1. Introduction

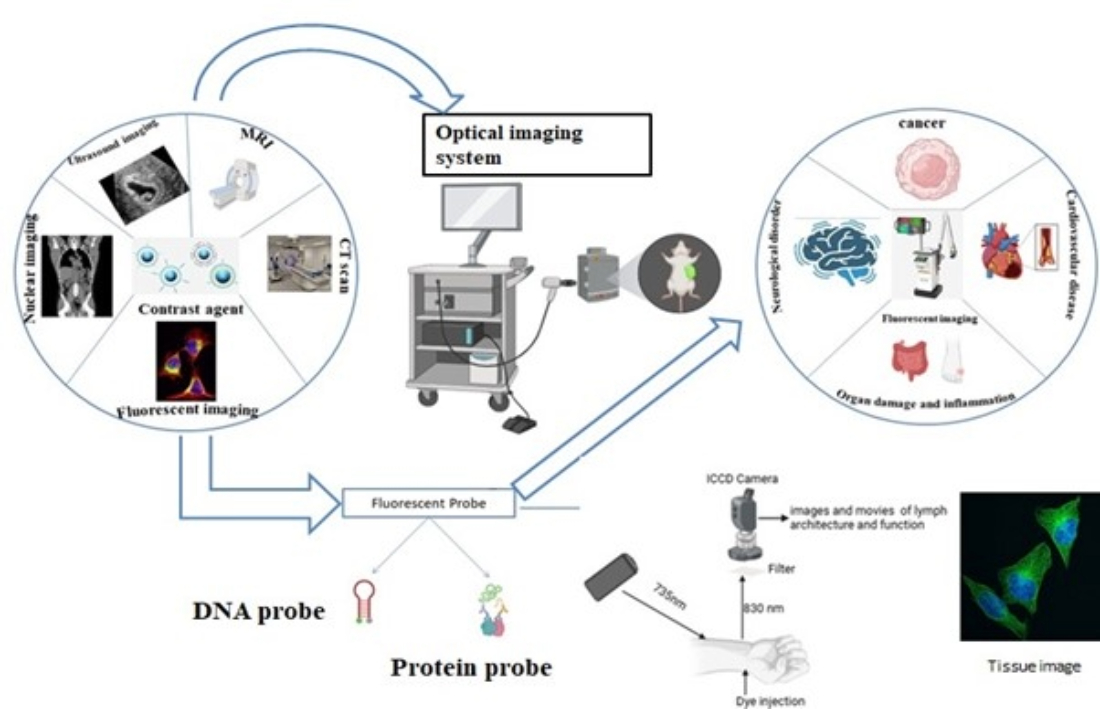

A non-invasive method for looking within the body is optical imaging, like x-rays. Optic imaging uses visible light and the special characteristics of photons to produce finely detailed images of microscopic structures, such as cells, molecules, organs, and tissues, in contrast to x-rays, which employ ionizing radiation. Patients' radiation exposure is greatly decreased using optical imaging, which uses non-ionizing radiation such as visible, ultraviolet, and infrared light. Compared to ionizing radiation techniques like x-rays, this makes it extremely safe for frequent use in tracking the course of a disease or the outcome of treatment.

Moreover, optical imaging works especially well for assessing different soft tissue attributes. Considering the various ways soft tissues absorb and reflect light, it can detect metabolic abnormalities, which are frequently early indicators of aberrant organ and tissue function.[

1] and the term optical imaging refers to the variety of the methods that visualize tissue optical properties by light absorption, scattering and fluorescence emission using UV to NIR light and Numerous optical disease detection probes have been developed and assessed for their ability to generate disease-specific optical signals in the tissue. They include a variety of biocompatible probes made from cyanine dyes, tetrapyyroles, lanthanide chelates, and other substances. Other probes are being developed based on the target and are target-specific, which is most useful for diagnostic purposes. These non-invasive techniques are crucial for the future.[

2] and there are novel optical imaging technologies have been sparked by the development of sensitive charge-coupled device technology and laser technology as well as sophisticated mathematical modelling of photon propagation in tissue and there currently fast growing is 3D quantitative fluorescence mediated tomography and fluorescence reflectance imaging and wide range of novel optical contrasting techniques that are intended to produce molecular contrast within a living creature and are rapidly emerging in tandem with these technological advancements. A new range of instruments are being developed for in-vivo molecular diagnostic which ultimately produced by the combination of technological developments in light detection and improvements of optical contrast medium. [

3] Endoscopy, optical coherence tomography (OCT), photoacoustic imaging, diffuse optical tomography (DOT), Raman spectroscopy, and super-resolution are among the several kinds of optical imaging techniques.

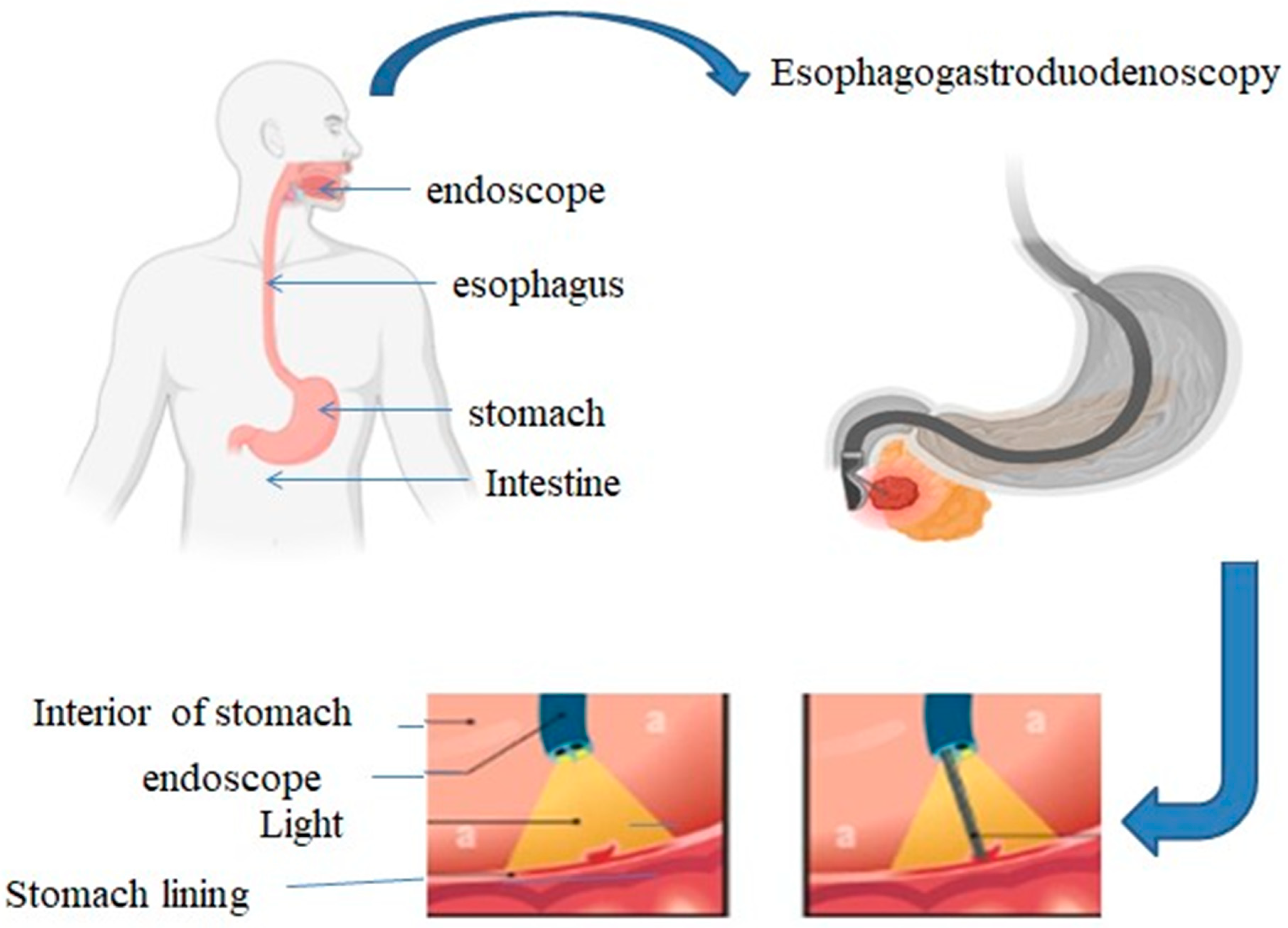

Endoscopy is one of the techniques which we used to diagnose symptoms like pain, difficulty swallowing or bleeding in the gastrointestinal tract and an endoscope can be inserted through the patient’s mouth and into the digestive cavity and for this we use flexible tube equipped with a light source [

2] and there are various other type under the endoscopy which is based on the area of the body like gastroscopy which is used to investigate the esophagus, stomach and part of the intestine, Colonoscopy is the next one that is used to examine large intestine and rectum, Bronchoscopy which is for lungs and airways, Cystoscopy which is used for the bladder through urethra, Hysteroscopy which is used to examine the uterus via vagina and Capsule endoscopy which involve swallowing a capsule with a camera to capture images of the digestive tract and we use this to diagnose various disease like cancer or inflammatory bowel disease or any gastrointestinal tract related disease and we can use it to remove tumor or to place stents in narrowed passage.[

4,

5,

6]

Figure 2.

gastroscopy which shows the oesophagus, stomach, and upper portion of the small intestine are examined by inserting a flexible tube with a camera into the mouth. This process is employed to identify and address a number of gastrointestinal disorders.

Figure 2.

gastroscopy which shows the oesophagus, stomach, and upper portion of the small intestine are examined by inserting a flexible tube with a camera into the mouth. This process is employed to identify and address a number of gastrointestinal disorders.

Apart from the endoscopy there are other techniques like optical coherence tomography which is used for getting images beneath the skin such as sick tissue; this method produces images of the tissue beneath the skin and Diffuse optical tomography is also the method that approach is non-invasive and used near infrared light to assess blood oxygen saturation and total hemoglobin concentration among other attributes they can be used for breast cancer imaging, brain functional imaging and stroke detection and other techniques that are available are Raman spectroscopy.[

2] optical imaging holds a very promising efficacy and specificity and to maintain this we need to improve contrast agents that is used to make structure or processes more visible by making them stand out against the surrounding tissue, [

7] another point is that it is used target specific molecules, cells, or tissue [

8] from this we can enhanced sensitivity, diagnostic accuracy and therapeutic monitoring.[

9,

10] and Medical optical imaging is a non-invasive diagnostic technique that uses light to visualise the body’s structures and functions. [

11] Optical imaging modalities give us information on cellular and molecular processes. Examples of these modalities are fluorescence imaging, near-infrared spectroscopy and tomography. [

12] Optical imaging is useful for cancer screening as well as tumour location and resection by identifying human tumours. Optical imaging in neonatal care has shown potential in diagnosing conditions like stroke and intraventricular haemorrhage, and on-going observation of very sick infants is being explored. [

13] Because it can give us both qualitative and quantitative information at the cellular and molecular level, optical imaging is very useful for cancer identification. 3D imaging is becoming more common in this field which will improve tumour cell localisation, distribution and volume assessment. Optical imaging has many biomedical and clinical applications as a fast, sensitive and non-invasive imaging modality. [

14,

15]

Contrast agents, often known as contrast media, are substances used in optical or medical imaging that enhance the visibility of internal body structures. Many types of contrast agents, such as iodine-based contrast agents, barium sulphate-based contrast agents, gadolinium-based contrast agents, and negative contrast agents, are vital because they play a critical role in visibility during medical diagnosis. Their ability to enhance the contrast between various tissues makes it easier for medical personnel to spot anomalies and diagnose illnesses, which is why they are essential in diagnostic procedures. [

16,

17]

Fluorescent probes are key factor because they allow you to see physiological conditions and real-time cellular processes. Small fluorescent probes with high sensitivity and low biological interference have been the focus of recent research. With longer lifetimes and bigger Stokes shifts, these probes—like excimer-based fluorescent probes—are useful for many bio-analytical applications. [

18] Further improving their sensitivity and specificity for imaging within specific organelles is the development of probes that respond to changes in subcellular microenvironments or biomarkers [

19]. These probes in optical imaging techniques such as super-resolution microscopy have made it simpler to see proteins at the nano scale. In conclusion, the creation of fluorescent probes is advancing optical imaging and opening up new avenues for the study of biological systems. [

20].

