1. Introduction

Xanthomonas campestris pv.

campestris (Xcc) is important bacterial plant pathogen causing black rot disease damaging cruciferous crops worldwide [

1] Xcc is gram-negative, rod shaped bacterium and symptoms of infection of plants includes V-shaped dark, necrotic lesions on leaves, blackened veins [

1,

2]. On the field, Xcc infects the host plants by penetrating the stomas, hydathodes of wounds and spread inside the plant through vascular system. Since, the pathogen is seed-borne, it is more difficult to control and easier to spread within the regions with cruciferous crop production [

3]. Cruciferous plants include many economically important crops worldwide such cabbage, kale, broccoli, oilseeds, mustard. According to Food and Agriculture Organization of United Nations (FAO), the estimated worldwide production reached 72.60 million tonnes in 2022. Over 56 million tonnes of cruciferous crops if produced in Asia, 8.5 million tonnes in Europe, 4.3 million tonnes in Africa and rest is covered by America and Australia and Oceania regions. Cruciferous crops are typical crops of temperate climate zone [

4,

5]. In the regions or years with favourable conditions (high humidity, higher temperatures) the black rot may cause several economic losses of crop production [

6]. Within the Xcc, 11 races have been identified based on avirulence/virulence patterns. Race 1 was identified as most virulent and widespread in

B. oleracea crops, representing more than 90 % of black rot disease worldwide, together with race 4 [

7].

The source of contamination of Xcc, beside the infected seed, is post-harvest debris or cruciferous weeds. With favourable conditions, including higher precipitation and temperatures between 25 – 30 °C, Xcc enters the vascular system of host plants via hydatodes or damage caused by insect, animals or human activity [

3,

8,

9]. The root system may also serve as portal of infection [

10]. According to several studies,

X. hortorum pv.

pelargonii cause overall wilt and gradual plant death of host plant as it expands to root system without no decay or soft rot symptoms [

11,

12,

13]. There are several agricultural practices that can prevent the infection including use of Xcc free planting material, crop rotation, disposal of plant material that can be source of infection on the field [

9]. Furthermore, many studies assessed the effect of various treatments of seeds such as hot water treatment, nanoparticles treatment or ultraviolet doses as effective to control black rot infection, however, such a treatment may have also negative impact on germination rate [

14,

15,

16]. Another novel approach of black rot control includes use of bacteriophages, which seems to have promising results [

5,

17]. Application of plant-growth promoting bacteria (PGPB) (

eg. Bacillus, Pseudomonas, Enterobacter, Streptomyces) on rice (

Oryza sativa) not only enhanced plant growth but as well improved biocontrol against important rice pathogen

X. oryzae pv

. oryzae. Many of PGPB are applied through root system, colonized it and induce defence response against pathogen bacteria [

18,

19]. Thus, the understanding of Xcc colonization of the vascular system within whole plant, both root and above ground parts, is essential for development of novel approaches of black rot control [

20].

Host range of Xcc includes many important cruciferous crops such as cabbage (

B. oleracea var.

capitata), broccoli (

B. oleracea var.

italica), kale (

B. oleracea var.

sabauda; Brassica oleracea var.

sabellica), cauliflower (

B. olearceae var.

botrytis), kohlrabi (

B. oleracea var.

gongylodes) etc. Screening for resistance genes within Brassica species confirmed partial resistance to several races of Xcc in species

B. rapa, B. juncea or

B. napus [

3,

21]. Even though, Xcc isolates obtained from different cruciferous crops induced symptoms after artificial inoculation on seven different brassicas, the differences in their virulence were observed [

22].

Among other modern approaches of evaluation plant-pathogen interactions, microscopic techniques are widely used for monitoring pathogenic bacteria infection process. Specifically, confocal microscopy significantly improved plant-pathogen interaction research [

23]. Visualization methods of pathogenic bacteria often include methods based on fluorescence

in situ hybridization (FISH) or use of genetically modified bacteria culture (

eg. green fluorescent protein (GFP) expressing bacteria) [

20,

24,

25].

The aim of this study was to (i) monitored Xcc infection progress via vascular system of root and stem at the initial growth stages after germination of three different cruciferous crops: cabbage, kale and kohlrabi; (ii) quantified infection level and (iii) identified potential significant differences in Xcc dynamics within three Brassica species and their two parts.

2. Materials and Methods

The experiment was conducted at Mendel University in Brno, Faculty of Horticulture, in Lednice, Czech Republic, in 2024 under controlled laboratory conditions. Three species from the Brassicaceae family were chosen as model crops:

- -

Cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata, cultivar ‘Betti’),

- -

Kale (Brassica oleracea var. sabellica, cultivar ‘Scarlet’),

- -

Kohlrabi (Brassica oleracea var. gongylodes, cultivar ‘Ametyst’).

The seeds were sourced from Moravoseed Ltd. (CZ). A portion of the seeds was artificially inoculated with Xcc strain 3811 (WHRI, Horticultural Research International from the University of Warwick, UK) using vacuum according to [

26]. Following inoculation, the seeds were dried at room temperature on filter paper. Both inoculated and non-inoculated seeds (100 seeds per species and treatment) were sown in trays 12 × 15 × 5 cm, filled with perlite substrate (AGRO CS, CZ). The trays were placed in a controlled phytotron (FYTOSCOPE FS-SI-4600, PSI Ltd., CZ) environment with temperatures set at 26 °C, 80% relative humidity, and a light regime of 16 hours of daylight. The light intensity consisted of 110 µmol of white light and 40 µmol of far-red light. Irrigation was done every 2-3 days with tap water, and plants were misted to maintain humidity.

Samples of whole plants, including roots, were collected. Sampling occurred five times: on day 7 after sowing, and then every second day (days 9, 11, 13, and 15). For each sampling, 8 randomly selected plants from both inoculated and non-inoculated groups were collected.

The harvested plants, including roots, were fixed for 6-10 hours in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4 °C. Post-fixation, the samples were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4), dehydrated using an ethanol gradient (25%, 50%, 75% ethanol in PBS), each for 30 minutes at room temperature, and stored at 4 °C until preparation for fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). Root segments, 7–10 mm long, were cut, and cross-sections were made at the base of cotyledon leaves. Further dehydration occurred using 99.8% ethanol, twice for 30 minutes at room temperature. Hybridisation with specific probes for Xanthomonas and non-specific probes for bacteria (EUB338I, EUB338II, EUB338III) was conducted.

The sequences 5´-3´, fluorophores’ wavelengths, and laser lines are listed in

Table 1. In addition to the probes (target region 16S), the hybridization solution contained 0.9 M sodium chloride, 0.01% sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS), 10 mM Tris-HCl, 50% formamide, and deionized water. Hybridization was performed in darkness for 2 hours at 46 °C in an incubator (Boekel Scientific, USA). The post-hybridization solution in both steps contained 20 mM Tris-HCl, 0.01% SDS, 0.028 M NaCl, and 10 µL·mL

−1 of 0.5 M EDTA and was applied for 20 minutes at 48 °C in an incubator. Roots were then washed with sterile distilled water, and 5 pieces of root segments and stem cross-sections were placed on slides and left to dry in the dark at RT for 24 hours. Before observation, the samples were mounted in glycerol and covered with a coverslip.

Laser confocal microscopy was performed using a LSM 800 microscope (Carl Zeiss Jena, Germany). The evaluation of Xcc bacterial incidence was conducted by expressing the percentage presence of bacteria in the microscopically observed samples and recording the incidence numerically. This evaluation was assessed using a scale from 0 to 5 according to [

27], as shown in

Table 2, where 0 indicates no incidence and 5 indicates Xcc bacterial incidence in over 90% area of the observed plant segments.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analysed using the Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric test to compare the median Xcc infection rates between time points (7, 9, 11, 13, and 15 days post-inoculation) at the p-value 0,05. Multiple comparisons of means were performed with a two-tailed test to identify significant differences. The results were displayed in box-and-whisker plots, showing the mean, standard error (SE), and standard deviation (SD). The analyses were done in Statistica version 14 (TIBCO, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Control Group Analysis

Table 3 summarizes the descriptive statistics of Xcc incidence rates in the root and stem tissues of cabbage, kale, and kohlrabi under inoculated and control conditions. Values represent means, medians, and ranges of incidence rates over a 15-day observation period.

In the control (non-inoculated) cabbage group, there was generally no

Xanthomonas campestris pv.

campestris (Xcc) incidence across most samples (

Table 3). In the roots of cabbage, no Xcc was detected (median = 0) on all data. In the stems, Xcc was also not detected (median = 0) except on day 11, where a slight presence was observed (median = 2.0). The possible presence of bacteria was due to the natural infection of the seed endosperm.

In the kale roots, no Xcc was found in most samples (median = 0) except on day 11, where some bacteria were present (median = 2.0). In the stems, the control group showed no incidence of Xcc, with a median value of 0 throughout the sampling period, except on day 11, where some bacteria were present (median = 3.0).

