Submitted:

12 April 2025

Posted:

14 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

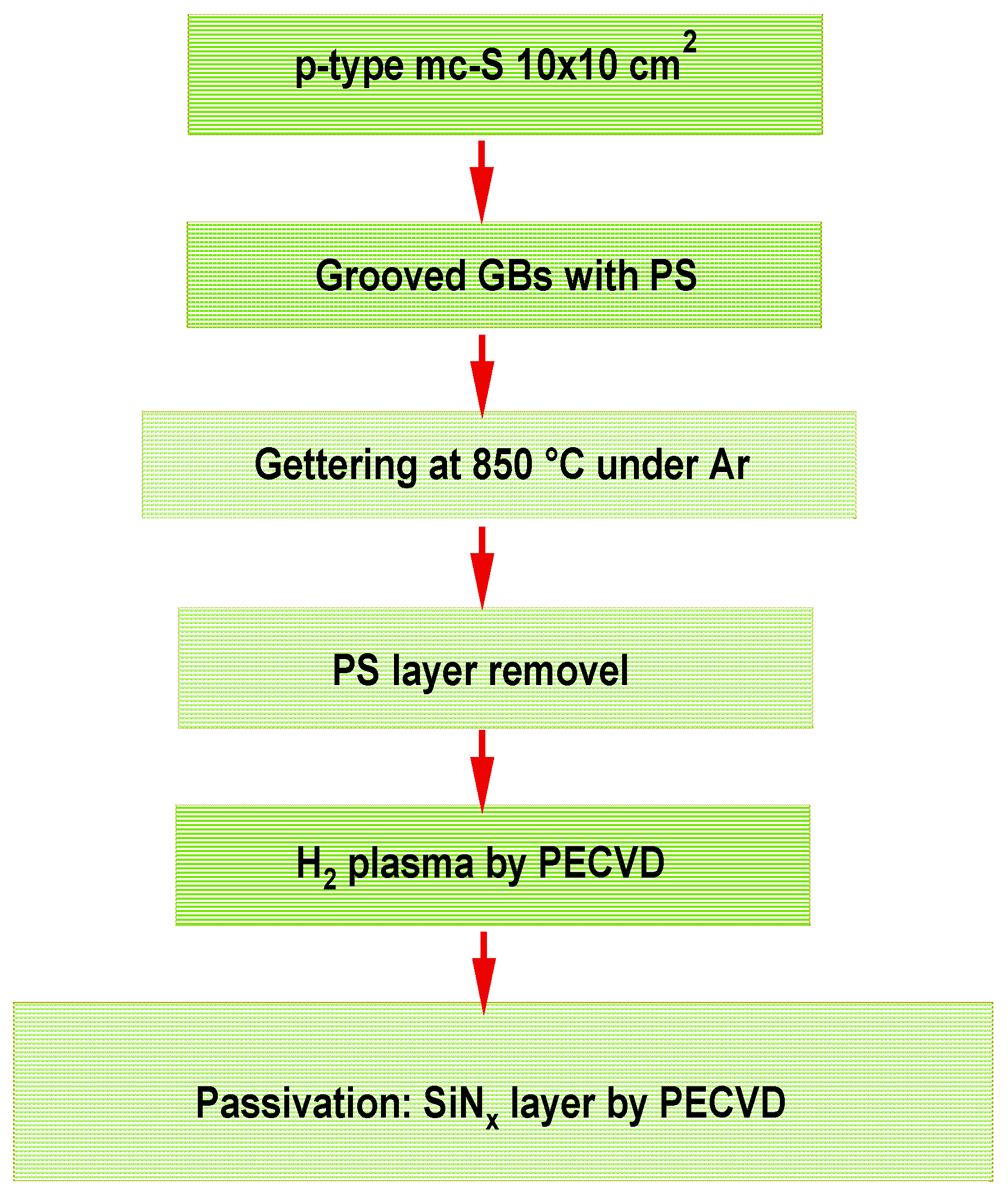

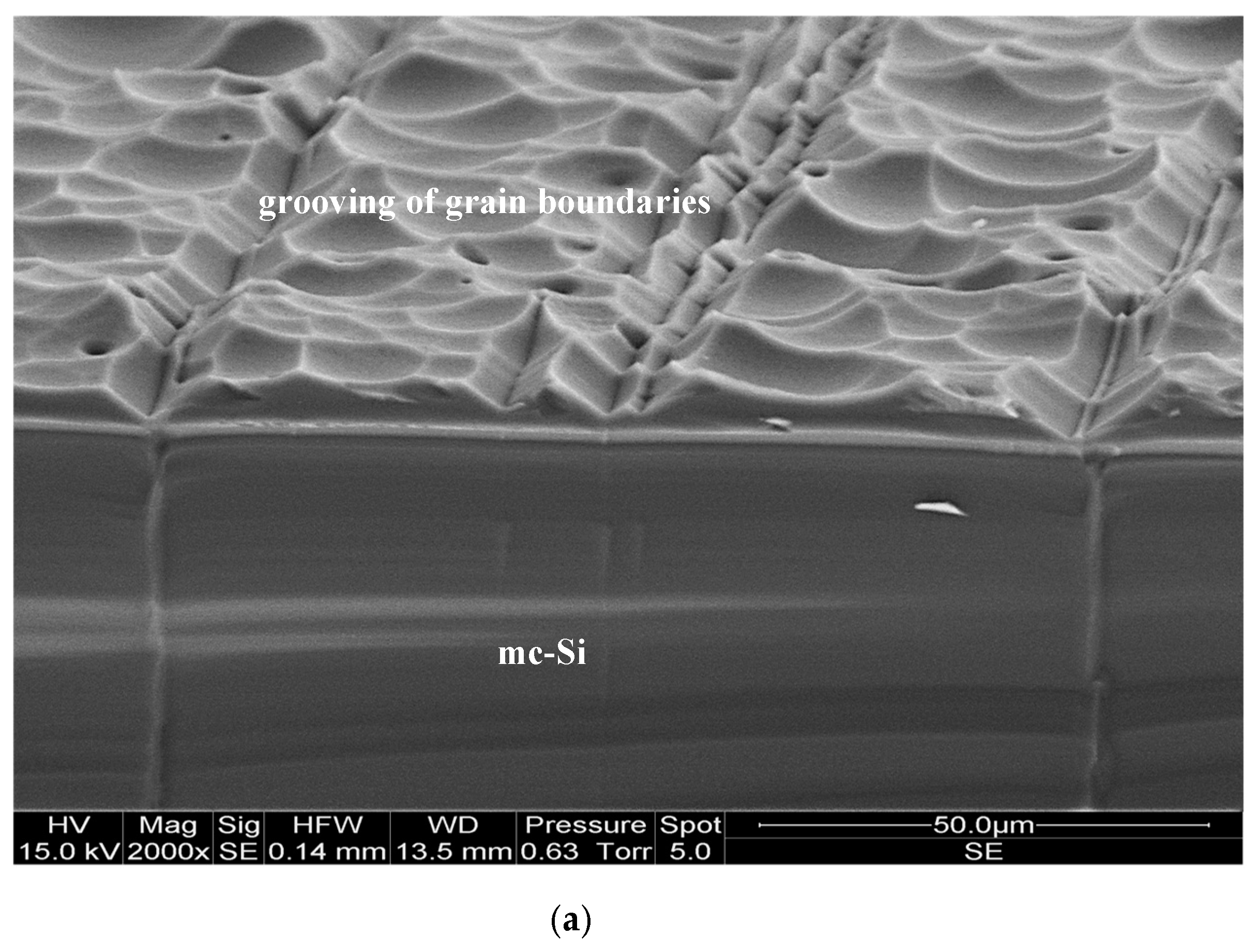

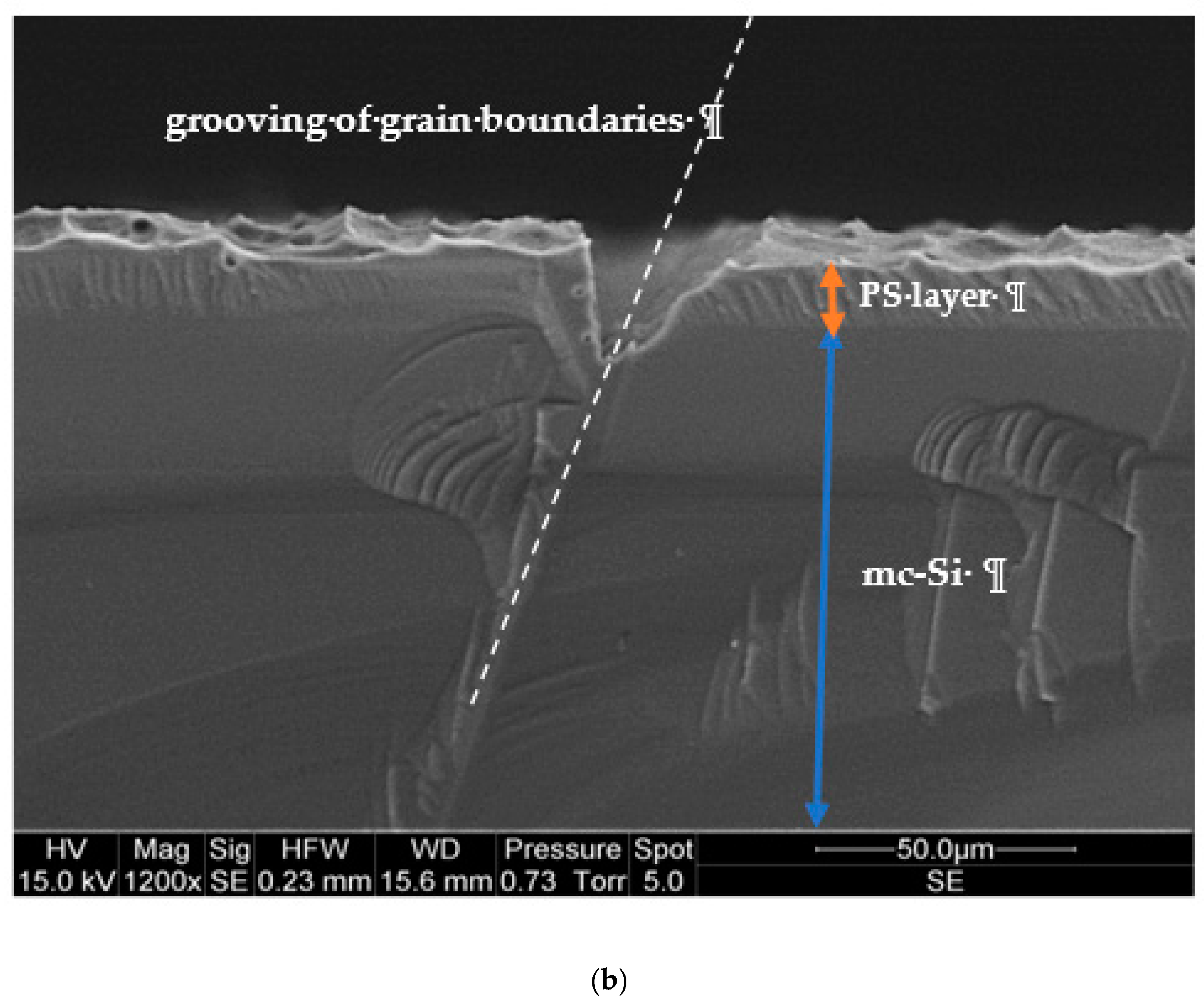

2.1. Samples Preparation for the PECVD Process

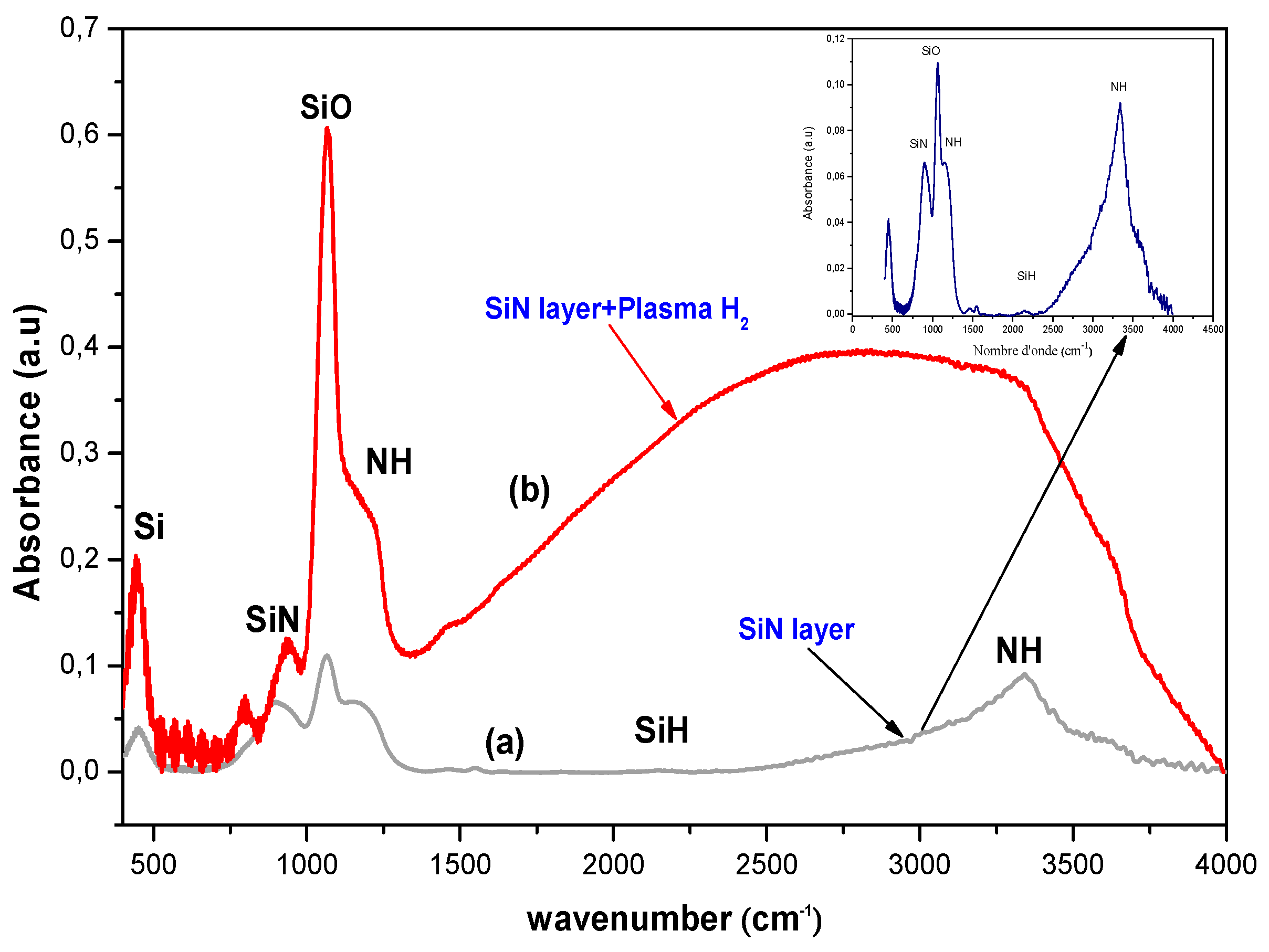

2.2. PECVD Application

2.3. Characterization Tools

3. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ogundipe, O. B.; Okwandu, A. C.; Abdulwaheed, S. A. Recent advances in solar photovoltaic technologies: Efficiency, materials, and applications. GSC Advanced Research and Reviews 2024, 20(1), 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vodapally, S. N.; Ali, M. H. A comprehensive