Definitions Used in the Text

Social temperature: In large systems, individual organisms are analogous to particles, with their unique histories equivalent to thermal fluctuations. In thermodynamics, temperature is the particle's average kinetic energy. Likewise, social or temperature measures arousal [1-4] or social kinetic energy [2,5]. Arousal is the function of resource density, with abundance permitting low arousal, characterizing low social temperature [6]. Food scarcity causes resource competition, erratic and risky behavior [7], forming high social temperatures [8], and substantial selective pressures (Harris et al., 2010). See further discussion in the text.

Orthogonality: Orthogonality is a system design property that guarantees that modifying the technical effect produced by a system component neither creates nor propagates side effects to other elements. In contrast to the organism or ecosystem, which is limited by its lifetime, the genome contains the evolutionary history and potential, which can ensure the species' stability and provide a foundation for evolution. Hence, in evolutionary biology, living space and the genome form an orthogonal relationship analogous to space and time in physics.

1. Introduction

"Thermodynamics, correctly interpreted, does not just allow Darwinian evolution; it favors it." Boltzmann

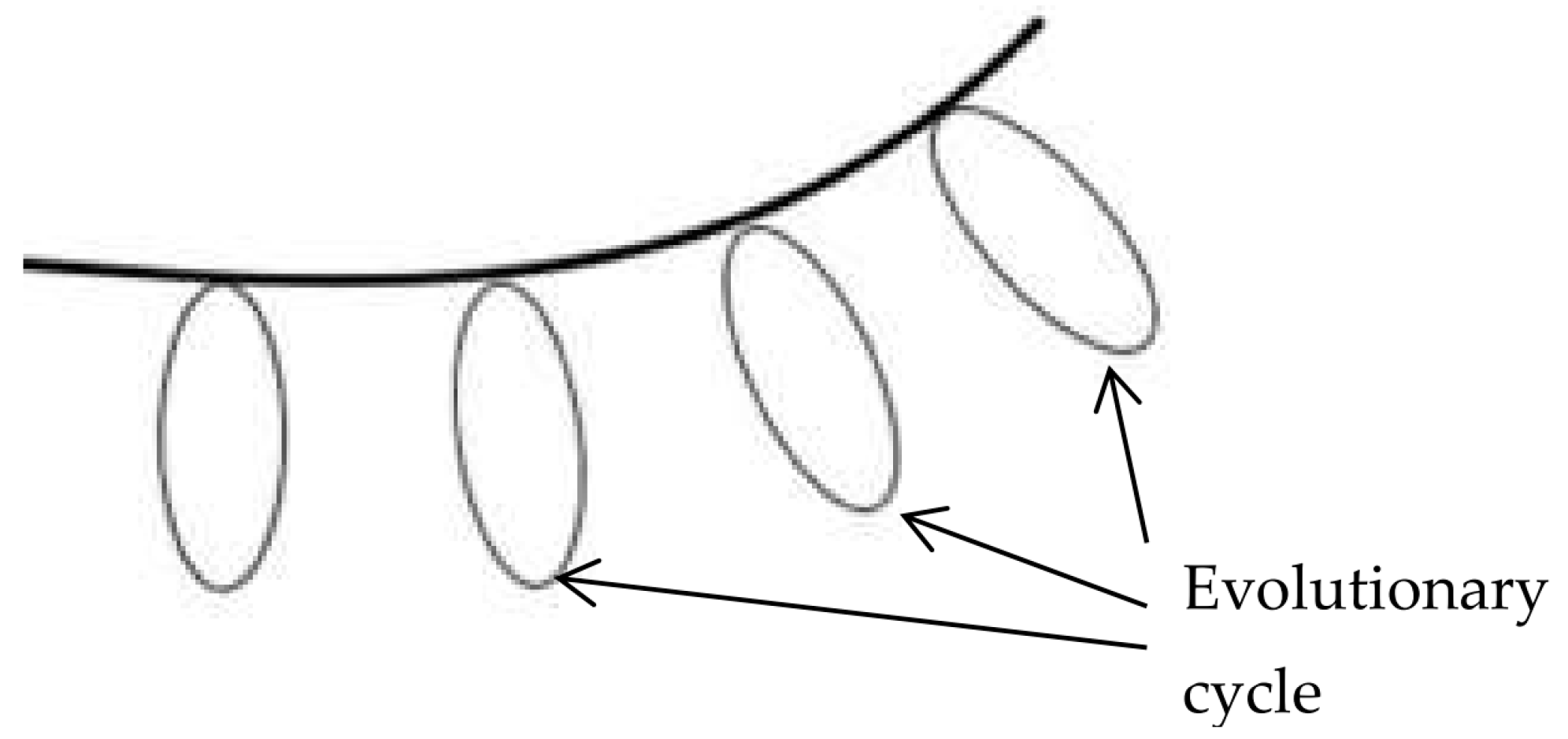

Advanced computational analyses of the fossil record reveal the cyclical nature of evolutionary processes, driven by the interplay of extinctions and diversifications. Across all levels of biological organization—cells, tissues, viruses, plants, and animals—organisms exhibit remarkable adaptability, responding flexibly to their metabolic, physiological, genetic, cognitive, and behavioral demands. While cellular biochemical reactions can often precede bidirectionally, the essence of life is centered on growth and development. This process manifests through various properties (Chaisson, 2011, 2014) and periodic patterns across numerous spatial and temporal scales (Roberts and Mannion, 2019).

Population dynamics are intricately shaped by population size, resource availability, and interaction networks [9]. For instance, increased population density often exacerbates resource scarcity, heightening competition. Biological systems, however, demonstrate resilience by conserving critical resources—such as ATP, glucose, or water—which leads to delayed responses to resource depletion. These delays result in population fluctuations and environmental shifts, forming the basis for macroevolution. Such macroevolution occurs through multi-phase processes of varying durations (McMahon and Ivarsson, 2019) and periodicities (Roberts and Mannion, 2019), culminating in stepwise genetic and morphological transformations.

