Submitted:

24 April 2025

Posted:

24 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods.

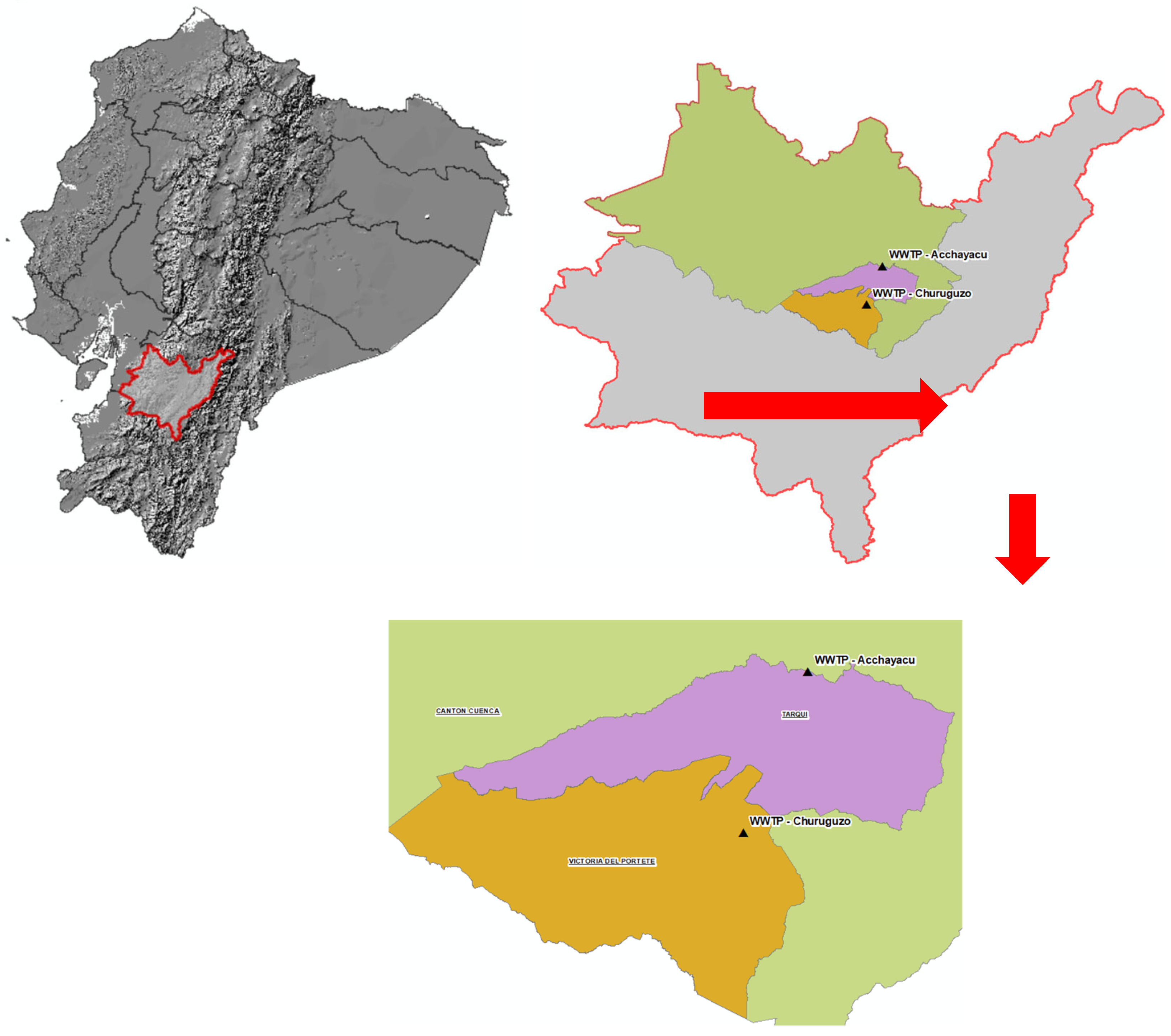

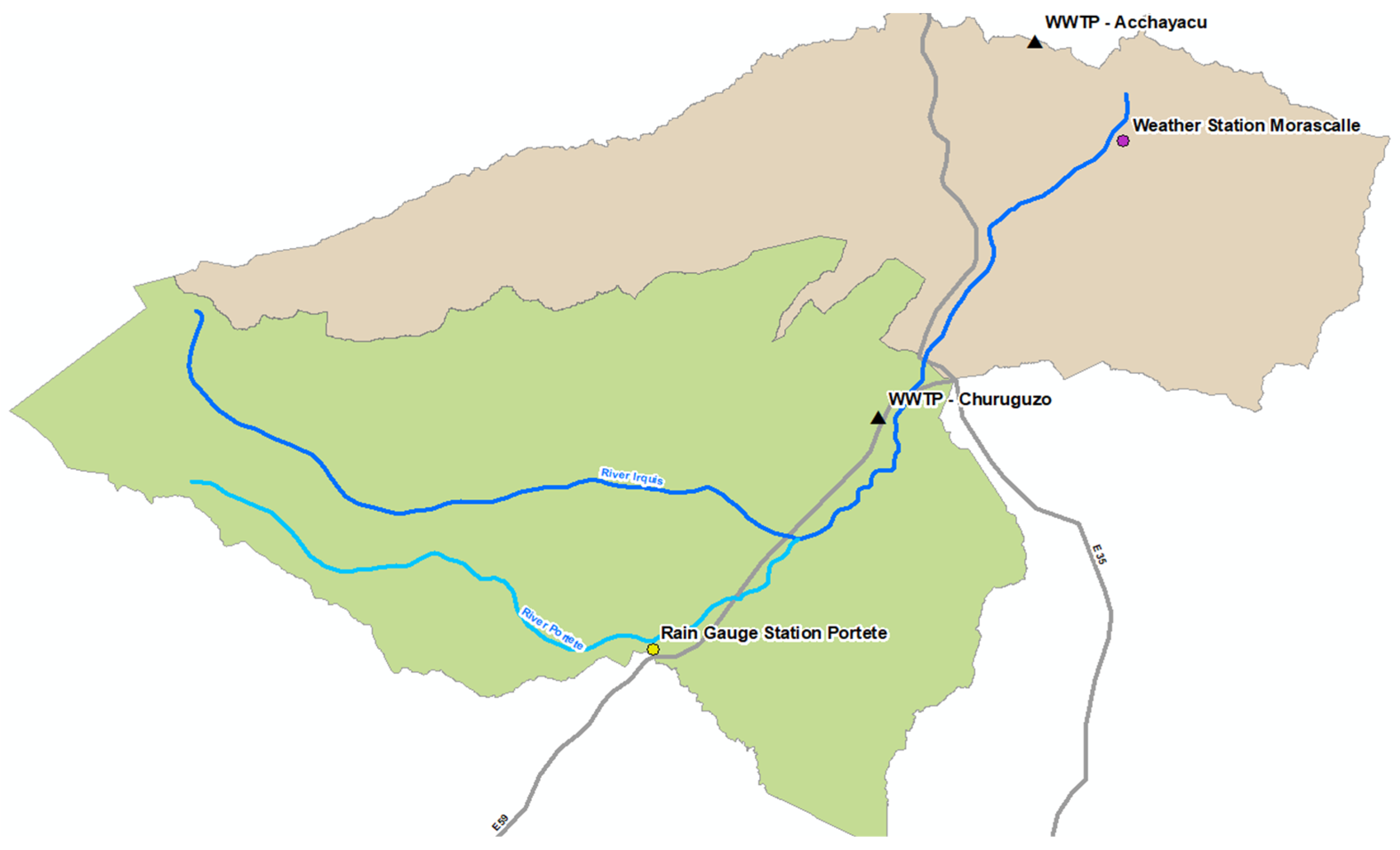

2.1. Ubications of the WWTPs.

2.2. Climate Analysis of the Study Areas

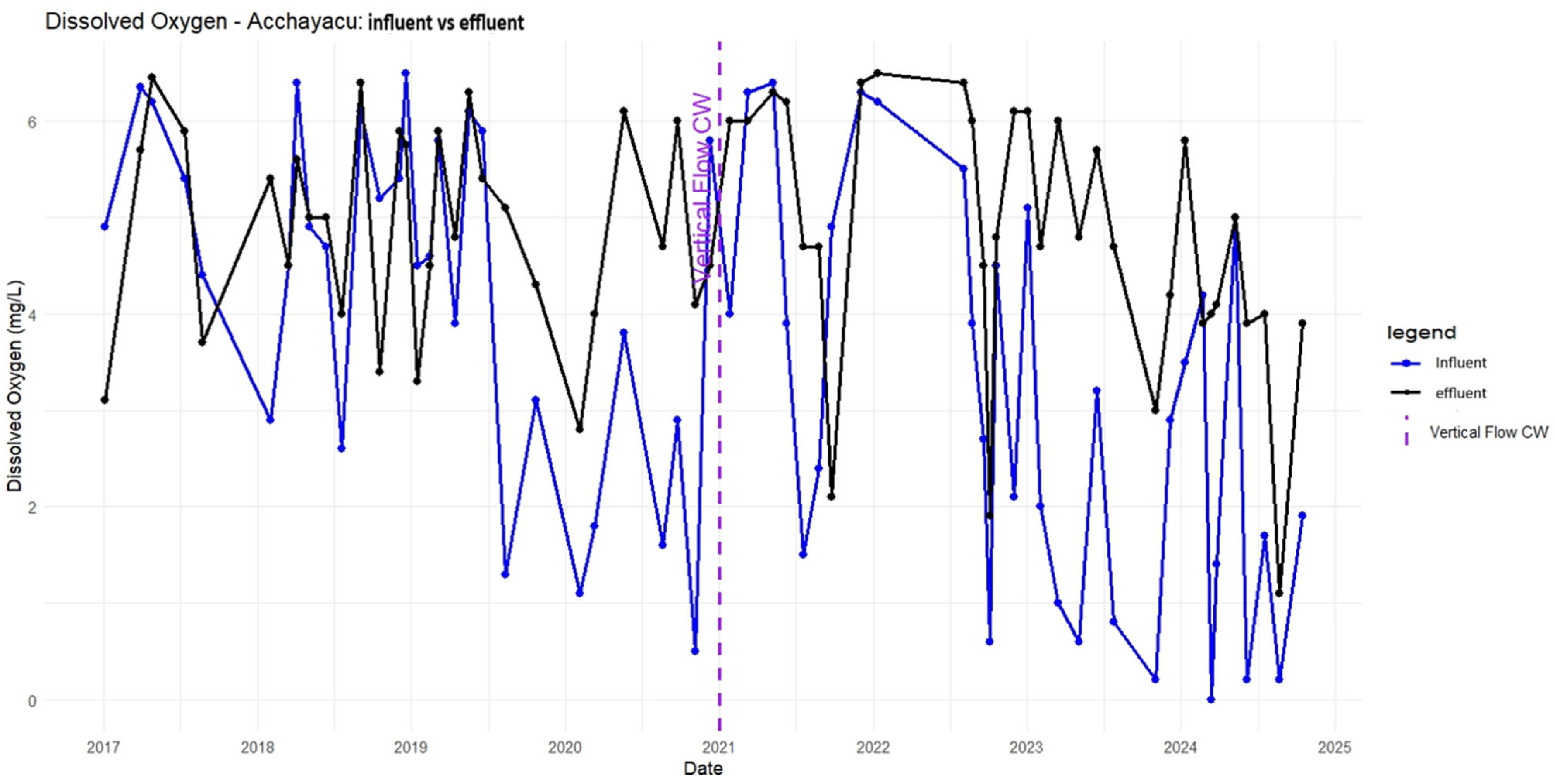

