Submitted:

01 July 2025

Posted:

02 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PM | Pectoralis minor |

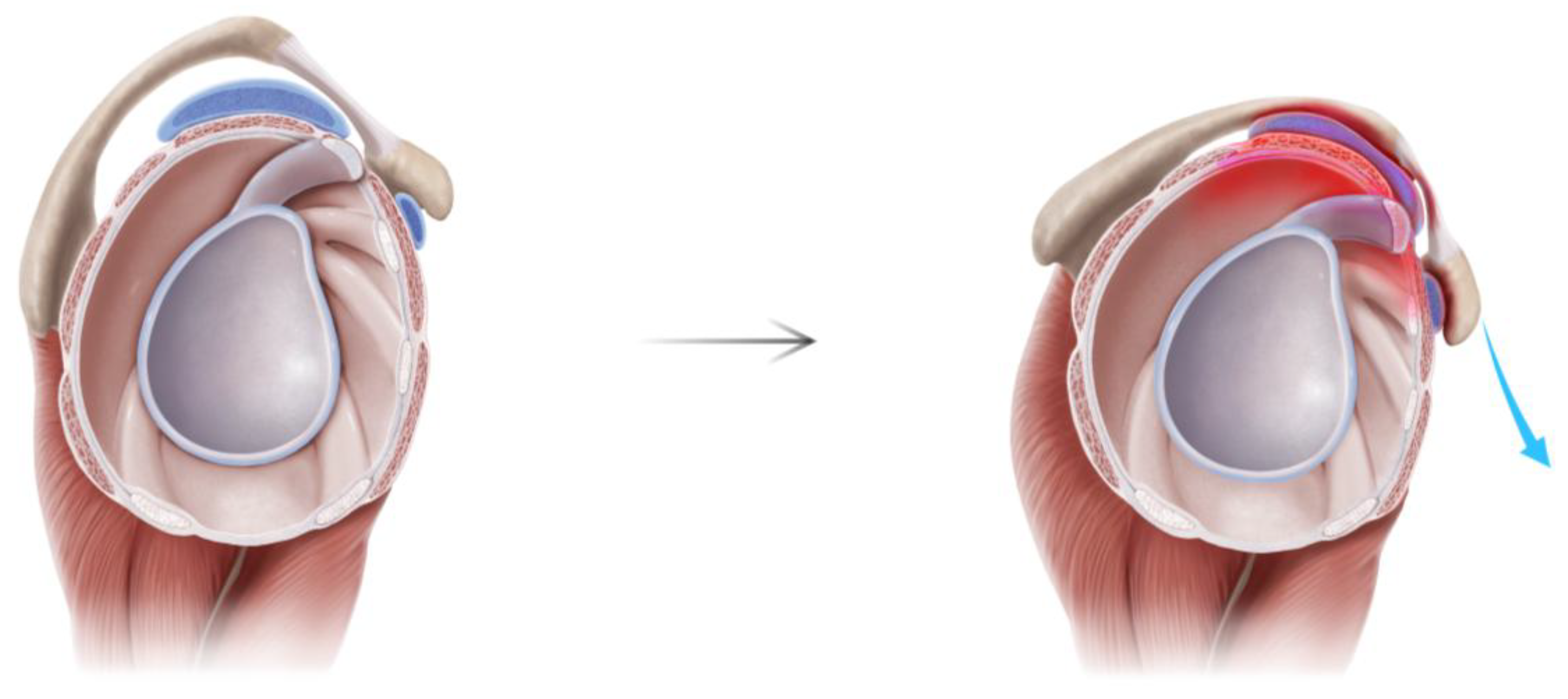

