Submitted:

04 December 2024

Posted:

05 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Information Sources

2.4. Search Strategy

2.5. Types of Participants

2.6. Types of Interventions

2.7. Types of Comparison Controls

2.8. Outcomes Measures

2.9. Study Selection and Data Extraction

2.10. Quality Assessment

3. Results

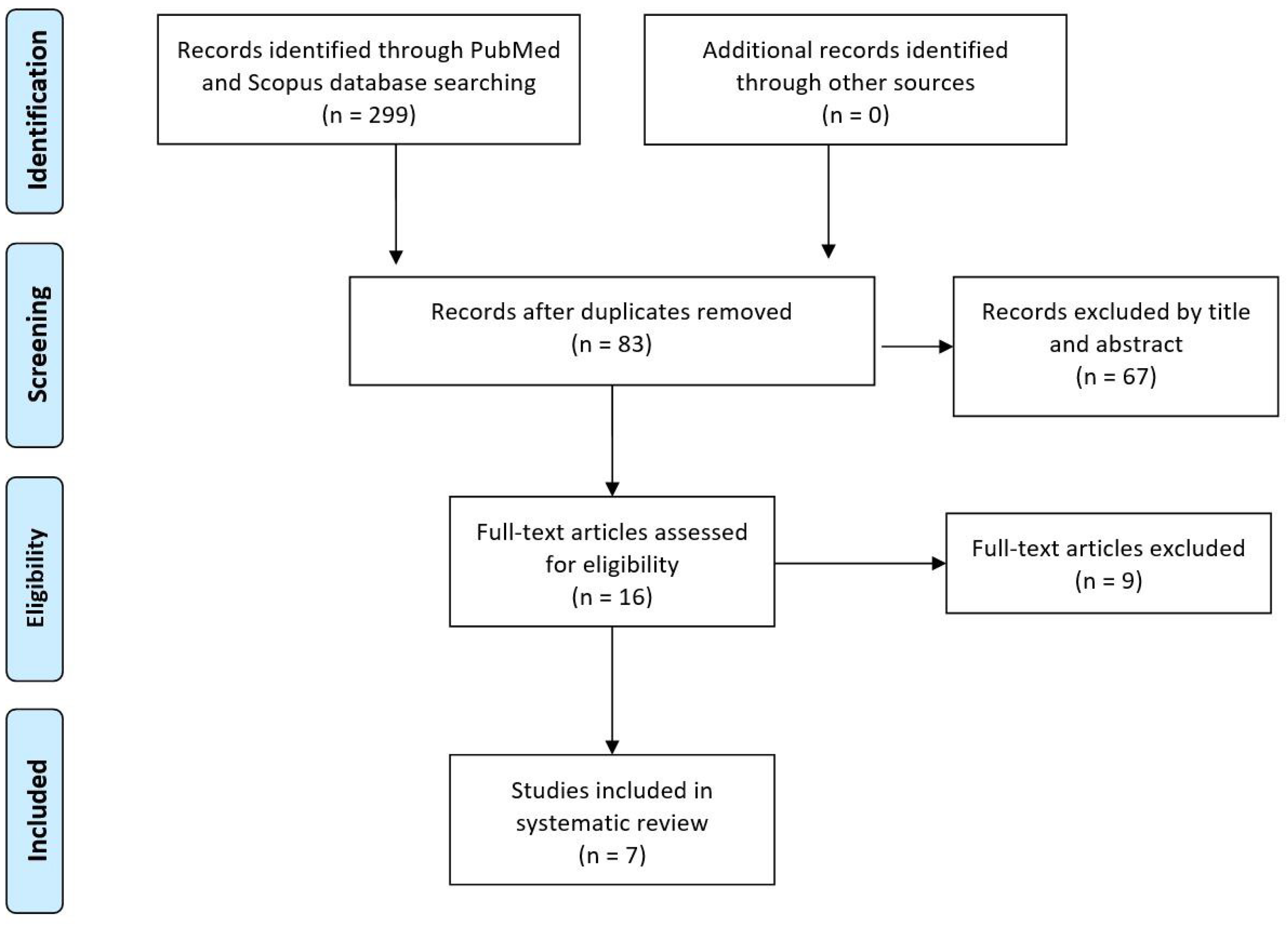

3.1. Eligible Studies

3.2. Quality of the Included Studies

3.3. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.4. Clinical Assessment

3.5. Injection Technique

3.6. Adverse Events

3.7. Rehabilitation

3.8. Primary and Secondary Outcomes Evaluation

3.9. Collagen Versus Active Controls

4. Discussion

Study limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dugas, J.R.; Campbell, D.A.; Warren, R.F.; Robie, B.H.; Millett, P.J. Anatomy and Dimensions of Rotator Cuff Insertions. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002, 11, 498–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nho, S.J.; Yadav, H.; Shindle, M.K.; Macgillivray, J.D. Rotator Cuff Degeneration: Etiology and Pathogenesis. Am. J. Sports Med. 2008, 36, 987–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maffulli, N.; Longo, U.G.; Berton, A.; Loppini, M.; Denaro, V. Biological Factors in the Pathogenesis of Rotator Cuff Tears. Sports Med. Arthrosc. Rev. 2011, 19, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longo, U.G.; Berton, A.; Papapietro, N.; Maffulli, N.; Denaro, V. Epidemiology, Genetics and Biological Factors of Rotator Cuff Tears. Med. Sport Sci. 2012, 57, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, R.; Di Iorio, A.; Del Prete, C.M.; Barassi, G.; Paolucci, T.; Tognolo, L.; Fiore, P.; Santamato, A. Efficacy of Ultrasound-Guided Percutaneous Lavage and Biocompatible Electrical Neurostimulation, in Calcific Rotator Cuff Tendinopathy and Shoulder Pain, A Prospective Pilot Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 5837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuè, G.; Masuzzo, O.; Tucci, F.; Cavallo, M.; Parmeggiani, A.; Vita, F.; Patti, A.; Donati, D.; Marinelli, A.; Miceli, M.; et al. Can Secondary Adhesive Capsulitis Complicate Calcific Tendinitis of the Rotator Cuff? An Ultrasound Imaging Analysis. Clin. Pract. 2024, 14, 579–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farì, G.; Megna, M.; Ranieri, M.; Agostini, F.; Ricci, V.; Bianchi, F.P.; Rizzo, L.; Farì, E.; Tognolo, L.; Bonavolontà, V.; et al. Could the Improvement of Supraspinatus Muscle Activity Speed up Shoulder Pain Rehabilitation Outcomes in Wheelchair Basketball Players? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 20, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, H. Partial-Thickness Rotator Cuff Tears: A Modern View on Codman’s Classic. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000, 9, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.Y.; Khil, E.K.; Kim, T.S.; Kim, Y.W. Effect of Co-Administration of Atelocollagen and Hyaluronic Acid on Rotator Cuff Healing. Clin. Shoulder Elb. 2021, 24, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, V.; Özçakar, L. The Dodo Bird Is Not Extinct: Ultrasound Imaging for Supraspinatus Tendinosis. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2019, 98, e8–e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamanaka, K.; Matsumoto, T. The Joint Side Tear of the Rotator Cuff. A Followup Study by Arthrography. Clin. Orthop. 1994, 68–73. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, I.B.; Kim, E.Y.; Lim, K.P.; Heo, K.S. Does the Use of Injectable Atelocollagen during Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair Improve Clinical and Structural Outcomes? Clin. Shoulder Elb. 2019, 22, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricci, V.; Özçakar, L. Looking into the Joint When It Is Frozen: A Report on Dynamic Shoulder Ultrasound. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 2019, 32, 663–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jost, B.; Pfirrmann, C.W.; Gerber, C.; Switzerland, Z. Clinical Outcome after Structural Failure of Rotator Cuff Repairs. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2000, 82, 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, V.; Chang, K.-V.; Güvener, O.; Mezian, K.; Kara, M.; Leblebicioğlu, G.; Stecco, C.; Pirri, C.; Ata, A.M.; Dughbaj, M.; et al. EURO-MUSCULUS/USPRM Dynamic Ultrasound Protocols for Shoulder. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2022, 101, e29–e36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugaya, H.; Maeda, K.; Matsuki, K.; Moriishi, J. Repair Integrity and Functional Outcome after Arthroscopic Double-Row Rotator Cuff Repair. A Prospective Outcome Study. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2007, 89, 953–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.H.; Kim, S.H.; Ji, H.M.; Jo, K.H.; Bin, S.W.; Gong, H.S. Prognostic Factors Affecting Anatomic Outcome of Rotator Cuff Repair and Correlation with Functional Outcome. Arthrosc. J. Arthrosc. Relat. Surg. Off. Publ. Arthrosc. Assoc. N. Am. Int. Arthrosc. Assoc. 2009, 25, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, V.; Mezian, K.; Chang, K.-V.; Özçakar, L. Clinical/Sonographic Assessment and Management of Calcific Tendinopathy of the Shoulder: A Narrative Review. Diagn. Basel Switz. 2022, 12, 3097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abtahi, A.M.; Granger, E.K.; Tashjian, R.Z. Factors Affecting Healing after Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair. World J. Orthop. 2015, 6, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazzam, M.; Sager, B.; Box, H.N.; Wallace, S.B. The Effect of Age on Risk of Retear after Rotator Cuff Repair: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JSES Int. 2020, 4, 625–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thankam, F.G.; Dilisio, M.F.; Gross, R.M.; Agrawal, D.K. Collagen I: A Kingpin for Rotator Cuff Tendon Pathology. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2018, 10, 3291–3309. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ryösä, A.; Laimi, K.; Äärimaa, V.; Lehtimäki, K.; Kukkonen, J.; Saltychev, M. Surgery or Conservative Treatment for Rotator Cuff Tear: A Meta-Analysis. Disabil. Rehabil. 2017, 39, 1357–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrado, B.; Bonini, I.; Alessio Chirico, V.; Rosano, N.; Gisonni, P. Use of Injectable Collagen in Partial-Thickness Tears of the Supraspinatus Tendon: A Case Report. Oxf. Med. Case Rep. 2020, 2020, omaa103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conaire, E.Ó.; Delaney, R.; Lädermann, A.; Schwank, A.; Struyf, F. Massive Irreparable Rotator Cuff Tears: Which Patients Will Benefit from Physiotherapy Exercise Programs? A Narrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2023, 20, 5242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominguez-Romero, J.G.; Jiménez-Rejano, J.J.; Ridao-Fernández, C.; Chamorro-Moriana, G. Exercise-Based Muscle Development Programmes and Their Effectiveness in the Functional Recovery of Rotator Cuff Tendinopathy: A Systematic Review. Diagn. Basel Switz. 