Submitted:

26 November 2024

Posted:

28 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

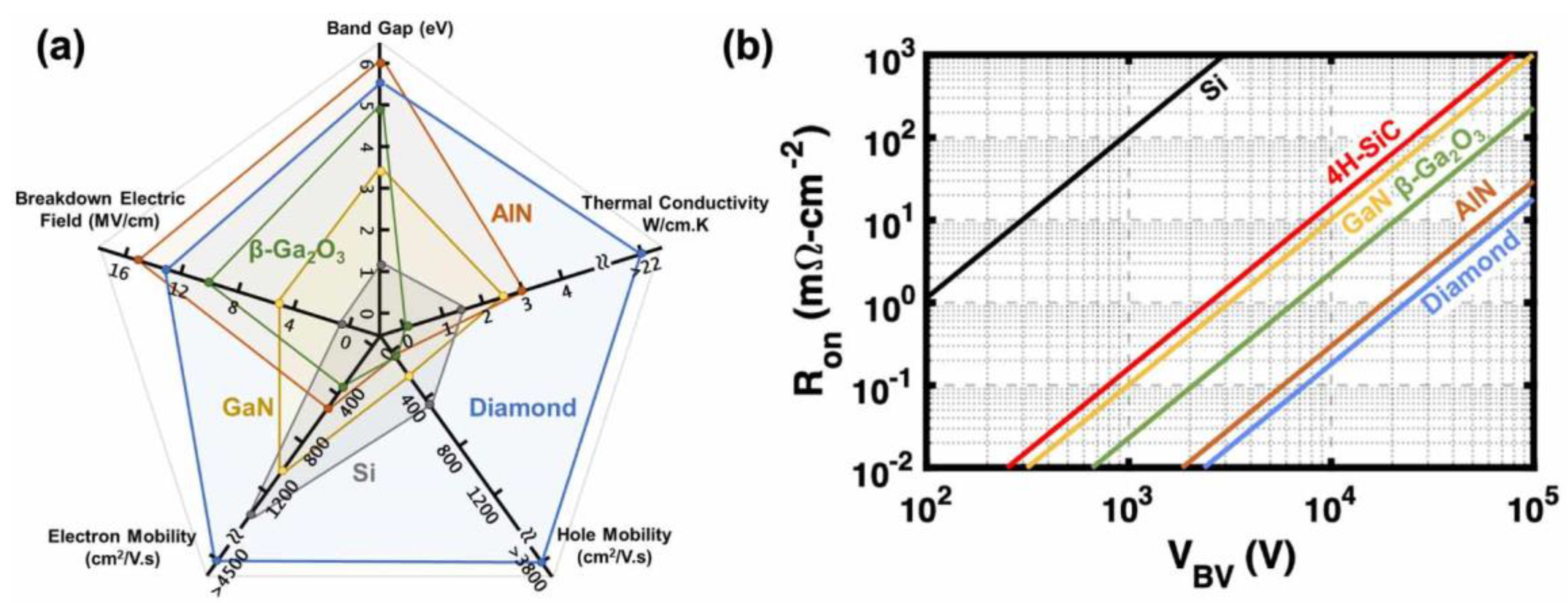

1.1. Overview of Wide Bandgap Semiconductors

1.2. Properties and Significance of Wide-Bandgap Semiconductors

1.3. Examples of Wide-Bandgap Semiconductors

Silicon Carbide (SiC)

Gallium Nitride (GaN)

Aluminum Gallium Nitride (AlGaN)

Diamond

Gallium Oxide (Ga2O3)