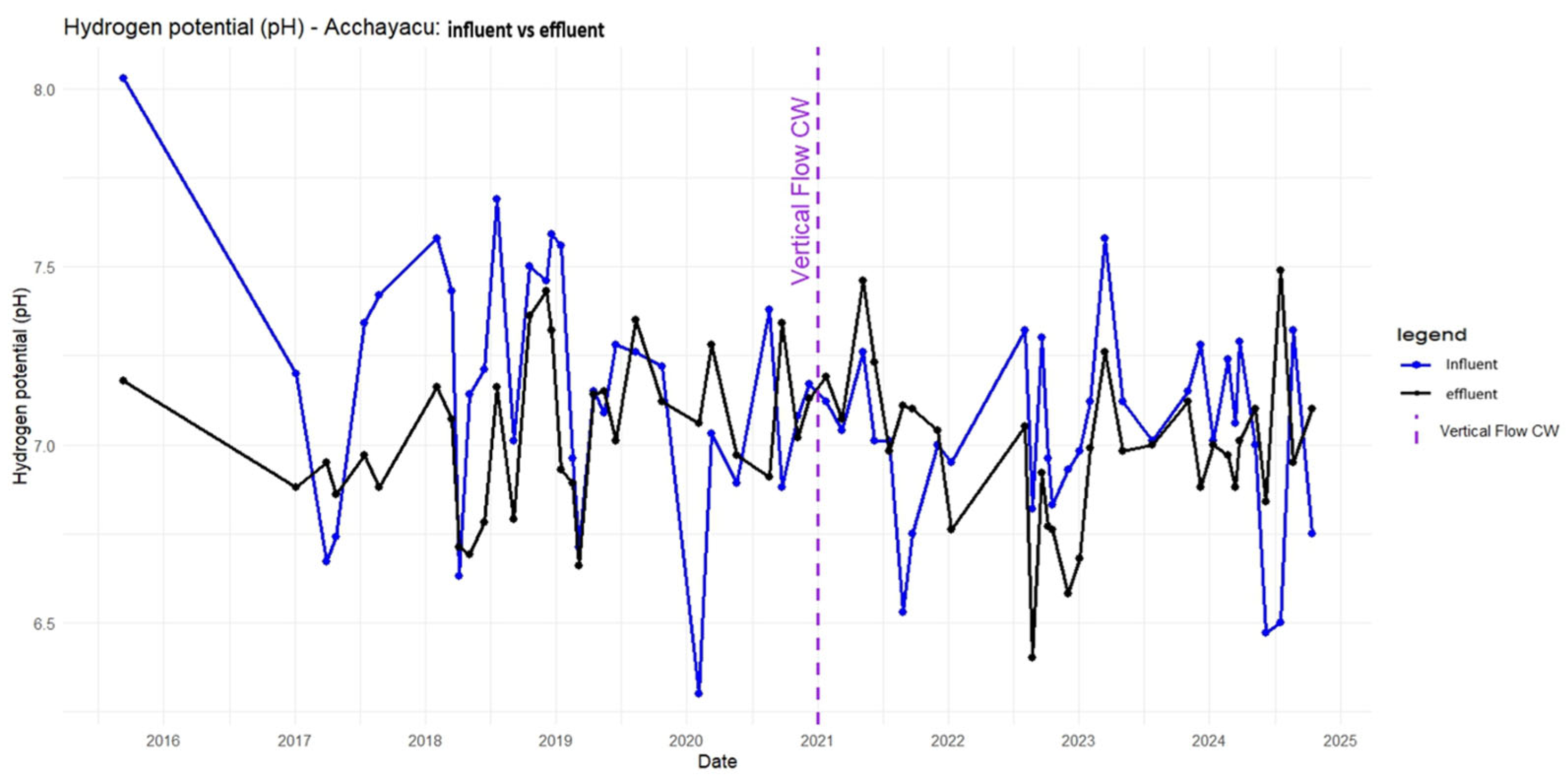

2.3. Analysis of Operating Parameters in Constructed Wetlands

2.4. Sampling and Analyzed Parameters

2.5. Comparison of Pollutant Removals Between WWTPs

3. Results

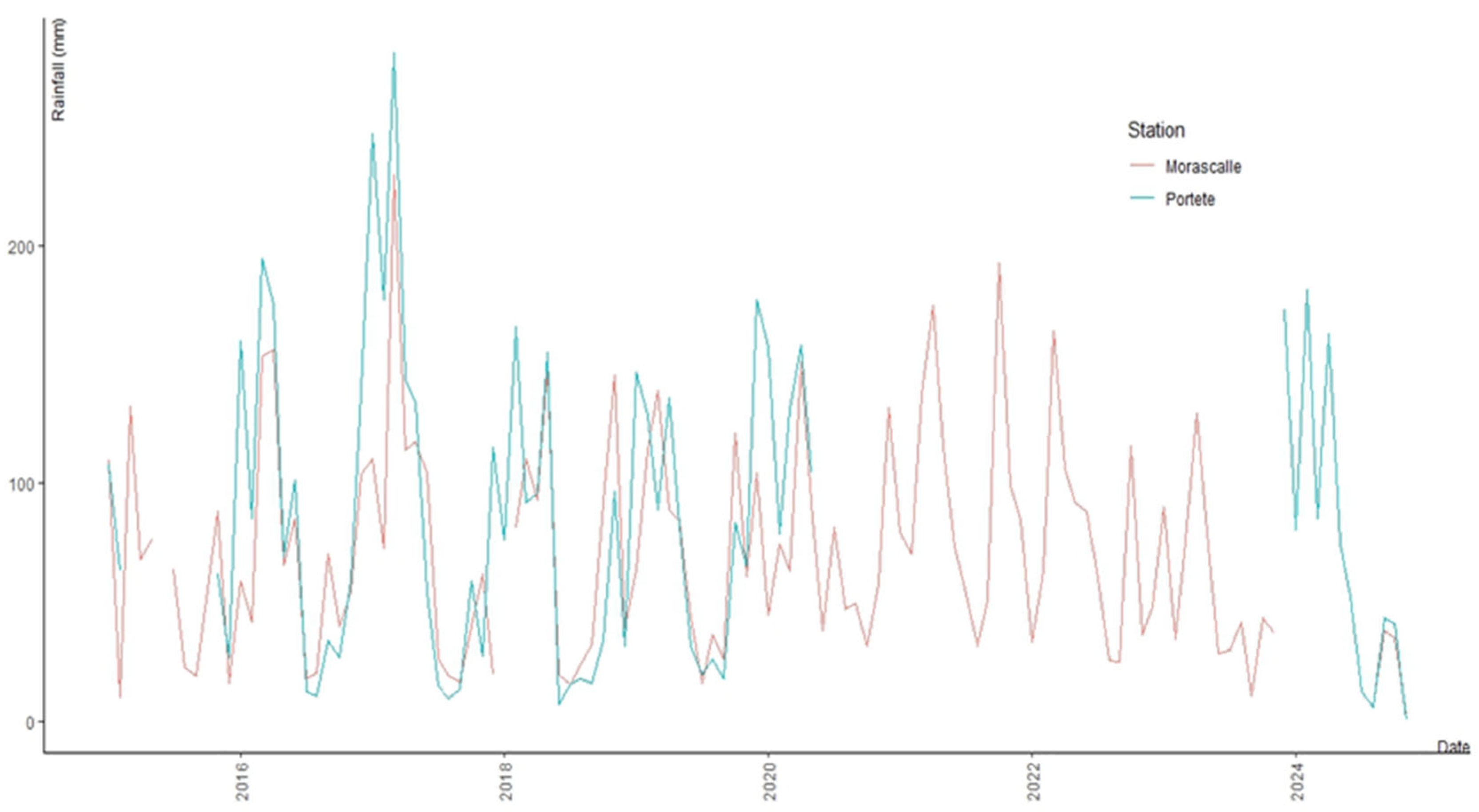

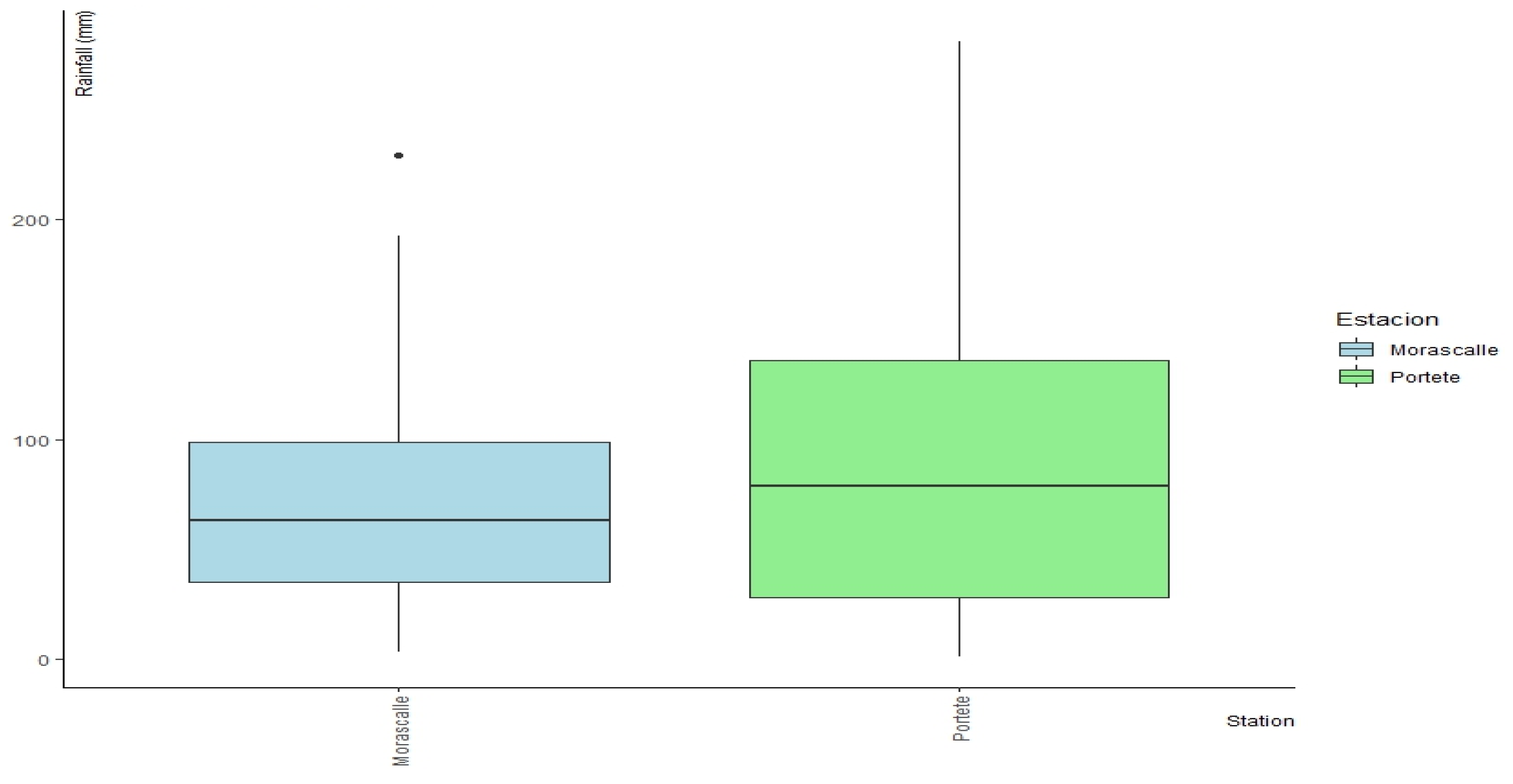

