1. Biologists on Entropy

Despite Schrödinger’s efforts, most biologists ignore entropy because they see little or no connection between Darwinian evolution and the 2nd law of thermodynamics. NASA astrobiologists, however, are looking for life beyond the Earth, so they need a definition of life. Here is NASA’s: Life is a “self-sustaining chemical system capable of Darwinian evolution” (Benner 2010). The word “self” is problematic since there is no such thing as a “self-sustaining chemical system”. Sustained chemical reactions take place when the Gibbs free energy is negative, ΔG(t) < 0, and this sustained negativity can only come from sources of free energy outside the life form.

Life’s openness allows free energy in, but neither a closed-self nor an open-self can supply a continuous source of free energy. So “self-sustaining” is an oxymoron. Also, since the Gibbs free energy G = U – TS, and S is entropy, entropy must play a fundamental role in life just as Schrödinger (1948) suggested.

Understanding the relationship between entropy and life involves understanding how non-life became life – how chemistry became biology. This transition does not involve the improvement or the refinement of our definitions of life. It involves their deconstruction. In other words, as we trace the evolution of life back through time and try to find its abiotic purely chemical origins, we should expect our definitions of life to become more and more inappropriate. So, we will necessarily have to deconstruct the current apparent boundary between non-life and life to understand the transition from chemistry to biology.

What is important in the origin of life field is understanding the transitions that led from chemistry to biology. So far, I have not seen that efforts to define life have contributed at all to that understanding. (Szostak 2012).

More specifically, what is important is understanding the role of entropy in the transitions that led from chemistry to biology. Entropy and entropy production play a more important role in (i) the origin of life and (ii) Darwinian evolution than is generally recognized by biologists. In most authoritative books on evolution, entropy is not even mentioned. There is no entry for “entropy” in the indexes of The Origins of Life (Smith & Szathmary 1999), The Structure of Evolutionary Theory (Gould 2002) or Evolution: The first Four Billion Years (Ruse & Travis 2009). The definition of entropy in What is Evolution (Mayr 2001) is a crude afterthought:

Entropy The degradation of matter and energy in the universe to an ultimate state of inert uniformity. Entropy can be reached only in a closed system.

Mayr is confusing entropy with three other concepts: (1) the production of entropy (2) the heat death of the universe and (3) the maximum entropy of a closed system. One of the main goals of this paper is to clarify the differences between these concepts and relate them to Darwinian evolution.

Trying to understand the origin and evolution of life without understanding its fundamental dependence on the second law of thermodynamics and entropy production is like trying to understand the origin and development of the United States of America without understanding the role of England or George Washington. It’s blinkered and futile. Yet, it persists. We need to do a better job of convincing our colleagues of the fundamental constructive role entropy plays in the origin of life and Darwinian evolution.

Many authors still subscribe to the idea that there is some kind opposition between entropy and evolution. Darwin’s Dangerous Ideas: Evolution and the Meanings of Life (Dennett 1995) is an otherwise insightful description of our modern understanding of Darwinism and its importance, he writes:

According to the Second Law, the universe is unwinding out of a more ordered state into the ultimately disordered state known as the heat death of the universe. What then, are living things? They are things that defy this crumbling into dust, at least for a while, by not being isolated – by taking in from their environment the wherewithal to keep life and limb together…Not just individual organisms, but the whole progress of evolution that creates them, thus, can be seen as fundamental physical phenomena running contrary to the large trend of cosmic time…It is not impossible to oppose the trend of the Second Law, but it is costly. (Dennett 1996, p 68-69)

Here is another expression of the supposed opposition between life and entropy:

…to stay alive we need to continually eat so as to combat the inevitable, destructive forces of entropy production. Entropy kills. (West 2017, p 14-15).

The relationship between the 2nd law and Darwinian evolution is not “costly” as Dennett would have it. There is no real opposition between life and entropy, but incomplete descriptions of life invoke an apparent opposition between life and entropy. This apparent opposition stems from a long tradition of separating life from non-life, biotic from abiotic and viewing life forms as beings independent and more important than the dead physical environment. Thus, when it comes time to tally up the entropy budget, the focus is on tallying up the low entropy inside the life form, not its overcompensation by the higher entropy exported to the environment. The apparent opposition between life and entropy comes from ignoring the fact that life forms are embedded in, depend on, and coevolved with, the biosphere and Earth’s environment. If we want to understand what is going on, we need to keep track of the total entropy. By explaining this clearly, Mayr redeems himself:

It is sometimes claimed that evolution, by producing order, is in conflict with the “law of entropy” of physics, according to which evolutionary change should produce an increase of disorder. Actually, there is no conflict, because the law of entropy is valid only for closed systems, whereas the evolution of a species of organisms takes place in an open system in which organisms can reduce entropy at the expense of the environment and the sun supplies a continuing input of energy. Mayr (2001).

Not only does the evolution of life not oppose the 2nd law, life has come into existence because of entropy. And while it exists, life enhances the 2nd law since the existence of life increases entropy production in the universe. Some authors want to finesse a compromise between life and entropy:

…Life violates the spirit but not the letter of the second law. (Brown 1999, p 74).

The simplest metaphor for the role of life in the universe is a refrigerator. A refrigerator runs on free energy. You have to plug it in. The low entropy inside a refrigerator comes at the expense of increasing the entropy outside the refrigerator. This is easily tested. On a hot summer day in a sealed room, try to cool the room by opening the refrigerator door.

Make sure the heat from the back of the refrigerator does not leave the room through some vent. The more refrigerators you turn on, the hotter the room gets and the more entropy is produced. And the colder you make the refrigerators, the more watts they need, the hotter the room gets and the more entropy they produce.

2. What Is the Connection Between Entropy and Biology? Going Beyond the Second Law

Rudolf Clausius (1865) coined the word “entropy” and the second law of thermodynamics: “The entropy of the universe tends to a maximum” or dS ≥ 0. The 2nd law is the only law of physics that has a “≥” instead of a “=”. The passage of time – even the definition of time – has been attributed to this “≥” and the irreversibility it represents. Does the second law need extending? If so, how can we extend it? The phrase “tends to a maximum” begs the question: How strong is this tendency? How quickly does entropy tend to a maximum? What controls the rate of entropy increase dS/dt? Researchers have discussed the connection between entropy and biology (e.g. Prigogine & Stengers 1984, Brooks & Wiley 1988, Weber et al 1990). And over the past few decades a group of researchers has explored the landscape beyond the second law (e.g. Kleidon & Lorenz 2005, Dewar 2005, Martyshev & Seleznev 2006, Dewar 2009, Kleidon 2010a,b, Dewar et al 2014a).

Is there anything useful and fundamental that we can say about the rate of entropy increase?

In other words, can we go beyond Clausius’ second law:

(2A) The entropy of the universe tends to a maximum. (i.e. dS/dt ≥ 0 )

and hypothesize instead that:

(2B) The entropy production dS/dt of the universe tends to a maximum (i.e. d2S/dt2 ≥ 0).

These are distinct, independent statements. Just as there is an important distinction between position x, velocity dx/dt, and acceleration d2x/dt2, there is an equally important distinction between entropy S, entropy production dS/dt, and changes to entropy production d2S/dt2. If position x is increasing then dx/dt is positive. But that says nothing about the rate of change of dx/dt. On a bike ride to the store you can have a positive velocity dx/dt > 0, but you can go fast, then slow, then speed up and still have a positive velocity. Sometimes you push harder on the pedals and sometimes you brake. These changes in velocity are described by acceleration: d2x/dt2. Speeding up (d2x/dt2 > 0) and slowing down (d2x/dt2 < 0 ) are changes in the sign of d2x/dt2. Similarly, statement 2B above is about d2S/dt2 ≥ 0. It is distinct from statement 2A (which is the 2nd law about dS/dt ≥ 0). Statement 2B is a distinct hypothesis that goes beyond the second law. To some, statement 2B seems obvious:

In the jargon of thermodynamics, the formation of patterns in these systems [far from equilibrium dissipative systems] helps to speed up the dissipation of energy as mandated by the second law. (Hazen 2005, p 13)

In this quote, “dissipation of energy” means dS/dt > 0 and is the second law. But to “speed up the dissipation of energy” is different and is the subject of hypothesis 2B. 2B involves the second derivative d2S/dt2 not the first derivative dS/dt. An increase in entropy dS/dt > 0 is different from an increase in entropy production d2S/dt2 > 0. Thus, Hazen is assuming ideas about thermodynamics that go beyond the 2nd law. I agree with him that far from equilibrium dissipative systems (“FFEDS”, Prigogine 1978) increase dS/dt, but I disagree that this is expressed in the second law. The second law is completely silent on the second derivative of entropy. In Clausius’ description of the 2nd law, the entropy of the universe tends to a maximum, there is nothing about far from equilibrium dissipative systems (FFEDS) and specifically nothing about speeding up the dissipation of energy. The “dissipation of energy” involves dS/dt > 0 while “speeding up the dissipation of energy” involves d2S/dt2 > 0. No part of the second law is about speeding up the rate of entropy production. If going beyond the second law involves speeding up the rate of entropy production, then hypothesis 2B is a compact way to say it.

