This study introduces a variation of the Roman domination problem in graphs. In previous works, we explored the [k]-Roman domination model, which involves defending against single attacks requiring at least k units, focusing on the case. In this work, we extend the model by guaranteeing that stronger vertices are not isolated.

The concept of total domination can be incorporated into the triple Roman domination model to prevent isolated vertices among labeled ones, strengthening the network at the potential cost of higher expense.

A total triple Roman dominating function (t3RDF) satisfies both triple Roman domination and secures no isolated vertices in the induced subgraph by vertices with positive labels. The total triple Roman domination number, is the minimum weight of a t3RDF.

This paper introduces the total triple Roman domination model. We examine the algorithmic complexity of the decision problem, provide bounds, describe extremal graphs, and find exact values for several graph families.

2. Complexity

The goal of this section is to prove that the total triple Roman domination decision problem (t3RDP) is NP-complete even for bipartite graphs.

We prove it by showing the equivalence of any instance of the t3RDP with an instance of one of the Exact 3-Cover (X3C) problem. Formally, we consider the following decision problems:

PROBLEM

Instance: Graph and a positive integer K.

Question: Does G have a t3RD function f with ?

PROBLEM

Instance: A finite set and a collection C of 3-element subsets of X.

Question: Does there exist a subset such that every element of X appears in exactly one element of ?

Proposition 1. is -complete for bipartite.

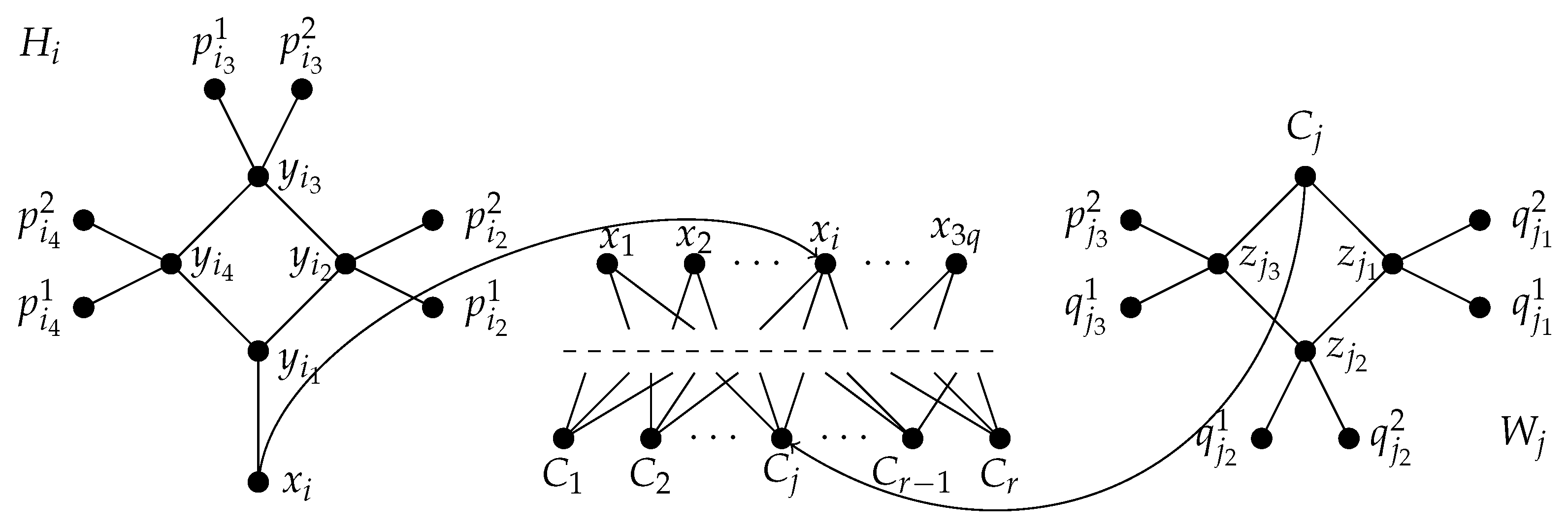

Proof. We can readily prove that t3RDP is in the NP-class because any potential solution can be verified in polynomial time. We now show that converting any instance of to an instance of t3RDP results in equivalent solutions for both problems. Consider and , an instance of . For each , we include a gadget by adding two pendant vertices to each vertex for of the cycle . Additionally, for each , we construct the gadget by adding two pendant vertices to each vertex of the path .

