Submitted:

28 November 2024

Posted:

30 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

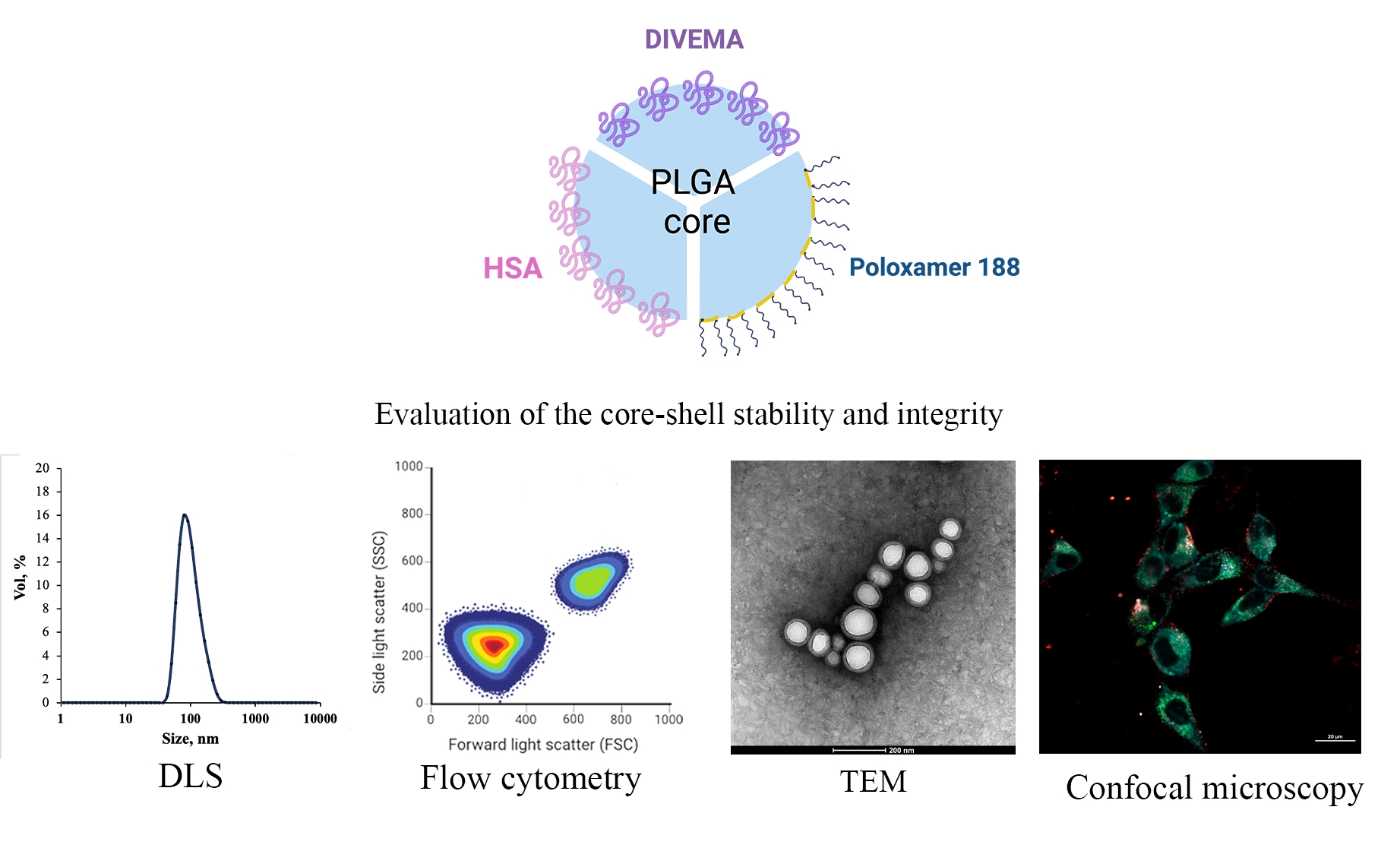

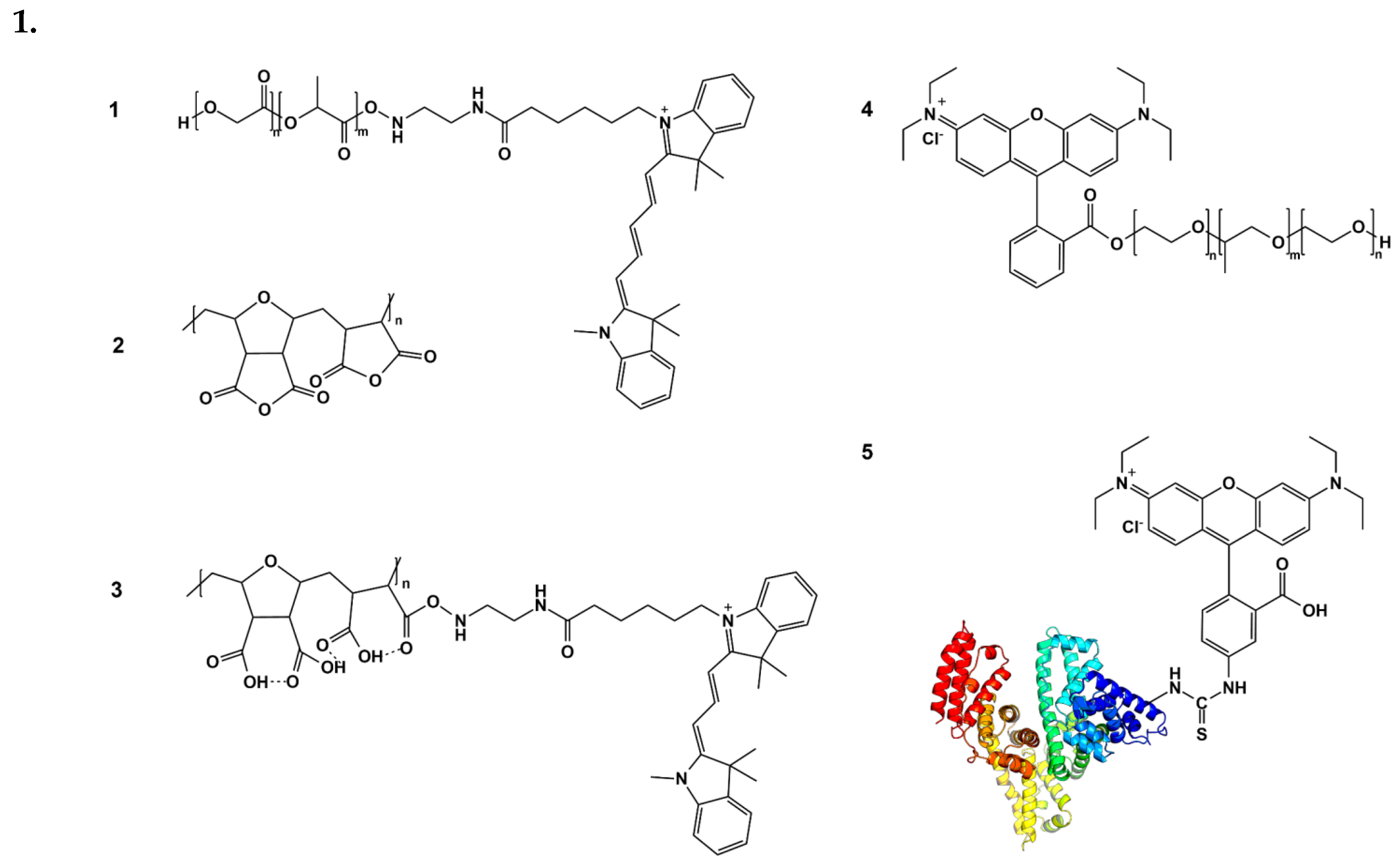

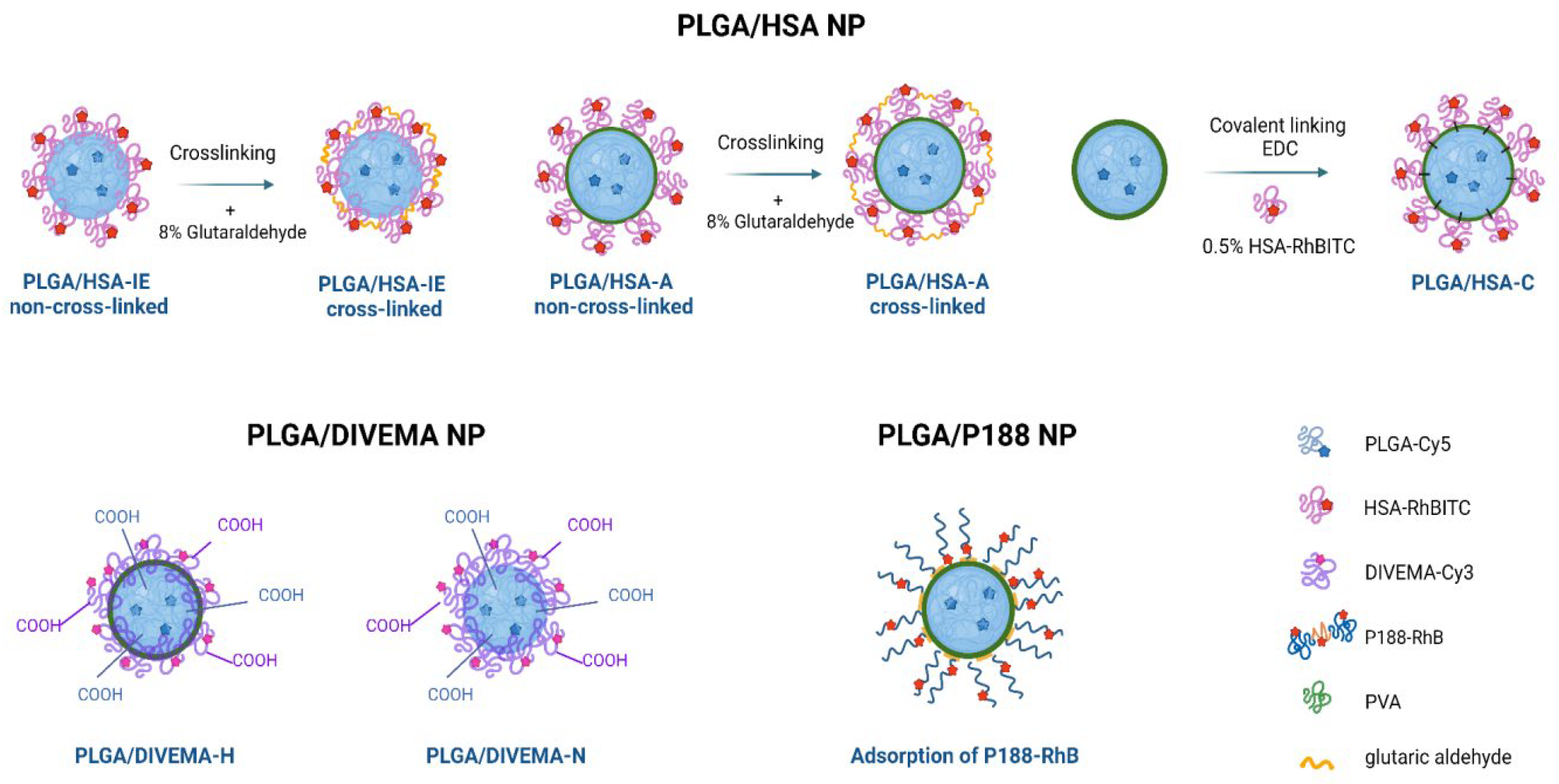

The objective of this study was to compare the properties of core-shell nanoparticles with a PLGA core and shells composed of different types of polymers; focusing on their structural integrity. Core PLGA nanoparticles were prepared by either the high-pressure homogenization — solvent evaporation technique or nanoprecipitation; using poloxamer 188 (P188); copolymer of divinyl ether with maleic anhydride (DIVEMA); and human serum albumin (HSA) as shell-forming polymers. The shells were formed through adsorption; interfacial embedding; or conjugation. For dual fluorescent labeling; the core and shell-forming polymers were conjugated with Cyanine5; Cyanine3; and rhodamine B. The nanoparticles had negative zeta potentials and sizes ranging from 100 to 250 nm (measured by DLS); depending on the shell structure and preparation technique. The core-shell structure was confirmed by TEM and fluorescence spectroscopy; with the appearance of FRET phenomena due to the donor-acceptor properties of the labels. All shells enhanced cellular uptake of the nanoparticles in Gl261 murine glioma cells. Integrity of the core-shell structure upon their incubation with cells was evidenced by intracellular colocalization of the fluorescent labels using Manders’ colocalization coefficients. This comprehensive approach may be useful for selection of the optimal preparation method already at the early stages of the core-shell nanoparticle development.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of Core-Shell PLGA Nanoparticle

