1. Introduction

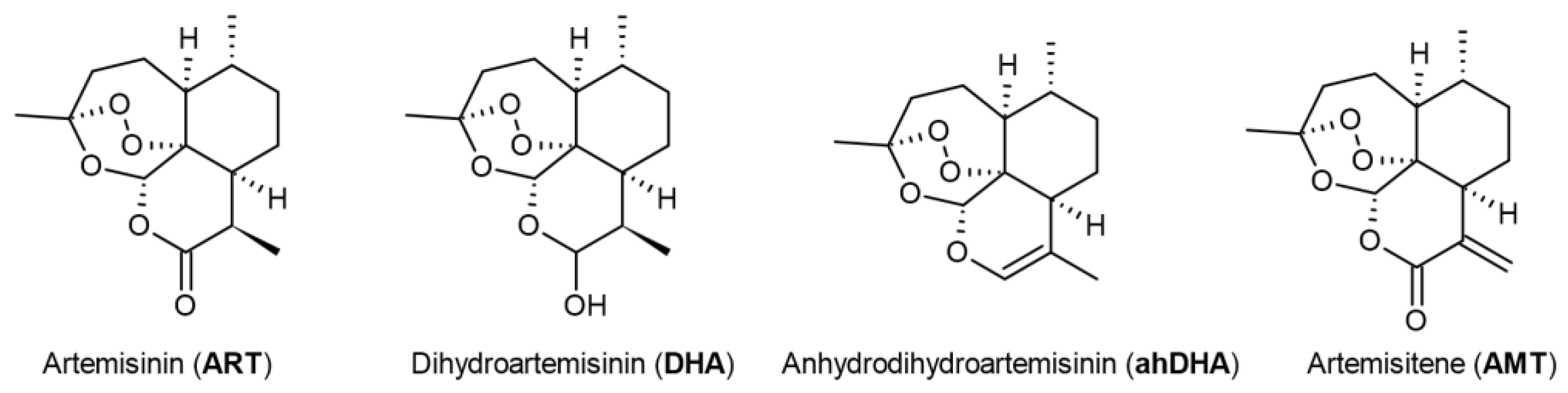

Artemisinin (ART) is a sesquiterpene lactone of the cadinane structural type, characterized by its unique endoperoxide moiety, which sets it apart from other compounds in this class. This natural substance, a secondary metabolite derived from

Artemisia annua L. (Asteraceae), was first recognized for its potent activity against the causative agent of tropical malaria (

Plasmodium sp.). This discovery spurred the extensive development and application of ART-based derivatives for the treatment of malaria [

1]. While its antimalarial activity has been extensively studied and continues to be a topic of scientific discussion, ART's broader therapeutic potential is garnering growing interest. Beyond its well-documented antimalarial properties, emerging research highlights its antitumor, anti-inflammatory, antidiabetic, and other beneficial effects. Notably, recent studies have pointed to the neuroprotective potential of ART, opening new avenues for investigation of its therapeutic potential [

2,

3,

4].

The broad biological activity, well-characterized toxicity profile, and high availability of ART as a starting molecule for modification (world production of ART is several hundred tons per year) suggest promising prospects for the development of ART-like molecules as potential candidates in medicinal chemistry. In addition, ART can easily cross the blood-brain barrier that makes it a feasible candidate for the treatment of neurological diseases [

5,

6].

The neuroprotective effects of ART have been demonstrated in various neuron-like cell types. ART has been shown to suppress sodium nitroprusside (NO donor)-induced cell death in PC12 cells and primary cortical neurons [

7]. Further studies revealed its protective effect against 6-OHDA (6-hydroxydopamine), MPP+ (1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium ion) and β-amyloid toxicity in PC12 cells, where the effect was accompanied by activation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) pathway [

2,

8]. Additionally, ART prevented glutamate-induced oxidative injury in the HT-22 mouse hippocampal cell line by activating the Akt signaling pathway [

9]. In experiments using SH-SY5Y cells (and primary cultures), ART protected against oxidative stress induced by hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2) via activation of the adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) pathway [

3]. ART also reduced apoptosis in SH-SY5Y cells following MPP+ treatment [

10].

The neuroprotective properties of ART have also been observed in various

in vivo models of neurodegenerative diseases (NDDs). These include 6-OHDA and MPTP-induced Parkinson’s disease (PD) models in mice [

8,

11], transgenic Alzheimer’s disease (AD) mouse models [

12,

13,

14], and a traumatic optic neuropathy model [

4].

A key aspect of neurodegeneration involves cellular pathological events such as protein aggregation and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress [

15,

16,

17]. While ER stress initially serves to balance protein production and degradation, chronic ER stress contributes to neurodegeneration by activating cell death pathways, leading to neuronal loss. Developing therapeutic strategies targeting these detrimental processes is an attractive approach for combating NDDs.

This study aimed to investigate the in vitro neuroprotective potential of ART in neuronal cell lines including primary neuronal hippocampal cultures, prompted by its observed ability to increase the viability of neuroblastoma cells in micromolar concentrations. Several ART derivatives, including its active metabolite dihydroartemisinin (DHA), were also evaluated as ART-like compounds; however, they exhibited greater toxicity in vitro compared to ART.

2. Results

2.1. Preparation of Artemisinin Analogues with Modifications in the Lactone Cycle

Based on literature data, a sequence of transformations leading to artemisitene (AMT), a lactone with an activated exomethylene group, was proposed (

Figure 1). It includes four stages. In the first stage, DHA can be obtained from ART by the known reduction reaction [

18]. To reduce the number of stages, commercially available DHA was chosen as the starting compound. When using boron trifluoride etherate as a dehydrating agent, anhydrodihydroartemisinin (ahDHA) is formed in quantitative yield [

19,

20].

The next stage includes two transformations: introduction of an oxygen atom into site of the future lactone cycle of AMT and simultaneous formation of an exomethylene group. Under photooxygenation conditions, when interacting with singlet oxygen, the main reaction product (hydroperoxide) is obtained rather slowly, even when using a powerful light source. This may be caused by the use of air as a reactant instead of pure oxygen and by suboptimal selection of the solvent and photosensitizer combination for reaction. We assume that modification of reaction conditions by replacing the photosensitizer (in photooxygenation) or the singlet oxygen source (in catalytic decomposition of hydrogen peroxide) allows one to significantly reduce the reaction time, while achieving high yields of hydroperoxide. The resulting hydroperoxide is then converted to AMT with a high yield under the action of acetic anhydride and pyridine [

20,

21].

