1. Introduction

Hydrogen Internal Combustion Engines (HICE) were initially created in 1820 by Reverend W. Cecil, who introduced an automatic engine utilizing a hydrogen-air mixture with a vacuum mechanism. Hydrogen has never been commercially viable because of its restricted output power, minimal ignition energy demand, short flashing distance, high autoignition temperature, rapid flame speed, significant diffusivity, poor density, and higher adiabatic flame temperature The stoichiometric combustion of hydrogen entails the reaction of 2H₂ + O₂, together with the requisite mass and volume of air(Karim, 2003). The compression ratio and temperature increase (autoignition threshold) are essential for hydrogen-fueled compression ignition engines. Pré-ignition poses a significant issue in hydrogen engines owing to its minimal ignition energy, broad flammability range, and limited quenching distance. Sources of hot spots encompass spark plugs, exhaust valves, deposits, and the pyrolysis of oil within the combustion chamber(Wróbel et al., 2022).

Central injection is the most basic method for reducing the hydrogen engine compression ratio, but it’s linked to pre-ignition and backfire issues(Dimitriou, 2023). Port injection reduces this risk, while direct injection introduces hydrogen gas post-intake valve closure, reducing backfire risks and enhancing output by over 20%. Direct injection also has disadvantages like inadequate mixing and elevated NOx emissions. Hydrogen-powered spark ignition engines (SI engines) can reduce carbon emissions in heavy-duty sectors by integrating advanced fuel injection techniques and regulating combustion temperatures. Solutions include cold-rated and non-platinized spark plugs, injection phasing, oil management, and lean combustion and exhaust gas recirculation techniques. BorgWarner’s Direct Injection Injector offers CO2-free mobility and low ownership costs. These engines are increasingly used in off-road and non-road mobile machinery, heavy-duty trucking, and long-haul transport due to their superior thermal management, durability, and efficiency.

Compression ignition engines, developed by Rudolf Diesel, are known for their fuel efficiency and high compression ratios. However, hydrogen engines face challenges like low ignition energy, high ignition temperature, and rapid combustion. Strategies include increased intake air temperatures, improved compression ratios, and hybrid methodologies. Hydrogen faces energy density issues, impacting sectors like automotive and aerospace. Various methods require modifications to hydrogen compression ignition design.

Hydrogen injection in engines can enhance ventilation and reduce the risk of backfire and pre-ignition. Manifold injection, Continuous Manifold Injection (CMI) and Timed Manifold Injection (TMI) are used for better control. Direct injection eliminates hydrogen from the intake manifold, but it incurs costs due to its increased diffusivity and reduced lubricity. The study explores hydrogen-diesel engines and their hydrogen substitution rates. The auto-ignition temperature of hydrogen is 858 K, making traditional diesel engines impractical. The study categorizes hydrogen fuel usage into minimal, medium, and high substitution rates. Direct hydrogen injection improves fuel economy and emissions, but there is a 14% volumetric efficiency deficit. Biofuels offer potential solutions for aviation, maritime, and heavy-duty vehicles, but are not feasible for short-term applications due to food production competition. Hydrogen-biofuel dual-fuel engines can convert biofuel usage while maintaining production continuity.

Hydrogen compression ignition (CI) engines have been built over time to attain steady combustion. The intrinsic characteristics of hydrogen render ignition difficult, resulting in misfires and explosions. (Ikegami et al., 1980) Documented favorable results with a CR of 18.6; nonetheless, evidence indicates that the sole application of pure compressive force is inadequate. (Ikegami et al., 1982) They proposed injecting minimal pilot fuel to improve firm stability, resulting in ‘silent burning’ due to preceding cycles. (Rosati & Aleiferis, 2009) This method enhanced NOx emissions and heightened energy demands by employing ultra-lean hydrogen-air mixtures at high intake temperatures. (Lee et al., 2013)asserted that attaining hydrogen compression ignition is achievable under extreme conditions with elevated compression ratios; nevertheless, the operational range is constrained, and there exists a risk of knocking and backfiring.(Homan et al., 1979) accomplished hydrogen compression ignition via a glow plug, mitigating knocking and yielding more effective pressure than diesel fuel. Nonetheless, continuous utilization of the glow plug resulted in diminished efficiency owing to thermal requirements, underscoring the necessity to balance elements such as efficiency and stability. Achieving dependable hydrogen combustion ignition is intricate, necessitating approaches like temperature management, mixture composition manipulation, and supplementary ignition methods.

Table 1.

Key Research on Compression Ignition (CI) Functionality Utilizing Hydrogen Fuel.

Table 1.

Key Research on Compression Ignition (CI) Functionality Utilizing Hydrogen Fuel.

| Research/Strategy |

Year |

Compression Ratio (CR) |

Key Findings |

Challenges/Limitations |

| Helmore and Stokes |

1930 |

11.6 |

Attempted CI operation with hydrogen. Observed misfiring and violent detonation.(W. H. a. P. H. Stoke, 1930) |

Hydrogen’s characteristics make it challenging to ignite via compression alone. |

| Homan et al. (Glow Plug Assistance) |

1979 |

29 |

Glow plugs provided stable ignition, higher IMEP than diesel, and knock-free combustion. |

Continuous glow plug use led to efficiency losses due to thermal demands. |

| Ikegami et al. |

1982 |

18.6 |

Claimed successful hydrogen CI operation; later contested—possible ignition due to contaminants.(Ikegami et al., 1982) |

Ignition reliability was limited without pilot fuel or hot spots. |

| Rosati and Aleiferis |

2000 |

17.5 |

Achieved hydrogen ignition at 200-400°C intake with ultra-lean mixtures (Rosati & Aleiferis, 2009) |

Elevated intake temperatures increased NOx emissions and energy use. |

| Lee et al. |

2013 |

>40 |

Demonstrated possible hydrogen CI with CRs as high as 26-32(Lee et al., 2013) |

Narrow operating range with risk of knocking and backfire at high CRs. |

2. Method and Model

This model delineates the parametrization of hydrogen compared to dodecane as fuels in an internal combustion engine, assessing the ideal capabilities of hydrogen in practical applications. The simulation will first utilize n-Dodecane as the fuel due to its capacity to sustain combustion at moderate inlet temperatures, which is attributed to its low ignition temperature. This phase establishes a performance baseline for the engine operating at a specific compression ratio without necessitating additional heating. This stage employs the `nDodecane_Reitz.yaml` reaction mechanism, which encompasses the kinetics of dodecane combustion.

Upon achieving the dodecane baseline, the model will transition to modeling the removal of dodecane and utilizing hydrogen as the feedstock. Due to hydrogen’s elevated ignition temperature, increasing the input temperature will result in combustion occurring at the same compression ratio. Under these conditions, the model aims to initiate an initial heating phase. The next phase will entail simulating hydrogen combustion using the `gri30.yaml` reaction mechanism for hydrogen. After this phase, we will systematically adjust the hydrogen-fueled engine’s compression ratio and inlet temperature. The combustion of hydrogen will be modeled as the final step, tailored for the designed engine. Specific combustion characteristics may produce optimal efficiency values while minimizing nitrogen oxide emissions (NOx), particularly since these emissions tend to increase upon hydrogen ignition. The model establishes a baseline for engine testing with dodecane, transitions to hydrogen, adjusts initial temperature, and optimizes compression ratios and inlet temperature for hydrogen efficiency.

The Hydrogen engine operates at around 3000 rpm with a compression ratio of 20 as an initial run model(David G. Goodwin, 2023). The simulation utilizes the reaction mechanism file `gri30.yaml’, containing kinetic data for hydrogen and associated species. The fuel consists solely of hydrogen H2 and is combined with air (O2:1, N2:3.76)) . A temperature of 300 K. Air is supplied into the system at 450 K and a pressure of 1.3e5 Pa. In contrast, the outlet pressure is maintained at 1.2e5 Pa to simulate the typical expulsion of gases. Additional circumstances are an ambient temperature of 300 K and an ambient pressure of 1e5 Pa.

The engine’s geometry, including piston area, stroke, and crankshaft angles, is determined by characteristics such as displacement volume, piston diameter, and cycle volume at the top dead center (TDC). A sinusoidal velocity profile is enough to represent deformation in physics, as it will not be beyond the model’s physical dynamics constraints. To regulate gas intake and exhaust, valves are installed at the inlet and outlet, with specific friction coefficients and time for opening and shutting according on the crank angle. The inlet valve opens at -18 degrees and shuts at 198 degrees, while the outlet valve opens at 522 degrees and closes at 18 degrees. The fuel injector injects hydrogen slightly above the top dead center for efficient combustion. The injector is characterized by its opening and closing timings and primarily functions as a mass flow controller for regulating the quantity of hydrogen fuel. The model integrates intricate thermodynamic processes: heat release and expansion work, subsequently facilitating atmospheric calculations. Regarding the reduction of emissions, carbon monoxide levels decrease when the expansion power coefficient and the heat release rate coefficient are evaluated in fully operational engines during particular cycles. To achieve significant outcomes, the objective of combustion emissions is primarily to eradicate undesirable byproducts, such as carbon monoxide and nitrogen oxides, generated throughout the process. The model simulates a reactor’s cylindrical shape and reservoir for gas inflow and outflow, with valve timing and injector timing determined by crank angle. It includes pressure-volume and temperature-entropy diagrams, graphs, and gas distributions to understand engine thermodynamics and hydrogen fuel efficacy. It also predicts average CO and NOx emissions, indicating potential environmental harm.

Following the analysis of base diesel fuel and hydrogen fuel, we will investigate the impact of inlet temperature (Tin) and compression ratio (CR ) on heat release rate, expansion power, efficiency, and emissions the engine produces. This method uses hydrogen as the primary fuel, injected at the top dead center of an air-filled cylinder. Altering the input temperature and compression ratio modifies the operating circumstances, allowing the examination of emission characteristics and thermodynamic properties. The input temperature, representing the temperature of the air-fuel mixture supplied to the system before combustion, is a critical component influencing the pace of chemical reactions within the engine, hence impacting its heat release and power-generating capability. The compression ratio is the volume of a cylinder at the bottom dead center compared to the volume of the same cylinder at the top dead center. This volume ratio influences the air-fuel mixture’s temperature, density, efficiency, and emission levels. Typically, elevating both the inlet temperature and the compression ratio enhances the heat and power output; nevertheless, these increases concurrently exacerbate the generation of nitrogen oxides (NOx), the primary problem in the hydrogen combustion process.

The simulation utilizes the details above to produce specific performance and emission characteristics. The combustion heat release refers to the energy emitted during combustion, which may be calculated using the heat production rate formula, derived as the total heat generation across the heat engine cycle. In the context of expansion work, which refers to the work performed by expanding gases, the expansion work is incorporated throughout the process without considering the disparity between the cylinder and ambient pressure. Efficiency can be measured as the ratio of expansion work to total heat release, which can aid in assessing the engine’s effectiveness in converting energy under varied input temperatures and monitoring compression ratios of nitrogen oxide (NOx) emissions.

