Submitted:

02 December 2024

Posted:

04 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

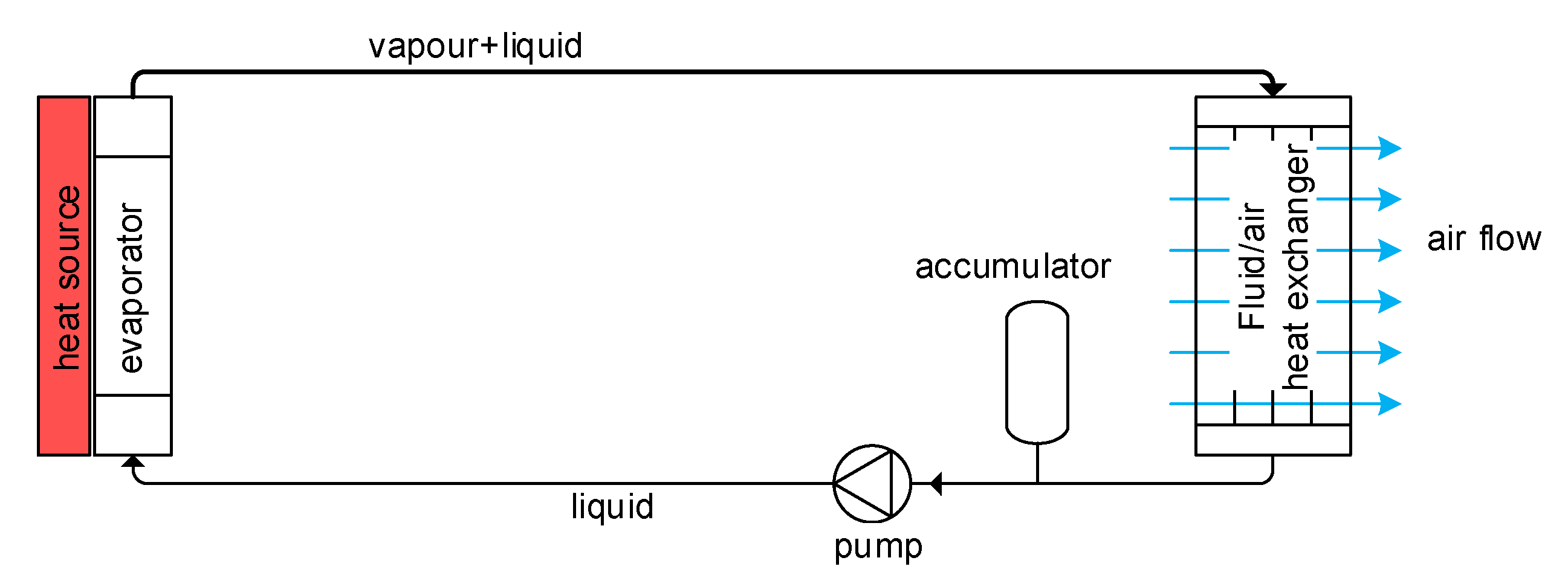

1.2. What Is a Two-Phase Pumped Cooling System?

- The required mass flow is an order of magnitude smaller. This results in much lower electrical power consumption of the pump and a much smaller pump mass. Also, the piping diameter can be smaller, which reduces the overall mass of the system.

- Freezing of the fluid under low ambient temperatures (-55 °C) is not possible, since the freezing points of fluids that are used for two-phase cooling are much lower (typically lower than -80 °C) than the freezing point of EGW (approximately -45 °C).

- Due to the low freezing point and high heat transfer coefficient of two-phase fluids, it is easier to use the waste heat from the fuel cell to warm liquid H2 before it enters the fuel cell.

