Submitted:

20 February 2025

Posted:

25 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

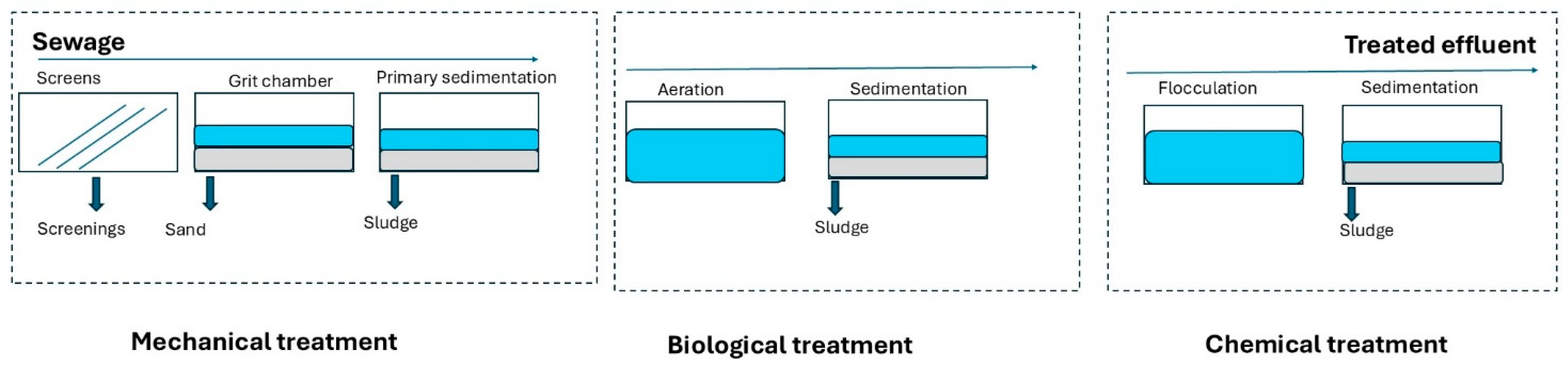

Understanding wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) coverage and treatment processes in Nordic countries (Finland, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Iceland, and their autonomous regions) is important in efforts improving sustainable sanitation and in implementation of upcoming new legislative requirements for urban wastewater treatment. The recast of Urban Wastewater Treatment Directive came into force in beginning of 2025 and mandates setting up national systems for wastewater surveillance, and mandates monitoring of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), in wastewater influent (pre-treatment) and effluent (post-treatment) across European Union (EU) or the European Economic Area (EEA) countries. Monitoring influent and effluent informs operational efficiency, provides wastewater surveillance (WWS) to track population health, and assesses the risks of anthropogenic pollutants and pathogens in the receiving waters. This study investigates WWTP coverage, treatment methods, and operational challenges in the Nordics via analyzing the outcomes received from a Webropol survey of environmental authorities, wastewater experts, and policymakers. Survey results were fortified with systematic review of peer-reviewed publications and government documents. We found, ~85–90% of the Nordic population is connected to centralized WWTPs, highlighting the feasibility of WWS for public health monitoring. Treatment processes vary across the region, shaped by population density, their location either in coastal or inland, or the sensitivity of recipient water bodies. Survey revealed, secondary treatment is nearly universal in Sweden and Finland but covers only about 4% of WWTPs in Iceland. Finland, Sweden, and Denmark enforce strict effluent standards, while Norway and Iceland face challenges in adopting similar practices due to harsh terrain, cold climates, and the practicality of discharging wastewater effluents into the oligotrophic Atlantic Ocean.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Results

3.1. Webropol Survey

Coverage of Centralized Wastewater Treatment Plants

Treatment Processes in Centralized Wastewater Treatment Plants

Legislative Provisions for Wastewater Treatment Plant Construction

Respondents’ Perception on the recast of European Union Urban Wastewater Treatment Directive, 2024