In addition, the second law dS/dt ≥ 0 says nothing about the connection between the rate of entropy production dS/dt and the steepness of the gradient, the complexity of the FFEDS or the derivative of the Gibbs free energy (except to say that in equilibrium when there are no gradients, dS/dt = 0). Similarly, 2B says nothing about the connection between the increase in the rate of entropy production d2S/dt2 > 0 and the steepness of the gradient or the complexity of the FFEDS (except that in equilibrium when there are no gradients d2S/dt2 = 0). Presumably, at equilibrium all higher derivatives of S are also zero.

There are several other problems involved with efforts to go beyond the second law.

A) Physicist often insist that the entropy of a system can only be defined in equilibrium. If the concept of entropy only makes sense in equilibrium, we can only talk about the difference of the entropy between two equilibrium states: ΔS = S2 – S1, or about near-equilibrium states (Onsager 1931ab, Dewar 2005, Kondepudi & Prigogine 2006, Ben-Naim 2019, see also Zupanovic et al 2010).

B) A diversity of mathematical notations, an acronym soup (MEP, MaxEP, MinEP, MaxEnt), and attempts to generalize to the widest range of applications, all contribute to making things complicated. See for example Dewar et al 2014b, specifically Table 1,

Figure 1.1 and their use of the dissipation function <Ω> to mathematically explore the landscape beyond the second law.

C) “Life forms don’t just obey the second law, they enhance its operation” Schneider & Sagan (2005, p xv). This agrees with Hazen above. There seems to be agreement that life forms enhance the operation of the second law. That is, biotic FFEDS make dS/dt larger than it would be without them. But trying to quantify this enhancement is a work in progress (Dewar et al 2014a, and papers in this issue of Entropy).

3. Paradigm Shift from “We-Eat-Food” to “Food-Has-Produced-Us-To-Eat-It”

There is more to the relationship between life and entropy than life not violating the 2nd law. Some researchers have argued that a paradigm shift is needed to more accurately describe the relationship between life and entropy – a paradigm shift from the conventional life-centered view of “we-eat-food” to a more objective gradient-centered view of “food-has-created-us-to-eat-it” (e.g. Schneider & Kay 1994, Schneider & Sagan 2005, Lineweaver & Egan 2008, Vallino 2014).

…gradients, when steep enough, give rise to far from equilibrium dissipative structures (e.g., galaxies, stars, black holes, hurricanes and life) which emerge spontaneously to hasten the destruction of the gradients which spawned them. This represents a paradigm shift from “we eat food” to “food has produced us to eat it. (Lineweaver & Egan 2008).

In the “we-eat-food” paradigm, food costs us something and organisms that have evolved by Darwinian evolution are fighting against the increase of entropy to stay alive. In contrast, the “food-has-created-us-to-eat-it” paradigm marginalizes the apparent opposition between Darwinian evolution and the 2nd law. Instead, it sees life (and abiotic FFEDS as well) as the dependent offspring of an entropy-driven process. Life forms and FFEDS emerge from gradients. We owe our existence to gradients. And the reason for our existence is to destroy the gradients that gave birth to us (Schneider and Sagan 2005). Abiotic FFEDS can easily be interpreted this way. Destroying their reason for being is what hurricanes are doing in the Caribbean, what convection cells are doing on the surface of the Sun and what forest fires are doing in the Pacific Northwest (destroying thermal gradients and a redox gradient).

Our existence, and the existence of far from equilibrium dissipative systems in general, (both abiotic and biotic) increase the entropy production of the universe over and above what it would be if life did not exist. This non-flattering new paradigm goes beyond the 2nd law and is an expression of hypothesis 2B above. (I call it “hypothesis 2B” because the “B” can stand for “Beyond” and because the 3rd law of thermodynamics has already been taken to define the absolute temperature scale).

In this new paradigm, life is not costly. Life forms are created by gradients to destroy those gradients and in the process produce more entropy than would be the case without them. To paraphrase Lovelock and Margulis (1974): Life exists “by and for” entropy production.

Hoffman (2012) has a slightly different idea:

Life does not exist despite the second law of thermodynamics; instead, life has evolved to take full advantage of the second law wherever it can.

This is an expression of the conventional “we-eat-food” paradigm and differs from food-has-created-us-to-eat-it. For Hoffman, life is a free agent with free will that can take advantage of a situation. For the “food-has-created-us-to-eat-it” paradigm, life is more of a puppet. It has to do what it does. To underline how fundamental a change in perspective this paradigm shift is, consider how Dyson in his well-cited article “Energy in the Universe” described the role of life in the universe:

…life may have a larger role to play then we have yet imagined. Life may succeed against all odds in molding the universe to its own purposes. (Dyson 1971, p 51)

In contrast to Dyson, I am arguing that not only may entropy succeed, entropy has already succeeded (with odds in its favour because that is what entropy is) in molding life to its own purposes.

4. Enhancement Compared to What?

FFEDS can be divided into two classes; (1) abiotic and (2) biotic. Examples of abiotic FFEDS include convection cells, hurricanes, whirlpools, lightning, stars and galactic bars. These are produced by gradients of various kinds; thermal, pressure, humidity, photochemical, electric, chemical redox and gravitational. Biotic FFEDS or life forms were produced originally as chemoautotrophs by chemical gradients, which had been produced by gravitational gradients. Life is currently powered by chemical gradients and photon-energy gradients. A hierarchy of transductions transfers power from one gradient to another (Kleidon 2010 a, b). When confined to biotic FFEDS, the hierarchy of transductions is called a trophic pyramid.

Both abiotc and biotic FFEDS are born from gradients. Both produce entropy. Despite the entropy production of abiotic FFEDS, it is problematic to say that they increase the entropy of the universe over and above what it would be in their absence. We have no idea what a universe without convection, turbulence, hurricanes, fires or stars would be like. Thus, it makes little sense to entertain such a contrafactual universe to calibrate abiotic FFEDS entropy production. And it makes little sense to say that abiotic FFEDS increase the entropy of the universe over and above what it would be in their absence.