| SAPS | Subacromial pain syndrome |

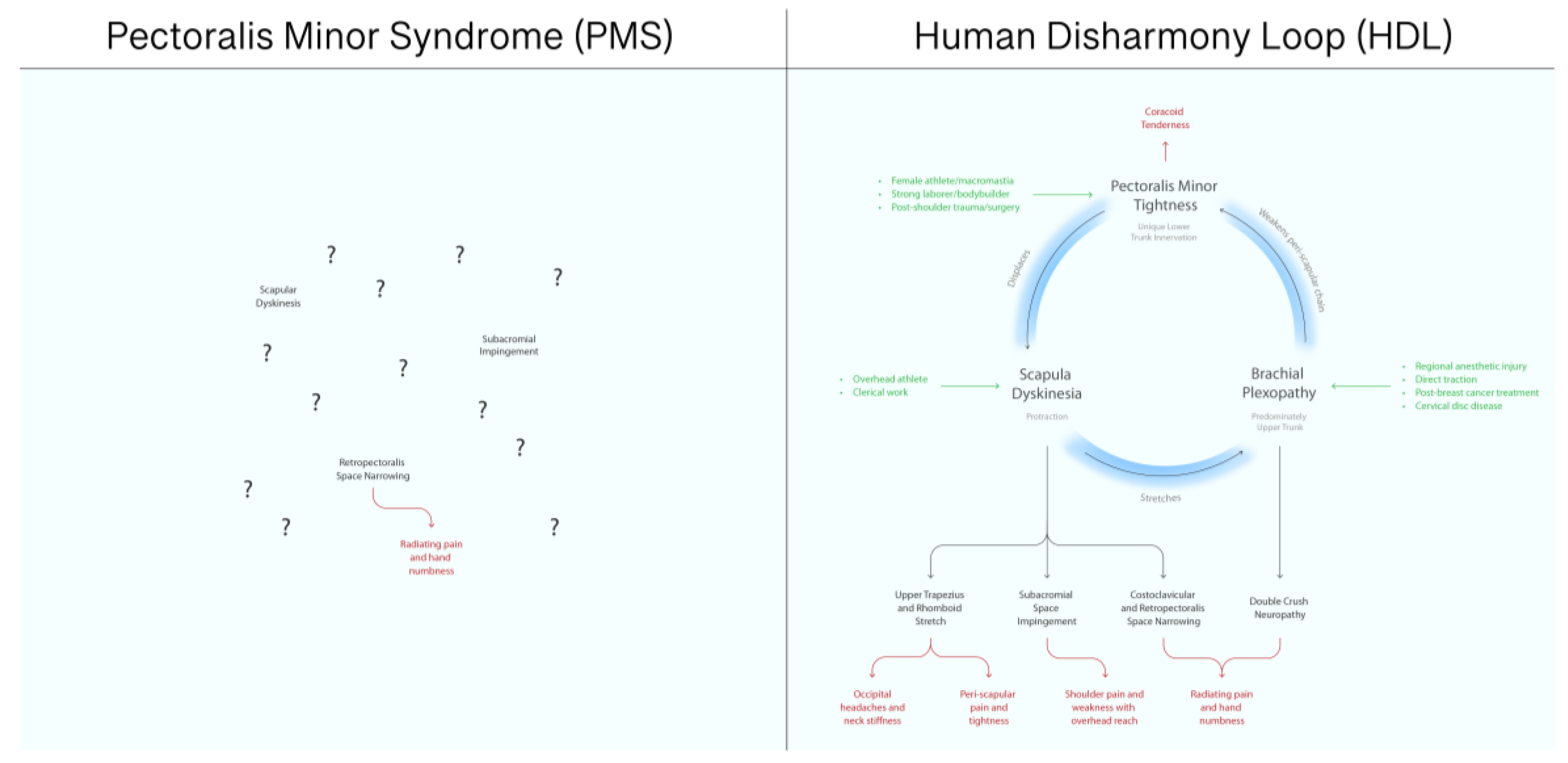

| HDL | Human disharmony loop |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| ROM | Range of motion |

