2. Preliminaries

This paper integrates critical insights from multiple fields, including graph classes, linear algebra, graph theory, algorithms, and linear programming, each contributing indispensable tools and perspectives that enhance both the formulation and depth of our analysis. This section presents the fundamental concepts most pertinent to understanding the study’s objectives and methodology. For definitions, notations, additional concepts, or more comprehensive details not covered in this section, standard textbooks and monographs—such as

Introduction to Algorithms [

44],

Theory of Linear and Integer Programming [

45],

Graph Theory [

46],

Introduction to Linear Algebra [

47], and

Graph Class: A Survey [

18]—are recommended as supplementary resources.

2.1. Graphs and Their Representations

Each graph in this paper is finite, undirected, and contains no multiple edges or self-loops, where V is the vertex set and E is the edge set of G. If the vertex and edge sets are not explicitly specified, they are denoted by and , respectively.

Two vertices u and v in a graph G are adjacent if they are connected with an edge, i.e., , and are also called neighbors. The degree of a vertex v in G, denoted by , is the number of neighbors of v. For any vertex , the neighborhood of v in G, denoted by , is the set of neighbors of v, so that . A vertex u is a closed neighbor of v if either or . The closed neighborhood of v, denoted by , is the set of closed neighbors of v.

Let and be two graphs. If and , then is a subgraph of G. If is a subraph of G, and contains all the edge with , then is an induced subgraph; we say that is induced by and written as .

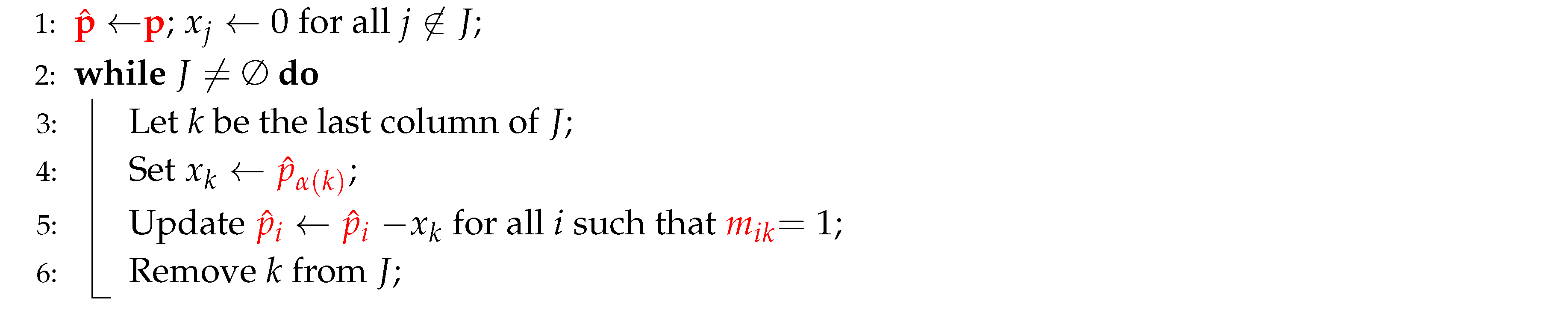

Graphs in this paper are represented using

adjacency lists. The

adjacency-list representation of a graph

consists of an array of

lists. Each vertex

is associated with a list of all neighbors of

v.

Figure 1 provides an example of the adjacency-list representation for a graph

G with 4 vertices and 4 edges.

This representation is efficient in terms of memory usage. The amount of memory required to store a graph in this representation is , where n and m represent the number of vertices and edges, respectively. Adjacency lists support efficient operations such as

Neighbor Access: Accessing all (closed) neighbors of a vertex v takes time, as they are directly stored in a list. With each vertex maintaining its own neighbor list, this structure enables quick access to both neighbors and closed neighbors.

Traversal: Traversing all vertices and edges in the graph takes time. This efficiency is particularly advantageous in algorithms like Depth-First Search (DFS) and Breadth-First Search (BFS).

2.2. -Domination and Total -Domination in Weighted Graphs

A dominating set D of a graph is a subset of V such that for every , while a total dominating set D is a subset of V such that for every . The domination number of G, denoted by , is the minimum cardinality of a dominating set of G. The total domination number of G, denoted by , is the minimum cardinality of a total dominating set of G. The domination problem is to find a dominating set of G with the minimum cardinality, and the total domination problem is to find a total dominating set of G with the minimum cardinality.

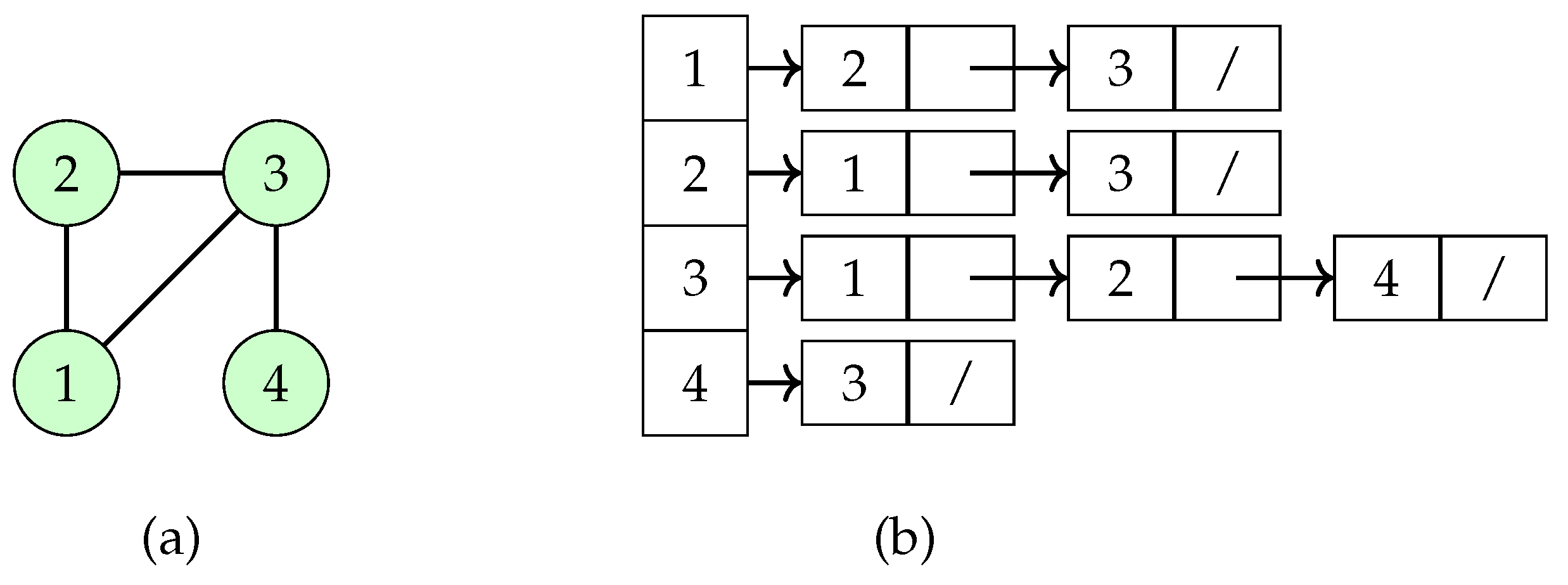

Figure 2 illustrates a dominating set

and a total dominating set

for the same graph. Let

G denote the graph in this figure. While

also qualifies as a dominating set of

G,

does not qualify as a total dominating set, since

is empty for

.

Domination and total domination can be expressed in terms of functions. Let be a labeling function of a graph . The function f is a dominating (respectively, total dominating) function of G if (respectively, ) for every . The labeling weight of f is defined as .

Table 1 presents a dominating function

f and a total dominating function

g for the graph shown in

Figure 2. The function

f is associated with the set

and

g with the set

. Both functions have a labeling weight of 2, equal to

and

, respectively.

Clearly, the domination number

is the minimum labeling weight of a dominating function, i.e.,

Similarly, the total domination number

is the minimum labeling weight of a total dominating function, i.e.,

Definition 1. Let k be a fixed positive integer, and let be a labeling function of a graph . The function f is a -dominating (respectively, total -dominating) function of G if (respectively, ) for every . The labeling weight of f is defined as . The -domination problem is to find a -dominating function of G with the minimum labeling weight, while the total -domination problem is to find a total -dominating function of G with the minimum labeling weight.

By Definition 1, domination and total domination correspond to -domination and total -domination, respectively.

Let

G be the graph shown in

Figure 2.

Table 2 provides the values of a function

f for each vertex in

G and checks whether the

-domination condition is satisfied. This verification confirms that

f is a valid

-dominating function for

G.

We now introduce the concepts of -domination and total -domination for weighted graphs. As mentioned earlier in the introduction, this paper focuses exclusively on vertex-weighted graphs.

Definition 2. Let be a function that assigns a weight to each vertex v of a graph . We refer to w as a vertex-weight function, and as a weighted graph.

Definition 3. Let k be a fixed positive integer. The labeling weight of a -dominating function or a total -dominating function f of a weighted graph is defined as . The -domination problem for a weighted graph is to find a -dominating function of G with the minimum labeling weight, while the total -domination problem is to find a total -dominating function with the minimum labeling weight.

An unweighted graph H can be treated as a specific case of a weighted graph, where every vertex has a weight . The primary difference in defining the -domination problem for unweighted and weighted graphs lies in the calculation of the labeling weight.

In unweighted graphs, the labeling weight of a -dominating function is simply the sum of the function values assigned to each vertex, i.e., , where each vertex has an implicit weight of 1.

In weighted graphs, each vertex is assigned a specific weight through a vertex-weight function. The labeling weight is then calculated as , meaning that the contribution of each vertex to the total weight depends on both the value of the labeling function and the vertex’s weight .

Table 3 presents the values of a

-dominating function

f and vertex weights

w for the graph

shown in

Figure 2. The table indicates that the labeling weight of

f for the unweighted graph

G is 4, based on

, and the labeling weight for the weighted graph

is 12, calculated as

.

This distinction also applies to the definitions of total -domination on unweighted and weighted graphs. Therefore, the introduction of vertex weights in weighted graphs alters how the overall labeling weight is determined in both the -domination and total -domination problems.