We construct the graph as follows: we start with a bipartite graph with set of vertices such that is adjacent to if and only if We add the gadgets by joining the vertices with a new edge, for and, analogously, we add the gadgets to the graph by the edges for .

Clearly, the constructed graph is bipartite with vertex classes

and

Now, assume that there exists

which is an exact cover for the set

Let

f be a function over the vertices of

defined as follows:

if

and

otherwise. Since

is a solution of the

for the instance

we may deduce that

. On the other hand,

for all

and the induced subgraph by the set of vertices with a positive label has no isolated vertices. Hence,

f is a t3RD function with

To complete the proof, suppose that f is a t3RDF with Since are support vertices and f is a t3RDF, we may assume that for all Analogously, without loss of generality, we may assume that for

If for some then we may define a new function as follows: , , where is a clause containing . As the vertex is total triple dominated by any of the vertices with we have that is a t3RDF with weight at most . So, we may assume that for all

Analogously, if for some , the function , , where is a clause containing . Since the vertices are adjacent to both with then we have that is a t3RDF having weight at most . Then, we may assume that for all

In such a case, we have that which implies that

Let be

and suppose that

Then the number of vertex

with some neighbour in

is at most

As a result,

and also

for each vertex

without neighbours in

And, given that the cardinality of

is three, it must be

which is a contradiction.

Therefore with if and if Besides, as and for all then there exist with . And taking into account that and the cardinality of is three, then the elements of are disjoint from each other.

Hence, solves the instance of the problem. □

Figure 1.

Gadgets and bipartite graph .

Figure 1.

Gadgets and bipartite graph .

3. Bounds

Once we have shown that calculating the exact value of the total triple Roman domination number (t3RDN) is an NP-hard problem, it is a natural step forward to bound this parameter in terms of well-known structural features of a graph.

Clearly, the t3RDN of a non-connected graph is the sum of the t3RDN of its components. Besides, as we have mentioned above, the total version of this domination problem only makes sense for isolated vertex-free graphs. Therefore, since we need any undefended vertex to be able to receive at least 3 units from its active neighbors, it is straightforward to derive a first upper bound by assigning a label 2 to each vertex in the graph.

Proposition 2. Let G be a connected graph of order n. Then . Equality holds if and only G is the corona product of a connected graph H with a .

Proof. Let f be the function defined as for all Clearly, f is a t3RDF and therefore

If and f is a -function then is an even integer and for each leaf where v is the corresponding support vertex. Hence, and the equality holds.

On the other hand, suppose that . If then and the result holds. So, we may assume that If then which is impossible because So, assume that

Let v be a vertex with maximum degree in G and denote by its neighborhood. First, suppose that . If there exists a vertex w such that then consider such a vertex having minimum degree and denote by its neighbors. Now, we may define a function f as follows ; ; and otherwise. By our choice of w, every vertex labeled with a 2 is adjacent to a vertex with a positive label. The vertices having a label 0 are adjacent to both v and w, therefore f is a t3RDF in G and a contradiction. If for all then we may define a function f as follows ; ; and otherwise. We can readily check that f is a t3RDF in G and hence again a contradiction.

So, we can deduce that it must be . If there exists a strong support vertex v such that are its leaves, then we can define a function f as follows: ; and otherwise. It is straightforward to check that f is a t3RDF and then Hence, there are only weak support vertices in G. If there exists a vertex which is neither a leaf nor a support vertex then we may define a function f as follows and otherwise. Since then f is a t3RDF and which is not possible.

Then, every vertex in G is either a leaf or a weak support vertex, which finishes the proof. □

Our next results give us an upper bound for the t3RDN in terms of the maximum degree of the graph.

Proposition 3. Let G be an ntc-graph maximum degree . Then .

Proof. Consider a vertex with maximum degree and let be the neighborhood of v. Let us define the function as follows for and for the remaining vertices. Then f is t3RDF and □

Some graphs, including the path and the cycle attain this bound. Furthermore, we can readily verify that the upper bound given in Proposition 3 improves upon the one presented in Proposition 2 whenever .

Proposition 4.

Let G be an ntc-graph of order n, , girth and maximun degree Then

Proof. Consider a vertex

with maximum degree

and let

be the neighborhood of

v. Let us define the function

as follows

for

and

for the remaining vertices. Let

z be any vertex belonging to

. Since

and

then

. Therefore, there exists

such that

and

Since

has not isolated vertices, then

f is a t3RDF and

□

As shown in

Table 1, these bounds are not comparable. There are graphs for which each bound is better (boxed) than the others.

