Submitted:

27 October 2024

Posted:

28 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

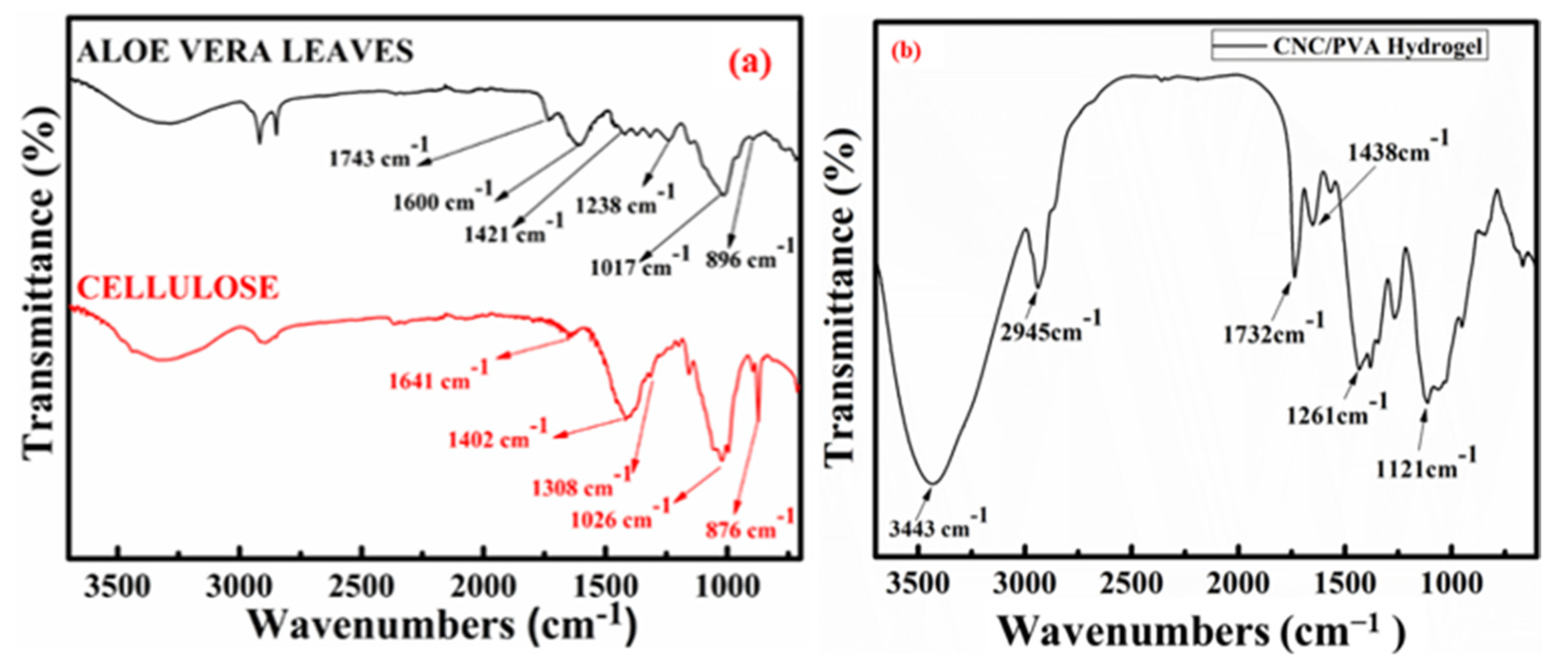

2.1. FT-IR Spectrum

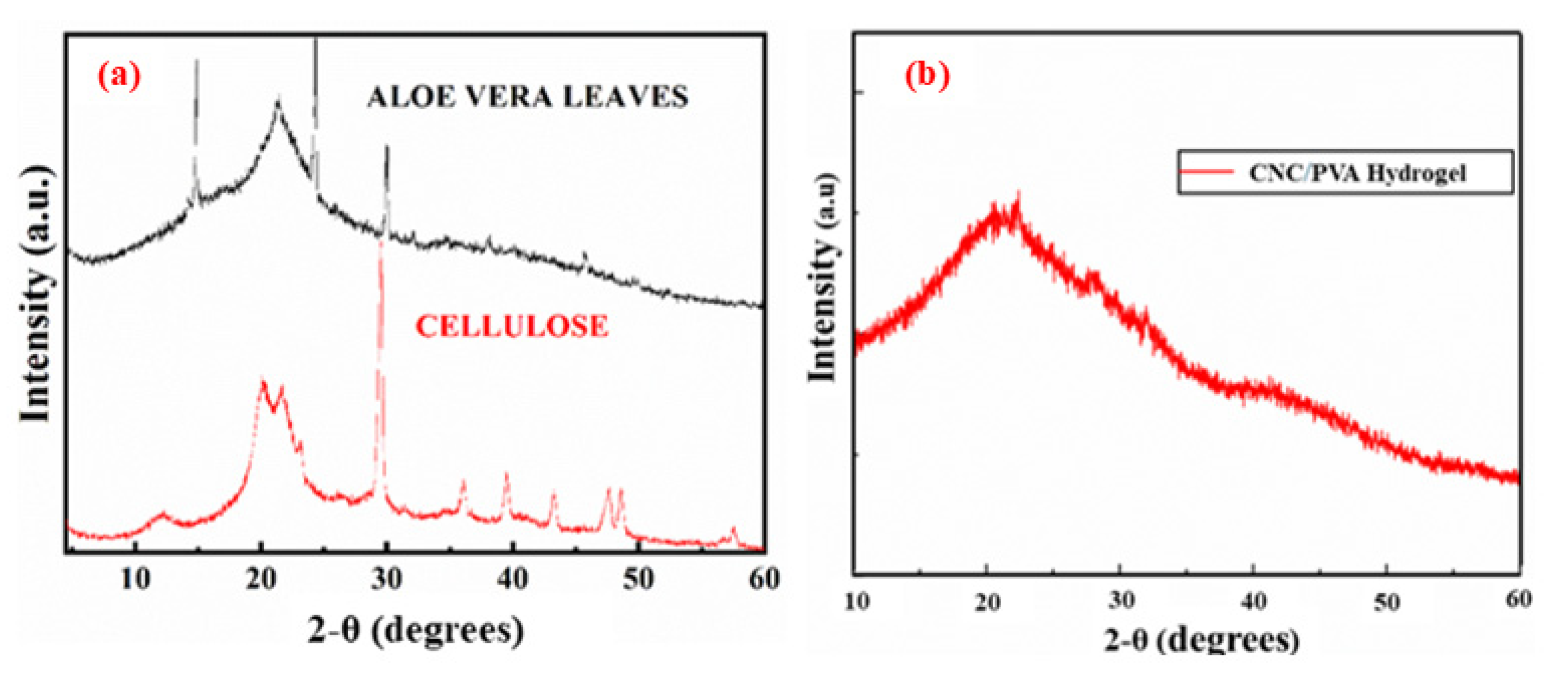

2.2. XRD Analysis