Piston Speed (Sinusoidal Approximation):

Parameter Symbols

Displaced volume

: Cylinder volume at top dead center

Piston area

: Piston diameter

Stroke: Stroke length

: Crank angle

: Engine speed (frequency)

Piston speed

Heat release rate

: Expansion work rate

: Efficiency

: NO emission estimate

: Mean molecular weight

: Mass flow rate out of the cylinder

: Mole fraction of CO in the exhaust

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Comparison of Performance and Combustion Characteristics of Diesel and Hydrogen Engines

The table compares Diesel and Hydrogen engines, highlighting the impact of increased input temperature on power production and efficiency. Hydrogen engines deliver an exceptional power output of 22.8 kW, due to their high energy density and combustion characteristics. The heat release rate for hydrogen engines at 450 K is 41.4 kW, indicating a more efficient and rapid combustion process. The efficiency of hydrogen engines is slightly reduced by around 55%. However, hydrogen generates no carbon dioxide emissions, highlighting its environmental advantages over diesel.

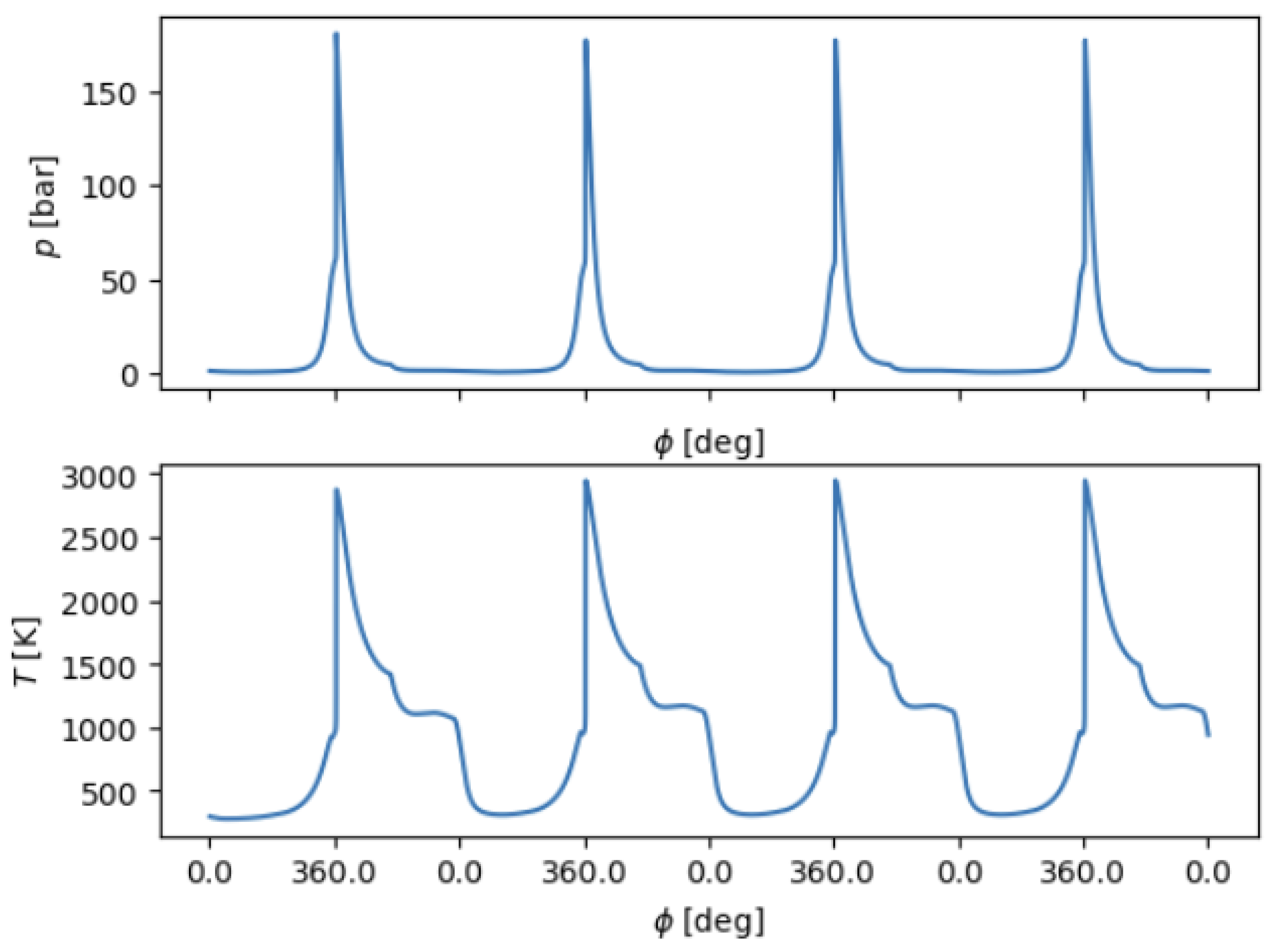

Figure 1.

Temperature and Pressure for Diesel Fuel in Compression Ignition Engine.

Figure 1.

Temperature and Pressure for Diesel Fuel in Compression Ignition Engine.

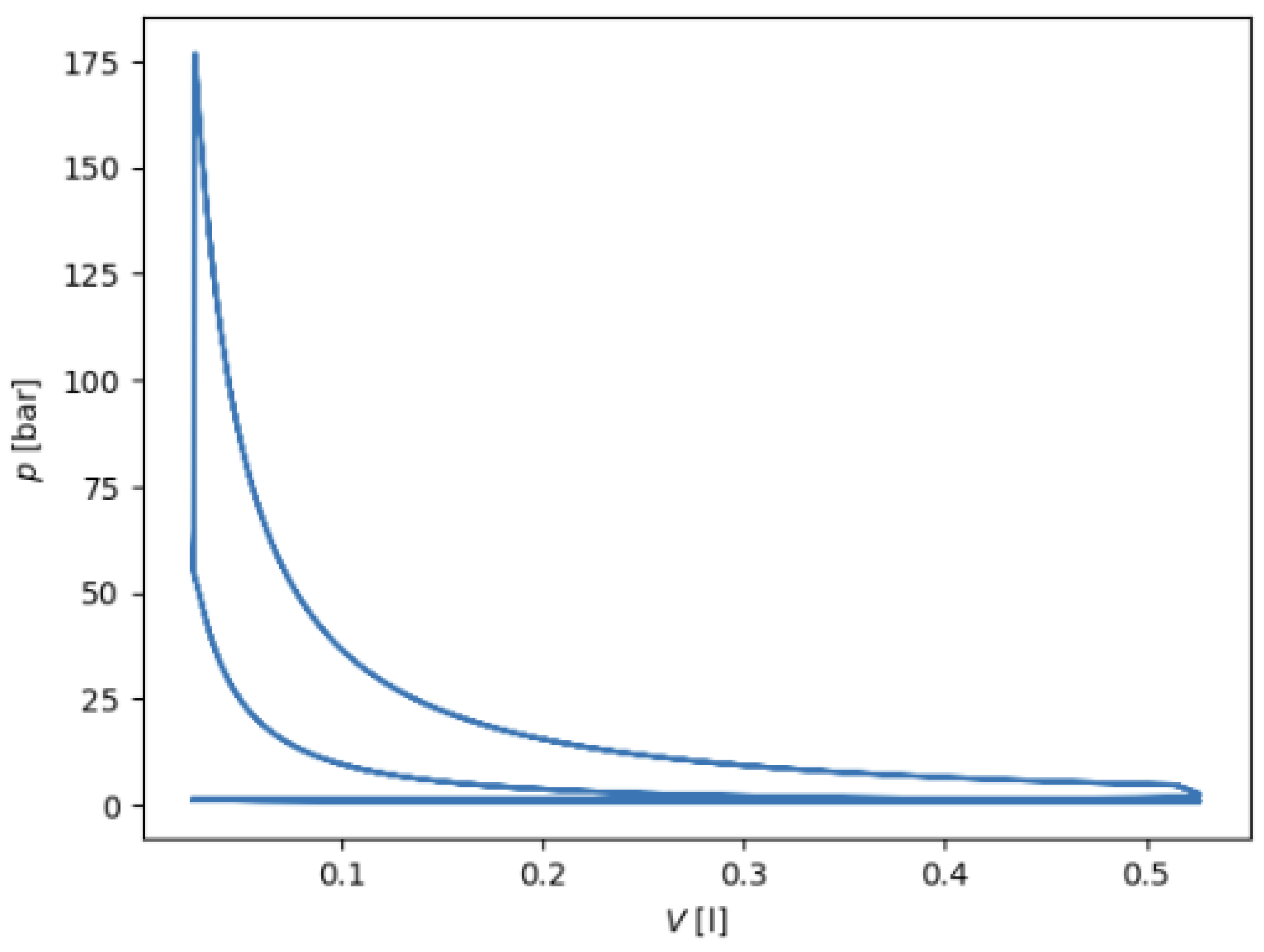

Figure 2.

PV Diagram for Diesel fuel Compression Ignition Engine (Injection).

Figure 2.

PV Diagram for Diesel fuel Compression Ignition Engine (Injection).

