Submitted:

26 November 2024

Posted:

27 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

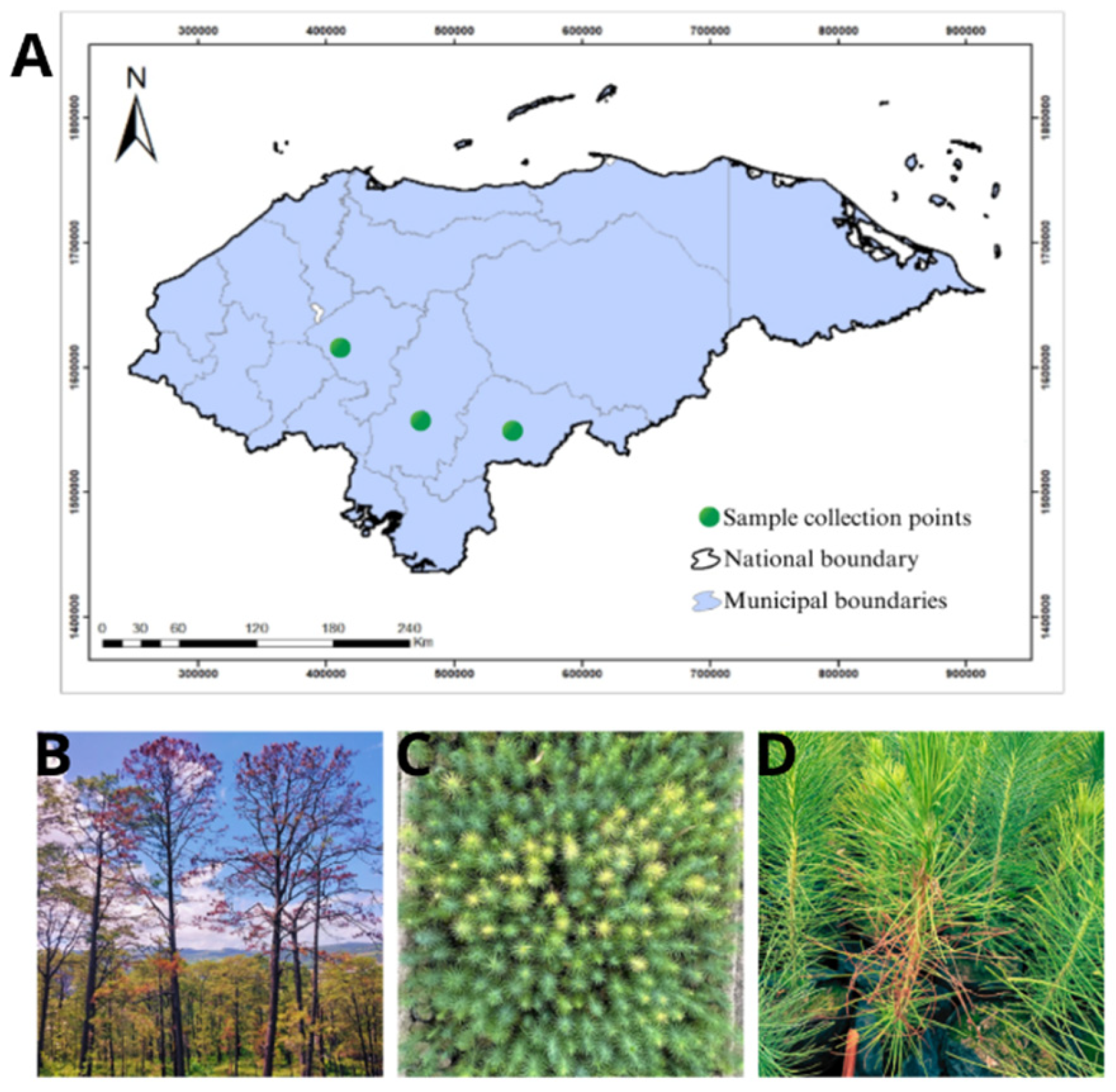

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. DNA Extraction

2.3. Molecular Identification

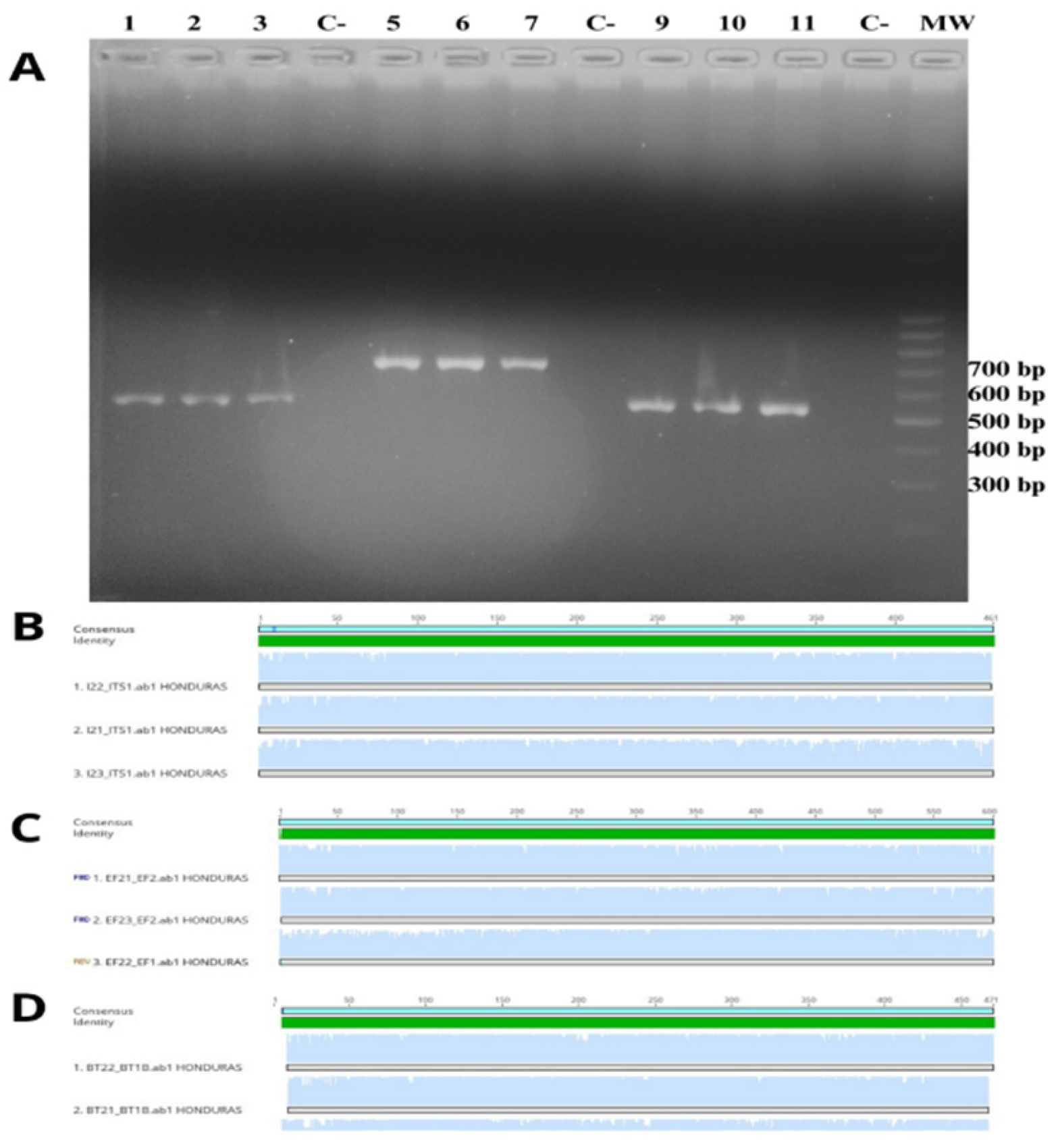

2.3.1. Amplification of ITS Regions

2.3.2. Amplification of the Elongation Factor 1 Alpha

2.3.3. Amplification of Beta Tubulin

2.4. Sequencing

3. Results

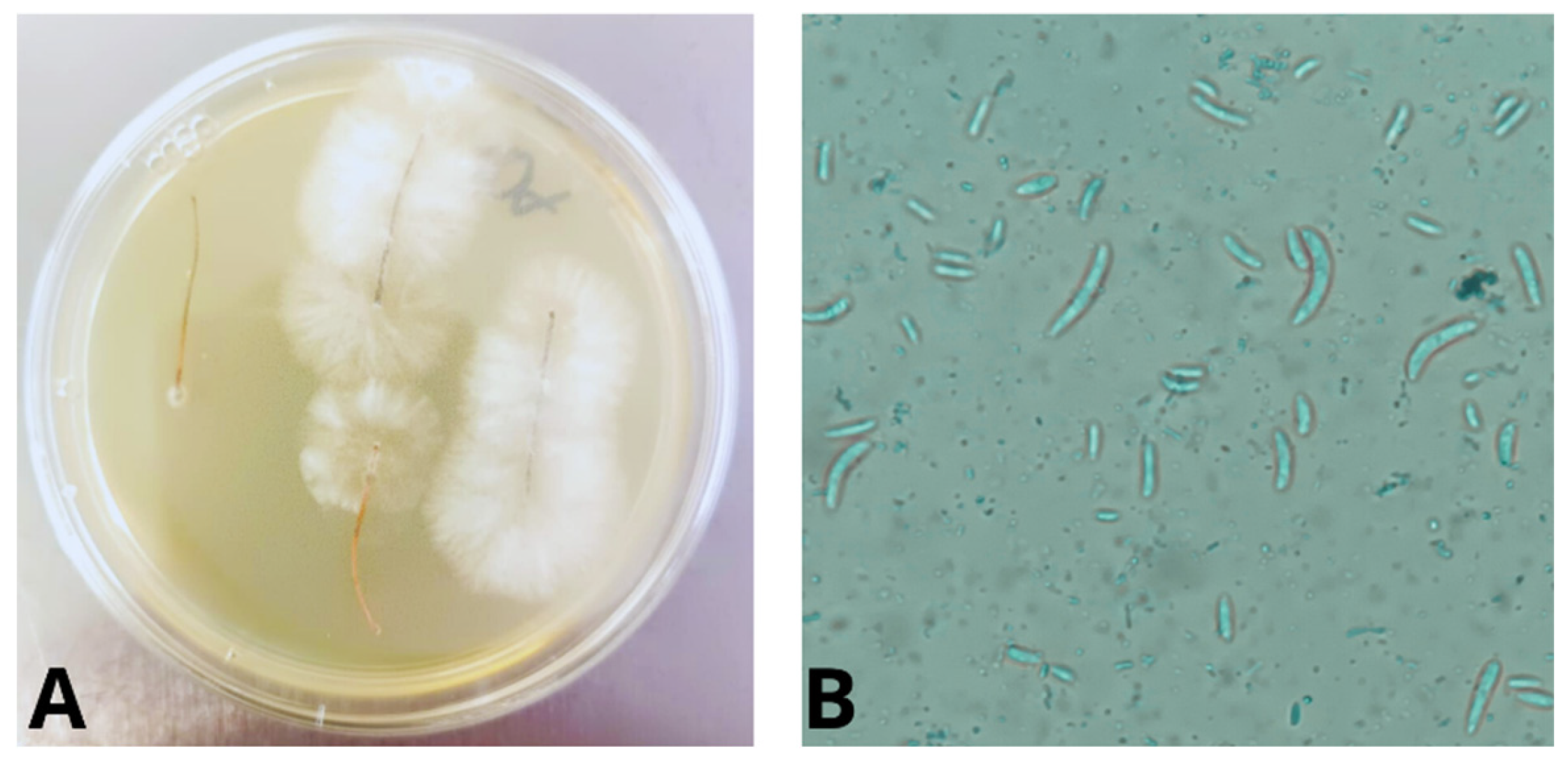

3.1. Isolation and Phenotypic Identification

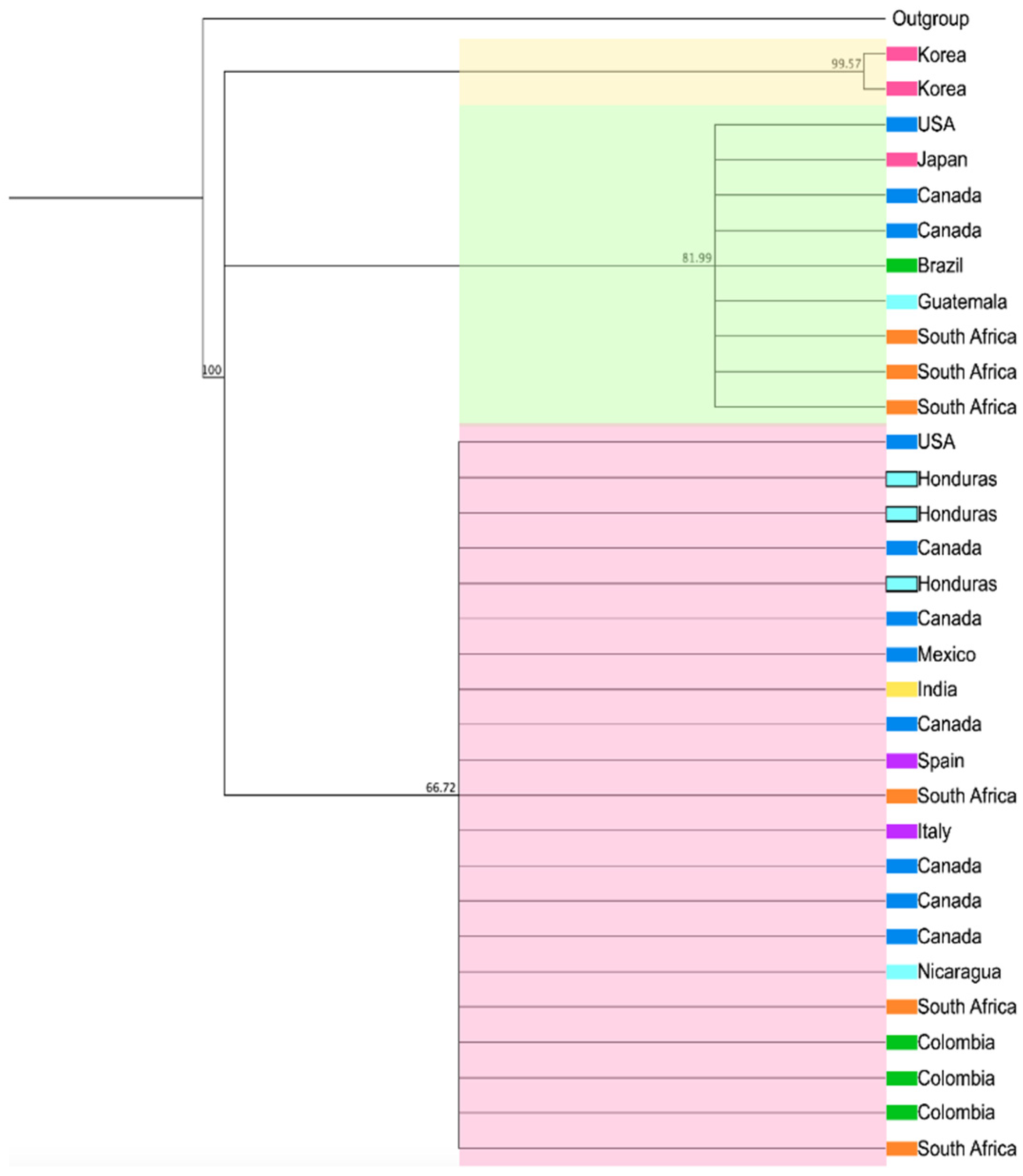

3.2. Molecular Identification of the Isolates