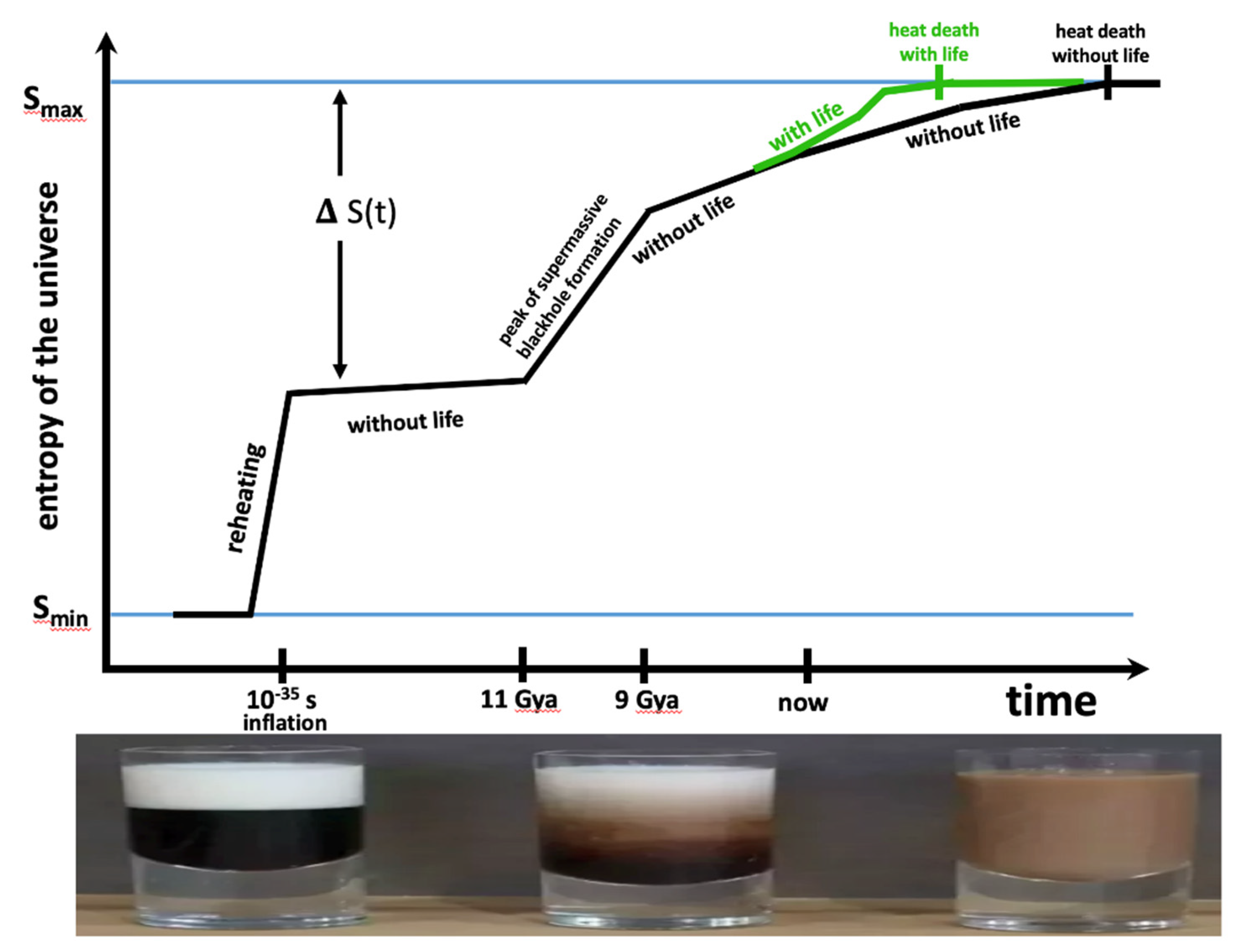

However, we can more easily imagine a universe without life – without biotic FFEDS. Thus, it does make sense to say that biotic FFEDS (microbes, humans) increase the entropy of the universe over and above what it would be in their absence. It seems less problematic to say that compared to an abiotic universe, a biotic universe will have a larger entropy, since such a universe non-obligatorily contains evolving, free-energy-tapping, entropy-producing machines who, despite their internal low entropy, contribute a net positive tally to the total entropy of the universe. This is illustrated in Figs. 3 & 4 by the difference between the black lines (without life) and the green lines (with life).

5. The Emergence and Evolution of Abiotic and Biotic FFEDS

Abiotic FFEDS emerge or develop, (some even say “evolve”, e.g. Bejan 2006, Bejan & Lorente 2011) from gradients. Some emerge rapidly like the branching patterns of a lightning bolt. Some more slowly like the turbulent whirls as cream mixes with coffee (

Figure 3). Some emerge and develop on longer time scales of days or thousands of years (hurricanes, river basins, Jupiter’s great red spot). However, unlike biotic FFEDS they do not accumulate information. They have no coded DNA. They have inertia, but no controllable stored energy. They are the result of gradients. If they “evolve” they evolve deterministically, not as a result of Darwinian evolution. For example, the relationships between hurricane formation and thermal, density, pressure and humidity gradients are the same now as they were 100 million or a billion years ago. Ditto for dust devils, convection cells on stellar surfaces and the fusion of H into He inside stars.

Biotic FFEDS are different. They store information and free energy. Their populations have differential reproduction and contain variety—the raw material that natural selection sculpts. As a result, they evolve through Darwinian evolution and accumulate adaptive coded information (Darwin 1859, Godfrey-Smith 2009). Life forms (i.e. biotic FFEDS) can be understood as catalysts that, as they evolve, lower the activation energies for their metabolic reactions (Dobovisek et al 2014, Weng 2013). Evolving catalysts increase entropy by more efficiently accessing available free energy, or by discovering ways to access new sources of free energy – free energy that eventually gets converted into entropy as heat.

6. Increasing Complexity or Increasing Entropy Production as the Direction of Evolution?

Some widely recognized large-scale biological patterns are difficult to explain within standard Darwinian evolution with its focus on the individual as the unit of selection (Gould 2002, Godfrey-Smith 2009, Wilson 2019). These include ecological successions, the increasing complexity of ecological networks, adaptive radiations after extinction events, increasing species diversity that make ecosystems more stable, pole-to-equator increase in the diversity of species and, more generally, the apparent increase of complexity.

Hypothesis 2B above (“The entropy production dS/dt of the universe tends to a maximum (i.e. d2S/dt2 ≥ 0)”) may be able to explain this wide variety of tendencies. All the ecosystem-level patterns above are associated with entropy increase and may also be associated with an increase in entropy production. Entropy production could tend to a maximum if such an increase resulted in more probable outcomes, i.e. macrostate outcomes with a larger number of pathways leading to them (Dewar et al 2014b). If an ecosystem has access to a variety of values of dS/dt, and the larger values of dS/dt produce more probable outcomes, this would suggest that an increase in entropy production would be entropically-driven. That is what 2B hypothesizes. In other words, the evolution of catalytic enzymes and the phylogenetic divergence of species, produce a variety of dS/dt values. The larger ones give more efficient access to free energy and/or access to a larger number of sources of free energy. This can be seen as a generalization of entropic drive (Branscomb & Russell 2013): entropy increases as the system moves from a macrostate-with-fewer-microstates to a macrostate-with-more-microstates. This can be reworded for a higher trophic level: an ecosystem in a macrostate-with-fewer-species-and-less-diverse-species-that-produce-less-entropy spontaneously becomes (= is entropically-driven to) a macrostate-with-more-species-and-more-diverse-species-that-produce-more-entropy.

7. Hypothesis 2B May Also Explain the Simultaneous Evolution of Increasing Complexity and Increasing Simplicity

Although complexity is difficult to define and many definitions of complexity exist (e.g. Lineweaver et al 2013) many biologists and most people think Darwinian evolution has an inbuilt direction towards increasing complexity.

Stars are the power plants that drive life’s development toward increasing complexity. (Adams, 2002, p 159).

Most people are convinced that contrary to what one would expect from the second law, the complexity of the universe is increasing. This increase in complexity is usually associated with the evolution of multicellular life forms and the other “major transitions” in the evolution of life (Smith and Szathmary 1999). Darwin, however, seems to have been non-committal about whether evolution had a direction towards increased complexity (Ruse 2013).

To many, the human brain is the most complicated thing in the universe, followed close behind by our computers, cities and social networks. “Once there were bacteria, now there is New York” (Conway Morris 2014). One problem with this view is that the complexity of some species increases while the complexity of other species decreases. For example, for every complex multicellular organism, a dozen species have evolved to become simpler and parasitic, and live off of the multicellular organism with its convenient flow of free energy. If we are counting the difference between the number of life forms that have become simpler and the number that have become more complex, the number getting simpler is easily larger. Ignoring parasites and paying more attention to the evolution of the most complex organisms has given many people the impression that complexity is, on average, increasing.

The apparently opposite directions of increased complexity vs increased simplicity, are not contradictions. They both can be explained by the unifying concept of evolution as the tendency to increase dS/dt (hypothesis 2B). The increasing variety and complexity of the beaks of Darwin’s finches gives them easier access to a wider variety of nuts. Simultaneously, the increasing variety and simplicity of parasites on these finches (tapeworms, ticks and microbiomes) gives these parasites access to a flow of free energy from which they are able to extract a larger portion of free energy from the food than the finch could have without these simpler life forms. The end result of these simultaneous changes towards complexity and simplicity is the conversion of more free energy and the increase of entropy production. In the case of evolution towards the more complex and the more simple, entropy increases (dS/dt > 0) and entropy production increases (dS2/dt2 > 0). This is the tendency described in hypothesis 2B. Thus, the evolution of ecosystems and possibly the entire biosphere (Toniazzo et al 2005) – can be understood as 2B and the tendency for entropy production to increase.

