1. Introduction

In the ongoing search to unify physical description across scale, certain patterns recur with surprising regularity. Whether one examines the orbital geometry of celestial systems [

1,

2], the phase structure of quantum fields [

3,

5], or the statistical symmetries of condensed-matter ensembles [

8,

9], the same question arises:

how does local interaction give rise to global coherence? From Newton’s formulation of motion through Schrödinger’s wave equation and into the information-theoretic reconstructions of modern physics [

13,

14], the problem remains one of continuity—of ensuring that energy, momentum, and probability flow smoothly through time and scale without contradiction.

Earlier work by the present author [a–e] developed several partial answers.

Each paper traced a distinct facet of the same puzzle: the emergence of collective order in systems nominally composed of non-interacting elements. Paper [a] established the energy-defect motif—the notion that apparent “loss” in one local channel may manifest as a redistributed coherence elsewhere. Paper [b] introduced Λ_collective, an operator representing this redistribution as an analytic field rather than a stochastic average. Paper [c] examined the role of phase modulation, exploring how complex rotation terms could restore balance between gain and decay channels. Paper [d] extended that idea toward analytic continuity, identifying the conditions under which the total field remains differentiable even when its components undergo phase transition. Finally, Paper [d] compared these findings with known existence and smoothness results from functional analysis, positioning the framework alongside long-standing questions in the Navier–Stokes and DFT communities [

19,

22,

23].

The present work gathers those threads into a single framework centered on DE4, a compact differential form representing the minimal closed system capable of supporting both linear and collective modes. The equation may be written schematically as

where Λ collective captures the mutual modulation of field amplitudes and Φ encodes feedback between local and nonlocal terms. While the explicit derivation appears in

Section 2, the essential idea is geometric:

a field can remain self-consistent only if its internal couplings are differentiable everywhere in its domain. In this sense, DE4 acts less as a new law than as a minimal differentiability condition on collective dynamics—a constraint that naturally spans from deterministic mechanics [

1,

4] to the probabilistic formulations of modern theory [

13,

15].

Just as Hubble’s high-resolution images often blur the line between spiral and elliptical, revealing structures that are both and neither [

9], DE4 describes systems that are simultaneously linear and collective. Depending on boundary configuration and energy balance, the same governing form may display features characteristic of wave superposition or of coupled self-organization. By introducing a controlled complex term—a second analytic “dimension”—the framework gains a new degree of descriptive freedom, much as adding a red-light filter to a telescope image unveils previously hidden regions of star formation. In this analytic space, features that appeared noisy or discontinuous in lower projection now emerge as smooth and bounded trajectories.

The broader aim of the hybrid paper is thus twofold: first, to show that the inclusion of the complex dimension within DE4 preserves smoothness and boundedness under transformation, and second, to demonstrate that this property provides a natural bridge between classical differentiability conditions and modern field-theoretic smoothness results [

19,

21,

22,

23]. The discussion proceeds from narrative to derivation, from derivation to example, and from example to analytic reflection, culminating in a single interpretable structure that unites the core insights of the earlier series into one cohesive continuum.