The control group of kohlrabi displayed no Xcc in both roots and stems, with a consistent median value of 0 on all sampling days.

3.2. Inoculated Group Analysis

The presence of Xcc bacteria (

Table 3) in the root system of plants was confirmed through microscopic observation of samples. It was found that both individual bacteria and larger colonies were observed on root samples of all monitored vegetable species. A higher occurrence was noted during the initial observation periods, particularly 7 and 9 days after sowing. In subsequent periods, most species did not show a higher presence of bacteria on the root surface, but rather inside the root tissues. This is related to the fact that inoculation was performed externally on the seed surface, and thus the presence of bacteria on the external tissues was likely temporary, as they subsequently moved and developed inside the plant tissues.

On the other hand, the development of Xcc bacterial colonies in the conductive tissues of the above-ground parts was observed later, as the bacterial colonies gradually developed in connection with plant growth and the formation of vascular bundles. In this case, the occurrence of bacteria in the vascular system varied among the monitored vegetables but was more or less similar in terms of sample collection periods. There was significantly higher presence of colonies inside the vascular bundles than on the root samples.

3.2.1. Cabbage

The presence of Xcc bacteria on the surface of the above-ground parts was not significant, with sporadic occurrences of individual bacteria rather than larger colonies, which is related to the nature and bionomics of this genus, which colonises the internal parts of plant tissues.

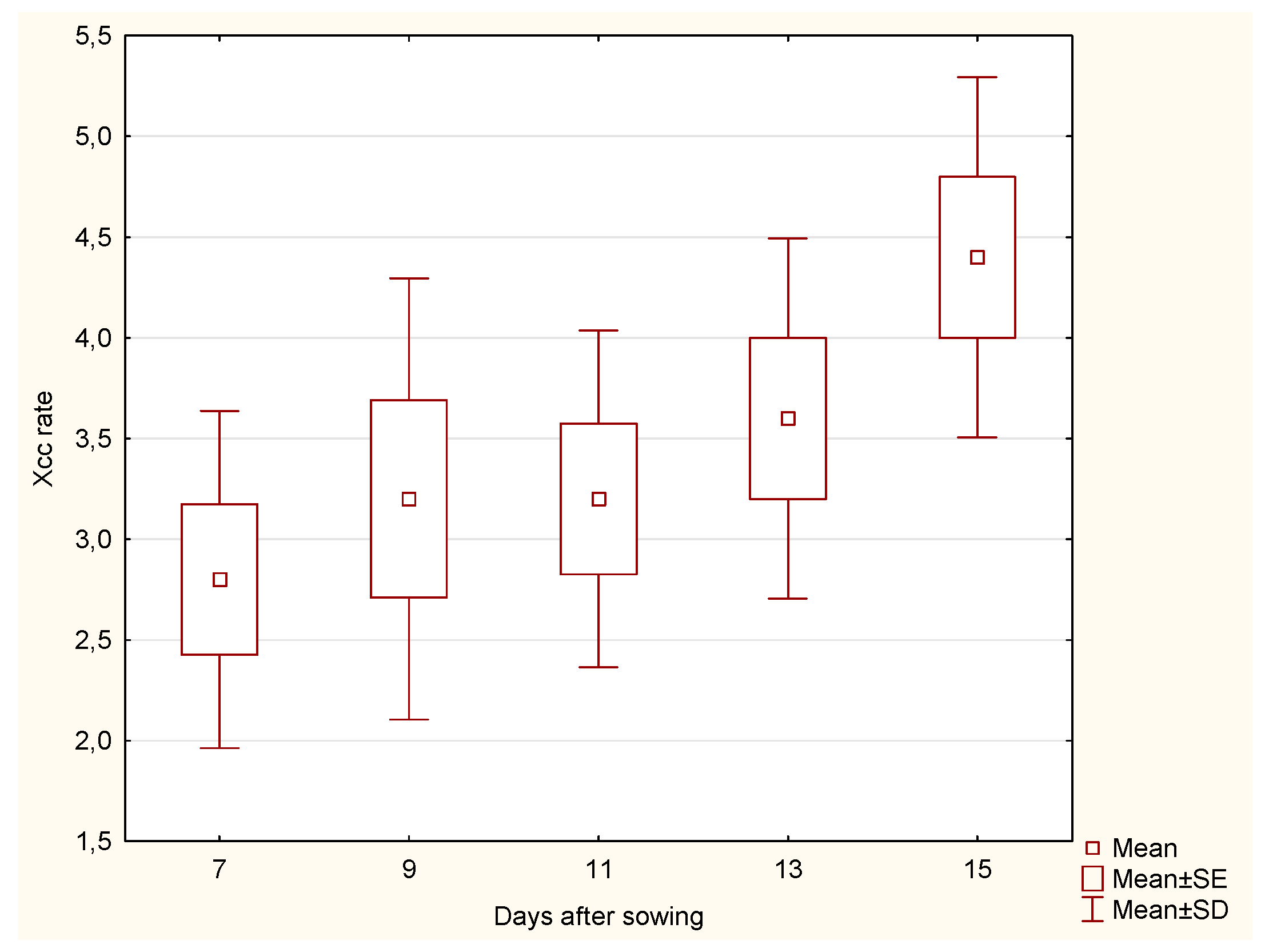

The median Xcc incidence rate in cabbage roots exhibited an increasing trend over time. On day 7, the median was 3.0, rising to 4.0 by day 9 and 5.0 by day 11. However, there was a decline to 3.0 on day 13, followed by a further decrease to 2.0 on day 15. In contrast, the Xcc incidence rate in stems began at a median of 3.0 on day 7, increased to 4.0 by day 9, and remained stable until day 15, with a slight dip to 3.0 observed on day 11.

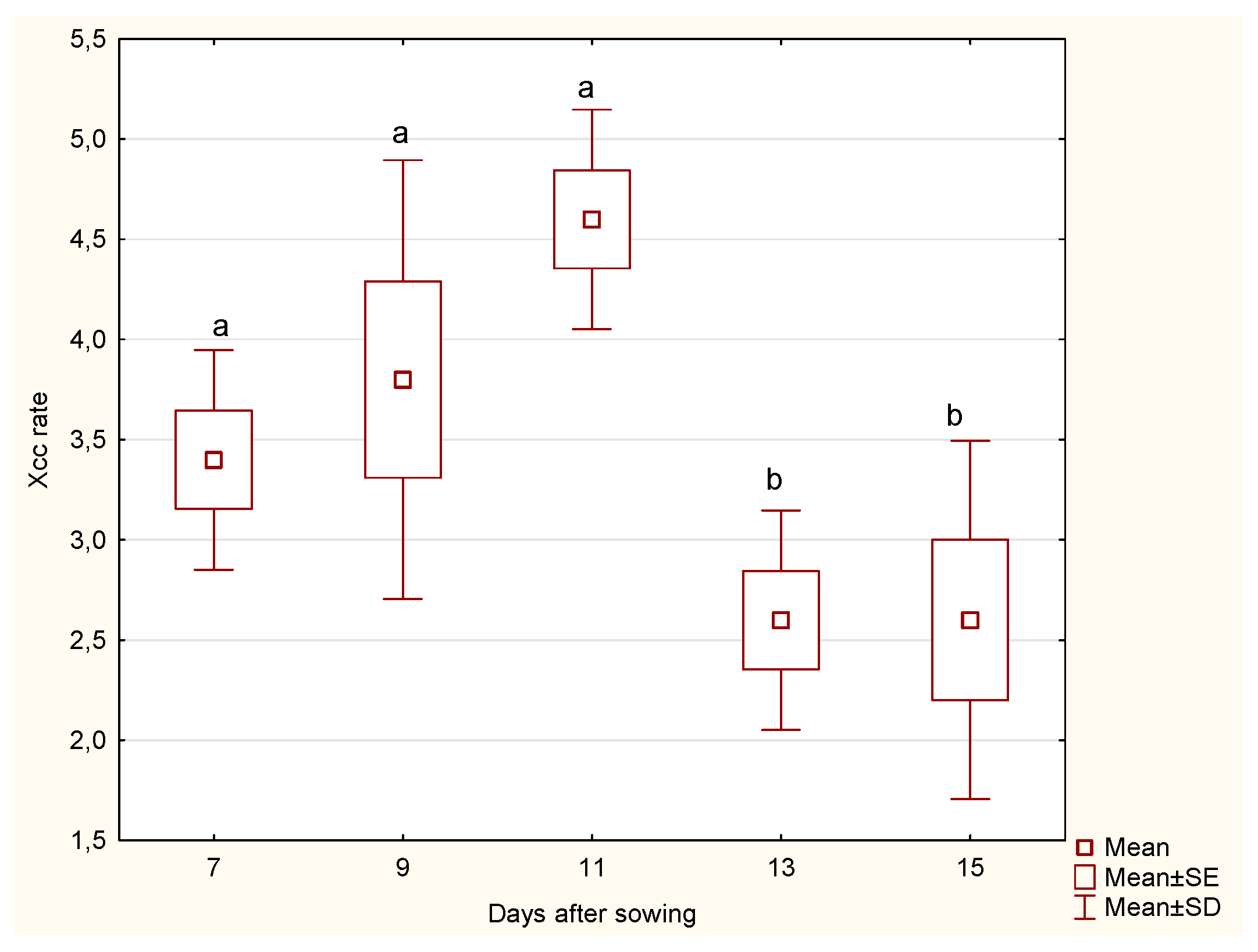

The statistical analysis of cabbage

roots revealed significant differences in the Xcc incidence rate across the days after sowing. Notably, significant differences were observed between days 11 and 13 (p = 0.0325) and between days 11 and 15 (p = 0.0373). These findings indicate that the Xcc incidence rate varies significantly during the later stages of growth, where a marked decline in Xcc incidence rate was recorded (

Figure 1). The significant differences in the Xcc incidence rate for the roots of the cabbage at different days after sowing imply that the root’s susceptibility to Xcc infection changes as the plant develops. This information can be crucial for developing targeted interventions to protect the cabbage at its most vulnerable stages.

