1. Introduction

Contact lenses (CL) offer a convenient and attractive alternative to traditional eyeglasses for the optical correction of refractive error, providing a heightened level of satisfaction and enhancing the overall quality of life [

1,

2]. Despite the progress made in CL comfort and safety, CL discomfort (CLD) is estimated to affect up to 50% of CL wearers [

3]. Moreover, up to 30% of CL wearers permanently discontinue CL wear because of CLD [

3,

4]. CLD is a complex issue [

5] that has been defined by the Tear Film and Ocular Surface (TFOS) International Workshop as “a condition characterized by episodic or persistent adverse ocular sensations related to CL wear, either with or without visual disturbance, resulting from reduced compatibility between the CL and the ocular environment, which can lead to decreased wearing time and discontinuation of CL wear” [

6]. It is important to identify symptomatic CL wearers and implement strategies to prevent CL dropout, which has the potential to negatively affect their quality of life [

1,

2,

7].

CLD is typically diagnosed based on the patient’s reported symptoms rather than through observation of physical signs. Therefore, questionnaires that assess the parameters of discomfort specific to this condition are useful tools in the diagnostic process. Of the available questionnaires, the Contact Lens Dry Eye Questionnaire-8 (CLDEQ-8) is traditionally used as the questionnaire of choice to identify symptomatic CL users [

5,

8]. One of the most common approaches to prevent or at least reduce CLD is to increase the frequency of CL replacements [

9,

10,

11]. The reduced presence of deposits on the CL surface and improved wettability, coupled with the lack of the need to use care systems (which can also contribute to CLD), make CL replacement with a daily disposable contact lens (DDCL) one of the most effective solutions for reducing CLD symptoms or complications [

4,

9,

11]. Nevertheless, it is essential to consider the possibility of a placebo effect when conducting such studies [

10]. Therefore, it is crucial to demonstrate the efficacy of the treatment, considering the potential influence of the placebo effect.

Quality of life is an essential aspect of refractive care. A significant objective of CL fitting is to attain optimal vision and comfort, which ultimately results in patient satisfaction and an improved quality of life [

7]. The World Health Organization defines quality of life as “an individual’s perception of his or her position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which he or she lives and in relation to his or her goals, expectations, standards and concerns” [

12]. The 25-item version of the National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire (NEI VFQ-25) is a validated questionnaire [

13] that has been used to assess the quality of life in several eye conditions [

14,

15,

16,

17].

This study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of refitting symptomatic CL wearers with a new DDCL (kalifilcon A) in improving comfort and enhancing vision-related quality of life.

2. Materials and Methods

This was a single-center, single-blinded, prospective, randomized crossover study, allowing each subject to serve as their own control. This study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee (CEIC) of the University of Murcia and complied with the Tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.1. Participants

The Spanish version of the CLDEQ-8 questionnaire [

18] was distributed to monthly CL wearers who had a minimum of six months of CL wear experience, and those who were symptomatic (CLDEQ-8 ≥ 12) were invited to participate in the study. The inclusion criteria were age between 18 and 40 years, spherical equivalent refraction between -1.00 and -6.00 D, astigmatism ≤ -0.75 D, and best-corrected visual acuity of 20/20 or better. The exclusion criteria were CL wear other than monthly replacement (including overnight use), dry eye disease according to the TFOS DEWS II diagnostic criteria [

19], and active ocular allergies, ocular diseases, history of previous eye surgery, topical medication, or systemic diseases contraindicating CL wear. Additionally, asymptomatic CL wearers were excluded according to the CLDEQ-8 (score < 12 points) questionnaire.