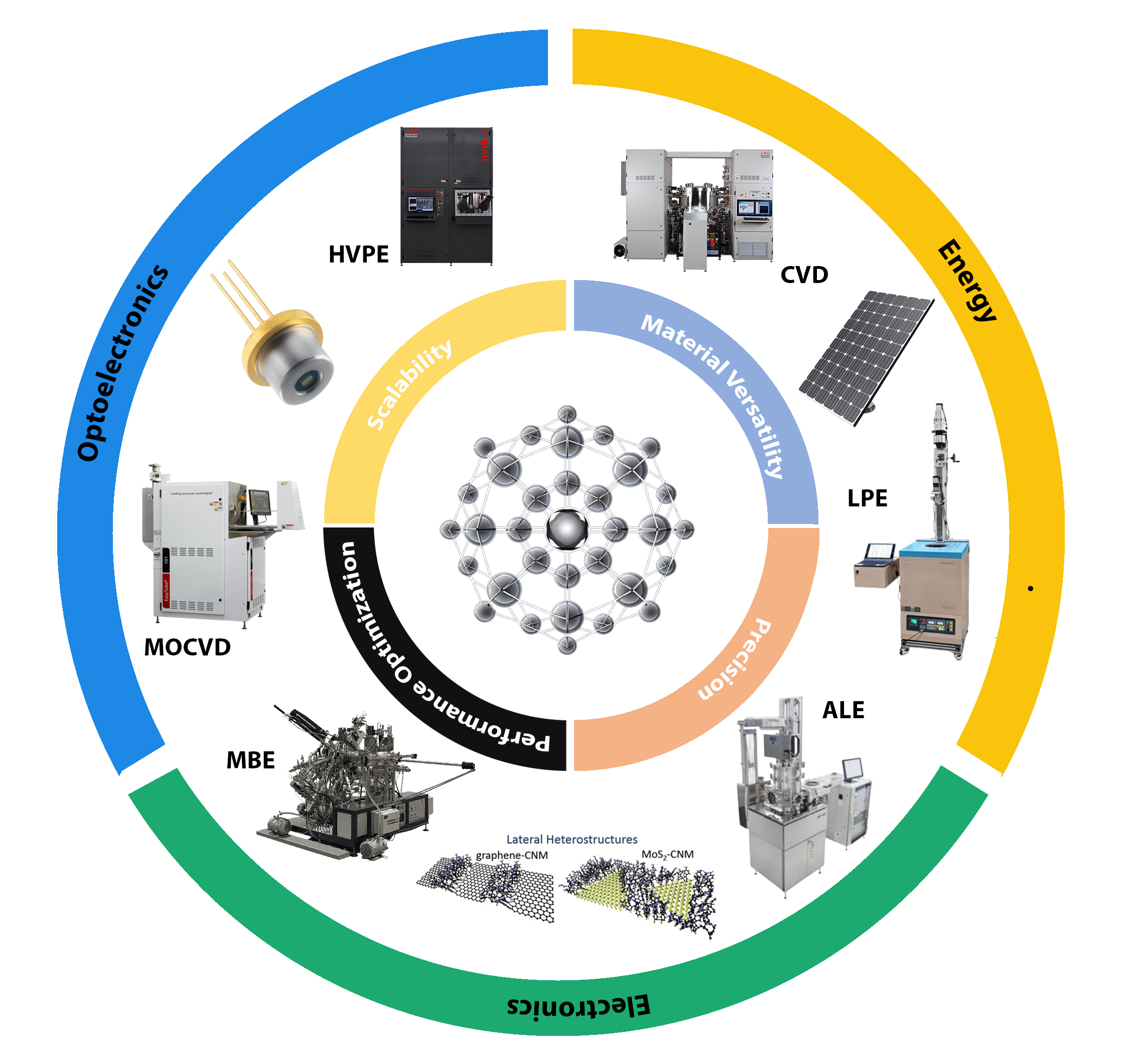

1.4. Overview of Epitaxial Growth Techniques

1.5. Challenges in Epitaxial Growth of WBG Semiconductors

1.5. Objectives of the Research

2. Epitaxial Growth Techniques

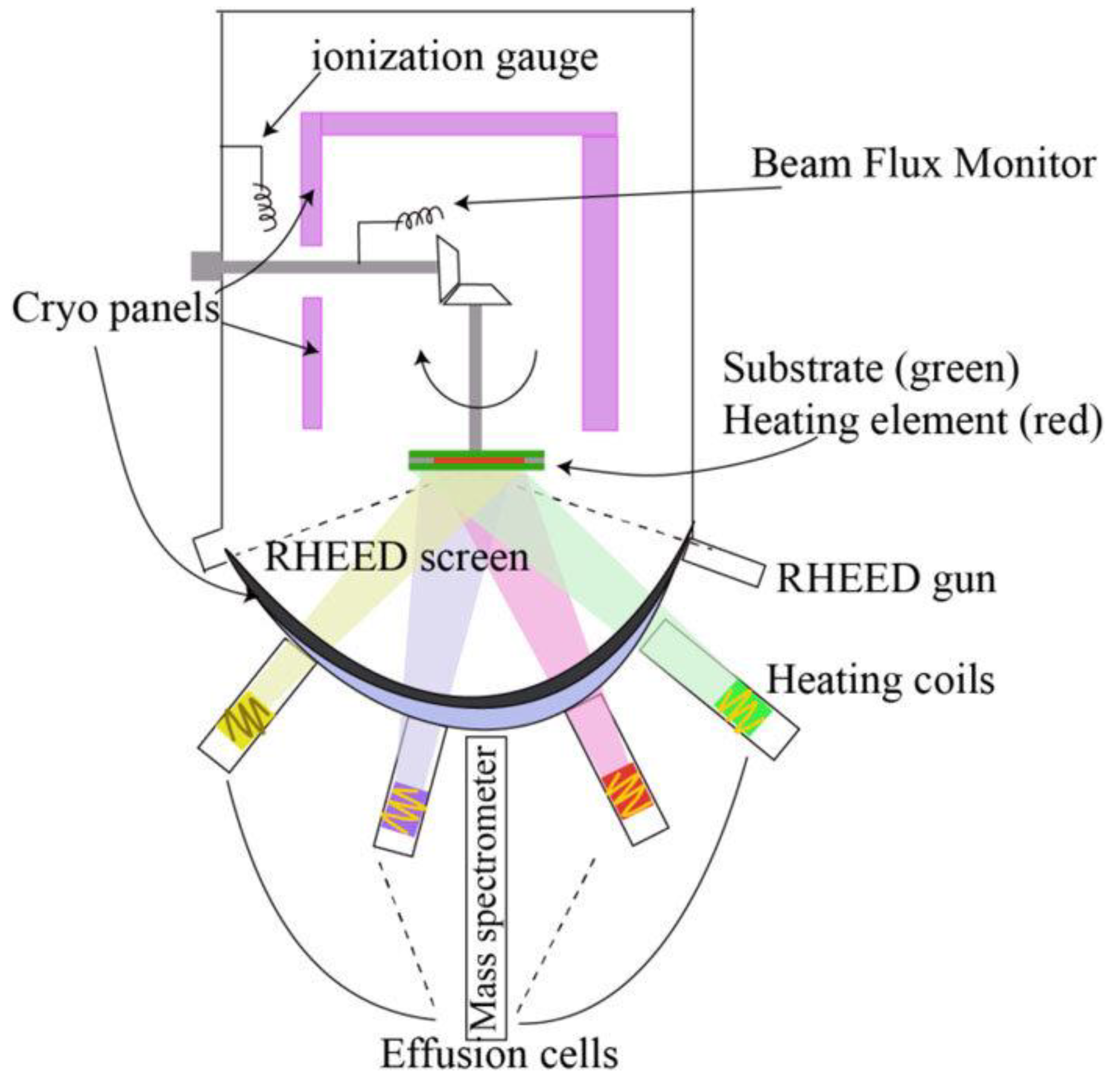

2.1. Molecular Beam Epitaxy (MBE)

MBE Technique Process

MBE advantages, applications, and challenges

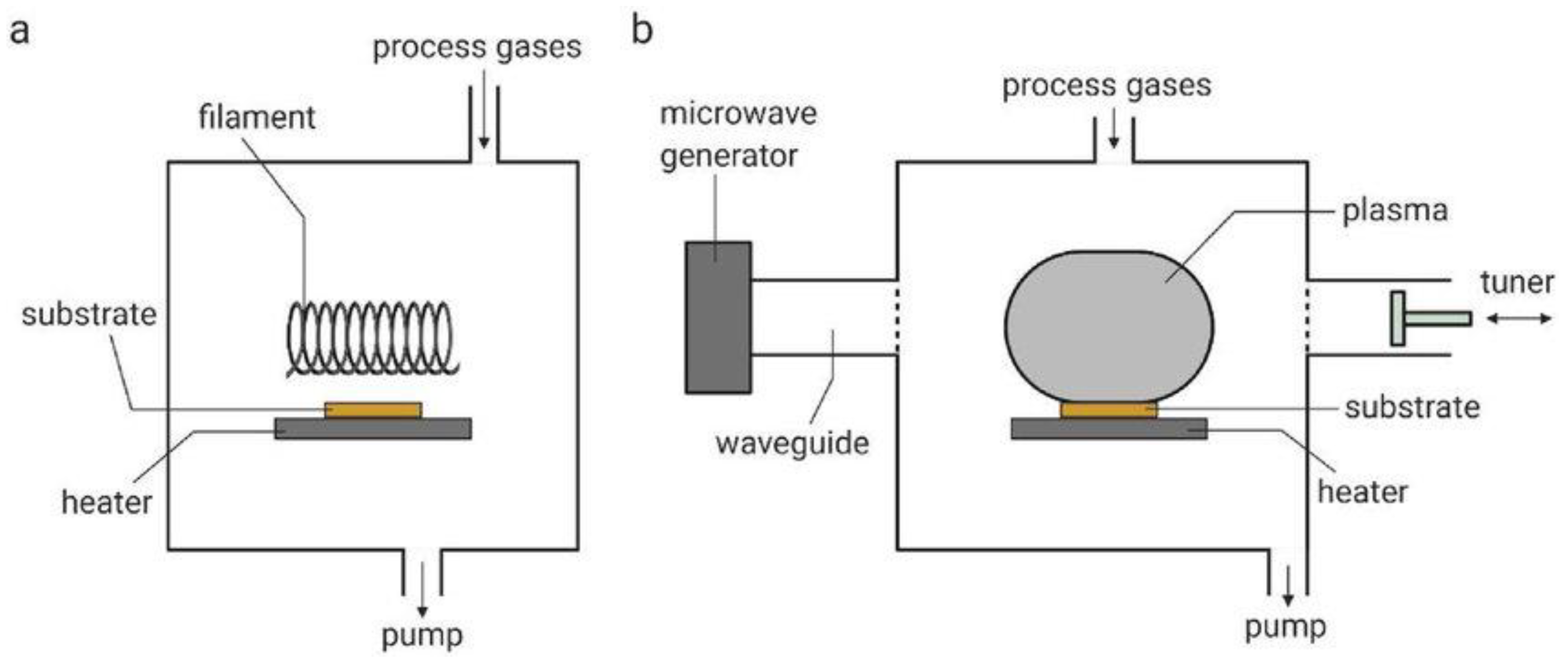

2.2. Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) or Epitaxial Chemical Vapor Deposition (E-CVD)