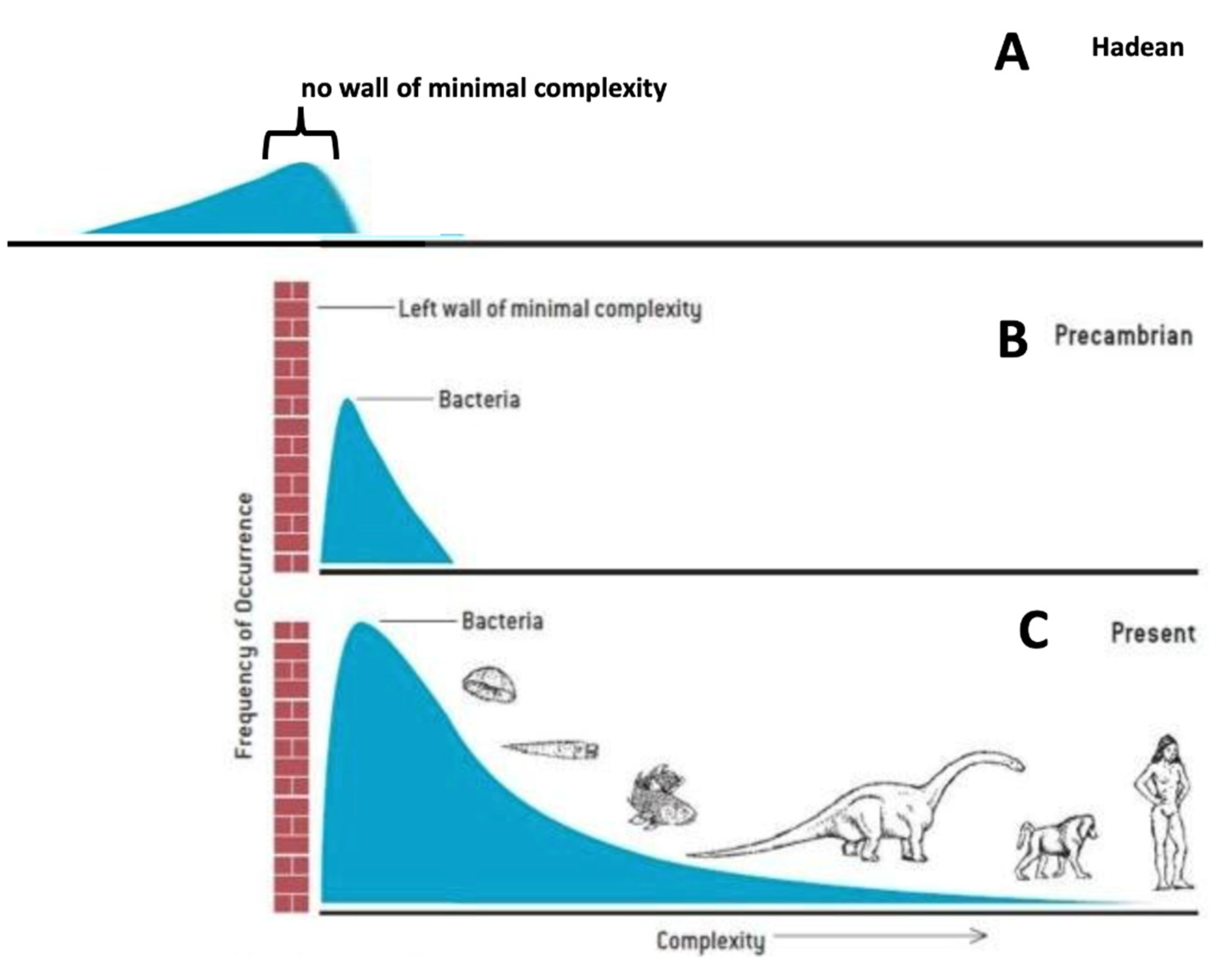

8. Gould’s Wall of Minimal Complexity

The idea that the complexity of life is increasing is a conventional – even dominant view – of how Darwinian evolution works. In an effort to push back on this idea Gould (1994) introduced the idea of a wall of minimum complexity (the red brick wall in panels B and C of

Figure 1).

For reasons related to the chemistry of life’s origin and the physics of self-organization, the first living things arose at the lower limit of life’s conceivable preservable complexity. Call this lower limit the ‘left wall’ for an architecture of complexity. Since so little space exists between the left wall and life’s initial bacterial mode in the fossil record, only one direction for future increment exists – toward treater complexity at the right. Gould 1994

Gould’s view was that such a one-sided wall left nothing else for a diversity-prone evolutionary process to do but extend to the right. This wall of minimal complexity was effectively a wall of irreversibility in the sense that early life could evolve through it going from left to right, but evolved life could not go back. This wall is a visual expression of Dollo’s law (Dollo 1893) which influenced Gould early in his career (Gould 1970).

There are several problems with this wall of minimum complexity. One is that since there are many ways of being complex (Lineweaver et al 2013), complexity should not be represented as one-dimensional (as it is in

Figure 1). One-dimensional representations of “intelligence” are similarly misleading (Gould 1981). Another problem is since we don’t know how life emerged 4 billion years ago in the Hadean, we don’t know that the emergence was irreversible. Abiotic FFEDS seem to be able to form and disappear – to become more complex and less complex with no concern for any wall of minimal irreversible complexity preventing them from from disappearing. Any one-way wall at some minimal-complexity- required-for-life, would depend on life not being able to reduce the amount of accumulated information. However, four billion years ago, when the amount of accumulated information in the earliest biotic FFEDS was small, the degree of irreversibility would also have been small. Since Dollo’s law (Dollo 1893, Gould 1970) must depend on the amount of accumulated information, the strength of any irreversibility would have been diminished in the Hadean.

Another problem. To justify the wall Gould invoked the idea that “so little space exists between the left wall and life’s initial bacterial mode”. In Gould’s world of Cambrian and post-Cambrian paleontology there may be “little space” between the wall and bacteria, but in the past few decades microbiology has filled this “little space” with a huge variety of organisms at the boundaries between life and non-life. These include a major new branch of largely symbiotic and episymbiotic bacteria (Hug et al 2016, Castelle & Banfield 2018) as well as new types of viruses: mimiviruses and mega phages (Al-Shayeb et al 2020, Lineweaver 2020, Hou et al 2023). Half of biologists think viruses are alive while the other half think they are not. Whatever they are, they are the most abundant organisms on Earth and were possibly fundamentally involved with the origin of life (Nasir & Caetano-Anolles 2015, youtube.com/watch?v=Orf_cbXyZHo&t=468s). Do we put them to the left or right of the wall of minimal complexity? And what about free-living viroids (Diener 1971)? Are McClintock’s transposons (= jumping genes) alive or not alive? “Every component of the organism is as much of an organism as every other part” (Keller 1983). Along with the Hadean RNA world (Gilbert 1986, Neveu et al 2013) there is a large unexplored and unappreciated extant RNA world (Cech 2012, Koonin & Dolja 2014).

In describing his wall, Gould writes: “Since so little space exists between the left wall and life’s initial bacterial mode in the fossil record.” But the pre-Cambrian fossil record is so sparse as to be irrelevant. Bacteria do not preserve well. We have almost no fossils of LUCA and don’t expect to find any. Our ideas about the time span between the origins of life and LUCA are speculative. However, most literature on the topic admits that LUCA was already so complicated (e.g. Weiss et al 2016, Moody et al 2024) that a substantial amount of time would have been required for the evolution of such complexity. We also need to consider pre-cellular life. Do organisms need cell walls, DNA or RNA to be on the right of the wall? Do metabolism first models live only on the left (Segre & Lancet 1999, Dyson 1999)? In the absence of a wall of minimal complexity, our entropy-production explanations for the simultaneous increase of complexity and simplicity seem more plausible. For alternative views on the apparent increase of complexity and entropy production see McShea & Brandon 2010 and Chaisson 2002.

9. Techno FFEDS

We humans learned to control fire. This gave us the ability to cook and access more free energy in a wider variety of foods (Wrangham 2009). This new free energy probably freed the energy-intensive brain from some energy constraints. Our brains got bigger and figured out how to burn hydrocarbons, make solar panels, wind mills and atomic fission reactors (Haff 2014). Soon fusion reactors may tap into the free energy of hydrogen as abiotic FFEDS (stars) began doing 13.6 billion years ago. Eventually we may extract free energy from rotating black holes via the Penrose mechanism (Penrose & Floyd 1971). These new sources of free energy may free energy-intensive silicon-based artificial intelligence (techno FFEDS) from some energy constraints. Kardashev Type I civilizations can access all the energy available on a planet, Type II can access all the energy available from its host star. Type III can access all the energy available from the hundreds of billions of stars in a galaxy (Kardashev 1964, 1997). With a much larger supply of free energy they/we will get bigger and figure out how to make anti-matter engines, build Dyson spheres and possibly whole universes.