2.3. k-Tuple Domination and Total k-Tuple Domination in Weighted Graphs

Let k be a fixed positive integer, and let be a labeling function for a graph . The function f is a k-tuple dominating function of G if for every . Similarly, f is a total k-tuple dominating function if for every . The labeling weight of f is defined as .

The k-tuple domination problem aims to find a k-tuple dominating function of G with the minimum labeling weight. Similarly, the total k-tuple domination problem seeks a total k-tuple dominating function with the minimum labeling weight.

Domination and total domination correspond to 1-tuple domination and total 1-tuple domination, respectively.

Definition 4. Let k be a fixed positive integer. The labeling weight of a k-tuple dominating function or a total k-tuple dominating function f of a weighted graph is defined as . The k-tuple domination problem for a weighted graph is to find a k-tuple dominating function with the minimum labeling weight. Similarly, the total k-tuple domination problem is to find a total k-tuple dominating function with the minimum labeling weight.

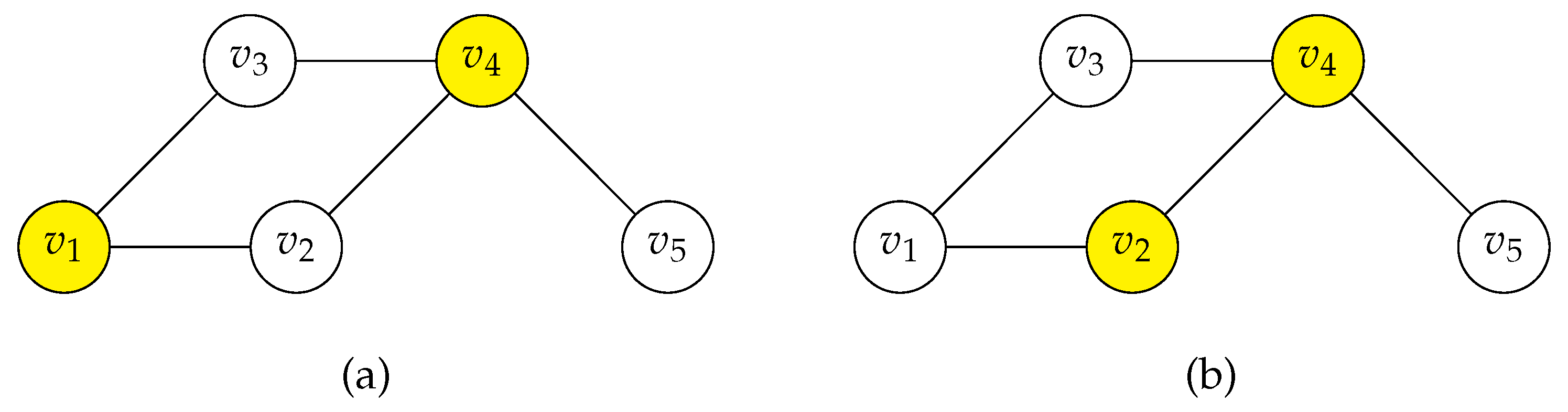

Figure 3 illustrates a graph

with six vertices.

Table 4 provides the labeling weights for a 2-tuple dominating function

f and a total 2-tuple dominating function

g for both the unweighted graph

G and the weighted graph

.

The function f assigns values as shown in the table, satisfying the 2-tuple domination condition for each vertex. For instance, vertex is dominated because . The labeling weights differ for the unweighted and weighted versions due to the vertex weights .

Interestingly , g is also a 2-tuple dominating function of G. However, for the weighted graph , the labeling weight of g is smaller than that of f, demonstrating that g is more efficient in terms of weight minimization.

2.4. Strongly Chordal Graphs and Chordal Bipartite Graphs

A

chord in a cycle of a graph is an edge that connects two non-consecutive vertices in the cycle. A

chordal graph is a graph in which every cycle with four or more vertices has a chord. A

perfect elimination ordering of a graph

is an ordering

of the vertices such that for any indices

, if

and

, then

. Rose [

48] proved that a graph is chordal if and only if it admits a perfect elimination ordering.

A chord

in a cycle

C with vertices ordered as

is called an

odd chord if

is odd. A graph

G is a

strongly chordal graph if it is chordal, and every cycle of

vertices in

G, where

, contains an odd chord.

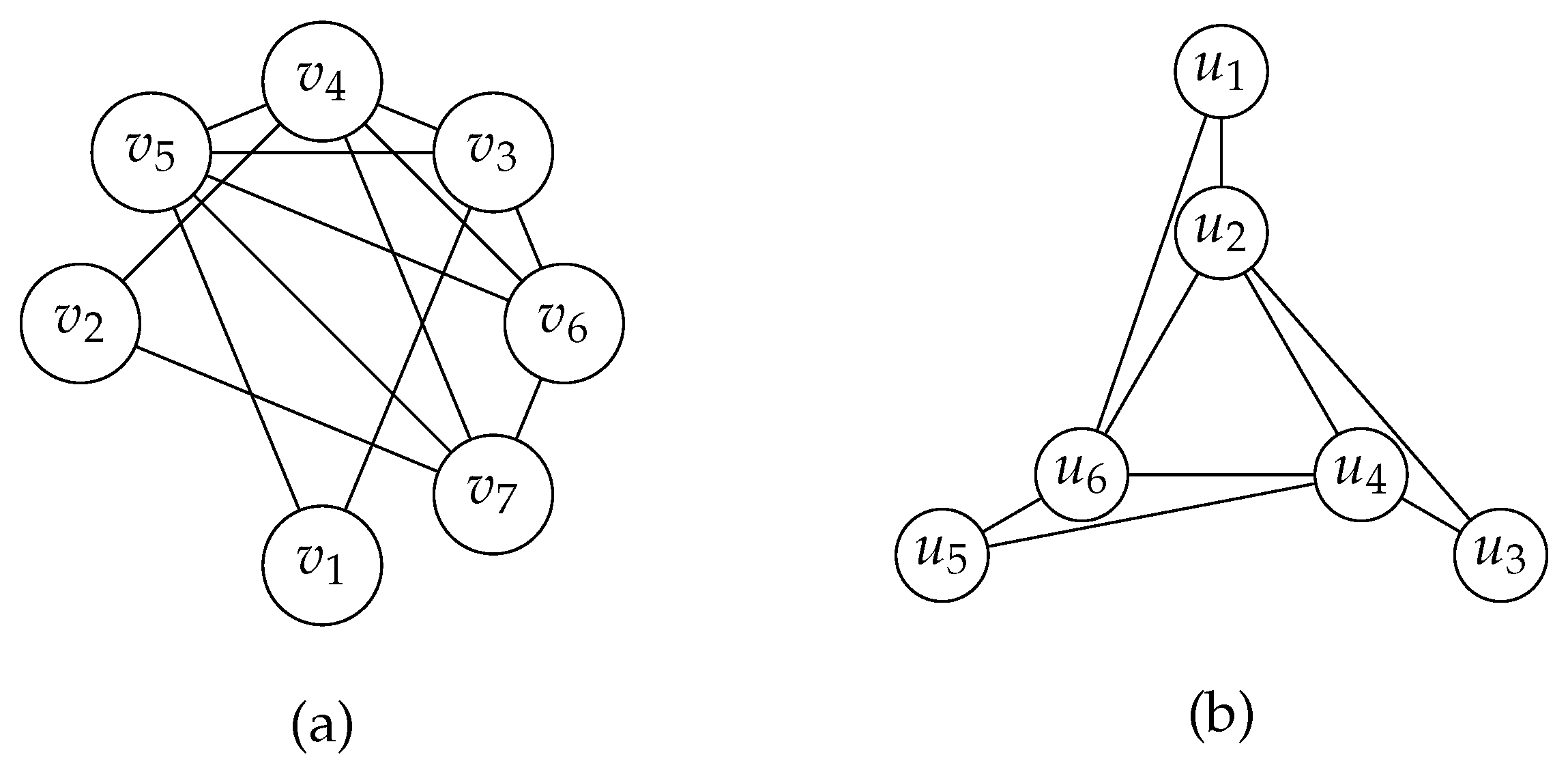

Figure 4 demonstrates a strongly chordal graph and the

Hajós graph. The Hajós graph is chordal but not strongly chordal since the cycle

contains no odd chords.

A

strong elimination ordering of a graph

is a perfect elimination ordering such that for each

and

, if

,

, and

, then

. Farber [

49] proved that a graph is strongly chordal if and only if it admits a strong elimination ordering.

Figure 4 shows a strongly chordal graph with a strong elimination ordering

.

A

bipartite graph is a graph

in which the vertex set

can be partitioned into two disjoint sets

X and

Y such that every edge in the graph connects a vertex in

X to a vertex in

Y, and no edge connects two vertices within the same set. In other words, there are no edges between vertices within