The role of entropy production in biological evolution has long been a subject of inquiry (Cushman, 2023; Kondepudi et al., 2020). Biological systems harness energy and materials from their surroundings to build tissues through dynamic, energy-intensive processes. Assembly Theory further emphasizes that complex objects carry evidence of their intricate causal histories, suggesting that objects can be characterized by their potential formation pathways (Sharma et al., 2023).

Nevertheless, genetic information determines the evolutionary trajectory, enabling adaptations that reflect internally generated self-organization (Sundstrom and Allen, 2019). However, examples of functional loss challenge the predictions of Assembly Theory. For instance, while whales have sacrificed certain terrestrial traits during their evolutionary transition to aquatic life (Werth), this shift has not diminished their complexity relative to their mammalian ancestors. Similarly, endoparasites often simplify their structures and physiological functions. Yet, their evolutionary history and classification remain intact, highlighting the nuances in the relationship between function loss and complexity.

Darwinian evolution, predicated on generational changes in heritable traits, asserts that individuals with advantageous traits are more likely to survive and reproduce (Darwin et al., 2009). Over multiple generations, such traits enhance a species' adaptation to its environment. However, the increasing complexity observed in evolution, particularly in the human brain, challenges traditional Darwinian interpretations (Vopson, 2022; Vopson and Lepadatu, 2022). For example, findings from the Long-Term Evolution Experiment (LTEE) with E. coli have primarily revealed fitness improvements arising from gene disruptions or losses rather than gain-of-function mutations (Cooper and Lenski, 2000). The emergence of novel functional proteins requires particular mutational events, making producing such proteins exceedingly rare. These findings suggest that while Darwinian mechanisms explain much of evolutionary adaptation, they may not fully account for the emergence of complexity within biological systems.

The increasing complexity observed in evolution seems to contradict the second law of thermodynamics, which states that the total entropy of a system either increases or remains constant in any spontaneous process; it never decreases (reviewed by Boojari [10]). Thermodynamics describes spontaneous processes as those occurring without external input.

where G is the Gibbs free energy and H is enthalpy ≈ internal organization.

A reaction is spontaneous when Gibbs free energy (ΔG) is negative. Conversely, endothermic reactions, characterized by positive ΔG values, require external energy to proceed. This fundamental principle allows us to apply thermodynamic concepts, such as entropy, to diverse scientific disciplines, including evolution (Lotka, 1922; Sella and Hirsh, 2005; Bartlett, 2017; Gladyshev, 2017; Pross and Pascal, 2017; Sherwin, 2018; Roach et al., 2019; Cohen and Marron, 2020; Kondepudi et al., 2020; Skene, 2020; Wong, 2020; Torday, 2021; Ao, 2005, 2008; Barton and Coe, 2009; Cushman, 2021, 2023; Vopson, 2022).

Individual organisms can be modeled as particles, with their life histories analogous to thermal fluctuations (Schweitzer and Hołyst, 2000). This analogy extends to predictable collective behaviors, making thermodynamic principles, such as the maximum entropy principle, broadly applicable. The principle states that in a large ensemble, the distribution of any quantity tends toward the configuration with the highest entropy. This concept has been successfully applied across biology, chemistry, economics, and even consciousness science (Jiang et al., 2015; Klimek et al., 2019; Déli and Kisvárday, 2020; Déli et al., 2021) as well as evolutionary theory (Frank, 2009; Frank and Smith, 2011; Vanchurin et al., 2022).