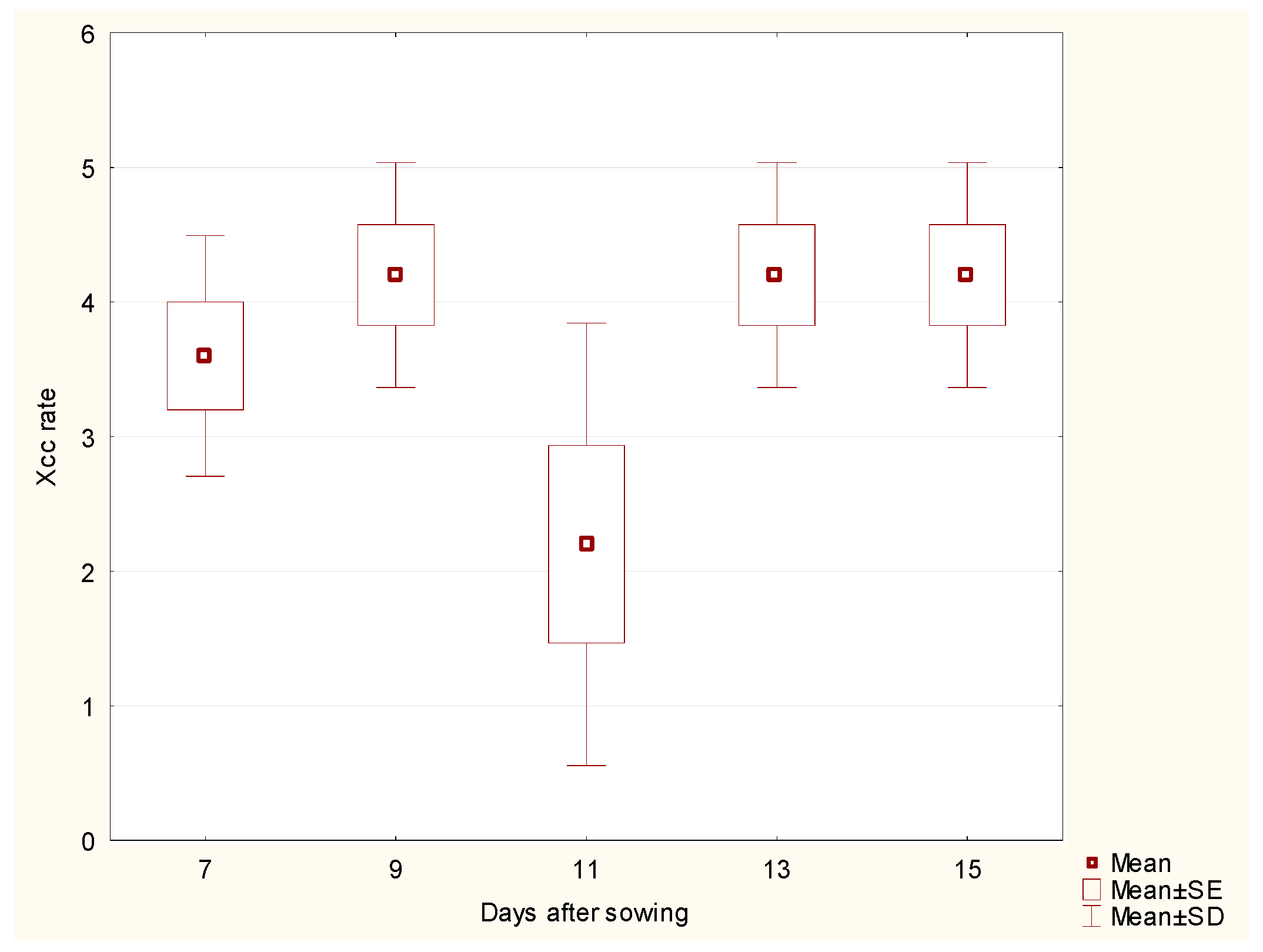

For cabbage

stems, the analysis did not show any significant differences in Xcc incidence rate across the days after sowing, despite a slight drop on day 11 (

Figure 2). This suggests that the Xcc incidence rate for the stem remains relatively stable throughout the observation period, implying a consistent susceptibility to Xcc infection during the entire growth phase.

When comparing the Xcc incidence rate between the cabbage root and stem parts, significant differences were observed on days 11 (p = 0.0163), 13 (p = 0.0216), and 15 (p = 0.0367). These results indicate that the Xcc incidence rate differs between the root and stem parts at specific times, highlighting the variation in response to bacterial spread over time. The cabbage stem appears to be a typical site for bacterial colony development.

The combined analysis emphasises the different responses of the root and stem to Xcc infection over time. Understanding these differences could be crucial for designing more effective disease management strategies that address the specific needs and vulnerabilities of each plant part at different growth stages.

The regression analysis for cabbage roots showed a negative correlation (Xcc incidence rate = 4.94 - 0.14 * Days after sowing) between the Xcc incidence rate and the number of days after sowing, suggesting a slight decrease in Xcc incidence rate over time. Although the p-value of 0.0551 is close to 0.05, it is not statistically significant, implying that the decline in Xcc incidence rate is not strong enough to be conclusive.

For cabbage stems, the regression analysis (Xcc incidence rate = 3.02 + 0.06 * Days after sowing) showed a very weak positive relationship between the Xcc incidence rate and the number of days after sowing, but this relationship was not significant (p = 0.5086), implying the same effect like in root samples.

