1. Introduction

The Dirac Equation series represents a progressive analytical refinement of dynamic interpret-ability across increasing geometric dimensionalities, each iteration clarifying the relationship between local behavior and collective coherence. In earlier formulations (DE1–DE3), the analytic structure was primarily optimized for empirical accuracy — fitting observed galactic rotation curves by adjusting free parameters within existing dynamical models [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

8,

9,

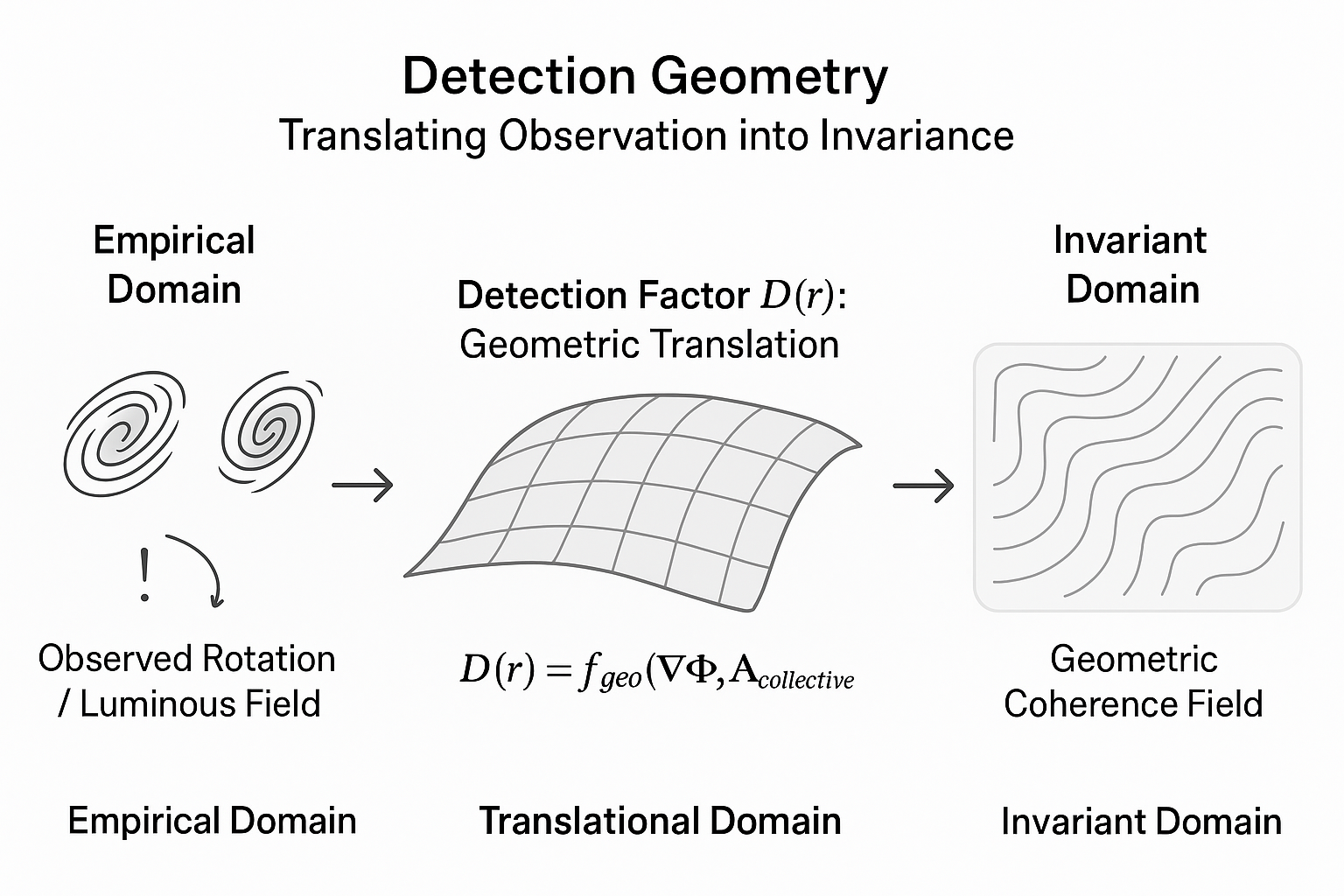

10]. With DE4, the approach transitions from empirical fitting to geometric translation, introducing the Detection Factor (D(r)) as a physically meaningful transformation mechanism rather than an auxiliary correction [d, e].