2. Principle of Optical Imaging

Optical imaging is primarily about using light to produce and project structures and objects into space as images. Employment of optical imaging methods turn on images from living cells or samples through slope. The object under examination can absorb, scatter or emit light which helps in providing contrast and also availing some specifics relative to its properties. [

21].

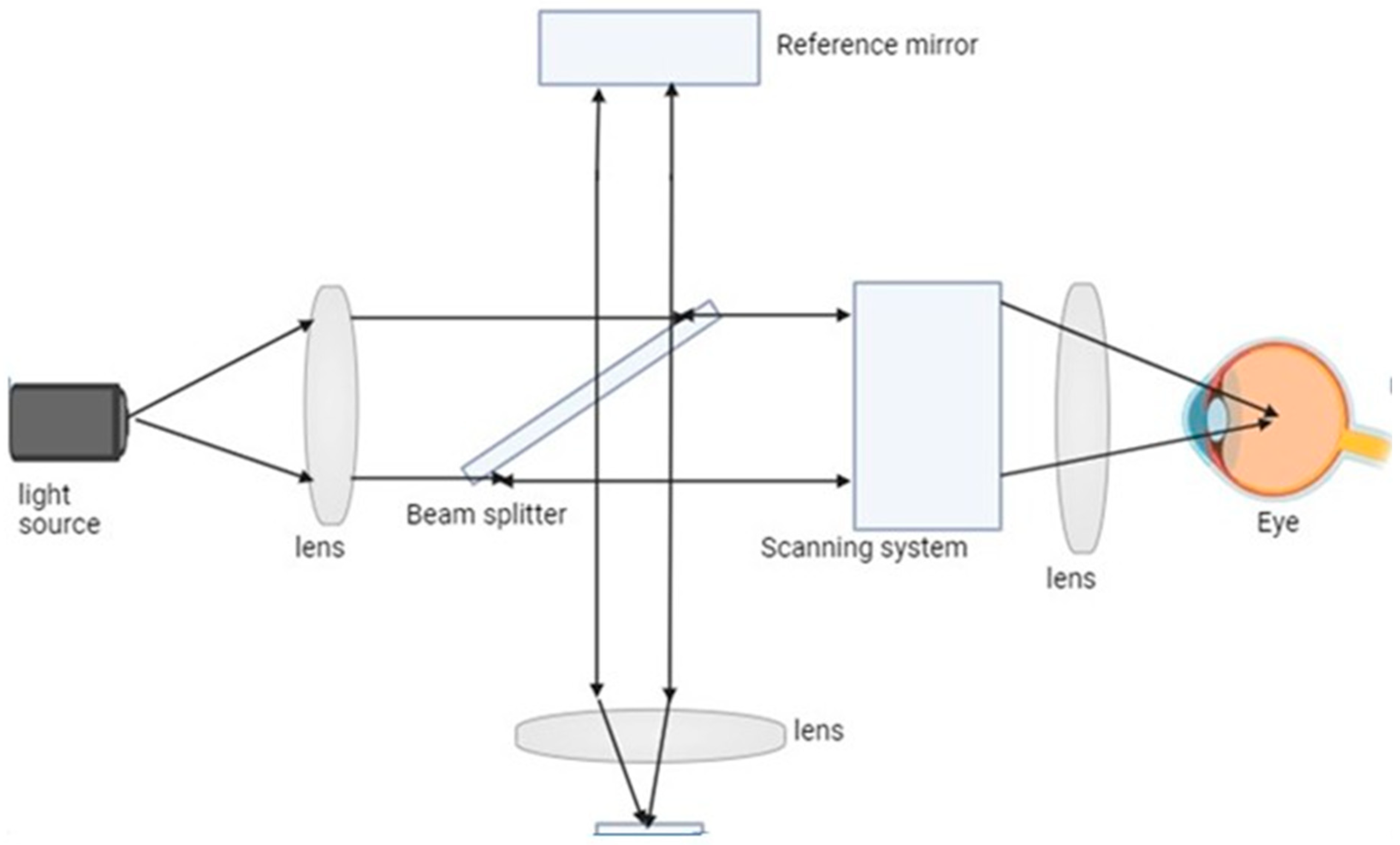

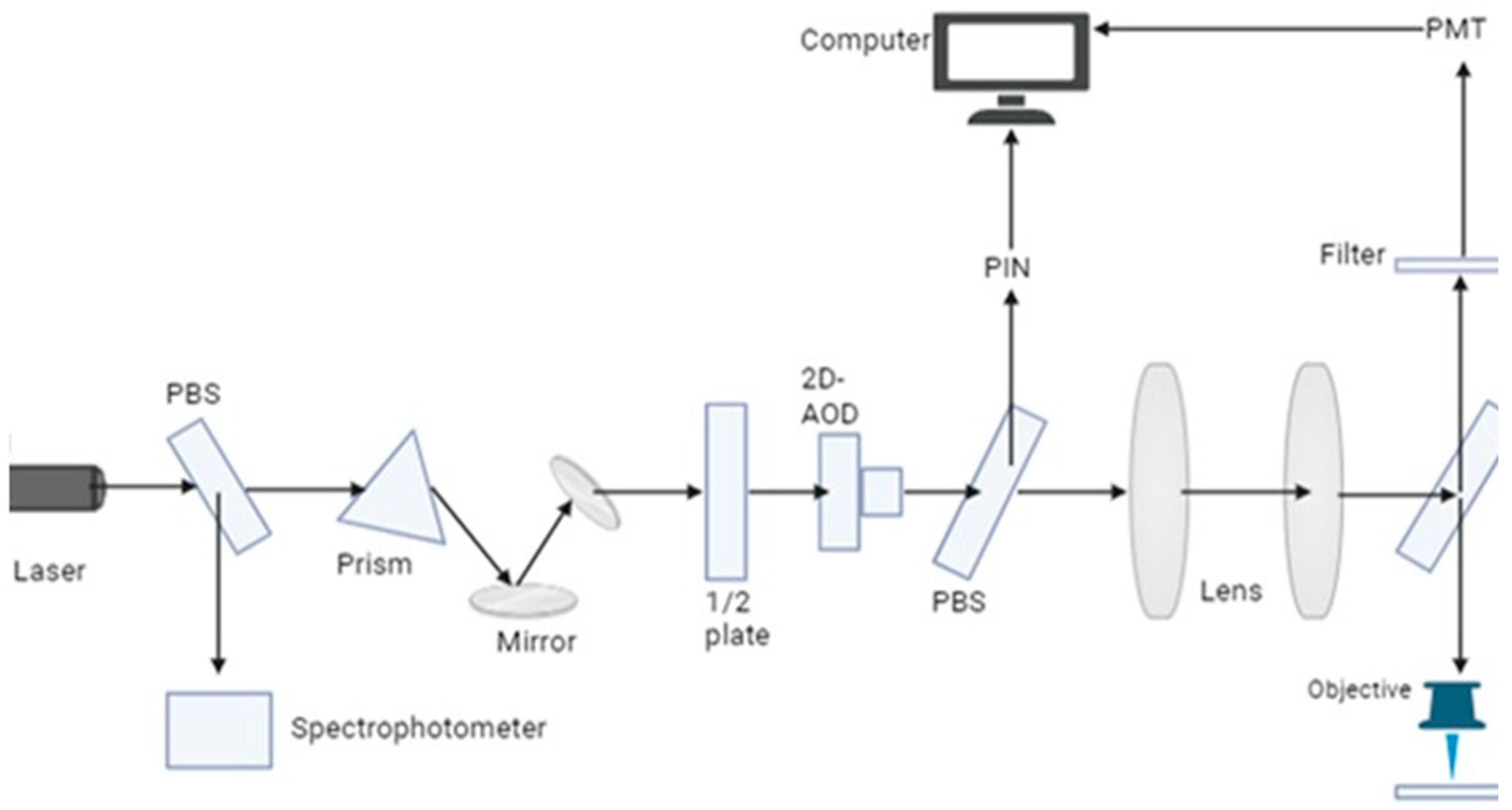

Figure 3.

A scanning optical imaging system is depicted in the diagram. This kind of device uses a concentrated laser beam to scan a sample and gather the dispersed light that results. An image of the sample is then created by analyzing the light that was gathered.

Figure 3.

A scanning optical imaging system is depicted in the diagram. This kind of device uses a concentrated laser beam to scan a sample and gather the dispersed light that results. An image of the sample is then created by analyzing the light that was gathered.

