1. Introduction

Despite its clinical relevance, enthesopathy often remains unrecognized, frequently overshadowed by more commonly diagnosed joint conditions such as arthritis. Enthesopathy is a broad term for pathologies that include ligament and tendinous injuries (Alverez, 2023). Repetitive mechanical stress, inflammatory responses, and micro-tearing of the local area can lead to a loss of fibrillar structure and changes in the integrity of the collagen matrix, which contribute to the thickening of the entheses (Alverez, 2023). One of the most common enthesopathies is tendinopathy, which is associated with damaged and diseased tendons (Millar, 2021). Tendinopathy abnormalities occur in the microstructure of the tendon, disrupting the structural integrity of the collagen matrix, leading to fragmented collagen fibers and disorganized collagen bundles (Millar, 2021). One condition that exemplifies these degenerative changes is posterior tibial tendon dysfunction (PTTD), a debilitating tendinopathy affecting the medial ankle. Around 3.3% of the US population has PTTD, with the percentage increasing to 10% for obese women or women who are over the age of 40 (Poppen, 2021). The posterior tibialis tendon terminates in plantar, main, and recurrent branches that insert into the navicular tuberosity, medial cuneiform, sustentaculum tali of the calcaneus, and the bases of the metatarsals, functioning to stabilize the medial longitudinal arch and invert the midfoot (Ikpeze, 2019). The posterior tibialis tendon functions both as a plantar flexor and an inverter of the foot, which are special movements specific to the foot (Flores, 2019). Posterior tibial tendon dysfunction (PTTD) defines chronic strain that degenerates the tendon behind and around the inner part of the ankle and causes inflammation (Park, 2020). With tendinosis, collagen degenerates in the tendon in response to chronic overuse (Jaworski, 2022). Common symptoms of PTTD include pain behind the ankle, swelling, difficulty walking or standing, arch collapse, and tissue degeneration (Park, 2020; Ling, 2017). These symptoms can lead to chronic microtrauma, flattening of the foot, hindfoot valgus, degeneration at the subtalar joint, and even arthritis (Park, 2020; Jaworski, 2022). The risk factors of PTTD include conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, obesity, previous surgery, foot/ankle trauma, steroid use, and seronegative arthropathies (Bubra, 2015). PTTD's risk factors and symptoms increase the need for a noninvasive procedure to aid the body in the repair process.

The determination of whether noninvasive or invasive procedures should be recommended depends on the severity of PTTD. Severity can be classified into four stages according to the Johnson and Strom classification modified by Myerson (Abousayed, 2015). Stage I is defined by mild pain along the medial aspect of the ankle with characteristics of swelling, fullness, and tenderness (Abousayed, 2015). No deformity is present in the first stage. The first stage recommends conservative management using a walking boot, physical therapy, and orthotics for around 3-4 months (Knapp, 2024). Stage II characterizes PTTD with moderate pain localized along a longer segment of the tendon (Abousayed, 2015). Stage II is the first stage to present deformity of the posterior tibial tendon, showing elongation of the tendon and pronounced swelling, fullness, and tenderness (Abousayed, 2015). PTTD in Stage II uses immobilization and physical therapy with orthotics. Still, if conservative measures fail, surgical treatment such as a medial calcaneal osteotomy with posterior tendon debridement and repair is recommended (Knapp, 2024). Stage III describes severe pain that can be evident on the lateral foot at the sinus tarsi in addition to the medial arch (Abousayed, 2015). Elongation and disruption of the posterior tibial tendon are also present. This stage utilizes the same conservative therapies as Stages I and II, but it predominantly warrants surgical treatment such as medial double arthrodesis or triple arthrodesis because of rearfoot arthritic changes (Knapp, 2024). Stage IV presents PTTD with valgus deformity of the ankle and can sometimes be associated with lateral tibiotalar arthritis (Abousayed, 2015). Stage IV is further classified into type A, which is characterized by flexible ankle deformity, or type B, described with fixed deformity of the ankle (Abousayed, 2015). Individuals diagnosed with Stage IV PTTD often require surgery because of severe degeneration of the tendons in the ankle and rearfoot (Knapp, 2024). These surgeries include, but are not limited to, total ankle arthroplasty with replacement, deltoid ligament reconstruction, and triple arthrodesis with Achilles tendon lengthening (Knapp, 2024). PTTD surgery triple arthrodesis can lead to many complications, such as early osteoarthritis in the ankle joint, hardware failure, infection, and wound dehiscence (Chambers, 2023). The lack of successive measures taken to prevent complications or even treat PTTD prompts the importance of future research for low-risk interventions for suffering patients.

