1. Introduction

In 2019, the carbon dioxide concentration in the atmosphere increased by 409.9 parts per million, while CO

2 emissions increased by 37 billion tons. Both parameters have a very strong direct correlation. Global warming and climate change are closely related to CO

2 levels in the atmosphere, as well as levels of other greenhouse gases such as methane and nitrous oxide [

1,

2]. Reducing CO

2 emissions from anthropogenic activities has been identified as the most important factor in reducing or stopping global warming [

3]. The 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference, COP 21, established a goal of keeping global warming between 1.5 °C and 2 °C, in accordance with the recommendations of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) [

4]. There are two main options for achieving this goal: 1) substitution of fossil fuels by renewable fuels; and 2) capture of CO

2 from the atmosphere. In the case of CO

2 capture, various materials or processes, such as membrane separation and adsorptive technologies, have been used. The most common materials found to be considered in adsorptive technologies are activated carbon, amorphous silica, metalorganic compounds, and zeolites [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. To obtain the cheapest process, an optimization of the material’s performance and cost should be performed.

Some of the most promising materials to be used in this field are zeolites. Natural or synthetic, they have crystalline and microporous structures. Other features include a large surface area, thermal stability, and selectivity [

6,

7]. Their adsorption capacity is affected by the alkalinity, porosity, and intensity of the electric field used during adsorption [

7,

8]. Synthetic zeolites can be made from aluminosilicate raw materials or industrial wastes like fly ash and rice husk ash [

9,

10]. Because the components are less prone to react, zeolites derived from waste materials typically have lower efficiencies than those derived from raw materials [

10]. Despite this disadvantage, zeolites derived from wastes are less expensive.

Geopolymers are other interesting materials for CO

2 capture. They can also be obtained from waste, and the synthesis occurs at lower temperatures and pressures than zeolites, resulting in less energy consumption [

11,

12,

13]. Because of their structural, thermal, and physical properties, they have attracted the attention of researchers all over the world [

14,

15] due to the possibility of developing particular properties such as high compressive strength, adsorptive capacity to remove heavy metals dissolved in water, moisture buffering capacity, and CO

2 adsorptive capacity [

16]. The properties are strongly affected by the operational conditions used in the synthesis and the composition of the raw materials [

17,

18]. Several solid residues containing aluminosilicates can also be incorporated, such as fly ash [

19], red mud [

20,

21], and blast furnace slags [

14], as attractive alternatives to immobilize industrial solid residues.

In general, crystalline geopolymers are produced when the Si/Al ratio is ≥1, and the curing conditions are particularly important to promote crystallization. Zeolitic phases such as hydroxy-sodalite (SOD), faujasite (FAU), and Linde Type A (LTA) are among the most commonly found in geopolymerization processes. Geopolymer-zeolite has attracted the interest of many researchers [

15]

The objective of this research is to investigate the synthesis of CO2 adsorbents from two different types of waste, red mud and fly ash. The strategy was to increase the adsorptive capacity of zeolite sites while also increasing the mechanical strength by having a geopolymer matrix. The zeolite type was not previously defined. In order to form zeolites in-situ, dispersed along with a geopolymer matrix, the composition and curing conditions were established.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials

Aluminosilicates were obtained from washed kaolin, fly ash (FA), and red mud (RM). Torrecid (Içara, SC, Brazil) supplied the washed kaolin. FA originated at the Jorge Lacerda thermal power plant (Capivari de Baixo, SC, Brazil). RM was obtained from the Alunorte bauxite refinery (Barcarena, PA, Brazil). The alkali activator was made up of sodium hydroxide aqueous solution (50% w/w NaOH) and sodium silicate aqueous solution (15.1% w/w Na

2O and 33.2% w/w SiO

2) supplied by Oregon Química (Içara, SC, Brazil). FA was dried and subjected to a magnetic separation before use. Kaolin and RM were dried and calcined in an air atmosphere at 800 °C for 20 min at a heating rate of 10 °C/min [

12,

22].

2.2. Raw Materials Characterization

Table 1 shows the composition measured by X-ray fluorescence (XRF, Panalytical, AXIOS Max) of those materials after the aforementioned procedure.

Table 1 also shows the composition taken into account for the reaction to calculate the dosage to achieve the desired stoichiometry. Calcination promotes amorphization in kaolin due to crystalline water decomposition, resulting in a so-called metakaolin (MK). In the case of RM, the literature indicates that 800 °C is high enough to decompose gibbsite, sodalite, and hydroxides [

23,

24], resulting in an amorphous structure with higher reactivity.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Hitachi, TM3030) and X-ray diffraction (XRD, Rigaku, MiniFlex600, Cu Kα radiation, from 3° to 80°) were used to characterize the raw materials. The particle size distribution was determined in a liquid medium by laser diffraction (Cilas 1064). Particle sizes smaller than 45 µm are within the expected range for geopolymers to have satisfactory strength and workability [

19]

