Submitted:

03 December 2024

Posted:

04 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples Collection

2.2. Isolation of Fungi Associated with Healthy Cocoa Fruits

2.3. Morphological and Cultural Characterization

2.4. DNA Extraction, Amplification and Sequencing

2.5. Fungal Diversity Analysis

3. Results

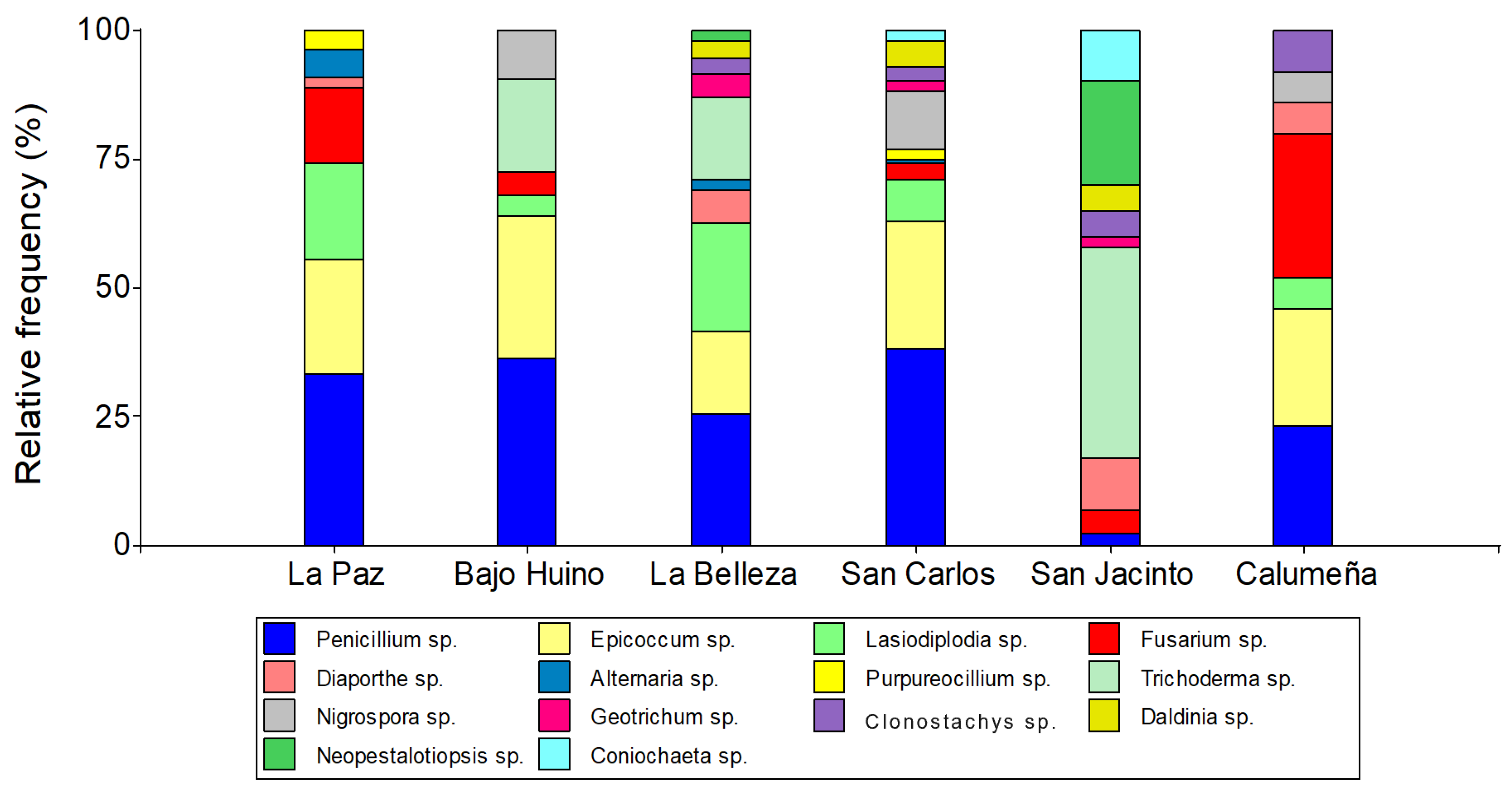

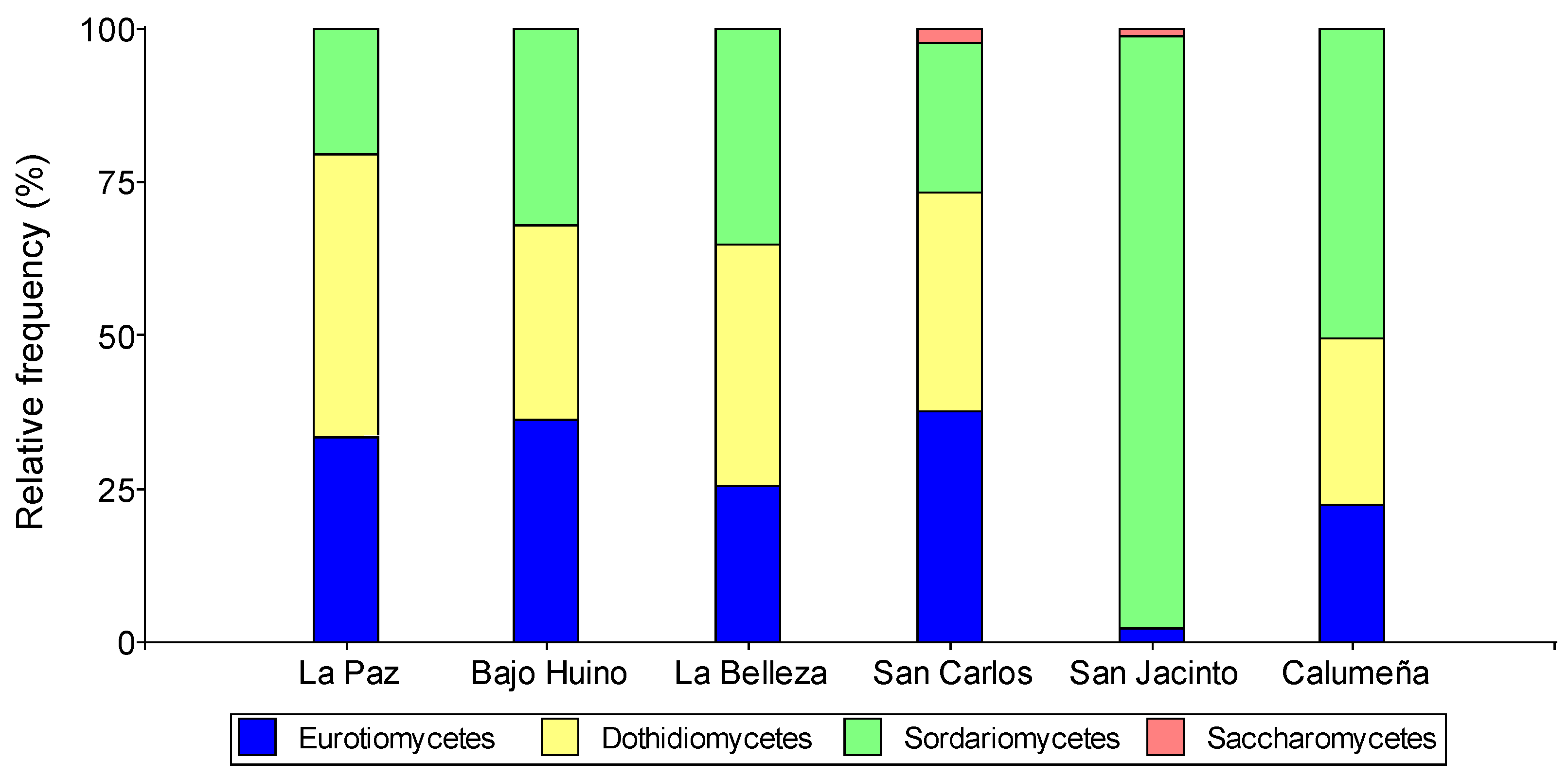

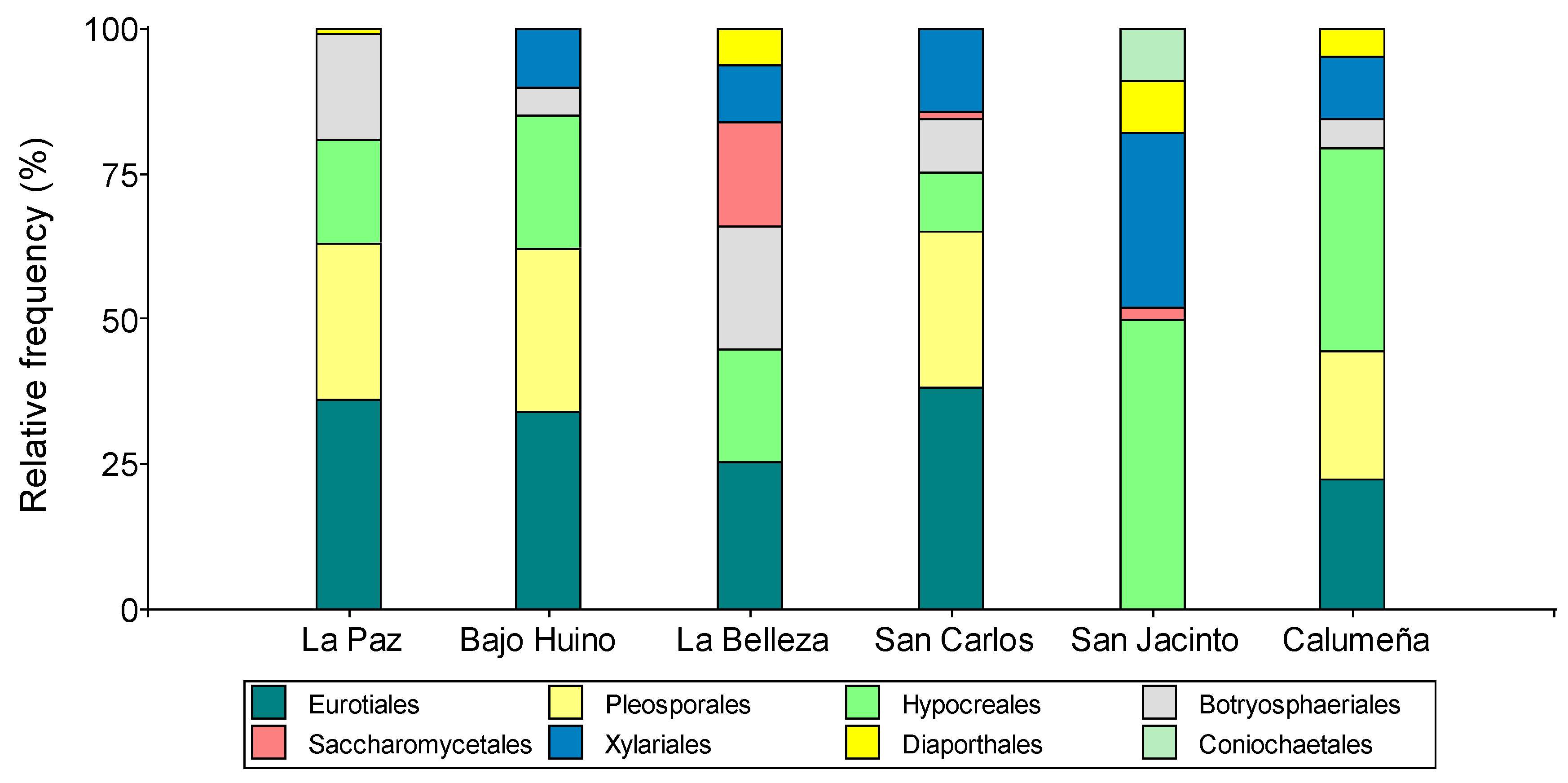

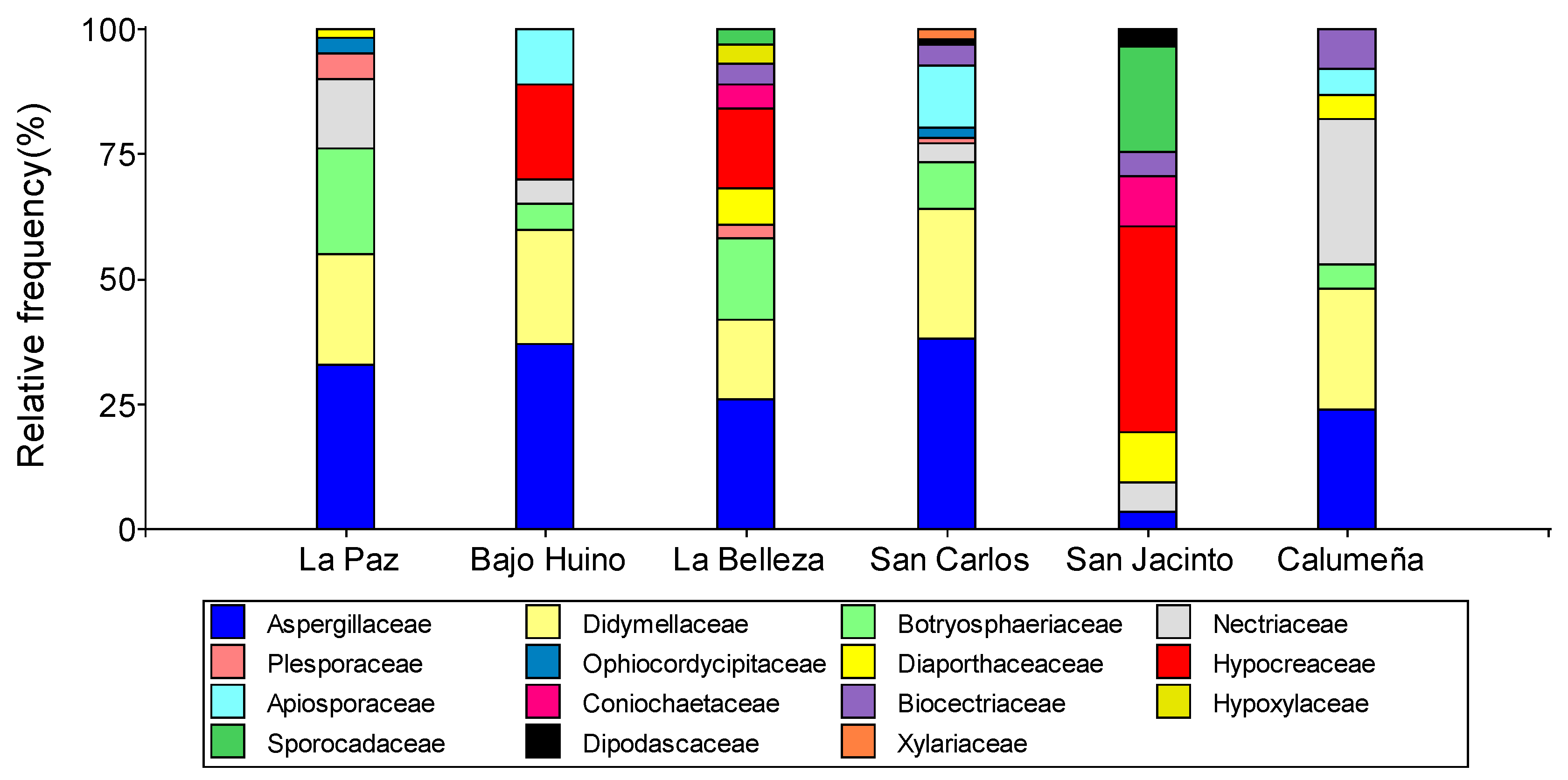

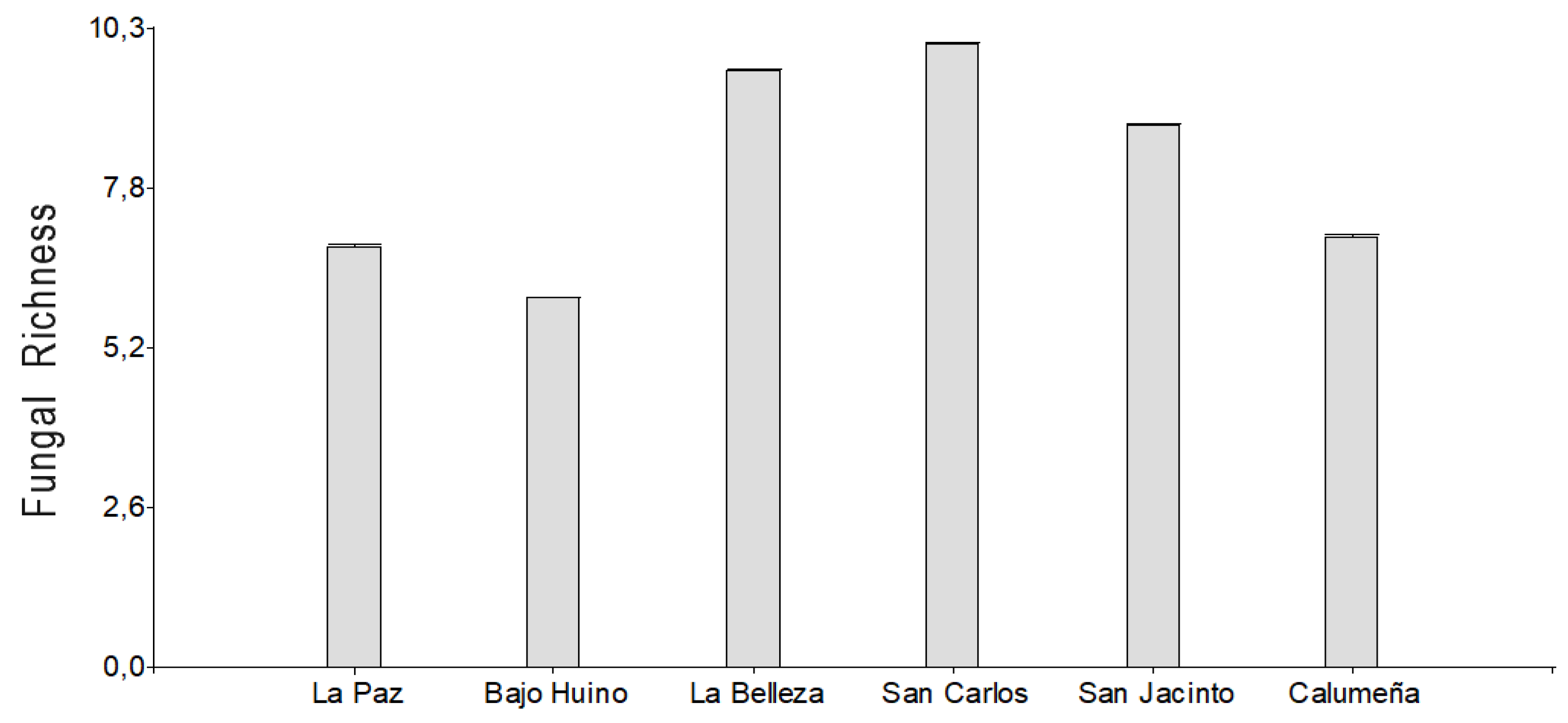

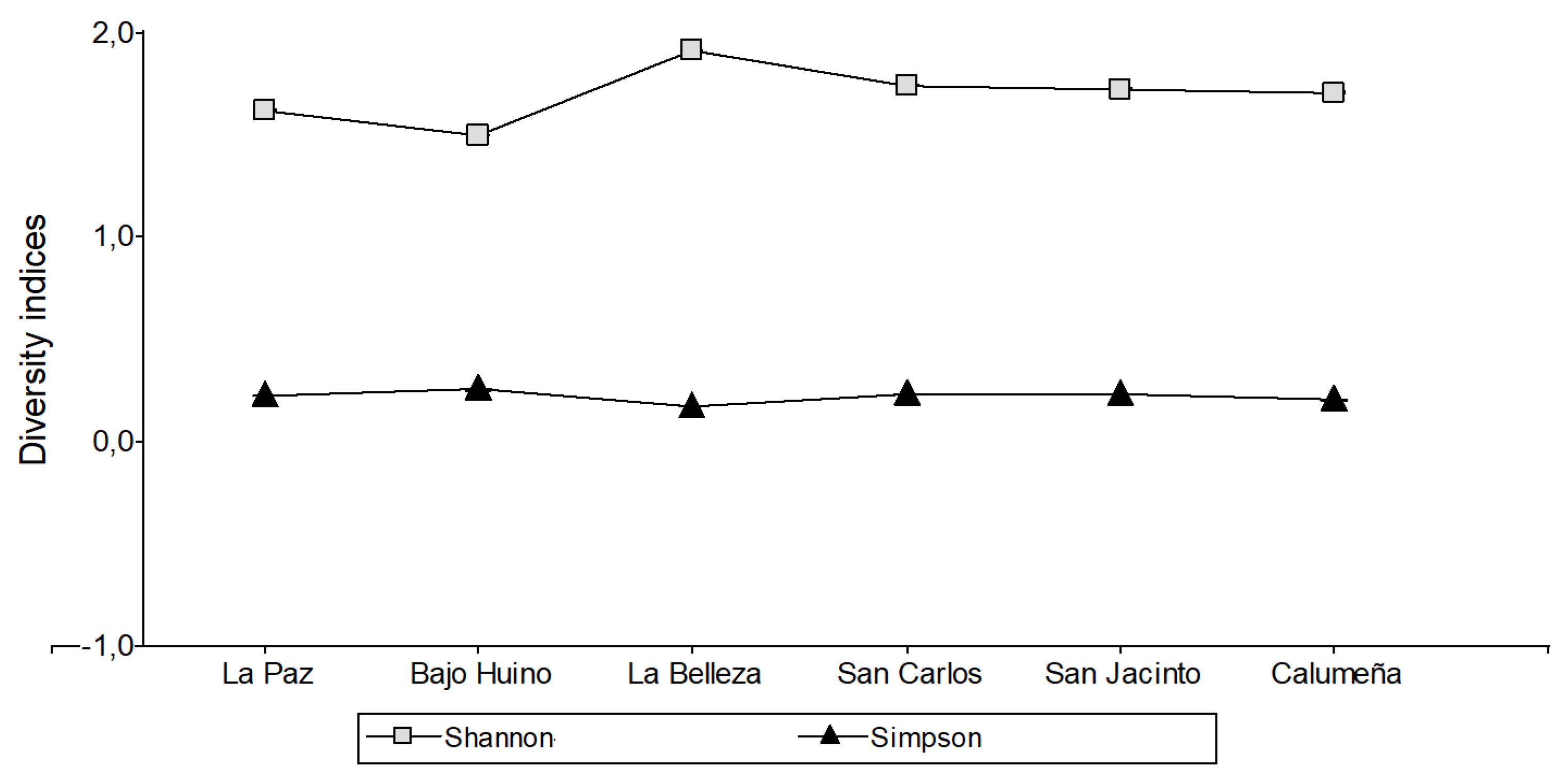

3.1. Analysis of the Diversity of Fungi Present in Cocoa Fruits

3.2. Cultural, Morphological and Molecular Characterization of Fungal Microorganisms

