1. Introduction

The commonality of knee and hip osteoarthritis (OA) masks the significance of the less common OA pathology, ankle OA. While only affecting 1% of the world population, ankle OA is equally as disabling as other OA pathologies, profoundly affecting the quality of life for those suffering from it (Perez 2022). The hallmark of ankle OA is its connection to ankle instability, suggesting that the condition can arise from various etiologies. In most cases of ankle OA, the condition is caused by damaged cartilage in the ankle joint, with 75-80% of cases due to traumatic events and only 7-9% being of an unknown cause (Perez 2022). Although ankle OA is commonly diagnosed after post-traumatic injuries, factors such as aging, obesity, genetic predisposition, metabolic syndrome, and hormone profiles are prevalent in those at risk for ankle OA (He 2020). A retrospective study performed by Kurokawa (2023) found that smoking, comorbidity of other joint diseases, and high BMI rates also increase the progression of ankle OA (Kurokawa 2023). Ankle osteoarthritis manifests through reduced muscle strength, limited dorsiflexion, diminished ambulatory function, joint discomfort, and stiffness, resulting in an increased sedentary lifestyle and decreased overall quality of life (Al-Mahrouqi 2020). To alleviate patient suffering in ankle OA, the current standard of care procedures encompasses conservative and non-conservative approaches.

When approaching ankle OA intervention, conservative care is recommended before any surgical options are considered. The first step in conservative care for ankle OA relies on nonpharmacological strategies, including physical therapy, lifestyle changes, and orthotics. If symptoms cannot be effectively controlled by nonpharmacological measures, pharmacological measures, including NSAIDs, corticosteroids, and viscosupplementation, are employed (Tejero 2021). However, current conservative care focuses on immediate symptomatic relief and does not address the damaged cartilage at the root of ankle OA. Surgical approaches are considered after failed management with conservative care. The choice of surgical method for ankle osteoarthritis, whether joint-preserving or joint-sacrificing, depends on the severity of the condition (Perez 2020). Complications remain a concern for both types of surgical procedures. After undergoing ankle surgery, patients often face surgical site infections (SSIs), necrosis of the soft tissue, malunion, nonunion, muscular atrophy, and pain (Vanderkarr 2022). A data analysis by Vanderkarr (2022) reported that 30-40% of patients experienced continuous postoperative pain, and 10% of patients underwent a secondary procedure (Vanderkarr 2022). In addition to the various surgical complications in ankle surgery, an economic burden is evident. In 2011, Medicare spent $11 billion on the foot and ankle subspecialty (Glasser 2025). Phillips (2017) observed from his retrospective comparison between inpatient and outpatient procedures that the mean direct cost for each patient for operative fixation was $11,466 for inpatient and $3,111 for outpatient procedures (Phillips 2017). Since 2017, the progressive increase in inflation has been accompanied by a corresponding rise in the cost of surgical interventions. The limited substantial evidence regarding the optimal intervention for ankle OA underscores the critical need for future research focused on cost-effective and low-risk strategies to alleviate patient suffering.

Current literature concerning conservative care for ankle OA focuses on temporary symptomatic relief, highlighting the need for alternative interventions. One rapidly emerging alternative to the current standard of care approaches is Wharton’s Jelly (WJ) tissue allografts. This umbilical cord-derived structural matrix contains various types of collagen, specifically types I, II, III, and V, cytokines, growth factors, and hyaluronic acid (Gupta 2020, Main 2021). The structural composition of Wharton’s jelly shares similarities with human cartilage, predominantly consisting of collagen type I, with smaller proportions of collagen types III and V (Ouyang 2023). Beyond its structural similarities, Wharton’s jelly serves a protective role by providing cushioning and mechanical support to the cord, akin to the functional properties of human cartilage (Lin 2020). A study performed by Gupta (2023) observed that applications of WJ to the ankle demonstrated positive outcomes in pain and function. Another study by Davis (2022) analyzed the use of WJ in knee OA, identifying significant increases in quality of life and pain improvement (Davis 2022). Analysing the utilization of WJ to replace the degenerated cartilage present in ankle OA cases is essential for advancing the existing standard of care, given its structural and functional similarities. This case series reports positive preliminary findings from patients who received Wharton’s jelly tissue allografts for intra-articular ankle degeneration.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