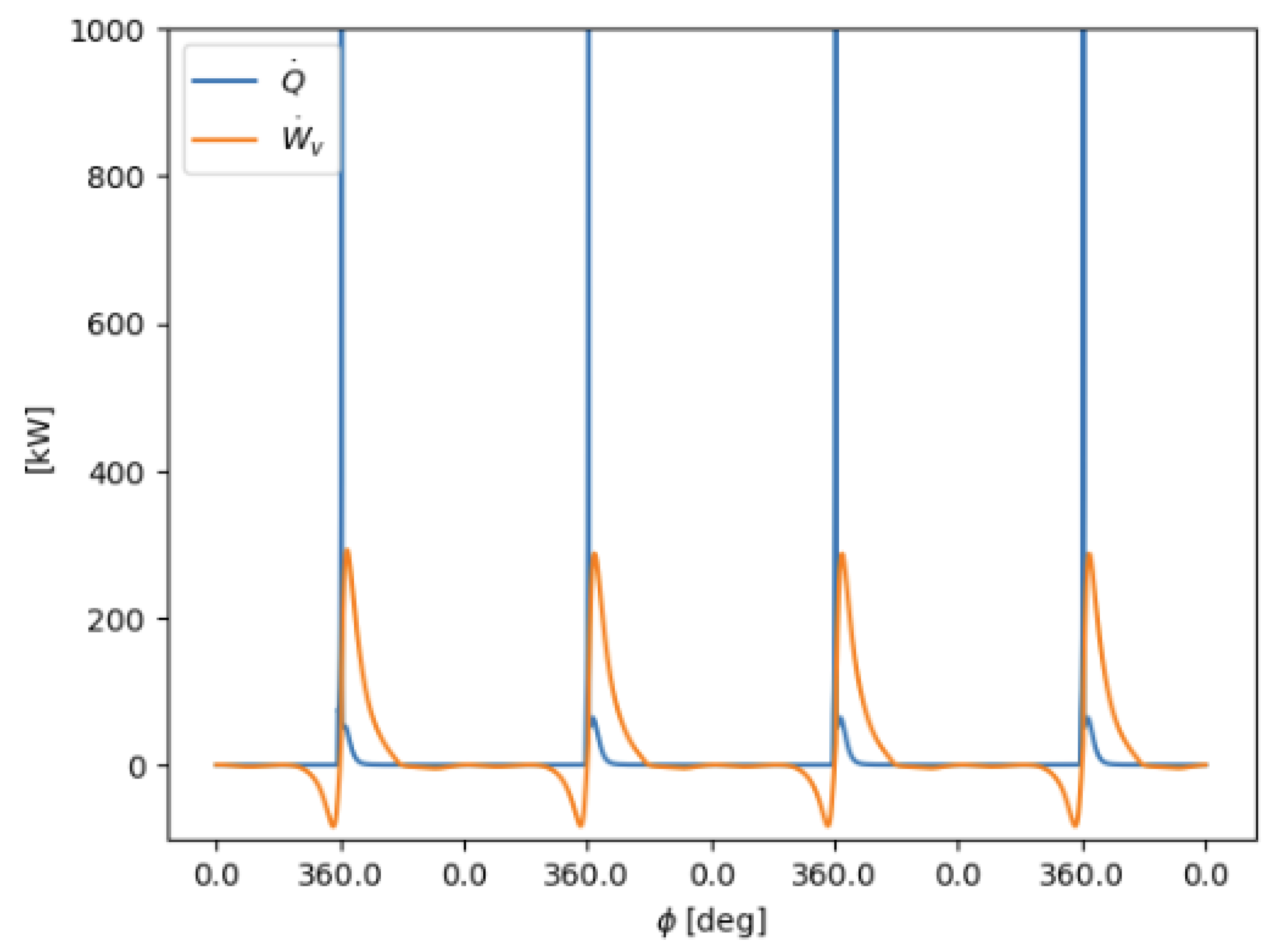

Figure 3.

Thermal and Energy Emission of Diesel Fuel in Compression Ignition Engines.

Figure 3.

Thermal and Energy Emission of Diesel Fuel in Compression Ignition Engines.

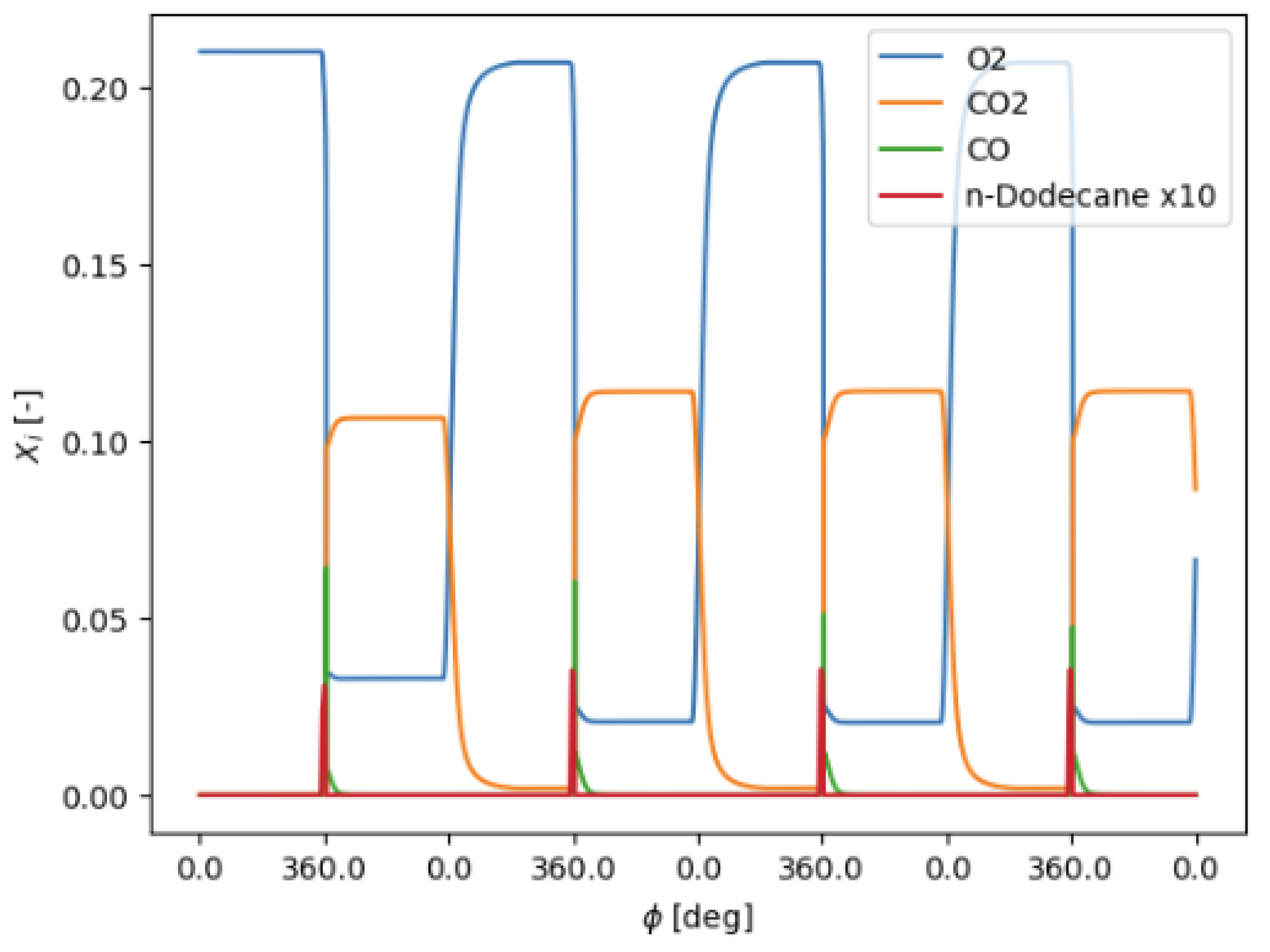

Figure 4.

Mole Fraction of Diesel Fuel in Compression Engine (n-Dodecane).

Figure 4.

Mole Fraction of Diesel Fuel in Compression Engine (n-Dodecane).

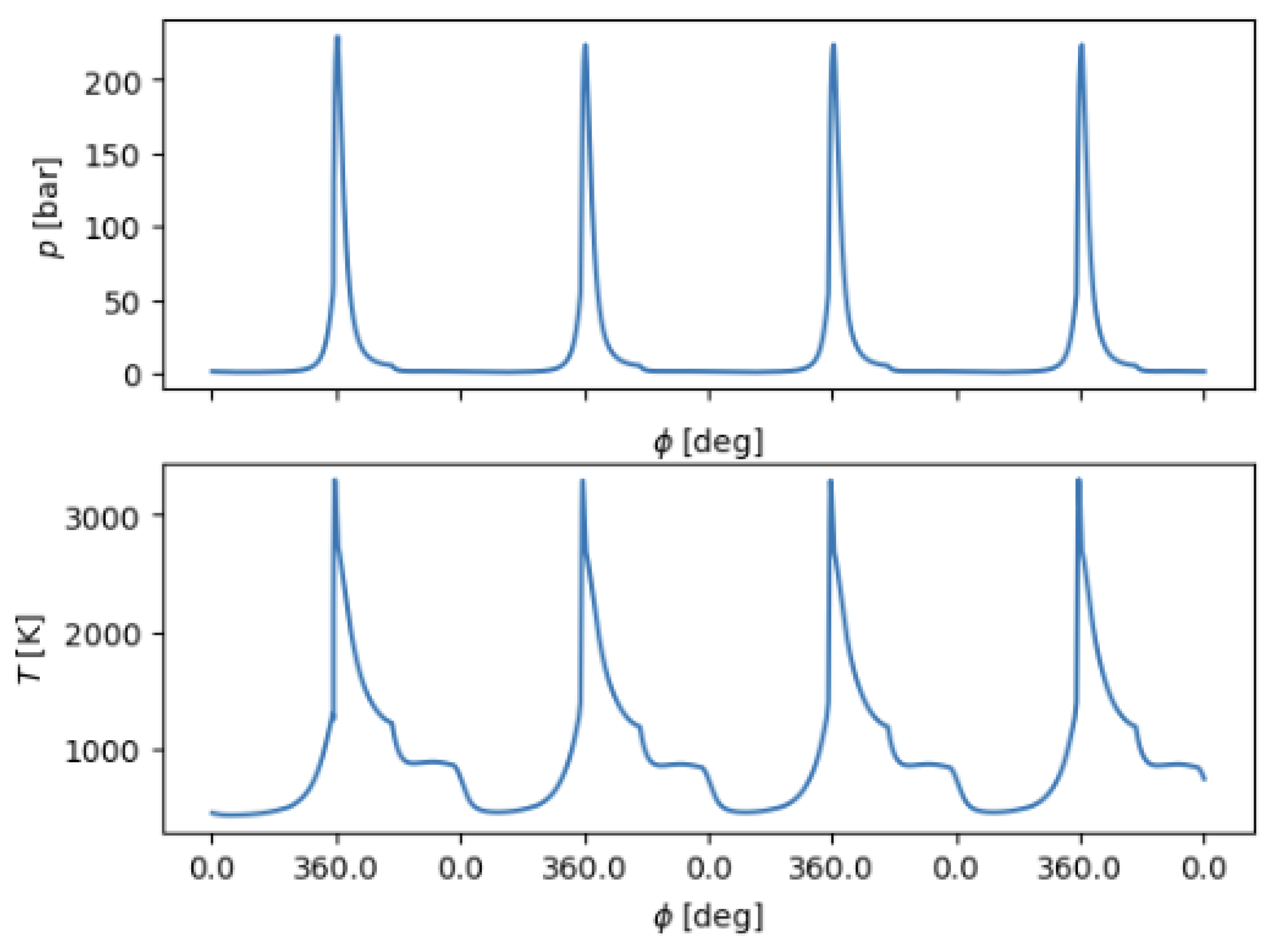

Figure 5.

Temperature and Pressure for Hydrogen Fuel in Compression Ignition Engine.

Figure 5.

Temperature and Pressure for Hydrogen Fuel in Compression Ignition Engine.