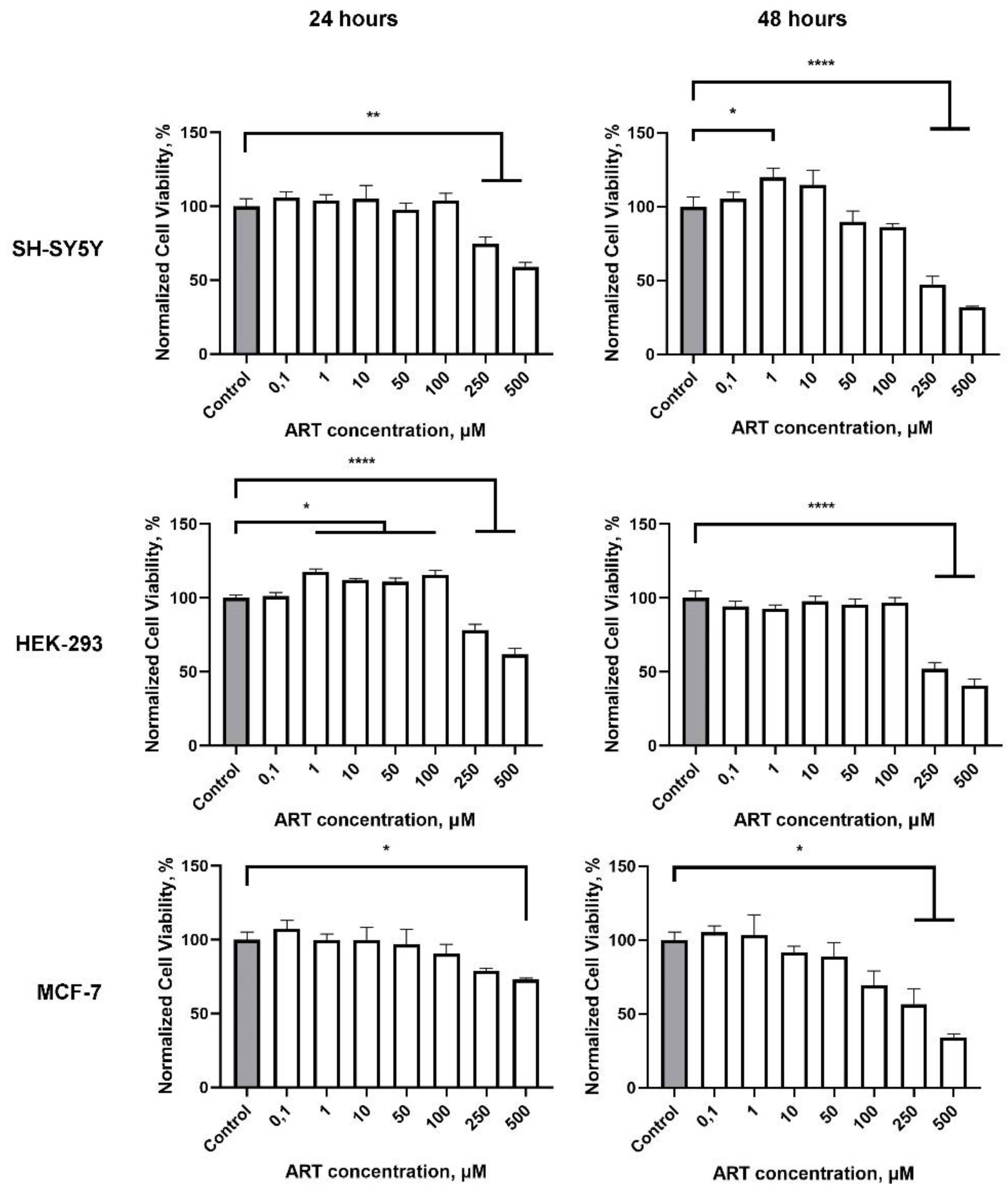

2.2. Artemisinin Increases Viability in SH-SY5Y and HEK-293 Cells, but Not in MCF-7 Cells

To examine the impact of ART on the survival of neuronal-like cells, we conducted an MTS assay on SH-SY5Y cells across a micromolar concentration range (0.1 to 500 µM). Notably, at 1 µM, ART significantly enhanced SH-SY5Y cell viability to 120% compared to control cells after a 48-hour incubation period (

Figure 2). Additionally, a trend toward increased viability was observed at 10 µM, though this was not statistically significant. Conversely, concentrations at or above 50 µM led to reduced cell viability, with an IC50 of 180 µM. Previous studies on ART's cytotoxicity, including assessments on SH-SY5Y cells, did not report enhanced viability at low doses. In contrast to these studies, the ART treatment time in our study was extended to 48 hours instead of 24 hours. Indeed, no effect was observed after 24 hours of ART treatment. The IC50 for the 24-hour time point was determined as 237 µM. This extended exposure may be key to understanding ART's enhanced viability effect in neuronal-like cells at lower concentrations.

To evaluate whether the observed viability increase with ART is specific to SH-SY5Y cells, we also assessed its effect on HEK-293 and MCF-7 cells (

Figure 2). The IC50 for HEK-293 cells was determined as 242 µM after 24 hours and 232 µM after 48 hours. A notable increase in HEK-293 cell viability was observed following 24-hour treatment at concentrations from 1 to 100 µM, with the peak effect at 1 µM (117% of control). However, after 48 hours, ART no longer had a significant impact on HEK-293 viability. This difference in the time window for stimulatory effects between HEK-293 and SH-SY5Y cells may reflect the shorter division time of HEK-293 cells compared to the slower-dividing SH-SY5Y cells [

22,

23]. Interestingly, no viability increase was observed in MCF-7 cells, regardless of treatment duration. This suggests that ART's stimulatory effect is cell type-specific, enhancing viability in certain cell lines while showing no impact on others.

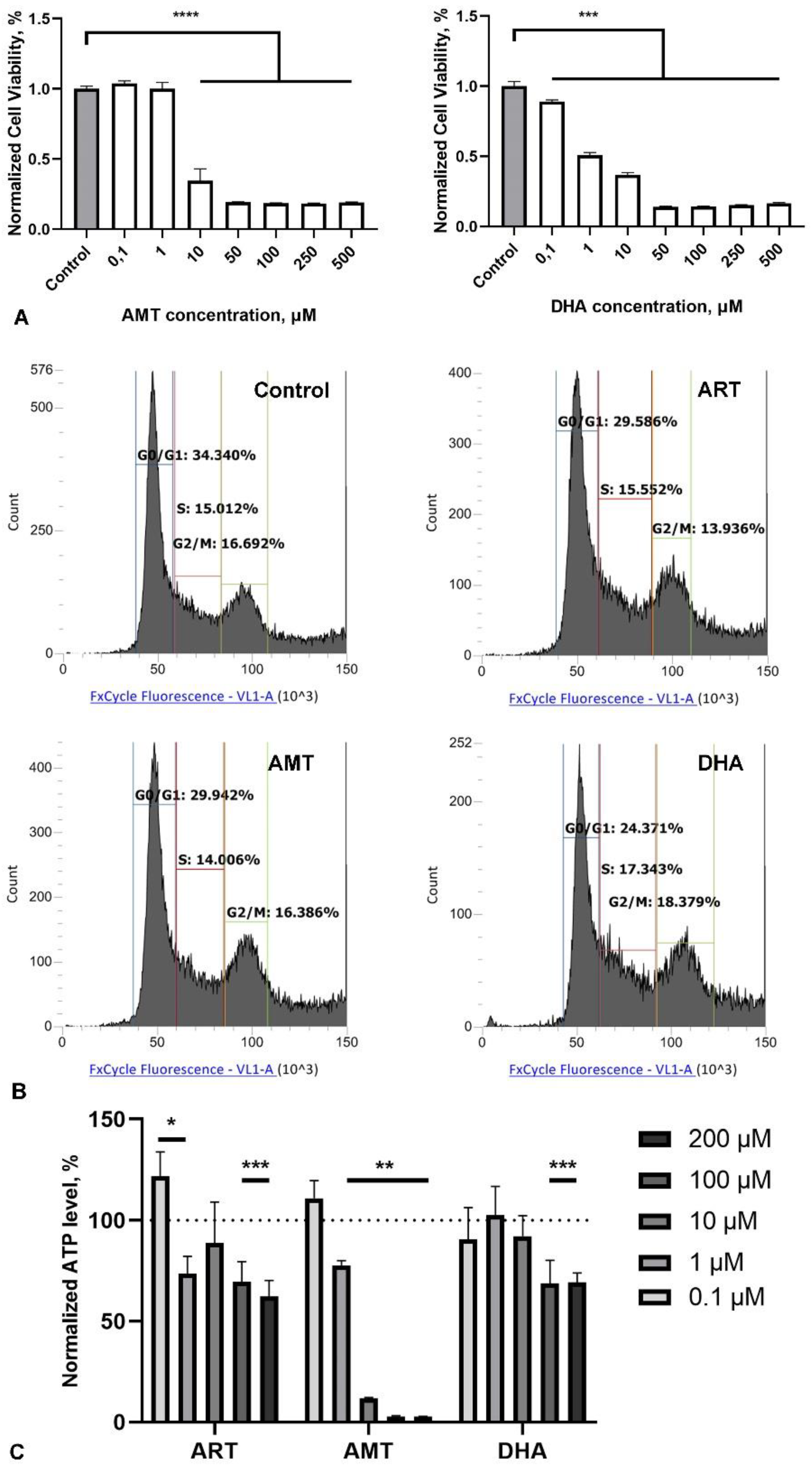

2.3. Artemisinin Does Not Affect the Cell Cycle, but Reduces ATP Levels

We next assessed the impact of ART analogues, modified in the lactone cycle, on SH-SY5Y cell viability. AMT and DHA exhibited high toxicity, with IC50 values of 5 μM and 0.9 μM, respectively (

Figure 3A), while ahDHA showed moderate toxicity with an IC50 of 83 μM (data not shown). None of the tested compounds demonstrated a stimulatory effect at any concentration. These results indicate that the observed effects of ART are closely related to structure-activity relationship.

Assuming that ART may affect cell proliferation, we assessed the distribution of SH-SY5Y cells among cell cycle phases using flow cytometry. Measurement of DNA content allows studying cell populations in different phases of the cell cycle, as well as DNA ploidy analysis. Cells in a given population are typically distributed among three main phases: G0/G1 phase (characterized by one set of paired chromosomes per cell), S phase (where DNA synthesis occurs, resulting in variable DNA content), and G2/M phase (characterized by two sets of paired chromosomes per cell prior to division). During the 48-hour treatment with the selected compounds (1 μM), none of them led to significant changes relative to the control. Histograms of SH-SY5Y cells stained with FxCycle™ dye, showing the distribution of DNA content, are presented in

Figure 3B.

