1. Introduction

Gravitational lensing is a well-known astronomical phenomena that affects our view of the distant Universe[

49].This type of lensing occurs when light rays pass through the curved spacetime produced by a massive object [

30]. It produces images on a variety of scales [

4] and provides awe-inspiring views of distant cosmic vistas as if seen in the distorted glass of a funhouse mirror [

48].

While gravitational lensing is arguably the most well-known optical phenomenon that distorts our view of the Universe, there are many physical media that are relevant to the paths along which radiation arrives at our instruments. For example, plasma is the most common state of matter in the universe, constituting the ionized material between the stars, the interstellar medium (ISM).

Plasma lensing occurs independently of gravitational lensing. It is believed to be caused by small, highly over-pressured structures on sub-AU scales [

14,

18]. These structures produce optical effects when they obscure bright background radio sources. Unlike the converging behavior of gravitational lenses, plasma is both diverging and dispersive (chromatic). There are many studies that combine both gravitational and plasma lensing effects [

49,

50], but these are often complicated by the need for extremely low-frequency observations [

51].

In addition to plasma, dust is also ubiquitous throughout the cosmos comprising about

of the ISM. There is a strong connection between X-ray scattering and the properties of dust grains that affect them [

34] at all distances, from interstellar [

36,

37] to intergalactic scales [

35]. Examples of dust rings from bright X-ray transients are known from galactic sources [

31,

41,

42,

43,

44], as well as from the afterglow of long-duration gamma-ray bursts (GRBs; [

39]).

Achromatic gravitational lenses as well as optical events from dispersive astrophysical processes across the electromagnetic spectrum from the dust scattering of gamma ray bursts (GRBs;[

38]) to the propagation of fast radio bursts (FRBs; [

40]) can be modeled using a common, straightforward approach, which yields the usual lensing information such as magnification and image time delays, along with the absorption due to intervening material along the line of sight.

Wagner and Er [

1] compared the formalism for gravitational and plasma lensing. Our current work now extends the applicability of the gravitational lens thin-lens framework to X-ray dust scattering phenomena by using the Drude medium. The Drude model includes absorption which produces the correct energy dependence of the optical depth in the high energy range, where the refractive effects are minimal [

13]. Despite the scattering nature of the X-ray phenomena, the lensing formalism reproduces all related formulae from the X-ray literature. For X-rays the dust particles are like small, refractive clouds, determined by their dielectric properties.

We seek to describe a spherically symmetric semi-transparent lens, analogous to our previous work in gravitational lensing with an absorbing medium [

13]. We wish to specialize these earlier results to the case when a compact object is not present, and consider only a lossy medium arranged in a spherically-symmetric cloud that acts as a dispersive, diverging refractive lens in the interstellar medium (ISM). This model extends the Gaussian lens model originated by Clegg, Fey & Lazio (CFL; [

14]), which has been used extensively in the literature to model the refractive objects responsible for extreme scattering events (ESEs) in background radio sources.

Consider a complex index of refraction,

where

i is the unit imaginary number. We seek to describe electromagnetic radiation passing through a spherical region of Drude medium, an absorbing dielectric that can be thought of as a model for a “dusty plasma”,

where

is the dust collision frequency. The plasma frequency is

along with the classical electron radius,

in cgs units. In the limit where interactions between radiation and absorbing dust are infrequent, the Drude model reproduces cold plasma behaviour [

8,

9,

10]. On the other hand, when radiation and dust interact often absorption dominates over refraction, producing low-angle deflection similar to the behaviour of X-ray scattering due to interaction with dust [

11,

12]. For intermediate values of

, the Drude model produces unique and novel results that include both refraction and absorption.

In this work we assess the feasibility of the Drude lens in the radio regime using ESEs, and in the X-ray regime we derive the properties of dust scattering used in the literature. Consider the observed parameters of ESEs fit by the Gaussian plasma lens [

14]. In the weak-field regime where microlensing-type behaviour occurs, the Drude medium attains a constant, asymptotic value that depends on the parameters of the dust present. Rather than assume a constant grain size, we will fit each observation individually. This allows us to determine if absorption is an applicable phenomenon in a given source, and what grain size is required to approximately match the published results to 1 % agreement. This precision limit is chosen arbitrarily to “sufficiently” reproduce the literature results. If absorption is important, we assume that its effect has been compensated for in the lens parameter fitting, and that absorption in such systems will not be too strong.

2. Theory

We first establish some basic results from the lensing literature ([

1,

2]) and then explore how those outcomes must be modified to accommodate an absorbing medium.