2021, 11, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vita, F.; Pederiva, D.; Tedeschi, R.; Spinnato, P.; Origlio, F.; Faldini, C.; Miceli, M.; Stella, S.M.; Galletti, S.; Cavallo, M.; et al. Adhesive Capsulitis: The Importance of Early Diagnosis and Treatment. J. Ultrasound 2024, 27, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraskevopoulos, E.; Plakoutsis, G.; Chronopoulos, E.; Maria, P. Effectiveness of Combined Program of Manual Therapy and Exercise Vs Exercise Only in Patients With Rotator Cuff-Related Shoulder Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Health 2023, 15, 727–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Castillo, M.; Cuesta-Vargas, A.; Luque-Teba, A.; Trinidad-Fernández, M. The Role of Progressive, Therapeutic Exercise in the Management of Upper Limb Tendinopathies: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Musculoskelet. Sci. Pract. 2022, 62, 102645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farì, G.; Megna, M.; Fiore, P.; Ranieri, M.; Marvulli, R.; Bonavolontà, V.; Bianchi, F.P.; Puntillo, F.; Varrassi, G.; Reis, V.M. Real-Time Muscle Activity and Joint Range of Motion Monitor to Improve Shoulder Pain Rehabilitation in Wheelchair Basketball Players: A Non-Randomized Clinical Study. Clin. Pract. 2022, 12, 1092–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeClercq, M.G.; Fiorentino, A.M.; Lengel, H.A.; Ruzbarsky, J.J.; Robinson, S.K.; Oberlohr, V.T.; Whitney, K.E.; Millett, P.J.; Huard, J. Systematic Review of Platelet-Rich Plasma for Rotator Cuff Repair: Are We Adhering to the Minimum Information for Studies Evaluating Biologics in Orthopaedics? Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2021, 9, 23259671211041971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannetti de Sanctis, E.; Franceschetti, E.; De Dona, F.; Palumbo, A.; Paciotti, M.; Franceschi, F. The Efficacy of Injections for Partial Rotator Cuff Tears: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 10, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prodromos, C.C.; Finkle, S.; Prodromos, A.; Chen, J.L.; Schwartz, A.; Wathen, L. Treatment of Rotator Cuff Tears with Platelet Rich Plasma: A Prospective Study with 2 Year Follow-Up. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2021, 22, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palermi, S.; Gnasso, R.; Belviso, I.; Iommazzo, I.; Vecchiato, M.; Marchini, A.; Corsini, A.; Vittadini, F.; Demeco, A.; De Luca, M.; et al. Stem Cell Therapy in Sports Medicine: Current Applications, Challenges and Future Perspectives. J. Basic Clin. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longo, U.G.; Lalli, A.; Medina, G.; Maffulli, N. Conservative Management of Partial Thickness Rotator Cuff Tears: A Systematic Review. Sports Med. Arthrosc. Rev. 2023, 31, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrado, B.; Bonini, I.; Chirico, V.; Filippini, E.; Liguori, L.; Magliulo, G.; Mazzuoccolo, G.; Rosano, N.; Gisonni, P. Ultrasound-Guided Collagen Injections in the Treatment of Supraspinatus Tendinopathy: A Case Series Pilot Study. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2020, 34, 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.J.; Yeo, S.M.; Noh, S.J.; Ha, C.-W.; Lee, B.C.; Lee, H.S.; Kim, S.J. Effect of Platelet-Rich Plasma on the Degenerative Rotator Cuff Tendinopathy According to the Compositions. J. Orthop. Surg. 2019, 14, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, J.A.; Cole, B.J.; Spatny, K.P.; Sundman, E.; Romeo, A.A.; Nicholson, G.P.; Wagner, B.; Fortier, L.A. Leukocyte-Reduced Platelet-Rich Plasma Normalizes Matrix Metabolism in Torn Human Rotator Cuff Tendons. Am. J. Sports Med. 2015, 43, 2898–2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, A.; Eroglu, A. Comparison of Ultrasound-Guided Platelet-Rich Plasma, Prolotherapy, and Corticosteroid Injections in Rotator Cuff Lesions. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 2020, 33, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sire, A.; Lippi, L.; Mezian, K.; Calafiore, D.; Pellegrino, R.; Mascaro, G.; Cisari, C.; Invernizzi, M. Ultrasound-Guided Platelet-Rich-Plasma Injections for Reducing Sacroiliac Joint Pain: A Paradigmatic Case Report and Literature Review. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 2022, 35, 977–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vascellari, A.; Demeco, A.; Vittadini, F.; Gnasso, R.; Tarantino, D.; Belviso, I.; Corsini, A.; Frizziero, A.; Buttinoni, L.; Marchini, A.; et al. Orthobiologics Injection Therapies in the Treatment of Muscle and Tendon Disorders in Athletes: Fact or Fake? Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2024, 14, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsui, Y.; Gotoh, M.; Nakama, K.; Yamada, T.; Higuchi, F.; Nagata, K. Hyaluronic Acid Inhibits mRNA Expression of Proinflammatory Cytokines and Cyclooxygenase-2/Prostaglandin E(2) Production via CD44 in Interleukin-1-Stimulated Subacromial Synovial Fibroblasts from Patients with Rotator Cuff Disease. J. Orthop. Res. Off. Publ. Orthop. Res. Soc. 2008, 26, 1032–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honda, H.; Gotoh, M.; Kanazawa, T.; Ohzono, H.; Nakamura, H.; Ohta, K.; Nakamura, K.; Fukuda, K.; Teramura, T.; Hashimoto, T.; et al. Hyaluronic Acid Accelerates Tendon-to-Bone Healing After Rotator Cuff Repair. Am. J. Sports Med. 2017, 45, 3322–3330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manferdini, C.; Guarino, V.; Zini, N.; Raucci, M.G.; Ferrari, A.; Grassi, F.; Gabusi, E.; Squarzoni, S.; Facchini, A.; Ambrosio, L.; et al. Mineralization Behavior with Mesenchymal Stromal Cells in a Biomimetic Hyaluronic Acid-Based Scaffold. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 3986–3996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osti, L.; Berardocco, M.; di Giacomo, V.; Di Bernardo, G.; Oliva, F.; Berardi, A.C. Hyaluronic Acid Increases Tendon Derived Cell Viability and Collagen Type I Expression in Vitro: Comparative Study of Four Different Hyaluronic Acid Preparations by Molecular Weight. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2015, 16, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellegrino, R.; Brindisino, F.; Barassi, G.; Sparvieri, E.; DI Iorio, A.; de Sire, A.; Ruosi, C. Combined Ultrasound Guided Peritendinous Hyaluronic Acid (500-730 Kda) Injection with Extracorporeal Shock Waves Therapy vs. Extracorporeal Shock Waves Therapy-Only in the Treatment of Shoulder Pain Due to Rotator Cuff Tendinopathy. A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fitness 2022, 62, 1211–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, R.; Paolucci, T.; Brindisino, F.; Mondardini, P.; Di Iorio, A.; Moretti, A.; Iolascon, G. Effectiveness of High-Intensity Laser Therapy Plus Ultrasound-Guided Peritendinous Hyaluronic Acid Compared to Therapeutic Exercise for Patients with Lateral Elbow Tendinopathy. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 5492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, R.; Di Iorio, A.; Brindisino, F.; Paolucci, T.; Moretti, A.; Iolascon, G. Effectiveness of Combined Extracorporeal Shock-Wave Therapy and Hyaluronic Acid Injections for Patients with Shoulder Pain Due to Rotator Cuff Tendinopathy: A Person-Centered Approach with a Focus on Gender Differences to Treatment Response. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2022, 23, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, D.-S.; Lee, J.-K.; Yoo, J.-C.; Woo, S.-H.; Kim, G.-R.; Kim, J.-W.; Choi, N.-Y.; Kim, Y.; Song, H.-S. Atelocollagen Enhances the Healing of Rotator Cuff Tendon in Rabbit Model. Am. J. Sports Med. 2017, 45, 2019–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aicale, R.; Tarantino, D.; Maffulli, N. Basic Science of Tendons. In Bio-orthopaedics: A New Approach; Gobbi, A., Espregueira-Mendes, J., Lane, J.G., Karahan, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2017; pp. 249–273. ISBN 978-3-662-54181-4. [Google Scholar]