The upper bound can be significantly improved in the case of dealing with a regular graph, as demonstrated by the result we prove next.

Proposition 5. Let G be an r-regular connected graph of order n and girth . Then

Proof. Let

v be any vertex of the graph

G and let us denote by

and

. Clearly,

and

because the girth is at least

Consider the function

defined as follows:

for all

for all

and

otherwise. Since

and the girth is greater than or equal to 7, we may readily verify that

f is a t3RDF. Hence

□

Although the upper bound matches the exact value, for example, of , it is worth pointing out that the girth condition is essential. It is not difficult to check that whereas the upper bound given by Proposition 5 would imply that

In what follows, it is important to keep in mind certain conditions that, without loss of generality, we may assume a -function satisfies.

Remark 1. Let f be a -function of an ntc-graph G. Let v be a support vertex whose leaves are the vertices , with . Then,

If v is a weak support vertex then and

If v is a strong support vertex such that for all then we may suppose that ; and , for all

If v is a strong support vertex such that there is a vertex with then we may assume that and for all the leaves .

To close this section, we prove several results in which we bound the total triple Roman domination number of a graph in terms of other domination parameters such as the (total) domination number or the total double Roman domination number.

Proposition 6. Let G be an ntc-graph, then .

Proof. Let

D be a

-set and

the isolated vertices in the induced subgraph

. For each

we consider a vertex

and let us denote by

. Consider the function

defined as follows:

, for all

for all

and

for the remaining vertices. Then

□

This bound is met by infinitely many graphs, such as those that contain a universal vertex.

Corollary 1. Let G be an ntc-graph. Then, if and only if every γ-set is a 3-independent set.

Proof. If

then the inequalities in (

1) become equalities. Therefore,

and all the dominating vertices are isolated in

. Since

then there is no common neighbor

for any pair

of distinct vertices. Consequently, every

-set is a 3-independent set. □

Proposition 7. Let G be an ntc-graph with at least 3 vertices. Then .

Proof. Let S be a -set of G and let . We can readily prove the upper bound by considering a function g such that for all . This function g is a t3RDF and hence

Next, we prove the lower bound. Assume that

is a

-function. Since

is a total dominating set, we have that

If then and we are done. So, assume that If then either or or , and therefore So, the only case that remains to consider is But in this situation, which concludes the proof. □

Proposition 8.

Let G be an ntc-graph. Then

Proof. First, to prove the lower bound, consider a -function. If then is a tdRDF with weight and hence

Assume now that , which implies that . Let be a vertex and consider the function defined as follows: and otherwise. First, observe that the set still total-dominates the graph G. On the other hand, the set of active neighbors of all vertices of V does not change regardless of which function f or g we consider. Therefore, if and then If and then Hence g is a tdRD function having weight and

To prove the upper bound, we consider

a

-function and let us define the following function

if

if

and

otherwise. Then,

f is a t3RDF of

G and we may readily deduce that

This fact, and the bound given by the Proposition 6, leads us to the desired result. □

We conclude by providing two lower bounds in terms of the order, maximum degree and domination number of the graph, some of which follow from well-known bounds for the triple Roman domination number.

Proposition 9. Let G be an ntc-graph with . Then

Proof. Let

f be a

-function of

G. Then

because

(resp.

) is a total dominating (resp. dominating) set of

□

Proposition 10.

Let G be an ntc-graph of order n. Then

Proof. This bound is an immediate consequence of

and the following lower bound, proved in [

2],

□

Besides, by applying the upper bound proved in [

15] we may derive that

Remark 2.

For any ntc-graph G of order and maximum degree we have that

4. Exact Values of the Total Triple Roman Domination Number

Our aim in this section is to characterize those graphs that have the first few smallest values of the parameter

. Also, prove several results regarding the exact values of the t3RD-number for certain graph families. In what follows, we make use of the following notation. Given a positive integer

, let

and

Proposition 11. Let G be an ntc-graph with order . Then if and only if

Proof. Let u be a vertex with maximum degree and . Consider a function defined as follows and , for al . We can readily check that f is a t3RDF of G. Hence, On the other side, assume that G is an ntc-graph with at least 3 vertices and let be a -function. If then for any vertex we have that and therefore If then either , which implies that or and or In any case, we deduce that

Assume now that and . Let be a -function. If , then either or . In any case, since f is a t3RDF, the vertex labeled 3 or 4 is universal. Hence, .