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Burley, J.; Barnes, R.D. TROPICAL ECOSYSTEMS | Tropical Pine Ecosystems and Genetic Resources. In Encyclopedia of Forest Sciences; Burley, J., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, 2004; pp. 1728–1740. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations FAO. El estado de los bosques del mundo 2020, Los bosques, la biodiversidad y las personas, Roma. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, I.; Mackey, B.; McNulty, S.; Mosseler, A. Forest resilience, biodiversity, and climate change. In Proceedings of the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, Montreal. Technical Series no. 43. 1-67., 2009; pp. 1-67.

- Küçüker, D.; Baskent, E. State of stone pine (Pinus pinea) forests in Turkey and their economic importance for rural development. Mediterranean pine nuts from forests and plantations 2017, 122, 111–117. [Google Scholar]

- Moctezuma López, G.; Flores, A. Economic importance of pine (Pinus spp.) as a natural resource in Mexico. Revista mexicana de ciencias forestales 2020, 11, 161–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, J. Regeneración Natural: Una revisión de los aspectos ecológicos en el bosque tropical de montaña del sur del Ecuador. Bosques Latitud Cero 2017, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Gea-Izquierdo, G.; Férriz, M.; García-Garrido, S.; Aguín, O.; Elvira-Recuenco, M.; Hernandez-Escribano, L.; Martin-Benito, D.; Raposo, R. Synergistic abiotic and biotic stressors explain widespread decline of Pinus pinaster in a mixed forest. Science of the Total Environment 2019, 685, 963–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahlali, R.; Ezrari, S.; Radouane, N.; Kenfaoui, J.; Esmaeel, Q.; El Hamss, H.; Belabess, Z.; Barka, E.A. Biological Control of Plant Pathogens: A Global Perspective. Microorganisms 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dussi, M.C.; Flores, L.B. Visión multidimensional de la agroecología como estrategia ante el cambio climático. Inter disciplina 2018, 6, 129–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armenteras, D.; González, T.M.; Vargas Ríos, O.; Meza Elizalde, M.C.; Oliveras, I. Incendios en ecosistemas del norte de Suramérica: avances en la ecología del fuego tropical en Colombia, Ecuador y Perú. Caldasia 2020, 42, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callan, B. Introduction to forest diseases. 2001.

