Submitted:

04 December 2024

Posted:

04 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

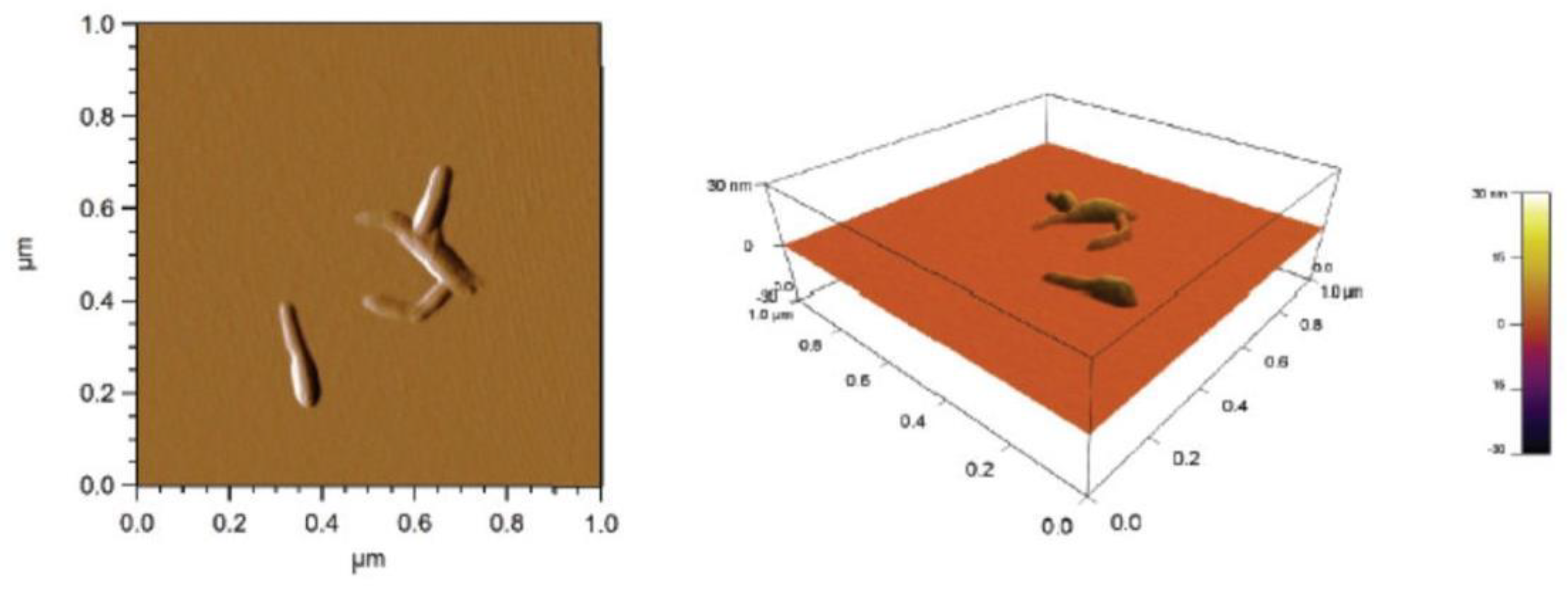

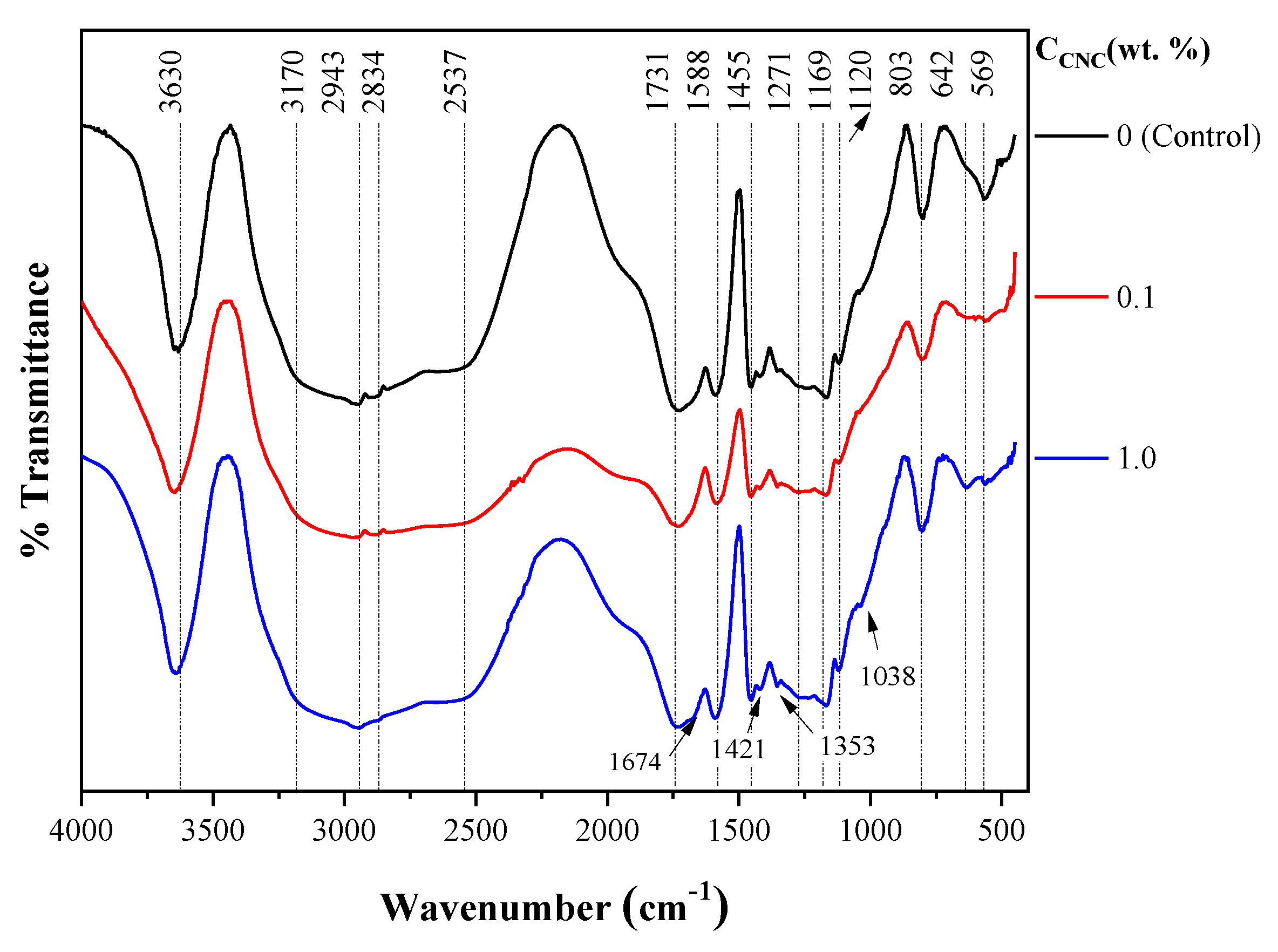

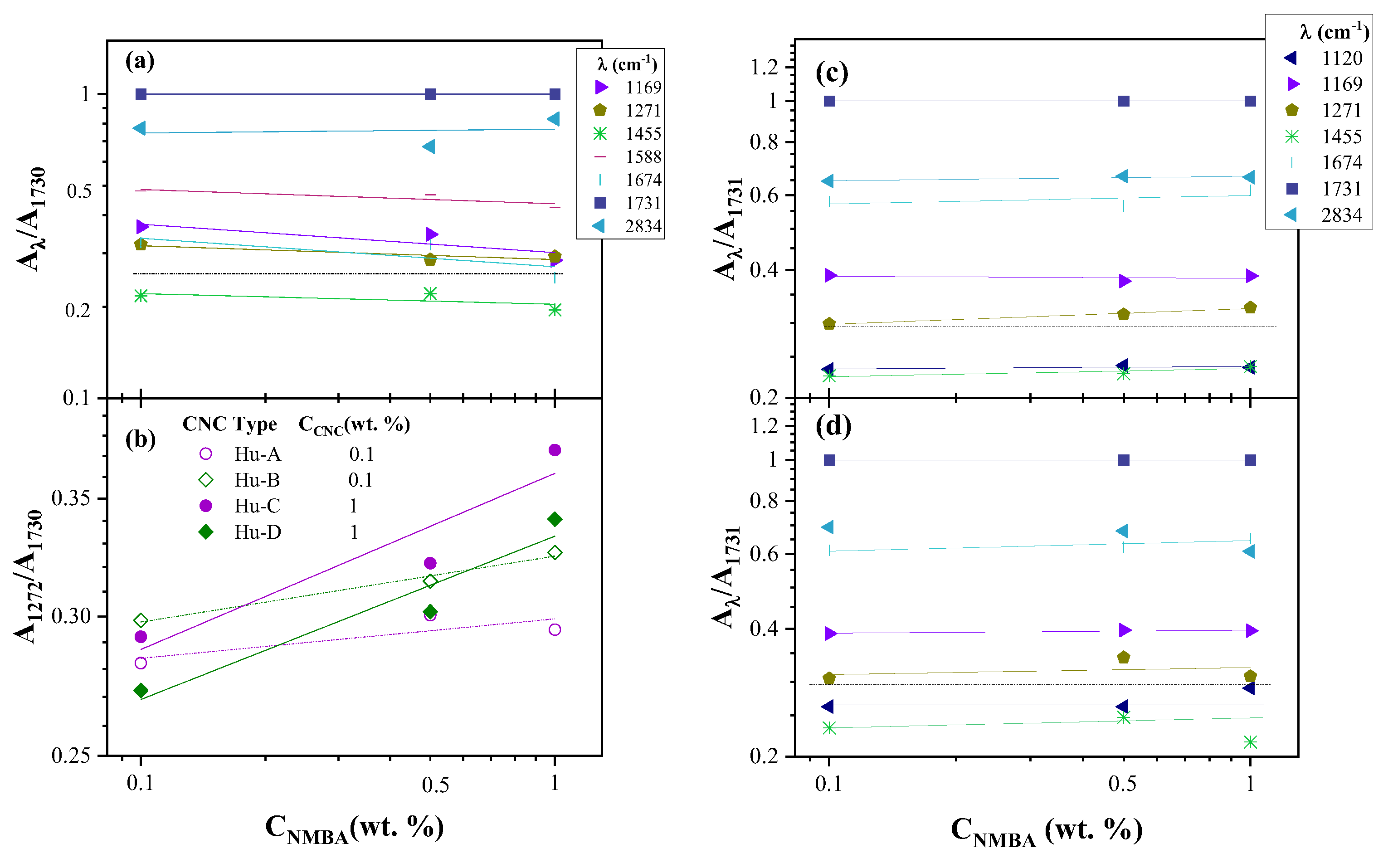

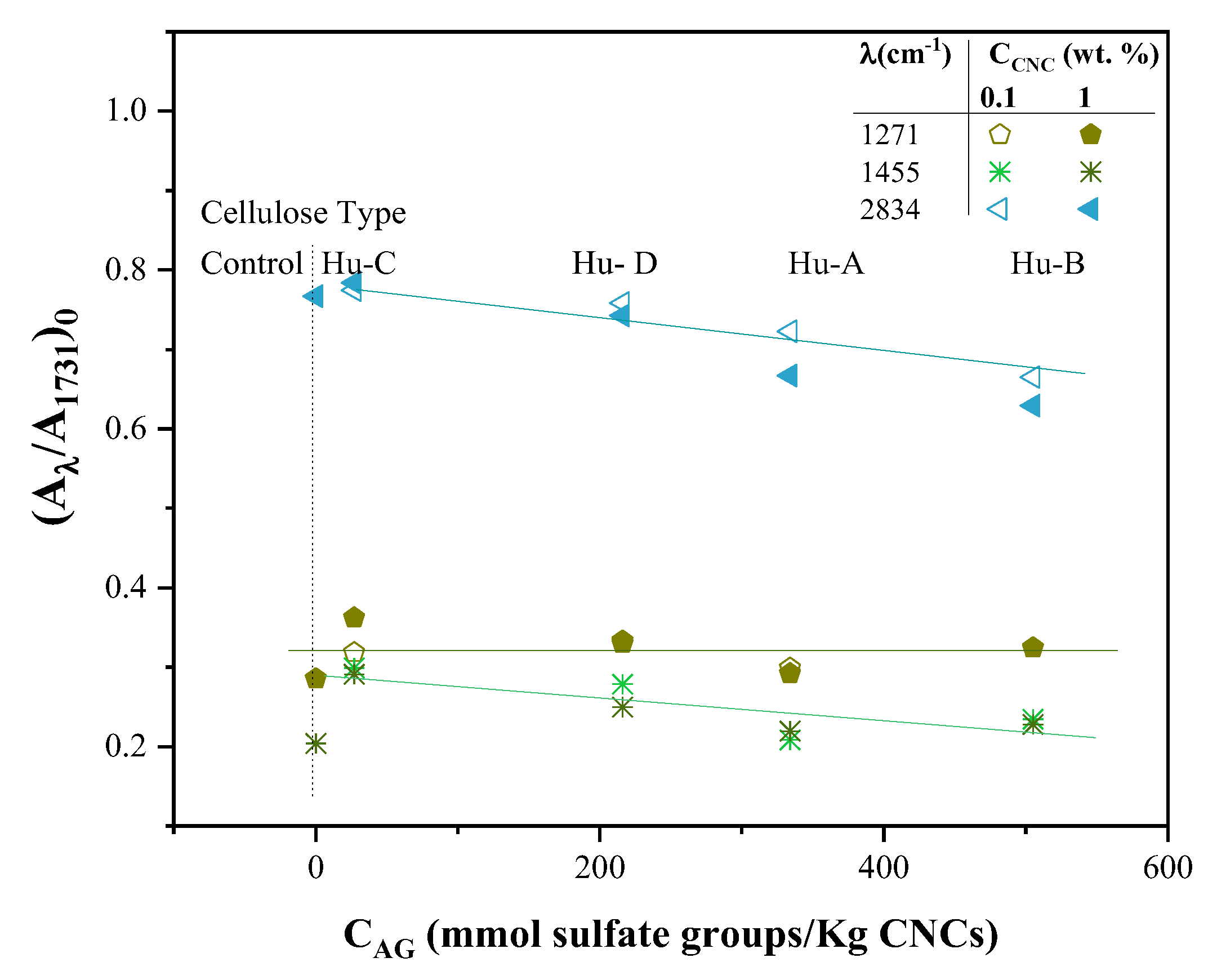

In this work, cellulose nanocrystals (CNC) were obtained from the wood of Acacia far-nesiana L. Willd (huizache) by acid hydrolysis. These were used to reinforce polyacrylic acid-co-acrylamide (AAc/AAm) hydrogels synthesized in a solution process by in situ free radical photo-polymerization. The nanomaterials were characterized by atomic force microscopy and dynamic light scattering (DLS) and the residual charge on CNC; the nanohydrogels were characterized by infrared spectroscopy, scanning electron microscopy, swelling kinetics, and Young's modulus. The soluble grade cellulose presented 94.6% α-cellulose, 0.5% β-cellulose, and 2.7% γ-cellulose, a viscosity of 8.25 cp, and a degree of polymerization (DP) of 706. The CNC averaged 180 nm in length and 20 nm in width. In the nanohydrogels, it was observed that the Schott kinetic model was followed at times lower than 500 h; after that, the swelling kinetic behavior is linear. The re-sults show that the hydrogel swelling capacity depends on crosslinking agent and CNC concen-tration as the chemical and morphological CNC properties rather than a CNC source. The pres-ence of CNC decreases the swelling degree compared to hydrogels without CNC. Young's modu-lus increased with CNC presence and depended on CNC characteristics as crosslinking agent and concentration.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Soluble Grade Pulp Properties