2.3. Geopolymers Synthesis

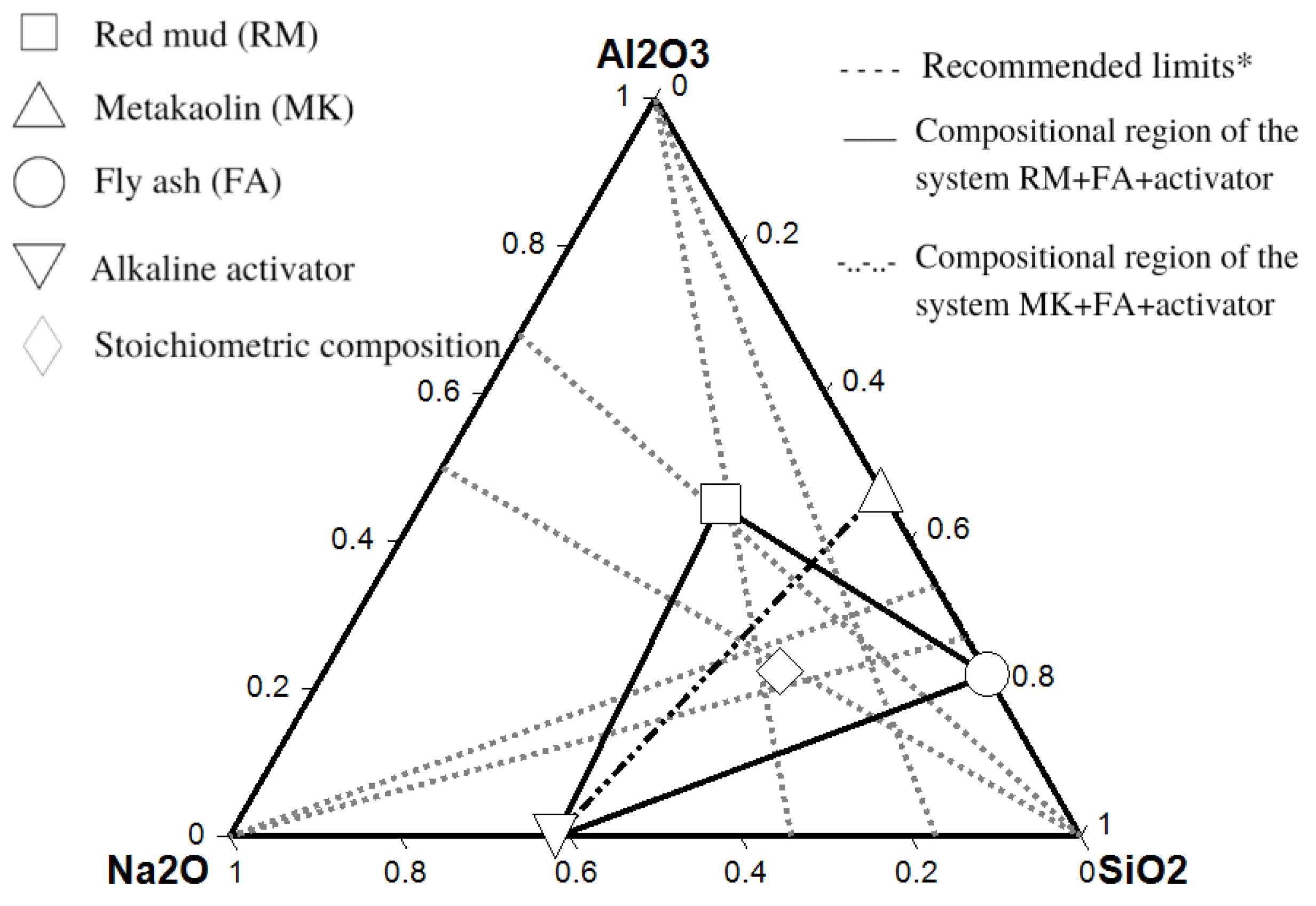

Table 2 shows the composition of raw material in terms of reactive oxides and mass dosages. The ternary diagram in

Figure 1 depicts the oxide composition of all materials based on reactive oxides. The compositional intervals proposed by Davidovits et al. [

25] are represented by gray dashed lines, with the intersection region represented by a 4-sided polygon. It was found that the planned geopolymer dosage exceeds the suggested limits. This displacement in the direction of the greatest amount of Na

2O was chosen to shift the equilibrium toward the formation of zeolitic structures in the geopolymer matrix.

The composition was set outside of the recommended limits for structural applications where high mechanical strength is the most important feature. The goal was to shift the reaction equilibrium and induce crystallization of zeolite sites to increase surface area and thus CO2 adsorption.