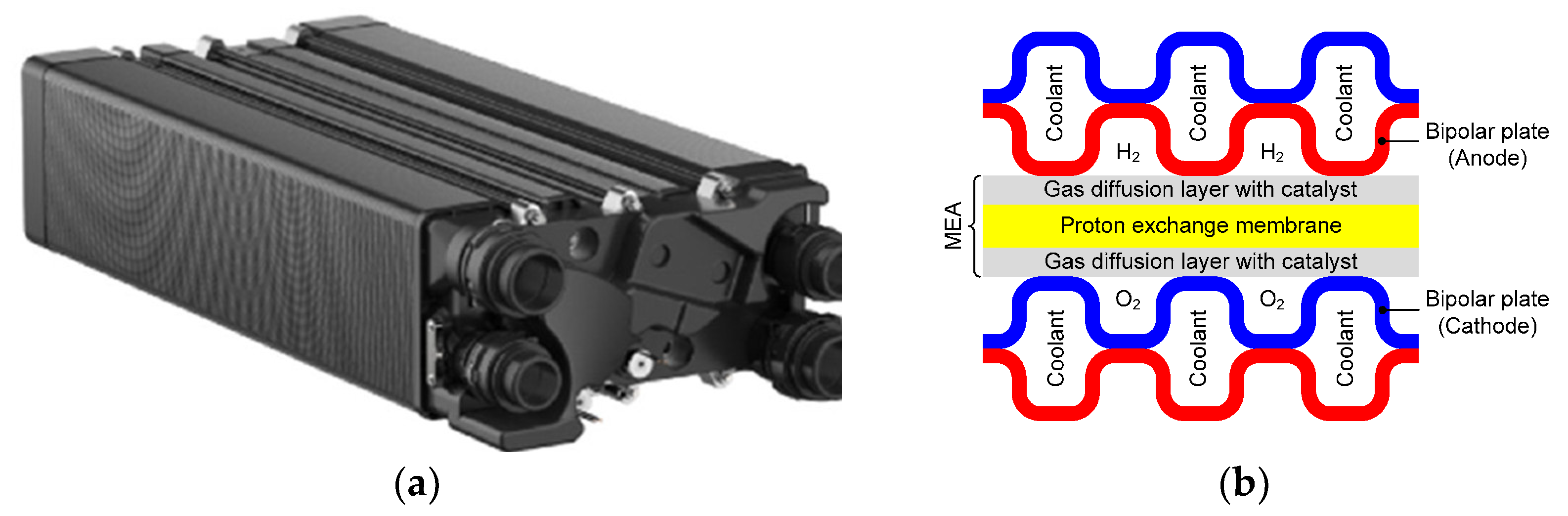

1.3. Heat Source

1.4. Heat Sink

2. Analyses Methods

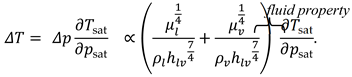

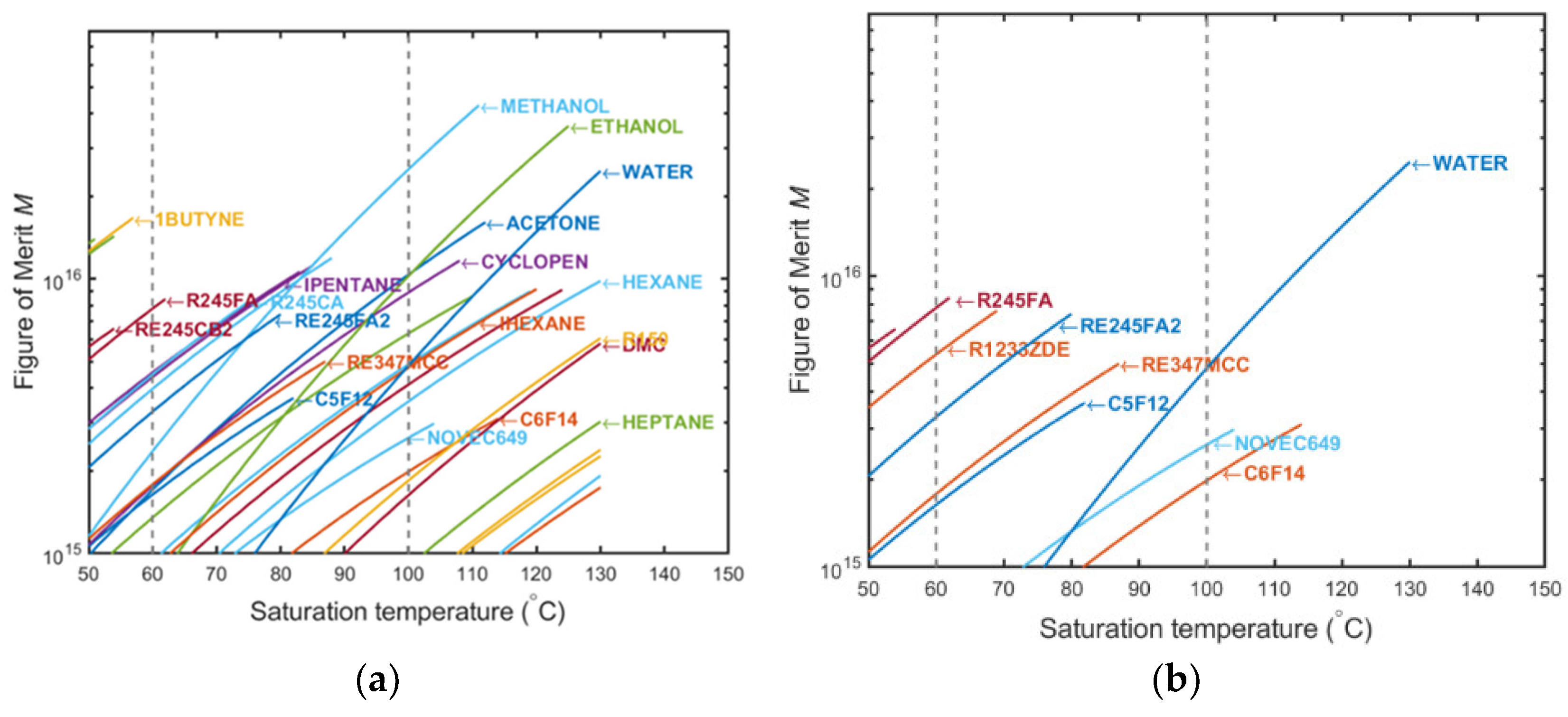

2.1. Fluid Preselection with ‘Figure of Merit’