2.2. Cellulose Nanocrystals Characteristics

2.3. Hydrogels Characterization

2.3.1. FTIR Spectroscopy of Hydrogels

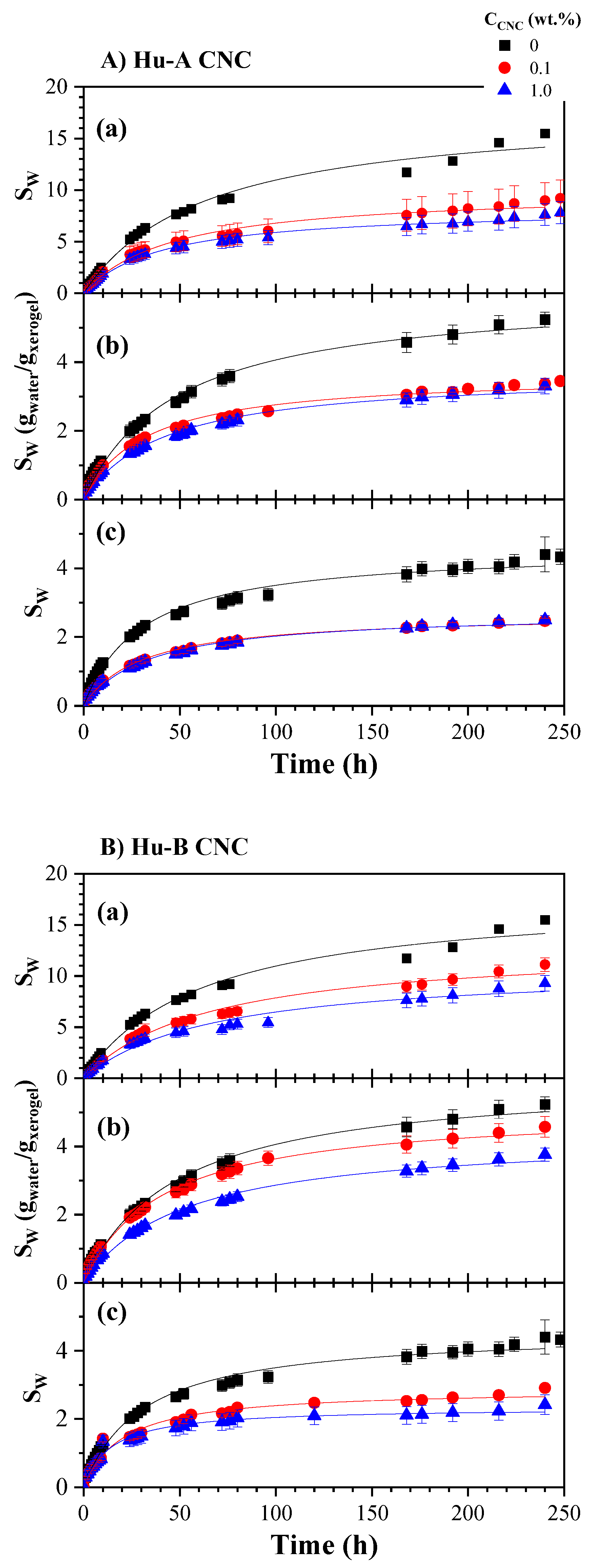

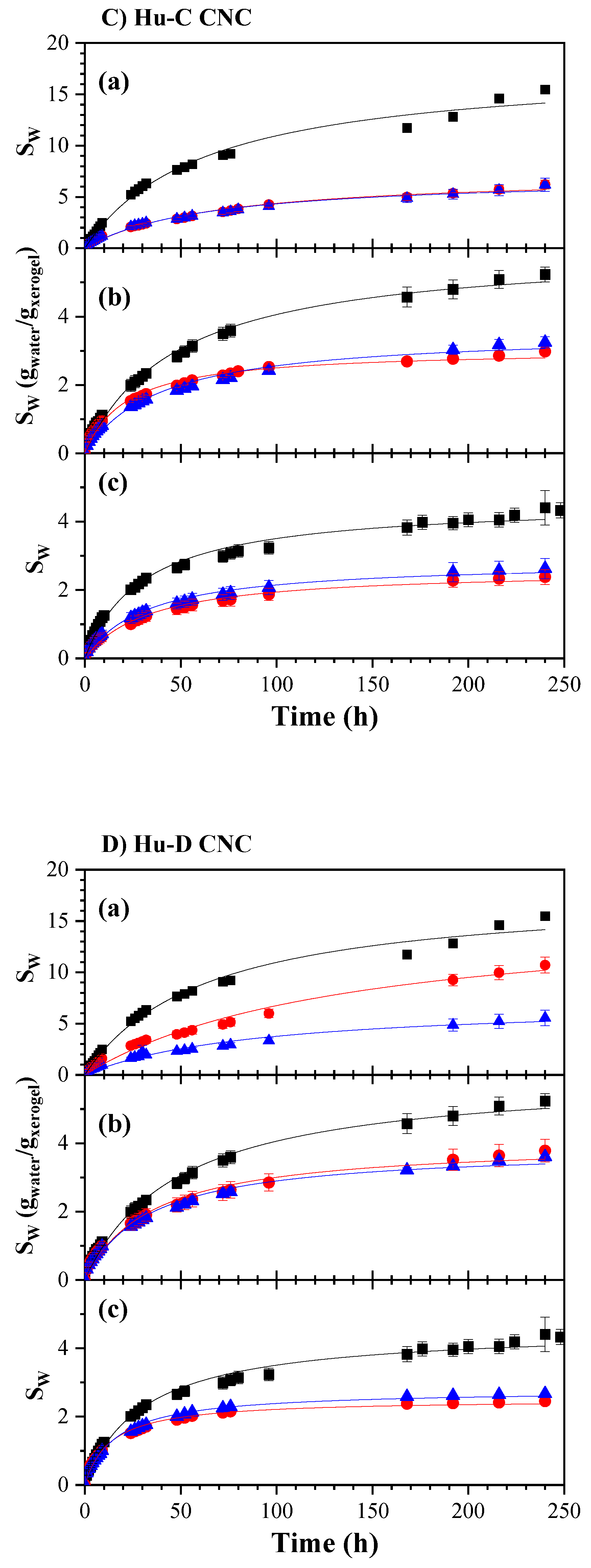

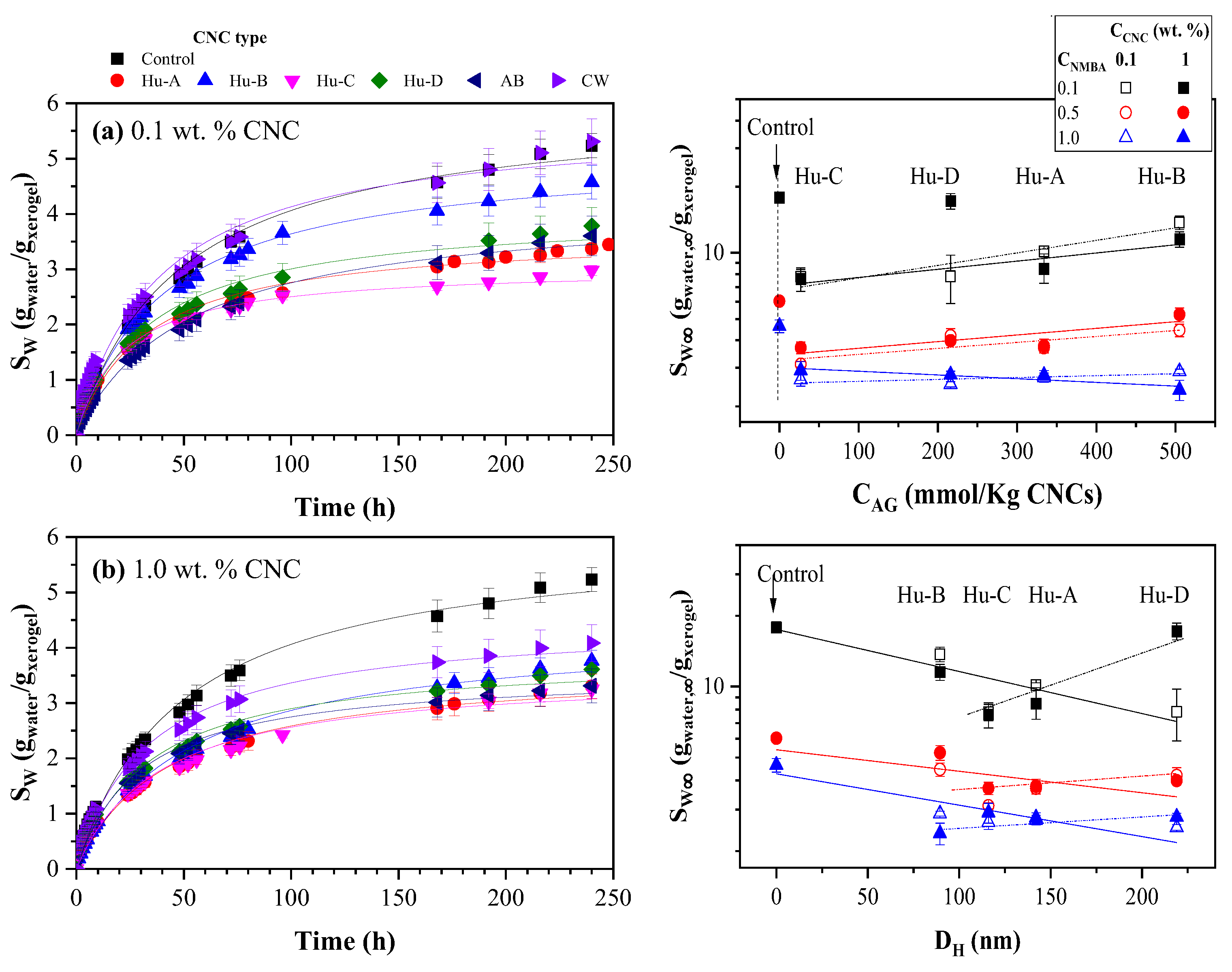

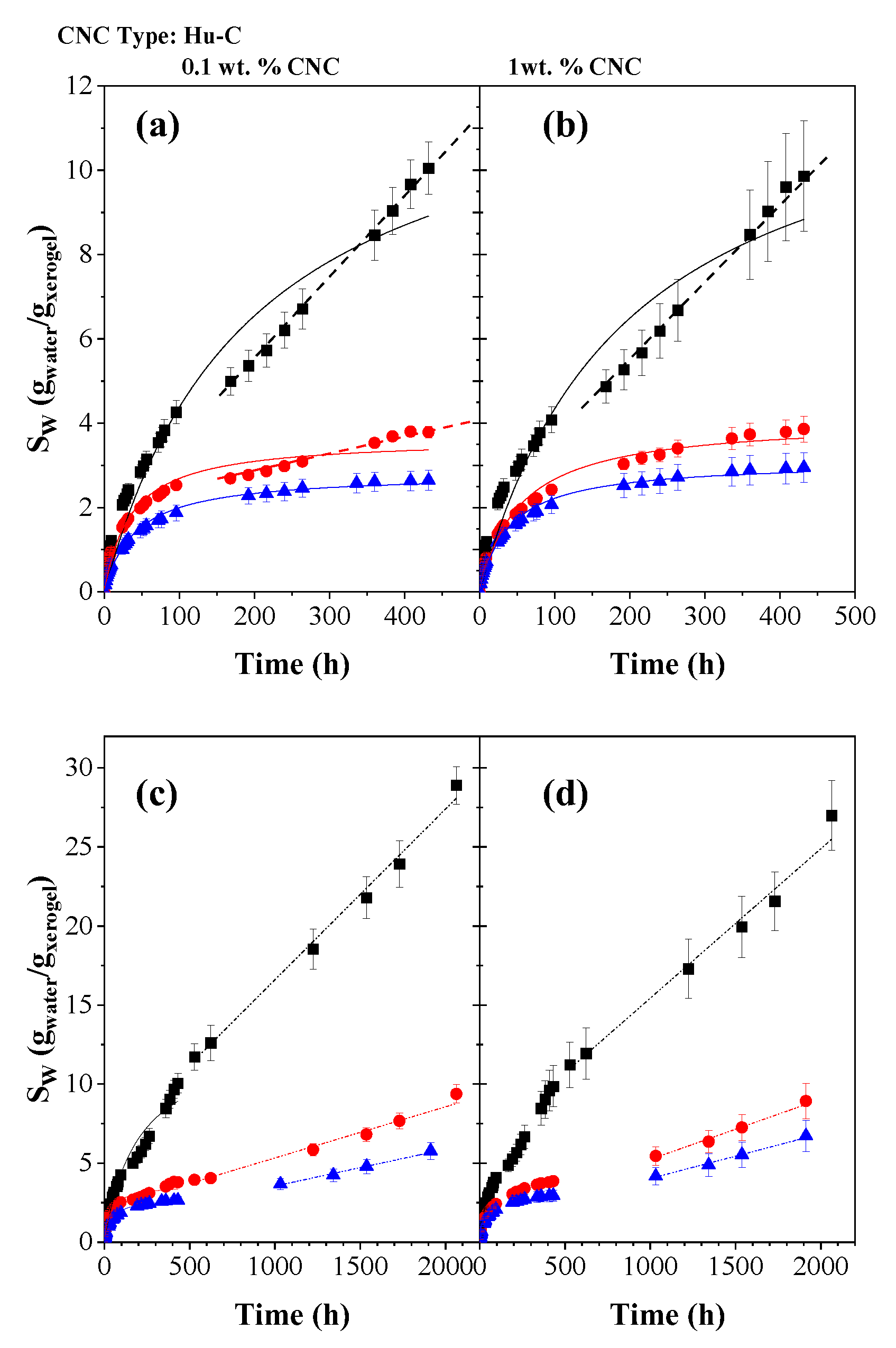

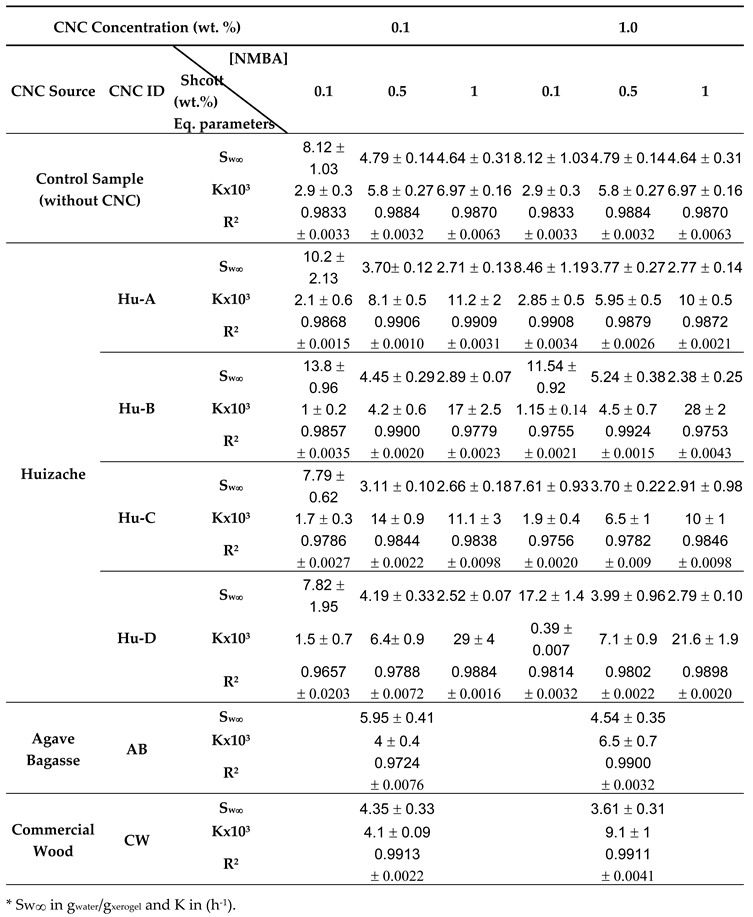

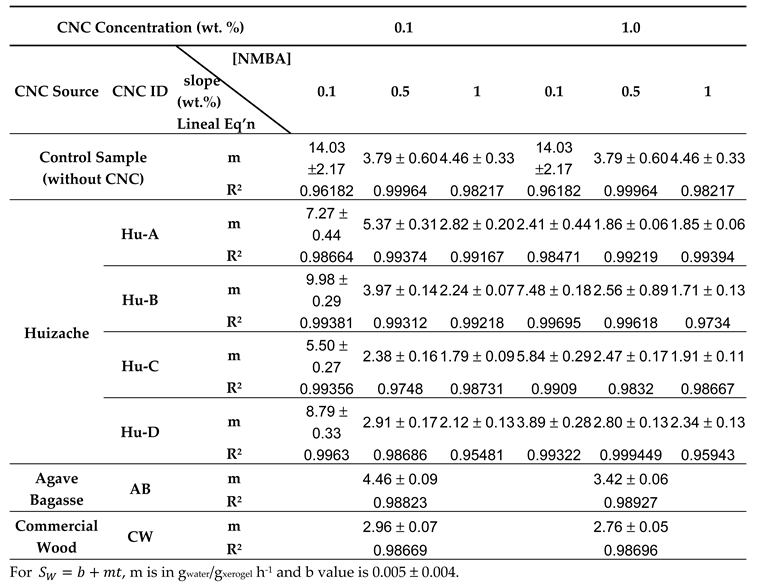

2.3.2. Hydrogels Swelling Kinetic

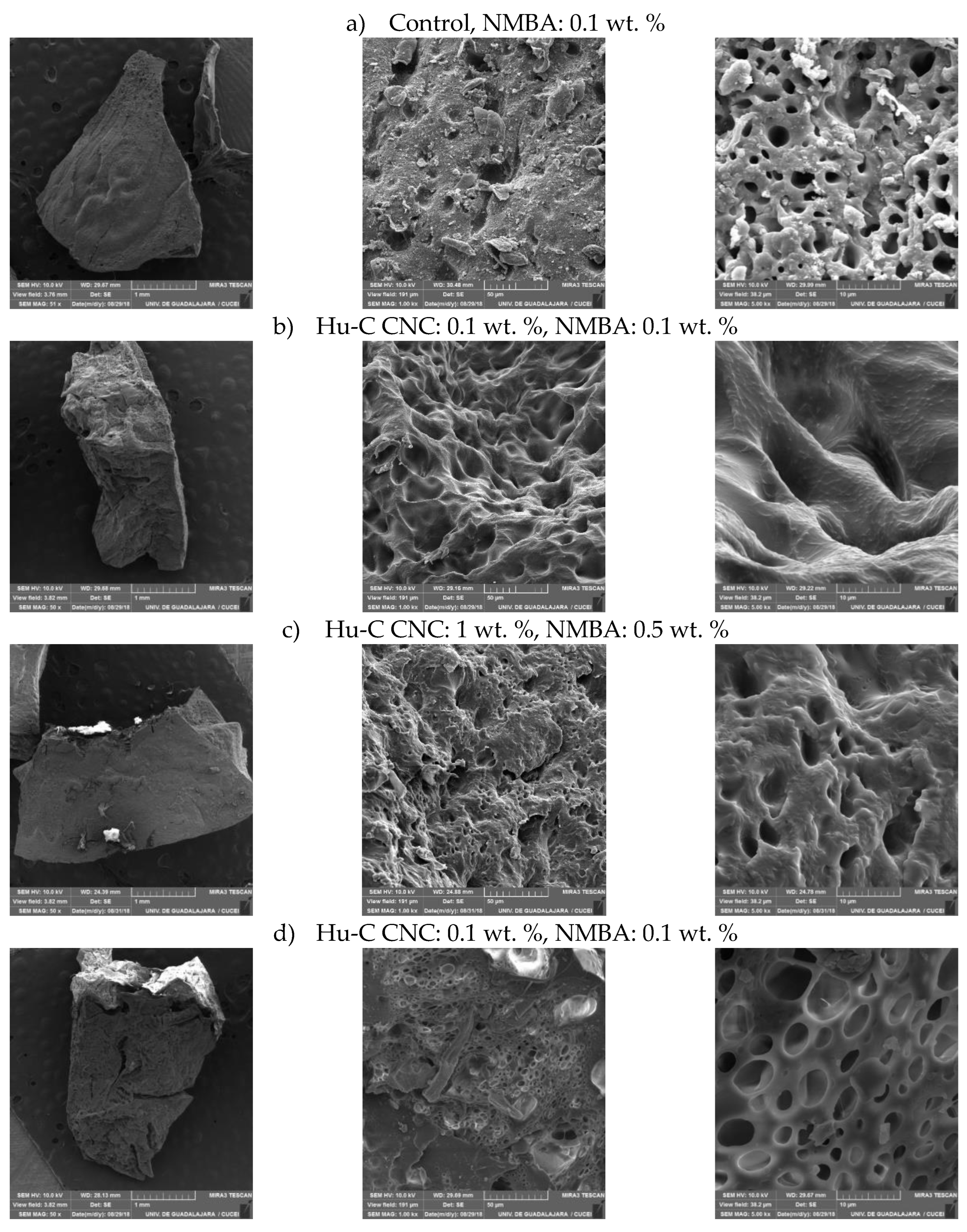

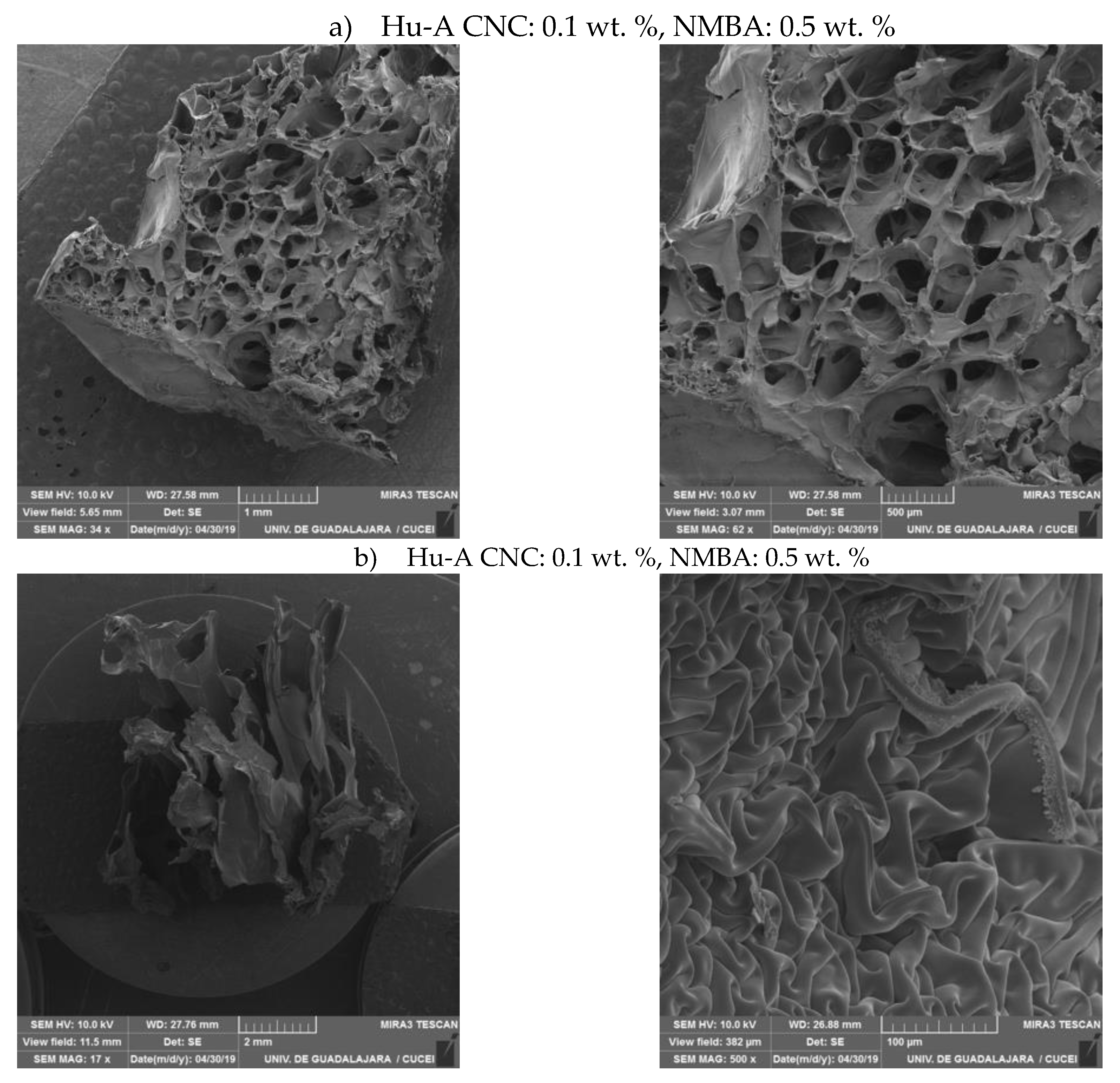

2.3.3. Hydrogels Morphology by SEM

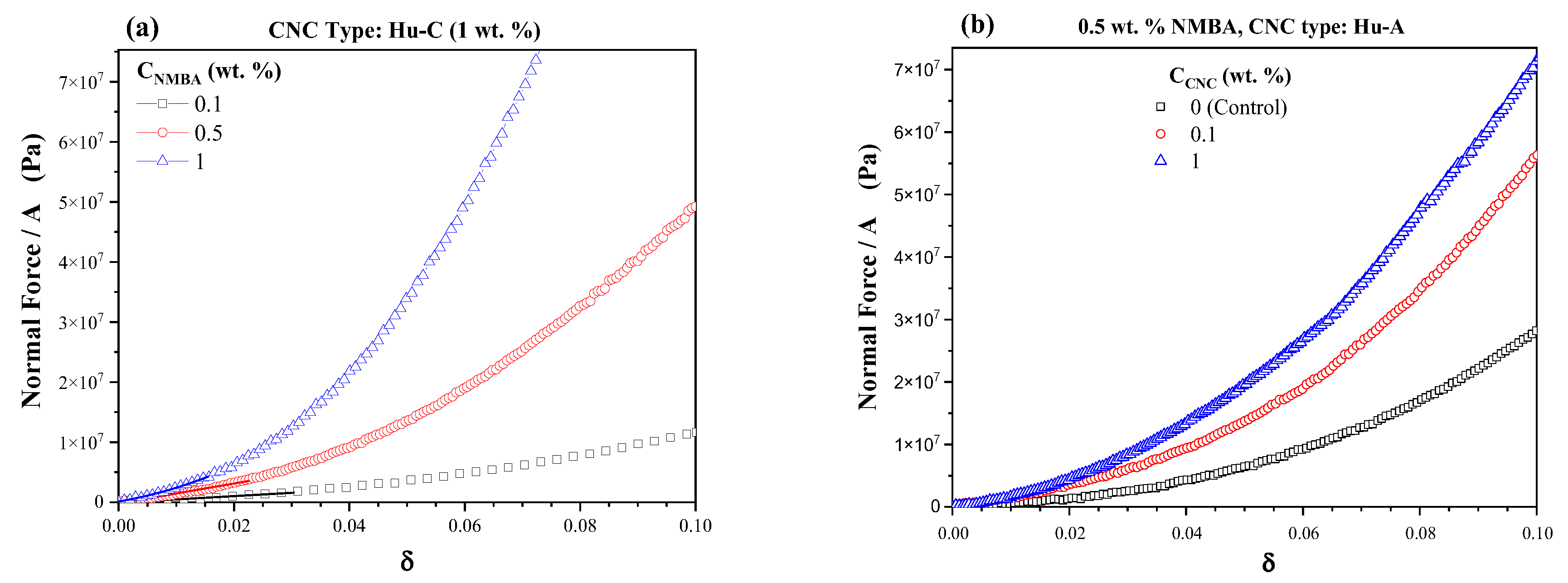

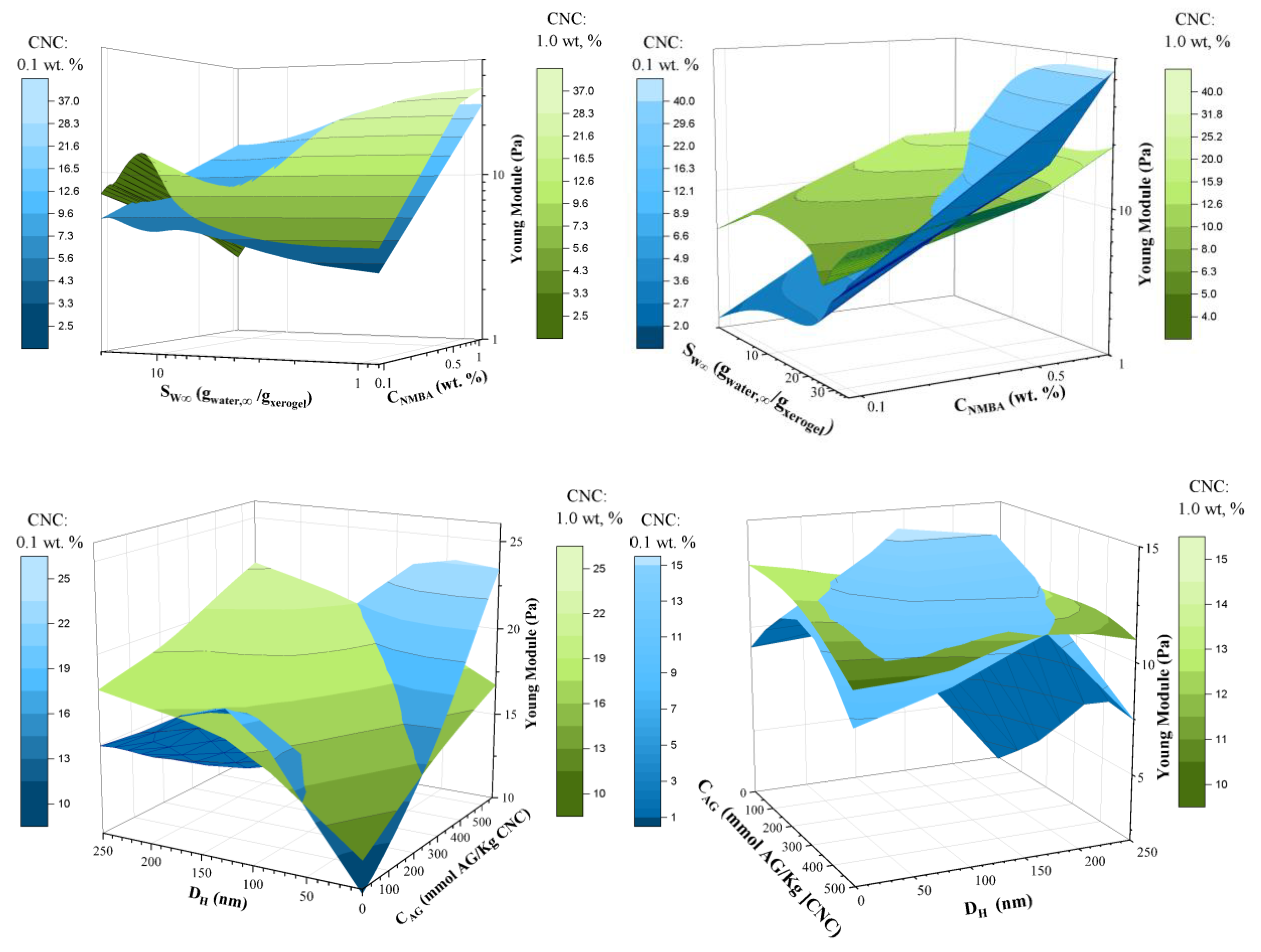

2.3.4. Hydrogels Rheological Characterization

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Preparation and Characterization of Soluble Grade Cellulose Pulp

4.3. Obtaining and Characterization of Cellulose Nanocrystals

4.3.1. Determination of the Residual Charge in NCC, by Conductance Titration