Total cellular ATP level can be used as an interpretation of the biological response when assessing cell viability and proliferation, as well as the cytotoxicity of compounds. We assessed the impact of various concentrations of the compounds on ATP levels in SH-SY5Y cells after a 48-hour treatment. ART caused a slight but consistent reduction in ATP levels at concentrations ranging from 1 to 200 μM. A comparable trend was observed for DHA, while AMT demonstrated a markedly stronger effect, nearly abolishing the cellular energy balance at concentrations starting from 10 μM (

Figure 3C).

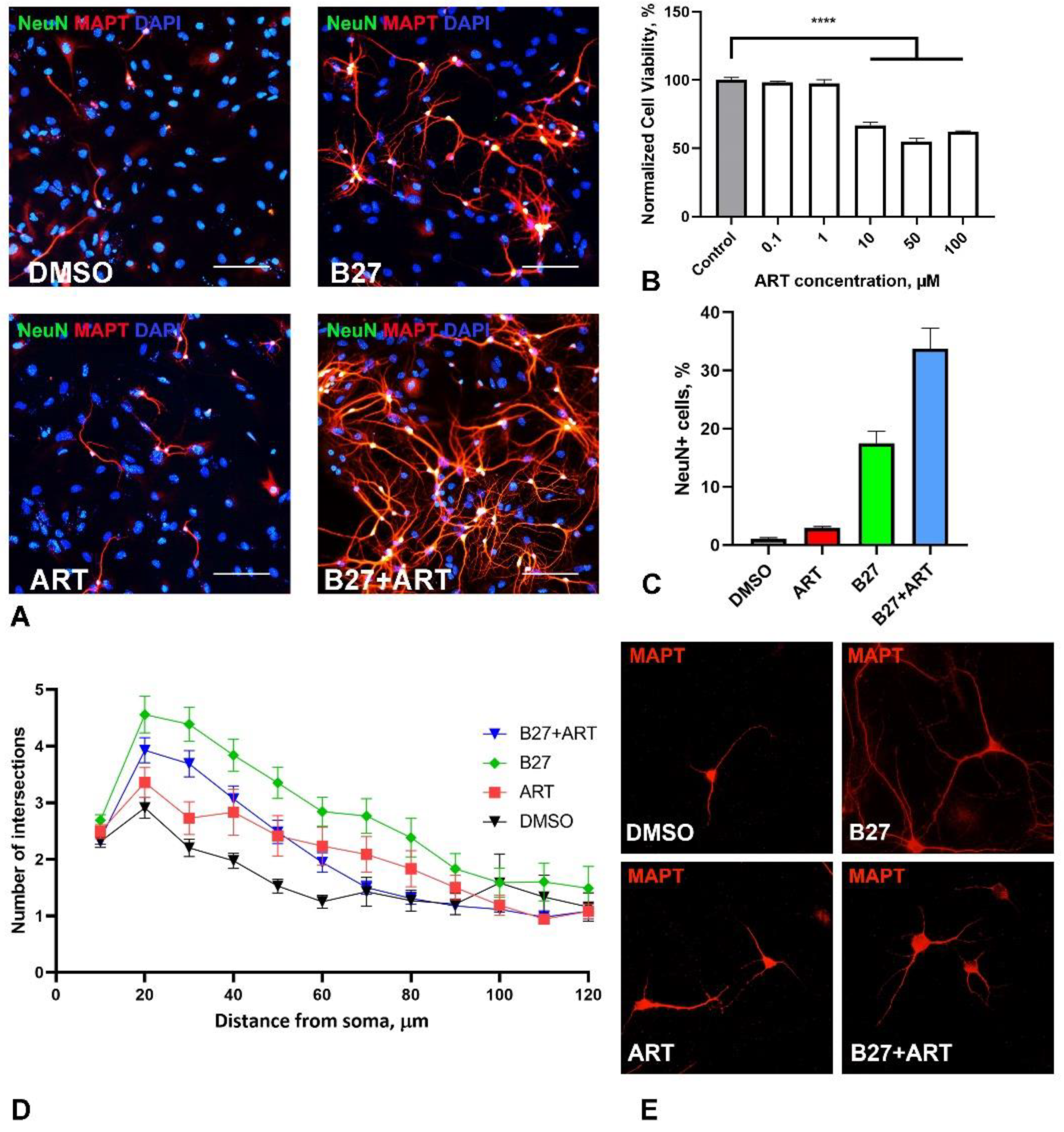

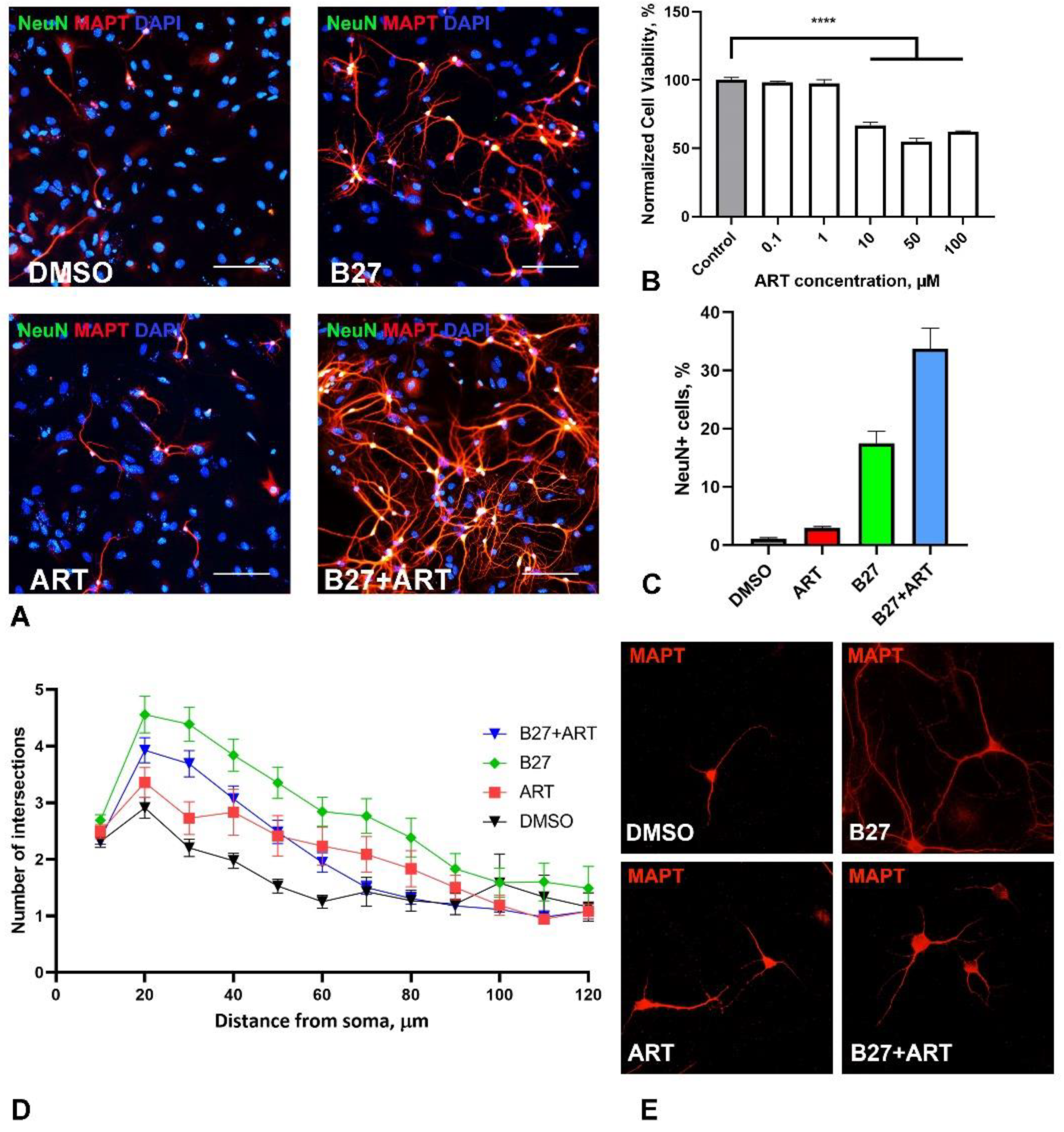

2.4. Artemisinin Increases Survival and Impact Branching of Neurons in Primary Hippocampal Culture

As a more relevant model for the nervous cells, we utilized a mixed neuron-glia murine hippocampal primary culture (

Figure 4A). ART was added to the culture media from the first day of cultivation, with assessments on day 7

in vitro (DIV). In this primary culture, ART showed greater toxicity compared to SH-SY5Y cells, with a significant reduction in cell viability beginning at 10 µM, while 1 µM exhibited no toxic effect (

Figure 4B). Notably, we did not observe any stimulatory effects at any concentration.