10. The Relationship Between Entropy Production and Complexity

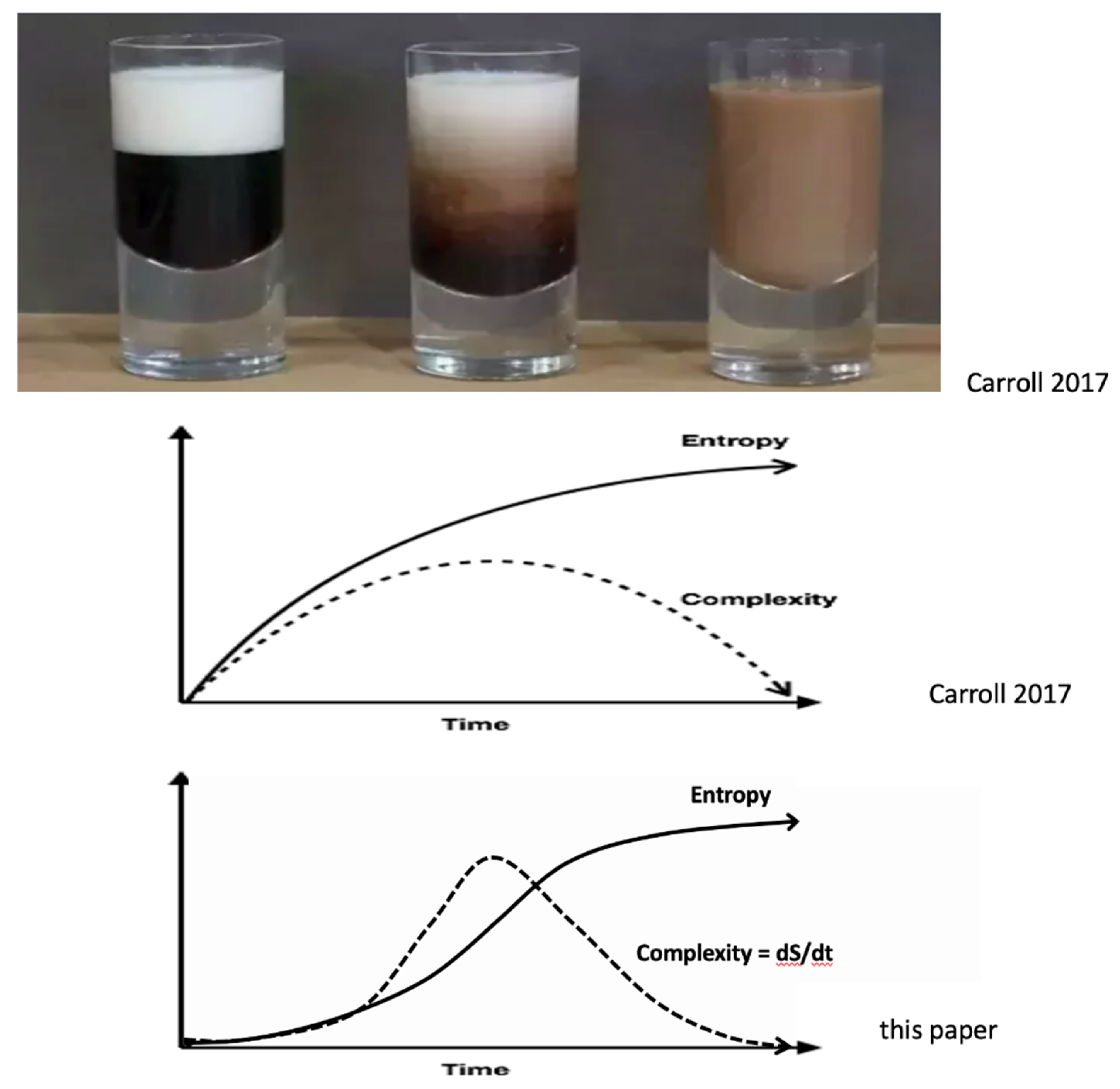

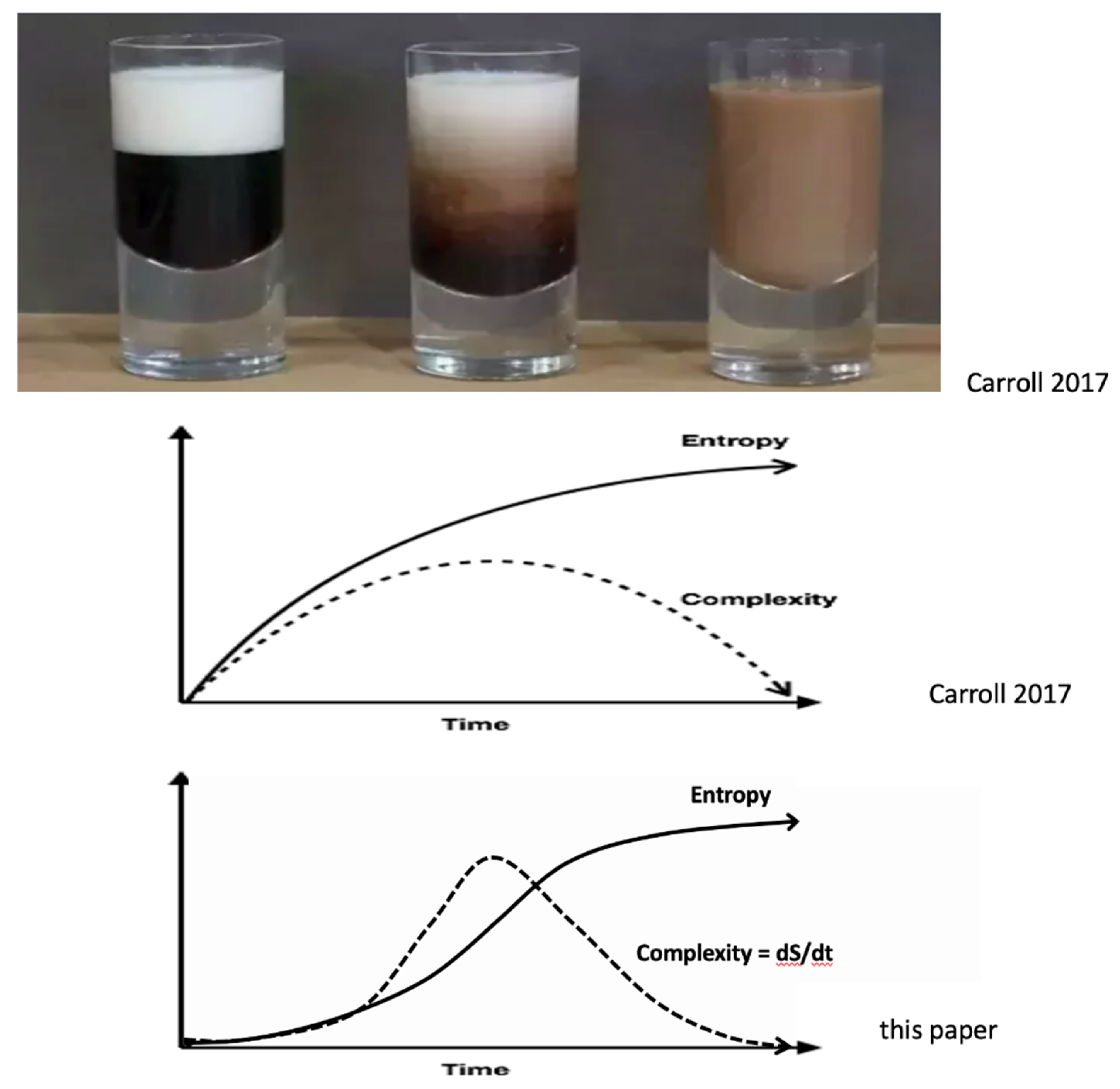

Although complexity is notoriously hard to define, here we propose a potentially useful operational definition: complexity =

dS/dt. This definition is illustrated in the bottom panel in

Figure 2 and is quite different from the middle panel. To test which model is more correct one could take a video of this process and, using a file-compression algorithm, quantify the complexity of the turbulent swirls (Carroll 2017, p 232).

Figure 2.