2.2.1. Preparation of Dual-Labeled Nanoparticles with a PLGA Core and HSA Shell (PLGA-Cy5/HSA-RhBITC NP)

2.2.2. Preparation of Dual-Labeled Nanoparticles with a PLGA Core and DIVEMA Shell (PLGA-Cy5/DIVEMA-Cy3 NP)

2.2.3. Preparation of PLGA Nanoparticles Coated with Fluorescently Labeled Poloxamer 188

2.3. Characterization of Nanoparticles

2.4. Evaluation of Fluorescent Properties

2.5. Evaluation of Core-Shell Nanoparticle Stability by Physicochemical Methods

2.6. Cells

2.7. Investigation of Nanoparticle Internalization by Confocal Microscopy

2.8. Investigation of Nanoparticle Uptake by Flow Cytometry

2.9. Statistics

3. Results and Discussion

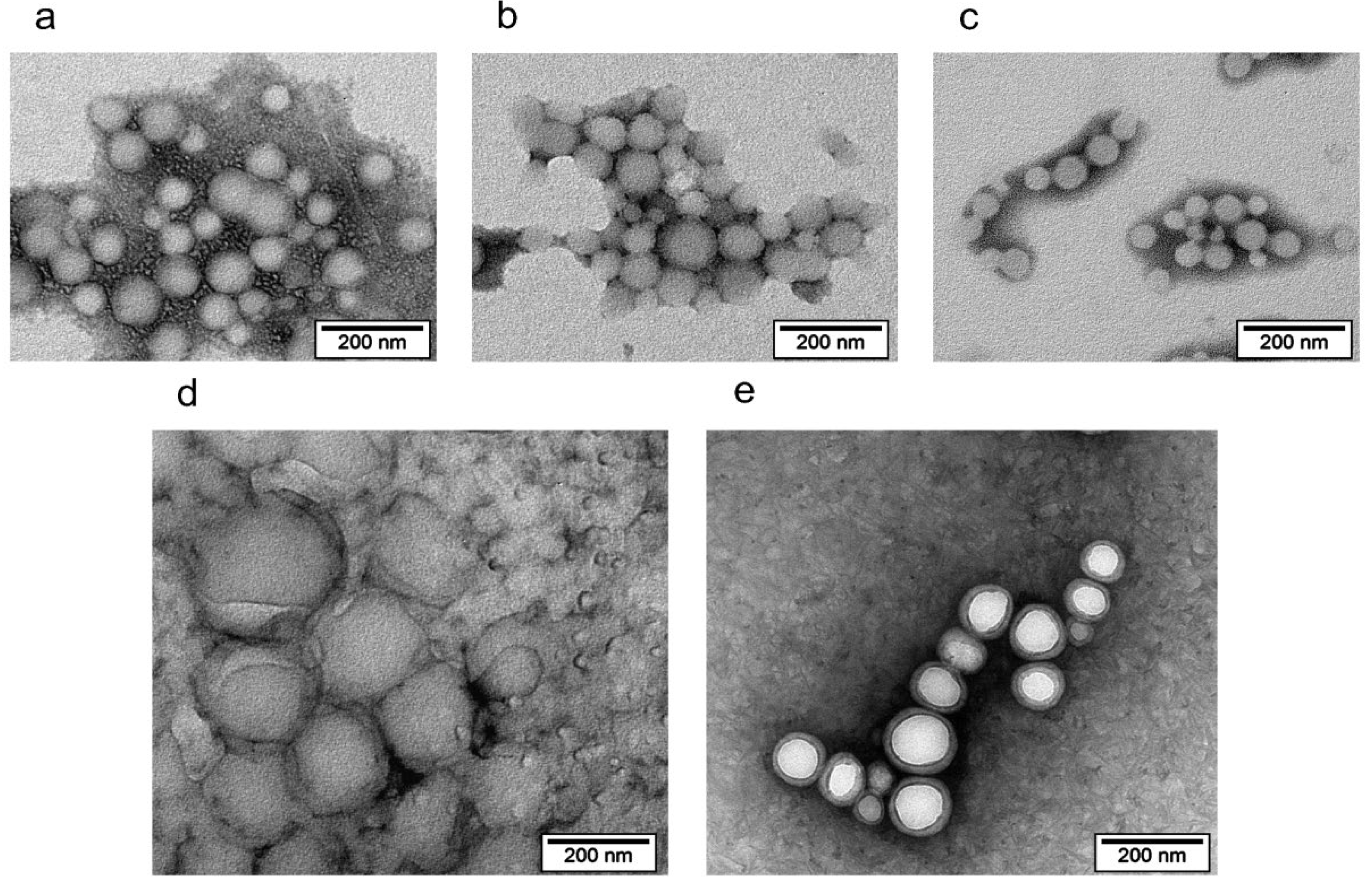

3.1. Core-Shell Nanoparticle Preparation and Characterization

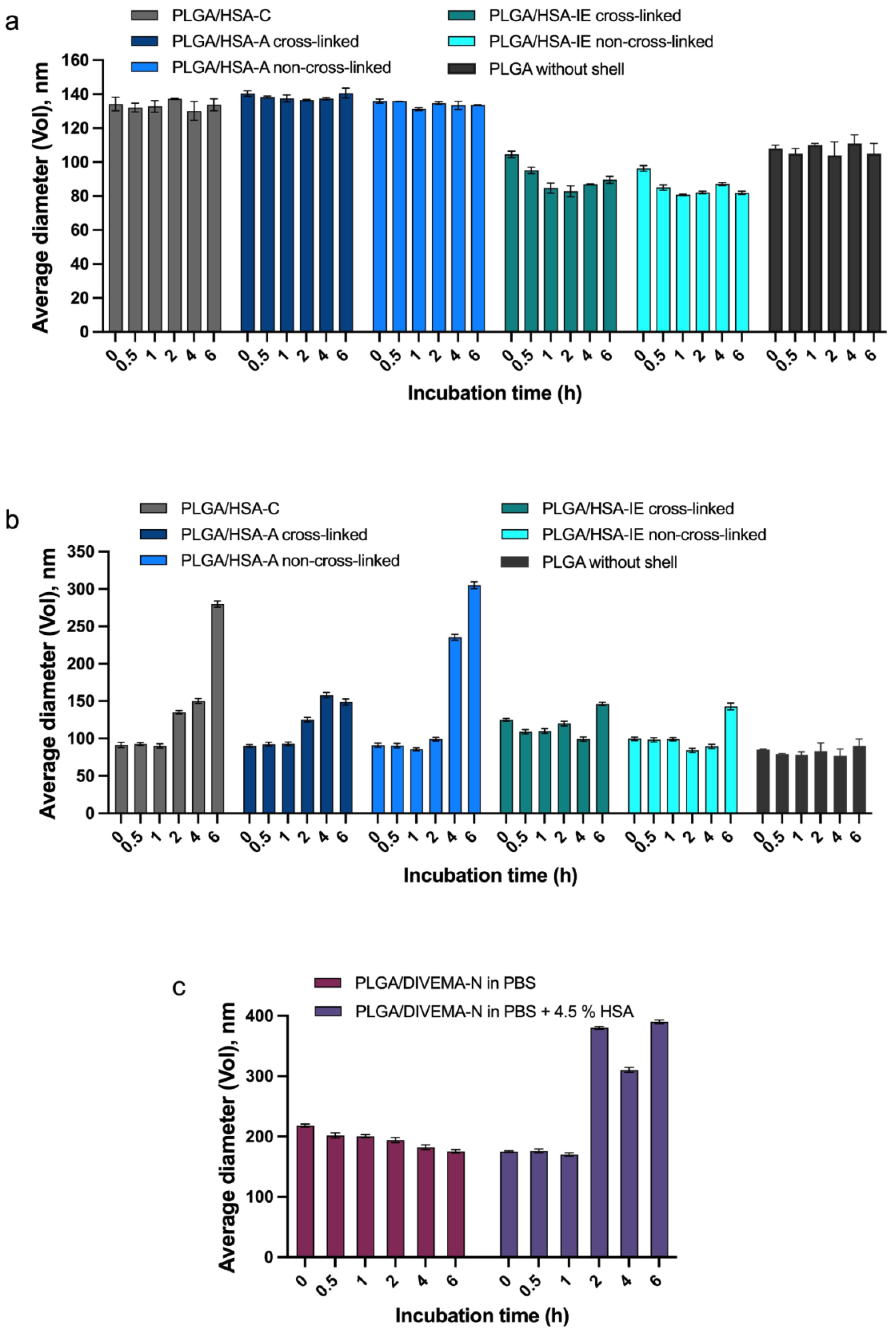

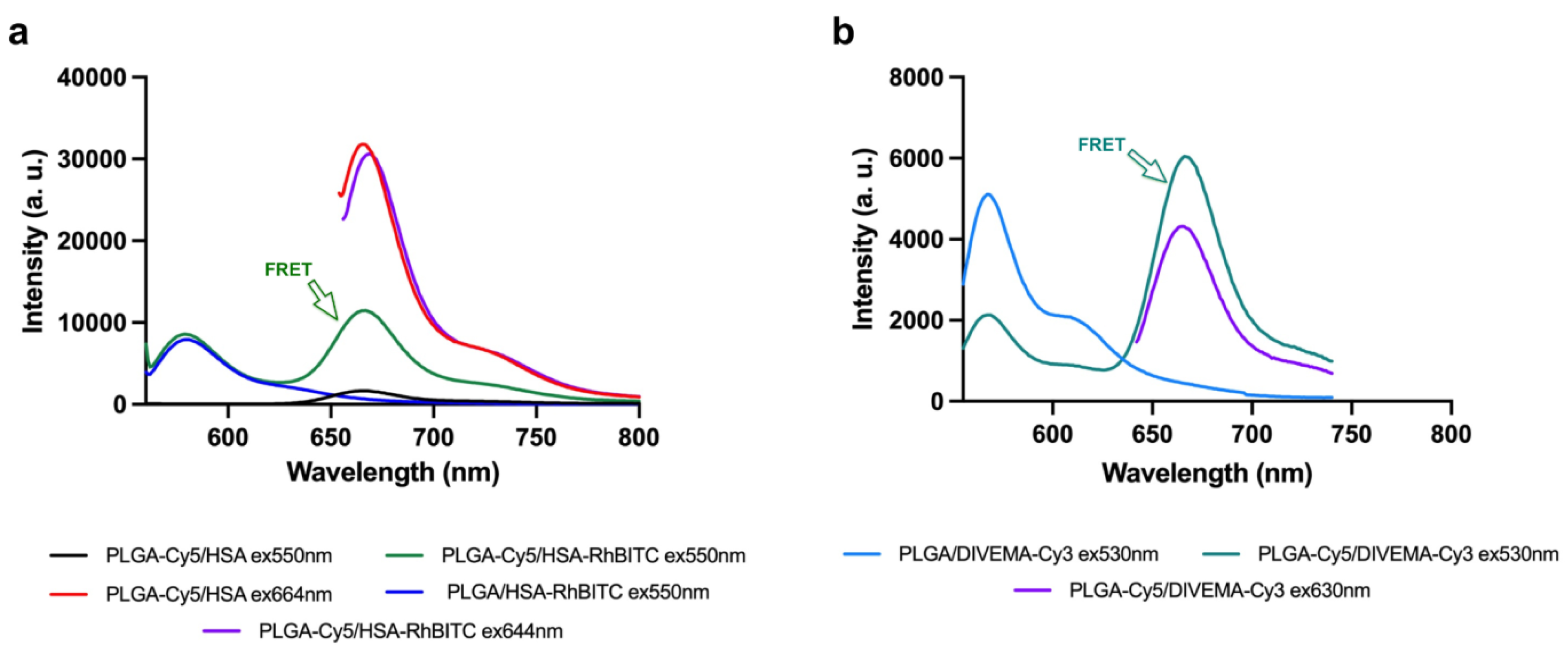

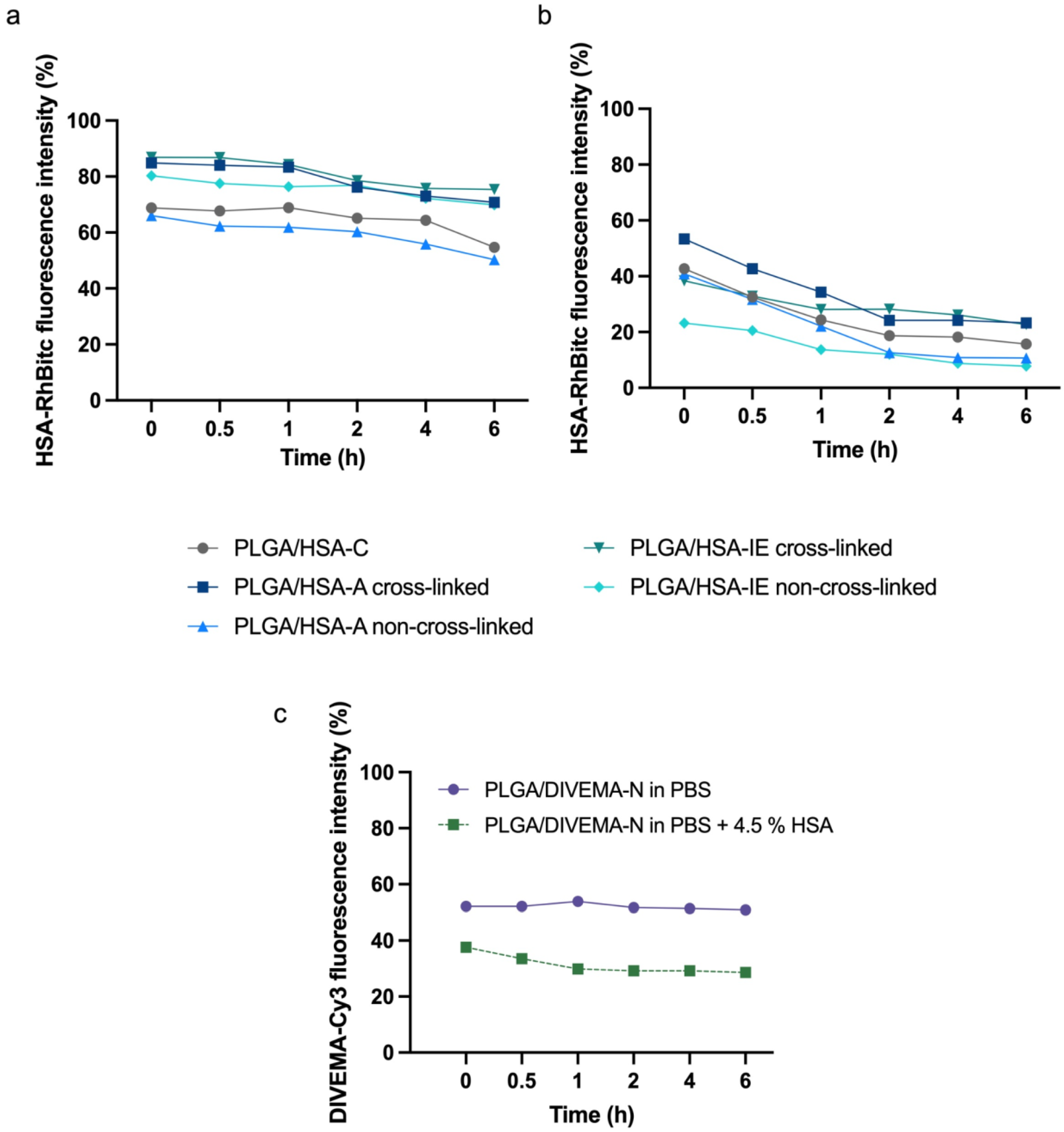

3.2. Evaluation of Integrity by Physicochemical Methods

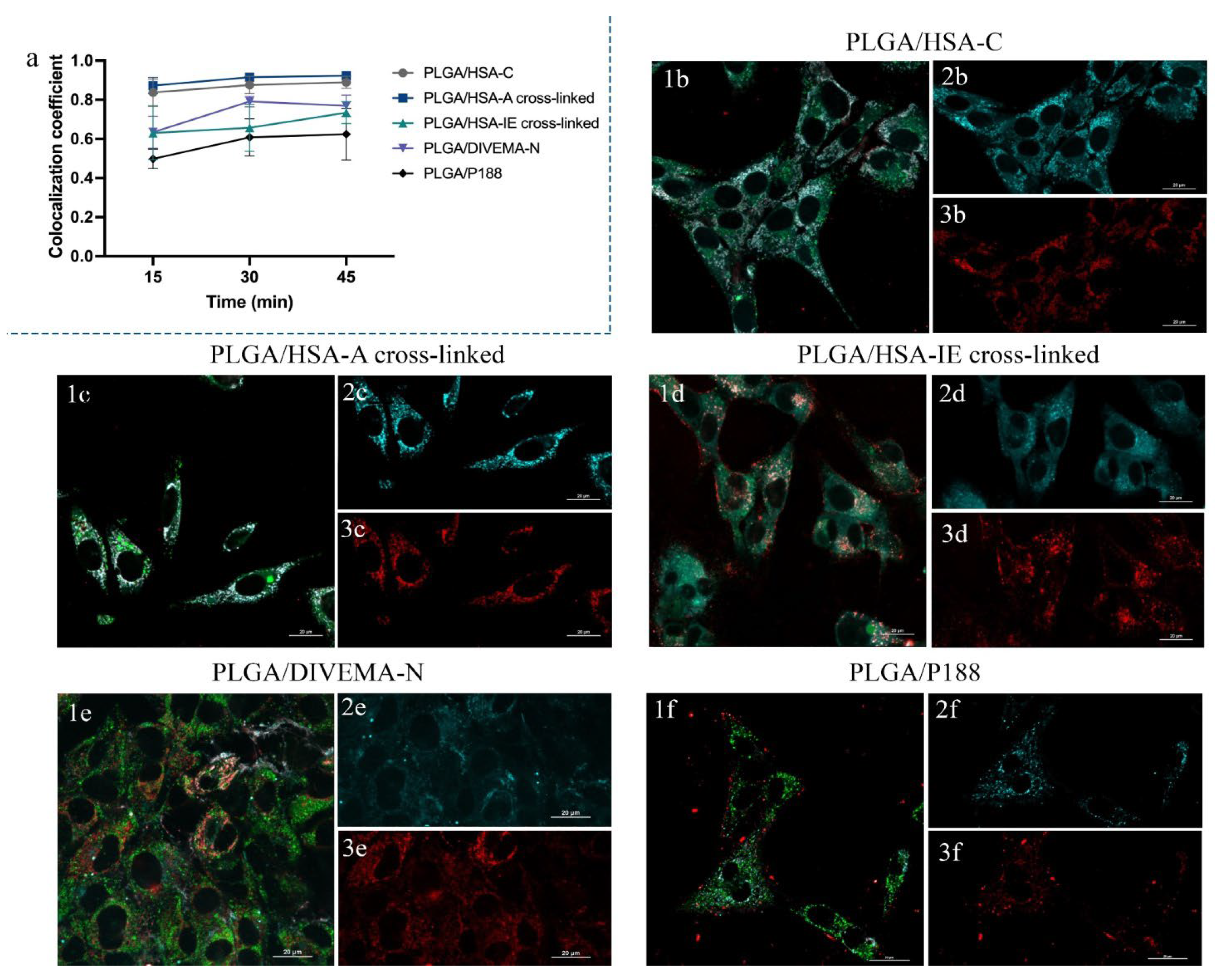

3.3. Investigation of the Integrity of the Core-Shell Nanoparticles Upon Internalization in Gl261 Cells by Confocal Microscopy