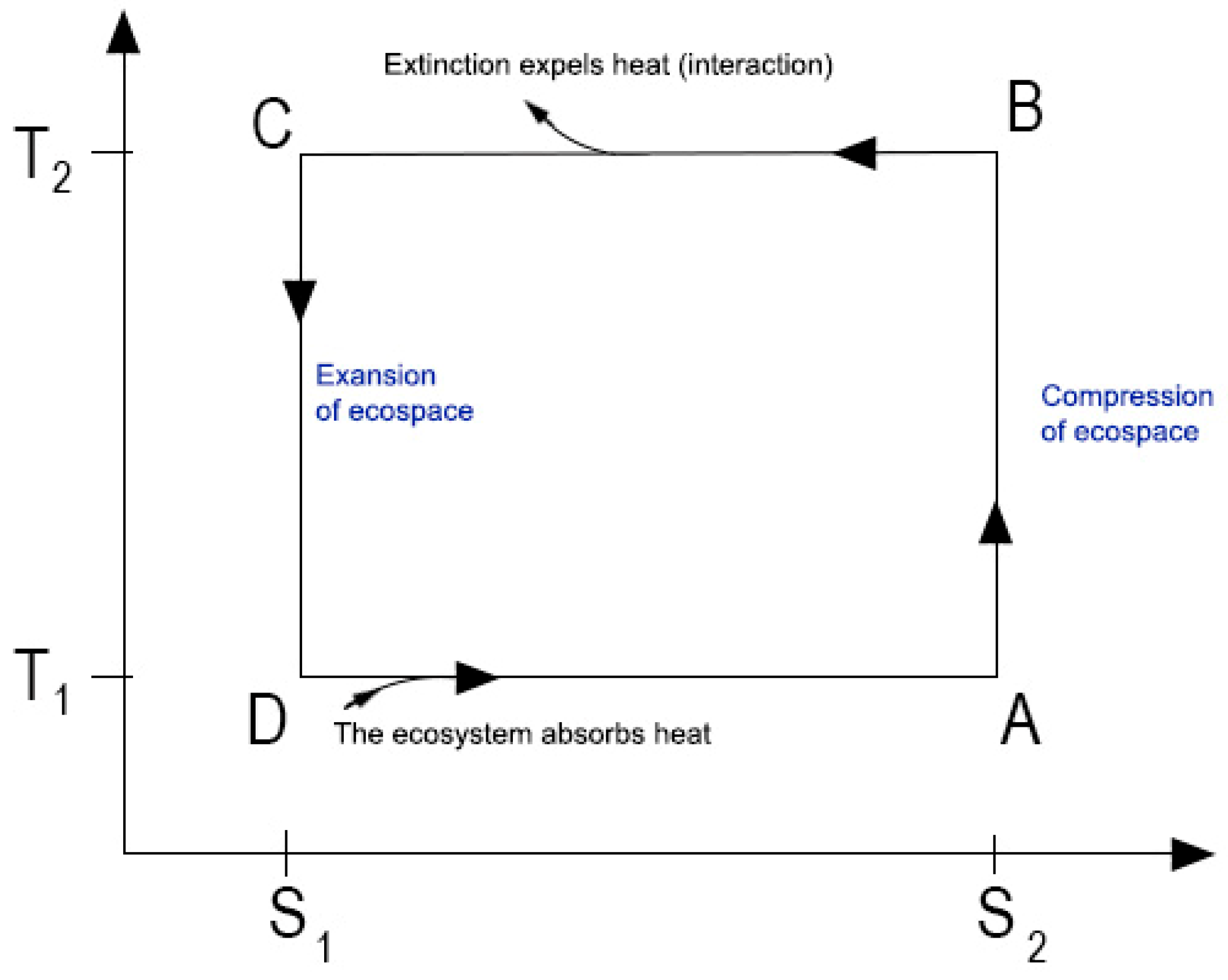

Crucially, systems can display contrasting behaviors depending on their state variables. These thermodynamic state variables describe the condition of a system and include energy (E), Helmholtz free energy (F), Gibbs free energy (G), enthalpy (H), pressure (P), entropy (S), temperature (T), and volume (V). An ideal evolutionary cycle can be divided into well-defined phases, each characterized by predictable shifts in entropy, population size, resource availability, and genetic diversity.

In the first phase, extinction events act as bottlenecks, compressing genetic diversity while conserving evolutionary potential. Low-entropy populations emerging from such bottlenecks accelerate the development of gene order and complexity. Conversely, high-entropy ecosystems are shaped by the dominant role of natural selection, which refines adaptations within a broader and more diverse genetic pool. The genetic material represents a stable medium of history and potential throughout this chaotic process.

2. Considerations of Entropy

Entropy, a fundamental thermodynamic quantity, plays a central role in the second law of thermodynamics, which states that the total entropy of an isolated system can never decrease over time (reviewed by Boojari, 2022). Entropy is often interpreted as measuring a system's thermal energy unavailable for conversion into mechanical work. Although entropy may seem abstract, its effects are intuitively familiar—such as the irreversibility of a broken egg. This irreversibility sets it apart from most physical laws, which are time-symmetric and do not distinguish between the past and the future.

In 1948, Claude Shannon introduced information entropy, a measure of uncertainty or unpredictability within a system. Rényi later generalized this concept as a tool to assess diversity and complexity in fields such as ecology and statistics. A notable relationship between Rényi's exponent (α) and the inverse temperature parameter1 (β)—or "coldness," the reciprocal of thermodynamic temperature—underscores the link between system behavior and temperature (Baez, 2011). In this context, β indicates how strongly expected outcomes influence an agent's choice probabilities.

Adaptive behavior exemplifies this relationship. High β values indicate an exploitative state where the agent strongly favors the highest-value option, akin to a "hot" state characterized by impulsivity, heightened arousal, and competitive behaviors. During immense environmental change, organisms often shift from exploitative strategies to exploratory ones, reflecting changes in uncertainty and learning rates (Jepma et al., 2020). A low β value represents a "cold" state, where lesser event frequency and increased synergy promote adaptive strategies and learning capabilities.

This connection between entropy, temperature, and adaptive behavior parallels Landauer's principle, a cornerstone of information theory. Landauer demonstrated that irreversible computation, i.e., memory formation, results in information erasure, dissipating heat into the environment (Landauer, 1961). Biological organization —from genetic storage to neural learning—mirrors this process. The resulting "coldness" of biological systems reflects their efficiency in preserving information and maintaining adaptive stability.

In this cold state, species that capture more energy gain a competitive edge in resource acquisition (Hall and McWhirter, 2023). During the early stages of growth, organisms and ecosystems maximize energy production (Sabater, 2022). However, genetic diversity—or population entropy—increases as populations grow and mutations accumulate. Entropy production decreases as a system moves towards equilibrium. In other words, as organisms and ecosystems evolve to dissipate energy efficiently, it often increases genetic diversity or population entropy.

According to Prigogine's minimum entropy production theory, in a stationary state, the production of entropy inside a thermodynamic system with constant external parameters is minimal and constant. Thus, because natural selection favors minimizing entropy production rates (Trenchard and Perc, 2016), organisms that produce entropy at higher rates are disadvantaged. Therefore, based on the context, metabolic processes can maximize or minimize entropy production (Sabater, 2022).

In biological systems, population entropy quantifies the variety of possible configurations within a system. Gibbs entropy—a logarithmic measure of probability-weighted diversity captures species as unequal microstates (Leinster and Meckes, 2016).

where S is the entropy,

is the Boltzmann constant, and

is the current state of the system [11].

Significant genetic changes and innovation often emerge during low-entropy, small population phases. Conversely, in high-entropy, high-population-density equilibrium states, most mutations remain latent but contribute to stabilizing the organism's evolutionary potential. This potential can be modeled as a function of internal energy, described by the equations:

where U is internal energy, E is solar energy input, T is temperature, S is entropy,

is the Boltzmann constant,

Ω is the structural complexity of the ecosystem. On the right side of the equation, the first term is the change in disorder, akin to social temperature, the second term is organizational complexity, and the third is internal energy.

The evolutionary cycle can be conceptualized as a learning process where species and their members adjust their probability distributions based on their ability to exploit environmental resources. The Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence

, or relative entropy, measures the deviation between a species' probability distribution at a given time and its equilibrium distribution [12]:

p(x) ≥ 0, q(x) > 0 = probability distribution of species x, where

p(x) = probability distribution of species x at time 0,

q(x) = probability distribution of species x at high entropy equilibrium.

where quantifies change and is KL divergence. The species distribution stabilizes at the high entropy phase; when p=q, the species probability distribution no longer changes, indicating high entropy. Throughout the cycle, species that are better adapted increasingly dominate the environment. High reproductive rates and efficient resource utilization enable these species to influence the ecosystem through higher population densities. This dominance, driven by specialized adaptations, reflects the competitive dynamics of evolutionary processes and the role of entropy in shaping ecological and genetic landscapes.