The existing noninvasive methods for PTTD do not resolve the underlying problem of tendon degeneration and deformity, prompting the necessity of alternative approaches that could improve patient care. The patients in this case series all had evidence of structural degeneration of the posterior tibial tendon and had failed at least three months of standard conservative care. Before considering surgical intervention, patients were offered a regenerative medicine alternative with connective tissue transplantation. Wharton’s jelly (WJ) is primarily comprised of several different collagen fiber types, specifically types I, II, III, and V, cytokines, growth factors, and hyaluronic acid (Gupta, 2020; Main, 2021). The most abundant collagen type in tendons is collagen I, which represents 95% of the matrix, while types III and V represent the remaining 5% (Tresoldi, 2013). The collagen matrix of WJ is comparable to the collagen matrix of tendons, making WJ a homologous tissue that has sufficient composition to replace damaged tissue. Due to its structural similarity to multiple native tissues, WJ is clinically applicable in various homologous anatomical sites. A recent publication on the application of WJ to damaged tendons and ligaments in the rotator cuff displays significant patient improvements in a similar use site (Lai, 2024). The study demonstrated favorable outcomes in the cohort, with patients reporting improvements in pain and function, promoting overall well-being (Lai, 2024). The need for alternative interventions with evidence of long-term improvements for posterior tibial tendon insufficiency is vital to increase the efficacy and safety of patient care. This preliminary observational study aims to observe the homologous use and efficiency of Wharton’s jelly tissue allografts applied to structural defects in the posterior tibial tendon.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design

The observational repository data have been collected following the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, with approval from the Institutional Review Board of the Institute of Regenerative and Cellular Medicine (IRCM-2021-311) since 2021. The details of the repository design and WJ allograft processing can be found in other published works derived from the database (Davis, 2022; Lai, 2024-knee). This analysis of observational data included only complete data sets from patients who received WJ allografts to the posterior tibial tendon. No exclusions were made based on gender, age, BMI, or level of initial score.

Study Population

The participant group includes 26 patients, 62% male and 38% female. Based on the severity of the defect and perceived patient pain, twenty-two patients received a single application, and six patients received two applications. Patient demographics are displayed in

Table 1.

Case presentation

Patients displayed Posterior Tibial Tendinosis symptoms at their initial consultation, which included micro-tearing on the arch, calf tightness, Achilles tightness, tissue damage, and tendon strain. All patients, defined by the Johnson and Strom classification with modification from Myerson, had PTTD in Stage II, III, or IV with evidence of structural degeneration of the tendon. Before considering the Wharton’s jelly application, patients underwent conservative care, receiving physical therapy, shoe modifications, orthotics, and bracing. The patients who opted for Wharton’s jelly allograft had failed at least three months of conservative care.