Chemical Vapor Deposition Process

CVD Advantages, Applications, and Challenges

2.3. Metal-Organic Chemical Vapor Deposition (MOCVD)

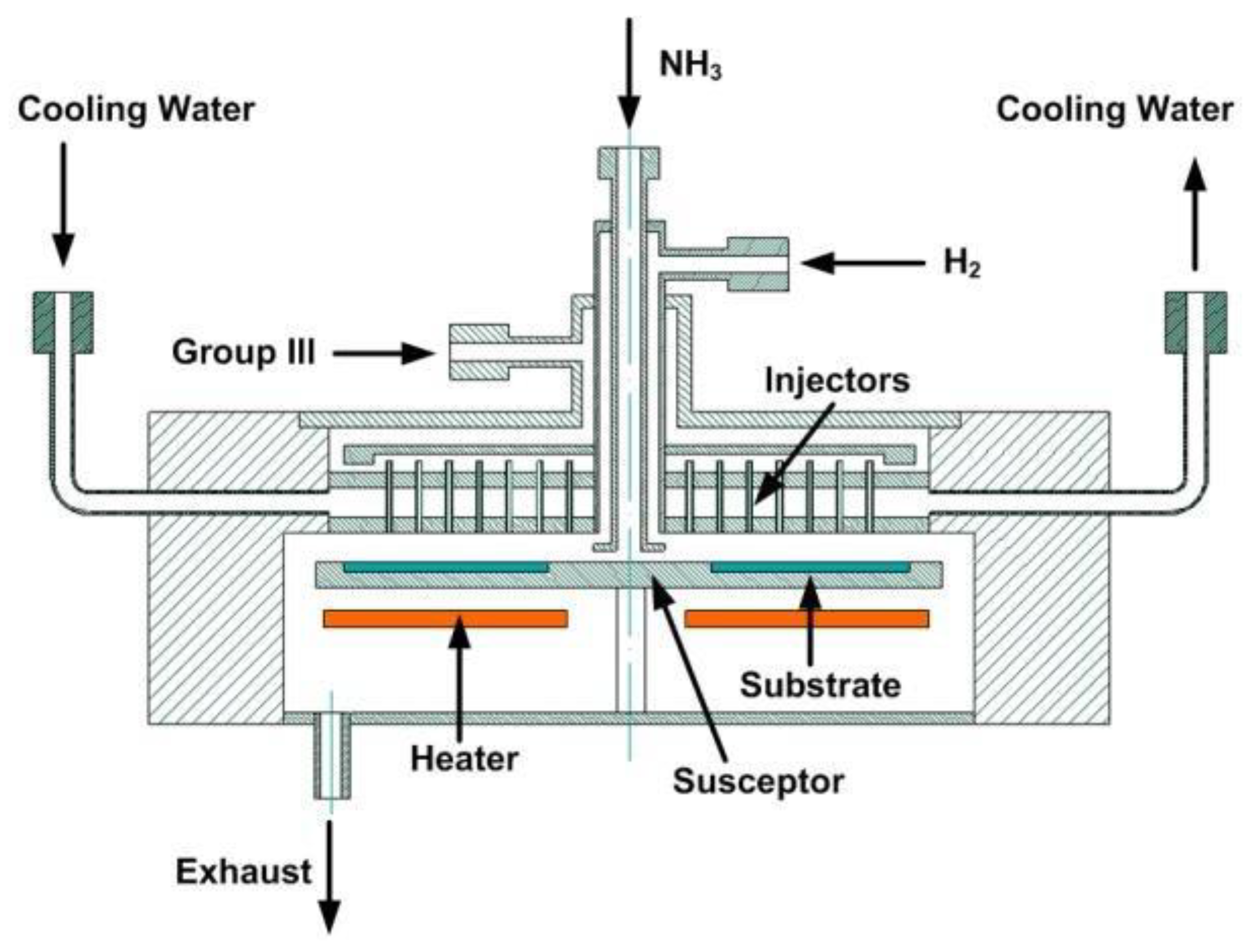

MOCVD Technique Process

MOCVD Advantages, Applications and Challenges

2.4. Hydride Vapor Phase Epitaxy (HVPE)

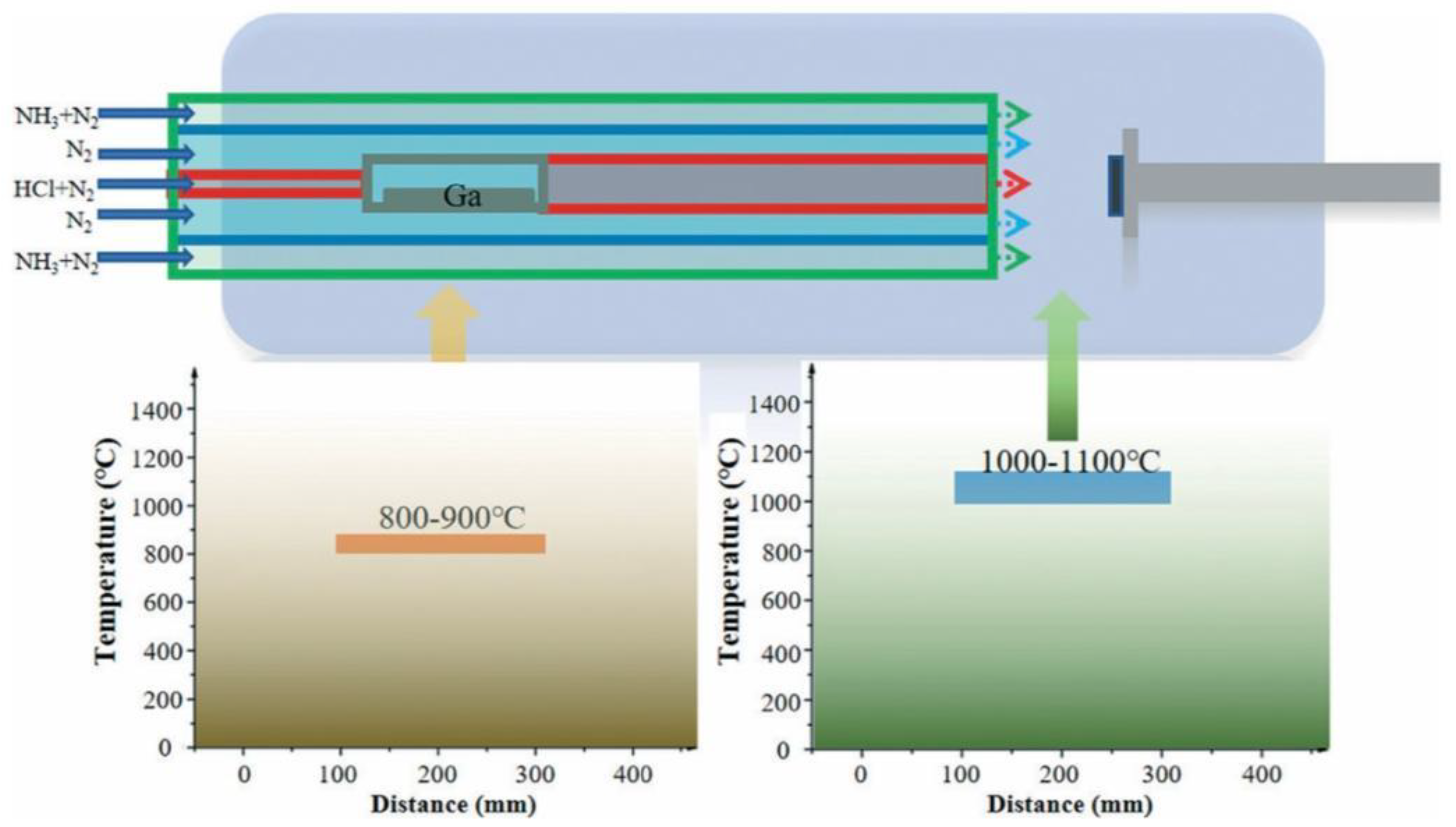

Hydride Vapor Phase Epitaxy Process

HVPE Advantages, Applications, and Challenges

2.5. Liquid Phase Epitaxy (LPE)

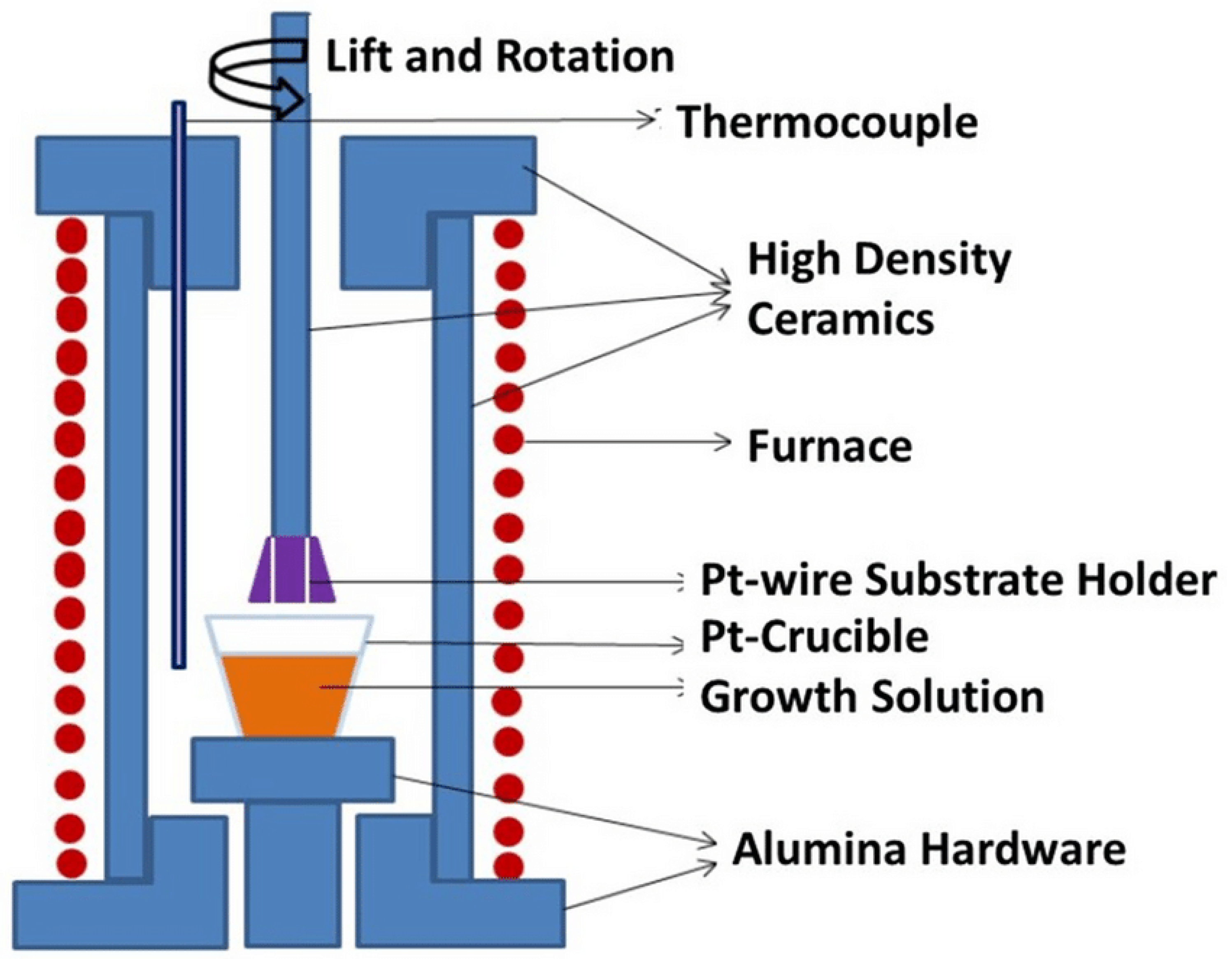

LPE Technique Process

LPE Advantages, Applications and Challenges

2.6. Atomic Layer Epitaxy (ALE)

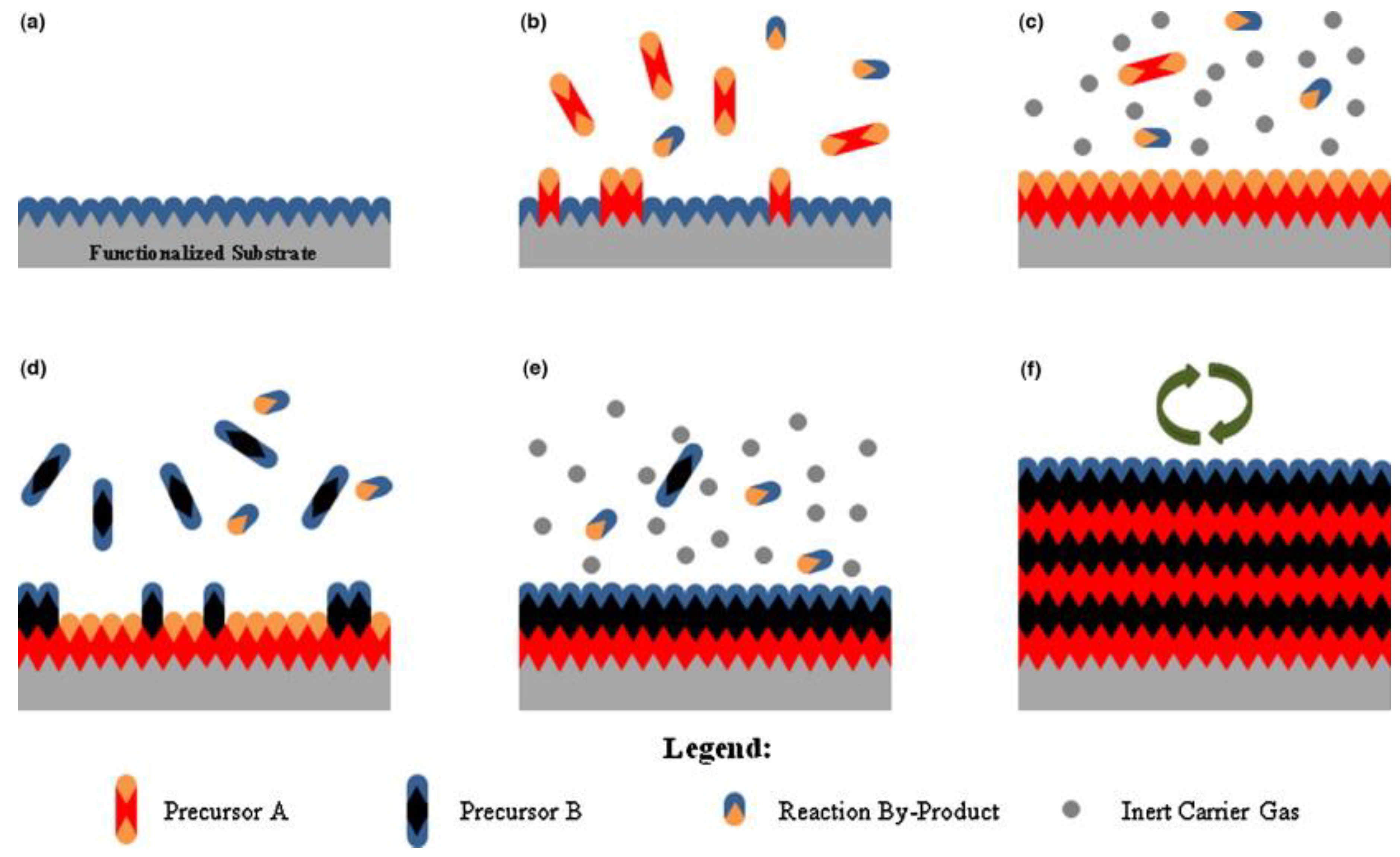

ALE Technique Process

ALE Advantages, Applications and Challenges

2.7. Pulsed Laser Deposition (PLD)

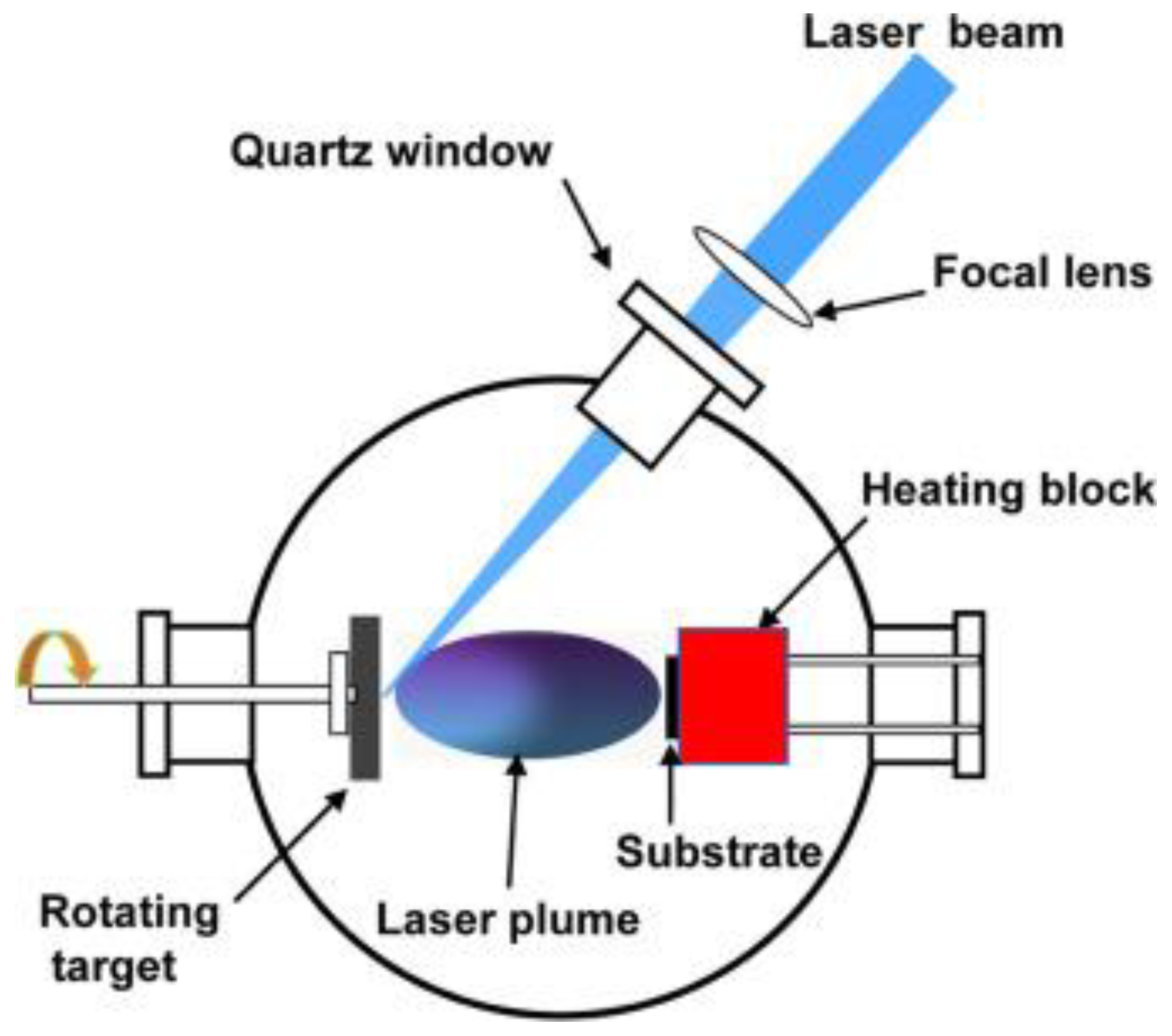

Pulsed Laser Deposition Process

PLD Advantages, Applications and Challenges

2.8. Comparative Analysis of Epitaxial Growth Techniques

3. Applications of Epitaxially Grown Wide-Bandgap Semiconductors

4. Current Innovations and Future Research Directions

Innovation in Defect Management

Innovation in Nanostructure Fabrication

Challenges and Future Research Needs

Conclusion

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- J. Y. Tsao et al., “Ultrawide-Bandgap Semiconductors: Research Opportunities and Challenges,” Adv Electron Mater, vol. 4, no. 1, p. 1600501, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. L. Lyons, D. Wickramaratne, and A. Janotti, “Dopants and defects in ultra-wide bandgap semiconductors,” Curr Opin Solid State Mater Sci, vol. 30, p. 101148, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. Woo et al., “From wide to ultrawide-bandgap semiconductors for high power and high frequency electronic devices,” Journal of Physics: Materials, vol. 7, no. 2, p. 022003, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Md. B. Pramanik, Md. A. Al Rakib, Md. A. Siddik, and S. Bhuiyan, “Doping Effects and Relationship between Energy Band Gaps, Impact of Ionization Coefficient and Light Absorption Coefficient in Semiconductors,” European Journal of Engineering and Technology Research, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 10–15, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. Kirihara et al., “Transparent Patternable Large-Area Graphene p-n Junctions by Photoinduced Electron Doping,” ACS Appl Mater Interfaces, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 1198–1205, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Blackburn, M. A. H. Palacios, and A. J. Ferguson, “(Invited) Electronic Doping in Two-Dimensional Semiconductors,” ECS Meeting Abstracts, vol. MA2024-01, no. 12, p. 1012, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Burgos, “Wide Bandgap Generation (WBGen): Developing the Future Wide Bandgap Power Electronics Engineering Workforce,” Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Lu, “A systematic analysis of wide band gap semiconductor used in power electronics,” Applied and Computational Engineering, vol. 65, no. 1, pp. 161–166, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Yuvaraja, V. Khandelwal, X. Tang, and X. Li, “Wide bandgap semiconductor-based integrated circuits,” Chip, vol. 2, no. 4, p. 100072, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Berube, A. Ghazanfari, H. F. Blanchette, C. Perreault, and K. Zaghib, “Recent Advances in Wide Bandgap Devices for Automotive Industry,” IECON Proceedings (Industrial Electronics Conference), vol. 2020-October, pp. 2557–2564, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Q. Wang et al., “(Invited) Wide Bandgap Semiconductor Based Devices for Digital and Industrial Applications,” ECS Trans, vol. 112, no. 2, p. 37, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Tingsuwatit et al., “Properties of photocurrent and metal contacts of highly resistive ultrawide bandgap semiconductors,” Appl