2.2. System Analysis Tool

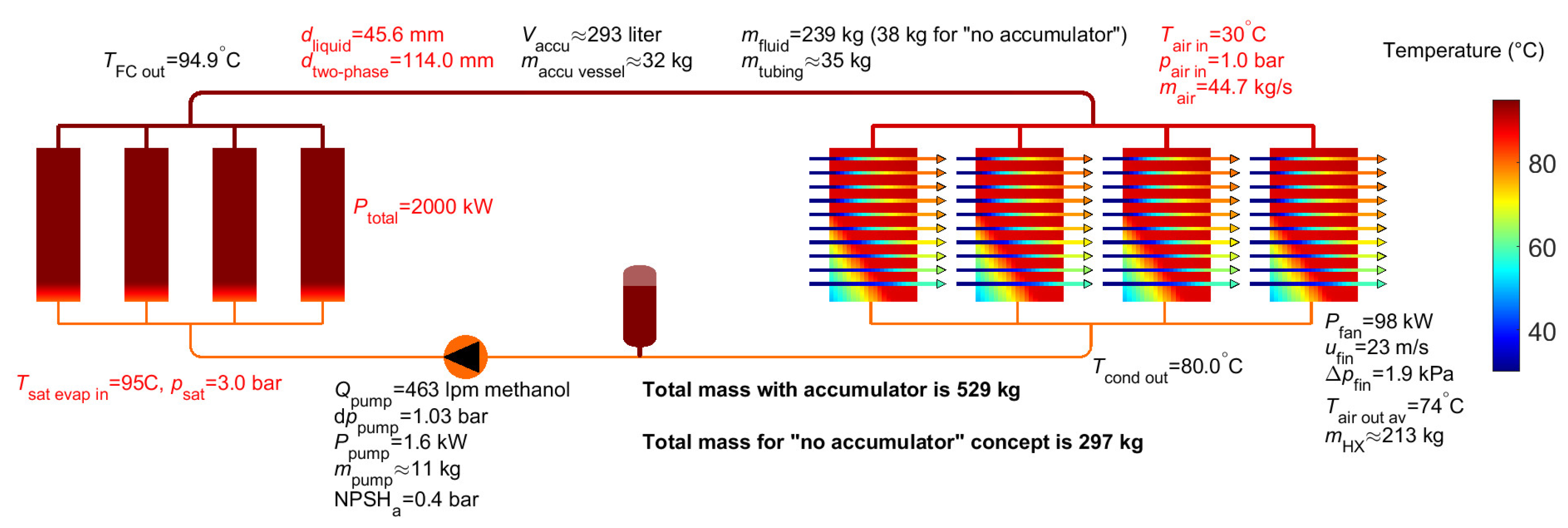

- Total heat rejection during take-off: 2 MW

- Maximum power consumption (fans and pumps): 100 kW

- Air temperature during take-off: 30 °C

