Submitted:

17 March 2025

Posted:

18 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

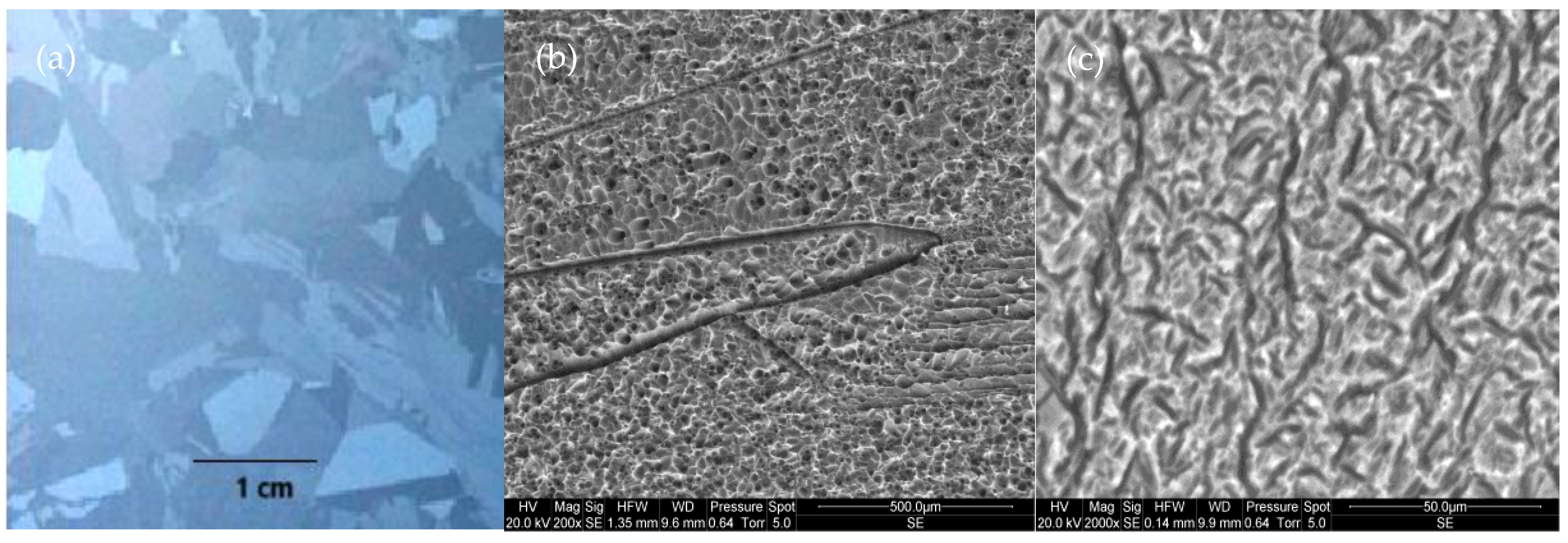

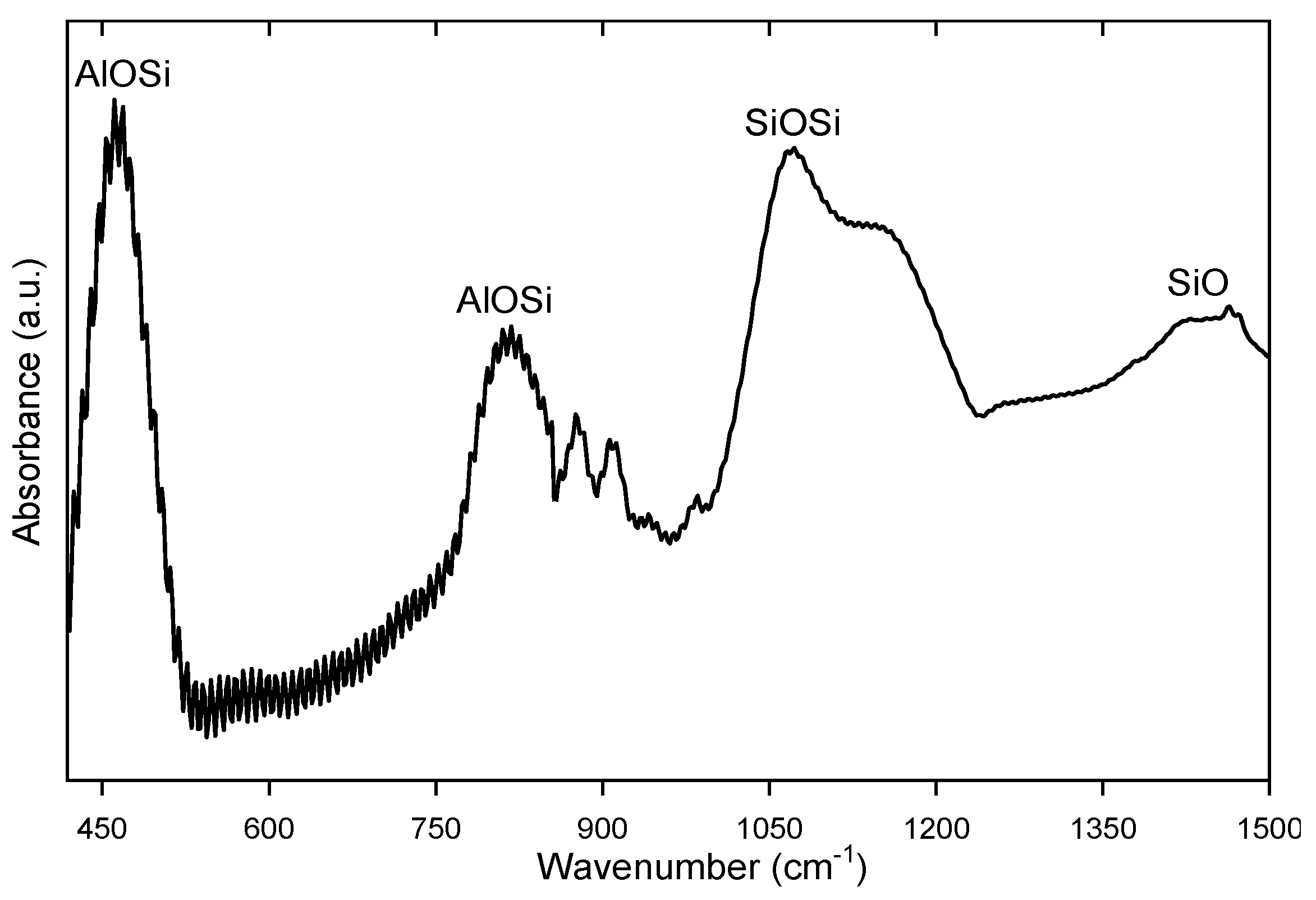

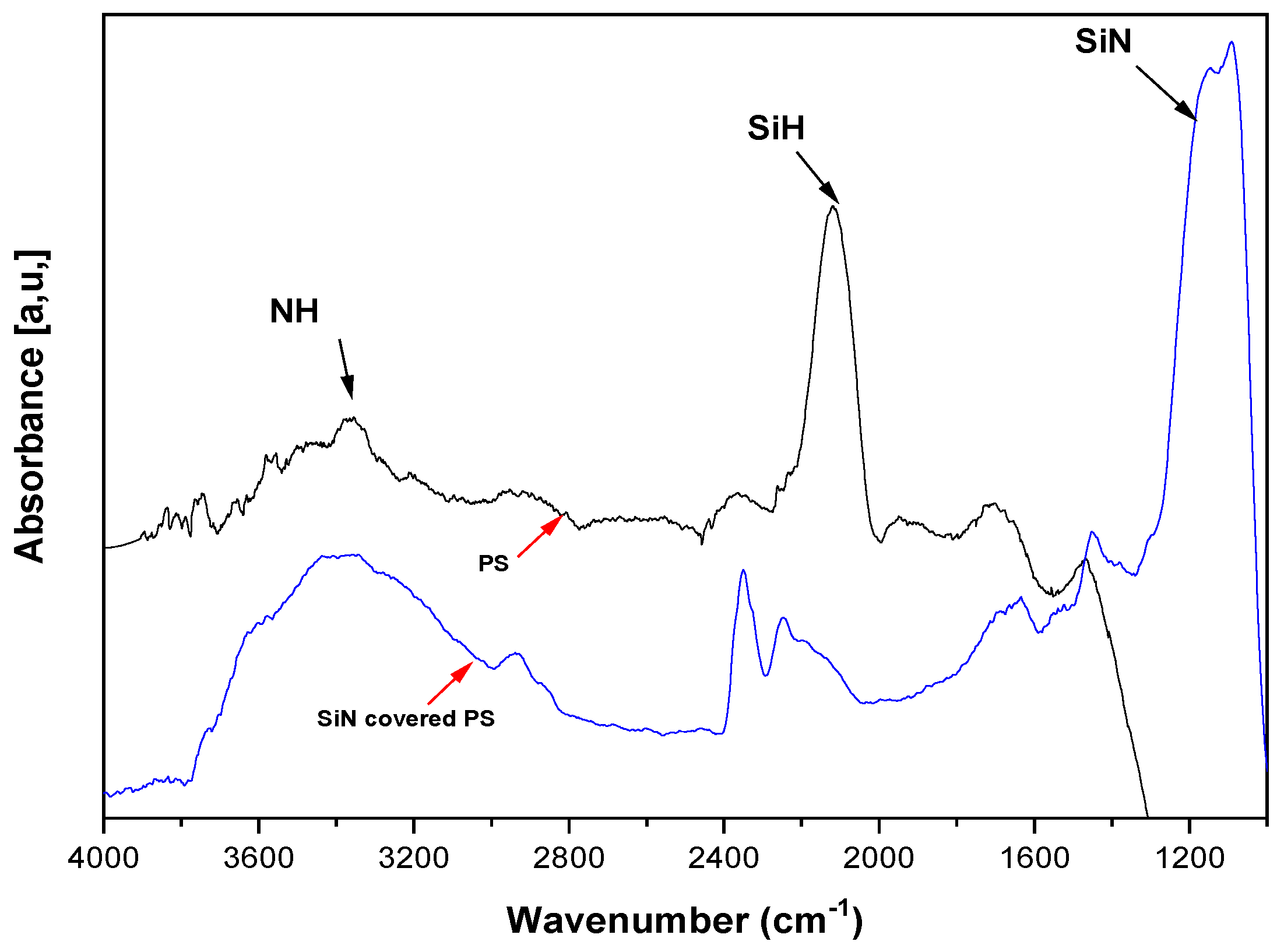

2. Materials and Methods

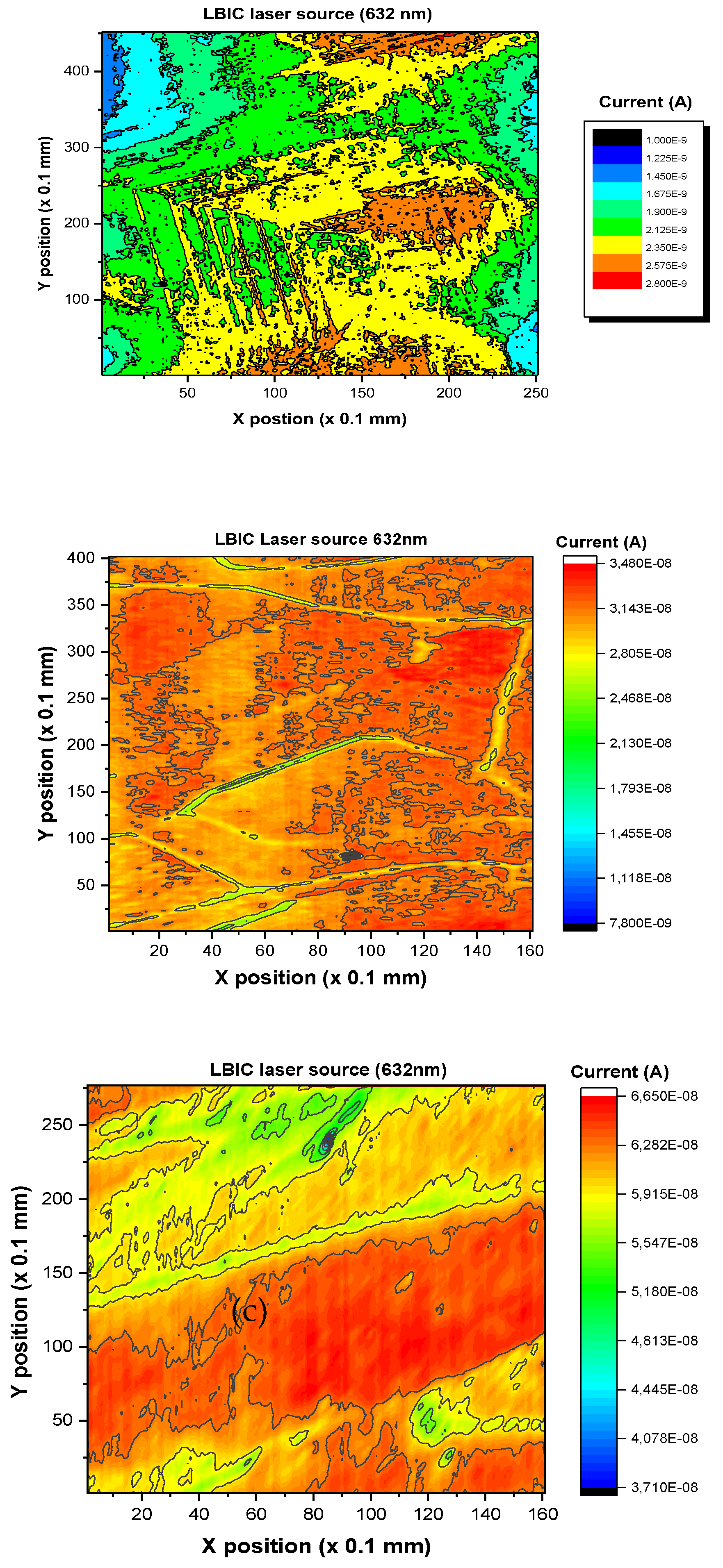

3. Results and discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Burtescu, S., Parvulescu, C., Babarada, F., Manea, E. The low cost multicrystalline silicon solar cells. Materials Science and Engineering: B 2009), 165(3), 190-193. [CrossRef]

- Lan, C. W., Hsu, C., & Nakajima, K. Multicrystalline silicon crystal growth for photovoltaic applications. In handbook of crystal growth 2015 pp. 373-411. Elsevier.