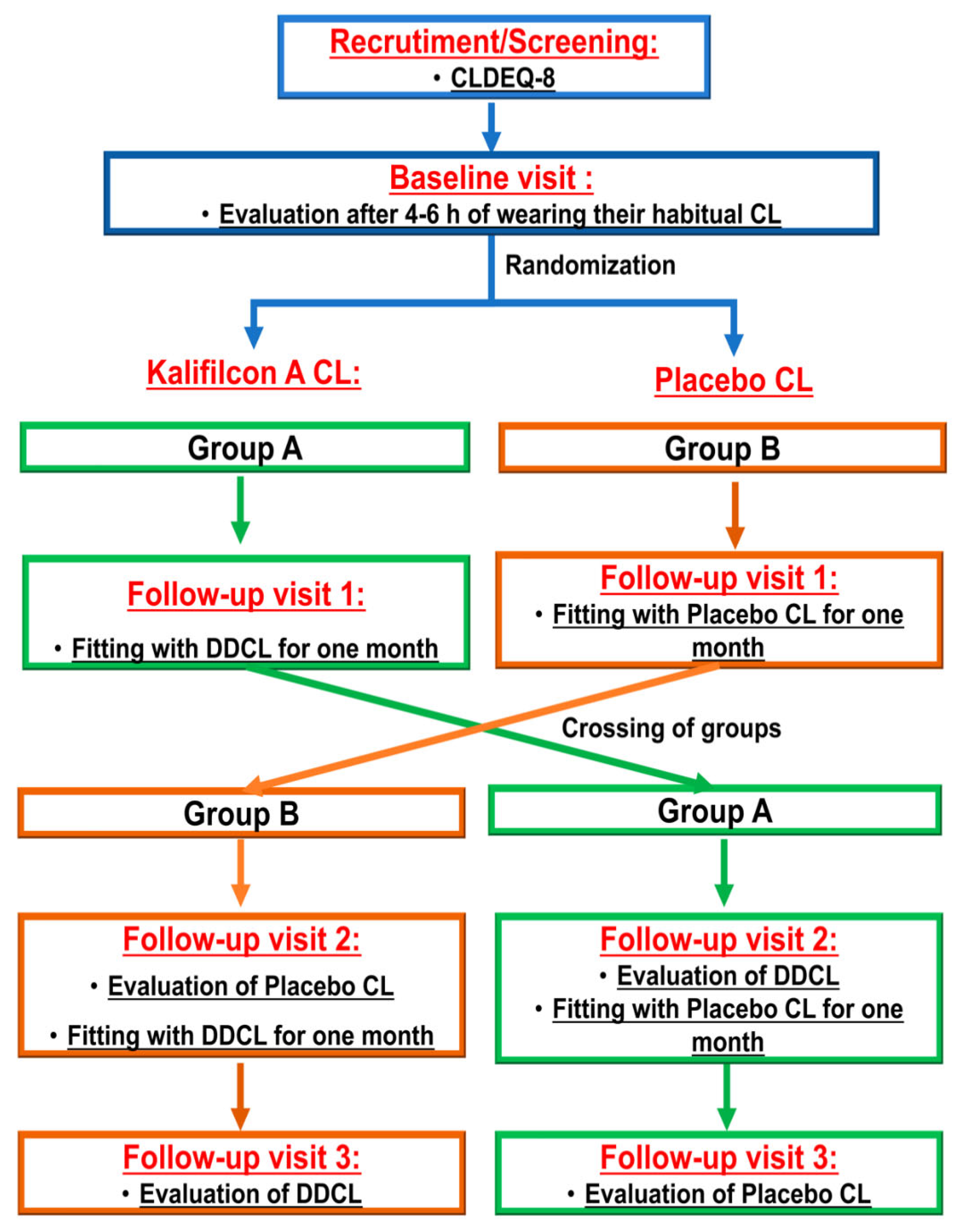

Participants were randomized into two groups. One group was refitted with Kalifilcon A lenses (Kalifilcon A One day

®; Bausch&Lomb), while the other was refitted with a masked pair of their habitual CL (

Figure 1).

2.2. Procedure

All optometric measurements were conducted by the same optometrist in the same order to minimize potential variability resulting from examiner subjectivity.

Following recruitment, all the selected participants attended four visits.

Baseline visit: Participants were asked to attend the visit–4-6 h after wearing their habitual CL. At this visit, their habitual CL was assessed, and participants provided information about their experience of use and completed the CLDEQ-8 [

5,

8,

18], the NEI VFQ-25 [

13] questionnaires to assess symptomatology and vision-related quality of life during CL wear, and a series of questions regarding their subjective satisfaction with the contact lenses used [

1]. Visual acuity (VA) and auto tear break-up time were evaluated using the Medmont E 300, version 6.1 (Medmont, medmont.com.au). This device provides three values for each measurement: tear film surface quality (TFSQ), TFSQ area (A-TFSQ), and auto-tear break-up time (TBUT). TFSQ is a previously validated algorithm [

20]. Finally, participants removed their CL to perform the necessary tests for the fitting study. These tests included corneal topography using the Medmont E300 and eye health evaluation using the Efron grading scale. At the end of this visit, CL were ordered to the manufacturers.

Visit 1: Half of the participants were randomly selected and administered DDCL for one month (kalifilcon A, ULTRA One Day, Bausch and Lomb). The other half of the participants were provided with a new pair of their usual monthly CLs masked in a CL case and were informed that they were from a new manufacturer. CL fitting, TFSQ, A-TFSQ, TBUT, and VA were assessed after 25 min of wear, and the participants were instructed to wear the new pair of contact lenses according to their usual routine and were provided with standardized guidelines for proper handling and cleaning, to be followed until their next visit

Visit 2: Participants were cited one month after visit 1 to assess CL fitting. During this visit, participants answered the CLDEQ-8, the NEI VFQ-25, and their subjective satisfaction with the CL questionnaires. For clinical evaluation, the same protocol as that described in the first visit was applied.

During this visit, the groups were crossed, with participants who had used DDCL given their usual monthly CL masked, and vice versa. Once more, CL fitting and all clinical evaluation tests were assessed after 25 min of wear, and participants were requested to continue using the CLs provided to them.

Visit 3: One month following the second visit, participants were cited to assess CL fitting. The same protocol as that described for the first visit was used. The participants completed the study upon finishing the evaluation of this visit. By the study’s conclusion, all participants had worn two different CLs for one month each. Finally, the participants were requested to indicate which of the two CLs they preferred in terms of comfort and vision.

2.3. Questionnaires

The NEI-VQF-25 is a validated and comprehensive questionnaire designed to assess the impact of vision impairment on an individual’s quality of life [

13]. It includes 25 items divided into several subscales, each targeting different aspects of vision-related quality of life: general health, general vision, ocular pain, near activities, distance activities, social functioning, mental health, role difficulties, dependency, driving, color vision, and peripheral vision. Each item on the VQF-25 is rated on a scale, with higher scores indicating greater difficulties and a more significant impact on quality of life.

The Contact Lens Dry Eye Questionnaire-8 (CLDEQ-8) is a concise questionnaire that has been validated to measure the frequency and severity of dry eye symptoms in contact lens wearers [

8]. This questionnaire, consisting of eight items, focuses on common symptoms, such as dryness, discomfort, and visual disturbances, which are often intensified by the use of contact lenses. Each item on the CLDEQ-8 was rated based on frequency and severity, with higher scores indicating more significant symptoms and a greater impact on the individual’s comfort and satisfaction with contact lens wear.

The questionnaire regarding their subjective satisfaction with the CL consisted of seven questions rated on a 0–10 scale (higher scores indicating greater satisfaction with the CL) related to handing for application, handling for removal, comfort, vision clarity, overall satisfaction with comfort, overall satisfaction with vision clarity, and overall satisfaction with these lenses to evaluate the participants’ subjective satisfaction with the CL [

1].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences software version 28 (SPSS, International Business Machine Corp. IBM, Chicago, IL, USA). Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). An independent samples t-test was used to compare the mean differences between the two groups. Univariate analyses (chi-squared test) were performed to describe the relationship between the CLDEQ-8 test and CL type. The significance level was set at P < 0.05.

3. Results

A total of 79 symptomatic monthly replacement CL wearers (CLDEQ-8 ≥ 12) were recruited for this study. The mean age ± SD of the participants was 27.07 ± 8.38 (range 19–40). Of the 79 participants, 77% were female and 23% male. The demographic and baseline information are summarized in

Table 1.