Let the angular coordinates on the image plane, at a distance

from the observer, be defined in terms of the impact parameter

b of a ray

, where

is the angle on the observer’s sky (the image plane). Following the usual gravitational lens conventions, we take the distance from observer to source as

and the distance from lens deflector to source

. We assume spherical symmetry for simplicity, with

the angular position of the source, and

the angular position of the resulting image. The thin lens equation that translates from source coordinates (

) to image coordinates measured on the sky (

) is

The projected plasma density on the lens plane is

The effective plasma lens potential [

5] is

For a given effective potential, the deflection angle [

4] is

which gives, using eq.

7,

A well-known identity exists [

6,

7] which solves the deflection angle for power-law type plasma density

[

13]. However, in this work we seek the deflection angle in terms of projected density

, following [

14].

Absorbing media are dusty plasmas that are described by the Drude [

3] index of refraction given in eq.

2. We note that the real part of the index of refraction is the cold plasma index of refraction modified by adding the collision frequency to the wave frequency. In the weak-deflection limit, it has been shown ([

13]) the Drude medium deflection angle reproduces the cold plasma results found in the literature [

8,

9,

10] provided

. Given the wavelength

and the average collision distance between photons and dust particles,

leads to a substitution for the modified effective lens potential (eq.

7) and modified deflection angle (eq.

9),

We note the first expression on the right hand-side allows for easy visual evaluation of the limit in which the mean collision distance

grows large. In this case, the Drude model reproduces the cold plasma index of refraction [

3,

13]. The limiting behaviour of the second expression on the right-hand side requires L’Hopitals rule. Let us define shorthand for the Drude effective wavelength,

In terms of frequency dependence, it is

that distinguishes between cold plasma

and Drude medium

by eq.

11.

For completeness, the modified deflection angle is explicitly stated,

with

This expression depends on the gradient of the projected plasma density. For a spherically symmetric lens, we expect the density to generally decrease radially from the lens center, which provides the negative sign that flips the deflection angle from converging to diverging orientation. In the limit of vanishing dust density i.e., when the average distance between collisions between photons and dust particles becomes infinite

eq.

12 reproduces eq.

9.

Now that we have established the deflection angle, let us turn to the time delay.

The first term in this expression is the geometric term, which is the delay due to the physical path length. The second term, which depends on the lens potential, is the gravitational term that is due to moving in a potential, called the Shapiro delay [

4,

30]

where the negative sign shows that this is a delay. In plasma lensing, this extra delay is due to the charged matter distribution along the line of sight

This is the same in form as the plasma lens time delay [

27,

29], except with the wavelength

replaced by the Drude frequency function

.

In addition to the usual lensing properties, We now calculate the absorption profile associated with the Drude medium. As shown in [

13], the optical depth is

using the definition from the Drude medium, eq.

2, we find

or, in terms of the wavelength,

with

In the limit of infinite mean collision distance, the optical depth vanishes since the cold plasma index of refraction is purely real and hence for that case.

The optical properties of the Drude medium are summarized by the pair of quantities, the deflection angle (eq.

12) and the optical depth (eq.

19).

2.1. Implications: The Magnification of the Drude Lens

The magnification of an absorbing lens is given by a combination of the usual Jacobian determinant of the thin lens transformation, and the optical depth of the lens plane itself. The total magnification is

with the images indexed by the subscript

a. Since the lens is spherically symmetric, the refractive magnification is comprised of two factors,

The images have tangential magnification

and radial magnification

Putting these two expressions together gives the total magnification for a given image

with

the scaling factor given in eq.

13. However, other than the difference in frequency dependence due to

, the critical and caustic networks of the absorbed Drude material and plasma are identical in form. Despite this apparent similarity, the presence of absorbing material further complicates the calculation of the total magnification, as the optical density

alters the individual intensity of each independent image by the exponential coefficient in eq.

21.

2.2. Observational Signature of the Drude Lens

The Drude medium produces a lens magnification given by eq.

25. In this expression, all terms beyond unity are dependent on a power of the coefficient

A, which is itself directly linearly proportional to

. Similarly, the lens optical depth is directly proportional to

. Therefore, the effective wavelength directly controls how both of these quantities evolve across the electromagnetic spectrum.