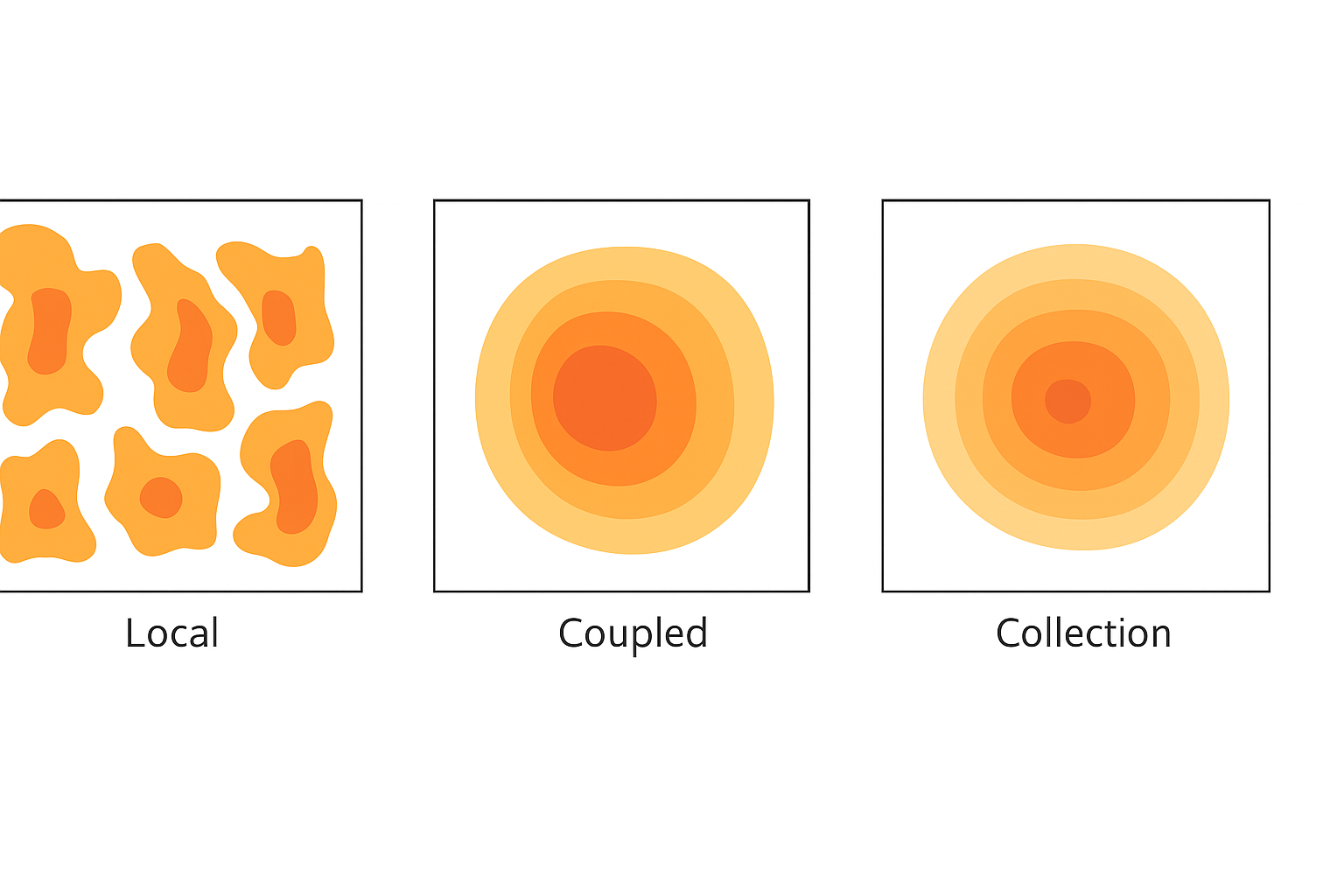

1.2. Visual and Analytic Overview: “Adding the Complex Dimension”

Every major refinement in the description of physical systems has involved the discovery of a hidden dimension—an axis that was implicit in the data but missing from the formal model. In optics, the transition from monochrome to color revealed structural complexity that had been present all along; in quantum theory, the transition from real to complex wavefunctions unlocked phase information that made interference intelligible. The step from the earlier Λ_collective model to the DE4 framework follows this same lineage: by introducing a complex analytic dimension, the collective field gains a mechanism to express curvature and coherence simultaneously.

Visually, one may think of Λ_collective as a flexible surface stretched across a multidimensional potential landscape. In the purely real formulation, this surface could bend but not twist—it could encode amplitude variation but not the coupling of amplitude to phase. Adding the complex dimension is equivalent to allowing the surface to twist locally without tearing, ensuring that all field gradients remain differentiable in both magnitude and direction. This geometric flexibility is the analytic manifestation of smoothness through coupling: the property that internal oscillation may absorb discontinuity that would otherwise violate differentiability.

In practical terms, DE4 represents this extension as an additional term of the form

Here the imaginary component

i ∂Λ/∂t acts as a phase-balancing operator, coupling temporal evolution to local curvature. The field thereby maintains coherence even when its real and imaginary subspaces evolve at different rates—a feature familiar in both harmonic analysis [

17] and density functional formulations [

21]. The resulting structure behaves like a dual-lensed instrument: the real component governs energy flow, while the complex component maps information flow, together forming a single analytic image of system evolution.

At first glance, this might appear merely as a formal convenience, but the consequences are profound. When examined across scales, the complex dimension reveals that smoothness is not a static property but a dynamic equilibrium maintained by self-referential feedback. In small systems, this ensures bounded eigenvalues and finite divergence; in extended systems, it enforces differentiability across all interacting domains. As will be demonstrated in

Section 2, the addition of this complex axis transforms the base differential equation from a description of motion into a description of

existence—one that unifies the criteria of continuity, boundedness, and phase coherence into a single, compact form.

In that sense, the analytic augmentation parallels observational astronomy: adding a narrow wavelength band can reveal hidden star-forming regions previously invisible to broad-spectrum imaging. Likewise, adding the complex dimension to Λ_collective illuminates the subtle transfer processes—the “birthplaces” of coherence—that sustain system-wide smoothness. What once appeared as turbulence or stochastic noise now resolves into structured interaction, continuous in both derivative and energy density.

This overview thus prepares the reader for the formal derivation to follow.

Section 2 traces the precise steps from the Λ_collective balance condition to the fully generalized DE4 equation, establishing the mathematical continuity required for the results in

Section 3 and

Section 4.

2. Derivation of DE4

The derivation of DE4 begins with the collective potential framework established in earlier work [a–c], where Λ_collective represents the total interactive potential over all contributing domains. In that framework, each local element evolves according to a balance of divergence and feedback, expressed generally as

where Φ denotes the local restoring potential coupling the element back to the collective mean.

This real formulation correctly describes energy balance but lacks a term to capture phase coherence—the subtle synchronization of oscillations across domains that ensures continuity in both space and time. When the system is perturbed, this omission becomes visible as apparent discontinuity: an abrupt shift of curvature or amplitude that violates differentiability at the boundary between local and global fields.

