What is known: Cochrane database review rated conservative and surgical treatment of rotator cuff syndrome equally effective regarding pain, function and quality of life in short term studies. Post-surgical and conservative treatment often lasts 12 weeks. Longer term outcome studies beyond 2 years post treatment are lacking.

What is new: a randomized controlled study using a wall-based TFS in a single session yielded immediate reduction in pain and improvement in range of motion in 80 intervention patients vs. 87 controls. Mean 52-month (range 19 – 60) follow-up showed further improvement. This method is rapid, inexpensive and widely applicable.

Introduction:

Rotator cuff syndrome is one of the most common orthopedic injuries of the upper extremities, with biphasic incidence peaking at 35 and 55 years of age [

1,

2,

3] Cadaveric studies find nearly 50% of individuals over 80 years of age have significant rotator cuff tears [

1,

2]. MRI is the “gold standard” to identify people with RCS [

4,

5,

6,

7];

The classical symptoms include pain at 90 degrees of abduction and/or flexion, which increases with further abduction, then trails off above approximately 135 degrees, and frank inability to abduct any further than 80 degrees in more severe cases. Because of its broad range of motion, the shoulder joint or glenohumeral joint requires four muscles, the supraspinatus (above the spine of the scapula) infraspinatus (below the spine of the scapula), teres minor (small rotator) and subscapularis (beneath the scapula) to maintain its proper alignment; MRI detects a tear in the supraspinatus muscle in approximately 90% of RCS. Surgery and conservative therapy have been shown to be equally successful with partial tears, but the surgical results are better for full thickness tears as currently reported [

8,

9]. More than 10% of conservatively treated RCS patients progress to surgery [

8,

9] and then to physical therapy; full recovery after surgery is a two- to three-month painful and costly affair. If a more effective conservative treatment could treat both partial and full-thickness tears over the long term, it would meaningfully advance treatment options.

Yoga’s origins date back to the Indus Saraswati Valley nearly 5,000 years ago, where a flourishing civilization also gave origin to the first

Vedas and

Upanishads. The Sanskrit root ‘yuj,’ meaning to join or unite, suggests the spiritual goal of uniting an individual’s consciousness with a greater consciousness, and harmony between the body and mind. Such a goal requires attention to the body’s workings, and over the centuries, yoga has developed treatments for many medical conditions. However, contemporary yogic orthopedic treatments of the shoulder are generally global in nature, treating “shoulder pain,” rather than focusing on the specific conditions that affect the shoulder [

10,

11]. Yet the many causes of “shoulder pain” are anatomically distinct and effective treatments differ considerably. Those yogic treatments that do focus on rotator cuff are without confirmatory studies, and lack anatomical, kinesiological or even theoretical explanations of why they should be effective [

12]. The medical literature, conversely, focuses on orthopedic

injuries due to yoga, [

13] rather than seeking how people with these injuries might

benefit from yoga.

Rotator Cuff: Function and Dysfunction:

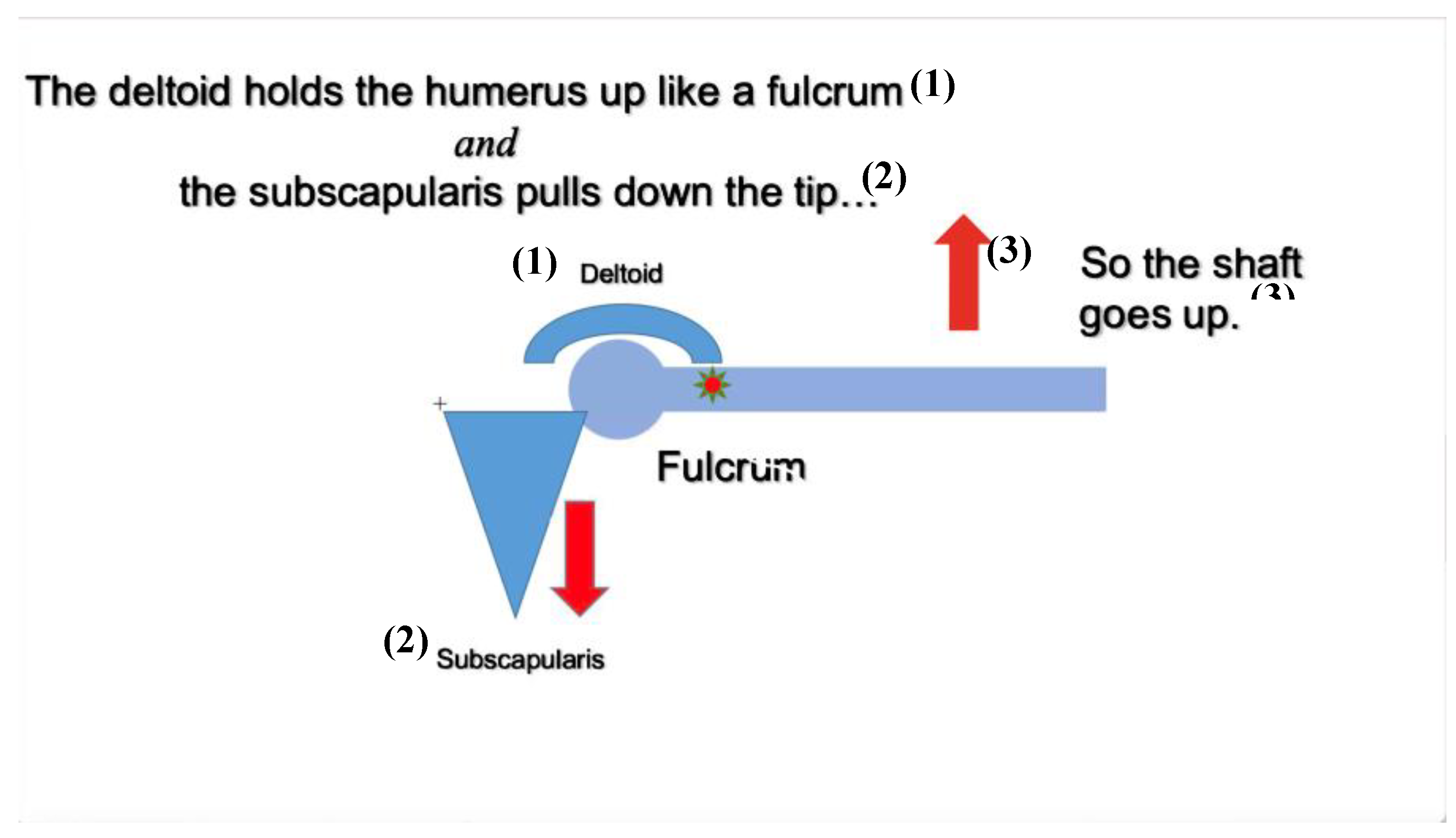

The supraspinatus is critical in normal shoulder abduction and flexion as the shoulder approaches horizontal. At 90° abduction or flexion, the deltoid’s fibers are pulling horizontally, without a vertical component. Therefore, it cannot lift the shoulder further on its own. Rather, abduction and flexion within the 80 – 110-degree range depend on the supraspinatus. If that muscle’s function is vitiated due to a partial or total tear, the deltoid’s efforts will only pull the humerus further into the glenoid fossa, causing considerable pain, but not further abduction or flexion.

A standing version of TFS done in the way specified below, activates the subscapularis, which pulls the head of the humerus downward while inducing the deltoid to hold its proximal shaft, thus cantilevering the distal humeral shaft upward in the 80° - 110° range, accomplishing the task without engaging the supraspinatus or infraspinatus. See

Figure 1 and

Figure 2. At the 110° angle the deltoid begins to have a vertical component to its force, and it continues the abduction or flexion to vertical. Indeed, one reliable test for RCS is to passively elevate the limb in question to 130° and then ask the patient to sustain it there and then abduct it further. If there is pain abducting or flexing in the 80°- 110° range, but beyond that level these motions are painless and complete, the injury is very likely rotator cuff syndrome.

This paper reports a randomized controlled test of the TFS’s utility and safety, and secondarily probes both the longevity of the improvement and the mechanism by which it succeeds.

Materials and Methods:

The study took place in private offices in Manhattan. Patient participation was limited to a single visit and remote follow-up 2 ½ or more years later.

Participants:

Males and females between the ages of 18 and 90 years were included in the study, provided they had MRI evidence of RCS, satisfied the inclusion criteria and did not meet the exclusion criteria. These criteria are consistent with current investigational standards [

14].

Exclusion Criteria:

Previous ipsilateral shoulder surgery.

Neuromuscular conditions such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, cerebrovascular accident or cerebral palsy affecting the ipsilateral shoulder.

Self-rated pain in abduction and flexion < 5/10 on the VAS.

Allocation Concealment:

Allocation into the two groups was done through random.org at the time the patient was admitted to the study. No patterns, list or other modifications of randomization were employed.

Examiner:

The examiner was a physician both boarded in PMR and IAYT certified as a yoga therapist.

Video Parameters:

A Panasonic HC-X1000 20X 4K video camera was set up on a tripod with center 8.5 feet from the subject, who was placed fully clad against a medium blue wall. The lens was 66 inches from the floor and recorded the patients’ facial expressions and bodily movements, which were then downloaded into an anonymized database.

Procedure:

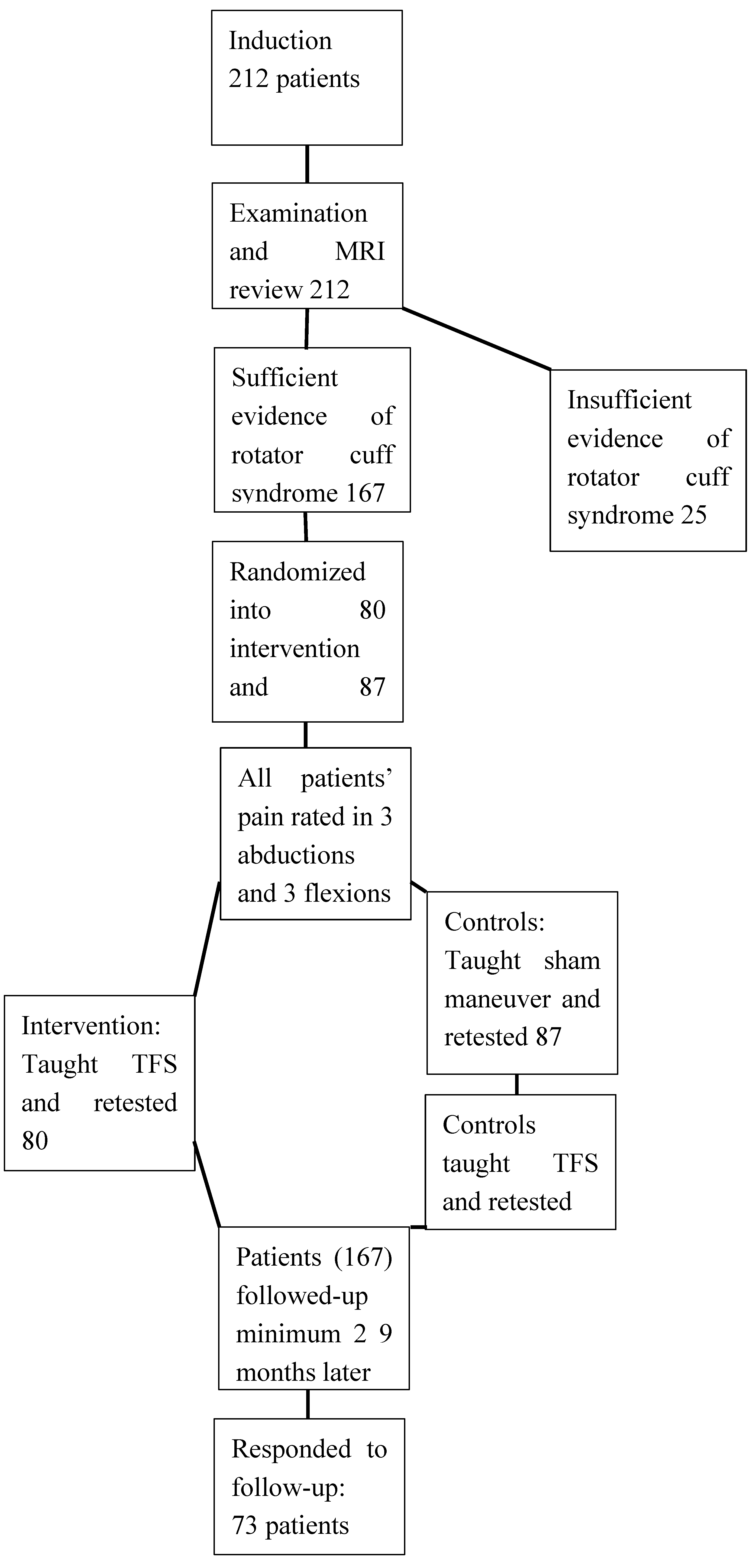

After signing the Informed Consent forms, patients were randomized by the medical assistant. We then described and demonstrated how they were to abduct and flex both shoulders maximally three times and report to us the maximum pain they felt during each trial. We then repeated what was in the Informed Consent form: that the procedure they were about to undergo might be the one we believed would remove the pain and increase the range of motion in their ailing shoulder

, or it might be a sham procedure. In other words, they might be in the intervention group (IG), or they might be given a sham maneuver, and be in the control group (CG). Since participants were initially blinded to their assignment into IG or CG, we made clear that this was a crossover study, and that CG patients would be given the actual intervention maneuver directly following the testing part of the sham procedure. We concluded the briefing by assuring participants that their efforts were anonymously recorded, and that AI would be used to develop an algorithm to help clinicians objectively determine the level of pain people were experiencing. We also received their written consent to show the videos of their abductions and flexions to students and clinicians, something that obviously could not be fully blinded. Follow-up was done a minimum of 29 months after the above procedure. See

Figure 1.

All subjects were filmed and their maximal pain recorded during each of three maximal bilateral abductions and flexions with straight elbows before and after either TFS or the placebo maneuver. The examiner performed each movement before the subject was asked to do it. Immediately following each abduction and each flexion, the subject stated his or her assessment of the most intense pain felt during that action on a 0-10 VAS scale. Full silence was maintained, apart from the verbal report of maximal pain felt by the subject. The examiner recorded these values.

After filming three abductions and flexions, patients in the IG were taught TFS, and patients in the CG were taught a sham procedure. The triple abductions and flexions were then repeated for all patients with the same filming and pain-scale rating procedure as before. At this point the intervention-group patients were finished with the study, except for the later follow-up. But at this point, just after the third abduction/flexion trial, the CG patients were taught TFS, followed by a third series of three flexion and abduction trials with VAS ratings and filming. See

Figure 3.

Signs and symptoms of adverse effects were monitored by the examiner after each intervention and each placebo maneuver, and at the close of each session.

Follow-up, including adverse effects was sought by three emails and three phone calls or Internet when necessary. In these remote follow-ups participants were asked to rate their pain with abduction and flexion as well as their ranges of motion, along with any relevant treatment, relevant medications or RCS-related mishaps they encountered involving the affected shoulders in the interim. They were also asked whether they continued to do the TFS maneuver after visiting our offices. Due to the COVID pandemic follow-up times were significantly increased. The mean follow-up time for was 4.3 years; range 29 – 60 months.

