1. Introduction

Plantar fasciitis is the most common cause of heel pain in adults, accounting for approximately 1 million annual clinical visits in the United States (Trojian, 2019). While commonly known as plantar fasciitis, a shift away from the nomenclature has been made over the past 20 years, as research indicates it is not an inflammatory condition. Plantar fasciosis (PF), or plantar fasciopathy, more accurately describes what imaging studies show to be degeneration of the plantar fascia (Landorf, 2015). PF affects approximately 10% of the general population, irrespective of age or physical activity levels (Trojian, 2019, Latt, 2020). Several medical issues, encompassing neurological, arthritic, traumatic, neoplastic, infectious, or vascular factors, may result in the occurrence of plantar enthesopathy (Latt, 2020). Risk factors, patient history, and physical examination are used to guide the diagnosis of PF. Common risk factors include elderly age, high BMI, and patients of the female gender (Goff, 2011). A study by Liu (2024) showed that a decline in calcaneal elasticity present under mechanical stress leads to microfractures and inflammation in the fascia and surrounding muscle groups, contributing to heel pain (Liu, 2024). Continuous strain or repetitive impacts can cause both micro and larger tears in the plantar fascia. These tears are the primary cause of patient pain. If the strain on the fascia persists, it can prevent the body from facilitating effective repair.

Due to the indeterminate pathogenesis of plantar fasciopathy, several conservative and nonconservative standard-of-care interventions are available. Conservative options include lifestyle modifications, plantar fascia-specific stretching, orthotics, NSAIDs, and focal extracorporeal shockwave therapy (Lim, 2016). According to a study by Nahin (2019), around 50% of individuals with PF use over-the-counter NSAIDs (Nahin, 2019). Between 2010 and 2018, the number of plantar fasciopathy (PF) cases more than doubled, and this trend is expected to persist, thereby escalating the annual economic burden. Each year, nearly $600 is spent on NSAIDs per individual. When factoring in the costs of standard treatments, the total annual expenditure for PF amounts to $284 million (Ahn, 2023). Conservative treatment options may provide temporary symptomatic relief, but the underlying tissue damage remains unaddressed. While nonconservative options are available, surgery is often a last resort in plantar fasciopathy, typically for patients who do not respond to conservative interventions for at least 6 to 12 months (Buchanan, 2024). Multiple complications may arise following surgical interventions, with pain recurrence being the most prevalent (Ward, 2022). Other complications include nerve injury, plantar fascia rupture, and flattening of the longitudinal arch (Buchanan, 2024). With the risk of unfavorable outcomes post-surgery and a potential rise in pain levels, it is evident that there is an urgent need for alternative care. The rise of autologous platelet-rich plasma therapy as a regenerative intervention has been considered a popular replacement for the current standard-of-care methods. Caution is necessary when interpreting the results of studies on PRP injections, as numerous investigations have shown no notable differences between the group receiving PRP and the placebo. A study by Johnson-Lynn (2018) observed no significant benefit for the use of PRP over normal saline in the management of PF (Johnson-Lynn, 2018). As reported by Valotto-Junior (2023), there were no meaningful differences in the quality of life, and the presence of platelets did not influence pain alleviation (Valotto-Junior, 2023). Establishing reliable and beneficial methods for the management of PF that target the structural degradation of the fascia is essential for the continued development of conservative care options in patients suffering from treatment-resistant PF.

Wharton’s jelly (WJ) tissue allografts can be transplanted to supplement the damaged fascia and minimize the adverse effects of plantar fasciopathy. The allografts come from donated human umbilical cords, collected and processed under FDA guidance. The structural components of WJ, consisting mainly of collagen types I, III, and V and fibrous structures, are comparable to the extracellular matrices (ECM) of human articular cartilage, tendons, and dermal tissues (Sobolewski, 1997). WJ has been successfully applied to over 180 homologous use sites, indicating its safety and efficacy (Lai, 2024, Davis, 2022). Considering the limited conservative options for the management of plantar fasciopathy, this observational research study investigates the application of Wharton’s jelly as an alternative approach to the conventional standard-of-care interventions for defects of the plantar fascia.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design

The observational repository at Regenative Labs was used to identify nine patients with plantar fascia deterioration. The data repository is collected following the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki with approval from the Institutional Review Board of the Institute of Regenerative and Cellular Medicine (IRCM-2021-311).

Case Presentation

The majority of patients presented with Poststatic Dyskinesia at their initial consultation. The plantar fascia was then checked with ultrasound for structural defects, including thickening hypoxic areas, osteophytes, tissue damage, and micro-tearing. Patients were prescribed conservative care for at least three months, including physical therapy, shoe modifications, anti-inflammatories, home exercises, and orthotics. The patients in this group all failed at least three months of conservative care and opted for Warton’s jelly allografts before considering more invasive interventions. Patient demographics are displayed in

Table 1.