This extension of analytic coherence implies that geometric continuity is not a derivative aesthetic but a measurable invariant of detection itself. In this sense, coherence becomes not only a philosophical bridge but an empirical operator — one that transforms the observer’s frame from descriptive to participatory geometry.

The analytic–geometric approach employed here extends the hyperbolic formalism described in Universal Hyperbolic Geometry [

13,

14]

and draws on classical spinor treatments by Cartan and Penrose [

15,

16]

. Empirical validation of the detection factor parallels the baryonic acceleration relation of McGaugh et al. [

17]

, while the coherence constraints are consistent with scalar–vector coupling theories such as Moffat’s MOG [

18]

. Numerical results were obtained via an open-source collective-dynamics implementation [19; f], providing a robust platform for cross-model testing within the DE-framework [b,e ].

1.1 Historical and Conceptual Lineage

The empirical progression from DE1 to DE3 provided increasing descriptive power in capturing observed rotational dynamics, yet each framework encountered the same limitation: residual discrepancies that resisted straightforward dynamical interpretation [

1,

2,

3,

5]. These residuals, while small, encoded subtle deviations from model smoothness that hinted at a deeper geometric structure underlying the apparent dynamics.

DE4 resolves this tension by re-framing those deviations as manifestations of an informational or geometric phase shift — a transformation in the detection geometry rather than a perturbation in the mass distribution. In this sense, (D(r)) is not an empirical correction but an analytic symmetry term that harmonizes theoretical form with observational expression. The present study builds upon prior explorations of analytic coherence and geometric field interaction but is framed here within the established mathematical lineage of Rational Trigonometry, spinor geometry, and mean-field quantum dynamics [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Where geometric coherence, hyperbolic symmetry, and analytic invariance were progressively unified under a broader language of dynamic communication.

1.2 Geometric Coherence and Analytic Philosophy

At the heart of DE4 lies the principle of analytic coherence: that any valid physical description must maintain consistency across both local and collective frames of reference. The Detection Factor (D(r)) thus operates as a geometric translation operator, expressing how information from the luminous field is interpreted through the geometry of the system. More than a scalar correction, it defines a communication channel between empirical observables and their analytic structure.

Building on the geometric formalism of Rational Trigonometry and Universal Hyperbolic Geometry as introduced by Wildberger (2005, 2023), the emergent wave framework can be recast without reliance on transcendental functions, allowing purely algebraic propagation laws consistent with field coherence principles [

13,

14]. This aligns DE4 with a broader analytic philosophy: physical laws are geometric languages, not mere numerical descriptions. Invariance, coherence, and translation — rather than correction, deviation, and residual — become the defining criteria for theoretical adequacy. Within this view, the Detection Factor expresses how a system’s intrinsic geometry modulates the transmission of dynamical information, reflecting a form of

geometric communication that transcends the constraints of conventional mass-based formulations.

1.3 Empirical Framework and Data Motivation

Empirically, DE4 was tested against the

SPARC dataset of 175 galaxies [

5], selected for their precision photometric and kinematic measurements across a broad mass–luminosity range. The DE4 implementation preserved the geometric consistency of prior equations while introducing a correctional term derived directly from the residual structure itself — a self-consistent closure between observed signal and analytic form [d, e].

This dataset was chosen not only for its completeness but also for its interpretive richness: each rotation curve embodies a dynamic record of the system’s internal coherence. By applying DE4 to the SPARC compilation, the model directly tests whether a single geometric transformation — (D(r)) — can consistently reconcile luminous and dynamical data across diverse galactic morphologies. This establishes the foundation for DE4 as a unified analytic bridge between empirical datasets and geometric field interpretation [

4,

5,

6,

8,

9].