3.1. Analysis of meteorological parameters.

3.2. Comparison of Removal Efficiency Between Treatment Technologies

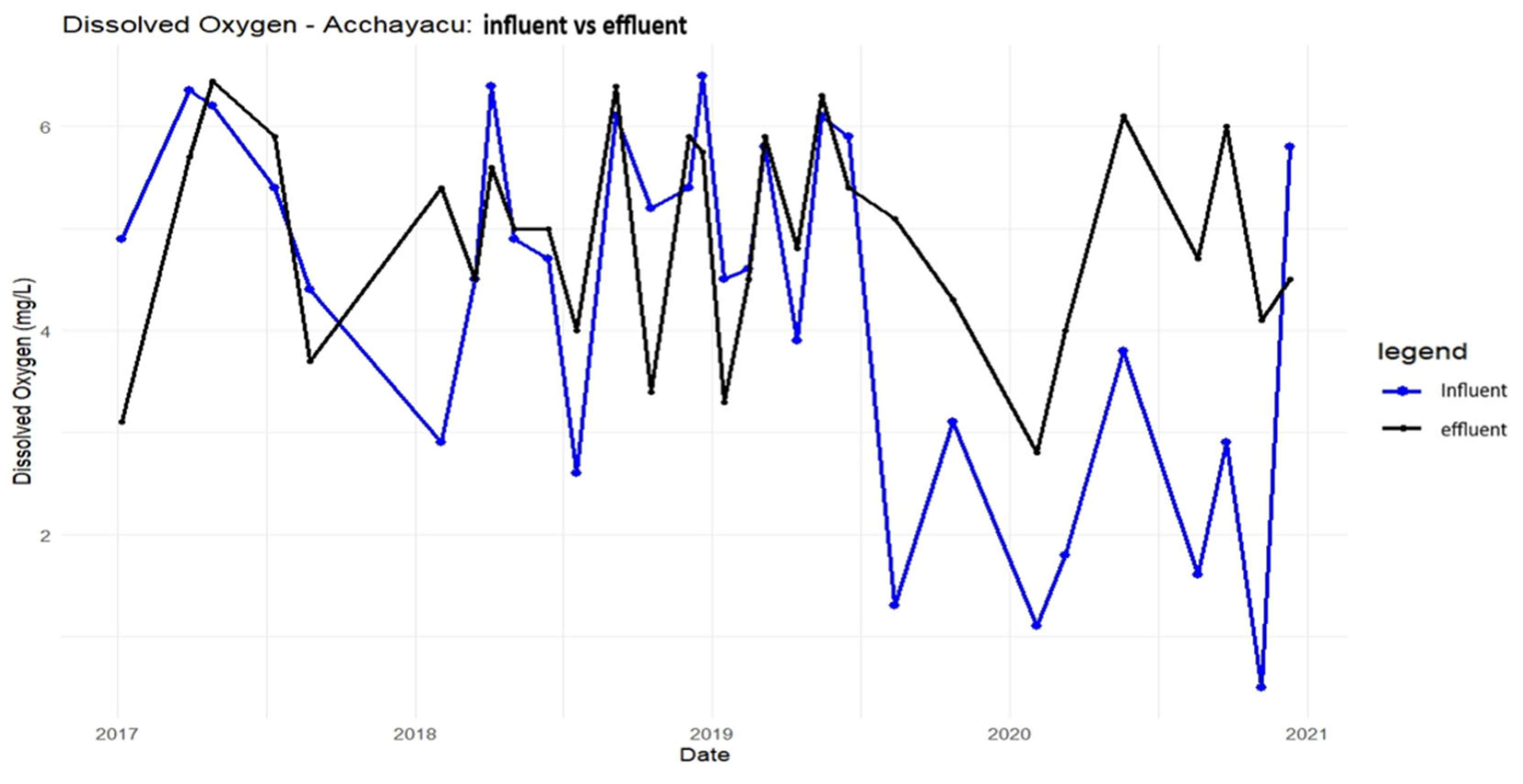

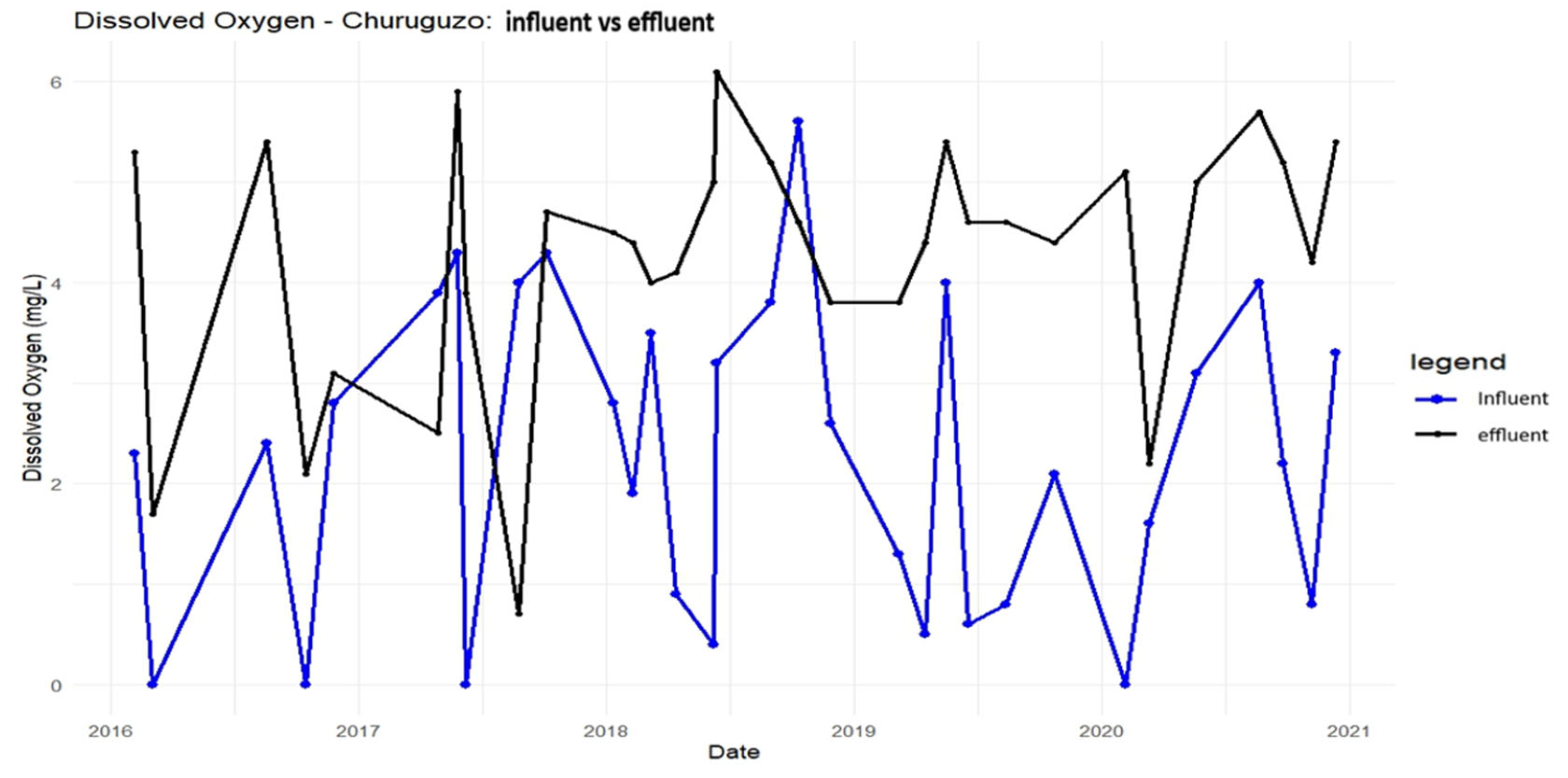

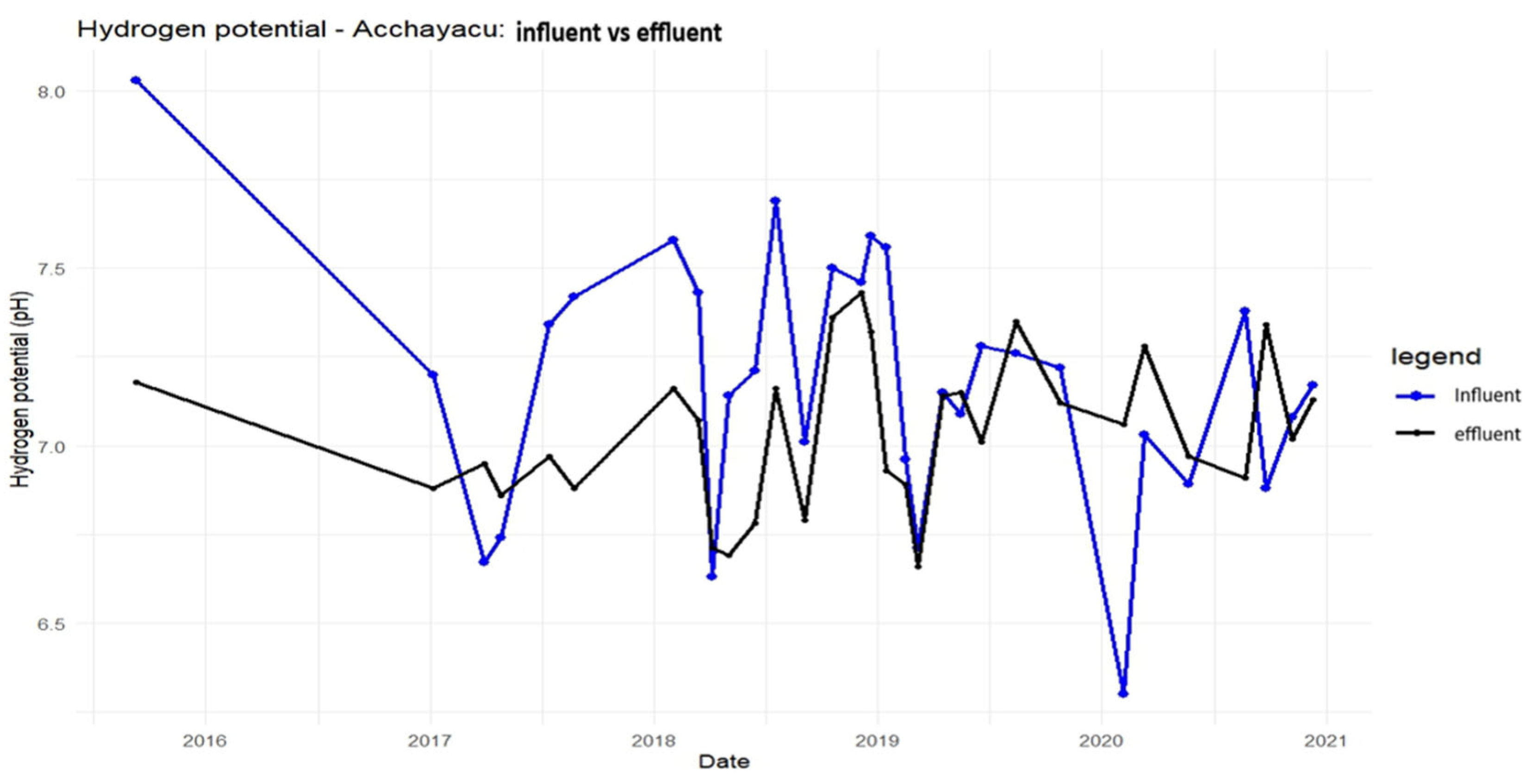

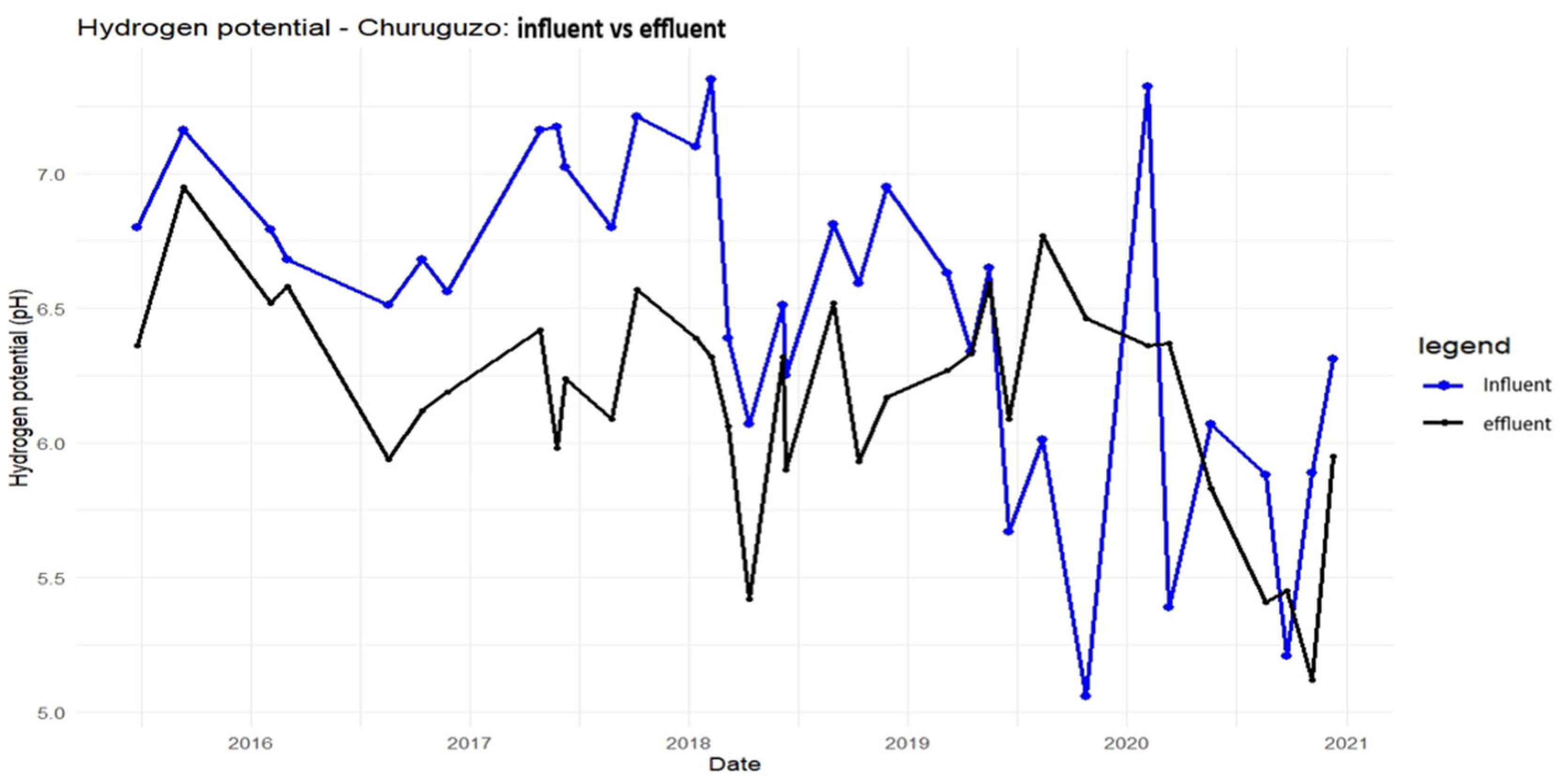