Patient Care Procedures

On the day of the procedure, tissue degeneration was identified via ultrasound, and two cc of 1% lidocaine was injected into the specific points of deterioration to confirm that the site of pain was caused by the micro tears in the patient’s fascia. If the patient confirmed a decrease in pain after the lidocaine injection, the area of tearing was then filled in with 2cc of 150mg/mL Wharton’s jelly allograft via a 25-gauge needle under ultrasound guidance. Micro-tearing and fascial degeneration most often occurred at the insertion site or slightly distal to it. A medial approach was used to place the WJ allograft into the fascia at the insertion site and distally along visible degeneration. Following the procedure, the patient was instructed to wait at the office for thirty minutes to be monitored for any signs of a reaction. No patients reported adverse reactions throughout the observational period. Aftercare procedure instructions included massaging the area with the thumb to reduce and break up scar tissue, massaging the medial tubercle and heel area twice a day, restricting the use of anti-inflammatories and ice for six weeks, and stretching the Achilles and calf muscles twice daily. Patients filled out QOLS, NPRS, and WOMAC scales on the day of the application, and again 30 and 90 days after.

3. Results

3.1. Results

When interpreting the results of the observational study, the decrease in WOMAC and NPRS scores equates to improvement, and the increase in QOLS scores equates to improvement. All patients reported a consistent reduction in scores in all WOMAC scales and the NPRS from the initial application to the final 90-day visit. In addition, the QOLS scores observed an increase from the initial application to the final evaluation.

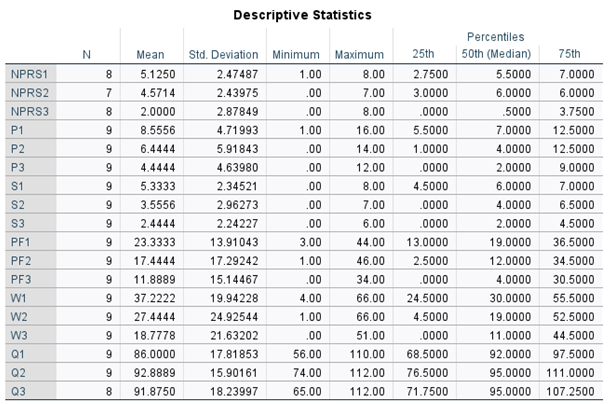

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics of each scale over a 90-day interval.

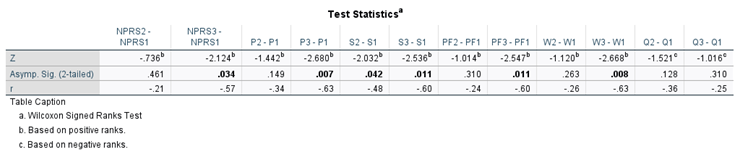

Table 3 displays the percent improvement at each visit. A Wilcoxon signed rank test was performed to determine any significant change between the initial and 30-day score and the initial and 90-day scores (

Table 4).

Figure 1 is the visual representation of the mean scores over time in each scale.

4. Discussion

The results reported in this study demonstrate the promising benefits of applying 150 mg WJ tissue allograft to supplement tissue defects associated with treatment-resistant plantar fasciopathy. Individuals in the cohort reported favorable outcomes on all three scales utilized, indicating marked progress in pain relief, decreased stiffness, and increased functionality, which collectively led to an elevated quality of life (

Figure 1,

Table 2&3). Patients reported a 3.1-point reduction in overall NPRS scores and an 18.4-point reduction in total WOMAC scores observed from the initial application to the final follow-up date, a 60.98% and 49.55% improvement, respectively. A 5.8-point improvement in the QOLS scale was also recorded between the initial visit and the 90-day follow-up, a 6.83% improvement. The positive trend of improvements in scores was confirmed with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test (WSRT). The test revealed a significant difference between initial and final scores for the NPRS, WOMAC total, and each WOMAC sub-scale (

Table 4). There was also a significant improvement in stiffness scores from the initial to the 30-day visit. The NPRS initial score (Md = 5.5, n = 8) and final score (Md = .5, n = 8), ), z = -2.124, p = .034, with a strong effect size, r = .-0.57. The WOMAC total initial score (Md = 30, n = 9) and final score (Md = 11, n = 9), ), z = -2.668, p = .008, with a strong effect size, r = .-0.63. The pain initial score (Md = 7, n = 9) and final score (Md = 2, n = 9), ), z = -2.68, p = .007, with a strong effect size, r = .-0.63. The stiffness initial score (Md = 6, n = 9) and final score (Md = 2, n = 9), ), z = -2.53, p = .011, with a strong effect size, r = .-0.60. Finally, the physical function initial score (Md = 19, n = 9) and final score (Md = 4, n = 9), ), z = -2.55, p = .011, with a strong effect size, r = .-0.60. The findings demonstrated in this study suggest the benefits of the application of WJ for treatment-resistant PF patients. A large-scale randomized controlled trial in future research should confirm the statistical significance observed. One limitation was the use of the WOMAC scale, which is traditionally applied to hip and knee osteoarthritis, but is not routinely used in the assessment of PF. Assessment tools frequently used in observing PF cases include the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) or NPRS for pain intensity, the Foot Function Index (FFI) for measuring pain, disability, and activity, and the American Orthopedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS) score for examining the general functional status of the foot and ankle (Malik, 2024, Yingjie, 2024). Larger patient pools using a specific assessment scale with a control group would mitigate these limitations and strengthen the evidence for the efficacy of WJ in this specific application.

