1. Introduction

Water scarcity in agriculture is projected to impact over 80% of the world’s arable land by 2050, threatening the livelihoods of approximately 10 billion people[

1,

2] This issue stems comprehends the overexploitation of freshwater resources, exacerbating unsustainable water use. The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, which has some of the scarcest freshwater resources globally [

3] faces significant challenges. To address this, water reuse strategies, such as using treated wastewater (TWW), are crucial for replenishing agricultural water supplies and ensuring high-quality water [

3]. This approach aligns with Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 6.3, which aims to increase recycling and safe reuse of wastewater, recover nutrients and organic matter, reduce water pollution, and enhance resource use efficiency.

Jordan, the second-most water-scarce country globally and one of the aridest in the Middle East [

4] utilizes approximately 85% of its TWW for productive purposes, mainly in agriculture [

5]. For instance, 45 Mm³·yr⁻¹ of TWW is used in restricted irrigation to produce fodder crops and fruit trees, though these projects often face low-cost recovery and questionable long-term financial sustainability [

6]. Similarly, Palestine experiences severe water scarcity, with TWW representing a significant potential source for agriculture. The West Bank could produce over 50,000 m³·d⁻¹ of TWW, sufficient to irrigate over 2,000 hectares (20 km

2), but currently, TWW reuse is limited to around 300 hectares [

7].

However, inappropriate irrigation management tailored to TWW can lead to imbalances in water quality and quantity. TWW, being a double source of water and nutrients, may have a detrimental effect on soil’s physical and chemical qualities, resulting in soil salinization, reduced production, and root uptake. Additionally, the presence of hazardous metals and pathogens may pose environmental risks to the agroecosystem[8, 9]

Salinity impacts nutrient absorption (e.g., nitrate, phosphorus) by roots and affects soil infiltration and aeration. Soil pH, influenced by structure, irrigation, and depth, alters nutrient availability and organic matter mineralization. Organic matter content and soil aggregates influence water retention, infiltration, drainage, and soil fertility. TWW fertilization boosts soil microbial activity and organic matter (OM) mineralization, increasing potassium (K) levels with surface drip systems [

10].

Strategic irrigation, such as frequent watering and pre-planting irrigation, reduces salinity risk and water stress. These methods can be adapted for TWW irrigation. Modeling TWW consumption is recommended but still depends on traditional irrigation plans designed for conventional water and is often based on the sole estimation of the evapotranspiration demand. However, misleading threshold values from conventional irrigation can lead to inadequate TWW practices 11].

Overall, traditional irrigation plans can be based on the soil water depletion ratio, where irrigation is scheduled when the soil water deficit in the effective root zone exceeds a certain threshold of total available water (TAW) [

12]. However, this approach does not consider water quality, which is closely linked to water quantity estimation. Therefore, it is essential to use models that support the implementation of schedules incorporating water quality parameters to better balance water demand and supply, enhance plant growth, control water fluxes, and manage salt transport in the vadose zone and beyond the root zone.

Models that predict the effects of TWW irrigation management on soil are crucial, but they must be combined with field data to validate irrigation practices. For instance, some models estimate crop yield response to irrigation water by treating soil as a reservoir, where once fully saturated, the saturated hydraulic conductivity is reached, triggering the drainage process [

13]. These models allow for the inclusion of TWW quality parameters. To propose effective TWW irrigation management, it is essential to consider critical parameters such as the quality of the applied TWW, soil water, salinity levels, and the presence of pathogens. These factors help preserve soil physical characteristics, reduce soil salination, and maintain good yield production [

14].

Combining field data with modeling enhances decision-making by introducing and testing alternative scenarios for proper TWW irrigation scheduling[

11]. Modeling tools aid in selecting optimal irrigation strategies for TWW reuse, understanding complex reactions beforehand, and adjusting farm management practices to minimize negative effects. Scenarios focused on reducing salt accumulation in the root zone and reducing the leaching of rapidly leachable nutrients or pollutants are particularly effective.

The Safe Irrigation Management (SIM) model, a one-dimensional, daily water balance model, was designed to balance simplicity, robustness, and accuracy. It simulates correct irrigation management scenarios and schedules adapted for TWW reuse by accounting for water quality parameters and soil properties. and combining water and salt conservation equations. The SIM model compares conventional and TWW irrigation management scenarios, providing insights into improving current practices for TWW irrigation [

14].

This study aims to develop irrigation plans for TWW reuse in two case studies from Jordan and Palestine that have been proactive in transferring irrigation management responsibilities to water users' associations[

15]. It focuses on optimizing nutrient uptake while minimizing long-term adverse impacts on crops and soils. Specifically, the research seeks to: i) harmonize field-collected data and calibrate the SIM model in Beit-Dajan (Palestine) and Al Ramtha (Jordan) for alfalfa, a perennial crop, and citrus, a permanent crop, respectively; ii) simulate multiple irrigation strategies and scenarios with TWW using the SIM model, accounting for water quantity and quality inputs; iii) identify the best/no harm irrigation management practices tailored to TWW. Based on these objectives, two scenarios were identified to run the SIM model: 1) FARMOD, which refers to model calibration based on farmer planning, and 2) ON DEMAND, which refers to the irrigation schedule suggested by SIM. A sensitivity analysis was also performed to assess the most sensitive parameters, requiring monitoring for long-term reuse. Additionally, a hypothetical scenario (HYP) was set up to evaluate whether the outputs generated by the SIM model using current inputs still reflect proper TWW irrigation management. This scenario assumes optimal water and soil conditions for crop growth under good TWW irrigation quality, aiming to predict better TWW management in the Jordan and Palestine contexts. Jordan and Palestine have been proactive in transferring irrigation management responsibilities to water users' associations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area 1: Alfalfa In Jordan

The experiment was conducted from December 2020 to October 2021 at the National Agricultural Research Center (NARC)'s Al Ramtha Experimental Station for TWW Studies in Jordan, which receives an average annual rainfall of approximately 275 mm. Four alternative irrigation techniques were tested: sprinkler, surface drip, subsurface drip, and surface irrigation. The plots were completely randomized, with irrigation systems assigned to 5x5 m randomized experimental plots with 3 m spacing between plots, for a total of 16 plots (

Figure 1). Alfalfa seeds (Medicago sativa L.) were sown in April 2021 at a rate of 70 kg/ha, and harvested four times during the experiment on May 18, June 6, June 28, and August 3, 2021.

Domestically, TWW effluent from the Al Ramtha Secondary Wastewater Treatment Plant (RWTP) was used for irrigation. The RWTP is connected to the experimental site via a main HDPE irrigation line, with water filtered through sand and disc filters before useFour pop-up sprinklers with discharge rates of 0.1 m³·h⁻¹ were installed, one at each corner of the plots. The subsurface drip irrigation system had dripper lines placed 25 cm deep, with 50 cm between adjacent lines and drippers spaced 30 cm apart. Non-leakage pressure-compensated drippers with discharge rates of 2 L·h⁻¹ were used. The surface drip irrigation system was similar, except the dripper lines were positioned on the soil surface.

The irrigation events for each technique were calculated assuming that 30% of the available water was drained. TWW irrigation was applied using the Penman-Monteith equation, with an anticipated annual irrigation volume of 680 mm. This volume was enhanced by 60%, 70%, 85%, and 90% for surface, sprinkler, drip, and subsurface irrigation systems, respectively, to account for system efficiency. Overall, a yearly irrigation volume of 1044 mm was provided, with sprinkler irrigation delivering 969.7 mm, drip irrigation 798.6 mm, and subsurface irrigation 754.1 mm. Each system was connected by a separate pipe directly from the treatment station.

The soil was classified as clay, with an average clay content of more than 50%, low salinity (1.0 dS·m⁻¹), and a slightly alkaline pH of 8.4. The soil potassium content exceeded 700 mg·L⁻¹. Phosphorus and nitrogen levels were 20 mg·L⁻¹ and 0.09%, respectively, according to NARC results [

16]. Nitrogen values ranged between 0.05% and 0.15%, while phosphorus was in the medium range (20–25 mg·L⁻¹) [

16]. The organic matter content was 1.25%.

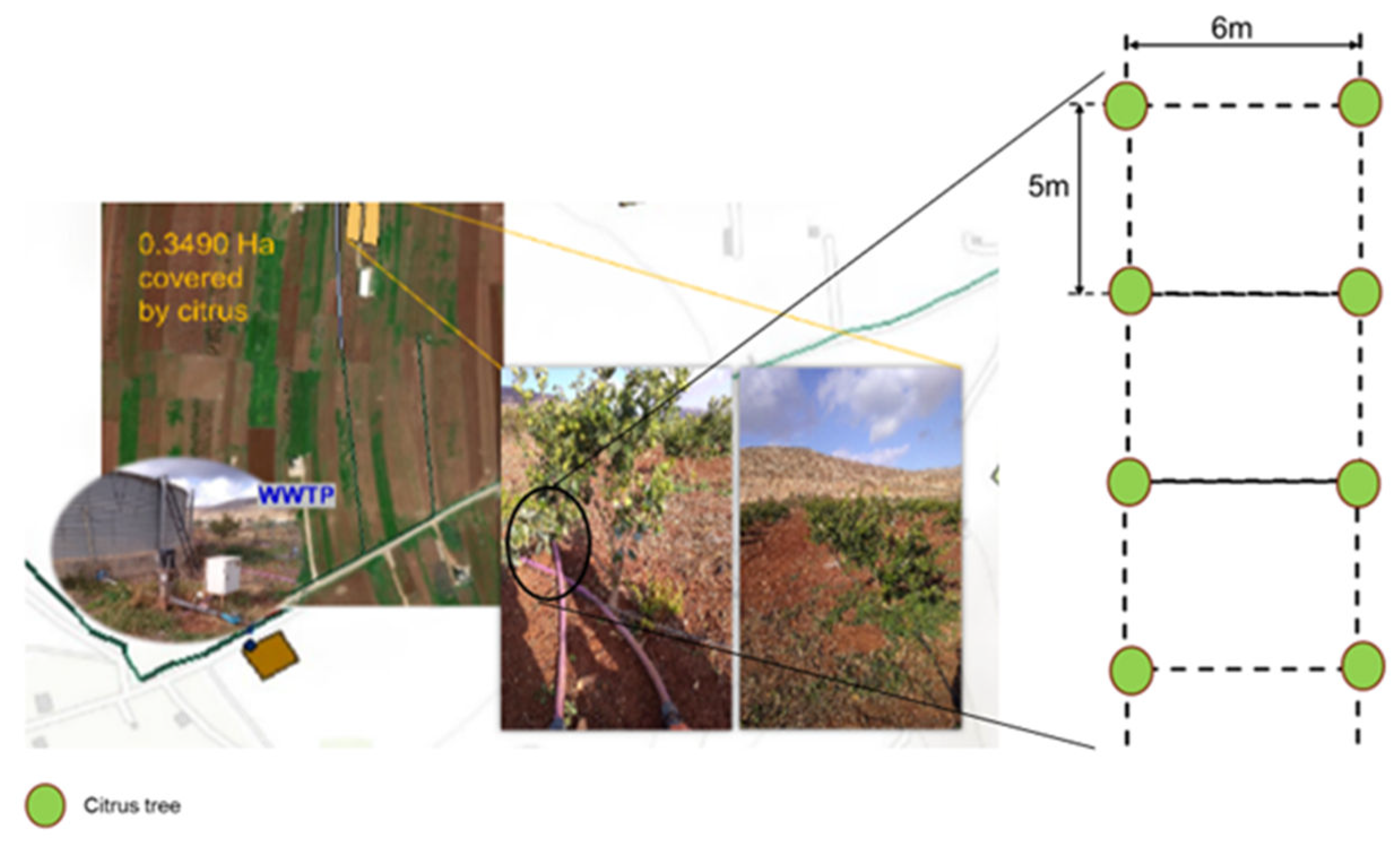

2.2. Study Area 2: Citrus Palestine

Beit Dajan is situated 10.74 km east of the Nablus, receiving an average annual rainfall of 343.3 mm. The experimental field, measuring 0.35 ha, is planted with 6 years old citrus trees and irrigated using a drip irrigation system with tertiary TWW (

Figure 2). The soil in Beit Dajan is classified as Terra Rossa (Xerochrepts, Rhodoxeralfs), according to USDA classification, characterized by a reddish-brown color and a fine clay loam texture with 35% clay, 36.5% silt, and 28.5% sand. The soil solution’s electrical conductivity (ECe) is 0.9 dS·m⁻¹, with phosphorus at 12.3 ppm and total nitrogen at 0.45%.TWW irrigation is scheduled at 750 mm/year. The citrus orchards are drip-irrigated with one drip line per tree row, emitters spaced 0.25 m apart, and a discharge of 2 Lh-1, with irrigation occurring every 3 days. The input data pertains to the citrus experiment carried out during the 2020–2021 season. TWW irrigation volumes for citrus crop supplied daily by the farmers (including frequency, interval, amount of TWW), were measured throughout the irrigation season. Four measurement campaigns were conducted to assess the effects of TWW irrigation on soil and citrus. Soil samples were collected on June 7 and 28, July 18, and August 28, 2021, to determine volumetric water content, soil solution electrical conductivity, and nitrate and ammonium concentrations. Chemical analyses were performed on soil samples collected from below the tree and between two trees at the beginning of the irrigation season. Additionally, three effluent samples per month were collected from the Beit Dajan treatment plant outlet from March 1 to August 30, 2021. Physical and chemical analyses of the effluent were performed according to Standard Methods of Water and Wastewater Analysis [

17]. The average chemical parameters from the three collected samples (1 March–August 2021) were as follows: NH₄⁺ was 32 mg·L⁻¹; NO3 was 0.768 mg·L⁻¹; PO₄³⁻ was 22.9 mg·L⁻¹; and K was 270 mg·L⁻¹. The average water electrical conductivity, ECw, was equal to 1.9 dS·m⁻¹.