4.3.2. Particle Size Distribution by Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS)

4.3.3. AFM Morphological Analysis

4.3.4. Hydrogel Synthesis

4.3.5. FTIR Spectroscopy

4.3.6. Swelling Kinetics

4.3.7. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

4.3.8. Rheological Characterization of Hydrogels

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Reddy, N. S.; Rao, K. S. V. K. Polymeric hydrogels : Recent advances in Toxic metal ion removal and anticancer drug delivery applications. Indian Journal of Advances in Chemical Science 2016, 4(2), 214–234. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, C.; Wu, Q. A novel polyacrylamide nanocomposite hydrogel reinforced with natural chitosan nanofibers. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2011, 84(1), 155–162.

- Swain, S. K.; Prusty, K. Biomedical applications of acrylic-based nanohydrogels. Journal of Materials Science 2018, 53(4), 2303–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara-Valencia, V. A.; Dávila-Soto, H.; Moscoso-Sánchez, F. J.; Figueroa-Ochoa, E. B.; Carvajal-Ramos, F.; Fernández-Escamilla, V. V. A.; Soltero-Martinez, J.F.A.; Macias-Balleza, E.R.; Enríquez, S. G. The use of polysaccharides extracted from seed of Persea americana var. Hass on the synthesis of acrylic hydrogels. Quimica Nova 2018, 41, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, S. J.; De Smedt, S. C.; Wahls, M. W. C.; Demeester, J.; Kettenes-van Den Bosch, J. J.; Hennink, W. E. Novel self-assembled hydrogels by stereocomplex formation in aqueous solution of enantiomeric lactic acid oligomers grafted to dextran. Macromolecules 2000, 33(10), 3680–3686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Valores y usos de especies importantes de árboles y arbustos en la región sur-sureste de México. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations 2023. https://www.fao.org/3/j0606s/j0606s0a.htm consultado 06 de septiembre de 2023.