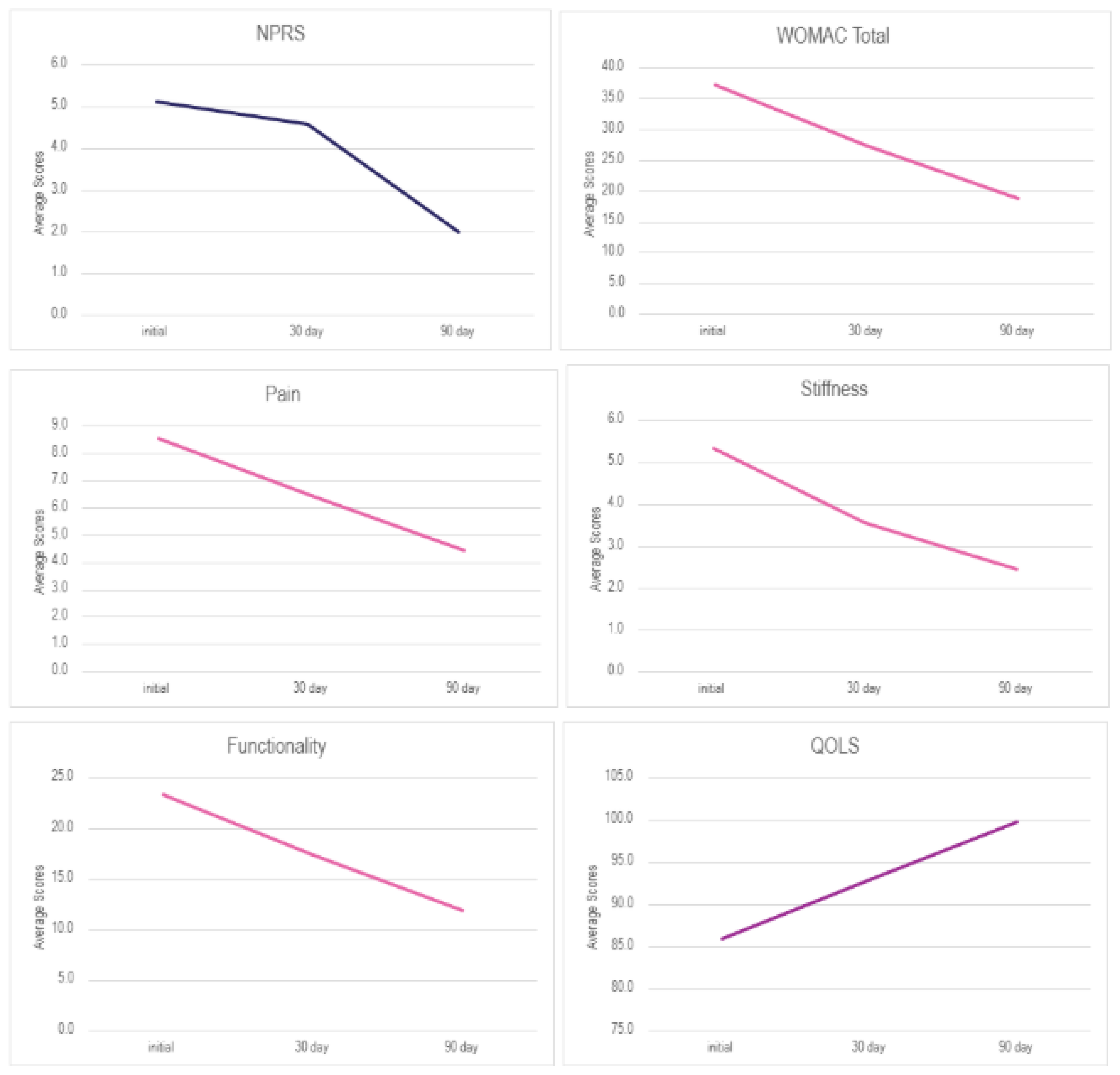

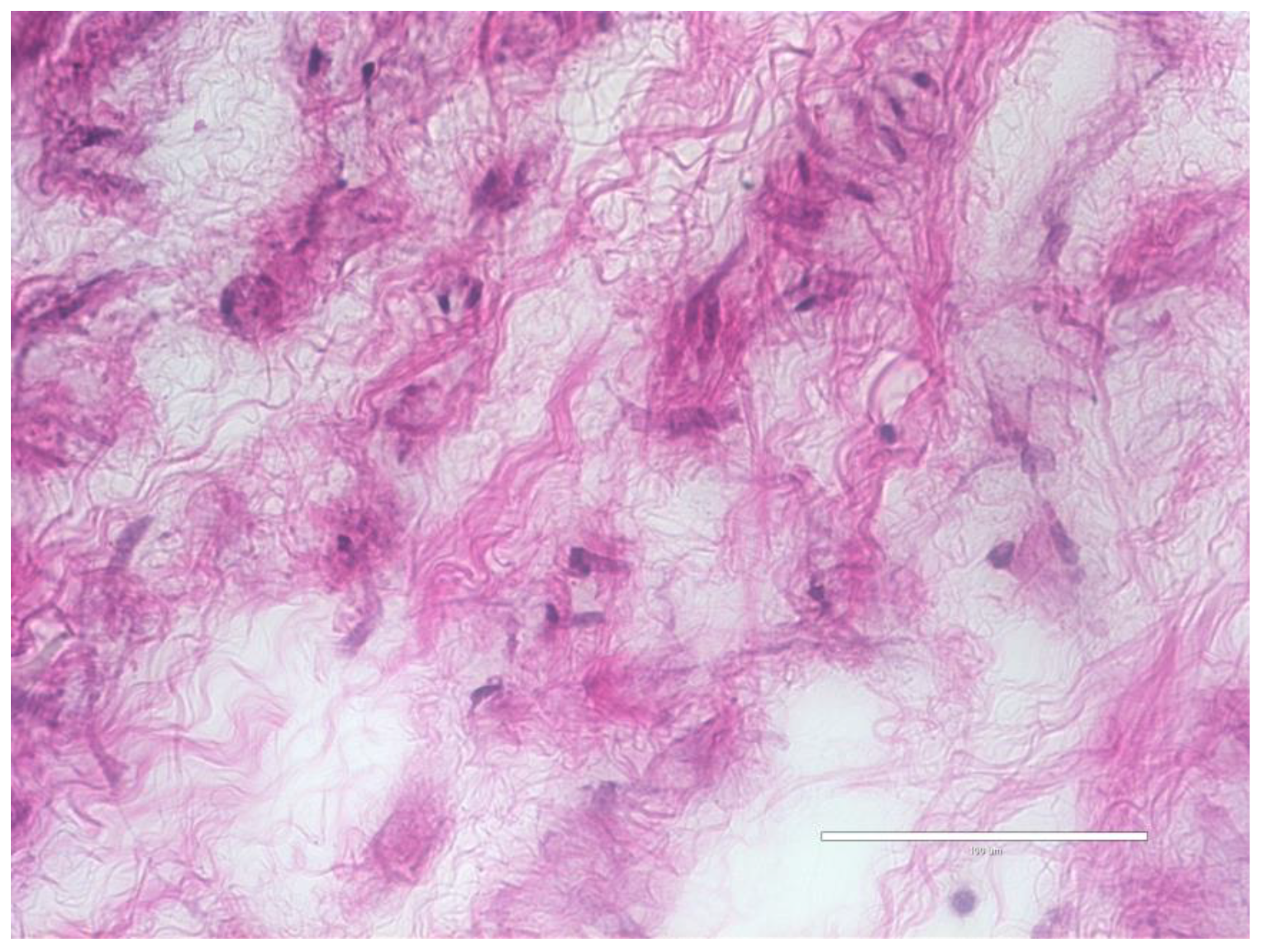

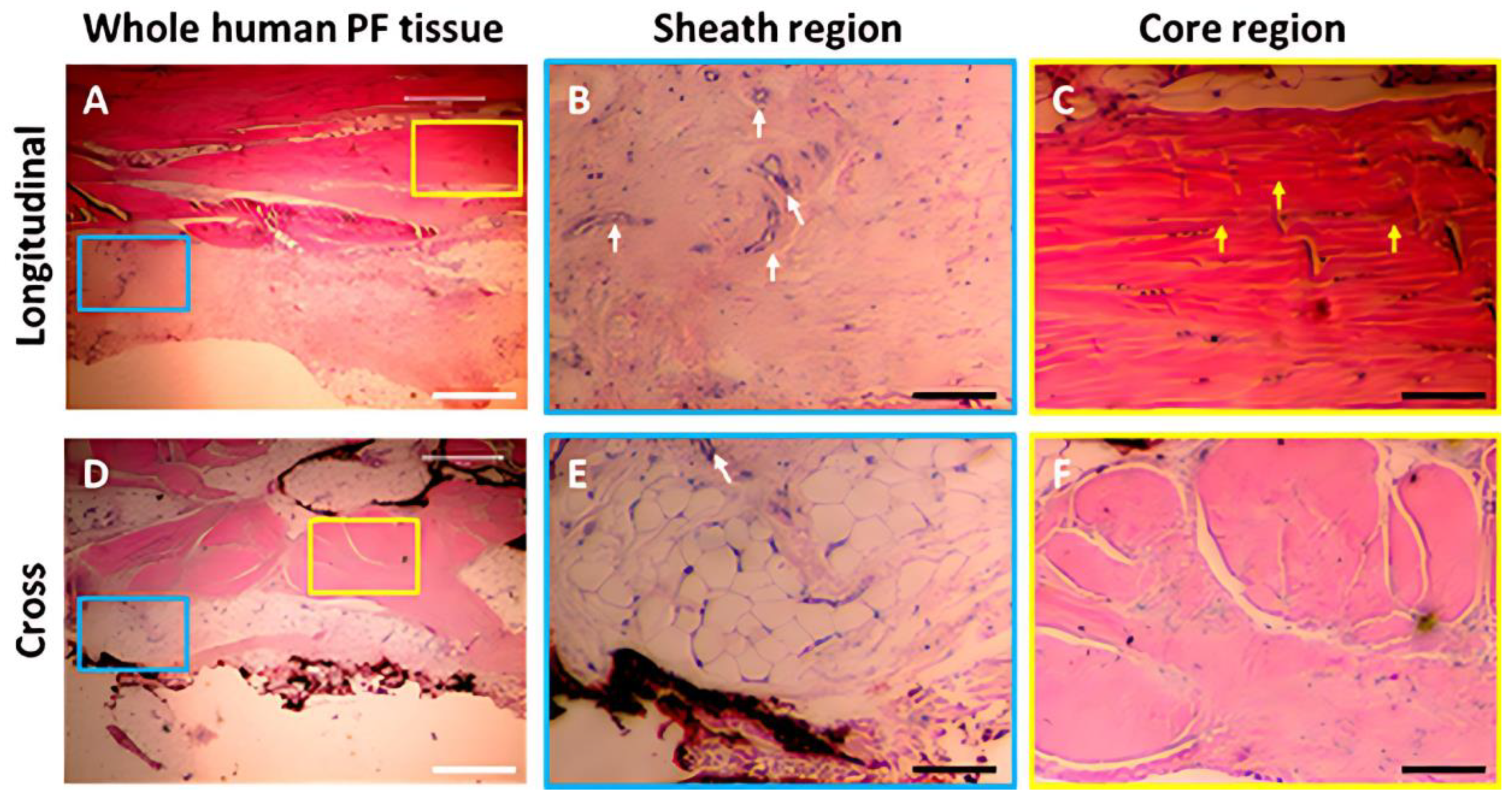

Favorable outcomes reported in this study align with the current literature on the application of WJ to the collagenous site of defects. The confirmation of the homologous nature of WJ in this study is observed in the similarities between the framework of WJ and the plantar fascia. The structural profile of WJ is predominantly comprised of collagen types I, III, and V, with additional beneficial compounds such as cytokines and hyaluronic acid, demonstrating the functional compatibility in musculoskeletal tissue supplementation (Gupta, 2020). Tissue allografts used in this study have been imaged with scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) staining to confirm the integrity of collagen structures present post-processing (

Figure 2&4). Cross-linking collagen fibers preserved through minimal manipulation practices, identified in

