeata fauna (Hymenoptera, Aculeata) of Zselic. Somogyi Múzeumok Közleményei 1992, 9, 279–292. [Google Scholar]

- Józan, Z. A Béda-Karapancsa Tájvédelmi Körzet fullánkos hártyásszárnyú (Hymenoptera, Aculeata) faunájának alapvetése. Aculeata (Hymenoptera, Aculeata) fauna of the Béda-Karapancsa Landscape Protection Area. Dun. Dolg. Term. Tud. Sor. 1992, 6, 219–246. [Google Scholar]

- Józan, Z. A Boronka-melléki Tájvédelmi Körzet fullánkos hártyásszárnyú (Hymenoptera, Aculeata) faunájának alapvetése. Aculeata (Hymenoptera, Aculeata) fauna of the Boronka Landscape Protection Area. Dun. Dolg. Term. Tud. Sor. 1992, 7, 163–210. [Google Scholar]

- Józan, Z. Adatok a tervezett Duna-Dráva Nemzeti Park fullánkos hártyásszárnyú (Hymenoptera, Aculeata) faunájának ismeretéhez. Data to the knowledge of the Aculeata (Hymenoptera, Aculeata) fauna of the planned Danube-Dráva National Park. Dun. Dolg. Term. Tud. Sor. 1995, 8, 99–115. [Google Scholar]

- Józan, Z. A Mecsek méhszerű faunája (Hymenoptera, Apoidea). The Apoidea (Hymenoptera) fauna of the Mecsek Mountains (Hungary: South Transdanubia). Janus Pann. Múz. Évk. 1995; 40, 29–43. [Google Scholar]

- Józan, Z. A Baláta környék fullánkos hártyásszárnyú faunájának (Hym., Aculeata) alapvetése. Aculeata fauna of Lake Baláta (Hym., Aculeata). Somogyi Múzeumok Közleményei 1996, 12, 271–297. [Google Scholar]

- Józan, Z. A Duna-Dráva Nemzeti Park fullánkos hártyásszárnyú (Hymenoptera, Aculeata) faunája. – The Aculeata fauna of the Duna-Dráva National Park, Hungary (Hymenoptera, Aculeata). Dun. Dolg. Term. Tud. Sor. 1998, 9, 291–327. [Google Scholar]

- Józan, Z. A Villányi-hegység fullánkos hártyásszárnyú (Hymenoptera, Aculeata) faunája. The Aculeata (Hymenoptera) fauna of the Villány Hills, South Hungary. Dun. Dolg. Term. Tud. Sor. 2000, 10, 267–283. [Google Scholar]

- Józan, Z. A Mecsek kaparódarázs faunájának (Hymenoptera: Sphecoidea) faunisztikai, állatföldrajzi és ökofunisztikai vizsgálata. Faunistical, zoogeographical and ecofaunistical investigation on the Sphecoids fauna of the Mecsek Montains (Hymenoptera, Sphecoidea). Nat. Som. 2002, 3, 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Józan, Z. Az Őrség és környéke fullánkos hártyásszárnyú faunájának alapvetése (Hymenoptera, Aculeata). Aculeata (Hymenoptera, Aculeata) fauna of Őrség and its surroundings. Praenorica Fol. Hist.-nat. 2002, 6, 59–96. [Google Scholar]

- Józan, Z. A Mecsek fullánkos hártyásszárnyú faunája (Hymenoptera, Aculeata). Aculeata fauna of Mecsek Hills (Hymenoptera, Aculeata). Folia Comloensis, 2006, 15, 219–238. [Google Scholar]

- Józan, Z. Új kaparódarázs fajok (Hymenoptera, Sphecidae) Magyarország faunájában. New sphecid wasps (Hymenoptera, Sphecidae) in the fauna of Hungary. Somogyi Múzeumok Közleményei 2008, 18, 81–83. [Google Scholar]

- Józan, Z. A Barcsi borókás fullánkos faunája, III. (Hymenoptera: Aculeata). Aculeata fauna of Barcs Juniper Woodland (Hymenoptera: Aculeata). Nat. Som. 2015, 26, 95–108. [Google Scholar]

- Tóth, S. Angaben zur Kenntnis der Schwebfliegen-Fauna der Slowakei (Diptera: Syrphidae). Fol. Mus. Hist.-Nat. Bakony. 1990, 9, 91–108. [Google Scholar]

- Tóth, S. Magyarország zengőlégy faunája (Diptera: Syrphidae). Hoverflies of Hungary (Diptera: Syrphidae). e-Acta Naturalia Pannonica, 2011, Suppl. 1., 1–408.