3.2.2. Kale

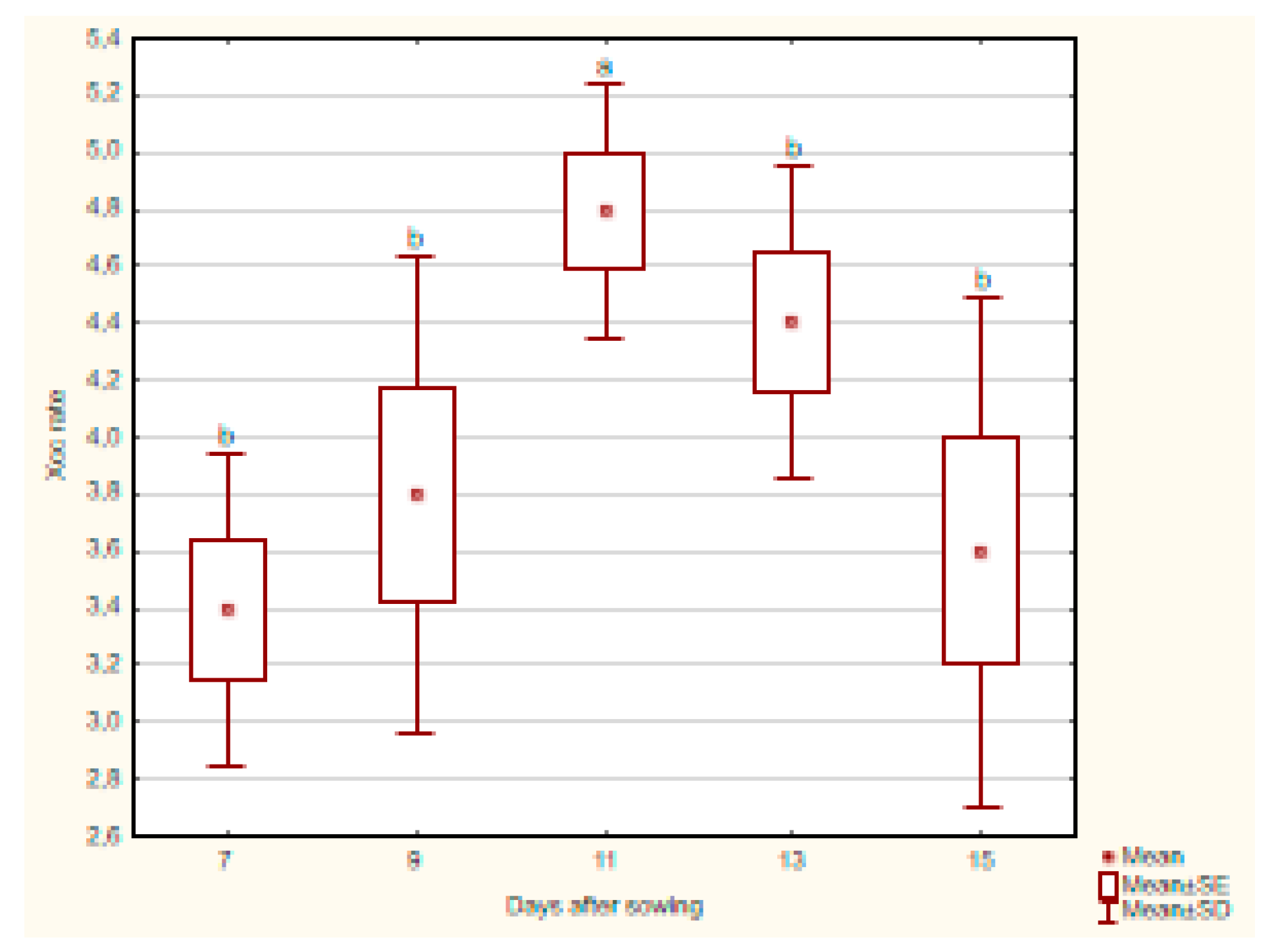

Kale roots showed a consistent increase in Xcc incidence. The median began at 3.0 on day 7, increased to 5.0 by day 9, and stayed at this level until day 11. A decrease was noted on day 13, where the median was 2.0, but it rose again to 4.0 by day 15. The median Xcc incidence rate in kale stems was 4.0 on day 7 and remained stable until day 15, reaching 5.0.

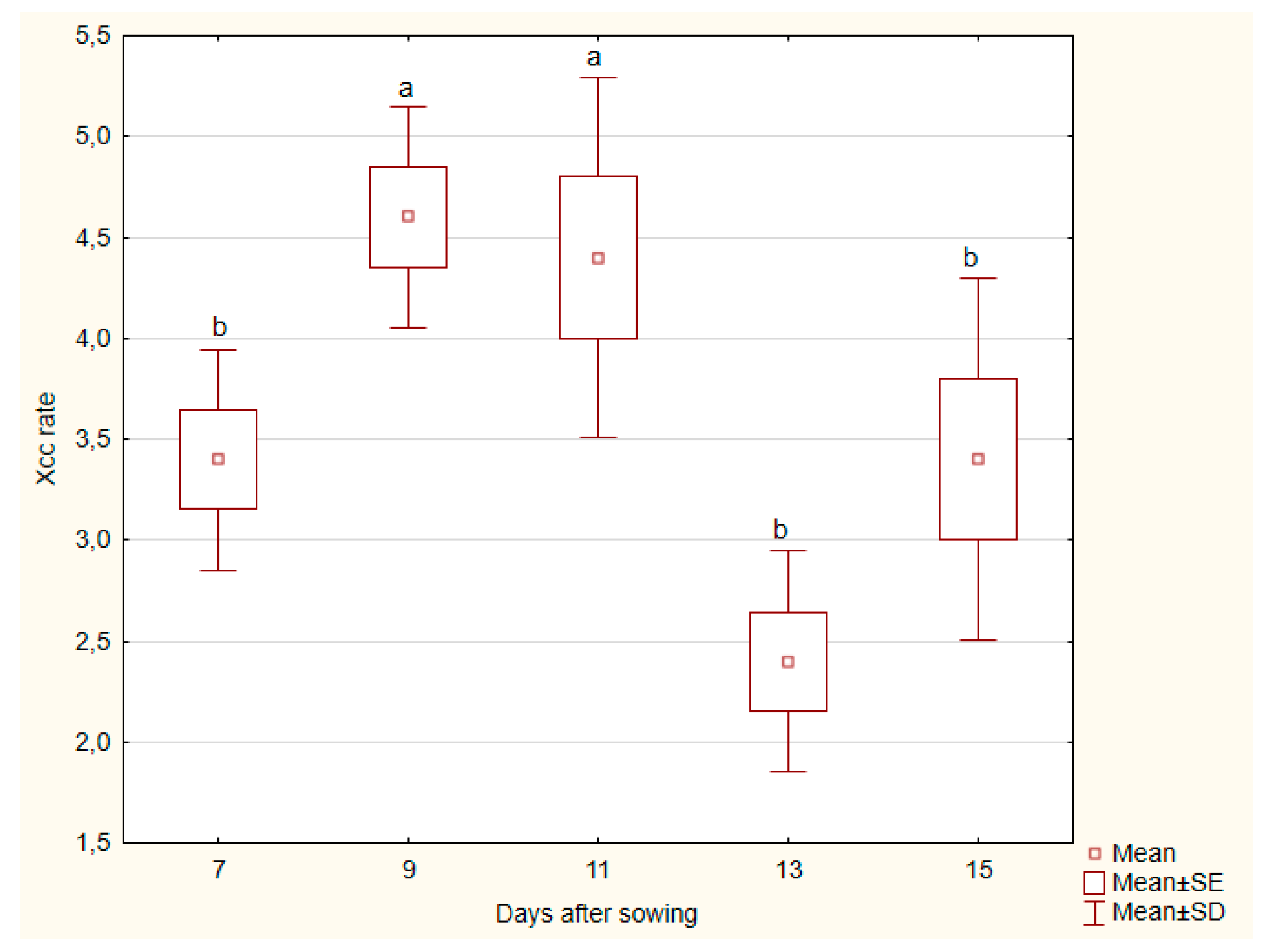

The Kruskal-Wallis analysis for kale

roots revealed a statistically significant difference in Xcc incidence rate across the different days after sowing (p = 0.0055). This indicates that the Xcc incidence rate in the roots of the kale plant is likely changing significantly over time. Pairwise comparisons showed significant differences between days 9 and 11 (p = 0.0127) and between days 11 and 13 (p = 0.0373), with day 13 showing a higher Xcc incidence rate (

Figure 3).

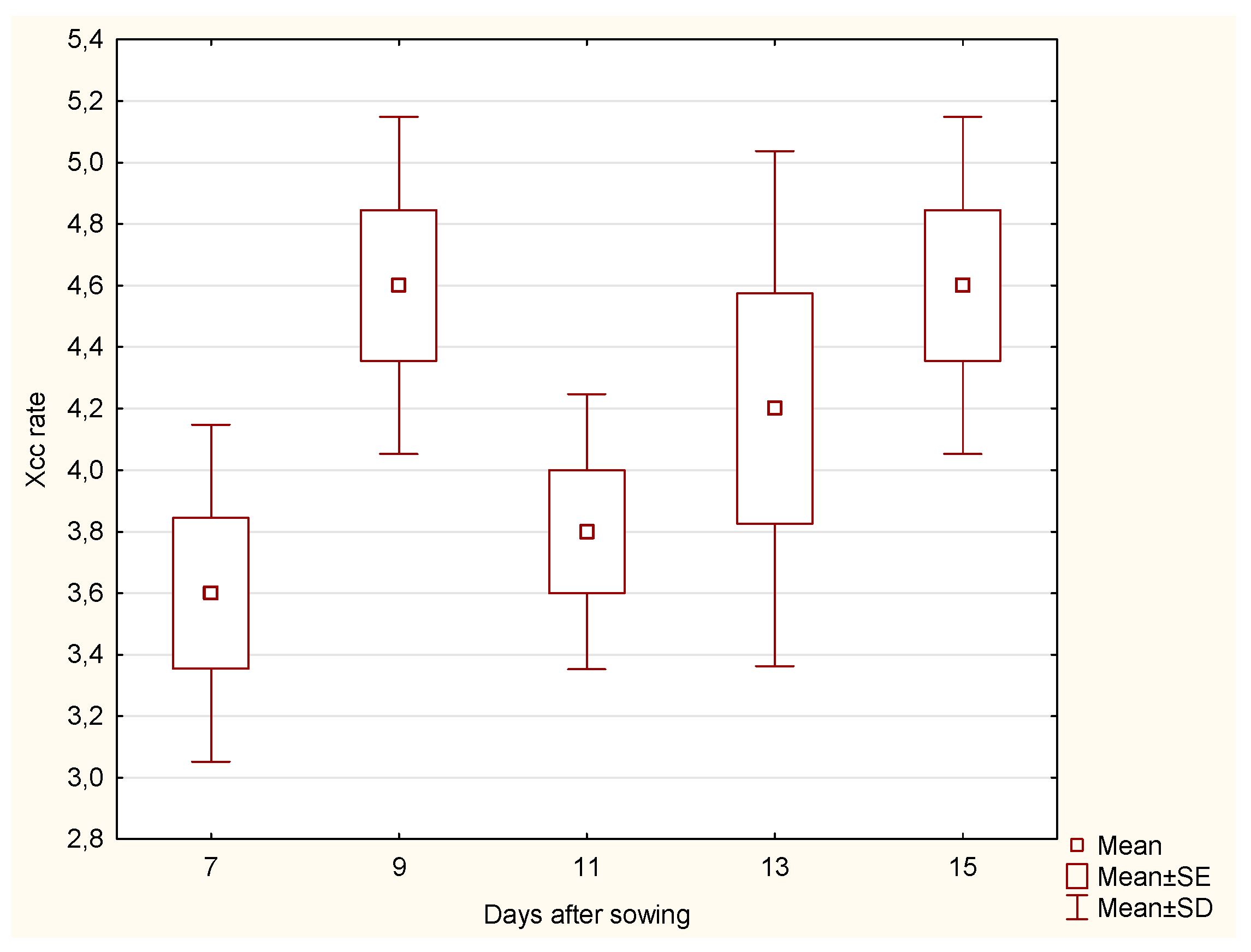

In contrast, the

stem part showed no significant difference in Xcc incidence rate (

Figure 4) across the days after sowing, suggesting that the Xcc incidence rate in the stem remained relatively stable over time