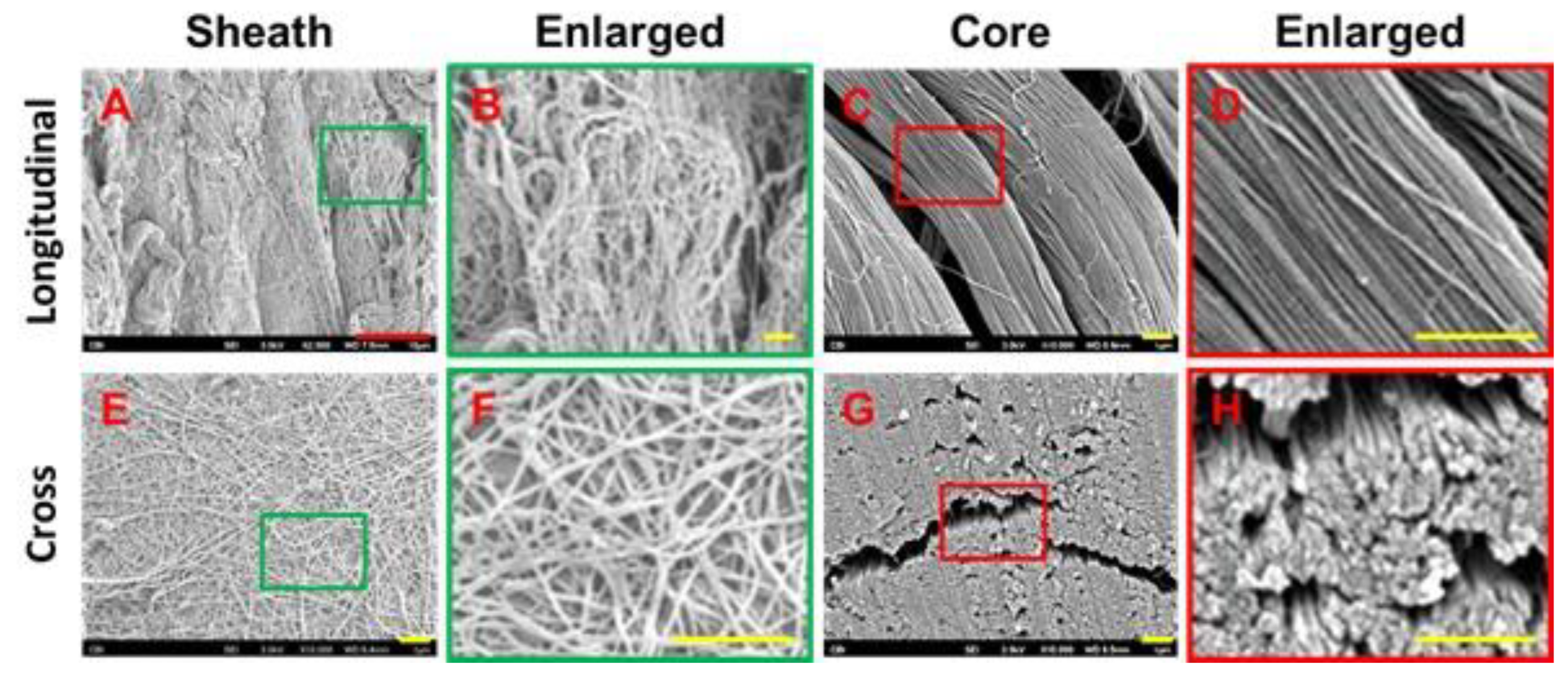

Figure 2, makes WJ tissue allografts clinically applicable to collagen-based structural tissues in the plantar fascia. The structural profile of plantar fascia contains two different kinds of tissues: a loose connective tissue sheath surrounding a tightly bundled collagen core (Zhang, 2020). The plantar fascia core predominantly contains type I cross-linking, longitudinal collagen fibers, as shown in

Figure 3 (Alabau-Dasi, 2022, Zhang, 2020). H & E staining of WJ tissue allografts colors the extracellular matrix with varying degrees of pink, illustrated in

Figure 4. In comparison, the plantar fascia sheath contains a loose connective tissue region comparable to the loose connective tissue component observed in WJ (

Figure 5). The collagenic ECM component in both WJ and plantar fascia functions to supply tensile strength and structural support in their corresponding anatomical regions. Collagen breakdown of the plantar fascia, whether from excessive stress or natural causes, causes the disorganization of collagen fibers in the fascia, which decreases the strength and elasticity of the structural fibers (Latt, 2020). The use of WJ tissue allografts in the plantar fascia directly replaces the damaged collagen matrix, mirroring existing scaffolding to support the organization of the fibers.

This observational research suggests that Wharton’s jelly is a prospective alternative approach to current care methods. Standard-of-care procedures for plantar fasciopathy have been associated with various risks, complications, and inconsistent data results. PRP is one of the most popular alternative care protocols; however, the physicians involved in this study noticed inconsistent results using PRP on their other patients compared to the results reported by the WJ recipients. The varying outcomes associated with PRP could be attributed to dependence on the platelet counts and individual health conditions of the patients. A 2023 study by Rossi reported significant differences in PRP therapy influenced by the patient’s platelet count (Rossi, 2023). Inconsistent protocols associated with PRP have contributed to the discrediting of many cases, mainly due to the neglect of evaluating patients' platelet levels before therapy is administered (Rahman, 2024). WJ demonstrates effective and consistent results in this