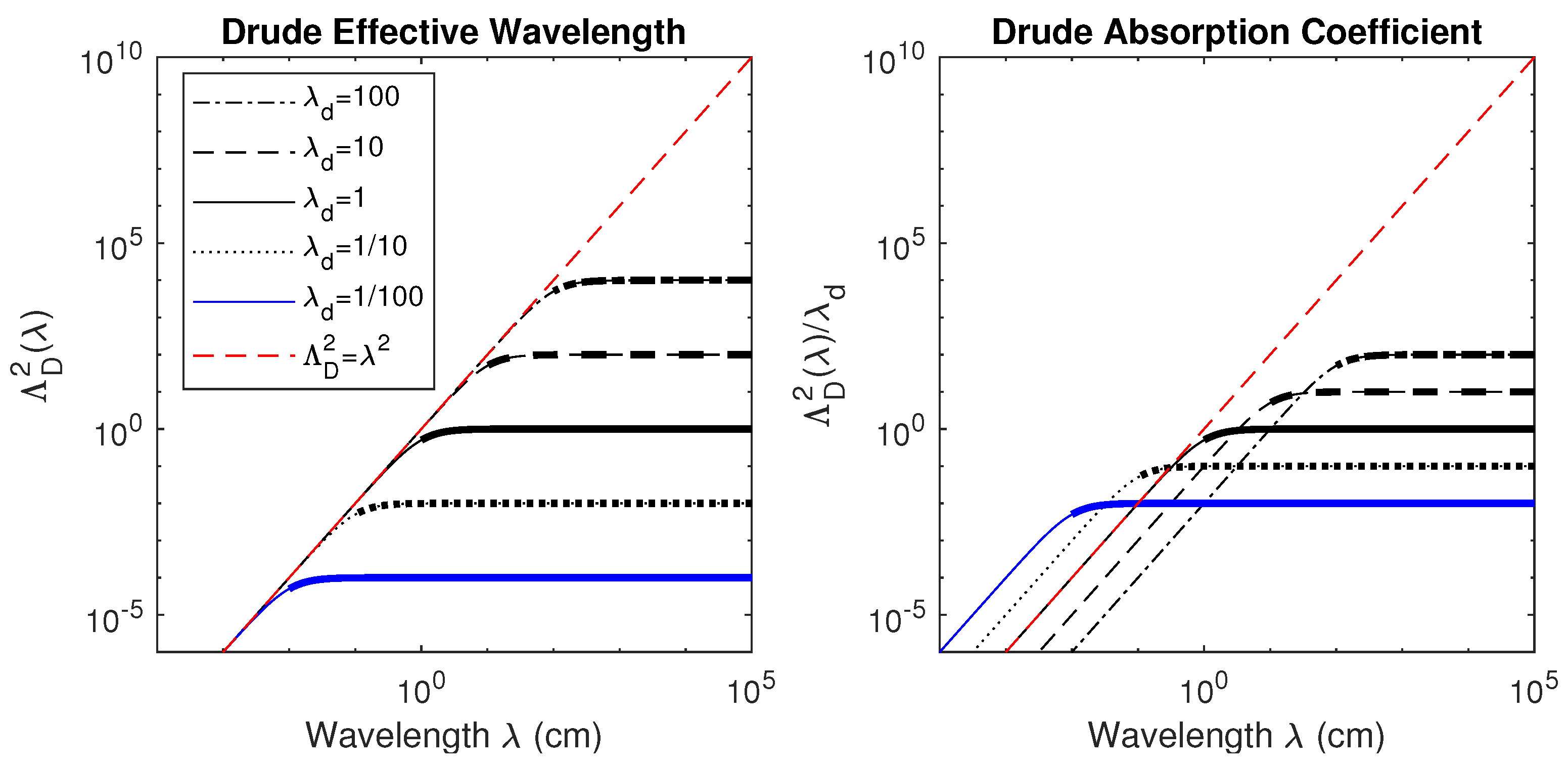

We plot both the square of the effective wavelength

, as well as the coefficient that appears in the optical depth,

, in

Figure 1 as a function of wavelength. We define the dimensionless size parameter as

where

a is the radius of a spherical dust grain. When

, we are in the Rayleigh regime, in which the grain size is much smaller than the incident radiation. In the Rayleigh limit, the absorption cross-section for dust is much larger than the scattering cross-section, so absorption processes dominate [

17].

As seen in the left hand panel of

Figure 1, the effective wavelength approaches a constant asymptotic value in the Rayleigh region, when the wavelength of radiation is much greater than the characteristic wavelength of dust

(

). In the Rayleigh regime the magnification and optical properties of the Drude lens lose their wavelength dependence and approach an asymptotic value. In the opposite limit, outside the Rayleigh regime, we see the effective wavelength evolve as

. The optical behavior of the Drude lens is only chromatic for wavelengths below the dust characteristic scale (ie,

or

). This is dramatically different than the behavior of cold plasma, shown as the dashed line in

Figure 1, in which the optical properties of a plasma lens evolve with wavelength. Therefore, the key to distinguishing these models is through multi-band observations, which would be capable of determining how the lens scale evolves with wavelength. If an estimate of the turning point of

could be measured (essentially determining the wavelength after which the magnification becomes constant), this would give the characteristic dust scale and the grain radius of the dust present in the lens.