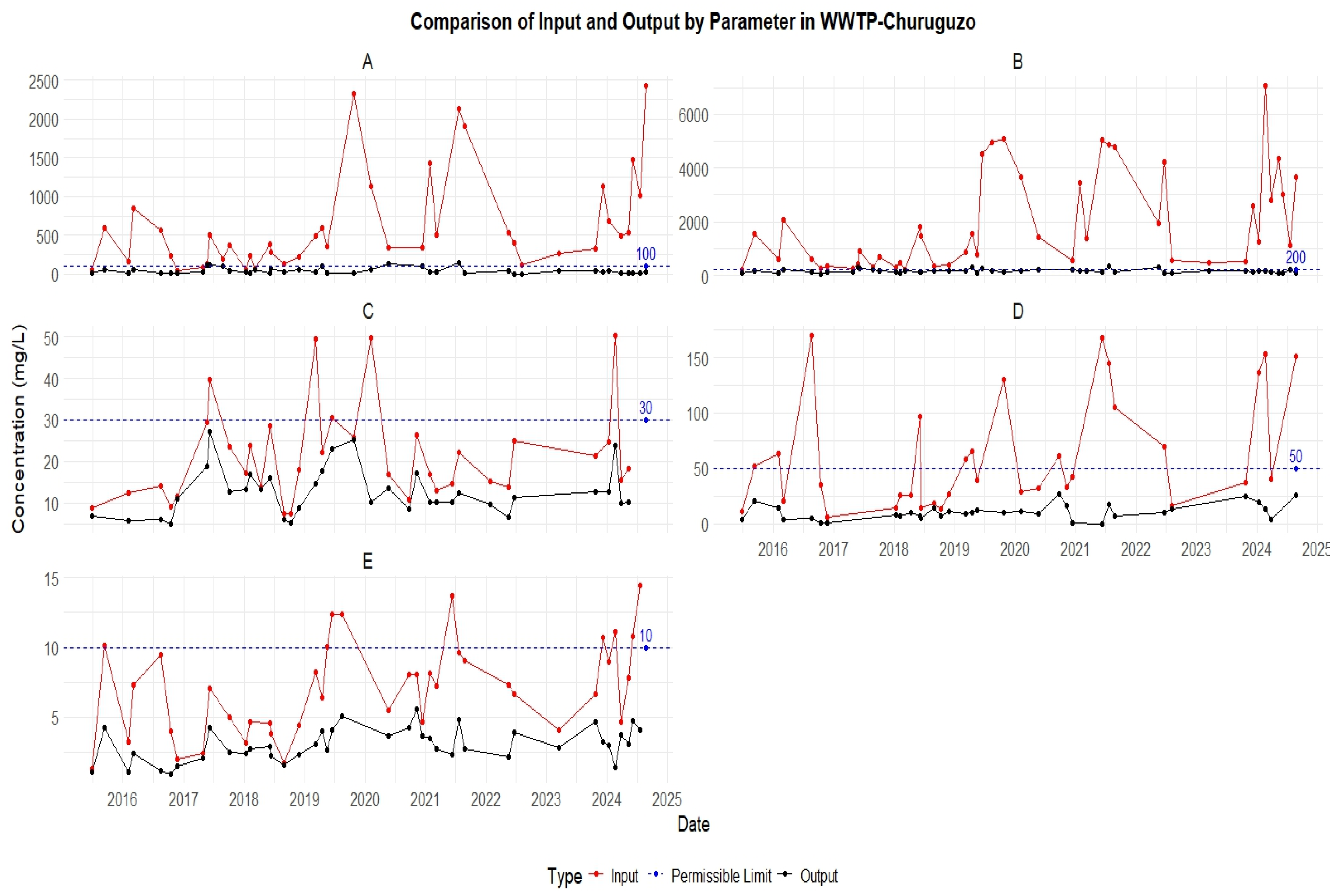

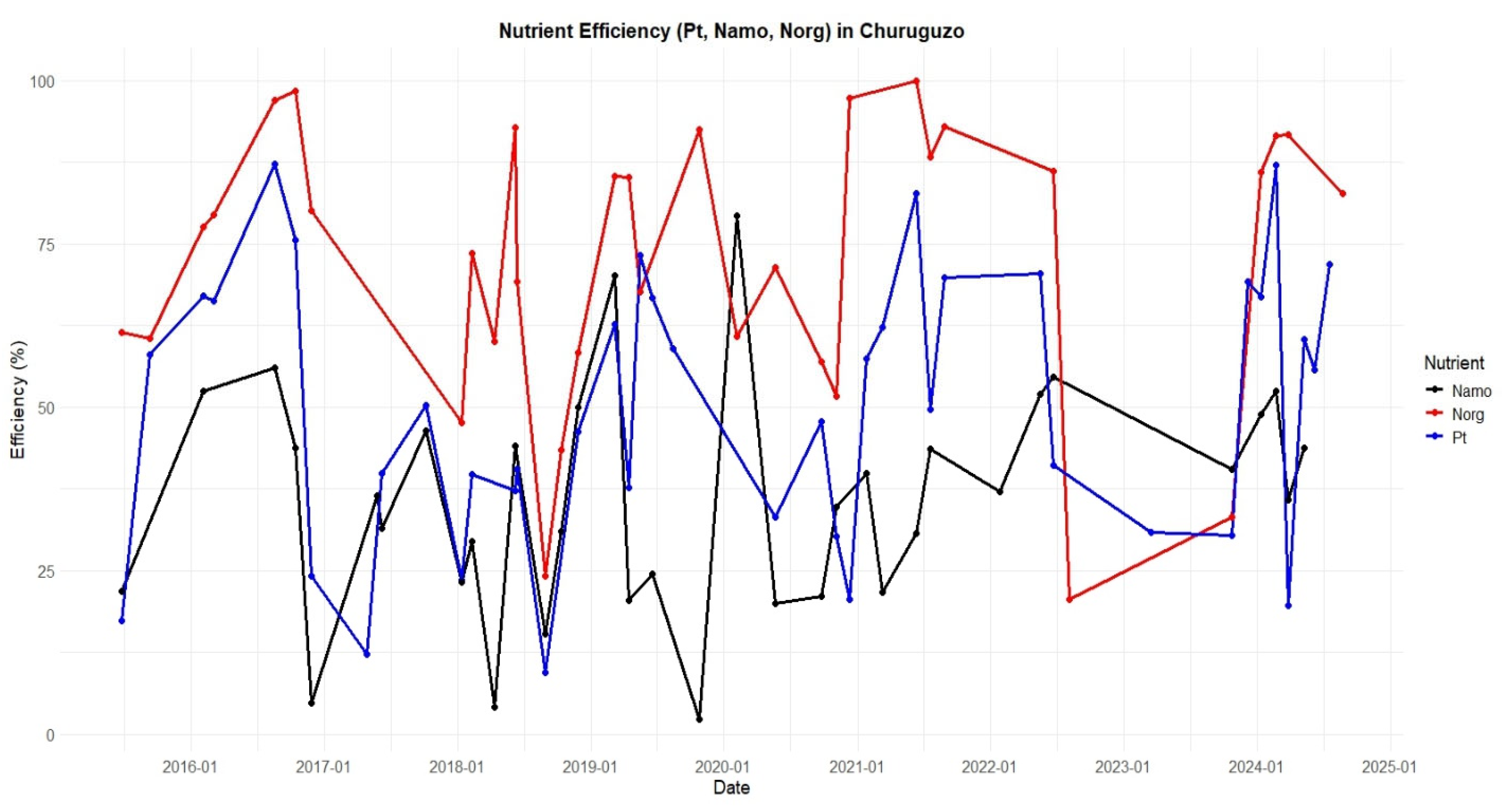

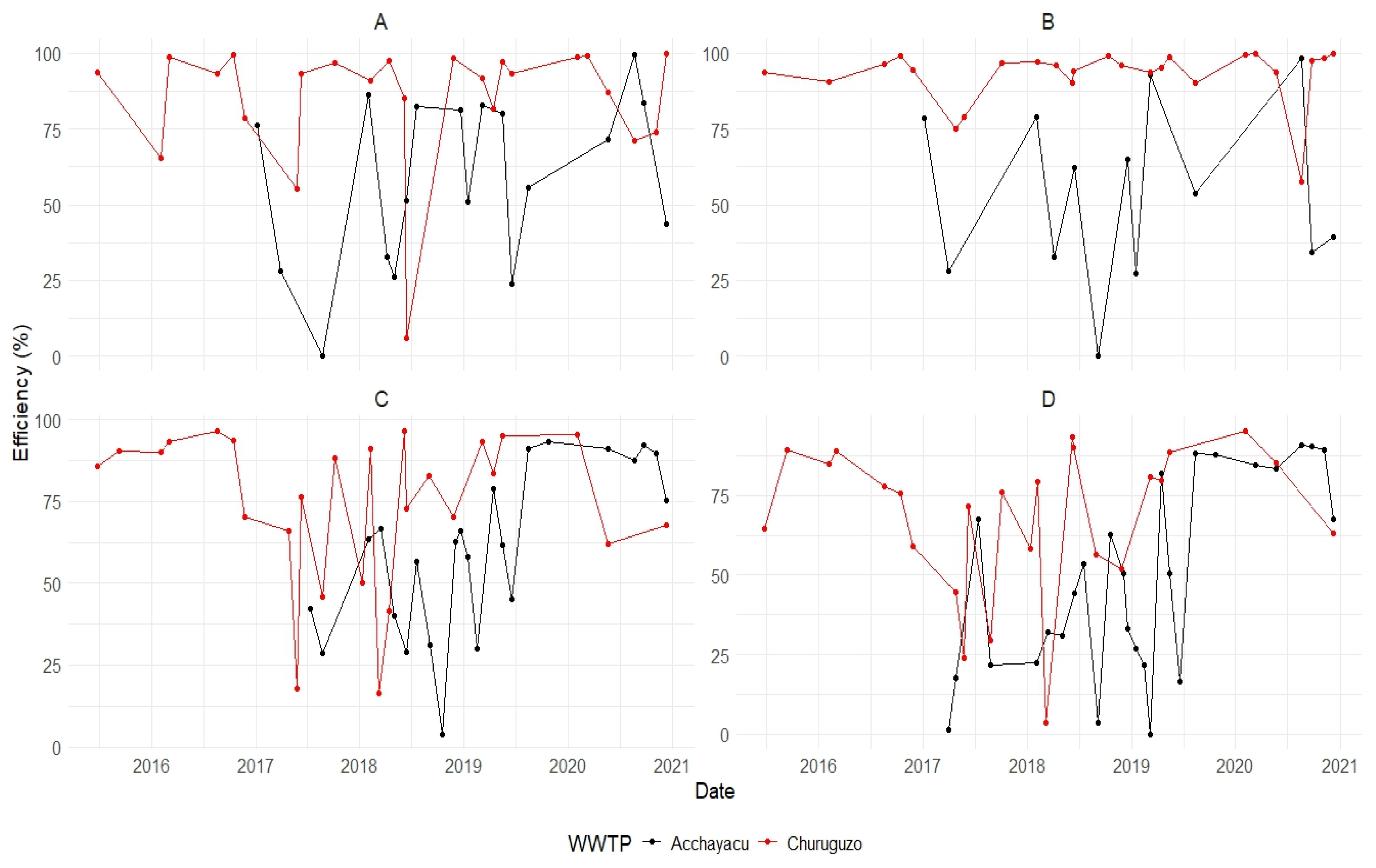

3.2.1. Efficiency Comparison of the Upflow Anaerobic filter (UAF) at the Acchayacu WWTP and the Surface Flow Constructed Wetland (SF-CW) at the Churuguzo WWTP During the Period 2015 – 2020.