- Thankam, F.G.; Dilisio, M.F.; Agrawal, D.K. Immunobiological Factors Aggravating the Fatty Infiltration on Tendons and Muscles in Rotator Cuff Lesions. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2016, 417, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thankam, F.G.; Evan, D.K.; Agrawal, D.K.; Dilisio, M.F. Collagen Type III Content of the Long Head of the Biceps Tendon as an Indicator of Glenohumeral Arthritis. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2019, 454, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynn, A.K.; Yannas, I.V.; Bonfield, W. Antigenicity and Immunogenicity of Collagen. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2004, 71, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, I.; Mishra, D.; Das, T.; Maiti, S.; Maiti, T.K. Caprine (Goat) Collagen: A Potential Biomaterial for Skin Tissue Engineering. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2012, 23, 355–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarantino, D.; Mottola, R.; Palermi, S.; Sirico, F.; Corrado, B.; Gnasso, R. Intra-Articular Collagen Injections for Osteoarthritis: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2023, 20, 4390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randelli, F.; Menon, A.; Giai Via, A.; Mazzoleni, M.G.; Sciancalepore, F.; Brioschi, M.; Gagliano, N. Effect of a Collagen-Based Compound on Morpho-Functional Properties of Cultured Human Tenocytes. Cells 2018, 7, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinello, T.; Bronzini, I.; Volpin, A.; Vindigni, V.; Maccatrozzo, L.; Caporale, G.; Bassetto, F.; Patruno, M. Successful Recellularization of Human Tendon Scaffolds Using Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Collagen Gel. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2014, 8, 612–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, Y.; Kim, W.-J.; Lee, H. Healing of Partial Tear of the Supraspinatus Tendon after Atelocollagen Injection Confirmed by MRI. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrado, B.; Bonini, I.; Tarantino, D.; Sirico, F. Ultrasound-Guided Collagen Injections for Treatment of Plantar Fasciopathy in Runners: A Pilot Study and Case Series. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Canty, E.G.; Kadler, K.E. Procollagen Trafficking, Processing and Fibrillogenesis. J. Cell Sci. 2005, 118, 1341–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hynes, R.O. Integrins: Bidirectional, Allosteric Signaling Machines. Cell 2002, 110, 673–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massoud, E.I.E. Healing of Subcutaneous Tendons: Influence of the Mechanical Environment at the Suture Line on the Healing Process. World J. Orthop. 2013, 4, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, G.-I.; Ahn, J.-H.; Kim, S.-Y.; Choi, B.-S.; Lee, S.-W. A Hyaluronate-Atelocollagen/Beta-Tricalcium Phosphate-Hydroxyapatite Biphasic Scaffold for the Repair of Osteochondral Defects: A Porcine Study. Tissue Eng. Part A 2010, 16, 1189–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thon, S.G.; O’Malley, L.; O’Brien, M.J.; Savoie, F.H. Evaluation of Healing Rates and Safety With a Bioinductive Collagen Patch for Large and Massive Rotator Cuff Tears: 2-Year Safety and Clinical Outcomes. Am. J. Sports Med. 2019, 47, 1901–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farkash, U.; Avisar, E.; Volk, I.; Slevin, O.; Shohat, N.; El Haj, M.; Dolev, E.; Ashraf, E.; Luria, S. First Clinical Experience with a New Injectable Recombinant Human Collagen Scaffold Combined with Autologous Platelet-Rich Plasma for the Treatment of Lateral Epicondylar Tendinopathy (Tennis Elbow). J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2019, 28, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrado, B.; Mazzuoccolo, G.; Liguori, L.; Chirico, V.A.; Costanzo, M.; Bonini, I.; Bove, G.; Curci, L. Treatment of Lateral Epicondylitis with Collagen Injections: A Pilot Study. Muscle Ligaments Tendons J. 2019, 09, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Choi, Y.S.; You, M.-W.; Kim, J.S.; Young, K.W. Sonoelastography in the Evaluation of Plantar Fasciitis Treatment: 3-Month Follow-Up After Collagen Injection. Ultrasound Q. 2016, 32, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baksh, N.; Hannon, C.P.; Murawski, C.D.; Smyth, N.A.; Kennedy, J.G. Platelet-Rich Plasma in Tendon Models: A Systematic Review of Basic Science Literature. Arthrosc. J. Arthrosc. Relat. Surg. Off. Publ. Arthrosc. Assoc. N. Am. Int. Arthrosc. Assoc. 2013, 29, 596–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacevic, D.; Rodeo, S.A. Biological Augmentation of Rotator Cuff Tendon Repair. Clin. Orthop. 2008, 466, 622–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Albornoz, P.M.; Aicale, R.; Forriol, F.; Maffulli, N. Cell Therapies in Tendon, Ligament, and Musculoskeletal System Repair. Sports Med. Arthrosc. Rev. 2018, 26, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godek, P.; Szczepanowska-Wolowiec, B.; Golicki, D. Collagen and Platelet-Rich Plasma in Partial-Thickness Rotator Cuff Injuries. Friends or Only Indifferent Neighbours? Randomised Controlled Trial. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2022, 23, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padulo, J.; Oliva, F.; Frizziero, A.; Maffulli, N. Basic Principles and Recommendations in Clinical and Field Science Research: 2018 Update. Muscle Ligaments Tendons J 2018, 8, 305–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padulo, J.; De Giorgio, A.; Oliva, F.; Frizziero, A.; Maffulli, N. I Performed Experiments and I Have Results. Wow, and Now? Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2017, 7, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Health Care Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, e1-34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Available online: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current (accessed on 25 August 2023).