3.1. Kalifilcon A CL Refitting

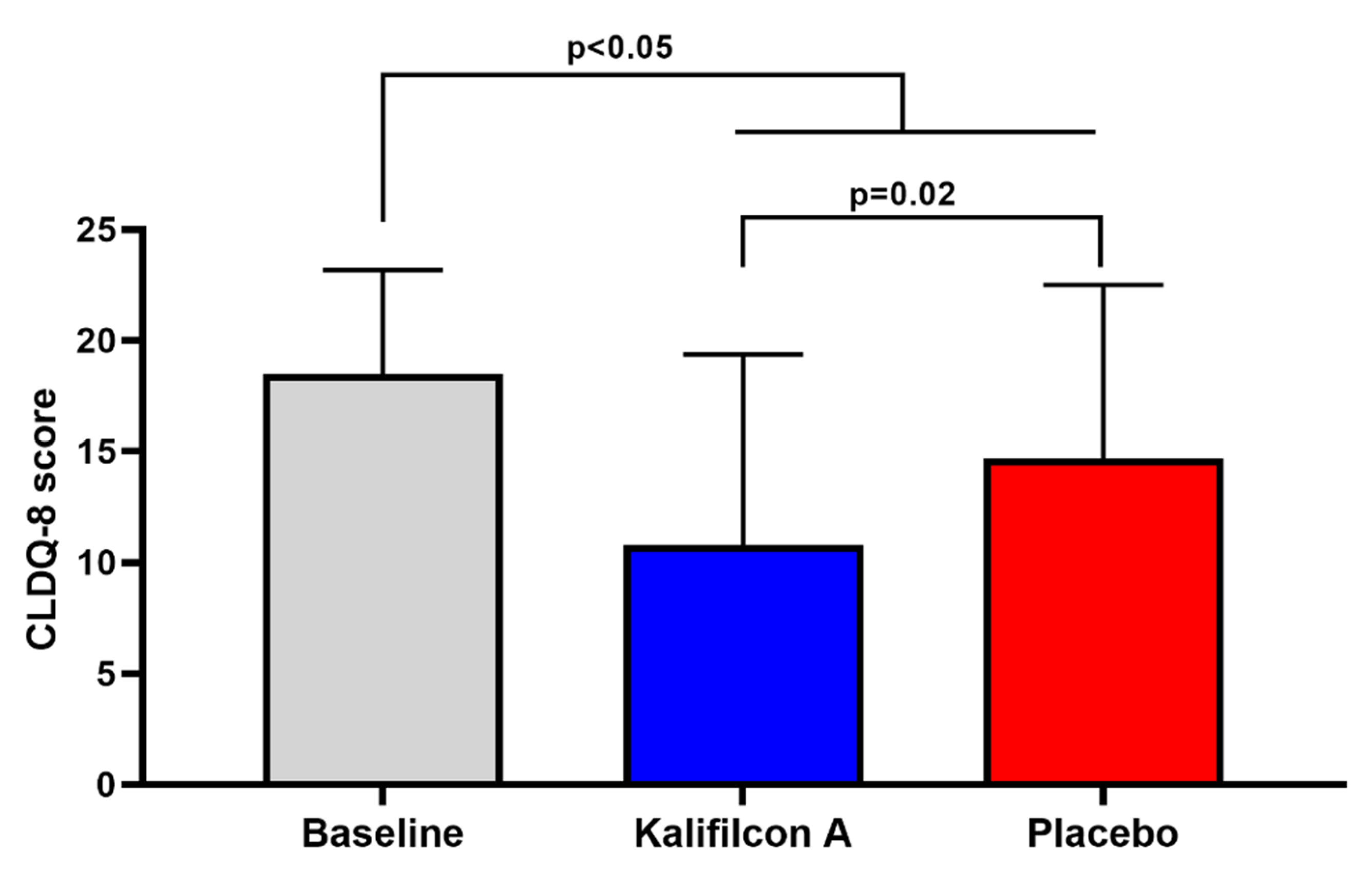

After one month of wearing Kalifilcon A DDCL, the mean CLDEQ-8 score showed a statistically and clinically significant reduction compared to baseline (10.8 ±8.5 and 18.5±4.6; p< 0.005;