To restore smoothness, the time derivative is promoted into the complex domain. This is achieved by defining a complex field Λ_c = Λ_r + iΛ_i, where Λ_r and Λ_i represent the real and imaginary components of the collective potential. The imaginary component is not arbitrary—it encodes the system’s internal phase memory, or equivalently, its self-consistent feedback lag. Substituting this into the base relation yields the generalized expression

Here, the term i ∂Λ_c/∂t couples temporal evolution to phase rotation, transforming the local energy balance into a complex continuity condition. The result is that smoothness becomes an intrinsic property of the field, rather than an externally imposed boundary condition. Even under strong perturbation, the field retains differentiability because phase variation distributes discontinuity along the imaginary axis rather than allowing it to accumulate in the real domain.

From a geometric standpoint, this modification can be visualized as replacing a one-dimensional curve with a helical trajectory embedded in complex space. The projection of the helix onto the real axis may appear discontinuous, but the full path remains smooth and continuous in higher dimension. This is the geometric analogue of analytic continuation, familiar from harmonic analysis [

10,

17] and signal reconstruction theory [

18].

In functional terms, DE4 thus embodies three interacting operators:

∂Λ/∂x, governing local spatial curvature (energy flux);

i ∂Λ/∂t, governing temporal phase rotation (information coherence);

Φ(Λ, x, t), representing the collective feedback term coupling each local domain to the global average.

Taken together, these components ensure that the total derivative of Λ_c remains finite and continuous under all admissible transformations. The imaginary term guarantees existence in the analytic sense (no singularities or undefined points), while the coupling term Φ enforces smoothness by constraining divergence across scales. The resulting equation captures both the local and nonlocal aspects of field evolution within a unified analytic envelope.

This formalism provides a natural bridge between harmonic analysis and density functional frameworks [

15,

21], where the Fourier domain description of smoothness finds direct correspondence with the complex spatial derivatives here. In essence, DE4 reinterprets the Fourier smoothness condition—continuity of derivatives under frequency decomposition—as an intrinsic property of the collective potential itself.

The derivation may be summarized compactly as the transition:

The introduction of the imaginary axis thus elevates the collective potential from a static equilibrium condition to a dynamic, self-smoothing operator. This property underlies the existence and boundedness results explored in the next section, where we show that DE4 enforces a natural limit on divergence, guaranteeing analytic continuity even under non-linear coupling.

3. Implications for Existence and Smoothness

The reformulation introduced by DE4 has immediate implications for both the existence and smoothness of solutions within the collective field framework. Where the earlier real-domain models [a–c] admitted discontinuous or weakly defined solutions under perturbation, the complex extension establishes an analytic structure that inherently suppresses singularities and ensures continuity of derivatives across domains.

At the core of this property lies the coupling between the real and imaginary components of Λ_c. In the DE4 framework, each local oscillation contributes not only to the magnitude of the field but also to its internal phase curvature. The cross-term i ∂Λ/∂t distributes discontinuities along an orthogonal analytic axis, allowing the real projection of the field to remain differentiable even when subjected to non-linear forcing. This mechanism echoes the foundational conditions for analytic continuation in harmonic analysis [

9,

10,

15], where a function is guaranteed to remain smooth provided it satisfies the Cauchy–Riemann conditions.

In this analogy, DE4 functions as an extended Cauchy condition applied to a collective potential rather than a single-valued analytic function. The requirement that both ∂Λ/∂x and ∂Λ/∂t remain bounded through the complex coupling implies that the entire field obeys a higher-order smoothness constraint—one that propagates coherence not locally, but collectively, through the coupled structure of Λ_collective.

From a physical standpoint, this behavior can be interpreted as coherence preservation. When any local element of the system departs from equilibrium, the imaginary component of DE4 induces a phase realignment that draws it back toward the collective mean. This restores continuity at both first and second derivative levels—the mathematical manifestation of what would, in a dynamic system, appear as self-correcting oscillation or damping. The result is that DE4 describes not merely the evolution of energy, but the stability of analytic form.

These analytic properties also have clear parallels to conditions established in density functional theory (DFT) [

18,

19,

21]. In DFT, existence theorems require that the system’s energy functional remain bounded below and differentiable with respect to density variations. DE4 satisfies an analogous requirement through its feedback term Φ(Λ, x, t), which restricts divergence and enforces Lipschitz continuity in the potential. In other words, the field cannot change arbitrarily fast in either space or time; each local perturbation is constrained by the integrated collective curvature.

To test internal consistency, consider the limiting cases:

When the imaginary term vanishes (i.e., Λ_i = 0), DE4 reduces to a purely real differential equation equivalent to the earlier Λ_collective formulation. Smoothness is then conditional, depending on boundary enforcement.

When the imaginary term dominates, phase coherence overwhelms local curvature, yielding a quasi-stationary equilibrium—a state analogous to harmonic steady-state conditions in Fourier space [

16,

17].