- Yu, W., Xue, Y., Mei, J., Zhou, X., Xiong, M., Zhang, S. Segregation and removal of transition metal impurities during the directional solidification refining of silicon with Al-Si solvent. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2019, 805, 198-204. [CrossRef]

- Lv, X., Li, H., Ding, D., Yu, X., Jin, C., & Yang, D. Interfacial characterization of non-metal precipitates at grain boundaries in cast multicrystalline silicon crystals. Journal of Crystal Growth 2025, 652, 128042. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., Liu, J., Li, Y., Wei, G., Li, Q., Fan, Z., He, D. Dislocations in Crystalline Silicon Solar Cells. Advanced Energy and Sustainability Research 2024, 5(2), 2300240.

- Alrasheedi, N. H. The Effects of Porous Silicon and Silicon Nitride Treatments on the Electronic Qualities of Multicrystalline Silicon for Solar Cell Applications. Silicon 2024, 16(4), 1765-1773. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R., Li, W., Ge, B., Song, J., Su, Q., Xi, M., & Liu, Y. Optimization of the deposited Al2O3 thin film process by RS-ALD and edge passivation applications for half-solar cells. Ceramics International 2024. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., Chen, B., Lee, W., Fukuzawa, M., Yamada, M., & Sekiguchi, T. Grain boundaries in multicrystalline si. Solid State Phenomena 2010, 156, 19-26.

- Woo, S., Bertoni, M., Choi, K., Nam, S., Castellanos, S., Powell, D. M., Choi, H. An insight into dislocation density reduction in multicrystalline silicon. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells 2016, 155, 88-100. [CrossRef]

- Jemai, A. B., Mannai, A., Khezami, L., Mokraoui, S., Algethami, F. K., Al-Ghyamah, A., Rabha, M. B. Aluminum nanoparticles passivation of multi-crystalline silicon nanostructure for solar cells applications. Silicon 2020, 12, 2755-2760. [CrossRef]

- Ayvazyan, G. Crystalline and Porous Silicon. In Black Silicon: Formation, Properties, and Application. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland 2024, pp. 1-49).