| CA | Coraco-acromial |

| AC | Acromio-clavicular |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

| TSA | Total shoulder arthroplasty |

| SLAP | Superior Labrum Anterior Posterior |

References

- Greenberg, D.L. Evaluation and treatment of shoulder pain. Med Clin North Am 2014, 98, 487–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, E.H.; Aibinder, W.R. Shoulder Impingement Syndrome. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 2023, 34, 311–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucas, J.; van Doorn, P.; Hegedus, E.; Lewis, J.; van der Windt, D. A systematic review of the global prevalence and incidence of shoulder pain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2022, 23, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garving, C.; Jakob, S.; Bauer, I.; Nadjar, R.; Brunner, U.H. Impingement Syndrome of the Shoulder. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2017, 114, 765–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brattberg, G.; Parker, M.G.; Thorslund, M. The prevalence of pain among the oldest old in Sweden. Pain 1996, 67, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, K.; Ditsios, K.; Middleton, W.D.; Hildebolt, C.F.; Galatz, L.M.; Teefey, S.A. The demographic and morphological features of rotator cuff disease. A comparison of asymptomatic and symptomatic shoulders. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006, 88, 1699–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myklebust, G.; Hasslan, L.; Bahr, R.; Steffen, K. High prevalence of shoulder pain among elite Norwegian female handball players. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2013, 23, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umer, M.; Qadir, I.; Azam, M. Subacromial impingement syndrome. Orthop Rev (Pavia) 2012, 4, e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consigliere, P.; Haddo, O.; Levy, O.; Sforza, G. Subacromial impingement syndrome: management challenges. Orthop Res Rev 2018, 10, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neer, C.S. , 2nd. Anterior acromioplasty for the chronic impingement syndrome in the shoulder: a preliminary report. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1972, 54, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, K.S. Subacromial Impingement Syndrome of the Shoulder: A Musculoskeletal Disorder or a Medical Myth? Malays Orthop J 2019, 13, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, A.K.; Flatow, E.L. Subacromial impingement syndrome. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2011, 19, 701–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, M.A.; Arons, R.R.; Hurwitz, S.; Ahmad, C.S.; Levine, W.N. The rising incidence of acromioplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010, 92, 1842–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorrestijn, O.; Stevens, M.; Winters, J.C.; van der Meer, K.; Diercks, R.L. Conservative or surgical treatment for subacromial impingement syndrome? A systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2009, 18, 652–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebremariam, L.; Hay, E.M.; Koes, B.W.; Huisstede, B.M. Effectiveness of surgical and postsurgical interventions for the subacromial impingement syndrome: a systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2011, 92, 1900–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karjalainen, T.V.; Jain, N.B.; Page, C.M.; Lahdeoja, T.A.; Johnston, R.V.; Salamh, P.; Kavaja, L.; Ardern, C.L.; Agarwal, A.; Vandvik, P.O.; et al. Subacromial decompression surgery for rotator cuff disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019, 1, CD005619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahdeoja, T.; Karjalainen, T.; Jokihaara, J.; Salamh, P.; Kavaja, L.; Agarwal, A.; Winters, M.; Buchbinder, R.; Guyatt, G.; Vandvik, P.O.; et al. Subacromial decompression surgery for adults with shoulder pain: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 2020, 54, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diercks, R.; Bron, C.; Dorrestijn, O.; Meskers, C.; Naber, R.; de Ruiter, T.; Willems, J.; Winters, J.; van der Woude, H.J.; Dutch Orthopaedic, A. Guideline for diagnosis and treatment of subacromial pain syndrome: a multidisciplinary review by the Dutch Orthopaedic Association. Acta Orthop 2014, 85, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beard, D.J.; Rees, J.L.; Cook, J.A.; Rombach, I.; Cooper, C.; Merritt, N.; Shirkey, B.A.; Donovan, J.L.; Gwilym, S.; Savulescu, J.; et al. Arthroscopic subacromial decompression for subacromial shoulder pain (CSAW): a multicentre, pragmatic, parallel group, placebo-controlled, three-group, randomised surgical trial. Lancet 2018, 391, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahal, J.; Mall, N.; MacDonald, P.B.; Van Thiel, G.; Cole, B.J.; Romeo, A.A.; Verma, N.N. The role of subacromial decompression in patients undergoing arthroscopic repair of full-thickness tears of the rotator cuff: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthroscopy 2012, 28, 720–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Miao, L.; Zhang, P.; Wang, W.L. Does concomitant acromioplasty facilitate arthroscopic repair of full-thickness rotator cuff tears? A meta-analysis with trial sequential analysis of randomized controlled trials. Springerplus 2016, 5, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karjalainen, T.V.; Jain, N.B.; Heikkinen, J.; Johnston, R.V.; Page, C.M.; Buchbinder, R. Surgery for rotator cuff tears. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019, 12, CD013502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cools, A.M.; Michener, L.A. Shoulder pain: can one label satisfy everyone and everything? Br J Sports Med 2017, 51, 416–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J. The End of an Era? J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2018, 48, 127–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigliani, L.U.; Levine, W.N. Subacromial impingement syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1997, 79, 1854–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