3. The Reversed Carnot Cycle as an Evolutionary Model

The balance of nutrients, wastes, air, energy, and other ecosystem resources fluctuates over time, driving biological and ecological dynamics (

Table 2). High resource density fosters cooperation and experimentation, enhancing reproduction and survival rates (Arlettaz et al., 2017; Connelly et al., 2017; Katsnelson et al., 2018; Liao et al., 2019). However, periods of relative stasis in ecosystems are often disrupted by rapid morphological or structural changes (Katsnelson et al., 2019; Lowery and Fraass, 2019; Rosenberg, 2022) or by mass extinction events that reshape the biosphere (Bakhtin et al., 2020).

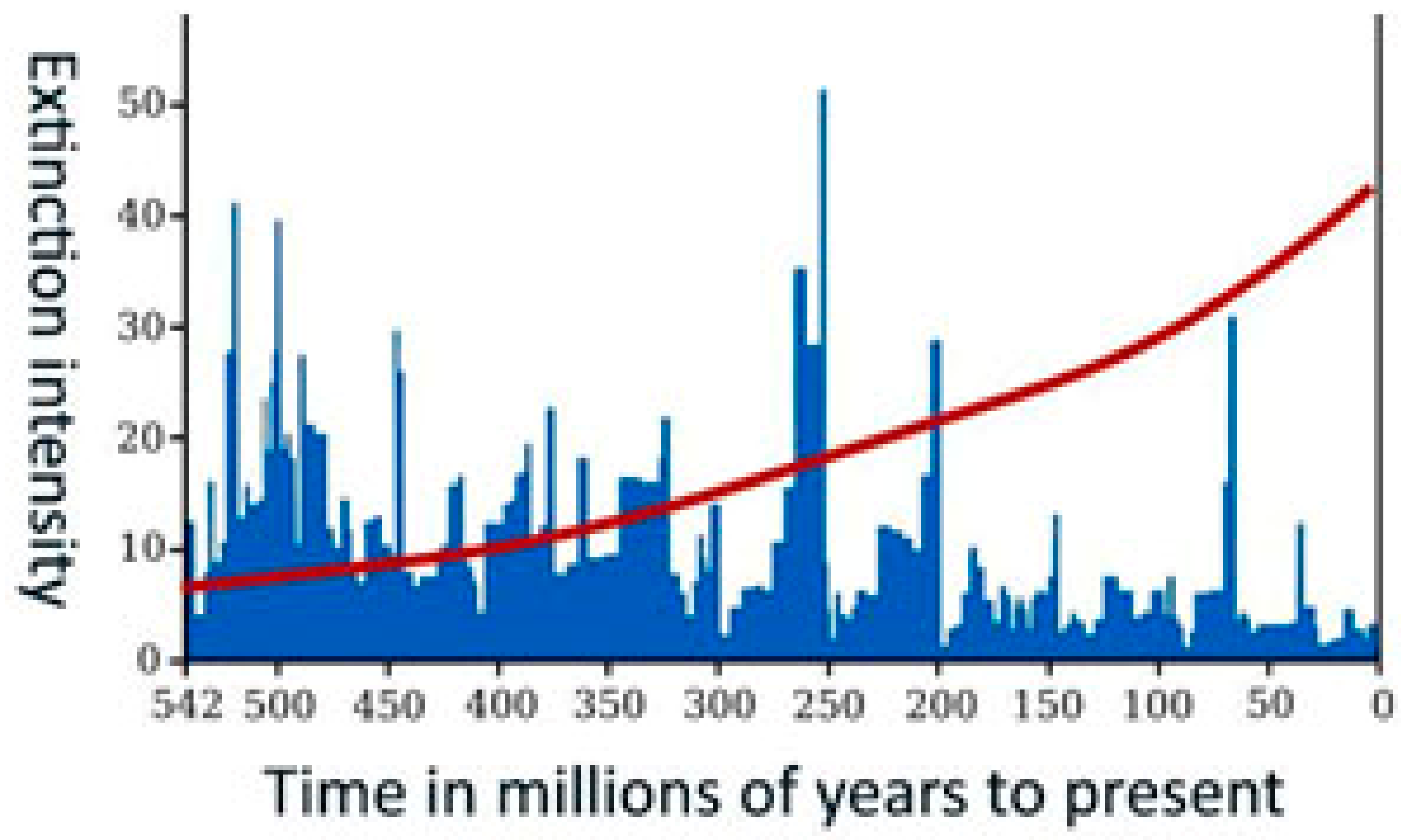

Mass extinctions partition geological time into eons, eras, and periods, each characterized by distinct genetic and morphological complexities (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). Extinction events act as "erasure phases," selectively eliminating non-adaptive taxa while the evolutionary innovations of previous cycles in the genetic material of surviving species (Crokidakis, 2017; Sundstrom and Allen, 2019; Wong, 2020). The organisms that can survive and thrive under changing conditions (Bush et al., 1977; Wagner, 2020) give rise to a new, more complex biosphere (Lehman and Miikkulainen, 2015).

Genetic material serves as a temporal archive of evolutionary history and potential, transcending the spatial confines of ecosystems. In contrast, ecosystems embody intricate spatial organizations distributed into environmental niches (Menendez, 2021). While natural selection reduces population entropy by eliminating maladaptive traits, genetic complexity remains resilient during extinction events, reinforcing its temporal nature (Thompson and Galitski, 2012). The duality of these contrasting characteristics—spatial in ecosystems and temporal in genetic material—establishes their orthogonality (

Figure 1,

Table 1).