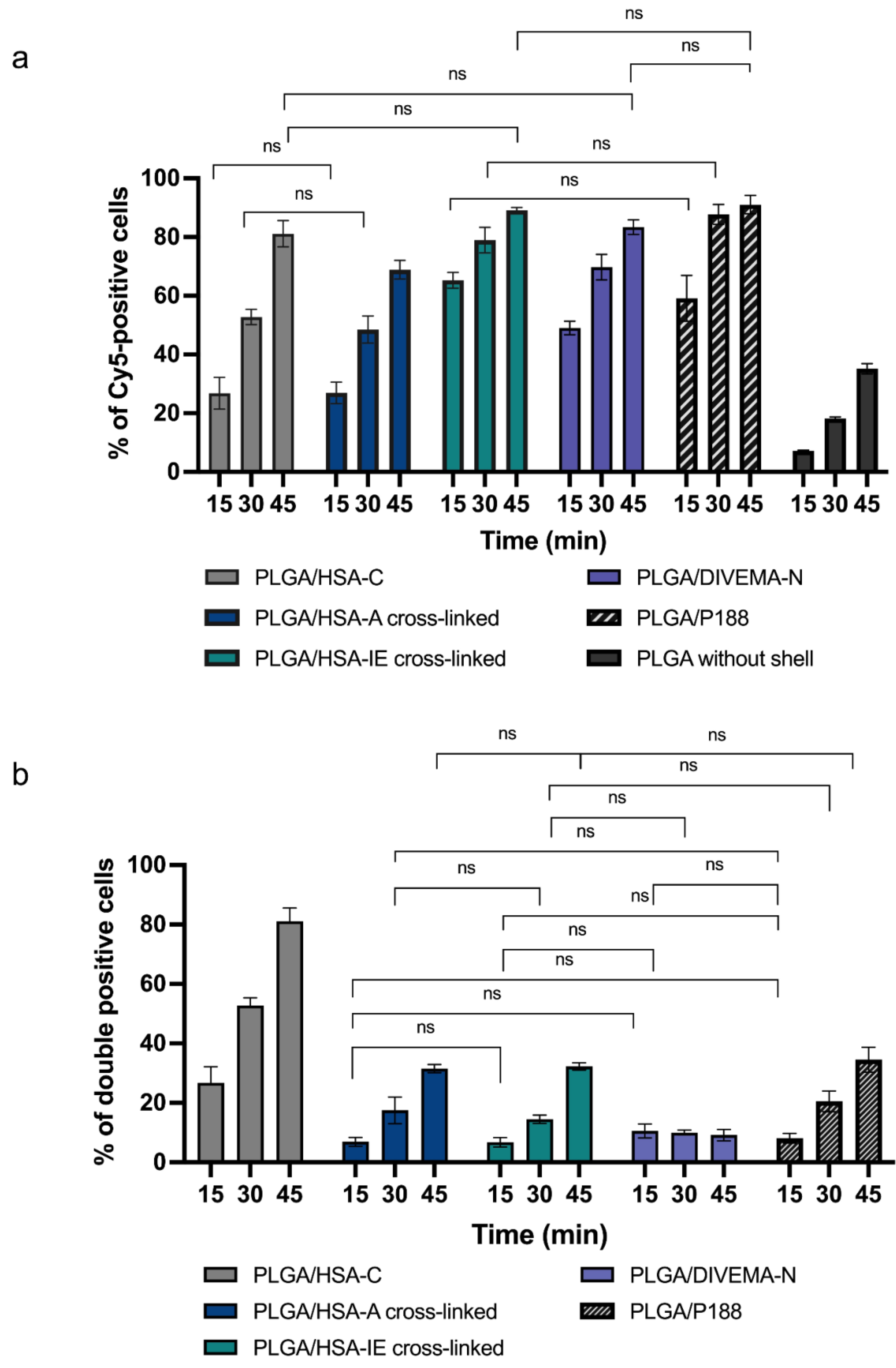

3.4. Investigation of the Dynamics of Nanoparticle Uptake by Gl261 Glioma Cells

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Champion, J.A.; Pustulka, S.M.; Ling, K.; Pish, S.L. Protein Nanoparticle Charge and Hydrophobicity Govern Protein Corona and Macrophage Uptake. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abed, N.; Couvreur, P. Nanocarriers for Antibiotics: A Promising Solution to Treat Intracellular Bacterial Infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2014, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustafson, H.H.; Holt-Casper, D.; Grainger, D.W.; Ghandehari, H. Nanoparticle Uptake: The Phagocyte Problem. Nano Today 2015, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venditto, V.J.; Szoka, F.C. Cancer Nanomedicines: So Many Papers and so Few Drugs! Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2013, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danhier, F. To Exploit the Tumor Microenvironment: Since the EPR Effect Fails in the Clinic, What Is the Future of Nanomedicine? Journal of Controlled Release 2016, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golombek, S.K.; May, J.N.; Theek, B.; Appold, L.; Drude, N.; Kiessling, F.; Lammers, T. Tumor Targeting via EPR: Strategies to Enhance Patient Responses. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2018, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.A.; Gadde, S.; Pfirschke, C.; Engblom, C.; Sprachman, M.M.; Kohler, R.H.; Yang, K.S.; Laughney, A.M.; Wojtkiewicz, G.; Kamaly, N.; et al. Predicting Therapeutic Nanomedicine Efficacy Using a Companion Magnetic Resonance Imaging Nanoparticle. Sci Transl Med 2015, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinovskaya, J.; Salami, R.; Valikhov, M.; Vadekhina, V.; Semyonkin, A.; Semkina, A.; Abakumov, M.; Harel, Y.; Levy, E.; Levin, T.; et al. Supermagnetic Human Serum Albumin (HSA) Nanoparticles and PLGA-Based Doxorubicin Nanoformulation: A Duet for Selective Nanotherapy. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiaie, S.H.; Salehi-Shadkami, H.; Sanaei, M.J.; Azizi, M.; Shokrollahi Barough, M.; Nasr, M.S.; Sheibani, M. Nano-Immunotherapy: Overcoming Delivery Challenge of Immune Checkpoint Therapy. J Nanobiotechnology 2023, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.M.; Yoo, Y.J.; Shin, H.S.; Kim, S.; Lee, S.N.; Lee, C.H.; Kim, H.; Kim, J.E.; Bae, Y.S.; Hong, J.H.; et al. A Nanoadjuvant That Dynamically Coordinates Innate Immune Stimuli Activation Enhances Cancer Immunotherapy and Reduces Immune Cell Exhaustion. Nat Nanotechnol 2023, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghidini, M.; Silva, S.G.; Evangelista, J.; Do Vale, M.L.C.; Farooqi, A.A.; Pinheiro, M. Nanomedicine for the Delivery of RNA in Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracey, S.R.; Smyth, P.; Barelle, C.J.; Scott, C.J. Development of next Generation Nanomedicine-Based Approaches for the Treatment of Cancer: We’ve Barely Scratched the Surface. Biochem Soc Trans 2021, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hare, J.I.; Lammers, T.; Ashford, M.B.; Puri, S.; Storm, G.; Barry, S.T. Challenges and Strategies in Anti-Cancer Nanomedicine Development: An Industry Perspective. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2017, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenjob, R.; Phakkeeree, T.; Crespy, D. Core-Shell Particles for Drug-Delivery, Bioimaging, Sensing, and Tissue Engineering. Biomater Sci 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R.; Mondal, K.; Panda, P.K.; Kaushik, A.; Abolhassani, R.; Ahuja, R.; Rubahn, H.G.; Mishra, Y.K. Core-Shell Nanostructures: Perspectives towards Drug Delivery Applications. J Mater Chem B 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhas, N.L.; Raval, N.J.; Kudarha, R.R.; Acharya, N.S.; Acharya, S.R. Core-Shell Nanoparticles as a Drug Delivery Platform for Tumor Targeting. In Inorganic Frameworks as Smart Nanomedicines; 2018. [CrossRef]

- Rescignano, N.; Kenny, J.M. Stimuli-Responsive Core-Shell Nanoparticles. Core-Shell Nanostructures for Drug Delivery and Theranostics: Challenges, Strategies and Prospects for Novel Carrier Systems 2018, 245–258. [CrossRef]

- Mehandole, A.; Walke, N.; Mahajan, S.; Aalhate, M.; Maji, I.; Gupta, U.; Mehra, N.K.; Singh, P.K. Core–Shell Type Lipidic and Polymeric Nanocapsules: The Transformative Multifaceted Delivery Systems. AAPS PharmSciTech 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezvantalab, S.; Drude, N.I.; Moraveji, M.K.; Güvener, N.; Koons, E.K.; Shi, Y.; Lammers, T.; Kiessling, F. PLGA-Based Nanoparticles in Cancer Treatment. Front Pharmacol 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dandamudi, M.; McLoughlin, P.; Behl, G.; Rani, S.; Coffey, L.; Chauhan, A.; Kent, D.; Fitzhenry, L. Chitosan-Coated Plga Nanoparticles Encapsulating Triamcinolone Acetonide as a Potential Candidate for Sustained Ocular Drug Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, P.; Wusiman, A.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Hu, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, D. Polyethylenimine-Coated PLGA Nanoparticles-Encapsulated Angelica Sinensis Polysaccharide as an Adjuvant to Enhance Immune Responses. Carbohydr Polym 2019, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bee, S.L.; Hamid, Z.A.A.; Mariatti, M.; Yahaya, B.H.; Lim, K.; Bee, S.T.; Sin, L.T. Approaches to Improve Therapeutic Efficacy of Biodegradable PLA/PLGA Microspheres: A Review. Polymer Reviews 2018, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gref, R.; Domb, A.; Quellec, P.; Blunk, T.; Müller, R.H.; Verbavatz, J.M.; Langer, R. The Controlled Intravenous Delivery of Drugs Using PEG-Coated Sterically Stabilized Nanospheres. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2012, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.M.; Patel, M.; Patel, R. PLGA Core-Shell Nano/Microparticle Delivery System for Biomedical Application. Polymers (Basel) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, F.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Du, B.; Huang, X.; Pang, L.; Zhou, Z. Silk Fibroin-Coated PLGA Dimpled Microspheres for Retarded Release of Simvastatin. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2017, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Liu, X.; Yuan, J.; Yang, S.; Li, Y.; Gao, Q. Synthesis and Characterization of Poly(Lactic Acid-Co-Glycolic Acid) Complex Microspheres as Drug Carriers. J Biomater Appl 2016, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Shi, X.; Gan, Z.; Wang, F. Modification of Porous PLGA Microspheres by Poly-L-Lysine for Use as Tissue Engineering Scaffolds. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2018, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorshkova, M.; Vanchugova, L.; Osipova, N.; Nikitin, A.; Kotova, J.; Kovalenko, E.; Ermolenko, Y.; Malinovskaya, J.; Kovshova, T.; Gelperina, S. Hybrid DIVEMA/PLGA Nanoparticles as the Potential Drug Delivery System 2024(submitted, preprint). [CrossRef]

- Kotova, J.O.; Osipova, N.S.; Malinovskaya, J.A.; Melnikov, P.A.; Gelperina, S.E. Properties of Core–Shell Nanoparticles Based on PLGA and Human Serum Albumin Prepared by Different Methods. Mendeleev Communications 2023, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beigulenko, D. V.; Semyonkin, A.S.; Malinovskaya, J.A.; Melnikov, P.A.; Medyankina, E.I.; Kovshova, T.S.; Ermolenko, Y. V.; Gelperina, S.E. Internalization of PLGA Nanoparticles Coated with Poloxamer 188 in Glioma Cells: A Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy Study. Mendeleev Communications 2023, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollenbach, L.; Buske, J.; Mäder, K.; Garidel, P. Poloxamer 188 as Surfactant in Biological Formulations – An Alternative for Polysorbate 20/80? Int J Pharm 2022, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabanov, A. V.; Alakhov, V.Y. Pluronic® Block Copolymers in Drug Delivery: From Micellar Nanocontainers to Biological Response Modifiers. Crit Rev Ther Drug Carrier Syst 2002, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereverzeva, E.; Treschalin, I.; Treschalin, M.; Arantseva, D.; Ermolenko, Y.; Kumskova, N.; Maksimenko, O.; Balabanyan, V.; Kreuter, J.; Gelperina, S. Toxicological Study of Doxorubicin-Loaded PLGA Nanoparticles for the Treatment of Glioblastoma. Int J Pharm 2019, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelperina, S.; Maksimenko, O.; Khalansky, A.; Vanchugova, L.; Shipulo, E.; Abbasova, K.; Berdiev, R.; Wohlfart, S.; Chepurnova, N.; Kreuter, J. Drug Delivery to the Brain Using Surfactant-Coated Poly(Lactide-Co-Glycolide) Nanoparticles: Influence of the Formulation Parameters. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 2010, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maksimenko, O.; Malinovskaya, J.; Shipulo, E.; Osipova, N.; Razzhivina, V.; Arantseva, D.; Yarovaya, O.; Mostovaya, U.; Khalansky, A.; Fedoseeva, V.; et al. Doxorubicin-Loaded PLGA Nanoparticles for the Chemotherapy of Glioblastoma: Towards the Pharmaceutical Development. Int J Pharm 2019, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hainsworth, J.D.; Forbes, J.T.; Grosh, W.W.; Greco, F.A. Phase I Study of MVE-2 Evaluating Toxicity and Biologic Response Modification Capability. Cancer Immunology Immunotherapy 1986, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regelson, W. The Biologic Activity of Polyanions: Past History and New Prospectives. Journal of Polymer Science: Polymer Symposia 1979, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breslow, D.S. Biologically Active Synthetic Polymers. Pure and Applied Chemistry 1976, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Liu, Y.; Teng, J.; Zhao, C.X. FRET Ratiometric Nanoprobes for Nanoparticle Monitoring. Biosensors (Basel) 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaeokhamloed, N.; Legeay, S.; Roger, E. FRET as the Tool for in Vivo Nanomedicine Tracking. Journal of Controlled Release 2022, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinovskaya, Y.; Melnikov, P.; Baklaushev, V.; Gabashvili, A.; Osipova, N.; Mantrov, S.; Ermolenko, Y.; Maksimenko, O.; Gorshkova, M.; Balabanyan, V.; et al. Delivery of Doxorubicin-Loaded PLGA Nanoparticles into U87 Human Glioblastoma Cells. Int J Pharm 2017, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhukova, V.; Osipova, N.; Semyonkin, A.; Malinovskaya, J.; Melnikov, P.; Valikhov, M.; Porozov, Y.; Solovev, Y.; Kuliaev, P.; Zhang, E.; et al. Fluorescently Labeled Plga Nanoparticles for Visualization in Vitro and in Vivo: The Importance of Dye Properties. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Sun, D.; Xu, P.; Li, S.; Cen, Y.; Li, Y.; Xu, Q.; Sun, Y.; Li, W.; Lin, Y.; et al. Stability of Bovine Serum Albumin Labelled by Rhodamine B Isothiocyanate. Biomedical Research (India) 2017, 28, ISSN: 0970938X.