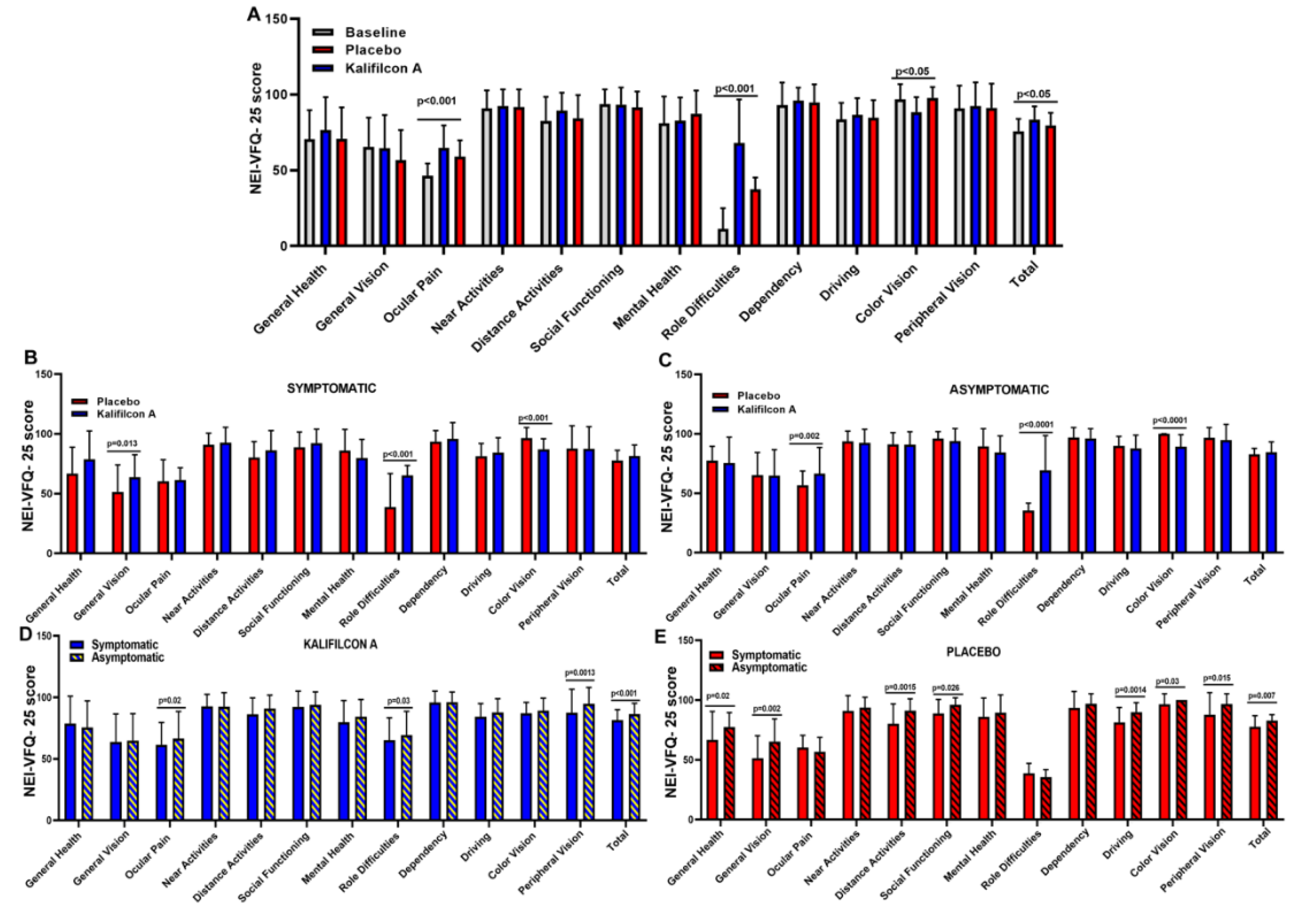

Figure 2). This reduction in symptomatology was also reflected in a statistically significant improvement in vision-related quality of life as measured using the NEI VFQ-25 questionnaire. The overall score was 75.83±8.0 at baseline and 83.5±8.6 with the Kalifilcon A DDCL p< 0.005;

Figure 3). More specifically participant refitted with Kalifilcon A DDCL indicated better feedback on ocular pain (p<0.001), role difficulties (p<0.001), and color vision (p<0.05).

A comparison of CLDEQ-8 results at baseline and one month following Kalifilcon A CL wear revealed that while 100% were symptomatic at the beginning of the study, only 33% remained symptomatic after one month, while 67% were classified as asymptomatic.

To assess whether there is a direct relationship between vision-related quality of life and symptoms during CL wear, NEI VFQ-25 scores were compared between symptomatic and asymptomatic participants after refitting with Kalifilcon A DDCL. The overall score showed a significantly higher vision-related quality of life (p<0.01) in the asymptomatic (86.5±8.6) compared to symptomatic (81.5±8.6) participants (

Figure 3 D, E). More specifically, asymptomatic participants showed a significant improvement when refitted with Kalifilcon A DDCL lenses in the ocular pain (p=0.02), role difficulties (p=0.03), and peripheral vision (p=0.0013) of the NEI VFQ-25 subscales.

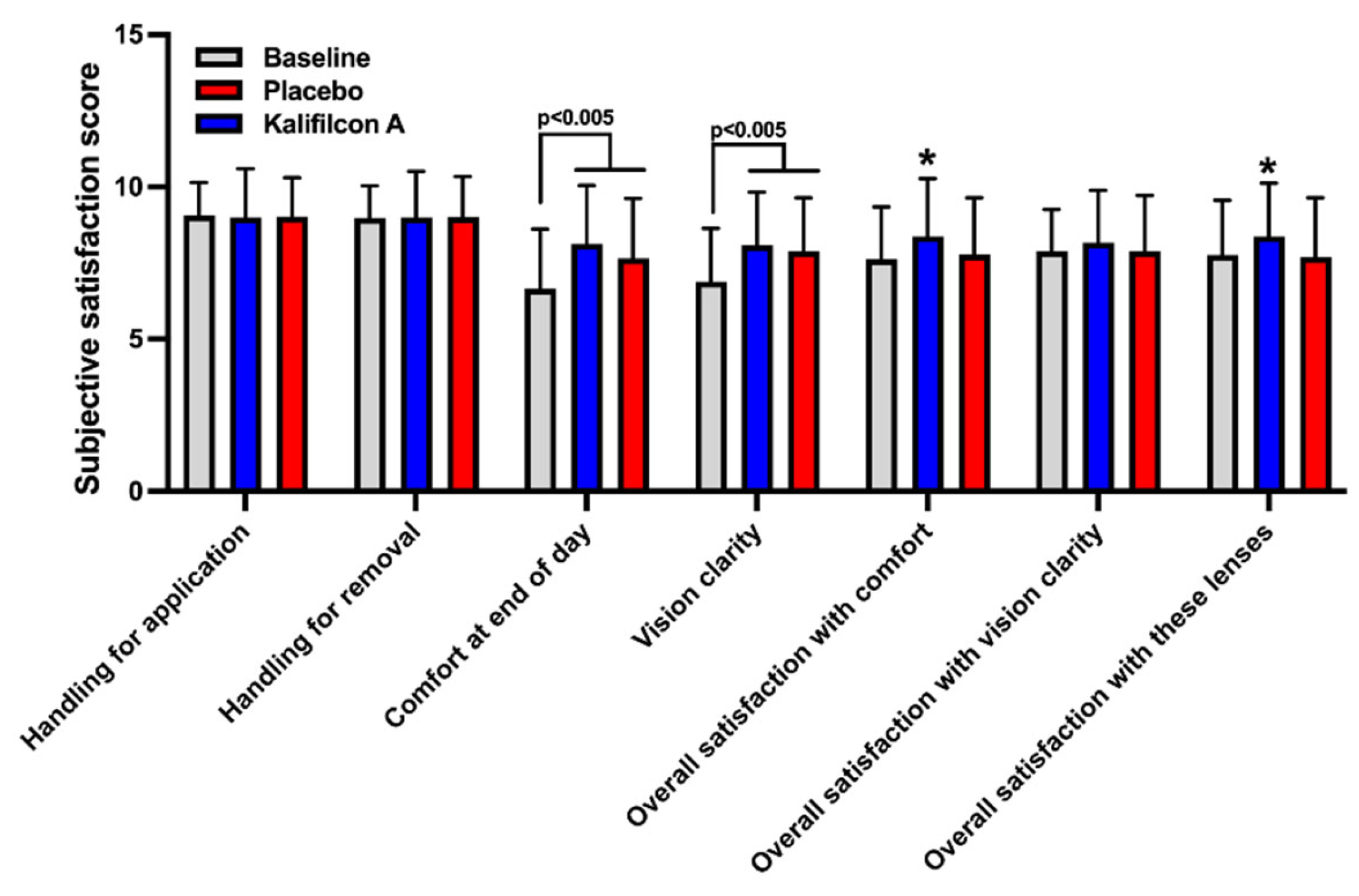

Participants rated their experience with Kalifilcon A DDCL using a 10-item standardized questionnaire [

1]. The results demonstrated a clear and significant improvement in overall comfort assessment (p < 0.0001), visual acuity (p < 0.0001), overall satisfaction with the lens (p = 0.005), and general satisfaction with the lens (p = 0.0004) among patients refitted with Kalifilcon A DDCL compared to the previous/baseline results (

Figure 4).