2.3. SIM Model Set Up.

The SIM model was used to retrieve TWW irrigation practices scheduled by the farmers and identify the optimal scenario to minimize soil salinity and yield reduction. This one-dimensional, daily water and salt balance model simulates soil water and salt behavior under specific crop, soil, and irrigation management conditions, considering water quality, quantity, and climatic conditions. The SIM model is a tool designed to forecast these processes and identify crucial elements related to the soil and TWW quality.

It is used to extrapolate the outcomes of various irrigation and fertigation management schemes, enabling the examination of alternative management strategy scenarios in terms of their effects on yield, soil qualities, and potential environmental problems. The SIM model considers water and soil quality factors, bacterial migration, and infection risk using a one-dimensional daily water and nutrient balance model and the single crop coefficient method (single Kc). It has four compartments dealing with: crop water demand and irrigation scheduling, salinity management, bacterial movement and risk assessment, and nutrient management [

18].

Two scenarios are accounted for: 1) FARMOD refers to the model results calibrated based on field variables measured at the end of the crop season, such as N and P uptake and yield. The simulation was able to replicate soil and crop responses during the irrigation season (15 November 2020 to 15 November 2021); 2) ON-DEMAND refers to the irrigation scheduling suggested by the model based on two assumptions: ECe not exceeding 2.5 dS·m⁻¹ and improved yield production compared to the farmer’s practice.

For alfalfa, the two scenarios were reproduced using the SIM model to replicate soil and nutrient behavior under farmer irrigation management (FARMOD) and model scheduling (ON-DEMAND). Similarly, for citrus, the effects of TWW were compared under both farmer (FARMOD) and model (ON-DEMAND) scheduling in two case studies.

2.4. Sensitivity Analysis of Two FARMOD And ON-DEMAND Scenarios

Sensitivity analysis (SA) measures how uncertainties in input variables affect output variables, enhancing model prediction. This study uses SA to assess the robustness, or “sensitivity” of the findings to changes in parameters, identifying levels beyond which results change dramatically. SA prioritizes knowledge improvement by minimizing assessment parameter uncertainties, allowing for phenomenon-related judgments[

19]. Sensitivity studies identify which input parameters most impact model outcomes, enabling the elimination of irrelevant factors and guiding future research to minimize parameter uncertainties and improve model accuracy[

20].

Based on SIM model scenarios, SA was utilized to design optimal TWW irrigation management methods. SA findings also indicated the main characteristics affecting soil quality when using TWW irrigation. The variance-based global sensitivity analysis technique ‘Sobol’ was applied. This approach assesses the relative effect of a parameter and its interaction with other variables on model output variance using variance decomposition.

The first-order sensitivity index (FSI) and total sensitivity index (TSI) are calculated using this approach. The FSI represents each parameter’s sensitivity to the model output, whereas the TSI is the sum of a parameter’s FSI plus the sensitivity of the parameter’s interaction with other factors impacting the model output. If no parameters interact, the total of all parameters’ FSIs equals 1. The FSI and TSI parameters range from 0 to 1 [

21].

The Sobol method was applied to the model outputs to identify the most sensitive elements requiring monitoring.

The FSI was calculated as follows [

21]:

where:

Vi is the model output variance in response to variation of the input variable; V is the total variance of the model output.

The TSI was calculated as follows [

21]:

where

j and

m are the jth and the mth model input variable;

Vi is the model output variance in response to the interaction between the input variables

i and

j; V is the total variance of the model output.

After performing the sensitivity analysis and observing that ECe and nitrogen are the most sensitive parameters, the SIM model was rerun to generate results specifically for ECe and nitrogen. This was done under a hypothetical scenario (HYP) which refers to the optimal water and soil inputs.

2.5. Hypothetical Scenario for Alfalfa and Citrus

Monitoring the long-term effects of TWW is crucial not only for the quality of the water supplied but also for the quality of the soil, which plays an essential role in maintaining sustainable reuse and agriculture.

Previous simulations (FARMOD, ON-DEMAND) were set up using soil and water quality parameters derived from the TWW irrigation management practices. These practices were carried out over a long period without any prior assessment of the initial soil condition before reuse. Consequently, the FARMOD and ON-DEMAND simulations were based on soil and water quality parameters that were lower than the standards. Since the accuracy of the model depends on the quality of the input data, the likelihood of a better scenario can be tested.

A hypothetical scenario was created using improved water and soil quality parameters, assuming optimal initial soil quality (good tilth). This aspect is relevant because water quality can be controlled and improved by modernizing the treatment plants and conducting regular weekly water sample analyses. However, the main challenge remains the soil quality, where TWW dynamics are more complex under continuous irrigation, as water and nutrients are supplied simultaneously with each irrigation event.

To account for accurate soil quality data, well-managed case studies from the literature were considered, involving the same soil types and similar TWW quality parameters Accordingly, two scenarios were performed: 1) Vertisol and TWW secondary treatment as input parameters for Alfalfa; 2) Terra Rossa and TWW tertiary treatment for Citrus.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Case Study 1: Alfalfa in Jordan

3.1.1. Yield And Nutrient Efficiency for Alfalfa

The SIM model simulated water inflows and outflows based on a bucket model concept. The comparison between the FARMOD and the ON-DEMAND scenario showed comparable results in terms of yield and nutrient efficiency, as presented in

Table 1 N and P uptake observations were calculated as the product of yield and the percentage of leaf N and P measured, respectively. FARMER (observations only) and FARMOD produced very similar results, indicating that the SIM model provided an accurate simulation and served as a calibration test. Once the model was calibrated, the input soil and water quality variables were fixed, like the scenario used. Proper irrigation scheduling within the model requires setting the ECe value to 2.5 dS·m⁻¹ to achieve optimal FARMER yield conditions. However, in the ON-DEMAND scenario, even with a similar farmer yield, it was evident that applying an appropriate irrigation schedule improved root N and P uptake. This strongly influenced qualitative and quantitative crop parameters, leading to yield improvement. For instance, the yield obtained under the drip FARMER scenario was 14,200 kg/ha compared to 16,410 kg/ha in the ON-DEMAND scenario.

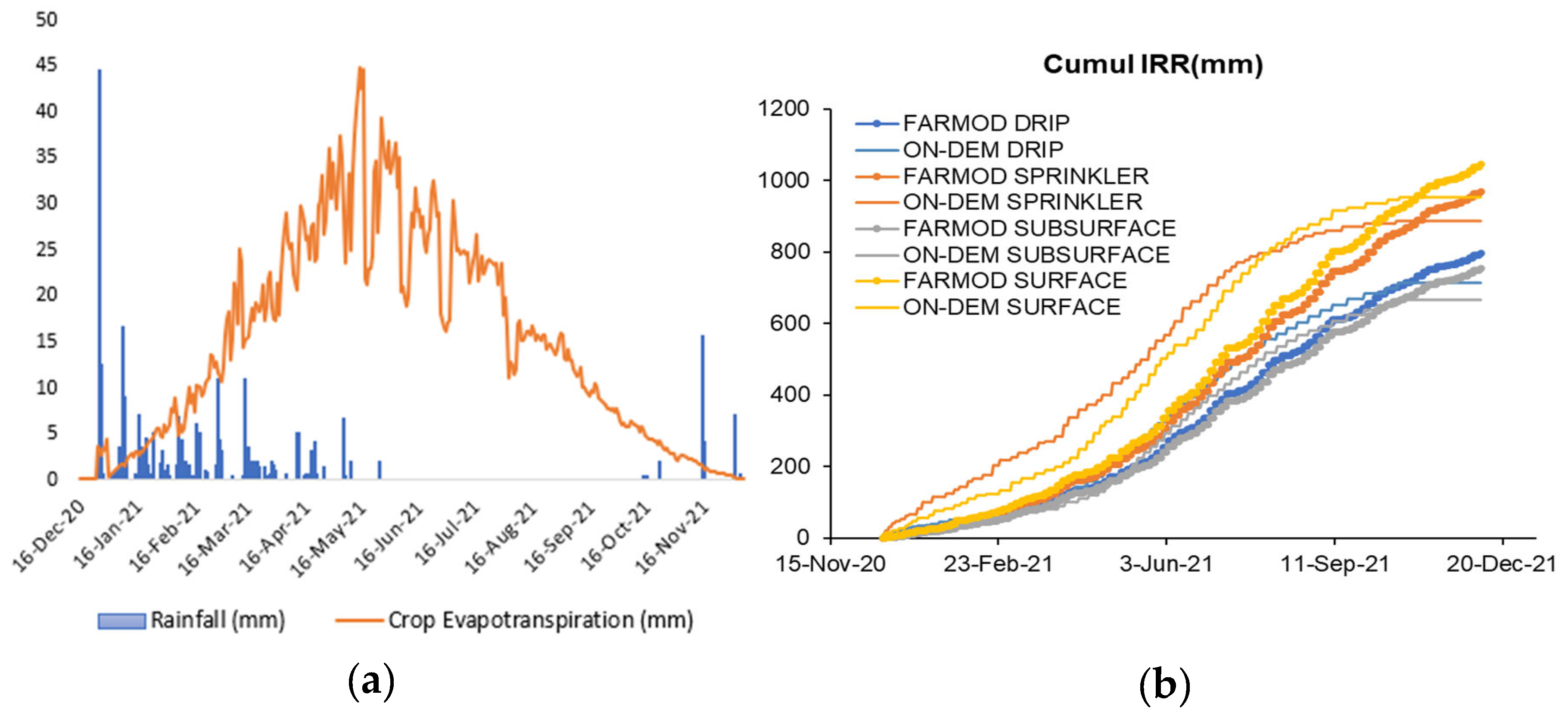

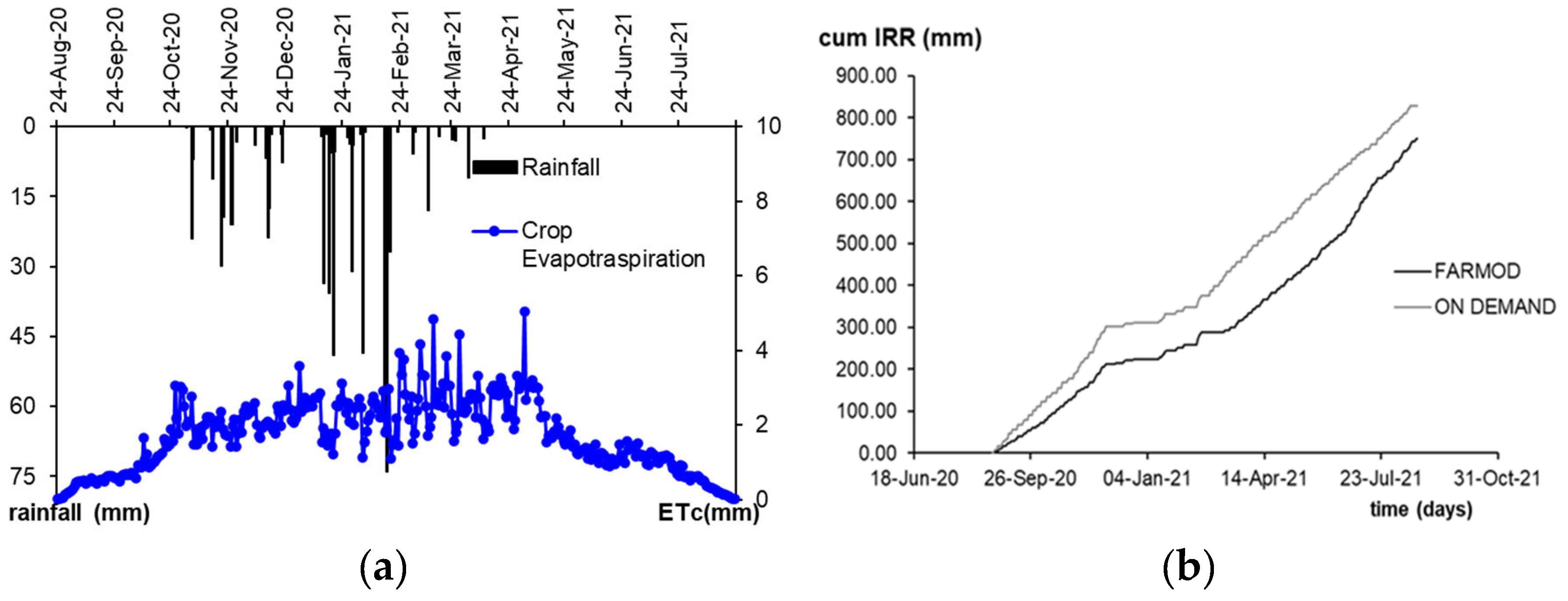

3.1.2. Irrigation Management for Alfalfa

The curve of rainfall and evapotranspiration shows that at the beginning of the season, rainfall is high while evapotranspiration is low. During in the peak period, evapotranspiration reaches its highest point where rainfall is at its minimum. Throughout the alfalfa growing season, the trend of evapotranspiration decreases due to the four-cutting effect (

Figure 3a).