study, corroborating findings reported in other homologous use sites (Lai, 2024, Davis, 2022). A study by Lai (2024) demonstrated that patients suffering from rotator cuff tears significantly improved in pain and range of motion with the application of WJ (Lai, 2024). Another recent study highlights that the application of WJ may mitigate significant defects in the articular cartilage scaffold (Davis, 2022). The outcomes of this observational research study provide preliminary results on the prospective benefit of WJ tissue allograft applications in patients with plantar fascia defects who are unresponsive to current care methods. Further research will contribute to the growing pool of literature and strengthen support for the efficacy of WJ allografts in plantar fasciopathy.

5. Conclusions

All patients in the study experienced a reduction in pain and stiffness, improving the functionality of the plantar fascia. No adverse events have been reported to date. This study lays a reference point for further investigation into regenerative methods for plantar fascia defects unresponsive to standard-of-care. The patient outcomes in this study indicate benefits from the application of Wharton’s jelly and advocate for the inclusion of regenerative medicine in standardized conservative clinical practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.B., G.K., C.T., J.S., and T.B.; methodology, B.B., G.K., C.T.; software, T.B.; validation, N.L., A.L., E.C., and T.B.; formal analysis, N.L., A.L., and E.C.; investigation, B.B., G.K., C.T., J.S., N.L., A.L., and E.C.; resources, N.L., and A.L..; data curation, B.B., G.K., C.T., J.S., N.L., A.L., and E.C.; writing—original draft preparation, N.L., A.L., and E.C.; writing—review and editing, B.B., G.K., C.T., J.S., N.L., A.L., E.C., and T.B visualization, B.B., G.K., C.T., and T.B.; supervision, J.S. (John Shou) and T.B.; project administration, T.B.; funding acquisition, B.B., G.K., C.T., J.S., and T.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This data was collected in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Institute of Regenerative and Cellular Medicine (protocol code IRCM-2022-311; Approval date: 9 June 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the staff at each clinic that submitted data to the repository for their assistance in data collection and submission.