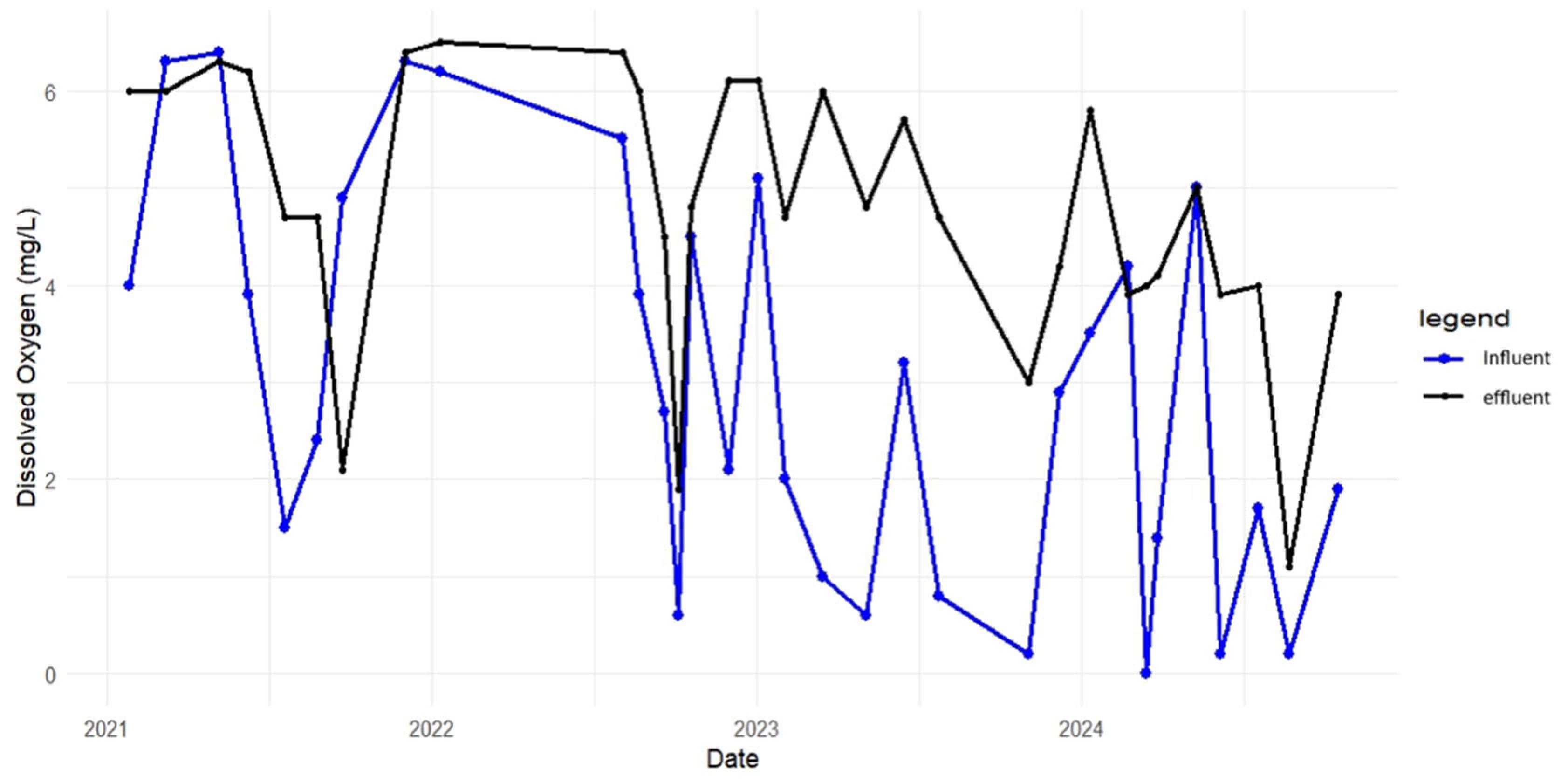

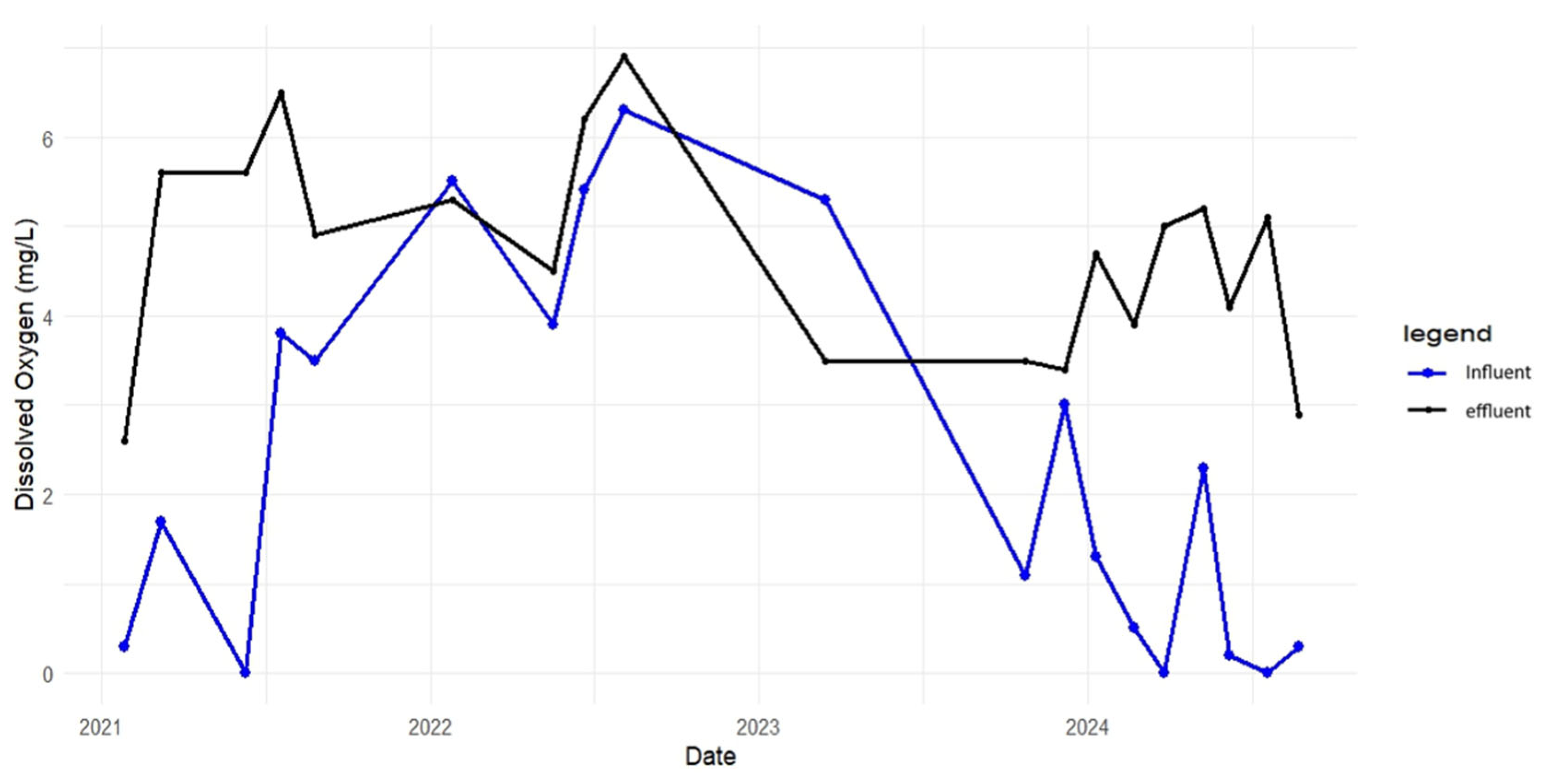

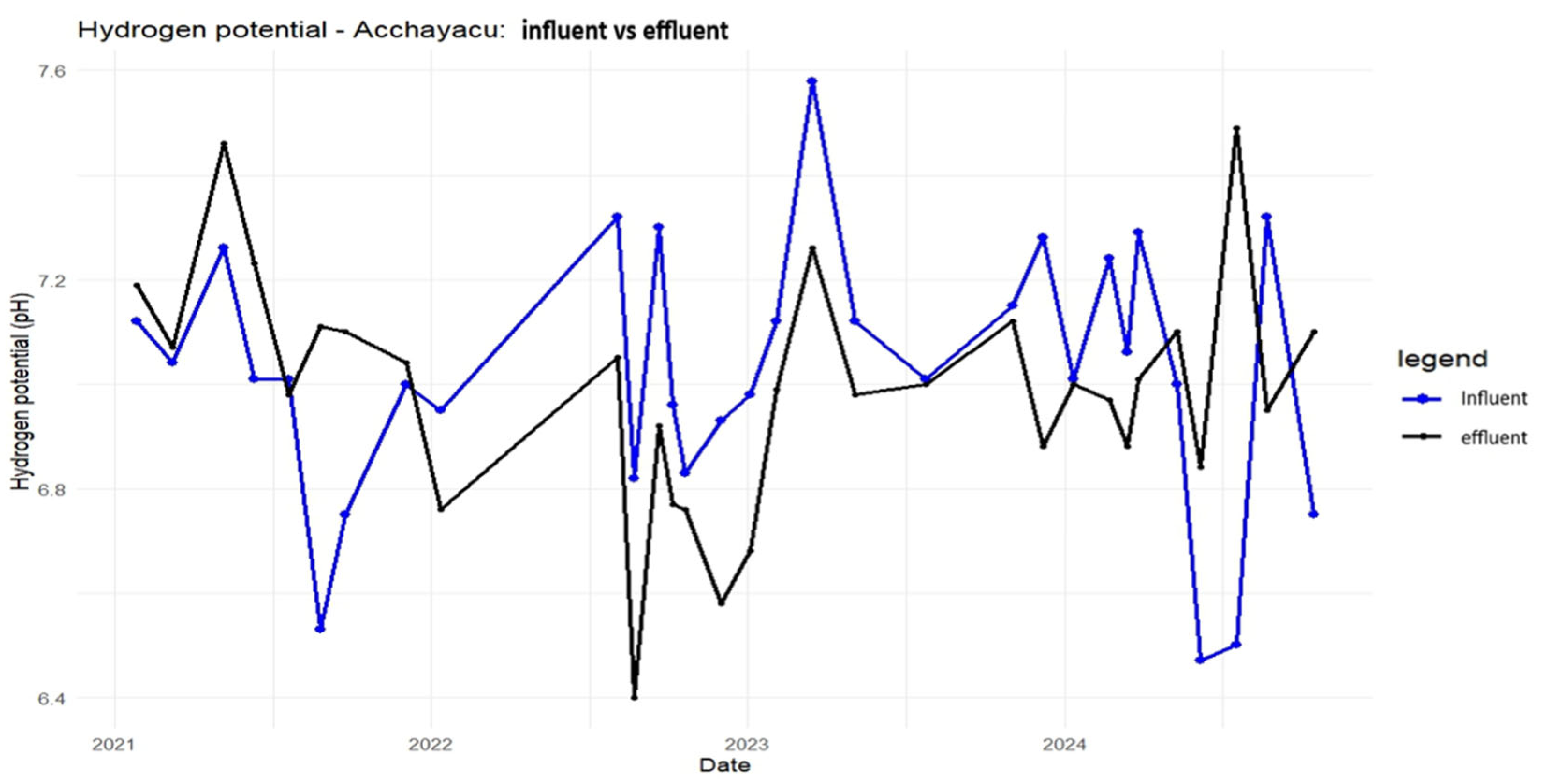

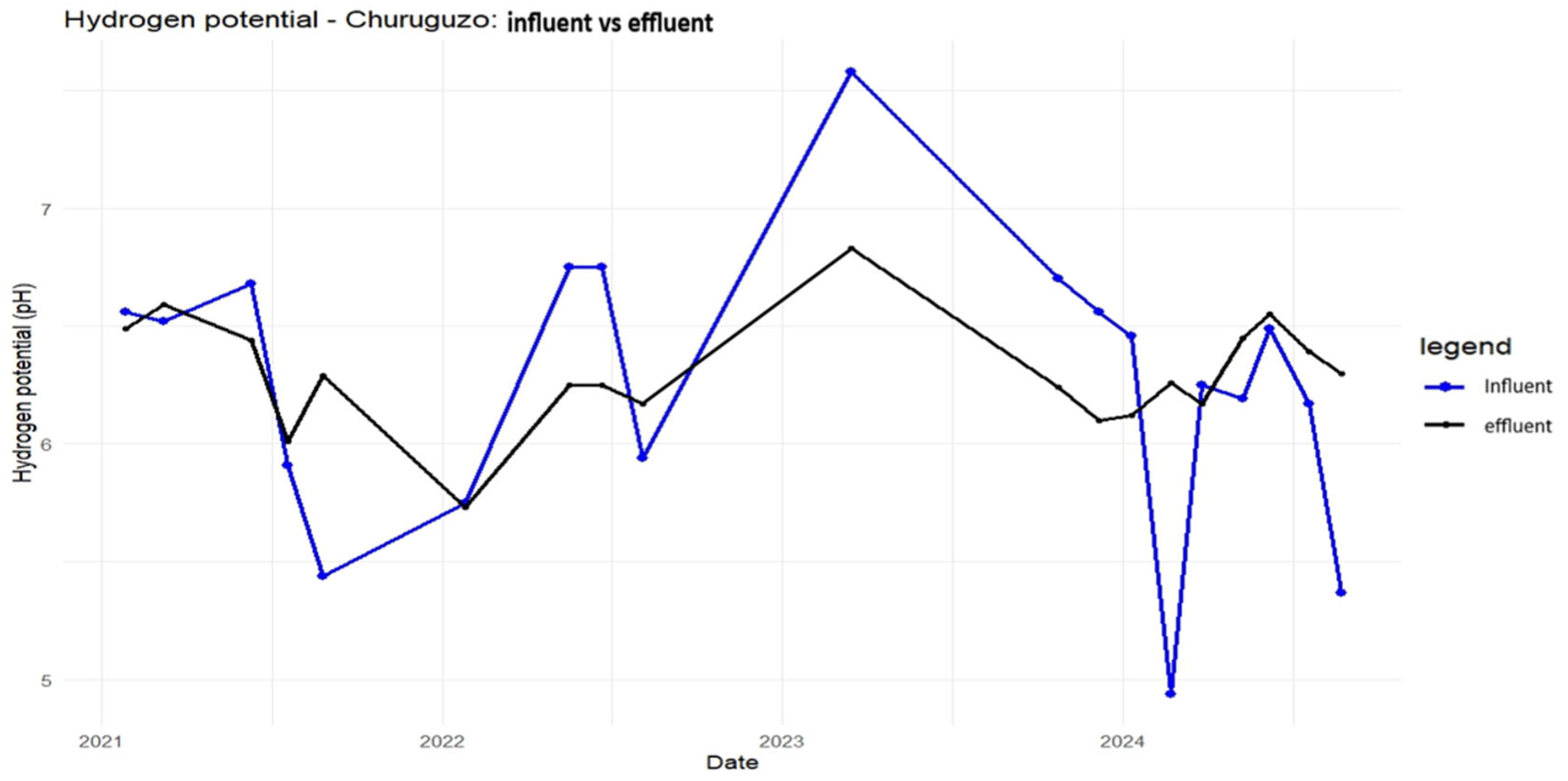