- Tóth, S. Magyarország fürkészlégy faunája (Diptera: Tachinidae). Tachinid flies of Hungary (Diptera: Tachinidae). e-Acta Naturalia Pannonica, 2013, 5, Suppl. 1, 1–321.

- Tóth, S. A hazai bögölyök nyomában (Diptera: Tabanidae). Horse-flies of Hungary (Diptera: Tabanidae). e-Acta Nat. Pannonica 2023, Suppl. 4, 1–124.

- Ábrahám, L. Biomonitoring of the buttetfly fauna in the Drava region {Lepidopteia: Diurna). Nat. Som. 2005, 7, 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Ábrahám, L. A Boronka-melléki Tájvédelmi Körzet nagylepke faunájának természetvédelmi értékelése I. (Lepidoptera). Nature conservation evaluation of the macrolepidoptera fauna of Boronka Landscape Protected Area (Lepidoptera). Dun. Dolg. Term. Tud. Ser. 1992, 7, 241–271. [Google Scholar]

- Ábrahám, L. Bakonynána és környéke nagylepke faunája (Lepidoptera) Macrolepidoptera fauna of Bakonynána region. Fol. Mus. Hist.-Nat. Bakonyensis 1991, 10, 85–104. [Google Scholar]

- Ábrahám, L. Lápi tarkalepke Euphydryas aurinia (Rottembtirg, 1775). Marsh fritillary Euphydryas aurinia (Rottembtirg, 1775). In Natura 2000 fajok és élőhelyek Magyarországon. Ed. Haraszthy, L., Pro Vértes Közalapítvány, Csákvár 2014, 323-326.

- Ábrahám, L.; Herczig, B.; Bürgés, G. Faunisztikai adatok a Keszthelyi-hegység nagylepke faunájának ismeretéhez (Lepidoptera: Macrolepidoptera}. Data to the Macrolepidoptera fauna of Keszthely Hills (Lepidoptera: Macrolepidoptera}. Nat. Som. 2007, 10, 303–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ábrahám, L.; Uherkovich, À. 1993: A Zselic nagylepkéi (Lepidoptera) 1. Bevezetés és faunisztikai alapvetés. Macrolepidoptera fauna of Zselic (Lepidoptera) Introduction and biomonitoring. Janus Pann. Múz. Évk. 1993, 38, 47–59. [Google Scholar]

- Uherkovich, Á. Long-term monitoring of biodiversity by the study of butterflies and larger moths (Lepidoptera) in Sellye region (South Hungary, co. Baranya) in the years 1967–2022. Nat. Som. 2022, 9, 95–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillich, F. Aus der Arthropodenwelt Simontornya’s, Pillich, F. private edition, Simontornya, Hungary, 1914. 172 pp.

- Sáfián, Sz. Butterflies of Kercaszomor (Őrség), Western Hungary (Lepidoptera: Papilionoidea and Hesperioidea). Nat. Som. 2011, 19, 251–262. [Google Scholar]

- Ács, E. ; Zs. Bálint, Ronkay, G.; Ronkay, L.; Szabóky, Cs.;Varga, Z.; Vojnits, A. The Lepidoptera of the Bátorliget Nature Conservation areas. The Bátorliget Nature Reserves – after forty years Vol. 2. Mahunka, S. Ed. Hungarian Natural History Museum, Budapest, 1991, pp. 505–540.

- Čanády, A, Príspevok k poznaniu výskytu denných motýľov (Rhopalocera) v urbánnom prostredí Košíc. (Slovensko). Contribution to the knowledge of the occurrence of butterflies (Rhopalocera) in the urban environment of Košice. (Slovakia). Folia Faun. Slovaca 2014, 19, 235–241. [Google Scholar]

- Dietzel, G. A Bakony nappali lepkéi. Butterflies of Bakony Mountains. In: A Bakony természettudományi kutatásának eredményei 21. Bakonyi Természettudományi Múzeum, Bakony NaturalHistory Museum Ed. Zirc. 1997, pp. 1–212.