Conflicts of Interest

John Shou is the principal investigator of the retrospective repository at Regenative Labs. Naomi Lambert, Alexis Lee, Eva Castle, and Tyler Barrett are associated with Regenative Labs. Regenerative Labs was involved in the design of the study, data analysis, and writing. Regenative Labs influenced the decision to publish.

References

- Trojian, T.; Tucker, A.K. Plantar Fasciitis. Am Fam Physician. 2019, 99, 744–750. [Google Scholar]

- Landorf, K.B. Plantar heel pain and plantar fasciitis. BMJ Clin Evid. 2015, 2015, 1111. [Google Scholar]

- Latt, L.D.; Jaffe, D.E.; Tang, Y.; Taljanovic, M.S. Evaluation and Treatment of Chronic Plantar Fasciitis. Foot Ankle Orthop. 2020, 5, 2473011419896763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.L.; Christensen, J.C.; Kravitz, S.R.; et al. The diagnosis and treatment of heel pain: a clinical practice guideline-revision 2010. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2010, 49, S1–S19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.; Chen, Q.; Yang, K.; Cai, F. Prevalence, characteristics, and associated risk factors of plantar heel pain in americans : The cross-sectional NHANES study. J Orthop Surg Res. 2024, 19, s13018–s13024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, A.T.; How, C.H.; Tan, B. Management of plantar fasciitis in the outpatient setting. Singapore Med J. 2016, 57, 168–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nahin, R.L. Prevalence and Pharmaceutical Treatment of Plantar Fasciitis in United States Adults. J Pain. 2018, 19, 885–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.; Yeo, J.; Lee, S.H.; et al. Healthcare usage and cost for plantar fasciitis: a retrospective observational analysis of the 2010-2018 health insurance review and assessment service national patient sample data. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023, 23, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

Buchanan, B.K.; Kushner, D. Plantar fasciitis. PubMed. Published 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK431073/.

- Ward, L.; Mercer, N.P.; Azam, M.T.; et al. Outcomes of Endoscopic Treatment for Plantar Fasciitis: A Systematic Review. Foot Ankle Spec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Johnson-Lynn, S.; Cooney, A.; Ferguson, D.; et al. A Feasibility Study Comparing Platelet-Rich Plasma Injection With Saline for the Treatment of Plantar Fasciitis Using a Prospective, Randomized Trial Design. Foot Ankle Spec. 2019, 12, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elcio Valotto-Junior Bin Silva, S.; Henrique, L.; et al. A randomized study comparing the effect of platelet-rich plasma and platelet-poor plasma for the treatment of plantar fasciitis. Research, Society and Development. 2023, 12, e7812943168–e7812943168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobolewski, K.; Bańkowski, E.; Chyczewski, L.; Jaworski, S. Collagen and glycosaminoglycans of Wharton's jelly. Biol Neonate. 1997, 71, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, A.; Tamea, C.; Shou, J.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Wharton's Jelly Connective Tissue Allograft for Rotator Cuff Tears: Findings from a Retrospective Observational Study. Biomedicines. 2024, 12, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, J.M.; Sheinkop, M.B.; Barrett, T.C. Evaluation of the Efficacy of Cryopreserved Human Umbilical Cord Tissue Allografts to Augment Functional and Pain Outcome Measures in Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis: An Observational Data Collection Study. Physiologia. 2022, 2, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ujala Malik Fatima, A.; Ahmad, E.; Taqi, S.Z.; Tahir, I.; Rehman, A. Prevalence of Plantar Fasciitis Pain and Its Association with Quality of Work Among Sales Promotion Persons at Supermarkets. Journal of Health and Rehabilitation Research. 2024, 4, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yingjie, Z.; Mithu, M.M.; Haque, M.A.; et al. Comparative effectiveness of endoscopic plantar fasciotomy, needle knife therapy, and conventional painkillers in the treatment of plantar fasciitis: a real-world evidence study. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research. 2024, 19, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. Research On Plantar Fasciitis. Stem Cells Research Development & Therapy. 2020, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabau-Dasi, R.; Nieto-Gil, P.; Ortega-Avila, A.B.; Gijon-Nogueron, G. Variations in the Thickness of the Plantar Fascia After Training Based in Training Race. A Pilot Study. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2022, 61, 1230–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.M.; Purita, J.R.; Shou, J.; Barrett, T.C. Three-Dimensional Electron Microscopy of Human Umbilical Cord Tissue Allograft Pre and Post Processing: A Literature Comparison. J. Biomed. Res. Environ. Sci. 2022, 3, 934–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, L.; Ranalletta, M.; Pasqualini, I.; et al. Substantial Variability in Platelet-Rich Plasma Composition Is Based on Patient Age and Baseline Platelet Count. Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil. 2023, 5, e853–e858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, E.; Rao, P.; Abu-Farsakh, H.N.; et al. Systematic Review of Platelet-Rich Plasma in Medical and Surgical Specialties: Quality, Evaluation, Evidence, and Enforcement. J Clin Med. 2024, 13, 4571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Average score over time from each scale.

Figure 1.

Average score over time from each scale.

Figure 2.