Patient Care Procedures

Prior to the Wharton’s jelly application, patients received an MRI to assess the level of tissue damage. To further confirm the site of degeneration, the patients underwent a palpation and then an ultrasound to locate the deteriorating area. The patients were then injected with two cc of local anesthesia into the affected area via a 25-gauge needle under ultrasound guidance. When the area was fully prepped, the Wharton’s jelly allograft was applied to the defects with a 25-gauge needle under ultrasound guidance. Following the procedure, the patients waited thirty minutes in the office to evaluate any reactions. No adverse reactions were reported. The aftercare included restrictions on icing and anti-inflammatories for six weeks, and the patients were placed in either a boot or a brace. After two weeks, if the patients showed progress, the bracing was removed and they could resume regular activities. Eight patients obtained one additional application of the Wharton’s jelly allograft due to the level of deterioration, and continued 30-day and 90-day follow-ups, with five patients even receiving 120-day follow-ups. At each follow-up, patients filled out QOLS, NPRS, and WOMAC scales to monitor their progress.

3. Results

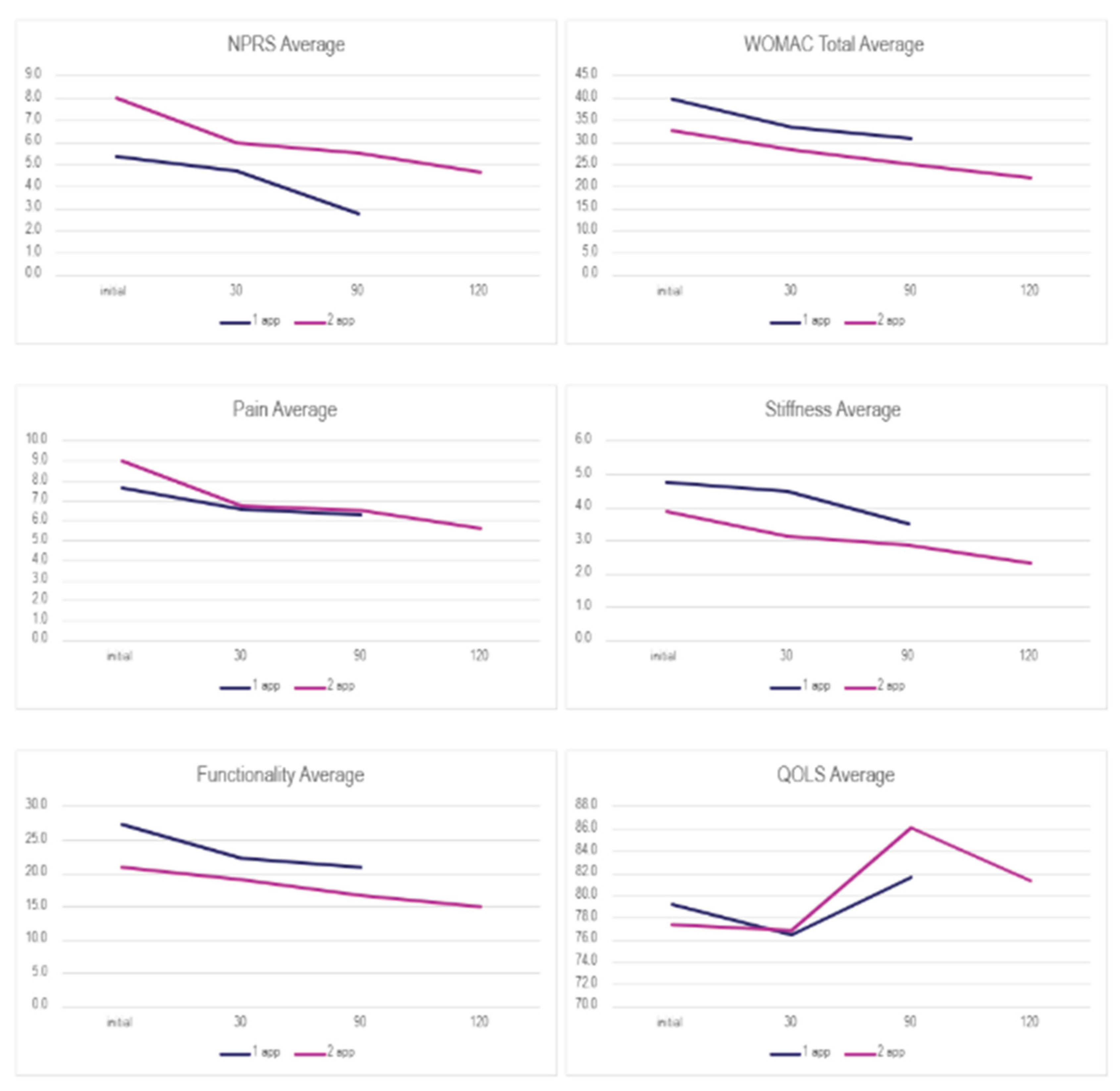

To understand the results, one must note that a lower NPRS and WOMAC score corresponds to positive change, but a higher QOLS score reflects improvement. Thirty patients were analysed based on the number of applications. All patients demonstrated a consistent reduction in the NPRS and WOMAC scores across all follow-up visits, regardless of the number of applications. In comparison, the QOLS scores between each category fluctuated. For patients with two applications, participants showed a notable decline in QOLS scores. Patients with single applications experienced an increase in QOLS scores from the 30-day to the 90-day follow-up. The percent improvement for each category is presented in