Key principle of this optical imaging is light interaction with tissue like our tissue absorb light at particular wavelength which then can be excited and scattered them and when any biological sample encounters the light it will scattered them in a different direction and this scattering provide the information of tissue structure and composition and optical imaging analyse the pattern of the light which is scattered and then reconstruct the image of a internal structure. Many optical imaging rely on the fluorescence where a specific molecule absorb the light and give the signal in the form of colour or graph etc. and optical imaging method can be used diffraction and diffusion in this diffraction provide high resolution but are limited to superficial layers of tissue which diffusion based method can penetrate deeper but with reduced spatial resolution. [

22,

23]

3. Contrast Agents

A contrast agent is a substance that managed to the human body during medical imaging to enhance the contrast and clarity of specific targets or structures. Depending on the method of imaging being used, it is usually taken by mouth or intravenous route or applied to other parts of the body. The basic principle behind these agents lies in their ability to alter the way tissues interact with imaging systems, thus improving the capability to differentiate between various types of structures or regions of interest within those areas. Furthermore, they can improve certain imaging techniques like CT scans, MRIs, ultrasound and optical imaging with respect to sensitivity, specificity and resolution. [

24,

25]For a better imaging quality in optical imaging, various types of contrast agents tend to be used. There are several important contrast agent types which are utilized in optical imaging like Gold nanoparticle which has High resolution may be produced when gold nanoparticles with anisotropic silica nanoshells are used as contrast agents in photoacoustic imaging [

26] another this Quantum Dots which is an advance technology for in-vivo imaging. They are particularly valuable for cancer imaging and guidance during surgeries performed on patients with the disease. And Organic Semiconducting Agents is used Due to their easily convertible characteristics and chemicalisterability, this group of agents that includes small-molecule compounds and nanoparticle derivates has been designed purposely for deep-tissue [

27] and lipid emulsions is used because of their higher reflectivity and signal transmission. [

28]

To improve visibility and contrast of certain targets or tissues in optical imaging, a contrast agent is used which helps them become more discernible. Contrast agents are chemicals administered intravenously (IV) that interact with the optical imaging system to produce detectable signals. Patients may receive exogenously introduced compounds like colored substances or small specks of matter, whereas endogenous symbols sometimes involve naturally present fluorescent or color-bearing substances. Contrast materials allow the differentiation between several components or areas of concern due to their influence on visible tissues’ optical qualities (e.g., what extent they can absorb/play around with incoming light). In this manner, they have contributed towards improving sensitivity, specificity and resolution of methods used for optical imaging (examples include OCT, SPECT) and they can help in identification of disease and facilitate the observation of cellular and molecular processes. [

29,

30,

31,

32]

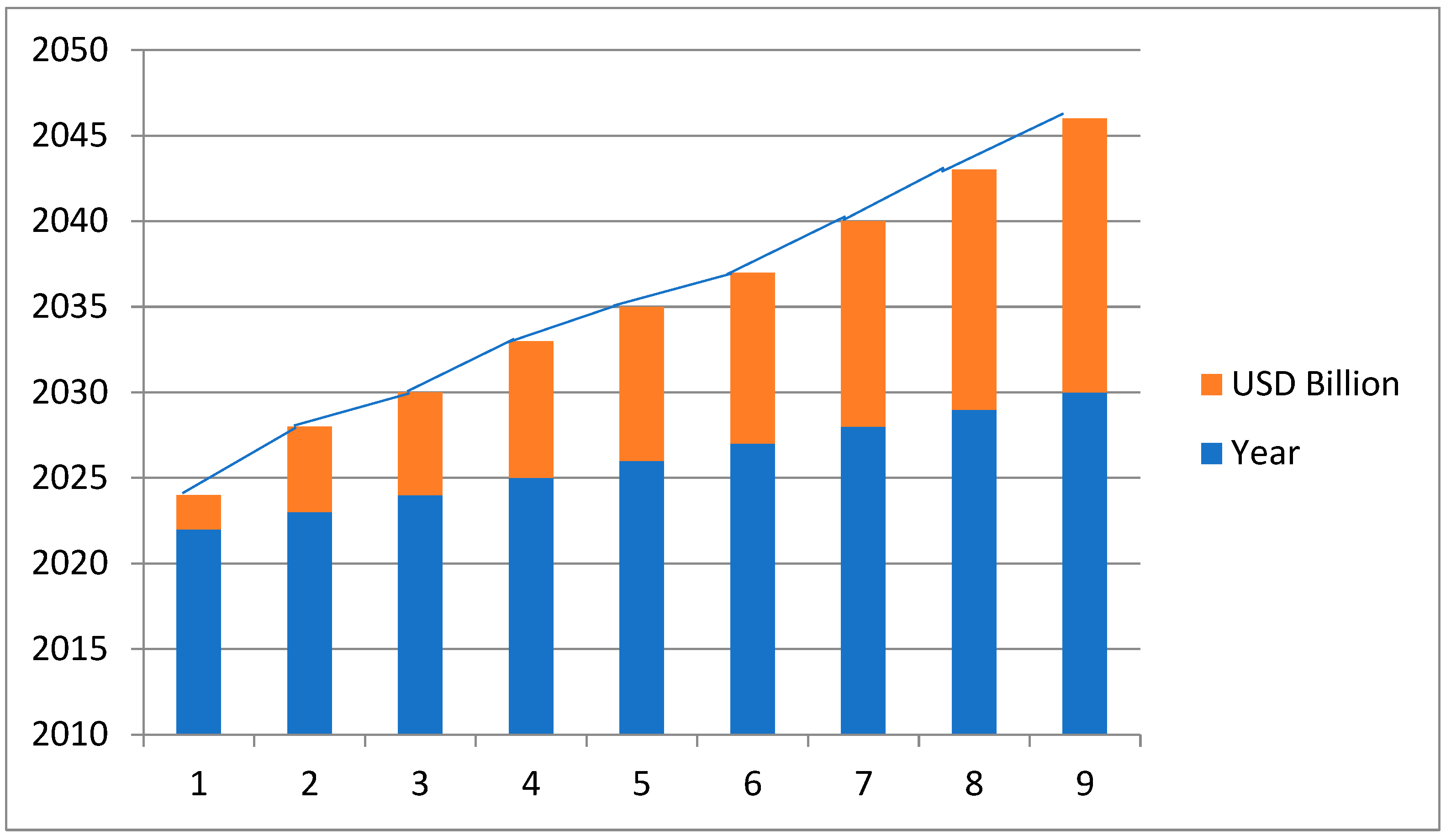

Market value of the contrast agent is very high and its global market growth is also very high due to the advancements in medical imaging technology and increasing prevalence of chronic disease.

The market for contrast agents was estimated to be worth USD 6.28 billion in 2023.It is projected to expand at a 7.98% cumulative annual growth rate (CAGR) to reach around USD 10.74 billion by 2030. Among the primary drivers of this trend are the aging of the global population, the increase in complex comorbidities and chronic illnesses, and the growing prevalence of diagnostic imaging procedures such as CT and MRI scans. [

33,

34]

4. Fluorescence Imaging

The fluorescent imaging is a technique of imaging sub-cellular components which employs fluorescence imaging study in biological sciences and clinical practices. In this process fluorescent probes or dyes are excitable with light of particular wavelength. Because of this technology, researchers and clinicians can study cellular metabolism, protein interactions, as well as the course of diseases. For fluorescence imaging there are different imaging modalities like tomography, endoscopy or microscopy. This has the potential to completely change diagnosis and surgery by providing real time information during surgery and intra-operative decision guidance. [

36,

37]

For fluorescent imaging we are using certain fluorescent dyes or probes like - Fluorescein is one of the most common green fluorescent dyes that are brilliant and highly photostable. It is usually labeled with antibodies and nucleic acids. Rhodamine is a red fluorescent dye which is often used to label proteins, nucleic acids and membranes. The cyanine dyes come in colors such as red (Cy3), far-red (Cy5), and near infrared (Cy7). They are often used for multiplexing as well as live-cell imaging. Alexafluor dyes are fluorescent dyes that have a broad color range and excellent photostability. They are commonly used for immunofluorescence and live-cell imaging. Quantum dots are semiconductor nanoparticles emitting a narrow spectrum and showing strong fluorescence. They are frequently used for multiplexing and prolonged imaging. Indocyanine green (ICG) is a near-infrared fluorochrome used in imaging organs and deep tissues. [

38,

39]

The process of seeing biological structures and processes with a high level of precision and sensitivity can be achieved through fluorescence imaging. Fluorescent probes, also known as fluorophores, are used in this process. These probes light up when there is a certain wavelength light that they respond to. The principles of fluorescence imaging are Excitation and Emission in this Various wavelengths of light are used for the purpose of exciting different types of fluorophores so as to perform their fluorescence imaging function. Specifically, these fluorophores get activated into higher energy levels via absorption of the excitation light responsible for generation and detection purposes. Therefore, a specific emission wavelength arises from the subsequent release of light at an even longer wavelength than that of the excitation photon. This way, an image can be obtained through identification and collection of such emitted light rays. The fluorophores are those types of molecules which can both absorb as well as emit lights with varying wavelengths. Such substances are either organic or inorganic, but it is the organic ones that are usually used in biological imaging because they are compatible with live systems. For example, fluorescent proteins or dyes fall under this category of organic fluorophores while quantum dots serve as inorganic nanoparticles employed for their specific optical properties and Fluorescence is usually visualized by means of light sources that induce excitement in fluorophores. This excitement is followed by the use of optical filters to separate between both excitation as well as emission wavelengths while, finally, after this light collection process has taken place there will always be some kind of detector responsible for picking up all those emitted photons. Depending upon what one need, a microscope or camera or specialized devices may come into play and Fluorescence images are analyzed by applying image processing and analysis techniques to them. Such techniques involve quantifying fluorescence intensity or localization of two or more fluorophores, removing noise and subtracting background signals. The effective interactions at the molecular level can also be explored using advanced approaches such as fluorescent lifetime imaging (FLIM). [

40,

41,

42,

43]

5. Parts of Fluorescence Imaging

Light Source: The light source excites the sample with excitation light. Examples of common light sources are lasers, LEDs, and mercury or xenon arc lamps. [

44] and there are various type of light source like xenon arc lamp which provide broad spectrum illumination and are commonly used in light microscopy and next one mercury vapor lamps and these are known for emitting intense light at specific wavelength which are useful for exciting many standard fluorophore.[

45]

Excitation Filter: The excitation filter is placed along the light path to select a specific wavelength that can induce fluorescence in the sample. It only permits the passage of the desired excitation wavelength.

Dichroic Mirror, also known as a beamsplitter, is a device that allows for the passage of fluorescence while reflecting excitation light towards the sample. It separates the light channels leading to excitation and emission.

The objective lens is responsible for gathering and condensing the emitted fluorescence from the specimen so that it can be viewed on the detector. In addition, it sets the magnification and resolution of the microscope.

The precise wavelength of fluorescence that fluorophores emit is chosen by inserting an emission filter into the emission light path. As a result, all undesired excitation light is blocked out and only the desired fluorescence is allowed through.

Detector: The detector gathers the released fluorescence and transforms it into an electrical signal. In general, photomultiplier tubes (PMTs) and charge-coupled devices (CCDs) are the most often used detectors. [

49]

Imaging System: The imaging system consisting of lenses and mirrors directs fluorescence signal from the sample to the detector which finally forms an image.

Stage: A stage is a platform that holds and positions a sample under the objective lens, allowing precise user adjustments for focus, illumination intensity, and image acquisition parameters. It also facilitates careful movement and scanning of the specimen.[

48]

Control System: The control system includes buttons, knobs as well as computer program.[

46,

47,

50]

6. Types of Fluorescence Imaging

Fluorescence imaging techniques have been utilized in various scientific and medical fields. There are several types, such as:

6.1. Widefield Fluorescence Imaging

The Widefield fluorescence imaging uses a Widefield illumination source which excites the fluorophore present in a sample. A camera or similar device detects emitted fluorescence therefore giving a two-dimensional view of the sample and in the collective observations of numerous fluorescent substances; their analytical role in various clinical practices and scholarly investigations is best epitomized by Widefield fluorescence imaging. By use of fluorescence-emitting probes or natural fluorescence from selected molecules, specific cells or tissue structures observe particular molecules. Widefield fluorescence imaging is a technique that uses the excitation and emission properties of fluorescent molecules. When exposed to certain wavelengths of light known as "excitation light," particular fluorescent molecules in a sample absorb it and transition into an excited state. After a short period these excited states decay back down to their original energy levels and the excess energy is emitted as longer wavelength fluorescence which can then be collected and detected to form an image.