The aggregate analysis comparing root and stem across days revealed significant differences at specific time points. On day 13, there was a significant difference in Xcc incidence rate between root and stem (p = 0.0163), with the roots having a higher Xcc rate. Similarly, on day 15, the root samples exhibited a significantly higher Xcc rate than the stem (p = 0.0472).

Regression analysis of kale root samples (Xcc incidence rate = 4.85 - 0.11 * Days after sowing) showed no significant relationship between days after sowing and Xcc incidence rate (p = 0.1362), indicating no meaningful trend. The regression equation for kale stems (Xcc incidence rate = 3.28 + 0.08 * Days after sowing) similarly showed no significant relationship.

3.2.3. Kohlrabi

The Xcc incidence rate in kohlrabi roots remained relatively stable, with the median fluctuating between 3.0 and 5.0. On day 7, the median was 3.0 and remained steady until day 13, after which it increased to 5.0. The Xcc incidence rate in kohlrabi stems followed a similar pattern, with a median of 3.0 on day 7, rising to 4.0 on day 9, and reaching 5.0 on day 11, before decreasing to 3.0 again on day 15.

The statistical evaluation of kohlrabi root samples showed (

Figure 5) no significant difference in Xcc incidence rate across the days after sowing, indicating that the Xcc incidence rate in kohlrabi roots remained consistent over time, despite a non-significant increase.

In the stem part, a statistically significant difference in Xcc incidence rate was observed across the days after sowing (p = 0.0372). Pairwise comparisons showed a significant difference between days 7 and 11 (p = 0.0109), with day 11 showing a higher Xcc incidence rate (

Figure 6).

The aggregate analysis comparing roots and stems across days revealed a significant difference on day 11 (p = 0.0163), with the higher Xcc incidence rate in stems, while no significant differences were detected on other days.

Regression analysis for kohlrabi roots yielded the equation Xcc incidence rate = 1.46 + 0.18 * Days after sowing, showing a weak positive linear relationship (p = 0.0080). However, the weak correlation (r² = 0.2682) indicates that this trend only explains a small proportion of the variation in Xcc incidence rate. In the stem samples, the regression equation Xcc incidence rate = 3.45 + 0.05 * Days after sowing showed a very weak positive relationship, but this was not statistically significant (p = 0.3979).

3.3. Comparison of Species

In general, kale exhibited the highest median Xcc incidence rates throughout the observation period, particularly in the roots, where the incidence reached 5.0 by day 9 and remained stable until day 11. In contrast, cabbage and kohlrabi showed more fluctuations, with cabbage experiencing a significant drop in infection on day 13.

The inoculation impact on stems was more consistent across species, with kale again showing the highest levels of Xcc incidence rate, particularly from day 9 onwards, where the median value remained stable at 5.0. Cabbage stems displayed slightly lower infection levels, while kohlrabi exhibited the lowest and most fluctuating rates, especially after day 13.

In summary, the results indicate a clear progress of Xcc incidence rate in all three Brassica species, with kale displaying the most significant and consistent infection rates. The control group remained unaffected by Xcc, with only minor traces detected in a few samples, suggesting minimal natural contamination.

3.4. Microscopic Observations

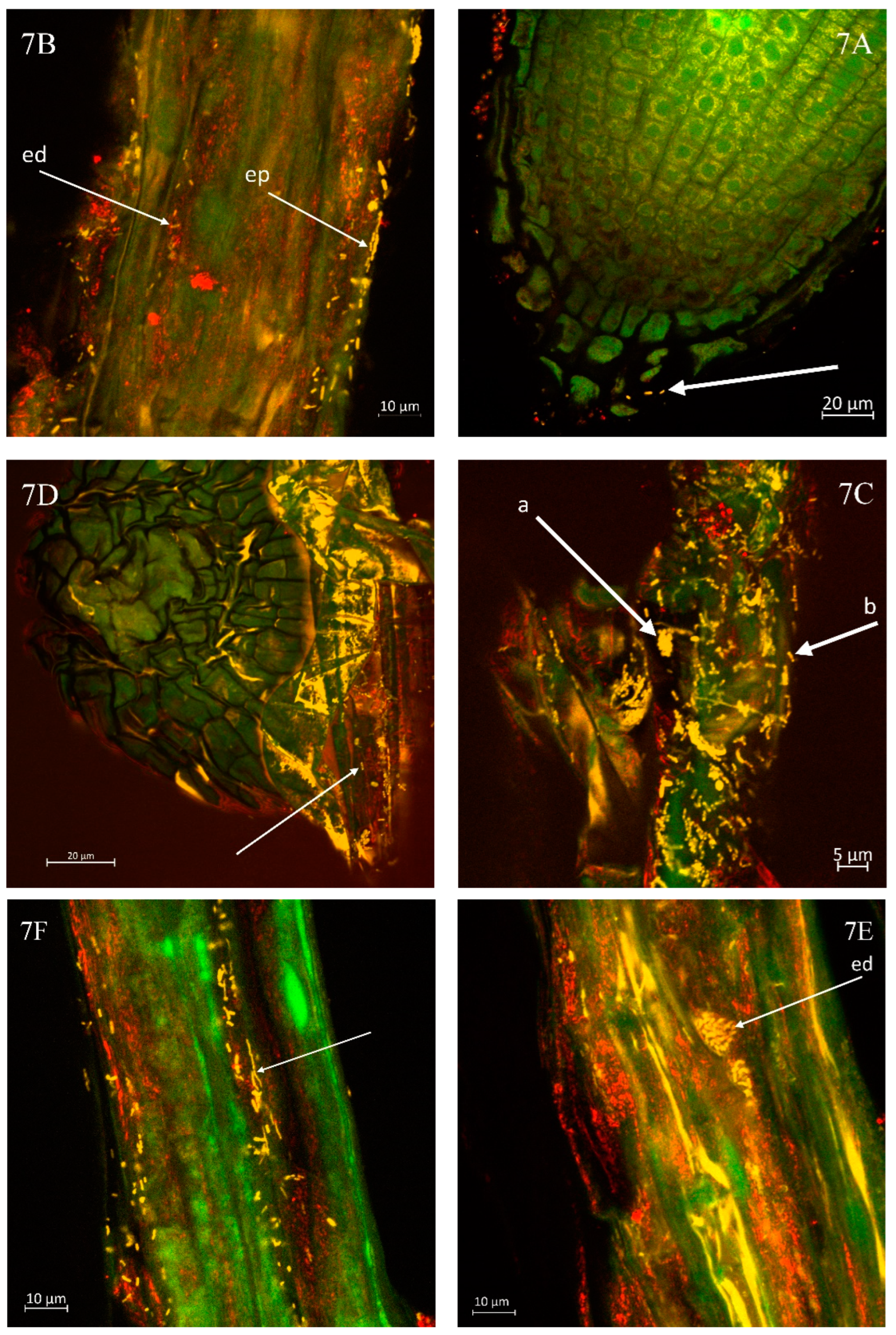

3.4.1. Roots

Evidence shows that contact between the host root and Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris can occur even at this early developmental stage as visible in the root radicula of the cabbage (

Figure 7A). A notable presence of several Xcc bacteria is observed in this region of the root tip.

Figure 7B illustrates the abundant colonisation of Xcc on the kohlrabi root. Their presence is detectable within both the epidermis (ep) and the endodermis (ed) during the microscopic observation of the root surface layers. The inner tissue of the cabbage root, as shown in

Figure 7C, reveals a significantly high density of Xcc bacteria. Smaller colonies (a) and individual bacterial cells (b) are distinctly visible throughout the examined sample area.

Figure 7D indicates the presence of Xcc bacteria within the epidermis of the cabbage root, suggesting that the developing adventitious root may become infected by these bacteria right from the onset of its growth. The surface occurrence of Xcc is likely linked to prior inoculation and the presence of bacterial colonies within the growth substrate.