review of solar photovoltaic (PV) technologies, architecture, and its applications to improved efficiency. Energies 2022, 16(1), 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, M.; Masuda, T.; Araki, K.; Sato, D.; Lee, K. H.; Kojima, N.; Yamazaki, M. Development of high-efficiency and low-cost solar cells for PV-powered vehicles application. Progress in Photovoltaics: Research and Applications 2021, 29(7), 684-693.

- Yamaguchi, M.; Dimroth, F.; Geisz, J. F.; Ekins-Daukes, N. J. Multi-junction solar cells paving the way for super high-efficiency. Journal of Applied Physics 2021, 129(24). [CrossRef]

- Green, M. A.; & Bremner, S. P. Energy conversion approaches and materials for high-efficiency photovoltaics. Nature materials 2017, 16(1), 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashraf, M.; Ayaz, M., Khan; M., Adil, S. F.; Farooq, W.; Ullah, N.; Nawaz Tahir, M. Recent trends in sustainable solar energy conversion technologies: mechanisms, prospects, and challenges. Energy & Fuels 2023, 37(9), 6283-6301. [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Xue, Y.; Mei, J.; Zhou, X.; Xiong, M.; Zhang, S. Segregation and removal of transition metal impurities during the directional solidification refining of silicon with Al-Si solvent. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2019, 805, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Li, H.; Ding, D.; Yu, X.; Jin, C.; Yang, D. Interfacial characterization of non-metal precipitates at grain boundaries in cast multicrystalline silicon crystals. Journal of Crystal Growth 2025, 652, 128042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liu, J.; Li, Y.; Wei, G.; Li, Q.; Fan, Z.; He, D. Dislocations in Crystalline Silicon Solar Cells. Advanced Energy and Sustainability Research 2024, 5(2), 2300240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.; Yang, W. C. D.; Ha, D.; Haney, P. M.; Hirsch, D.; Yoon, H. P.; Zhitenev, N.B. Unveiling defect-mediated charge-carrier recombination at the nanometer scale in polycrystalline solar cells. ACS applied materials & interfaces 2019, 11(50), 47037-47046. [CrossRef]

