Submitted:

26 September 2023

Posted:

27 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

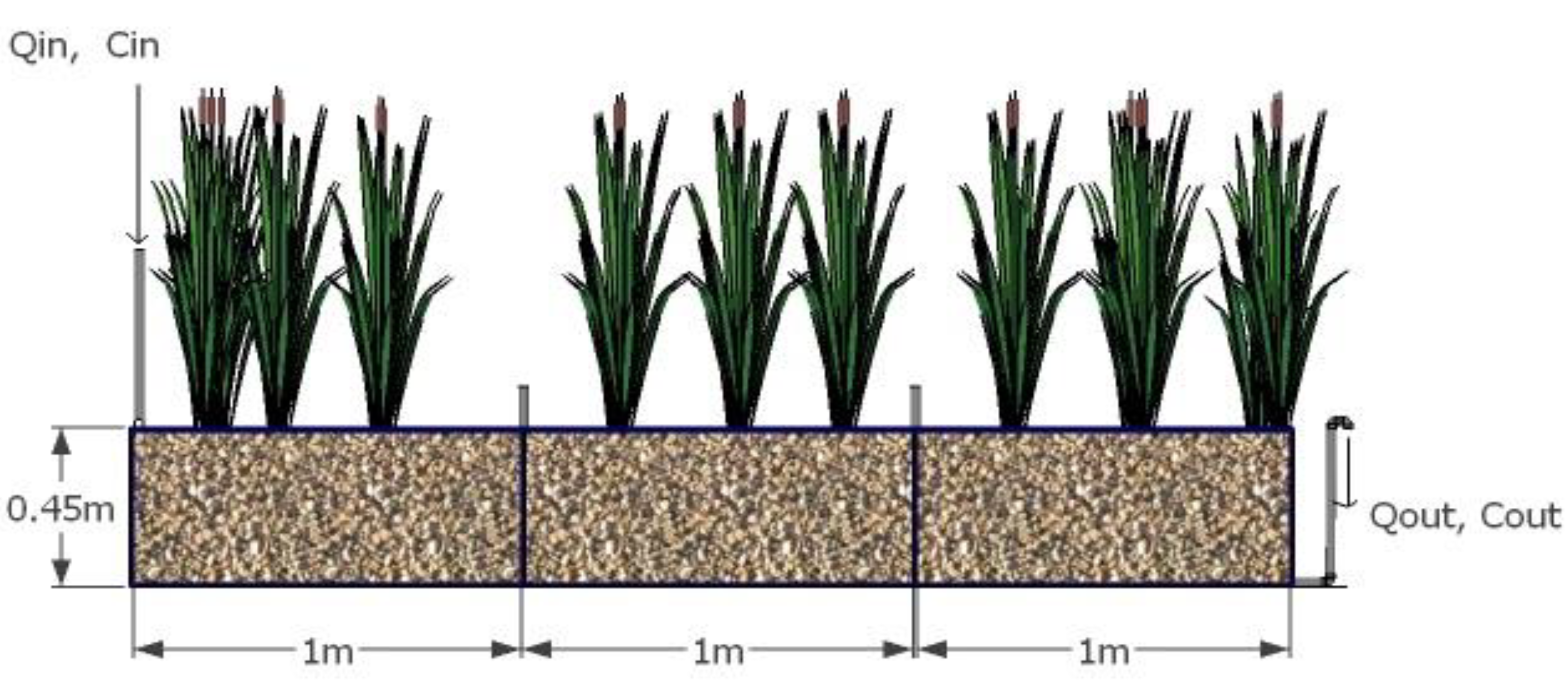

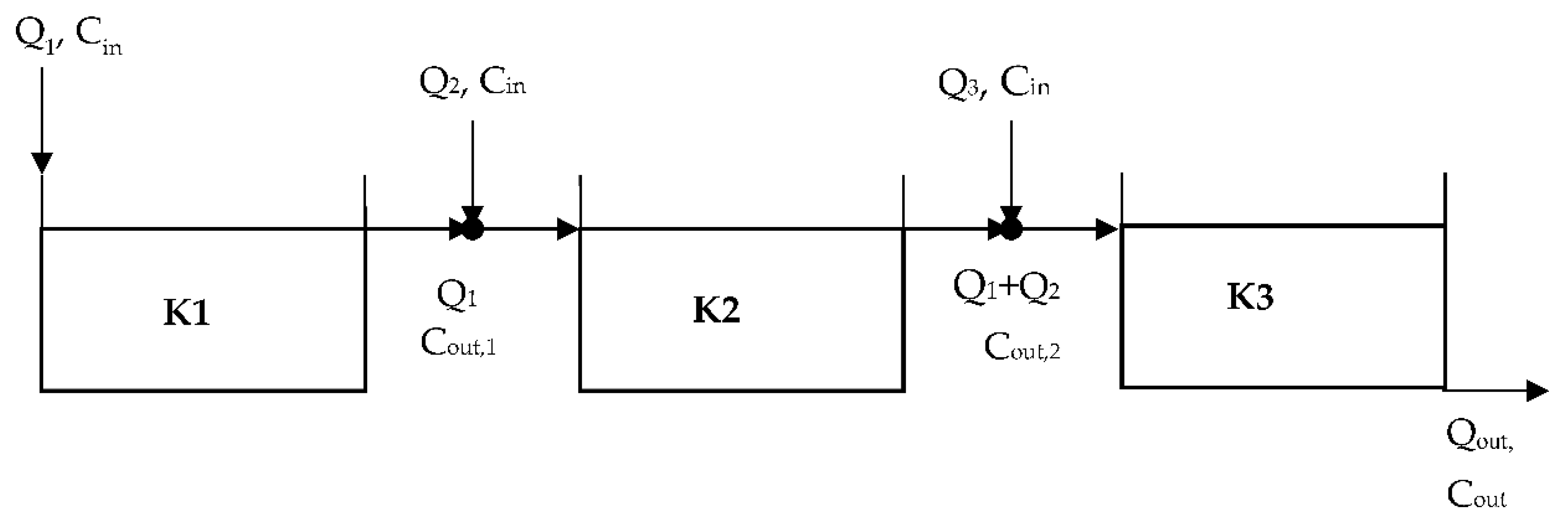

2. The Numerical Formulation of Step-feeding

3. Analysis by using the TIS Methodology

4. Analysis by using the PFR Methodology

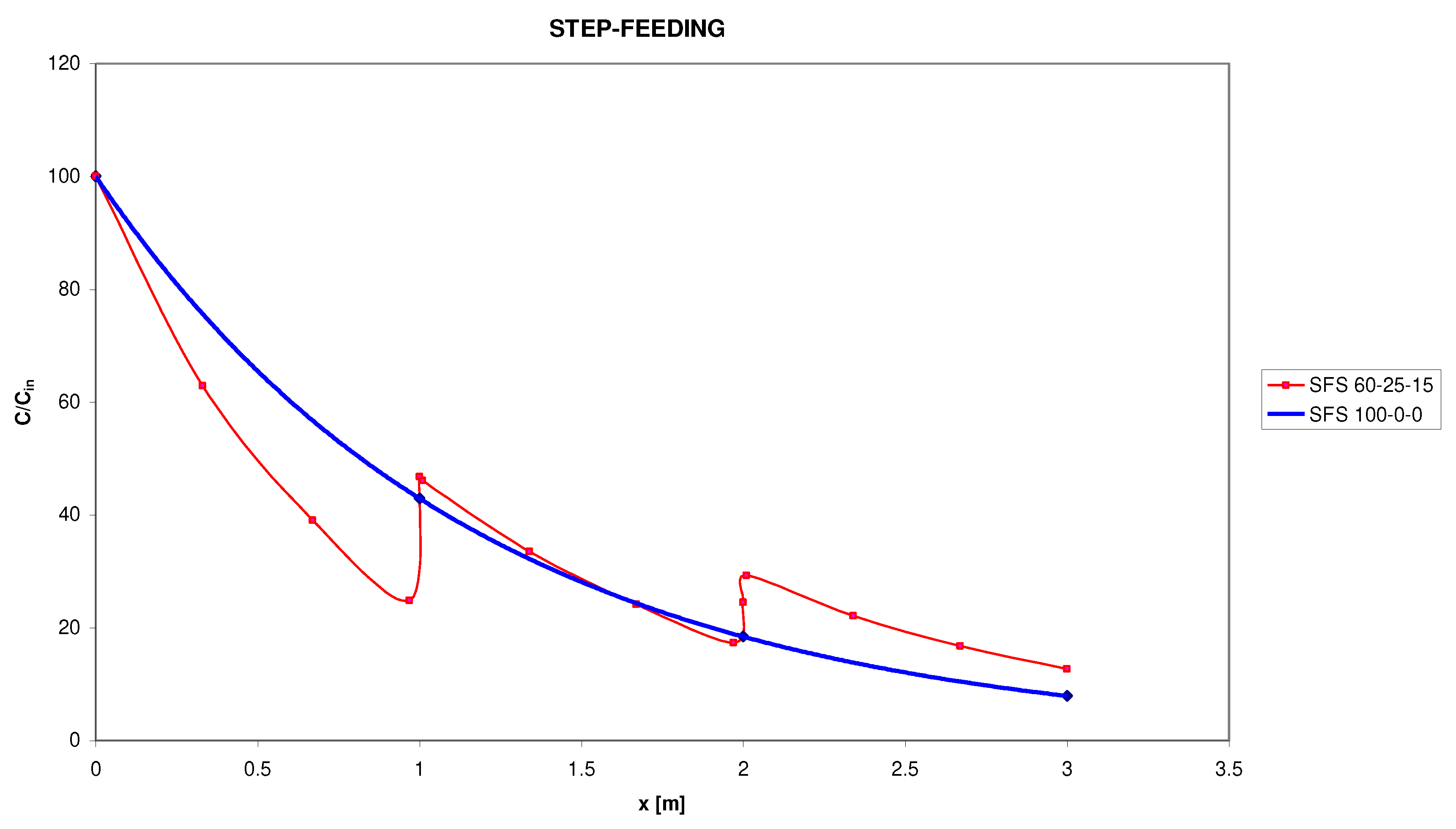

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Numerical Example

5.2. Discussion and Comparison with other Studies

6. Conclusions

References

- Vymazal, J.; Zhao, Y.; Mander, U. Recent research challenges in constructed wetlands for wastewater treatment: A review. Ecol. Eng. 2021, 169, 106318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parde, D.; Patwa, A.; Shukla, A.; Vijay, R.; Killedar, D.J.; Kumar, R. A review of constructed wetland on type, treatment and technology of wastewater. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2021, 21, 101261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshiri, G.A. Constructed Wetlands for Water Quality Improvement; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Varma, M.; Gupta, A.K.; Ghosal, P.S.; Majumder, A. A review on performance of constructed wetlands in tropical and cold climate: Insights of mechanism, role of influencing factors, and system modification in low temperature. Sci. Total Env. 2021, 755, 142540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, P.; Pei, H.; Hu, W.; Shao, Y.; Li, Z. How to increase microbial degradation in constructed wetlands: Influencing factors and improvement measures. Bioresource Technol. 