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alves-Júnior, M.; de Sousa, F.O.; Silva, T.F.; Albino, U.B.; Garcia, M.G.; Moreira, S.M.C. de O.; Vieira, M.R. da S. Functional and Morphological Analysis of Isolates of Phylloplane and Rhizoplane Endophytic Bacteria Interacting in Different Cocoa Production Systems in the Amazon. Current Research in Microbial Sciences 2021, 2, 100039.

- Gilbert, G.S. Evolutionary Ecology of Plant Diseases in Natural Ecosystems. Annual Review of Phytopathology 2002, 40, 13–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, A.E.; Mejía, L.C.; Kyllo, D.; Rojas, E.I.; Maynard, Z.; Robbins, N.; Herre, E.A. Fungal Endophytes Limit Pathogen Damage in a Tropical Tree. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003, 100, 15649–15654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado-Ospina, J.; Molina-Hernández, J.B.; Chaves-López, C.; Romanazzi, G.; Paparella, A. The Role of Fungi in the Cocoa Production Chain and the Challenge of Climate Change. Journal of Fungi 2021, 7, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubini, M.R.; Silva-Ribeiro, R.T.; Pomella, A.W.V.; Maki, C.S.; Araújo, W.L.; dos Santos, D.R.; Azevedo, J.L. Diversity of Endophytic Fungal Community of Cacao (Theobroma Cacao L.) and Biological Control of Crinipellis Perniciosa, Causal Agent of Witches’ Broom Disease. Int J Biol Sci 2005, 1, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berbee, M.L. The Phylogeny of Plant and Animal Pathogens in the Ascomycota. Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology 2001, 59, 165–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaithra, M.; Vanitha, S.; Ayyasami, R.; Jegadeeshwari, V.; Rajesh, V.; Hegde, V.; Apshara, E. Morphological