An "ideal" evolutionary cycle can model evolutionary dynamics. Suppose we ignore other energy sources and matter exchange with its external environment. In that case, Earth functions as a closed system, receiving energy through solar radiation from outer space (Landau et al., 1960; González and Ovalle, 2021). Photosynthesis, which converts solar energy into chemical bonds, is a primary driver of biological complexity. For simplicity, energy contributions from tides, planetary winds, geothermal sources, and fossil fuel formation during the Mesozoic and Cenozoic eras are excluded from this model. Our analysis also ignores gravitational disturbances, all planetary interactions in the Solar system, and galactic radiation.

The reversed Carnot cycle, an idealized thermodynamic cycle, provides a framework for modeling biological evolution. In this theoretical construct, net entropy production approaches zero, and the cycle phases repeat precisely. Within this framework, temperature, pressure, and volume serve as quantifiable macroscopic variables, abstracting away molecular-level details. This model represents an energy-requiring process where heat is absorbed from a low-temperature (less complexity) reservoir and transferred to a high-temperature (High complexity) reservoir.

The boundaries of their ecosystems inherently constrain populations. For instance, fish are limited to aquatic environments, and terrestrial animals are confined by geographical features and food availability. Resource availability influences ecosystem dynamics, such as population size. As populations expand, entropy production decreases as a system moves towards high entropy equilibrium; in high entropy, social temperature increases, analogous to thermodynamic heating (B-C and D-A phases). Conversely, population collapses reduce social temperature, cooling the system.

The evolutionary cycle can be divided into four distinct phases:

Adiabatic Compression (A-B): Population expansion heats the ecosystem, rapidly increasing entropy and driving exploratory behavior.

Isothermal Compression (B-C): Mass extinction removes non-adaptive species, stabilizing the system and reducing entropy production.

Adiabatic Expansion (C-D): Surviving populations recover, cooling the ecosystem as social temperature drops.

Isothermal Expansion (D-A): Population growth resumes, absorbing heat and driving further evolutionary innovation.

During the initial phase, entropy increases rapidly (p" q) as species explore new ecological niches and adapt to uncertain environments. Over time, evolutionary innovations stabilize, and uncertainty decreases, causing entropy growth (dS) to approach zero. No further macroscopic changes occur at equilibrium (p=q) (Eq 2). However, rising social temperature and pressure in high-entropy systems exert selection pressures that favor species with evolvable genomes while eliminating less adaptable ones.

The balance of entropy, genetic diversity, and resource availability shapes the evolutionary trajectory of ecosystems. By conceptualizing evolution through thermodynamic principles, we gain a deeper understanding of how ecosystems transform over time, driven by population expansion, collapse, and recovery cycles. The orthogonality of ecosystems' spatial organization and genetic material's temporal resilience underscores the evolutionary process's intricate interplay between stability and adaptability.

1(C-D) Small populations form low entropy, which allows phenotypic plasticity and the evolution of new functions.

2(D-A) Population expansion gives rise to food chains.

3(A-B) Overpopulation stresses ecosystems, forming high entropy and allowing horizontal gene transfer.

4(B-C) Environmental shocks precipitate extinction, mainly affecting species with inflexible genomes.

4. Discussion of Evolutionary Phases

4.1. Phase 1 (C-D). Start of a New Cycle

The separation evident in the fossil record highlights a profound truth: mass extinctions coincide with disruptions in the energy flow through dissipative networks, leading to interruptions in ecosystem stability. These extinction events act as "clean slates," eliminating outdated species and assembling beneficial mutations from prior cycles into novel biological innovations (Erwin, 2015; Kirchner and Weil, 2000; LaBar and Adami, 2017). At the start of these cycles, characterized by low entropy and low social temperature, highly uncertain value estimates allow for substantial learning and exploration (Levin, 2021). In such environments, organisms that capture energy faster gain a competitive advantage. This principle also explains the thermodynamics underlying the rapid proliferation of cancer cells (Hall and McWhirter, 2023).

U is the internal energy, and S is the entropy of the ecosystem [14].

Characteristics of the first phase of evolution (

Figure 3).

- ), and low and high entropy ( The evolutionary innovations in the genetic material allow the cycle to repeat with higher genetic and morphological complexity.

Mass extinctions act as heat rejection phases in evolutionary cycles, creating population vacuums that open ecological niches. In these vacuums, resources become abundant, and the reduced social temperature enables energetically frugal behaviors (Lee, Malik et al., 2018). Organisms in this phase evolve rapidly, aided by geographic isolation, facilitating co-adapted alleles at multiple unlinked loci (Waters and McCulloch, 2021). Initial mutations often potentiate subsequent changes, leading to complex traits. For example, reassembling ancient alleles has driven the evolution of nervous systems, thermoregulation, and other pivotal adaptations (Soslau, 2020; Burtsev, Anokhin et al., 2022).

Parallel evolution demonstrates how similar environmental pressures drive repeated adaptations across diverse taxa. Examples include stickleback fish, cichlid fishes, and Heliconius butterflies, where repeated ecological divergence occurs at the same loci (Van Belleghem, Vangestel et al., 2018). Additionally, phenotypic plasticity allows organisms to adapt to novel environments, often resulting in gene reuse or new traits occupying unexplored morphospaces (Levin, 2021; Zhang, Reifová et al., 2021).

Gene duplication further enhances evolvability by creating genetic redundancies that allow innovation (Magadum, Banerjee et al., 2013; Katsnelson, Wolf et al., 2019). Processes like exaptation and the recruitment of mobile genetic elements also contribute to functional complexity by shifting traits to new roles or generating entirely new functions (Andersson et al., 2015; Xia et al., 2021).

Computer simulations strongly support the concept of plasticity-led evolution (Levis and Pfennig, Rago, Kouvaris et al., 2019; Levis and Pfennig, 2020; Brun-Usan et al., 2021; Burtsev et al., 2022; Ng and Kinjo, 2022). During periods of rapid evolutionary change, such as the Ediacaran diversity increase (635 to around 580–550 million years ago) (Knoll et al., 2006) or the emergence of a wide array of complex life forms during the Cambrian explosion, adaptive plasticity was crucial for survival in the dynamic environments.