Coffee, Cream, Entropy and Complexity. The top panel shows three stages in the process of cream mixing with coffee (Aaronson et al 2014, Carroll 2017, Chapter 28). In the left image of the top panel the cream and coffee are separate and unmixed; low entropy. In the middle image of the top panel, complex convection, turbulent swirls and diffusion mix the cream and coffee. In the right image of the top panel the cream and coffee are completely mixed at equilibrium and at maximum entropy. Although complexity is famously hard to define just below the three photos is Carroll’s notional plot of the relationship between entropy and complexity during this cream/coffee mixing process. The entropy starts low and ends high. On the other hand, the complexity of the convective swirls starts low, reaches a maximum when the most complicated range of swirls is most effectively mixing the cream with the coffee, and then complexity decreases as the swirls disappear. The lowest plot is an alternative view of the relationship between entropy and complexity. It assumes that complexity is identical (or proportional to) entropy production: complexity = dS/dt. This plot is based on the idea that the more complex the convective swirls and fluid turbulence are, the more entropy is being produced -- both by the undoing of the concentration gradients by the swirls and by the free energy needed to maintain the swirls. Notice that in Carroll’s notional plot, dS/dt (the slope of the entropy curve) is a maximum at the very beginning of the mixing when most of the swirling convective complexity has not yet developed and decreases monotonically from that maximum.

Figure 2.

Coffee, Cream, Entropy and Complexity. The top panel shows three stages in the process of cream mixing with coffee (Aaronson et al 2014, Carroll 2017, Chapter 28). In the left image of the top panel the cream and coffee are separate and unmixed; low entropy. In the middle image of the top panel, complex convection, turbulent swirls and diffusion mix the cream and coffee. In the right image of the top panel the cream and coffee are completely mixed at equilibrium and at maximum entropy. Although complexity is famously hard to define just below the three photos is Carroll’s notional plot of the relationship between entropy and complexity during this cream/coffee mixing process. The entropy starts low and ends high. On the other hand, the complexity of the convective swirls starts low, reaches a maximum when the most complicated range of swirls is most effectively mixing the cream with the coffee, and then complexity decreases as the swirls disappear. The lowest plot is an alternative view of the relationship between entropy and complexity. It assumes that complexity is identical (or proportional to) entropy production: complexity = dS/dt. This plot is based on the idea that the more complex the convective swirls and fluid turbulence are, the more entropy is being produced -- both by the undoing of the concentration gradients by the swirls and by the free energy needed to maintain the swirls. Notice that in Carroll’s notional plot, dS/dt (the slope of the entropy curve) is a maximum at the very beginning of the mixing when most of the swirling convective complexity has not yet developed and decreases monotonically from that maximum.

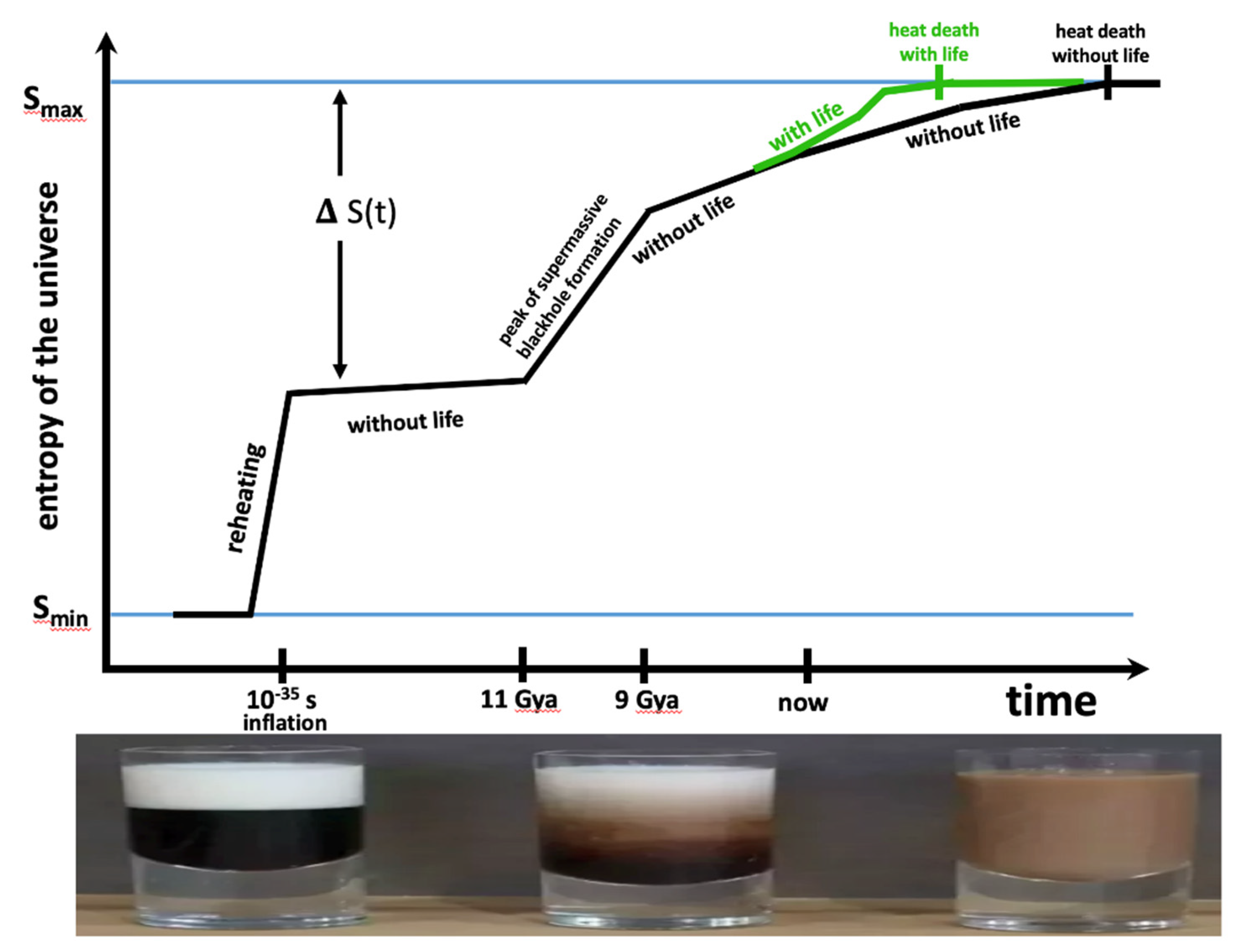

We assume that the universe started out at very low entropy. This is the “Past Hypothesis” (Albert 2000, Ainsworth 2008). We know almost nothing about the universe before inflation. Inflation expanded and cooled whatever was there. The first and steepest increase of the entropy of the universe when dS/dt was at its maximum value, happened at the end of inflation during reheating ~ 10-35 seconds after the big bang. During reheating, the potential energy of the inflaton field decayed and became coupled to, and excited all the other quantum fields. The excitation of these fields was the creation of all the matter and energy in a hot dense universe. Thus, the one degree of freedom of the potential energy of the inflaton scalar field became distributed over all the particles in the universe. This spreading out of the potential energy to many more degrees of freedom is what increased the entropy of the universe.

After reheating, the second steepest increase in entropy (second largest value of dS/dt) occurred between 11 billion years ago and 9 billion years ago. Quasar observations suggest that this is the time of peak supermassive blackhole (SMBH) formation (Serjeant et al 2010). SMBHs are the largest reservoir of entropy in the universe (Egan & Lineweaver 2010). They did not exist at the big bang or at recombination so they acquired their large entropies more than a billion years after the big bang.

Comparing the black and green lines in

Figure 3 illustrates the idea that lifeforms (abiotic FFEDS) increase the entropy of the universe more than would be the case if it didn’t exist. As suggested in the top right of

Figure 3, the entropy produced by life initially makes a tiny contribution to the total entropy. See Egan & Lineweaver (2010) and Lineweaver (2013) for details of the abiotic history of entropy in the universe.

Figure 3.