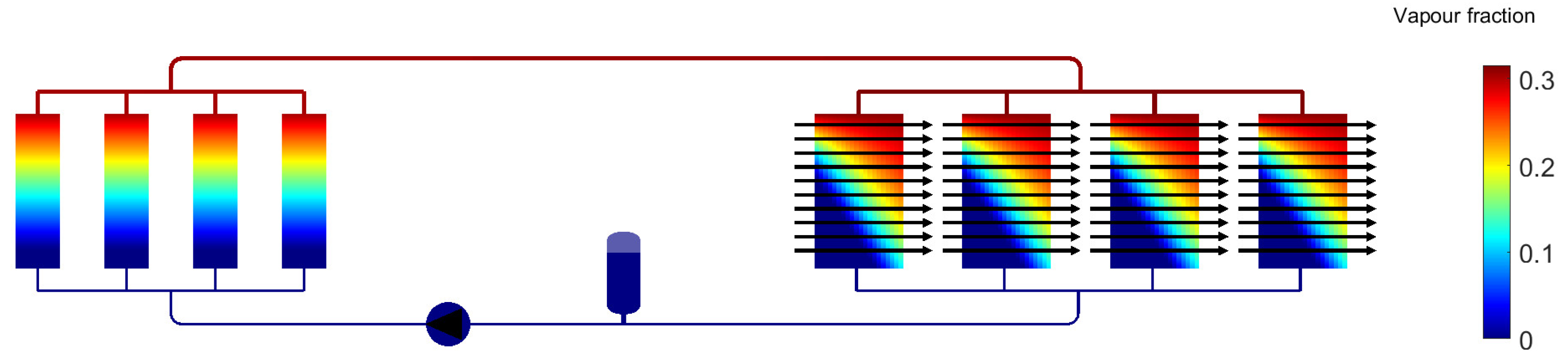

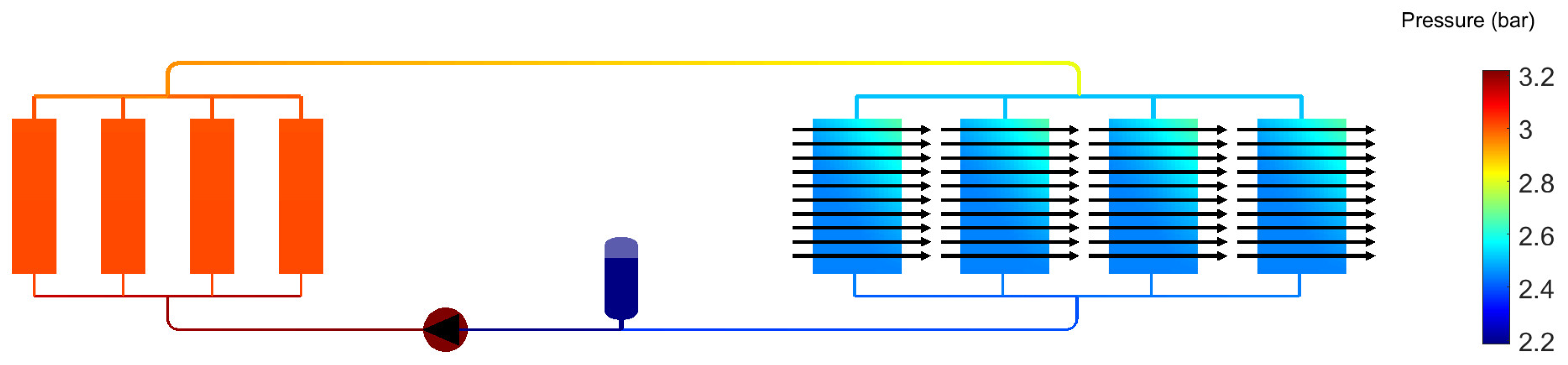

3. Results for Two-Phase Methanol

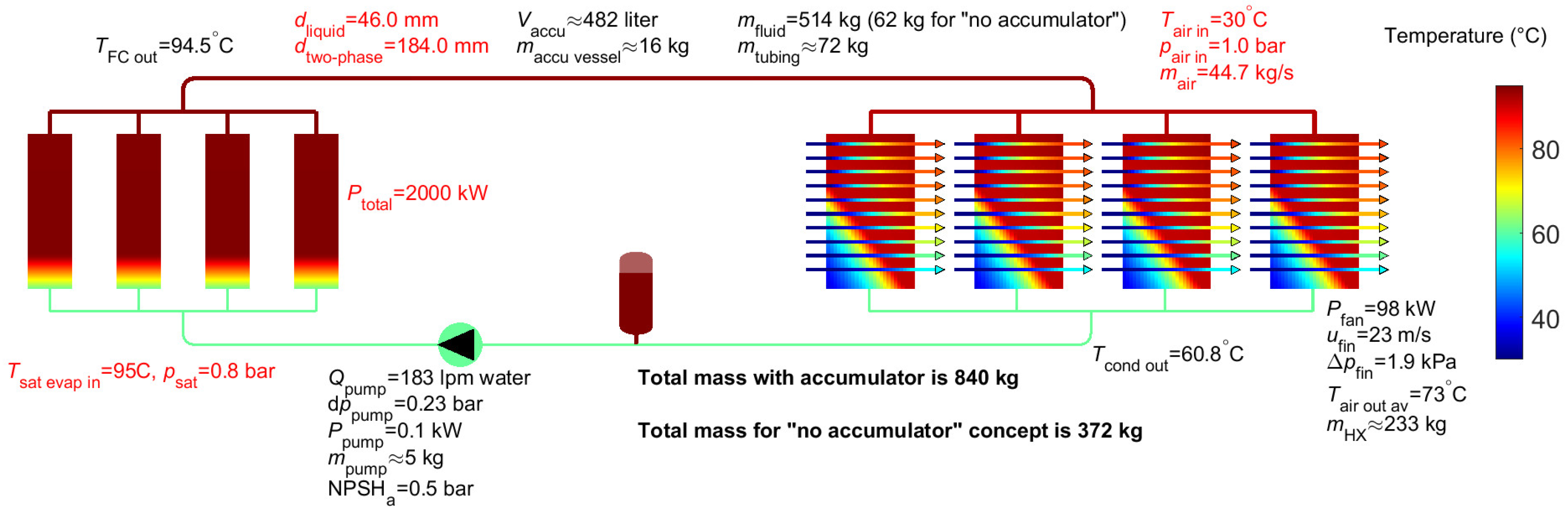

4. Results for Two-Phase Water

- FLUID.name=‘water’ instead of ‘methanol’, see Appendix A

- constant.d_twophase=178e-3 instead of 114e-3

- constant.d_liquid=constant.d_twophase*0.25 instead of constant.d_liquid=constant.d_twophase*0.4