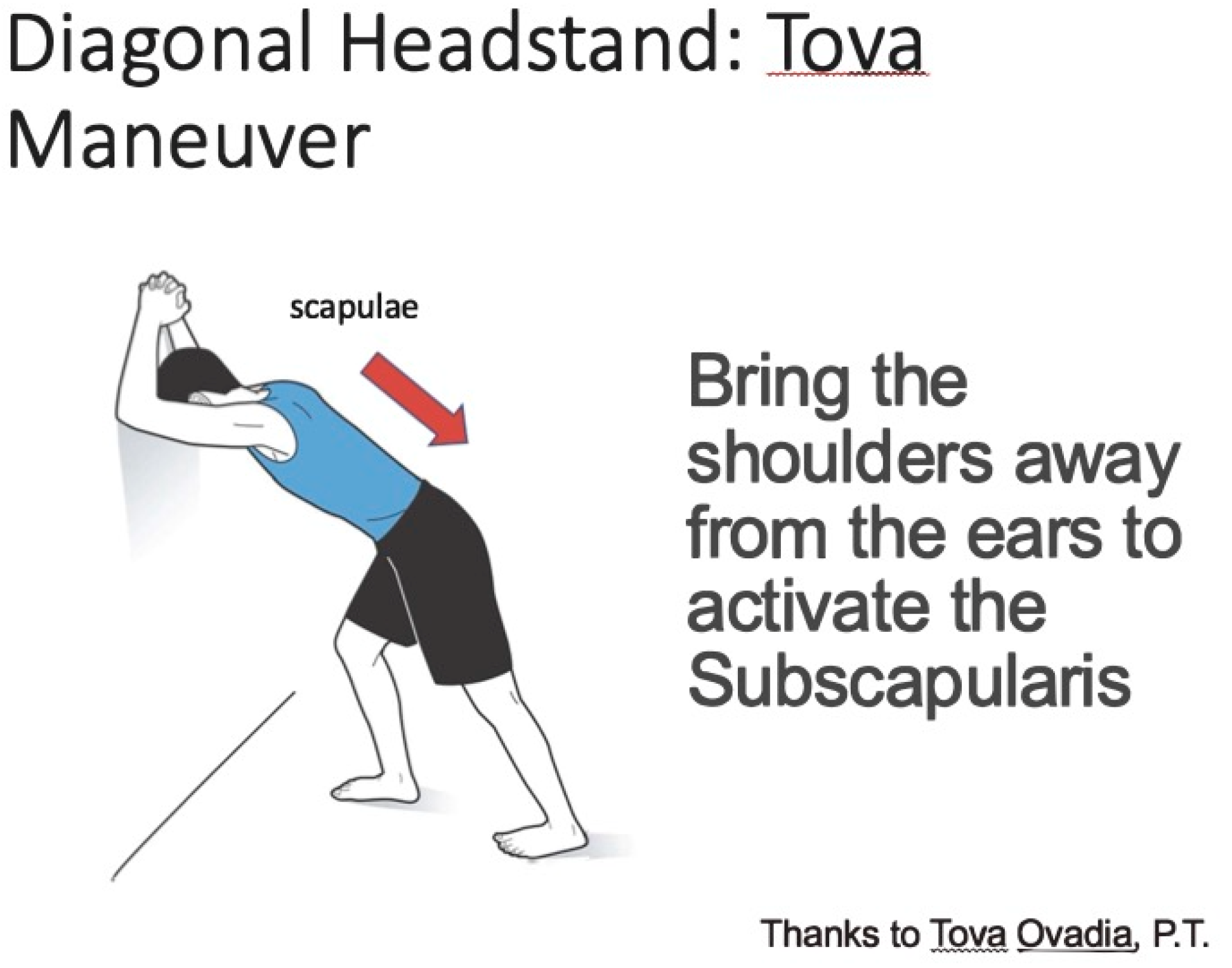

Details of the Procedure:

The TFS maneuver consists of folding one’s hands behind one’s head and placing forearms against a wall with head (fontanelles) in the center of the triangle made by the forearms, then pulling the shoulders away from the wall until the superior third of the trapezius and the supraspinatus are soft. See

Figure 1 and

Figure 2. The strategy behind using TFS is to activate the subscapularis muscle and then use it to pull the head of the humerus down as the deltoid holds its proximal shaft. The deltoid thus acts from above as a fulcrum. When the subscapularis pulls the head of the humerus caudally during abduction and flexion, it cantilevers the distal humerus’s shaft upward in the 80°-110° range in which the (torn) supraspinatus is usually active. After reaching 110° the deltoid has a vertical component and it contracts to lift the arm upward more powerfully.

Activation of the subscapularis was detected by means of the agonist-antagonist reflex: We worked with the patient until the supraspinatus and superior 1/3 of the trapezius were relaxed, indicating that the subscapularis was active. We did this by palpating these muscles just above the scapular spine. Control group participants were asked to interdigitate their hands in front of themselves with elbows straight and arms at a 45° angle for 45 seconds. The placebo maneuver was chosen because it did not activate the muscles of the rotator cuff yet was a plausible activity for healing the shoulder.

Immediately after performing the TFS maneuver or placebo maneuver for 45 seconds, patients were encouraged to “bravely, boldly, fearlessly” maximally abduct at the shoulder three times and then flex at the shoulders three times, with straight elbows. For an example of the TFS maneuver, readers are referred to the video on You Tube:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jzOsaE0Kyq8 . Participants were encouraged to access the pose on the website sciatica.org and do the pose with its guidance if pain came up again and/or persisted.

The demographic and study data used to support the findings of this study have been deposited in the Columbia University Academic Commons repository (Academic commons@columbia.edu)

Statistical Approach:

The sub-study for this paper involved alpha of .05 and power of 80%, and the assumption that the placebo group would differ from the intervention group by 25%. This assumption was based on an earlier paper studying the same maneuver [

15]. The calculated sample group sizes were 36 subjects in each group. The power sample size for the larger study of which this was a part was 100 subjects in each group; therefore, the study reported herein had quite low type I and type II error.

The three pre-maneuver (or pre-placebo) abduction and three pre-intervention (or pre-placebo) flexion scores given by the subjects were averaged separately, and differences between the pre- and post- maneuver (or placebo) scores were calculated. We averaged pain across the two arms for the two subjects who had RCS in both shoulders.

We used paired t-tests to compare each individual’s abduction and flexion pre- and immediately post-intervention pain scores with the same measurements for placebo [

16]. We also compared initial abduction and flexion pain scores, with pain measured at follow-up using the Wilcoxin rank sum test. Since the CG patients were given the actual intervention maneuver just minutes after receiving the placebo maneuver, it was not possible to compare treatment vs. placebo group in follow-up. At that point there was no placebo group. However, we analyzed the two groups’ follow-up interviews separately, finding no significant difference between the two.

Our data is part of a larger effort to develop an objective scale for pain through matching patient’s reports of pain on a 0 – 10 scale with videos of the subjects performing abduction and flexion.8 Patients with severe pain have a stereotyped facial response: the corners of the mouth descend and the outward corners of the eyes rise in an involuntary grimace. This can be qualitatively appreciated in the difference between what patients rate as 5/10 pain, often seen before the TFS maneuver, and afterwards, when pain is decreased. AI methods will quantify these facial changes and match them with similarly quantified bodily movements, which can be used to create an algorithm to objectively assign a pain score to a given patient’s response to abduction and flexion. Once perfected this algorithm may help clinicians decide objectively whether an individual requires opioids or less powerful analgesics and possibly help Medicine and Surgery to select procedures that generally induce less pain.

Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the XXX, and conducted between December 20, 2017 and December 24, 2022, after a nearly three-year suspension due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, approved by the CIRBI IRB, now Advarra. This study conforms to all CONSORT and CLARIFY guidelines and reports the required information accordingly (see Supplementary Checklist). CLARIFY guidelines were utilized in the preparation of this report.