and Molecular Characterization of Endophytic Fungi Associated with Cocoa (Theobroma Cacao L.) in India. Current Journal of Applied Science and Technology 2020, 1–8.

- Carlsson-Granér, U.; Thrall, P.H. The Spatial Distribution of Plant Populations, Disease Dynamics and Evolution of Resistance. Oikos 2002, 97, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, A.E. Understanding the Diversity of Foliar Endophytic Fungi: Progress, Challenges, and Frontiers. Fungal Biology Reviews 2007, 21, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Wu, Y.; He, Z.; Li, M.; Zhu, K.; Gao, B. Diversity and Antifungal Activity of Endophytic Fungi Associated with Camellia Oleifera. Mycobiology 2018, 46, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieber, T.N. Endophytic Fungi in Forest Trees: Are They Mutualists? Fungal Biology Reviews 2007, 21, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usuki, F.; Narisawa, K. A Mutualistic Symbiosis between a Dark Septate Endophytic Fungus, Heteroconium Chaetospira, and a Nonmycorrhizal Plant, Chinese Cabbage. Mycologia 2007, 99, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tellenbach, C.; Grünig, C.R.; Sieber, T.N. Negative Effects on Survival and Performance of Norway Spruce Seedlings Colonized by Dark Septate Root Endophytes Are Primarily Isolate-Dependent. Environ Microbiol 2011, 13, 2508–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanada, R.E.; Pomella, A.W.V.; Costa, H.S.; Bezerra, J.L.; Loguercio, L.L.; Pereira, J.O. Endophytic Fungal Diversity in Theobroma Cacao (Cacao) and T. Grandiflorum (Cupuaçu) Trees and Their Potential for Growth Promotion and Biocontrol of Black-Pod Disease Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1878614610001364 (accessed on 19 October 2023).

- Pico, J.T.; Díaz, A.E.; Vargas Tierras, Y.B.; Viera, W.F.; Caicedo V., C. P21 Evaluación de la Dispersión de Esporas de Alternaria sp. en el Cultivo de Pitahaya (Selenicereus megalanthus) en Palora.; Galápagos, EC: INIAP, Estación Experimental Central de la Amazonía, 2019, 2019; ISBN 978-9978-68-144-2.

- Pico, J.T.; Calderón Peña, E.D.; Fernández A., F.; Díaz M., A. Guía del manejo integrado de enfermedades del cultivo de cacao (Theobroma cacao L) en la amazonía Available online: http://repositorio.iniap.gob.ec/handle/41000/3752 (accessed on 29 October 2023).