- Dasilva-Villanueva, N.; Catalán-Gómez, S.; Marrón, D. F.; Torres, J. J.; García-Corpas, M.; del Cañizo, C. Reduction of trapping and recombination in upgraded metallurgical grade silicon: impact of phosphorous diffusion gettering. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells 2022, 234, 111410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, J. I.; Nam, S. H.; Kim, L.; An, Y. J. Potential environmental risk of solar cells: Current knowledge and future challenges. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2020, 392, 122297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achref, M.; Khezami, L.; Mokraoui, S.; Rabha, M. B. Effective surface passivation on multi-crystalline silicon using aluminum/porous silicon nanostructures. Surfaces and Interfaces 2020, 18, 100391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabha, M. B.; Salem, M.; El Khakani, M. A.; Bessais, B.; Gaidi, M. Monocrystalline silicon surface passivation by Al2O3/porous silicon combined treatment. Materials Science and Engineering: B 2013, 178(9), 695-697. [CrossRef]

- Khezami, L.; Jemai, A. B.; Alhathlool, R.; Rabha, M. B. Electronic quality improvement of crystalline silicon by stain etching-based PS nanostructures for solar cells application. Solar Energy 2016, 129, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, N.; Ahmad, A.; Sarfaraz, R.; Khalid, S.; Ali, I.; Younas, M.; Rezakazemi, M. Challenges and solutions in solar photovoltaic technology life cycle. ChemBioEng Reviews 2023, 10(4), 541–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrasheedi, N. H. The effects of porous silicon and silicon nitride treatments on the electronic qualities of multicrystalline silicon for solar cell applications. Silicon 2024, 16(4), 1765–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeshaal, M. A.; Abdouli, B.; Choubani, K.; Khezami, L.; Rabha, M. B. Study of porous silicon layer effect in optoelectronics properties of multi-crystalline silicon for photovoltaic applications. Silicon 2023, 15(14), 6025–6032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruska, H.P.; Ghosh, A.K.; Rose, A.; Feng, T. Hall mobility of polycrystalline silicon, Appl. Phys. Lett 1980. 36 (5) 381. [CrossRef]

- Raji, M.; Gurusamy, A.; Manikkam, S.; Perumalsamy, R. Monocrystalline Silicon Wafer Recovery Via Chemical Etching from End-of-Life Silicon Solar Panels for Solar Cell Application. Silicon 2024, 16(9), 3669–3688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousuf, H.; Khokhar, M. Q.; Rahman, R.; Mengmeng, C.; Aida, M. N.; Madara, P. C.; Yi, J. Enhanced field-assisted passivation and optical properties improvement of PECVD deposited SiNx: H thin film. Optical Materials 2025, 162, 116885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukata, N.; Sasaki, S.; Murakami, K.; Ishioka, K.; Nakamura, K. G.; Kitajima, M.; Haneda, H. Hydrogen molecules and hydrogen-related defects in crystalline silicon. Physical Review B 1997, 56(11), 6642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelièvre, J. F.; Fourmond, E.; Kaminski, A.; Palais, O.; Ballutaud, D.; Lemiti, M. Study of the composition of hydrogenated silicon nitride SiNx: H for efficient surface and bulk passivation of silicon. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells 2009, 93(8), 1281–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebib, F., Tomasella, E., Bêche, E., Cellier, J., Jacquet, M. FTIR and XPS investigations of a-SiOxNy thin films structure. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2008, 100, No. 8, p. 082034. IOP Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, H. FTIR and Spectroscopic Ellipsometry Investigations of the Electron Beam Evaporated Silicon Oxynitride Thin Films. Physica B 2011, 406, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, H.; Mitra, S.; Saha, H.; Datta, S. K.; Banerjee, C. Argon plasma treatment of silicon nitride (SiN) for improved antireflection coating on c-Si solar cells. Materials Science and Engineering: B 2017, 215, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, D.; Cuevas, A.; Kinomura, A.; Nakano, Y.; Geerligs, L. J. Transition-metal profiles in a multicrystalline silicon ingot. Journal of Applied Physics 2005, 97(3). [CrossRef]

| Pu (mbar) |

P (mTorr) | T (°C) |

Time (s) |

RF (W) |

SiH4 (sccm) |

NH3 (sccm) | H2 (sccm) | |

| H2 Plasma | 2x10-1 | 700 | 300 | 50 | 60 | - | - | 100 |

| SiNx layer | 2x10-1 | 700 | 300 | 900 | 5 | 3 | 70 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).