We also assessed neuron numbers and neurite arborization in primary culture after 7 days of treatment with 1 µM ART, using Sholl analysis. The standard medium for the primary neuronal culture included B27 supplement, which is known to support neuron survival in culture [

24]. Omitting B27 from the medium resulted in a substantial decline in neuron numbers and reduced branching (

Figure 4C, D, E). Under these suboptimal conditions, ART surprisingly increased both neuron count (using the NeuN marker) and neurite branching. In optimal media containing B27, ART further increased the percentage of neurons in the culture; however, it led to a decrease in neurite branching compared to cultures with B27 alone (

Figure 4C, D, E).

2.5. Artemisinin Protects SH-SY5Y Cells from Stress Induced by the Proteasome Inhibitor MG132

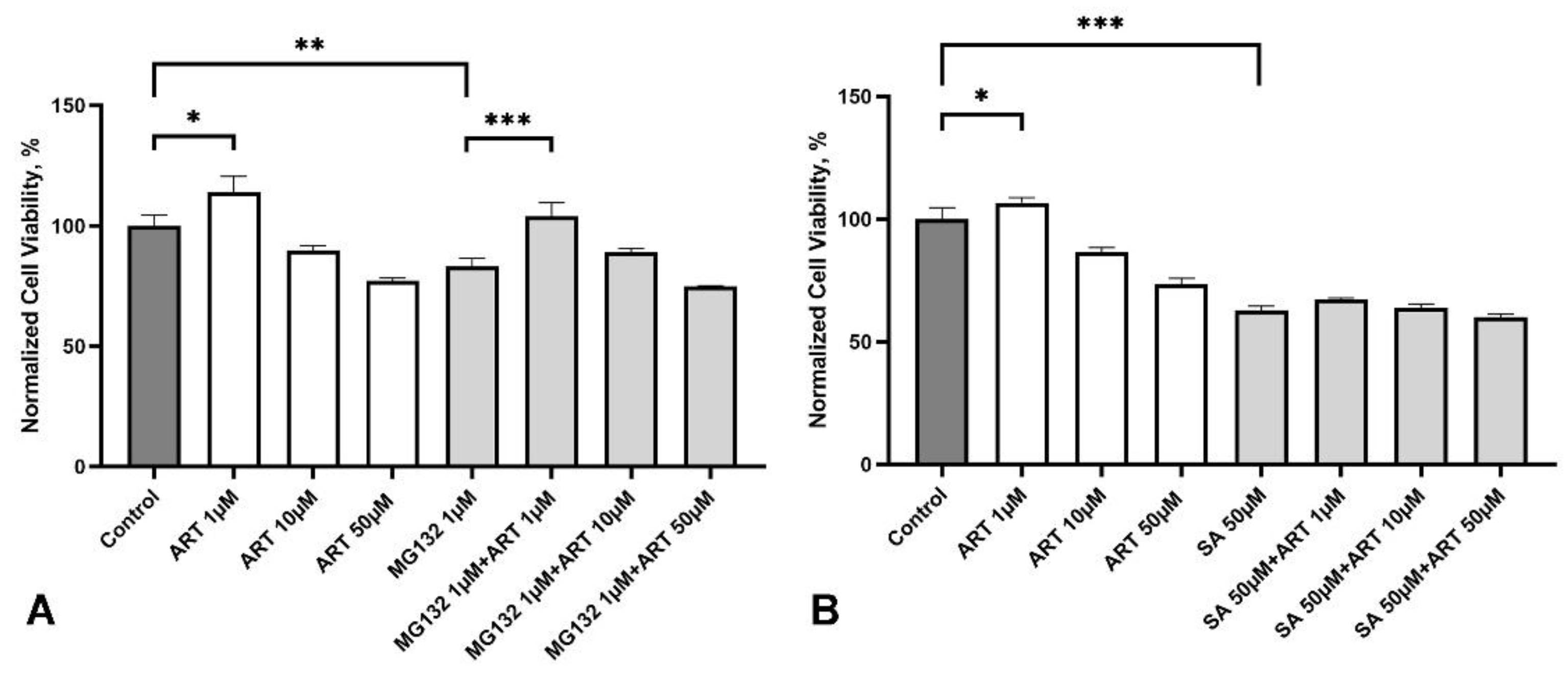

We investigated the potential protective effects of ART against two types of cellular stresses associated with NDDs: ER stress induced by the proteasome inhibitor MG132 and oxidative stress induced by sodium arsenite (SA). SH-SY5Y cells were treated with ART at concentrations of 1, 10, and 50 µM for 48 hours. During the last 24 hours of incubation, 1 µM MG132 or 50 µM SA were added to the media. These stress-inducing treatments reduced cell viability to approximately 80% and 60% of the control group, respectively (

Figure 5A, B).

ART at 1 µM effectively protected cells from MG132-induced stress, restoring viability to levels comparable to the control group (

Figure 5A). Higher concentrations (10 and 50 µM) did not show significant protective effects compared to stressed cells without ART treatment. Notably, ART did not impact cell viability under oxidative stress induced by SA (

Figure 5B), suggesting a specific protective effect of ART against MG132-induced stress.

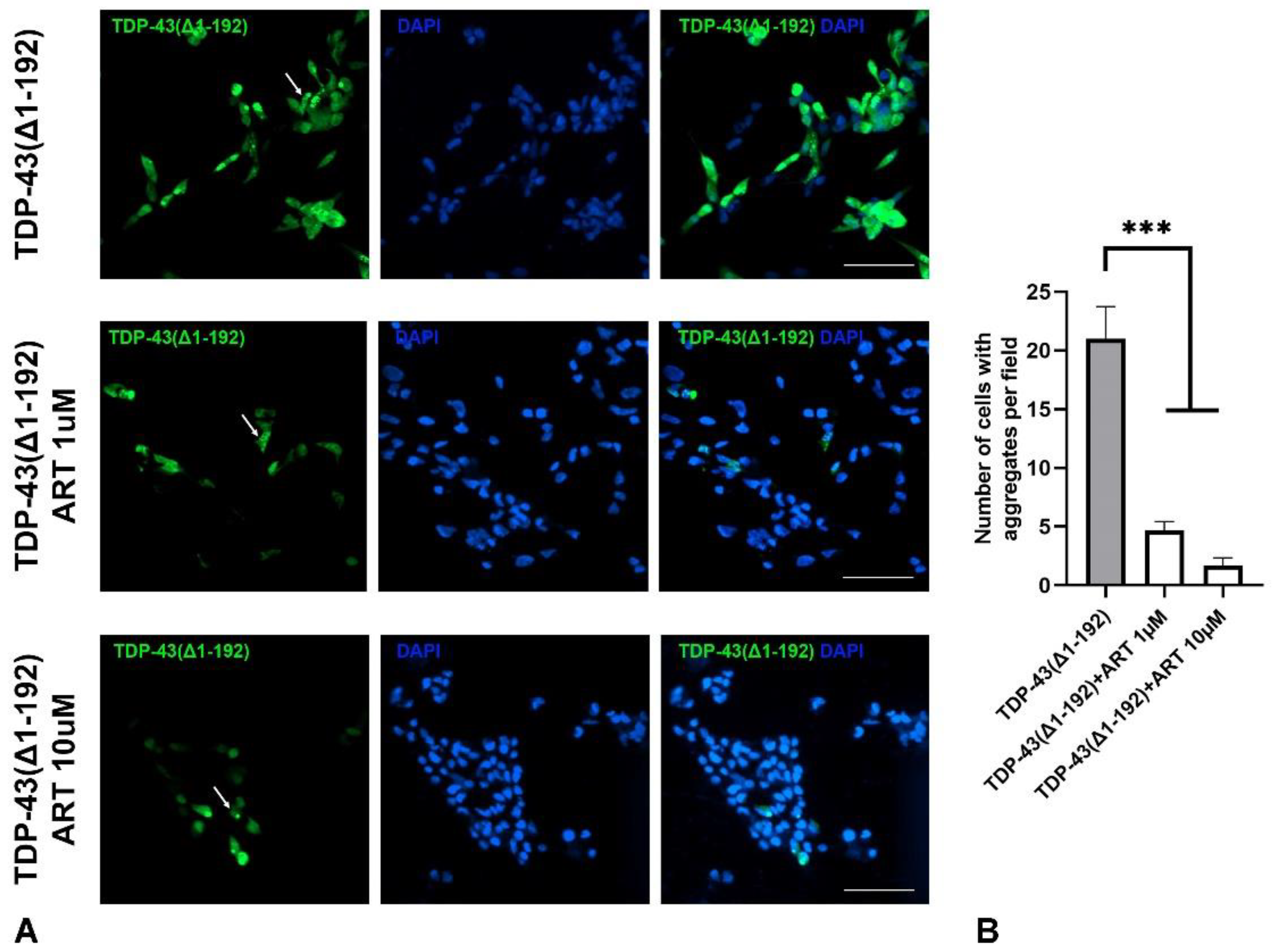

2.6. Artemisinin Inhibits Aggregation of Mutated TDP-43 in SH-SY5Y Cells

ER stress in NDDs is commonly triggered by the accumulation of protein aggregates in neuronal cells. We investigated whether ART could inhibit such protein aggregation. SH-SY5Y cells were transfected with a plasmid encoding the truncated form of TDP-43(Δ1–192), a protein highly prone to aggregation [