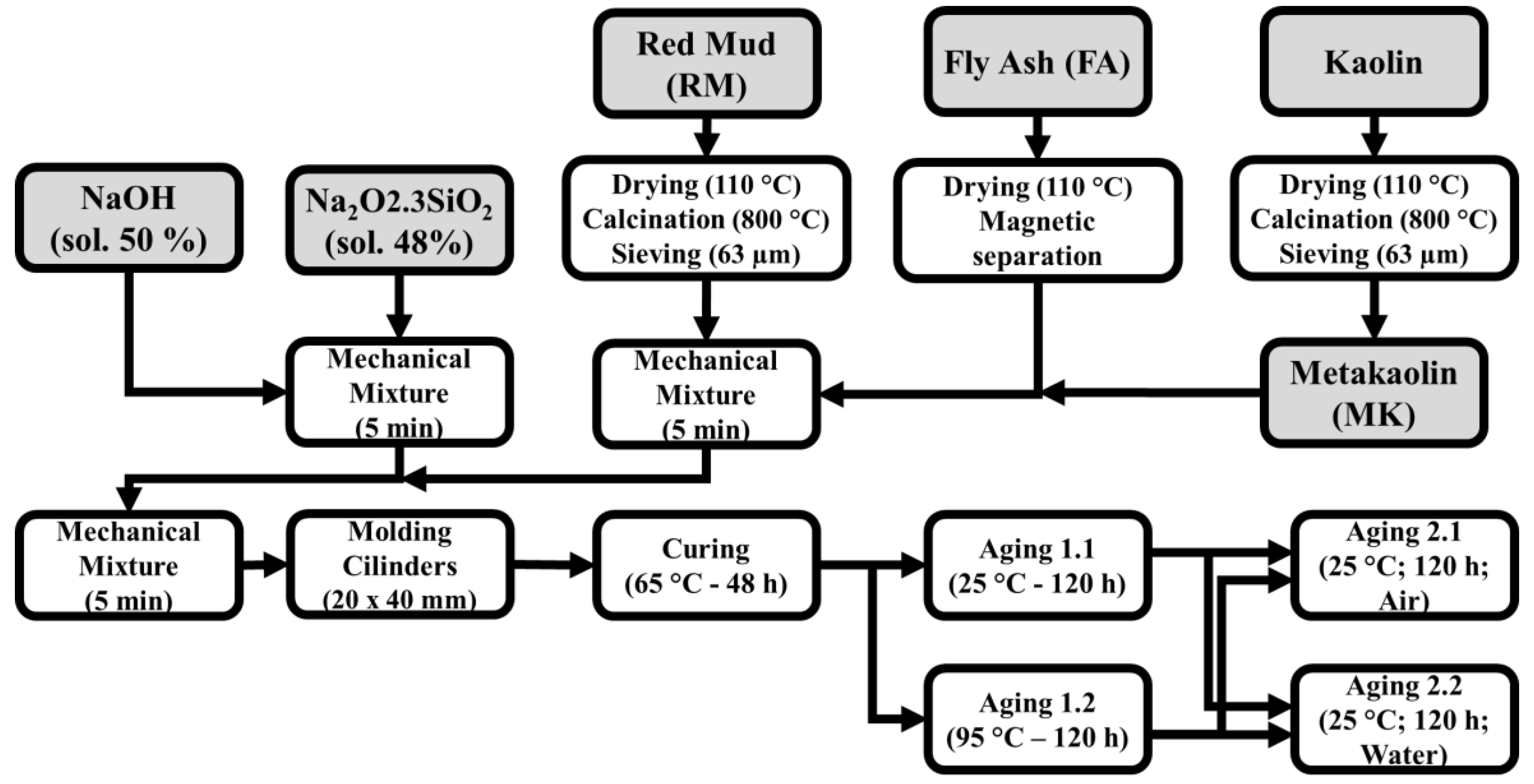

Figure 2 is a flowchart representing the process and general conditions applied to obtain the geopolymer samples. After the curing time, the samples were demolded and sealed with a polymeric thin film for the Aging 1 step. The film used in Aging 1 was removed for Aging 2. All experimental runs and labels are listed in

Table 3.

2.4. Geopolymer Characterization

XRD was used to determine the qualitative mineralogical composition of geopolymers. SEM was applied to examine the morphology. A universal testing machine (EMIC, DL10000, 100 kN) was employed to measure compressive strength at a load application rate of 1 mm/min. The pressure range P⁄P0 from 0.05 to 0.3 was used to calculate a specific surface area by the method of Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) (Nova 1200e, Quantachrome).

The CO

2 adsorption test was carried out on powder samples using a thermogravimetric analyzer (Netzsch, STA-449 F3). The material was subjected to a pre-treatment under N

2 atmosphere (flow rate of 50 ml.min

-1 for 180 min at 320 °C) to remove moisture and other adsorbed gases. The CO

2 adsorption occurred with a flow of 80 ml.min-1 and 99 % purity, under isothermal conditions at 35 °C and atmospheric pressure, reproducing the conditions reported in the literature [

12]. Finally, a CO

2 desorption step was performed for 60 min at 320 °C and an N

2 flow rate of 50 ml.min

-1. Near-equilibrium conditions were used to calculate adsorption mass values.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of Raw Materials Subsection

3.2.1. Raw Materials Structure

It is critical for geopolymerization that materials have an amorphous structure, which is the starting point for the reactions [

26,

27,

28]. Amorphous-rich materials such as fly ash (FA) and metakaolin (MK) are well known. According to the results shown in

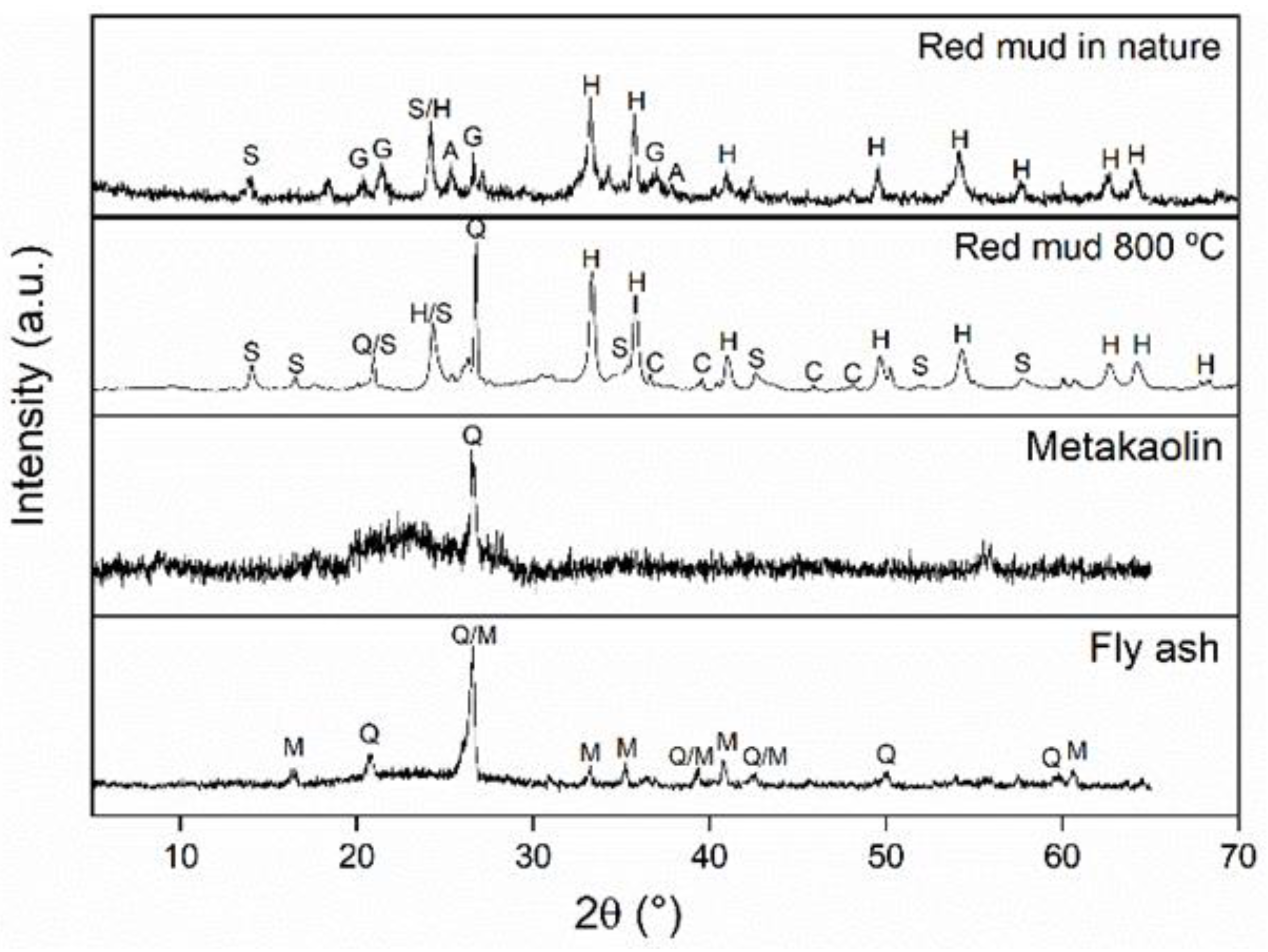

Table 1, FA contains ~67.3% amorphous phase, while MK is ~94.2% amorphous. The XRD patterns of FA, MK, RM, and calcined RM are shown in