SEM micrographs of post-processed umbilical cord tissue samples. (A) SEM image of preserved cross-linked collagen structures. (Scale bar: 300nm). (B) SEM image of preserved random directional structural composition of collagen fibers. (Scale bar: 300nm). (C) SEM image of multidirectional linkage of collagen fibers (Scale bar: 1μm) (Davis, 2022).

Figure 2.

SEM micrographs of post-processed umbilical cord tissue samples. (A) SEM image of preserved cross-linked collagen structures. (Scale bar: 300nm). (B) SEM image of preserved random directional structural composition of collagen fibers. (Scale bar: 300nm). (C) SEM image of multidirectional linkage of collagen fibers (Scale bar: 1μm) (Davis, 2022).

Figure 3.

Characterization of human PF tissue tested by Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM). A-D: Longitudinal tissue sections; E-H: Cross sections. SEM images show that human PF tissue has a loose net-like mesh of sheath region outlined by a green box (A, B, E, F), and high-density collagen fiber bundles are found in the core region outlined by a red box (C, D, G, H). The enlarged images of the sheath and core tissues show that the diameter of collagen fibers in the sheath is thinner than that in the core tissues. Red bar: 10 mm; Yellow bars: 1 mm. (Zhang, 2020).

Figure 3.

Characterization of human PF tissue tested by Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM). A-D: Longitudinal tissue sections; E-H: Cross sections. SEM images show that human PF tissue has a loose net-like mesh of sheath region outlined by a green box (A, B, E, F), and high-density collagen fiber bundles are found in the core region outlined by a red box (C, D, G, H). The enlarged images of the sheath and core tissues show that the diameter of collagen fibers in the sheath is thinner than that in the core tissues. Red bar: 10 mm; Yellow bars: 1 mm. (Zhang, 2020).

Figure 4.

Human Wharton’s Jelly tissue tested by H & E staining. Frozen slices of WJ were prepared and stained, 40x magnification, scale bar 100µm.

Figure 4.

Human Wharton’s Jelly tissue tested by H & E staining. Frozen slices of WJ were prepared and stained, 40x magnification, scale bar 100µm.

Figure 5.

Characterization of human PF tissue tested by H & E staining. A-C: Longitudinal tissue sections; D-F: Cross sections. Histology results show that human PF tissue has a sheath region outlined by a blue box (A, D) and a core region outlined by a yellow box (A, D). An enlarged image of the sheath region shows a cross-linked collagen network (B, E), while an enlarged image of the core region displays well-organized collagen bundles (C, F). Sheath tissue has many blood vessels (white arrows in B, E). Core tissue has many elongated cells (yellow arrows in C). White bars: 100 mm; Black bars: 25 mm. (Zhang, 2020).

Figure 5.

Characterization of human PF tissue tested by H & E staining. A-C: Longitudinal tissue sections; D-F: Cross sections. Histology results show that human PF tissue has a sheath region outlined by a blue box (A, D) and a core region outlined by a yellow box (A, D). An enlarged image of the sheath region shows a cross-linked collagen network (B, E), while an enlarged image of the core region displays well-organized collagen bundles (C, F). Sheath tissue has many blood vessels (white arrows in B, E). Core tissue has many elongated cells (yellow arrows in C). White bars: 100 mm; Black bars: 25 mm. (Zhang, 2020).

Table 1.

Patient age, BMI, and gender.

Table 1.

Patient age, BMI, and gender.

| Age Range |

1 app |

BMI Range |

1 app |

| 30-39 |

0 |

Healthy weight (18.5-24.9) |

1 |

| 40-49 |

0 |

Overweight (25.0-29.9) |

2 |

| 50-59 |

0 |

Obese (>30.0) |

2 |

| 60-69 |

1 |

NA |

3 |

| 70-79 |

1 |

Gender |

1 app |

| 80-89 |

4 |

Male |

5 |

| 90-99 |

2 |

Female |

4 |

Table 2.

Sample size and descriptive statistics for six scales at each interval.

Table 2.

Sample size and descriptive statistics for six scales at each interval.

| Variable |

Key |

| NPRS |

Numerical Pain Rating Scale |

| P |

WOMAC - Pain |

| S |

WOMAC - Stiffness |

| PF |

WOMAC - Physical Function |

| W |

WOMAC - Total |

| Q |

Quality of life scale |

| 1 |

Initial Visit |

| 2 |

30-Day Visit |

Table 3.

Percent change for each scale from initial to follow-up visits.

Table 3.

Percent change for each scale from initial to follow-up visits.

| 1 App |

Initial |

Day 30 |

Day 90 |

| NPRS |

0% |

10.80% |

60.98% |

| WOMAC Total |

0% |

26.27% |

49.55% |

| Pain |

0% |

24.68% |

48.05% |

| Stiffness |

0% |

33.33% |

54.17% |

| Functionality |

0% |

25.24% |

49.05% |

| QOLS |

0% |

8.01% |

6.83% |

Table 4.

Results from the Wilcoxon signed rank test, significant p values are in bold.

Table 4.

Results from the Wilcoxon signed rank test, significant p values are in bold.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).