Results:

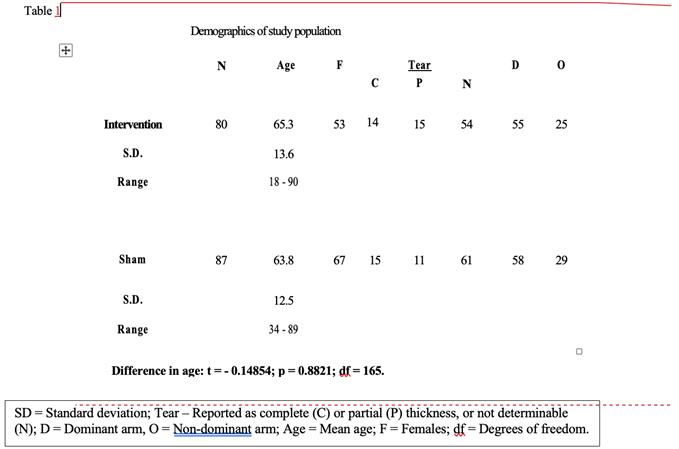

We recruited 212 patients, of whom 167 completed the procedure properly. There were 80 intervention and 87 control-plus-intervention patients with mean age of 66.7 years. See

Table 1. No patients were lost to the immediate follow-up since the single intervention and assessment immediately followed the selection. The 3-year clinical effort abruptly came to an end in March, 2020 with the Covid pandemic. Seventy-three patients responded to the mean 52 months’ post-intervention inquiries.

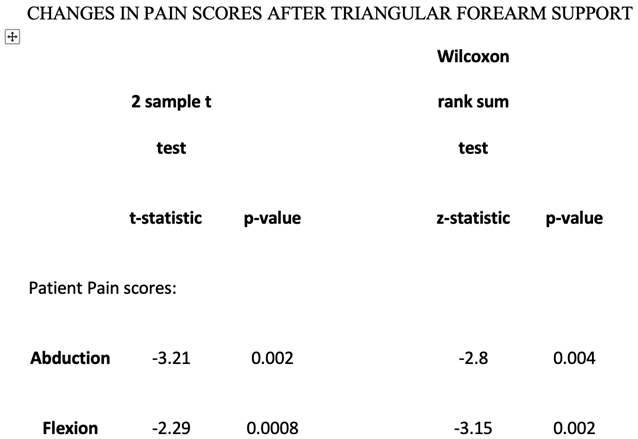

We first averaged each patient’s three pre-intervention or placebo pain scores and also averaged each patient’s three post intervention or post placebo scores. Then we computed the difference between the averaged pre- and post- scores for each patient. Then we took the mean of all the IG and all the CG patients’ computed differences that we had found between pre- and post- intervention or placebo. Mean IG pain scores for abduction and flexion were immediately reduced post TFS 1.98 and 1.64 points from initial values of 6.14 and 5.13 respectively, (CI: .0526; .0438) a reduction of 32.3% and 32.0 %. In contrast, mean CG pain scores for abduction and flexion were immediately reduced from 5.03 and 4.57 by 1.08 and .93 points, (CI: .0513; .0357), 21.5% and 21.4%, respectively. T-test values for IG vs. CG pain scores for abduction and flexion were p < .002 and .008 respectively, and Wilcoxon rank sum test values were p < .004 and p < .002 respectively. When the CG patients were given TFS immediately thereafter, their mean VAS scores were further reduced by 1.25 and 1.29 (CI: .0423; .0383), 24.9% and 28.2% respectively, (p = 0.001; p = 0.001.) See

Table 2 and

Table 3.

These values are calculated from the corresponding data in

Table 2.

We also recorded whether the tears were full thickness or partial thickness, and whether they were in dominant or non-dominant arm. The effects of TFS were not significantly different when grouped by nature of the tear of the supraspinatus or infraspinatus. Also, the differences in outcomes where the dominant vs. non-dominant upper extremity were affected were insignificant.

Mean 52 months’ telephone or Internet follow-up (range: 29 – 60) found that 3 of 73 patients required surgery, 3 had platelet rich plasma (PRP) injections and 13 of the 73 responding patients received further physical therapy. Of the 54 patients without confounding events or further treatment, abduction VAS scores in flexion and abduction were 1.50 and 1.25 (SD 2.50; 2.25) respectively as compared with study-start values of 6.14 and 5.13, giving improvement from baseline of 75.6% and 75.6% respectively. See

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6 and Supplementary

Table 2. The 54 unconfounded subjects’ abduction pain decreased from a mean of 2.45 (SD=2.34) post-intervention to 1.53 (SD=2.28) at follow-up (mean improvement of 0.92 points (95% CI 0.13 to 1.71) p=0.02). These patients’ flexion pain decreased from a mean of 2.17 (SD=2.26) post-intervention to 1.04 (1.79) at follow-up, a mean improvement of 1.13 points (95% CI 0.54 to 1.73), p < 0.001).

Since follow-up was by telephone or Internet, range of motion for abduction and flexion were quantitative, but self-reported. Goniometric assessment was unfortunately impossible remotely. Abduction and flexion ranges of motion were reported as normal (180 degrees abduction and flexion) by 29 and 32 patients, respectively, or 54% and 54% respectively. When questioned about abduction, 46/54 had limitations < 3/10. For flexion 49/54 had limitations of range of motion <3/10.

Adverse effect: One patient who did not improve complained of significant pain following TFS. She refused MRI or any other follow-up. Apart from this, no adverse side effects from the procedures were seen or reported.

Discussion:

The improvement with TFS is significant in the academic sense but is it clinically significant? Farrar, et al. [

17] point out that gaining points on a Likert-type scale may have very different clinical impact but state that 2 points or 30% gains are usually impactful. To this end we have included the initial scores, which lie in the middle range: 5 – 6/10 in either abduction or flexion or both. People’s pain levels improved more than 66% over the years between study entry and follow-up. See

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6.

The 2/3 overall mean improvement in the follow-up period is contrary to the natural history of rotator cuff describes worsening over time, degenerating into a surgical condition [

3,

18,

19,

20]. The remote nature of the follow-up vitiates the accuracy, to be sure, but the fact that so many participants find themselves better is in direct contrast to what is expected without effective treatment.