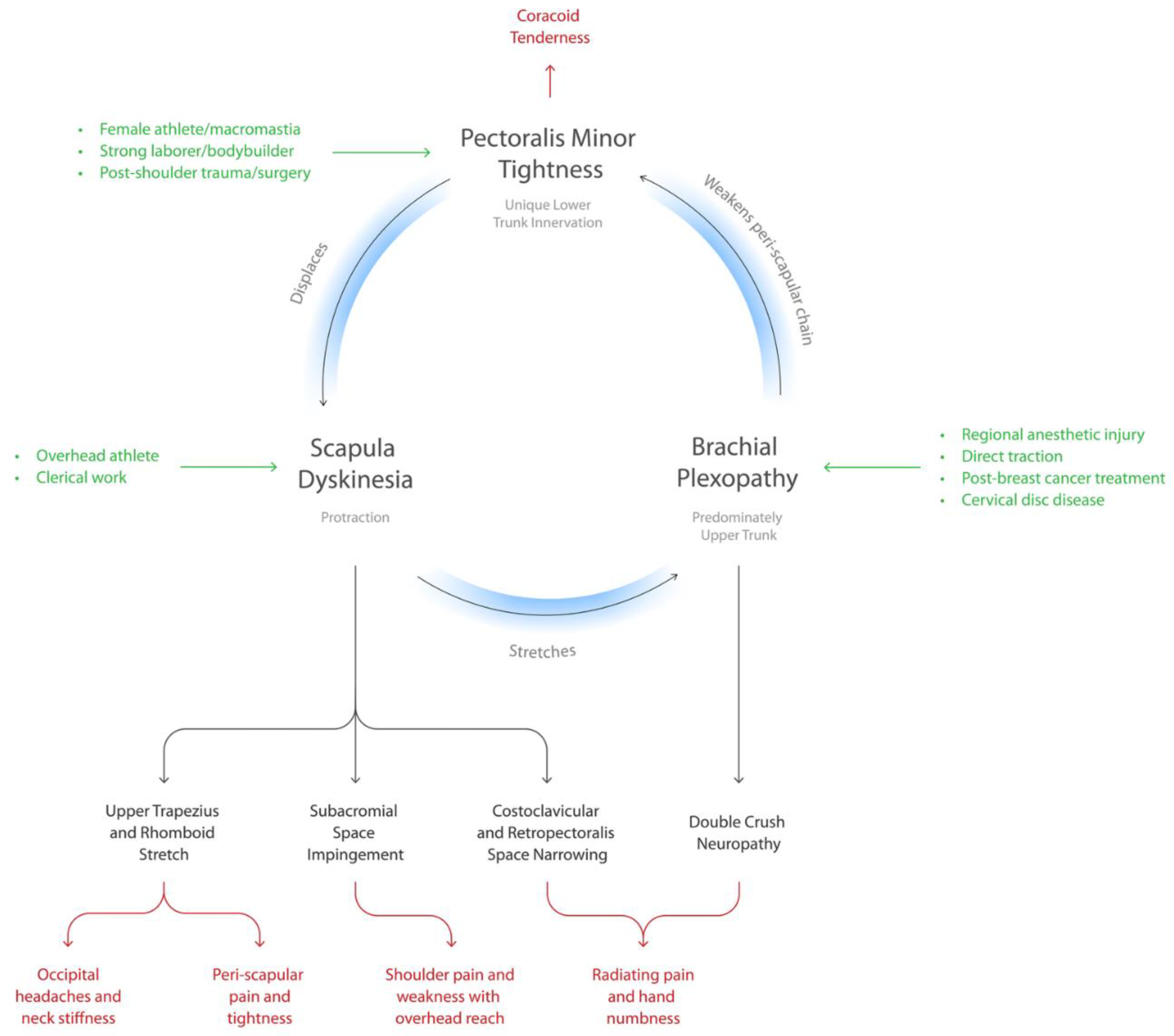

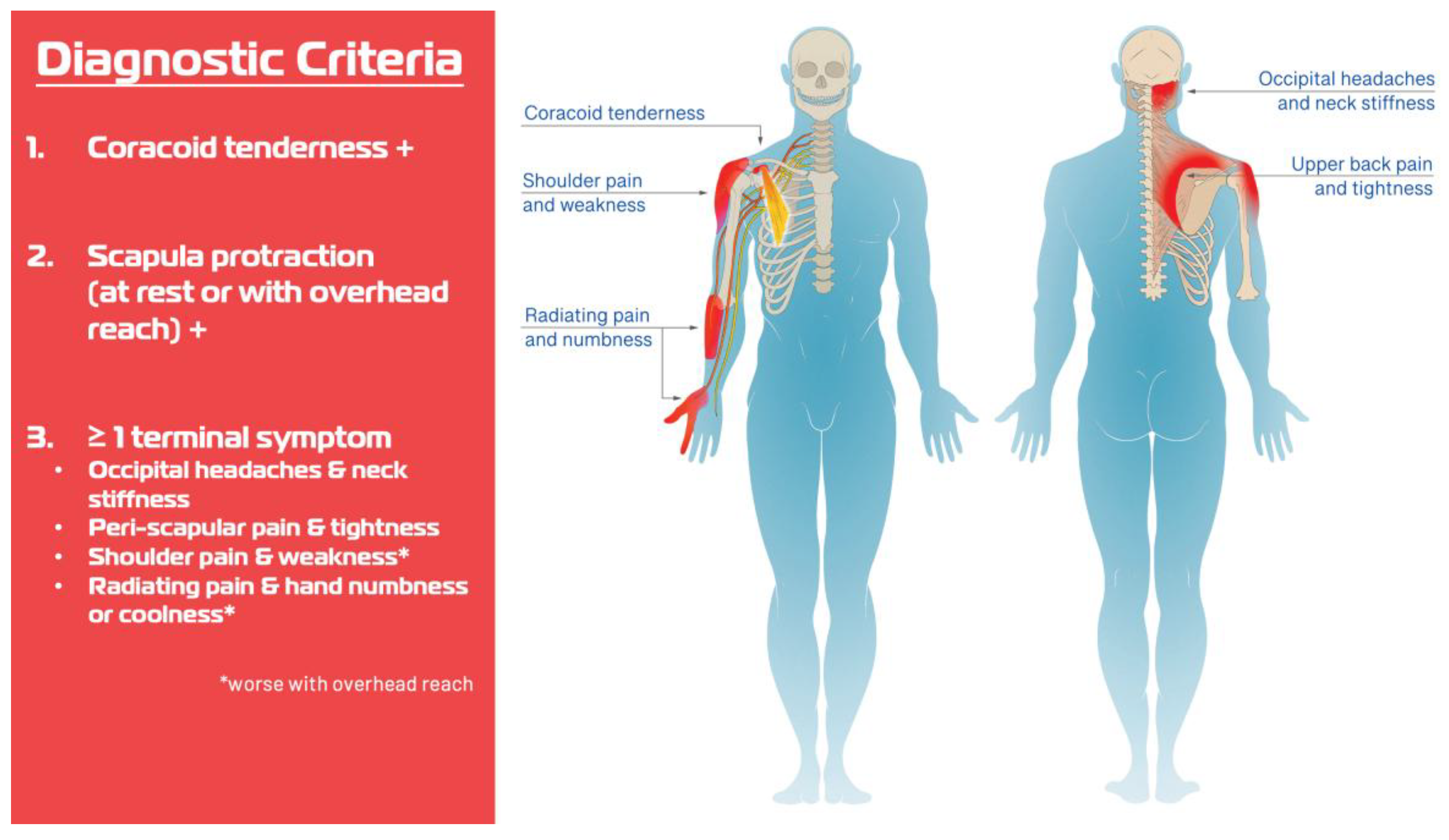

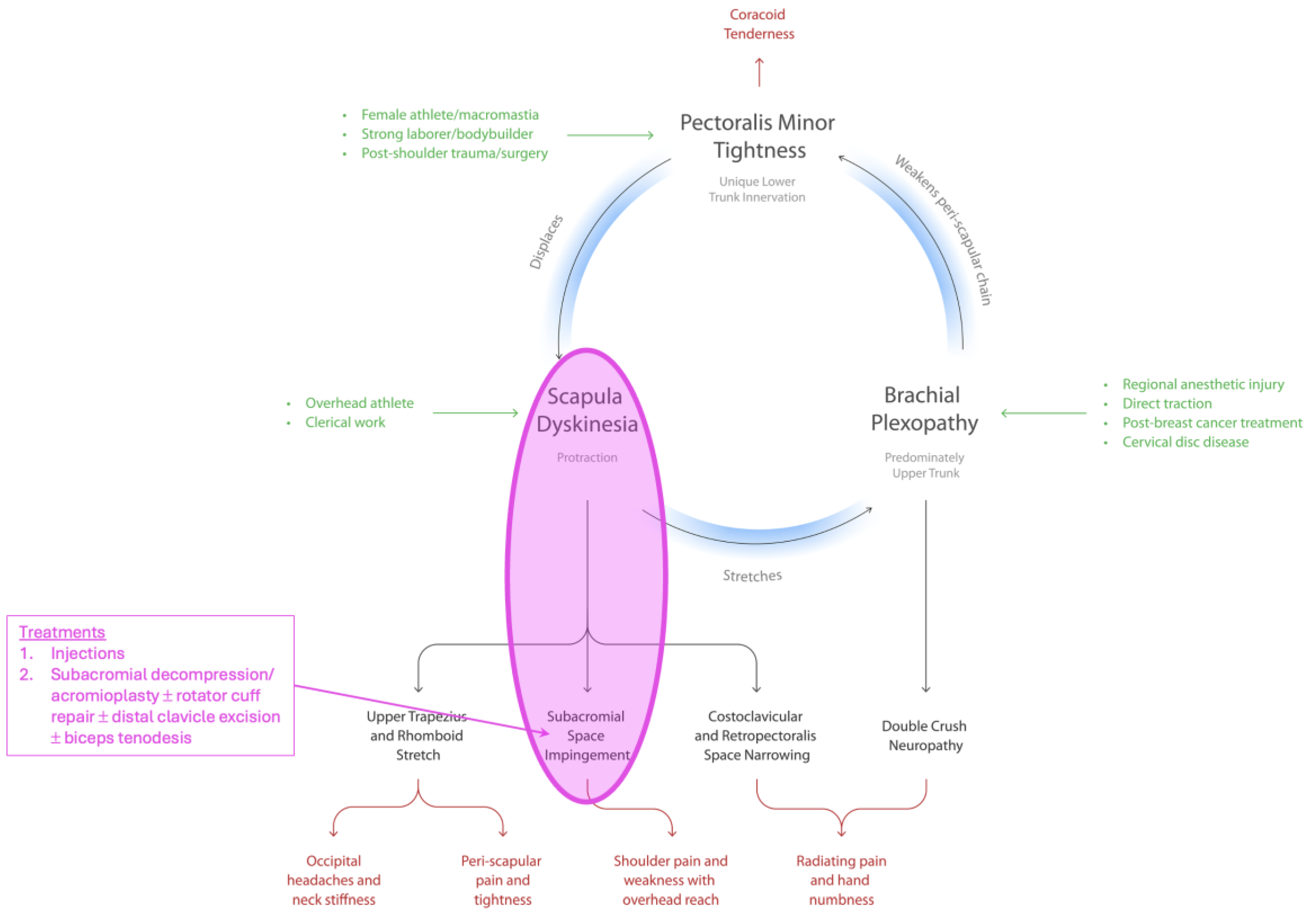

- Sharma, K.; Friedman, J.M. The Human Disharmony Loop: A Case Series Proposing the Unique Role of the Pectoralis Minor in a Unifying Syndrome of Chronic Pain, Neuropathy, and Weakness. J Clin Med 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelein, B.; Cagnie, B.; Cools, A. Scapular muscle dysfunction associated with subacromial pain syndrome. J Hand Ther 2017, 30, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kibler, W.B.; McMullen, J. Scapular dyskinesis and its relation to shoulder pain. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2003, 11, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