The model output, in terms of cumulative irrigation demand for almost all growing seasons, was analyzed. The curve of the FARMOD scenario is higher than the ON-DEMAND trend across the four irrigation systems (

Figure 3b) For example, the farmer applied 800 mm with the drip system compared to 715 mm with the ON-DEMAND scenario that suggests a better irrigation distribution, leading to water savings. In addition, the farmer's irrigation behavior shows an increasing trend at the end of the season, justified by the fact that farmers irrigate twice per week. Conversely, the ON-DEMAND curve tends to stabilize at the end of the season, indicating low to zero irrigation events due to the simulation length set up. This stabilization occurs because of low crop evapotranspiration and rainfall events during the last two months (

Figure 3b).

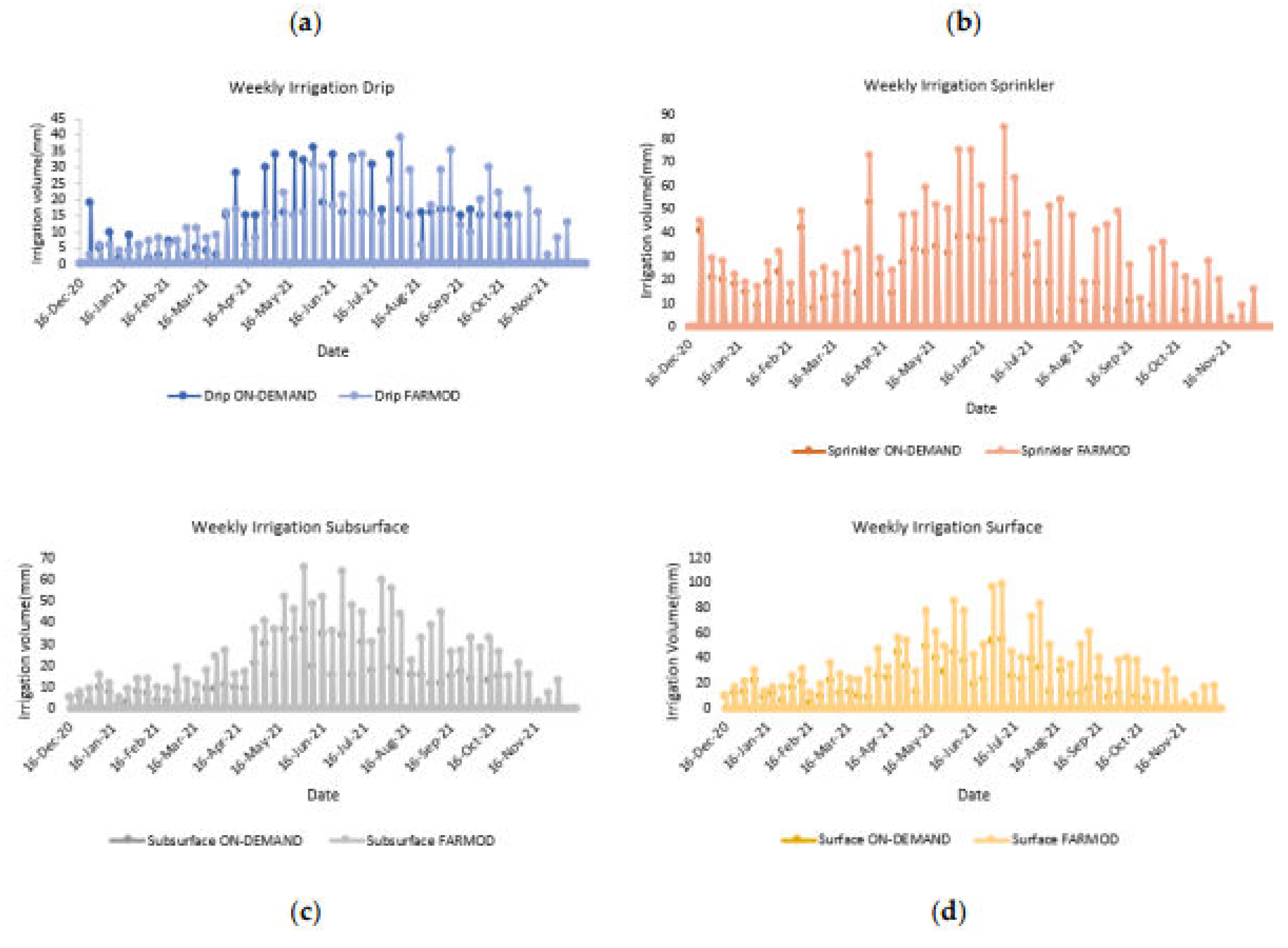

3.1.2. Irrigation Management for Alfalfa

Regarding irrigation scheduling, the adopted FARMOD strategy for the ongoing proposed strategies for TWW reuse continues to rely on the traditional modeling of irrigation plans intended for conventional water sources. In this case study, TWW irrigation volumes are mainly based on the demand for evapotranspiration, meaning that the water delivered to the crops is calculated as the difference between seasonal evapotranspiration and precipitation deficit. Weekly irrigation volumes applied by the farmer and those simulated by the model are depicted in (

Figure 4) highlighting the significant role of irrigation trends on yield response.

Some differences are evident due to the weekly strategy used for the amount of water applied. In the FARMER scenario, irrigation was performed biweekly at a fixed rate. In contrast, the on-demand scenario modulated the frequency and amount of water applied to maintain an ECe of 2.5 dS·m⁻¹ or less, assuming this salinity control would not compromise alfalfa yield. The higher irrigation rates suggested by the SIM model, particularly for the drip system (

Figure 4a) are due to the high irrigation frequency needed to keep the root zone wetter. This ensures no-harm TWW irrigation and maintains an adequate ECe threshold, preventing salt accumulation. Consequently, drained water moves salt below the root zone, reducing salt-induced crop stress.

The ON-DEMAND scenario also suggested additional water application during periods of high evapotranspiration demand, especially in the absence of rainfall, to control soil salinity levels and to reduce water stress. The differences between the four irrigation systems are noticeable, with irrigation volumes differentiated in the SIM model based on the actual water required to restore evapotranspiration and reduce potential salt accumulation. However, the SIM model cannot distinguish irrigation volumes per method applied. This differentiation was made outside the model, accounting for distribution uniformity, i.e., 65, 70, 85, and 90% for surface, sprinkler, surface drip, and subsurface drip irrigation systems respectively. In this regard, another similar study assessed the impact of four irrigation systems -surface-drip, surface (flood), sprinkler, and subsurface-drip-, on alfalfa under a treated wastewater irrigation regime, finding that subsurface-drip irrigation might be considered an efficient irrigation method [

22].

However good potential could arise from combining drip and sprinkler systems for forage cultivation, as the sprinkler method can induce microclimatic conditions within the alfalfa canopy, potentially improving its growth.

One study, although related to and experiment carried out under conventional water irrigation, showed that using sprinkler irrigation system affected water distribution and led to increased alfalfa water productivity [

23]. Additionally, further results related to alfalfa irrigated with TWW using sprinkler system demonstrated that this system met optimal water and nutrient requirements while respecting irrigation water standards [

24].