- Smith, T. P.; Wilson, S. B.; Marble, S. C.; Xu, J. Propagation for commercial production of sweet acacia (Vachellia farnesiana): a native plant with ornamental potential. Native Plants Journal 2022, 23(3), 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wilson, S. B.; Vendrame, W. A.; Beleski, D. G. Micropropagation of sweet acacia (Vachellia farnesiana), an underutilized ornamental tree. In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology-Plant 2023, 59(1), 74-82.

- Ramirez, R. G.; Ledezma-Torres, R. A. Forage utilization from native shrubs Acacia rigidula and Acacia farnesiana by goats and sheep. Small Ruminant Research 1997, 25(1), 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Winder, L. R.; Goñi-Cedeño, S.; Olguin-Lara, P. A.; Díaz-Salgado, G.; Arriaga-Jordan, C. M. Huizache (Acacia farnesiana) whole pods (flesh and seeds) as an alternative feed for sheep in Mexico. Tropical Animal Health and Production 2009, 41, 1615–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgadillo-Puga, C.; Cuchillo-Hilario, M.; León-Ortiz, L.; Ramírez-Rodríguez, A.; Cabiddu, A.; Navarro-Ocaña, A.; Morales-Romero, A.M.; Medina-Campos, O. N.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J. Goats’ feeding supplementation with Acacia farnesiana pods and their relationship with milk composition: Fatty acids, polyphenols, and antioxidant activity. Animals 2019, 9(8), 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrientos-Ramírez, L.; Vargas-Radillo, J. J.; Rodríguez-Rivas, A.; Ochoa-Ruíz, H. G.; Navarro-Arzate, F.; Zorrilla, J. Evaluation of characteristics of huizache (Acacia farnesiana (L.) Willd.) fruit for potential use in leather tanning or animal feeding. Madera y bosques 2012, 18(3), 23-35.

- Sankaran, K. V.; Suresh, T. A. Invasive alien plants in the forests of Asia and the Pacific. RAP Publication, Bangkok, Thailand 2013.

- Khan, I. U.; Haleem, A.; Khan, A. U. Non-edible plant seeds of Acacia farnesiana as a new and effective source for biofuel production. RSC advances 2022, 12(33), 21223–21234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Casillas, R.; López-López, M.C.; Becerra-Aguilar, B.; Dávalos-Olivares, F.; Satyanarayana, KG. Obtaining dissolving grade cellulose from the huizache (Acacia farnesiana L. Willd.) plant. BioRecursos 2019, 14 (2), 3301-3318.

- Ramírez-Casillas, R.; López-López, M.; Becerra-Aguilar, B.; Dávalos-Olivares, F.; Satyanarayana, K. G. Preparation and characterization of cellulose nanocrystals using soluble grade cellulose from acid hydrolysis of Huizache (Acacia farnesiana L. Willd.). BioResources 2019, 14(2), 3319-3338.

- AL-Tameemi, A. R.; Al-Edany, T. Y.; Attaha, A. H. Phytoremediation of crude oil contaminated soil by Acacia farnesiana l. willd. and spraying glutathione. University of Thi-Qar Journal of Science 2021, 8(1), 59-66.

- Jiménez M., E.; Prieto G., F.; Prieto M., J.; Acevedo S., O. A.; Rodríguez L., R.; Otazo S., E. M. Utilization of Waste Agaves: Potential for Obtaining Cellulose Pulp. Ciência e Técnica Vitivinícola 2014, 29 (11),138–152.

- Berglund, L.; Noël, M.; Aitomäki, Y.; Öman, T.; Oksman, K. Production potential of cellulose nanofibers from industrial residues: Efficiency and nanofiber characteristics. Industrial Crops and Products 2016, 92, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nechyporchuk, O.; Belgacem, M. N.; Bras, J. Production of cellulose nanofibrils: A review of recent advances. Industrial Crops and Products 2016, 93, 2–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiniati, I.; Hrymak, A. N.; Margaritis, A. Recent developments in the production and applications of bacterial cellulose fibers and nanocrystals. Critical reviews in biotechnology 2017, 37(4), 510–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trache, D.; Hussin, M. H.; Haafiz, M. M.; Thakur, V. K. Recent progress in cellulose nanocrystals: sources and production. Nanoscale 2017, 9(5), 1763–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rånby, B. G.; Banderet, A.; Sillén, L. G. Aqueous Colloidal Solutions of Cellulose Micelles. Acta Chemica Scandinavica 1949, 3, 649–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rånby, B. G. Fibrous macromolecular systems. Cellulose and muscle. The colloidal properties of cellulose micelles. Discuss. Faraday Soc. 1951, 11(0), 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, Y.; Lucian A., L; Rojas J., O. Cellulose nanocrystals: chemistry, self-assembly, and applications. Chemical reviews 2010, 110.6, 3479–3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, R. J.; Martini, A.; Nairn, J.; Simonsen, J.; Youngblood, J. Cellulose nanomaterials review: structure, properties and nanocomposites. Chemical Society Reviews 2011, 40.7, 3941–3994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fachri, R.; Rizal, S.; Huzni, S.; Ikramullah, I.; Aprilia, S. Production of Cellulose Nanocrystal (CNC) Combine with Silane Treatment from Pennisetum Purpureum via Acid Hydrolysis. In International Conference on Experimental and Computational Mechanics in Engineering 2022, 535-543. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.

- Chen, L.; Wang, Q.; Hirth, K.; Baez, C.; Agarwal, U. P.; Zhu, J. Y. Tailoring the yield and characteristics of wood cellulose nanocrystals (CNC) using concentrated acid hydrolysis. Cellulose 2015, 22, 1753–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Zhang, M.; Hou, Q.; Liu, R.; Wu, T.; Si, C. Further characterization of cellulose nanocrystal (CNC) preparation from sulfuric acid hydrolysis of cotton fibers. Cellulose 2016, 23, 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-Sánchez, M. A., Díaz-Vidal, T., Navarro-Hermosillo, A. B., Figueroa-Ochoa, E. B., Ramírez Casillas, R., Anzaldo Hernández, J., Rosales-Rivera, L.C.; Soltero-Martinez, J.F.A.; García-Enriquez S.; Macías-Balleza, E. R. Optimization of the obtaining of cellulose nanocrystals from Agave equilana weber var. Azul Bagasse by acid hydrolysis. Nanomaterials 2021, 11(2), 520.

- Wang, R.; Chen, L.; Zhu, J. Y.; Yang, R. Tailored and integrated production of carboxylated cellulose nanocrystals (CNC) with nanofibrils (CNF) through maleic acid hydrolysis. ChemNanoMat 2017, 3(5), 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamad, W. Y. Cellulose nanocrystals: properties, production and applications. John Wiley & Sons. 2017.

- Fajardo, A. R.; Pereira, A. G.; Muniz, E. C. Hydrogels Nanocomposites Based on Crystals, Whiskers and Fibrils Derived from Biopolymers. In: Thakur, V., Thakur, M. (eds) Eco-friendly Polymer Nanocomposites. Advanced Structured Materials, vol 74. Springer, New Delhi. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Wu, Q.; Yue, Y.; Zhang, Q. Application of rod-shaped cellulose nanocrystals in polyacrylamide hydrogels. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 2011, 353(1), 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Han, C. R.; Xu, F.; Sun, R. C. Simple approach to reinforce hydrogels with cellulose nanocrystals. Nanoscale 2014, 6(11), 5934–5943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, H.; Liu, W.; Zhang, M.; Si, C.; Zhang, X.; Li, B. Cellulose nanocrystals and cellulose nanofibrils based hydrogels for biomedical applications. Carbohydrate polymers 2019, 209, 130–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abitbol, T.; Johnstone, T.; Quinn, T. M.; Gray, D. G. Reinforcement with cellulose nanocrystals of poly (vinyl alcohol) hydrogels prepared by cyclic freezing and thawing. Soft Matter 2011, 7(6), 2373–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Zhu, W.; Li, X.; Yu, Z. A novel mechanical robust, self-healing and shape memory hydrogel based on PVA reinforced by cellulose nanocrystal. Materials Letters 2020, 260, 126884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, S.; Wang, Q.; Fu, X.; Fatehi, P. Performance of polyvinyl alcohol hydrogel reinforced with lignin-containing cellulose nanocrystals. Cellulose 2020, 27, 8725–8743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, Z.; Zuo, M.; Zeng, X.; Tang, X.; Sun, Y.; Lin, L. Stretchable, freezing-tolerant conductive hydrogel for wearable electronics reinforced by cellulose nanocrystals toward multiple hydrogen bonding. Carbohydrate Polymers 2022, 280, 119018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Huang, J.; Chang, P. R.; Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, D.; Yu, J.; Chen, J. Structure and properties of polysaccharide nanocrystal-doped supramolecular hydrogels based on cyclodextrin inclusion. Polymer 2010, 51(19), 4398–4407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Han, C. R.; Duan, J. F.; Xu, F.; Sun, R. C. Mechanical and viscoelastic properties of cellulose nanocrystals reinforced poly (ethylene glycol) nanocomposite hydrogels. ACS applied materials & interfaces 2013, 5(8), 3199-3207.

- Cha, R.; He, Z.; Ni, Y. Preparation and characterization of thermal/pH-sensitive hydrogel from carboxylated nanocrystalline cellulose. Carbohydrate Polymers 2012, 88(2), 713–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubik, K.; Singhsa, P.; Wang, Y.; Manuspiya, H.; Narain, R. Thermo-Responsive Poly(N-Isopropylacrylamide)-Cellulose Nanocrystals Hybrid Hydrogels for Wound Dressing. Polymers 2017, 9, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Cheng, Q.; Feng, S.; Zhang, L.; Chang, C. Shear-aligned tunicate-cellulose-nanocrystal-reinforced hydrogels with mechano-thermo-chromic properties. Journal of Materials Chemistry C 2021, 9(19), 6344–6350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Han, C. Mechanically viscoelastic properties of cellulose nanocrystals skeleton reinforced hierarchical composite hydrogels. ACS applied materials & interfaces 2016, 8(38), 25621-25630.

