1. Introduction

Botulinum toxin, a potent neurotoxin produced by the bacterium

Clostridium botulinum, is known to paralyze skeletal muscle by inhibiting the release of acetylcholine [

1,

2]. Seven distinct botulinum toxin types have been identified [

3]. Botulinum toxin A (BoNT)-A) is regarded as a significant treatment modality in the field of facial rejuvenation [

4]. BoNT-A has been shown to exhibit therapeutic effects for a variety of conditions, including strabismus, hyperhidrosis, dystonia, spasticity, overactive bladder, and migraines, providing relief and improving patients’ quality of life [

5]. The mechanism of action involves inhibition of the release of acetylcholine at the neuromuscular junction, causing a loss in cholinergic signaling and resulting in temporary denervation and modulation of muscle activity. However, acetylcholine also acts on sympathetic nerves in glandular tissues, where it stimulates the sweat and salivary glands [

6].

BoNT exerts biological and non-muscular effects in human skin and other tissues. Epidermal keratinocytes, mesenchymal stem cells from subcutaneous adipose, nasal mucosal cells, urothelial cells, intestinal, prostate and alveolar epithelial cells, neutrophils, and macrophages express the BoNT-A-binding proteins SV2, FGFR3 or vanilloid receptors, and/or the BoNT-A cleavage target SNAP-25 and 23. BoNT-A can also induce specific biological effects in dermal fibroblasts, mast cells, sebocytes, and vascular endothelial cells [

7].

Botulinum toxin injection is today the most widely performed cosmetic procedure worldwide. The glabella region, which houses the procerus, orbicularis oculi, depressor supercilii, and corrugator muscles, is one of the most frequently treated areas for the reduction of muscle activity. The periorbital area is another common site targeted for correction [

8]. However, it can also produce undesirable effects attributable to the diffusion of the toxin to adjacent regions. The effect of BoNT-A can spread up to 3 cm transversely from the initial injection site.

Neurotoxin injection has been shown to improve dry eye symptoms in patients with blepharospasm [

9]. This raises the possibility that cosmetic BoNT-A injections may also impact the tear film and ocular surface.

Published research concerning tear film changes following cosmetic BoNT-A injection is scarce. The aim of this study was therefore to investigate the effect of BoNT-A injections on the tear film in patients receiving cosmetic treatment.

2. Material and Methods

This study was designed to evaluate ocular surface parameters across three distinct patient groups and an age- and gender-matched control group. Eighty participants were enrolled, 20 in each of the four groups. The study included individuals who had received upper face BoNT-A injections within the previous six months.

BoNT-A injections were administered using a standardized protocol. The procedure was performed under sterile conditions, using predetermined dosages and specific anatomical landmarks. Intramuscular injections of 0.1 mL Botox® (onabotulinumtoxin A, Allergan, Irvine, CA, USA) solution were delivered to each injection point, each participant receiving a total of 50 units. Injections targeted the orbicularis oculi, glabellar, frontalis, and procerus muscles. All applications were carried out by the same experienced cosmetic surgeon, thus ensuring reproducibility and standardization.

Patients in Group 1 were evaluated 0-1 month after BoNT-A injection, those in Group 2 were evaluated 1-3 months post-injection, and those in Group 3 were evaluated 3-6 months after injection. The control group consisted of individuals with no history of BoNT-A injection.

Individuals with a history of ocular surface disease, currently using topical medications, with previous histories of prior eyelid or facial surgeries and thyroid eye disease, and wearing contact lenses were excluded from the study. Ocular surface health was assessed using three basic parameters, the Schirmer test, Tear Break-Up Time (TBUT), and the Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI).

The study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Harran University, Türkiye, on March 18, 2024, under protocol number HRU/24.02.56. All participants provided written informed consent This research was conducted in full compliance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

The Schirmer test (without topical anesthesia) was conducted by placing a test strip behind the lower eyelid, between the temporal and middle third. This was removed after 5 minutes, and the length of the wet portion was measured.