Environmental Changes and Evolutionary Innovations: Environmental changes often drive evolutionary innovations. The structure and properties of genotype-to-phenotype maps enable quantitative comparisons of genetic complexity (Thompson and Galitski, 2012), such as compartmentalization in eukaryotic organisms. Adaptations to novel niches can lead to extreme phenotypic changes, speciation, or other breakthroughs [15-18]. Viral evolution, such as SARS-CoV-2's rapid adaptation in the early stages of the pandemic, illustrates how significant environmental shifts can induce rapid trait evolution (Ghanchi et al., 2021; Santoni et al., 2022).

Resource competition fosters diversification in structured environments, as demonstrated in long-term bacterial evolution experiments (Hibbing et al., 2010). However, long-term single-cell experiments indicate that cells only form simple aggregates and cannot develop organizational complexity without genetic interventions (Márquez-Zacarías et al., 2021; Daane et al., 2021).

- 2.

Free Energy and Evolution: Free energy, as defined thermodynamically by von Helmholtz (1888), represents the maximum work a system can perform at a constant volume. In evolutionary terms, social free energy (F=E−TS) quantifies the potential for complexity and innovation within ecosystems. Higher free energy, indicative of low entropy and low social temperature, provides fertile ground for evolutionary breakthroughs (Stepanić, 2004; Bush and Pruss, 2013).

- 3.

Gene Pool and Evolutionary Patterns: The gene pool is a repository of evolutionary potential, enabling the assembly of traits with statistically predictable outcomes (Varney et al., 2024). For instance, convergent evolution produces similar traits across species adapting to analogous environments, while parallel evolution reflects the repeated use of similar genetic pathways (Marques et al., 2022; Waters and McCulloch, 2021). These patterns illustrate that evolution is not a random process but a continuous exploration of pathways to greater complexity.

4.2. Phase 2 (D-A). Expansion

In the second phase of the evolutionary cycle, rapid population growth expands ecosystems, fills ecological niches, and establishes efficient food chains that process and recycle nutrients, waste, air, energy, and other resources (Kingsbury and Hong, 2020). Nutrient recycling through symbiotic relationships and predator-prey dynamics creates equilibrium points characterized by interdependence, dynamic stability, and ecological fitness (Koonin, 2016; Good et al., 2017; Vahdati et al., 2017). For example, predator and prey populations oscillate around a specific equilibrium, maintaining ecosystem stability.

While LTEE demonstrates a consistent and predictable mutation rate (Cooper and Lenski, 2000), the evolutionary changes resulting from mutations are relatively minor (Cohen and Marron, 2020; Jennings et al., 2020). Although free energy propels the system toward high-entropy equilibrium, the continually shifting species distribution (p) hides the system's precise evolutionary trajectory. The KL divergence quantifies the probabilistic distance between the current species distribution p and the high-entropy equilibrium state q, providing a mathematical framework for assessing evolutionary progress.

The population number

changes as a function of its fitness.

where

is the fitness of population

The prospect of the ith species is given by the difference in the fitness of the i-th type and the mean population fitness.

where <F> is the mean fitness at equilibrium.

Meaningful mutation steps from the origin (p) form the system's state as the number of microstates (divergence) increases. For example, larger dinosaurs with more diverse feeding habits began to gain prominence in the late Triassic period (between 237 million and 201 million years ago), when increasing humidity climate led to vegetation changes. Dinosaurs' ability to adapt to this climate and diet changes increased their ecosystem dominance (Qvarnström et al., 2024).

4.3. Phase 3 (A-B). Overpopulation

At the start of the period (T=0), the survivors have an equal opportunity at evolution. As the system evolves through a Markov process, the distribution (x) reaches equilibrium.

where

is the distribution at time T.

Learning rates decline as the evolutionary cycle progresses with increasing certainty and specialization (Levin, 2021). Resource competition is critical to population dynamics and evolutionary adaptation when resources are limited. Intense competition introduces significant selective pressures (Harris et al., 2010; Nijhout et al., 2017), adversely impacting well-being (Hoek et al., 2016; Gorban et al., 2021), disrupting social cohesion and cooperation (Anteneodo and Crokidakis, 2017; Sakaue et al., 2017; Cuthill et al., 2020; Ronco et al., 2021).

High population density intensifies crowding and aggression-related stress (Huang et al., 2021; Peacor and Pfister, 2006; Warne et al., 2013), which enhances "social temperature" (Eq. 3). Competition outcomes are shaped by key traits, such as the minimum resource level a population requires for positive growth (Miller et al., 2005). However, resource competition theory shows that two species relying on identical resources cannot coexist indefinitely within the same habitat. When mutations unlock new traits, these traits can evolve, often setting the stage for adaptive change. For instance, the evolution of the Cit+ function in bacteria required potentiating mutations, illustrating the layered nature of evolutionary progress (Blount et al., 2008; Blount et al., 2012).

Fluctuations at the microstate level within the gene pool (Schrödinger, 1946; Jeffery et al., 2019) influence genetic dispersal (LaBar and Adami, 2017; Sailer and Harms, 2017). Despite the stability of higher-level structures, environmental noise, chemical variability, and error-prone polymerases introduce diverse adaptive phenotypes (Ronco, Matschiner et al., 2021). Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) and mobile genetic elements, such as transposons, are vital in spreading genetic material (Van Etten and Bhattacharya, 2020). This process drives the development of new functions, morphologies, and even species (Sailer and Harms, 2017; Woods et al., 2020; Suh, 2021), with practical implications such as the need for annual flu vaccines and the development of new antibiotics. Entropic effects push cryptic genetic variations into otherwise inaccessible regions of the adaptive landscape (Vahdati et al., 2017; Zheng et al., 2019), introducing novel, silent sections of the genome [19,20].