25] fused with GFP. In a subset of transfected cells, GFP-TDP-43(Δ1–192) formed medium to large, punctate-like aggregates dispersed throughout the cytoplasm (

Figure 6A upper panel). Cell cultures were treated with 1 µM (

Figure 6A middle panel) or 10 µM (

Figure 6A lower panel) ART 24 hours after transfection, and the number of cells with aggregates was subsequently quantified. ART treatment significantly reduced TDP-43 aggregation at both concentrations (

Figure 6B). Importantly, the total number of cells, as estimated by nuclear DAPI staining, did not differ between treated and untreated cultures, indicating comparable levels of cell death under both conditions. These findings demonstrate that ART is not only protective against ER stress but also reduces the misfolded protein burden contributing to ER stress in NDDs contexts.

3. Discussion

We demonstrated that artemisinin (ART) stimulates viability in the neuronal SH-SY5Y cell line at 1 µM but not in the epithelial-origin MCF-7 cells. Interestingly, ART also stimulated HEK-293 cells, which, though derived from human embryonic kidney cells, are known to express neuronal genes and are believed to have an embryonic neural cell origin [

26,

27,

28]. This suggests that ART's stimulatory effect may be specific to neuronal cell types.

The closest structural derivatives of ART – dihydroartemisinin (DHA) and artemisitene (AMT), despite similar effects of action with the original molecule in other types of activity, they exhibit a high level of cytotoxicity on SH-SY5Y cells (IC50 about 1 and 10 µM, respectively) and we did not find a stimulating effect in the selected concentration range. Probably, the effect of ART is not associated with a direct effect on cell proliferation, since at a stimulating concentration it does not affect the cell cycle. ART reduces the ATP level in SH-SY5Y cells at concentrations of 1-200 µM after 48 hours of incubation, but increased it at concentration of 0.1 µM. These findings indicate that the impact of ART on cellular energy balance may be dynamic and warrants further investigation, particularly by analyzing different time points to elucidate the progression of this process. Although DHA is a known active metabolite of ART, its high cytotoxicity led us to focus exclusively on ART in subsequent analyses.

Further we investigated ART's effects in primary neuronal culture. Because primary neurons are non-dividing, unlike immortalized cell lines such as SH-SY5Y, we adopted a different treatment strategy. Cells were incubated with a non-toxic concentration of ART (1 µM) during the first week of cultivation when neural precursor cells survive and differentiate. ART increased the number of differentiated neurons (marked by NeuN) by up to 3% in non-optimal conditions without B27 supplement, where survival was otherwise low (1%). In optimal conditions with B27, ART raised the proportion of NeuN-positive cells to 33%, compared to 18% in B27-only media. Interestingly, ART also had an ambivalent effect on neurite outgrowth: it promoted branching in B27-lacking conditions but reduced it when B27 was present. Further research is needed to understand how these condition-specific effects may influence neuronal activity. This experiment indicates that prolonged exposure to low-dose ART may enhance neuronal survival and confer protective effects.

Neuroprotection is a key therapeutic strategy for NDDs, where neuronal cell damage and death are prevalent. To further examine ART's neuroprotective potential, we investigated its effects on cellular pathologies associated with neurodegeneration. Extracts of

Artemisia annua L. and its main component, ART, are known for their antioxidant properties [

29,

30,

31]. ART has also been shown to protect SH-SY5Y cells from oxidative stress induced by H

2O

2 [

3]. In this work authors do not note a stimulatory effect of ART on the SH-SY5Y cell line (the authors limits to only a 24-hour experiment). However, it was shown that ART attenuated the decrease in cell viability induced by H

2O

2 in SH-SY5Y cells (pretreatment for 2 hours, exposure to H

2O

2 for 24 hours). However, in this study, we found that ART did not protect against oxidative stress induced by SA (pretreatment for 24 hours, exposure to SA for additional 24 hours), another inducer of oxidative damage. This discrepancy may arise from differences in the mechanisms and signaling pathways activated by H

2O

2 and SA and also due to different time of treatment [

32].

We further demonstrated that ART at 1 µM, the same concentration that stimulated SH-SY5Y cells, protected them from ER stress induced by the proteasome inhibitor MG132. Interestingly, higher concentrations (10 and 50 µM) did not have this protective effect, although a slight non-significant increase in viability was observed at 10 µM. A biphasic, dose-dependent response has also been reported with ART analogs in other studies. For example, high doses of artemether and artesunate caused neurotoxicity or mortality in Swiss albino mice [

33], and artesunate exhibited cardiotoxicity at high doses but conferred cardioprotective effects at low doses in zebrafish [

34]. Similarly, we observed that high concentrations of ART (IC50 180 µM) were toxic to SH-SY5Y cells, whereas lower concentrations (1 µM) were beneficial.

The evidence suggests that DHA, the active form of ART, triggers an unfolded protein response (UPR) in the malaria-causing

Plasmodium falciparum, elevating eIF2α phosphorylation and inhibiting proteasome function. This response underpins ART’s effectiveness in malaria treatment [

35]. In ART-resistant strains, over-activation of the ubiquitin-proteasomal and autophagic pathways further supports the involvement of these stress response mechanisms in ART’s action [

36,

37,

38]. It is plausible that low doses of ART or its analogs partially engage stress response mechanisms, thus reinforcing cellular resilience to more severe stress. This hypothesis may explain the cytoprotective effects observed in neuronal cells in our

in vitro experiments, though further study is needed to fully elucidate this potential mechanism in neuroprotection.

Multiple studies indicate that ART and its analogs inhibit protein aggregation in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), where they reduce amyloid deposits in the cortex and hippocampus, with a greater effect observed at lower doses (10 mg/kg compared to 100 mg/kg) [

39,

40,

41]. Our findings extend this anti-aggregation potential to TDP-43, a protein implicated in NDDs such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia [

42,

43]. In SH-SY5Y cells transfected with the pathogenic TDP-43(Δ1-192) variant, ART at 1 and 10 µM significantly reduced the proportion of cells with visible aggregates. This highlights ART’s broader potential to target pathogenic protein aggregation beyond amyloid in AD models.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Compounds

ART and DHA was obtained from commercial sources (Shanghai Huirui Chemical Technology, China and Greenherb Biological Technology (Xi'an), China). ART derivatives ahDHA and AMT were prepared as described previously [

20]. All compounds were consistent with those described in the literature.

4.2. Stable Cell Lines, Cell Viability Assay

HEK293 and MCF-7 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, Paneco, Russia), SH-SY5Y cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 medium (Paneco, Russia) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Biosera, France) and 2 mM L-glutamine (Paneco, Russia). All cells were incubated at 37° C in a humidified 5% CO₂ atmosphere. Cell lines were obtained from the Laboratory of the genetics of tumor cells at the N.N. Blokhin Russian cancer research center (Moscow, Russia) and the Institute of cytology, Russian academy of sciences (Saint Petersburg, Russia).

Cell viability was assessed using the MTS Assay Kit (Abcam, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were plated in 96-well plates at a density of 1×10⁴ cells in 100 µL of medium. After 24 hours, testing compounds were added (the final concentrations were 500, 250, 125, 62.5, 2, 1 and 0.5 μM for ART and ahDHA; 20, 10, 5, 2.5, 1.25, 0.625 and 0.3125 for AMT and DHA), bringing the final volume per well to 200 µL. Cells were incubated for an additional 24 or 48 hours under the same conditions. All compounds were dissolved in DMSO, ensuring a final concentration not exceeding 0.5% DMSO, which did not induce cytotoxic effects. Control wells received an equivalent concentration of DMSO. After incubation, 20 µL of MTS reagent was added to each well, and plates were incubated for 1–2 hours. Optical density was measured at 490 nm using a Feyond-A300 Microplate Reader (Allsheng, China). IC50 values were calculated based on dose-response curves using GraphPad Prism 8 software (GraphPad Software, USA). Cell viability in control wells was set to 100%.