Key Criteria for establishing Wastewater Treatment Plants

Financing of Treatment Processes

3.2. Systematic Review of Peer-Reviewed Articles, Government Reports and European Union Online Portals

Decentralized Sanitations in Nordic countries

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

| SN | Study type | Study type | References |

| 1 | Review | The establishment and evolution of urban and rural water systems in Finland showcase a remarkable journey of innovation, institutional diversity, and trust-building. Over just two decades, Finland achieved efficient water pollution control by implementing advanced technologies and progressive legislation, setting a global benchmark. However, the nation now faces the pressing challenge of aging infrastructure, requiring innovative solutions and updated standards to maintain sustainability. The Finnish experience highlights the importance of continuous development and integrated approaches, offering valuable lessons for sustainable water management and future policymaking worldwide. | Katko et al 2022 [39] |

| 2 | Original paper (Finland & Sweden) | Many rural areas in Nordic countries rely on onsite treatment systems, though their efficiency varies widely. Phosphorus removal typically also reduces microbial loads in treated wastewater. | Heinonen-Tanski & Matikka 2017 [44] |

| 3 | Review | The study assessed on-site WWTP performance in Finland and Sweden, reviewed 1301 samples from 395 units across 10 studies. It revealed significant variability in treatment outcomes and emphasized the need for innovation and regulatory improvements for sustainable wastewater management. | Kinnunen et al. 2023 [55] |

| 4 | Original paper (Sweden) | Constructed wetlands are commonly used in Sweden for the further treatment of effluent from WWTPs. These wetlands, featuring diverse vegetation and algae, treat the remaining nutrients and suspended particles in the wastewater. The refined water is then discharged into surface water bodies. | Andersson et al. 2005 [46] |

| 5 | Review paper (Norway) | Norway's unique landscape—comprising mountains (44%), forests (38.2%), and freshwater, glaciers, and wetlands (13%)—limits the use of centralized sewerage systems, leaving a large population without access to them. In some areas, decentralized constructed wetlands have been adopted as an alternative treatment option. | Paruch et al 2011 [45] |

| 6 | Original study in Greenland | Sewage in Greenland is inadequately treated, contributing to plastic pollution in the Arctic marine environment. |

Bach et al. 204 [40] |

| Country | Treatment types | Total capacity (population equivalent) | Generated and entered plants (population equivalent) | Entering load (population equivalent) | Total Number of Plants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Denmark | NP removal | 11 792 195 | 11 729 212 | 7 315 084 | 261 |

| Phosphorus removal | 245 539 | 251 773 | 122 386 | 55 | |

| Other treatment | 3 000 | 2 000 | 1 827 | 1 | |

| Secondary treatment | 42 600 | 43 610 | 18 269 | 13 | |

| Total | 12 083 334 | 12 026 595 | 7 457 566 | 330 | |

| Finland | NP removal | 4 040 900 | 3 165 937 | 3 987 100 | 37 |

| P removal | 3 269 350 | 2 387 563 | 288 050 | 109 | |

| Total | 7 310 250 | 5 553 500 | 6 867 150 | 146 | |

| Iceland | Other treatment | 82 330 | 80 373 | 63 712 | 8 |

| No treatment | 640 500 | 428 468 | 430 596 | 9 | |

| Total | 722 830 | 508 841 | 494 308 | 17 | |

| Norway | NP removal | 1 535 570 | 1 910 824 | 186 4841 | 6 |

| Phosphorus removal | 2 888 802 | 3 160 215 | 2 867 078 | 151 | |

| Secondary treatment | 970 860 | 1 072 733 | 1 261 222 | 13 | |

| Primary treatment | 1 358 383 | 1 440 331 | 1 305 402 | 148 | |

| Total | 6 753 615 | 7 584 103 | 7 298 543 | 318 | |

| Sweden | NP removal | 11 230 759 | 10 082 800 | 8 779 682 | 145 |

| P removal | 3 277 630 | 2 732 930 | 2 244 622 | 283 | |

| Total | 14 508 389 | 12 815 730 | 11 024 304 | 428 | |

| Pooled all Nordic countries | NP removal | 28 599 424 | 2 688 8773 | 21 946 707 | 449 |