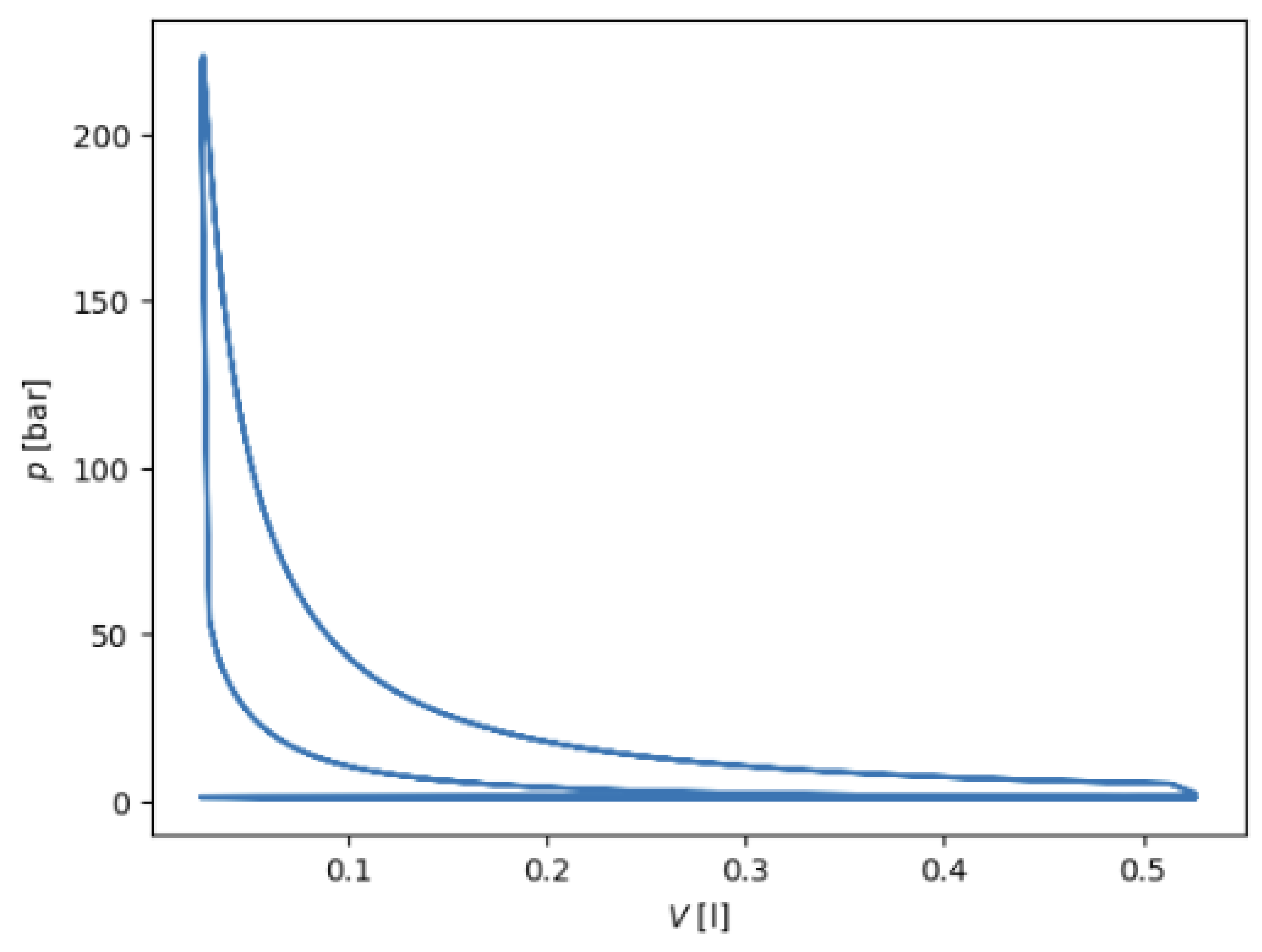

Figure 6.

PV Diagram for Hydrogen fuel Compression Ignition Engine (Injection).

Figure 6.

PV Diagram for Hydrogen fuel Compression Ignition Engine (Injection).

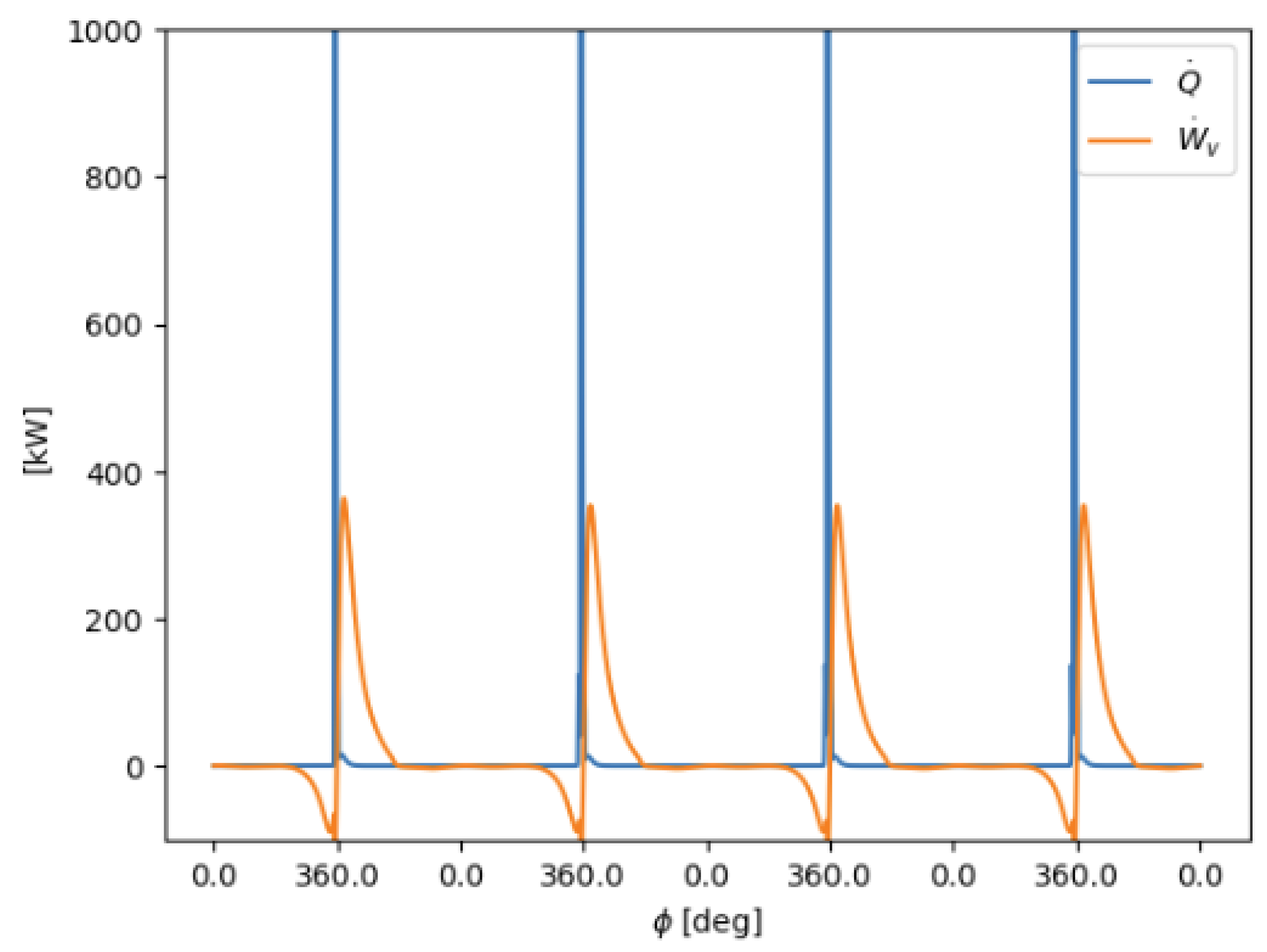

Figure 7.

Thermal and Energy Emission of Hydrogen Fuel in Compression Ignition Engines.

Figure 7.

Thermal and Energy Emission of Hydrogen Fuel in Compression Ignition Engines.

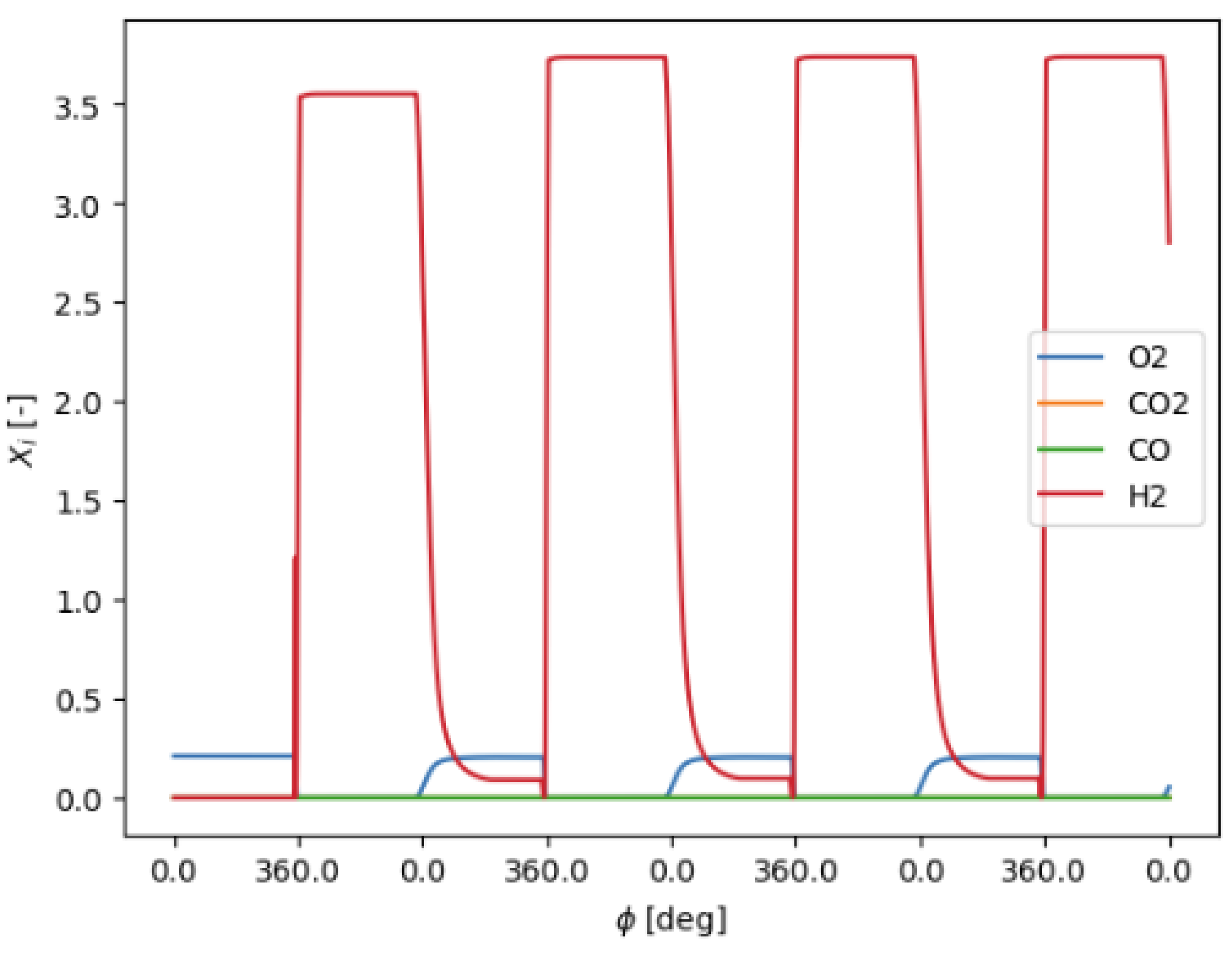

Figure 8.