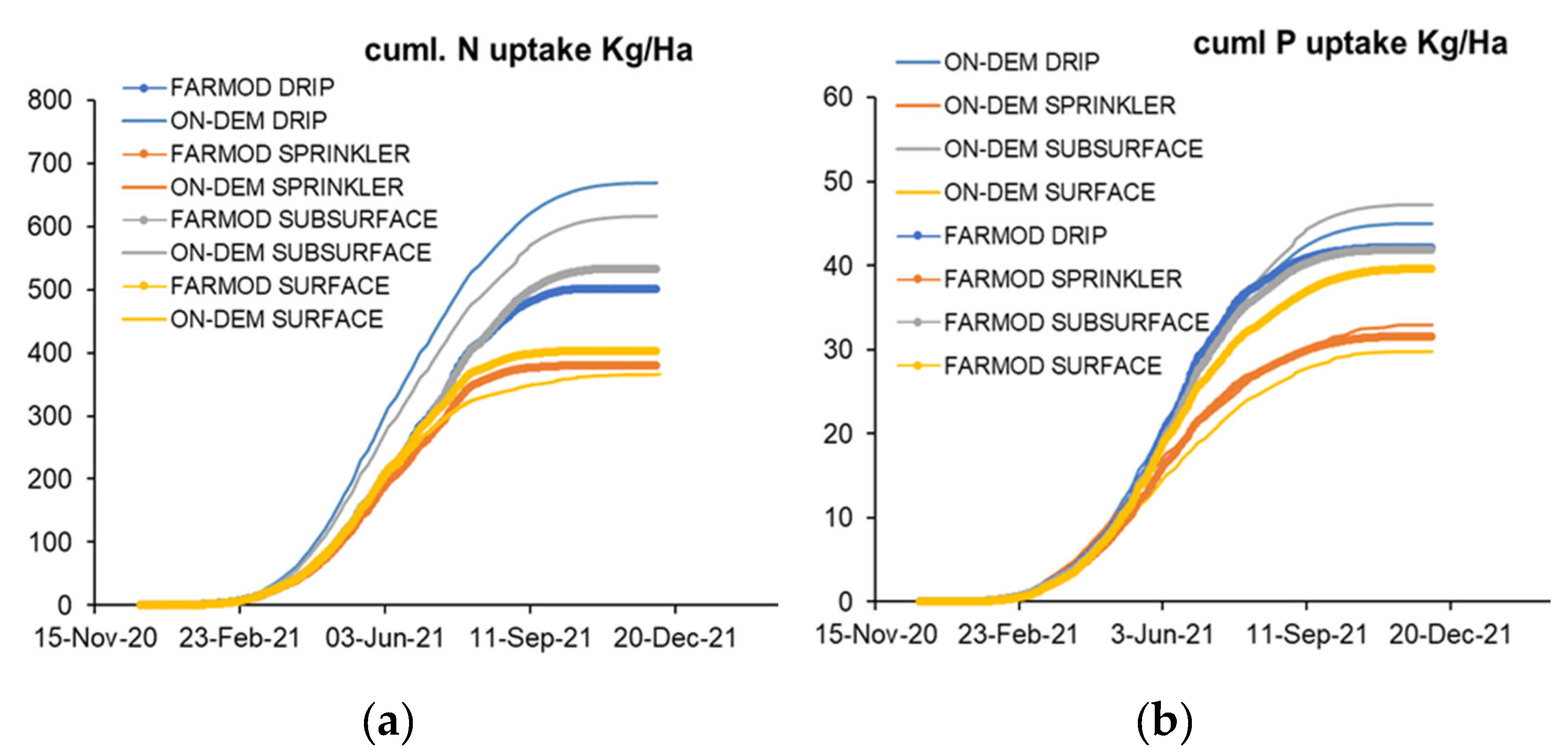

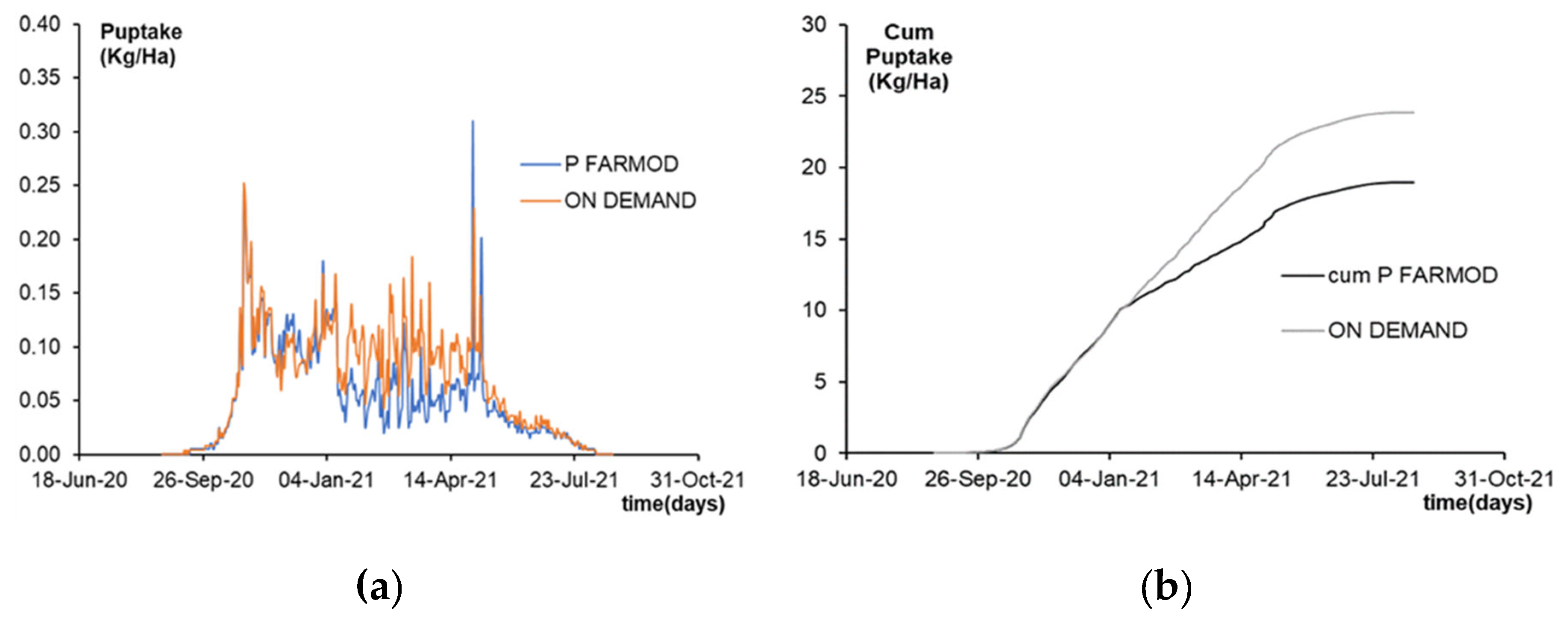

3.1.3. Nutrient Management for Alfalfa

Figure 5 shows the cumulative nutrient uptake in terms of P and N for the FARMOD and ON-DEMAND scenarios. It is relevant that for nitrogen, the ON-DEMAND scenario showed higher values (

Figure 5a), this could be explained by the model suggesting a higher amount of water be applied, meaning a higher amount of nitrogen is supplied, leading to better absorption. On the other hand, the difference between scenarios was not too significant in terms of P (

Figure 5b), indicating that a slight increase in the volume of water doesn’t influence P uptake.

Literature reviews indicate that most crops cannot remove the total amount of P applied with secondary TWW. The additional P accumulates in the upper soil layers, depending on soil properties such as pH. The soil’s pH value also limits the mobility of P and influences the timing of its application [

25].

3.1.4. Salinity And E. Coli Management for Alfalfa

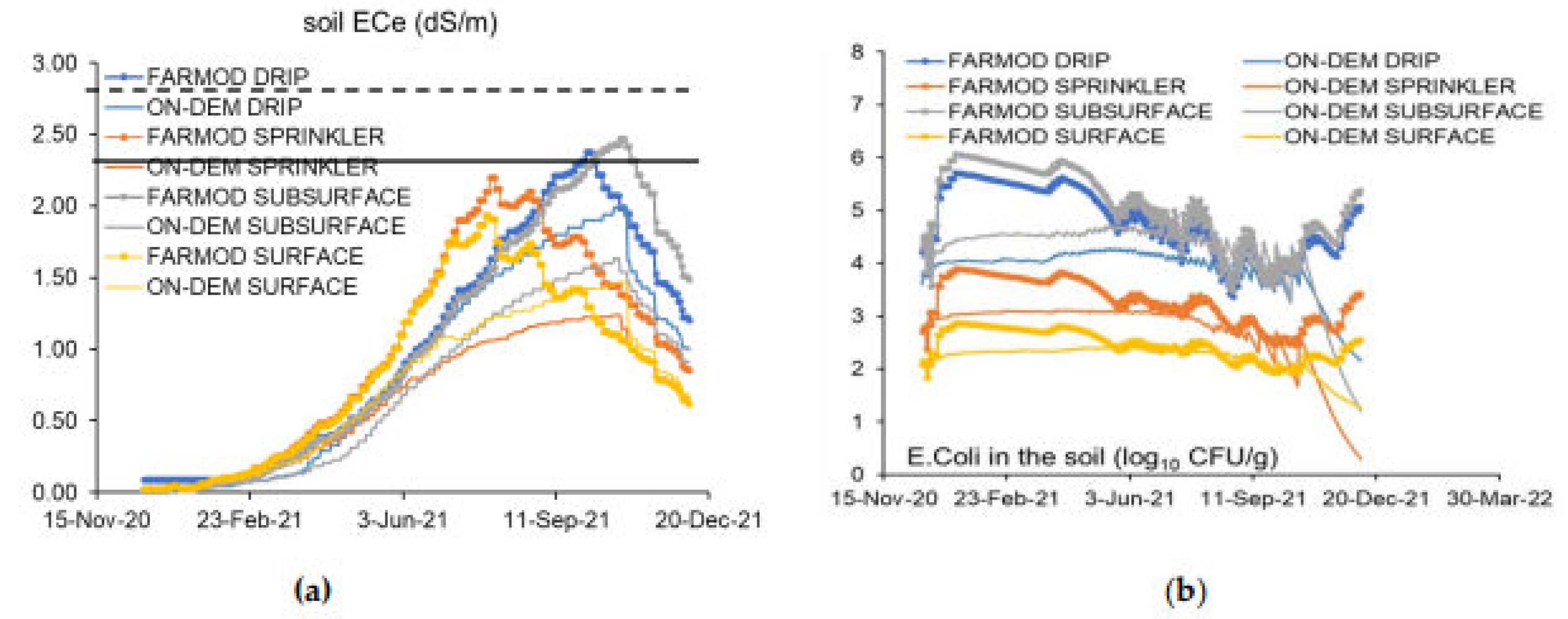

Soil salinity is a crucial factor to assess. The trend line of soil ECe values is shown in (

Figure 6a), the risk of E. coli associated with TWW reuse is considered. (

Figure 6b), shows the simulated E. coli trend in the soil between the FARMOD and ON-DEMAND scenarios with higher E. coli values observed in the FARMOD scenario.

In the FARMOD scenario, soil ECe was higher than in the ON-DEMAND scenario. Controlling soil ECe to achieve a range of less than 2 dS·m⁻¹ (indicated by the black line) has helped contain the risk of salt accumulation and potential leaching. In contrast, the FARMOD scenario saw ECe exceed 2.5 dS·m⁻¹ (indicated by the dashed black line). Soil salinity gradually and steadily increases until it peaks during the season when alfalfa requires a high amount of water. The SIM model suggests that supplying higher amounts of water can help gradually decrease soil salinity.

Consequently, the SIM schedule considers longer intervals between irrigation events and larger application volumes. This strategy may slow down drainage fluxes and improve nutrient distribution in the root zone, thereby reducing groundwater contamination. This approach can mitigate the osmotic impact caused by excessive salt introduced with TWW irrigation, which compromises soil physical and hydraulic characteristics, reducing water absorption and root activity [

26]. ECe values vary according to irrigation events, nutrient management, and soil water patterns. Although treatment procedures tend to eliminate salts and bring the water below critical values compared to TWW guidelines, irrigation events can still influence the soil’s response to salinity, especially in the long term. Part of the salts remain in the irrigation water, and even if TWW reaches acceptable values, this doesn’t mean that no harm reaches the soil due to complex processes.

The ON-DEMAND scenario generated by the model shows lower values of E. coli, indicating better results. This implies that the irrigation strategies suggested by the model can improve E. coli trends and have a better environmental impact. Regarding the irrigation system, the subsurface showed higher values of E. coli, which is explained by the fact that the subsurface has the highest direct contact with soils. This result aligns with findings by [

25], who found that increased irrigation frequency increased short-term E. coli contamination of soils by increasing the chances of interaction between wastewater and soils.

To limit the risk of E. coli infection, less frequent irrigation at intervals of more than three days is recommended, as E. coli die after exposure to harsh environmental conditions such as high temperatures, sun and wind [

27]. Prolonging irrigation events may thus increase the chance of E. coli exposure to these conditions, leading to their die-off.

3.2. Case Study 2: Citrus in Palestine

3.2.1. Yield And Nutrient Efficiency for Citrus

The citrus case study was set up through the model, and two scenarios were created for comparison.

Table 2 compares the FARMER observations and the FARMOD and ON-DEMAND scenarios. FARMER observations and FARMOD outputs were compared to calibrate the SIM model and very similar results were observed, validating the calibration. However, in the ON-DEMAND scenario, it was clear that by selecting an appropriate irrigation schedule, N and P uptake by roots was greater, leading to a higher yield. The farmer’s yield was 22,000 kg/ha compared to 24,260 kg/ha in the ON-DEMAND scenario.

3.2.2. Irrigation Management for Citrus

The irrigation scenario was also modeled by SIM using climate data, as depicted in the (

Figure 7a). The trendline of cumulative irrigation in the middle of the season tends to stabilize (

Figure 7b). The presence or absence of irrigation events across two TWW irrigation years (August 2020 to October 2021) justifies this behavior. After April, rainfall events are no longer present (

Figure 7b). The cumulative irrigation trendline tends to grow to compensate for the water needed for plant growth.

The flowering season begins in April and is highly susceptible to insufficient water amounts. A more severe water shortage during the summer, followed by irrigation events, may encourage out-of-season flowering, typically resulting in the production of useless second fruits and may diminish the yield of the subsequent main crop[

28]. Water availability directly impacts the fruit set. At this time, enough water is also required to make nutrients, particularly N, available to the crop. Additionally, a lack of water during fruit sets affects output by resulting in a significant June or December fruit drop. Therefore, proper irrigation management is required [

28]. In this scenario, the SIM model recommended utilizing larger amounts of water to meet the requirement.

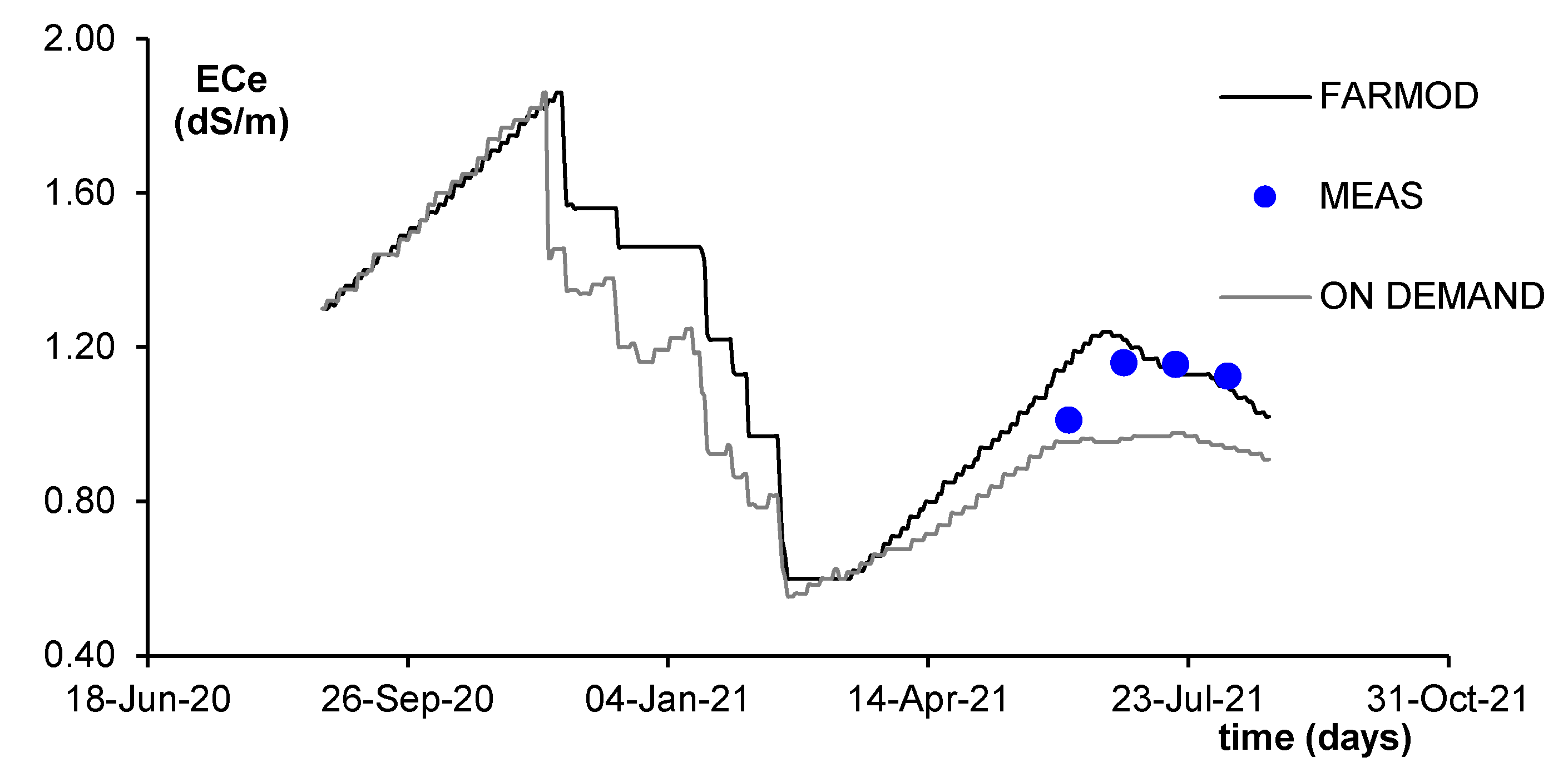

3.2.3. Salinity Management for Citrus

Salinity levels in the soil also play an essential role. Yield could decrease after ten years of supply with TWW irrigation[