Figure 4. Quartz

and mullite

were the crystalline phases found in FA. Quartz was the only crystalline phase identified in MK. The presence of a large number of crystalline phases is observed in RM: hematite

; sodalite ((

),

); gibbsite

; anatase

; and calcite, (Mg

0.1Ca

0.9CO

3 - 01-071-1663). From the standard composition of each phase, a rational analysis results in an approximate mass composition of 37% hematite, 39% sodalite, 10% gibbsite, 7% anatase, with a total of crystalline phases of ~ 93%. The low intensity of the sodalite peak indicates that this phase has a low crystallization level. The decomposition of gibbsite, anatase, and calcite can be seen after calcination. Furthermore, a quartz peak was also observed; quartz was most likely formed from an amorphous phase present in RM. These findings point to an increase in RM crystallization after calcination under the conditions used.

Figure 3.

XRD Diffractograms: (a) fly ash (a) metakaolin; (b) red mud calcined at 800°C; (d) uncalcined red mud. Q: Quartz, M: Mullite, C: Calcite, H: Hematite, S: Sodalite, A: Sodium aluminosilicate, G: Gibbsite.

Figure 3.

XRD Diffractograms: (a) fly ash (a) metakaolin; (b) red mud calcined at 800°C; (d) uncalcined red mud. Q: Quartz, M: Mullite, C: Calcite, H: Hematite, S: Sodalite, A: Sodium aluminosilicate, G: Gibbsite.

3.1.2. Raw Materials Morphology

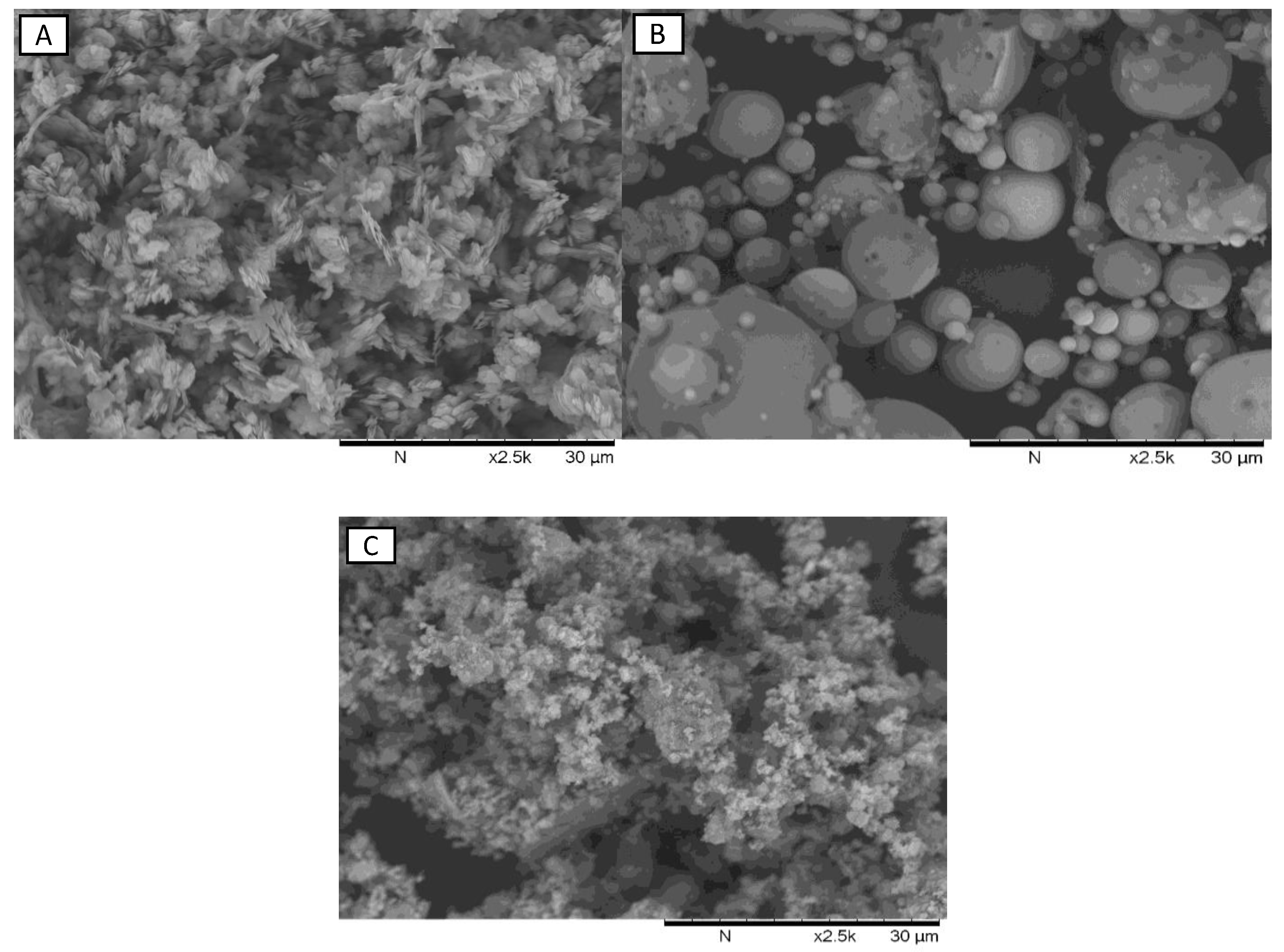

The SEM images of the base materials are shown in

Figure 4. Because of the melting that occurred when the coal powder was burned inside the furnace, FA has a spherical shape [

28,

29,

30]. Since it is derived from kaolinite, metakaolin particles are flakes [

12] while red mud has more erratic formats. The finest group is most likely made up of aluminosilicate phases, while the coarse group is most likely made up of iron minerals [

28,

31].