Mole Fraction of Diesel Fuel in Compression Engine (n-Dodecane).

Figure 8.

Mole Fraction of Diesel Fuel in Compression Engine (n-Dodecane).

Table 2.

Comparison Diesel and Hydrogen engines, emphasizing the influence of temperature on power output and efficiency.

Table 2.

Comparison Diesel and Hydrogen engines, emphasizing the influence of temperature on power output and efficiency.

| Parameter |

Diesel Engine (n-Dodecane) |

Hydrogen Engine |

| Reaction Mechanism |

nDodecane_Reitz.yaml |

gri30.yaml |

| Fuel Composition |

c12h26:1 (n-Dodecane) |

H2:1 (Hydrogen) |

| Inlet Temperature (K) |

300 |

450 |

| Compression Ratio (ε) |

20 |

20 |

| Engine Speed (rpm) |

3000 |

3000 |

| Displaced Volume (m³) |

5.00E-04 |

5.00E-04 |

| Piston Diameter (m) |

0.083 |

0.083 |

| Expansion Power (kW) |

18.5 |

22.8 |

| Heat Release Rate (kW) |

32.9 |

41.4 |

| Efficiency (%) |

56.3 |

55 |

| CO Emission (ppm) |

8.9 |

0 |

| Inlet Valve Angle (deg) |

-18 (open) to 198 (close) |

-18 (open) to 198 (close) |

| Outlet Valve Angle (deg) |

522 (open) to 18 (close) |

522 (open) to 18 (close) |

| Injector Angle (deg) |

350 (open) to 365 (close) |

350 (open) to 365 (close) |

The research analyzes the combustion properties of hydrogen engines about diesel engines. Diesel engines reach a peak combustion temperature of around 2500 K, which rises sharply at the top dead center (TDC) throughout each cycle and decreases as the gas expands. This signifies controlled combustion with a prolonged burn duration. Conversely, the hydrogen engine reaches a maximum temperature of approximately 3000 K, much surpassing that of the diesel engine due to its higher energy density and quick combustion characteristics. The pressure profiles in diesel engines resemble those in hydrogen engines, reaching a maximum pressure of approximately 200 bar, which signifies increased flame velocity and improved combustion efficiency. The pressure peaks are more prominent and align with TDC, indicating a virtually instantaneous ignition and combustion. The P-V diagram for a diesel engine illustrates a standard cycle arrangement characterized by a notable delay in pressure increase resulting from the time required for fuel-air mixture formation and ignition following injection. The expansion phase is prolonged, indicating the gradual release of energy and reduction in pressure. The rapid combustion cycle of the hydrogen engine leads to heightened peak temperatures and pressures, augmenting power output but potentially jeopardizing cycle stability and elevating NOx emissions.

In summary, the hydrogen engine produces higher peak temperatures and pressures, exhibits faster combustion, and has more abrupt cycle phases than the diesel engine. These differences underscore hydrogen’s promise for improved power density while revealing challenges related to managing rapid variations in pressure and temperature.