- Lipinski, M., Panek, P., Bełtowska, E., & Czternastek, H. Reduction of surface reflectivity by using double porous silicon layers. Materials Science and Engineering: B 2003, 101(1-3), 297-299. [CrossRef]

- Mogoda, A. S., & Farag, A. R. The effects of a few formation parameters on porous silicon production in HF/HNO3 using ag-assisted etching and a comparison with a stain etching method. Silicon 2022, 14(17), 11405-11415. [CrossRef]

- Rabha, M. B., Hajji, M., Mohamed, S. B., Hajjaji, A., Gaidi, M., Ezzaouia, H., Bessais, B. Stain-etched porous silicon nanostructures for multicrystalline silicon-based solar cells. The European Physical Journal-Applied Physics 2012, 57(2), 21301. [CrossRef]

- H Faltakh, R Bourguiga, MB Rabha, B Bessais. Superlattices and Microstructures 2012, 72: 283-295.

- M Ben Rabha, SB Mohamed, W Dimassi, M Gaidi, H Ezzaouia, B Bessais. physica status solidi c 2011, 8: 883-886.

- L Khezami, AO Al Megbel, AB Jemai, MB Rabha Applied Surface Science 2015, 353:106-111.

- Harbeke, G., Jastrzebski, L., J. Electrochem. Soc 1990, 137: 696–699.

- M. Ben Rabha, M. Salem, M.A. El Khakani, B. Bessais, M. Gaidi, Mater. Sci. Eng.B 2013, 178: 695–697.

- A. Cuevas, D. Mcdonald, Sol. Energy 2004, 76: 255–262.

- Lotfi Khezami, Abdelbasset Bessadok Jemai, Raed Alhathlool, Mohamed Ben Rabha Solar Energy 2016, 129:38-44.

- O. Porre ; S. Martinuzzi ; M. Pasquinelli ; I. Perichaud ; N. Gay.Published in: Conference Record of the Twenty Fifth IEEE Photovoltaic Specialists Conference 1996.

- F.A. Harraz, T. Sakka, Y.H. Ogata, Phys. Status Solidi (A) 2003, 197, 51-56.

- M. Rahmani, A. Moadhen, M.A. Zaibi, H. Elhouichet, M. Oueslati, J. Lumin 2008, 128,1763-1766.

- W.M. Arnoldbik, F.H.P.M. Habraken, Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 2007, 256-300.

- Y. Kanemitsu, S. Okamoto, Phys. Rev. B 1997, 56: 1696.

- T. Maruyama, S. Ohtani, Appl. Phys. Lett 1994, 65: 1346.

- Yoshihiko Kanemitsu, Toshiro Futagi, Takahiro Matsumoto, and Hidenori Mimura. Phys. Rev. B 1994,49: 14732.

- B. Stannowski, J. K. Rath, and R. E. I. Schropp, J. Appl. Phys 2003, 93, 2618.

- Lelièvre, J. F., Fourmond, E., Kaminski, A., Palais, O., Ballutaud, D., Lemiti, M. Study of the composition of hydrogenated silicon nitride SiNx: H for efficient surface and bulk passivation of silicon. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells 2009, 93(8), 1281-1289. [CrossRef]

- Dao, V. A., Heo, J., Kim, Y., Kim, K., Lakshminarayan, N.,Yi, J. Optimized surface passivation of n and p type silicon wafers using hydrogenated SiNx layers. Journal of non-crystalline solids 2010, 356, 2880-2883. [CrossRef]