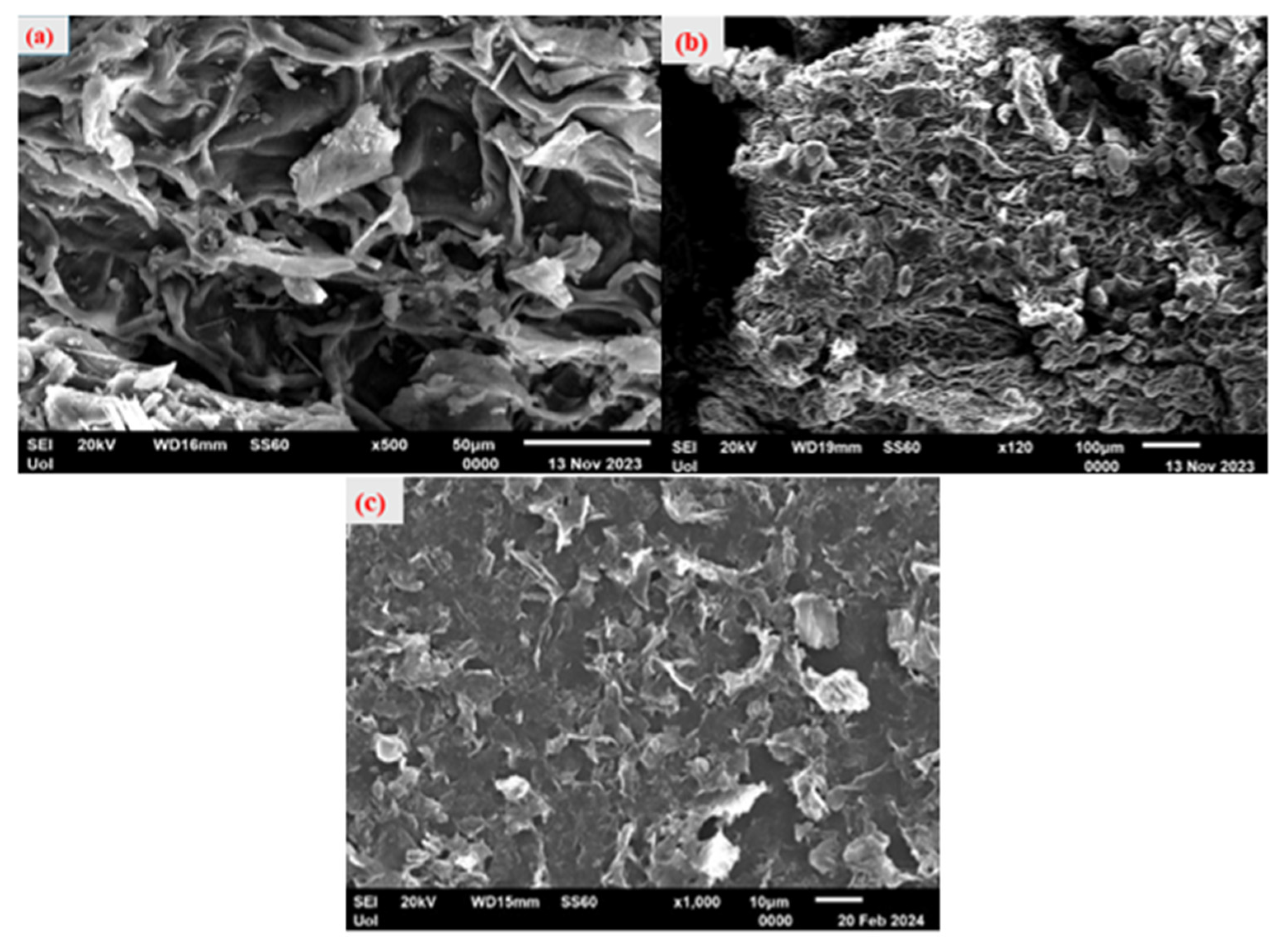

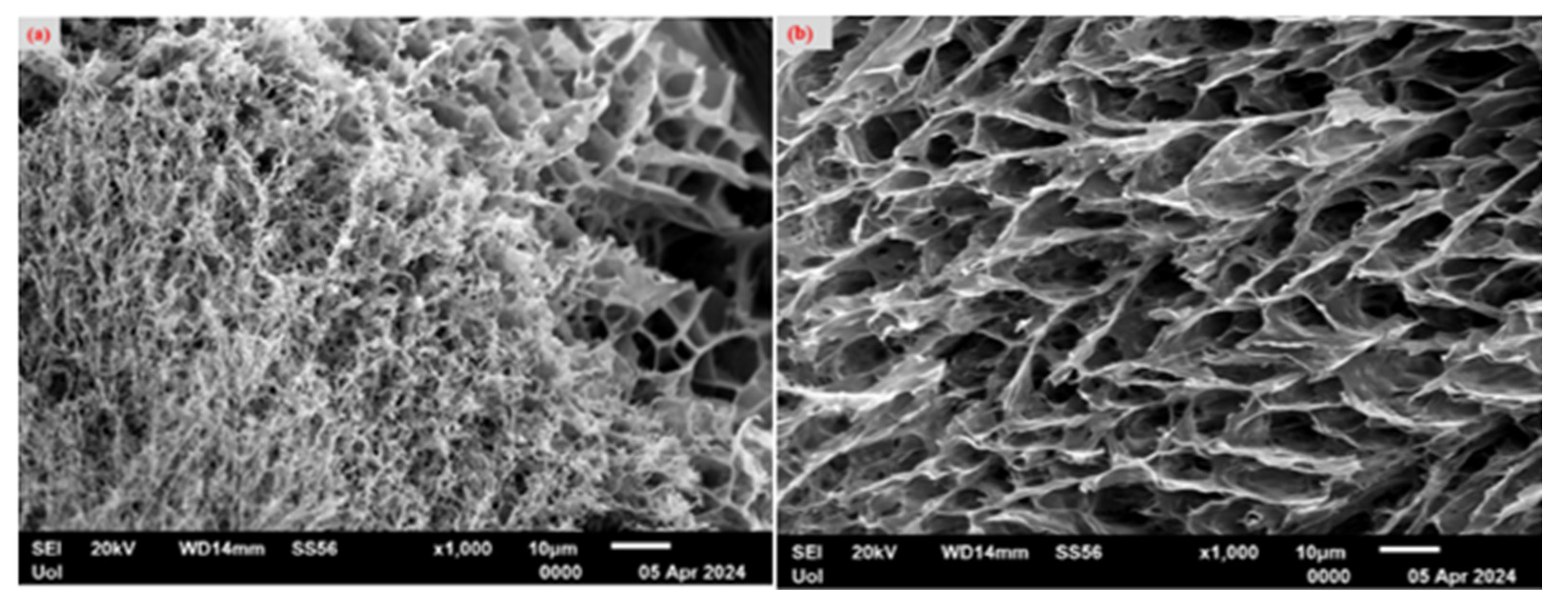

2.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