- Ghelardini, L.; Pepori, A.L.; Luchi, N.; Capretti, P.; Santini, A. Drivers of emerging fungal diseases of forest trees. Forest Ecology and Management 2016, 381, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomdola, D.; Bhunjun, C.; Hyde, K.; Jeewon, R.; Pem, D.; Jayawardena, R. Ten important forest fungal pathogens: a review on their emergence and biology. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Rashmi, M.; Kushveer, J.; Sarma, V. A worldwide list of endophytic fungi with notes on ecology and diversity. Mycosphere 2019, 10, 798–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Ren, L.; Li, C.; Gao, C.; Liu, X.; Wang, M.; Luo, Y. Effects of endophytic fungi diversity in different coniferous species on the colonization of Sirex noctilio (Hymenoptera: Siricidae). Scientific reports 2019, 9, 5077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendgen, K.; Hahn, M.; Deising, H. Morphogenesis and mechanisms of penetration by plant pathogenic fungi. Annual review of phytopathology 1996, 34, 367–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayawardena, R.S.; Hyde, K.D.; de Farias, A.R.G.; Bhunjun, C.S.; Ferdinandez, H.S.; Manamgoda, D.S.; Udayanga, D.; Herath, I.S.; Thambugala, K.M.; Manawasinghe, I.S. What is a species in fungal plant pathogens? Fungal Diversity 2021, 109, 239–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, R.; Van Kan, J.A.; Pretorius, Z.A.; Hammond-Kosack, K.E.; Di Pietro, A.; Spanu, P.D.; Rudd, J.J.; Dickman, M.; Kahmann, R.; Ellis, J. The Top 10 fungal pathogens in molecular plant pathology. Molecular plant pathology 2012, 13, 414–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akgül, D.S.; Önder, S.; Savaş, N.G.; Yıldız, M.; Bülbül, İ.; Özarslandan, M. Molecular Identification and Pathogenicity of Fusarium Species Associated with Wood Canker, Root and Basal Rot in Turkish Grapevine Nurseries. Journal of Fungi 2024, 10, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwinell, L.D.; Barrows-Broaddus, J.B.; Kuhlman, E.G. Pitch canker: a disease complex. Plant Dis 1985, 69, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhlman, E.; Dianis, S.; Smith, T. Epidemiology of pitch canker disease in a loblolly pine seed orchard in North Carolina. Phytopathology 1982, 72, 1212–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCain, A.; Koehler, C.; Tjosvold, S. Pitch canker threatens California pines. California agriculture 1987, 41, 22–23. [Google Scholar]

- Muramoto, M.; Dwinell, L. Pitch canker of Pinus luchuensis in Japan. 1990.

- Guerra-Santos, J. Pitch canker on Monterey pine in Mexico. Current and potencial impacts of pitch canker in radiata pine. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Impact Monterey Workshop. Monterey, California, CSIRO, Collingwood, Victoria, Australia, 1999.

- Viljoen, A.; Marasas, W.; Wingfield, M.; Viljoen, C. Characterization of Fusarium subglutinans f. sp. pini causing root disease of Pinus patula seedlings in South Africa. Mycological Research 1997, 101, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landeras, E.; García, P.; Fernández, Y.; Braña, M.; Fernández-Alonso, O.; Méndez-Lodos, S.; Pérez-Sierra, A.; León, M.; Abad-Campos, P.; Berbegal, M. Outbreak of pitch canker caused by Fusarium circinatum on Pinus spp. in northern Spain. Plant Disease 2005, 89, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingfield, M.; Hammerbacher, A.; Ganley, R.; Steenkamp, E.; Gordon, T.; Wingfield, B.; Coutinho, T. Pitch canker caused by Fusarium circinatum—A growing threat to pine plantations and forests worldwide. Australasian Plant Pathology 2008, 37, 319–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storer, A.J.; Wood, D.L.; Gordon, T.R. The epidemiology of pitch canker of Monterey pine in California. Forest Science 2002, 48, 694–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drenkhan, R.; Ganley, B.; Martín-García, J.; Vahalík, P.; Adamson, K.; Adamčíková, K.; Ahumada, R.; Blank, L.; Bragança, H.; Capretti, P. Global geographic distribution and host range of Fusarium circinatum, the causal agent of pine pitch canker. Forests 2020, 11, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization (EPPO). Distribution Fusarium circinatum. Available online: https://gd.eppo.int/taxon/GIBBCI/distribution (accessed on October 28).

- Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Alimentación y la Agricultura. Dirección de recursos forestales. Estado de la diversidad biológica de los árboles y bosques de Honduras. Available online: https://www.fao.org/4/j0607s/j0607s00.htm#TopOfPage (accessed on 27 September 2024).

- Instituto de Conservación Forestal. Anuario Estadistico Forestal de Honduras, 3era edición. Centro de Información y Patrimonio Forestal, Unidad de Estadisticas Forestales. Available online: https://icf.gob.hn/?portfolio=cipf-2 (accessed on 27 September 2024).