Phys Lett, vol. 124, no. 16, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- G. Pavlidis, M. Jamil, and B. Bista, “(Invited) Sub-Bandgap Thermoreflectance Imaging of Ultra-Wide Bandgap Semiconductors,” ECS Meeting Abstracts, vol. MA2023-01, no. 32, p. 1822, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Patel, B. Panda, Snehalika, and P. Dash, “A Comprehensive Analysis on the Performance of SiC and GaN Devices,” 2022 International Virtual Conference on Power Engineering Computing and Control: Developments in Electric Vehicles and Energy Sector for Sustainable Future, PECCON 2022, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Usman, M. Munsif, A. R. Anwar, H. Jamal, S. Malik, and N. U. Islam, “Quantum efficiency enhancement by employing specially designed AlGaN electron blocking layer,” Superlattices Microstruct, vol. 139, p. 106417, Mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. K. Mondal, V. Chatterjee, and S. Pal, “Effect of step-graded superlattice electron blocking layer on performance of AlGaN based deep-UV light emitting diodes,” Physica E Low Dimens Syst Nanostruct, vol. 108, pp. 233–237, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- C. Chu et al., “On the AlxGa1-xN/AlyGa1-yN/AlxGa1-xN (x>y) p-electron blocking layer to improve the hole injection for AlGaN based deep ultraviolet light-emitting diodes,” Superlattices Microstruct, vol. 113, pp. 472–477, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. Yang, K. Liu, X. Chen, and D. Shen, “Recent advances in optoelectronic and microelectronic devices based on ultrawide-bandgap semiconductors,” May 01, 2022, Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- M. D. Vecchia, S. Ravyts, G. Van den Broeck, and J. Driesen, “Gallium-nitride semiconductor technology and its practical design challenges in power electronics applications: An overview,” Energies (Basel), vol. 12, no. 14, 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. Tran, “Thermal conductivity of wide and ultra-wide bandgap semiconductors,” vol. 2334, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Prasad Bhupathi et al., “Investigation of WBG based Power Converters used in E-Transportation,” E3S Web of Conferences, vol. 552, p. 01145, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. Shenai, “Future prospects of widebandgap (WBG) semiconductor power switching devices,” IEEE Trans Electron Devices, vol. 62, no. 2, pp. 248–257, Feb. 2015. [CrossRef]

- L. Boteler, A. Lelis, M. Berman, and M. Fish, “Thermal conductivity of power semiconductors-when does it matter?,” 2019 IEEE 7th Workshop on Wide Bandgap Power Devices and Applications, WiPDA 2019, pp. 265–271, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. A. Pham, T. Dinh, N. Nguyen, and H. Phan, “Thermal Properties of Wide Bandgap Nanowires,” Wide Bandgap Nanowires, pp. 123–137, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J.-H. D. S. J.-P. Lee, “High Technology and Latest Trends of WBG Power Semiconductors,” Journal of the Microelectronics and Packaging Society, vol. 25, no. 4, pp. 17–23, 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. H. Jeong, J. H. Cha, G. H. Kim, S. H. Cho, and H. J. Lee, “Study of a SiC Trench MOSFET Edge-Termination Structure with a Bottom Protection Well for a High Breakdown Voltage,” Applied Sciences 2020, Vol. 10, Page 753, vol. 10, no. 3, p. 753, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Patnaik, “Breakdown Voltage Analysis of High Electron Mobility Transistor,” 2018.

- G. Ghibaudo and Q. Rafhay, “Electron and Hole Mobility in Semiconductor Devices,” Wiley Encyclopedia of Electrical and Electronics Engineering, pp. 1–13, Sep. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Examiner and S. K. Salerno, “Electronic device including high electron mobility transistors,” Circuit Capability, pp. 195–198, Sep. 2018.