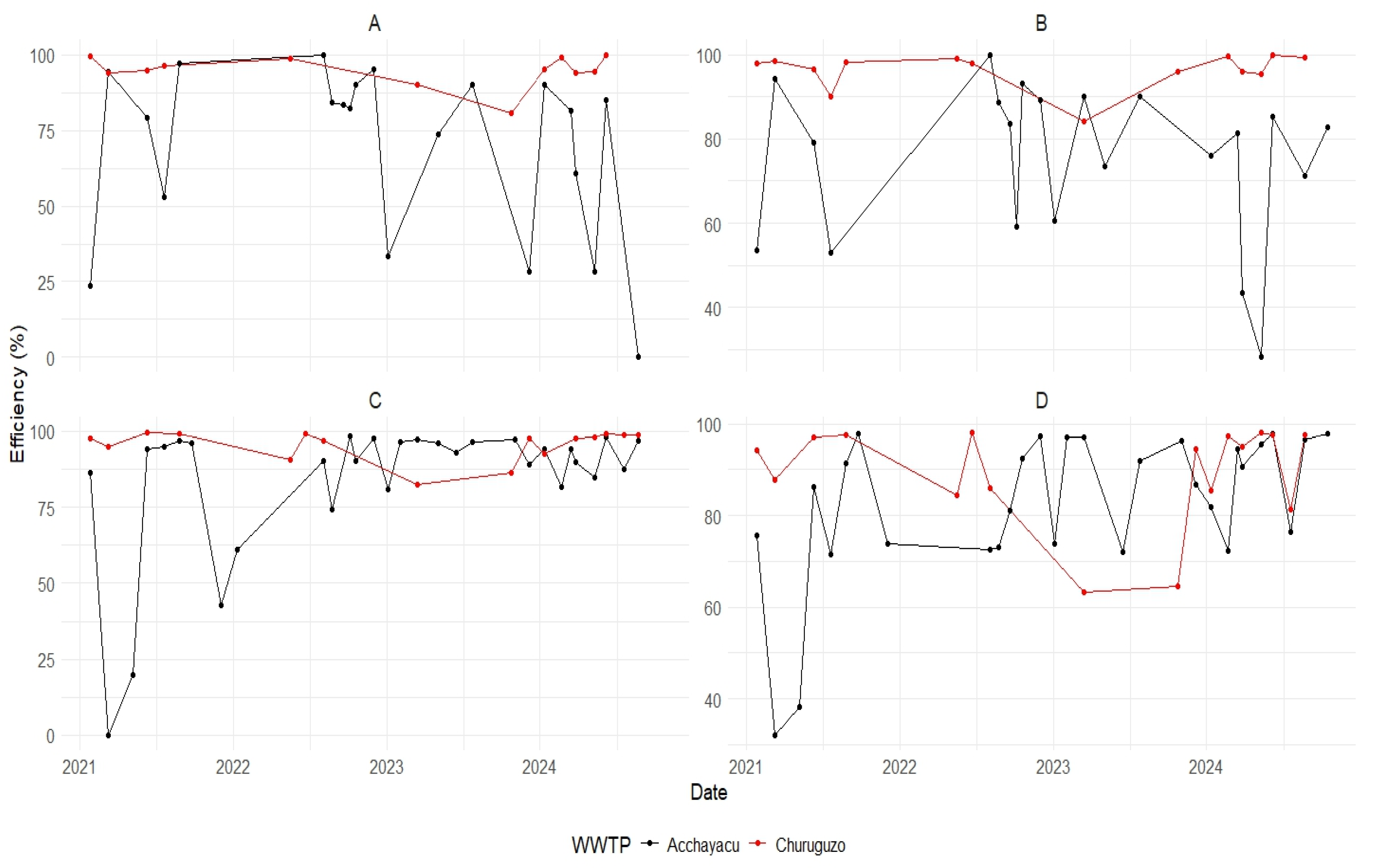

3.2.2. Efficiency Comparison of Two Constructed Wetlands Types at the Acchayacu and Churuguzo Wwtps During the Period 2021 - 2024.