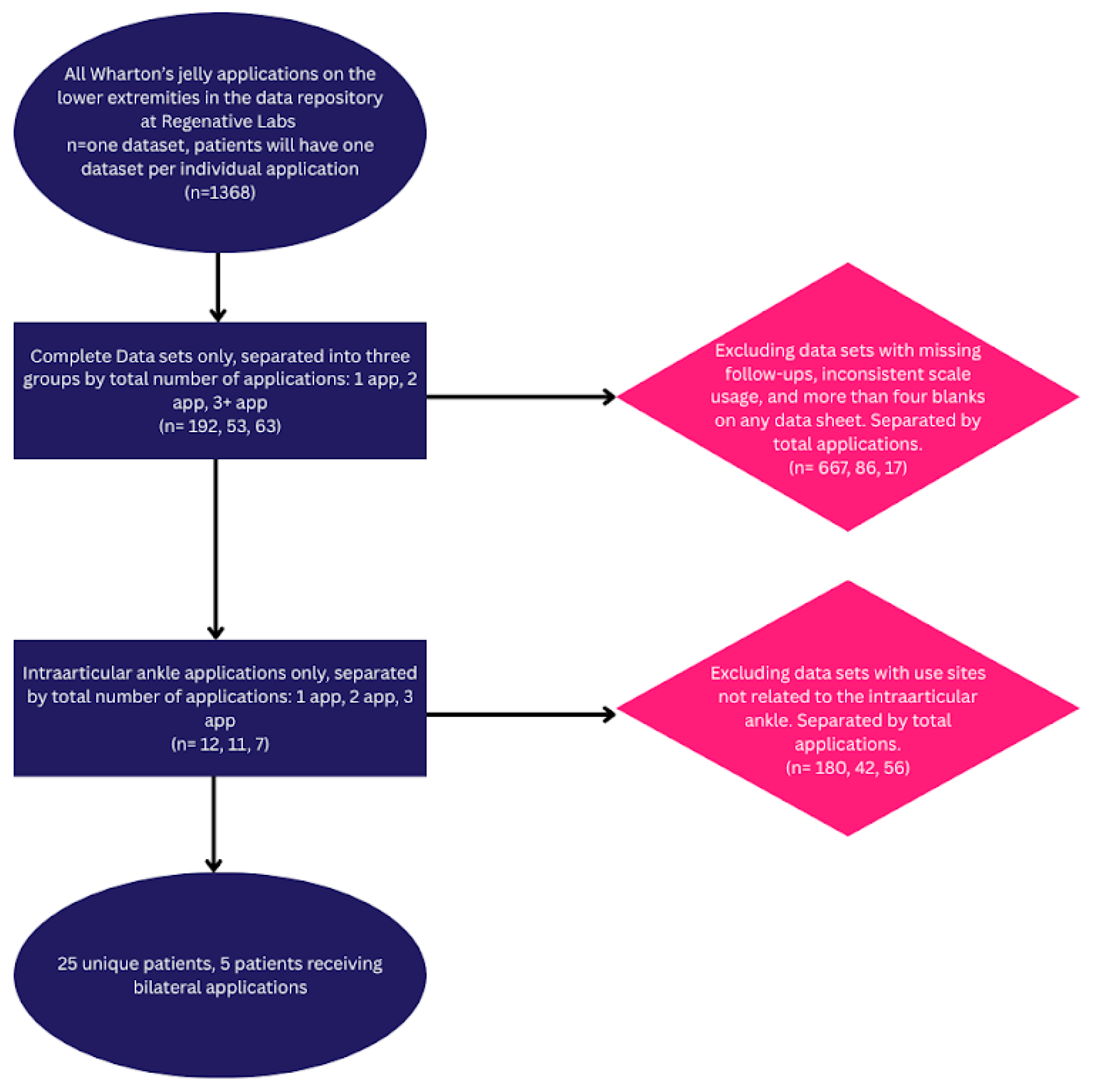

The observational repository at Regenative Labs was used to identify the patients analyzed in this paper. The data repository is collected following the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. It has maintained approval from the Institutional Review Board of the Institute of Regenerative and Cellular Medicine (IRCM-2021-311) since May 2021. The details of the repository design can be found in other published works derived from the database (hip, RC). The inclusion and exclusion criteria can be found in the study flowchart below (

Figure 1).

Figure 1.