3.2. The Effect of Compression Ratio and Inlet Temperature on Engine Performance and Emissions

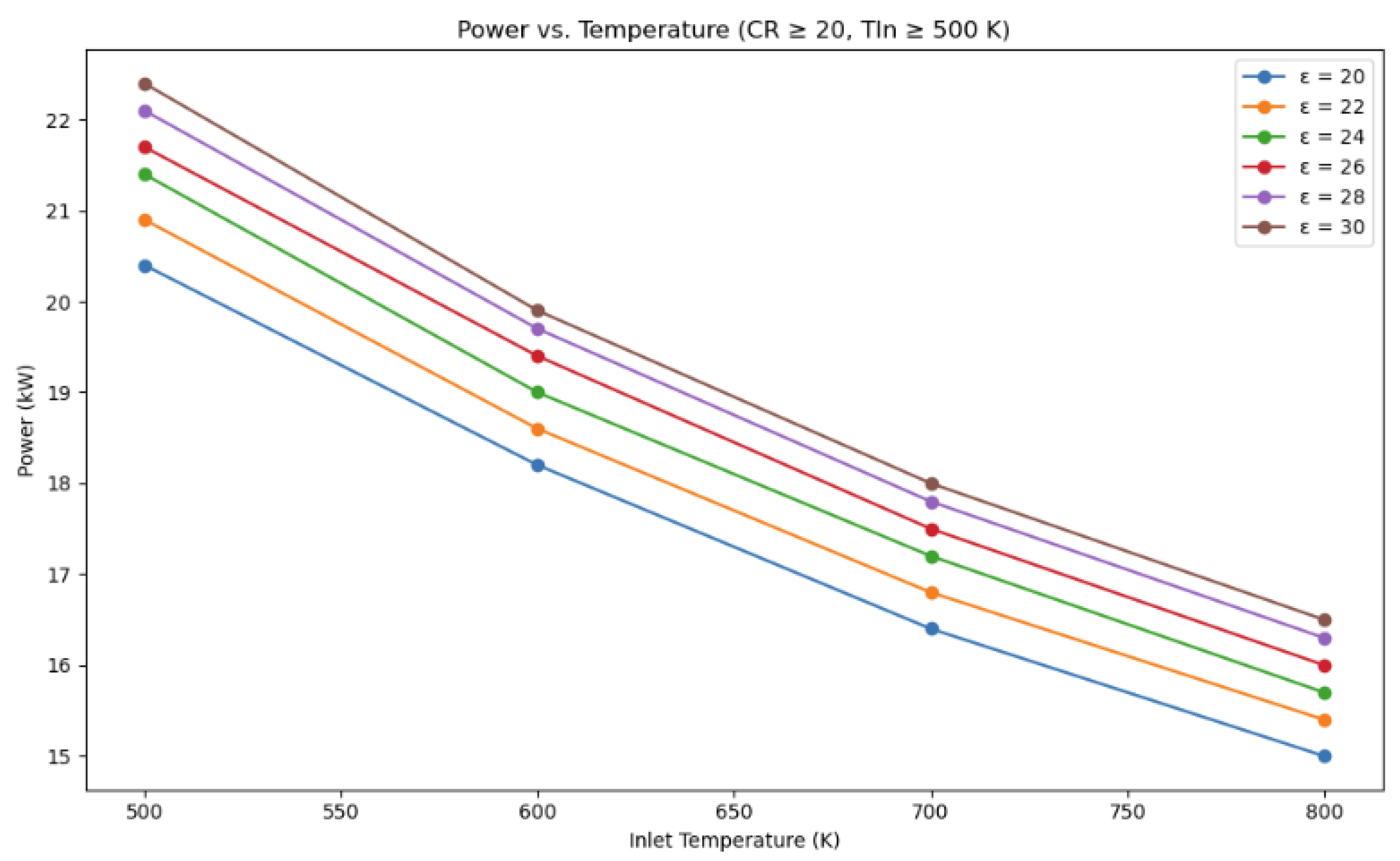

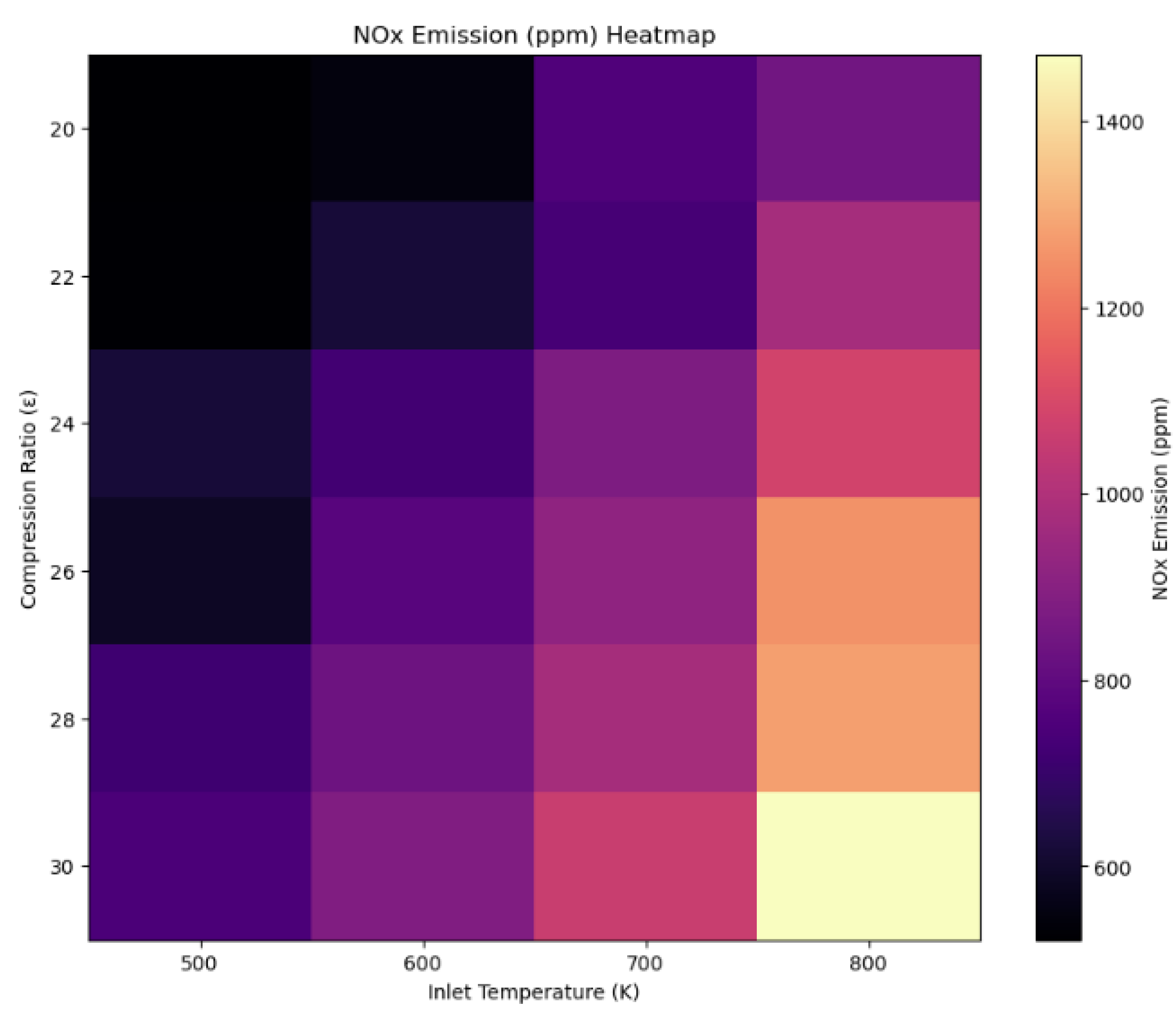

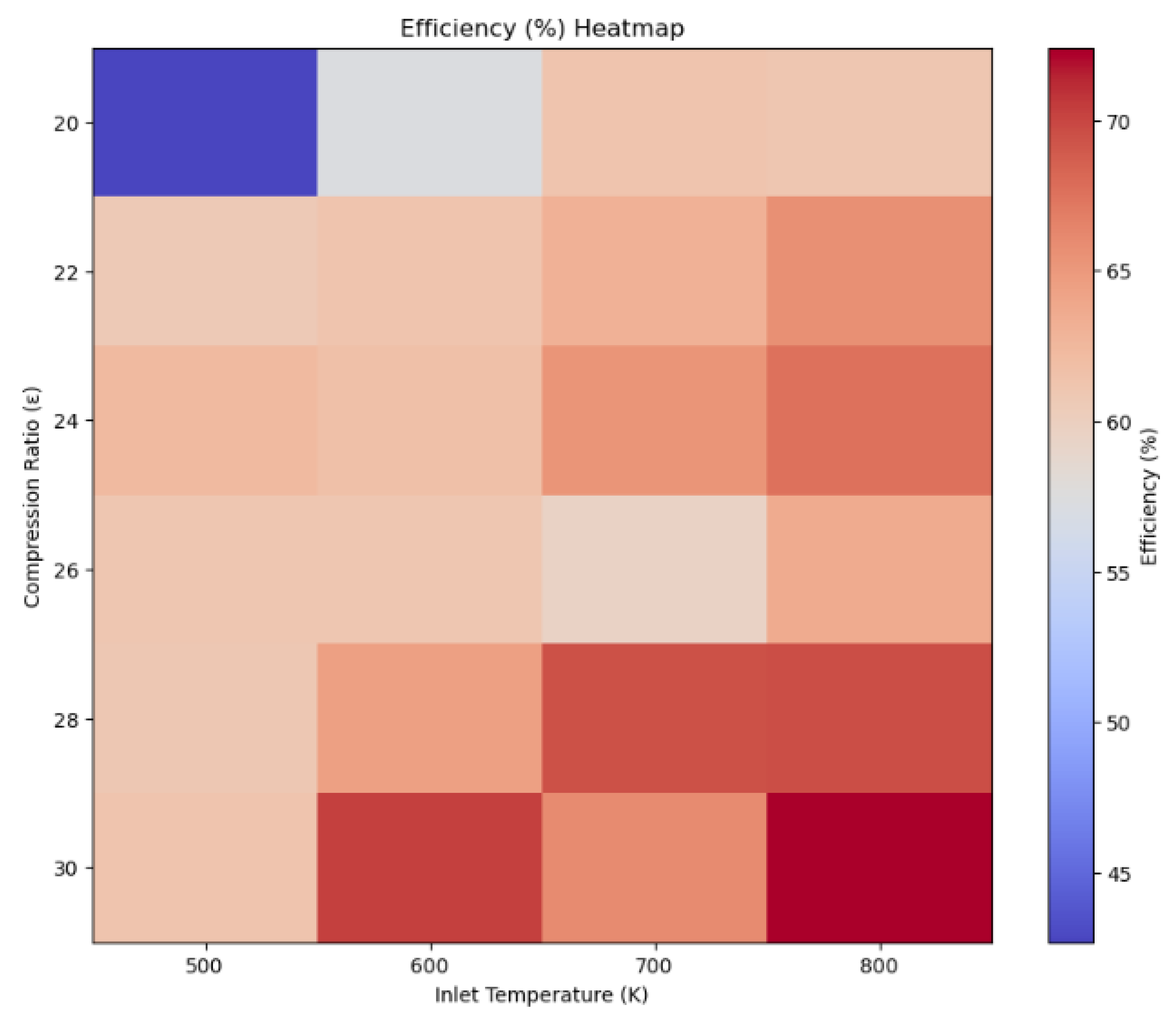

The performance characteristics of a hydrogen engine, including power, NOx emissions, and efficiency, exhibit a direct correlation with variations in compression ratio and induction temperature. This study highlights the impact of preheating or heating the incoming air on performance indicators, specifically discussing the feasibility of converting diesel engines to operate on hydrogen fuel. Dependence of Power and Efficiency on Inlet Temperature. In a hydrogen engine, an increase in inlet temperature enhances the hydrogen combustion process, thus affecting both power output and efficiency improvements, as depicted in

Figure 9. As the input temperature rises from 500 K to 800 K, the power output consistently increases across all compression ratios. For instance, with a compression ratio of 20, within the range of 500 K to 800 K, the output escalated from around 15 kW to nearly 18 kW. This results from enhancements that yield superior fuel-air mixes and a reduced ignition delay, so facilitating more complete combustion. A rise in inlet temperature leads to improved efficiency.