- Marelli, J.-P.; Guest, D.I.; Bailey, B.A.; Evans, H.C.; Brown, J.K.; Junaid, M.; Barreto, R.W.; Lisboa, D.O.; Puig, A.S. Chocolate Under Threat from Old and New Cacao Diseases. Phytopathology® 2019, 109, 1331–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroth, G.; Läderach, P.; Martinez-Valle, A.I.; Bunn, C.; Jassogne, L. Vulnerability to Climate Change of Cocoa in West Africa: Patterns, Opportunities and Limits to Adaptation. Science of The Total Environment 2016, 556, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, C.; Navarro-Barranco, H.; Ayala-Zermeño, M.; Rosas, M.A.; Toriello, C. Obtención y caracterización de cultivos monospóricos de Metarhizium anisopliae (Hypocreales : Clavicipitaceae) para genotipificación.; México, November 7 2013; p. 5.

- Castellani, A. Further Researches on the Long Viability and Growth of Many Pathogenic Fungi and Some Bacteria in Sterile Distilled Water. Mycopathologia et Mycologia Applicata 1963, 20, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urzı̀, C.; De Leo, F. Sampling with Adhesive Tape Strips: An Easy and Rapid Method to Monitor Microbial Colonization on Monument Surfaces. Journal of Microbiological Methods 2001, 44, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.L. Safe, Low-Distortion Tape Touch Method for Fungal Slide Mounts. J Clin Microbiol 2000, 38, 4683–4684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacasa-Quisbert, F.; Loza-Murguia, M.G.; Bonifacio-Flores, A.; Vino-Nina, L.; Serrano-Canaviri, T. Comunidad de hongos filamentosos en suelos del Agroecosistema de K’iphak’iphani, Comunidad Choquenaira-Viacha. Journal of the Selva Andina Research Society 2017, 8, 2–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, G.E.; Kubicek, C.P. Trichoderma And Gliocladium. Volume 1: Basic Biology, Taxonomy and Genetics; CRC Press, 2002; ISBN 978-1-4822-9532-0.

- Chaverri, P.; Castlebury, L.A.; Overton, B.E.; Samuels, G.J. Hypocrea/Trichoderma: Species with Conidiophore Elongations and Green Conidia. Mycologia 2003, 95, 1100–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, G.F.; Druzhinina, I.; Gams, W.; Bissett, J.; Zafari, D.; Szakacs, G.; Koptchinski, A.; Prillinger, H.; Zare, R.; Kubicek, C.P. Trichoderma Brevicompactum Sp. Nov. Mycologia 2004, 96, 1059–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuels, G.J.; Lieckfeldt, E.; Nirenberg, H.I. Trichoderma Asperellum, a New Species with Warted Conidia, and Redescription of T. Viride. Sydowia 1999, 51, 71–88. [Google Scholar]

- Torres-De la Cruz, M.; Ortiz-García, C.F.; Bautista-Muñoz, C.; Ramírez-Pool, J.A.; Ávalos-Contreras, N.; Cappello-García, S.; De la Cruz-Pérez, A. Diversidad de Trichoderma En El Agroecosistema Cacao Del Estado de Tabasco, México. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 2015, 86, 947–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosero, D.M.C.; Rosales, H.R.B.; Pérez, L.A.C.; Hernández, J.P.O. Población de macrofauna en sistemas silvopastoriles dedicados a la producción lechera:análisis preliminar. La Granja 2018, 27, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar Doroteo, L.; Zárate Segura, P.B.; Villanueva Arce, R.; Yáñez Fernández, J.; Garín Aguilar, M.E.; Guadarrama Mendoza, P.C.; Valencia del Toro, G. Utilización de marcadores ITS e ISSR para la caracterización molecular de cepas híbridas de Pleurotus djamor. Rev Iberoam Micol 2018, 35, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asman, A.; Baharuddin, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Rosmana, A. Ariska Diversity of Fungal Community Associated with Cacao (Theobromae Cacao L.) Top Clones from Sulawesi, Indonesia. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 486, 012171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talontsi, F.M.; Dittrich, B.; Schüffler, A.; Sun, H.; Laatsch, H. Epicoccolides: Antimicrobial and Antifungal Polyketides from an Endophytic Fungus Epicoccum Sp. Associated with Theobroma Cacao. Eur J Org Chem 2013, 2013, 3174–3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villavicencio-Vásquez, M.; Espinoza-Lozano, R.F.; Pérez-Martínez, S.; Castillo, D.S.D. FOLIAR ENDOPHYTE FUNGI AS CANDIDATE FOR BIOCONTROL AGAINST Moniliophthora Spp. OF Theobroma Cacao (Malvaceae) IN ECUADOR. Acta Biológica Colombiana 2018, 23, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoopen, G.M.; Rees, R.; Aisa, P.; Stirrup, T.; Krauss, U. Population Dynamics of Epiphytic Mycoparasites of the Genera Clonostachys and Fusarium for the Biocontrol of Black Pod (Phytophthora Palmivora) and Moniliasis (Moniliophthora Roreri) on Cocoa (Theobroma Cacao). Mycological Research 2003, 107, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R.; J.S., K.; v, S. A Worldwide List of Endophytic Fungi with Notes on Ecology and Diversity. Mycosphere 2019, 10.