- Sarvašová, L. Denné motýle (lepidoptera, papilionoidea) lúk kúpeľov sliač a okolia (Slovensko). Butterflies (lepidoptera, papilionoidea) meadow of spas sliač and surroundings (Slovakia). Folia Faun. Slovaca 2016, 21, 63–71. [Google Scholar]

- Gergely, P. A pomázi Majdán-fennsík nappali lepkéinek megfigyelései 2000 és 2020 között (Lepidoptera: Rhopalocera) Observations of butterflies in the Majdan plateau of Pomáz (Hungary) between 2000 and 2020 (Lepidoptera: Rhopalocera). Lepidopterol. Hung. 2021, 17(2), 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gór, Á. 2018: Lepkefaunisztikai kutatások Biatorbágyon és környékén (Lepidoptera). Lepidoptera survey in Biatorbágy (Hungary) and its surrounding areas. Eacta Nat. Pannonica 2018, 16, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, P. A Csombárdi-rét Természetvédelmi Terület nappali lepkéinek alapállapot felmérése (Lepiodptera). The basic survey of the butterfies in the Csombárd-meadow Nature Conservation Area (Lepidoptera). Nat. Som. 2017, 30, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Németh, L. Data to the knowledge of the Macrolepidoptera-fauna of the Tapolca basin. Fol. Mus. Hist.-Nat. Bakonyensis 1991, 10, 105–136. [Google Scholar]

- Szabóky, Cs.; Samu, F.; Szeőke, K.; Petrányi, G. Simontornya lepkevilágáról (Lepidoptera). Moths and butterflies of Simontornya. In: Simontornya ízeltlábúi. Arthropods of Simontornya. Magyar Biodiverzitás-kutató Társaság, Hungarian Biodiversity Research Society Ed., Budapest, 2014, pp. 143–186.

- Hudák, T. A nappali lepkefauna vizsgálata Székesfehérváron (Lepidoptera: Rhopalocera). Investigation on the butterfly fauna of Székesfehérvár (Lepidoptera: Rhopalocera). Nat. Som. 2018, 31, 113–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, J.; Korompai, T.; Horokán, K.; Hirka, A.; Gáspár, Cs.; Kozma, P.; Csóka, G.; Csuzdi, Cs. 2022: Analysis of the Macrolepidoptera fauna in Répáshuta based on the catches of a light-trap between 2014-2019. Acta Univ. Esterházy, Sect. Biol. 2022, 47, 59–75. [Google Scholar]

- Árnyas, E.; Szabó, S.; Tóthmérész, B.; Varga, Z. Lepkefaunisztikai vizsgálatok fénycsapdás gyűjtéssel az Aggteleki Nemzeti Parkban. Moth fauna studies with light trap collection in the Aggtelek National Park. Természetvédelmi Közl. 2004, 11, 34–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kovács, L. Bátorliget nagylepke-faunája. Macrolepidoptera fauna of Bátorliget. pp. 326–380, 483–484. In: Bátorliget élővilága. (Die Tier- und Pflanzenwelt desNaturschutzgebietes von Bátorliget und seiner Umgebung). Székessy, V. ed., Akadémiai kiadó, Budapest, Hungary; 1953, 486 pp.

- Infusino, M.; Brehm, G.; Di Marco, C.; Scalercio, S. Assessing the efficiency of UV LEDs as light sources for sampling the diversity of macro-moths (Lepidoptera). Eur. J. Entomol. 2017, 114, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Liang, G.; Lu, Y. Response of Different Insect Groups to Various Wavelengths of Light under Field Conditions. Insects 2021, 12, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulet, H. Herbicides, beetles, and the decline of insectivorous birds. Canada’s oldest field naturalist club. 2023, 35 pp. https://ofnc.ca/wp–content/uploads/2018/01/Herbicides_beetles_birds.pdf.

- Liston, A.D. Compendium of European Sawflies. List of species, modern nomenclature, distribution, foodplants, identification literature. Chalastos Forestry, Gottfrieding, Germany, 1995, pp. 1–190.