Transposable elements (TEs) are highly dynamic genome components that are major sources of genetic novelty through recombination. For example, TEs inserted into mosquito genomes can transfer to other species via filarial worms (de Melo and Wallau, 2020). Documented cases of HGT from parasites to hosts, such as the acquisition of the antifreeze protein gene in herring (Graham and Davies, 2021), highlight how these processes can confer adaptive advantages by enhancing metabolic pathways (Van Etten and Bhattacharya, 2020). Viruses also facilitate genetic transfer by integrating material into host genomes—up to 8% of the human genome comprises remnants of ancient retroviral infections (Burn et al., 2022).

High population densities enhance specialization, commensalism, mutualism, and parasitism, which optimize energy use within the system. Secondary simplifications, such as reducing molecular and cellular structures, commonly occur in eukaryotic lineages and endoparasites (O'Malley et al., 2016). Paradoxically, these local reductions in complexity often support global increases in systemic complexity (Livnat, 2017), aligning with the broader evolutionary tendency.

4.4. Phase 4 (B-C). Extinction

In closed environments, entropy production typically declines over time as resources are consumed and dissipated. As ecosystems approach population growth limits, they transition from low-entropy (q) to high-entropy (p). Overpopulation disrupts the delicate balance between predators, prey, producers, and consumers. Environmental degradation and ecosystem destruction further strain the system, making it increasingly sensitive to external disturbances and extinction events. The dynamic restructuring of ecosystems—characterized by constant changes in species composition, spatial relationships, and ecological niches (Watt, 1947)—drives both radiations and extinctions (Lynch and Conery, 2003; Fan et al., 2020; Cuthill, Guttenberg et al., 2020). However, extinctions are often linked to the destruction of ecospace (Lehman and Miikkulainen, 2015) and do not always coincide with mass radiations (Lynch and Conery, 2003; Fan et al., 2020). Thus, the high-entropy phase of intensified selection pressure aligns with classic Darwinian principles, where survival hinges on adaptability (Skene, 2020).

While neutral mutations generally do not impact fitness, selection pressure reduces the likelihood of fixation for deleterious mutations (LaBar and Adami, 2017; Bothe et al., 2024). The relationship between mutation frequency and population size is complex and influenced by competition, which creates stochastic evolutionary patterns (Vahdati et al., 2017; Cui and Yuan, 2018; McAvoy and Allen, 2021). These patterns contribute to evolution's statistical and often unpredictable nature (Sailer and Harms, 2017; Watt, 1947). Species with traits ideally suited to their environment, the "ideal phenotype," and those with lower genetic diversity are particularly vulnerable to environmental fluctuations (Ørsted et al., 2019; Boggs and Gross, 2021). While dense populations and limited resources favor specialists over generalists, specialization often increases extinction risk during environmental upheavals (Webber et al., 2024). For example, highly specialized dinosaurs were eradicated during the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event, while more adaptable mammals and birds survived.

Repeated environmental shocks compress ecological niches, disproportionately affecting vulnerable organisms (Dakos et al., 2019). Such shocks lead to significant declines in species fitness (Boggs and Gross, 2021; Parry, 2021) and population sizes before major extinction events (Chiarenza et al., 2019; Dakos et al., 2019; Schmökel et al., 2023). For instance, the Siberian Traps' volcanic activity and concurrent volcanism in South China likely weakened ecological resilience well before the Permian mass extinction (Shen, Ramezani et al., 2019). Similarly, inbreeding in dwindling populations of saber-toothed cats and wolves likely precipitated their extinction (Barnosky et al., 2011). Even without catastrophic events, habitat loss and environmental degradation today have driven unprecedented extinction rates despite relatively stable genetic mutation rates.

During the middle of the evolutionary cycle (Phases 2-3), species best adapted to their environment enjoy survival advantages. However, these advantages diminish under dramatic environmental shifts, leading to the extinction of previously dominant species. Ultimately, systems capable of adjusting their energy utilization are more likely to survive, while those unable face higher risks of nonrandom extinction (Chaisson, 2011; Chaisson, 2014).

5. Discussion

In the context of the second law of thermodynamics, particularly entropy production, Darwinian evolution raises fascinating questions about how living systems maintain order and complexity despite the natural tendency toward disorder. This discussion highlights the roles of energy flow, environmental constraints, and self-organizing processes in shaping evolutionary trajectories. Potentiation—the evolution of genetic backgrounds that enable the organization and refinement of new functions—demonstrates how entropic effects contribute to developing complex structures, organelles, and organisms.

Earth's ecosystem forms closed thermodynamic cycles with limited resources. Genetic material is a stable "temporal field," preserving complexity across generations. This stability ensures that complexity remains constant or increases within the limits of reversible processes. Thermodynamic principles can also distinguish between ordered (low entropy) and disordered (high entropy) phases of evolutionary cycles (

Table 3).

Alfred Lotka argued that organisms capable of capturing and utilizing more energy than their competitors gain a selective advantage (Hall and McWhirter, 2021). Formalized by MPP, abundant energy supply benefits systems capturing and using more energy than their competitors (Fry, 1995; Boltzmann, 1886). Despite abundant energy supply, the beginning of the evolutionary cycle represents high uncertainty, which drives morphological and genetic exploration (Levin, 2021). These far-from-equilibrium conditions can promote the emergence of rapidly adapting pathogens, viruses (e.g., COVID-19), and cancer cells.

In contrast to the MPP, Prigogine's theorem posits that evolution involves a continuous search for states with lower entropy production (

Table 3). Toward the end of the cycle, as resources dwindle, organisms with efficient metabolic pathways that minimize entropy production are favored (Trenchard and Perc, 2016). This transition from maximizing to minimizing energy dissipation highlights the dual thermodynamic and biological bases of natural selection.

Biological organisms and ecosystems evolve to dissipate energy more efficiently, increasing entropy at the system level. As ecosystems undergo organizational evolution, they enhance their capacity to absorb entropy from their surroundings and dissipate free energy. This process divides evolutionary cycles into four distinct phases, each characterized by unique levels of entropy, population numbers, and social temperature.