Figure 4.

SEM Morphology: (a) metakaolin; (b) fly ash; (c) red mud calcined at 800 °C.

Figure 4.

SEM Morphology: (a) metakaolin; (b) fly ash; (c) red mud calcined at 800 °C.

3.2. Geopolymer Characterization

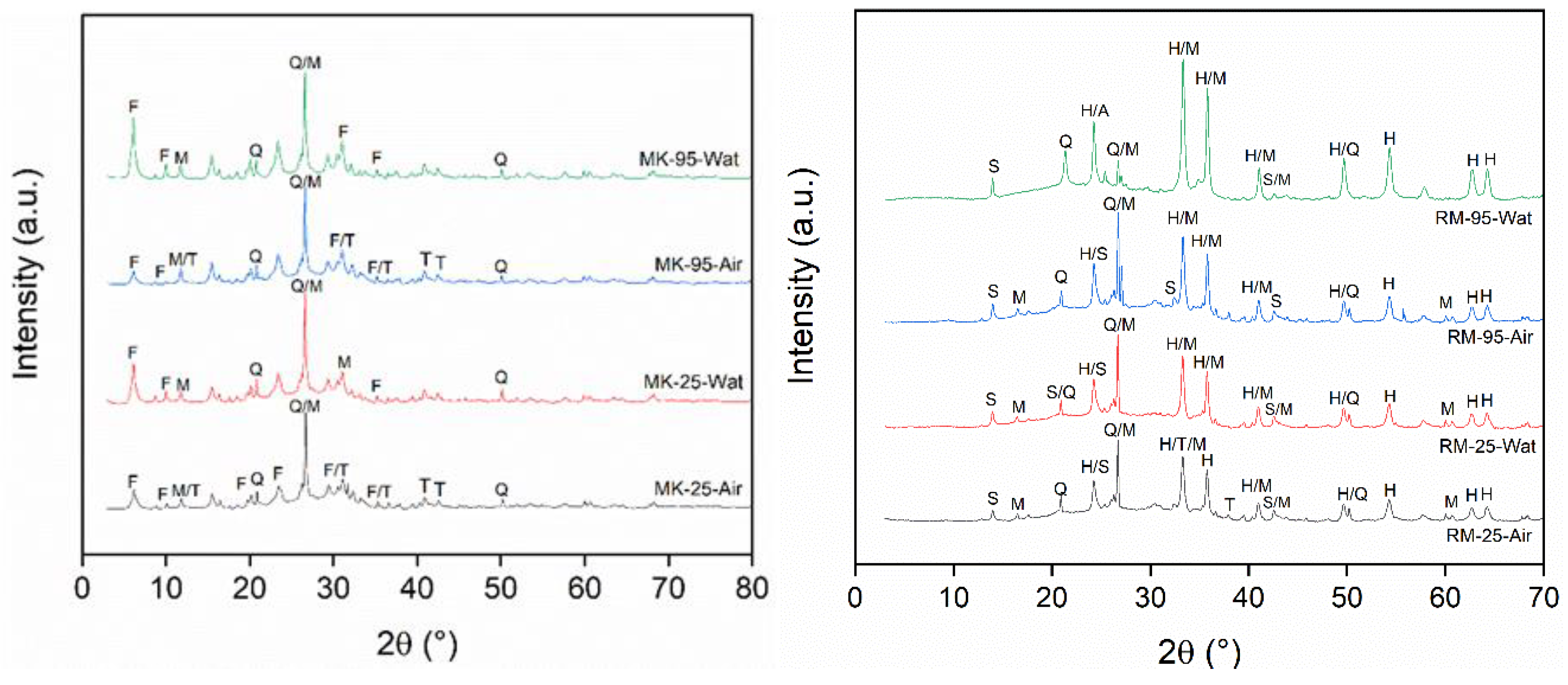

3.2.1. Geopolymer Structure

Figure 5 depicts the obtained XRD pattern for all geopolymer compositions and aging conditions. Geopolymers are amorphous structures that are primarily formed from aluminosilicate sources [

28,

29]. The crystalline phases found in geopolymers are typically leftover from the raw materials. This is true for quartz and mullite in all geopolymers.

Figure 5b shows hematite and sodalite in geopolymers derived from RM+FA. The presence of mullite, calcite, and zeolites in geopolymers derived from MK and FA has also been reported in the literature [

32].

Figure 5 also depicts the formation of new phases in various compositions and aging conditions. In the case of MK+FA geopolymers, new zeolite phases could be identified. According to preliminary identification, such phases are primarily made up of Na-faujasite structure, which is most likely a combination of Faujasita-Na (zeolite Y)

, Faujasite-Na (zeolite X)

, Faujasite-Na

and zeolite X

. Faujasites are classified into two groups: X and Y. Group X has a Si/Al ratio of 1.0 to 1.5, while Group Y has a Si/Al ratio greater than 1.5 [

33].

The intensity of the lower angle diffraction of faujasite observed in

Figure 5a was higher in water-aged samples than in air-aged samples. Aging 1 at 95 °C produces a higher peak intensity than aging at 25 °C. This effect could be attributed to increased ionic diffusion in the presence of water and at higher temperatures. Thermonatrite (Na

2CO

3·H2O) was also found in low concentrations, most likely as a result of an excess of NaOH in the system.

Only at 95 °C and after water aging could a difference in geopolymer derived from RM+FA be observed.

Figure 5b depicts an apparent increase in the intensity of sodalite and a strong reduction in quartz. This finding emphasizes the importance of the aging condition in the formation of structural changes.