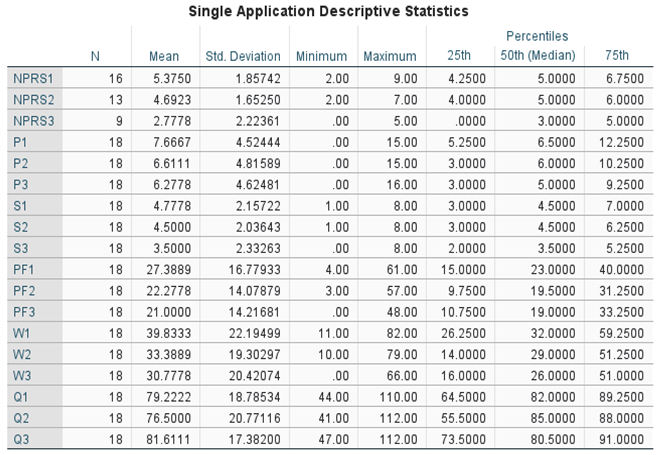

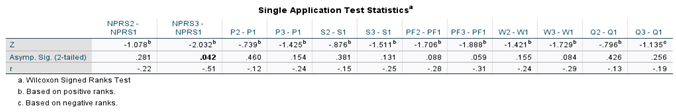

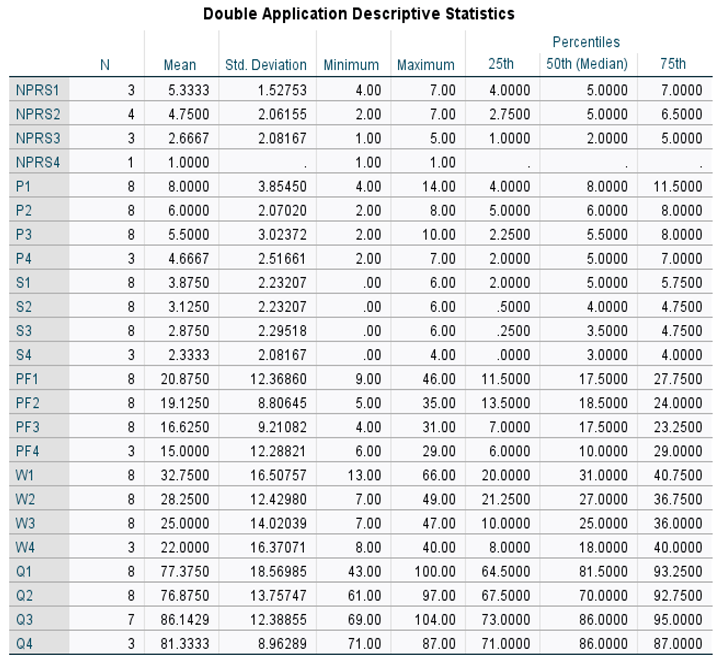

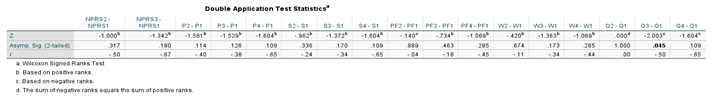

Table 2. The Wilcoxon Signed-rank test was performed on both application groups between the initial and 30-day visits, initial and 90-day visits, and the initial and 120 visits for the double application group. The small sample size presents limitations in the statistical strength of the test results; however, several categories displayed significant changes in scores. Descriptive and test statistics for each application group can be found in

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6 and

Table 7. The legend used to label all tables is shown in

Table 3. The evaluation of the mean scores between the two subgroups is visualized in

Figure 2, showing common patterns of decreasing scores in both groups.

Table 2.

Percent improvement in each scale by number of applications from the initial to the final visit.

Table 2.

Percent improvement in each scale by number of applications from the initial to the final visit.

| Scale |

1 app (90 Days) |

2 app (120 Days) |

| NPRS |

48.32% |

81.25% |

| WOMAC Total |

22.73% |

32.82% |

| Pain |

18.12% |

41.67% |

| Stiffness |

26.74% |

39.78% |

| Functionality |

23.33% |

28.14% |

| QOLS |

3.02% |

5.12% |

Table 3.

This table provides a legend for the labeling used on all other tables.

Table 3.

This table provides a legend for the labeling used on all other tables.

| Variable |

Label |

| NPRS |

Numerical Pain Rating Scale |

| P |

WOMAC - Pain |

| S |

WOMAC - Stiffness |

| PF |

WOMAC - Physical Function |

| W |

WOMAC – Total |

| Q |

Quality of Life Scale |

| 1 |

Initial visit |

| 2 |

30 day visit |

| 3 |

90 day visit |

| 4 |

120 day visit |

Table 4.

Descriptive Statistics for single application patients.

Table 4.

Descriptive Statistics for single application patients.

Table 5.

Test Statistics for single application patients.