The protective effect against stress was determined using the MTS assay as mentioned above. Cells were seeded in a 96-well plate at 1×104 cells/100 μl complete growth medium and cultured at 37° C under CO2 (5%). After 24 hours of incubation, ART was added to the cells (final concentrations were 50, 10 and 1 μM) by replacing 50% of the medium with a final volume of 100 μl/well. After 24 hours of cultivation with ART, MG132 and NaAsO2 (SA) solutions in the growth medium with a final content of 1 and 50 μM, respectively, were added to the cells, and the initial concentration of ART was maintained. For each concentration, the experiment included three replicates. All substances were dissolved in DMSO, the final DMSO content in the well did not exceed 0.5% and did not have a toxic effect. The solvent was added to the control wells in a volume of 0.5% (positive control – treatment with MG132 and NaAsO2, additional control – treated only with ART). After another 24 hours of incubation, 20 μl of MTS reagent were added to each well, and the plates were further incubated for 1-2 hours.

A plasmid vector encoding a mutant form of TDP-43 protein (Δ1–192) with a GFP tag was provided by Prof. V. Buchman. SH-SY5Y cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (ThermoScientific, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Twenty-four hours post-transfection, cells were fixed and stained with DAPI (Sigma Aldrich, USA) for nuclear visualization.

4.3. Cell Cycle Analysis

Flow cytometry was used to assess the effect of the test compounds on the cell cycle of SH-SY5Y cells. Cells were seeded in a 12-well plate (1×106 cells in 2000 µl) and solutions of the test compounds were added (final concentrations was 1 μM), then incubated for 48 hours. FxCycle™ Violet Stain (ThermoScientific, USA) reagent was used in the experiment. Cell material was prepared according to the reagent manufacturer's instructions, cells were fixed with cold ethanol (70%) for 15 minutes and washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Then they were analyzed using an Attune NxT Acoustic Focusing Cytometer using a 405 nm laser with a 440/50 bandpass filter to achieve 50,000 events at a standard flow rate of 100 µl/min.

4.4. ATP Level Assessment

Cells were seeded in a 96-well plate at 2,5×104 cells/100 μl of complete growth medium and cultured at 37° C in a CO2 atmosphere (5%). After 24 hours of incubation, the medium was removed and the studied compounds were added to the cells (final concentrations were 200, 100, 10, 1, 0.5 and 0.1 μM) with a final volume of 100 μl/well and then the cells were cultured under the same conditions for 48 hours. For each concentration, the experiment included three replicates. All substances were dissolved in DMSO, the final DMSO content in the well did not exceed 0.2%. The solvent was added to the control wells in a volume of 0.2%. After 48 hours, the cell material was prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions for the Luminescent ATP Detection Assay Kit (Abcam, USA), and luminescence in the wells was determined using a Cytation3 imaging reader (BioTek, USA).

4.5. Primary Hippocampal Cultures

Primary neuronal cultures were prepared from wild-type C57Bl/6J mice on postnatal day 3 (P3) as previously described [

44]. Animals were housed under standard conditions, with a 12-hour light/dark cycle and free access to food and water. Following dissection, hippocampi were incubated in 0.1% trypsin in Hank's Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS, Paneco, Russia) containing 10 mM HEPES (4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid, Paneco, Russia) and 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Paneco, Russia) for 40 minutes. Mechanical dissociation was performed in Neurobasal medium (Paneco, Russia) supplemented with 50 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin, 0.2% β-mercaptoethanol, 500 μM L-glutamine, 0.36% glucose, and 10% horse serum (Paneco, Russia).

Hippocampal cells were then centrifuged at 1,500 rpm for 5 minutes, and the pellet was resuspended in freshly prepared medium. To support neuronal survival, B27 supplement (ThermoScientific, USA) was added according to the experiment design. Cells were plated onto 12-mm diameter poly-L-lysine-coated coverslips at a density of 3×10⁴ cells per coverslip. The following day, the medium was replaced with serum-free fresh medium, and half of the medium was subsequently replaced every three days. Cells were fixed and stained on day 7 in vitro. On the first day in vitro, ART dissolved in DMSO (Paneco, Russia) was added to a final concentration of 1 μM, which was maintained throughout the culture period.

4.6. Immunocytochemical Staining

Cells were rinsed with 1x PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes, followed by permeabilization with cold methanol for 5 minutes. After washing with PBS and blocking in 5% goat serum in PBS with 0.1% Tween-20 for 60 minutes at room temperature, coverslips were incubated with primary antibodies against Tau (1:1000, SAB4300377, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and NeuN (1:1000; MAB377, Millipore, USA) for 60 minutes at room temperature. Cells were then incubated with secondary antibodies Goat anti-Rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor™ 568 (A-11011, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and Goat anti-Mouse IgG Alexa Fluor™ 488 (A-11029, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) in PBS with 0.4% Tween-20 for 90 minutes at room temperature. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). Coverslips were mounted onto slides with Immu-Mount medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Stained coverslips were imaged using the Cytation3 imaging reader and Gen5 3.08 software (BioTek, USA). An area of 3000×3000 µm was scanned in multi-channel fluorescence mode, stitched into a single panoramic image, and analyzed for cell counts stained with specific markers. Results for each marker were normalized to the total cell count, as determined by DAPI-stained nuclei. To assess neurite branching in primary neurons, microphotographs were captured with a Carl Zeiss Axio Observer 3 microscope equipped with an Axiocam 712 mono camera (Carl Zeiss, Germany). Semi-automated Sholl analysis was conducted in ImageJ as previously described [

45], with a total of 60 neurons analyzed per group.

4.7. Statistical Analysis

Statistical data analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 8 software (GraphPad Software, USA). In all cases, the results are presented as the mean ± standard error. Details of the statistical analysis for each dataset are presented in the figure legends. Differences between groups were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S.K., S.A.P. and S.O.B.; methodology, A.V.S and N.E.P.; validation, V.S.K. and M.S.K.; formal analysis, M.S.K.; investigation, N.E.P., O.A.K. and T.V.I.; resources, M.S.K. and S.O.B.; data curation, M.S.K.; writing—original draft preparation, S.A.P. and M.S.K; writing—review and editing, S.A.P. and M.S.K; visualization, N.E.P.; supervision, M.S.K. and S.O.B.; funding acquisition, M.S.K. and S.O.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the budget of the IPAC RAS State Target (№FFSG-2024-0023).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the local Institute Ethics Review Committee of the IPAC RAS (protocol No. 53, 18 December 2023). All animal work was carried out in accordance with the “Guidelines for accommodation and care of animals. Species-specific provisions for laboratory rodents and rabbits” (GOST 33216-2014) in compliance with the principles enunciated in the Directive 2010/63/EU on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the current article and its supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