Similarly, in the case of kale, a high occurrence of Xcc was observed on the roots, as shown in Fig. 7E, which highlights the presence of Xcc bacterial colonies. Fig. 7F illustrates that the amount of bacteria adhered to the rhizodermis was substantial. The bacteria frequently covered the entire observed root sample continuously.

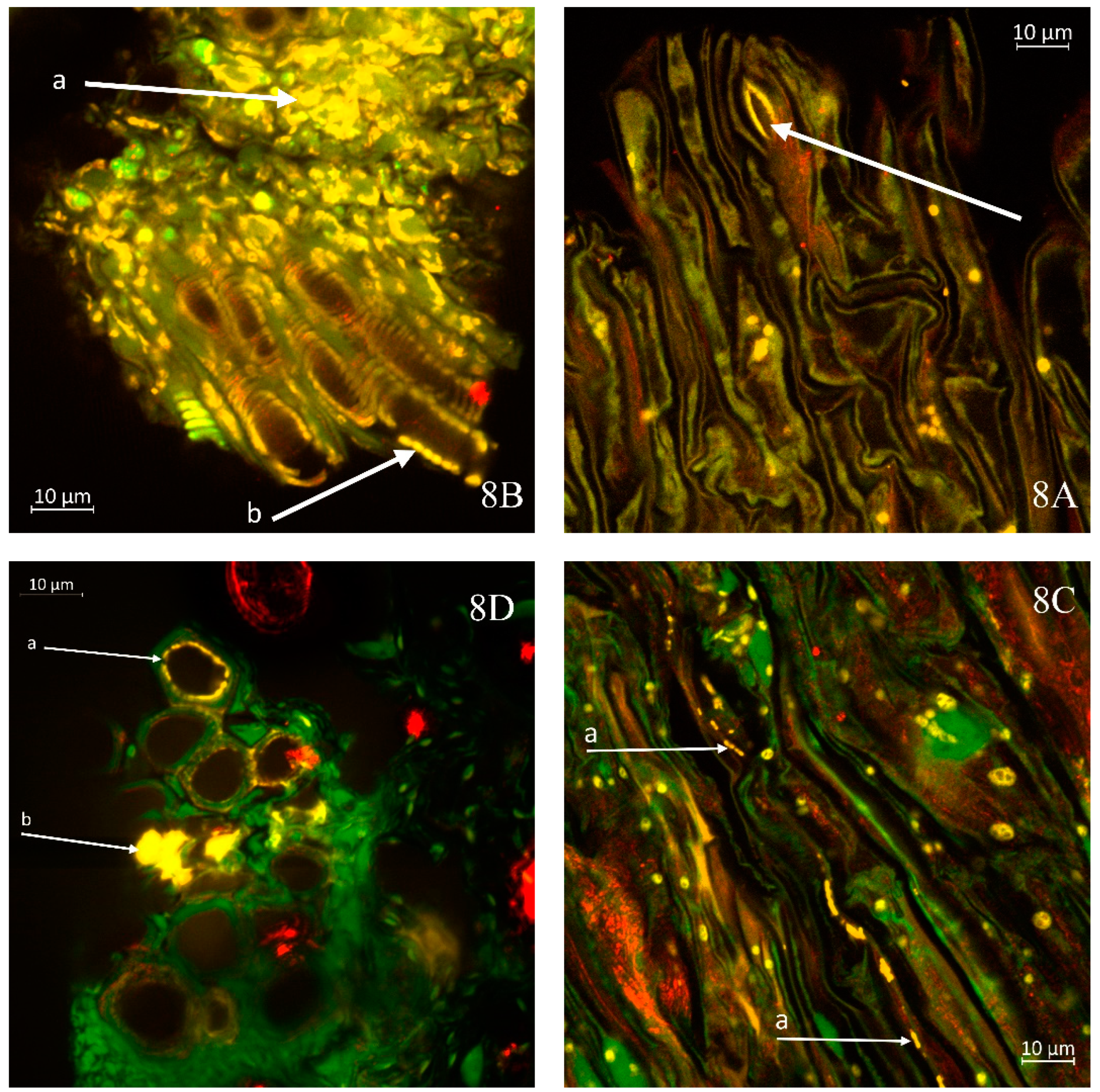

3.4.2. Stems

Figure 8A highlights regions with a low occurrence of stomata, such as the junction between the cabbage stem and leaf petiole, where yellow-highlighted areas of Xcc presence can be observed within the stomatal openings. This observation is related to one of the pathways through which the bacteria penetrate the plant.

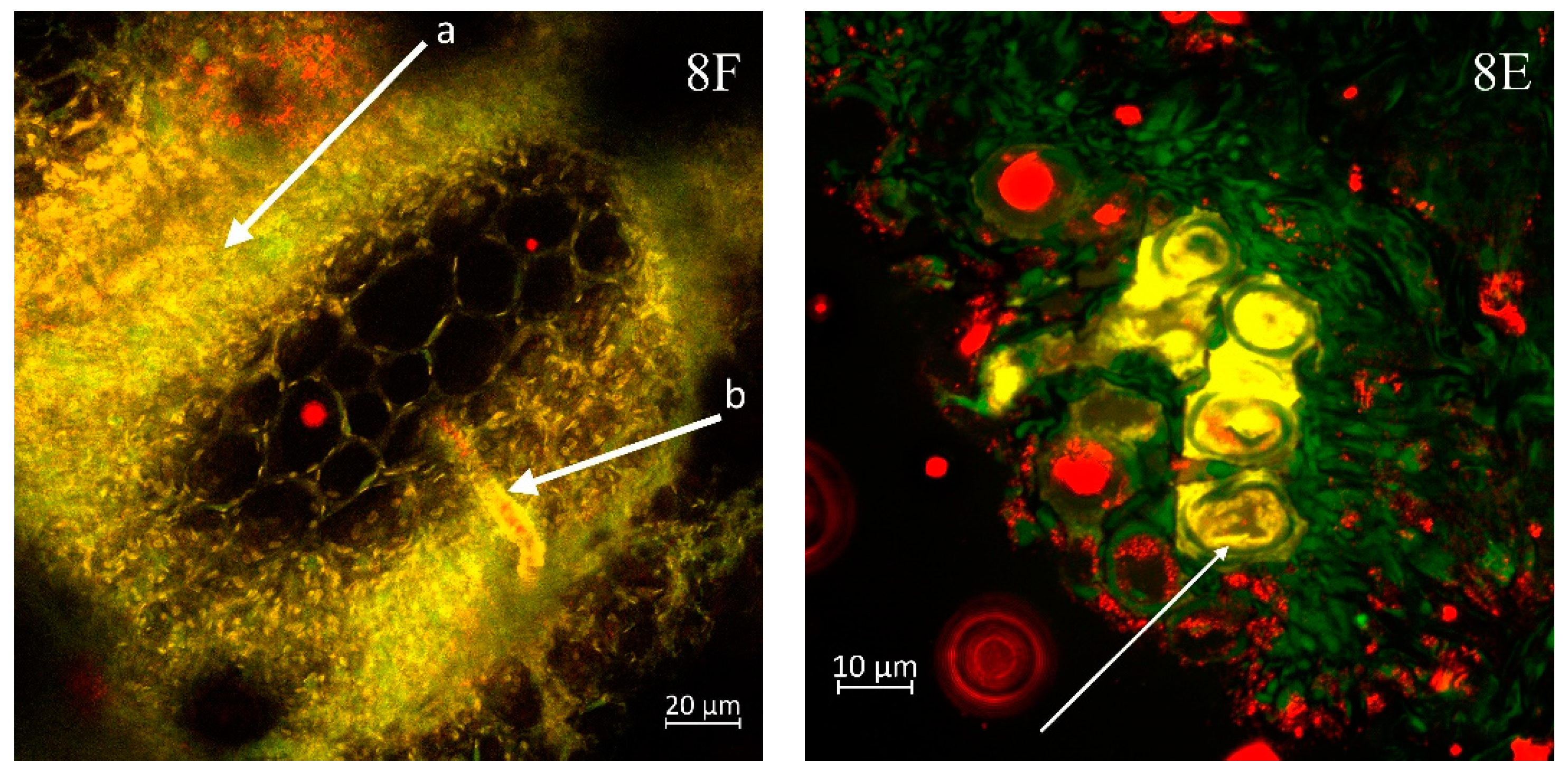

A significant presence of Xcc in the transverse section of the kale stem is depicted in

Figure 8B. Highly abundant colonies of Xcc (a) form continuous yellow regions, which are also observable in the longitudinal section of the xylem, particularly in areas where the edges of xylem vessels appear light (b). In

Figure 8C, a longitudinal section of the cabbage stem reveals visible lines of Xcc bacteria (a) migrating within vessel members.

Figure 8D presents an emerging colony of Xcc (a) on the inner wall of the xylem in kohlrabi. As the colony develops, it progressively obstructs the vascular bundle, transitioning to a state illustrated lower in the figure (b), where fully yellow areas of the colonies are apparent. This condition symptomatically leads to wilting of the affected plant segment. The further progression of this condition is clearly demonstrated in

Figure 8E, where the xylem bundles of the cabbage are entirely populated by Xcc bacteria, resulting in a cessation of their essential role in supplying the plant with water and nutrients.