2014, 157, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, T.; Sun, G. A review on nitrogen and organics removal mechanisms in subsurface flow constructed wetlands: Dependency on environmental parameters, operating conditions and supporting media. J. Environ. Manage. 2012, 112, 429–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khajah, M.; Bydalek, F.; Babatunde, A.O.; Al-Matouq, A.; Wenk, J.; Webster, G. Nitrogen removal performance and bacterial community analysis of a multistage step-feeding tidal flow constructed wetland. Front. Water 2023, 5, 1128901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, T.; Miah, M.J.; Khan, T.; Ove, A. Pollutant removal employing tidal flow constructed wetlands: Media and feeding strategies. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 382, 122874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrijos, V.; Ruiz, I.; Soto, M. Effect of step-feeding on the performance of lab-scale columns simulating vertical flow-horizontal flow constructed wetlands. Environ. Sci. Pollut. R. 2017, 24, 22649–22662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Huang, M.; Qi, R.; Fan, S.; Wang, Y.; Fan, T. Enhanced nitrogen removal and associated microbial characteristics in a modified single-stage tidal flow constructed wetland with step-feeding. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 314, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Wu, J.; Zhong, F.; Xiang., D.; Cheng, S. Effect of step feeding on the performance of multi-stage vertical flow constructed wetland for municipal wastewater treatment. J. Lake Sci. 2017, 29(5), 1084–1090. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, J.; Liang, S.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, J. Enhanced organics and nitrogen removal in batch-operated vertical flow constructed wetlands by combination of intermittent aeration and step feeding strategy. Environ. Sci. Pollut. R. 2013, 20, 2448–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.S.; Zhao, Y.Q.; Zhao, X.H.; Kumar, J.L.G. Comprehensive analysis of step-feeding strategy to enhance biological nitrogen removal in alum sludge-based tidal flow constructed wetlands. Bioresource Technol. 2012, 111, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, S.; Chakraborty, S. Effects of step-feeding and intermittent aeration on organics and nitrogen removal in a horizontal subsurface flow constructed wetland. J. Environ. Sci. Heal. A 2017, 52(4), 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Lu, L.; Zheng, X.; Ngo, H.H.; Liang, S.; Guo, W.; Zhang, X. Enhanced nitrogen removal in constructed wetlands: Effects of dissolved oxygen and step-feeding. Bioresource Technol. 2014, 169, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefanakis, A.I.; Akratos, C.S.; Tsihrintzis, V.A. Effect of wastewater step-feeding on removal efficiency of pilot-scale horizontal subsurface flow constructed wetlands. Ecol. Eng. 2011, 37(3), 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liolios, K.A.; Moutsopoulos, K.N.; Tsihrintzis, V.A. Modelling alternative feeding techniques in HSF constructed wetlands. Environ. Proces. 2016, 3(1), 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liolios, K.A.; Moutsopoulos, K.N.; Tsihrintzis, V.A. Modeling of flow and BOD fate in horizontal subsurface flow constructed wetlands. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 200-202, 681–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, R.; Sheridan, C.; Kappelmeyer, U. A curve-shift technique for the use of non-conservative organic tracers in constructed wetlands.). Sci. Total Env. 2021, 752, 141818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moukalled, F.; Mangani, L.; Darwish, M. The Finite Volume Method in Computational Fluid Mechanics; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bear, J.; Cheng, A.H.D. Modeling Groundwater Flow and Contaminant Transport; Springer Dordrecht Heidelberg: New York, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