The advancement of this type of fluorescence imaging is High resolution imaging that improved wide-field fluorescence microscopy techniques have enabled the possibility of acquiring high-resolution images up to 100 nm in three dimensions. The accomplishment was realized by the use of powerful image reconstruction methods accompanied by unevenly distributed excitation light patterns, Optical Sectioning that Deeply-resolved imaging techniques and structured illumination microscopy (SIM) are some of the approaches that have been formulated create optical sections and enhance the visibility of structures in dense samples[

56], Real time imaging has High spatiotemporal resolution observation dynamic of biological processes is made possible through development of wide-field fluorescence imaging technologies for real-time observation[

57], high-Throughput Imaging is a method such as axial z-sweep capture using 2D projection images and deep learning-based image restoration have been suggested to enable high-throughput imaging of complex three dimensional substances[

58] and last one is improved Signal-to-noise Ratio and Contrast it is a digital micro mirror devices together with focus sweep attachments have been used to enhance Signal-to-noise ratios and contrasts. The outcome is an improved quality of images. [

58]

6.2. Confocal Fluorescence Imaging

To improve resolution and optical sectioning, confocal microscopy works by using a pinhole aperture to block out-of-focus light. With this technique, fluorescently tagged samples can be captured in 3D at high resolution. Confocal microscope is employed in confocal fluorescence imaging eliminates out of focus light, thus improving image quality. It achieves optical sectioning and improved resolution by pinhole aperture detecting fluorescence emitted from a specific focal plane subsequent to its release into the medium. [

59] Throughout the years confocal fluorescent imaging has evolved greatly. This includes progress in data handling and storage, imaging instruments, fluorescent probes and indicators and designs of microscopes. Thus, enhanced image quality, increased speed of acquisition, and three-dimensional visualization of changing biological processes have been the outcome of these improvements[

60] and The use of confocal fluorescence imaging has various advantages. It provides clear three-dimensional images that are less noisy and have more contrast, it also enables optical sectioning, and allowing for visualization of specific structures within a sample and also, it allows one to analyze the dynamic biological processes in real-time. [

61]

6.3. Multiphoton Fluorescence Imaging

Multiphoton microscopy enables deeper penetration of tissues and reduces phototoxicity by employing longer-wavelength excitation light, usually in the infrared range. Its common applications include thick sample imaging or live animal imaging. [

50,

51] High-resolution imaging of biological materials, including living tissues and cells, is made possible by the sophisticated imaging technology known as multiphoton fluorescence microscopy. The technique is predicated on the idea of multiphoton excitation, which is the simultaneous absorption of several photons by a fluorophore that causes the emission of fluorescence. The idea behind multiphoton fluorescence imaging is to stimulate fluorophores using two or more photons rather than simply one. The excitation occurs at the laser beam’s point of convergence, thus allowing for the precise imaging of localized regions within a medium and the advantages of this technique is Deep Tissue Imaging This is one of the major benefits of multiphoton fluorescence imaging, which allows for deep penetration into tissues. Multiphoton microscopy can visualize thick specimens due to longer wavelengths of excitation light, which facilitates penetration into tissues and reduces scattering, Nonlinear Excitation Multiphoton excitation occurs only at the focal point of laser beams as it is a nonlinear process. Thereby decreasing background noise and enhancing picture quality are among its inherent optical sectioning abilities; Lessened Photographoxicity is observed in multiphoton fluorescence imaging as compared to other techniques used for imaging. There is minimal damage to the nearby cells and tissues since the excitation light happens in a relatively tiny area. Quantitative Imaging: Quantitative data regarding cellular and tissue properties can also be obtained by multiphoton fluorescence imaging. This method can be used to quantify a number of properties, including fluorescence lifespan, intensity, and fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET). [

63]

6.4. Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy (FLIM)

This method measures the fluorescence decay time for fluorophores, providing information on the structural changes, environment and molecular interactions. It is used to study biological functions, protein folding and protein-protein interactions. FLIM is indeed an effective imaging technique that reveals how long fluorophores last in biological samples. Furthermore, it enables one to see and measure molecular interactions, protein interactions and biochemical processes in living cells and tissues. The FLIM technique determines the time for which a fluorophore remains in the excited state before emitting a photon. This makes FLIM a reliable and quantitative imaging technique since the fluorescence lifetime does not depend on the excitation or detection efficiency and concentration of the fluorescent molecules used in microscopy.

Figure 5.

FLIM fluorescence imaging in which laser beam excited the light which is disperse from the prism into different wavelength and direct the light towards the mirror and then filter selects the desired wavelength and excited them and then it focuses on objective lens and on the biological sample being studies and emission filter again select the desired wavelength and then photomultiplier tube detects it and using spectrophotometer we can analyze them.

Figure 5.

FLIM fluorescence imaging in which laser beam excited the light which is disperse from the prism into different wavelength and direct the light towards the mirror and then filter selects the desired wavelength and excited them and then it focuses on objective lens and on the biological sample being studies and emission filter again select the desired wavelength and then photomultiplier tube detects it and using spectrophotometer we can analyze them.

The advantages of this technique are Contrast Enhancement that enhances image contrast by providing more information about the fluorophores’ nearby environment. It also uses Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) to identify protein-protein interactions and to highlight various chemical states. Its application domains are both time domain and frequency domain. While frequency-domain FLIM utilizes modulated detectors coupled with sinusoidal modulation of excitation light, time-domain FLIM applies pulse excitation sources together with time-correlated or time-gated detection systems and Quantitative imaging and multiplexing made possible by FLIM which enables the multiplexing of fluorescent markers having diverse fluorescence lifetimes but identical emission spectra.[

64]

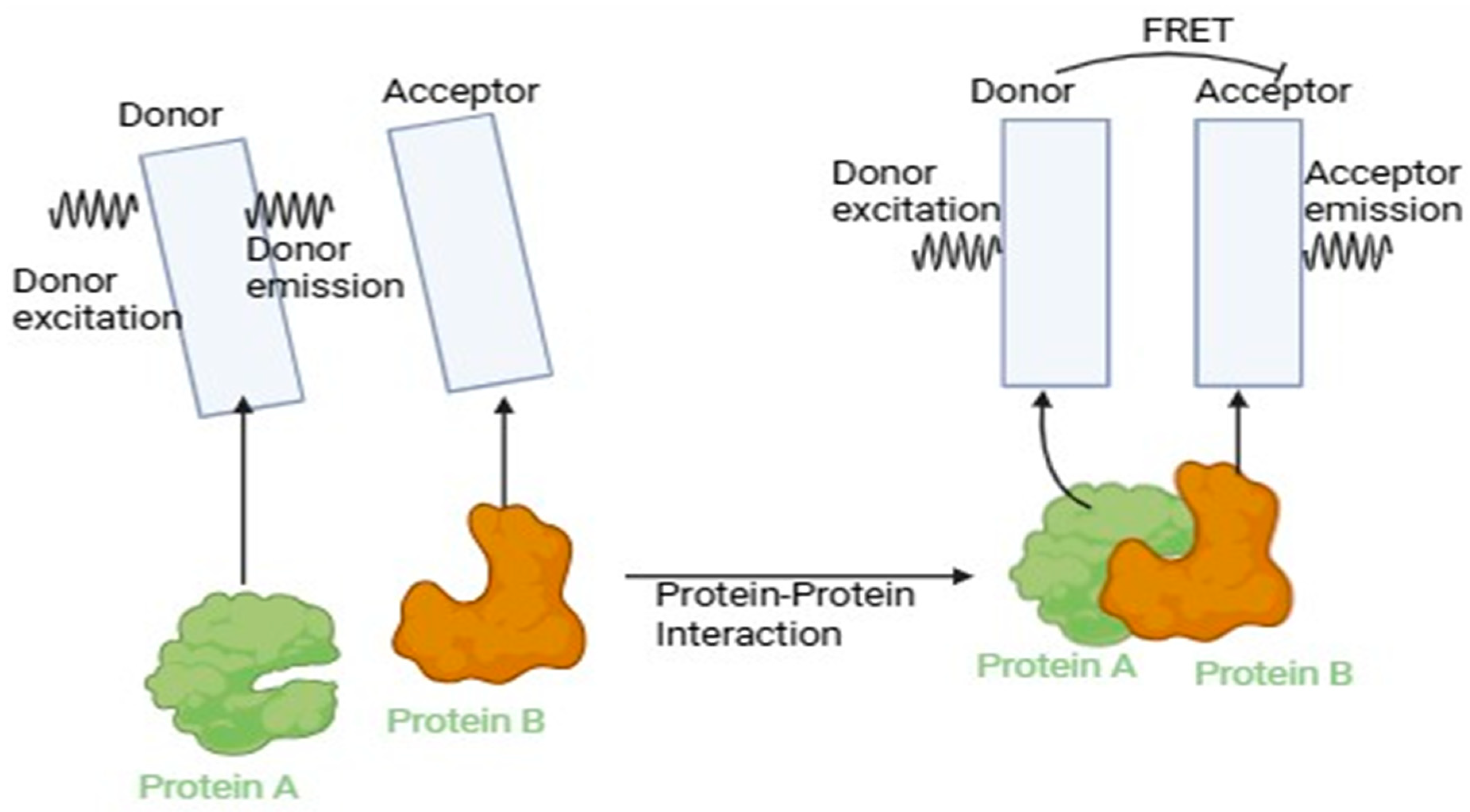

FRET - energy transfer from one neighbouring fluorophore to another using this mechanism. It is used to investigate the forms that proteins take on when they bind to other molecules, the ways in which various signals change over time, and the interactions that occur between them. [

52,

53]. The fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) technology has the potential to be a potent tool for researching the interactions and motions of molecules in biological systems. An excited donor fluorophore gives its energy to a nearby acceptor in a non-radiative manner. FRET is based on the dipole-dipole interactions between acceptor and donor fluorophores. By decreasing donor fluorescence and increasing acceptor fluorescence, the extended dipole mechanism facilitates the energy transfer from one fluorophore to another. The efficiency of fluorescence-based double expansion reaction is influenced by wavelength overlap, distance between the two fluorophores as well as their orientation. [

66]

Figure 6.

Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET), a method for examining molecule interactions and distances at the nanoscale, as depicted in the diagram. When two fluorophores are brought close together, FRET depends on the non-radiative transfer of energy from the donor to the acceptor.

Figure 6.

Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET), a method for examining molecule interactions and distances at the nanoscale, as depicted in the diagram. When two fluorophores are brought close together, FRET depends on the non-radiative transfer of energy from the donor to the acceptor.

The advantages of this technique are Detection of Proximity and Interactions like With FRET; it is possible to recognize the proximity and reactions of different molecules. This technique provides specific information regarding the spatial arrangement, conformational changes, and binding events that occur between proteins. FRET enables the investigation of conformational shifts in proteins as well as DNA-protein and protein-protein interactions [

66], Measurement of Distances the technique is also suitable for measuring nanometer-range distances using FRET. By measuring energy transfer efficiency, it is possible to determine how far away the donor and acceptor fluorophore are from each other. Therefore, FRET is suitable for studying molecular dynamics and structural changes in living organisms [

66], FRET-based biosensors enable real-time observation of biological processes. These sensors can be directed to specific cell regions and provide real-time data on biochemical processes, such as enzyme activity, ion concentrations, and signaling pathways. The utilization of FRET-based sensors has made it possible to visualize and quantify molecular events occurring in living cells.