The Universe in a Cup of Coffee. Top panel: The entropy of the universe as a function of time without life (black line) and with life (green line). This sketch is based on Figure 22.2 of Lineweaver 2014 and Figure 6 of Egan & Lineweaver 2010. The universe starts out on the left at low entropy S

min and ends up on the right at an equilibrium heat death of maximum entropy S

max. ΔS(t) is a measure of the number of degrees of freedom which will eventually but have not yet, become accessible. I have assumed that the total number of eventually accessible degrees of freedom will not depend on whether life exists or not. As life evolves it becomes a more efficient catalyst, making more free energy available, thus increasing the entropy of the universe compared to a universe without life. Thus, a universe with life (green line) reaches a heat death (S

max) sooner than a universe without life. As the universe approaches the heat death, there are fewer gradients that can maintain life forms or the abiotic sources of entropy production. Thus, for both the green and black lines, the slope dS/dt → 0 as the universe approaches its heat death. Bottom panel: this cream/coffee sequence from

Figure 2 is a model for the past, present and future entropy production in the universe. The universe starts out at low entropy (unmixed cream and coffee). Then concentration, thermal and kinetic gradients between the cream and coffee produce a complex mixture of convective swirls which mix the cream and coffee, thus undoing the gradients. When these gradients are gone, we have an equilibrium or heat death in which there are no gradients to support FFEDS. A gaggle of the most advanced Kardeshev Type III civilizations might be responsible for the steepest slope (=, largest dS/dt) of the green line.

Figure 3.

The Universe in a Cup of Coffee. Top panel: The entropy of the universe as a function of time without life (black line) and with life (green line). This sketch is based on Figure 22.2 of Lineweaver 2014 and Figure 6 of Egan & Lineweaver 2010. The universe starts out on the left at low entropy S

min and ends up on the right at an equilibrium heat death of maximum entropy S

max. ΔS(t) is a measure of the number of degrees of freedom which will eventually but have not yet, become accessible. I have assumed that the total number of eventually accessible degrees of freedom will not depend on whether life exists or not. As life evolves it becomes a more efficient catalyst, making more free energy available, thus increasing the entropy of the universe compared to a universe without life. Thus, a universe with life (green line) reaches a heat death (S

max) sooner than a universe without life. As the universe approaches the heat death, there are fewer gradients that can maintain life forms or the abiotic sources of entropy production. Thus, for both the green and black lines, the slope dS/dt → 0 as the universe approaches its heat death. Bottom panel: this cream/coffee sequence from

Figure 2 is a model for the past, present and future entropy production in the universe. The universe starts out at low entropy (unmixed cream and coffee). Then concentration, thermal and kinetic gradients between the cream and coffee produce a complex mixture of convective swirls which mix the cream and coffee, thus undoing the gradients. When these gradients are gone, we have an equilibrium or heat death in which there are no gradients to support FFEDS. A gaggle of the most advanced Kardeshev Type III civilizations might be responsible for the steepest slope (=, largest dS/dt) of the green line.

In

Figure 4 we see

dS/dt going up and down, increasing and decreasing. Thus, hypothesis 2B doesn’t seem to describe abiotic FFEDS entropy production on cosmic time scales. However, the first few billion years of biotic FFEDS entropy production (which includes the survival of our techno FFEDS ancestors) does conform to hypothesis 2B in that over the first half of the green line, it increases with time. However, since ΔS(t) in

Figure 3 is a measure of the remaining free energy in the universe. And it goes to zero as the universe approaches the heat death, we can use it to add a free-energy-availability constraint to 2B and call it 2B’ :

(2B’) The entropy production dS/dt of the universe tends to a maximum (i.e. d2S/dt2 ≥ 0)

subject to the constraint that entropy production must always be limited by:

where ΔS(t) = S

max – S(t) in

Figure 2 and

thd is the time of the heat death.

The time dependence of cosmic entropy production is sketched in

Figure 4. Since hypothesis 2B’clearly does not describe the cosmic history of abiotic entropy production, a better understanding of the constraints on abiotic FFEDS are needed. The universe starts out with only abiotic FFEDS. With the emergence of life, some become biotic FFEDS with an open-ended Darwinian evolution. And with the emergence of technology, some biotic FFEDS become techno FFEDS. Hypothesis 2B’ has more potential as a descriptor of the early history of biotic and techno FFEDS at least until the approach of the heat death becomes the limiting factor.

References

- Aaronson, S.; Carroll, S.; Ouellett, L. 2014. Quantifying the rise and fall of complexity in closed systems: the coffee automaton. arXiv preprint arXiv:1405.6903.

- Adams, F.C. 2002. Origins of Existence: How Life Emerged in the Universe; The Free Press, NY.

- Ainsworth, P.M. 2008. Cosmic Inflation and the past hypothesis. Synthese, 162, 2 157-165. [CrossRef]

- Albert, D. 2000. Time and Chance; Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-26138-9.

- Al-Shayeb, B. Sachdeva, R. Chen, L-X., Ward, F. Munk, P….Banfield, J 2020. Clades of huge phages from across Earth’s ecosystems. Nature, 578, 425-431.

- Bejan, A. 2006. Advanced Engineering Thermodynamics, Chapter 13, The Constructal Law of Configuration Generation, p 705-841.

- Bejan A, Lorente S. The constructal law and the evolution of design in nature. Phys Life Rev 2011; 8:209-40. [CrossRef]

- Ben-Naim, A. 2019. Entropy and Information Theory: Uses and Misuses. Entropy 21, 12, 1170. [CrossRef]

- Benner SA. 2010, Defining life. Astrobiology. 10(10):1021–30. https://doi.org/10.1089/ast.2010.0524. [CrossRef]

- Branscomb, E.; Russell, M. J. 2013. Turnstiles and bifurcators: The disequilibrium converting engines that put metabolism on the road. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 1827, 62-78. [CrossRef]

- Brooks, D.R.; Wiley, E.O. 1988, Evolution as Entropy; 2nd Edition, University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

- Brown, G. 1999. The Energy of life; Flamingo Harpur Collins London.

- Carroll, S. 2017. The Big Picture: On the Origin of Life, Meaning, and the Universe Itself; Penguin, UK.

- Castelle, C.J. and Banfield, J.F., 2018. Major new microbial groups expand diversity and alter our. [CrossRef]

- understanding of the tree of life. Cell, 172, 1181–1197, 2018.

- Cech, T. 2012. The RNA Worlds in Context. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology,.

- Edt J.F. Atkins, R.F. Gesteland, T.R. Cech. 4:a006742.

- Chaisson, E.J. 2002. Cosmic Evolution: The Rise of Complexity in Nature (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

- Clausius, R. 1865. Mechanical Theory of Heat – Nine Memoirs on the development of concept of “Entropy”.

- Conway Morris, S. 2014. Life: the final frontier for complexity? Chapter 7 in Lineweaver et al 2014, Cambridge Univ. Press.

- Darwin C. 1859. Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection.

- Dennett, D.C. 1995. Darwin’s Dangerous Idea: Evolution and the Meanings of Life; Simon & Schuster, NY.

- Dewar, R.C. 2005. Maximum entropy production and the fluctuation theorem. J. Phys. A 2005, 38, 371–381. [CrossRef]

- Dewar, R.C. 2009. Maximum entropy production as an algorithm that translates physical assumptions into macroscopic predictions: don’t shoot the messenger. Entropy (Special Issue. What is maximum entropy production and how should we apply it?) 11, 931-944 doi:10.3390/e11040931. [CrossRef]

- Dewar, R.C.; Lineweaver, C.H.; Niven, R.K.; Regenauer-Lieb, K. edts 2014a. Beyond the Second Law: Entropy Production and Non-equilibrium Systems, Springer, Berlin.

- Dewar, R.C, Lineweaver, C.H., Niven, R.K., Regenauer-Lieb, K. 2014b. Beyond the Second Law: An Overview. Chapter 1 of Dewar et al 2014a, pp 3-30.

- Diener T.O. 1971. “Potato spindle tuber “virus”. IV. A replicating, low molecular weight RNA”. Virology. 45 (2): 411–28. doi:10.1016/0042-6822(71)90342-4. [CrossRef]

- Dobovisek, A, Zupanovic, P, Brumen, M. & Juretic, D. 2014. Maximum Entropy Production and Maximum Shannon Entropy as Germane Principles for the Evolution of Enzyme Kinetics, Chapter 19 in Dewar et al 2014.

- Dollo, L. 1893. Les lois de l’évolution. Bull. Soc. Belge Geol. Pal. Hydr. VII: 164–166.

- Dyson, F. 1971. Energy in the Universe. Scientific American, 225, 3, 50-58.

- Dyson, F. 1999. Origins of Life, 2nd Edt. Cambridge University Press, UK.

- Egan, C.; Lineweaver, C.H. 2010. A larger estimate of the entropy of the universe, Astrophysical Journal, 710:1825-1834. [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, W. 1986. The RNA World, Nature, 319, 618.

- Godfrey-Smith P. 2009. Darwinian Populations and Natural Selection, Oxford University Press.