29]. In (

Figure 8), it is clear how ECe levels are related to irrigation events. In the ON-DEMAND scenario, during the irrigation period, ECe values tend to rise, then decline when irrigation is no longer present. This could be due to the rainfall events reducing the trend of ECe from 1.60 to 0.80 dS·m⁻¹, which can trigger water drainage. The blue dots (MEAS) refer to the measurements obtained by four field campaigns: 7 June, 28 June, 18 July, and 28 August, conducted in the Palestine citrus case study in 2021, which agree with ECe values simulated by SIM.

According to Maas and Hoffman's salinity range, problems appear when the irrigation water’s electric conductivity (ECe) is higher than 1.5 dS·m⁻¹. Both types of water fail to meet all the requirements for use, posing a severe issue for citrus trees, which are sensitive to salinity. High concentrations of Cl− and Na+ in leaves inhibit CO2 assimilation, impacting various mechanisms [

30,

31,

32].

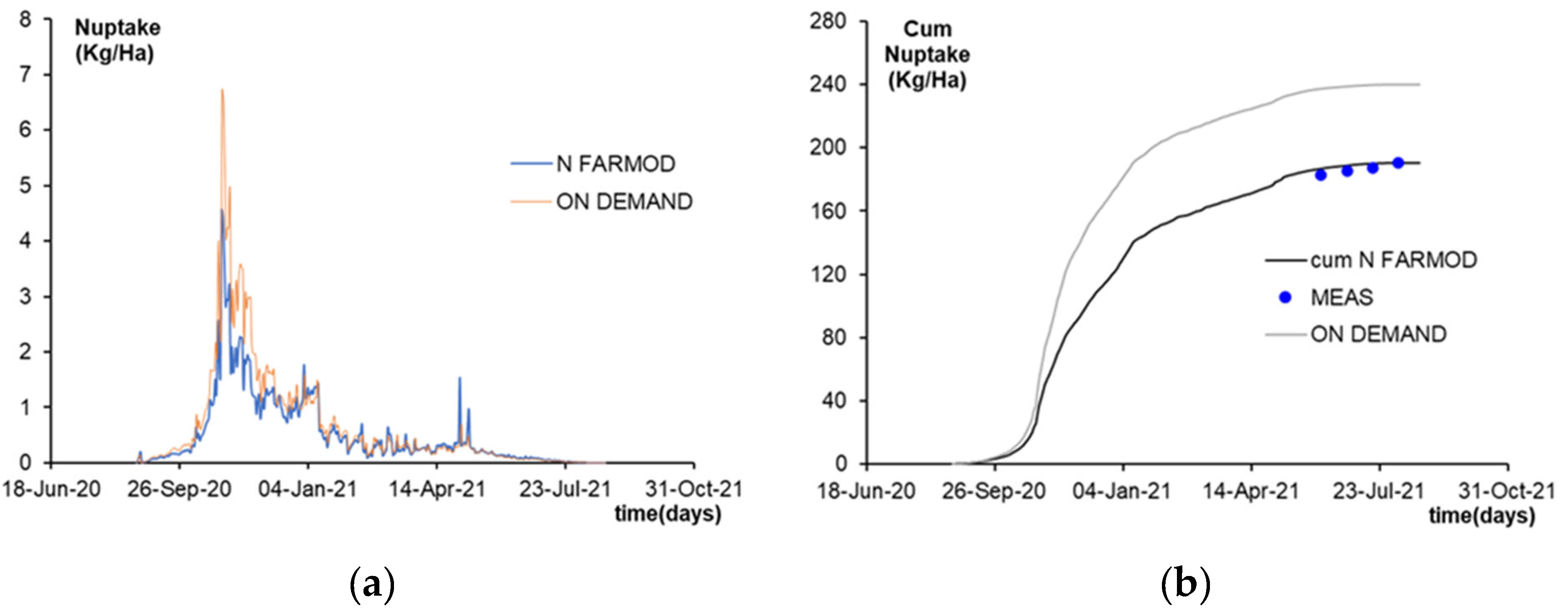

3.2.4. Nutrients Management for Citrus

Regarding nutrients, N is crucial for citrus tree growth, fruit yield, and quality. Adequate amounts are needed, especially during critical crop growth stages, like fruit initiation and development. Since SIM models provide only N and P modules, P is present in TWW in high concentrations.

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 show the daily and cumulative N and P uptake, respectively. Blue symbols represent nitrogen concentration values measured to four field campaigns. The cumulative uptake curves follow the same pattern as the irrigation curve. The irrigation strategy suggested by the model, known as ON DEMAND, resulted in better N and P uptake.

According to [

33], the overall range of N can vary between 160 and 232 kg/ha/year. In this case, the farmer applied almost 190 kg/ha of N compared to 240 kg/ha applied ON DEMAND, indicating that the SIM suggestion is closer to the appropriate N level. On-demand scenarios showed higher P uptake, which could be proper irrigation management. Although P is essential for photosynthesis, synthesis, carbohydrate breakdown, and energy transmission within trees, it is not considered one of the major elements for citrus production. However, the phosphorus results are shown as they are outputs of the SIM model.

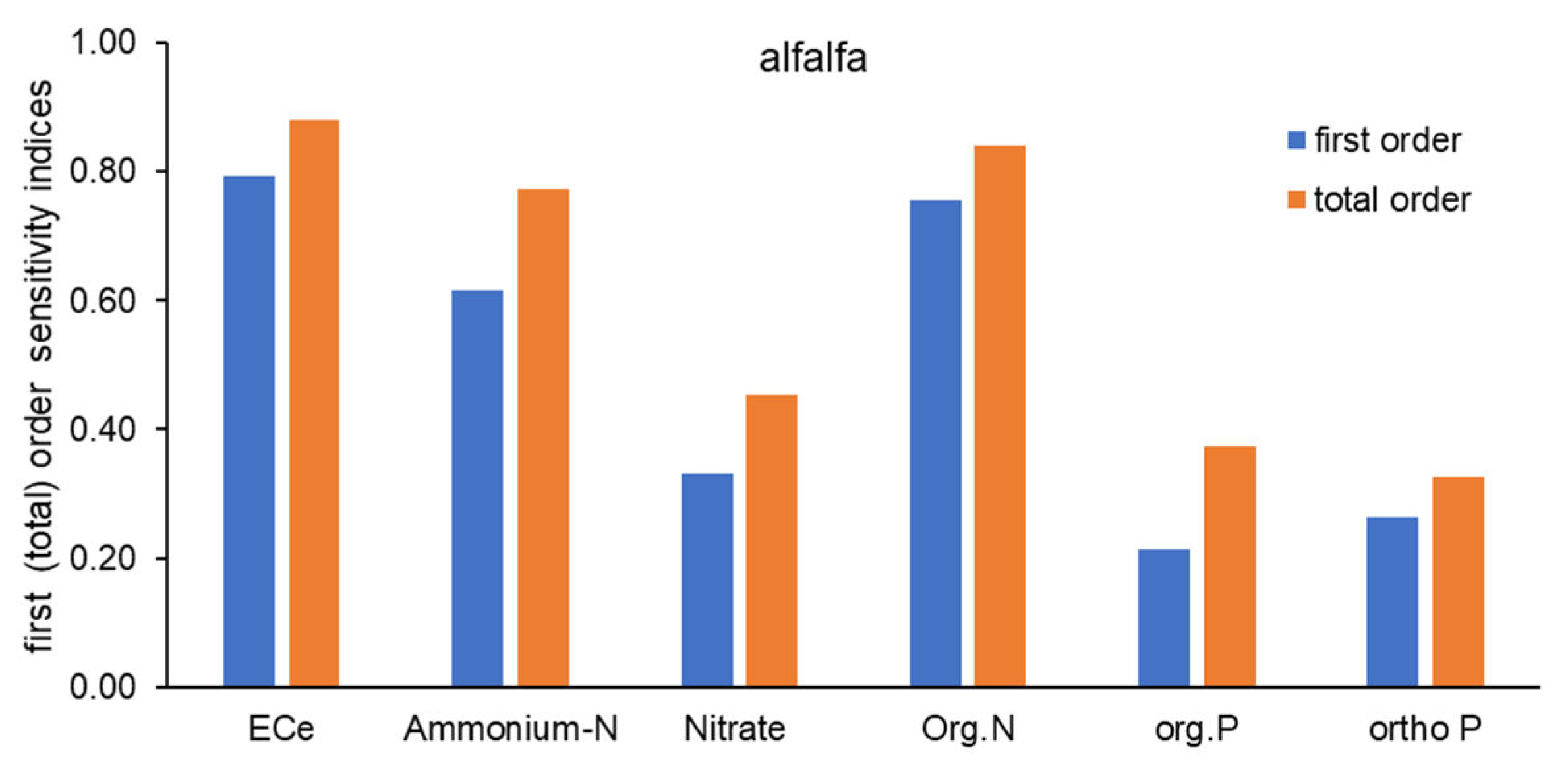

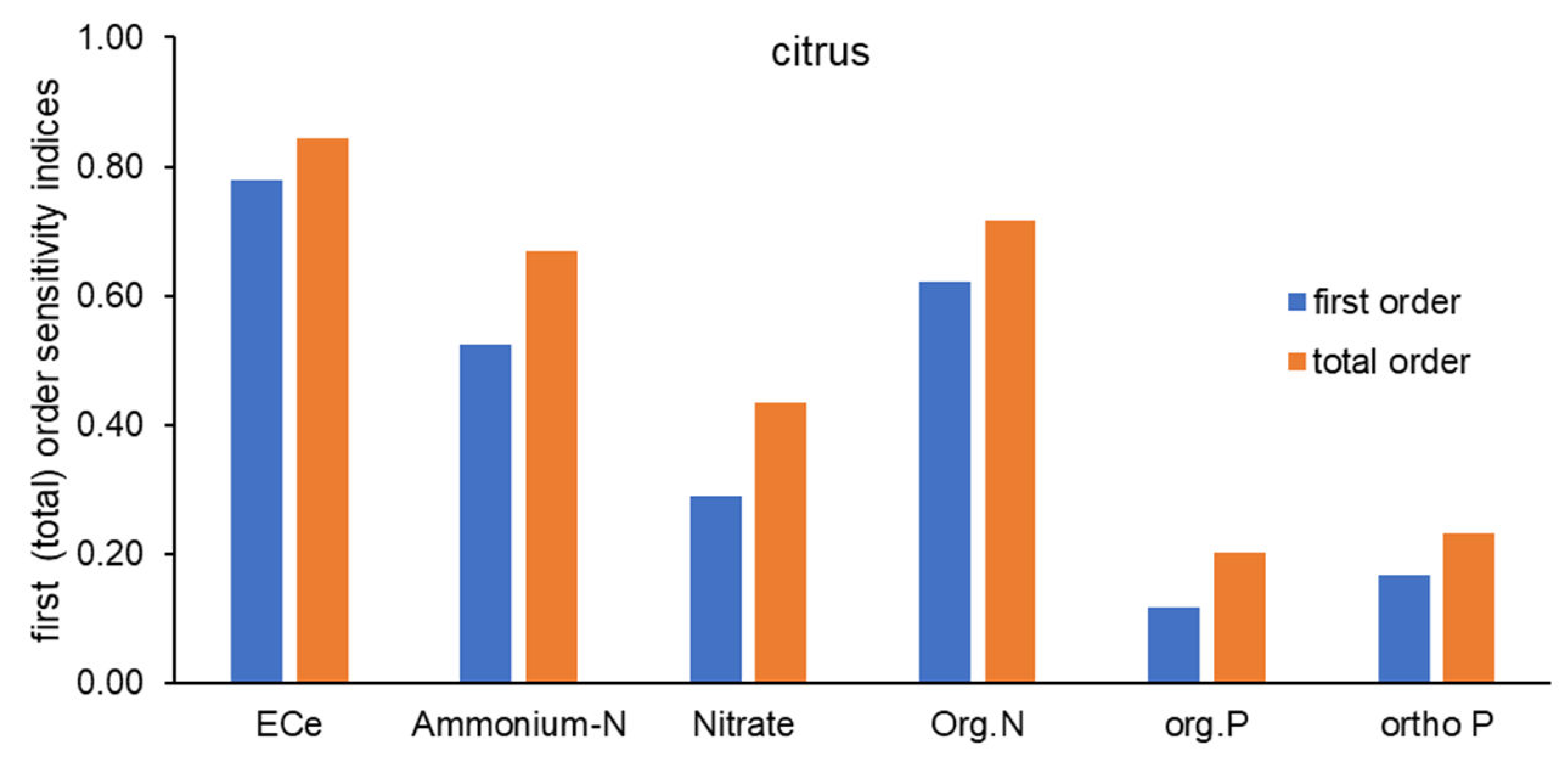

3.3. Sensitivity Analysis for Alfalfa and Citrus

The Sobol method was used for case studies 1 and 2 to compute the most sensitive parameters. Both, the first order and total order indices were calculated. The X-axis shows the parameters generated as output. The MOEA Framework software was used to compute the indexes [

34]. For alfalfa, salinity and N were identified as the most sensitive parameters that need to be monitored for future long-term WW reuse (

Figure 11).