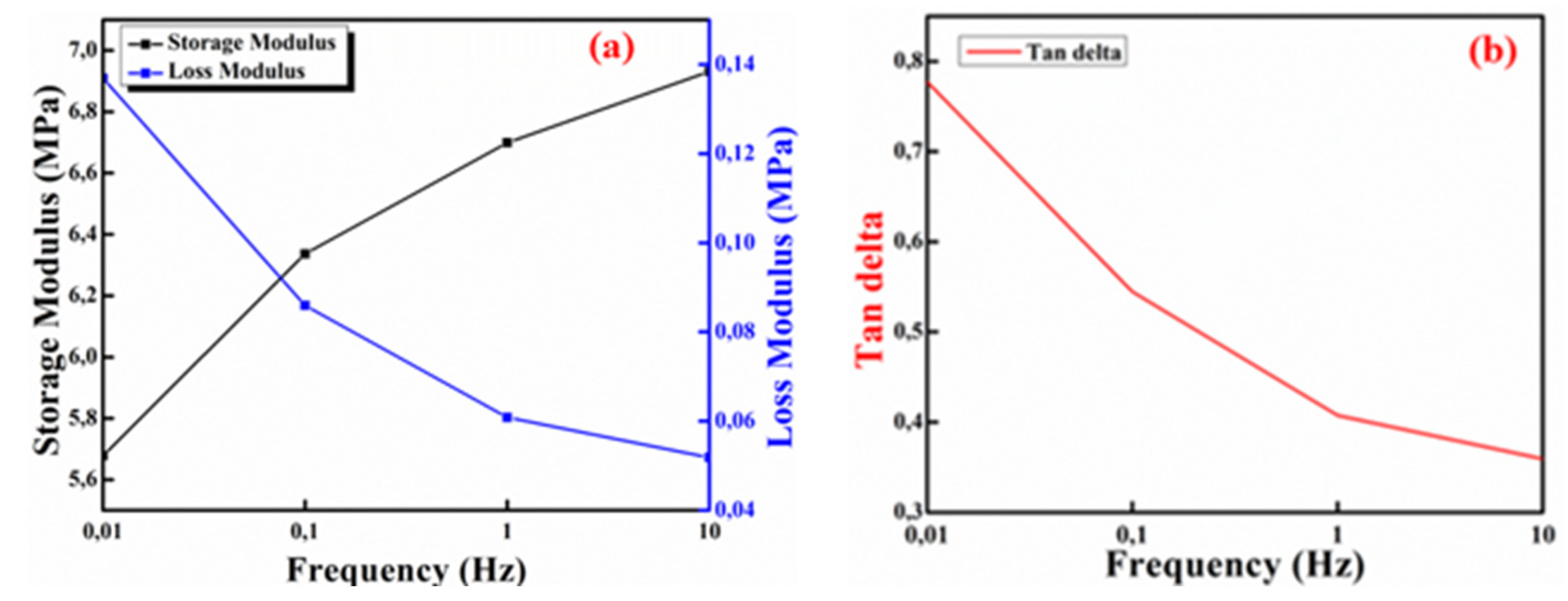

2.4. Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA)