- González-Oreja, J.A. Midiendo la diversidad biológica: más allá del índice de Shannon. Acta zoológica lilloana 2012, 56, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

| Fungal isolates | Number of isolates | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Penicillium | 129 | 27.80 |

| Epicoccum | 95 | 20.47 |

| Lasiodiplodia | 47 | 10.13 |

| Trichoderma | 46 | 9.91 |

| Fusarium | 45 | 9.70 |

| Nigrospora | 25 | 5.39 |

| Clonostachys | 17 | 3.66 |

| Diaporthe | 16 | 3.45 |

| Daldinia | 11 | 2.37 |

| Neopestalotiopsis | 11 | 2.37 |

| Alternaria | 6 | 1.29 |

| Purpureocillium | 4 | 0.86 |

| Coniochaeta | 4 | 0.86 |

| Geotrichum | 2 | 0.55 |

| Not identified | 6 | 1.06 |

| Genera | Morphotype | Growth | Type of elevation | Surface | Adverse color | Reverse color |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Penicillium | M.P1 M.P2 |

Irregular Circular |

Flat Curly |

Rough smooth | Dark-green | Orange Gray |

|

Epicoccum |

M.9 M.15 M.7 M.4 M.5 M.11 |

Irregular | Filamentous Curly Curly Curly Corrugated Curly |

Rugged Corrugated Corrugated Rugged Corrugated Corrugated |

Gold-yellow Yellow Cream-white Light-beige Gold-yellow Brown |

Red-mahogany Yellow Cream-black Brown Red-mahogany Black |

| Trichoderma | M.T1 M.T2 M.T5 |

Irregular Irregular Irregular |

Efusa Curly Curly |

Concentric Concentric Concentric |

Dark-green White White |

Gold-yellow Off-white Lemon-yellow |

| Lasiodiplodia | M.1 M.2 |

Filamentous | Curly | Filamentous | Gray White |

Black Linen white |

| Fusarium | M.2, M.23 M.27 | Circular Irregular Circular |

Curly Curly Curly |

Rugged Rugged Rugged |

White Pink Yellow- white |

Black Brown and pink Yellow |

| Genera | Hyphal form | Conidia form | Conidial size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Penicillium | Septate | Globose and elipsoidal | 3.5 µm long x 3.5 µm wide |

|

Epicoccum |

Septates | Muriform | 12.5 – 15.25 µm long x 10 – 13,.5 µm wide |

| Trichoderma | Septates | Oval | 2.7 – 3.5 µm long x 2.7 - .2.8 µm wide |

| Lasiodiplodia | Septates | Oval-Subovoid and elipsoidal | 5.7 µm long x 2.68 µm wide |

| Fusarium | Septates | Half moon | 20 µm long x 5,1 µm wide |

| Morphotypes | Morphological/molecular identification | Percentage Identity (%) |

Size (pb) | Accesion | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 P2 |

Peniciillium sp. | 98.41 99.72 |

378 356 |

MK805460.1 MT606192.1 |

||

| M.9 M.15 M.7 M.4 M.5 M.11 |

Epicoccum nigrum Epicoccum sp. Epicoccum sp. Epicoccum sp. Epicoccum sp. Epicoccum sp. |

100.00 99.79 100.00 99.00 99.26 98.90 |

362 470 450 517 403 364 |

MH397098.1 MG832438.1 MG832438.1 MG832438.1 MG832438.1 MG832438.1 |

||

| M.T1 M.T2 M.T5 |

Trichoderma sp. Trichoderma sp. Trichoderma sp |

100.00 100.00 100.00 |

389 501 575 |

KJ783298.1 ON705517.1 KJ783298.1 |

||

| M.1 | Lasiodiplodia sp | 99.84 | 382 | MN249167.1 | ||

| M.22 M.23 M.27 |

Fusarium sp. Fusarium sp. Fusarium sp. |

100.00 100.00 100.00 |

450 465 514 |

MN602837.1 MT603307 MN602837.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).