- F. Trier, D. V. Christensen, and N. Pryds, “Electron mobility in oxide heterostructures,” J Phys D Appl Phys, vol. 51, no. 29, p. 293002, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- N. Pornsuwancharoen, P. Youplao, I. S. Amiri, J. Ali, and P. Yupapin, “Electron driven mobility model by light on the stacked metal–dielectric interfaces,” Microw Opt Technol Lett, vol. 59, no. 7, pp. 1704–1709, Jul. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Erken and A. H. Obdan, “Examining the Optimal Use of WBG Devices in Induction Cookers,” Applied Sciences 2023, Vol. 13, Page 12517, vol. 13, no. 22, p. 12517, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Demcko, “Recent Advances in Capacitors Used in Wide Bandgap Power Circuitry,” IEEE Power Electronics Magazine, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 23–28, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. Lee, J. Kim, S. Choi, and B. Ma, “Comparative Thermal Analysis of Wide Band Gap Power Module,” InterSociety Conference on Thermal and Thermomechanical Phenomena in Electronic Systems, ITHERM, vol. 2023-May, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Huang, R. Wang, D. Yang, and X. Pi, “Impurities in 4H silicon carbide: Site preference, lattice distortion, solubility, and charge transition levels,” J Appl Phys, vol. 135, no. 19, p. 195703, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- W. Mao et al., “Surface defects in 4H-SiC: properties, characterizations and passivation schemes,” Semicond Sci Technol, vol. 38, no. 7, p. 073001, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. Kaygusuz et al., “21. Yüzyılda Mühendislikte Çağdaş Araştırma Uygulamaları Üzerine Disiplinler Arası Çalışmalar IV,” Ozgur Press, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Long, Z. Liu, and F. Ayazi, “4H-Silicon Carbide as an Acoustic Material for MEMS,” IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control, vol. 70, no. 10, pp. 1189–1200, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. K. Gachovska and J. L. Hudgins, “SiC and GaN Power Semiconductor Devices,” Power Electronics Handbook, pp. 87–150, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Mohanbabu, S. Maheswari, N. Vinodhkumar, P. Murugapandiyan, and R. S. Kumar, “Advancements in GaN Technologies: Power, RF, Digital and Quantum Applications,” Nanoelectronic Devices and Applications, pp. 1–28, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Du, R. Ye, and X. Cai, “Advancements in GaN HEMT structures and applications: A comprehensive overview,” J Phys Conf Ser, vol. 2786, no. 1, p. 012003, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- N. Collaert, “Gallium nitride technologies for wireless communication,” New Materials and Devices Enabling 5G Applications and Beyond, pp. 101–137, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Xu, “Applications and Research Progress of GaN,” Highlights in Science, Engineering and Technology, vol. 32, pp. 271–278, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Younsi, A. Rabehi, and A. Douara, “A theoretical study of Structural and electronic properties of Al0,125B0,125Ga0,75N; optoelectronic applications,” All Sciences Abstracts, vol. 1, no. 5, pp. 12–12, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Ye, M. Gaevski, G. Simin, A. Khan, and P. Fay, “Electron mobility and velocity in Al0.45Ga0.55N-channel ultra-wide bandgap HEMTs at high temperatures for RF power applications,” Appl Phys Lett, vol. 120, no. 10, p. 103505, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Gaska, M. S. Shur, and A. Khan, “AlGaN/GaN High Electron Mobility Transistors,” III-V Nitride Semiconductors, pp. 193–269, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- B. C. Joshi, “AlGaN/GaN heterostructures for high power and high-speed applications,” International Journal of Materials Research, vol. 114, no. 7–8, pp. 712–717, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Makino, “ダイヤモンド半導体デバイス開発と最近の進展,” 電気学会論文誌C(電子・情報・システム部門誌), vol. 144, no. 3, pp. 193–197, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- F. Zhao, Y. He, B. Huang, T. Zhang, and H. Zhu, “A Review of Diamond Materials and Applications in Power Semiconductor Devices,” Materials 2024, Vol. 17, Page 3437, vol. 17, no. 14, p. 3437, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Fei et al., “Research progress of optoelectronic devices based on diamond materials,” Front Phys, vol. 11, p. 1226374, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Lu, D. Xu, N. Huang, X. Jiang, and B. Yang, “One-dimensional diamond nanostructures: Fabrication, properties and applications,” Carbon N Y, vol. 223, p. 119020, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Sun, Z. Zhang, Y. Liu, G. Chen, T. Li, and M. Liao, “Diamond MEMS: From Classical to Quantum,” Adv Quantum Technol, vol. 6, no. 11, p. 2300189, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- V. V. Manju, V. N. Hegde, T. M. Pradeep, B. C. Hemaraju, and R. Somashekar, “Synthesis and characterization of Ga2O3 nanoparticles for electronic device applications,” Inorg Chem Commun, vol. 165, p. 112562, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. N. Reddy and D. K. Panda, “ Next Generation High-Power Material Ga 2 O 3 : Its Properties, Applications, and Challenges ,” Nanoelectronic Devices and Applications, pp. 160–188, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- B. Li et al., “Gallium oxide (Ga2O3) heterogeneous and heterojunction power devices,” Fundamental research, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. He, F. Zhao, B. Huang, T. Zhang, and H. Zhu, “A Review of β-Ga2O3 Power Diodes,” Materials 2024, Vol. 17, Page 1870, vol. 17, no. 8, p. 1870, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- N. H. Al-Hardan, M. A. Abdul Hamid, A. Jalar, and M. Firdaus-Raih, “Unleashing the potential of gallium oxide: A paradigm shift in optoelectronic applications for image sensing and neuromorphic computing applications,” Materials Today Physics, vol. 38, p. 101279, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Xu, D. Wang, K. Fu, D. H. Mudiyanselage, H. Fu, and Y. Hao, “A review of ultrawide bandgap materials: properties, synthesis and devices,” Oxford Open Materials Science, vol. 2, no. 1, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. Wangila et al., “The Epitaxial Growth of Ge and GeSn Semiconductor Thin Films on C-Plane Sapphire,” Crystals (Basel), vol. 14, no. 5, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. K. Hite, “A Review of Homoepitaxy of III-Nitride Semiconductors by Metal Organic Chemical Vapor Deposition and the Effects on Vertical Devices,” Crystals 2023, Vol. 13, Page 387, vol. 13, no. 3, p. 387, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Zhai et al., “Epitaxial growth of highly symmetrical branched noble metal-semiconductor heterostructures with efficient plasmon-induced hot-electron transfer,” Nature Communications 2023 14:1, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 1–10, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Nozawa, S. Uda, H. Niinomi, J. Okada, and K. Fujiwara, “Heteroepitaxial Growth of Colloidal Crystals: Dependence of the Growth Mode on the Interparticle Interactions and Lattice Spacing,” Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters, vol. 13, no. 30, pp. 6995–7000, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Liu, “Epitaxial Growth of Semiconductor Quantum Dots: An Overview,”, vol. 11, no. 03n04, Jun. 2023 . [CrossRef]

- D. Ren et al., “Quasi van der Waals Epitaxial Growth of GaAsSb Nanowires on Graphitic Substrate for Photonic Applications,” ACS Appl Nano Mater, vol. 7, no. 7, pp. 6797–6803, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. J. C. Irvine, “Film growth and epitaxy methods,” Encyclopedia of Condensed Matter Physics, pp. 248–260, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. Heyn, “Epitaxy (classical MBE),” Encyclopedia of Condensed Matter Physics, pp. 544–553, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. E. Suyolcu and G. Logvenov, “Precise control of atoms with MBE: from semiconductors to complex oxides,” Europhysics News, vol. 51, no. 4, pp. 21–23, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. W. Tu, “Molecular Beam Epitaxy,” The Handbook of Surface Imaging and Visualization, pp. 433–447, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. C. A. Tam, “Molecular Beam Epitaxial Growth Optimization for Next Generation Optoelectronic Devices Based on III-V Semiconductors,” Sep. 01, 2020, University of Waterloo. Accessed: Aug. 24, 2024. [Online]. Available: http://hdl.handle.net/10012/16221.

- J. Liang, X. Zhu, M. Chen, X. Duan, D. Li, and A. Pan, “Controlled Growth of Two-Dimensional Heterostructures: In-Plane Epitaxy or Vertical Stack,” Acc Mater Res, vol. 3, no. 10, pp. 999–1010, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. G. Mauk, “Liquid-Phase Epitaxy,” digital Encyclopedia of Applied Physics, pp. 1–31, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Kosaki, N. Uene, T. Mabuchi, and T. Tokumasu, “Multi-Scale Simulations of Gas-Phase Particles Generated in Plasma Enhanced Atomic Layer Deposition Processes,” ECS Meeting Abstracts, vol. MA2023-02, no. 29, p. 1510, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. Rasic, J. Narayan, D. Rasic, and J. Narayan, “Epitaxial Growth of Thin Films,” Crystal Growth, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- H. Vilchis, C. Camas, J. Conde, H. Vilchis, C. Camas, and J. Conde, “Epitaxial Growth of Semiconductor Alloys by Computational Modeling,” Advances in Semiconductor Physics and Devices [Working Title], Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. F. Ince et al., “Development of ‘GaSb-on-silicon’ metamorphic substrates for optoelectronic device growth,” Journal of Vacuum Science & Technology B, vol. 42, no. 1, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Hakami, C. C. Tseng, K. Nanjo, V. Tung, and J. H. Fu, “Wafer-scale epitaxy of transition-metal dichalcogenides with continuous single-crystallinity and engineered defect density,” MRS Bull, vol. 48, no. 9, pp. 923–931, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. Fu, H. Fu, B. Setera, and A. Christou, “Challenges of Overcoming Defects in Wide Bandgap Semiconductor Power Electronics,” Electronics 2022, Vol. 11, Page 10, vol. 11, no. 1, p. 10, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Ganose, D. O. Scanlon, A. Walsh, and R. L. Z. Hoye, “The defect challenge of wide-bandgap semiconductors for photovoltaics and beyond,” Nat Commun, vol. 13, no. 1, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Wang et al., “Wafer-Scale Epitaxial Growth of Two-dimensional Organic Semiconductor Single Crystals toward High-Performance Transistors,” Advanced Materials, vol. 35, no. 36, p. 2301017, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Jalil et al., “Phase-Selective Epitaxy of Trigonal and Orthorhombic Bismuth Thin Films on Si (111),” Nanomaterials, vol. 13, no. 14, p. 2143, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. B. Yakimov, Y. O. Kulanchikov, and P. S. Vergeles, “An Experimental Study of Dislocation Dynamics in GaN,” Micromachines 2023, Vol. 14, Page 1190, vol. 14, no. 6, p. 1190, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Quevedo et al., “Dislocation half-loop control for optimal V-defect density in GaN-based light emitting diodes,” Appl Phys Lett, vol. 125, no. 4, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Benbedra et al., “Energetics, electronic structure and electric polarization of basal stacking faults in wurtzite GaN and ZnO,” Nov. 2023, Accessed: Aug. 25, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2311.17773v1.