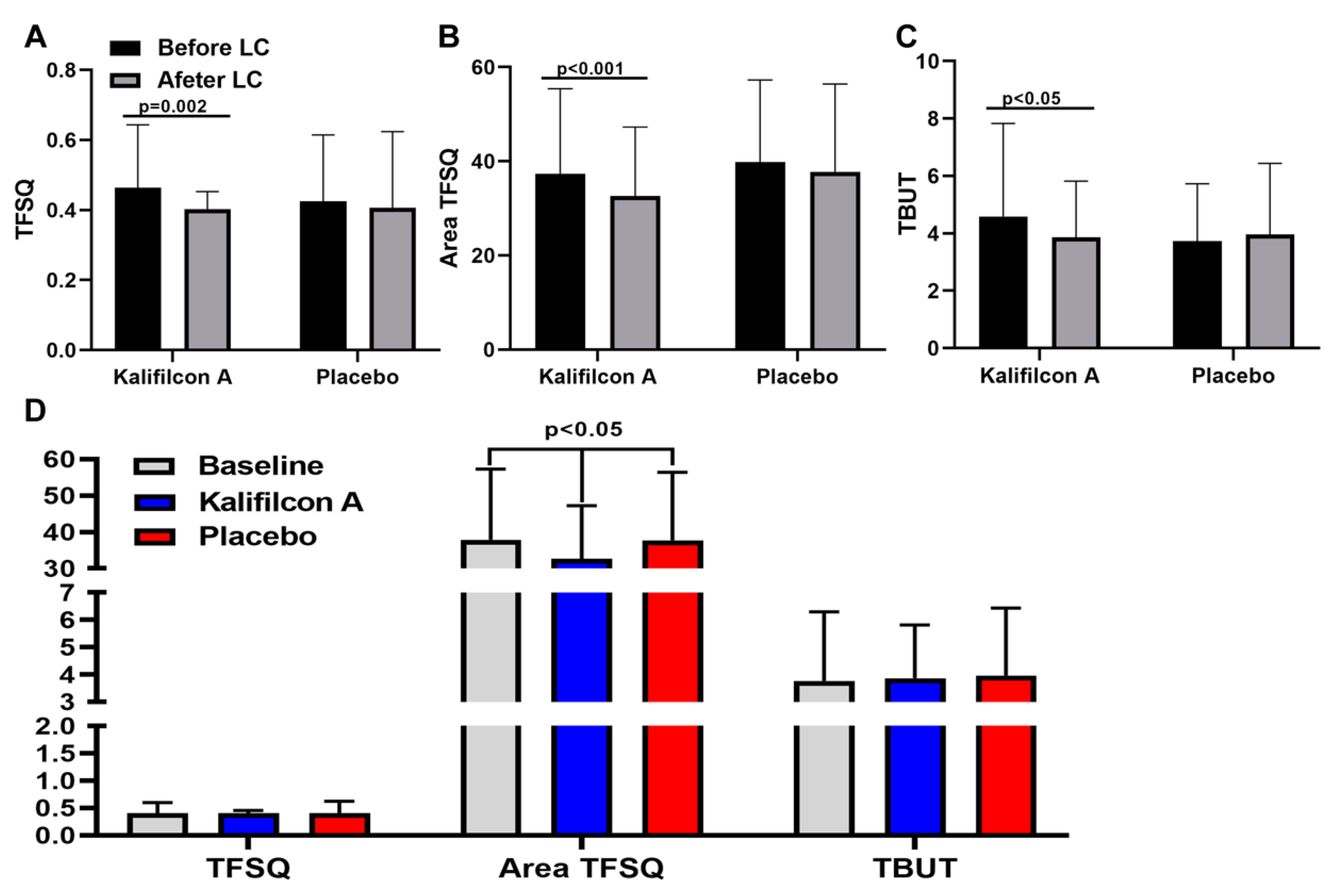

The clinical evaluation of the auto tear break-up time showed a significant reduction of TFSQ (p=0.002), A-TFSQ (p<0.001) and TBUT(p<0.05) after one month refitted with Kalifilcon A DDCL (

Figure 5)