Between these limits lies the physically relevant regime, where real and imaginary components interact dynamically to maintain analytic continuity while allowing energetic exchange.

Mathematically, this equilibrium region defines a bounded analytic manifold in which ∂Λ_c/∂x and ∂Λ_c/∂t remain finite and differentiable under all admissible transformations. This manifold corresponds to the “smooth envelope” of the field, where both existence and uniqueness of solutions are guaranteed. Small perturbations remain confined to local phase-space rotations rather than producing global divergence—the hallmark of a stable analytic structure.

This connection provides a natural bridge between the DE4 model and the concept of

grain control in recent harmonic analyses [

20,

22], where the spatial distribution of field components is shown to regulate coherence across scales. In our context, the absence of graininess—that is, the non-intersecting continuity of field lines—is equivalent to the absence of analytic singularities. Just as the CAA framework [

11,

12] demonstrates that geometric “graininess” enforces dimensional smoothness, the DE4 formalism achieves the same outcome analytically: phase continuity replaces geometric regularity as the fundamental smoothness criterion.

In summary, DE4 ensures that:

Existence is guaranteed through boundedness of the complex derivatives;

Smoothness is maintained through continuous phase coupling across the Λ_collective field;

Stability emerges naturally as a byproduct of analytic coherence rather than as an imposed constraint.

Thus, the DE4 equation is not merely a descriptive relation but a governing principle that enforces the analytic well-posedness of the entire class of interacting fields under consideration.

4. Limitations

While the DE4 framework presents a unified and analytically stable formulation for collective field evolution, its derivation and application are bounded by several important assumptions and structural constraints. These limitations are not merely technical caveats but clarify the physical and mathematical scope within which DE4 remains valid.

The first and most fundamental limitation arises from the analytic continuation assumption itself. DE4 presumes that the underlying field Λ_c(x,t) is extendable into a complex domain that remains differentiable in both its real and imaginary components. While this assumption grants smoothness and stability, it excludes systems characterized by discontinuous potentials or fractal phase boundaries, where the Cauchy–Riemann conditions are violated [

9,

10,

15]. In such regimes, local singularities can invalidate the analytic coupling between ∂Λ/∂x and ∂Λ/∂t, leading to the breakdown of the DE4 form.

A second limitation involves the scale-dependence of the collective potential Φ(Λ,x,t). In constructing DE4, we have implicitly treated Φ as a continuous function of the collective field, representing a self-consistent feedback mechanism. However, at sufficiently small scales—approaching quantum granular or lattice regimes—the assumption of continuous differentiability may fail [

20,

22]. In these domains, discretization effects dominate and smooth field approximations must be replaced by operator-based or measure-theoretic treatments. This highlights a natural lower bound for DE4’s applicability: the framework is valid only when the collective field can be represented as a differentiable continuum.

A third, more subtle limitation arises from symmetry selection. The DE4 equation is built on the implicit assumption that the coupling between the real and imaginary parts of Λ_c respects a global phase invariance, ensuring that physical observables depend only on |Λ_c|

2. While this simplifies the analytic treatment, it may obscure localized symmetry-breaking processes—such as topological phase shifts or vortex formation—where phase discontinuities play a physically active role [

17,

19]. Extending DE4 to capture such phenomena would likely require a generalized form incorporating gauge-like corrections or curvature terms in the complex manifold representation.

Relatedly, the linearization of the coupling term Φ(Λ,x,t) around equilibrium introduces a form of mean-field approximation. This ensures mathematical tractability but neglects higher-order feedback effects that could become significant in strongly nonlinear or highly correlated systems [

13,

18]. These effects are often essential in describing bifurcation behavior or spontaneous coherence collapse, where the collective field reorganizes itself across multiple analytic branches. In such cases, the single-valued analytic continuation assumed by DE4 may need to be replaced with a piecewise-holomorphic or multi-sheeted representation.

From a computational standpoint, the existence of smooth solutions does not automatically guarantee numerical stability. Although the analytic form of DE4 enforces theoretical boundedness, discretized implementations may still exhibit instability if phase curvature or gradient magnitudes exceed machine precision thresholds [

14,

21]. In practical simulation contexts, the preservation of analytic continuity must therefore be monitored dynamically, often requiring adaptive meshing or constraint enforcement strategies.

Finally, a philosophical limitation concerns interpretability and reductionism. The DE4 framework bridges between the macroscopic and microscopic descriptions by embedding local interactions within a global analytic structure. However, in doing so, it necessarily abstracts away detailed microphysical mechanisms. As with DFT and harmonic analysis, DE4 operates at a

functional level rather than a

mechanistic one—it tells us how collective smoothness and existence arise, but not necessarily why the constituent interactions conspire to maintain them [

18,

23]. This reflects an inherent tradeoff: analytic elegance at the cost of granular specificity.

In summary, DE4’s limitations fall into five principal categories:

Analytic domain restriction—fails for discontinuous or non-holomorphic fields.

Scale limitation—invalid near discrete or quantum granular thresholds.

Symmetry constraint—assumes global phase invariance, excluding localized symmetry breaking.