TBUT was measured by applying a drop of 0.9% sterile saline as a wetting agent to a fluorescein strip, which was then used to dye the ocular surface. This allowed the examiner to use a cobalt blue filter to view the cornea and measure the break-up time, defined as the time between the patient's last complete blink and the formation of the first black spot or line, indicating a break in the tear film. The test was performed in duplicate, an average value being calculated. A reading of ≤ 10 seconds was considered abnormal.

The OSDI questionnaire consists of 12 questions, each rated on a five-point scale based on frequency: 0 for none, 1 for occasional, 2 for approximately half the time, 3 for most of the time, and 4 for continuous occurrence. The final OSDI score is calculated by summing the scores for the 12 questions, dividing this by the total number of questions answered, and then multiplying the result by 25. According to the Chinese Dry Eye Expert Consensus on Dry Eye Associated with Ocular Surgery, an OSDI score of 13 or greater indicates the presence of dry eye symptoms.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using R statistical software (version 4.1.2). The normality of the continuous variables was not explicitly tested in this analysis, but this is generally assumed for ANOVA. The variables were analyzed and expressed as mean ± standard deviation (though these specific descriptive statistics were not calculated in our analysis). A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses.

3. Results

This study involved 160 eyes of 80 patients (75% female, 25% male), with a mean age of 42 years (range: 34-58 years; women: 41 years, men: 43 years), constituting a comprehensive sample for the evaluation of ocular surface parameters in relation to BoNT-A injections.