X or within

Y. Therefore, a bipartite graph does not have a cycle of an odd number of vertices.

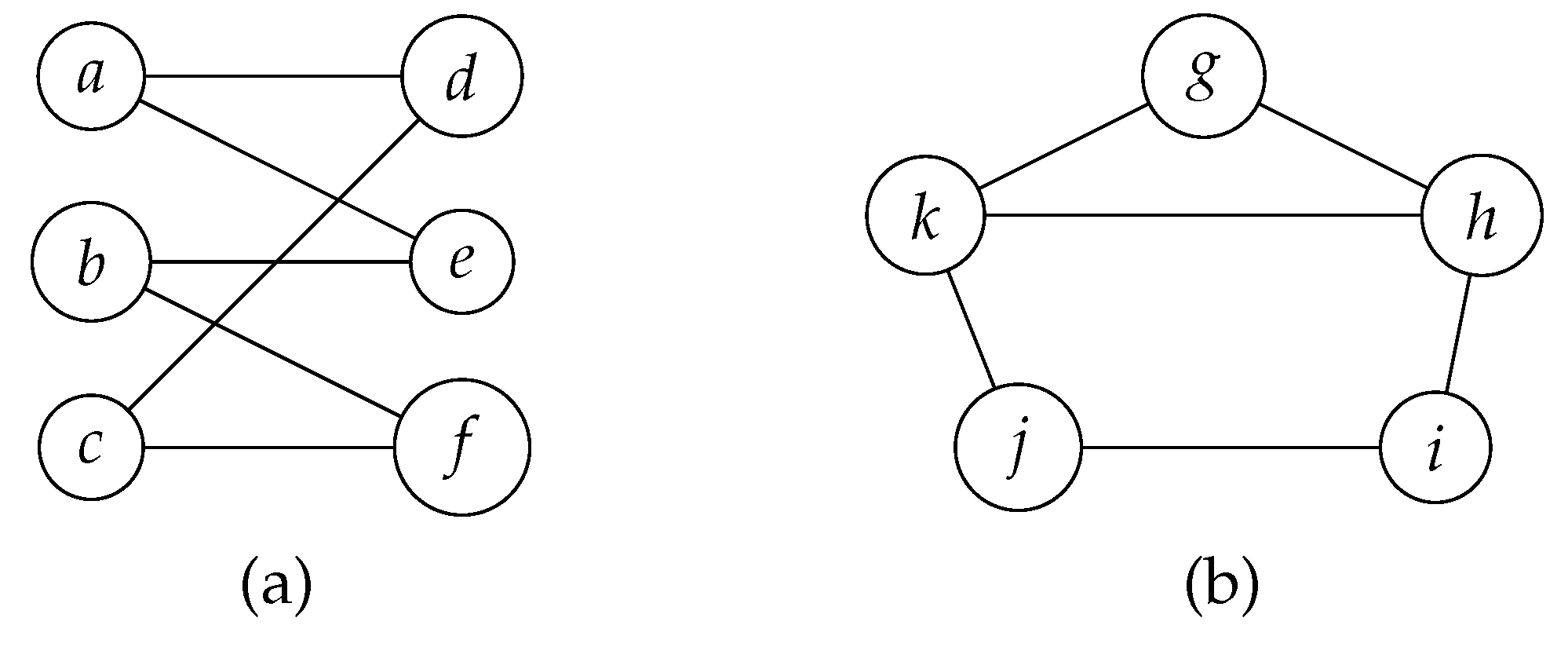

Figure 5 shows two graphs: The left one is bipartite, while the right one contains a cycle of three vertices and is therefore not bipartite.

A

chordal bipartite graph is a bipartite graph in which every cycle of more than four vertices contains a chord.

Figure 6 shows two bipartite graphs: The left one is chordal bipartite, while the right one is not.

Let be a graph, and let be an ordering of V. Let be a subgraph of G induced by . A weak elimination ordering of G is an ordering such that for any indices , if , then .

Uehara [

50] showed that a graph is chordal bipartite if and only if it admits a weak elimination ordering. The ordering

is a weak elimination ordering of the chordal bipartite graph in

Figure 6(a).

2.5. Proper Interval Graphs and Convex Bipartite Graphs

A graph

is an

interval graph if there exits an

interval model on the real line such that each closed interval

in the interval model corresponds to a vertex

, and two vertices

are adjacent in

G if and only if their corresponding intervals overlap, that is:

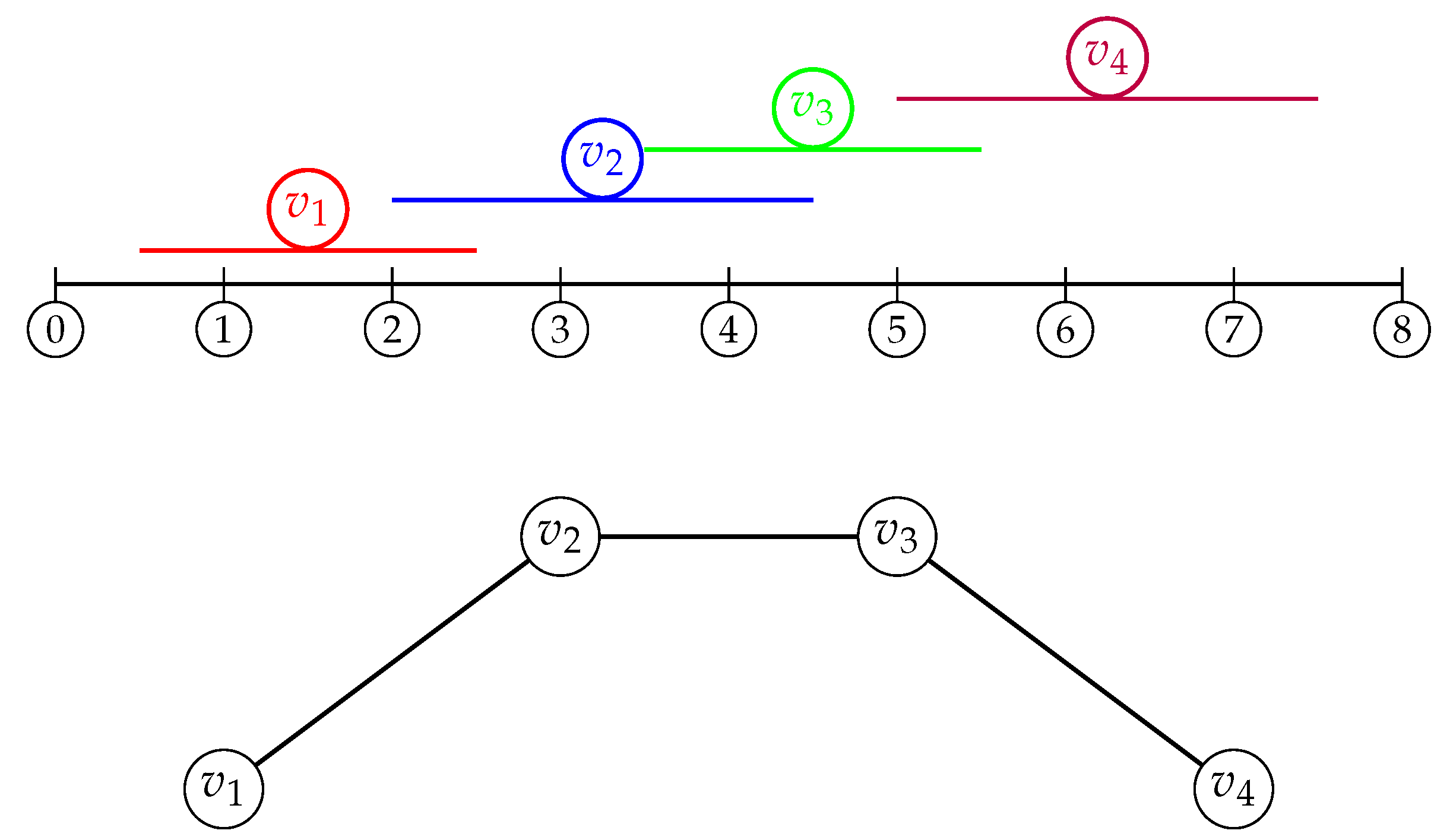

Figure 7 illustrates an interval graph

, which is constructed from an interval model on the real line. The top part of the figure represents the intervals

,

,

, and

, labeled as vertices

and

, respectively. An edge exists between two vertices if their corresponding intervals overlap. For example, the intervals

and

overlap, resulting in an edge between

and

in the graph. Similarly,

and

share an edge due to the overlap of their intervals, as do

and

.

The lower part of the figure depicts the corresponding graph structure. The vertices and are connected by edges according to their interval overlaps, forming a path graph. .

An interval graph is called a

proper interval graph if there exists an interval model for this interval graph such that for every pair of intervals

and

in the model, neither interval is strictly contained within the other, i.e., it is not true that

and

. A

unit interval graph is a special type of interval graph where all the intervals associated with the vertices have the same length. Actually, a unit interval graph

G if and only if

G is a proper interval graph [

18]. They form the same class of graphs.

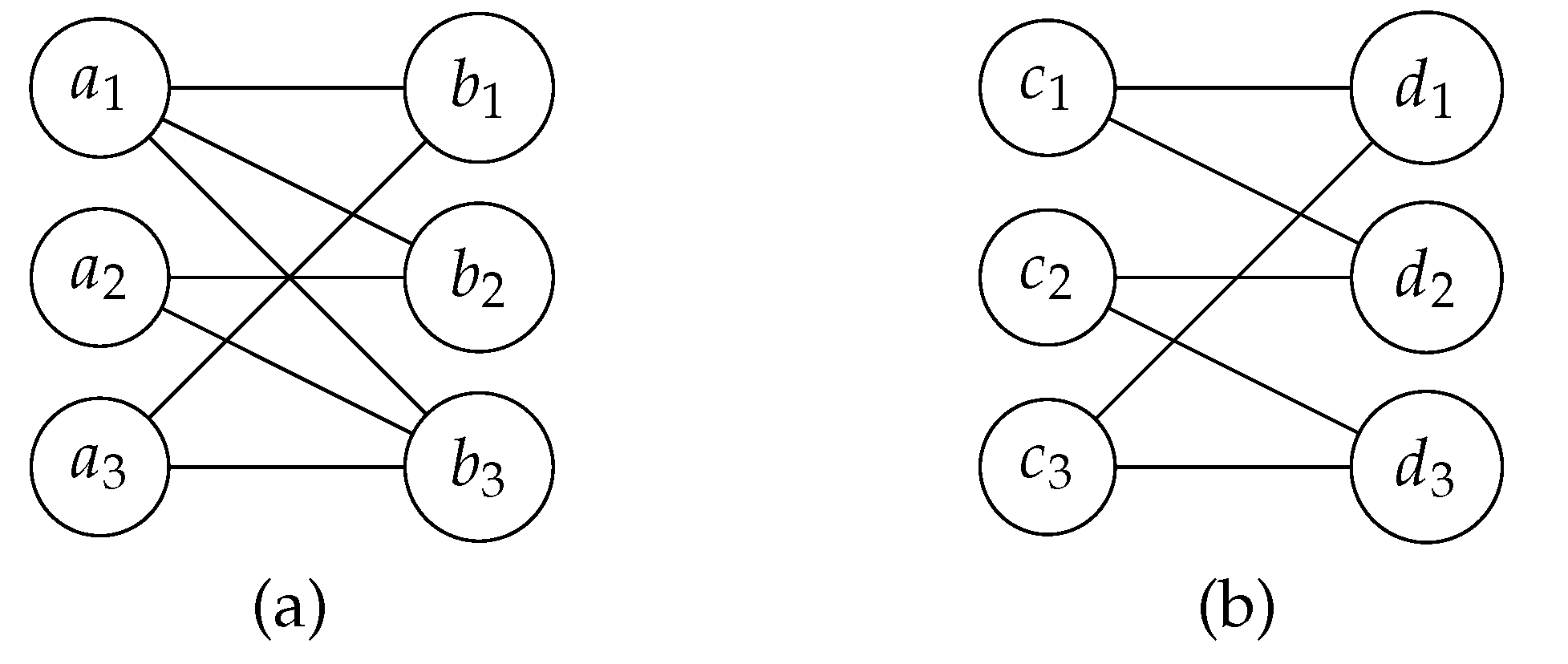

Let be a bipartite graph. An ordering P of X in B has the adjacency property if for each vertex , consists of vertices that are consecutive in the ordering P of X. A bipartite graph is a convex bipartite graph if there is an ordering of X or Y satisfying the adjacency property.