- Aldhafian, O.R.; Choi, K.-H.; Cho, H.-S.; Alarishi, F.; Kim, Y.-S. Outcome of Intraoperative Injection of Collagen in Arthroscopic Repair of Full-Thickness Rotator Cuff Tear: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2023, 32, e429–e436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durieux, N.; Vandenput, S.; Pasleau, F. [OCEBM levels of evidence system]. Rev. Med. Liege 2013, 68, 644–649. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Coleman, B.D.; Khan, K.M.; Maffulli, N.; Cook, J.L.; Wark, J.D. Studies of Surgical Outcome after Patellar Tendinopathy: Clinical Significance of Methodological Deficiencies and Guidelines for Future Studies. Victorian Institute of Sport Tendon Study Group. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2000, 10, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancino, F.; Di Matteo, V.; Mocini, F.; Cacciola, G.; Malerba, G.; Perisano, C.; De Martino, I. Survivorship and Clinical Outcomes of Proximal Femoral Replacement in Non-Neoplastic Primary and Revision Total Hip Arthroplasty: A Systematic Review. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2021, 22, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, B.D.; Khan, K.M.; Maffulli, N.; Cook, J.L.; Wark, J.D. Studies of Surgical Outcome after Patellar Tendinopathy: Clinical Significance of Methodological Deficiencies and Guidelines for Future Studies. Victorian Institute of Sport Tendon Study Group. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2000, 10, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, S.H.; Won, J.Y.; Yoo, J.C. Clinical Outcome of Ultrasound-Guided Atelocollagen Injection for Patients with Partial Rotator Cuff Tear in an Outpatient Clinic: A Preliminary Study. Clin. Shoulder Elb. 2020, 23, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Kim, D.-J.; Lee, H.-J.; Kim, B.-K.; Kim, Y.-S. Atelocollagen Injection Improves Tendon Integrity in Partial-Thickness Rotator Cuff Tears: A Prospective Comparative Study. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2020, 8, 2325967120904012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buda, M.; Dlimi, S.; Parisi, M.; Benoni, A.; Bisinella, G.; Di Fabio, S. Subacromial Injection of Hydrolyzed Collagen in the Symptomatic Treatment of Rotator Cuff Tendinopathy: An Observational Multicentric Prospective Study on 71 Patients. JSES Int. 2023, 7, 799–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawker, G.A.; Mian, S.; Kendzerska, T.; French, M. Measures of Adult Pain: Visual Analog Scale for Pain (VAS Pain), Numeric Rating Scale for Pain (NRS Pain), McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ), Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ), Chronic Pain Grade Scale (CPGS), Short Form-36 Bodily Pain Scale (SF-36 BPS), and Measure of Intermittent and Constant Osteoarthritis Pain (ICOAP). Arthritis Care Res. 2011, 63 Suppl 11, S240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchignoni, F.; Vercelli, S.; Giordano, A.; Sartorio, F.; Bravini, E.; Ferriero, G. Minimal Clinically Important Difference of the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand Outcome Measure (DASH) and Its Shortened Version (QuickDASH). J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2014, 44, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malavolta, E.A.; Yamamoto, G.J.; Bussius, D.T.; Assunção, J.H.; Andrade-Silva, F.B.; Gracitelli, M.E.C.; Ferreira Neto, A.A. Establishing Minimal Clinically Important Difference for the UCLA and ASES Scores after Rotator Cuff Repair. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. OTSR 2022, 108, 102894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louwerens, J.K.G.; van den Bekerom, M.P.J.; van Royen, B.J.; Eygendaal, D.; van Noort, A.; Sierevelt, I.N. Quantifying the Minimal and Substantial Clinical Benefit of the Constant-Murley Score and the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand Score in Patients with Calcific Tendinitis of the Rotator Cuff. JSES Int. 2020, 4, 606–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urwin, M.; Symmons, D.; Allison, T.; Brammah, T.; Busby, H.; Roxby, M.; Simmons, A.; Williams, G. Estimating the Burden of Musculoskeletal Disorders in the Community: The Comparative Prevalence of Symptoms at Different Anatomical Sites, and the Relation to Social Deprivation. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1998, 57, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roquelaure, Y.; Ha, C.; Leclerc, A.; Touranchet, A.; Sauteron, M.; Melchior, M.; Imbernon, E.; Goldberg, M. Epidemiologic Surveillance of Upper-Extremity Musculoskeletal Disorders in the Working Population. Arthritis Rheum. 2006, 55, 765–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brindisino, F.; Garzonio, F.; DI Giacomo, G.; Pellegrino, R.; Olds, M.; Ristori, D. Depression, Fear of Re-Injury and Kinesiophobia Resulted in Worse Pain, Quality of Life, Function and Level of Return to Sport in Patients with Shoulder Instability: A Systematic Review. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fitness 2023, 63, 598–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.-T.; Chiang, C.-F.; Wu, C.-H.; Huang, Y.-T.; Tu, Y.-K.; Wang, T.-G. Comparative Effectiveness of Injection Therapies in Rotator Cuff Tendinopathy: A Systematic Review, Pairwise and Network Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2019, 100, 336–349.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Zhang, H.; Wu, Q.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, T. Comparison of Three Common Shoulder Injections for Rotator Cuff Tears: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. J. Orthop. Surg. 2023, 18, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuelle, C.W.; Cook, C.R.; Stoker, A.M.; Cook, J.L.; Sherman, S.L. In Vivo Toxicity of Local Anesthetics and Corticosteroids on Supraspinatus Tenocyte Cell Viability and Metabolism. Iowa Orthop. J. 2018, 38, 107–112. [Google Scholar]