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

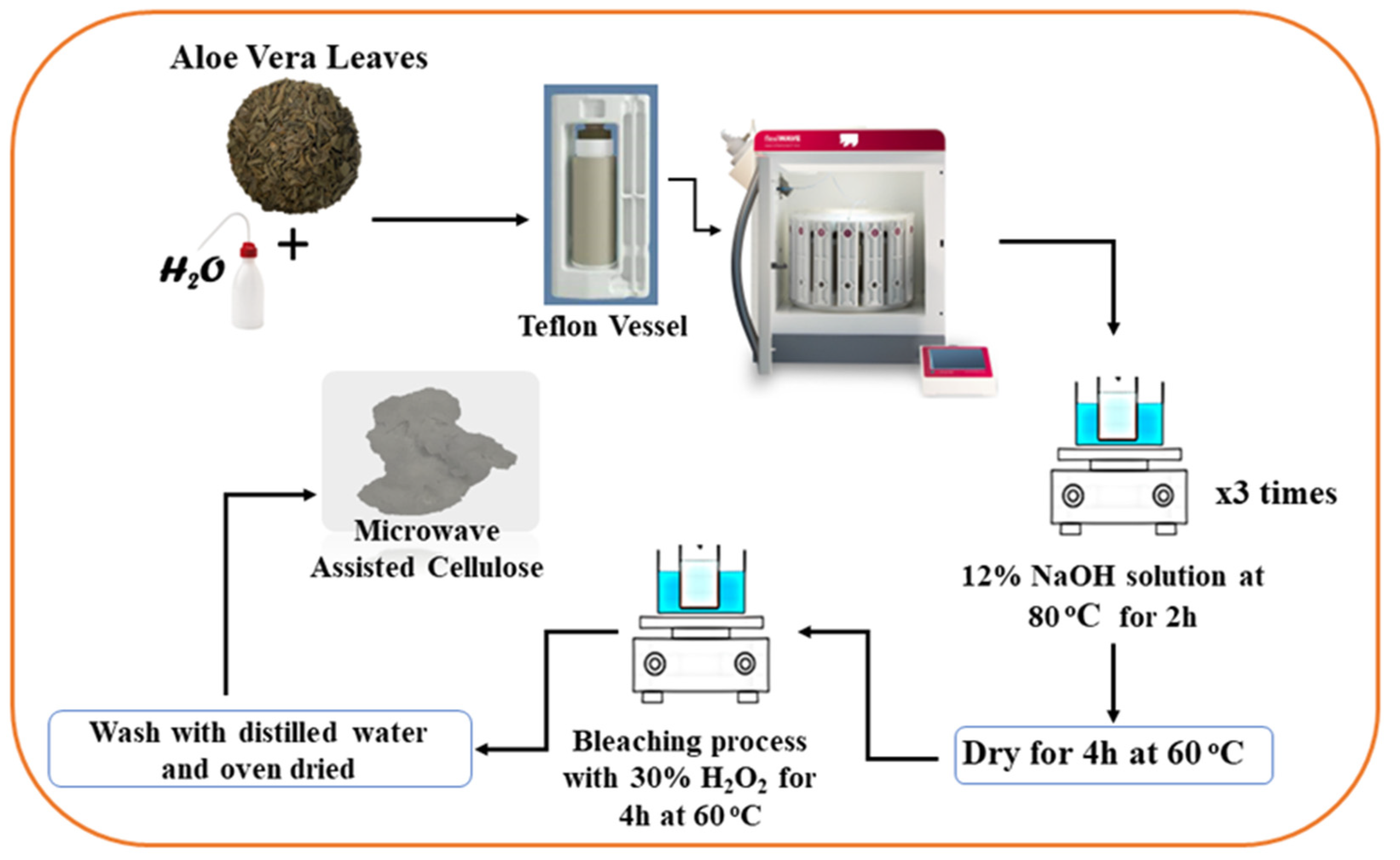

3.2. Cellulose Extraction

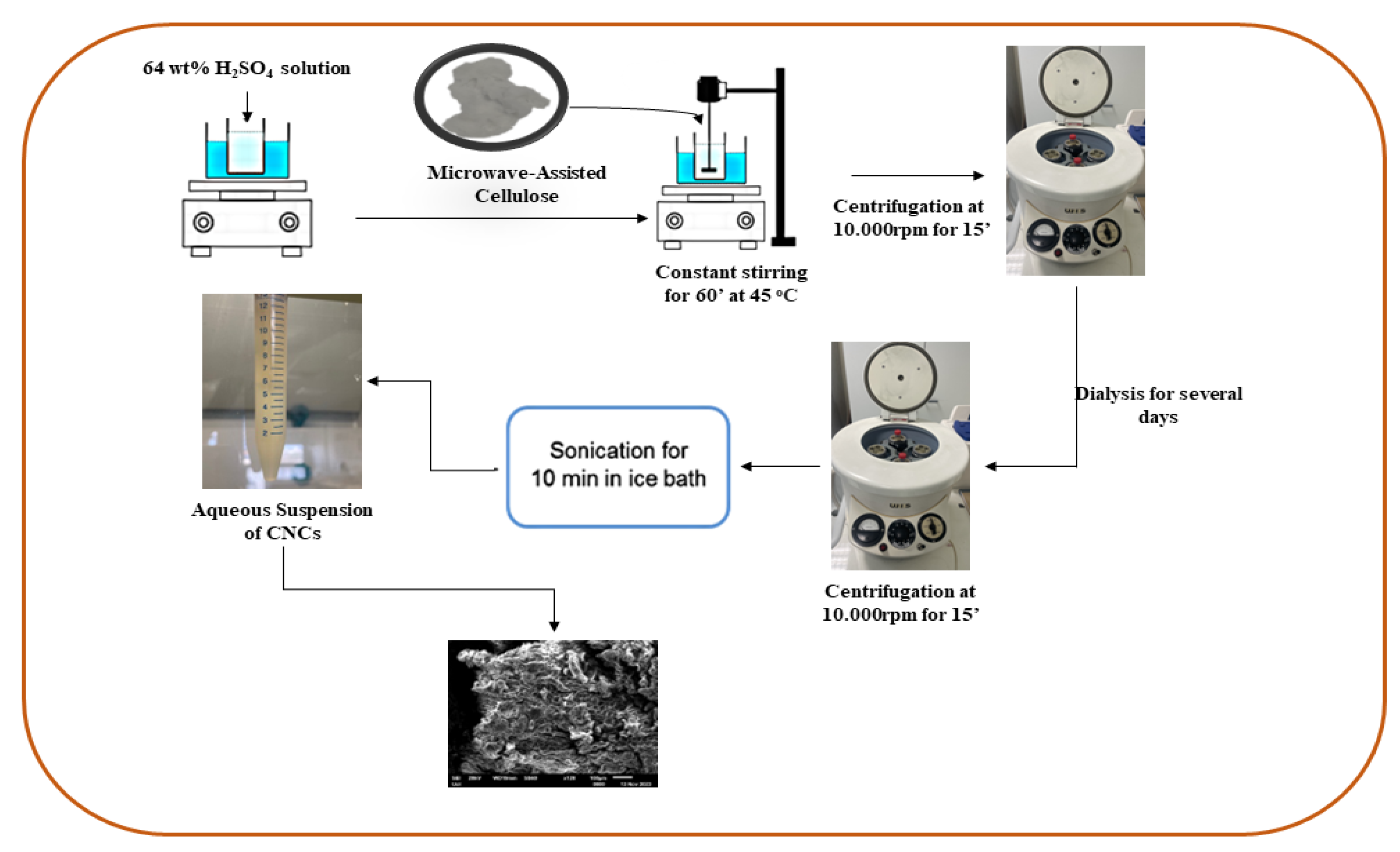

3.3. Cellulose Nanocrystals Isolation

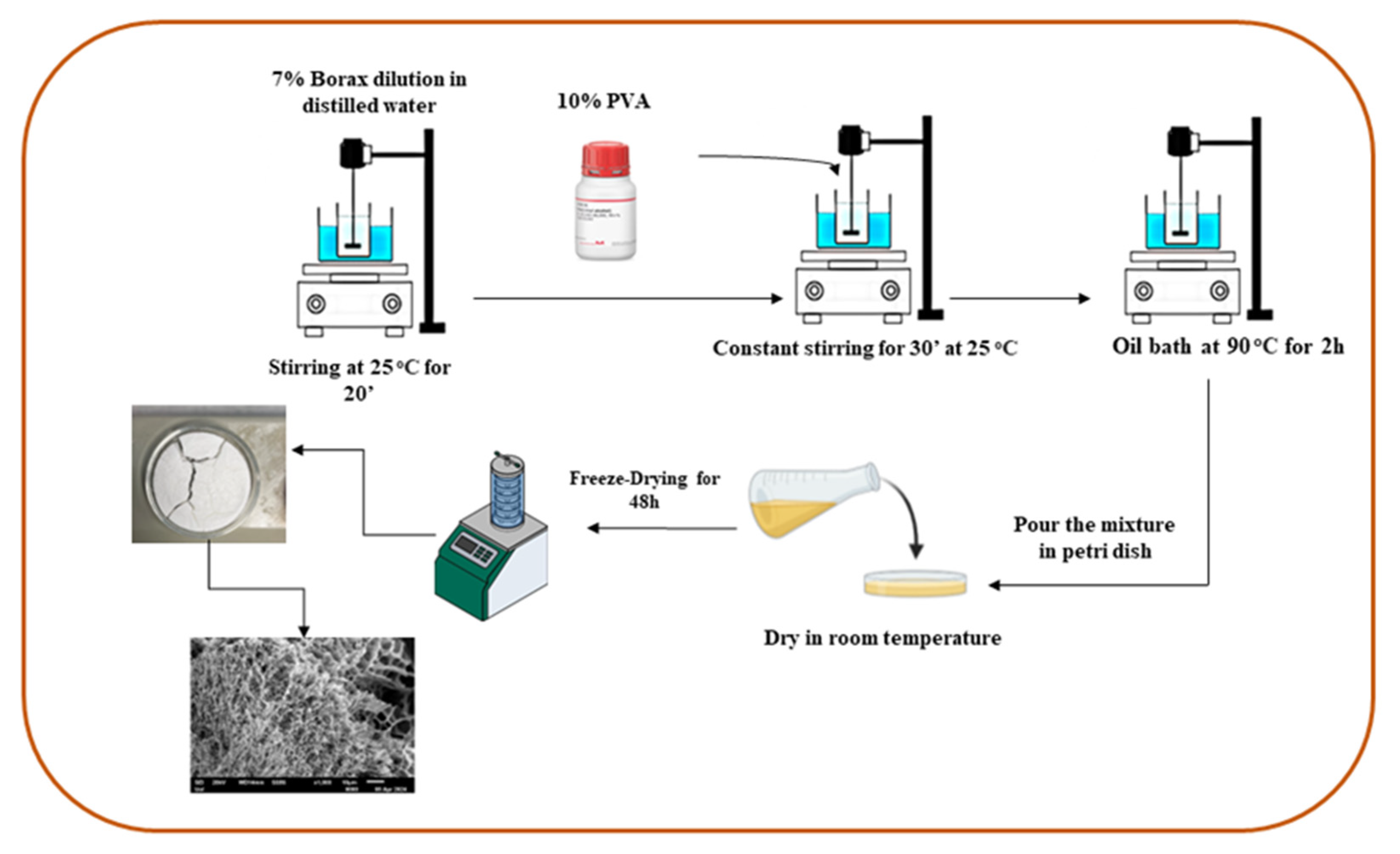

3.4. PVA/CNC Hydrogel Preparation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Szymańska-Chargot, M., et al., Isolation and Characterization of Cellulose from Different Fruit and Vegetable Pomaces. Polymers (Basel), 2017. 9(10). [CrossRef]

- Abraham, E., et al., Environmental friendly method for the extraction of coir fibre and isolation of nanofibre. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2013. 