2.2. Study Population

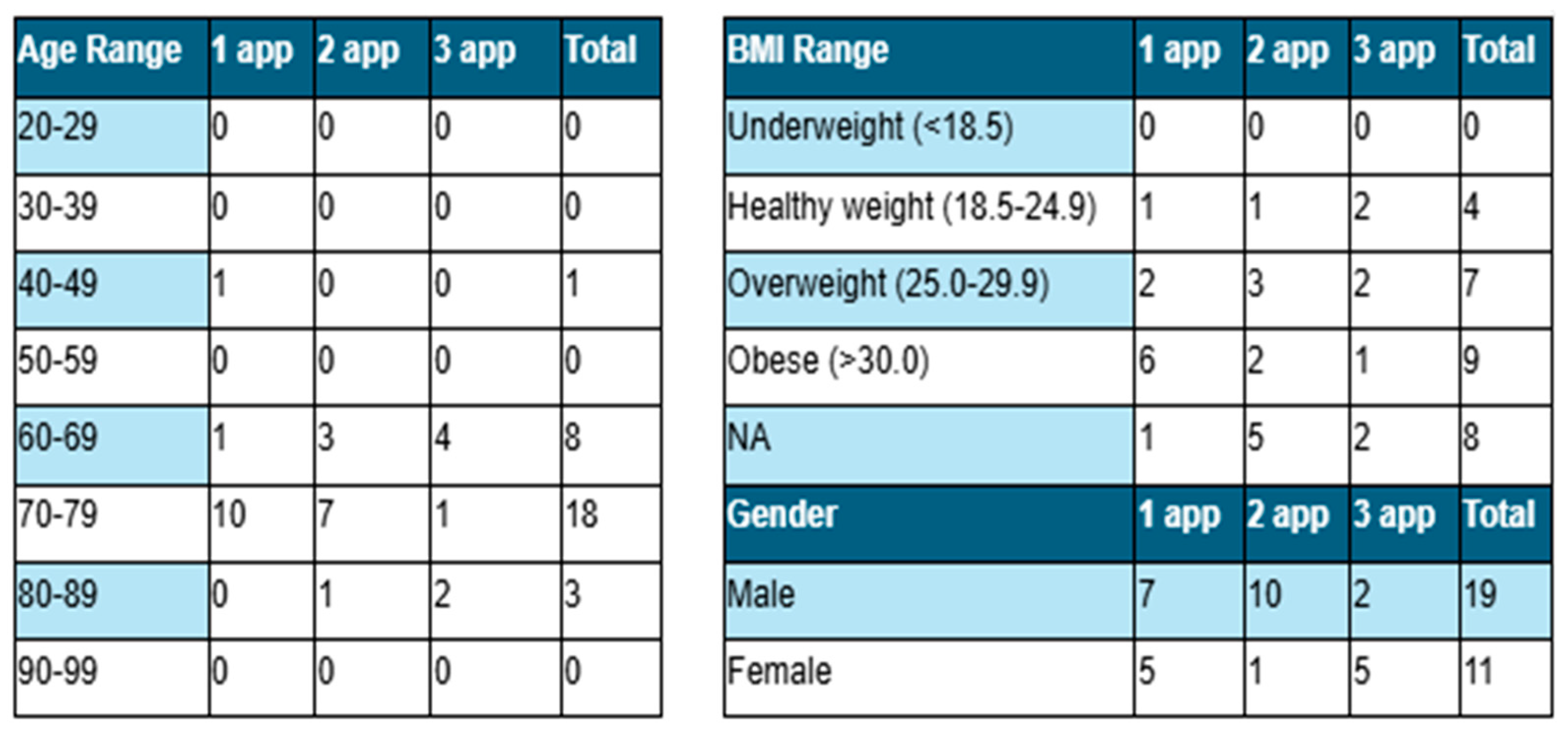

The participant group includes 30 patients, 63% female and 37% male. Twelve patients, five females and seven males, received one application. Based on the severity of the defect, eleven patients received two applications, and seven received three applications. Patient demographics are displayed in

Table 1.

2.3. Case Presentation

The patients in this cohort reported complaints of ankle pain at their initial consultation. For at least three months, they underwent conservative care, which included insoles, orthotics, shoe modifications, physical therapy, stretching exercises, home exercises, and anti-inflammatory medication. The patients in this study all failed a minimum of three months of conservative care and elected to use Wharton’s jelly allografts before considering surgical intervention.