Otherwise, suppose that , which implies that because f has minimum weight. Since we have that either and or and . In these cases, and we are done. □

Proposition 12. There is no ntc-graph G such that

Proof. Let G be an ntc-graph with and let be a -function of G. If either or or or then the vertex having the greatest label is a universal vertex because f is a t3RD function, which is a contradiction with Proposition 11.

If and , then , and once again, we deduce that the vertex in is universal. Hence, . If , then at least one of the vertices in must be adjacent to the other two vertices in . Furthermore, since every vertex in must be adjacent to each vertex in , we conclude that , once again leading us to a contradiction.

Lastly, suppose that and , which implies that . The vertices in must all be adjacent, and each vertex in must be adjacent to both vertices in . Therefore, both vertices in are universal, which completes the proof. □

Next, we provide some technical results that will allow us to establish the main results of this section concerning the exact value of the t3RD number for paths and cycles.

Lemma 1. Let G be an ntc-graph of order n and Let f be a -function such that the number of vertices assigned 0 under f is minimized and let be an ordered set of vertices that induces a path in G. Then the following conditions hold,

- L1

for all .

- L2

If and , then there exists a -function g such that and .

- L3

If and , then there exists a -function g such that and .

- L4

If and , then there exists a -function g such that and .

Proof. Since G is an ntc-graph with , it follows that G is either a path or a cycle. Let be the vertices of G.

L1. Suppose a vertex exists, say , such that . If and , then we can define g as follows: and for . So, g is a t3RDF of G with weight , which is a contradiction. Without loss of generality, assume that and . Then the function g defined by , and for , is a t3RDF of G with weight . Thus, g is also a -function, with against our assumptions. Therefore, the result holds.

L2. Since f is a t3RD function, and then it must be . On the other hand, as and then we have that So, we can define a function g as follows and otherwise. Hence, g would be a t3RDF of G with weight and The proof of items L3 and L4 are quite similar to this one and we leave the details to the reader. □

Lemma 2. Let G be an ntc-graph with If is an ordered set of vertices that induces a path in G, then there exists a -function g such that

Proof. Let f be a -function such that the number of vertices labeled with a 0 under f is minimized and let be the set of vertices of G. Suppose on the contrary, that , for all . We have to consider several cases,

Case 1. If and , for all and then we can define a function g in the following way: , and otherwise. Therefore g is a t3RDF of G with weight and .

Case 2. If and , for all then we can define g as , , and otherwise. Therefore g is a t3RDF of G with weight and .

Case 3. If and, without loss of generality , then we consider , and otherwise. Therefore, g is a t3RD function with weight and .

Case 4. If , , , and then . We can define a new function g such that , and otherwise. Hence, g is a t3RDF of G with weight and . □

Proposition 13. Let G be an ntc-graph with maximum degree , order and let be a -function such that is minimized. Then .

Proof. First of all, note that since we only have to prove the result for cycles. For we may readily check that that satisfies the inequality.

Let us suppose that , f be a -function and be consecutive vertices of . Without loss of generality, by applying Lemmas 1 and 2, we only have to consider the following situation

If

then

. Therefore, the function

g defined as

and

otherwise, is a total double Roman dominating function in the cycle

with weight

By applying Proposition 8, since

we can conclude that

□

Proposition 14. Let G be an ntc-graph with , and let be a t3RDF on G, such that the number of vertices assigned 0 under f is minimum. Then .

Proof. Since

, we can restrict ourselves to proving the result for paths. To do that we proceed by induction on the order

of the path. The labellings shown in

Table 2 permit us to state that the bound is correct for all

So, let us assume that

and that

for all

Denote by

, where

y

and consider

a

-function. Then, the function

g defined as

and

for all

is a t3RDF in

with weight,

that finishes the proof. □

Let us point out that, by Propositions 13 and 14, we know that for any path or cycle G of order .

Lemma 3. Let T be a tree and v be a leaf vertex of T. Let M be the tree obtained from T and the star , with by adding an edge between v and a leaf of the star . Then

If then

If and there exists a -function f such that then

If and for all -function f then .