- G. Naselli et al., “Nontrivial gapless electronic states at the stacking faults of weak topological insulators,” Phys Rev B, vol. 106, no. 9, p. 094105, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. J. Pearton, “Electronic properties of dopants and defects in widegap and ultra-widegap semiconductors and alloys,” Reference Module in Materials Science and Materials Engineering, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Z. P. Wang et al., “Performance limiting inhomogeneities of defect states in ampere-class Ga2O3 power diodes,” Appl Phys Rev, vol. 11, no. 2, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Lou and F. Xiao, “Performance evaluation and stability analysis of super-junction IGBTs in high-temperature environments,” J Phys Conf Ser, vol. 2797, no. 1, p. 012024, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Q. Zhang, X. Yin, E. Martel, and S. Zhao, “Molecular beam epitaxy growth and characterization of AlGaN epilayers in nitrogen-rich condition on Si substrate,” Mater Sci Semicond Process, vol. 135, p. 106099, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. Liu, Y. Y. Lai, H. C. Chen, A. P. Chiu, and H. C. Kuo, “A Brief Overview of the Rapid Progress and Proposed Improvements in Gallium Nitride Epitaxy and Process for Third-Generation Semiconductors with Wide Bandgap,” Micromachines (Basel), vol. 14, no. 4, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. Wangila et al., “Growth of Germanium Thin Films on Sapphire Using Molecular Beam Epitaxy,” Crystals (Basel), vol. 13, no. 11, p. 1557, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- W. Nunn, T. K. Truttmann, and B. Jalan, “A review of molecular-beam epitaxy of wide bandgap complex oxide semiconductors,” Journal of Materials Research 2021 36:23, vol. 36, no. 23, pp. 4846–4864, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Shen et al., “Development of in situ characterization techniques in molecular beam epitaxy,” Journal of Semiconductors, vol. 45, no. 3, p. 031301, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Pant, D. K. Singh, A. M. Chowdhury, B. Roul, K. K. Nanda, and S. B. Krupanidhi, “Next-generation self-powered and ultrafast photodetectors based on III-nitride hybrid structures,” APL Mater, vol. 8, no. 2, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Dziwoki et al., “The Use of External Fields (Magnetic, Electric, and Strain) in Molecular Beam Epitaxy—The Method and Application Examples,” Molecules 2024, Vol. 29, Page 3162, vol. 29, no. 13, p. 3162, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. V. Sorokin et al., “Molecular Beam Epitaxy of Layered Group III Metal Chalcogenides on GaAs(001) Substrates,” Materials 2020, Vol. 13, Page 3447, vol. 13, no. 16, p. 3447, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Sabzi et al., “A Review on Sustainable Manufacturing of Ceramic-Based Thin Films by Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD): Reactions Kinetics and the Deposition Mechanisms,” Coatings 2023, Vol. 13, Page 188, vol. 13, no. 1, p. 188, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Alsmadi and S. Farahneh, “Enhancing the efficacy of thin films via chemical Vapor deposition techniques,” International Journal of Electronic Devices and Networking, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 01–04, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Wei et al., “Deposition of diamond films by microwave plasma CVD on 4H-SiC substrates,” Mater Res Express, vol. 10, no. 12, p. 126404, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Sun et al., “Chemical vapour deposition,” Nature Reviews Methods Primers 2021 1:1, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 1–20, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. T. Wang, “Chemical Vapor Deposition and Its Applications in Inorganic Synthesis,” Modern Inorganic Synthetic Chemistry: Second Edition, pp. 167–188, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Rifai, S. Houshyar, and K. Fox, “Progress towards 3D-printing diamond for medical implants: A review,” Annals of 3D Printed Medicine, vol. 1, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Vernardou, “Special Issue: Advances in Chemical Vapor Deposition,” Materials 2020, Vol. 13, Page 4167, vol. 13, no. 18, p. 4167, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- L.-Q. Xia and M. Chang, “Chemical Vapor Deposition*,” Handbook of Semiconductor Manufacturing Technology, pp. 13–1, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wu, C. Herrera, A. Hardy, M. Muehle, T. Zimmermann, and T. A. Grotjohn, “Diamond Metal-Semiconductor Field Effect Transistor for High Temperature Applications,” Device Research Conference - Conference Digest, DRC, vol. 2019-June, pp. 155–156, Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Ohmagari, “Single-crystal diamond growth by hot-filament CVD: a recent advances for doping, growth rate and defect controls,” Functional Diamond, vol. 3, no. 1, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. J. Wellmann, “Power Electronic Semiconductor Materials for Automotive and Energy Saving Applications – SiC, GaN, Ga2O3, and Diamond,” Z Anorg Allg Chem, vol. 643, no. 21, pp. 1312–1322, Nov. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Z. Chu, B. Xu, and J. Liang, “Direct Application of Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) Grown by Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) for Integrated Circuits (ICs) Interconnection: Challenges and Developments,” Nanomaterials 2023, Vol. 13, Page 2791, vol. 13, no. 20, p. 2791, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. NUNOMURA and M. KONDO, “プラズマCVD法によるシリコン系薄膜の成長:気相・表面・膜中の反応と薄膜の高品質化,” 表面と真空, vol. 67, no. 2, pp. 44–51, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Chatterjee, T. Abadie, M. Wang, O. K. Matar, and R. S. Ruoff, “Repeatability and Reproducibility in the Chemical Vapor Deposition of 2D Films: A Physics-Driven Exploration of the Reactor Black Box,” Chemistry of Materials, vol. 36, no. 3, pp. 1290–1298, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. Jumaah and Y. Jaluria, “Manufacturing of Gallium Nitride Thin Films in a Multi-Wafer MOCVD Reactor,” J Therm Sci Eng Appl, vol. 15, no. 6, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. Jumaah and Y. Jaluria, “Experimental Study of the Effect of Precursor Composition on the Microstructure of Gallium Nitride Thin Films Grown by the MOCVD Process,” J Heat Transfer, vol. 143, no. 10, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Longo, “Special Issue ‘Thin Films and Nanostructures by MOCVD: Fabrication, Characterization and Applications—Volume II,’” Coatings 2023, Vol. 13, Page 428, vol. 13, no. 2, p. 428, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, Z. Chen, K. Zhang, Z. Feng, and H. Zhao, “Laser-Assisted Metal–Organic Chemical Vapor Deposition of Gallium Nitride,” physica status solidi (RRL) – Rapid Research Letters, vol. 15, no. 6, p. 2170024, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Liu, S. Zhou, K. Wang, Z. Chen, Z. Gan, and X. Luo, “Several co-design issues using DfX for solid state lighting,” ICEPT-HDP 2011 Proceedings - 2011 International Conference on Electronic Packaging Technology and High Density Packaging, pp. 7–11, 2011. [CrossRef]

- J. Li et al., “Study on the optimization of the deposition rate of planetary GaN-MOCVD films based on CFD simulation and the corresponding surface model,” R Soc Open Sci, vol. 5, no. 2, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Venugopalarao et al., “Metal-Organic Chemical Vapor Deposition Grown Low-Temperature Aluminum Nitride Gate Dielectric for Gallium Nitride on Si High Electron Mobility Transistor,” physica status solidi (a), p. 2400050, 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Chen, S. Zhang, T. Yang, T. Mi, X. Wang, and C. Liu, “MOCVD Growth and Fabrication of Vertical P-i-N and Schottky Power Diodes Based on Ultra-wide Bandgap AlGaN Epitaxial Structures,” Proceedings of the International Symposium on Power Semiconductor Devices and ICs, pp. 295–298, 2024. [CrossRef]

- F. Alema and A. Osinsky, “Metalorganic Chemical Vapor Deposition 1,” Springer Series in Materials Science, vol. 293, pp. 141–170, 2020. [CrossRef]

- V. Ershov, A. V. Fomin, S. K. Nazhmetov, A. A. Naidin, O. A. Rogachkov, and M. V. Lupachev, “The influence of growth parameters of AlGaAs waveguide layers grown by MOCVD on the output characteristics of high-power laser diodes,” 2022 International Conference Laser Optics, ICLO 2022 - Proceedingss, 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Yang et al., “From Challenges to Solutions, Heteroepitaxy of GaAs-Based Materials on Si for Si Photonics,” Thin Films - Growth, Characterization and Electrochemical Applications, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. Matsumoto et al., “Opportunities and challenges in GaN metal organic chemical vapor deposition for electron devices,” Jpn J Appl Phys, vol. 55, no. 5, p. 05FK04, May 2016. [CrossRef]

- K. Matsumoto et al., “Challenges and opportunities of MOVPE and THVPE/HVPE for nitride light emitting device,”, , vol. 11302, pp. 73–80, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- V. Voronenkov et al., “Hydride Vapor-Phase Epitaxy Reactor for Bulk GaN Growth,” physica status solidi (a), vol. 217, no. 3, p. 1900629, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y.-M. Zhang et al., “Growth and doping of bulk GaN by hydride vapor phase epitaxy*,” Chinese Physics B, vol. 29, no. 2, p. 026104, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Hu et al., “Growth of Freestanding Gallium Nitride (GaN) Through Polyporous Interlayer Formed Directly During Successive Hydride Vapor Phase Epitaxy (HVPE) Process,” Crystals 2020, Vol. 10, Page 141, vol. 10, no. 2, p. 141, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Hu et al., “Hydride vapor phase epitaxy for gallium nitride substrate,” Journal of Semiconductors, vol. 40, no. 10, p. 101801, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- L. Liu et al., “Nucleation mechanism of GaN crystal growth on porous GaN/sapphire substrates,” CrystEngComm, vol. 24, no. 10, pp. 1840–1848, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Xia, Y. Zhang, J. Wang, J. Chen, and K. Xu, “HVPE growth of bulk GaN with high conductivity for vertical devices,” Semicond Sci Technol, vol. 36, no. 1, p. 014009, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Sumiya et al., “Fabrication of AlGaN/GaN heterostructures on halide vapor phase epitaxy AlN/SiC templates for high electron mobility transistor application,” Jpn J Appl Phys, vol. 62, no. 8, p. 085501, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. A. Freitas et al., “(Invited) Optical Characterization of Bulk GaN Substrates and Homoepitaxial Films,” ECS Meeting Abstracts, vol. MA2022-02, no. 37, p. 1359, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wu et al., “Optimizing HVPE flow field to achieve GaN crystal uniform growth,” J Cryst Growth, vol. 614, p. 127214, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Dhaka, A. Yadav, G. Gupta, S. Dutta, and A. K. Shukla, “Growth of β-Ga2O3 nanostructures by thermal oxidation of GaN-on-sapphire for optoelectronic devices applications,” J Alloys Compd, vol. 997, p. 174789, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- G. Scheen et al., “GaN-on-Porous Silicon for RF Applications,” 2023 53rd European Microwave Conference, EuMC 2023, pp. 842–845, 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. Sun, Z. Wang, S. Wang, and S. Zhang, “Morphology evolution of homoepitaxial growth of aluminum nitride by hydride vapor phase epitaxy,” J Cryst Growth, vol. 627, p. 127503, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Oshima et al., “Ultra-High-Speed Growth of GaAs Solar Cells by Triple-Chamber Hydride Vapor Phase Epitaxy,” Crystals 2023, Vol. 13, Page 370, vol. 13, no. 3, p. 370, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. A. Galván Montalvo, C. V. Silva Juárez, V. H. Compeán Jasso, F. De Anda Salazar, V. Michournyi, and A. Gorbatchev, “Analysis of thermodynamic conditions to grow GaAsP epitaxial layers by LPE on GaAs and GaP substrates,” MRS Adv, vol. 5, no. 63, pp. 3327–3335, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y.-H. Rao et al., “Liquid phase epitaxy magnetic garnet films and their applications*,” Chinese Physics B, vol. 27, no. 8, p. 086701, Aug. 2018. [CrossRef]