- Langer, K.; Balthasar, S.; Vogel, V.; Dinauer, N.; Von Briesen, H.; Schubert, D. Optimization of the Preparation Process for Human Serum Albumin (HSA) Nanoparticles. Int J Pharm 2003, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoochehri, S.; Darvishi, B.; Kamalinia, G.; Amini, M.; Fallah, M.; Ostad, S.N.; Atyabi, F.; Dinarvand, R. Surface Modification of PLGA Nanoparticles via Human Serum Albumin Conjugation for Controlled Delivery of Docetaxel. DARU, Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2013, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volkova, I.F.; Gorshkova, M.Y.; Ivanov, P.E.; Stotskaya, L.L. New Scope for Synthesis of Divinyl Ether and Maleic Anhydride Copolymer with Narrow Molecular Mass Distribution. Polym Adv Technol 2002, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumskova, N.; Ermolenko, Y.; Osipova, N.; Semyonkin, A.; Kildeeva, N.; Gorshkova, M.; Kovalskii, A.; Kovshova, T.; Tarasov, V.; Kreuter, J.; et al. How Subtle Differences in Polymer Molecular Weight Affect Doxorubicin-Loaded PLGA Nanoparticles Degradation and Drug Release. J Microencapsul 2020, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashoka, A.H.; Aparin, I.O.; Reisch, A.; Klymchenko, A.S. Brightness of Fluorescent Organic Nanomaterials. Chem Soc Rev 2023, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, M.; Lindsey, J.S. Database of Absorption and Fluorescence Spectra of >300 Common Compounds for Use in PhotochemCAD. Photochem Photobiol 2018, 94, 290–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malicka, J.; Gryczynski, I.; Fang, J.; Lakowicz, J.R. Fluorescence Spectral Properties of Cyanine Dye-Labeled DNA Oligomers on Surfaces Coated with Silver Particles. Anal Biochem 2003, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, H. yu; Wang, R. qi; Sheng, W. jin; Zhen, Y. su The Development of Human Serum Albumin-Based Drugs and Relevant Fusion Proteins for Cancer Therapy. Int J Biol Macromol 2021, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, G.B. Synthesis and Antitumor Activity of “Pyran Copolymer. ” Journal of Macromolecular Science, Part C 1982, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nel, A.E.; Mädler, L.; Velegol, D.; Xia, T.; Hoek, E.M.V.; Somasundaran, P.; Klaessig, F.; Castranova, V.; Thompson, M. Understanding Biophysicochemical Interactions at the Nano-Bio Interface. Nat Mater 2009, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczyk, Z.; Nattich-Rak, M.; Dąbkowska, M.; Kujda-Kruk, M. Albumin Adsorption at Solid Substrates: A Quest for a Unified Approach. J Colloid Interface Sci 2018, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, H.; Nakhaei, E.; Kawano, T.; Murata, M.; Kishimura, A.; Mori, T.; Katayama, Y. Ligand-Mediated Coating of Liposomes with Human Serum Albumin. Langmuir 2018, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyun, H.; Park, J.; Willis, K.; Park, J.E.; Lyle, L.T.; Lee, W.; Yeo, Y. Surface Modification of Polymer Nanoparticles with Native Albumin for Enhancing Drug Delivery to Solid Tumors. Biomaterials 2018, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Li, Y.; Gao, Y.; Wei, N.; Zhao, X.; Wang, C.; Li, Y.; Xiu, X.; Cui, J. Direct Comparison of Two Albumin-Based Paclitaxel-Loaded Nanoparticle Formulations: Is the Crosslinked Version More Advantageous? Int J Pharm 2014, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorshkova, M.; Lebedeva, T.; Chervina, L.; Stotskaya, L. Kinetics of the Hydrolysis of Divinyl Ether-Maleic Anhydride Copolymer in Water and Stability of the Copolymer in Acetone. Polymer Science, Series A 1995, 37, 1003–1007. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Chen, Q.; Li, J.; Huang, Y.; Yin, Q. Effects of Poly(Vinyl Alcohol) and Poly(Acrylic Acid) on Interfacial Properties and Stability of Compound Droplets. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, P.K.; Desai, P.S.; Li, J.; Larson, R.G. PH and Salt Effects on the Associative Phase Separation of Oppositely Charged Polyelectrolytes. Polymers (Basel) 2014, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovshova, T.; Osipova, N.; Alekseeva, A.; Malinovskaya, J.; Belov, A.; Budko, A.; Pavlova, G.; Maksimenko, O.; Nagpal, S.; Braner, S.; et al. Exploring the Interplay between Drug Release and Targeting of Lipid-like Polymer Nanoparticles Loaded with Doxorubicin. Molecules 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liang, Y.; Fei, S.; He, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, T.; Tang, X. Formulation and Pharmacokinetics of HSA-Core and PLGA-Shell Nanoparticles for Delivering Gemcitabine. AAPS PharmSciTech 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippov, S.K.; Khusnutdinov, R.; Murmiliuk, A.; Inam, W.; Zakharova, L.Y.; Zhang, H.; Khutoryanskiy, V. V. Dynamic Light Scattering and Transmission Electron Microscopy in Drug Delivery: A Roadmap for Correct Characterization of Nanoparticles and Interpretation of Results. Mater Horiz 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inyang, E.; Kuriakose, A.E.; Chen, B.; Nguyen, K.T.; Cho, M. Engineering Delivery of Nonbiologics Using Poly(Lactic- Co-Glycolic Acid) Nanoparticles for Repair of Disrupted Brain Endothelium. ACS Omega 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Tian, L.; Gao, M.; Xu, H.; Zhang, C.; Lv, L.; Zhang, J.; Wang, C.; Tian, Y.; Ma, X. Promising Galactose-Decorated Biodegradable Poloxamer 188-Plga Diblock Copolymer Nanoparticles of Resibufogenin for Enhancing Liver Cancer Therapy. Drug Deliv 2017, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ural, M.S.; Joseph, J.M.; Wien, F.; Li, X.; Tran, M.A.; Taverna, M.; Smadja, C.; Gref, R. A Comprehensive Investigation of the Interactions of Human Serum Albumin with Polymeric and Hybrid Nanoparticles. Drug Deliv Transl Res 2024, 14, 2188–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietrich, A.; Buschmann, V.; Müller, C.; Sauer, M. Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) and Competing Processes in Donor-Acceptor Substituted DNA Strands: A Comparative Study of Ensemble and Single-Molecule Data. Reviews in Molecular Biotechnology 2002, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinigaglia, G.; Magro, M.; Miotto, G.; Cardillo, S.; Agostinelli, E.; Zboril, R.; Bidollari, E.; Vianello, F. Catalytically Active Bovine Serum Amine Oxidase Bound to Fluorescent and Magnetically Drivable Nanoparticles. Int J Nanomedicine 2012, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Huang, C.; Emery, B.P.; Sedgwick, A.C.; Bull, S.D.; He, X.P.; Tian, H.; Yoon, J.; Sessler, J.L.; James, T.D. Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET)-Based Small-Molecule Sensors and Imaging Agents. Chem Soc Rev 2020, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Gaytan, B.L.; Fay, F.; Hak, S.; Alaarg, A.; Fayad, Z.A.; Pérez-Medina, C.; Mulder, W.J.M.; Zhao, Y. Real-Time Monitoring of Nanoparticle Formation by FRET Imaging. Angewandte Chemie - International Edition 2017, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayes, J.B.; Rawlins, D.A. Adsorption Characteristics of Certain Polyoxyethylene-Polyoxypropylene Block Co-Polymers on Polystyrene Latex. Colloid and Polymer Science Kolloid-Zeitschrift & Zeitschrift für Polymere 1979, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santander-Ortega, M.J.; Csaba, N.; Alonso, M.J.; Ortega-Vinuesa, J.L.; Bastos-González, D. Stability and Physicochemical Characteristics of PLGA, PLGA:Poloxamer and PLGA:Poloxamine Blend Nanoparticles: A Comparative Study. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp 2007, 296, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, K.W.; Kamocka, M.M.; McDonald, J.H. A Practical Guide to Evaluating Colocalization in Biological Microscopy. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2011, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mettlen, M.; Chen, P.H.; Srinivasan, S.; Danuser, G.; Schmid, S.L. Regulation of Clathrin-Mediated Endocytosis. Annu Rev Biochem 2018, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, M.; Ben-Josef, E.; Robb, R.; Vedaie, M.; Seum, S.; Thirumoorthy, K.; Palanichamy, K.; Harbrecht, M.; Chakravarti, A.; Williams, T.M. Caveolae-Mediated Endocytosis Is Critical for Albumin Cellular Uptake and Response to Albumin-Bound Chemotherapy. Cancer Res 2017, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvati, A.; Nelissen, I.; Haase, A.; Åberg, C.; Moya, S.; Jacobs, A.; Alnasser, F.; Bewersdorff, T.; Deville, S.; Luch, A.; et al. Quantitative Measurement of Nanoparticle Uptake by Flow Cytometry Illustrated by an Interlaboratory Comparison of the Uptake of Labelled Polystyrene Nanoparticles. NanoImpact 2018, 9, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method of shell formation (method of nanoparticle preparation*) | Nanoparticle size and size distribution, nm | Zeta potential, mV |