Phase One: Species are dispersed into isolated ecological niches. Analogous to particles within a minimal kinetic energy liquid phase, organisms cooperate to explore and exploit their environments (Erwin, 2015).

Phase Two and Three: Population growth intensifies competition, driving the emergence of optimal genotypes. Darwinian natural selection becomes especially crucial in stressed ecosystems.

Phase Four: Although the high-entropy system favors efficient energy utilization, mass extinction events target highly specialized evolutionary dead ends. The survivor species preserve genetic and morphological innovations of the cycle.

Extinction events play a critical role in reshaping ecosystems, acting as catalysts for transformation (Boggs and Gross, 2021; Parry, 2021). Periodic compression (high entropy, energy-poor phases) and expansion (low entropy, energy-rich phases) of living spaces resemble oscillatory pumps, continuously reshaping fitness landscapes and offering new opportunities for evolution. While individual species may evolve less efficient energy use, ecosystems become increasingly effective at retaining and redistributing energy (Vermeij, 2019).

In early evolutionary history, random mutations dominated, particularly before the protective ozone layer and advanced gene repair mechanisms emerged. This era of arbitrary and inefficient entropy use eventually gave rise to more purposeful processes, culminating in the evolution of intellect. Today, evolution operates subtly, driven primarily by epigenetic regulation and genetic duplication. These mechanisms have confined Darwinian "survival of the fittest" dynamics to high-entropy phases of the evolutionary cycle.

6. Conclusions and Future Directions

We treated the ecosystem as a physical, thermodynamic system. Major extinctions usher in a low entropy, non-equilibrium state, which, spontaneously, through the interaction of its members, moves toward high entropy equilibrium. At the beginning of the cycle (low thermodynamic temperature), individuals with high energy use flourish (maximum power principle); however, low entropy production and highly specialized species do better at equilibrium. However, these highly specialized species are the most vulnerable to extinction. The survivors of major extinction carry the cycle's evolutionary innovations, reformulating on a higher complexity. Therefore, the genetic material, representing the individual and species' history and future potential, is immune to extinction. It can be considered an invisible factor in evolution, a stable temporal field.

Computer simulations, including supercomputer analyses of fossil records and long-term evolutionary processes, hold the potential to validate and refine this model. Our model can offer new tools for creating better crop yields and protecting natural habitats. Additionally, our hypothesis offers a thermodynamic lens through which to understand and model the evolution of intelligent systems, such as AGI.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, ED; methodology, ED; software, validation, ED, and formal analysis; ED, investigation, and original draft preparation, ED; writing—review and editing; ED and RR; funding acquisition and reference formatting. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work had received no funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study did not require ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data was created during the creation of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Note

-

1

Inverse temperature beta or coldness is the reciprocal of the thermodynamic temperature of a system.

References

- Escobar, F.B.; Velasco, C.; Motoki, K.; Byrne, D.V.; Wang, Q.J. The temperature of emotions. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0252408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.F. Social synergetics, social physics and research of fundamental laws in social complex systems. arXiv:0911. 1155 2009.

- Deli, E.; Peters, J.; Kisvárday, Z. The thermodynamics of cognition: A mathematical treatment. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 784–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’neill, J.; Schoth, A. The Mental Maxwell Relations: A Thermodynamic Allegory for Higher Brain Functions. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 827888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anteneodo, C.; Crokidakis, N. Symmetry breaking by heating in a continuous opinion model. Phys. Rev. E 2017, 95, 042308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tkadlec, J.; Pavlogiannis, A.; Chatterjee, K.; Nowak, M.A. Limits on amplifiers of natural selection under death-Birth updating. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2020, 16, e1007494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crokidakis, N. Non-Equilibrium Phase Transitions Induced by Social Temperature In Kinetic Exchange Opinion Models on Regular Lattices. Rep. Adv. Phys. Sci. 2017, 01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, A.J.; Plotkin, J.B. From extortion to generosity, evolution in the iterated prisonerΓÇÖs dilemma. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2013, 110, 15348–15353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sella, G.; Hirsh, A.E. The application of statistical physics to evolutionary biology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2005, 102, 9541–9546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boojari, M.A. Investigating the Evolution and Development of Biological Systems from the Perspective of Thermo-Kinetics and Systems Theory. Orig. Life Evol. Biospheres 2020, 50, 121–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boltzmann, L. Vorlesungen über gastheorie; JA Barth (A. Meiner): 1910; Vol. 1.

- Csiszar, I. $I$-Divergence Geometry of Probability Distributions and Minimization Problems. Ann. Probab. 1975, 3, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raup, D.M.; Sepkoski Jr, J.J. Mass extinctions in the marine fossil record. Science 1982, 215, 1501–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanchurin, V.; Wolf, Y.I.; Katsnelson, M.I.; Koonin, E.V. Toward a theory of evolution as multilevel learning. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2022, 119, e2120037119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brun-Usan, M.; Rago, A.; Thies, C.; Uller, T.; Watson, R.A. Development and selective grain make plasticity 'take the lead' in adaptive evolution. BMC Evol. Biol. 2021, 21, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burtsev, M.; Anokhin, K.; Bateson, P. Plasticity facilitates rapid evolution. bioRxiv 2022, 2022–2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, E.T.H.; Kinjo, A.R. Computational modelling of plasticity-led evolution. Biophys. Rev. 2022, 14, 1359–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentz, J.T.; Márquez-Zacarías, P.; Bozdag, G.O.; Burnetti, A.; Yunker, P.J.; Libby, E.; Ratcliff, W.C. Ecological Advantages and Evolutionary Limitations of Aggregative Multicellular Development. Curr. Biol. 2020, 30, 4155–4164.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, L.A.; Davies, P.L. Horizontal Gene Transfer in Vertebrates: A Fishy Tale. Trends Genet. 2021, 37, 501–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woods, L.C.; Gorrell, R.J.; Taylor, F.; Connallon, T.; Kwok, T.; McDonald, M.J. Horizontal gene transfer potentiates adaptation by reducing selective constraints on the spread of genetic variation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020, 117, 26868–26875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).