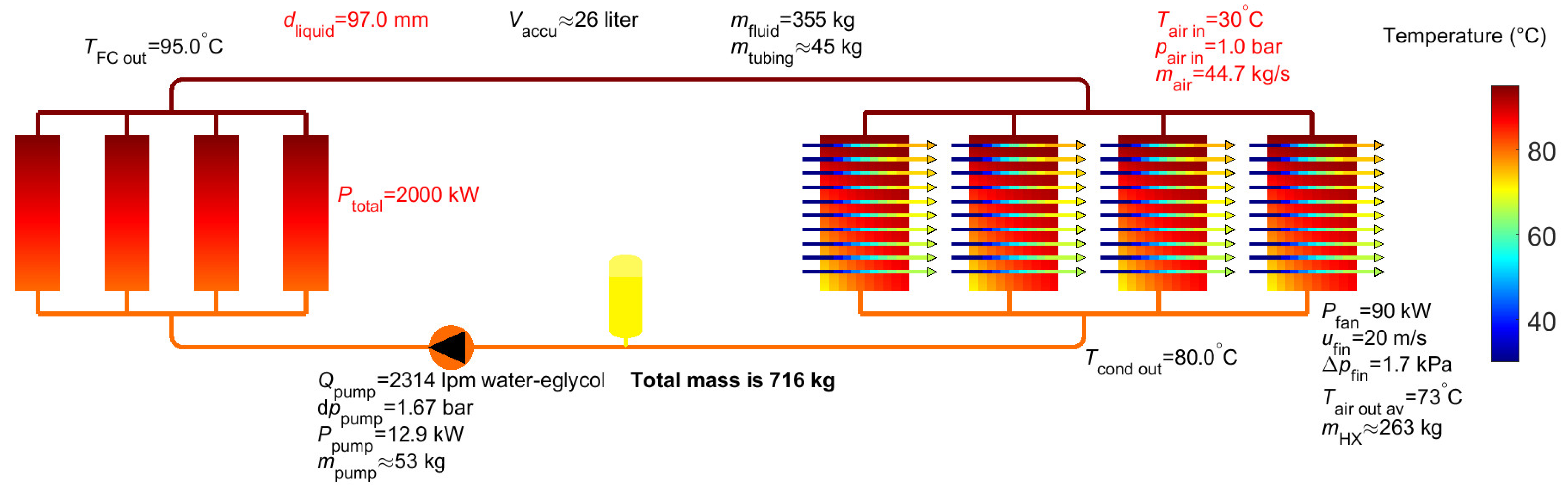

5. Results for Liquid EGW Mixture

- FLUID.cooling_type=1 instead of 2 (2=two-phase cooling, 1=liquid cooling)

- FLUID.name=‘water-eglycol’ (40-60% mixture) instead of ‘methanol’

- constant.d_twophase=97e-3 instead of 114e-3

- The size of the air HX in the direction of the airflow is increased with 10%: HX.L = 0.21*1.1 instead of 0.21

- The width of the air HX is increased with 15%: HX.W = 0.75*1.154 instead of 0.75