FRET offers an unparalleled degree of sensitivity due to the efficient energy transfer it facilitates between fluorophore. Small changes in molecular interactions can be quantified while analyte concentrations at low levels can still be detected and A lot of different fluorophores with FRET have been combined together so as to create multicolor imaging. In this way, multiple molecular events or interactions can be identified at once in one sample. [

67,

68]

6.5. Super-Resolution Fluorescence Imaging

These methods can image at a nanoscale by going beyond the diffraction limit of light. STED (stimulated emission depletion) microscopy and SMLM (single molecule localization microscopy) are examples of such techniques. Therefore, one can observe the small details present in cellular structures more accurately with these approaches. Super-resolution fluorescence imaging is a next-generation microscopy technology that exceeds the optical diffraction barrier of traditional optical microscopy, thus allowing for detailed visualization of structures at the sub-Nano scale. It has higher spatial resolution and gives insights into cellular activities as well as molecular interactions. Super-resolution fluorescence imaging relies on specialized fluorophores and imaging methods that meet and exceed the diffraction limit. Numerous super-resolution methods have been developed, such as photo-activated localization microscopy (PALM), single-molecule localization microscopy (SMLM), stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy, and structured illumination microscopy (SIM). These different methods for achieving super-resolution imaging include patterned illumination, single-molecule localization or photo activation and the advantages of this is that it has Best Possible Spatial Resolutions that Basically super -resolution strategies go beyond the diffraction barrier allowing visualization of features that are just a few nanometers, Forensic Structural Information that exposes how the arrangement and orientation of different kinds of molecules in cell structures, The use of super-resolution methods in live-cell imaging makes it possible to study dynamic processes in real time, Multiple Imaging Ability: Certain super-resolution approaches allow simultaneous viewing of multiple targets or molecular interactions through the use of various fluorophore [

70,

71]

6.7. Vivo Fluorescence Imaging

It's called in vivo fluorescence imaging when fluorescently tagged molecules or cells are observed and monitored within the body. Frequently, it’s utilized in preclinical studies that concentrate on gene expression, drug delivery systems, and cancer progress. [

54,

55] "In-vivo fluorescence imaging" is a sophisticated diagnostic method that makes it possible to see and monitor biological processes in living things. It makes use of fluorescent probes or dyes, which light up when exposed to a particular frequency of light. In-vivo fluorescence imaging uses fluorescent labels or probes that cause the emission of fluorescing light in order to locate them inside cells, tissues, or organ systems and to observe their status and behavior. This is based on the principle of fluorescence, which states that a substance will emit light when excited by a specific wavelength. Important details regarding the fluorescent identifications' operation and function in bioluminescence are revealed by the spatial information the emitted light provides about their location, distribution, and dynamics.

The advantages of this method are Non-invasive With in-vivo fluorescence imaging it enables us to image biological processes without invasive methods such as surgery or collection of tissue samples from humans, Real-time imaging can be used to observe things such as moving medicines around the body, molecular signaling and cellular interactions carried out live-even before our eyes! It thus reveals important new insights into biological processes that we never knew existed; High sensitivity offers In vivo fluorescence imaging to image even where probe concentrations are very low enabling detection at low levels. This makes it possible to detect small targets or subtle alterations in an organism’s tissues, Specificity: The ability of fluorescent probes to bind to specific targets in a chosen manner enables the imaging of certain cells, tissues or molecules in a specific way and Multiplexing Imaging for multiple targets or molecular interactions within a single organism is achieved through the concurrent use of different fluorescent probes with varying emission wavelengths. [

72]

7. Fluorescent Probe Designing and Synthesis

One among the major domains in biological research is the synthesis and production of fluorescent probes. Detecting and visualizing a variety of analytes such as metal ions, reactive oxygen/nitrogen species, biothiols as well as dangerous gasses can be achieved using fluorescent probes, which are substances emitting light on exposure to light of specific wavelengths. [

73]

Fluorescent probes are basically designed to include two components: one is recognition or sensing unit which binds to an analyte of interest selectivity while the other is a fluorescent reporter. The detection unit is responsible for the probe’s sensitivity and selectivity towards the target whereas fluorescent reporter part takes care of light emission. Some typical organic fluorescent reporters are naphthalimides, coumarins and rhodamines. However, there are also other commonly used fluorescent reporters like metal complexes and quantum dots which are inorganic fluorophores. There are different mechanisms that can be used by the recognition unit to interact with the target analyte such as chelation, hydrogen bonding and covalent bond formation. Thus high specificity and sensitivity levels towards the target analyte are dependent on the recognition unit’s.[

73,

74] The creation of a fluorescent probe intended for a specific analyte must take into account the following factors Selectivity that means the probe must have minimal cross-reactivity with other species in the sample and high selectivity for the target analyte. A recognition unit that can attach to the target analyte is often incorporated, using methods such as chelation, hydrogen bonding or covalent bond formation as a means of achieving this, Sensitivity that means for probe detection, targeted analytes must have a lower concentration. This depends on the brightness which is a function of the fluorescent reporter groups’ molar extinction coefficient and quantum yield. The reason is that brighter probes allow for deeper penetration hence decreasing detection limits [

73], Photo-stability means for long-term imaging and quantification there must be use of a photo-bleaching resistant probe. The design of the probe and choice of fluorescent reporter group are determinants of photo stability [

73], Permeability of Cells and Solubility is also an important factor for biological uses, the investigation must be water-soluble and could penetrate cell membranes. The solubility and cell permeability of the probe can be tuned by including suitably chosen functional groups and linkers, Compatibility with biological systems means the non-toxic nature of the probes is required at doses employed for obtaining images from them in cells or tissues.[

74] The fluorescent reporter group choice as well as the design of a probe may potentially determine biocompatibility and Self-assembly simplicity should be easy and one ought to take only few simple steps for obtaining the probe from commercially available beginning ingredients. In this way, faster construction and improvement of recent probes becomes achievable. [

75]

Fluorescent probe manufacturing typically involves a few processes, such as preparing the fluorescent reporter group, the recognition unit, and the final probe molecule. For example, a naphthalimide-based fluorescent probe is made by following these procedures to detect Cu2+ ions. [

73] The synthesis of 6-Bromo-2-butyl-benzo [de]isoquinoline-1, 3-dione from N-butylamine and 4-bromo-1,8 naphthalic anhydride yields (A), Compound A reacts with hydrazine hydrate to produce 6-hydrazino-benzo [de]isoquinoline-1,3-diones (B). Complement B was coupled to a suitable recognition entity, such as the thiophene moiety, to produce the final fluorescent probe L. The selectivity of the above-synthesised probe L towards Cu2+ ions was examined using a variety of spectroscopic methods, including fluorescence spectroscopy and UV-visible absorption. Observing intracellular cupric ions in living cells is another use for it.

A new fluorescent probe called NA-LCX was logically created and synthesized in a recent work to detect hydrogen sulfide (H2S) in biological systems. This study addressed the requirement for sensitive and selective measuring techniques because H2S plays a crucial function as a signaling molecule. The design's foundation was a framework of diformylphenol and hydroxyl-naphthalene, which allowed for coordination with Cu^2+ ions and improved H2S detection's sensitivity and specificity.[

76] NMR and mass spectrometry confirmed that the NA-LCX ligand was produced by dissolving 3-hydroxy-2-naphthoyl hydrazide and 2, 6-diformyl-4-methylphenol in ethanol and then refluxing the mixture for six hours. The NA-LCX-Cu²⁺ complex was created when the ligand reacted with Cu (ClO₄)₂·6H₂O in methanol. When H2S was added, the complex showed a significant "on-off-on" fluorescence response, suggesting that the probe had successfully released Cu²⁺ ions and returned to its initial fluorescence. The efficacy of the probe was demonstrated by the determination of the detection limit for H2S at 2.79 μM. Furthermore, NA-LCX's promise for in vivo applications without significant cytotoxicity was confirmed by cell imaging investigations that showed it could detect both Cu2+ and H2S in human liver cancer cells (HepG-2). Overall, the study shows how to successfully apply rational design principles to create a fluorescent probe that greatly advances research in cellular biology and biochemistry, especially in figuring out how H2S functions in physiological processes.[

76]

8. Applications of Fluorescence Probes

8.1. Molecular Imaging and Cancer Detection

Molecular imaging relies heavily on fluorescence imaging; it is a key instrument in this context since it enables one to view without invasive methods what occurs inside animals’ bodies at the cellular level including even very small quantities of drugs. Thus, some notable aspects of molecular imaging using fluorescence are outlined below:

Fluorescent molecule imaging has been used extensively in biological medical applications as a non-destructive method of examining diseases, researching biological mechanisms, and studying drug actions. It is particularly useful for cancer detection probes, which have high specificity and sensitivity for detecting cancer in preclinical animals and aid in oncological surgeries. Improved tumor boundary identification can be achieved through advanced methods like structured illumination fluorescence imaging. [

79] Development of Probes is crucial for the specific imaging applications. Such probes that emit far-red to near infrared light are of great value because they are able to penetrate tissues deeply and have a high sensitivity. These probes have impressive fluorescence enhancements and low detection limits, thus they immediately respond to specific targets, like HOCl. [

80], Clinicians now have access to real-time imaging through fluorescence imaging, which is increasingly being adopted in clinical settings. Advanced adaptive methods and visualization techniques are making fluorescence imaging more precise and robust in the clinics. [

81], Surgical Guidance that provides real-time feedback to surgeons, an intraoperative fluorescence molecular imaging improves endoscopic and surgical imaging. Fast imaging techniques such as optical flow correction enhance sensitivity while reducing motion artifacts. [

82], Because of its excellent spatial resolution, real-time display, and capacity to profile many molecules, near-infrared imaging is very helpful in the identification of cancer. It corrects for the shortcomings of conventional techniques used for tumor identification, lymphatic imaging, in vivo cancer imaging, and surgical guidance. Fluorescence imaging methods, whose tumor-avid probes have a high degree of sensitivity and specificity towards malignancy identification, are used in preclinical models and oncological procedures. Fluorescence imaging techniques have made significant progress in the field of molecular imaging in the context of cancer detection and treatment. Strategies such as structured illumination fluorescence imaging, which enhances tumor boundary delineation and thereby improves tumor identification accuracy, are also mentioned. During surgery, a novel near-infrared (NIR) fluorescence probe designed for real-time tumor imaging was used in one well-known case study. With a technique that involves strong fluorescence upon attachment to cells expressing particular tumor markers, like folate receptors, this conjugated polymer-based probe demonstrated very selective targeting of cancer cells, According to the study, fluorescence imaging improves the accuracy of tumor removal by giving surgeons real-time feedback during surgical resections, which helps them better differentiate between cancerous and healthy tissue. This imaging modality's application in clinical trials involving patients with ovarian cancer resulted in a significant decrease in positive surgical margins; reported figures show a decrease from roughly 20% to less than 5%, highlighting its potential to improve surgical outcomes and lower cancer recurrence rates. Additionally, the studies showed that combination therapies using NIR probes and fluorescence-guided surgery not only improved visualization but also made it easier to identify micro-metastases that would otherwise go undetected, highlighting the crucial role fluorescence imaging will play in onco-surgery and customized cancer treatment plans in the future. [