- Roller, L.; Haris, A. Sawflies of the Carpathian Basin, History and Current Research. In Nat. Som. 2008, 11, 1–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, E.; Haris, A. Contribution to the knowledge of the sawflies (Hymenoptera: Symphyta) from Turkey. Nat. Som. 2021, 37, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbir, J.; Martín, L.O.; Lloveras, X.R. Impact of Climate Change on Sawfly (Suborder: Symphyta) Polinators in Andalusia Region, Spain. 93-111. In Handbook of Climate Change and Biodiversity, , ; Walter Leal Filho, W.L., Barbir, J., Preziosi, R., Eds.; In series: Climate Change Management; Springer Nature Switzerland AG.: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; p. 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olszewski, P. , Dyderski, M.K.; Dylewski, L., Bogusch, P., Schmid-Egger, Ch..; Ljubomirov, T.; Zimmermann, D.; Le Divelec, R.; Wiśniowski, B.; Twerd, L.; Pawlikowski, T.; Mei, M.; Florina Popa, A.; Szczypek, J.; Sparks, T.; Puchałka, R. European beewolf (Philanthus triangulum) will expand its geographic range as a result of climate warming. Reg. Environ. Change 2022, 22, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eickermann, M.; Junk, J.; Rapisarda, C. Climate Change and Insects. Insects 2023, 14, 672–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.H. Sphex ichneumoneus and Sphex pensylvanicus (Hymenoptera: Sphecidae) in Atlantic Canada: evidence of recent range expansion into the region. Can. Field-Nat. 2020, 134, 52–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vélez, D.; Silva, D.P.; Vivallo, F. Where could Centris nigrescens (Hymenoptera: Apidae) go under climate change? J. Apic. Res., 2023, 62, 1082–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, D.; Schoder, S.; Zettel, H.; Hainz-Renetzeder, Ch.; Kratschmer, S. Changes in the wild bee community (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) over 100 years in relation to land use: a case study in a protected steppe habitat in Eastern Austria. J. Insect Conserv. 2023, 27, 625–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogusch, P.; Horák, J. Saproxylic bees and wasps. In: Saproxylic insects: diversity, ecology and conservation, Ulyshen, M. Ed., Springer Books, Bern, Switzerland, 2018, pp. 217–235. [CrossRef]

- Pearce-Higgins, J.W.; Beale, C.M.; Oliver, T.H.; August, T.A.; Carroll, M.; Massimino, D.; Ockendon, N.; Savage, J.; Wheatley, C.J.; Ausden, M.A.; et al. A national-scale assessment of climate change impacts on species: assessing the balance of risks and opportunities for multiple taxa. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 213, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smetana, V.; Šima, P.; Bogusch, P.; Erhart, J.; Holý, K.; Macek, J.; Roller, L.; Straka, J. Hymenoptera of the selected localities in the environs of Levice and Kremnica towns. Acta Musei Tekovensis Levice 2015, 10, 44–68. [Google Scholar]

- Šima, P.; Straka, J. First records of Heriades rubicola Pérez, 1890 (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae) and Nomada moeschleri Alfken, 1913 (Hymenoptera: Apidae) from Slovakia. Entomofauna Carpathica 2016, 28, 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Mielczarek, L. The first records of Chalcosyrphus pannonicus (Ooldenberg, 1916) (Diptera: Syrphidae) in Poland and Slovakia. Dipteron 2014, 30, 50–54. [Google Scholar]

- Tóth, S. A Dél-Dunántúl bögöly faunájáról (Diptera: Tabanidae). Nat. Som. 2016, 28, 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Nartshuk, E.P.; Krivokhatsky, V.; Evenhuis, N. First record of a bee fly (Diptera: Bombyliidae) parasitic on antlions (Myrmeleontidae) in Russia. Russ. Entomol. J. 2019, 28, 189–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ábrahám, L. Micomitra stupida (Diptera, Bombyliidae): a new parasite of Euroleon nostras (Neuroptera, Myrmeleontidae). Dun. Dolg. Term. Tud. Sor. 1998, 9, 421–422. [Google Scholar]

- Yeates, D.K. The evolutionary pattern of host use in the Bombyliidae (Diptera): a diverse family of parasitoid flies. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. Lond. 1997, 60, 149–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kells, A.R. , Goulson, D. Preferred nesting sites of bumblebee queens (Hymenoptera: Apidae) in agroecosystems in the UK. Biol. Conserv. 2003, 109, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, M.C. Towards the conservation of aculeate Hymenoptera in Europe. – Council of Europe Press, Strasbourg, France, 1991; 44 pp.