Otherwise, we have that

Proof. To begin with, let us assume that

. Let

be a

-function on

T and let

and

be the vertices of

such that

is adjacent to

v in

M. Let

g be a function defined as

and

for all

So,

g is a t3RDF on

M and

On the other hand, let f be a -function and let be the neighbor of v in T. By applying Observation 1 we have that and, therefore,

If then the function g defined as follows for every and otherwise is a t3RDF in T having weight, at most, and we are done.

Now, if , then the function g defined as follows for every and is a t3RDF in T having weight, at most, , as desired.

On the contrary, if then we have that and hence because v must be total-triple-Roman dominated by Hence, the function g defined as follows for every and is a t3RDF in T having weight, at most, .

Let us now assume that

and that there is a

-function

f such that

Since

f is a

-function such that

then we can define a function

g in the following way

for all

,

which is a t3RDF on

M and hence

Moreover, if g is a -function then by Observation 1 we have that . Let us define the function on T as follows and otherwise. The function is a t3RDF on T and therefore which lead us to as desired.

Next, let us suppose that and for all -function If f is any -function then the function for all , and is a t3RDF on M, leading us to

Now, to prove the other inequality, let us consider g a -function. Then, by Observation 1, we have that . If then is a -function and, by our assumptions, must be less than or equal to 1, which implies and a contradiction because So, it must be

Reasoning by contradiction, let us suppose that and hence As we may deduce that is not a t3RDF. This may be due to either or either We can define a function on T as follows, and otherwise. Then, and because g is a t3RDF and is an active neighbor of v. Hence, is a t3RD function on T. Moreover, if then and if then because whereas . In any case, against our assumption.

The proof of the case is analogous to the earlier case. □

Theorem 1. Let be a positive integer. Then .

Proof. We can readily check that whenever . By applying Propositions 13 and 14 we know that and .

Let be a -function on such that the number of vertices assigned 0 under f is minimum. For simplicity, we occasionally represent a domination function defined on a path with n vertices denoted by , as an ordered n-tuple , where for each .

Let us note that and the following labelings correspond to -functions for , respectively. Therefore, by applying Lemma 3, we derive that

Analogously, since and the labeling is a -function, it follows from Lemma 3 that . It is straightforward to see that and are the only minimum possible labelings of and , respectively. Thus, by applying Lemma 3 again, we deduce that and .

Let and q be positive integers such that with . Let us denote by , whenever and , otherwise.

We define the following function

whenever

. Besides, if

then

. Finally, if

then

and for the remainder vertices we establish the values of

in the

Table 3.

Observe that,

If then

If then

If then

If then

If then

If then

If then

If then

Therefore, we have that for all and that for all

To prove that for all we reason by induction. Let be an integer and assume that for all Let us denote by such that the edges of the path are whenever So, we know that and, by applying Lemma 3, we may derive that . Analogously, it is deduced that .

Let g be a -function such that the number of vertices with a label 0 is minimum. By Observation 1, we have that and, without loss of generality, we may suppose that If we are done because

Hence, assume that which implies that is not a t3RDF in because This may be due to several reasons, and we must study different situations.

Case 1: . In this case, by Lemma 1, we have that If then we have to study two different possibilities: either and or and . In both cases, we may define the following function and otherwise. The function is a t3RDF having the same weight of g. We can proceed similarly if or Therefore, we may assume that Since then

Case 1.1: . Then, and . Thus, is a t3RDF in and consequently implying that

Case 1.2: . Then, we may define the following function and otherwise. The function is a t3RDF under the conditions of Case 1.1.

Case 2: In this case, we may define the function and otherwise, which is a t3RDF under the conditions of Case 1.

Case 3: Clearly, because is not a t3RDF in Besides, and we have that is a t3RDF in and so .

Case 4: We can define the function and otherwise, which is a t3RDF under the conditions of Case 3.

Summarizing, we have shown that which concludes the proof. □

Theorem 2.

Let be a positive integer. Then

Proof.