Table 5.

Test Statistics for single application patients.

Table 6.

Descriptive Statistics for double application patients.

Table 6.

Descriptive Statistics for double application patients.

Table 7.

Test Statistics for double application patients.

Table 7.

Test Statistics for double application patients.

4. Discussion

The results of this research study demonstrate the clinical benefits of applying 150 mg WJ tissue allografts to supplement and support tissue defects associated with posterior tibial tendon degeneration cases that were unresponsive to standard-of-care interventions. Each application group reported improvements in NPRS and WOMAC scores, presenting notable improvements in all categories and contributing to better general health.

Table 2 displays the overall rate of improvement in both application categories. Patients who received a single application reported a 2-point reduction in NPRS and a 9-point reduction in total WOMAC from the initial date to the 90-day visit. For the single application group, a Wilcoxon signed rank test revealed the most significant improvement occurred between the initial NPRS score (Md = 5, n = 16) and the final NPRS score (Md = 3, n = 9), z = 2.03, p = 0.042, with a strong effect size, r = -0.51 (

Table 4 and

Table 5). For patients with two applications, NPRS decreased by 2 points and WOMAC (total) by 11.2 points between the initial application and the 120-day visit. The Wilcoxon signed rank test revealed improvements were significant in the QOLS scores with an initial score (Md = 81.5, n = 8), and the 90-day score (Md = 86, n = 7), z = 2.00, p = 0.045, with a strong effect size, r = -0.50 (

Table 6 and

Table 7). The second application group reported a greater improvement in scores, but a larger sample size is needed to confirm the statistical significance. This study lacks a direct comparison with a control group or other conventional interventions, such as platelet-rich plasma (PRP) therapy, another common regenerative intervention.