92(2): p. 1477-1483. [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, C. and D. Rosa, Extraction of cellulose nanowhiskers: natural fibers source, methodology and application. 2016. p. 232-242.

- Brinchi, L., et al., Production of nanocrystalline cellulose from lignocellulosic biomass: Technology and applications. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2013. 94(1): p. 154-169. [CrossRef]

- Nagarajan, K.J., A.N. Balaji, and N.R. Ramanujam, Extraction of cellulose nanofibers from cocos nucifera var aurantiaca peduncle by ball milling combined with chemical treatment. Carbohydr Polym, 2019. 212: p. 312-322. [CrossRef]

- Chang, C., et al., Structure and Properties of Cellulose Nanocrystals. 2019. p. 21-52.

- Habibi, Y., L.A. Lucia, and O.J. Rojas, Cellulose Nanocrystals: Chemistry, Self-Assembly, and Applications. Chemical Reviews, 2010. 110(6): p. 3479-3500. [CrossRef]

- Gil-Martín, E., et al., Influence of the extraction method on the recovery of bioactive phenolic compounds from food industry by-products. Food Chem, 2022. 378: p. 131918.

- Chowdhury, Z. and S.B. Abd Hamid, Preparation and Characterization of Nanocrystalline Cellulose using Ultrasonication Combined with a Microwave-assisted Pretreatment Process. BioResources, 2016. 11: p. 3397-3415. [CrossRef]

- Valdés, A., et al., Microwave-assisted extraction of cellulose nanocrystals from almond (Prunus amygdalus) shell waste. Front Nutr, 2022. 9: p. 1071754.