2.4. Patient Care Procedures

Before the Wharton’s jelly allograft, patients received a radiograph or ultrasound to assess the level of tissue deterioration, and then an MRI to confirm the region and the severity of the damage. Next, patients were injected with two cc of local anesthesia using a 25-gauge needle under ultrasound guidance. Once the patients confirmed decreased pain after the anesthetic injection, they received the Wharton’s jelly allograft. The approach of entry varied depending on the location of the tissue damage. If the deteriorating region was more medial, then the approach for the application was more medial. If the area was more lateral, then the approach for the application was more lateral. All applications were guided by ultrasound or fluoroscopy, depending on the clinic. Patients waited at the office for 30 minutes after the application to ensure no reaction. No adverse response was reported. After the procedure, patients wore either a brace or a boot for two weeks, were prevented from using ice or anti-inflammatories for six weeks, and had a six-week check-up for reapplication. The number of reapplications depends on the severity of cartilage degeneration and the level of patient improvement after each application. Twelve patients were content with care after one application, ending follow-ups after 90 days; eleven patients received two applications, with follow-ups ending after 120 days; and seven patients received three applications, with follow-ups ending between 150 and 210 days, depending on the date of the third application. At every follow-up, patients filled out the QOLS, WOMAC, and NPRS scales to observe their progress.

3. Results

In the analysis of the results, it is crucial to highlight that a decrease in NPRS and WOMAC scale scores signifies clinical improvement. In contrast, an increase in the QOLS score corresponds to improvement. All patients reported a consistent reduction in the NPRS and WOMAC scores across all follow-up visits, regardless of the number of applications. In contrast, the QOLS had a marginal decrease from the 30-day to the 90-day visit in the one and two-application groups. The QOLS scores for patients with three total applications were the only group to exhibit improvement from the initial application to the final visit. The mean scores for each category are presented in

Table 2. WOMAC scores in the multi-application groups fluctuated from visit to visit. Still, they displayed a total decline in scores from the initial to the final evaluation greater than that of the single application group. The fluctuations among follow-ups are consistent with the slight increases in pain patients experienced that necessitated reapplication. A visual analysis of the average scores for each scale is displayed in

Figure 2, which indicates that patients who received more than one application experienced a more substantial reduction in scores over time.

4. Discussion

The observations of this study highlighted the promising results of applying 150 mg WJ tissue allograft to supplement tissue defects associated with ankle osteoarthritis in patients who have failed current conservative options. Each application group reported improvements in NPRS and WOMAC scores, showing substantial improvement in pain relief, stiffness, and functionality, contributing to overall patient well-being, with the rate of improvement increasing with each application (Table 3). Patients who received a single application reported a 1.3-point reduction in NPRS and a 12.9-point reduction in total WOMAC from the initial date to the 90-day visit, a 21.74% and 26.92% improvement, respectively. Among patients with two applications, NPRS decreased by 2.6 points and WOMAC (total) by 18.8 points between the initial application and the 150-day visit, a 46.15% and 41.78% improvement, respectively. At the 210-day follow-up, patients with three applications demonstrated the most significant reductions in NPRS and WOMAC scores, reporting a 6.2-point reduction and a 49.4-point reduction, an 80.43% and 79.18% improvement, respectively. The findings suggest an association between increased dosage of WJ tissue allografts and the likelihood of greater function and pain relief. The group with three applications was also the only group to report a positive improvement for the QOLS, a 19.45% improvement.

Although there is improvement in patient-reported scores, several limitations should be addressed. In this observational study, there is no direct comparison with a control group, and the scales used are not ultra-specific to the use site. While the WOMAC scale is commonly used in the evaluation of hip and knee osteoarthritis, studies have shown its use in assessing ankle function (Leung 2022, Basaran 2010, Ponkilainen 2019). A region-specific scale, such as the American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS) Ankle-Hindfoot Scale, could provide a more specific assessment for the target site, strengthening the relevancy of functional outcome measurements (Paget/Sierevelt 2023). An additional factor to be addressed when determining best practices for regenerative approaches using WJ is the type of local anesthetic. While lidocaine is widely used, research shows it has a level of cytotoxicity that may be harmful to the tissue allograft. Ropivacaine has been shown to have less of an impact on perinatal tissue allografts (Wu 2018, Rahnama 2013). This study protocol allowed clinics to use their preferred method of anesthesia. Still, additional studies comparing patient outcomes using different local anesthetics might confirm the benefits of unmethylated anesthesia over traditional forms. Future prospective and randomized control trials with larger patient pools would be beneficial for determining specific dosage protocols and validating efficacy.