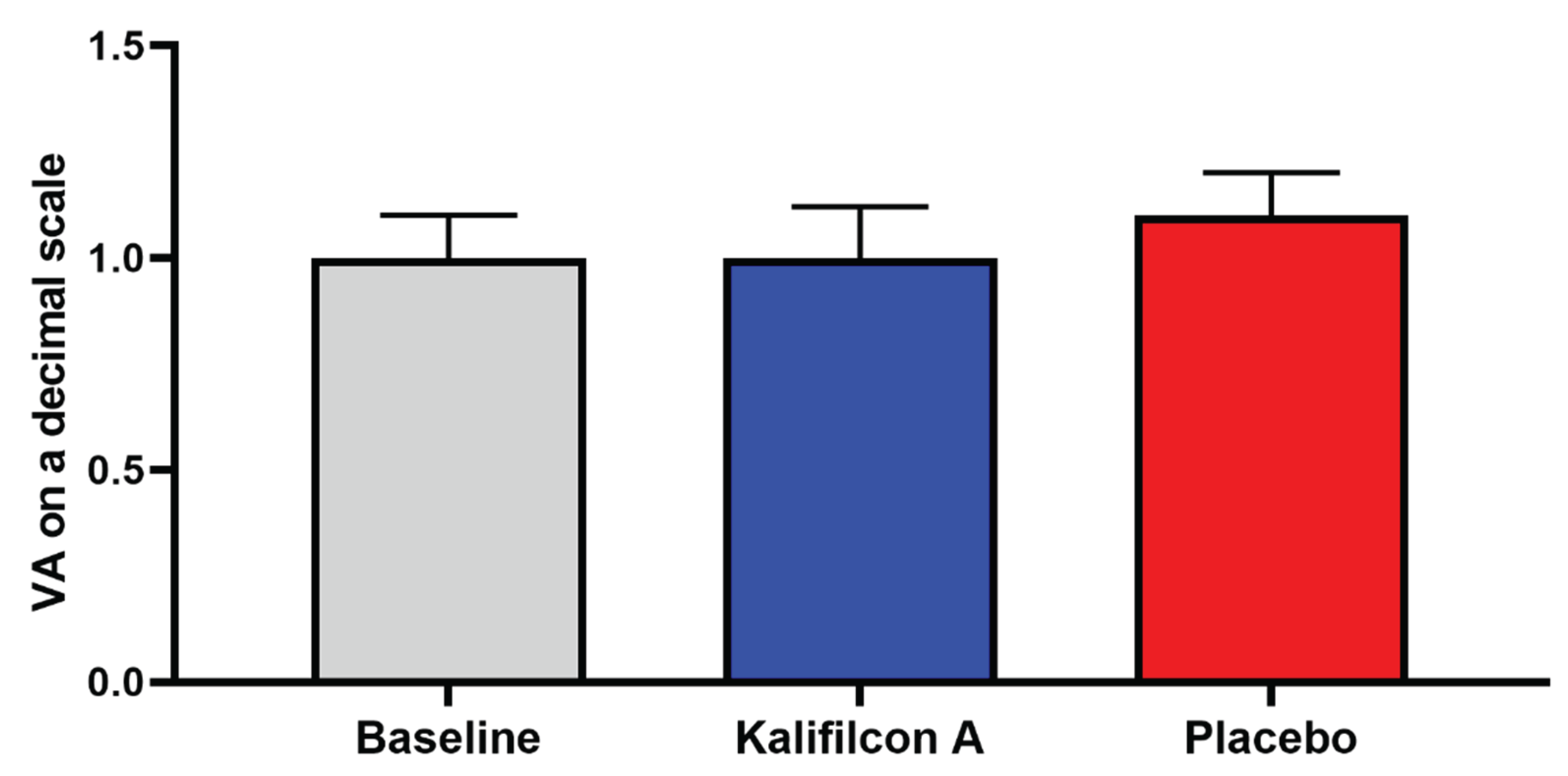

Furthermore, no discernible alterations in visual acuity (re 6) or ocular health (Efron grading scale) were observed following either CL wear compared to those observed at the baseline visit.

3.2. Placebo CL Refitting

After one month of wearing the Placebo CL, the mean total score on the CLDEQ-8 questionnaire showed a statistically significant reduction from the baseline (15.0 ± 7.5 compared to 18.5 ± 4.6; p < 0.05;

Figure 2). Considering that 100% of the participants were symptomatic at the beginning of the study, after one month of using the placebo lens, 40% became non-symptomatic, indicating a placebo effect.

The placebo effect on symptomatology was also reflected in a significant improvement in vision-related quality of life as measured by the NEI VFQ-25 questionnaire. The overall score was 75.83±8.0 at baseline and 79.6±8.1 with the Placebo CL p=0.003;

Figure 3). Similarly, to the results obtained whit the Kalifilcon A DDCL, when the participants were refitted with Placebo CL indicated better feedback in ocular pain (p<0.001), role difficulties (p<0.001), and color vision (p<0.05).

Moreover, in placebo CL, there is a direct relationship between vision-related quality of life and symptoms during CL wear. The overall score of the NEI VFQ-25 scores was compared between symptomatic and asymptomatic participants after refitting with Placebo CL, showing a significantly higher vision-related quality of life (p=0.007) in the asymptomatic (82.7±4.9) compared to symptomatic (77.8 ±9.1) participants (

Figure 3). More specifically, asymptomatic participants observed a significant improvement when refitted with Placebo CL lenses in general health (p=0.02), general vision (p=0.002), distance activities (p=0.0015), social functioning (p=0.026), driving (p=0.0014), color vision (p=0.03), and peripheral vision (p=0.015) of the NEI VFQ-25 subscales.

In the subjective rate of their experience with the Placebo CL, the participants indicated only a significant improvement in the overall comfort assessment (p < 0.005) and visual acuity (p < 0.005), compared to the previous/baseline results (

Figure 4).

In contrast with the results obtained with Kalifilcon A DDCL, the clinical evaluation of the auto tear break-up time after one month refitted with Placebo CL showed no differences in TFSQ (p= 0.56), A-TFSQ (p=0,38) and TBUT(p<0.55) compared to baseline values (

Figure 5).

Furthermore, no discernible alterations in visual acuity (

Figure 6) or ocular health (Efron grading scale) were observed following either CL wear compared to those observed at the baseline visit.

3.3. Kalifilcon A Versus Placebo CL Refitting

The mean total score obtained with the CLDEQ-8 questionnaire demonstrated a statistically and clinically significant reduction when the participants were refitted with Kalifilcon A DDCL in comparison to Placebo LC (10.8 ±8.5 and 15.0±7.5; p=0.02;

Figure 2). This reduction in symptomatology was also reflected in a statistically significant improvement in vision-related quality of life as measured using the NEI VFQ-25 questionnaire. The overall score was 79.67±8.1 with Placebo CL and 83.5±8.6 with the Kalifilcon A DDCL p=0.004;

Figure 3). More specifically participant refitted with Kalifilcon A DDCL indicated better feedback on ocular pain (p<0.001), role difficulties (p<0.001), and color vision (p<0.05).

To assess whether there was a direct relationship between vision-related quality of life and symptoms depending on what CL the participant wears, symptomatic and asymptomatic participants’ NEI VFQ-25 scores were compared after refitting with Kalifilcon A DDCL or Placebo CL. The overall score showed no statistical difference in vision-related quality of life between symptomatic (p=0.32) and asymptomatic (p=0.09) participants (

Figure 3). However, in the NEI VFQ-25 subscales, symptomatic participants indicated a significant improvement in general vision (p=0.013) and role difficulties (p<0.001) when they were refitted with Kalifilcon A DDCL. Furthermore, the asymptomatic participants indicated a significant improvement in ocular pain (p=0.002) and role difficulties (p<0.0001) when they were refitted with Kalifilcon A DDCL. However, both symptomatic (p<0.001) and asymptomatic (p<0.0001) participants indicated a significant improvement in color vision subscales when they were refitted with Placebo CL.

The results of the evaluation of the subjectively rate experience of wear the CL demonstrated a clear and significant improvement in general satisfaction with comfort (p = 0.003) and overall satisfaction with the lens (p = 0.0002) among patients refitted with Kalifilcon A DDCL compared to Placebo CL (

Figure 4)

The clinical evaluation of the auto tear break-up time showed only a significant reduction of A-TFSQ (p<0.05) after one month refitted with of Kalifilcon A DDCL in comparison with Placebo CL (

Figure 5)

Furthermore, no discernible alterations in visual acuity (

Figure 6) or ocular health (Efron grading scale) were observed following either CL wear.