When

, we are considering the low-wavelength, high-frequency part of the electromagnetic spectrum. Similar to cold plasma, when the wavelength of radiation is sufficiently small, the refractive effects of the lens become weak. This describes an optical effect similar to low-angle X-ray scattering. In fact, when

, we see the Drude absorption coefficient grow as

. This is the well-known

dependence of optical depth on X-ray energy in the keV range [

46]. Thus, the Drude medium extends the applicability of gravitational and plasma lensing methods to describe lensing phenomena in the X-Ray regime.

3. Radio Application: Extreme Scattering Events: The Diverging Gaussian-Drude Lens

The arguments presented so far have been totally general, depending only on the projected density

. These results extend the work of [

13] in the absence of gravitational effects and consider the lensing properties of a projected Drude medium only. The lens column density depends on the projected plasma density

and its magnification depends on the first and second derivatives of the projected density on the plane of the sky.

Let us follow Clegg, Fey and Lazio [

14] and assume the projected density has a spherically symmetric Gaussian form,

The CFL lens is the most widely applied model for describing ESEs [

15,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. We briefly summarize the properties of the Gaussian lens in detail. Using the definition of the characteristic radius,

we have

giving the lens magnification

which agrees with the formula in [

16] (eq. 51), provided the substitution from eq.

10 is made. The optical depth is

and leads to the extinction factor

matching the expression in [

13].

The radial extent of the lens is cm, and the projected lens number density is cm2. The scattering time depends on the radius of a dust grain along with the speed of light. The dust collision frequency is then , and gives . This leads to the collision wavelength and allows the calculation of , lens optical depth, deflection angle and the magnification.

The lens parameters of the ESEs previously modeled in the literature are given in

Table 1, summarizing the results of [

18]. We use the Gaussian lens parameters from the modeled systems to evaluate the optical depth for each system at the lens width

on the lens plane.

Table 1 collects data on the observed properties of ESEs. The estimated radius

R, number density

and projected density

as well as an estimate of the grain size

required for a

intensity drop from the literature model, as well as the grain size required for a corresponding

intensity drop.

5. Conclusions

If absorbing material is present within a lens but not accounted for within the model used to describe it, the fitting procedure will bias the resulting parameter estimates. Our approach is to estimate the dust grain size necessary for a

and

drop in intensity at the specific location

for the model parameters given in the literature. Dust in the ISM is comprised of amorphous carbon and silicon, and the radii generally range from nm to

m scales [

26]. We estimate grain sizes necessary for the required absorption and compare with the expected scale. Systems that predict grains far too small to be realistic are essentially unaffected by absorption. This method for estimating plausibility is approximate, and detailed modeling is required to determine the exact drop in intensity that would be caused by this granular material along the line of sight. Our model assumes mono-disperse grains, but in reality the grain radius is given by a distribution over sizes. For all but two ESE observations given in

Table 1, the predicted grain radii appear plausible for the observed lens parameters on the order of both

and

adjustment of the magnified image intensity. In principle, this suggests plausible absorption may be compatible with current observations and models, depending on the uncertainty in the fits. The observations correspond to ESEs in the systems 1741+038, 2023+335, PKS 1939-315, PSR B1937+21, PSR J1603-7202 and PSR J1017-7156. If absorption is important in these lens structures, perhaps some evidence of their existence could be revealed through multi-band observations, probing the lens at many frequencies as the ESE is ongoing. The wavelength evolution of the models separates cold plasma from absorbing Drude material, which is fixed by observation. We do not suggest the observed ESEs are Drude lenses due to the observed wavelength behavior. However, our study does show that in principle absorbing material within ESE scale lenses is plausible at observable scales, and that achromatic ESE-like events would provide evidence toward the existence of such dusty, absorbing lenses.

Dust grains in the ISM obey a power-law [

26] and there is uncertainty in both ends of the size range, such that

nm grains may be physically plausible. Only one of the eleven observations predicts grain sizes that are unphysically small. The system PSR B1800-21 is strictly incompatible with observations, predicting grain size that potentially ranges between

nm, which is more than two orders of magnitude outside the

nm range. The system 0954+658 is on the edge of this limit at both

and

intensity, with a predicted grain size between

-

nm.

Given that the majority of ESEs considered in

Table 1 could support absorbing material with a slight modification to observed models, we conclude tentatively that absorption due to dielectric dust or other materials within the lenses responsible for ESEs is plausible.

Additionally, we extend the lensing formalism to describe the formation of X-ray haloes by dust scattering. In this limit, the model predicts only weak lensing effects (equivalent to low-angle scattering) and the optical depth frequency behavior matches what is measured empirically in the soft X-ray band.