- Voronova, M. I.; Surov, O. V.; Afineevskii, A. V.; Zakharov, A. G. Properties of polyacrylamide composites reinforced by cellulose nanocrystals. Heliyon 2020, 6(11).

- Ortega, A.; Valencia, S.; Rivera, E.; Segura, T.; Burillo, G. Reinforcement of Acrylamide Hydrogels with Cellulose Nanocrystals Using Gamma Radiation for Antibiotic Drug Delivery. Gels 2023, 9, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-Amezcua, R. M., Villanueva-Silva, R. J., Muñoz-García, R. O., Macias-Balleza, E. R., Sydenstricker Flores-Sahagun, M. T., Lomelí-Ramírez, M. G., Torres-Rendón, J. G.; Garcia-Enriquez, S. Preparation of Agave tequilana Weber nanocrystalline cellulose and its use as reinforcement for acrylic hydrogels. BioResources 2021, 16(2), 2731.

- Wan Ishak, W. H.; Yong Jia, O.; Ahmad, I. pH-responsive gamma-irradiated poly (acrylic acid)-cellulose-nanocrystal-reinforced hydrogels. Polymers 2020, 12(9), 1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Idrissi, A.; El Gharrak, A.; Achagri, G.; Essamlali, Y.; Amadine, O.; Akil, A.; Sair, S.; Zahouily, M. Synthesis of urea-containing sodium alginate-g-poly (acrylic acid-co-acrylamide) superabsorbent-fertilizer hydrogel reinforced with carboxylated cellulose nanocrystals for efficient water and nitrogen utilization. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2022, 10(5), 108282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Gorair, A. S; Sayed, A.; Mahmoud, G. A. Engineered superabsorbent nanocomposite reinforced with cellulose nanocrystals for remediation of basic dyes: isotherm, kinetic, and thermodynamic studies. Polymers 2022, 14(3), 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.; Kadla, J. F. Effect of nanofillers on carboxymethyl cellulose/hydroxyethyl cellulose hydrogels. Journal of applied polymer science 2009, 114(3), 1664–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishak, W. H. W.; Rosli, N. A.; Ahmad, I.; Ramli, S.; Amin, M. C. I. M. Drug delivery and in vitro biocompatibility studies of gelatin-nanocellulose smart hydrogels cross-linked with gamma radiation. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2021, 15, 7145–7157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Nascimento, D. M.; Nunes, Y. L.; Feitosa, J. P.; Dufresne, A.; Rosa, M. D. F. Cellulose nanocrystals-reinforced core-shell hydrogels for sustained release of fertilizer and water retention. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2022, 216, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Javaid, M. U.; Pan, C.; Yu, G.; Berry, R. M.; Tam, K. C. Self-healing stimuli-responsive cellulose nanocrystal hydrogels. Carbohydrate polymers 2020, 229, 115486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Huang, D.; Chen, X.; Liu, H.; Feng, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, X.; Lin, Q. A novel and homogeneous scaffold material: preparation and evaluation of alginate/bacterial cellulose nanocrystals/collagen composite hydrogel for tissue engineering. Polymer Bulletin 2018, 75, 985–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleimani, S.; Heydari, A.; Fattahi, M.; Motamedisade, A. Calcium alginate hydrogels reinforced with cellulose nanocrystals for methylene blue adsorption: Synthesis, characterization, and modelling. Industrial Crops and Products 2023, 192, 115999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleimani, S.; Heydari, A.; Fattahi, M. Swelling prediction of calcium alginate/cellulose nanocrystal hydrogels using response surface methodology and artificial neural network. Industrial Crops and Products 2023, 192, 116094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olad, A.; Doustdar, F.; Gharekhani, H. Fabrication and characterization of a starch-based superabsorbent hydrogel composite reinforced with cellulose nanocrystals from potato peel waste. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2020, 601, 124962.

- Catori, D. M.; Fragal, E. H.; Messias, I.; Garcia, F. P.; Nakamura, C. V.; Rubira, A. F. Development of composite hydrogel based on hydroxyapatite mineralization over pectin reinforced with cellulose nanocrystal. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2021, 167, 726–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Dong, X.; Han, B.; Huang, H.; Qi, M. Cellulose nanocrystal/collagen hydrogels reinforced by anisotropic structure: Shear viscoelasticity and related strengthening mechanism. Composites Communications 2020, 21, 100374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torabizadeh, F.; Fadaie, M.; Mirzaei, E.; Sadeghi, S.; Nejabat, G. R. Tailoring structural properties, mechanical behavior and cellular performance of collagen hydrogel through incorporation of cellulose nanofibrils and cellulose nanocrystals: A comparative study. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2022, 219, 438–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, D.K.; Ganguly, K.; Hexiu, J.; Dutta, S.D.; Patil, T.V.; Lim, K.T. Functionalized chitosan/spherical nanocellulose-based hydrogel with superior antibacterial efficiency for wound healing. Carbohydrate Polymers 2022, 284, 119202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maturavongsadit, P.; Paravyan, G.; Shrivastava, R.; Benhabbour, S. R. Thermo-/pH-responsive chitosan-cellulose nanocrystals based hydrogel with tunable mechanical properties for tissue regeneration applications. Materialia 2020, 12, 100681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López L., M. C. Estudio biométrico y químico de la planta silvestre huizache (Acacia farnesiana) y su influencia en la calidad de fibra celulósica. Bachelor's thesis in Biology. University of Guadalajara 2012.

- MacLeod, J. M.; Fleming, B. I.; Kubes, G. J.; Bolker, H. I. The strengths of kraft-AQ [anthraquinone] and soda-AQ pulps: bleachable-grade pulps [of softwoods]. TAPPI,Technical Association of the Pulp and Paper Industry, 1980, USA.

- Sixta, H.; Schild, G. A new generation kraft process. Lenzinger Berichte 2009, 87(1), 26–37. [Google Scholar]

- Behin, J.; Mikaniki, F.; Fadaei, Z. Dissolving pulp (alpha-cellulose) from corn stalk by kraft process. Iranian Journal of Chemical Engineering 2008, 5 (3): 14-28.

- Sixta, H. Handbook of pulp, Wiley-VCH, Verlag GMbH and Co, KGaA, Weinheim, 2006.

- Chen, C.; Duan, C.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Ma, X.; Zheng, L.; Stavik, J.; Ni, Y. Cellulose (dissolving pulp) manufacturing processes and properties: A mini-review. BioResources 2016, 11(2), 5553–5564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wertz, J.L.; Bédué, O.; Mercier, J.P. Swelling and Dissolution of Cellulose; in Cellulose Science and Technology. EPFLPress, Lausana, Suiza, 2010; pag. 62.

- Oberlerchner, J. T.; Rosenau, T.; Potthast, A. Overview of methods for the direct molar mass determination of cellulose. Molecules 2015, 20(6), 10313–10341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck-Candanedo S.; Roman M.; Gray D.G.Effect of reaction conditions on the properties and behavior of wood cellulose nanocrystal suspensions. Biomacromolecules 2005, 6:1048-1054.

- Lima M. M. D.; Borsali R. Rodlike cellulose microcrystals: structure, properties, and applications. Macromol. Rapid Commun 2004. 25:771–787.

- Schulz B., P.C. , Leslie A., A.; Rubio, E. Espectroscopia de infrarrojo. Ed. University of Guadalajara, Mexico,1989.

- Katsumoto, Y. , Tanaka, T., & Ozaki, Y. (2005). Molecular Interpretation for the Solvation of Poly (acrylamide) s. I. Solvent-Dependent Changes in the CO Stretching Band Region of Poly (N, N-dialkylacrylamide) s. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 109(44), 20690-20696. [CrossRef]

- Murugan, R.; Mohan, S.; Bigotto, A. FTIR and polarised Raman spectra of acrylamide and polyacrylamide. Journal of the Korean Physical Society 1998, 32(4), 505. [Google Scholar]

- Hirose, K.; Ihashi, Y.; Taguchi, S.; Yoshizawa, M. Infrared Spectra of Polymethylenebisacrylamide. Nippon Kagaku Kaishi 1966, 69, 240–244. [Google Scholar]

- Magalhães, A. S. G.; Almeida N., M. P.; Bezerra, M. N.; Ricardo, N. M.; Feitosa, J. Application of FTIR in the determination of acrylate content in poly (sodium acrylate-co-acrylamide) superabsorbent hydrogels. Química Nova 2012, 35, 1464-1467.

- Yu, H.Y.; Qin, Z.Y.; Liu, L.; Yang, X.G.; Zhou, Y.; Yao, J.M. Comparison of the reinforcing effects for cellulose nanocrystals obtained by sulfuric and hydrochloric acid hydrolysis on the mechanical and thermal properties of bacterial polyester. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2013, 87, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, B.; Bundjali, B.; Arcana, I.M. Isolation of Cellulose Nanocrystals from Bacterial Cellulose Produced from Pineapple Peel Waste Juice as Culture Medium. Procedia Chem. 2015, 16, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, H.J.; Trujillo, H.A.; Arias, G.; Pérez, J.; Delgado, E. Espectroscopia Atr-Ftir De Celulosa: Aspecto Instrumental Y Tratamiento Matemático De Espectros. e-Gnosis 2010, 8, 1–13.

- Orozco-Guareño, E.; Hernández, S. L.; Gómez-Salazar, S.; Mendizábal, E.; Katime, I. Estudio del hinchamiento de hidrogeles acrílicos terpoliméricos en agua y en soluciones acuosas de ión plumboso. Revista Mexicana de Ingeniería Química 2011, 10(3), 465-470.