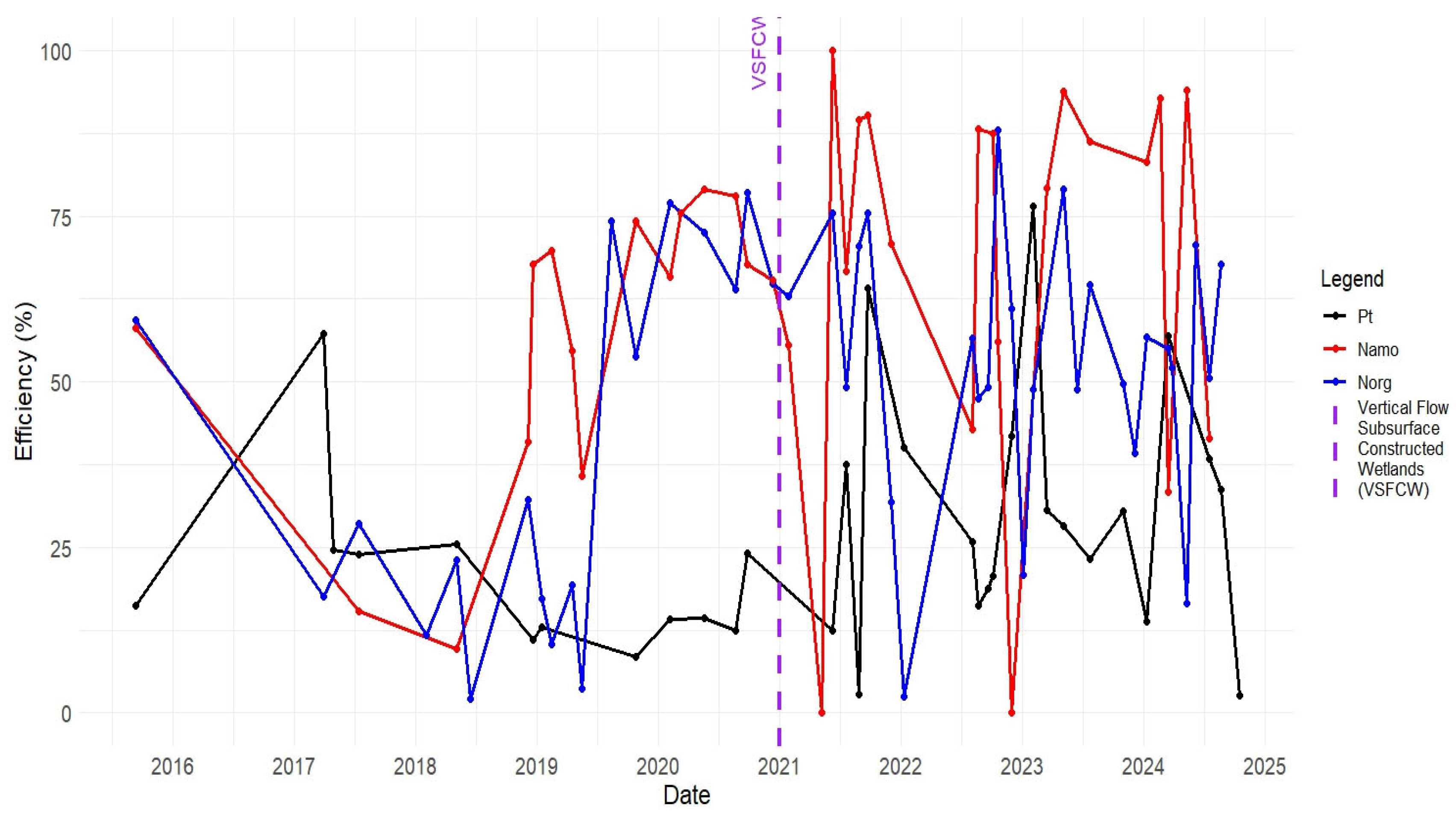

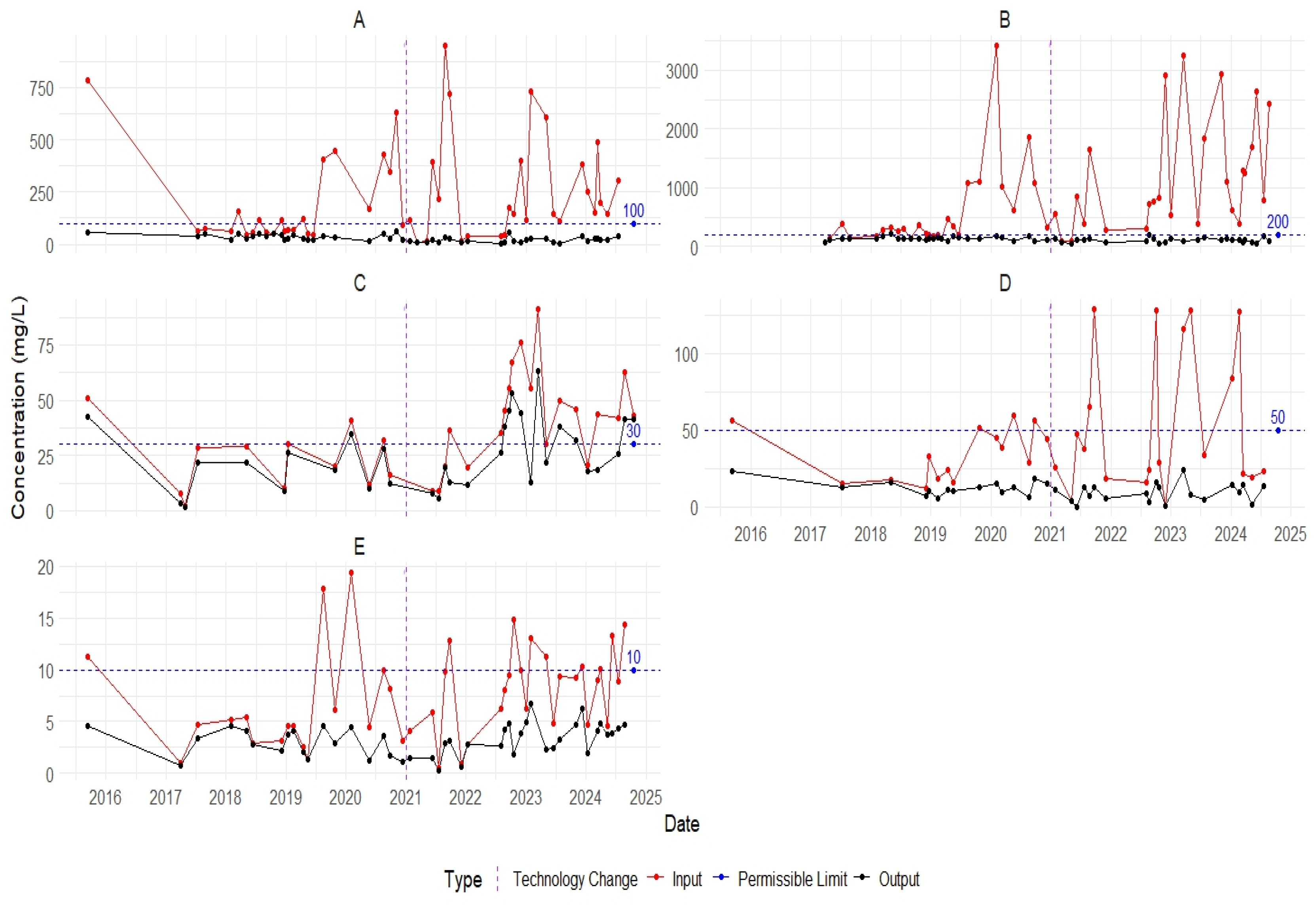

3.2.3. Comparison Between Different Treatment Technologies of the WWTP of Acchayacu.

4. Discussion

- Analysis of meteorological parameters

- Analysis of hydraulic parameters

- Comparative analysis of removal efficiency between SF-CW and VSSF-CW.

- Influence of technological change

- Implications and limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Appendix A

References

- Coello, E.; Burbano, I.; Molina, A. , “Factores contaminantes del río San Pablo de la ciudad de Babahoyo, Ecuador,” Estudios del Desarrollo Social: Cuba y América Latina, vol. 11, pp. 20–26, 2023.

- Metcalf & Eddy, INC. Ingeniería de Aguas Residuales. Tratamiento, Vertido y Reutilización, 3rd ed., vol. 1. Madrid: Impresos y Revistas, S. A. (IMPRESA), 1995.

- Hanjra, M.A.; Blackwell, J.; Carr, G.; Zhang, F.; Jackson, T.M. , “Wastewater irrigation and environmental health: Implications for water governance and public policy,” Int J Hyg Environ Health, vol. 215, no. 3, pp. 255–269, Apr. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Humanante, J.; Moreno, L.; Grijalva, A.; Saldoya, R.; Suárez, J. , “Removal Efficiency and impact of wastewater treatment system in the urban and rural sector of the Santa Elena Province,” Manglar, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 177–187, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Rojas, J.A.R. , Tratamiento de aguas residuales. Teoría y principios de diseño, 3rd ed., vol. 1. Bogotá: Nuevas Ediciones S.A, 2000.

- Jerves-Cobo, R.; et al. , “Biological water quality in tropical rivers during dry and rainy seasons: A model-based analysis,” Ecol Indic, vol. 108, p. 105769, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Chung, G.; et al. , “A general water supply planning model: Evaluation of decentralized treatment,” Environmental Modelling & Software, vol. 23, no. 7, pp. 893–905, Jul. 2008. . https://doi.org/. [CrossRef]

- Llagas, W.; Gómez, E.G. , “Diseño de humedales artificiales para el tratamiento de aguas residuales en la UNMSM,” Revista del Instituto de Investigaciones FIGMMG, vol. 15, pp. 85–96, 2006.

- Anil, A.; et al. , “Constructed Wetland for Low- Cost Waste Water Treatment,” Int J Sci Res Sci Eng Technol, pp. 328–334, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Rizaldi, M.A.; Limantara, L.M. , “Wetland as revitalization pond at urban area based on the eco hydrology concept,” International Journal of Engineering & Technology, vol. 7, no. 3.29, p. 143, Aug. 2018. . https://doi.org/. [CrossRef]

- Delgadillo, O.; Camacho, A.; Pérez, L.F.; Andrade, M. , Depuración de aguas residuales por medio de humedales artificiales, Nelson Antequera. Cochabamba – Bolivia: Centro Andino para la Gestión y Uso del Agua (Centro AGUA), 2010.