The outcomes of this study provide positive data for the clinical application of WJ in posterior tibial tendon degeneration. The collagenous framework of the posterior tibial tendon consists predominantly of collagen type I fibers, with minor compositions of collagen III and V (Tresoldi, 2013). These matrices are arranged in organized bundles with crosslinking collagen fibers parallel to the tendon axis (Bordoni, 2024; Screen, 2016). Failure to maintain these collagen-rich matrices changes the morphology of the tendon, allowing for the thickening of the tendon, stiffness, pain, inflammation, instability, and the increased risk of tendinopathy (Screen, 2016). The patient results from WJ tissue allografts applied to the posterior tibial tendon provide preliminary evidence for the clinical potential of WJ in homologous use sites. WJ consists of rich concentrations of collagen types I, II, III, and V, with other beneficial extracellular matrix components (Gupta, 2020; Main, 2021). The tissue matrix of WJ offers protection from tensile stress and cushioning of the umbilical cord, mirroring critical functions of tendons in maintaining joint movement and withstanding mechanical stress (Gupta, 2020; Screen, 2016). WJ tissue allografts can successfully be used to supplement cases of posterior tibial tendon degeneration, allowing for healthy collagen structures to interlock with the native matrices.

This study models the clinical protocol of applying WJ tissue allografts in patients with treatment-resistant posterior tibial tendon degeneration, as well as patient outcomes. This study provides preliminary evidence of novel regenerative medicine protocols for practicing physicians seeking alternative conservative care options, in order to avoid postoperative risks and complications of surgery. Standard surgical procedures for individuals with posterior tibial tendons degeneration include joint-sparing reconstruction methods such as lateral column lengthening and medial displacement calcaneal osteotomy, which have not been reported as preferred methods of managing posterior tibial tendon degeneration, according to current literature and the physicians who conducted this study (Whitelaw, 2022; Day, 2020). Postoperative complications often include thromboembolic events, infection, wound dehiscence, neurologic injury, and painful hardware, either individually or in combination (Knapp, 2024). In light of the postoperative complications, current literature has expanded to observe other conservative regenerative methods. Alongside WJ tissue allografts, platelet-rich plasma (PRP) therapy, an autologous regenerative intervention, has garnered substantial clinical interest; however, recent studies underscore its inconsistent effectiveness and the lack of standardized treatment protocols (Lu, 2023). The use of PRP in tendon degeneration has implicated negative outcomes in current literature (Pretorious, 2023). Additionally, adverse events have been reported with the use of PRP therapy in various use sites (Arita, 2024). In this study, preliminary evidence of consistent results within the cohort was shown for WJ allografts in supplementing tendinopathy. The integration of this particular regenerative medicine has been demonstrated in other use sites such as rotator cuff tears, hip and knee osteoarthritis, and sacroiliac cartilagenous defects (Lai-RC, 2024; Lai-hip, 2024; Davis, 2022; Lai, 2023). Results from each study have demonstrated increases in functionality with decreases in pain and stiffness.

The structural and functional parallels between WJ and the posterior tibial tendon discussed in this observational study demonstrate that the application of WJ tissue allografts to homologous use sites is a promising alternative to current conventional care. WJ may help circumvent the need for operative management by facilitating earlier intervention and promoting the preservation of native tendon morphology. Future research will be instrumental in validating the clinical potential of WJ in its application to refractory posterior tibial tendon degeneration.