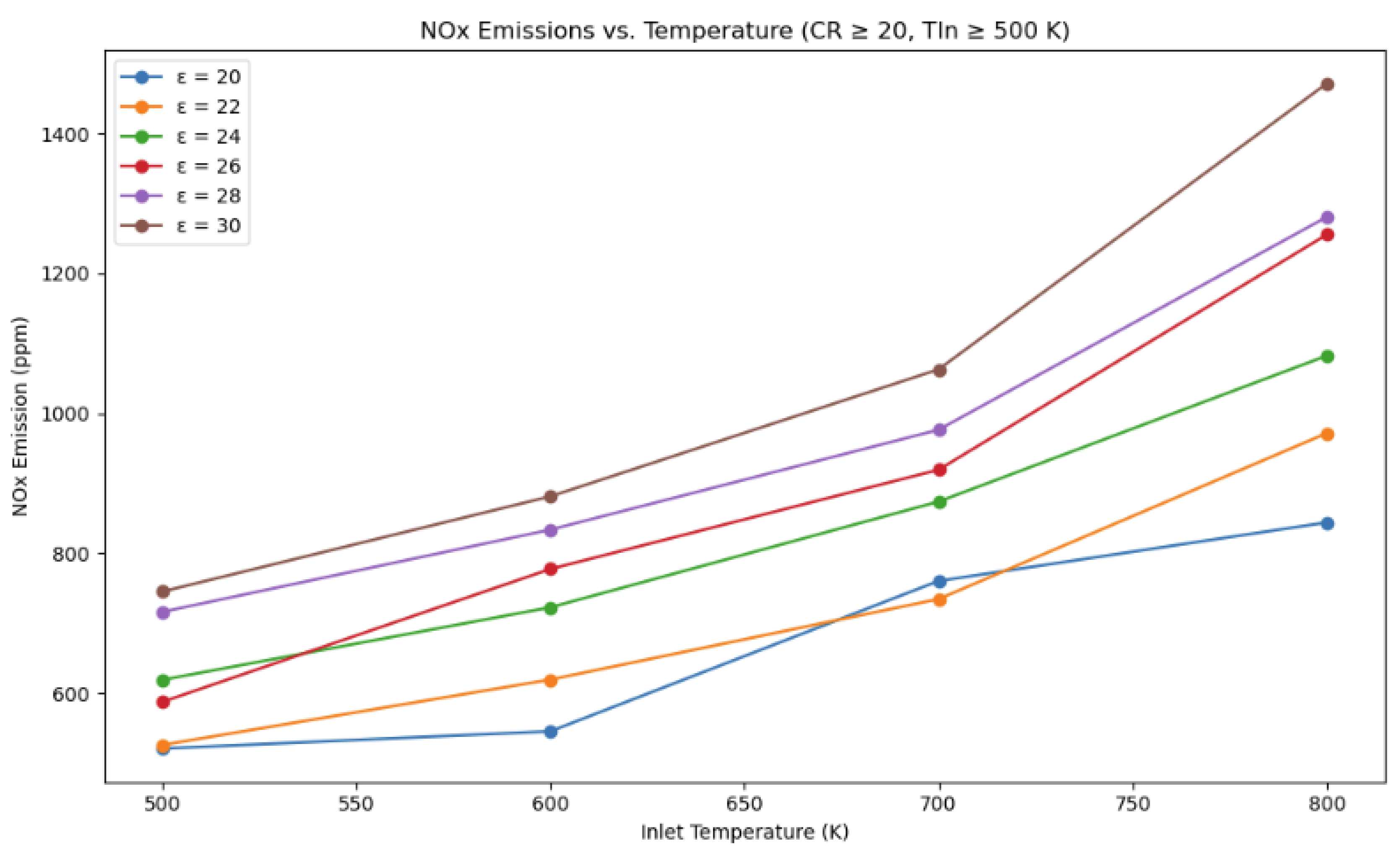

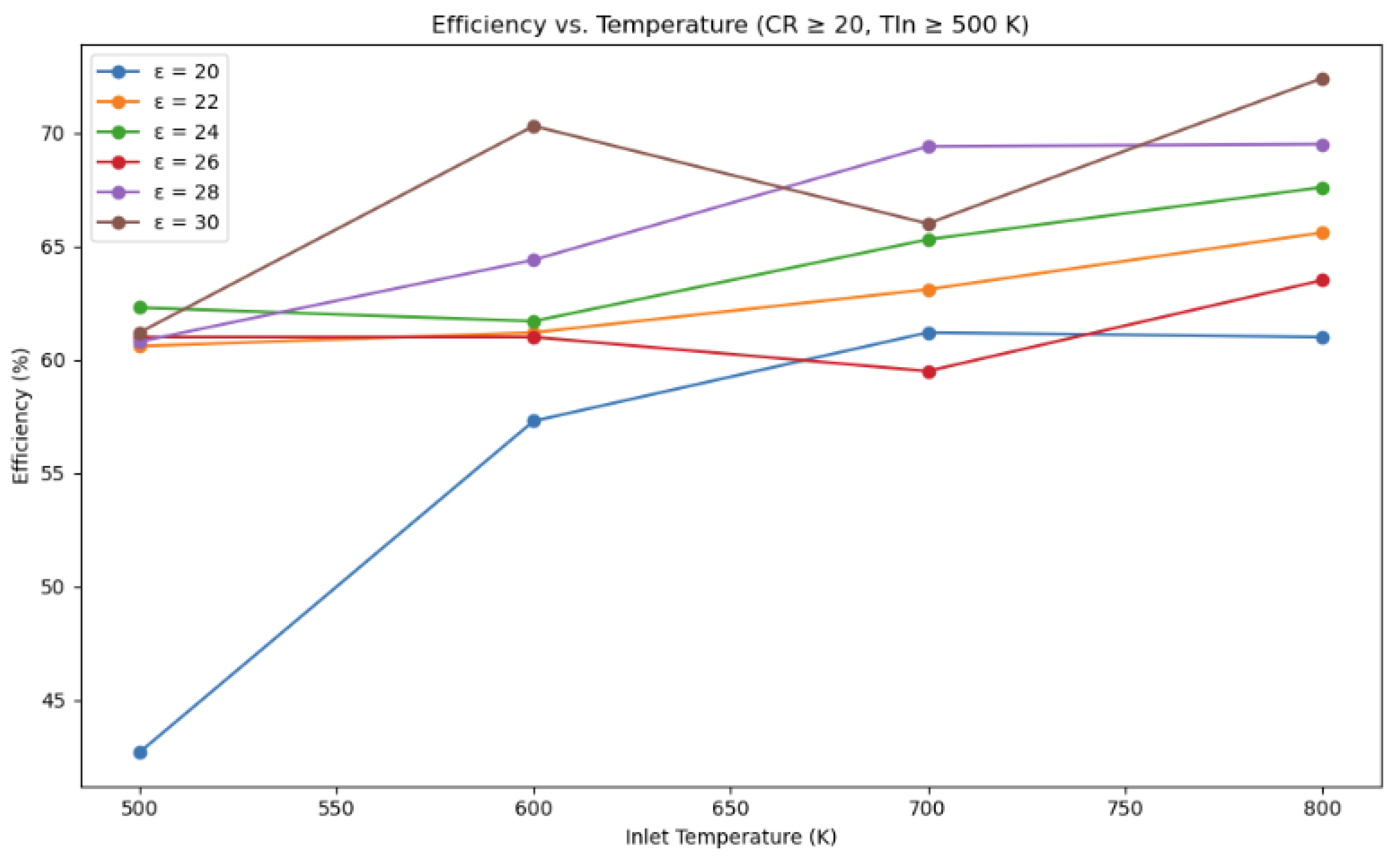

Figure 11 illustrates that efficiency rises with increased input temperature, particularly at moderate compression ratios. With a compression ratio of twenty and an input temperature of 800 K, the efficiency approaches over 70%, a theoretical situation that is not easy to achieve, in contrast, approximately 60% at 500 K. Hydrogen can be utilized more efficiently within an engine. Overall fuel consumption can be reduced if hydrogen is illuminated or preheated in advance to achieve optimal combustion temperatures rapidly. This approach relies on the thermodynamic properties of hydrogen, which might be detrimental without preheating due to its elevated specific energy and combustion rate. The Significance of Compression Ratio and NOx Emissions. The elevated input temperatures augment NOx emissions owing to the significant temperature sensitivity of NOx production. The utilization of elevated compression ratios worsens this problem.

Figure 10 illustrates that NOx emissions increase significantly when the input temperature ascends from 669 K to levels typically exceeding the average of the other temperatures when the average is over 600 K. For instance, it is noted that NOx emissions with a 30:1 compression ratio and 800 K exceed 1400 ppm, in contrast to the 600 ppm reported for a 20:1 compression ratio and 500 K. Constraints on Compression Ratios in Diesel-to-Hydrogen Conversions The Impact of Elevated Compression Ratio in Hydrogen Engines Elevated compression ratios in hydrogen engines induce increased mechanical and thermal strains, which may contrast with diesel engines that were exceptionally engineered for different fuel characteristics. This contradicted the diesel engine’s intended operational compression ratio of fifteen to twenty. Nonetheless, this range increases with hydrogen fuel to twenty-six to thirty, leading to preignition due to hydrogen’s minimal ignition energy. A moderate compression ratio is crucial to avert knocking and excessive wear in diesel engines operating on hydrogen. This alteration is essential for the reliability and safety of engines following conversion.

Figure 9.

The effect of compression ratio and Inlet temperature on Hydrogen Engine Power.

Figure 9.

The effect of compression ratio and Inlet temperature on Hydrogen Engine Power.

Figure 10.

The effect of compression ratio and Inlet temperature on Hydrogen Engine NOx Emissions.

Figure 10.

The effect of compression ratio and Inlet temperature on Hydrogen Engine NOx Emissions.

Figure 11.

The effect of compression ratio and Inlet temperature on Hydrogen Engine efficiency.

Figure 11.

The effect of compression ratio and Inlet temperature on Hydrogen Engine efficiency.

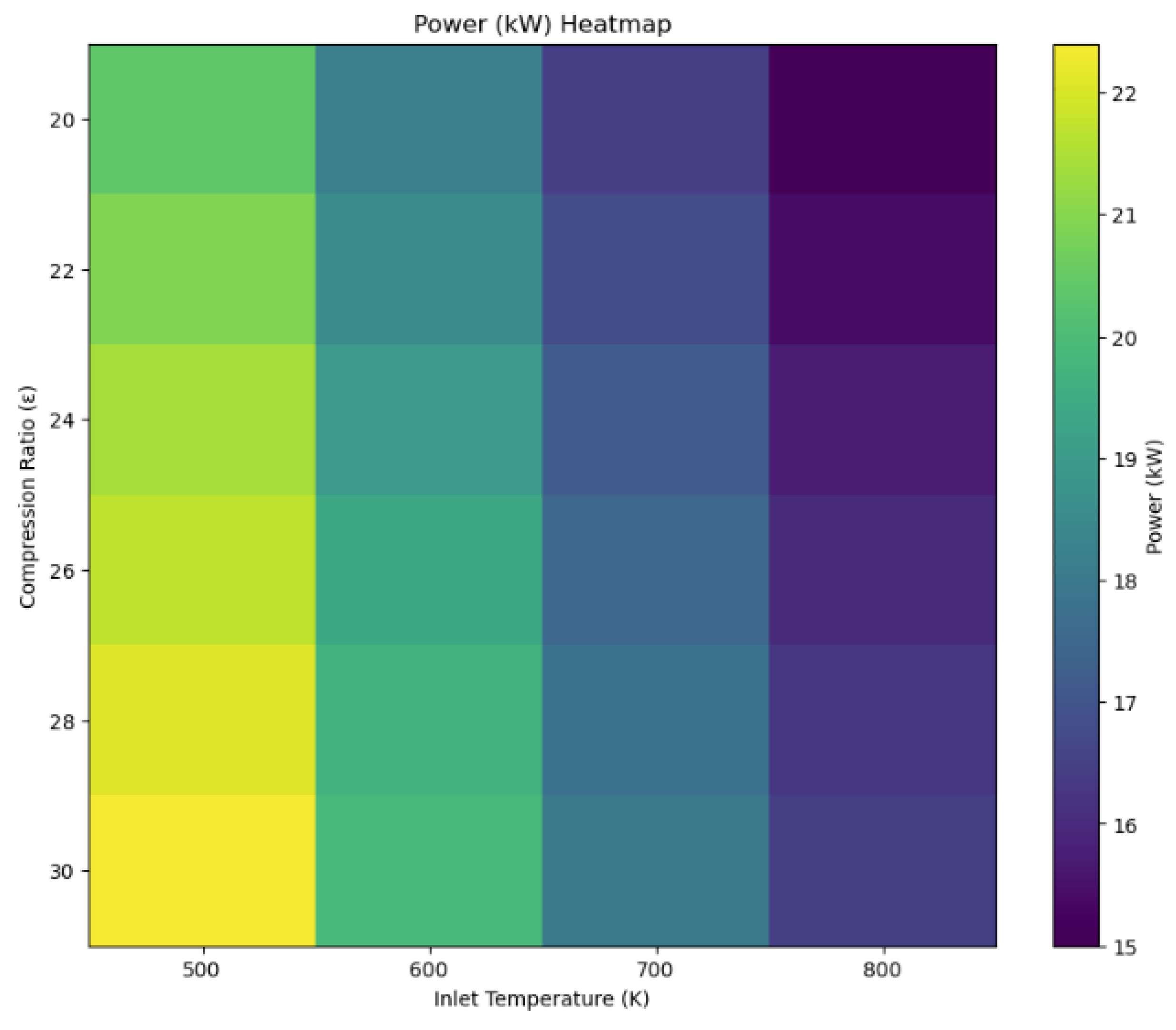

Figure 12.

Power Heat Map.

Figure 12.

Power Heat Map.

Figure 14.

Efficiency Heat Map.

Figure 14.

Efficiency Heat Map.

Preheating the intake air in converting diesel engines to hydrogen fuel seems more advantageous than augmenting the compression ratio. Elevating the input temperature while maintaining a compression ratio of approximately twenty can achieve a compromise. This functions to protect the engine design. This technology facilitates performance enhancement without subjecting the engine to harsh conditions that may jeopardize its integrity. Raising the input temperature from 500 K to 600 K can augment hydrogen engine power production while reducing NOx emissions and preventing excessive mechanical stress. This modest preheating temperature improves power generation and efficiency while ensuring acceptable NOx emissions. Increasing the input temperature to 600 K markedly enhances power and efficiency at all compression ratios while maintaining low NOx emissions. This temperature range is especially beneficial for converted diesel engines, as original specs do not allow for significant safe modifications. Thus, hydrogen engines demonstrate enhanced overall power and thermal efficiency with an increase in inlet temperature, with optimal performance at around 600 K to 800 K and moderate compression ratios of 20-24. However, an increase in the compression ratio may lead to a rise in temperature, hence elevating NOx emissions and requiring the implementation of mitigation methods. Co-firing diesel with hydrogen produces optimal results when moderate compression ratios and preheating techniques are utilized, leading to improved performance, decreased engine wear, and lower emissions. This method may yield roughly 18-22 kW of power with an efficiency of 65-70%, while NOx emissions are maintained below 1000 ppm, primarily attributable to moderate compression ratios. Increasing the input temperature from 500 K to 600 K markedly improves the efficiency of hydrogen engines, reduces NOx emissions, and mitigates material stress, so aiding the transition.