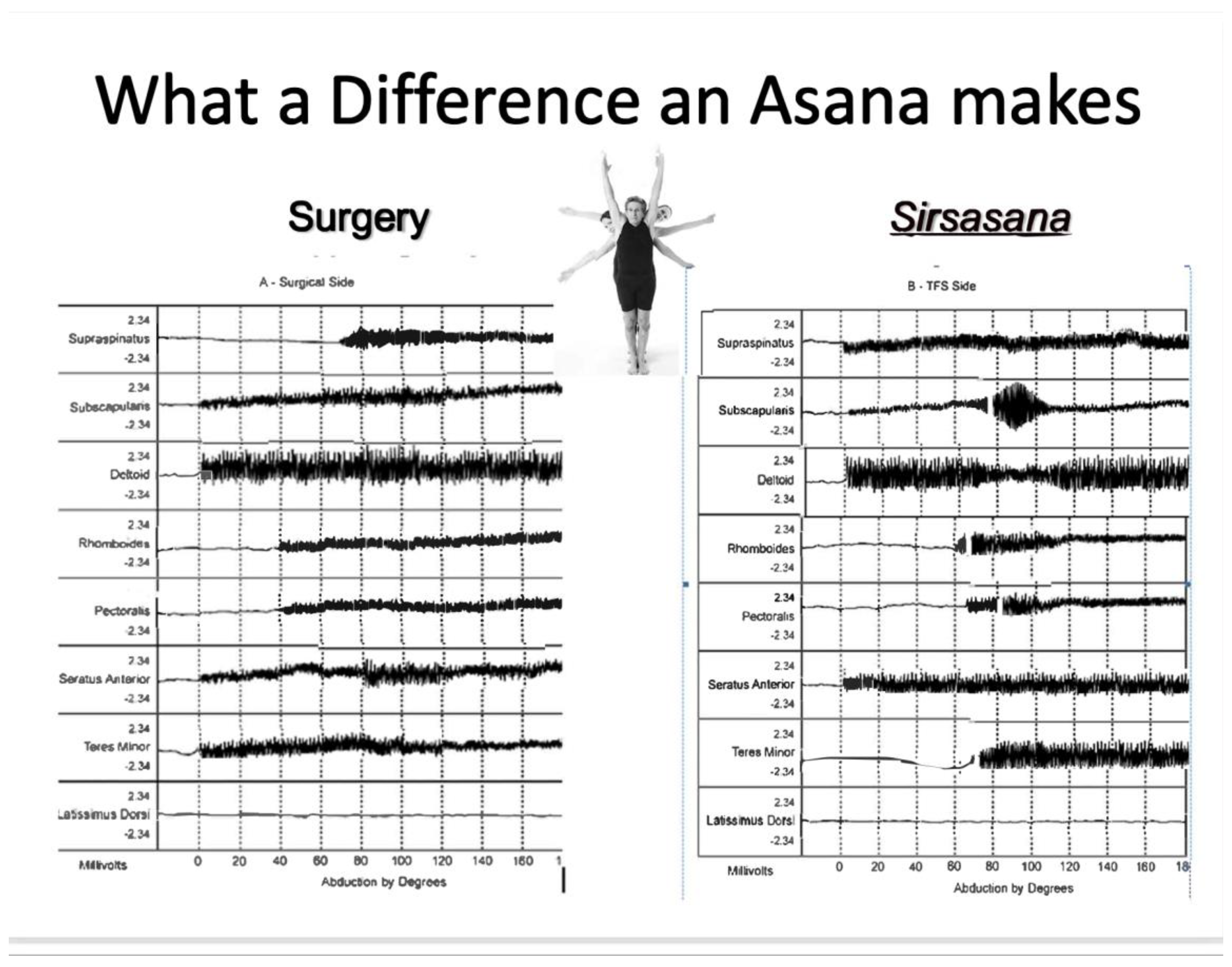

Summary of Abduction/Flexion Kinetics After TFS

Better to understand how this version of TFS initiated this rapid change in function, and translate the anatomy and kinesiology into clinical reality, we studied TFS with 8-channel EMG. While the supraspinatus muscle normally lifts the humerus from 80°-110°, in RCS it is torn and has no part in the action, with just mild continuous activity throughout abduction. The subscapularis’ spindle-like EMG record denotes heightened activity exactly between 80°-110°, where the deltoid’s effect on abduction and flexion is virtually null. See

Figure 4.

This analysis is supported by the fact that the severity of the supraspinatus tear (more than 50% vs. less than 50%) was unrelated to the degree of improvement in pain: after TFS it appears uninvolved in shoulder abduction or flexion. The efficacy of TFS with nondominant as well as dominant limbs suggests that the maneuver does not particularly depend on dexterity or strength either but rather it replaces a torn muscle’s function with another muscle used in a different way, but with similar results – full abduction and flexion with significantly less or no pain, giving long term relief.

Strategic Use of TFS

TFS was ideal for the larger pain-study seeking an objectively measurable marker of pain because it changed pain status in less than 2 minutes, enabling contrast and comparison of the painful and pain-relieved states without intervening variables that medications or surgery or even time itself might introduce. The clinical significance of this maneuver, however, depends on its longevity. Previously we followed 50 patients for 30 months and found that 94% of the patients doubled their flexion and abduction ranges and reduced their pain more than 80% throughout the 30 months [

15]. In that study RCS patients repeated the TFS maneuver daily for a few weeks, but then the shoulder stayed painlessly high functioning without further intervention for the 2.5 - 5 years during which we studied them. See