5. Conclusions

This observational research study had a patient group of 30 individuals with two dosage levels that reported pain alleviation and improved physical function. No adverse effects or complications were recorded in this cohort. The expansion of recent studies investigating alternative medicine reflects a growing body of evidence regarding the complications and risks of standard surgical interventions, prompting an increased interest in regenerative practices. This preliminary study warrants further research in implementing alternative methods into current standard-of-care procedures and incorporating Wharton’s jelly as an option for posterior tibial tendon degeneration.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.B., G.K., J.S., and T.B.; methodology, B.B., G.K.; software, T.B.; validation, N.L., A.L., E.C., and T.B.; formal analysis, N.L., A.L., and E.C.; investigation, B.B., G.K., J.S., N.L., A.L., and E.C.; resources, N.L., and A.L..; data curation, B.B., G.K., J.S., N.L., A.L., and E.C.; writing—original draft preparation, N.L., A.L., and E.C.; writing—review and editing, B.B., G.K., J.S., N.L., A.L., E.C., and T.B visualization, B.B., G.K., and T.B.; supervision, J.S. (John Shou) and T.B.; project administration, T.B.; funding acquisition, B.B., G.K., J.S., and T.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This data was collected in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Institute of Regenerative and Cellular Medicine (protocol code IRCM-2022-311; Approval date: 9 June 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the staff at each clinic that submitted data to the repository for their assistance in data collection and submission.

Conflicts of Interest

John Shou is the principal investigator of the retrospective repository at Regenative Labs. Naomi Lambert, Alexis Lee, Eva Castle, and Tyler Barrett are associated with Regenative Labs. Regenerative Labs was involved in the design of the study, data analysis, and writing. Regenative Labs influenced the decision to publish.

References

- Alvarez A, Tiu TK. Enthesopathies. [Updated 2023 Jun 5]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559030/.

- Millar NL, Silbernagel KG, Thorborg K, et al. Tendinopathy [published correction appears in Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021 Feb 3;7(1):10. [CrossRef]

- Poppen O, Feder P, Gorman C. STAGE III POSTERIOR TIBIAL TENDONITIS AND DYSFUNCTION LEADING TO ACQUIRED FLAT FOOT IN A 49-YEAR-OLD MALE. JCC. 2021;4(1):107-111.

- Ikpeze TC, Brodell JD Jr, Chen RE, Oh I. Evaluation and Treatment of Posterior Tibialis Tendon Insufficiency in the Elderly Patients. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil. 2019;10:2151459318821461. Published 2019 Jan 24. [CrossRef]

- Flores DV, Mejía Gómez C, Fernández Hernando M, Davis MA, Pathria MN. Adult Acquired Flatfoot Deformity: Anatomy, Biomechanics, Staging, and Imaging Findings. Radiographics. 2019;39(5):1437-1460. [CrossRef]

- Park S, Lee J, Cho HR, Kim K, Bang YS, Kim YU. The predictive role of the posterior tibial tendon cross-sectional area in early diagnosing posterior tibial tendon dysfunction. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(36):e21823. [CrossRef]

- Jaworski Ł, Zabrzyńska M, Klimaszewska-Wiśniewska A, Zielińska W, Grzanka D, Gagat M. Advances in Microscopic Studies of Tendinopathy: Literature Review and Current Trends, with Special Reference to Neovascularization Process. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022; 11(6):1572. [CrossRef]

- Ling SK, Lui TH. Posterior Tibial Tendon Dysfunction: An Overview. Open Orthop J. 2017;11:714-723. Published 2017 Jul 31. [CrossRef]

- Bubra PS, Keighley G, Rateesh S, Carmody D. Posterior tibial tendon dysfunction: an overlooked cause of foot deformity. J Family Med Prim Care. 2015;4(1):26-29. [CrossRef]

- Abousayed MM, Tartaglione JP, Rosenbaum AJ, Dipreta JA. Classifications in Brief: Johnson and Strom Classification of Adult-acquired Flatfoot Deformity. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474(2):588-593. [CrossRef]

- Knapp PW, Constant D. Posterior Tibial Tendon Dysfunction. [Updated 2024 May 21]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK542160/.

- Chambers AR, Dreyer MA. Triple Arthrodesis. [Updated 2023 Jun 5]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551713/.