6. Discussion and Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A Input for System Analysis

Appendix A.1 Simulation Parameters

Appendix A.2 Geometry Parameters

Appendix B Mass Estimation

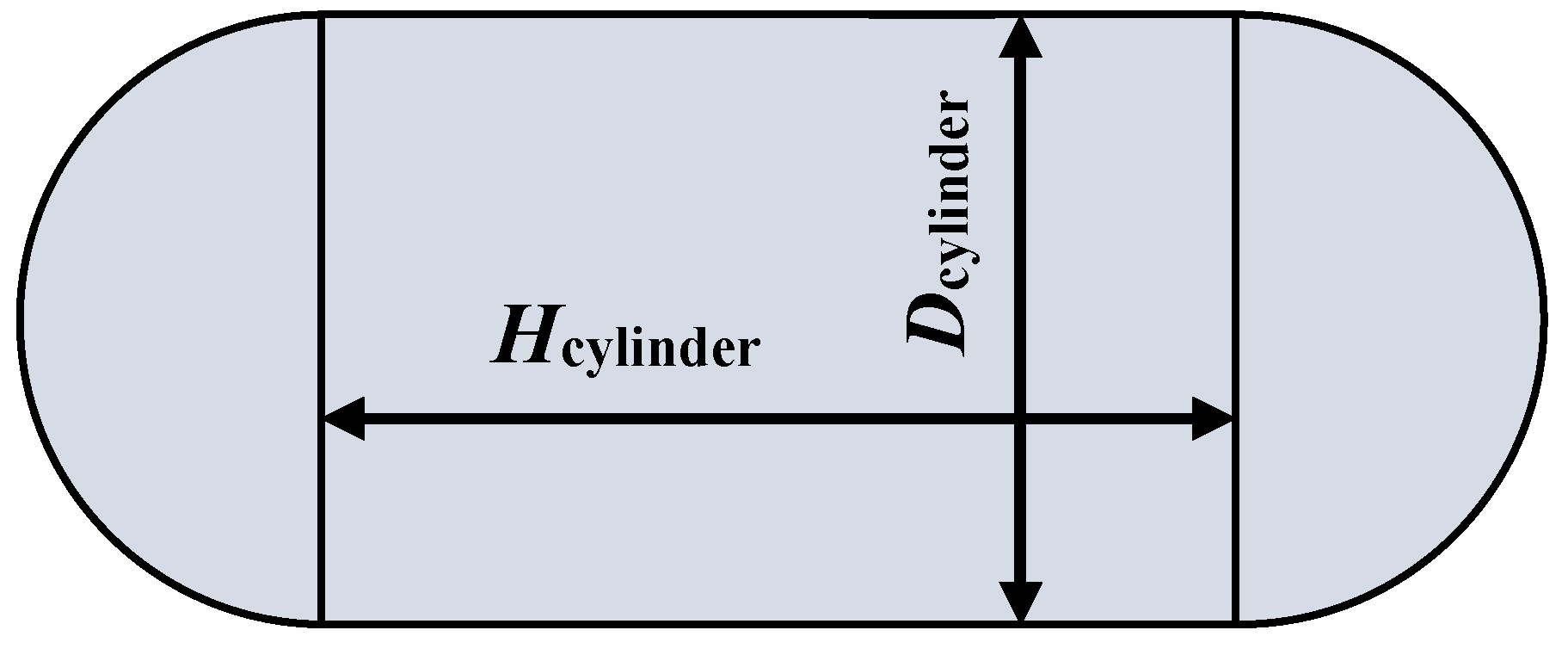

Appendix B.1 Accumulator Vessel

Appendix B.2 Tubing

Appendix B.3 Pump

Appendix B.4 Fluid

Appendix B.4 Ram Air Heat Exchanger

References

- EKPO Fuel cell stacks. Available online: https://www.ekpo-fuelcell.com/en/products-technology/fuel-cell-stacks (accessed on 22 10 2024).

- Neto, D.M.; Oliveira, M.C.; Alves, J.L.; Menezes, L.F. Numerical study on the formability of metallic bipolar plates for Proton Exchange Membrane (PEM) Fuel Cells. Metals 2019, vol. 9, p. 810.

- van Gerner, H.J.; van Benthem, R.C.; van Es, J.; Schwaller, D.; Lapensée, S., Fluid selection for space thermal control systems. 44th International Conference on Environmental Systems 2014.

- Lemmon, E.; Huber, M.; McLinden, M. NIST Standard Reference Database 23: Reference Fluid Thermodynamic and Transport Properties-REFPROP, Version 9.1,” National Institute of Standards and Technology, Standard Reference Data Program, Gaithersburg.

- NFPA 704 Standard System for the Identification of the Hazards of Materials for Emergency Response. Available online: https://www.nfpa.org/Codes-and-Standards/All-Codes-and-Standards/List-of-Codes-and-Standards. (accessed on 18 02 2021).

- van Gerner, H.J.; Braaksma, N.; Transient modelling of pumped two-phase cooling systems: Comparison between experiment and simulation, ICES-2016-004. 46th International Conference on Environmental Systems 2016.

- van Gerner, H.J.; Bolder, R.; van Es, J. Transient modelling of pumped two-phase cooling systems: Comparison between experiment and simulation with R134a, ICES-2017-037. 47th International Conference on Environmental Systems 2017.