- Gould, S. J. 1970. “Dollo on Dollo’s law: irreversibility and the status of evolutionary laws”. Journal of the History of Biology. 3 (2): 189–212. doi:10.1007/bf00137351. PMID 11609651. S2CID 45642853. [CrossRef]

- Gould, S.J. 1981. The Mismeasure of Man, Penguin, UK.

- Gould, S.J. 1994. The Evolution of Life on Earth, Scientific American, October, 1994. [CrossRef]

- Gould, S.J. 2002. The Structure of Evolutionary Theory, Harvard Univ. Press, Cambridge.

- Haff, P.K. 2014. Maximum Entropy Production by Technology, Chapter 21 in Dewar et al 2014, pp 397-414.

- Hazen, R.M. 2005. Genesis: the scientific quest for life’s origin, Joseph Henry Press, Washington, D.C.

- Hoffman, P.M. 2012. Life’s Ratchet: How molecular machines extract order from chaos, Basic Books, NY.

- Hou X, He Y, Fang P, Mei SQ, Xu Z, Wu WC, Tian JH, Zhang S, Zeng ZY, Gou QY, Xin GY. Using artificial intelligence to document the hidden RNA virosphere. bioRxiv. 2023 Apr 18:2023-04 doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.18.537342. [CrossRef]

- Hug, L.A.; Baker, B.J.; Anantharaman, K.; Brown, C.T.; Probst, A.J.; Castelle, C.J.; Butterfield,.

- C.N.; Hernsdorf, A.W.; Amano, Y.; Ise, K. et al., A new view of the tree of life. Nat. Microbiol.,.

- 1, 5, 16048, 2016.

- Kardashev, N. S. 1964. Transmission of information by extraterrestrial civilizations. Soviet Astronomy. 8: 217.

- Kardashev, N. S. 1997. Cosmology and Civilizations. Astrophysics and Space Science. 252 (1): 25–40. doi:10.1023/A:1000837427320. [CrossRef]

- Keller, E.F. 1983. A Feeling for the Organism: the life and work of Barbara McClintock, Freeman NY. [CrossRef]

- Kleidon, A.; Lorenz, R.D. 2005. Non-equilibrium Thermodynamics and the Production of Entropy: Life, Earth and Beyond, Springer.

- Kleidon, A. 2010a. A basic introduction to the thermodynamics of the Earth system far from equilibrium and maximum entropy production, Phil. Trans. R. Soc B 365, 1303-1315. [CrossRef]

- Kleidon, A. 2010b. Life, hierarchy, and the thermodynamic machinery of planet Earth Phys. Life Rev. 7, 424.

- Kondepudi, D.; Prigogine, I. 2006 Modern Thermodynamics: From Heat Engines to Dissipative Structures, Wiley & Sons,.

- Koonin, E.V.;Dolja, V.V., 2014. Virus world as an evolutionary network of viruses and capsidless. [CrossRef]

- selfish elements. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev., 78, 2, 278–303.

- Lineweaver CH, Egan C. 2008. Life, gravity and the second law of thermodynamics, Physics of Life Reviews 5 225-242. [CrossRef]

- Lineweaver CH, Davies PCW, Ruse M. 2013. Complexity and the Arrow of Time, Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge.

- Lineweaver CH. 2014. The Entropy of the Universe and the Maximum Entropy Production Principle, pp 415-427 Chapter 22 in Beyond the Second Law: Entropy Production and Non-equilibrium Systems, edt RC Dewar, CH Lineweaver, R.K Niven and K. Regenauer-Lieb, Springer,.

- Lineweaver, CH 2013. A Simple Treatment of Complexity, Chapter 3 in Lineweaver et al 2013, pp 42-67.

- Lineweaver, CH 2020. What Do the DPANN Archaea and the CPR Bacteria Tell Us about the Last.

- Universal Common Ancestors? Chapter 17 in Joseph Seckbach and Helga Stan-Lotter (eds.) Extremophiles as Astrobiological Models, (359–368).

- Lovelock, JE & Margulis, L. 1974. Biological Modulation of the Earth’s Atmosphere, Icarus. [CrossRef]

- 1974 Atmospheric homeostasis by and for the biosphere: the gaia hypothesis, Tellus XXVI 1-2.

- Martyshev LM Seleznev VD 2006. Maximum Entropy Production Principle in physics, chemistry and biology, Physics Reports 426, 1-45.

- Mayr, E. 2001. What is Evolution? Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London.

- McShea DW, Brandon RN. 2010. Biology’s first law: the tendency for diversity and complexity to increase in evolutionary systems. University of Chicago Press.

- Moody ERR et al 2024. The nature of the last universal common ancestor and its impact on the early Earth system, Nature Ecology and evolution, doi.org/10.1038/s41559-024-02461-1. [CrossRef]

- Nasir, A.; Caetano-Anolles, G. 2015. A phylogenomic data-driven exploration of viral origins and evolution Sci. Adv. 2015;1:e1500527.

- Neveu, M.; Kim, H.J.; Benner, S.A. 2013. The “strong” RNA world hypothesis: fifty years old. Astrobiology. 13 (4): 391–403. doi:10.1089/ast.2012.0868. [CrossRef]

- Onsager, L. 1931a. Reciprocal relations in irreversible processes I. Phys Rev. 37, 405-426. [CrossRef]

- Onsager, L. 1931b. Reciprocal relations in irreversible processes II. Phys Rev. 38, 2265-2279. [CrossRef]

- Penrose, R.; Floyd, R. M. 1971. “Extraction of Rotational Energy from a Black Hole”. Nature Physical Science. 229 (6): 177–179. doi:10.1038/physci229177a0. [CrossRef]

- Prigogine, I. 1978. Time, structure and fluctuations. Science 1978; 201:777–85.

- Prigogine, I.; Stengers, I. 1984. Order out of Chaos: man’s new dialog with nature, NY, W.H. Freeman and Co.

- Ruse, M. 2013. Wrestling with biological complexity: from Darwin to Dawkins, Chapter 12 in Lineweaver et al 2013, pp 279-307,.

- Ruse, M. & Travis, J. 2009. Evolution: The First Four Billion Years, Belkap Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

- Schneider, E.D. & Kay, J.J. 1994. Life as a Manifestation of the Second Law of Thermdynamcis, Mathl. Comput. Modelling 19, 6-8, pp 25-84.

- Schneider, ED. and Sagan,D. 2005. Into the Cool: Energy Flow, Thermodynamics and Life, University of Chicago Press.

- Schrödinger, E. 1948 What Is Life? The Physical Aspect of the Living Cell. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK.

- Segre, D.; Lancet D. 1999. A Statistical chemistry approach to the origin of life, Chemtrasts – Biochem. Mol. Biol. 12, 6, 382-397.

- Serjeant, S.; Bertoldi, F., Blain, A.W., Clements, D.L, Cooray, A, Danese, L. Dunlop, J et al.

- 2010. Herschel ATLAS: The cosmic star formation history of quasar host galaxies, Astronomy & Astrophysics, 518, L7, DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201014565. [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.M. & Szathmary, E. 1999. The origins of life: From the birth of Life to the Origins of Language, Oxford University Press, UK.

- Szostak, J.W. 2012. Attempts to Define Life Do Not Help to Understand the Origin of Life, Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics, 29, 4, 599-600. [CrossRef]

- Weber, B.H. Depew, D.J. & Smith, J.D. 1990. Entropy, Information and Evolution, MIT Press, Cambridge, Ma.

- Weiss, M.C. Sousa, F.L., Mrnjavac, N. Neukirchen, S. Roettger, M., Nelson-Sathi, S and Martin, W.

- 2016. Nature Microbiology, 16116, DOI: 10.1038/NMICROBIOL.2016.116. [CrossRef]

- Weng, J-K, 2013. The evolutionary paths towards complexity: a metabolic perspective, New Phytologist 201, 1141-1149, doi: 10.1111/nph.12416. [CrossRef]

- West, G. 2017, Scale: The universal laws of life and death in organisms, Cities and Companies, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London.

- Wilson, D.S. 2019. This View of Life: Contemplating the Darwinian Revolution, Pantheon Books, NY.

- Wrangham, R. 2009. Catching Fire: How Cooking Made us Human, Basic Books, NY.

- Zupanovic, P. Kuic, D Juretic, D. & Dobovisek, A. 2010. On the Problem of Formulating Principles in Nonequilibrium Thermodynamics, Entropy 2010, 12(4), 926-931; doi.org/10.3390/e12040926. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).