- T. Mahi and K. Nakajima, “Liquid Phase Epitaxy,” Reference Module in Materials Science and Materials Engineering, Jan. 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. G. Mauk, “Liquid-Phase Epitaxy,” Handbook of Crystal Growth: Thin Films and Epitaxy: Second Edition, vol. 3, pp. 225–316, Jan. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liu et al., “Strain induced anisotropy in liquid phase epitaxy grown nickel ferrite on magnesium gallate substrates,” Sci Rep, vol. 12, no. 1, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- I. Maronchuk, I. E. Maronchuk, D. D. Sankovitch, K. Lovchinov, and D. Dimova-Malinovska, “Deposition by liquid epitaxy and study of the properties of nano-heteroepitaxial structures with quantum dots for high efficient solar cells,” J Phys Conf Ser, vol. 558, no. 1, p. 012049, Dec. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Graniel, J. Puigmartí-Luis, and D. Muñoz-Rojas, “Liquid atomic layer deposition as emergent technology for the fabrication of thin films,” Dalton Transactions, vol. 50, no. 19, pp. 6373–6381, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liu, H. Zhang, and S. Kang, “Emerging Atomic Layer Deposition Technology toward High-k Gate Dielectrics, Energy, and Photocatalysis Applications,” Energy Technology, vol. 11, no. 10, p. 2300289, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. Solanki, C. He, Y. Lim, R. Yanagi, and S. Hu, “Where Atomically Precise Catalysts, Optoelectronic Devices, and Quantum Information Technology Intersect: Atomic Layer Deposition†,” Chemistry of Materials, vol. 36, no. 3, pp. 1013–1024, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Molina-Reyes, “Atomic-layer deposition for development of advanced electron devices,” 2022 IEEE International Conference on Engineering Veracruz, ICEV 2022, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. J. A. Zaidi et al., “Interfaces in Atomic Layer Deposited Films: Opportunities and Challenges,” Small Science, vol. 3, no. 10, p. 2300060, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Muhler, “atomic layer deposition,” Catalysis from A to Z, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Qu et al., “Development and Prospect of Process Models and Simulation Methods for Atomic Layer Deposition,” Journal of Microelectronic Manufacturing, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 1–6, 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. B. Suyatin, R. J. Jam, M. Karimi, S. A. Khan, and J. Sundqvist, “(Invited) ALE Based Manufacturing of Nanostructures below 20 Nm,” ECS Meeting Abstracts, vol. MA2022-02, no. 31, p. 1115, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- B. Karasulu, “(Invited) Atomistic Insights into Continuous and Area-Selective ALD Processes: First-Principles Simulations of the Underpinning Surface Chemistry,” ECS Meeting Abstracts, vol. MA2023-02, no. 29, p. 1458, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Zhuiykov, Z. Hai, E. Kats, M. K. Akbari, and C. Xue, “Atomic Layer Deposition of Ultra-Thin Oxide Semiconductors: Challenges and Opportunities,” Key Eng Mater, vol. 735, pp. 215–218, 2017. [CrossRef]

- H. Xu, M. K. Akbari, S. Kumar, F. Verpoort, and S. Zhuiykov, “Atomic layer deposition – state-of-the-art approach to nanoscale hetero-interfacial engineering of chemical sensors electrodes: A review,” Sens Actuators B Chem, vol. 331, p. 129403, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Pan, L. Zhou, W. Zheng, X. Liu, J. Zhang, and N. Pinna, “Atomic layer deposition to heterostructures for application in gas sensors,” International Journal of Extreme Manufacturing, vol. 5, no. 2, p. 022008, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Z. Li, X. Zhao, S. Wu, M. Lu, X. Xie, and J. Yan, “Atomic Layer Deposition of Transition-Metal Dichalcogenides,” Cryst Growth Des, vol. 24, no. 5, pp. 1865–1879, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Aspiotis et al., “Scalable, Highly Crystalline, 2D Semiconductor Atomic Layer Deposition Process for High Performance Electronic Applications,” Mar. 2022, Accessed: Nov. 07, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2203.10309v1.

- Y. Kim et al., “Atomic-Layer-Deposition-Based 2D Transition Metal Chalcogenides: Synthesis, Modulation, and Applications,” Advanced Materials, vol. 33, no. 47, p. 2005907, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Baek, S. Kim, S. A. Han, Y. H. Kim, S. Kim, and J. H. Kim, “Synthesis Strategies and Nanoarchitectonics for High-Performance Transition Metal Dichalcogenide Thin Film Field-effect Transistors,” ChemNanoMat, vol. 9, no. 7, p. e202300104, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Mattinen et al., “Van der Waals epitaxy of continuous thin films of 2D materials using atomic layer deposition in low temperature and low vacuum conditions,” 2d Mater, vol. 7, no. 1, p. 011003, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- X. Meng et al., “Atomic Layer Deposition of Silicon Nitride Thin Films: A Review of Recent Progress, Challenges, and Outlooks,” Materials 2016, Vol. 9, Page 1007, vol. 9, no. 12, p. 1007, Dec. 2016. [CrossRef]

- T. Muneshwar, M. Miao, E. R. Borujeny, and K. Cadien, “Atomic Layer Deposition: Fundamentals, Practice, and Challenges,” Handbook of Thin Film Deposition: Fourth Edition, pp. 359–377, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- X. Wang, R. Chen, and S. Sun, “Material manufacturing from atomic layer,” International Journal of Extreme Manufacturing, vol. 5, no. 4, p. 043001, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Shepelin, Z. P. Tehrani, N. Ohannessian, C. W. Schneider, D. Pergolesi, and T. Lippert, “A practical guide to pulsed laser deposition,” Chem Soc Rev, vol. 52, no. 7, pp. 2294–2321, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Soonmin, M. Alhajj, and A. Tubtimtae, “Recent Advances in the Development of Pulsed Laser Deposited Thin Films,” Springer Proceedings in Materials, vol. 44, pp. 80–93, 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Delmdahl, L. de Vreede, B. Berenbak, and A. Janssens, “Pulsed laser deposition – materials that matter,” PhotonicsViews, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 45–47, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Lorenz, H. Hochmuth, H. von Wenckstern, and M. Grundmann, “Flexible hardware concept of pulsed laser deposition for large areas and combinatorial composition spreads,” Review of Scientific Instruments, vol. 94, no. 8, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Lysne, T. Brakstad, M. Kildemo, and T. Reenaas, “Improved methods for design of PLD and combinatorial PLD films,” J Appl Phys, vol. 132, no. 12, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Gaudiuso, “Pulsed Laser Deposition of Carbon-Based Materials: A Focused Review of Methods and Results,” Processes 2023, Vol. 11, Page 2373, vol. 11, no. 8, p. 2373, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Virt, P. Potera, and B. Cieniek, “Laser Growth of Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotube Thin Films,” Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 12th International Conference “Nanomaterials: Applications and Properties”, NAP 2022, 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Lysne, T. Brakstad, M. Kildemo, and T. Reenaas, “Improved methods for design of PLD and combinatorial PLD films,” J Appl Phys, vol. 132, no. 12, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Kim and A. Piqué, “Laser Processing of Energy Storage Materials,” Encyclopedia of Materials: Technical Ceramics and Glasses: Volume 1-3, vol. 3, pp. 59–73, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. N. Ogugua, O. M. Ntwaeaborwa, and H. C. Swart, “Latest Development on Pulsed Laser Deposited Thin Films for Advanced Luminescence Applications,” Coatings 2020, Vol. 10, Page 1078, vol. 10, no. 11, p. 1078, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. V. Sorokin, I. Ahmad, A. N. Khodan, and S. O. Aisida, “Pulsed laser deposition of epitaxial films: : phase-field description,” Proceedings of 2022 19th International Bhurban Conference on Applied Sciences and Technology, IBCAST 2022, pp. 10–13, 2022. [CrossRef]

- V. O. Anyanwu and M. K. Moodley, “PLD of transparent and conductive AZO thin films,” Ceram Int, vol. 49, no. 3, pp. 5311–5318, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Conde Garrido and J. M. Silveyra, “A review of typical PLD arrangements: Challenges, awareness, and solutions,” Opt Lasers Eng, vol. 168, p. 107677, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Duta and I. N. Mihailescu, “Advances and Challenges in Pulsed Laser Deposition for Complex Material Applications,” Coatings 2023, Vol. 13, Page 393, vol. 13, no. 2, p. 393, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Kumar et al., “Wide Band Gap Devices and Their Application in Power Electronics,” Energies 2022, Vol. 15, Page 9172, vol. 15, no. 23, p. 9172, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- ahsanali S. A. A. Shah, “Overview of Power Electronic Devices & its Application Specifically Wide Band Gap and GaN HEMTs,” International Journal of Sciences and Emerging Technologies, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 39–49, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Forte and A. Spampinato, “High Power-Density Design Based on WBG GaN Devices for Three-Phase Motor Drives,” 2024 International Symposium on Power Electronics, Electrical Drives, Automation and Motion, SPEEDAM 2024, pp. 65–70, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Gao, “Advancements and future prospects of Gallium Nitride (GaN) in semiconductor technology,” Applied and Computational Engineering, vol. 65, no. 1, pp. 37–44, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- X. An and K. H. Li, “GaN-based integrated optical devices for wide-scenario sensing applications,” Nanoelectronic Devices and Applications, pp. 29–71, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- P. T. P. T. Nguyen, R. T. Velpula, M. Patel, B. Jain, and A. Marangon, “(Invited) Enhanced Efficiency of AlInN Nanowire Ultraviolet Light-Emitting Diodes Using Photonic Crystal Structures,” ECS Meeting Abstracts, vol. MA2022-02, no. 36, p. 1301, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. Kizilyalli, O. B. Spahn, and E. P. Carlson, “(Invited) Recent Progress in Wide-Bandgap Semiconductor Devices for a More Electric Future,” ECS Meeting Abstracts, vol. MA2022-02, no. 37, p. 1344, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Razzak et al., “Ultra-wide band gap materials for high frequency applications,” 2018 IEEE MTT-S International Microwave Workshop Series on Advanced Materials and Processes for RF and THz Applications, IMWS-AMP 2018, Sep. 2018. [CrossRef]

- C. Joishi, N. K. Kalarickal, W. Rahman, W. Lu, and S. Rajan, “Ultra-Wide Bandgap Semiconductor Transistors for mm-wave Applications,” Device Research Conference - Conference Digest, DRC, vol. 2022-June, 2022. [CrossRef]