83,

84]

8.2. Brain and Cardiovascular Imaging

Fluorescence imaging plays a critical role in cardiovascular and vascular imaging, along with enabling one to visualize the structures and workings of the brain. Some key points on how fluorescence imaging is being utilized in different fields include:

Brain Imaging: Fluorescence imaging techniques allow researchers to investigate cellular and molecular processes within the central nervous system (CNS). It is possible for them to track dynamic events occurring in the brain via custom-made optics or fluorescent tags. Neurotransmission, synaptic communication as well as molecular dynamics can be visualized using this imaging method providing valuable information on brain functioning and neurological diseases. [

82], Fluorescence imaging provides a means of visualizing the cerebral vasculature without requiring invasive surgeries such as craniotomies. By utilizing particular agents’ innate near-infrared photoluminescence, fluorescence imaging allows fine monitoring of blood vessels by penetrating deep into brain tissues. This non-invasive method makes it possible to track and analyse vascular changes and adjustments in real time, which is crucial for comprehending illnesses like strokes. Additionally, it makes it possible to evaluate irregularities in blood flow and blood perfusion [

86] and near-infrared fluorescence imaging, particularly in the second near-infrared spectral band (NIR-II), provides great spatial resolution and deep tissue penetration for cardiovascular imaging. Because it uses FDA-approved materials like indocyanine green (ICG), this imaging technique is perfect for use in clinical cardiovascular imaging. Cerebrovascular disease could be diagnosed and treated using macro-imaging and micro-angiography. Deep monitoring of the cerebral vasculature is made possible by NIR-II fluorescence imaging, which enables the detection of any abnormalities or modifications in vascular structure. [

87]

Both brain and cardiovascular studies have benefited greatly from fluorescence imaging, which has improved our comprehension of biological processes and disease mechanisms. In one prominent example study, neuronal activity was tracked in vivo using genetically encoded calcium indicators (GECIs) in brain imaging. By using sophisticated two-photon imaging techniques, scientists were able to see calcium dynamics in real time throughout several different parts of the living mouse brain. Neural activity during sensory stimulation and behavioural activities could be tracked thanks to the use of the GCaMP family of indicators, where calcium ion binding produced a detectable increase in fluorescence. This method enabled previously unheard-of insights into the intricate dynamics involved in learning and memory processes by exposing how brain circuits process information.[

88]

Similar to this, a groundbreaking study in cardiovascular imaging created a fluorescent cardiac imaging system that uses indocyanine green (ICG) to measure blood flow in real time during surgery. High-resolution intraoperative imaging made possible by this innovative technique allowed surgeons to accurately observe and measure coronary artery blood flow. In order to maximize the signal from ICG, the implementation required carefully planned optical setups furnished with LED light sources and appropriate filters. The system's remarkable correlation values of 0.9938 for blood flow data in preclinical studies confirmed its effectiveness in detecting myocardial perfusion problems during coronary artery bypass graft procedures. The surgical decision-making process is greatly improved by this technology, which eventually leads to better patient outcomes.[

89].

Table 1.

An Overview of the Uses of Fluorescence Molecular Imaging in Medical Research and Diagnostics.

Table 1.

An Overview of the Uses of Fluorescence Molecular Imaging in Medical Research and Diagnostics.

| Application |

Description |

| Fluorescence molecular imaging |

A non-invasive technique for tracking illnesses, researching biological processes, and learning about how drugs work. |

| Cancer identification |

Improves tumor border delineation with sophisticated imaging techniques; uses tumor-avid probes for high specificity and sensitivity in detecting malignancies. |

| Development of probes |

The development of fluorescent probes that glow in the far-red to near-infrared spectrum and are sensitive to specific targets like HOCl has allowed for deep tissue penetration and high sensitivity. |

| Real-time Imaging |

With the use of visualization techniques and adaptive procedures to improve accuracy, fluorescence imaging is being used in clinical settings more and more. |

| Surgical Guidance |

Increases endoscopic and surgical imaging by continuously providing feedback during the procedure; motion artifacts are minimized by using methods such optical flow correction. |

| Near–infrared imaging |

Provides superior real-time display and spatial resolution for cancer diagnosis, making up for the drawbacks of conventional imaging modalities in a range of applications. |

| Brain imaging |

Enables the cellular and molecular analysis of brain activity; using specialized optics and fluorescent markers to examine neurotransmission and synaptic communication. |

| Vascular Imaging |

Non-invasive cerebral vasculature observation is vital to comprehending disorders such as stroke since it tracks anomalies in blood vessels in real time. |

| Cardiovascular imaging |

To assess vascular anatomy and detect cerebrovascular diseases, employ near-infrared fluorescence imaging, which offers deep tissue penetration and great spatial resolution.. |

Table 2.

Benefits and difficulties of fluorescent probe optical imaging.

Table 2.

Benefits and difficulties of fluorescent probe optical imaging.

| Benefits |

Difficulties |

| Real-time imaging: Fluorescent probes make it possible to see physiological conditions and real-time cellular operations.[93] |

Background signals: Fluorescence signals resulting from natural cofactors within living cells might provide a problem for imaging research.[94] |

| High sensitivity: The detection of particular biomolecules is made possible by the high sensitivity and specificity of fluorescent probes.[94] |

Elevated background signals: They can diminish signal contrast in intact tissue and multi-cell systems.[94] |

| Non-invasive Imaging: Highly precise non-invasive imaging of cellular events is made possible by tiny fluorophores.[93] |

Challenges with in vivo cancer imaging: Creating fluorescent nanoparticle probes presents difficulties. |

| Increased functionality: Optimal optical characteristics for certain subcellular locations are provided by small-molecule fluorescent probes. |

Complex photo physical schemes: The complex photo physical schemes of certain fluorescent probes influence their bio-analytical responses. |

| Targeted therapy: Fluorescent probes can help medications be delivered in a specific manner in targeted therapy. |

Inadequate signal-to-background ratios hinder the clinical application of optical molecular imaging. |

Difficulties with Tissue Auto-Fluorescence and Depth Penetration

Autofluorescence: Tissue auto-fluorescence interferes with signal detection in fluorescence imaging, lowering the signal-to-background ratio. A purified diet, longer excitation/emission wavelengths, and NIR-II imaging are among methods that can be employed to solve this issue [

73]., Depth Penetration: The significant light scattering and autofluorescence that occur between 650 and 900 nm limit the ability to image deep tissues using conventional optical techniques. With documented depths through tissue at roughly 3.2 cm, NIR-II imaging (1000–1700 nm) offers superior depth penetration in response to such limitations. [

95,

96]

8.3. Clinical Translation

Optical imaging in biomedical applications has become highly effective with fluorescent probes, enabling real-time viewing of cellular activities and ultimately facilitating improved disease detection and therapy, particularly for cancers. Key consideration for clinical translation is designing fluorescent probes, it is important to consider clinical translation. To achieve successful in vivo performance, several key factors must be taken into account, including stability specificity, clearance characteristics and effective urine excretion, Compared to NIR-II (1000-1700 nm) probes which exhibit superior intravital performance due to lower tissue autofluorescence, better signal-to-noise ratios and deeper penetration depths; those emitting light in the visible and near-infrared (NIR)-I range (700-900 nm) have undergone clinical trials and There are several Biomedical applications for fluorescent probes such as drug delivery, biological imaging, medical diagnosis and therapy among others. In vivo imaging at high performance has been demonstrated by NIR-II organic small molecule probes having emission maxima more than 1200 nm. [

97]

Few fluorescent probes have received approval for use in medical imaging, despite their potential. This presents challenges, including limited clinical acceptability. The intricacy of constructing probes, regulatory obstacles, and the requirement for thorough validation in clinical settings are the causes of the delay. [

97].

FTS (fluorescence-traced surgery) [

98] this represents one of the primary uses for fluorescent probes. Now that they can see tumors in real time, surgeons may more accurately remove them, reducing the amount of damage to nearby healthy tissues [

99]. & Regulatory Obstacles: Fluorescence probes must pass comprehensive preclinical and clinical testing in order to be authorized.

An important advancement in the therapeutic use of fluorescence imaging is the use of indocyanine green (ICG) in fluorescence-guided surgery (FGS) for various cancer types.[

100] In a groundbreaking clinical investigation, researchers investigated the potential of intraoperative near-infrared fluorescence imaging to enhance visibility during lymph node dissection in patients with breast cancer and melanoma. The study found that when compared to traditional approaches, ICG administration significantly increased detection rates by enabling the real-time identification of sentinel lymph nodes. Specifically, ICG fluorescence aided in determining the exact position of lymphatic channels, allowing for successful sentinel lymph node mapping in 95% of participants, which is a significant improvement over the usual 75% attained with conventional methods. The clinical results also showed that the incorporation of fluorescence imaging reduced surgical problems and enhanced oncological results in addition to improving the surgical procedure's technical success. This case study demonstrates how fluorescence imaging technologies, especially ICG, can revolutionize surgical practice by increasing the precision of cancer detection and treatment, which will encourage a wider use of fluorescence-based methods in clinical oncology. [

101,

102]

Conclusion

The discovery of fluorescent probes and other improvements in optical imaging are driving a revolution in medical diagnoses and treatment. The ability to see complex biological processes and anomalies within the body is improved by these cutting-edge imaging techniques, which offer a safer, non-invasive substitute for conventional ionizing radiation treatments. Patient outcomes are greatly enhanced by early disease detection and ongoing disease monitoring made possible by optical imaging's high resolution. Additionally, the development of optical contrast agents has made targeted molecular imaging possible while enhancing surgical precision and deepening our understanding of disease dynamics.

Research that focuses on improving the efficiency of fluorescent probes in optical imaging methods must continue to be funded since we are at the nexus of technology advancement and therapeutic applicability. Realizing the full potential of optical imaging via fluorescent probes in standard healthcare settings will require bridging the gap between laboratory discoveries and clinical practices. However, this approach will not only provide unique platform for better diagnosis and treatments to completely transform patient care but can also provide opportunity for scientists in different fields to work inclusively towards development and new understandings of molecular imaging. Nevertheless, with the development of highly efficient, and ecofriendly fluorescent probes as its top priorities, optical imaging could be poised for a bright future in customized medicine.

References

- Licha, K. (2002). Contrast Agents for Optical Imaging. In: Krause, W. (eds) Contrast Agents II. Topics in Current Chemistry, vol 222. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. [CrossRef]

- https://www.nibib.nih.gov/science-education/science-topics/optical-imaging.

- Bremer, C., Ntziachristos, V. & Weissleder, R. Optical-based molecular imaging: contrast agents and potential medical applications. Eur Radiol 13, 231–243 (2003). [CrossRef]

- https://www.msdmanuals.com/en-in/professional/gastrointestinal-disorders/diagnostic-and-therapeutic-gastrointestinal-procedures/endoscopy.

- https://www.healthline.com/health/endoscopy.

- https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/153737.