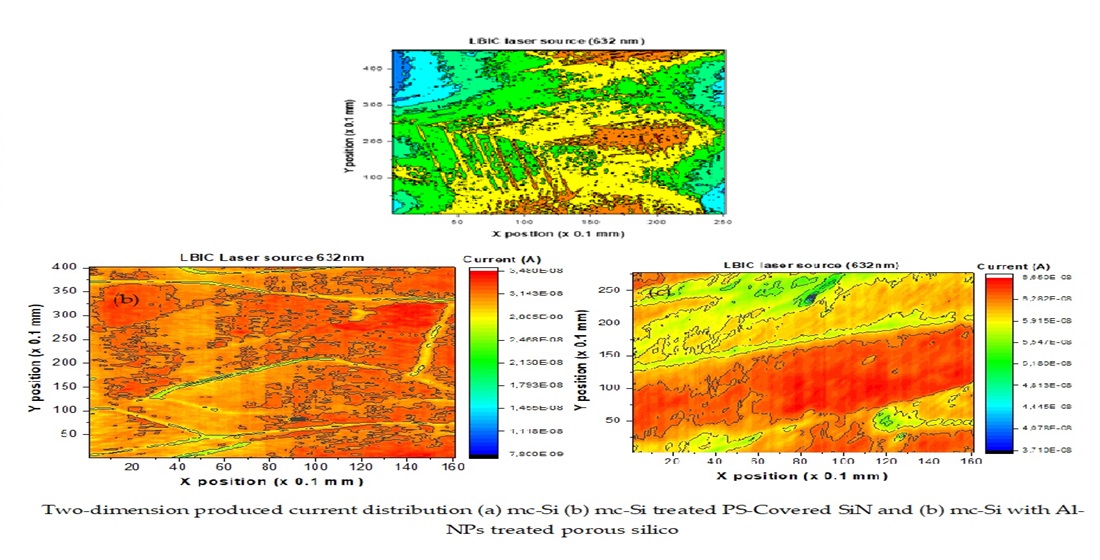

- Dimassi, W., Derbali, L., Bouaı¨cha, M., Bessaıs, B., Ezzaouia, H. Two-dimensional LBIC and Internal-Quantum-Efficiency investigations of grooved grain boundaries in multicrystalline silicon solar cells. Sol. Energy 2011, 85, 350–355.

- Ben Rabha, M., Dimassi, W., Bouaicha, M., Ezzaouia, H., Bessais, B. Laser-beam-induced current mapping evaluation of porous silicon-based passivation in polycrystalline silicon solar cells. Sol. Energy 2009, 83, 721. [CrossRef]

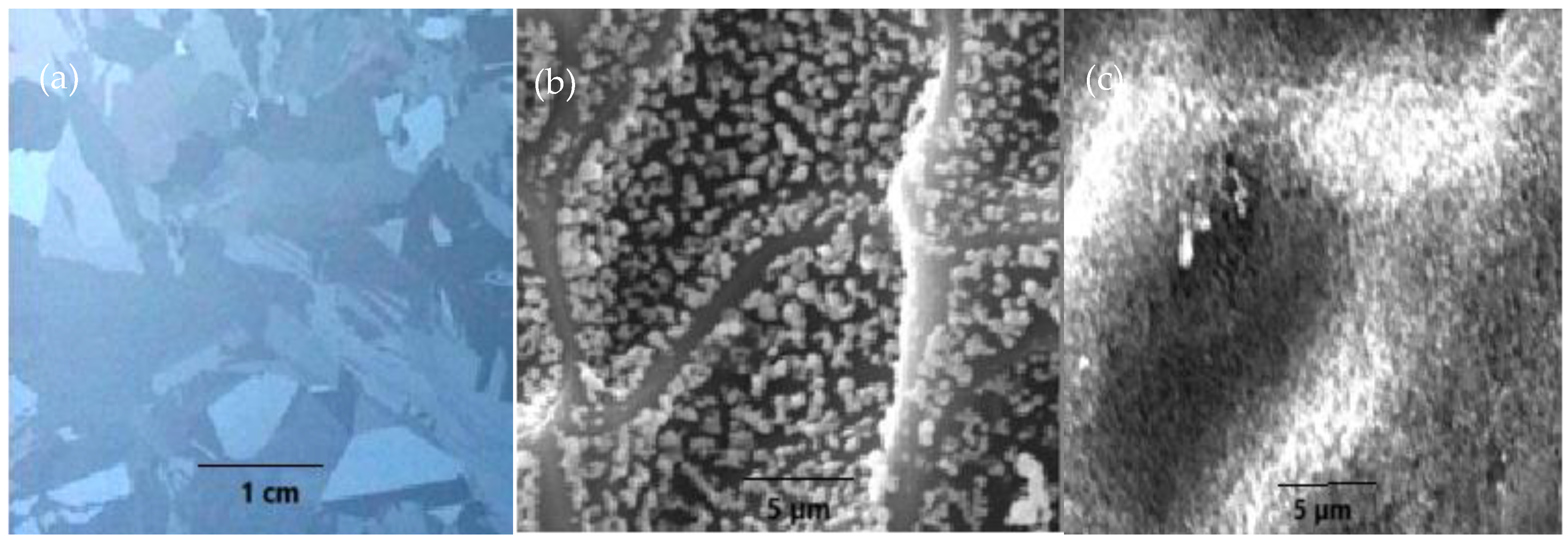

- Achref, M., Khezami, L., Mokraoui, S., Rabha, M. B. Effective surface passivation on multi-crystalline silicon using aluminum/porous silicon nanostructures. Surfaces and Interfaces 2020, 18, 100391. [CrossRef]