In sample of kohlrabi with an exceedingly high bacterial presence, numerous bacterial cells are observed not only in the xylem but also in the phloem (a), as shown in

Figure 8F. The released xylem cells exhibit a continuous presence of bacteria on the yellow-highlighted walls (b).

4. Discussion

The results of this study indicate that the progression of Xcc infection differs across the three Brassica species, as well as between the root and stem tissues. Initially, higher bacterial presence was observed on the root surfaces, particularly in the first week after sowing. This can be attributed to the external inoculation of seeds, which led to temporary colonization on the root surfaces. However, over time, Xcc bacteria moved internally into the root tissues, where the infection persisted. In contrast, the stems exhibited slower development of bacterial colonies, as Xcc spread gradually into the vascular tissues, likely in response to plant growth and the formation of vascular bundles.

The temporal and spatial differences in bacterial colonization observed in the roots and stems of cabbage, kale, and kohlrabi reflect not only the physiological distinctions between these plant parts but also highlight the adaptive strategies of Xcc in establishing systemic infections. These results suggest that the internal movement of bacteria, particularly into the vascular tissues, is critical for disease development, with roots serving as an initial colonisation point and stems becoming a later target as the infection progresses. Infections start at a specific site and increase or change as time progresses, like in our study where Xcc initially colonized the root surfaces before moving internally. Similar development of Xcc has been observed in study of [

20] and studies involving various pathogens like

Erwinia amylovora or

Ralstonia spp. [

28,

29].

Regarding the differences in bacterial colonization within three selected vegetable species according to results of this study, higher bacterial colonization was observed in kale compared to cabbage or kohlrabi. Several research studies of black rot resistance genome sources in Brassica species confirmed race specific resistance in various Brassica species (eg.

B. juncea, B. napus, B. rapa) [

3,

21]. Generally, the species from

Brassica oleracea group (including all three species evaluated in this study) belong to the most vulnerable crops to most virulent races 1 and 4 of Xcc causing black rot, however some resistant varieties already exist in this group as well [

30,

31,

32]. Host-isolate relationship, expressed as higher appearance of symptoms caused by natural Xcc isolate obtain from the given crop, was observed in kale, kohlrabi and cauliflower [

22]. Interestingly, no host-isolate relationship was observed for the natural isolate from cabbage caused infection similarly in all six

Brassica oleracea vegetable crops. The isolate used in this study (HRI-W 3811), originally isolated from cabbage, caused bacterial infection in all three studied vegetable crops, confirming no host-isolate relationship. Contrary, to results of our study, no significant differences were observed in symptoms appearance on six vegetable crops artificially infected by Xcc isolate obtained from cabbage in the study of [

22].

Our study demonstrates the most rapid development of Xcc infection levels in kale. This can be linked to the higher sensitivity of this particular vegetable species and/or the cultivar used. Many studies, including ours [

15,

21], have documented the importance of cultivar-level sensitivity to Xcc. Fluctuations in the Xcc incidence rate in cabbage and kohlrabi plants could be influenced by the different speeds of plant development. More intense growth may limit the severity of infection.

The slight infection observed in the control variant is likely due to latent seed infection. Xcc is known for being seedborne, meaning the pathogen can remain inactive inside the seeds and only manifest under favourable conditions, such as during plant growth. Xcc can survive in seeds without visible symptoms and become active when environmental conditions like moisture and temperature promote its growth. Seed contamination with Xcc is considered the primary source of field infections, which is why seed disinfection methods are recommended to minimize the risk of latent infection. This phenomenon has been repeatedly confirmed in various Brassicaceae species, where infected seeds lead to the spread of the pathogen into plant tissues early in the growth stages [

33,

34,

35].

The findings from the microscopic analysis of cabbage and kohlrabi roots and stems provide significant insights into the early interactions between Xcc and host plant tissues. Observations indicate that even at the radicle stage Xcc establishes contact with the host root, suggesting that infection can initiate early in root development. Rapid development of *Xcc* bacterial presence was also reported by [

26], where a short-term experiment lasting a few weeks demonstrated the substantial impact of the bacteria on the health status of cabbage seedlings. This also aligns with previous studies that have demonstrated early colonisation of roots by pathogens, emphasizing the importance of understanding these interactions for effective disease management [

36].

The notable presence of Xcc in both the epidermis and endodermis of kohlrabi roots reinforces the notion that bacterial colonisation occurs not only superficially but also within deeper tissues. This intracellular colonisation may enhance the pathogen's ability to evade initial plant defence mechanisms and highlights a potential route for systemic infection, corroborating findings from similar studies that highlighted the role of bacterial movement through plant tissues [

37].

The high density of Xcc observed in the inner tissues of cabbage roots indicates a significant proliferation of the pathogen. Smaller colonies and individual bacteria are clearly visible, suggesting active multiplication within the host tissue. Such bacterial densities can lead to severe pathogenesis, as previously reported by [

38], which noted that relatively soon overwhelming bacterial presence could lead to tissue necrosis and plant wilting. The findings in this study substantiate these conclusions by demonstrating that high bacterial concentrations hinder the physiological functions of vascular tissues.

Further observations suggest that Xcc can infect adventitious roots from the outset of their development. This early-stage infection could have serious implications for plant health and productivity, especially if not detected early. From this perspective, appropriate protective measures should include novel treatment applications, such as nanoparticles [

16] and bacteriophages [

17], implemented during the very early stages of canopy establishment.

In the stem parts the findings illustrate the various pathways of Xcc entry. The presence of Xcc within stomatal openings and the extensive colonisation observed in the transverse and longitudinal sections of the kale stem indicate that the bacteria adeptly exploit natural openings to infiltrate vascular tissues. The continuous colonisation leading to the occlusion of xylem vessels, culminating in the wilting of plant segments, aligns with literature documenting the devastating effects of Xcc infections on crop water and nutrient transport systems [

38].

The observation of bacterial cells in both xylem and phloem of kohlrabi underscores the ability of Xcc to navigate through critical vascular systems. This dual presence could facilitate widespread systemic infection throughout the plant, corroborating previous findings that highlight the extensive damage caused by Xcc in susceptible crops [

39].

5. Conclusions

This study provides valuable insights into the infection dynamics of Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris in Brassica species, focusing on cabbage, kale, and kohlrabi. The development of Xcc infection varied between plant species and tissues, with roots generally showing earlier colonisation due to initial seed inoculation. Root infection progressed internally after an initial surface colonisation, while stem infection developed more gradually, aligning with the formation of vascular tissues. Kale exhibited the highest incidence rates, particularly in the roots, compared to cabbage and kohlrabi, which demonstrated more fluctuations.

Microscopic analysis revealed the presence of Xcc in both the epidermis and deeper root tissues, particularly the endodermis, suggesting early intracellular colonisation. This highlights ability of Xcc to evade plant defences and spread systemically, contributing to disease development. The high bacterial density observed in cabbage roots and the colonisation of both xylem and phloem in kohlrabi emphasize the pathogen’s ability to disrupt vascular functions, leading to tissue necrosis and plant wilting.

The study further identified significant differences in infection dynamics between the root and stem tissues, with the roots serving as the initial colonisation point and stems becoming a target later. The observed infection in adventitious roots underscores the risk of early-stage infections, while stem colonisation through natural openings like stomata demonstrates Xcc adaptability. These findings enhance our understanding of Xcc's infection strategies and offer critical insights for improving disease management in Brassica crops.

The onset of Xcc infection is rapid, regardless of the vegetable species. Under conditions optimal for the pathogen, significant plant damage can occur as early as one week post-infection. Therefore, preventive measures play a crucial role in managing Xcc, and available direct protection methods should be implemented at the earliest opportunity. Effective preventive measures include seed treatment as a tool for protecting crops in their early stages. Direct protection approaches may involve the exploitation of bacteriophages and the general use of biocontrol methods.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.P. and L.N.R.; methodology, R.P, L.N.R., V.F, J.P.; validation A.S.; statistical analysis, R.P., A.S.; investigation, V.F.; data curation, V.F.; writing—original draft preparation, R.P., L.N.R., V.F., J.P.; writing—review and editing, R.P., A.S., J.P.; project administration, R.P.; funding acquisition, R.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was carried out under the grant of Ministry of Agriculture QK22010031 „Use of innovative potential of nanotechnology to enhance the rentability of selected areas of agricultural production. This research was also supported by the project CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/16_017/0002334 Research Infrastructure for Young Scientists, co-financed by Operational Programme Research, Development and Education EU and Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alvarez, A.M. Black Rot of Crucifers. In Mechanisms of Resistance to Plant Diseases, Slusarenko, A.J., Fraser, R.S.S., van Loon, L.C., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2000; pp. 21–52. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.P.; Vorhölter, F.J.; Potnis, N.; Jones, J.B.; Van Sluys, M.A.; Bogdanove, A.J.; Dow, J.M. Pathogenomics of Xanthomonas: understanding bacterium-plant interactions. Nat Rev Microbiol 2011, 9, 344–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicente, J.G.; Holub, E.B. Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris (cause of black rot of crucifers) in the genomic era is still a worldwide threat to brassica crops. Mol Plant Pathol 2013, 14, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food; Agriculture Organization of the United, N. FAOSTAT Statistical Database. 2024.