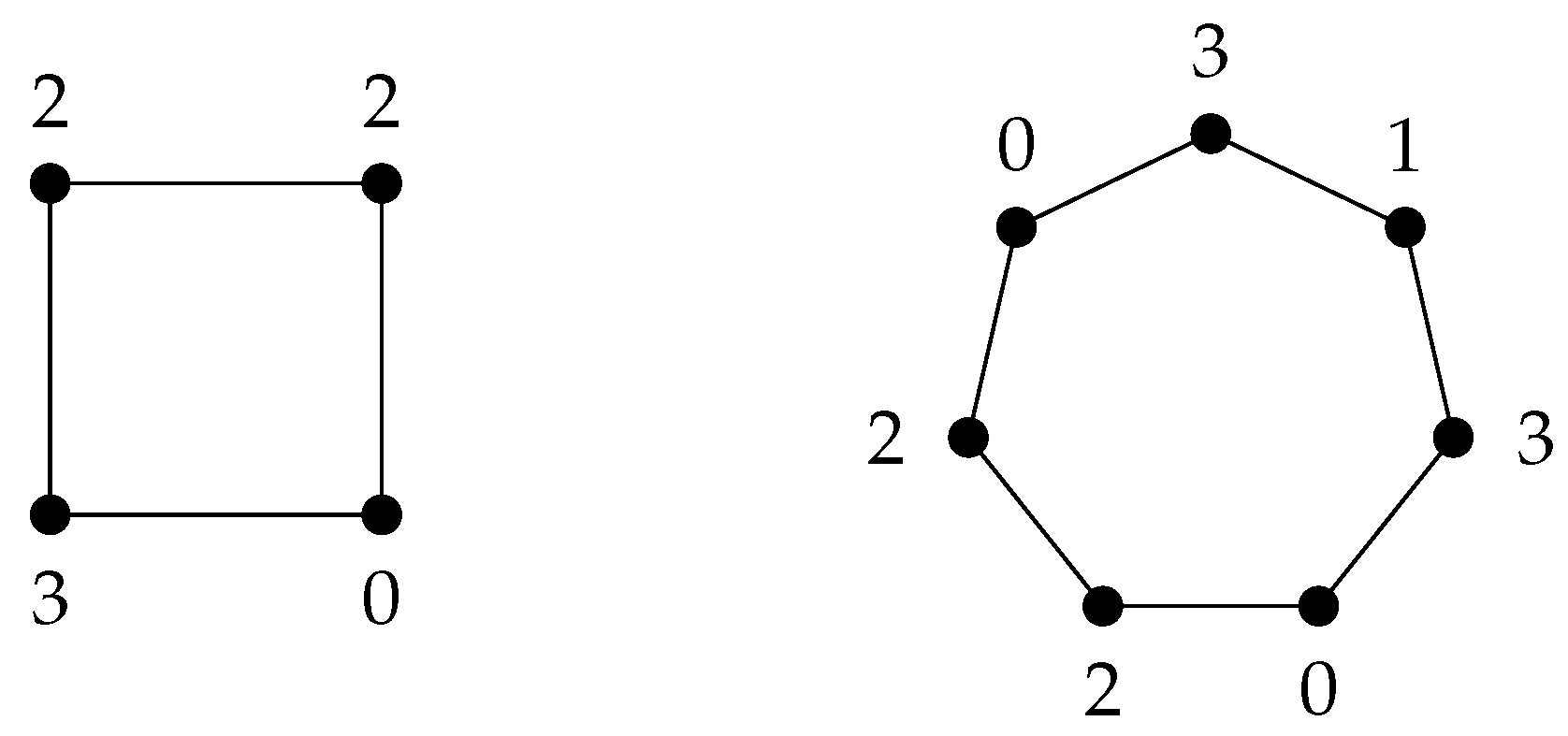

Note that whenever and for

First, as shown in

Figure 2, we have that

for

. On the other side, since

then we also have that

for all

To prove the other inequality, we proceed by induction on the order of the cycle. By Proposition 13, we have that

Let be an integer, and assume that for all Denote by the set of consecutive vertices of the cycle. Let f be a -function such that the number of vertices labeled with 0 is minimum which by applying Lemma 1 implies that . Since , we may consider five consecutive vertices, say . By Proposition 2, we can assume that and, again by Lemma 1, we may suppose, without loss of generality, that and We have to discuss some different possibilities.

Case 1: In this case, it must be and

Case 1.1: We can readily check that for . Let and consider the cycle or order obtained by joining and Thus, is a t3RDF and

Case 1.2: Then it must be and the cycle or order obtained by joining and satisfies that is a t3RDF with

Case 1.3: which implies and If then and Thus, assume that If is adjacent to then and Thus, assume that and consider the cycle or order obtained by joining and . Again, is a t3RDF with

Case 2: Then, it must be Let be the cycle or order obtained by joining and We have that

Case 3: If so, we may consider the cycle or order obtained by joining and We can readily check that is a t3RDF and

That concludes the proof. □