- Khoury, M.; Tabben, M.; Rolón, A.U.; Levi, L.; Chamari, K.; D’Hooghe, P. Promising Improvement of Chronic Lateral Elbow Tendinopathy by Using Adipose Derived Mesenchymal Stromal Cells: A Pilot Study. J. Exp. Orthop. 2021, 8, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.Z.; Ficklscherer, A.; Gülecyüz, M.F.; Paulus, A.C.; Niethammer, T.R.; Jansson, V.; Müller, P.E. Cell Toxicity in Fibroblasts, Tenocytes, and Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells—A Comparison of Necrosis and Apoptosis-Inducing Ability in Ropivacaine, Bupivacaine, and Triamcinolone. Arthroscopy 2017, 33, 840–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study name | N. patient | Follow-ups | Groups | Collagen used | Intervention | Scores at baseline | Scores at last follow-up | Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Kim et al. (2019) |

121 |

VAS: 3 days, 1 and 2 weeks KSS: 3, 12, 24 months |

Arthroscopic repair plus collagen injection (Group I, n=61) Arthroscopic repair alone (Group II, n=60). FTRCT |

3mL of 3% porcine type-I atelocollagen | Single injection at baseline (after arthroscopy) |

Group I VAS: 5.3 ± 2.1 KSS: 63.0 ± 15.1 Group II VAS: 6.3 ± 1.7 KSS: 61.5 ± 15.2 |

Group I VAS: 1.2 ± 1.0 KSS: 80.1 ± 9.4 Group II VAS: 3.2 ± 1.7 KSS:82.3 ± 11.2 |

Group I: 7 re-tears (11.5%) Group II: 4 re-tears (6.7%) |

|

Significant improvement in pre-op and last follow-up; VAS significantly better in Group I than Group II; No differences for KSS at final follow-up. |

||||||||

|

Kim et al. (2020) |

94 | 3, 12 and 24 months | 0.5 mL collagen injection (Group I, n=32) 1mL collagen injection (Group II, n=30) No injection (Group III, n=32) PTRCT |

0.5 or 1mL of 3%, porcine type-I atelocollagen | Single injection at baseline |

Group I VAS: 4.1 ASES: 61.9 CoS: 68.1 Group II VAS: 3.6 ASES: 63.5 CoS: 65.8 Group III VAS: 3.4 ASES: 62.9 CoS: 68.4 |

Group I VAS: 2.1 ± 1.2 ASES: 82.5 ± 12.3 CoS: 89.0 ± 6.9 Group II VAS: 1.4 ± 1.1 ASES: 79.3 ± 8.3 CoS: 82.0 ± 10.1 Group III VAS: 3.3 ± 2.5 ASES: 65.5 ± 8.5 CoS: 62.5 ± 11.5 |

Not reported |

|

Significant improvement pre-op and last follow-up only in Group I and II; Scores significantly better in Group I and II than III; No differences between Group I and II. |

||||||||

|

Chae et al. (2020) |

15 | 2 months | Collagen injection PTRCT |

1mL atelocollagen + 1mL of lidocaine | Single injection at baseline | ASES: 57.0 KSS: 64.6 CoS: 56.4 VAS: 4.2 SST: 6.6 FVAS: 6.3 |

ASES: 60.4 KSS: 68.5 CoS: 58.9 VAS: 3.7 SST: 6.9 FVAS: 7.1 |

Post-injection pain (57%, 8/15) |

| Significant improvement in pre-op and last follow-up only for SST and FVAS. | ||||||||

| Corrado et al. (2020) | 18 | 2 weeks, 1 and 3 months | Collagen injections RCTP |

2mL, porcine type-I atelocollagen | 4 injections (one a week for 4 weeks in a row) | CoS: 53.11 ± 12.7 DASH: 37.72 ± 19 |

CoS: 75 ± 12.9 DASH: 18.67 ± 13 |

Not reported |

| Statistically significant improvement. | ||||||||

|

Godek et al. (2022) |

82 | 6 weeks, 3 and 6 months | Collagen plus PRP injections (Group I, n=28) Collagen injections (Group II, n=27) PRP injections (Group III, n=27) PTRCT |

2mL, porcine type-I atelocollagen | 3 injections (one a week for 3 weeks in a row) |

Group I VAS: 74% QuickDASH: 37 NRS: 5 Group II VAS: 68% QuickDASH: 42 NRS: 5,5 Group III VAS: 71% QuickDASH: 41 NRS: 6 |