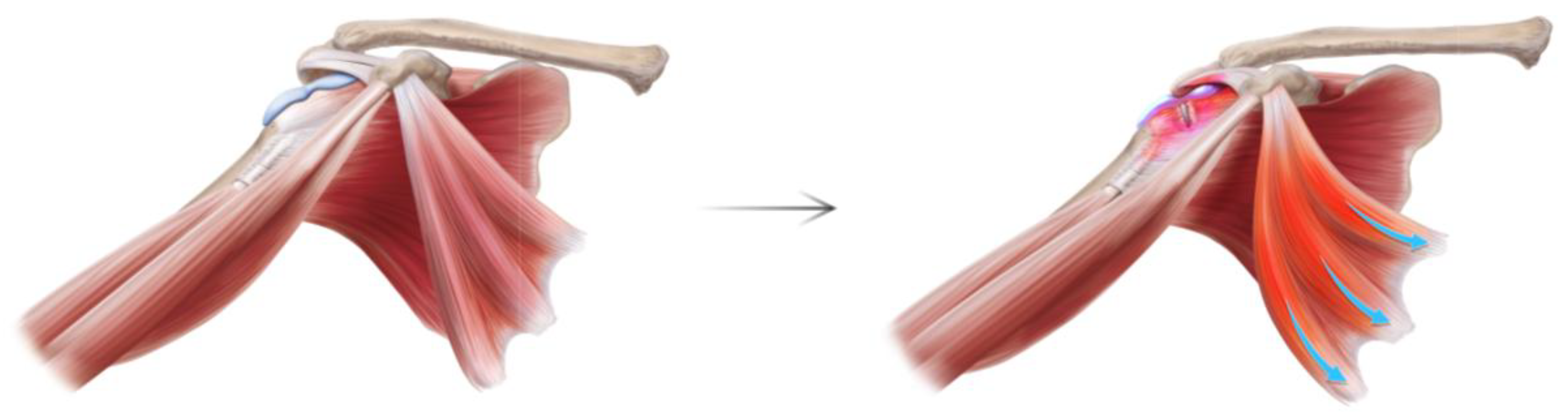

- Min, K.S.; Pham, B.; Scala, V. Arthroscopic pectoralis minor release in the beach chair position. JSES Rev Rep Tech 2022, 2, 174–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, J.A.; Munshi, M.-A.H.; Woodard, D.R.; DeFroda, S.F.; Nuelle, C.W.; Richard Ma, S.-Y. Arthroscopic Pectoralis Minor Release. Arthroscopy Techniques 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrix, S.T.; Hoyle, M.; Tokish, J.M. Arthroscopic Pectoralis Minor Release. Arthrosc Tech 2018, 7, e589–e594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provencher, M.T.; Kirby, H.; McDonald, L.S.; Golijanin, P.; Gross, D.; Campbell, K.J.; LeClere, L.; Sanchez, G.; Anthony, S.; Romeo, A.A. Surgical Release of the Pectoralis Minor Tendon for Scapular Dyskinesia and Shoulder Pain. Am J Sports Med 2017, 45, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Servasier, L.; Jeudy, J.; Raimbeau, G.; Bigorre, N. Arthroscopic release of the pectoralis minor tendon as an adjunct to acromioplasty in the treatment of subacromial syndrome associated with scapular dyskinesia. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2022, 108, 103211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struyf, F.; Nijs, J.; Baeyens, J.P.; Mottram, S.; Meeusen, R. Scapular positioning and movement in unimpaired shoulders, shoulder impingement syndrome, and glenohumeral instability. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2011, 21, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, J.S.; Wright, C.; Green, A. Subacromial impingement syndrome: the effect of changing posture on shoulder range of movement. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2005, 35, 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludewig, P.M.; Braman, J.P. Shoulder impingement: biomechanical considerations in rehabilitation. Man Ther 2011, 16, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmgren, T.; Hallgren, H.B.; Oberg, B.; Adolfsson, L.; Johansson, K. Effect of specific exercise strategy on need for surgery in patients with subacromial impingement syndrome: randomised controlled study. Br J Sports Med 2014, 48, 1456–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, S.; Meisel, C.; Tate, A. A cross-sectional study examining shoulder pain and disability in Division I female swimmers. J Sport Rehabil 2014, 23, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeser, J.C.; Joy, E.A.; Porucznik, C.A.; Berg, R.L.; Colliver, E.B.; Willick, S.E. Risk factors for volleyball-related shoulder pain and dysfunction. PM R 2010, 2, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, A.; Turner, G.N.; Knab, S.E.; Jorgensen, C.; Strittmatter, A.; Michener, L.A. Risk factors associated with shoulder pain and disability across the lifespan of competitive swimmers. J Athl Train 2012, 47, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelein, B.; Cagnie, B.; Parlevliet, T.; Cools, A. Scapulothoracic muscle activity during elevation exercises