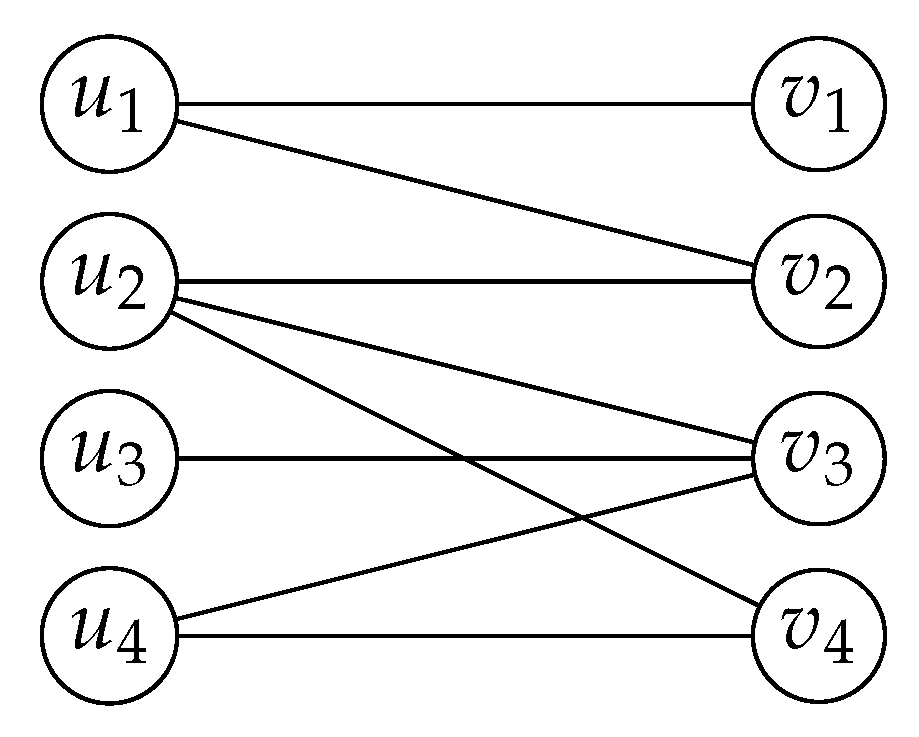

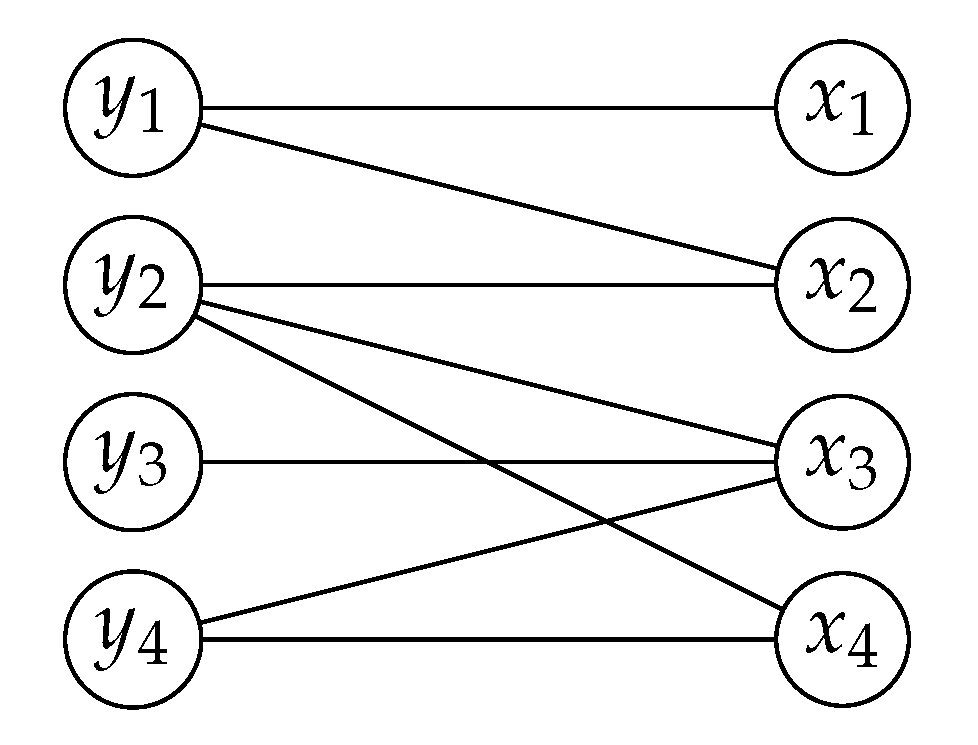

The convex bipartite graph illustrated in

Figure 8 consists of two disjoint sets of vertices,

and

. The graph satisfies the adjacency property: for every vertex in

U, the vertices of its neighbors in

V are consecutive in the ordering. For instance, the neighbors of

are

and

are consective in the ordering. Similarly,

is adjacent to consecutive vertices

,

, and

. This property is consistent for all vertices in

U.

2.6. Matrices and Vectors

A matrix is a rectangular array of numbers arranged in rows and columns. The horizontal arrangement of entries forms the rows, and the vertical arrangement forms the columns. An matrix is a matrix with m rows and n columns. The individual numbers within the matrix are called entries. The entry in the i-th row and j-th column is called the -entry.

Matrices are typically written within square brackets or parentheses; in this paper, they are written within parentheses. For example, a

matrix is written as

Let

represent the entry in the

i-th row and

j-th column of an

matrix

. The

matrix

can be denoted by

and represented as follows:

where

represents the set of all matrices with

m rows and

n columns whose entries are real numbers. Formally, this is defined as

For any matrices and in , we define the entrywise inequality to mean that for all and . For any scalar , we write to indicate that every entry of is at least k. These definitions extend naturally to other similar cases involving entrywise comparisons. If each entry of is k, then is called a k-matrix.

Let

. The

transpose of

A, denoted by

, is an

matrix defined by

. For a matrix

which is a

matrix, its transpose

is

which is a

matrix.

A submatrix of a matrix is obtained by removing any number of rows or columns from , including the possibility of removing none. Consequently, is a submatrix of itself when no rows or columns are removed.

A

block of matrix

is a submatrix formed by rows

and columns

. It is represented as:

where

and

. The following matrix

consists of four blocks

,

,

, and

:

A

square matrix is a matrix with the same number of rows and columns. The

identity matrix is a square matrix

such that an entry of

is 1 if its row index and column index are equal; otherwise,

. For example, the

identity matrix looks like this:

A

row vector and a

column vector are two types of vectors that differ in their orientation within a matrix or vector space. A row vector is a

matrix represented as

where

are the vector elements. A column vector is an

matrix represented as

where

are the vector elements. Clearly, the transpose operation converts a row vector into a column vector and vice versa.

To ensure clarity and avoid ambiguity in notation, we adopt the following conventions: Vectors are represented by boldface upright lowercase letters, such as , , or . For example, denotes a column vector with n entries. Matrices are represented by boldface upright uppercase letters, such as , , or , and entries of a matrix are denoted by for the entry in the i-th row and j-th column. Scalars, by contrast, are represented by italicized lowercase letters, such as a, b, or c.

In general, when we refer to as a vector, we mean that it is a column vector by default. If a row vector is intended, this will be explicitly indicated. If each entry of a vector is a constant k, the vector is called a k-vector.

2.7. Totally Balanced, Totally Unimodular, and Greedy Matrices

A matrix is called a -matrix if every entry in is either 1 or 0. In a matrix of numbers, the sum of all entries in a row is called the row sum, while the sum of all entries in a column is called the column sum. A -matrix is said to be totally balanced if it does not contain any square submatrix satisfying all the following “forbidden conditions”:

All row sums are equal to 2.

All column sums are equal to 2.

All columns are distinct.

Here is an example of a matrix that is

not totally balanced:

To see why

is not totally balanced, consider the the submatrix

obtained by removing the 4th and 5th rows and columns:

In

, (1) all row sums are equal to 2, (2) all column sums are equal to 2, and (3) all columns are distinct. This submatrix satisfies the forbidden conditions, so

is not totally balanced. In contrast, the following matrix

is an example of a totally balanced matrix:

A

-matrix is

greedy if it does not contain any of the following forbidden submatrices:

A greedy matrix is in

standard greedy form [

19] if it does not contain the following

-matrix as a submatrix:

The matrix

below is a greedy matrix in standard greedy form. However, the matrix

is a greedy matrix that is

not in standard greedy form. This is because the submatrix of

formed by deleting rows 3 and 4 and columns 3 and 4 is identical to the

-matrix.

Let denote the determinant of a matrix . The matrix M is totally unimodular if for every square submatrix of .

Consider the matrices

and

:

The matrices and illustrate examples of a totally unimodular matrix and a matrix that is not totally unimodular, respectively. Matrix is totally unimodular because the determinant of every square submatrix of is in . In contrast, matrix is not totally unimodular. For example, is 2. Thus, fails to satisfy the defining condition of total unimodularity. This comparison underscores the stringent conditions a matrix must satisfy to be classified as totally unimodular.

Furthermore, a matrix has the consecutive ones property if its rows can be permuted in such a way that, in every column, all the 1s appear consecutively. This property is particularly relevant in applications involving binary matrices and is a useful tool for analyzing matrix structures.

The following theorem reveals a connection between the consecutive ones property and total unimodularity.

Theorem 1 ([

45]).

If a -matrix has the consecutive ones property for columns, then it is totally unimodular.