- Gupta A, El-Amin SF 3rd, Levy HJ, Sze-Tu R, Ibim SE, Maffulli N. Umbilical cord-derived Wharton's jelly for regenerative medicine applications. J Orthop Surg Res. 2020;15(1):49. Published 2020 Feb 13. [CrossRef]

- Main BJ, Maffulli N, Valk JA, et al. Umbilical Cord-Derived Wharton's Jelly for Regenerative Medicine Applications: A Systematic Review. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2021;14(11):1090. Published 2021 Oct 27. [CrossRef]

- Tresoldi I, Oliva F, Benvenuto M, et al. Tendon's ultrastructure. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2013;3(1):2-6. Published 2013 May 21. [CrossRef]

- Lai A, Tamea C, Shou J, Okafor A, Sparks J, Dodd R, Woods C, Lambert N, Schulte O, Barrett T. Safety and Efficacy of Wharton’s Jelly Connective Tissue Allograft for Rotator Cuff Tears: Findings from a Retrospective Observational Study. Biomedicines. 2024; 12(4):710. [CrossRef]

- Lai A, Tamea C, Shou J, Okafor A, Sparks J, Dodd R, Lambert N, Woods C, Schulte O, Kovar S, et al. Retrospective Evaluation of Cryopreserved Human Umbilical Cord Tissue Allografts in the Supplementation of Cartilage Defects Associated with Hip Osteoarthritis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(14):4040. [CrossRef]

- Davis JM, Sheinkop MB, Barrett TC. Evaluation of the Efficacy of Cryopreserved Human Umbilical Cord Tissue Allografts to Augment Functional and Pain Outcome Measures in Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis: An Observational Data Collection Study. Physiologia. 2022; 2(3):109-120. [CrossRef]

- Bordoni B, Black AC, Varacallo MA. Anatomy, Tendons. [Updated 2024 May 1]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513237/.

- Screen HR, Berk DE, Kadler KE, Ramirez F, Young MF. Tendon functional extracellular matrix. J Orthop Res. 2015;33(6):793-799. [CrossRef]

- Whitelaw K, Shah S, Hagemeijer NC, Guss D, Johnson AH, DiGiovanni CW. Fusion Versus Joint-Sparing Reconstruction for Patients With Flexible Flatfoot. Foot Ankle Spec. 2022;15(2):150-157. [CrossRef]

- Day J, Kim J, Conti MS, Williams N, Deland JT, Ellis SJ. Outcomes of Idiopathic Flexible Flatfoot Deformity Reconstruction in the Young Patient. Foot Ankle Orthop. 2020;5(3):2473011420937985. Published 2020 Aug 20. [CrossRef]

- Lu J, Li H, Zhang Z, Xu R, Wang J, Jin H. Platelet-rich plasma in the pathologic processes of tendinopathy: a review of basic science studies. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2023;11:1187974. Published 2023 Jul 21. [CrossRef]

- Pretorius J, Habash M, Ghobrial B, Alnajjar R, Ellanti P. Current Status and Advancements in Platelet-Rich Plasma Therapy. Cureus. 2023;15(10):e47176. Published 2023 Oct 17. [CrossRef]

- Arita A, Tobita M. Adverse events related to platelet-rich plasma therapy and future issues to be resolved. Regen Ther. 2024;26:496-501. Published 2024 Jul 20. [CrossRef]

- Lai A, Tamea C, Shou J, Okafor A, Sparks J, Dodd R, Woods C, Lambert N, Schulte O, Barrett T. Safety and Efficacy of Wharton’s Jelly Connective Tissue Allograft for Rotator Cuff Tears: Findings from a Retrospective Observational Study. Biomedicines. 2024; 12(4):710. [CrossRef]

- Lai A, Shou J, Traina SA, Barrett T. The Durability and Efficacy of Cryopreserved Human Umbilical Cord Tissue Allograft for the Supplementation of Cartilage Defects Associated with the Sacroiliac Joint: A Case Series. Reports. 2023; 6(1):12. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).