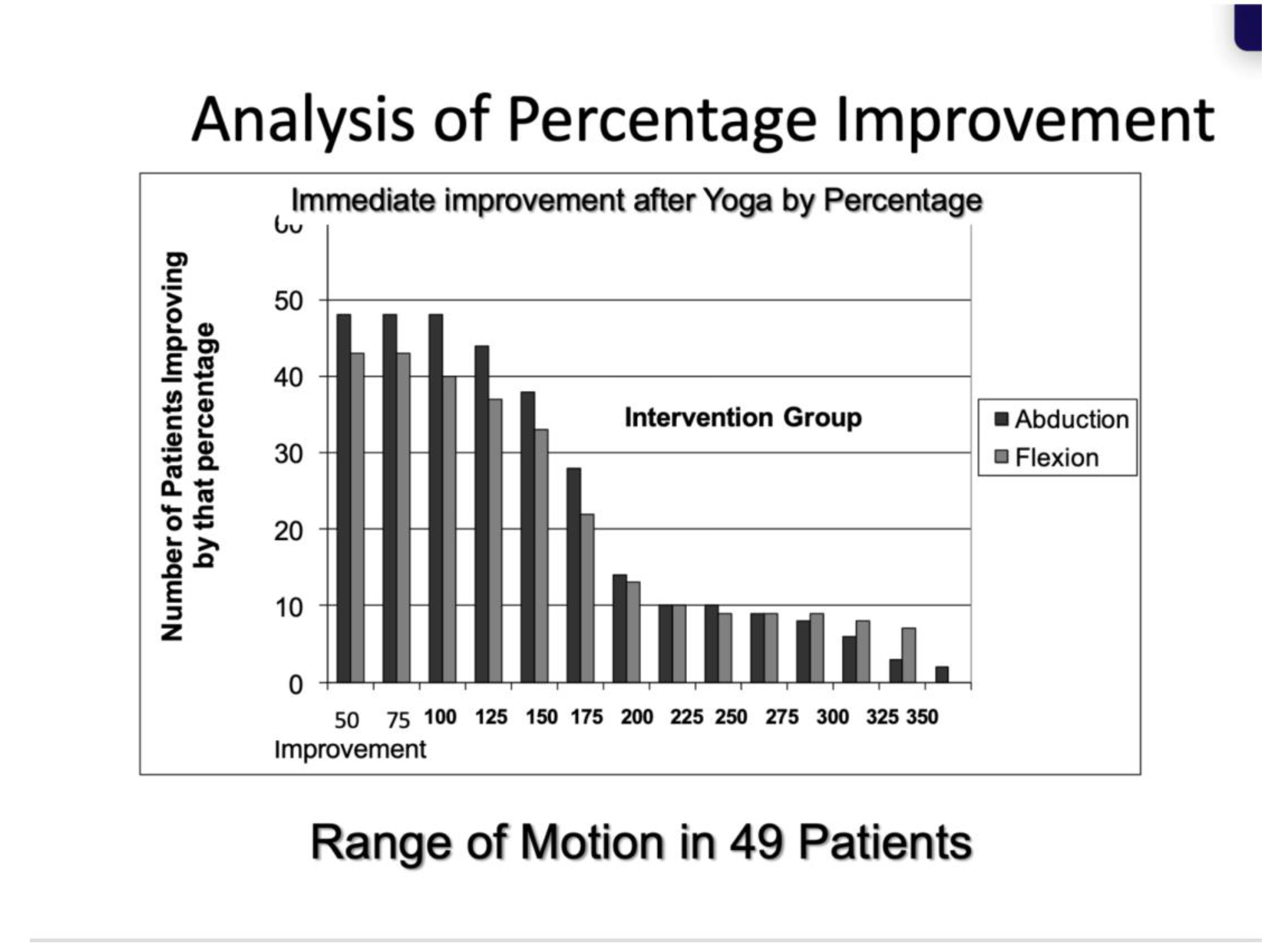

Figure 5. In this study we used telephone, email and Internet to communicate with patients more than 2 years after the single initial intervention.

The long-lasting effect of TFS may be a case of muscle re-learning, or operant conditioning,15 a non-conscious adaptation in which patients spontaneously choose the painless cantilevering action of the subscapularis for abducting and flexing the shoulder over the ineffective and painful use of the torn supraspinatus which patients had used all their lives previously. In classical operant conditioning language, using the TFS – related method of abduction and flexion offers the “reward” of being able to raise the arm as the individual intends, and the removal of the “positive punishment” of pain.

Strengths of the Study:

The immediate crossover of the control group to the intervention procedure enables direct before-after comparison in the intervention group and comparison with the control group scores. Application of the intervention maneuver equally to partial and full thickness tears, and the analysis of the effects permits the maneuver to be used with both groups, unlike earlier studies that validated a conservative method only with partial thickness tears [

8,

9].

The long follow-up is informative of the long-term benefit of TFS.

Explicit permission was received from all patients to have the video recordings of maneuvers and trials seen as the study intended. This enabled later confirmation of pain scores by a wider selection of assessors including blinded college students, physical therapists, yoga therapists and physicians. This helps refine the objective pain-assessment algorithm that gives an objective 0-10 score for pain. Facial changes at each patient’s different pain-states have been digitized; AI will match the digitized facial movements seen in the videos with the refined estimated of the pain scores, and will thereby be able to give a pain score for other people performing this and possibly many other maneuvers [22]. The algorithm may be valuable for clinicians determining whether a given patient warrants opioid or non-opioid medications, and as such may help diminish the opioid dependency epidemic. The algorithm may also be valuable for determining which of two or more procedures or treatments is more humane or even more applicable, e.g., whether a given patient’s pain warrants back surgery.

The generalizability of the maneuver is suggested by its efficacy in the two main types of rotator cuff syndrome, its applicability to dominant and non-dominant arms and its success across the age spectrum. Since the torn supraspinatus is not involved in abduction or flexion after TFS, fatty change of the two supraspinatus fragments after total tear would not be a deterring factor here.

Shortcomings of the Study:

The relatively small sample size is lamentable. Larger studies are clearly desirable. Patient-reported estimates of range of motion in the follow-up would clearly be improved by clinically-administered goniometric measurement. Delineation of patients’ prior knowledge of yoga would have been helpful to determine whether knowledge of yoga is advantageous (or disadvantageous) for TFS’s application.

Comparison with standard functional measures such as Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI) and the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) scores are absent and would give a fuller picture of TFS’s capacities to reverse the deficits seen in RCS.

The absence of a non-crossover control group makes long-term follow-up of untreated patients impossible. This would clearly be desirable.

A more uniform follow-up schedule would also be an improvement to the broadly timed follow-up in this study.