| CW tank | HRT [days] | ε [%] |

Κ [m/sec] |

Vp [m3] |

Tav [oC ] |

Cin [mg/L] |

Cout [mg/L] |

λ [day-1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MG-R | 6 8 14 20 |

0.35 | 0.7196 0.7640 0.9743 0.7196 |

0.3544 0.3594 0.3848 0.3544 |

5.7 11.8 18.7 22.4 |

321.5 333.0 332.0 345.3 |

141.8 87.7 60.9 48.3 |

0.1212 0.1992 0.2546 0.3852 |

| 0.355 0.38 0.35 | ||||||||

| MG-C | 6 | 0.33 | 0.5620 | 0.3341 | 25.7 | 327.0 | 26.0 | 0.3852 |

| 8 | 0.335 | 0.5980 | 0.3392 | 4.5 | 350.0 | 124.0 | 0.1155 | |

| 14 20 |

0.34 0.33 |

0.6366 0.5620 |

0.3443 0.3341 |

8.8 13.1 |

358.6 348.5 |

72.4 50.8 |

0.1799 0.2178 |

|

| MG-Z | 6 8 14 20 |

0.37 0.37 0.37 0.37 |

0.9120 0.9120 0.9120 0.9120 |

0.3746 0.3746 0.3746 0.3746 |

16.3 19.2 11.2 17.9 |

380.0 373.7 372.0 358.7 |

34.3 22.6 65.3 40.3 |

0.2740 0.3217 0.1126 0.1426 |

| FG-R | 6 8 14 20 |

0.29 0.29 0.31 0.29 |

0.0199 0.0199 0.0262 0.0199 |

0.2936 0.2936 0.3139 0.2936 |

21.2 8.7 13.8 16.3 |

461.5 355.8 323.3 364.3 |

30.7 45.5 22.9 34.8 |

0.1784 0.0923 0.1210 0.1066 |

| CO-R | 6 8 14 20 |

0.28 0.28 0.28 0.28 |

3.8710 3.8710 3.8710 3.8710 |

0.2835 0.2835 0.2835 0.2835 |

21.9 5.7 11.8 18.7 |

381.4 321.5 333.0 332.0 |

35.0 141.8 87.7 60.9 |

0.1085 0.1212 0.1992 0.2546 |

| Step-feeding scenario | TIS methodology | PFR methodology |

|---|---|---|

| (A) | Cout = 0.3280Cin | Cout = 0.2592Cin |

| (B) | Cout = 0.3386Cin | Cout = 0.2667Cin |

| (C) | Cout = 0.3533Cin | Cout = 0.2779Cin |

| (D) | Cout = 0.3708Cin | Cout = 0.2959Cin |

| (E) | Cout = 0.4255Cin | Cout = 0.3980 Cin |

| Step-feeding scenario | HSF CW performance [%] for TIS method |

HSF CW performance [%] for PFR method |

|---|---|---|

| (A) | 67.20 | 74.08 |

| (B) | 66.14 | 73.33 |

| (C) | 64.67 | 72.21 |

| (D) | 62.92 | 73.33 |

| (E) | 57.45 | 60.20 |

| Reference | CW type |

Pollutant | Step-feeding scenario | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) | (B) | (C) | (D) | (E) | (F) | |||

| Stefanakis et al. [16] (HRT = 6 days) |

BOD | 84.2 | — | — | 88.7 | — | — | |

| HSF | COD | 82.7 | — | — | 87.4 | — | — | |

| TKN | 76.5 | — | — | 75.5 | — | — | ||

| Stefanakis et al. [16] (HRT = 14 days) |

BOD | 89.4 | — | — | — | 83.3 | — | |

| HSF | COD | 89.4 | — | — | — | 84.0 | — | |

| NH4+-N | 71.8 | — | — | — | 38.5 | — | ||

| Liolios et al. [17] | HSF | BOD | 92.5 | 91.7 | 90.3 | 88.2 | 82.1 | — |

| Li et al. [15] (HRT = 5 days) |

COD | 87.2 | 67.8 | — | — | — | — | |

| HSF | NH4+-N | 99.0 | 93.5 | — | — | — | — | |

| TN | 55.5 | 60.6 | — | — | — | — | ||

| Li et al. [15] (HRT = 8.4 days) |

HSF | COD NH4+-N TN |

83.2 98.9 56.4 |

90.9 99.1 88.1 |

— — — |

— — — |

— — — |

— — — |

| Fan et al. [5] |

VF | COD TN |

88.0 44.0 |

— — |

— — |

— — |

— — |

97.0 82.0 |

| Hu et al. [6] | VF | TN | 85.0 | 90.2 | — | — | — | — |

| Khajah et al. [7] |

VF | COD TN |

75.0 73.5 |

94.0 70.0 |

90.0 75.0 |

— — |

— — |

— — |

| Saeed et al. [8] |

VF | BOD TP |

87.4 92.4 |

— — |

— — |

— — |

— — |

93.9 94.2 |

| Wang et al. [10] |

VF | BOD COD |

97.2 96.5 |

— — |

— — |

— — |

95.9 95.9 |

96.8 99.9 |

| Torrijos et al. [9] | HSF+VF | COD | 96.0 | — | — | — | — | 99.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).