measured with surface and fine wire EMG: A comparative study between patients with subacromial impingement syndrome and healthy controls. Man Ther 2016, 23, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravichandran, H.; Janakiraman, B.; Gelaw, A.Y.; Fisseha, B.; Sundaram, S.; Sharma, H.R. Effect of scapular stabilization exercise program in patients with subacromial impingement syndrome: a systematic review. J Exerc Rehabil 2020, 16, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarsen, B.; Bahr, R.; Andersson, S.H.; Munk, R.; Myklebust, G. Reduced glenohumeral rotation, external rotation weakness and scapular dyskinesis are risk factors for shoulder injuries among elite male handball players: a prospective cohort study. Br J Sports Med 2014, 48, 1327–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, G.P.; Goodman, D.A.; Flatow, E.L.; Bigliani, L.U. The acromion: morphologic condition and age-related changes. A study of 420 scapulas. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1996, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, A.; Yildiz, V.; Kalali, F.; Yildirim, O.S.; Topal, M.; Dostbil, A. The role of acromion morphology in chronic subacromial impingement syndrome. Acta Orthop Belg 2011, 77, 733–736. [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, K.; Bergstrom, A.; Schroder, K.; Foldevi, M. Subacromial corticosteroid injection or acupuncture with home exercises when treating patients with subacromial impingement in primary care--a randomized clinical trial. Fam Pract 2011, 28, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.W.; Chen, Y.T.; Thompson, L.; Kjoenoe, A.; Juul-Kristensen, B.; Cavalheri, V.; McKenna, L. No relationship between the acromiohumeral distance and pain in adults with subacromial pain syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 20611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegedus, E.J.; Goode, A.P.; Cook, C.E.; Michener, L.; Myer, C.A.; Myer, D.M.; Wright, A.A. Which physical examination tests provide clinicians with the most value when examining the shoulder? Update of a systematic review with meta-analysis of individual tests. Br J Sports Med 2012, 46, 964–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | N = 140 |

|---|---|

| Age | 49 [37–60] |

| Sex | Male 58 (41%) Female 82 (59%) |

| BMI | 29 [25–33] |

| Workers Compensation | 35 (25%) |

| Surgical History | |

| Subacromial decompression | 38 (27%) |

| Rotator cuff repair | 29 (21%) |

| Biceps tenodesis | 23 (16%) |

| SLAP repair Labral repair Bankart repair |

5 (4%) 3 (2%) 2 (2%) |

| Distal clavicle resection | 10 (7%) |

| Clavicle ORIF | 1 (1%) |

| Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty | 14 (10%) |

| 1st rib resection + scalenectomy | 2 (1%) |

| Cervical spine fusion | 22 (16%) |

| Distal neurolysis (carpal, cubital) | 39 (28%) |

| MRI Findings Supraspinatus tendinopathy or tear Subscapularis tendinopathy or tear Bicipital tendonitis SLAP tear Labral tear |