- Krotkus, A., Grigoras, K., Pacebutas, V., Barsony, I., Vazsonyi, E., Fried, M., Szlafcik, J., Nijs, J., Levy-Clement, C., 1997. Efficiency improvement by porous silicon coating of multicrystalline solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 45, 267. [CrossRef]

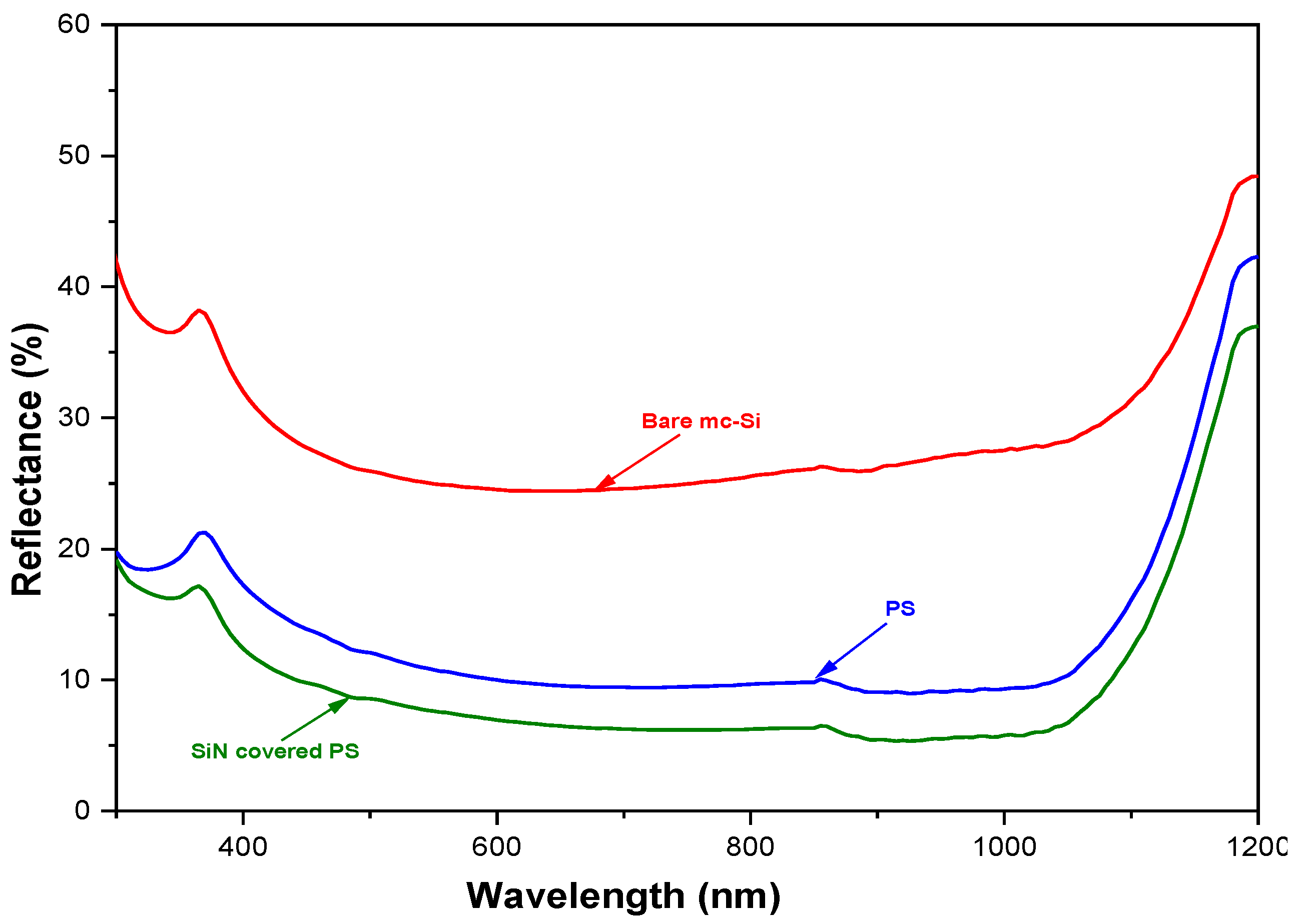