| P removal | 9 681 321 | 8 532 481 | 8 114 136 | 598 | |

| Other treatment | 85 330 | 82 373 | 65 539 | 9 | |

| Secondary treatment | 1 013 460 | 1 116 343 | 1 279 491 | 26 | |

| Primary treatment | 1 358 383 | 1 440 331 | 1 305 402 | 148 | |

| No treatment | 640 500 | 428 468 | 430 596 | 9 | |

| Total in Nordic countries | 41378418 | 38488769 | 33141871 | 1239 |

References

- Mao, K. et al. The potential of wastewater-based epidemiology as surveillance and early warning of infectious disease outbreaks. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 17, 1–7 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Bibby, K., Bivins, A., Wu, Z. & North, D. Making waves: Plausible lead time for wastewater based epidemiology as an early warning system for COVID-19. Water Res. 202, 117438 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A., Radu, E., Kreuzinger, N., Ahmed, W. & Pitkänen, T. Key considerations for pathogen surveillance in wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 945, 173862 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Hokajärvi, A.-M. et al. Occurrence of thermotolerant Campylobacter spp. and adenoviruses in Finnish bathing waters and purified sewage effluents. J. Water Health 11, 120–134 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y. et al. Screening priority indicator pollutants in full-scale wastewater treatment plants by non-target analysis. J. Hazard. Mater. 414, 125490 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A. et al. Antibiotic resistance monitoring in wastewater in the Nordic countries: A systematic review. Environ. Res. 246, 118052 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Khan, F. A., Söderquist, B. & Jass, J. Prevalence and Diversity of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Swedish Aquatic Environments Impacted by Household and Hospital Wastewater. Front. Microbiol. 10, 688 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A. et al. Detection and quantification of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater influent in relation to reported COVID-19 incidence in Finland. Water Res. 215, 118220 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M. et al. Response of wastewater-based epidemiology predictor for the second wave of COVID-19 in Ahmedabad, India: A long-term data Perspective. Environ. Pollut. 337, 122471 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Tandukar, S. et al. Long-term longitudinal monitoring of SARS CoV-2 in urban rivers and sewers of Nepal. Sci. Total Environ. 951, 175138 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Ryerson, A. B. et al. Wastewater Testing and Detection of Poliovirus Type 2 Genetically Linked to Virus Isolated from a Paralytic Polio Case — New York, March 9–October 11, 2022. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 71, 1418–1424 (2022).

- Hovi, T. et al. Role of environmental poliovirus surveillance in global polio eradication and beyond. Epidemiol. Infect. 140, 1–13 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Whitehouse, E. R. et al. Wastewater Surveillance for Poliovirus in Selected Jurisdictions, United States, 2022–2023. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 30, (2024). [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, S., Malla, B. & Haramoto, E. Estimation of Norovirus infections in Japan: An application of wastewater-based epidemiology for enteric disease assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 912, 169334 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Markt, R. et al. Expanding the Pathogen Panel in Wastewater Epidemiology to Influenza and Norovirus. Viruses 15, 263 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Oghuan, J. et al. Wastewater analysis of Mpox virus in a city with low prevalence of Mpox disease: an environmental surveillance study. Lancet Reg. Health - Am. 28, 100639 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A. et al. Monkeypox outbreak: Wastewater and environmental surveillance perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 856, 159166 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Lehto, K.-M. et al. Wastewater-based surveillance is an efficient monitoring tool for tracking influenza A in the community. Water Res. 257, 121650 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A. et al. Phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of beta-lactamase dominant with CARBA, AmpC, and ESBL-producing bacteria in municipal wastewater influent in Helsinki, Finland. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 33, 345–352 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Heljanko, V. et al. Clinically relevant sequence types of carbapenemase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae detected in Finnish wastewater in 2021–2022. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 13, 14 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Gunnar, T. & Kankaanpää, A. Application of wastewater-based epidemiology for estimating population-wide human exposure to phthalate esters, bisphenols, and terephthalic acid. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 9, 49–57 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Bowes, D. A. et al. Integrated multiomic wastewater-based epidemiology can elucidate population-level dietary behaviour and inform public health nutrition assessments. Nat. Food 4, 257–266 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Parkins, M. D. et al. Wastewater-based surveillance as a tool for public health action: SARS-CoV-2 and beyond. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 37, e00103-22 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Driver, E. M., Gushgari, A. J., Steele, J. C., Bowes, D. A. & Halden, R. U. Assessing population-level stress through glucocorticoid hormone monitoring in wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 838, 155961 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Kelkar, V., Driver, E. M., Bienenstock, E. J., Palladino, A. & Halden, R. U. Stability of human stress hormones and stress hormone metabolites in wastewater under oxic and anoxic conditions. Sci. Total Environ. 857, 159377 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R., Adhikari, S., Driver, E., Zevitz, J. & Halden, R. U. Application of wastewater-based epidemiology for estimating population-wide human exposure to phthalate esters, bisphenols, and terephthalic acid. Sci. Total Environ. 847, 157616 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Wastewater: Wastewater Treatmentin Sweden 2020. (Naturvårdsverket, Stockholm, 2022).