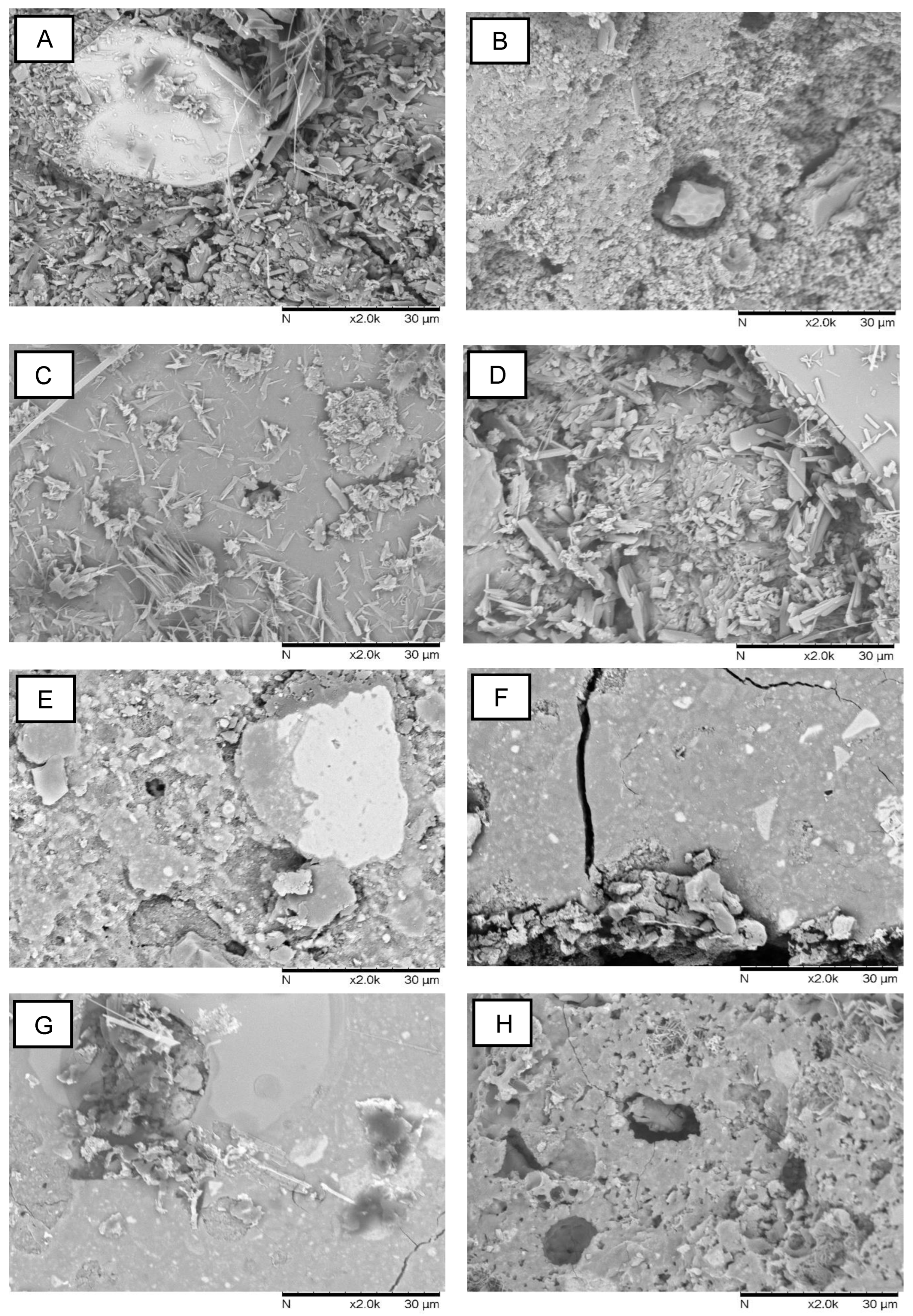

3.2.2. Geopolymer Microstructure

Figure 6 depicts the microstructure of the samples. The gel matrix formed by the geopolymer structure can be identified in all conditions. In ease case, there are some unreacted particles as well. Geopolymers frequently correspond to this composite microstructure [

30]. Unreacted particles are used as fillers and can provide some reinforcement [

34].

The microstructures were significantly influenced by the aging conditions. The highest concentrations of unreacted particles were found in MK-FA compositions after 25°C, followed by air exposure. Aging at 95 °C induced the formation of a denser matrix. The crystallization of faujasite particles is also visible, with concentrations higher in samples subjected to water aging at 25 and 95 °C, respectively. This agrees with the XRD findings. Unreacted RM particles are likely to remain in the RM+FA composition due to their irregular format and size distribution. By reacting with the activator, the FA particles were most likely responsible for forming the gel structure. Except for 25 °C and air, the aging conditions appear to have little effect on the microstructure. As with MK+FA, a more granular texture can be seen.

3.2.3. Geopolymer Properties

Table 4 shows the mechanical strength, surface area, and CO

2 adsorptive capacity for the materials produced in this study. First and foremost, it is critical to note the wide range of properties obtained in response to the starting material and aging conditions. Mechanical strength ranges from 0 to 11.8 MPa, surface area from 1.8 to 238.4 m

2.g

-1, and CO

2 adsorption from 0.05 to 2.32 mmol.g

-1.

The results of MK+FA and RM+FA samples indicate that both compression strength and adsorption capacity are antagonistic properties. The higher mechanical strength, 11.8 and 8.9 MPa for MK+FA and RM+FA systems, respectively, resulted in lower CO

2 adsorption, 0.83 and 0.07 mmol.g

-1, when compared within their group. Despite this negative correlation, the literature reports that geopolymer-zeolite systems with compressive strength ranging from 3.0 to 7.5 MPa are sufficient for self-supporting monoliths [

15,

35]. Mechanical strength increases with low-temperature aging (25 °C) and air exposure. Because of the crystallization of zeolite phases, higher temperatures and water aging result in lower compression strength and higher adsorption capacity.

Water aging had the greatest effect on adsorption capacity in all cases. Because of the acidic nature of CO

2 molecules, the literature reports a positive correlation between CO

2 adsorptive capacity and active site basicity [

12]. Water aging has increased the surface area of the MK+FA system, and thus the CO

2 adsorption capacity. The specific adsorption numbers suggest a possible decrease in the basicity of the sites. Water aging caused sodium leaching, which likely reduced the sodium atoms in the zeolite framework. Water aging has increased the surface area and specific adsorption of the RM+FA system. This system’s lower surface area and low reactivity could be attributed to the presence of higher crystalline phases and hematite. According to the literature, Fe ions influence the dissolution of aluminum silicates [

24].