(n = 52) 42 (81%) 2 (4%) 9 (17%) 8 (15%) 6 (12%) |

| Laterality | Right 80 (57%) Left 60 (43%) |

| Hand Dominance | Right 114 (81%) Left 26 (19%) |

| Medial Coracoid Injection | Provided Relief 99 (88%) |

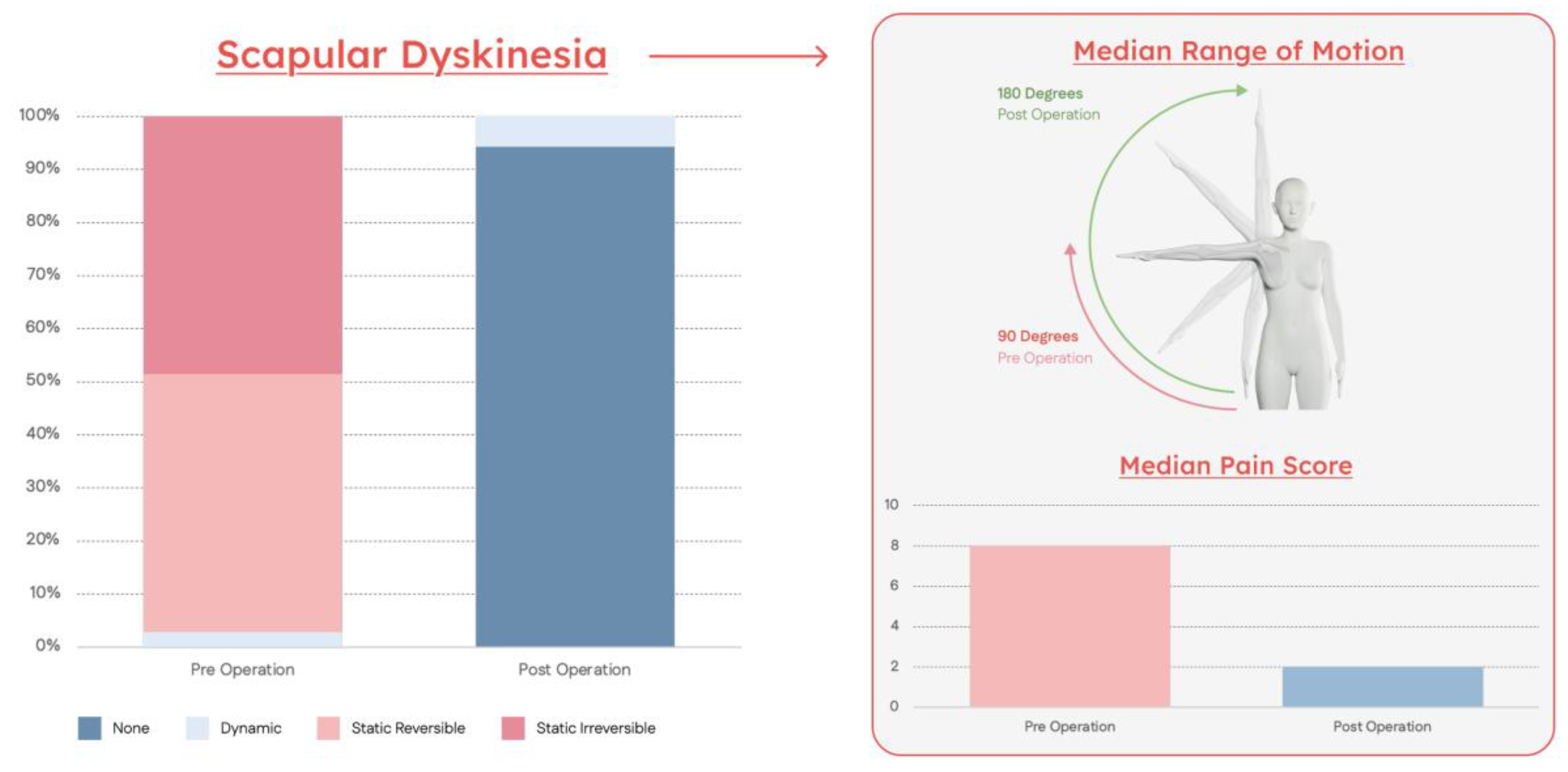

| Symptom | Preoperative | Postoperative | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain | 8 [6–9] | 2 [0–3] | <0.01 |

| Scapular Dyskinesia Stage | |||

| Stage I | 0 (0%) | 132 (94%) | |

| Stage II | 4 (3%) | 8 (6%) | <0.01 |

| Stage III | 68 (49%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Stage IV | 68 (49%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Shoulder Abduction ROM | 90 [90–100] | 180 [180] | <0.01 |

| Positive Impingement Signs | 140 (100%) | 15 (11%) | <0.01 |

| Neuropathic Lesions1 | |||

| Scalene muscles | 86 (61%) | 3 (2%) | |

| Suprascapular notch | 88 (63%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Quadrilateral space | 127 (91%) | 17 (12%) | <0.01 |

| Radial tunnel | 96 (69%) | 28 (20%) | |

| Cubital tunnel | 37 (26%) | 31 (22%) | |

| Carpal tunnel | 72 (51%) | 33 (24=%) | |

| Secondary Neurolysis2 | 27 (19%) | ||

| Suprascapular | 0 (0%) | ||

| Quadrilateral space | N/A | 9 (6%) | N/A |

| Radial | 13 (9%) | ||

| Cubital | 14 (10%) | ||

| Carpal | 9 (6%) |

| PMS | HDL | |

|---|---|---|

| Etiology | Unknown | Unique asymmetric lower trunk innervation |

| Mechanism | Compressive neuropathy | Deformation of scapula |

| Symptoms | Distal neuropathy only | All: headaches, neck pain, shoulder impingement, myofascial trigger points, and distal and proximal neuropathy |

| Anatomic Relationships to Other Chronic Pain Entities | Completely unknown | Clearly specifies cause and effect |

| Prognostic Value | Minimal | Strong |

| Epidemiology | Very rare | Ubiquitous |

| Relative Importance in Upper Limb Chronic Pain | After-thought | Central |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).