This is very crucial because alfalfa is significantly affected by high salinity levels. As a legume, alfalfa is more susceptible to salt stress than cereals. Salt stress lowers alfalfa germination by weakening respiration, reduces biomass output by impeding photosynthesis, and affects fodder quality by lowering soluble protein and P levels. Furthermore, salt stress impacts plant nutrient adsorption capacity, especially N adsorption ability, indirectly reducing plant development [

35].For citrus, ECe and N are the most sensitive parameters affecting simulation performance (

Figure 12).

Proper TWW irrigation practices require monitoring these parameters. ECe is particularly critical since citrus trees are very sensitive to salinity. It was found that found that soil salinity significantly limits citrus production worldwide [

36].Although data on fruit yields in response to salinity is limited, it indicates that grapefruit, lemons, and oranges are among the most sensitive crops. Fruit yields decrease by about 13% for each 1.0 dS·m⁻¹ increase in the electrical conductivity of the saturated soil extract (ECe) once soil salinity exceeds a threshold ECe of 1.4 dS·m⁻¹ under conventional irrigation practices. Canopy thinning, severe leaf loss, and twig dieback can all be caused by salinity. Salt stress can also cause fruit maturity to be delayed and fruit production to be reduced by reducing the number of fruits produced per tree and the size of the fruit [

37].

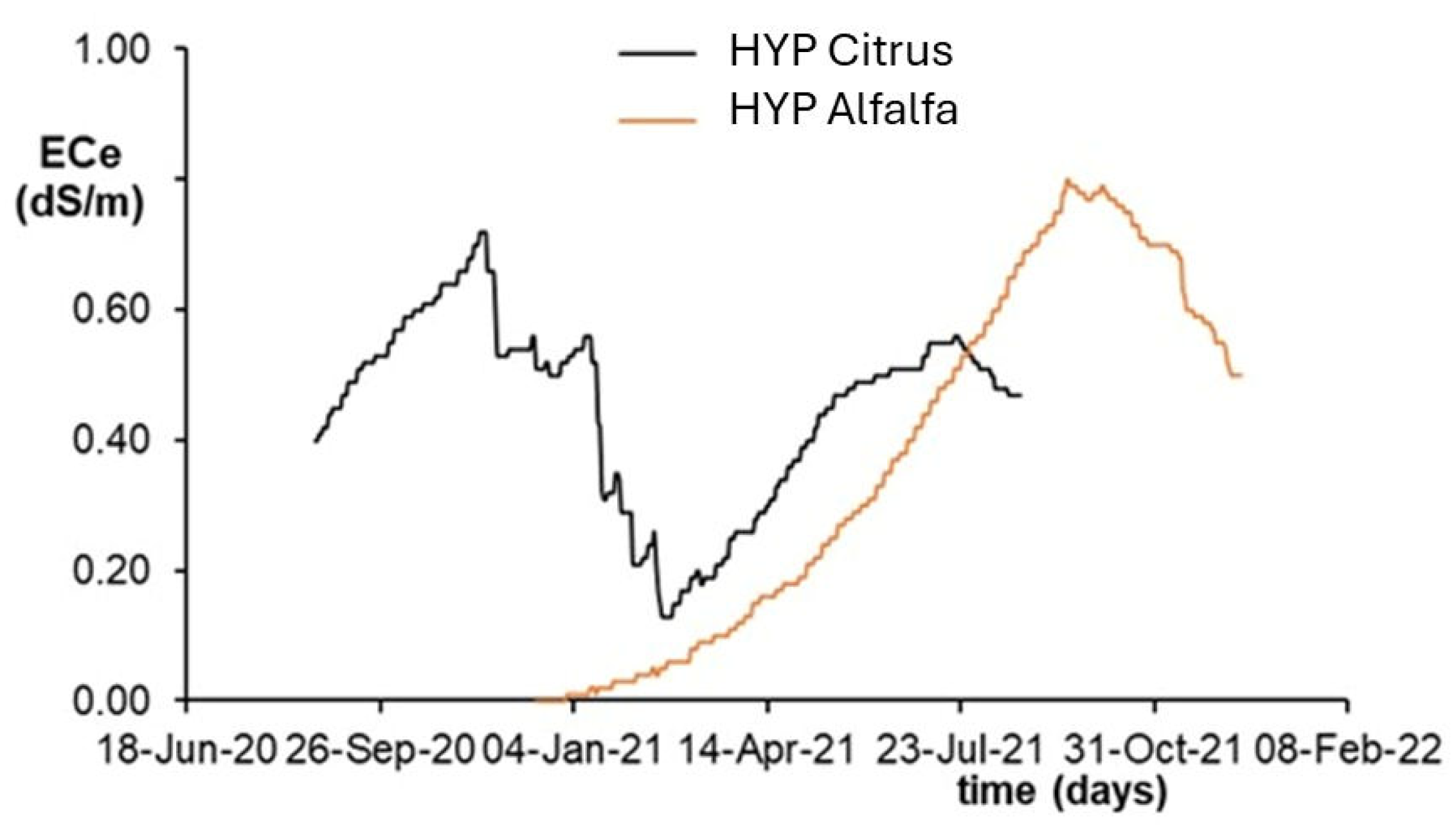

3.4. Hypothetical Scenario for Alfalfa and Citrus

The alfalfa experiment was conducted on Vertisol soil. Optimal vertisol characteristics were selected as input for the hypothetical HYP scenario based on good initial soil conditions and TWW quality extrapolated from literature review research38]. Specifically, the soil had 0.12% N, 0.007% P, 1.96% organic matter, and an ECe of 0.144 dS·m⁻¹. Optimal water quality, identified from secondary treatment plants in literature and successful case studies included 0.69 mg/l N, 4,5 mg/l P, 0.3 dS·m⁻¹ electrical conductivity, and 4.9 CFU/100ml E. coli [

39].

For citrus, grown on Terra Rossa soil, optimal values from the literature [

40] were used in the SIM model to improve TWW irrigation outputs provided by the ON-DEMAND scenario. These values, collected under TWW irrigation long-term condition, included 0.167% N, 4.35 ppm P, 1.68% organic matter, and ECe was 0.3 dS·m⁻¹. Water quality parameters from tertiary treatment, considered very good, were also used in SIM, with 12.1 mg/l N, 7.16 mg.l-1 P, and 0.87 dS·m⁻¹ Ece [

39].The results for ECe, N, and P for case studies 1 and 2 were provided. In addition, E. coli values for alfalfa were noted as potentially dangerous to livestock feed, especially in the AL Ramtha area, where husbandry activities are high.

Figure 13 shows the trendline for ECe in alfalfa and citrus.

To citrus, the trendline of ECe values in the winter season decreases due to rainfall events and the halt of the irrigation period, while they restart to grow when irrigation resumes. On the contrary, for alfalfa, the ECe trend increases during the first winter season (Jan-March, 2021), while the values decrease during the second winter season since it reached the end of the experiment of alfalfa. However, throughout the entire season, ECe values did not exceed 0.8 dS·m⁻¹, indicating acceptable results. Low salinity levels enhance nutrient absorption, reduce plant stress, and improve soil structure.

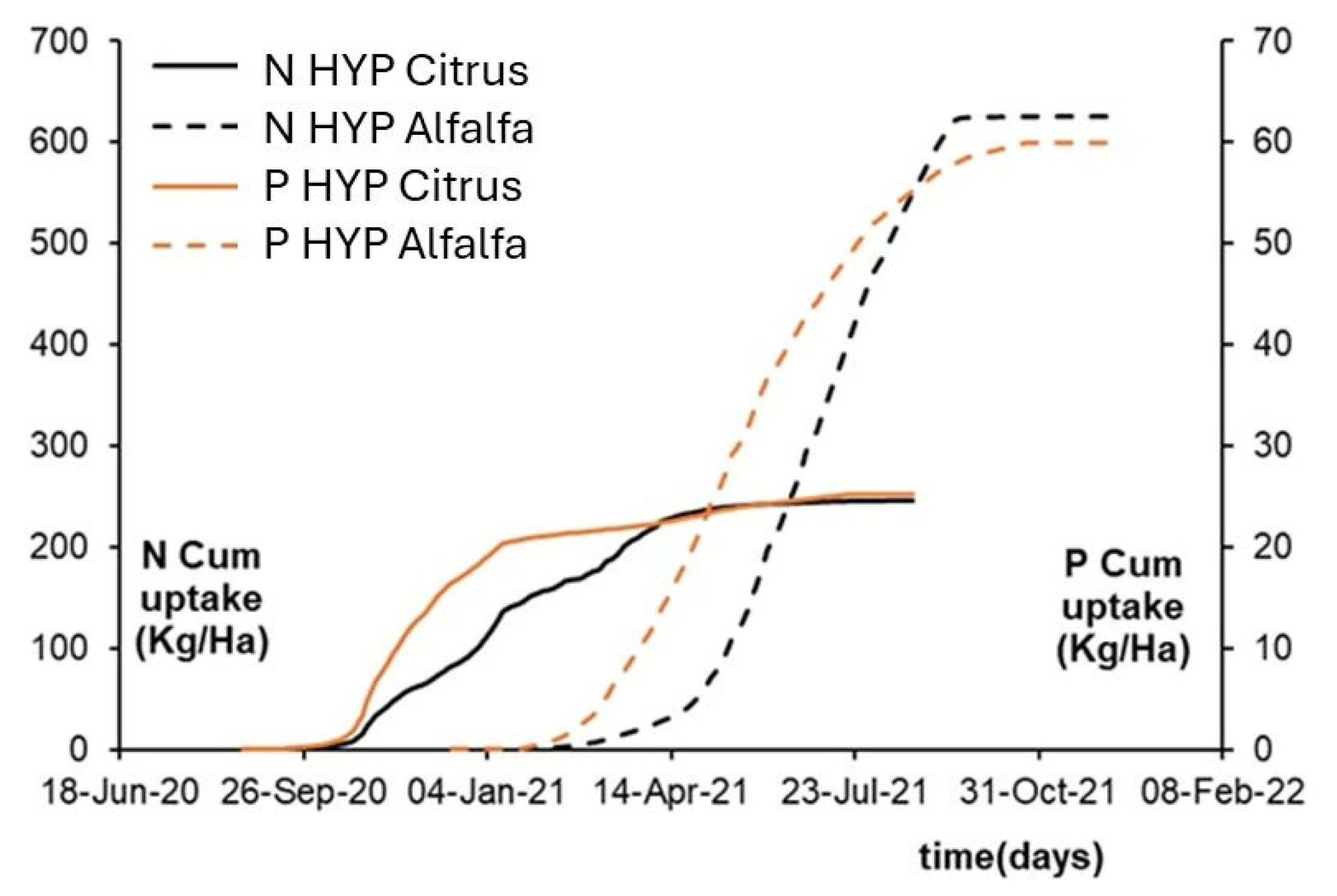

Figure 14shows improved nitrogen uptake compared to poor initial conditions. The amount of N absorbed by alfalfa and citrus meets the nutrient requirements for the hypothetical scenario. For citrus, N uptake reaches 250 kg/ha. In contrast, it was demonstrated that applying 200 kg N/ha yearly is adequate to maintain high-quality citrus yields and obtain good tree development [

39].Similarly, for alfalfa, SIM generated 650 kg/ha in the optimum scenario, whereas 500 kg/ha is considered the average value for good yield and production [

41].