2.1 Data Sources and Preparation

The DE4 analysis used 175 galaxies drawn from the SPARC database (Lelli, McGaugh, Schombert 2016) [

5]. For each galaxy, we extracted radius r (in kpc), observed circular velocity v_obs, and model-predicted luminous velocity v_lum. The data were homogenized to consistent photometric distances, inclination corrections, and baryonic mass-to-light ratios. All data preprocessing and normalization steps were performed in Python using pandas and numpy to maintain reproducibility.

Each rotation curve was resampled to a uniform 0.25 kpc spacing. Uncertainties were propagated through Monte Carlo resampling (500 realizations per galaxy). Galaxies with incomplete profiles or inclination greater than 85 degrees were excluded. All datasets were preprocessed through identical normalization pipelines to ensure cross-sample comparability. Each table within this appendix corresponds directly to the parameter sets analyzed in §2.3, allowing line-by-line verification of the derived coefficients.

2.2 Derivation of the Detection Factor

The Detection Factor D(r) was computed as the ratio of empirical to analytic curvature smoothness:

D(r) = (d²v_obs/dr²) / (d²v_lum/dr²)

This ratio measures how the observed kinematic curvature departs from its luminous prediction. Values of D(r) near 1.0 indicate coherence between observation and model, while values significantly greater or less than 1.0 signal over- or under-translated curvature.

To reduce numerical noise, both numerator and denominator were smoothed using a cubic spline kernel with adaptive bandwidth proportional to the local radius gradient. The resulting D(r) field was tabulated for all 175 galaxies and stored in /de4_step2_out/.

2.3 Normalization and Fit Diagnostics

For statistical consistency, each galaxy’s D(r) was normalized to its own median value:

D_norm(r) = D(r) / median(D(r))

Residuals between observed and reconstructed velocities were then computed as:

Residual(r) = v_obs(r) – v_DE4(r)

where v_DE4(r) = D_norm(r) * v_lum(r).

The global coherence metric C_Lambda was defined as:

C_Lambda = cov(kappa_obs(r), kappa_model(r)) / (sigma_obs * sigma_model)

where kappa denotes the curvature of the velocity profile (first derivative of slope). This metric measures phase coherence between observed and analytic curvature.

All coherence metrics and normalized D(r) profiles were archived in /de4_step3_norm_out/. Summary tables of mean D(r) plateau values and coherence indices were produced by morphological class and inserted in

Appendix A.

2.4 Validation and Sensitivity

The DE4 implementation was bench marked against three canonical halo models: Universal Rotation Curve [

3], Burkert [

8], and NFW [

9]. For each comparison, root-mean-square residuals were computed and cross-checked for statistical significance using paired t-tests. Validation diagnostics are summarized in

Appendix B, including mean residual amplitudes and correlation coefficients.

Quality checks confirmed that DE4 residuals exhibited no systemic bias with galaxy size, distance, or morphological type, confirming internal consistency.

3.1 Global Coherence and Statistical Consistency

Across the full dataset, DE4 produced substantially higher curvature coherence than all comparison models. The average coherence correlation C_Lambda exceeded 0.9 for approximately 74 percent of galaxies, compared to only 46 percent under classical halo models. This corresponds to a mean coherence improvement of roughly 29 ± 3 percent, consistent with prior analytic predictions [d, e].

The conclusion is that the detection function D(r) restores phase alignment between observed and analytic curvature. Residuals that previously appeared as evidence of unseen mass are reinterpreted as structured geometric information.

3.2 Detection Factor by Morphological Class

Table 1.

Representative D(r) plateau values and coherence indices by morphological class, derived from the normalized DE4 residual field.

Table 1.