- Donders, S. N. L.; Banine, V. Y.; Moors, J. H. J; Verhagen, M. C. M.; Frijns, O. V. W.; van Donk, G.; van Gerner, H. J. Thermal conditioning system for thermal conditioning a part of a lithographic apparatus and a thermal conditioning method, Patent US8610089, 2013.

- van Gerner, H.J.; Luten, T.; Scholten, S; Mühlthaler, G.; Buntz, M.B. Test results for a novel 20 kW two-phase pumped cooling for aerospace applications. Energies 2024. (not yet published).

- PFAS ban affects most refrigerant blends. Available online: https://www.coolingpost.com/world-news/pfas-ban-affects-most-refrigerant-blends/ (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- ECHA, European Chemical Agency; Submitted restrictions under consideration. Available online: https://echa.europa.eu/restrictions-under-consideration/-/substance-rev/72301/term (accessed on 24 January 2024).

| Methanol | RE347mcc (HFE-7000) | water | Novec 649 | Fluorinert 72 (C6F14) | |

| NFPA (health-flammability) [5] | 1-3 | 31-0 | 0-0 | 31-0 | 1-0 |

| Global Warming Potential | ~0 | 530 | ~0 | 1 | 9300 |

| Saturation pressure at 95 °C (bara) | 3.0 | 6.0 | 0.8 | 3.9 | 3.1 |

| Saturation pressure at 60 °C (bara) | 0.85 | 2.4 | 0.20 | 1.5 | 1.1 |

| Saturation pressure at 20 °C (bara) | 0.13 | 0.59 | 0.02 | 0.33 | 0.24 |

| Triple point (°C) | -97 | -122 | 0 | -108 | -86 |

| Heat of evaporation hlv (kJ/kg) | 1035 | 104 | 2270 | 72 | 73 |

| Specific heat Cp (kJ/kgK) | 3.1 | 1.4 | 4.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| Liquid density ρl (kg/m3) | 717 | 1184 | 962 | 1361 | 1446 |

| Density ratio ρl/ρv | 208 | 24 | 1915 | 28 | 36 |

| conductivity kl (W/m K) | 0.19 | 0.05 | 0.68 | 0.05 | 0.06 |

| ∂Tsat/∂psat (°C/bar) | 10.1 | 6.8 | 31.8 | 9.9 | 12.2 |

| Methanol | water | Novec 649 | Fluorinert 72 (C6F14) | Liquid EGW | |

| Accumulator volume2 | 293 litres (-) | 482 litres (-) | 476 litres (-) | 542 litres | 26 litres |

| Pump flow | 463 lpm | 183 lpm | 1741 lpm | 1635 lpm | 2314 lpm |

| Pump power | 1.6 kW | 0.1 kW | 6.6 kW | 4.2 kW | 12.9 kW |

| Triple point (°C) | -97 °C | 0 °C | -108 °C | -86 °C | ~ -48 °C |

| Mass fluid2 | 239 kg (38 kg) | 514 kg (61 kg) | 810 kg (260 kg) | 992 kg (311 kg) | 355 kg |

| Mass tubing | 35 kg | 72 kg | 75 kg | 91 kg | 45 kg |

| Mass pump | 11 kg | 5 kg | 40 kg | 38 kg | 53 kg |

| Mass accumulator2 | 32 kg (-) | 16 kg (-) | 61 kg (-) | 56 kg (-) | neglected |

| Mass air heat exchanger | 213 kg | 233 kg | 226 kg | 232 kg | 263 kg |

| Total mass2 | 529 kg (297 kg) | 840 kg (372 kg) | 1212 kg (601 kg) | 1409 kg (671 kg) | 716 kg |

| 1 | The NFPA health safety classification code of 3 is due to emergency situations where the material may thermally decompose and release Hydrogen Fluoride. Under normal conditions, HFE-7000 and Novec 649 are non-toxic. |

| 2 | The value between brackets is for the ‘no accumulator’ concept. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).