Fortunately, the natural history of RCS has been studied [

3,

18,

19,

20]. The majority of studies that follow untreated painful cuff tears or asymptomatic tears that are monitored at regular intervals show slow progression of tear enlargement and muscle degeneration over time [

18,

19,

20].

Another major drawback to the study is the low long-term response rate. We believe the prolongation of the interval between seeing the participants and doing the follow-up due to the COVID-19 pandemic is part of the reason for this. Future studies can improve on this with more timely and more focused serial follow-ups.

A second totally blinded observer’s input for pain scores would help validate the results both at the initial and follow-up visit. Since recruitment of the subscapularis changes the kinetics of abduction and flexion, it is possible that arthritis of the joint will be accelerated by TFS. Long term imaging follow-up with a larger sample would be desirable here too.

Conclusion:

TFS may be an effective, inexpensive and widely applicable means of improving patients’ range of motion and reducing their pain in full - and partial-thickness tears of RCS.

Supplementary data

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, All supportive data is available at the Columbia University Academic Commons repository (Academic commons@columbia.edu). There are two files, one with the original data at the time of visit. The second file has follow-up data obtained a minimum of 29 months later. Access is unrestricted. The authors acknowledge Tova Ovadia, PT for inventing this application of TFS and Eugenia Buta of Yale University, for their assistance in this paper.

Funding

National Institutes of Health under Awards Number R21NR016510

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study is registered in Clinical Trials.gov as NCT 04833244. CIRBI, now Advarra, Number Pro00041168.

Informed Consent Statement

Each patient in this study or their guardian has given written informed consent to be a participant.

Data Available Statement

All supportive data is available at Columbia Commons There are two files, one with the original data at time of visit. The second file is the follow-up data collected a minimum of 29 months after the initial visit. Access to the data is unrestricted.

Conflicts of Interests

Neither Loren Fishman nor Bernard Rosner have any conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Reilly P, Macleod I, Macfarlane R, Windley J, Emery RJ. Dead men and radiologists don't lie: a review of cadaveric and radiological studies of rotator cuff tear prevalence.Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2006;88(2):116-121. [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto A, Takagishi K, Osawa T, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of a rotator cuff tear in the general population. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(1):116-120. [CrossRef]

- Tashjian RZ. Epidemiology, natural history, and indications for treatment of rotator cuff tears. Clin Sports Med. 2012;31(4):589-604. [CrossRef]

- Lenza M, Buchbinder R, Takwoingi Y, Johnston RV, Hanchard NC, Faloppa F. Magnetic resonance imaging, magnetic resonance arthrography and ultrasonography for assessing rotator cuff tears in people with shoulder pain for whom surgery is being considered. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2013(9):CD009020. Published 2013 Sep 24. [CrossRef]

- Teefey SA, Hasan SA, Middleton WD, Patel M, Wright RW, Yamaguchi K. Ultrasonography of the rotator cuff. A comparison of ultrasonographic and arthroscopic findings in one hundred consecutive cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82(4):498-504.

- Read JW, Perko M. Shoulder ultrasound: diagnostic accuracy for impingement syndrome, rotator cuff tear, and biceps tendon pathology. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1998;7(3):264-271. [CrossRef]

- Iannotti JP, Ciccone J, Buss DD, et al. Accuracy of office-based ultrasonography of the shoulder for the diagnosis of rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am.2005;87(6):13051311. [CrossRef]

- Schemitsch C, Chahal J, Vicente M, et al. Surgical repair versus conservative treatment and subacromial decompression for the treatment of rotator cuff tears: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Bone Joint J. 2019;101-B(9):1100-1106. [CrossRef]

- Jeanfavre M, Husted S, Leff G. Exercise therapy in the non-operative treatment of full thickness rotator cuff tears: a systematic review. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2018 Jun; 13(3): 335–378. [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Joelle J. Ten minute exercises for shoulder pain and bursitis. YouTube. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TQMkXZzcQl8.

- Adriene A. Yoga with Adriene for shoulder pain. Yoga with Adriene for the shoulder. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SedzswEwpPw.

- Garving C, Jakob S, Bauer I, Nadjar R, Brunner UH. Impingement Syndrome of the Shoulder. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2017;114(45):765-776. [CrossRef]

- Lee M, Huntoon EA, Sinaki M. Soft Tissue and Bony Injuries Attributed to the Practice of Yoga: A Biomechanical Analysis and Implications for Management. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94(3):424-431. [CrossRef]

- Hopewell S, Keene DJ, Marian IR, et al. Progressive exercise compared with best practice advice, with or without corticosteroid injection, for the treatment of patients with rotator cuff disorders (GRASP): a multicentre, pragmatic, 2 × 2 factorial, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2021;398(10298):416-428. [CrossRef]

- Fishman LM, Wilkins AN, Ovadia T, Konnoth C, Rosner B, Schmidhofer S. Yoga-Based Maneuver Effectively Treats Rotator Cuff Syndrome. Topics in Geriatric Rehabilitation: April/June 2011 - Volume 27 - Issue 2 - p 151-161. [CrossRef]

- Bridge PD, Sawilowsky SS. Increasing Physicians’ Awareness of the Impact of Statistics on Research Outcomes: Comparative Power of the t-test and Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test in Small Samples Applied Research. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology Volume 52, Issue 3, March 1999, Pages 229-235.

- Farrar JT, Young JP Jr, LaMoreaux L, Werth JL, Poole MR. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. Pain. 2001;94(2):149-158. [CrossRef]

- Matava MJ, Purcell DB, Rudzki JR. Partial-thickness rotator cuff tears. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(9):1405-1417. [CrossRef]

- Neer CS 2nd. Impingement lesions. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;(173):70-77.

- Hsu J, Keener JD. Natural History of Rotator Cuff Disease and Implications on Management. Oper Tech Orthop. 2015;25(1):2-9. [CrossRef]

- Skinner, B. F. Two types of conditioned reflex and a pseudo type. Journal of General Psychology, 1935; 12, 66-77.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).