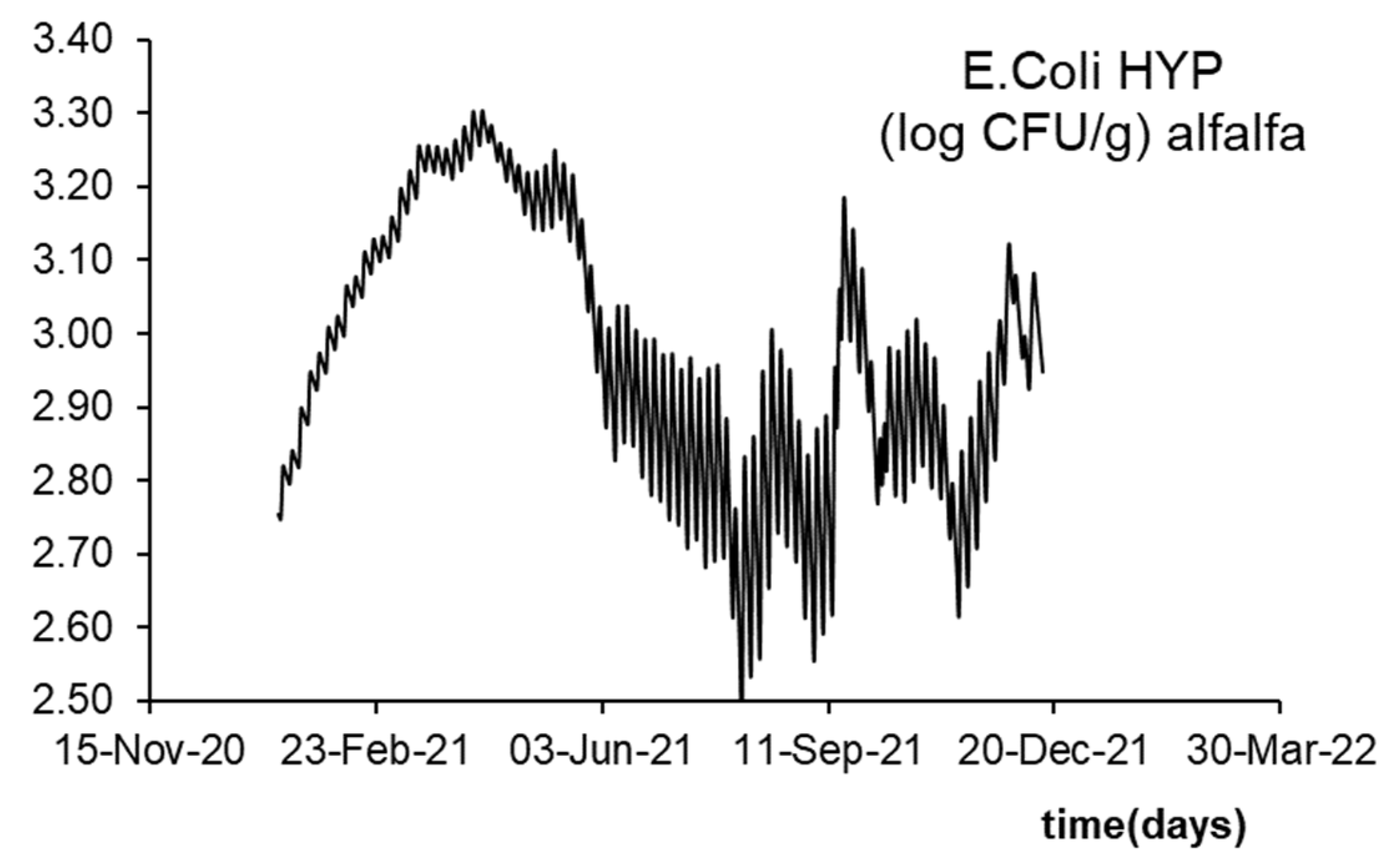

In the HYP scenario, alfalfa E. coli level in the soil did not exceed 3.3 log CFU/g (

Figure 15). Integrating appropriate practices with irrigation management can limit the bacterial contaminants that pose hazards to humans. For example, E. coli levels decreased from 6 log CFU/g in the FARMOD scenario to a maximum of 3.3 log CFU/g in the hypothetical scenario by improving water quality and soil conditions. This scenario aligns with observations from the same experiment, showing low E. coli values. The findings are consistent with previous research on the risks associated with infections in agricultural water irrigation. One study showed that for water with less than or equal to 2 log E. coli CFU/100 mL, no pathogens were found on crops regardless of irrigation methods [

42].

For a significant period during the year, as shown in

Figure 15, E. coli levels were slightly higher than 2 log CFU/g. This suggests that alfalfa could be safe with an acceptable E. coli infection limit. It is well known that the main factors affecting soil contamination when using partially TWW are E. coli concentration in the irrigation water and its natural die-off. Studies have demonstrated that E. coli can survive in soil for several days to several months, depending on soil temperature and moisture[

43]. Therefore, implementing a no-harm TWW irrigation management plan, combined with subsurface drip irrigation, can also be a strategy to avoid E. coli contamination when applying TWW effluent.

Overall, integrating proper practices based on field data, modeling, and soil tilth management could be a potential strategy to preserve soil quality for long-term TWW reuse scenarios in Jordan and Palestine, where TWW irrigation is a well-established practice.

4. Conclusions

The reuse of TWW, particularly in agriculture, is often promoted as an appealing and pragmatic solution that significantly relieves pressure on water resources and provides additional agronomic benefits associated due to TWW’s high nutritive value. However, this alternative resource is being used without fully accounting for its unique characteristics. The main challenge remains in determining the appropriate irrigation management plan when TWW is used continuously. This study aimed to highlight the importance of selecting appropriate irrigation scheduling tailored for TWW. Two case studies, continuously irrigated with TWW, were considered to determine the most appropriate irrigation scheduling by coupling field data and modelling using the SIM model. Two scenarios were simulated: 1) FARMOD retrieved farmer planning and model calibration; 2) ON-DEMAND referred to the schedule suggested by SIM for alfalfa in Jordan and citrus in Palestine. The main parameters that were assessed are salinity, yield, N and P uptake, and E. coli.

In the case study 1, four different irrigation systems— surface drip, surface, sprinkler, and subsurface drip— were compared under the two scenarios mentioned above. When alfalfa was sub-surface irrigated, the ON-DEMAND scenario produced a yield of 17,250 kg/ha, compared to 15,600 kg/ha in the FARMOD scenario. Considering TWW as a nutrient supply, the ON-DEMAND scenario resulted in 668 kg/ha of N uptake under drip irrigation, compared to 502 kg/ha in the FARMOD scenario. The same applies to P, where 47 kg/ha were uptaken under the ON-DEMAND scenario with subsurface drip irrigation, compared to 42 kg/ha in the FARMOD scenario. Regarding soil salinity response, for alfalfa, the ON-DEMAND scenario showed lower ECe values compared to the FARMOD scenario, resulting in values lower than 2.0 dS·m⁻¹.

In case study 2, the FARMOD scenario provided a citrus yield of 22,000 kg/ha while the ON-DEMAND scenario resulted in 24,260 kg/ha. The irrigation management that considered frequency and application volumes in the ON-DEMAND scenario resulted in 240 kg/ha and 23.7 kg/ha of N and P uptake respectively, compared to 190 kg/ha and 18.9 kg/ha in the FARMOD scenario.

In the FARMOD scenario, ECe for citrus was around 2 dS·m⁻¹ compared to 1.2 dS·m⁻¹ mainly observed in the second irrigation season to the ON-DEMAND scenario. For alfalfa, E. coli levels reached a maximum of 6 log₁₀ CFU·g⁻¹ the FARMOD scenario, compared to 2 log₁₀ CFU·g⁻¹ in the ON-DEMAND scenario. Sensitivity analysis, revealed that soil solution electrical conductivity and nitrogen were the most sensitive parameters, indicating conditions where adverse impacts may occur under long-term use of TWW.

Improving water quality and implementing soil tilth management are critical for ensuring the sustainability of TWW reuse. A hypothetical scenario, assuming soil initial conditions before TWW irrigation practices, was run through SIM. This scenario showed lower ECe (0.8 dS·m⁻¹) and lower E. coli levels (3.3 log₁₀ CFU·g⁻¹) compared to the FARMOD and ON-DEMAND scenarios. These results demonstrate that combining field data and modelling is crucial for identifying appropriate irrigation management strategies, as it leads to higher yields, enhanced nitrogen and phosphorus uptake, and lower salinity and E. coli values.

While determining the best irrigation management strategy with TWW cannot be accomplished solely through modelling and given that conditions and assumptions may change in the future, these findings show that the SIM model is an effective tool for maximizing the benefits and mitigating the negative impacts of TWW reuse. Furthermore, these findings support the use of reliable prediction models to adapt irrigation schemes to TWW, suggesting that such models should be a vital component of policies promoting TWW use in irrigated agriculture.

Establishing a community of practice may constitute a vital step forward in TWW reuse, as it may allow for an exchange of results and the application of proper practices. This requires a series of practices that could be applied and implemented in future work for sustainable TWW reuse including farm filtration techniques; crop selection considering salinity, toxicity, and health hazards; selection of irrigation methods; field management practices, including soil tilth and timing of irrigation to withholding before harvest.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.K. and G.D.; methodology, G.D., R.A, and R.K.; software, R.A. and G.D.; validation, R.A., G.D. and R.K.; formal analysis, R.A. and G.D.; investigation, G.D. and R.K.; resources, R.K.; data curation, G.D.; writing—original draft preparation, R.A.; writing—review and editing, G.D. and R.K.; visualization, R.A. and G.D.; supervision, G.D. and R.K.; project administration, R.K.; funding acquisition, R.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data available based on request from authors.

Acknowledgments

This research was carried out within the framework of the MENAWARA project: Non-Conventional Water Re-use in Agriculture in Mediterranean Countries, funded by the European Union (

https://www.enicbcmed.eu/projects/menawara). Deep gratitude is owed to WeWorld (Palestine), the National Agricultural Research Center (NARC) (Jordan), and all the partners and local agricultural cooperatives and ministries in Jordan and Palestine for providing all the necessary data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ofori, S.; Abebrese, D.K.; Růžičková, I.; Wanner, J. Reuse of treated wastewater for crop irrigation: water suitability, fertilization potential, and impact on selected soil physicochemical properties. Water 2024, 16, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yang, H.; Gosling, S.N.; Kummu, M.; Flörke, M.; Pfister, S.; Hanasaki, N.; Wada, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, C.; Alcamo, J.; Oki, T. Water scarcity assessments in the past, present, and future. Earths Future 2017, 5, 545–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qadir, M.; Sharma, B.R.; Bruggeman, A.; Choukrallah, R.; Karajeh, F. Non-conventional water resources and opportunities for water augmentation to achieve food security in water scarce countries. Agric. Water Manag. 2007, 87, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 4Silva, J.A. Wastewater treatment and reuse for sustainable water resources management: a systematic literature review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakkak, A. Water Scarcity in Jordan: An Overview. Available online: https://www.ecomena.org/water-jordan/ (accessed on 21 November 2024).