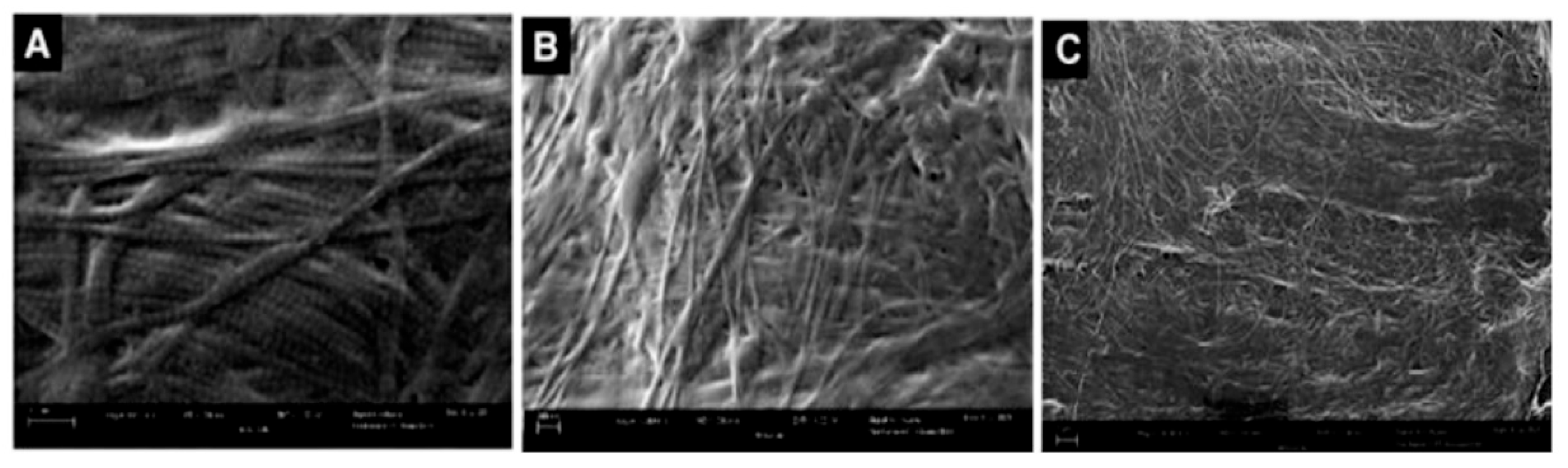

The positive outcomes of this study align with current literature that suggests WJ allografts are optimally matched for applications to cartilaginous defects. With further analysis of the framework of WJ, we can confirm that the homologous nature of the tissues aligns with the results reported by the patients. As a loose connective tissue found in the umbilical cord, WJ cushions the umbilical vessels and offers protection from tensile stress (Gupta 2020). The structural profile of WJ consists of high concentrations of collagen types I, II, III, and V, with additional beneficial elements including hyaluronic acid, cytokines, and growth factors, highlighting its functional compatibility in musculoskeletal tissue supplementation (Gupta 2020, Main 2021). Previous literature confirms the homologous structures between WJ and cartilage around the body (Lai 2024, Davis 2022).