- Williams, P.H. The distribution and decline of British bumblebees (Bombus Latr.). J. Apic. Res. 1982, 121, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plowright, C.M.S.; Plowright, R.C.; Williams, P.H. Replacement of Bombus muscorum by Bombus pascuorum in northern Britain? Can. Entomol. 1997, 129, 985–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakab D, Tóth M, Szarukán I, Szanyi S, Józan Z, Sárospataki M, Nagy A (2023) Long-term changes in the composition and distribution of the Hungarian bumble bee fauna (Hymenoptera, Apidae, Bombus). J. Hymenopt. Res. 2023, 96, 207–237. [CrossRef]

- Sárospataki, M.; Novák, J.; Molnár, V. Hazai poszméhfajok (Bombus spp.) veszélyeztetettsége és védelmük szükségessége. Bumblebees of Hungary (Bombus spp.) and their conservation. Természetvédelmi Közlemények 2004, 11, 299–307. [Google Scholar]

- Šima, P.; Smetana, V.; Čížek, J. Records of Bombus (Megabombus) argillaceus (Hymenoptera: Apidae: Bombini) from Slovakia and notes on the record from the Czech Republic. Klapalekiana 2014, 50, 101–106. [Google Scholar]

- Šima, P.; Smetana, V. Bombus (Cullumanobombus) semenoviellus (Hymenoptera: Apidae: Bombini) new species for the bumble bee fauna of Slovakia. Klapalekiana 2012, 48, 141–147. [Google Scholar]

- Smetana, V. Čmele a spoločenské osy (Hymenoptera: Bombini, Polistinae et Vespinae) na vybraných lokalitách v národnom parku Veľká Fatra. Acta Mus. Tek. Levice 2008, 7, 23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Smetana, V. Výsledky výskumu čmeľovitých (Hymenoptera: Bombidae) na vybraných lokalitách v Čergove, Bachurni a v bradlovom pásme Spišsko-šarišského medzihoria. Nat. Carp. 2000, 41, 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Šima, P.; Smetana, V. Čmele (Hymenoptera: Bombidae) na vybraných lokalitách Popradskej kotliny. Nat. Tut. 2019, 23, 169–180. [Google Scholar]

- Tkalců, B. Vier für die Slowakei neu festgestellte Bienenarten (Hymenoptera, Apoidea). Biológia (Bratisl. ) 1973, 28, 679–687. [Google Scholar]

- Móczár, M. Magyarország és a környező területek dongóméheinek (Bombus Latr.) rendszere és ökológiája. Taxonomy and ecology of bumblebees (Bombus Latr.) of Hungary and the surrounding areas. Annls hist. -nat. Mus. natn. (Ser. Nov.) 1953, 4, 131–159. [Google Scholar]

- Móczár; M. A dongóméhek (Bombus Latr.) faunakatalógusa (Cat. Hym. IV). Faunistic catalogue of Bumblebees (Cat. Hym. IV). Folia ent. hung. (Ser. Nov.) 1953, 6, 197–228. [Google Scholar]

- Tanács; L. The Apoidea (Hymenoptera) of the Tisza–dam. Tiscia 1975, 10, 55–66. [Google Scholar]

- Biella, P.; Ćetković, A.; Gogala, A.; Neumayer, J.; Sárospataki, M.; Šima, P.; Smetana, V. Northwestward range expansion of the bumblebee Bombus haematurus into Central Europe is associated with warmer winters and niche conservatism. Insect Sci. 28(3), 861–872. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šima, P. , Smetana, V. Quo vadis Bombus haematurus? An outline of the ecology and biology of a species expanding in Slovakia. Acta Mus. Tek. Levice 2018, 11, 41–65. [Google Scholar]

- Biella, P.; Galimberti, A. The spread of Bombus haematurus in Italy and its first DNA barcode reference sequence. Fragm. Entomol. 2020, 52, 1–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmont, P.; Franzén, M.; Lecocq, T.; Harpke, A.; Roberts, S.P.M.; Biesmeijer, J.C.; Castro, L.; Cederberg, B.; Dvořák, L.; Fitzpatrick, Ú.; et al. Climatic Risk and Distribution Atlas of European Bumblebees. Biorisk 2015, 10, 1–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miličić, M.; Vujić, A.; Cardoso, P. Effects of climate change on the distribution of hoverflyspecies (Diptera: Syrphidae) in Southeast Europe. Biodivers. Conserv. 2018, 27, 1173–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN SSC HSG/CPSG European Hoverflies: Moving from Assessment to Conservation Planning. A report to the European Commission by the IUCN SSC Conservation Planning Specialist Group (CPSG) and the IUCN SSC Hoverfly Specialist Group (HSG). Conservation Planning Specialist Group, Apple Valley, MN, USA. 2022, 84 pp.