4. Validation

Previous studies have further detailed the numerical validation (Sharma & Dhar, 2018)of the results, highlighting the efficacy and challenges of hydrogen as a fuel in compression ignition (CI) engines(Tsujimura & Suzuki, 2017. The numerical computations demonstrate that hydrogen engines may provide an expansion power of up to 22.8 kW and emit 41.4 kW of heat at a 450 K inlet temperature, achieving a maximum efficiency of 55%. This supports the research of (W. H. a. P. H. Stoke, 1930), who documented early investigations into hydrogen as a combustion fuel and observed challenges in its ignition, including instances of backfire. The numerical findings similarly underscore these problems since hydrogen’s elevated energy density and swift combustion rate lead to increased peak temperatures (about 3000 K) and pressures (almost 200 bar), which may complicate cycle stability, as noted in this work. The results of this investigation on NOx emissions align with the data analysis conducted by (Rosati & Aleiferis, 2009), who successfully ignited hydrogen; nevertheless, they found increased NOx emissions at elevated intake temperatures of 200-400°C. The numerical data reflects that an increase in input temperature from 500 K to 800 K enhances combustion efficacy, while simultaneously elevating NOx emissions at elevated compression ratios(Chintala & Subramanian, 2014). This claim is further supported by Lee et al., who showed that hydrogen compression ignition can occur at ratios exceeding 26:1. However, their operational limits are constrained due to the risks of knocking and backfiring, which are also illustrated in the numerical predictions of hydrogen engines at elevated compression levels. The numerical analysis corroborates the previous findings of (Ikegami et al., 1982), which indicated that ignition stability and “quiet burning” were achieved through the injection of pilot fuel or the placement of hot spots. The current numerical model does not incorporate pilot fuel; however, the data confirms that employing moderate compression ratios alongside elevated intake temperatures facilitates effective ignition and combustion of fuel, resembling a “quiet burning” phenomenon. Furthermore, the authors substantiate their application of hydrogen to improve combustion efficacy with the glow plug, as the findings indicate that preheating the intake to around 500–600 K can achieve a performance of approximately 18–22 kW at 65-70% efficiency, especially at moderate compression ratios. To attain adequate combustion while minimizing NOx emissions, moderate preheating is essential, as highlighted by (T. Chaichan and D. S. M. Al-Zubaidi, 2015) in their discussion of the benefits of regulated hydrogen injection with moderate compression ratios for regulating NOx emissions and combustion dynamics. Ultimately, Sharma and Dhar’s models indicated that moderate compression ratios with hydrogen-diesel mixes would result in minimal or negligible violent combustion, corroborating the simulations’ conclusions that a compression ratio of approximately 20, with an input temperature of 600 K, yielded ideal circumstances. The findings demonstrate that this combination optimizes power and efficiency while maintaining NOx emissions below 1000 ppm, facilitating hydrogen integration into diesel engines without compromising design.

5. Conclusion

Recent research(Efstathios-Al. Tingas, 2023) (Tingas & Taylor, 2023)indicates that adapting compression ignition engines (CI) for hydrogen gas operation is more promising than modifying diesel engines. (Rosati & Aleiferis, 2009) Established that hydrogen combustion for ignition is viable at elevated intake temperatures and lean mixtures, albeit with heightened NOx emissions. (Lee et al., 2013) examined the viability of hydrogen combustion injection at high levels, markedly improving engine performance while recognizing the difficulties associated with knocking and backfiring. These initiatives significantly support the development of hydrogen engines, which operate with high efficiency but demonstrate a delayed starter due to the requirement of heating to address challenges associated with the high autoignition temperature of hydrogen. Our research suggests that hydrogen compression ignition engines, with modest preheating (500-600K) and compression ratios (20-24), can achieve efficiencies over 55% within these parameters. Our numerical modeling corroborates previous research and offers a comprehensive computational framework that may be tailored for practical commercial applications post-testing. We examine the parametric modifications of input temperatures and compression ratios via numerical simulations, illustrating that the combustion properties of hydrogen are markedly improved when normalized by optimization potential. These models may serve as prototypes for future efforts to improve hydrogen CI engines, aiming for high efficiency in practical environments, so supporting a gradual shift to industrial implementation. Ultimately, especially considering the persistent demand for sustainable alternatives in the automotive and energy sectors, the application of hydrogen in compression ignition diesel engines seems feasible. This change improves the prospects for combined heat and power applications due to hydrogen’s high combustion temperature and rapid heat release rate. Hydrogen engines that leverage this auxiliary heat would have improved combined heat and power (CHP) systems, hence augmenting energy efficiency in electricity generation. Pre-heated hydrogen compression ignition engines appear to be an environmentally sustainable approach for generating heat and power, consistent with global climate initiatives, as demonstrated by this study.

References

- Chintala, V. , & Subramanian, K. A. Hydrogen energy share improvement along with NOx (oxides of nitrogen) emission reduction in a hydrogen dual-fuel compression ignition engine using water injection. Energy Conversion and Management 2014, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, G. Goodwin, H. K. M. I. S. R. L. S. and B. W. Weber. (2023). Cantera: An object-oriented software toolkit for chemical kinetics, thermodynamics, and transport processes. https://www.cantera.org, 2023. Version 3.0.0. Cantera.

- Dimitriou, P. (2023). Hydrogen Compression Ignition Engines. In Green Energy and Technology: Vol. Part F1098. [CrossRef]

- Efstathios-Al. Tingas. (2023). Hydrogen for Future Thermal Engines.

- Homan, H. S. , Reynolds, R. K., De Boer, P. C. T., & McLean, W. J. Hydrogen-fueled diesel engine without timed ignition. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 1979, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikegami, M. , Miwa, K., & Shioji, M. A study of hydrogen fuelled compression ignition engines. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 1982, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikegami, M. , Miwa, K., Shioji, M., & Esaki, M. STUDY ON HYDROGEN-FUELED DIESEL COMBUSTION. Bulletin of the JSME 1980, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, G. A. Hydrogen as a spark ignition engine fuel. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2003, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. J. , Kim, Y. R., Byun, C. H., & Lee, J. T. Feasibility of compression ignition for hydrogen fueled engine with neat hydrogen-air pre-mixture by using high compression. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosati, M. F. , & Aleiferis, P. G. (2009). Hydrogen SI and HCCI combustion in a Direct-Injection optical engine. SAE Technical Papers. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P. , & Dhar, A. Compression ratio influence on combustion and emissions characteristic of hydrogen diesel dual fuel CI engine: Numerical Study. Fuel 2018, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stępień, Z. A comprehensive overview of hydrogen-fueled internal combustion engines: Achievements and future challenges. Energies 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Chaichan and D. S. M. Al-Zubaidi. A practical study of using hydrogen in dual—fuel compression ignition engine. International Publication Advanced Science Journal 2015, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Tingas, E. Al, & Taylor, A. M. K. P. (2023). Hydrogen: Where it Can Be Used, How Much is Needed, What it May Cost. In Green Energy and Technology: Vol. Part F1098. [CrossRef]

- Tsujimura, T. , & Suzuki, Y. The utilization of hydrogen in hydrogen/diesel dual fuel engine. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. H. a. P. H. Stoke. (1930). Hydrogen-cum-oil gas as an auxiliary fuel for airship compression ignition engines. British Royal Aircraft Establishment. Report No. E 3219, .

- Wróbel, K. , Wróbel, J., Tokarz, W., Lach, J., Podsadni, K., & Czerwiński, A. Hydrogen Internal Combustion Engine Vehicles: A Review. Energies 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Furuhama and Y. Kobayashi. A liquid hydrogen car with a two-stroke direct injection engine and LH2-pump. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 1982, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. L. Yip et al. A review of hydrogen direct injection for internal combustion engines: Towards carbon-free combustion. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Hwang, K. Maharjan, and H. J. Cho. A review of hydrogen utilization in power generation and transportation sectors: Achievements and future challenges. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Qi, W. Liu, S. Liu, W. Wang, Y. Peng, and Z. Wang. A review on ammonia-hydrogen fueled internal combustion engines. Transportation 2023, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. C. Chiong et al. Advancements of combustion technologies in the ammonia-fuelled engines. Energy Conversion and Management 2021, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Ghojel, Fundamentals of Heat Engines: Reciprocating and Gas Turbine Internal Combustion Engines. 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. F. Taylor, Internal Combustion Engine in Theory and Practice. 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. Kirkpatrick, Internal Combustion Engines: Applied Thermo-sciences, Fourth Edition. 2020. [CrossRef]

- G. Di Blasio, A. K. G. Di Blasio, A. K. Agarwal, G. Belgiorno, and P. C. Shukla. Introduction to Application of Clean Fuels in Combustion Engines. Energy, Environment, and Sustainability 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghbouli, W. Yang, H. An, S. Shafee, J. Li, and S. Mohammadi. Modeling knocking combustion in hydrogen assisted compression ignition diesel engines. Energy 2014, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. Kreider and K. Shanley. Parametric Analysis of a Stirling Engine Using Engineering Equation Solver. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Verhelst. Recent progress in the use of hydrogen as a fuel for internal combustion engines. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Zhu and B. Shu. Recent Progress on Combustion Characteristics of Ammonia-Based Fuel Blends and Their Potential in Internal Combustion Engines. International Journal of Automotive Manufacturing and Materials 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. Galloni, D. Lanni, G. Fontana, G. D’antuono, and S. Stabile. Performance Estimation of a Downsized SI Engine Running with Hydrogen. Energies 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- College of the desert. Hydrogen Engine.

- Wimmer and, F. Gerbig. Hydrogen direct injection a combustion concept for the future. AutoTechnology 2006, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Klein and G. Nellis. Engineering equation solver (EES) for microsoft windows operating systems, professional versions. Madison USA, WI: F-chart software;, 2014.

- M. Ilhan Ilhak, S. Tangoz, S. Orhan Akansu, and N. Kahraman. Alternative Fuels for Internal Combustion Engines. The Future of Internal Combustion Engines 2019. [CrossRef]

- CIBSE. AM12 Combined heat and power for buildings (2013). 2013.

- C. Tornatore, L. Marchitto, P. Sabia, and M. De Joannon. Ammonia as Green Fuel in Internal Combustion Engines: State-of-the-Art and Future Perspectives. Frontiers in Mechanical Engineering 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Gatts, S. Liu, C. Liew, B. Ralston, C. Bell, and H. Li. An experimental investigation of incomplete combustion of gaseous fuels of a heavy-duty diesel engine supplemented with hydrogen and natural gas. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASHRAE, Combined Heat and Power Design Guide. 2015.

- C. C. S. Reddy and G. P. Rangaiah, Waste Heat Recovery: Principles and Industrial Applications. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Vogel. Thermodynamics, by S. Klein and G. Nellis. Contemporary Physics 2013, 54. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).