Research was supported in the frame of the Agreement with the Ministry of science and higher education № 075-15-2024-627 of July 12, 2024.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Tu, Y. The discovery of artemisinin (qinghaosu) and gifts from Chinese medicine. Nature medicine 2011, 17, 1217–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Z.; Xu, J.; Zheng, W. Artemisinin protects PC12 cells against beta-amyloid-induced apoptosis through activation of the ERK1/2 signaling pathway. Redox biology 2017, 12, 625–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Fang, J.; Li, S.; Gaur, U.; Xing, X.; Wang, H.; Zheng, W. Artemisinin Attenuated Hydrogen Peroxide (H(2)O(2))-Induced Oxidative Injury in SH-SY5Y and Hippocampal Neurons via the Activation of AMPK Pathway. International journal of molecular sciences 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.; Li, W.; Lv, R.; Zhang, M.; Liu, W. Neuroprotective effects and mechanisms of action of artemisinin in retinal ganglion cells in a mouse model of traumatic optic neuropathy. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.Y.; Ho, L.Y.; Ren, Z.H.; Song, Z.Y. Metabolic fate of Qinghaosu in rats; a new TLC densitometric method for its determination in biological material. European journal of drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics 1985, 10, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, T.M.; Binh, T.Q.; Ilett, K.F.; Batty, K.T.; Phuong, H.L.; Chiswell, G.M.; Phuong, V.D.; Agus, C. Penetration of dihydroartemisinin into cerebrospinal fluid after administration of intravenous artesunate in severe falciparum malaria. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy 2003, 47, 368–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Chong, C.M.; Wang, H.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, L.; Wang, R.; Meng, Q.; Lazarovici, P.; Fang, J. Artemisinin conferred ERK mediated neuroprotection to PC12 cells and cortical neurons exposed to sodium nitroprusside-induced oxidative insult. Free radical biology & medicine 2016, 97, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, S.; Fang, J.; Yang, C.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, W.; Zheng, W. Artemisinin Confers Neuroprotection against 6-OHDA-Induced Neuronal Injury In Vitro and In Vivo through Activation of the ERK1/2 Pathway. Molecules 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.P.; Li, W.; Winters, A.; Liu, R.; Yang, S.H. Artemisinin Prevents Glutamate-Induced Neuronal Cell Death Via Akt Pathway Activation. Frontiers in cellular neuroscience 2018, 12, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Ma, H.; Lai, X.; Wu, J.; Liu, A.; Huang, J.; Sun, W.; Shen, M.; Zhang, Y. Artemisinin attenuated oxidative stress and apoptosis by inhibiting autophagy in MPP(+)-treated SH-SY5Y cells. Journal of biological research 2021, 28, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.S.; Park, G. Artemisinin protects dopaminergic neurons against 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-induced neurotoxicity in a mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie 2024, 170, 115972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.Q.; Zhang, C.C.; Sun, X.L.; Cheng, X.X.; Wang, J.B.; Zhang, Y.D.; Xu, J.; Zou, H.Q. Antimalarial drug artemisinin extenuates amyloidogenesis and neuroinflammation in APPswe/PS1dE9 transgenic mice via inhibition of nuclear factor-kappaB and NLRP3 inflammasome activation. CNS neuroscience & therapeutics 2013, 19, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Li, S.; Gaur, U.; Zheng, W. Artemisinin Improved Neuronal Functions in Alzheimer's Disease Animal Model 3xtg Mice and Neuronal Cells via Stimulating the ERK/CREB Signaling Pathway. Aging and disease 2020, 11, 801–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiss, E.; Kins, S.; Gorgas, K.; Venczel Szakacs, K.H.; Kirsch, J.; Kuhse, J. Another Use for a Proven Drug: Experimental Evidence for the Potential of Artemisinin and Its Derivatives to Treat Alzheimer's Disease. International journal of molecular sciences 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetz, C.; Saxena, S. ER stress and the unfolded protein response in neurodegeneration. Nature reviews. Neurology 2017, 13, 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindholm, D.; Wootz, H.; Korhonen, L. ER stress and neurodegenerative diseases. Cell death and differentiation 2006, 13, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Wei, T.; Ju, F.; Li, H. Protein quality control and aggregation in the endoplasmic reticulum: From basic to bedside. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology 2023, 11, 1156152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brossi, A.; Venugopalan, B.; Dominguez Gerpe, L.; Yeh, H.J.; Flippen-Anderson, J.L.; Buchs, P.; Luo, X.D.; Milhous, W.; Peters, W. Arteether, a new antimalarial drug: synthesis and antimalarial properties. Journal of medicinal chemistry 1988, 31, 645–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuma, N.H.; Smit, F.J.; de Kock, C.; Combrinck, J.; Smith, P.J.; N'Da, D.D. Synthesis and biological evaluation of a series of non-hemiacetal ester derivatives of artemisinin. European journal of medicinal chemistry 2016, 122, 635–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semakov, A.V.; Anikina, L.V.; Klochkov, S.G. Synthesis and Cytotoxic Activity of the Products of Addition of Thiophenol to Sesquiterpene Lactones. Russian Journal of Bioorganic Chemistry 2021, 47, 906–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Feraly, F.S.; Ayalp, A.; Al-Yahya, M.A.; McPhail, D.R.; McPhail, A.T. Conversion of Artemisinin to Artemisitene. Journal of Natural Products 1990, 53, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervera, L.; Gutierrez, S.; Godia, F.; Segura, M.M. Optimization of HEK 293 cell growth by addition of non-animal derived components using design of experiments. BMC proceedings 2011, 5 Suppl 8, P126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feles, S.; Overath, C.; Reichardt, S.; Diegeler, S.; Schmitz, C.; Kronenberg, J.; Baumstark-Khan, C.; Hemmersbach, R.; Hellweg, C.E.; Liemersdorf, C. Streamlining Culture Conditions for the Neuroblastoma Cell Line SH-SY5Y: A Prerequisite for Functional Studies. Methods and protocols 2022, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brewer, G.J.; Torricelli, J.R.; Evege, E.K.; Price, P.J. Optimized survival of hippocampal neurons in B27-supplemented Neurobasal, a new serum-free medium combination. Journal of neuroscience research 1993, 35, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.T.; Kuo, P.H.; Chiang, C.H.; Liang, J.R.; Chen, Y.R.; Wang, S.; Shen, J.C.; Yuan, H.S. The truncated C-terminal RNA recognition motif of TDP-43 protein plays a key role in forming proteinaceous aggregates. The Journal of biological chemistry 2013, 288, 9049–9057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Soderlund, D.M. Human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cells express endogenous voltage-gated sodium currents and Na v 1.7 sodium channels. Neuroscience letters 2010, 469, 268–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, G.; Morse, S.; Ararat, M.; Graham, F.L. Preferential transformation of human neuronal cells by human adenoviruses and the origin of HEK 293 cells. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology 2002, 16, 869–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhusudana, S.N.; Sundaramoorthy, S.; Ullas, P.T. Utility of human embryonic kidney cell line HEK-293 for rapid isolation of fixed and street rabies viruses: comparison with Neuro-2a and BHK-21 cell lines. International journal of infectious diseases : IJID : official publication of the International Society for Infectious Diseases 2010, 14, e1067–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed-Laloui, H.; Zaak, H.; Rahmani, A.; Kashi, I.; Chemat, S.; Miara, M.D.; Cherb, N.; Derdour, M. Assessment of artemisinin and antioxidant activities of three wild Artemisia species of Algeria. Natural product research 2022, 36, 6344–6352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebbac, K.; Benziane Ouaritini, Z.; El Moussaoui, A.; Chalkha, M.; Lafraxo, S.; Bin Jardan, Y.A.; Nafidi, H.A.; Bourhia, M.; Guemmouh, R. Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Properties of Chemically Analyzed Essential Oil of Artemisia annua L. (Asteraceae) Native to Mediterranean Area. Life 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.F.S.; Zheljazkov, V.D.; Gonzalez, J.M. Artemisinin concentration and antioxidant capacity of Artemisia annua distillation byproduct. Industrial Crops and Products 2013, 41, 294–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Gabriel, M.A.; Russell, P. Distinct signaling pathways respond to arsenite and reactive oxygen species in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Eukaryotic cell 2005, 4, 1396–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nontprasert, A.; Pukrittayakamee, S.; Nosten-Bertrand, M.; Vanijanonta, S.; White, N.J. Studies of the neurotoxicity of oral artemisinin derivatives in mice. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene 2000, 62, 409–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, C.; Shan, L.; Tong, P.; Efferth, T. Cardiotoxicity and Cardioprotection by Artesunate in Larval Zebrafish. Dose-response : a publication of International Hormesis Society 2020, 18, 1559325819897180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bridgford, J.L.; Xie, S.C.; Cobbold, S.A.; Pasaje, C.F.A.; Herrmann, S.; Yang, T.; Gillett, D.L.; Dick, L.R.; Ralph, S.A.; Dogovski, C.; et al. Artemisinin kills malaria parasites by damaging proteins and inhibiting the proteasome. Nature communications 2018, 9, 3801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogovski, C.; Xie, S.C.; Burgio, G.; Bridgford, J.; Mok, S.; McCaw, J.M.; Chotivanich, K.; Kenny, S.; Gnadig, N.; Straimer, J.; et al. Targeting the cell stress response of Plasmodium falciparum to overcome artemisinin resistance. PLoS biology 2015, 13, e1002132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, S.; Ashley, E.A.; Ferreira, P.E.; Zhu, L.; Lin, Z.; Yeo, T.; Chotivanich, K.; Imwong, M.; Pukrittayakamee, S.; Dhorda, M.; et al. Drug resistance. Population transcriptomics of human malaria parasites reveals the mechanism of artemisinin resistance. Science 2015, 347, 431–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, D.; Joshi, N.; Gupta, S.; Pati, S.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Langsley, G.; Singh, S. Cytoprotective autophagy as a pro-survival strategy in ART-resistant malaria parasites. Cell death discovery 2023, 9, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, E.; Kins, S.; Zoller, Y.; Schilling, S.; Gorgas, K.; Gross, D.; Schlicksupp, A.; Rosner, R.; Kirsch, J.; Kuhse, J. Artesunate restores the levels of inhibitory synapse proteins and reduces amyloid-beta and C-terminal fragments (CTFs) of the amyloid precursor protein in an AD-mouse model. Molecular and cellular neurosciences 2021, 113, 103624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisler, K.; Sagare, A.P.; Lazic, D.; Bazzi, S.; Lawson, E.; Hsu, C.J.; Wang, Y.; Ramanathan, A.; Nelson, A.R.; Zhao, Z.; et al. Anti-malaria drug artesunate prevents development of amyloid-beta pathology in mice by upregulating PICALM at the blood-brain barrier. Molecular neurodegeneration 2023, 18, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, M.; Xiang, W.; Chen, Y.; Peng, N.; Du, X.; Lu, S.; Zuo, Y.; Li, B.; Hu, Y.; Li, X. DHA Ameliorates Cognitive Ability, Reduces Amyloid Deposition, and Nerve Fiber Production in Alzheimer's Disease. Frontiers in nutrition 2022, 9, 852433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Boer, E.M.J.; Orie, V.K.; Williams, T.; Baker, M.R.; De Oliveira, H.M.; Polvikoski, T.; Silsby, M.; Menon, P.; van den Bos, M.; Halliday, G.M.; et al. TDP-43 proteinopathies: a new wave of neurodegenerative diseases. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry 2020, 92, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, M.; Lee, S.; Jeon, Y.M.; Kim, S.; Kwon, Y.; Kim, H.J. The role of TDP-43 propagation in neurodegenerative diseases: integrating insights from clinical and experimental studies. Experimental & molecular medicine 2020, 52, 1652–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukharsky, M.S.; Quintiero, A.; Matsumoto, T.; Matsukawa, K.; An, H.; Hashimoto, T.; Iwatsubo, T.; Buchman, V.L.; Shelkovnikova, T.A. Calcium-responsive transactivator (CREST) protein shares a set of structural and functional traits with other proteins associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Molecular neurodegeneration 2015, 10, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukharsky, M.S.; Ninkina, N.N.; An, H.; Telezhkin, V.; Wei, W.; Meritens, C.R.; Cooper-Knock, J.; Nakagawa, S.; Hirose, T.; Buchman, V.L.; et al. Long non-coding RNA Neat1 regulates adaptive behavioural response to stress in mice. Translational psychiatry 2020, 10, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Structure of artemisinin and its derivatives.