- W. Zhao et al., “X-band epi-BAW resonators,” J Appl Phys, vol. 132, no. 2, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. Kim and S. Jeon, “W- And G-Band GaN Voltage-Controlled Oscillators with High Output Power and High Efficiency,” IEEE Trans Microw Theory Tech, vol. 69, no. 8, pp. 3908–3916, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Heilmann, V. Deinhart, A. Tahraoui, K. Höflich, and J. M. J. Lopes, “Spatially controlled epitaxial growth of 2D heterostructures via defect engineering using a focused He ion beam,” npj 2D Materials and Applications 2021 5:1, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 1–7, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- T. A. Pham et al., “Nanoarchitectonics for Wide Bandgap Semiconductor Nanowires: Toward the Next Generation of Nanoelectromechanical Systems for Environmental Monitoring,” Advanced Science, vol. 7, no. 21, p. 2001294, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- B. Liu et al., “Defect-induced nucleation and epitaxy: A new strategy toward the rational synthesis of WZ-GaN/3C-SiC core-shell heterostructures,” Nano Lett, vol. 15, no. 12, pp. 7837–7846, Dec. 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. H. Choi, Y. Kim, I. Jeon, and H. Kim, “Heterogeneous Integration of Wide Bandgap Semiconductors and 2D Materials: Processes, Applications, and Perspectives,” Advanced Materials, p. 2411108, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Saravanan, B. R. Huang, D. Kathiravan, S. Sakalley, and S. C. Chen, “Tunable defect-engineered nanohybrid heterostructures: exfoliated 2D WSe2–MoS2 nanohybrid sheet covered on 1D ZnO nanostructures for self-powered UV photodetectors,” J Mater Chem C Mater, vol. 11, no. 18, pp. 6082–6088, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Kujofsa and J. E. Ayers, “Strain compensation in a semiconducting device structure using an intentionally mismatched uniform buffer layer,” Semicond Sci Technol, vol. 31, no. 12, p. 125005, Nov. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Bosi et al., “Defect structure and strain reduction of 3C-SiC/Si layers obtained with the use of a buffer layer and methyltrichlorosilane addition,” CrystEngComm, vol. 18, no. 15, pp. 2770–2779, Apr. 2016. [CrossRef]

- B. Leung, J. Han, and Q. Sun, “Strain relaxation and dislocation reduction in AlGaN step-graded buffer for crack-free GaN on Si (111),” physica status solidi (c), vol. 11, no. 3–4, pp. 437–441, Feb. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Y. Cho et al., “Threading dislocation reduction in a GaN film with a buffer layer grown at an intermediate temperature,” Journal of the Korean Physical Society, vol. 66, no. 2, pp. 214–218, Feb. 2015. [CrossRef]

- R. R. Reznik et al., “Molecular-Beam Epitaxy Growth and Properties of AlGaAs Nanowires with InGaAs Nanostructures,” physica status solidi (RRL) – Rapid Research Letters, vol. 16, no. 7, p. 2200056, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Lozano and V. J. Gómez, “Epitaxial growth of crystal phase quantum dots in III–V semiconductor nanowires,” Nanoscale Adv, vol. 5, no. 7, pp. 1890–1909, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- X. Meng and J. W. Elam, “Synthesis of nanostructured materials via atomic and molecular layer deposition,” Encyclopedia of Nanomaterials, pp. 2–23, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. Kaloyeros, J. Goff, and B. Arkles, “Emerging Molecular and Atomic Level Techniques for Nanoscale Applications,” Electrochemical Society Interface, vol. 27, no. 4, pp. 59–63, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- T. D. H. Nguyen et al., “Open issues and future challenges,” Fundamental Physicochemical Properties of Germanene-related Materials, pp. 491–519, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Mackus, M. J. M. Merkx, and W. M. M. Kessels, “From the Bottom-Up: Toward Area-Selective Atomic Layer Deposition with High Selectivity †,” Chemistry of Materials, vol. 31, no. 1, pp. 2–12, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Saeed, Y. Alshammari, S. A. Majeed, and E. Al-Nasrallah, “Chemical Vapour Deposition of Graphene—Synthesis, Characterisation, and Applications: A Review,” Molecules, vol. 25, no. 17, p. 3856, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Pal, A. Kumar, and G. Saini, “Futuristic frontiers in science and technology: Advancements, requirements, and challenges of multi-approach research,” Journal of Autonomous Intelligence, vol. 7, no. 1, 2024. [CrossRef]

- X. Wang, C. Qiu, X. Ren, Z. Xiong, V. C. M. Leung, and D. Niyato, “Research Challenges and Future Directions,” Wireless Networks (United Kingdom), pp. 105–108, 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. M. Zhao, Y. Chen, Y. Yu, Q. Li, M. Davanco, and J. Liu, “Advanced technologies for quantum photonic devices based on epitaxial quantum dots,” Adv Quantum Technol, vol. 3, no. 2, p. 10.1002/qute.201900034, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

| Property | 4H-SiC | GaN | ZnO | In2o3 | IGZO | Ga2O3 | Diamond | AlN |

| Bandgap (eV) | 3.3 | 3.4 | 3.37 | 3.7 | 3.5 | 4.9 | 5.5 | 6.0 |

| Breakdown field (MV/cm) | 3.1 | 4.9 | 0.01 | NA | 2.7 | 10.3 | 4.4 | 15.4 |

| Sat. velocity (107cm/s) | 2.2 | 1.4 | 3.2 | 0.25 | 0.8 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 1.6 |

| Thermal conductivity (WmK-1) | 490 | 230 | 50 | 2.2 | 1.4 | 13 | 2200 | 320 |

| Johnson FOM ratio vs Si | 278 | 1089 | NA | NA | NA | 2844 | 81000 | 7744 |

| Baliga FOM ratio vs Si | 712 | 3170 | 10 | NA | 3.7 | 4125 | 62954 | 38181 |

| Tunneling eff. Mass (mo) | NA | 0.15 | 0.24 | 0.40 | 0.34 | 0.31 | 0.69 | NA |

| Melting point (oC) | 2730 | 2500 | 1975 | 1910 | 850 | 1700 | 3550 | 2830 |

| Thermal budget | High | High | Low | Low | Low | High | High | High |

| CMOS demonstration status | Cree 2006 | HRL 2016 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Characteristic | Plasma-Enhanced CVD (PECVD) | Hot-filament CVD (HFCVD) | Low-Pressure CVD (LPCVD) | High-Temperature CVD (HTCVD) | Metal-Organic CVD (MOCVD) | Atmospheric Pressure CVD (APCVD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Application | Diamond films | SiC layers | Si nanostructures | SiC for power electronics | Compound semiconductors | General coatings |

| Deposition Rate | Moderate to high | Moderate | High | Variable | Moderate | Variable |

| Deposition Temperature | Low (100 -300°C) | High (800 -1200°C) | Moderate to high (400 -800°C) | Very high (above 1200°C) | Moderate to high (300 - 700°C) | Ambient |

| Pressure | Low to atmospheric | Atmospheric | Low | High | Low to atmospheric | Atmospheric |

| Advantages | High quality, low temperature | Cost-effective, scalable | Uniformity, better control | High-quality crystals | Precise composition control | Simplicity and low cost |

| Disadvantages | Equipment complexity | High temperature requirements | Longer deposition times | Energy-intensive | Toxic precursor materials | Limited control over thickness |

| Cost | Moderate to high | Moderate | Moderate | High | High | Low |

| Film Quality | Excellent uniformity | Good crystalline quality | High uniformity and purity | Exceptional crystal quality | Excellent film properties | Variable quality |

| Material | Growth Rate (μm/h) | Defect Density (cm-2) |

|---|---|---|

| GaN | 1 – 3 | 106 - 108 |

| AlGaN | 0.5 – 2 | 106 - 109 |

| Material | Growth Rate (μm/h) | Application |

|---|---|---|

| GaAs | 5 – 10 | LEDs, solar Cells |

| InP | 1 – 5 | High-Speed electronics |

| Parameter | Value or Range | Effect on Growth |

|---|---|---|

| Laser Fluence | 1J/cm2 to 10J/cm2 | Controls ablation efficiency and film quality |

| Substrate Temperature | 300 – 800oC | Affects crystallinity and morphology |

| Oxygen Pressure (for oxides) | 10-6 Torr to 10-2 Torr | Determines stoichiometry in oxide films |

| Technique | Key Characteristics | Applications | Advantages | Challenges | Scalability | Cost | Uniformity |

| Molecular Beam Epitaxy (MBE) | Utilizes molecular beams in ultra-high vacuum; precise atomic layer control | Quantum wells, superlattices, GaN, SiC, AlGaN | Atomic precision, low contamination, ideal for heterostructures | Slow growth rates, high cost, limited scalability | Limited Scalability | High | Excellent |

| Metal-Organic Chemical Vapor Deposition (MOCVD) | Gas-phase chemical reactions; uses metal-organic precursors | LEDs, laser diodes, solar cells, power devices | High throughput, scalable, versatile for complex structures | High defect density, uniformity issues, toxic precursors | Highly scalable | Moderate | Moderate |

| Hydride Vapor Phase Epitaxy (HVPE) | Involves gas-phase reactions with hydrides; effective for thick layers | Bulk GaN substrates, high-power electronics | High growth rate, suitable for large-area substrates | High defect density, substrate bowing, lattice mismatch | Scalable for thick layers | Moderate | Moderate |

| Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) | Vapor-phase chemical reactions; various types like PECVD and HFCVD | Diamond, SiC, solar cells | Precise control, scalable, applicable to 2D and polymeric films | High precursor cost, temperature-sensitive, uniformity challenges | Highly scalable | Moderate | Variable |

| Liquid Phase Epitaxy (LPE) | Deposition from molten solution, typically high temperature | LEDs, laser diodes, photovoltaic cells | Cost-effective, suitable for thick layers, high purity | Difficult to achieve ultrathin layers, lacks precise layer control | Limited scalability | Low | Moderate |

| Atomic Layer Epitaxy (ALE) | Sequential, self-limiting reactions enable atomic layer precision | Transistors, sensors, quantum wells | Atomic-scale precision, uniformity, ideal for nanostructures | Slow growth rate, complex control, high cost | Limited scalability | High | Excellent |

| Pulsed Laser Deposition (PLD) | High-energy laser ablation of target material, allowing for diverse thin-film compositions | Complex oxides, solar cells, superconductors | High crystalline quality, flexibility in compositions and structures | Requires high energy, scalability issues, film quality variations | Limited scalability | Moderate | Variable |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).