2.8. Linear and Integer Linear Programming

Linear programs are optimization problems that maximize or minimize a linear objective function, subject to linear constraints. A minimization linear program seeks to minimize the objective function, while a maximization linear program aims to maximize it.

Linear programming is the field of study and methodology focused on formulating, analyzing, and solving linear programs. It encompasses the theories, algorithms, and techniques developed for solving linear programs. In essence, linear programming refers to the process and theory, while a linear program is an individual problem instance.

Formulating a minimize linear program requires the following inputs:

n real numbers

(coefficients of the objective function),

m real numbers

(resource limits), and

coefficients

for

and

(constraint coefficients). The goal is to find values for the decision variables

that minimize the objective function, subject to all constraints. This formulation is given by:

In this formulation, the expression in (

1) is the

objective function; the variables

,

are called

decision variables; and the inequalities in () and () together form the

constraints. Specifically, the

n inequalities in () are

nonnegativity constraints, requiring each

to be nonnegative.

In mathematical optimization, duality provides two perspectives on an optimization problem: the primal problem and its corresponding dual. When the primal is a minimization problem, its dual is a maximization problem, and conversely, when the primal is a maximization problem, the dual will be a minimization problem. Thus, for a pair of primal and dual problems, one is a maximization problem, and the other is a minimization problem.

Weak duality states that, for any feasible solutions to a pair of primal and dual problems, the value of the maximization problem is always less than or equal to the value of the minimization problem. Strong duality further asserts that, at optimality, the optimal value of the primal problem is equal to the optimal value of its dual.

For any linear program considered as the

primal, there exists a corresponding

dual linear program. Each constraint in the primal corresponds to a variable in the dual, and each decision variable in the primal corresponds to a constraint in the dual. The dual of the minimization linear program in equations

1– is formulated as follows:

In this dual problem, are the dual variables associated with each primal constraint; are the coefficients of the dual objective function; and constraints in the dual correspond to the primal variables, and values become the bounds in the dual constraints.

For a minimization linear problem, the primal can be written in matrix form as

where

,

,

, and

. Its dual can be expressed as

where,

;

,

, and

are as defined in the primal formulation.

In many cases, capturing the essence of a linear program is best achieved without excessive notation or detail. To highlight the fundamental structure clearly and concisely, we adopt forms such as

to facilitate analysis, communication, and efficient solution of linear programs.

A solution to an optimization problem is a column vector , often called a point because each solution corresponds to a specific set of values for the variables, which can be represented as a single point in geometric space. In other words, each feasible solution is associated with a unique location in this space. A solution that satisfies all constraints is known as a feasible solution, whereas a solution that fails to satisfy at least one constraint is an infeasible solution. The set of points that satisfy all the constraints is referred to as the feasible region. In linear programming, the feasible region is called a polyhedron, as it is the intersection of linear constraints. A polyhedron is often denoted by P, such as , representing the set of all points that meet the specified constraints.

In an optimization problem, a constraint is called active at a given solution point if the solution causes the constraint to hold as an equality, effectively “binding” the solution at the boundary defined by the constraint. An extreme point of a polyhedron occurs where several of the constraints in the problem are active, often as many as the dimension of the space.

The

fundamental theorem of linear programming ([

51]) states that if a linear program has an optimal solution, at least one optimal solution will be located at an extreme point of the polyhedron. This result is foundational because it allows optimization algorithms like the simplex method to focus on the extreme points of the feasible region, significantly reducing the computational effort required to find an optimal solution. If every extreme point of a polyhedron consists of integer values for all variables, then the polyhedron is said to be

integral.

Theorem 2 establishes that linear programs satisfy strong duality.

An

integer linear program is an optimization model similar to a linear program but includes an additional constraint that requires all decision variables to be integers. This distinction substantially impacts both the complexity and solution methods for these problems. While linear programs can be solved in polynomial time [

52], integer linear programs are NP-complete [

53], making them more computationally challenging.

Integer linear programs satisfy weak duality but do not always satisfy strong duality, meaning the optimal values of an integer linear program and its dual may differ.

To solve integer linear programs, advanced methods such as branch-and-bound, branch-and-cut, and cutting planes are often employed. These methods frequently use linear relaxations, which remove the integer constraints to produce a continuous solution, providing useful bounds on the solution to an integer linear program. In certain cases, the optimal objective value of an integer linear program matches that of its linear relaxation, as illustrated by Theorem 3.

Theorem 3 ([

54]).

If , , and all have integer entries, with at least one of or as a constant vector, and is totally balanced, then the optimal objective values of the integer program

and its linear relaxation are the same.

3. -Domination in Weighted Strongly Chordal Graphs

In this section, we demonstrate that the -domination problem in weighted strongly chordal graphs with n vertices and m edges can be solved in time. The solution follows a four-step framework, as outlined below:

- (1)

Modeling (Section 3.1): The

-domination problem is formulated as an integer linear programming task using matrix representations, particularly adjacency matrices. This formulation establishes the theoretical foundation for the algorithmic approaches described in subsequent sections. We aim to solve the integer linear program by its relaxation.

- (2)

-

Primal and Dual Algorithms by Hoffman et al. (Section 3.2): We introduce the primal and dual algorithms proposed by Hoffman et al. [

19], which solve the linear program:

These algorithms provide a robust framework for solving linear programming problems, forming the basis for adapting solutions to the -domination problem.

- (3)

Refined Algorithms for Weighted Strongly Chordal Graphs (Section 3.3): Building on Hoffman et al.’s algorithms, this section introduces refinements tailored to the structural properties of weighted strongly chordal graphs. These refinements reduce the computational complexity to

, representing an intermediate step toward the final optimized solution.

- (4)

Optimized Algorithms with Enhanced Data Structures (Section 3.4): By integrating advanced data structures, this section further reduces the overall time complexity from

to

. This optimization capitalizes on the sparsity and adjacency structure of strongly chordal graphs, achieving linear-time performance relative to the graph’s size.

3.1. Modeling

We start by presenting Lemma 1 to concentrate exclusively on non-negative vertex weights (). This simplification allows us to assume that all weighted graphs have non-negative vertex weights.

Lemma 1. Let w be a vertex-weight function of a graph , and let represent the the minimum labeling weight of a -dominating function for . Define and let be a vertex-weight function such that for each . Then, .

Proof. Let

f be a

-dominating function for

with minimum weight, so

. Define a function

such that

for

and

for

. Since

is also a

-dominating function of

G and

for

, we obtain

Conversely, let

h be a

-dominating function for

with the minimum labeling weight, so

Define

f such that

for

and

for

. Clearly,

f is a

-dominating function of

G, and

for

. We have

This completes the proof. □

Let

be a weighted graph with

. We associate a variable

with each

and require that

for

. Let

for

. The

-domination problem for the weighted graph

G is formulated as the following integer linear program

:

Lemma 2. Let be an optimal solution to . Then, for all .

Proof. Clearly, is the minimized and for . Assume that there exists an in such that . For any constraint involving , the constraint remains satisfied if is replaced with k. Consequently, the resulting objective value is less than , leading to a contradiction. Therefore, the lemma holds. □

By Lemma 2, we can reformulate

as follows:

In graph theory, the neighborhood matrix and the closed neighborhood matrix are two distinct representations of the adjacency relationships in a graph H with vertices .

The neighborhood matrix of G is a matrix such that if ; otherwise, .

The closed neighborhood matrix of G is a matrix such that if ; otherwise, .

Let be the closed neighborhood matrix of the weighted graph G with , , and , where for .

We present the linear program

and its dual

using the closed neighborhood matrix

.

Let and denote the optimal objective values of an integer linear program and its linear relaxation , respectively. The polyhedron for is a subset of the polyhedron for , since includes the additional constraint that variables must be integers. Therefore, the optimal value of , minimized over a larger polyhedron, cannot be greater the optimal value of . Hence, .

In subsequent sections, we aim to demonstrate that for weighted strongly chordal graphs, the optimal value of is equal to the optimal value of its linear relaxation . This allows us to solve this integer linear program by obtaining an integral solution directly from its linear relaxation.

3.2. Primal and Dual Algorithms by Hoffman et al.

Let

be a greedy matrix in standard form, with vectors

,

, and

as variables. Let

,

, and

be constant vectors with

,

, and

. The primal linear program

P is defined as:

The dual program

D is formulated as:

Hoffman et al. [

19] introduced two greedy algorithms to solve

P and its dual

D in polynomial time, and constructed an integer optimal solution for

P. These algorithms are presented in Algorithms 1 and 2.

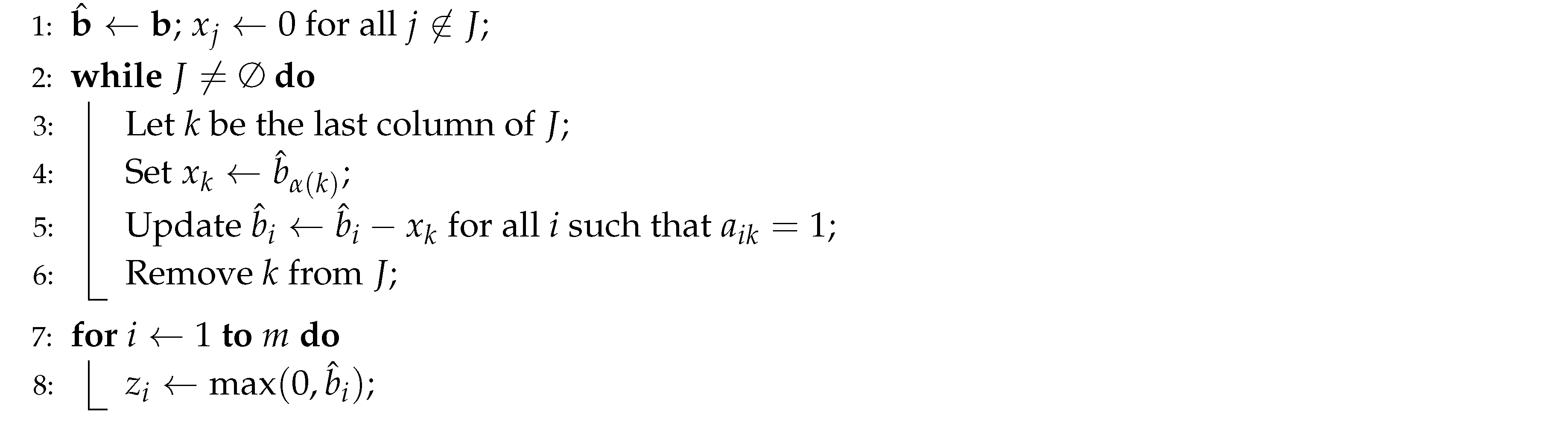

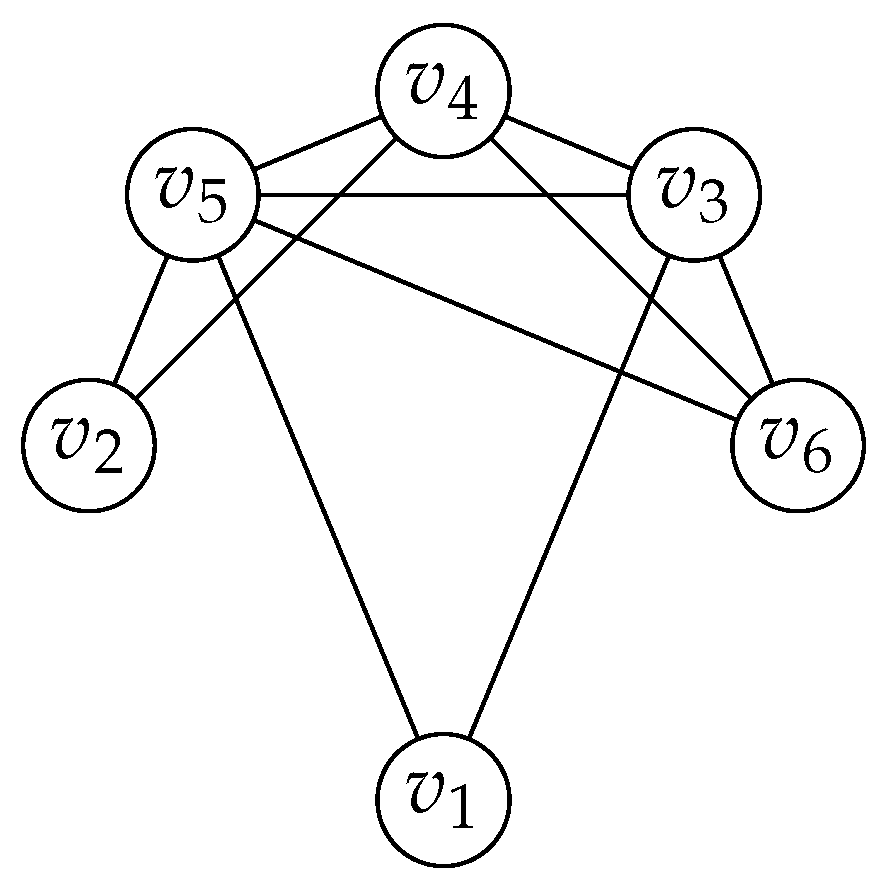

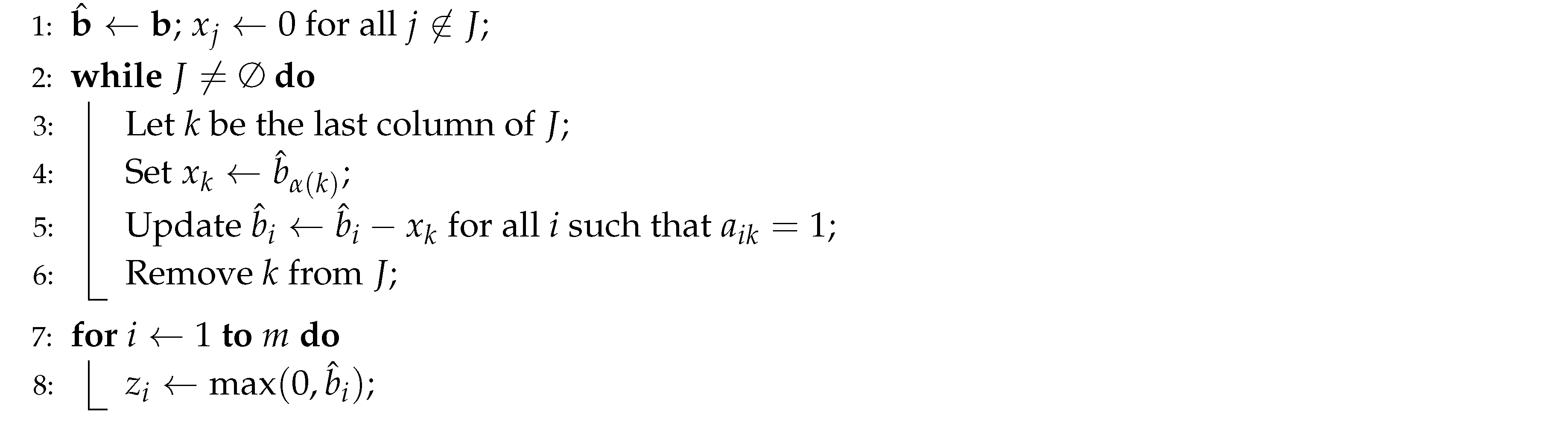

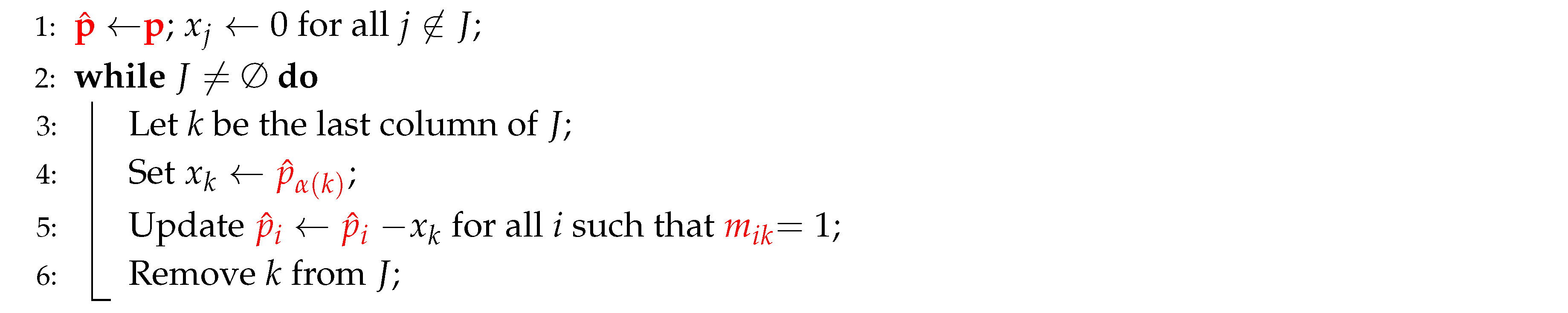

Algorithm 1 provides an integer optimal solution for

D. The dual program

D contains

n constraints and

m decision variables

. A constraint

j is defined as

tight if

Let and . Algorithm 1 determines each variable in increasing order of i and takes the largest feasible value. It also computes J and for use in Algorithm 2.

|

Algorithm 1: Dual Solution for Program D with Greedy Matrices |

|

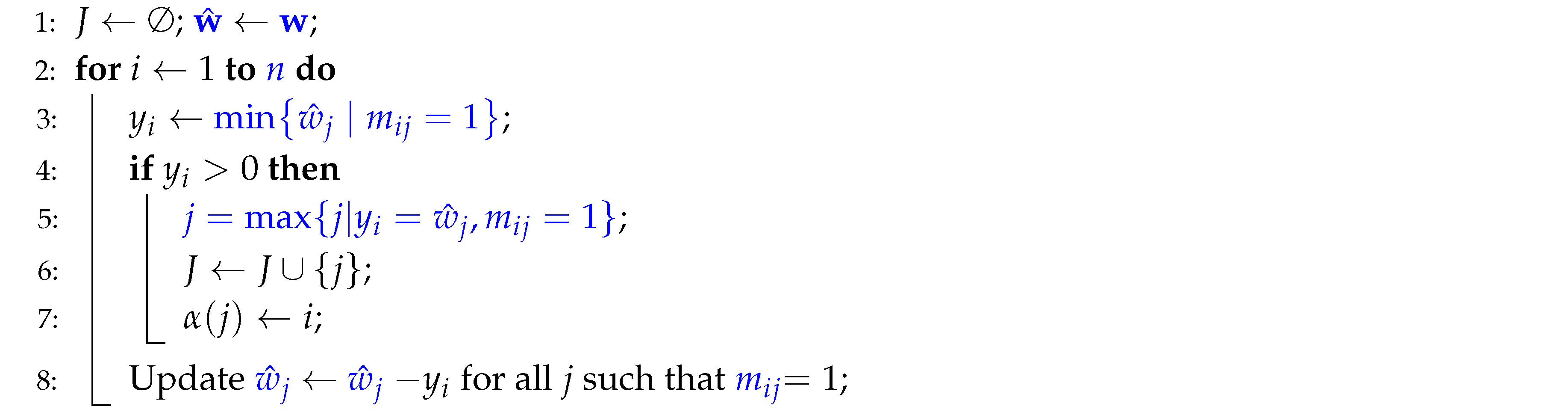

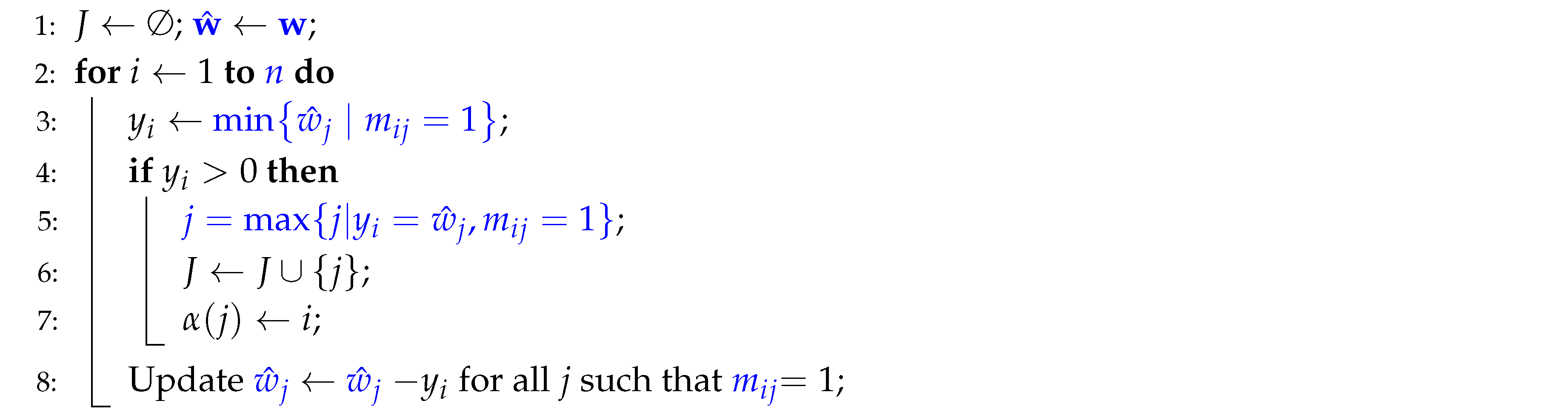

Algorithm 2 computes the primal solution corresponding to the dual solution by iteratively adjusting values.

|

Algorithm 2: Primal Solution for Program P Corresponding to Dual Solution |

|

Theorem 4 ( [

19]).