- Wu, Y., , Zeng, F., , Zhao, Y., , & Wu, S., (2021). Emerging contrast agents for multispectral optoacoustic imaging and their biomedical applications. Chemical Society reviews, 50(14), 7924–7940. [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, J. P., Gupta, P. K., Farsiu, S., Maldonado, R., Kim, T., Toth, C. A., & Mruthyunjaya, P. (2010). Evaluation of contrast agents for enhanced visualization in optical coherence tomography. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science, 51(12), 6614–6619. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V. P., Hu, J., Zhe, J., Ramasamy, S., Ahmed, U., & Paulus, Y. M. (2024). Advanced nanomaterials for imaging of eye diseases. ADMET & DMPK, 12(2), 269–298. [CrossRef]

- Cho, N., & Shokeen, M. (2019). Changing landscape of optical imaging in skeletal metastases. Journal of bone oncology, 17, 100249. [CrossRef]

- Nioka, S., & Chen, Y. (2011). Optical tecnology developments in biomedicine: history, current and future. Translational medicine @ UniSa, 1, 51–150.

- Hadjipanayis, C. G., Jiang, H., Roberts, D. W., & Yang, L. (2011). Current and future clinical applications for optical imaging of cancer: from intraoperative surgical guidance to cancer screening. Seminars in oncology, 38(1), 109–118. [CrossRef]

- Hintz, S. R., Cheong, W. F., van Houten, J. P., Stevenson, D. K., & Benaron, D. A. (1999). Bedside imaging of intracranial hemorrhage in the neonate using light: comparison with ultrasound, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging. Pediatric research, 45(1), 54–59. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., Zhu, W., Zhang, Y., Chen, S., & Yang, D. (2021). Harnessing the Power of Hybrid Light Propagation Model for Three-Dimensional Optical Imaging in Cancer Detection. Frontiers in oncology, 11, 750764. [CrossRef]

- Moriyama, E. H., Zheng, G., & Wilson, B. C. (2008). Optical molecular imaging: from single cell to patient. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics, 84(2), 267–271. [CrossRef]

- Kaller, M. O., & An, J. (2023). Contrast Agent Toxicity. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

- https://www.msdmanuals.com/home/special-subjects/common-imaging-tests/angiography.

- Chen Y. (2022). Recent Advances in Excimer-Based Fluorescence Probes for Biological Applications. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland), 27(23), 8628. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H., Fan, J., Du, J., & Peng, X. (2016). Fluorescent Probes for Sensing and Imaging within Specific Cellular Organelles. Accounts of chemical research, 49(10), 2115–2126. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., Liu, J., Wang, X., Mi, F., Wang, D., & Wu, C. (2020). Fluorescent Bioconjugates for Super-Resolution Optical Nanoscopy. Bioconjugate chemistry, 31(8), 1857–1872. [CrossRef]

- Dean, K. M., & Palmer, A. E. (2014). Advances in fluorescence labeling strategies for dynamic cellular imaging. Nature chemical biology, 10(7), 512–523. [CrossRef]

- Pirovano, G., Roberts, S., Kossatz, S., & Reiner, T. (2020). Optical Imaging Modalities: Principles and Applications in Preclinical Research and Clinical Settings. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine, 61(10), 1419–1427. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D., & Xia, J. (2019). Optics based biomedical imaging: Principles and applications. Journal of Applied Physics.

- Lin, L., Jiang, P., Bao, Z., Pang, W., Ding, S., Yin, M. J., Li, P., & Gu, B. (2021). Fundamentals of Optical Imaging. Advances in experimental medicine and biology, 3233, 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Han, S., Lee, D., Kim, S., Kim, H. H., Jeong, S., & Kim, J. (2022). Contrast Agents for Photoacoustic Imaging: A Review Focusing on the Wavelength Range. Biosensors, 12(8), 594. [CrossRef]

- Hadzima, M., Faucher, F. F., Blažková, K., Yim, J. J., Guerra, M., Chen, S., Woods, E. C., Park, K. W., Šácha, P., Šubr, V., Kostka, L., Etrych, T., Majer, P., Konvalinka, J., & Bogyo, M. (2024). Polymer-Tethered Quenched Fluorescent Probes for Enhanced Imaging of Tumor-Associated Proteases. ACS sensors, 9(7), 3720–3729. [CrossRef]

- Park, J. H., , Dumani, D. S., , Arsiwala, A., , Emelianov, S., , & Kane, R. S., (2018). Tunable aggregation of gold-silica janus nanoparticles to enable contrast-enhanced multiwavelength photoacoustic imaging in vivo. Nanoscale, 10(32), 15365–15370. [CrossRef]

- Miao, Q., & Pu, K. (2018). Organic Semiconducting Agents for Deep-Tissue Molecular Imaging: Second Near-Infrared Fluorescence, Self-Luminescence, and Photoacoustics. Advanced materials (Deerfield Beach, Fla.), 30(49), e1801778. [CrossRef]

- Gottschalk, H. M., Wecker, T., Khattab, M. H., Fischer, C. V., Callizo, J., Rehfeldt, F., Lubjuhn, R., Russmann, C., Hoerauf, H., & van Oterendorp, C. (2019). Lipid Emulsion-Based OCT Angiography for Ex Vivo Imaging of the Aqueous Outflow Tract. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science, 60(1), 397–406. [CrossRef]

- Hui, X., Malik, M. O. A., & Pramanik, M. (2022). Looking deep inside tissue with photoacoustic molecular probes: a review. Journal of biomedical optics, 27(7), 070901. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V. P., Qian, W., Wang, X., & Paulus, Y. M. (2021). Functionalized contrast agents for multimodality photoacoustic microscopy, optical coherence tomography, and fluorescence microscopy molecular retinal imaging. Methods in enzymology, 657, 443–480. [CrossRef]

- Lemaster, J. E., & Jokerst, J. V. (2017). What is new in nanoparticle-based photoacoustic imaging?. Wiley interdisciplinary reviews. Nanomedicine and nanobiotechnology, 9(1), 10.1002/wnan.1404. [CrossRef]

- Contrast Agents Market Size by Segments, Share, Regulatory, Reimbursement and Forecast to 2033. (2024). Market Research Reports & Consulting | GlobalData UK Ltd. https://www.globaldata.com/store/report/contrast-agents-devices-market-analysis/.

- Contrast Media Market Size, Share & Growth Report, 2030. (2024). grandviewresearch.com. https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/contrast-media-contrast-agents-market.

- https://www.fnfresearch.com/news/global-mri-contrast-media-agents-market.

- Lee, J. H., Park, G., Hong, G. H., Choi, J., & Choi, H. S. (2012). Design considerations for targeted optical contrast agents. Quantitative imaging in medicine and surgery, 2(4), 266–273. [CrossRef]

- Nakata, E., Gerelbaatar, K., Komatsubara, F., & Morii, T. (2022). Stimuli-Responsible SNARF Derivatives as a Latent Ratiometric Fluorescent Probe. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland), 27(21), 7181. [CrossRef]

- Guo, L., Liu, F., Cai, C., Liu, J., & Zhang, G. (2019). 3D deep encoder-decoder network for fluorescence molecular tomography. Optics letters, 44(8), 1892–1895. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L., Zhang, L., Zhou, M., & Alifu, N. (2021). Sheng wu gong cheng xue bao = Chinese journal of biotechnology, 37(8), 2678–2687. [CrossRef]

- Boutorine, A. S., Novopashina, D. S., Krasheninina, O. A., Nozeret, K., & Venyaminova, A. G. (2013). Fluorescent probes for nucleic Acid visualization in fixed and live cells. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland), 18(12), 15357–15397. [CrossRef]

- Chen, G., Li, C., Zhang, Y., & Wang, Q. (2021). Whole-Body Fluorescence Imaging in the Near-Infrared Window. Advances in experimental medicine and biology, 3233, 83–108. [CrossRef]

- Heeman, W., Vonk, J., Ntziachristos, V., Pogue, B. W., Dierckx, R. A. J. O., Kruijff, S., & van Dam, G. M. (2022). A Guideline for Clinicians Performing Clinical Studies with Fluorescence Imaging. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine, 63(5), 640–645. [CrossRef]

- Si, K., Fiolka, R., & Cui, M. (2012). Fluorescence imaging beyond the ballistic regime by ultrasound pulse guided digital phase conjugation. Nature photonics, 6(10), 657–661. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, J. Q. M., McWade, M., Thomas, G., Beddard, B. T., Herington, J. L., Paria, B. C., Schwartz, H. S., Halpern, J. L., Holt, G. E., & Mahadevan-Jansen, A. (2018). Development of a modular fluorescence overlay tissue imaging system for wide-field intraoperative surgical guidance. Journal of medical imaging (Bellingham, Wash.), 5(2), 021220. [CrossRef]

- Prakriti Karki. (2024). Fluorescence Microscope: Principle, Parts, Uses, Examples. Microbe Notes. https://microbenotes.com/fluorescence-microscope-principle-instrumentation-applications-advantages-limitations/.

- Mubaid, F., Kaufman, D., Wee, T. L., Nguyen-Huu, D. S., Young, D., Anghelopoulou, M., & Brown, C. M. (2019). Fluorescence microscope light source stability. Histochemistry and cell biology, 151(4), 357–366. [CrossRef]

- Fluorescence Microscopy - Anatomy of the Fluorescence Microscope | Olympus LS. (2024). olympus-lifescience.com. https://www.olympus-lifescience.com/de/microscope-resource/primer/techniques/fluorescence/anatomy/fluoromicroanatomy/.

- Fluorescence Microscopy - Explanation and Labelled Images. (2024). New York Microscope Company. https://microscopeinternational.com/fluorescence-microscopy/.

- Introduction to Fluorescence Microscopy. (2024). Nikon’s MicroscopyU. https://www.microscopyu.com/techniques/fluorescence/introduction-to-fluorescence-microscopy.

- Agard, D. A., Hiraoka, Y., & Sedat, J. W. (1988). Three-dimensional light microscopy of diploid Drosophila chromosomes. Cell motility and the cytoskeleton, 10(1-2), 18–27. [CrossRef]

- Park, S., Zhang, J., Reyer, M. A., Zareba, J., Troy, A. A., & Fei, J. (2018). Conducting Multiple Imaging Modes with One Fluorescence Microscope. Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE, (140), 58320. [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa-Ankerhold, H. C., Ankerhold, R., & Drummen, G. P. (2012). Advanced fluorescence microscopy techniques--FRAP, FLIP, FLAP, FRET and FLIM. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland), 17(4), 4047–4132. [CrossRef]

- Schäferling M. (2012). The art of fluorescence imaging with chemical sensors. Angewandte Chemie (International ed. in English), 51(15), 3532–3554. [CrossRef]

- Emptage N. J. (2001). Fluorescent imaging in living systems. Current opinion in pharmacology, 1(5), 521–525. [CrossRef]

- Ntziachristos, V., Turner, G., Dunham, J., Windsor, S., Soubret, A., Ripoll, J., & Shih, H. A. (2005). Planar fluorescence imaging using normalized data. Journal of biomedical optics, 10(6), 064007. [CrossRef]

- van der Valk, M. J. M., Handgraaf, H. J. M., Sibinga-Mulder, B. G., Hilling, D. E., van Dam, G. M., & Vahrmeijer, A. L. (2018). Intraoperatieve beeldvorming met fluorescentie, 5 jaar later [Intraoperative imaging using fluorescence, 5 years later]. Nederlands tijdschrift voor geneeskunde, 162, D2067.