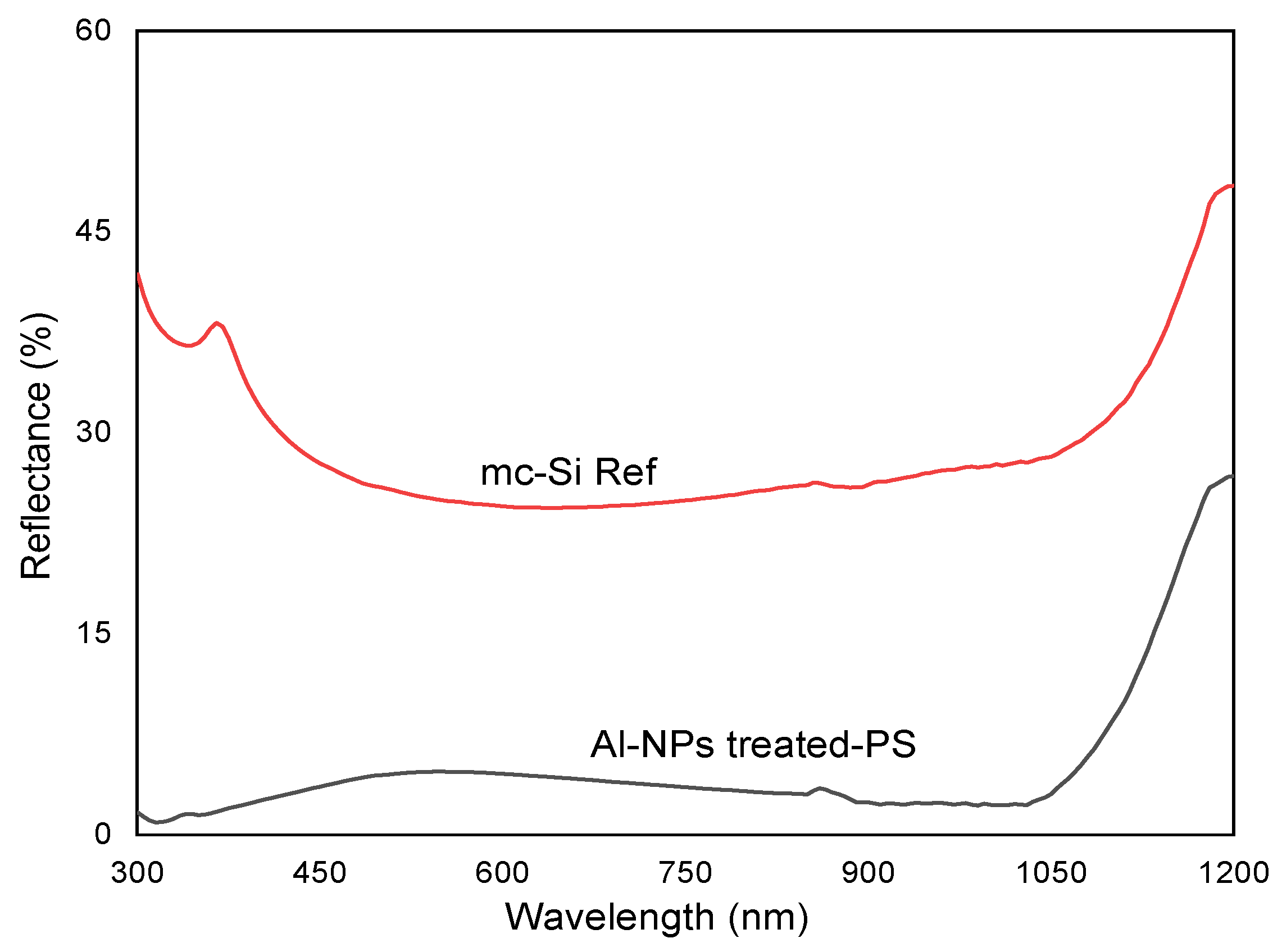

| Reflectivity (%) | Diffusion length (µm) | Generated current (nA) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ref mc-Si | 30 | 2 | 1-2.8 |

| Sample 1 | 10 | 100 | 7.8-34 |

| Sample 2 | 5 | 300 | 37-66 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).