- Holtappels, D.; Fortuna, K.J.; Moons, L.; Broeckaert, N.; Bäcker, L.E.; Venneman, S.; Rombouts, S.; Lippens, L.; Baeyen, S.; Pollet, S.; et al. The potential of bacteriophages to control Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris at different stages of disease development. Microb Biotechnol 2022, 15, 1762–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, W.; Jia, Y.; Ren, S.X.; He, Y.Q.; Feng, J.X.; Lu, L.F.; Sun, Q.; Ying, G.; Tang, D.J.; Tang, H.; et al. Comparative and functional genomic analyses of the pathogenicity of phytopathogen Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris. Genome Res 2005, 15, 757–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Bernabé, L.; Madloo, P.; Rodríguez, V.M.; Francisco, M.; Soengas, P. Dissecting quantitative resistance to Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris in leaves of Brassica oleracea by QTL analysis. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.C.; Silva Júnior, T.A.F.; Soman, J.M.; Tomasini, T.D.; Sartori, M.M.P.; Maringoni, A.C. Survival of Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris in the phyllosphere and rhizosphere of weeds. Plant Pathology 2017, 66, 1517–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Lv, J.; Xie, B.; Luo, S.; Wang, S.; Zhang, B.; Li, Z.; Yue, Z.; et al. Physical, chemical, and biological control of black rot of brassicaceae vegetables: A review. Front Microbiol 2022, 13, 1023826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.Q.; Potnis, N.; Dow, M.; Vorhölter, F.J.; He, Y.Q.; Becker, A.; Teper, D.; Li, Y.; Wang, N.; Bleris, L.; et al. Mechanistic insights into host adaptation, virulence and epidemiology of the phytopathogen Xanthomonas. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2020, 44, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dia, N.C.; Morinière, L.; Cottyn, B.; Bernal, E.; Jacobs, Jonathan M. ; Koebnik, R.; Osdaghi, E.; Potnis, N.; Pothier, Joël F. Xanthomonas hortorum – beyond gardens: Current taxonomy, genomics, and virulence repertoires. Molecular Plant Pathology 2022, 23, 597–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daughtrey, M.L.; Benson, D.M. Principles of plant health management for ornamental plants. Annu Rev Phytopathol 2005, 43, 141–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manulis, S.; Valinsky, L.; Lichter, A.; Gabriel, D.W. Sensitive and specific detection of Xanthomonas campestris pv. pelargonii with DNA primers and probes identified by random amplified polymorphic DNA analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol 1994, 60, 4094–4099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Wolf, J.M.; Van Der Zouwen, P.S. Colonization of Cauliflower Blossom (Brassica oleracea) by Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris, via Flies (Calliphora vomitoria) Can Result in Seed Infestation. Journal of Phytopathology 2010, 158, 726–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pečenka, J.; Bytešníková, Z.; Kiss, T.; Peňázová, E.; Baránek, M.; Eichmeier, A.; Tekielska, D.; Richtera, L.; Pokluda, R.; Adam, V. Silver nanoparticles eliminate Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris in cabbage seeds more efficiently than hot water treatment. Materials Today Communications 2021, 27, 102284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, P.; Lema, M.; Francisco, M.; Soengas, P.; Cartea, M.E. In vivo and in vitro effects of secondary metabolites against Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris. Molecules 2013, 18, 11131–11143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaianni, M.; Paris, D.; Woo, S.L.; Fulgione, A.; Rigano, M.M.; Parrilli, E.; Tutino, M.L.; Marra, R.; Manganiello, G.; Casillo, A.; et al. Plant Dynamic Metabolic Response to Bacteriophage Treatment After Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris Infection. Front Microbiol 2020, 11, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramoni, S.; Pandey, A.; Vishnu Priya, M.R.; Patel, H.K.; Sonti, R.V. The ColRS system of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae is required for virulence and growth in iron-limiting conditions. Mol Plant Pathol 2012, 13, 690–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Godínez, L.J.; Aguirre-Noyola, J.L.; Martínez-Romero, E.; Arteaga-Garibay, R.I.; Ireta-Moreno, J.; Ruvalcaba-Gómez, J.M. A Look at Plant-Growth-Promoting Bacteria. Plants (Basel) 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akimoto-Tomiyama, C.; Furutani, A.; Ochiai, H. Real time live imaging of phytopathogenic bacteria Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris MAFF106712 in 'plant sweet home'. PLoS One 2014, 9, e94386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.D.; Conway, J.; Roberts, S.J.; Astley, D.; Vicente, J.G. Sources and Origin of Resistance to Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris in Brassica Genomes. Phytopathology 2002, 92, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popović, T.; Mitrović, P.; Jelušić, A.; Dimkić, I.; Marjanović-Jeromela, A.; Nikolić, I.; Stanković, S. Genetic diversity and virulence of Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris isolates from Brassica napus and six Brassica oleracea crops in Serbia. Plant Pathology 2019, 68, 1448–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardham, A.R. Confocal Microscopy in Plant–Pathogen Interactions. In Plant Fungal Pathogens: Methods and Protocols, Bolton, M.D., Thomma, B.P.H.J., Eds.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, 2012; pp. 295–309. [Google Scholar]

- Peredo, E.L.; Simmons, S.L. Leaf-FISH: Microscale Imaging of Bacterial Taxa on Phyllosphere. Frontiers in Microbiology 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; McTavish, C.; Turechek, W.W. Colonization and Movement of Xanthomonas fragariae in Strawberry Tissues. Phytopathology® 2018, 108, 681–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, S.J.; Brough, J.; Hunter, P.J. Modelling the spread of Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris in module-raised brassica transplants. Plant Pathology 2007, 56, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcón, C.; Cuenca, G. Arbuscular mycorrhizas in coastal sand dunes of the Paraguaná Peninsula, Venezuela. Mycorrhiza 2005, 16, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Huntley, R.B.; Zeng, Q.; Steven, B. Temporal and spatial dynamics in the apple flower microbiome in the presence of the phytopathogen Erwinia amylovora. The ISME Journal 2021, 15, 318–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A.P.; Jesus Junior, W.C.; Zauza, E.A.V.; Coutinho, M.P.; dos Anjos, B.B.; Moraes, W.B. Spatiotemporal dynamics of bacterial wilt in Eucalyptus. Forest Pathology 2023, 53, e12798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, S.F.; Surendran, A.; Grant, M.; Lillywhite, R. The current status, challenges, and future perspectives for managing diseases of brassicas. Frontiers in Microbiology 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, X.-G.; Branca, F.; Zhao, Z.-Q.; Wang, J.-S.; Yu, H.-F.; Shen, Y.-S.; Gu, H.-H. Identification of Black Rot Resistance in a Wild Brassica Species and Its Potential Transferability to Cauliflower. Agronomy 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Álvarez, C.; Francisco, M.; Cartea, M.E.; Fernández, J.C.; Soengas, P. The growth-immunity tradeoff in Brassica oleracea-Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris pathosystem. Plant Cell Environ 2023, 46, 2985–2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Wolf, J.M.; van der Zouwen, P.S.; van der Heijden, L. Flower infection of Brassica oleracea with Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris results in high levels of seed infection. European Journal of Plant Pathology 2013, 136, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanna, M.; Gilardi, G.; Gullino, M.L.; Mezzalama, M. Evaluation of physical and chemical disinfection methods of Brassica oleracea seeds naturally contaminated with Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris. Journal of Plant Diseases and Protection 2022, 129, 1145–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubrow, Z.E.; Bogdanove, A.J. Genomic insights advance the fight against black rot of crucifers. Journal of General Plant Pathology 2021, 87, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Y.; Fujikawa, T.; Takikawa, Y. Detection and identification of Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris and pv. raphani by multiplex polymerase chain reaction using specific primers. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2021, 105, 1991–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Carvalhais, L.C.; Crawford, M.; Singh, E.; Dennis, P.G.; Pieterse, C.M.J.; Schenk, P.M. Inner Plant Values: Diversity, Colonization and Benefits from Endophytic Bacteria. Frontiers in Microbiology 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, J.; Genin, S.; Magori, S.; Citovsky, V.; Sriariyanum, M.; Ronald, P.; Dow, M.A.X.; Verdier, V.; Beer, S.V.; Machado, M.A.; et al. Top 10 plant pathogenic bacteria in molecular plant pathology. Molecular Plant Pathology 2012, 13, 614–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.N.; Callow, J.A. Multiplication and spread of pathovars of Xanthomonas campestris in host and non-host plants. Plant Pathology 1986, 35, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).