The CO2 adsorption results of composite geopolymer-zeolite can be compared to the starting materials: MK – 0.33 mmol.g-1, FA – 0.53 mmol.g-1, and RM – 0.07 mmol.g-1. All composites resulted in higher adsorption capacity for the MK+FA system, where the values varied between 2 and 5 times more CO2 adsorbed per mass of adsorbent. These results can be attributed to the zeolite sites. The effect of the RM+FA system was the opposite: 1 to 5 times lower than the starting materials.

The findings can also be compared to those of other studies. Freire et al. [

12] reported a higher value of 0.78 mmol.g

-1 of CO

2 adsorbed at 1 atm and 35 °C for geopolymers derived from MK and FA, and 0.80 mmol.g

-1 for geopolymers derived from MK, FA, and rice husk ash, both with NaOH as an activator. In those cases, the mechanical strength was 11 and 3 MPa, respectively.

Minelli et al. [

13] reported a higher value of 0.62 mmol.g

-1 for geopolymer obtained from MK and KOH as an activator under the same adsorption conditions. According to Esteves et al. [

36], activated carbon has a molarity of 1.2 mmol.g

-1. Sayari and Belmabkhout [

37] reported 2.6 mmol.g

-1 for amine-mesoporous silica in a more complex system, and Cavenati et al. [

38] reported 4.0 mmol.g

-1 for pure zeolite 13X. This comparison indicates that the materials obtained in this work have an interesting balance of good performance and a simple synthesis method. Scaling up will most likely result in a low-cost material at the end of the process.

4. Conclusions

A composite geopolymer+zeolite monolithic material for CO2 adsorption was obtained and characterized. The starting materials were fly ash (FA), red mud (RM), and metakaolin (MK) with NaOH and sodium silicate as activators. To achieve a lower cost end product, the use of waste material and a simple synthesis process were chosen. The starting composition was designed with an excess of activator to induce an in-situ zeolite crystallization in a typical geopolymer route. Two aging steps were applied after curing to evaluate their effects on the product characteristics.

In terms of CO2 adsorption and mechanical properties, the materials made from RM and FA did not perform well. RM components Al2O3, SiO2, and Na2O do not appear to be available for reaction with the activator and FA. The thermal treatment at 800 °C did not result in the expected increase in the amorphous phase. Other pretreatments could eventually be investigated to increase the red mud reactivity.

The materials derived from MK and FA performed well. The starting composition as well as aging cause zeolites to crystallize. The dispersed faujasite-Na family was formed in the geopolymer matrix, according to the primary identification. The aging condition has a significant impact on the materials’ phase, microstructure, and performance. Higher temperatures during the first and second agings under water resulted in a larger surface area and CO2 adsorption capacity. Water aging appears to be the most important step in zeolite crystallization and growth. Compression strength decreases as the presence of zeolites increases.

All of the results obtained from the MK+FA system, ranging from 0.83 to 2.32 mmol/g, are interesting when compared to other adsorbent materials, particularly the simplest ones. The applied route is straightforward and can be optimized to produce higher-performance material or reduce processing time.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, De Noni Jr., A., Moreira, R.F.P.M, Hotza, D.; methodology, Freire, A.L., Elysey F., Peternson, M.; formal analysis, Silveira, A.R , De Noni Jr., A.; investigation, Silveira, A.R.; resources, De Noni Jr., A.; data curation, X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, Silveira, A.R.; writing—review and editing, Hotza, D., Doyle, A., Pergherd, S.; supervision, De Noni Jr., A.; funding acquisition, Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Brazilian agency CAPES/PROEX, grant number 88882.345097/2019/01 and CNPQ/Universal 423626/2016-7.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the financial support from the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES), under grant number PROEX 88882.345097/2019/01, and the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) under grant numbers 423626/2016-7.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lindsey, R., 2020. Climate Change: Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide [WWW Document]. Climate.gov.

- Roser, H., Max, R., 2020. Atmospheric concentrations. [WWW Document]. Our World Data.

- Sifat, N.S., Haseli, Y., 2019. A Critical Review of CO2 Capture Technologies and Prospects for Clean Power Generation. Energies 12, 4143. [CrossRef]

- Koytsoumpa, E.I., Bergins, C., Kakaras, E., 2018. The CO2 economy: Review of CO2 capture and reuse technologies 132, 3–16. [CrossRef]

- Chan, W.H., Mazlee, M.N., Ahmad, Z.A., Ishak, M.A.M., Shamsul, J.B.., 2017. The development of low cost adsorbents from clay and waste materials : a review. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 19, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Azmi, A.A., Aziz, M.A.A., 2019. Mesoporous adsorbent for CO2 capture application under mild condition: A review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 7, 103022. [CrossRef]

- Nie, L., Mu, Y., Jin, J., Chen, J., Mi, J., 2018. Recent developments and consideration issues in solid adsorbents for CO2 capture from flue gas. Chinese J. Chem. Eng. 26, 2303–2317. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q., Luo, J., Zhong, Z., Borgna, A., 2011. CO2 capture by solid adsorbents and their applications: current status and new trends. Energy Environ. Sci. 4, 42–55. [CrossRef]

- Yao, G., Lei, J., Zhang, X., Sun, Z., Zheng, S., Komarneni, S., 2018. Mechanism of zeolite X crystallization from diatomite. Mater. Res. Bull. 107, 132–138. [CrossRef]

- Kuroki, S., Hashishin, T., Morikawa, T., Yamashita, K., Matsuda, M., 2019. Selective synthesis of zeolites A and X from two industrial wastes: Crushed stone powder and aluminum ash. J. Environ. Manage. 231, 749–756. [CrossRef]

- Chindaprasirt, P., Rattanasak, U., 2019. Characterization of porous alkali-activated fly ash composite as a solid absorbent. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 85, 30–35. [CrossRef]

- Freire, A.L., Moura-Nickel, C.D., Scaratti, G., De Rossi, A., Araújo, M.H., De Noni Júnior, A., Rodrigues, A.E., Castellón, E.R., de Fátima Peralta Muniz Moreira, R., 2020. Geopolymers produced with fly ash and rice husk ash applied to CO2 capture. J. Clean. Prod. 273, 122917. [CrossRef]