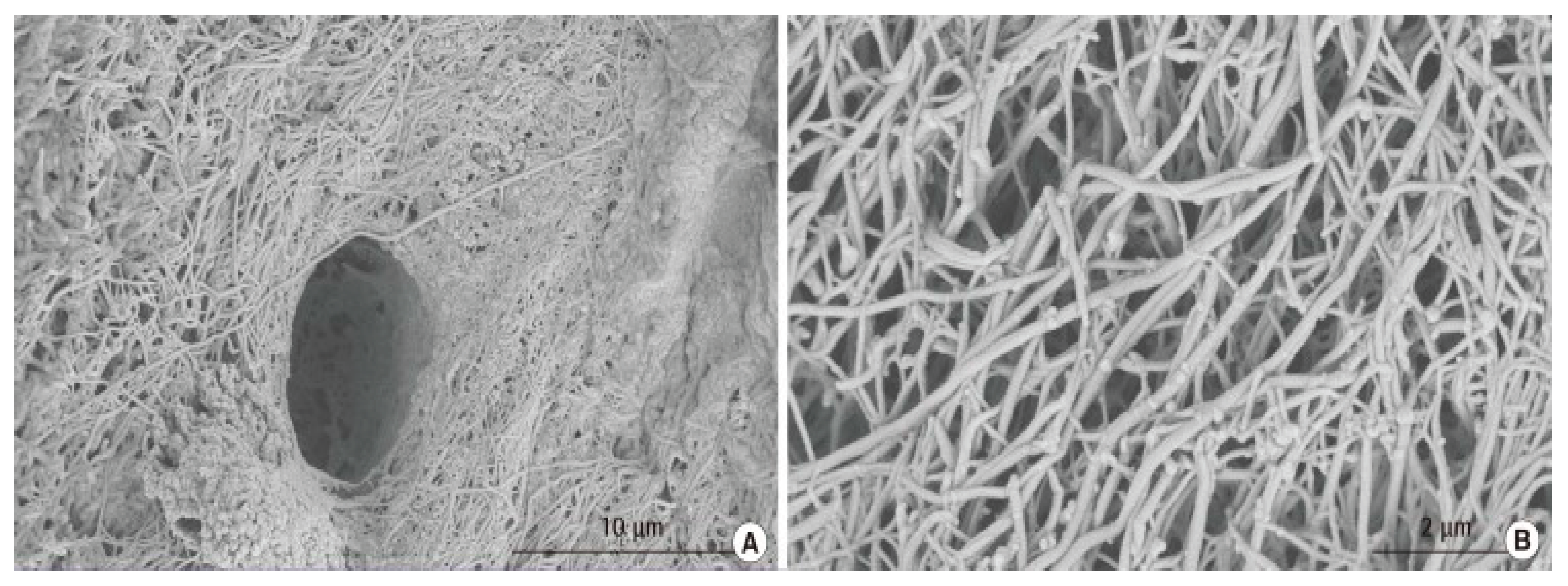

Figure 3 displays scanning electron microscopy (SEM) imaging of collagen structures in WJ tissue allografts like the ones used in this study. The composition of articular hyaline cartilage in the ankle joint is predominantly a collagen type II crosslinking extracellular matrix (ECM) (

Figure 4), a component found in Wharton’s jelly (Main 2021, Luo 2021). Cartilage degeneration, whether age-related or accelerated by osteoarthritis, leads to the disruption of the collagen matrix, and WJ tissue allografts may facilitate repair by interweaving with the damaged ECM.

The outcomes presented in this observational research serve as a reference point for subsequent studies on the use of Wharton’s jelly allografts in ankle osteoarthritis cases unresponsive to current standard-of-care protocols. Standard surgical procedures for ankle OA, such as ankle arthroscopy, ankle replacement, or ankle fusion, are associated with a range of potential surgical complications and have not been confirmed as the best practice. While autologous regenerative therapy, such as platelet-rich plasma (PRP), is widely popular as a noninvasive intervention, the physicians in this study observed that its application was associated with inconsistent clinical results. These results may stem from PRP’s reliance on patient health, with recent studies showing no statistical significance between PRP-applied patients and placebo (Paget/Reurink 2023). Adverse events and post-treatment complications have also been reported in association with PRP use (Arita 2024, Owczarczyk-Saczonek 2019). WJ has demonstrated consistent beneficial results in multiple studies involving the integration of regenerative medicine to treatment-resistant use sites (Lai 2024, Lai 2023, Davis/Sheinkop 2022). The tissue allograft is also sourced from rigorously screened donors and highly regulated minimal manipulation processing protocols to preserve the integrity of the matrix. Ensuring consistent quality of healthy connective tissue in each allograft.

Considering the functional composition of WJ and the favorable outcomes in this observational study, the application of WJ tissue allografts presents a promising alternative to the current conventional care practices and may contribute to supporting earlier intervention strategies aimed at preserving joint integrity. Continued research will be essential to further validate the clinical potential of WJ in its application to intra-articular cartilage degeneration in the ankle.