The dual program D is solved by Algorithm 1 for all , and if and only if A is greedy in standard greedy form. Further, Algorithm 2 constructs an integer optimal solution to the primal problem P. Both algorithms run in time.

3.3. Refined Algorithms for Weighted Strongly Chordal Graphs

We present Lemma 3 as a fundamental observation linking greedy matrices in standard greedy form to the closed neighborhood matrices of strongly chordal graphs with strong elimination orderings.

Lemma 3. If the vertices of a strongly chordal graph G are ordered by its strong elimination ordering, then the closed neighborhood matrix of G is a greedy matrix in standard greedy form.

Proof. We start by proving the following claim.

Claim 1.A greedy matrix in standard greedy form is precisely a totally balanced matrix that contains no submatrix identical to the Γ-matrix.

Let represent the set of all greedy matrices in standard greedy form, and let represent the set of all totally balanced matrices that exclude any submatrix identical to the -matrix. To prove the claim, we will show that .

According to Hoffman et al. [

19], every greedy matrix is totally balanced. This establishes that

.

By definition, a greedy matrix is a

-matrix that does not contain either of the following forbidden submatrices:

It is clear that a totally balanced matrix that excludes any submatrix identical to the -matrix must also exclude and as submatrices. Therefore, any matrix in must also be in , giving us .

Since we have both and , it follows that . This completes the proof of the claim.

Farber [

49] showed that if the vertices of a strongly chordal graph

G are ordered by its strong elimination ordering, then the closed neighborhood matrix of

G is totally balanced and excludes any submatrix identical to the

-matrix.

Thus, the lemma hols. □

For clarity and ease of reference, we present the formulations of

P,

D,

, and

together below.

Theorem 5. For weighted strongly chordal graphs with n vertices arranged by strong elimination ordering, the -domination problem can be solved in time.

Proof. Lemma 3 allows us to observe that for a weighted strongly chordal graph with n vertices arranged in strong elimination ordering, the closed neighborhood matrix of G is a greedy matrix in standard greedy form. Additionally, in the linear program , we have , and the vector is constant with entries equal to k. Consequently, the programs and its dual for the weighted strongly chordal graph are specific instances of the programs P and D, where and the vector is absent.

This connection enables us to modify and simplify Hoffman et al.’s original algorithms, Algorithms 1 and 2, to yield Algorithms 3 and 4. We present Algorithms 3 and 4 below with the necessary line-by-line transformations.

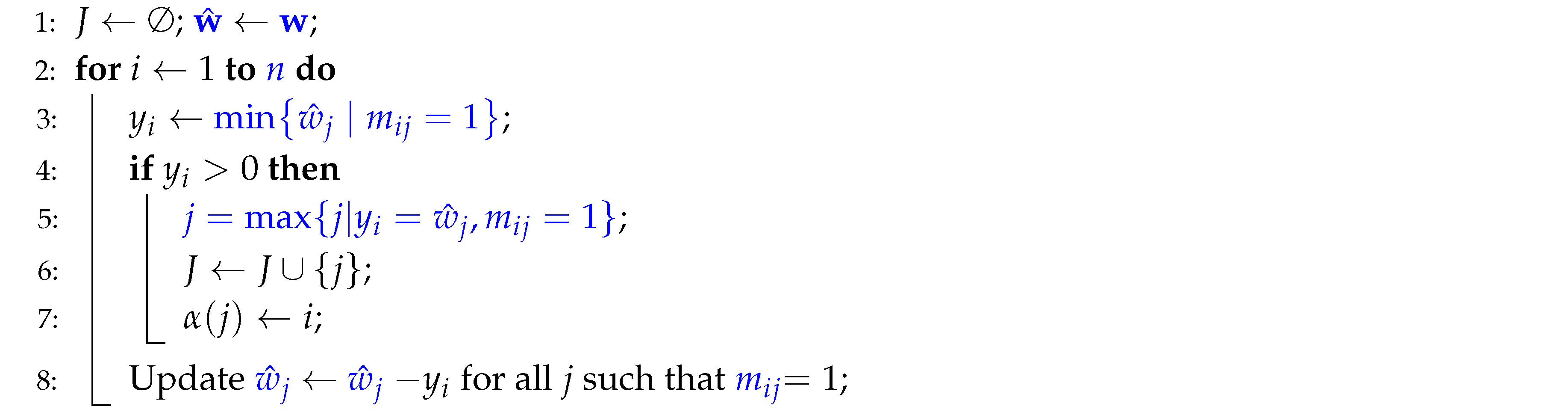

To modify and simplify Algorithm 1 into Algorithm 3, the following line-by-line adjustments (highlighted in blue) were made:

Line 1: Replace with and with .

Line 2: Adjust the loop range from m to n.

Line 3: Simplify the min calculation from to .

Lines 5 and 6: Replace the original lines with the simplified expression . Note that in the simplified algorithm, is unnecessary in Line 3. Therefore, if , then from must equal for some j. Thus, choosing the largest j such that can be expressed equivalently as .

Line 9: Substitute each with and with in the update statement.

|

Algorithm 3: Simplified Algorithm for

|

|

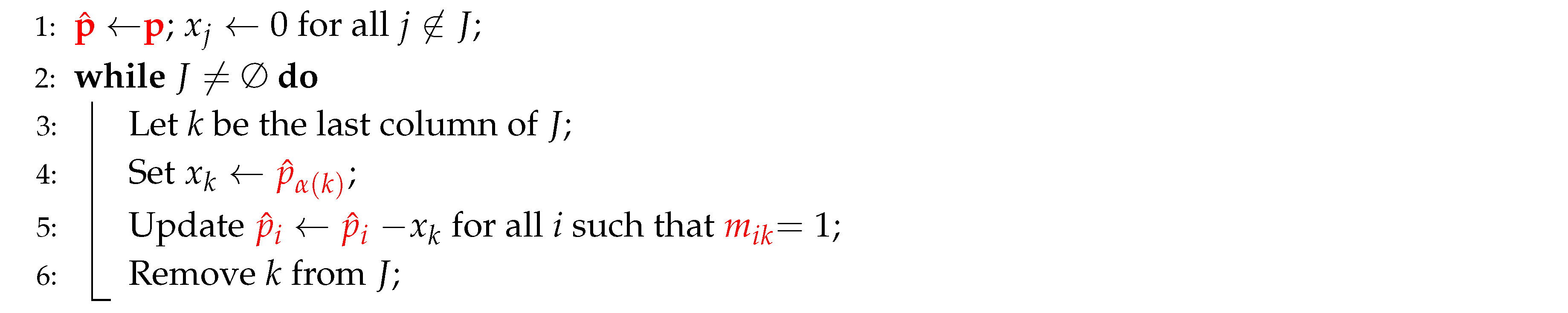

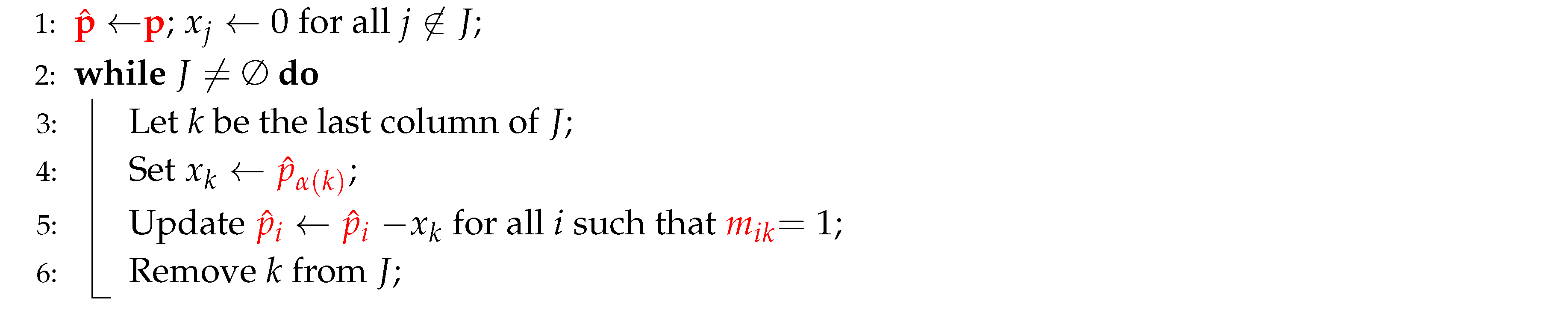

To modify and simplify Algorithm 2 into Algorithm 4, we made the following adjustments (highlighted in red):

Line 1: Change to . Replace with .

Line 4: Adjust to .

Line 5: Replace with . Replace with .