Figure 1.

Structure of artemisinin and its derivatives.

Figure 2.

Viability of SH-SY5Y, HEK-293 and MCF-7 cells 24 hours and 48 hours after treatment with artemisinin (ART) across a range of micromolar concentrations measured by MTS assay. Statistical analysis was performed using ANOVA followed by Fisher's LSD test for multiple comparisons between groups, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, **** p < 0.0001 compared to control.

Figure 2.

Viability of SH-SY5Y, HEK-293 and MCF-7 cells 24 hours and 48 hours after treatment with artemisinin (ART) across a range of micromolar concentrations measured by MTS assay. Statistical analysis was performed using ANOVA followed by Fisher's LSD test for multiple comparisons between groups, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, **** p < 0.0001 compared to control.

Figure 3.

Effect of artemisinin (ART) and its derivatives artemisitene (AMT) and dihydroartemisinin (DHA) on SH-SY5Y cells viability, proliferation and ATP level. A. Viability of SH-SY5Y cells 48 hours after treatment with tested compounds across a range of micromolar concentrations measured by MTS assay. Statistical analysis was performed using ANOVA followed by Fisher's LSD test for multiple comparisons between groups, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001 compared to control. B. Representative histograms of untreated cells and 48 hours after incubation with the tested compounds in concentration of 1 μM. C. ATP level in SH-SY5Y cells relative to control 48 hours after incubation with the tested compounds in concentration of 1 μM. Statistical analysis was performed using Two-way ANOVA followed by Fisher's LSD test for multiple comparisons between groups, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 compared to control.

Figure 3.

Effect of artemisinin (ART) and its derivatives artemisitene (AMT) and dihydroartemisinin (DHA) on SH-SY5Y cells viability, proliferation and ATP level. A. Viability of SH-SY5Y cells 48 hours after treatment with tested compounds across a range of micromolar concentrations measured by MTS assay. Statistical analysis was performed using ANOVA followed by Fisher's LSD test for multiple comparisons between groups, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001 compared to control. B. Representative histograms of untreated cells and 48 hours after incubation with the tested compounds in concentration of 1 μM. C. ATP level in SH-SY5Y cells relative to control 48 hours after incubation with the tested compounds in concentration of 1 μM. Statistical analysis was performed using Two-way ANOVA followed by Fisher's LSD test for multiple comparisons between groups, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 compared to control.

Figure 4.

Effect of artemisinin (ART), B27 supplement and their combination (B27+ART) on primary hippocampal culture. A. Representative micrographs showing immunohistochemical staining of primary neurons (NeuN) and their neurites (MAPT) in cultures incubated with DMSO (control), ART, B27 and B27+ART for first 7 days in vitro. Cell nuclei were stained using DAPI. The scale bar: 100 μm. B. Viability of primary cultures treated with ART across a range of micromolar concentrations, measured by the MTS assay. Statistical analysis was performed using ANOVA followed by Fisher's LSD test for multiple comparisons between groups, **** p < 0.0001 compared to control. C. Quantification of neuronal number (NeuN-positive cells) under different incubation conditions (DMSO, ART, B27, and B27+ART) in the same cultures shown in panel A. D. Sholl analysis of primary neurons under different incubation conditions, showing the number of neurite intersections with 10-μm spaced concentric shells as a function of the radial distance from the soma. E. Representative micrographs of MAPT-stained primary neurons used for Sholl analysis.

Figure 4.

Effect of artemisinin (ART), B27 supplement and their combination (B27+ART) on primary hippocampal culture. A. Representative micrographs showing immunohistochemical staining of primary neurons (NeuN) and their neurites (MAPT) in cultures incubated with DMSO (control), ART, B27 and B27+ART for first 7 days in vitro. Cell nuclei were stained using DAPI. The scale bar: 100 μm. B. Viability of primary cultures treated with ART across a range of micromolar concentrations, measured by the MTS assay. Statistical analysis was performed using ANOVA followed by Fisher's LSD test for multiple comparisons between groups, **** p < 0.0001 compared to control. C. Quantification of neuronal number (NeuN-positive cells) under different incubation conditions (DMSO, ART, B27, and B27+ART) in the same cultures shown in panel A. D. Sholl analysis of primary neurons under different incubation conditions, showing the number of neurite intersections with 10-μm spaced concentric shells as a function of the radial distance from the soma. E. Representative micrographs of MAPT-stained primary neurons used for Sholl analysis.

Figure 5.

Effect of artemisinin (ART) on viability of SH-SY5Y cells under stress conditions. A. Viability of SH-SY5Y cells treated with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (1 μM) and ART at the indicated concentrations, measured using the MTS assay. B. Viability of SH-SY5Y cells exposed to oxidative stress induced by sodium arsenite (SA, 50 μM) and ART at the indicated concentrations, measured using the MTS assay. Statistical analysis was performed using ANOVA followed by Fisher's LSD test for multiple comparisons between groups, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 compared to control.

Figure 5.

Effect of artemisinin (ART) on viability of SH-SY5Y cells under stress conditions. A. Viability of SH-SY5Y cells treated with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (1 μM) and ART at the indicated concentrations, measured using the MTS assay. B. Viability of SH-SY5Y cells exposed to oxidative stress induced by sodium arsenite (SA, 50 μM) and ART at the indicated concentrations, measured using the MTS assay. Statistical analysis was performed using ANOVA followed by Fisher's LSD test for multiple comparisons between groups, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 compared to control.

Figure 6.

Effect of artemisinin (ART) on the aggregation of mutated TDP-43(Δ1–192) protein in SH-SY5Y cells. A. Representative micrographs of SH-SY5Y cells transfected with GFP-tagged TDP-43(Δ1–192) protein and treated with ART at indicated concentrations. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI. The scale bar: 50 μm. B. Quantification of the number of cells with aggregates in SH-SY5Y cultures transfected with TDP-43(Δ1–192) and treated with ART. Statistical analysis was performed using ANOVA followed by Fisher's LSD test for multiple comparisons between groups, *** p < 0.001 compared to control group without ART treatment.

Figure 6.

Effect of artemisinin (ART) on the aggregation of mutated TDP-43(Δ1–192) protein in SH-SY5Y cells. A. Representative micrographs of SH-SY5Y cells transfected with GFP-tagged TDP-43(Δ1–192) protein and treated with ART at indicated concentrations. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI. The scale bar: 50 μm. B. Quantification of the number of cells with aggregates in SH-SY5Y cultures transfected with TDP-43(Δ1–192) and treated with ART. Statistical analysis was performed using ANOVA followed by Fisher's LSD test for multiple comparisons between groups, *** p < 0.001 compared to control group without ART treatment.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).