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to fit symptomatic CL wearers, who are at risk of CL dropout, with a modern DDCL to evaluate whether this intervention could lessen the symptoms they experience, enhance their overall CL experience, and ultimately reduce the likelihood of future dropout. The findings of this study demonstrate that, following the refitting of symptomatic wearers with Kalifilcon A DDCL, 67% become asymptomatic. This has the potential to directly impact clinical practice by reducing CL dropout rates.

The prescription of DDCL is a common practice among practitioners with the aim of improving the comfort of CL wearers [

9,

21] and decreasing the dropout rates of CL wearers. This is in agreement with the results of this study showing a significant improvement in CLDEQ-8 scores after fitting with Kalifilcon A DDCL. Specifically, the mean difference obtained between the baseline and the CL under study was 7.7, which is above the threshold for clinical significance (≥ 3; [

22]) and above the differences observed in similar studies [

9,

23]. The observed differences could be explained by the type of CL used, toric CLs being used in one of these studies, or by the size of the sample analysed, which is much larger in this study. Regarding the placebo effect, the mean difference obtained was 3.5, a value that is marginally above the threshold for a clinically significant difference, although lower than that found when refitting with Kalifilcon A DDCL. A statistically significant difference was observed between the results obtained with Kalifilcon A DDCL and placebo CL. This finding is in contrast with a previous study in which, although the experimental group demonstrated superior results in comparison to the placebo, these differences were not statistically significant [

10]. It is noteworthy that these discrepancies may be attributable to the considerably larger sample size employed in this study.

The impact of CL wear on vision-related quality of life has been previously examined using the NEI VFQ-25 in myopic patients, with a view to comparing the performance of monofocal versus multifocal contact lenses [

24], and following CL fitting for the management of irregular cornea [

25]. However, to the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to analyze vision-related quality of life after CL refitting using the NEI VFQ-25. The findings of this study demonstrate the impact of refitting on vision-related quality of life, which exhibited a significant enhancement. Notably, substantial improvements were observed in the subscales of ocular pain, role difficulties and colour vision. While placebo CL also led to an improvement in vision-related quality of life, this was more pronounced with Kalifilcon A DDCL. Finally, vision-related quality of life was consistently superior in non-symptomatic subjects who received Kalifilcon A DDCL, as compared to those who received placebo CL.

The Kalifilcon A DDCL performed better in terms of subjective ratings for comfort and overall satisfaction compared to placebo, whereas handling when putting and for removal were similar for both.

The study demonstrated an enhancement in tear film stability subsequent to the refitting with Kalifilcon A DDCL. Specifically, the clinical evaluation of auto tear break-up time exhibited enhancement following refitting with Kalifilcon A DDCL in comparison to the habitual CL, a phenomenon that was not observed in the placebo group. Furthermore, a substantial reduction was observed in both the TFSQ and A-TFSQ. CL wear can adversely affect the tear film and anterior ocular surface, leading to reduced wearing times and, eventually, to CL discontinuation [

26]. Indeed, it is a recognised fact that individuals who wear CL are more prone to experiencing symptoms of dry eye [

27], a factor that can directly impact the symptomatology during CL wear. The association between CL discomfort and precorneal tear film stability has been previously demonstrated [

28]. Consequently, the observed enhancement in tear film stability can be considered a potential underlying factor contributing to the mitigation of symptomatology and the enhancement of vision-related quality of life post-refitting with Kalifilcon A DDCL.

In summary, the present study demonstrates that the refitting of symptomatic CL wearers with Kalifilcon A DDCL leads to a significant reduction in symptomatology, improved tear film stability, and enhanced vision-related quality of life. These findings highlight the potential of contemporary DDCL materials in alleviating discomfort and reducing the risk of CL dropout, a pivotal challenge in clinical practice. Of particular note is the fact that the observed improvements could not be attributed to a placebo effect, thereby underscoring the clinical significance of material selection in optimising CL performance. Future research should explore the long-term effects of such interventions and evaluate their efficacy across broader patient populations. Furthermore, additional studies should aim to elucidate the underlying mechanisms driving these improvements, particularly regarding the role of tear film stability and ocular surface changes in symptom relief. The elucidation of these factors may contribute to the refinement of clinical guidelines and the development of targeted strategies for the management of symptomatic CL wearers at risk of discontinuation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.G.-A. and J.D.P.; methodology, J.M.S.-R. and Y.A..; validation, J.M.S.-R., Y.A. J.D.P. and D.G.-A.; formal analysis, J.M.S.-R.; investigation, J.M.S.-R. and Y.A.; resources, D.G.-A.; data curation, J.M.S.-R.; writing—original draft preparation, J.M.S.-R. and D.G.-A.; writing—review and editing, D.G.-A. and J.D.P.; supervision, D.G.-A and J.D.P..; project administration, D.G.-A and J.D.P..; funding acquisition, D.G.-A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by Bausch and Lomb. The funders played no role in the study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, writing of the report, or decision to submit the article for publication.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Universidad de Murcia (protocol code 3830/2022 and date of approval 11/07/2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article or supplementary material

Conflicts of Interest

This study was supported by Bausch and Lomb. The funders played no role in the study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, writing of the report, or decision to submit the article for publication.