5. Conclusions

The cohort of 30 patients in this research observed that the application of Wharton’s jelly tissue allografts promoted decreases in pain, stiffness, and functionality in the ankle joint. No adverse events were reported in the observed patient group. Given the growing concerns in literature regarding the current standard-of-care treatment for intra-articular cartilage degeneration in the ankle, the pursuit of alternative methods is increasingly supported. Future studies are encouraged to establish further evidence supporting the benefits of Wharton’s jelly allografts in ankle osteoarthritis refractory to conventional care.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.B., G.K., L.M., A.L. (Albert Lai), H.J., L.P., J.S., and T.B.; methodology, B.B., G.K., L.M., A.L. (Albert Lai), H.J., and L.P.; software, T.B.; validation, N.L., A.L., E.C., and T.B.; formal analysis, N.L., A.L., and E.C.; investigation, B.B., G.K., L.M., A.L. (Albert Lai), H.J., L.P., J.S., N.L., A.L., and E.C.; resources, H.J., N.L., and A.L.; data curation, B.B., G.K., L.M., A.L. (Albert Lai), H.J., L.P., J.S., N.L., A.L., and E.C.; writing—original draft preparation, N.L., A.L., and E.C.; writing—review and editing, B.B., G.K., L.M., A.L. (Albert Lai), H.J., L.P., J.S., N.L., A.L., E.C., and T.B visualization, B.B., G.K., L.M., A.L. (Albert Lai), H.J., L.P., and T.B.; supervision, J.S. (John Shou) and T.B.; project administration, T.B.; funding acquisition, A B.B., G.K., L.M., A.L. (Albert Lai), H.J., L.P., J.S., and T.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This data was collected in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Institute of Regenerative and Cellular Medicine (protocol code IRCM-2022-311; Approval date: 9 June 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the staff at each clinic that submitted data to the repository for their assistance in data collection and submission.

Conflicts of Interest

John Shou is the principal investigator of the retrospective repository at Regenative Labs. Naomi Lambert, Alexis Lee, Eva Castle, and Tyler Barrett are associated with Regenative Labs. Regenerative Labs was involved in the design of the study, data analysis, and writing. Regenative Labs influenced the decision to publish.

References

- Herrera-Pérez M, Valderrabano V, Godoy-Santos AL, de César Netto C, González-Martín D, Tejero S. Ankle osteoarthritis: comprehensive review and treatment algorithm proposal. EFORT Open Rev. 2022;7(7):448-459. [CrossRef]

- He Y, Li Z, Alexander PG, et al. Pathogenesis of Osteoarthritis: Risk Factors, Regulatory Pathways in Chondrocytes, and Experimental Models. Biology (Basel). 2020;9(8):194. [CrossRef]

- Kurokawa H, Taniguchi A, Ueno Y, Miyamoto T, Tanaka Y. Risk Factors for the Progression of Varus Ankle Osteoarthritis. Foot Ankle Orthop. 2023;8(2):24730114231178763. [CrossRef]

- Al-Mahrouqi MM, Vicenzino B, MacDonald DA, Smith MD. Disability, Physical Impairments, and Poor Quality of Life, Rather Than Radiographic Changes, Are Related to Symptoms in Individuals With Ankle Osteoarthritis: A Cross-sectional Laboratory Study. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2020;50(12):711-722. [CrossRef]

- Tejero S, Prada-Chamorro E, González-Martín D, García-Guirao A, Galhoum A, Valderrabano V, Herrera-Pérez M. Conservative Treatment of Ankle Osteoarthritis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2021; 10(19):4561. [CrossRef]

- Vanderkarr M, J. Ruppenkamp, Vanderkarr M, Parikh A, Holy CE, Putnam MD. Incidence, costs and post-operative complications following ankle fracture—A US claims database analysis. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2022;23(1). [CrossRef]

- Phillips G, Stal D, Chernet R, Saquib Z. The Costs of Operative Fixation for Ankle Fractures. Foot & Ankle Orthopaedics. 2017;2(3). [CrossRef]

- Glasser J, DelliCarpini G, Walsh D, Chapter-Zylinski M, Patel S. The health economics of orthopedic foot and ankle surgery. Foot Ankle Surg. 2025;31(3):183-189. [CrossRef]

- Gupta A, El-Amin SF 3rd, Levy HJ, Sze-Tu R, Ibim SE, Maffulli N. Umbilical cord-derived Wharton’s jelly for regenerative medicine applications. J Orthop Surg Res. 2020;15(1):49. Published 2020 Feb 13. [CrossRef]

- Main BJ, Maffulli N, Valk JA, et al. Umbilical Cord-Derived Wharton’s Jelly for Regenerative Medicine Applications: A Systematic Review. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2021;14(11):1090. Published 2021 Oct 27. [CrossRef]