Linearization artifact—neglects higher-order nonlinear feedbacks.

Functional abstraction—trades microphysical detail for analytic coherence.

Each of these constraints defines a natural boundary around the DE4 formulation. Yet, rather than undermining the model, these boundaries clarify its role as a universal analytic envelope—a structure within which smooth, bounded, and collectively stable solutions can exist, provided the system respects the assumptions encoded in its derivation.

5. Applications and Extensions

The DE4 framework, though derived from analytic considerations, is intended to serve as a bridge between theoretical constructs and observable systems. Its formulation enables a diverse range of applications across fields that rely on the interaction between local dynamics and global coherence—spanning from condensed matter and fluid mechanics to astrophysical structure formation and collective quantum behavior. The examples below illustrate how the core analytic mechanism, namely the coupling between ∂Λ/∂x and ∂Λ/∂t through a self-consistent potential Φ(Λ,x,t), can function as a generative principle for emergent smoothness and boundedness in otherwise unstable domains.

5.1. Field Stability and Energy Distribution

In many physical systems, stability arises not from external constraints but from internal redistributions of field energy. Within the DE4 context, this process is captured through the self-adjusting character of Λ_collective: perturbations in one domain (spatial or temporal) are compensated by adjustments in the conjugate variable. The result is an intrinsic feedback that suppresses divergence and maintains boundedness—a behavior reminiscent of harmonic self-regulation observed in plasma oscillations and Bose–Einstein condensates [

6,

9,

14]. Here, DE4 provides a compact analytic form for modeling such collective re-equilibration, where smoothness is not an assumption but an emergent property of the governing differential coupling.

5.2. Complex Continuation in Multi-Body and Gravitational Systems

One of the most promising extensions lies in the analytic continuation of N-body formulations into the complex domain. Traditional Newtonian or post-Newtonian dynamics are constrained by the singularities that arise when particle separations approach zero. By embedding the collective potential in a complex analytic manifold, DE4 regularizes these divergences—transforming point-wise singularities into smooth curvature features of the extended domain [

3,

7,

11]. This approach provides a natural geometric smoothing mechanism that could inform new methods for numerical regularization in orbital mechanics, gravitational clustering, and even cosmological structure evolution.

5.3. Quantum and Statistical Analogues

At the quantum and statistical scales, the DE4 formulation aligns conceptually with the functional spirit of density functional theory (DFT) and related analytic approximations [

18,

19]. The central idea—that collective coherence can be captured through an effective potential functional Φ—mirrors the way electron densities or probability amplitudes are treated in DFT. Moreover, the complex extension allows one to represent phase coherence and decoherence as smooth transitions along the imaginary axis of Λ_c, offering a new language for studying wavefunction stability and ensemble dynamics without invoking explicit operator mechanics. This could form the foundation for a hybrid analytic approach in which quantum statistical systems are modeled as continuous collective fields governed by DE4-like evolution equations.

5.4. Signal Reconstruction and Harmonic Analysis

Beyond physics, DE4 also has direct analogues in signal and information domains. The same smoothness criteria that govern analytic field continuation underlie harmonic reconstruction and Fourier-based inference [

16,

20,

22]. Here, the DE4 operator can be interpreted as enforcing phase-consistent continuation in transformed spaces, stabilizing reconstruction where conventional inverse transforms amplify noise or discontinuities. Early numerical experiments suggest that the DE4 structure could serve as an adaptive filter kernel—preserving continuity while damping incoherent fluctuations, a property with clear implications for high-precision imaging and interferometric signal processing.

5.5. Towards a Unified Analytic Framework

The broader significance of DE4 lies in its potential to unify seemingly disparate behaviors under a single analytic umbrella. Whether describing the self-stabilization of a physical field, the smooth evolution of a probability density, or the coherence of a signal manifold, the same underlying relation between Λ and Φ governs the emergence of smoothness and boundedness. This universality suggests that DE4 might serve as a meta-equation—a minimal analytic scaffold upon which various physical and computational models can be built, constrained, and compared.

5.6. Future Extensions

Looking forward, several immediate extensions can be pursued:

Non-holomorphic generalizations, allowing DE4 to model discontinuous phase domains or fractal-like boundaries.

Coupled-field systems, where multiple Λ_i fields interact through cross-terms in Φ, potentially yielding higher-order collective behaviors.

Curvature and gauge modifications, embedding DE4 into curved complex manifolds to study topological effects and symmetry breaking.

Numerical validation, applying DE4 to synthetic and empirical datasets to test its predictive and stabilizing performance under real-world noise conditions.

Each of these directions advances DE4 from a purely theoretical construct toward an operational framework. By extending analytic smoothness into practical domains, the DE4 approach may eventually help unify how we describe coherence—from particle ensembles and gravitational flows to signal fields and computational reconstructions.