- Myers, N.; Mittermeier, R.A.; Mittermeier, C.G.; Da Fonseca, G.A.; Kent, J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 2000, 403, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coates, A.G. Paseo Pantera: una historia de la naturaleza y cultura de Centroamérica. (No Title) 2003.

- Naciones Unidas. La Agenda 2030 y los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible: una oportunidad para América Latina y el Caribe (LC/G.2681-P/Rev.3), Santiago. Available online: https://repositorio.cepal.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/cb30a4de-7d87-4e79-8e7a-ad5279038718/content (accessed on 27 September 2024).

- Stone, J.K.; Polishook, J.D.; White, J.F. Endophytic fungi. Biodiversity of fungi: inventory and monitoring methods 2004, 241, 270. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz, B.; Enríquez, L.; Mejía, K.; Yanez, Y.; Sorto, Y.; Guzman, S.; Aguilar, K.; Fontecha, G. Molecular characterization of endophytic fungi from pine (Pinus oocarpa) in Honduras. Revis Bionatura 2022; 7 (3) 13. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Tj, W. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. PCR protocols: a guide to methods and applications 1990.

- O’Donnell, K.; Kistler, H.C.; Cigelnik, E.; Ploetz, R.C. Multiple evolutionary origins of the fungus causing Panama disease of banana: concordant evidence from nuclear and mitochondrial gene genealogies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1998, 95, 2044–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, N.L.; Donaldson, G.C. Development of primer sets designed for use with the PCR to amplify conserved genes from filamentous ascomycetes. Applied and environmental microbiology 1995, 61, 1323–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirenberg, H.I.; O’Donnell, K. New Fusarium species and combinations within the Gibberella fujikuroi species complex. Mycologia 1998, 90, 434–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vettraino, A.M.; Potting, R.; Raposo, R. EU legislation on forest plant health: An overview with a focus on Fusarium circinatum. Forests 2018, 9, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evira-Recuenco, M.; Iturritxa, E.; Raposo, R. Impact of seed transmission on the infection and development of pitch canker disease in Pinus radiata. Forests 2015, 6, 3353–3368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, Y.; Iturritxa, E.; Elvira-Recuenco, M.; Raposo, R. Survival of Fusarium circinatum in soil and Pinus radiata needle and branch segments. Plant Pathology 2017, 66, 934–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvořák, M.; Janoš, P.; Botella, L.; Rotková, G.; Zas, R. Spore dispersal patterns of Fusarium circinatum on an infested Monterey pine forest in North-Western Spain. Forests 2017, 8, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, I.; Góis, A.; Camacho, R.; Nóbrega, V.; Fernandez. The impact of urban and forest fires on the airborne fungal spore aerobiology. Aerobiologia 2018, 34, 585–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobziar, L.N.; Thompson III, G.R. Wildfire smoke, a potential infectious agent. Science 2020, 370, 1408–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepting, G.H.; Roth, E.R. Pitch canker, a new disease of some southern pines. 1946.