- Li, C., Gao, L., Liu, Y., & Wang, L. V. (2013). Optical sectioning by wide-field photobleaching imprinting microscopy. Applied physics letters, 103(18), 183703. [CrossRef]

- Forsgren, E., Edlund, C., Oliver, M., Barnes, K., Sjögren, R., & Jackson, T. R. (2022). High-throughput widefield fluorescence imaging of 3D samples using deep learning for 2D projection image restoration. PloS one, 17(5), e0264241. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D., Zang, Z., Wang, Q., Jiao, Z., Rocca, F. M. D., Chen, Y., & Li, D. D. U. (2022). Smart Wide-field Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging System with CMOS Single-photon Avalanche Diode Arrays. Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. Annual International Conference, 2022, 1887–1890. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D., Zang, Z., Wang, Q., Jiao, Z., Rocca, F. M. D., Chen, Y., & Li, D. D. U. (2022). Smart Wide-field Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging System with CMOS Single-photon Avalanche Diode Arrays. Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. Annual International Conference, 2022, 1887–1890. [CrossRef]

- Crowe, S. E., & Ellis-Davies, G. C. (2014). Longitudinal in vivo two-photon fluorescence imaging. The Journal of comparative neurology, 522(8), 1708–1727. [CrossRef]

- Wolenski, J. S., & Julich, D. (2014). Fluorescence microscopy gets faster and clearer: roles of photochemistry and selective illumination. The Yale journal of biology and medicine, 87(1), 21–32.

- Pacheco, S., Wang, C., Chawla, M. K., Nguyen, M., Baggett, B. K., Utzinger, U., Barnes, C. A., & Liang, R. (2017). High resolution, high speed, long working distance, large field of view confocal fluorescence microscope. Scientific reports, 7(1), 13349. [CrossRef]

- Botchway, S. W., Scherer, K. M., Hook, S., Stubbs, C. D., Weston, E., Bisby, R. H., & Parker, A. W. (2015). A series of flexible design adaptations to the Nikon E-C1 and E-C2 confocal microscope systems for UV, multiphoton and FLIM imaging. Journal of microscopy, 258(1), 68–78. [CrossRef]

- Yan, W., Peng, X., Qi, J., Gao, J., Fan, S., Wang, Q., Qu, J., & Niu, H. (2014). Dynamic fluorescence lifetime imaging based on acousto-optic deflectors. Journal of biomedical optics, 19(11), 116004. [CrossRef]

- Datta, R., Heaster, T. M., Sharick, J. T., Gillette, A. A., & Skala, M. C. (2020). Fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy: fundamentals and advances in instrumentation, analysis, and applications. Journal of biomedical optics, 25(7), 1–43. [CrossRef]

- Stanisavljevic, M., Krizkova, S., Vaculovicova, M., Kizek, R., & Adam, V. (2015). Quantum dots-fluorescence resonance energy transfer-based nanosensors and their application. Biosensors & bioelectronics, 74, 562–574. [CrossRef]

- Balconi, M., & Crivelli, D. (2010). Veridical and false feedback sensitivity and punishment-reward system (BIS/BAS): ERP amplitude and theta frequency band analysis. Clinical neurophysiology : official journal of the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology, 121(9), 1502–1510. [CrossRef]

- https://www.gu.se/en/core-facilities/fluorescence-resonance-energy-transfer.

- Kumar, N., Bhalla, V., & Kumar, M. (2014). Resonance energy transfer-based fluorescent probes for Hg2+, Cu2+ and Fe2+/Fe3+ ions. The Analyst, 139(3), 543–558. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F. Y., Mei, L. J., Tian, R., Li, C., Wang, Y. L., Xiang, S. L., Zhu, M. Q., & Tang, B. Z. (2024). Recent advances in super-resolution optical imaging based on aggregation-induced emission. Chemical Society reviews, 53(7), 3350–3383. [CrossRef]

- Hugelier, S., Colosi, P. L., & Lakadamyali, M. (2023). Quantitative Single-Molecule Localization Microscopy. Annual review of biophysics, 52, 139–160. [CrossRef]

- Yu, J., Jiang, G., & Wang, J. (2023). In Vivo Fluorescence Imaging-Guided Development of Near-Infrared AIEgens. Chemistry, an Asian journal, 18(5), e202201251. [CrossRef]

- Yu, M., Ward, M. B., Franke, A., Ambrose, S. L., Whaley, Z. L., Bradford, T. M., Gorden, J. D., Beyers, R. J., Cattley, R. C., Ivanović-Burmazović, I., Schwartz, D. D., & Goldsmith, C. R. (2017). Adding a Second Quinol to a Redox-Responsive MRI Contrast Agent Improves Its Relaxivity Response to H2O2. Inorganic chemistry, 56(5), 2812–2826. [CrossRef]

- He, G., Liu, C., Liu, X., Wang, Q., Fan, A., Wang, S., & Qian, X. (2017). Design and synthesis of a fluorescent probe based on naphthalene anhydride and its detection of copper ions. PloS one, 12(10), e0186994. [CrossRef]

- Mao, G., Liu, C., Yang, N., Yang, L., & He, G. (2021). Design and Synthesis of a Fluorescent Probe Based on Copper Complex for Selective Detection of Hydrogen Sulfide. Journal of Sensors. [CrossRef]

- Li, L., Wang, J., Xu, S., Li, C., & Dong, B. (2022). Recent Progress in Fluorescent Probes For Metal Ion Detection. Frontiers in Chemistry. [CrossRef]

- Jacoby-Morris, K., & Patterson, G. H. (2021). Choosing Fluorescent Probes and Labeling Systems. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, N.J.), 2304, 37–64. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, H., Ogawa, M., Alford, R., Choyke, P. L., & Urano, Y. (2010). New strategies for fluorescent probe design in medical diagnostic imaging. Chemical reviews, 110(5), 2620–2640. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J., Miller, J. P., Hathi, D., Zhou, H., Achilefu, S., Shokeen, M., & Akers, W. J. (2016). Enhancing in vivo tumor boundary delineation with structured illumination fluorescence molecular imaging and spatial gradient mapping. Journal of biomedical optics, 21(8), 80502. [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, V., Thirumalaivasan, N., Wu, S. P., & Sivan, V. (2019). A far-red to NIR emitting ultra-sensitive probe for the detection of endogenous HOCl in zebrafish and the RAW 264.7 cell line. Organic & biomolecular chemistry, 17(14), 3538–3544. [CrossRef]

- Glatz, J., Symvoulidis, P., Garcia-Allende, P. B., & Ntziachristos, V. (2014). Robust overlay schemes for the fusion of fluorescence and color channels in biological imaging. Journal of biomedical optics, 19(4), 040501. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H., Xu, H., Peng, B., Huang, X., Hu, Y., Zheng, C., & Zhang, Z. (2024). Illuminating the future of precision cancer surgery with fluorescence imaging and artificial intelligence convergence. Npj Precision Oncology. [CrossRef]

- Malik, M. M. U. D., Alqahtani, M. M., Hadadi, I., Kanbayti, I., Alawaji, Z., & Aloufi, B. A. (2024). Molecular Imaging Biomarkers for Early Cancer Detection: A Systematic Review of Emerging Technologies and Clinical Applications. Diagnostics. [CrossRef]

- Schouw, H. M., Huisman, L. A., Janssen, Y. F., Slart, R. H. J. A., Borra, R. J. H., Willemsen, A. T. M., Brouwers, A. H., van Dijl, J. M., Dierckx, R. A., van Dam, G. M., Szymanski, W., Boersma, H. H., & Kruijff, S. (2021). Targeted optical fluorescence imaging: a meta-narrative review and future perspectives. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. [CrossRef]

- Okubo Y. (2022). Investigation of Brain Functions with Fluorescence Imaging Techniques. Juntendo Iji zasshi = Juntendo medical journal, 68(2), 157–162. [CrossRef]

- Hong, G., Diao, S., Chang, J., Antaris, A. L., Chen, C., Zhang, B., Zhao, S., Atochin, D. N., Huang, P. L., Andreasson, K. I., Kuo, C. J., & Dai, H. (2014). Through-skull fluorescence imaging of the brain in a new near-infrared window. Nature photonics, 8(9), 723–730. [CrossRef]

- Kim, T. H., & Schnitzer, M. J. (2022). Fluorescence imaging of large-scale neural ensemble dynamics. Cell. [CrossRef]

- Mashalchi, S., Pahlavan, S., & Hejazi, M. (2021). A novel fluorescent cardiac imaging system for preclinical intraoperative angiography. BMC Medical Imaging. [CrossRef]

- Sosnovik, D. E., Nahrendorf, M., & Weissleder, R. (2008). Targeted imaging of myocardial damage. Nature Clinical Practice Cardiovascular Medicine. [CrossRef]

- Duprée, A., Rieß, H., Detter, C., Debus, E. S., & Wipper, S. H. (2018). Utilization of indocynanine green fluorescent imaging (ICG-FI) for the assessment of microperfusion in vascular medicine. Innovative Surgical Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Che, F., Zhao, X., Wang, X., Li, P., & Tang, B. (2023). Fluorescent Imaging Agents for Brain Diseases. Targets. [CrossRef]

- Yu, X., Feng, Z., Cai, Z., Jiang, M., Xue, D., Zhu, L., Zhang, Y., Liu, J., Que, B., Yang, W., Xi, W., Zhang, D., Qian, J., & Li, G. (2019). Deciphering of cerebrovasculatures via ICG-assisted NIR-II fluorescence microscopy. Journal of materials chemistry. B, 7(42), 6623–6629. [CrossRef]

- de Moliner, F., Nadal-Bufi, F., & Vendrell, M. (2024). Recent advances in minimal fluorescent probes for optical imaging. Current opinion in chemical biology, 80, 102458. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J., & Pu, K. (2020). Activatable Molecular Probes for Second Near-Infrared Fluorescence, Chemiluminescence, and Photoacoustic Imaging. Angewandte Chemie (International ed. in English), 59(29), 11717–11731. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y., Zhong, X., & Dennis, A. M. (2023). Minimizing near-infrared autofluorescence in preclinical imaging with diet and wavelength selection. Journal of biomedical optics, 28(9), 094805. [CrossRef]

- Dang, X., Bardhan, N. M., Qi, J., Gu, L., Eze, N. A., Lin, C. W., Kataria, S., Hammond, P. T., & Belcher, A. M. (2019). Deep-tissue optical imaging of near cellular-sized features. Scientific reports, 9(1), 3873. [CrossRef]

- Seah, D., Cheng, Z., & Vendrell, M. (2023). Fluorescent Probes for Imaging in Humans: Where Are We Now?. ACS nano, 17(20), 19478–19490. [CrossRef]

- Taruttis, A., & Ntziachristos, V. (2012). Translational optical imaging. AJR. American journal of roentgenology, 199(2), 263–271. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L., Gan, Y., Wu, Y., Xue, D., Hu, J., Zhang, Y., Liu, Y., Ma, S., Zhou, J., Luo, G., Peng, D., & Qian, W. (2023). Indocyanine Green Fluorescence Imaging in the Surgical Management of Skin Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Clinical, cosmetic and investigational dermatology, 16, 3309–3320. [CrossRef]