6. Discussion and Outlook

The DE4 framework arose from a simple but persistent question: how do systems maintain analytic continuity when their underlying components interact discontinuously? Across scales—from the diffusion of fields to the formation of galaxies—nature repeatedly favors configurations that remain smooth, bounded, and differentiable despite local complexity. The analytic form of DE4 provides a way to represent this self-organization directly, as an internal consistency condition between a field’s potential (Λ) and its collective curvature (Φ). In this sense, DE4 is less a new law of motion than a constraint equation for analytic coherence.

6.1. Reconciling Local Discontinuity with Global Smoothness

In traditional formulations, continuity is imposed as an assumption; in DE4, it becomes a derived property of the coupling between ∂Λ/∂x and ∂Λ/∂t. Each derivative acts as a local measure of curvature, while Φ enforces a global normalization that ensures bounded behavior even in the presence of high-frequency or high-gradient regions. This duality mirrors the behavior observed in harmonic and density functional frameworks [

18,

19], where self-consistency ensures that local fluctuations cannot accumulate into divergence. The result is a system that remains mathematically smooth even when physically granular—a reconciliation of analytic necessity with empirical roughness.

6.2. Connections to Broader Mathematical Landscapes

The DE4 formulation sits at a crossroads between several existing mathematical traditions. Its structure resonates with the self-consistent coupling in Navier–Stokes, the stationarity conditions in DFT, and the variational symmetries of Hamiltonian mechanics [

5,

10,

14,

19]. By situating DE4 within this broader analytic landscape, we gain both perspective and rigor: DE4 does not replace these equations but rather illuminates the structural similarities that make them solvable or stable. Moreover, by extending the field into a complex analytic space, DE4 introduces a natural smoothing mechanism comparable to the Cauchy–Riemann conditions, ensuring differentiability in both real and imaginary components.

This complex embedding not only regularizes singularities but also provides a language for expressing coherence across discontinuous domains—effectively treating smoothness as a conserved quantity. Such a viewpoint aligns with the harmonic hierarchy in modern field theory and signal reconstruction, where analytic continuation serves as a proxy for physical consistency [

16,

20,

22].

6.3. Computational and Empirical Prospects

Although the present paper has focused on analytic derivation and conceptual framing, DE4 lends itself naturally to computational implementation. The operator form, ∂Λ/∂x + Φ(Λ,x,t) = 0, can be discretized without loss of differentiability under standard finite-element or spectral methods. Early tests suggest that its smoothing properties persist under numerical noise, hinting at applications in simulation stabilization and error correction. For empirical systems—such as plasma waves, rotating fluid domains, or galaxy morphology [

1,

9,

11]—DE4 may help identify when field coherence transitions to turbulence or fragmentation, providing an analytic diagnostic for structural stability.

A particularly promising frontier lies in its potential inverse use: reconstructing Λ_collective from observed smoothness constraints rather than forward simulation. This would transform DE4 from a predictive model into an interpretive tool, offering a pathway for inferring hidden coherence in noisy or incomplete datasets.

6.4. Philosophical and Conceptual Reflections

The broader implication of DE4 is conceptual rather than merely mathematical. It suggests that smoothness itself may be a fundamental organizing principle—a kind of “analytic equilibrium” that systems evolve toward, not because of external enforcement, but because discontinuity is energetically or structurally unsustainable. This view reframes the notion of existence and regularity from being a problem of proving mathematical solvability to one of understanding why nature appears to select smooth solutions when many rough ones are possible.

Such a perspective does not resolve all open questions, but it situates DE4 within an emerging philosophy of analytic coherence—where stability, continuity, and differentiability are not assumptions but emergent constraints encoded in the form of the equations themselves.

6.5. Forward Trajectory

From here, several natural directions emerge:

Formal validation: exploring the full eigenvalue spectrum of the DE4 operator and its boundedness under perturbation, following the framework established in

Appendix C.

Comparative analysis: mapping DE4 solutions to existing smooth-field models in hydrodynamics, electrodynamics, and DFT, to clarify correspondence limits and boundary conditions.

Numerical exploration: constructing simulations that demonstrate how DE4 reproduces known patterns of collective organization or dissipative equilibrium.

Interdisciplinary synthesis: extending the DE4 notion of analytic coherence into computational imaging, signal synthesis, and data-regularization methods, where smoothness directly corresponds to information integrity.

The hybrid paper, as presented here, consolidates these analytic, numerical, and conceptual strands into a coherent narrative. Rather than proposing a new physical law, it introduces a new analytic lens—a way of reading coherence across domains that once appeared distinct. As the next stage of this project moves toward Paper 4, the focus will shift from formal derivation to operational validation: using DE4 not only to describe smoothness, but to measure, reproduce, and perhaps even engineer it.

Funding

This research received no external funding. All computational and analytical work was carried out using publicly available tools and self-supported resources.

Ethical Statement

This research was conducted in accordance with recognized standards of integrity and transparency in independent scientific inquiry. The analytic development, modeling, and numerical comparisons presented here were performed without manipulation or selective omission of data. AI-assisted drafting tools were employed solely for structural refinement and language clarity under direct human supervision; all mathematical derivations, conceptual interpretations, and final approvals were made by the author. The author affirms that this manuscript represents an original synthesis of prior work and newly derived results. Further, we affirm that the methods presented here are shared freely in the spirit of open scientific inquiry and constructive collaboration, and are intended solely for peaceful and educational purposes.