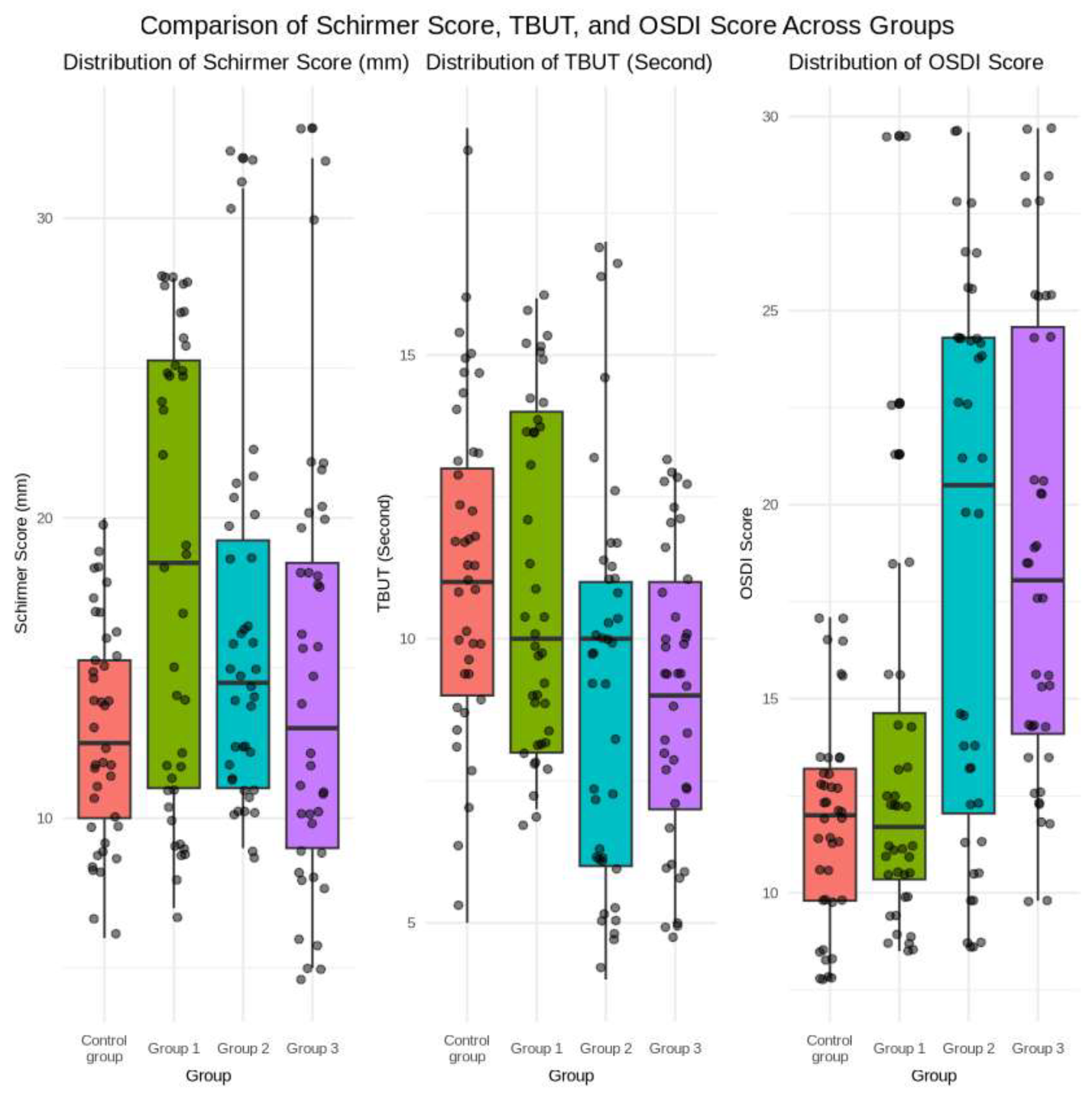

Schirmer test results revealed significant differences in tear production among the groups, with Group 1 (0-1 month post-injection) registering the highest mean score (18.35 ± 7.63 mm) and the control group the lowest (12.9 ± 3.64 mm). The difference between Group 1 and the control group was statistically significant (p < 0.01).

TBUT measurements indicated variations in tear film stability. The control group and Group 1 exhibited higher mean TBUT values (11.35 ± 2.92 and 11.05 ± 2.97 seconds, respectively) than groups 2 and 3. Significant differences were observed between groups 2 and 3 versus the control group (p < 0.05).

OSDI scores revealed differences in symptom severity across the study groups. Groups 2 and 3 exhibited statistically significantly higher mean OSDI scores (18.62 ± 7.04 and 18.82 ± 6.08, respectively) compared to the control group (11.82 ± 2.67, p < 0.001).The demographic characteristics and ocular surface parameters for all groups are summarized in

Table 1, with comparative analyses shown in

Figure 1.

4. Discussion

Our study findings suggest that BoNT-A injections may result in a transient impact on tear film parameters, the most significant changes occurring shortly after the injection. Comprehensive evaluations of tear film characteristics in healthy individuals receiving periorbital injections for cosmetic purpose are lacking in the existing literature. This study addresses this gap by demonstrating that cosmetic BoNT-A injections can alter tear film characteristics. Specifically, the observed decrease in tear production, as indicated by lower Schirmer test scores, and diminished tear film stability, evidenced by shorter tear breakup times within the first three months post-injection, indicate that these alterations may contribute to the development of dry eye symptoms in these patients.

These findings suggest that BoNT-A injections can lead to temporary reductions in tear production and impaired tear film stability. The underlying mechanism may be related to the effects of BoNT-A on the orbicularis oculi muscle, which plays a crucial role in the blink reflex and tear production [

10,

11]. Weakening of the orbicularis oculi can result in a decreased blinking frequency and reduced tear secretion, ultimately leading to an unstable tear film and the development of dry eye symptoms [

12].