- Sommaggio, D.; Zanotelli, L.; Vettorazzo, E.; Burgio, G.; Fontana, P. Different Distribution Patterns of Hoverflies (Diptera: Syrphidae) and Bees (Hymenoptera: Anthophila) along Altitudinal Gradients in Dolomiti Bellunesi National Park (Italy). Insects 2022, 13, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herczeg, T.; Száz, D.; Blahó, M.; Barta, A. , Gyurkovszky, M.; Farkas, R.; Horváth, G. 2015: The effect of weather variables on the flight activity of horseflies (Diptera: Tabanidae) in the continental climate of Hungary. Parasitol. Res. 2015, 114, 1087–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dörge, D.D.; Sarah Cunze, S.; Klimpel, S. Incompletely observed: niche estimation for six frequent European horsefly species (Diptera, Tabanoidea, Tabanidae). Parasit Vectors. 2020, 13, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Régnière, J.; Thireau, J.C.; Saint-Amant, R.; Martel, V. Modeling Climatic Influences on Three Parasitoids of Low-Density Spruce Budworm Populations. Part 3: Actia interrupta (Diptera: Tachinidae). Forests 2021, 12, 1471–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boesi, R.; Polidori, C.; Andrietti, F. Searching for the Right Target: Oviposition and Feeding Behavior in Bombylius Bee Flies (Diptera: Bombyliidae). Zool. Stud. 2009, 48, 141–150. [Google Scholar]

- Fox., R.J.P. Fox., R.J.P. Citizen science and Lepidoptera biodiversity change in Great Britain. PhD. Thesis. University of Exeter 2020, 297 pp. https://ore.exeter.ac.uk/repository/bitstream/handle/10871/120925/FoxR.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 18. 03. 2024).

- Conrad, K.F.; Warren, M.S.; Fox, R.; Parsons, M.S.; Woiwod, I.P. Rapid declines of common, widespread British moths provide evidence of an insect biodiversity crisis. Biol. Conserv. 2006, 132, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkola, K. Population trends of Finnish Lepidoptera during 1961-1996. Entomol. Fenn. 1997, 8, 121–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, G.M.; Kawahara, A.Y.; Daniels, J.C.; Bateman, C.C.; Scheffers, B.R. Climate change effects on animal ecology: butterflies and moths as a case study. Biol. Rev. 2021, 96, 2113–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangels, J.K. Land use and climate change: Anthropogenic effects on arthropod communities and functional traits. PhD. Thesis. Department of Biology, Technical University of Darmstadt (Germany), Darmstadt, 2017, pp. 169. https://tuprints.ulb.tu-darmstadt.de/7156/1/Dissertation_Mangels.pdf (accessed on 18. 03. 2024).

- Van Zandt, P.A.; Johnson, D.D.; Hartley, Ch.; LeCroy, K.A.; Shew, H.W.; Davis, T.B.; Lehnert, M.S. Which Moths Might be Pollinators? Approaches in the Search for the Flower-Visiting Needles in the Lepidopteran Haystack. Ecol. Entomol. 2019, 45, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turčáni, M.; Kulfan, J.; Minďáš, J. Penetration of the south European butterfly Libythea celtis (Laicharting 1782) northwards: Indication of global man made environmental changes? Ekológia 2003, 33, 28–41. [Google Scholar]

- Bury, J.; Maslo, D.; Obszarny, M.; Paluch, F. Expansion of Iphiclides podalirius (Linnaeus, 1758) (Lepidoptera: Papilionidae) on Podkarpacie Region (SE Poland) in 2010–2014. Park. Nar. I Rezerwaty Przyr. 2015, 34, 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Gavrilov, M.B. , Radakovič, M.G., Sipos, Gy., Mezősi, G., Gavrilov, G., Lukić, T., Basarin, B., Benyhe, B., Fiala, K., Kozák, P. ; Perič, Z.M.; et al. Aridity in the central and southern Pannonian basin. Atmosphere 2020, 11–12, 1269–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).