- Ouyang Z, Dong L, Yao F, et al. Cartilage-Related Collagens in Osteoarthritis and Rheumatoid Arthritis: From Pathogenesis to Therapeutics. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(12):9841. [CrossRef]

- Lin L, Xu Y, Li Y, et al. Nanofibrous Wharton’s jelly scaffold in combination with adipose-derived stem cells for cartilage engineering. Materials & Design. 2020;186:108216. [CrossRef]

- Gupta A, Aratikatla A. Allogenic Umbilical Cord Tissue as a Scaffold for Ankle Osteoarthritis. Cureus. 2023;15(10):e46572. [CrossRef]

- Davis JM, Sheinkop MB, Barrett TC. Evaluation of the Efficacy of Cryopreserved Human Umbilical Cord Tissue Allografts to Augment Functional and Pain Outcome Measures in Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis: An Observational Data Collection Study. Physiologia. 2022; 2(3):109-120. [CrossRef]

- Leung YY, Thumboo J, Yeo SJ, Wylde V, Tannant A. Validation and interval scale transformation of the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) in patients undergoing knee arthroplasty, using the Rasch model. Osteoarthr Cartil Open. 2022;4(4):100322. Published 2022 Nov 17. [CrossRef]

- Basaran S, Guzel R, Seydaoglu G, Guler-Uysal F. Validity, reliability, and comparison of the WOMAC osteoarthritis index and Lequesne algofunctional index in Turkish patients with hip or knee osteoarthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2010;29(7):749-756. [CrossRef]

- Ponkilainen VT, Häkkinen AH, Uimonen MM, Tukiainen E, Sandelin H, Repo JP. Validation of the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index in Patients Having Undergone Ankle Fracture Surgery. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2019;58(6):1100-1107. [CrossRef]

- Paget LDA, Sierevelt IN, Tol JL, Kerkhoffs GMMJ, Reurink G. The completely patient-reported version of the American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS) score: A valid and reliable measurement for ankle osteoarthritis. J ISAKOS. 2023;8(5):345-351. [CrossRef]

- Wu T, Smith J, Nie H, et al. Cytotoxicity of Local Anesthetics in Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2018;97(1):50-55. [CrossRef]

- Rahnama R, Wang M, Dang AC, Kim HT, Kuo AC. Cytotoxicity of local anesthetics on human mesenchymal stem cells. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(2):132-137. [CrossRef]

- Lai A, Tamea C, Shou J, Okafor A, Sparks J, Dodd R, Lambert N, Woods C, Schulte O, Kovar S, et al. Retrospective Evaluation of Cryopreserved Human Umbilical Cord Tissue Allografts in the Supplementation of Cartilage Defects Associated with Hip Osteoarthritis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(14):4040. [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.M.; Purita, J.R.; Shou, J.; Barrett, T.C. Three-Dimensional Electron Microscopy of Human Umbilical Cord Tissue Allograft Pre and Post Processing: A Literature Comparison. J. Biomed. Res. Environ. Sci. 2022, 3, 934–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo S, Cao Y, Hu P, Wang N, Wan Y. Quantitative evaluation of ankle cartilage in asymptomatic adolescent football players after season by T2-mapping magnetic resonance imaging. Biomed Eng Online. 2021;20(1):130. Published 2021 Dec 28. [CrossRef]

- Lim EH, Sardinha JP, Myers S. Nanotechnology biomimetic cartilage regenerative scaffolds. Arch Plast Surg. 2014;41(3):231-240. [CrossRef]

- Paget LDA, Reurink G, de Vos RJ, et al. Platelet-Rich Plasma Injections for the Treatment of Ankle Osteoarthritis. Am J Sports Med. 2023;51(10):2625-2634. [CrossRef]

- Arita A, Tobita M. Adverse events related to platelet-rich plasma therapy and future issues to be resolved. Regen Ther. 2024;26:496-501. Published 2024 Jul 20. [CrossRef]

- Owczarczyk-Saczonek A, Wygonowska E, Budkiewicz M, Placek W. Serum sickness disease in a patient with alopecia areata and Meniere’ disease after PRP procedure. Dermatol Ther. 2019;32(2):e12798. [CrossRef]

- Lai A, Shou J, Traina SA, Barrett T. The Durability and Efficacy of Cryopreserved Human Umbilical Cord Tissue Allograft for the Supplementation of Cartilage Defects Associated with the Sacroiliac Joint: A Case Series. Reports. 2023; 6(1):12. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).