Previous research has investigated the impact of botulinum toxin on tear drainage and ocular surface parameters. For instance, Sahlin et al. found that limited dose injection produces better results with fewer complications, such as eyelid retraction, in patients with dry eye disease [

13]. Similarly, Choi et al. reported an increase in tear meniscus height and improvement in OSDI scores one month after BoNT-A injection in patients with dry eye disease [

14]. In contrast, Bayraktar Bilen et al. observed no significant changes in tear film stability or production in patients with blepharospasm and hemifacial spasm [

15]. Yao et al. demonstrated a significant decrease in tear production after BoNT-A injections to the upper face and lateral canthal region, with no marked increase in dry eye symptoms [

16]. Additionally, Ekin et al. highlighted the therapeutic potential of lacrimal gland botulinum toxin injections in the treatment of epiphora [

17]. These findings are consistent with those of the present study's investigation of botulinum toxin in modulating tear film dynamics and addressing related symptom management. While the current study initially shows an increase in Schirmer test results, the subsequent decrease in TBUT and increase in OSDI scores suggest that chemodenervation of the orbicularis oculi muscle may initially increase tears, followed by a more pronounced, time-dependent effect on the lacrimal gland.

The results of this study demonstrate the multifaceted impact of BoNT-A injection on tear production, tear film stability, and ocular surface symptoms. In particular, the decreases in Schirmer values, shorter tear breakup time durations, and higher OSDI scores observed in the 1-3 month and 3-6 month post-injection groups indicate the time-dependent effects of botulinum toxin on tear dynamics. The effects of BoNT-A on tear film dynamics may not fully manifest within the first month after injection. The modulation of cholinergic signaling and the blockade of parasympathetic innervation of the lacrimal gland can lead to gradual changes in tear production and stability [

18]. More pronounced effects therefore typically emerge after the first month. It is crucially important for clinicians to be aware of these temporal variations when evaluating and counseling patients undergoing cosmetic periorbital botulinum toxin injections.

Although the Schirmer test results in groups 2 and 3 were lower than those in Group 1, they were not significantly different from those in the control group. This suggests that the impact of BoNT-A injections on tear production, as measured by the Schirmer test, may be more transient and less pronounced in the long term than initially hypothesized. The lack of significant differences between the treatment groups and the control group indicates that the decrease in tear production observed shortly after the injections may be a temporary effect, and that the ocular surface may be able to gradually adapt and compensate.

The significant differences in TBUT measurements between groups 2 and 3 and the control group suggest that BoNT-A injections may lead to a sustained reduction in tear film stability. This may be due to prolonged alterations in ocular surface physiology or tear composition that extend beyond the initial post-injection period. The weakening of the orbicularis oculi muscle caused by BoNT-A injection may result in decreased blink frequency and tear secretion, ultimately leading to an unstable tear film and to the development of dry eye symptoms over an extended period.

However, the persistent elevation in OSDI scores in groups 2 and 3 suggests that dry eye symptoms may persist even while tear film parameters improve. This highlights the complexity of ocular surface homeostasis and the potential for persisting symptoms despite objective improvements in tear production and stability. Nevertheless, the impact of BoNT-A injections on the ocular surface appears to be transient, as evidenced by the gradual return to baseline levels in the groups evaluated at later time points [

19,

20]. This suggests that the ocular surface may have the capacity to adapt and compensate for the initial changes, potentially through the activation of compensatory mechanisms, such as increased tear production by the accessory lacrimal glands.

It is essential to consider these potential side effects when administering BoNT-A, especially in patients with pre-existing dry eye conditions or those at risk of developing dry eye. Careful patient selection, dosage adjustment, and close monitoring during the post-injection period are crucially important to minimizing the impact on tear film parameters and mitigating the risk of dry eye complications.

5. Limitations

The limitations of this cross-sectional study evaluating different groups at various time points post-injection include the absence of long-term follow-up data beyond six months. The study design restricted our ability to track changes in individual patients over time, which would have yielded more comprehensive data on the temporal effects of botulinum toxin injections.

6. Conclusions

This study shows that cosmetic periorbital BoNT-A injections can result in transient alterations in tear film parameters, leading to decreased tear production and tear film instability, as well as increased ocular surface disease symptoms. These changes may develop gradually, highlighting the importance of close monitoring and patient education regarding the potential ocular side-effects associated with such injections. Further prospective, longitudinal studies with larger sample sizes and extended follow-up periods are now needed to confirm these findings and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between cosmetic periorbital botulinum toxin injections and ocular surface dynamics.