References

- Guthrie, S.; Ng, A.; Woods, J.; Vega, J.; Orsborn, G.; Jones, L. Exploring the factors which impact overall satisfaction with single vision contact lenses. Cont Lens Anterior Eye 2022, 45, 101579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiros, A.; Villa-Collar, C.; Gutierrez, A.R.; Jorge, J.; Gonzalez-Meijome, J.M. Quality of life of myopic subjects with different methods of visual correction using the NEI RQL-42 questionnaire. Eye Contact Lens 2012, 38, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumbleton, K.; Caffery, B.; Dogru, M.; Hickson-Curran, S.; Kern, J.; Kojima, T.; Morgan, P.B.; Purslow, C.; Robertson, D.M.; Nelson, J.D.; et al. The TFOS International Workshop on Contact Lens Discomfort: report of the subcommittee on epidemiology. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2013, 54, TFOS20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucker, A.D.; Tichenor, A.A. A Review of Contact Lens Dropout. Clin Optom (Auckl) 2020, 12, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valencia-Nieto, L.; Lopez-de la Rosa, A.; Lopez-Miguel, A.; Gonzalez-Garcia, M.J. Clinical characterisation of contact lens discomfort progression. Cont Lens Anterior Eye 2024, 47, 102096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, J.J.; Willcox, M.D.; Bron, A.J.; Belmonte, C.; Ciolino, J.B.; Craig, J.P.; Dogru, M.; Foulks, G.N.; Jones, L.; Nelson, J.D.; et al. The TFOS International Workshop on Contact Lens Discomfort: executive summary. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2013, 54, TFOS7–TFOS13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandel, H. Quality-of-life outcomes of long-term contact lens wear: A systematic review. Cont Lens Anterior Eye 2022, 45, 101521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalmers, R.L.; Begley, C.G.; Moody, K.; Hickson-Curran, S.B. Contact Lens Dry Eye Questionnaire-8 (CLDEQ-8) and opinion of contact lens performance. Optom Vis Sci 2012, 89, 1435–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo-Del Arroyo, C.; Fernandez, I.; Novo-Diez, A.; Blanco-Vazquez, M.; Lopez-Miguel, A.; Gonzalez-Garcia, M.J. Contact Lens Discomfort Management: Outcomes of Common Interventions. Eye Contact Lens 2021, 47, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo-Del Arroyo, C.; Novo-Diez, A.; Blanco-Vazquez, M.; Fernandez, I.; Lopez-Miguel, A.; Gonzalez-Garcia, M.J. Does placebo effect exist in contact lens discomfort management? Cont Lens Anterior Eye 2021, 44, 101370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lievens, C.; Pucker, A.D.; Rayborn, E.; Kannarr, S.; Bickle, K.; Hogan, C.; Franklin, Q.X.; Christensen, M. Refitting contact lens dropouts into a modern daily disposable contact lens. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 2024, 44, 686–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Health Organization Quality of Life assessment (WHOQOL): position paper from the World Health Organization. Soc Sci Med 1995, 41, 1403–1409. [CrossRef]

- Mangione, C.M.; Lee, P.P.; Gutierrez, P.R.; Spritzer, K.; Berry, S.; Hays, R.D.; National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire Field Test, I. Development of the 25-item National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire. Arch Ophthalmol 2001, 119, 1050–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biousse, V.; Tusa, R.J.; Russell, B.; Azran, M.S.; Das, V.; Schubert, M.S.; Ward, M.; Newman, N.J. The use of contact lenses to treat visually symptomatic congenital nystagmus. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2004, 75, 314–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Hernandez, A.E.; Miquel-Lopez, C.; Garcia-Medina, J.J.; Garcia-Ayuso, D. Vision-related quality of life and near-work visual symptoms in patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Clin Exp Optom 2024, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okumura, Y.; Inomata, T.; Iwata, N.; Sung, J.; Fujimoto, K.; Fujio, K.; Midorikawa-Inomata, A.; Miura, M.; Akasaki, Y.; Murakami, A. A Review of Dry Eye Questionnaires: Measuring Patient-Reported Outcomes and Health-Related Quality of Life. Diagnostics (Basel) 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajabpour, M.; Kangari, H.; Pesudovs, K.; Khorrami-Nejad, M.; Rahmani, S.; Mohaghegh, S.; Moradnejad, S. Refractive error and vision related quality of life. BMC Ophthalmol 2024, 24, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garza-Leon, M.; Amparo, F.; Ortiz, G.; de la Parra-Colin, P.; Sanchez-Huerta, V.; Beltran, F.; Hernandez-Quintela, E. Translation and validation of the contact lens dry eye questionnaire-8 (CLDEQ-8) to the Spanish language. Cont Lens Anterior Eye 2019, 42, 155–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolffsohn, J.S.; Arita, R.; Chalmers, R.; Djalilian, A.; Dogru, M.; Dumbleton, K.; Gupta, P.K.; Karpecki, P.; Lazreg, S.; Pult, H.; et al. TFOS DEWS II Diagnostic Methodology report. Ocul Surf 2017, 15, 539–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Marques, J.V.; Macedo-De-Araujo, R.J.; McAlinden, C.; Faria-Ribeiro, M.; Cervino, A.; Gonzalez-Meijome, J.M. Short-term tear film stability, optical quality and visual performance in two dual-focus contact lenses for myopia control with different optical designs. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 2022, 42, 1062–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Queiruga, J.; Pena-Verdeal, H.; Ferreiro-Figueiras, D.; Noya-Padin, V.; Giraldez, M.J.; Yebra-Pimentel, E. Assessing neophyte response to daily disposable silicone hydrogel contact lenses: A randomised clinical trial investigation over one month. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 2024, 44, 876–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalmers, R.L.; Keay, L.; Hickson-Curran, S.B.; Gleason, W.J. Cutoff score and responsiveness of the 8-item Contact Lens Dry Eye Questionnaire (CLDEQ-8) in a Large daily disposable contact lens registry. Cont Lens Anterior Eye 2016, 39, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, K.; Mashouf, J.; Hall, B. Comfort After Refitting Symptomatic Habitual Reusable Toric Lens Wearers with a New Daily Disposable Contact Lens for Astigmatism. Clin Ophthalmol 2023, 17, 3235–3241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durmaz Engin, C.; Yapici, B.; Koksaldi, S.; Vupa Cilengiroglu, O. Visual performance and quality of life in myopic adolescents with pupil-optimised multifocal versus single-vision contact lenses. Clin Exp Optom 2024, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaji, J.; Subramanian, M.; Saravanan, S.; Narayanan, A. Cost and benefits of availing specialty contact lenses for irregular cornea and ocular surface diseases from patient perspectives. Cont Lens Anterior Eye 2025, 102385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downie, L.E.; Craig, J.P. Tear film evaluation and management in soft contact lens wear: a systematic approach. Clin Exp Optom 2017, 100, 438–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Ayuso, D.; Di Pierdomenico, J.; Moya-Rodriguez, E.; Valiente-Soriano, F.J.; Galindo-Romero, C.; Sobrado-Calvo, P. Assessment of dry eye symptoms among university students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Exp Optom 2022, 105, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillon, M.; Dumbleton, K.A.; Theodoratos, P.; Wong, S.; Patel, K.; Banks, G.; Patel, T. Association Between Contact Lens Discomfort and Pre-lens Tear Film Kinetics. Optom Vis Sci 2016, 93, 881–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).