Group I VAS: 82% QuickDASH: 15 NRS: 1,5 Group II VAS: 80% QuickDASH: 20 NRS: 2 Group III VAS. 86% QuickDASH: 20 NRS: 1,8 |

No complications |

| No differences between groups at final follow-up. | ||||||||

| Aldhafian et al. (2023) | 129 | 3, 6 and 12 months for all groups Last follow-up (months): Group I: 21.6±5.1 Group II: 20±6.3 Group III: 18.3±3.2 |

Arthroscopic repair only (Group I, n=36) Arthroscopic repair plus collagen injection (Group II, n=44) Arthroscopic repair with acellular dermal matrix allograft injection (Group III, n=49) FTRCT |

1ml atelocollagen | Single injection at baseline (after arthroscopy) |

Group I VAS: 4 ASES: 58 CoS: 62 KSS: 61 Group II VAS: 4 ASES: 61 CoS: 68 KSS: 68 Group III VAS: 4 ASES: 62 CoS: 68 KSS: 68 |

Group I VAS: 2 ASES: 80 CoS: 76 KSS: 75 Group II VAS: 3 ASES: 74 CoS: 79 KSS: 81 Group III VAS: 3 ASES: 76 CoS: 73 KSS: 73 |

Re-tear rates after 12 months: Group I: 19.4% (7 of 36) Group II: 13.6% (6 of 44) Group III: 20.4% (10 of 49) Adverse events were not detected in any groups. |

|

Improved in all 3 groups compared to preoperative assessment at final follow-up. No significant difference among the 3 groups. |

||||||||

|

Buda et al. (2023) |

71 | 1 and 6 months | Collagen injections Group I (SST<42, n=23) Group II (43< SST<74, n=28) Group III (SST>75, n=20) RCTP |

4mg/2ml, bovine collagen, low molecular weight (<3kDa) | 2 injections (one at baseline and one between nine and 17 days after the first one) |

Overall population VAS at rest: 4.25 ± 3.10 VAS during movement: 6.56 ± 1.47 VAS at night: 5.33 ± 2.98 CoS: 63.76 ± 12.50 SST: 54.14 ± 20.16 Group I VAS at rest: 6.35 ± 2.29 VAS during movement: 7.26 ± 4.09 VAS at night: 6.56 ± 4.48 CoS: 51.52 ± 59.17 SST: 30.43 ± 40.58 Group II VAS at rest: 4.28 ± 2.07 VAS during movement: 6.57 ± 3.96 VAS at night: 5.03 ± 3.04 CoS: 65.32 ± 74.10 SST: 56.79 ± 72.58 Group III VAS at rest: 1.90 ± 0.95 VAS during movement: 5.85 ± 4.30 VAS at night: 4.55 ± 2.75 CoS: 75.1 ± 81.85 SST: 77.49 ± 81.24 |

Overall population VAS at rest: 0.39 ± 0.77 VAS during movement: 1.87 ± 1.85 VAS at night: 0.7 ± 1.32 CoS: 84.07 ± 11.47 SST: 87.15 ± 14.99 Group I VAS at rest: 0.86 ± 0.99 VAS during movement: 1.77 ± 1.87 VAS at night: 0.91 ± 1.27 CoS: 75.10 ± 10.06 SST: 77.27 ± 16.7 Group II VAS at rest: 0.18 ± 0.56 VAS during movement: 1.89 ± 1.82 VAS at night: 0.59 ± 1.15 CoS: 85.37 ± 10.24 SST: 90.74 ± 13.34 Group III VAS at rest: 0.15 ± 0.49 VAS during movement: 1.9 ± 1.97 VAS at night: 0.65 ± 1.63 CoS: 92.45 ± 7.19 SST: 94.18 ± 7.69 |

No complications |

| Significant improvement in the overall population and Group I, no differences in Group II and III. | ||||||||

| References | Study size | Follow-up | N procedures | Type of study | Diagnostic certainty | Description of injection technique | Rehabilitation and compliance | Outcome criteria | Outcome assessment | Selection process | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kim et al 2019 | 10 | 4 | 7 | 0 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 12 | 5 | 68 |

| Kim et al 2020 | 7 | 4 | 7 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 12 | 5 | 75 |

| Chae et al 2020 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 12 | 5 | 57 |

| Corrado et al 2020 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 12 | 5 | 52 |

| Godek et al 2022 | 7 | 0 | 7 | 15 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 12 | 5 | 71 |

| Aldhafian et al 2023 | 10 | 4 | 10 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 12 | 5 | 54 |

| Buda et al. 2023 | 7 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 10 | 12 | 5 | 76 |

| Maximum Score Possible | 10 | 10 | 10 | 15 | 5 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 15 | 10 | 100 |

| Mean ± Standard Deviation | 5,8 ± 4,2 | 1,7 ± 2,1 | 8,7 ± 1,6 | 5 ± 6,4 | 5 ± 0 | 7,1 ± 2.6 | 4,2 ± 1,8 | 10 ± 0 | 12 ± 0 | 5 ± 0 | 63,3 ± 8,9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).