Shell content, mg/mg PLGA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean diameter | PDI | Volume size distribution | |||

| PLGA-Cy5/HSA-RhBITC NP | |||||

|

Conjugation (PLGA/HSA-C) |

153 ± 2 | 0.201 ± 0.017 | 147 (100%) | -7.0 ± 1.2 | 0.48 |

| Adsorption, cross-linked (PLGA/HSA-A cross-linked) |

148 ± 2 | 0.183 ± 0.018 | 143 (100%) | -7.6 ± 0.8 | 0.11 |

| Adsorption, non-cross-linked (PLGA/HSA-A non-cross-linked) |

135 ± 1 | 0.118 ± 0.014 | 133 (100%) | -6.2 ± 2.7 | 0.11 |

| Interfacial embedding, cross-linked (PLGA/HSA-IE cross-linked) |

103 ± 3 | 0.138 ± 0.014 | 92 (100%) | -26.3 ± 0.7 | 0.50 |

| Interfacial embedding, non-cross-linked (PLGA/HSA-IE non-cross-linked) |

90 ± 1 | 0.056 ± 0.022 | 83 (100%) | -31.9 ± 2.7 | 0.52 |

| PLGA without shell *** | 116 ± 2 | 0.098 ± 0.015 | 108 (100%) | -20.9 ± 1.1 | - |

| PLGA-Cy5/DIVEMA-Cy3 NP | |||||

| Interfacial embedding (PLGA/DIVEMA-H) |

264 ± 4 | 0.225 ± 0.009 | 341 (94.2%) 5118 (5.8%) |

-34.9 ± 0.1 | 0.10 |

| PLGA without shell ** | 178 ± 24 | 0.230 ± 0.050 | 290 (100%) | -20.3 ± 1.7 | - |

| Interfacial embedding (nanoprecipitation) (PLGA/DIVEMA-N) |

180 ± 21 | 0.274 ± 0.007 | 284 (100%) | -51.3 ± 1.4 | 0.47 |

| NP without shell (nanoprecipitation) ** | 130 ± 15 | 0.070 ± 0.015 | 170 (100%) | -18.5±3.5 | - |

| PLGA-Cy5/P188-RhB | |||||

| Adsorption of P188-RhB | 97 ± 1 | 0.100 ± 0.007 | 85 (100%) | -21.8 ± 0.7 | 0.017 |

| Adsorption of P188 | 110 ± 2 | 0.16 ± 0.01 | 97 (100%) | -23.5 ± 1.1 | 0.006 |

| PLGA without shell *** | 100 ± 2 | 0.078 ± 0.015 | 100 (100%) | -20.9 ± 1.1 | - |

| Sample | Dye content, µg/ml | Dye to polymer ratio, µg/mg | Quantum Yield | Brightness,M-1 cm-1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLGA-Cy5/HSA-RhBITC | RhBITC | Cy5 | RhBITC | Cy5 | RhBITC | Cy5 | RhBITC | Cy5 | |

| PLGA/HSA-С | 4.80 | 1.62 | 3.93 | 0.64 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 1.03x108 | 3.61x107 | |

| PLGA/HSA-A cross-linked | 3.62 | 1.81 | 12.07 | 0.68 | 0.11 | 0.18 | 3.78x107 | 6.70x107 | |

| PLGA/HSA-A non-cross-linked | 4.86 | 2.53 | 16.20 | 0.88 | 0.15 | 0.23 | 3.41x107 | 6.46x107 | |

| PLGA/HSA-IE cross-linked | 3.11 | 1.31 | 0.98 | 0.78 | 0.19 | 0.31 | 1.42x108 | 1.46x107 | |

| PLGA/HSA-IE non-cross-linked | 2.64 | 1.80 | 0.80 | 0.85 | 0.21 | 0.29 | 9.53x107 | 1.01x107 | |

| PLGA-Cy5/DIVEMA-Cy3 | Cy3 | Cy5 | Cy3 | Cy5 | Cy3 | Cy5 | Cy3 | Cy5 | |

| 4.12 | 2.36 | 11.4 | 2.03 | 0.12 | 0.21 | 1.66x108 | 2.56x108 | ||

| PLGA-Cy5/P188-RhB | RhB | Cy5 | RhB | Cy5 | RhB | Cy5 | RhB | Cy5 | |

| 4.26 | 4.65 | 44.8 | 0.83 | 0.63 | 0.37 | 3.77x107 | 4.19x107 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).