- Mazumder, P. et al. Association of microplastics with heavy metals and antibiotic resistance bacteria/genes in natural ecosystems - A perspective through science mapping approach. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 22, 100962 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Caucci, S. et al. Seasonality of antibiotic prescriptions for outpatients and resistance genes in sewers and wastewater treatment plant outflow. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 92, fiw060 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Gao, X. et al. The proliferation of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) and microbial communities in industrial wastewater treatment plant treating N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) by AAO process. PLOS ONE 19, e0299740 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Bartkova, S., Kahru, A., Heinlaan, M. & Scheler, O. Techniques Used for Analyzing Microplastics, Antimicrobial Resistance and Microbial Community Composition: A Mini-Review. Front. Microbiol. 12, 603967 (2021). [CrossRef]

- EC. DIRECTIVE (EU) 2024/3019 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 27 November 2024 concerning urban wastewater treatment. Off. J. Eur. Union 2024/3019, (2024).

- Time, M. S. & Veggeland, F. Adapting to a Global Health Challenge: Managing Antimicrobial Resistance in the Nordics. Polit. Gov. 8, 53–64 (2020). [CrossRef]

- SYKE. Yhdyskuntajätevesien aiheuttama vesistökuormitus. Yhdyskuntajätevesien aiheuttama vesistökuormitus https://www.vesi.fi/vesitieto/yhdyskuntajatevesien-aiheuttama-vesistokuormitus/ (2022).

- NEA. Wastewater treatment plants. Wastewater treatment plants https://www.norskeutslipp.no/en/Wastewater-treatment-plants-/?SectorID=100 (2025).

- Danish EPA. Waste Water. Waste Water https://eng.mst.dk/water/waste-water (2025).

- eurostat. Population connected to at least secondary wastewater treatment. Population connected to at least secondary wastewater treatment https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/sdg_06_20/default/table?lang=en (2024).

- UWWTP. Total number of treatment plants and treatment of entering load. Total number of treatment plants and treatment of entering load https://tableau-public.discomap.eea.europa.eu/views/UWWTP/Plantstotals?%3Adisplay_count=n&%3Aembed=y&%3AisGuestRedirectFromVizportal=y&%3Aorigin=viz_share_link&%3AshowAppBanner=false&%3AshowVizHome=n (2024).

- Katko, T. S., Juuti, P. S., Juuti, R. P. & Nealer, E. J. Managing Water and Wastewater Services in Finland, 1860–2020 and Beyond. Earth 3, 590–613 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Bach, L. et al. Wet wipes in untreated wastewater are a source of litter pollution to the arctic marine environment – a case study on the loads of litter and microplastics in wastewater effluents in Greenland. Environ. Sci. Adv. 10.1039.D4VA00233D (2025). [CrossRef]

- Erland Jensen, P. et al. Plastic in Raw Wastewater in Greenland. (Nordic Council of Ministers, 2024). [CrossRef]

- Dam, M. et al. Micropollutants in Wastewater in Four Arctic Cities - Is the Treatment Sufficient? (Nordic Council of Ministers, Copenhagen, 2017). [CrossRef]

- Laukka Vuokko et al. Governance of on-site sanitation in Finland, Sweden and Norway. (2022).

- Heinonen-Tanski, H. & Matikka, V. Chemical and Microbiological Quality of Effluents from Different On-Site Wastewater Treatment Systems across Finland and Sweden. Water 9, 47 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Paruch, A. M. et al. Rural domestic wastewater treatment in Norway and Poland: experiences, cooperation and concepts on the improvement of constructed wetland technology. Water Sci. Technol. 63, 776–781 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Andersson, J. L., Bastviken, S. K. & Tonderski, K. S. Free water surface wetlands for wastewater treatment in Sweden: nitrogen and phosphorus removal. Water Sci. Technol. 51, 39–46 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Heen, Aleksander Oren. Government Feedback on the Revision of the Urban Wastewater Treatment Directive. State Secretary, Royal Norwegian Ministry of Climate and Environment. 6 https://norskvann.no/wp-content/uploads/Norske-Myndigheter.pdf (2023).

- Magnusson, K., Hrönn Jörundsdóttir, Norén, F., & Hywel Lloyd. Microlitter in Sewage Treatment Systems : A Nordic Perspective on Waste Water Treatment Plants as Pathways for Microscopic Anthropogenic Particles to Marine Systems. (Nordic Council of Ministers, 2016).

- Kommunia Qeqqata. Technical Infrastructure. Sisimiut - Installations https://pilersaarut.qeqqata.gl/dk/byer-og-bygder/sisimiut/tekniske-anlaeg/.

- Rita Obrist. Microbial risk assessment of wastewater in Sisimiut, Greenland: Health risks and mitigation options. (Norwegian University of Science and Technology, 2024).