- Nesrinne, S.; Djamel, A. Synthesis, characterization and rheological behavior of pH sensitive poly (acrylamide-co-acrylic acid) hydrogels. Arabian Journal of Chemistry 2017, 10(4), 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Zhu, X.; Gauthier, D.E.; An, X.; Cheng, D.; Ni, Y.; Yin, L. Development of poly (acrylic acid)/nanofibrillated cellulose superabsorbent composites by ultraviolet light induced polymerization. Cellulose 2015, 22, 2499–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schott, H. Swelling kinetics of polymers. Journal of Macromolecular Sciencie, Part B 1992, 31(1), 1–9. Retrieved from http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/00222349208215453?needAccess=true.

- Zhou, C.; Wu, Q.; Yue, Y.; Zhang, Q. Application of rod-shaped cellulose nanocrystals in polyacrylamide hydrogels. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 2011, 353(1), 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, L.; Rosli, N. A.; Ahmad, I.; Mat, A.; Amin, M. Synthesis and swelling behavior of pH-sensitive semi-IPN superabsorbent hydrogels based on poly(acrylic acid) reinforced with cellulose nanocrystals. Nanomaterials 2017, 7(12), 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliasov, L.; Shibaev, A.; Panova, I.; Kushchev, P.; Philippova, O.; Yaroslavov, A. Weakly Cross-Linked Anionic Copolymers: Kinetics of Swelling and Water-Retaining Properties of Hydrogels. Polymers 2023, 15(15), 3244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, R.; Shekhar, S. Effect of Crosslinking on Thermodynamics Interactions and Network Parameters of Terpolymeric Hydrogels. Journal of Macromolecular Science, Part B 2023, 62(12), 689-717.

- Scallan, A. M. The effect of acidic groups on the swelling of pulps: a review. Tappi journal 1983, 66(11), 73–75. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, N. I. U.S. Patent No. 4,233,329. Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, 1980.

- Işık, B. Swelling Behavior and Determination of diffusion characteristics of acrylamide–acrylic acid hydrogels. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2003, 91(2), 1289–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Dong, X.; Yao, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Jiang, Z.; Qiu, D. Preparation and Characterization of Nanocomposite Hydrogels Based on Self-Assembling Collagen and Cellulose Nanocrystals. Polymers 2023, 15(5), 1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, R. S. H.; Ashton, M.; Dodou, K. Effect of crosslinking agent concentration on the properties of unmedicated hydrogels. Pharmaceutics 2015, 7(3), 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, M. Z. Effect of crosslinker type on the properties of surface-crosslinked poly (sodium acrylate) superabsorbents. Advanced Materials Research 2014, 936, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anseth, K. S.; Bowman, C. N.; Brannon-Peppas, L. Mechanical properties of hydrogels and their experimental determination. Biomaterials 1996, 17(17), 1647–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noteborn, W. E.; Zwagerman, D. N.; Talens, V. S.; Maity, C.; van der Mee, L.; Poolman, J. M.; Mytnyk, S.; van Esch, J.H.; Kros, A.; Eelkema, R.; Kieltyka, R. E. Crosslinker-Induced Effects on the Gelation Pathway of a Low Molecular Weight Hydrogel. Advanced Materials 2017, 29(12), 1603769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, T. P.; Huglin, M. B. Effect of crosslinker on properties of copolymeric N-vinyl-2-pyrrolidone/methyl methacrylate hydrogels and organogels. Die Makromolekulare Chemie 1990, 191(2), 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanpichai, S.; Oksman, K. Cross-linked nanocomposite hydrogels based on cellulose nanocrystals and PVA: Mechanical properties and creep recovery. Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing 2016, 88, 226-233.

- Keyvani, P.; Nyamayaro, K.; Mehrkhodavandi, P.; Hatzikiriakos, S. G. Cationic and anionic cellulose nanocrystalline (CNC) hydrogels: A rheological study. Physics of Fluids 2021, 33(4).

- Lopez L., M.C. Obtención y caracterización de nanocristales de celulosa, a partir de Huizache, producidos mediante diversas condiciones de hidrolisis acida controlada. Master's thesis. University of Guadalajara, 2017.

- Morales R., J. P. Estudios sobre el comportamiento de la madera de huizache (Acacia farnesiana) en procesos de pulpeo, enfocados hacia la producción de α-celulosa para derivados. Chemical Engineering Masters thesis, . University of Guadalajara, Mexico, 2013.

- Muñoz R., M. G. Blanqueo de pulpas de huizache (Acacia farnesiana) para la obtención de α-celulosa para derivados. Chemical Engineering Masters thesis. University of Guadalajara, Mexico, 2013.

- TAPPI T236 om-22. Kappa Number of Pulp. STANDARD by Technical Association of the Pulp and Paper Industry, Tappi Press, Atlanta, GA, USA, 2022.

- TAPPI T230 om-19 Viscosity of Pulp (Capillary Viscometer Method). STANDARD by Technical Association of the Pulp and Paper Industry, Tappi Press, Atlanta, GA, USA, 2019.

- TAPPI T252 om-18. Brightness of pulp, paper, and paperboard (directional reflectance at 457 nm). STANDARD by Technical Association of the Pulp and Paper Industry, TAPPI Press, Atlanta, GA, USA.2018.

- TAPPI T 203 cm-22. Alpha-, Beta- and Gamma-Cellulose in Pulp. STANDARD by Technical Association of the Pulp and Paper Industry, Tappi Press, Atlanta, GA, USA, 2022.

- Katime, I.; Velada, J.L.; Novoa, R.; Díaz de Apodaca, E.; Puig, J.; Mendizabal, E. Swelling Kinetics of Poly (acrylamide)/Poly (mono-n-alkyl itaconates) Hydrogels. Polym. Int. 1996, 40, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM International. D695-23. Standard Test Method for Compressive Properties of Rigid Plastics; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Raimond, B. S.; Carraher, C. E. Introducción a la química de los polímeros. Reverté SA, 1995.

- Rodriguez, F.; Cohen, F.; Ober C., K.; Archer, L. Principles of polymer systems. CRC Press, 2003.

| CNC Source | CNC ID | DH (nm | [AG] (mmol AG/Kg CNC) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Huizache | Hu-A | 142 | 334 |

| Hu-B | 89.5 | 505 | |

| Hu-C | 116 | 27 | |

| Hu-D | 219 | 216 | |

| Agave Bagasse | AB | 601 | - |

| Commercial Wood | CW | 276 | 42 (0.4 wt. %) |

|

|

| CCNC (wt. %) | 0.1 | 1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNC Type | CNMBA (wt. %) | 0.1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 1 |

| Control | 9.7 ± 1.8 | 10.5 ± 6.2 | 17.5 ± 7.2 | 9.7 ± 1.8 | 10.5 ± 6.2 | 17.5 ± 7.2 | |

| Huizache | Hu-A | 4.8 ±2.3 | 13.1 ± 5.6 | 35.3 ± 7.3 | 6.6 ± 1.5 | 21.3 ± 1.7 | 28.7 ± 12.2 |

| Hu-B | 8.8 ± 2.5 | 19.8 ± 3.6 | 36.6 ±8.7 | 13.9 ± 2.7 | 15.3 ± 4.1 | 29.1 ± 4.3 | |

| Hu-C | 9.5 ± 5.1 | 15.3 ±7.6 | 33.7 ±16.4 | 6.8 ±1.4 | 21.4 ±11.3 | 21.8 ± 4.0 | |

| Hu-D | 5.1 ±1.7 | 15.8 ±4.5 | 16.5 ±19.0 | 7.2 ± 2.3 | 20.4 ±7.6 | 29.6 ± 9.0 | |

| Agave Bagasse | 14.6 ± 8.5 | 17.4 ± 4 | |||||

| Comm. Wood | 19.8 ± 9.7 | 25.6 ±19.6 | |||||

| CCNC (wt. %) | 0.1 | 1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNC Type | CNMBA (wt. %) | 0.1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 1 |

| Control | 5.8 ±1.22 | 8.6 ±0.24 | 19.3±9.5 | 5.8 ±1.22 | 8.6 ± .24 | 19.3±9.5 | |

| Huizache | Hu-A | 5.7 ± 1.6 | 10.3±2.3 | 36 ± 30 | 9.4 ± 2.9 | 13.7 ±1.4 | 18.4 ± 1.3 |

| Hu-B | 5.9 ± 0.2 | 6.3 ± 4.3 | 17.2 ± 8.6 | 7.2 ± 1.7 | 8.8 ± 1.5 | 15.7 ± 4.4 | |

| Hu-C | 3.9 ± 0.6 | 6.9 ± 0.37 | 17.8±26.6 | 4.7 ± 0.6 | 13.1±16.4 | 17.7 ± 2.1 | |

| Hu-D | 5.9 ± 0.7 | 6.7 ± 2.9 | 9.0 ± 4.1 | 8.1 ±1.6 | 12.3 ± 1.2 | 15.2 ±5.9 | |

| Agave Bagasse | 16.1±2.3 | 23.6 ± 5.8 | |||||

| Comm. Wood | 15.27±3.3 | 11.0 ± 4.8 | |||||

| CNC Source | CNC ID | [H2SO4] | T (°C) | t (min) | Filter size (μm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Huizache | Hu-A | 62.5 | 50 | 55 | 1.6 |

| Hu-B | 65 | 55 | 65 | 1.6 | |

| Hu-C | 60 | 55 | 64 | 6 | |

| Hu-D | 60 | 55 | 45 | 1.6 | |

| Agave Bagasse | AB | 63.5 | 44 | 130 | - |

| Comm. Wood | CW | 64 | - | - | - |

| CNC type | [NMBA] (wt. %) | [CNC] (wt. %) |

|---|---|---|

| Control Sample | 0.1, 0.5 and 1 | 0 |

| Hu-A | 0.1, 0.5 and 1 | 0.1 and 1 |

| Hu-B | 0.1, 0.5 and 1 | 0.1 and 1 |

| Hu-C | 0.1, 0.5 and 1 | 0.1 and 1 |

| Hu-D | 0.1, 0.5 and 1 | 0.1 and 1 |

| AB | 0.5 | 0.1 and 1 |

| CW | 0.5 | 0.1 and 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).