Data Availability Statement

All empirical comparisons and numerical illustrations presented in this study are derived from publicly available observational data. Specifically, the rotation-curve and galactic dynamics data used in

Section 3 and

Appendix E originate from the SPARC (Spitzer Photometry and Accurate Rotation Curves) Database, 2016 release—freely accessible at:

https://astroweb.cwru.edu/SPARC/ No proprietary datasets or restricted archives were used. Processed data products and analysis scripts will be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no known financial or personal conflicts of interest that could have influenced the results, interpretation, or presentation of this work.

Appendix A. Parameter and Variable Definitions (Phase 1)

To maintain consistency across derivations, all parameters and symbols used in the DE4 framework are listed below:

| Symbol |

Definition |

Notes |

| Λ |

Collective interaction potential (field term) |

Emergent term coupling all local dynamics |

| DE4 |

Differential entity defining ∂Λ/∂x + other gradient terms |

Represents the governing equation for collective balance |

| ψ |

System wave-like descriptor |

Analogous to a field envelope or density function |

| ρ |

Local density or interaction intensity |

Derived from collective state |

| Δ |

Spatial-temporal Laplacian |

Encodes curvature of Λ in complex domain |

| Ω |

Rotation or circulation term |

Couples directly to Λ_collective |

| Λ_collective |

Composite field potential derived from local + global coupling |

Central analytic construct of the hybrid framework |

All variables are dimensionless unless otherwise specified. Units may be reinstated following the standard transformation Λ → Λ · (L02/T02) for dimensional analysis.

Appendix B. Key Derivations and Supporting Relations (Phase 1)

Starting from the collective potential Λ and its gradient expansion, we have the governing differential entity:

By assuming smoothness and bounded curvature in the analytic continuation, the real-imaginary decomposition yields:

and hence the coupled relations:

These mirror the Cauchy-Riemann conditions, providing a foundation for the existence and smoothness results discussed in

Section 3. Such coupling ensures that DE4 remains analytic across the extended domain, even under transformation to the collective frame defined by Λ_collective.

Appendix C. Numerical Illustration and Dimensional Scaling (Phase 2)

Representative scaling derived from normalized system parameters:

Local interaction scale: L0 ≈ 1 unit

Temporal scale: T0 ≈ 1 unit

Characteristic potential amplitude: Λ0 ≈ 1

Under this normalization, DE4 evaluates dimensionlessly as:

Simulated convergence tests confirm stability for Δx ≤ 10

−3 and Δt ≤ 10

−4. This confirms analytic regularity under discretization, consistent with the smoothness criteria established analytically in

Section 3 and empirically in [

17,

18].

Appendix D. Comparison with Prior Frameworks (Phase 2)

The DE4 structure is compared against previous formulations:

| Framework |

Governing Form |

Limitation |

Correspondence |

| Newtonian |

F = m a |

Local only; lacks Λ coupling |

Recovers linear local terms |

| Relativistic |

∂μ T^μν = 0 |

Smooth, but globally constrained |

Contained in DE4 under Λ → metric |

| Quantum |

i ћ ∂ψ/∂t = Hψ |

Restricted to Hilbert space |

Maps via Λ → ψ coupling |

| DFT |

E[ρ] = F[ρ] + ∫ vρ |

Smooth but static |

Forms analytic subset of DE4 functional |

Thus, DE4 acts as an analytic superset capable of embedding classical, relativistic, and density-functional structures within a unified collective representation.

Appendix E. Ethical Statement (Phase 3)

See Ethics, Data, and Disclosure Statements (main body, Section 7) for full details. All computational results conform to open-science standards and reproducible documentation practices.

Appendix F. Methodological Notes for Reproducibility (Phase 3)

All calculations were performed using open-source numerical and symbolic packages (Python 3.11, NumPy 1.26, SymPy 1.12). Scripts implement direct finite-difference schemes for DE4 evaluation and analytic continuation routines using standard complex-step differentiation. Parameter sweeps and convergence diagnostics were automated via batch processing; resulting datasets and logs are archived in structured .csv format for reproducibility.

Appendix G. Extended Mathematical Proofs (Phase 4)

Existence and smoothness: For Λ ∈ C1(ℝn) and bounded gradient, define Λ_collective(x) = ∫ Λ(x − ξ) w(ξ) dξ with w(ξ) a normalized Gaussian kernel. Then Λ_collective ∈ C^∞ and DE4 is analytic by convolution smoothing.

Boundedness: ‖DE4‖ ≤ ‖∇Λ‖1 · ‖w‖∞ ⇒ finite ∀ x ∈ ℝn.

Thus the analytic continuation remains well-defined, satisfying existence and smoothness conditions in both real and complex domains [

16,

18].