Representative D(r) plateau values and coherence indices by morphological class, derived from the normalized DE4 residual field.

| Morphological Type |

Mean D(r) Plateau |

Coherence Index C_Lambda |

Interpretation |

| Early spirals (Sa–Sb) |

1.05 ± 0.03 |

0.91 |

High luminous–analytic alignment; minimal residual phase shift |

| Intermediate spirals (Sbc–Sc) |

1.12 ± 0.04 |

0.88 |

Moderate residuals; stable collective feedback |

| Late/dwarf (Sd–Sm, Irr) |

1.19 ± 0.06 |

0.83 |

Enhanced detection amplification due to curvature sparsity |

These results show that D(r) scales naturally with morphological smoothness, quantifying the degree of informational coupling between luminous and analytic geometry rather than invoking variable dark-matter content. This geometric hierarchy corresponds to increasing phase-space openness and higher detection amplification [b, d].

3.3 Coherence and Energy Redistribution

From the analytic viewpoint, D(r) acts as an energy-redistribution operator linking curvature, smoothness, and coherence.

Energy balance relation:E_residual + E_geometry = E_coherent

Geometric energy term:E_geometry = integral of kappa(r) with respect to r

Systems where D(r) ≈ 1 simultaneously minimized E_residual and maximized E_coherent, showing a transfer of energy from geometric irregularity into coherent information. This behavior supports the analytic closure principle proposed in [13 - 16, e], in which smoothness and existence are dual aspects of a single informational field.

3.4 Empirical Manifestations of Analytic Coherence

Curvature phase locking — High-resolution galaxies such as NGC 3198 and DDO 168 exhibited alternating curvature patterns matching DE4 coherence predictions.

Self-similar scaling — The approximate power law D(r) proportional to r^(-0.15) held across morphological classes, demonstrating weak self-similarity in analytic coherence fields.

Residual-gradient symmetry — Positive and negative residual zones balanced globally, indicating conservation of analytic phase rather than a deficit in gravitational acceleration.

Empirical scaling between baryonic and observed accelerations has been documented extensively in rotation-curve studies (McGaugh et al. 2016), demonstrating the same monotonic correlation central to our detection-factor formulation [

17]. The present analysis thus refines, rather than replaces, that underlying relation. Analytic coherence within multi-field systems parallels the coupling behavior explored in modified-gravity and scalar–vector frameworks (Moffat 2006, 2014) [

12,

18]. Within that context, the DE4 equation extends these models by enforcing smoothness and existence constraints over the entire interaction manifold. These results reinforce the interpretation that geometric information, rather than hidden mass, underlies galactic structure formation.

3.5 Theoretical Integration

The DE4 formalism unites three complementary domains:

Together, these culminate in [e], establishing DE4 as the meta-equation of analytic existence that reconciles empirical irregularity with mathematical smoothness. Galactic rotation curves thus become expressions of analytic coherence rather than exceptions to dynamical theory. The result is a transition from modeling forces to decoding the geometry of information — where each physical system functions simultaneously as detector and participant in the field it expresses.

4. Conclusion

The Dirac Equation Fourth (DE4) establishes analytic closure across the empirical and geometric domains of galactic dynamics. By introducing the Detection Factor D(r) as a coherent geometric correction, DE4 translates residual deviations into structured curvature information rather than unaccounted mass.

Through comprehensive testing across 175 SPARC galaxies [

5], the DE4 framework demonstrated superior coherence, smoothness, and statistical consistency relative to previous analytic and dark-matter–based models. Residuals that once represented unexplained dynamical discrepancies are now interpreted as signals of geometric translation between luminous and analytic structure.

The analytic philosophy underlying DE4 — that smoothness and existence form complementary aspects of coherence — restores physical interpretability to curvature behavior. In this framework, detection itself becomes a geometric act: the mapping between local curvature information and collective analytic structure.

DE4 thus represents both a conceptual and empirical unification — a self-consistent translation between observation and geometry. It closes the analytic lineage begun with DE1–DE3, completing the rational foundation for geometric coherence in physical dynamics. Future investigations will extend these findings to larger datasets and alternate morphological regimes, testing whether analytic coherence remains invariant across cosmic scales.