- Wijaya, I.M.W.; Soedjono, E.S. , “Physicochemical Characteristic of Municipal Wastewater in Tropical Area: Case Study of Surabaya City, Indonesia,” IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci, vol. 135, p. 012018, Mar. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Isaza, C.A.A. , “ Humedales Artificiales Para el Tratamiento de Aguas Residuales.,” Revista Científica General José María Córdova, vol. 3, pp. 40–44, 2005, Accessed: Dec. 31, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa? 4762. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz, A.J.D.-G.; Paredes, P.M.P.-R. , “Aprovechamiento de aguas residuales domésticas tratadas mediante el uso de un humedal artificial de piñón y girasol,” Polo del Conocimiento, vol. 7, pp. 1478– 1495, 2022, Accessed: Dec 31, 2024 [Online] Available: https://polodelconocimientocom/ojs/indexphp/es/article/view/3556. [Google Scholar]

- EPA, “Subsurface Flow Constructed Wetlands For WasteWater Treatment A Technology Assessment,” 1993.

- Aguado, R.; Parra, O.; García, L.; Manso, M.; Urkijo, L.; Mijangos, F. , “Modelling and simulation of subsurface horizontal flow constructed wetlands,” Journal of Water Process Engineering, vol. 47, p. 102676, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Córdova, M.; Paz, D.; Santelices, M. , Gobernanza para monitorear el acceso al saneamiento en Ecuador. FLACSO Ecuador, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Terán, C.; Argüello, J.; Cando, C. , “Boletín Técnico Estadística de Información Ambiental Económica en Gobiernos Autónomos Descentralizados Municipales, Gestión de Agua Potable y Saneamiento 2022,” Dec. 2023, Dirección de Estadísticas Agropecuarias y Ambientales - DEAGA, Quito.

- Jerves-Cobo, R.; et al. , “Integrated ecological modelling for evidence-based determination of water management interventions in urbanized river basins: Case study in the Cuenca River basin (Ecuador),” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 709, p. 136067, Mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Operacz, A.; Jóźwiakowski, K.; Rodziewicz, J.; Janczukowicz, W.; Bugajski, P. , “Impact of Climate Conditions on Pollutant Concentrations in the Effluent from a One-Stage Constructed Wetland: A Case Study,” Sustainability, vol. 15, no. 17, p. 13173, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, J.S.; Loaiza, D.C.R.; Asprilla, W.J. , “Humedales artificiales subsuperficiales: comparación de metodologías de diseño para el cálculo del area superficial basado en la remoción de la materia organica,” Ingenierías USBMed, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 65–73, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R Core Team, “R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing,” Nov. 2024, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria: 4.4.2.

- Cantelmo, N.F.; Ferreira, D.F. , “Desempenho de testes de normalidade multivariados avaliado por simulação Monte Carlo,” Ciência e Agrotecnologia, vol. 31, no. 6, pp. 1630–1636, Dec. 2007. [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.A.; Ahmad, F. , “Power Comparison of Various Normality Tests,” Pakistan Journal of Statistics and Operation Research, vol. 11, no. 3, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Saculinggan, M.; Balase, E.A. , “Empirical Power Comparison Of Goodness of Fit Tests for Normality In The Presence of Outliers,” J Phys Conf Ser, vol. 435, p. 012041, Apr. 2013. [CrossRef]

- De La Mora-Orozco, C.; Saucedo-Terán, R.A.; González-Acuña, I.J.; Gómez-Rosales, S.; Flores-López, H.E. , “Efecto de la temperatura del agua sobre la constante de velocidad de reacción de los contaminantes en un humedal construido para el tratamiento de aguas residuales porcícolas,” Rev Mex Cienc Pecu, vol. 11, pp. 1–17, Mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Buytaert, W.; Celleri, R.; Willems, P.; De Bièvre, B.; Wyseure, G. , “Spatial and temporal rainfall variability in mountainous areas: A case study from the south Ecuadorian Andes,” J Hydrol (Amst), vol. 329, no. 3–4, pp. 413–421, Oct. 2006. [CrossRef]

- Navarro, L.; Torres, J.; Carlos, R. , “Revisión de los impactos en la calidad del agua subterránea generados por humedales artificiales en zonas rurales,” Desarrollo e Innovación en Ingeniería, vol. 2, pp. 10–24, 2021.

- EPA, “Wastewater technology fact sheet: Free water surface wetlands,” U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (EPA 832-F-00-024), 2000.

- EPA, “Folleto informativo de tecnología de aguas residuales Humedales de flujo subsuperficial,” U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA 832-R-00-023.), 2000.

- CONAGUA, Diseño de Plantas de Tratamiento de Aguas Residuales Municipales: Humedales Artificiales. Manual de Agua Potable, Alcantarillado y Saneamiento (MAPAS), libro 30. México D.F. (México): Comisión Nacional del Agua (CONAGUA), 2015.

- González, T.C.R.; Narváez, T.A.C. , “Evaluación y rediseño de la planta de tratamiento de aguas residuales Acchayacu, parroquia Tarqui, del cantón Cuenca, Ecuador,” Universidad de Cuenca, Cuenca, 2018.

- García, K.L.Q.; Zúñiga, D.P.R.; Duque, M.E.G.; Rojas, J.A.A. , “Evaluación de la remoción de nitrógeno y materia orgánica a través de humedales artificiales de flujo subsuperficial, acoplados a reactores de lecho fijo con microalgas en la Institución Universitaria Colegio Mayor de Antioquia,” Ingeniería y Región, vol. 25, pp. 82–94, 21. . https://doi.org/, 20 May. [CrossRef]

- Bedoya, J.C.; Ardila, A.N.; Reyes, J. , “Evaluación De Un Humedal Artificial De Flujo Subsuperficial En El Tratamiento De Las Aguas Residuales Generadas En La Institución Universitaria Colegio Mayor De Antioquia, Colombia.,” Revista Internacional De Contaminación Ambiental, vol. 3, pp. 275–283, 2014.

- Romero-Aguilar, M.; Colin-Cruz, A.; Sanchez-Salinas, E.; Ortiz-Hernandez, M.L. , “Tratamiento de aguas residuales por un sistema piloto de humedales artificiales: evaluación de la remoción de la carga orgánica.,” Rev. Int. Contam. Ambient, vol. 25, pp. 157–167, 2009.

- Zahraeifard, V.; Deng, Z. , “Hydraulic residence time computation for constructed wetland design,” Ecol Eng, vol. 37, no. 12, pp. 2087–2091, Dec. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Miranda, J.P.; Gómez, E.; Garavito, L.; López, F. , “Estudio de comparación del tratamiento de aguas residuales domésticas utilizando lentejas y buchón de agua en humedales artificiales.,” Tecnología y ciencias del agua, vol. 1, pp. 59–68, 2010.

- Brix, H. , “Do macrophytes play a role in constructed treatment wetlands?,” Water Science and Technology, vol. 35, no. 5, pp. 11–17, Mar. 1997. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Hu, Y.; Xie, H.; Yang, Z. , “Constructed Wetlands: A Review on the Role of Radial Oxygen Loss in the Rhizosphere by Macrophytes,” Water (Basel), vol. 10, no. 6, p. 678, 18. . https://doi.org/, 20 May. [CrossRef]

- Abdelhakeem, S.G.; Aboulroos, S.A.; Kamel, M.M. , “Performance of a vertical subsurface flow constructed wetland under different operational conditions,” J Adv Res, vol. 7, no. 5, pp. 803–814, Sep. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Anchundia, B.; Vera-Loor, J.; Loor-Vélez, J. , “Diseño de un filtro anaerobio de flujo ascendente para el tratamiento de aguas residuales,” ‘‘INGENIAR”: Ingeniería, Tecnología e Investigación, vol. 5, pp. 2–16, 2022.

- Mosquera, Y. , “Tratamiento de lixiviados mediante humedales artificiales,” Tumbaga, vol. 1, pp. 73–99, 2012.

- Zhang, D.Q.; Jinadasa, K.B.S.N.; Gersberg, R.M.; Liu, Y.; Ng, W.J.; Tan, S.K. , “Application of constructed wetlands for wastewater treatment in developing countries – A review of recent developments (2000–2013),” J Environ Manage, vol. 141, pp. 116–131, Aug. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Dotro, G.; et al. , Humedales para tratamiento, vol. 7. UK: IWA Publishing, Alliance House, 12 Caxton Street, London SW1H 0QS, UK, 2017.

- Keyport, S.; et al. , “Effects of experimental harvesting of an invasive hybrid cattail on wetland structure and function,” Restor Ecol, vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 389–398, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Arteaga-Cortez, V.M.; Quevedo-Nolasco, A.; del Valle-Paniagua, D.H.; Castro-Popoca, M.; Bravo-Vinaja, Á.; Ramírez-Zierold, J.A. , “Estado del arte: una revisión actual a los mecanismos que realizan los humedales artificiales para la remoción de nitrógeno y fósforo,” Tecnología y ciencias del agua, vol. 10, no. 5, pp. 319–342, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Guerra, J.D.T.; Vargas, J.S.M.; Aguirre, R.R.P.; Huaranga, M.A.C. , “Evaluación de la eficiencia en el tratamiento de aguas residuales para riego mediante humedales Artificiales de flujo libre superficial (FLS) con las especies Cyperus Papyrus y Phragmites Australis, en Carapongo-Lurigancho,” Revista de Investigación Ciencia, Tecnología y Desarrollo, vol. 3, no. 2, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Lahora, A. , “Depuración de aguas residuales mediante humedales artificiales: la Edarde los Gallardos (Almería,” Ecología, manejo y conservación de los humedales, vol. 49, pp. 99–112, 2003.

| Parameter | Acchayacu UAF |

Churuguzo SF-CW |

|---|---|---|

| SS | 71.79 | 83.46 |

| ST | 47.73 | 63.71 |

| BOD5 | 60.20 | 74.30 |

| COD | 48.91 | 68.44 |

| Pt | 37.23 | 45.04 |

| N_amo | 20.43 | 33.17 |

| N_org | 57.16 | 68.86 |

| TC | 58.65 | 85.24 |

| TTC | 53.18 | 92.85 |

| Parameter | Acchayacu VSSF-CW |

Churuguzo SF-CW |

|---|---|---|

| SS | 95.66 | 95.88 |

| ST | 75.20 | 83.57 |

| BOD5 | 83.90 | 95.56 |

| COD | 82.80 | 89.40 |

| Pt | 53.45 | 57.82 |

| N_amo | 30.74 | 40.77 |

| N_org | 65.87 | 71.82 |

| TC | 69.18 | 94.70 |

| TTC | 75.05 | 96.32 |

| Parameter | Acchayacu | Acchayacu |

|---|---|---|

| UAF | VSSF-CW | |

| SS | 71.79 | 95.66 |

| ST | 47.73 | 75.2 |

| BOD5 | 60.2 | 83.9 |

| COD | 48.91 | 82.8 |

| Pt | 37.23 | 53.45 |

| N_amo | 20.43 | 30.74 |

| N_org | 57.16 | 65.87 |

| TC | 58.65 | 69.18 |

| TTC | 53.18 | 75.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).