- Minelli, M., Medri, V., Papa, E., Miccio, F., Landi, E., Doghieri, F., 2016. Geopolymers as solid adsorbent for CO2 capture. Chem. Eng. Sci. 148, 267–274. [CrossRef]

- Lemougna, P.N., Wang, K., Tang, Q., Cui, X., 2017. Study on the development of inorganic polymers from red mud and slag system : Application in mortar and lightweight materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 156, 486–495. [CrossRef]

- Rożek, P., Król, M., Mozgawa, W., 2019. Geopolymer-zeolite composites: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 230, 557–579. [CrossRef]

- Rasaki, S.A., Bingxue, Z., Guarecuco, R., Thomas, T., Minghui, Y., 2019. Geopolymer for use in heavy metals adsorption, and advanced oxidative processes: A critical review. J. Clean. Prod. 213, 42–58. [CrossRef]

- Davidovits, J., 2002. 30 Years of Successes and Failures in Geopolymer Applications . Market Trends and Potential Breakthroughs . Geopolymer 2002 Conf. Oct. 28-29, 2002, Melbourne, Aust. 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J., He, P., Jia, D., Yang, C., Zhang, Y., Yan, S., Yang, Z., Duan, X., Wang, S., Zhou, Y., 2016. Effect of curing temperature and SiO2/K2O molar ratio on the performance of metakaolin-based geopolymers. Ceram. Int. 42, 16184–16190. [CrossRef]

- Duxson, P., Fernández-Jiménez, A., Provis, J.L., Lukey, G.C., Palomo, A., van Deventer, J.S.J., 2007. Geopolymer technology: the current state of the art. J. Mater. Sci. 42, 2917–2933. [CrossRef]

- Ascensão, G., Seabra, M.P., Aguiar, J.B., Labrincha, J.A., 2017. Red mud-based geopolymers with tailored alkali diffusion properties and pH buffering ability. J. Clean. Prod. 148, 23–30. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., Guo, Y., Ding, S., Zhang, H., Xia, F., Wang, J., 2019. Utilization of red mud in geopolymer-based pervious concrete with function of adsorption of heavy metal ions. J. Clean. Prod. 207, 789–800. [CrossRef]

- Kaya, K., Soyer-uzun, S., 2016. Evolution of structural characteristics and compressive strength in red mud – metakaolin based geopolymer systems. Ceram. Int. 42, 7406–7413. [CrossRef]

- Ye, N., Chen, Y., Yang, J., Liang, S., Hu, Y., Hu, J., Zhu, S., Fan, W., Xiao, B.Transformations of Na, Al, Si and Fe species in red mud during synthesis of one-part geopolymers, Cement and Concrete Research, Volume 101, 2017, Pages 123-130,. [CrossRef]

- Ye, N., Yang, J., Ke, X., Zhu, J. Li, Y. Xiang, C., Wang, H., Li, L., Xiao, B. Synthesis and Characterization of Geopolymer from Bayer Red Mud with Thermal Pretreatment 2014. [CrossRef]

- Davidovits, J.;, Davidovics, M., Davidovits, N., 1994. United States Patent.

- Davidovits, J., 2017. Geopolymers : Ceramic-Like Inorganic Polymers. J. Ceram. Sci. Technol. 8, 335–350. [CrossRef]

- He, J., Jie, Y., Zhang, J., Yu, Y., Zhang, G., 2013. Synthesis and characterization of red mud and rice husk ash-based geopolymer composites. Cem. Concr. Compos. 37, 108–118. [CrossRef]

- He, J., Zhang, J., Yu, Y., Zhang, G., 2012. The strength and microstructure of two geopolymers derived from metakaolin and red mud-fly ash admixture: A comparative study. Constr. Build. Mater. 30, 80–91. [CrossRef]

- Hu, W., Nie, Q., Huang, B., Shu, X., He, Q., 2018. Mechanical and microstructural characterization of geopolymers derived from red mud and fly ashes. J. Clean. Prod. 186, 799–806. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M., El-Korchi, T., Zhang, G., Liang, J., Tao, M., 2014. Synthesis factors affecting mechanical properties, microstructure, and chemical composition of red mud–fly ash based geopolymers. Fuel 134, 315–325. [CrossRef]

- Atasoy, A., 2005. An investigation on characterization and thermal analysis of the aughinish red mud. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 81, 357–361.

- Zhang, P., Wang, K., Wang, J., Guo, J., Ling, Y., 2021. Macroscopic and microscopic analyses on mechanical performance of metakaolin/fly ash based geopolymer mortar. J. Clean. Prod. 294, 126193. [CrossRef]

- Belaabed, R., El Knidri, H., El Khalfaouy, R., Addaou, A., Laajab, A., Lahsini, A., 2017. Zeolite Y synthesis without organic template: The effect of synthesis parameters. J. Mater. Environ. Sci. 8, 3550–3555.

- Koshy, N., Dondrob, K., Hu, L., Wen, Q., Meegoda, J.N., 2019. Synthesis and characterization of geopolymers derived from coal gangue, fly ash and red mud. Constr. Build. Mater. 206, 287–296. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Yan, C., Qiu, X., Li, D., Wang, H., Alshameri, A., 2016. Preparation of faujasite block from fly ash-based geopolymer via in-situ hydrothermal method. Rev. Mex. Urol. 76, 433–439. [CrossRef]

- Esteves, I.A.A.C., Lopes, M.S.S., Nunes, P.M.C., Mota, J.P.B., 2008. Adsorption of natural gas and biogas components on activated carbon. Sep. Purif. Technol. 62, 281–296. [CrossRef]

- Sayari, A., Belmabkhout, Y., 2010. Stabilization of Amine-Containing CO 2 Adsorbents: Dramatic Effect of Water Vapor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 6312–6314. [CrossRef]

- Cavenati, S., Grande, C.A., Rodrigues, A.E., 2004. Adsorption Equilibrium of Methane, Carbon Dioxide, and Nitrogen on Zeolite 13X at High Pressures. J. Chem. Eng. Data 49, 1095–1101. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).