- Kabir, S.M.F., et al., Cellulose-based hydrogel materials: chemistry, properties and their prospective applications. Prog Biomater, 2018. 7(3): p. 153-174. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z., et al., Bioinspired Nanocomposite Hydrogels with Highly Ordered Structures. Advanced Materials, 2017. 29(45): p. 1703045.

- Ge, G., et al., Stretchable, Transparent, and Self-Patterned Hydrogel-Based Pressure Sensor for Human Motions Detection. Advanced Functional Materials, 2018. 28(32): p. 1802576.

- Chiellini, E., et al., Biodegradation of poly (vinyl alcohol) based materials. Progress in Polymer Science, 2003. 28(6): p. 963-1014. [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiya, Y. and K. Sumi, Thermal decomposition products of poly(vinyl alcohol). Journal of Polymer Science Part A-1: Polymer Chemistry, 1969. 7(11): p. 3151-3158.

- Moud, A.A., et al., Viscoelastic properties of poly (vinyl alcohol) hydrogels with cellulose nanocrystals fabricated through sodium chloride addition: Rheological evidence of double network formation. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects, 2021. 609: p. 125577.

- Shen, X., et al., Hydrogels based on cellulose and chitin: fabrication, properties, and applications. Green Chemistry, 2016. 18(1): p. 53-75.

- Alvarez-Lorenzo, C., et al., Crosslinked ionic polysaccharides for stimuli-sensitive drug delivery. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 2013. 65(9): p. 1148-1171.

- Yang, J., et al., Cellulose Nanocrystals Mechanical Reinforcement in Composite Hydrogels with Multiple Cross-Links: Correlations between Dissipation Properties and Deformation Mechanisms. Macromolecules, 2014. 47: p. 4077–4086.

- You, J., et al., Improved Mechanical Properties and Sustained Release Behavior of Cationic Cellulose Nanocrystals Reinforeced Cationic Cellulose Injectable Hydrogels. Biomacromolecules, 2016. 17(9): p. 2839-2848.

- Berglund, L., et al., Self-Assembly of Nanocellulose Hydrogels Mimicking Bacterial Cellulose for Wound Dressing Applications. Biomacromolecules, 2023. 24(5): p. 2264-2277.

- Hebeish, A., et al., Development of cellulose nanowhisker-polyacrylamide copolymer as a highly functional precursor in the synthesis of nanometal particles for conductive textiles. Cellulose, 2014. 21(4): p. 3055-3071. [CrossRef]

- Loh, E.Y.X., et al., Development of a bacterial cellulose-based hydrogel cell carrier containing keratinocytes and fibroblasts for full-thickness wound healing. Scientific Reports, 2018. 8(1): p. 2875. [CrossRef]

- Lusiana, S., A. Srihardyastutie, and M. Masruri, Cellulose nanocrystal (CNC) produced from the sulphuric acid hydrolysis of the pine cone flower waste (Pinus merkusii Jungh Et De Vriese). Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 2019. 1374: p. 012023.

- Fardsadegh, B. and H. Jafarizadeh, Aloe vera leaf extract mediated green synthesis of selenium nanoparticles and assessment of their In vitro antimicrobial activity against spoilage fungi and pathogenic bacteria strains. Green Processing and Synthesis, 2019. 8: p. 399-407.

- El-Sakhawy, M., et al., Preparation and infrared study of cellulose based amphiphilic materials. 2018.

- Jahan, Z., M.B.K. Niazi, and Ø.W. Gregersen, Mechanical, thermal and swelling properties of cellulose nanocrystals/PVA nanocomposites membranes. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry, 2018. 57: p. 113-124.

- Putri, L.Z. and Ratnawulan, Analysis of Aloe vera Nano Powder (Aloe vera L.) using X-Ray Diffraction (XRD). Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 2023. 2582(1): p. 012029.

- Gong, J., et al., Research on cellulose nanocrystals produced from cellulose sources with various polymorphs. RSC Adv., 2017. 7: p. 33486-33493.

- Jayaramudu, T., et al., Electroactive Hydrogels Made with Polyvinyl Alcohol/Cellulose Nanocrystals. Materials, 2018. 11: p. 1615. [CrossRef]

- Tummala, G.K., Hydrogels of Poly (vinyl alcohol) and Nanocellulose for ophthalmic applications: synthesis, characterization, biocompatibility and drug delivery studies. 2018, Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis.

- Veloso, S.R.S., et al., Cellulose Nanocrystal (CNC) Gels: A Review. Gels, 2023. 9(7). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).