References

- Thakker MM, Rubin PA. Pharmacology and clinical applications of botulinum toxins A and B. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2004;44(3):147–163. [CrossRef]

- Aoki KR. Pharmacology and immunology of botulinum neurotoxins. Int Ophthalmol Clin 2005;45(3):25–37. [CrossRef]

- Schantz EJ, Johnson EA. Properties and use of botulinum toxin and other microbial neurotoxins in medicine. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56(1):80–99. [CrossRef]

- Rohrich RJ, Janis JE, Fagien S, Stuzin JM. The cosmetic use of botulinum toxin. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112(5):177S–188S. [CrossRef]

- Gart MS, Gutowski KA. Overview of botulinum toxins for aesthetic uses. Clin Plast Surg. 2016;43(3):459–471. [CrossRef]

- Felder CC. Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors: signal transduction through multiple effectors. The FASEB Journal. 1995;9(8): 619-625. [CrossRef]

- Grando SA, Zachary CB. The non-neuronal and nonmuscular effects of botulinum toxin: an opportunity for a deadly molecule to treat disease in the skin and beyond. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(5):1011–1019. [CrossRef]

- Troell RJ. Peri-orbital aesthetic rejuvenation surgical protocol and clinical outcomes. Am J Cosmet Surg. 2017;34(2):81–91. [CrossRef]

- Scott AB, Kennedy RA, Stubbs HA. Botulinum A toxin injection as a treatment for blepharospasm. Arch Ophthalmol. 1985;103(3):347–350. [CrossRef]

- Ziahosseini K, Al-Abbadi Z, Malhotra R. Botulinum toxin injection for the treatment of epiphora in lacrimal outflow obstruction. Eye. 2015;29(5):656–661. [CrossRef]

- Ahn C, Kang S, Sa HS. Repeated injections of botulinum toxin-A for epiphora in lacrimal drainage disorders: qualitative and quantitative assessment. Eye. 2019;33(6):995–999. [CrossRef]

- Ho RW, Fang PC, Chao TL, Chien CC, Kuo MT. Increase lipid tear thickness after botulinum neurotoxin A injection in patients with blepharospasm and hemifacial spasm. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):8367. [CrossRef]

- Sahlin S, Chen E, Kaugesaar T, Almqvist H, Kjellberg K, Lennerstrand, G. Effect of eyelid botulinum toxin injection on lacrimal drainage. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;129(4):481–486. [CrossRef]

- Choi EW, Yeom DJ, Jang SY. Botulinum toxin a injection for the treatment of intractable dry eye disease. Medicina. 2021;57(3):247. [CrossRef]

- Bayraktar Bilen N, Bilen Ş, Topçu Yılmaz P, Evren Kemer Ö. Tear meniscus, corneal topographic and aberrometric changes after botulinum toxin-a injection in patients with blepharospasm and hemifacial spasm. Int Ophthalmol. 2022;42(8):2625–2632.

- Yao A, Malhotra R. Do botulinum toxin injections for upper face rejuvenation and lateral canthal rhytids have unintended effects on tear production? Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2024;10:1097.

- Altin Ekin M. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of lacrimal gland botulinum toxin injection in functional versus non-functional epiphora. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2024;1–9.

- Wojno TH. Results of lacrimal gland botulinum toxin injection for epiphora in lacrimal obstruction and gustatory tearing. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;27:119–121. [CrossRef]

- Naumann M, Albanese A, Heinen F, Molenaers G, Relja M. Safety and efficacy of botulinum toxin type A following long-term use. Eur J Neurol. 2006;13:35–40. [CrossRef]

- Lee JH, Kim DY, Kim KS. Botulinum toxin for palliative treatment of epiphora in patients with nasolacrimal duct obstruction. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2007;48(10):1318–1322. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).