Remove Lines 7 and 8, since they are unnecessary in the simplified algorithm for .

|

Algorithm 4: Simplified Algorithm for with Totally Balanced Matrices |

|

By Theorem 4, the linear program and its dual are solvable in time for weighted strongly chordal graphs G with vertices in strong elimination ordering, and Algorithms 3 and 4 can provide integer optimal solutions for and . Thus, the -domination problem for weighted strongly chordal graphs can be solved in time. □

3.4. Optimized Algorithms with Enhanced Data Structures

In the previous section, we established that the linear program and its dual are special cases of the problems tackled by Hoffman et al.’s algorithms. This enables us to apply their method directly to solve these programs in time. Hoffman et al.’s algorithms are robustly constructed around the relationships between totally balanced matrices, greedy matrices, and linear programs, using the strengths of matrix structures and concepts from linear and integer programming. In contrast, the closed neighborhood matrices in are closely tied to graph adjacency structures.

The adjacency-list representation, as discussed in

Section 2.1, plays a crucial role in enhancing the efficiency of Algorithms 3 and 4. By incorporating optimized data structures for critical steps in these algorithms, we improve the overall time complexity from

to

, where

n represents the number of vertices, and

m represents the number of edges in a graph. Since the maximum number of edges in a graph is

, this improvement makes the algorithms particularly effective for sparse strongly chordal graphs when

. Theorem 6 demonstrates how to obtain the desired time complexity.

Theorem 6. For weighted strongly chordal graphs with n vertices arranged by strong elimination ordering, the -domination problem can be solved in time, where m is the number of edges in G.

Proof. We begin with demonstrating how each line of Algorithm 3 relates to the adjacency list and other optimized data structures and the running time of each line based on the adjacency list representation and the number of vertices (

n) and edges (

m):

|

Algorithm 3: Simplified Algorithm for

|

|

-

Line 1:

This line initializes the set J to keep track of selected indices j and makes a copy of the vector as . This step does not directly involve the adjacency list, as it’s a basic initialization of variables. We implement J as an array with n entries and initialize the array with each entry set to zero. This array structure allows us to store specific information about each element efficiently, and each entry can be accessed, updated, or retrieved in time. The initialization step takes time.

-

Line 2:

This loop iterates over each index i, where n corresponds to the number of constraints equal to the number of vertices. It executes n times in total. For each iteration, it processes Lines 3–8.

Line 3: For each i, the algorithm assigns the minimum value among the entries for all j such that . Clearly, means . Using the adjacency list, the algorithm can directly access all neighbors of , including itself, in time.

-

Line 4:

This line checks whether the calculated value is greater than 0. It can be done in time

-

Lines 5-7: This block finds the largest j for i such that and .

The adjacency list helps here by providing access to each index j of , allowing the algorithm to identify all possible values of j where . Once the appropriate j is found, J and are updated. Since J is an array, the operation is translated to setting . Conversely, J does not contain some k if . We also implement the operation by an array. The operation is translated to setting .

Hence, the steps take time.

-

Line 8:

This line updates for each index j of vertices , subtracting from . Using the adjacency list, the algorithm can efficiently locate each j where and apply the update only to those specific j values for vertices .

The overall time complexity depends on the sum of all neighbor operations across vertices, yielding

where

n is the number of vertices and

m is the number of edges.

We next demonstrate how each line of Algorithm 4 relates to the adjacency list and other optimized data structures and the running time of each line based on the adjacency list representation and the number of vertices (

n) and edges (

m):

|

Algorithm 4: Simplified Algorithm for with Totally Balanced Matrices |

|

-

Line 1: This line initializes as a copy of and sets for all .

To set for all , we implement a stack and set it to be empty. Then, we visit each entry for , set if , and push j into the stack if . After visiting all entries of J, we delete J and rename with J. All operations can be done in time. Since also has n entries, copying and takes time.

-

Line 2 (While Loop): The loop runs until J is empty, so the number of iterations depends on the number of elements in J. Clearly, it executes at most n times. Each iteration involves Lines 3–6, so we analyze each of these lines within the context of a single iteration.

Line 3: Select the last column k from J. In other words, we have to select the largest index k of J with . Since we have implemented a stack, pushing each index j with into the stack from smallest one to the largest one, deleting J, and renaming the stack with J and deleting . Therefore, selecting the last column of J is equivalent to popping an element from J. Hence, it takes time.

Line 4: Set based on . Retrieving the value from and assigning takes time.

Line 5: Update for all i such that . Since , this operation iterates over each index i of vertices . Using the adjacency list, this step takes for each iteration.

Line 6: Remove k from J. J is implemented as a stack. Removing the last element takes time.

The overall time complexity of the algorithm is:

where

n is the number of vertices and

m is the number of edges in the graph. This linear time complexity makes the algorithm efficient for sparse graphs.

Following the discussion above, Algorithms 3 and 4 both run in time. Consequently, the theorem holds. □

4. Total -Domination in Weighted Chordal Bipartite Graphs

The total -domination problem in weighted chordal bipartite graphs can be efficiently solved by structural properties of these graphs. Specifically, we demonstrate how the neighborhood matrix of a chordal bipartite graph ordered by its weak elimination ordering forms a greedy matrix in standard greedy form. The following lemma establishes the foundational connection between weak elimination orderings and greedy matrices.

Lemma 4. If the vertices of a chordal bipartite graph are ordered by its weak elimination ordering, then the neighborhood matrix of the graph is a greedy matrix in standard greedy form.

Proof. Let

G be a chordal bipartite graph with the vertices ordered by its weak elimination ordering

, and let

be the neighborhood matrix of

G. Since the neighborhood matrix of a chordal bipartite graph is totally balanced [

49],

is totally balanced. We now check if

contains the

-matrix as a submatrix:

Assume that

contains the

-matrix as a submatrix, shown below with entries chosen by rows

and columns

, where

and

:

Since is a neighborhood matrix, each is 0 for . It imples that , , and . Furthermore, as bipartite graphs contain only cycles with even number of vertices, if , then , and would form a cycle of odd number of vertices, which is impossible. Thus, .

Consider three cases:

Case 1:. Then, , and are all vertices of . Since is adjacent to both and , the neighborhood relationship must hold. As , it follows that . However, this implies that is adjacent to , which contradicts the assumption that and are not adjacent.

Case 2:. In this case, , and are all vertices of . Since is adjacent to both and , the neighborhood relationship must hold. Consequently, implies . However, this contradicts the assumption that and are not adjacent.

Case 3:. Here, , and are again vertices of . By reasoning similar to Case 2, the adjacency of to both and implies . Since , we deduce that , which means and are adjacent. This contradicts the assumption that and are not adjacent.

These cases confirm that is totally balanced and excludes the -matrix as a submatrix. By Claim 1, we conclude that the neighborhood matrix of a chordal bipartite graph ordered by its weak elimination ordering is a greedy matrix in standard greedy form. □

The following lemma is similar to Lemma 1. It allows us to concentrate exclusively on non-negative vertex weights ().

Lemma 5. Let w be a vertex-weight function of a graph , and let represent the the minimum labeling weight of a total -dominating function for . Define and let be a vertex-weight function such that for each . Then, .

Proof. This lemma can be proved by the arguments similar to those for proving Lemma 1. □

Let G be a chordal bipartite graph with the vertices arranged in weak elimination ordering with as its neighborhood matrix. Let , , and , where for .

The total

-domination problem for weighted chordal bipartite graphs can be formulated as the following integer linear program

:

Let

be the linear relaxation of

, and let

be the dual program of

. We present the formulations of

P,

D,

, and

together below:

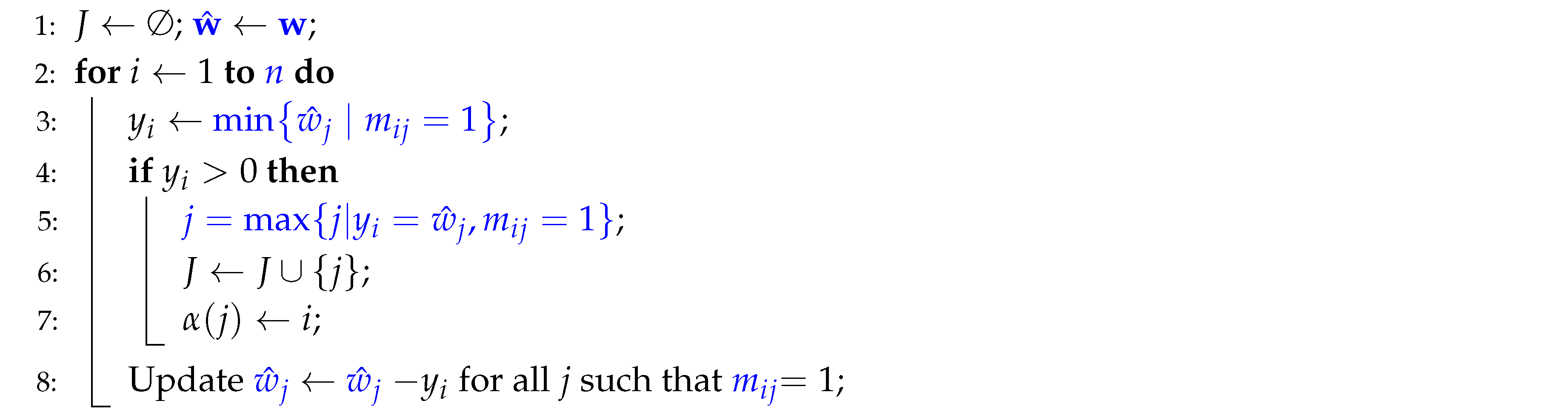

Theorem 7. For weighted chordal bipartite graphs with n vertices arranged by its weak elimination ordering, the total -domination problem can be solved in time, where m is the number of edges in G.

Proof. The proof proceeds in three steps:

Neighborhood Matrix Properties: By Lemma 4, we have established that for a weighted chordal bipartite graph with n vertices arranged by its weak elimination ordering, the neighborhood matrix of G is a greedy matrix in standard greedy form. This property ensures that the constraints of the total -domination problem are well-structured for efficient computation.

Connection to Linear Programs: The primal and dual linear programs, and , for the weighted chordal bipartite graphs are specific instances of the linear programs P and D, where and the vector is absent. These simplifications reduce the computational overhead associated with solving the general cases.

Efficient Computation: Using arguments similar to those in the proofs of Theorems 5 and 6, we use the greedy matrix property of and advanced primal-dual algorithms to solve the relaxed problem efficiently. Optimized data structures ensure that each step in the algorithm operates in linear time relative to the size of the graph.

Combining these observations, the total -domination problem for weighted chordal bipartite graphs can be solved in time. □