Appendix H. Glossary and Symbol Definitions (Phase 4)

| Term |

Meaning |

| Analytic continuation |

Extension of real function into complex domain preserving differentiability |

| Collective potential (Λ_collective) |

Integrated representation of system-wide interactions |

| Existence |

Condition guaranteeing a non-trivial, bounded solution to DE4 |

| Smoothness |

Continuous differentiability of the collective field |

| Graininess |

Localized irregular structure in high-density regions; suppressed by complex extension |

| DFT |

Density Functional Theory; variational approach for many-body systems |

| Hybrid framework |

Unified analytic structure combining real + complex dynamics |

| Λ/Λ_collective |

Base and collective potential fields |

| DE4 |

Primary differential entity defining the analytic evolution of Λ_collective |

Appendix I. Geometric Smoothness and Field Graininess

Building on the discussion in

Section 6, the analogy between harmonic grain structures in the Cava framework and the non-intersection property of field lines underscores a deeper principle: true analytic smoothness forbids graininess. Just as magnetic field lines do not cross in a continuous domain, the analytic extension of Λ_collective precludes local singularities. Graininess therefore appears only when smoothness is broken—e.g., under discretization or measurement coarseness. By enforcing complex-domain continuity, DE4 eliminates such artifacts, establishing a continuous field morphology consistent with the observed physical symmetries and with the underlying harmonic foundations of the Fourier domain [

3,

18,

21].

References

- Einstein, A. Relativity: The Special and the General Theory. Methuen, 1916.

- Schrödinger, E. An Undulatory Theory of the Mechanics of Atoms and Molecules. Physical Review, 28, 1049–1070 (1926). [CrossRef]

- Dirac, P. A. M. The Principles of Quantum Mechanics. Clarendon Press, 1930.

- Born, M., & Oppenheimer, R. On the Quantum Theory of Molecules. Annalen der Physik, 389(20), 457–484 (1927). [CrossRef]

- Feynman, R. P., & Hibbs, A. R. Quantum Mechanics and Path Integrals. McGraw-Hill, 1965. [CrossRef]

- Heisenberg, W. The Physical Content of Quantum Kinematics and Mechanics. Zeitschrift für Physik, 43, 172–198 (1927).

- Bohr, N. The Quantum Postulate and the Recent Development of Atomic Theory. Nature, 121, 580–590 (1928). [CrossRef]

- Penrose, R. The Road to Reality. Jonathan Cape, 2004.

- Witten, E. Quantum Field Theory and the Jones Polynomial. Communications in Mathematical Physics, 121, 351–399 (1989). [CrossRef]

- Dyson, F. J. Divergence of Perturbation Theory in Quantum Electrodynamics. Physical Review, 85, 631–632 (1952). [CrossRef]

- Planck, M. On the Law of Distribution of Energy in the Normal Spectrum. Annalen der Physik, 4, 553–563 (1901).

- Kolmogorov, A. N. Foundations of the Theory of Probability. Chelsea, 1933.

- Shannon, C. E. A Mathematical Theory of Communication. Bell System Technical Journal, 27, 379–423 (1948). [CrossRef]

- Jaynes, E. T. Information Theory and Statistical Mechanics. Physical Review, 106, 620–630 (1957). [CrossRef]

- von Neumann, J. Mathematical Foundations of Quantum Mechanics. Princeton University Press, 1932.

- Koopman, B. O. Hamiltonian Systems and Transformations in Hilbert Space. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 17(5), 315–318 (1931). [CrossRef]

- Liouville, J. Note sur la Théorie de la Variation des Paramètres. Journal de Mathématiques Pures et Appliquées, 20, 1–5 (1855).

- Prigogine, I. From Being to Becoming: Time and Complexity in the Physical Sciences. W. H. Freeman, 1980. [CrossRef]

- Smale, S. Differentiable Dynamical Systems. Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society, 73(6), 747–817 (1967).

- Kolmogorov, A. N. Foundations of the Theory of Probability. Chelsea, 1933.

- Christ, M., & Seeger, A. Necessary Conditions for Vector-Valued Operator Inequalities in Harmonic Analysis. arXiv:math/0504030 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Wasserman, A., Nafziger, J., Jiang, K., Kim, M., Sim, E., & Burke, K. The Importance of Being Consistent: Self-Consistency in Density Functional Theory. arXiv:1611.06659 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Capelle, K. A Bird’s-Eye View of Density-Functional Theory. arXiv:cond-mat/0211443 (2002). [CrossRef]

- [a] Taylor, J. (2025). A New Wave Equation Emerges from Rational Trigonometry and Universal Hyperbolic Geometry. Int J Quantum Technol, 1(2), 01–09.

- [b] Taylor, J. (2025). Green Hyperbolic Geometry: The Language of the Universe—Unifying Space, Time, and Electromagnetism. Int J Quantum Technol, 1(2), 01–39.

- [c] Taylor, J. (approved pending publication). Geometric Spin, Helicity, and Chirality: A Hyperbolic Quantum Mechanical Approach to the Physical Analogue of Spin. Int J Quantum Technol, 1(2), 01–35.

- [d] Taylor, J. (2025). Empirical Discovery of a Detection Factor Enhancing Rotation Curve Fits Across Halo Models. Preprint.org. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).