- Almanaseer, N.; Hindiyeh, M.; Al-Assaf, R. Hydrological and environmental impact of wastewater treatment and reuse on Zarqa river basin in Jordan. Environments 2020, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ait-Mouheb, N.; Mayaux, P.L.; Mateo-Sagasta, J.; Hartani, T.; Molle, B. Water reuse: a resource for mediterranean agriculture. In Water Resources in the Mediterranean Region; Zribi, M., Brocca, L., Icamblay, Y., Molle, F., Eds.; Elsevier, 2020; pp. 107–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shtaya, M.J.Y.; Yaseen, K.; Abdelraheem, W.; Hannoun, Y.; Qaoud, H.A.; Al-Fares, H.; Daoud, A.; Fadah, Z.; Alimari, A. Effect of tertiary treated wastewater on some soil properties and wheat yield. Desalination Water Treat. 2021, 236, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isayenkov, S.V.; Maathuis, F.J.M. Plant salinity stress: many unanswered questions remain. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snapp, S.; Sapkota, T.B.; Chamberlin, J.; Cox, C.M.; Gameda, S.; Jat, M.L.; Marenya, P.; Mottaleb, K.A.; Negra, C.; Senthilkumar, K.; Sida, T.S.; Singh, U.; Stewart, Z.P.; Tesfaye, K.; Govaerts, B. Spatially differentiated nitrogen supply is key in a global food–fertilizer price crisis. Nat. Sustain. 2023, 6, 1268–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sdiri, W.; AlSalem, H.S.; Al-Goul, S.T.; Binkadem, M.S.; Ben Mansour, H. Assessing the effects of treated wastewater irrigation on soil physico-chemical properties. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragonetti, G.; Khadra, R. Assessing soil dynamics and improving long-standing irrigation management with treated wastewater: a case study on citrus trees in Palestine. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonigro, A.; Montemurro, N.; Rubino, P.; Vergine, P.; Pollice, A. Reuse of treated municipal wastewater for irrigation in Apulia region: the “IN.TE.R.R.A.” project. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2015, 14, 1665–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelia, V.; Šimůnek, J.; Boote, K.; Hoogenbooom, G. Coupling DSSAT and HYDRUS 1-D for simulations of soil water dynamics in the soil-plant-atmosphere system. J. Hydrol. Hydromech. 2018, 66, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadra, R.; Sagardoy, J.A.; Taha, S.; Lamaddalena, N. Participatory irrigation management and transfer: setting the guiding principles for a sustaining monitoring & evaluation system – a focus on the mediterranean. Water Resour. Manag. 2017, 31, 4227–4238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazahrih, N.Th.; Albalawneh, A.; Bani Hani, N.; Khadra, R.; Abo Dalo, A.; Al-Omari, Y.; Alomari, B.; Abu Hammad, M.; Martin, I.; Fahd, K.; Carletti, A.; Paulotto, A. , Haddad, N. Impact of reclaimed wastewater on alfalfa production under different irrigation methods. Water Pract. Technol. 2024, 19, 2226–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horneck, D.A.; Sullivan, D.M.; Owen, J.S.; Hart, J.M. Soil test interpretation guide; Oregon State University: Corvallis, OR, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- El-Shafei, A.A.; Mattar, M.A. Irrigation scheduling and production of wheat with different water quantities in surface and drip irrigation: field experiments and modelling using CROPWAT and SALTMED. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Public Health Association, American Water Works Association, W.E.F. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 24th ed.; APHA press: Washington DC, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pichery, C. Sensitivity analysis. In Encyclopedia of Toxicology, 3rd ed.; Wexler, P., Ed.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 236–237. ISBN 978-0-12-386455-0. [Google Scholar]

- Hamby, D.M. A review of techniques for parameter sensitivity analysis of environmental models. Environ. Monit. Assess. 1994, 32, 135–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragonetti, G.; Khadra, R.; Daccache, A.; Oubelkacem, A.; Choukrallah, R.; Lamaddalena, N. Development and application of a predictive model for treated wastewater irrigation management in a semiarid area. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2020, 16, 910–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, M.-J.; Choi, Y.S. Sensitivity analysis to investigate the reliability of the grid-based rainfall-runoff model. Water 2018, 10, 1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montazar, A.; Sadeghi, M. Effects of applied water and sprinkler irrigation uniformity on alfalfa growth and hay yield. Agric. Water Manag. 2008, 95, 1279–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahlou, F.; Mackey, H.R.; McKay, G.; Onwusogh, U.; Al-Ansari, T. Water planning framework for alfalfa fields using treated wastewater fertigation in Qatar: an energy-water-food nexus approach. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2020, 141, 106999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hettiarachchi, H.; Ardakanian, R. Safe Use of Wastewater in Agriculture: Good Practice Examples; United Nations University, Institute for Integrated Management of Material Fluxes and Resources: Dresden, Germany, 2016; ISBN 978-3-944863-30-6. [Google Scholar]

- Assouline, S.; Russo, D.; Silber, A.; Or, D. Balancing water scarcity and quality for sustainable irrigated agriculture. Water Resour. Res. 2015, 51, 3419–3436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wen, J. Effects of water managements on transport of E. coli in soil-plant system for drip irrigation applying secondary sewage effluent. Agric. Water Manag. 2016, 178, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citrus, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Available online: https://www.fao.org/land-water/databases-and-software/crop-information/citrus/es/ (accessed on 24 November 2024).

- Intrigliolo, F.; Intelisano, S. Effects of differential nitrogen application on nutrition, growth, yield and fruit quality in young lemon trees. Acta Hort. 1997, 448, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syvertsen, J.P.; Garcia-Sanchez, F. Multiple abiotic stresses occurring with salinity stress in citrus. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2014, 103, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, D.; Laufer, A.; Bardhan, G.; Levy, G.J. Salinity control in a clay soil beneath an orchard irrigated with treated wastewater in the presence of a high-water table: a numerical study. J. Hydrol. 2015, 531, 198–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, F.; Syvertsen, J.P. Salinity tolerance of cleopatra mandarin and carrizo citrange citrus rootstock seedlings is affected by CO2 enrichment during growth. J. Am. Foc. Hortic. Sci., 2006, 131, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammami, A.; Rezgui, S.; Hellali, R. Leaf nitrogen and potassium concentrations for optimum fruit production, quality and biomass tree growth in clementine mandarin under mediterranean climate. J. Hortic. For., 2010, 2, 161–170. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.-Y.; Trame, M.; Lesko, L.; Schmidt, S. Sobol sensitivity analysis: a tool to guide the development and evaluation of systems pharmacology models. CPT Pharmacomet. Syst. Pharmacol. 2015, 4, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, W.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, C.; Li, K.; Sun, Z.; Li, Y.; Li, H. Alfalfa growth and nitrogen fixation constraints in salt-affected soils are in part offset by increased nitrogen supply. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, E.V. Salinity and citriculture. Tree Physiol. 1993, 12, 195–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuntyastuti, H.; Lestari, S.A.D. Application of manure and npk fertilizer on grobogan variety and aochi/w-c-6-62 soybean as promise line in lowland vertisol ngawi, Indonesia. Nusant. Biosci. 2017, 9, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safari, G.H.; Yetilmezsoy, K.; Mahvi, A.H.; Zarrabi, M. Post-treatment of secondary wastewater treatment plant effluent using a two-stage fluidized bed bioreactor system. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 2013, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayodele, F.; Babalola, T. Physico-chemical properties of an alfisol under different tillage systems in the basement complex of kogi state. Sci. Forum J. Pure Appl. Sci. 2021, 21, 286–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Long, Q.; Li, W.; Wang, Z.; He, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Xiong, H.; Guo, C.; Zhang, G.; Luo, B.; Qiu, J.; Chen, X.; Zhang, F.; Shi, X.; Zhang, Y. Mapping the environmental cost of a typical citrus-producing county in China: hotspot and optimization. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abi Saab, M.T.; Jomaa, I.; El Hage, R.; Skaf, S.; Fahed, S.; Rizk, Z.; Massaad, R.; Romanos, D.; Khairallah, Y.; Azzi, V.; Sleiman, R.; Abi Saad, R.; Hajjar, C.; Selllami, M.; Aziz, R.; Sfeir, R.; Nassif, M.; Sagasta, J. Are fresh water and reclaimed water safe for vegetable irrigation? empirical evidence from Lebanon. Water 2022, 14, 1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Nishihara, M.; Kawasaki, Y.; Yokoyama, A.; Matsuura, K.; Koga, T.; Ueno, D.; Inoue, K.; Someya, T. Inactivation of Escherichia coli in soil by solarization. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2009, 55, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

(a) Experimental design and (b) field layout for alfalfa in Jordan.

Figure 1.

(a) Experimental design and (b) field layout for alfalfa in Jordan.

Figure 2.

Experimental design for citrus in Palestine.

Figure 2.

Experimental design for citrus in Palestine.

Figure 3.

(a) The trend of the upward (crop evapotranspiration) and downward fluxes (rainfall) throughout the TWW irrigation season (Nov 2020 to Dec 21) and (b) Comparison between the cumulative TWW irrigation requirements between the two scenarios: FARMOD and ON-DEMAND.

Figure 3.

(a) The trend of the upward (crop evapotranspiration) and downward fluxes (rainfall) throughout the TWW irrigation season (Nov 2020 to Dec 21) and (b) Comparison between the cumulative TWW irrigation requirements between the two scenarios: FARMOD and ON-DEMAND.

Figure 4.

Weekly irrigation volume accounted for a) surface drip irrigation, (b) sprinkler irrigation, (c) subsurface drip irrigation, and (d) surface irrigation.

Figure 4.

Weekly irrigation volume accounted for a) surface drip irrigation, (b) sprinkler irrigation, (c) subsurface drip irrigation, and (d) surface irrigation.

Figure 5.

(a)The cumulative trend of Nitrogen and (b) Phosphorus uptake simulated for two scenarios: FARMOD and ON-DEMAND.

Figure 5.

(a)The cumulative trend of Nitrogen and (b) Phosphorus uptake simulated for two scenarios: FARMOD and ON-DEMAND.

Figure 6.

The trend of (a) soil Ece and (b) soil E. coli in FARMOD and ON-DEMAND scenario.

Figure 6.

The trend of (a) soil Ece and (b) soil E. coli in FARMOD and ON-DEMAND scenario.

Figure 7.

(a) The trend of the upward (crop evapotranspiration) and downward fluxes (rainfall) throughout TWW irrigation season (august 2020- august 2021), (b) Comparison between the cumulative TWW irrigation requirement of the two scenarios: FARMOD and ON-DEMAND.

Figure 7.

(a) The trend of the upward (crop evapotranspiration) and downward fluxes (rainfall) throughout TWW irrigation season (august 2020- august 2021), (b) Comparison between the cumulative TWW irrigation requirement of the two scenarios: FARMOD and ON-DEMAND.

Figure 8.

Soil ECe variation in soil for citrus.

Figure 8.

Soil ECe variation in soil for citrus.

Figure 9.

(a) Daily Nitrogen uptake and (b) Cumulative nitrogen uptake for citrus.

Figure 9.

(a) Daily Nitrogen uptake and (b) Cumulative nitrogen uptake for citrus.

Figure 10.

(a) Daily phosphorus uptake and (b) Cumulative phosphorus uptake for citrus.

Figure 10.

(a) Daily phosphorus uptake and (b) Cumulative phosphorus uptake for citrus.

Figure 11.

Sensitivity analysis for alfalfa.

Figure 11.

Sensitivity analysis for alfalfa.

Figure 12.

Sensitivity analysis for citrus.

Figure 12.

Sensitivity analysis for citrus.

Figure 13.

The trend of ECe for citrus and alfalfa in HYP scenario under optimal TWW irrigation management based on both good water and soil quality.

Figure 13.

The trend of ECe for citrus and alfalfa in HYP scenario under optimal TWW irrigation management based on both good water and soil quality.

Figure 14.

Cumulative nutrient uptake HYP scenario for citrus and alfalfa under optimal TWW irrigation management based on both good water and soil quality.

Figure 14.

Cumulative nutrient uptake HYP scenario for citrus and alfalfa under optimal TWW irrigation management based on both good water and soil quality.

Figure 15.

E. coli trend in HYP scenario for alfalfa under optimal TWW irrigation management based on both good water and soil quality.

Figure 15.

E. coli trend in HYP scenario for alfalfa under optimal TWW irrigation management based on both good water and soil quality.

Table 1.

Comparison between FARMER (observations), FARMOD, and ON-DEMAND simulations in terms of yield (kg/ha) and nutrient (N and P uptake) efficiency for alfalfa with different irrigation systems.

Table 1.

Comparison between FARMER (observations), FARMOD, and ON-DEMAND simulations in terms of yield (kg/ha) and nutrient (N and P uptake) efficiency for alfalfa with different irrigation systems.

| FARMER |

FARMOD |

ON-DEMAND |

| Irrigation systems |

Yield |

N |

P |

Yield |

N |

P |

Yield |

N |

P |

| |

| Drip |

14,200 |

504 |

41 |

14,861 |

502 |

42 |

16,410 |

668 |

45 |

| Sprinkler |

9,200 |

325 |

28 |

9,980 |

380 |

32 |

11,650 |

445 |

33 |

| Subsurface |

15,600 |

491 |

45 |

15,510 |

533 |

42 |

17,250 |

635 |

47 |

| Surface |

12,300 |

428 |

38 |

11,600 |

403 |

40 |

12,350 |

364 |

28 |

Table 2.

Comparison between FARMER (observations), FARMOD, and ON-DEMAND simulations in terms of yield (kg/ha) and nutrient (N and P uptake) efficiency for citrus with different irrigation systems.

Table 2.

Comparison between FARMER (observations), FARMOD, and ON-DEMAND simulations in terms of yield (kg/ha) and nutrient (N and P uptake) efficiency for citrus with different irrigation systems.

| FARMER |

FARMOD |

ON-DEMAND |

| IRR system |

Yield |

N |

P |

Yield |

N |

P |

Yield |

N |

P |

| |

| Drip |

22,000 |

191.60 |

18.96 |

21,910 |

190.4 |

18.98 |

24,260 |

240.02 |

23.7 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).