- Dvorak, W.; Potter, K.; Hipkins, V.; Hodge, G. Genetic diversity and gene exchange in Pinus oocarpa, a Mesoamerican pine with resistance to the pitch canker fungus (Fusarium circinatum). International Journal of Plant Sciences 2009, 170, 609–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.K.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Egidi, E.; Guirado, E.; Leach, J.E.; Liu, H.; Trivedi, P. Climate change impacts on plant pathogens, food security and paths forward. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2023, 21, 640–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park Williams, A.; Allen, C.D.; Macalady, A.K.; Griffin, D.; Woodhouse, C.A.; Meko, D.M.; Swetnam, T.W.; Rauscher, S.A.; Seager, R.; Grissino-Mayer, H.D. Temperature as a potent driver of regional forest drought stress and tree mortality. Nature climate change 2013, 3, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, M.R.; Bocatelli, B.; Billings, R. Cambio climático y eventos epidémicos del gorgojo descortezador del pino” Dendroctonus frontalis” en Honduras. Forest systems 2010, 19, 70–76. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, C.D.; Macalady, A.K.; Chenchouni, H.; Bachelet, D.; McDowell, N.; Vennetier, M.; Kitzberger, T.; Rigling, A.; Breshears, D.D.; Hogg, E.T. A global overview of drought and heat-induced tree mortality reveals emerging climate change risks for forests. Forest ecology and management 2010, 259, 660–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.; Sato, M.; Ruedy, R.; Lo, K.; Lea, D.W.; Medina-Elizade, M. Global temperature change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2006, 103, 14288–14293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, M.J. Temperature: effects on Fusarium subglutinans f. sp. pini infection on juvenile Pinus radiata (Monterey pine) and influence on growth of Fusarium subglutinans f. sp. pini isolates from California and Florida; San Jose State University: 1994.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística de Honduras. Boletín temperatura atmosférica 2017–2021. Available online: https://ine.gob.hn/v4/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Temperatura-2017-2021.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2024).

- Instituto Nacional de Conservación Forestal. Areas Protegidas y Vida Silvestre. (ICF). Norma técnica para el manejo de insectos descortezadores del pino (Dendroctonus spp. e Ips spp.). Available online: https://icf.gob.hn/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Norma-T%E2%80%9Acnica-MIDP_-1.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2024).

- Instituto Nacional de Conservación Forestal. Areas Protegidas y Vida Silvestre (ICF). Informe de episodio de ataque del gorgojo descortezador del pino dendroctonus frontalis en Honduras 2014-2017. Available online: https://icf.gob.hn/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Informe-Episodio-de-Plaga-2014-2017.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2024).

- Billings, R.; Clarke, S.; Espino-Mendoza, V.; Cordón Cabrera, P.; Meléndez Figueroa, B.; Ramón Campos, J.; Baeza, G. Bark beetle outbreaks and fire: a devastating combination for Central America’s pine forests. Unasylva 2004, 55, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, V.V.; Naseer, A.; Mogilicherla, K.; Trubin, A.; Zabihi, K.; Roy, A.; Jakuš, R.; Erbilgin, N. Understanding bark beetle outbreaks: exploring the impact of changing temperature regimes, droughts, forest structure, and prospects for future forest pest management. Reviews in Environmental Science and Bio/Technology 2024, 1-34. [CrossRef]

- Gajendiran, K.; Kandasamy, S.; Narayanan, M. Influences of wildfire on the forest ecosystem and climate change: A comprehensive study. Environmental Research 2024, 240, 117537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Instituto de Conservación y Desarrollo Forestal Áreas Protegidas y Vida Silvestre (ICF Honduras). Estadisticas Incendios Forestales Reportados en Honduras. Available online: https://sigmof.icf.gob.hn/reportes/incendios-forestales-2/ (accessed on 17 November 2024).

- Forestry Commission. Contingency plan pitch canker of pine. Available online: https://cdn.forestresearch.gov.uk/2022/02/contingency-plan-pitch-canker-of-pine-published-_sept-05-2016.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2024).

- International Plant Protection Convention (IPPC). Diagnostic protocols for regulated pests, DP 22: Fusarium circinatum. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/30e5bc8f-4c8e-491d-9fc6-7e1b72a5dbd0/content (accessed on 17 November 2024).

| Code | Collection season | Department | Collection coordinates | Sample | Symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01-2023 | June 20 | Comayagua | X: 409008; Y: 1614567; A: 1133 | Tree in natural forest | Needles with chlorosis, treetop dieback, resin exudation |

| 02-2023 | July 18 | Francisco Morazán | X: 475338; Y: 1559190; A:1082 | Nursery seedling | Needles with yellow and reddish color |

| 09-2023 2 | September 19 | El Paraíso | X: 545270; Y: 1550795; A: 745 | Nursery seedling | Lack of growth, discoloration and wilting in the needles |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).