- Länsivaara, A. et al. Wastewater-Based Surveillance of Respiratory Syncytial Virus Epidemic at the National Level in Finland. ACS EST Water 4, 2403–2411 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A. et al. Wastewater surveillance of antibiotic-resistant bacterial pathogens: A systematic review. Front. Microbiol. 13, 977106 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Sarekoski, A. et al. Simultaneous biomass concentration and subsequent quantitation of multiple infectious disease agents and antimicrobial resistance genes from community wastewater. Environ. Int. 191, 108973 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Sif Guðjónsdóttir. Membrane-based Decentralized Wastewater Treatment and Reuse in Icelandic Scenario. (University of Iceland, Faculty of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Reykjavik, Iceland, 2021).

- Kinnunen, J., Rossi, P. M., Herrmann, I., Ronkanen, A.-K. & Heiderscheidt, E. Factors affecting effluent quality in on-site wastewater treatment systems in the cold climates of Finland and Sweden. J. Clean. Prod. 404, 136756 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Johannesdottir, S. L. et al. Sustainability assessment of technologies for resource recovery in two Baltic Sea Region case-studies using multi-criteria analysis. Clean. Environ. Syst. 2, 100030 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A. et al. Bacterial diversity and predicted enzymatic function in a multipurpose surface water system – from wastewater effluent discharges to drinking water production. Environ. Microbiome 16, 11 (2021). [CrossRef]

- EEC. COUNCIL DIRECTIVE of 21 May 1991 Concerning Urban Waste Water Treatment (9 1 /271 /EEC). vol. 30. 5. 91 (1991).

- European Communities. DIRECTIVE 2000/60/EC OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 23 October 2000 establishing a framework for Community action in the field of water policy. Off. J. Eur. Communities L 327/1, 1–72 (2000).

- EUROPEAN COUNCIL. DIRECTIVE 2006/7/EC OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 15 February 2006 concerning the management of bathing water quality and repealing Directive 76/160/EEC. Off. J. Eur. Union L 64/37, 1–15 (2006).

- Tiwari, A. et al. Effects of temperature and light exposure on the decay characteristics of fecal indicators, norovirus, and Legionella in mesocosms simulating subarctic river water. Sci. Total Environ. 859, 160340 (2023). [CrossRef]

| Country | Population (growth rate prediction in 2024) | Number of cities with a population of over 20,000; and over 5,000 | Total number of centralized WWTP | Number of WWTP with primary treatment | Number of WWTP with primary and secondary treatment | % of population coverage | The principle of WWTP establish | Majorly drive for treatment plant establishment | Major challenges in centralized WWTPs | Others |

| Finland (EU-member country) |

5.62 million (0.29 %) | 56; 209 | 360 | 100 % | 100 % | 89 | Legislation, population size, industrial needs, and protection of vulnerable areas like groundwater sources. | Wastewater treatment in Finland is regulated by the EU Urban Wastewater Treatment Directive, the National Environmental Act, and municipal laws. | Aging infrastructure. | Finland has 100 % sanitation coverage |

| Iceland (EEA-member country) |

0.39 million (1.51 %) | 3; 8 | 15 | 80 | 4 | 90 | Legislation, population size, industrial needs, and protection of vulnerable areas like groundwater sources. | Wastewater treatment in Iceland is regulated by the EU Urban Wastewater Treatment Directive. | Local cold climate & oligotrophic Atlantic justify the lack of WWTPs. The government subsidizes WWTPs in small cities. | |

| Norway (EEA-member country) | 5.59 million (1.04 %) | 25; 91 | 16 | 100 | 90 | - | Legislation, population size, industrial needs, and protection of vulnerable areas like groundwater sources. | EU Urban Wastewater Treatment Directive & National Pollution Control Regulations but lacks specific local regulations for smaller plants. | Local cold climate & oligotrophic Atlantic justify the lack of WWTPs. | |

| Sweden (EU-member country) | 10.61 million (0.53 %) | 78; 272 | 1700 | 100 | 100 | 90 | Legislation, population size, industrial needs, and protection of vulnerable areas like groundwater sources | The EU Urban Wastewater Treatment Directive, National Pollution Control Regulations, and local permits &, regional conditions. | Small sewage volumes and limited budgets are major challenges in small communities. | Sweden adheres to the Polluter Pays principle uniformly across all WWTPs. |

| Faroe Island (Do not comply with EU rules and regulations) | 55,400 (1.25%) | 1; 2 | Does not have any modern treatment plants and sanitation is managed by septic tanks. | - | Environmental regulations are relatively soft, guided by national Law. | Population and national environmental regulations. | National environmental regulations. | Lack of strict environmental law, limited municipal budgets, low population coverage, & oligotrophic Atlantic as cost-effective dilution. | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).