Submitted:

20 November 2024

Posted:

26 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Warehouse Performance Indicators

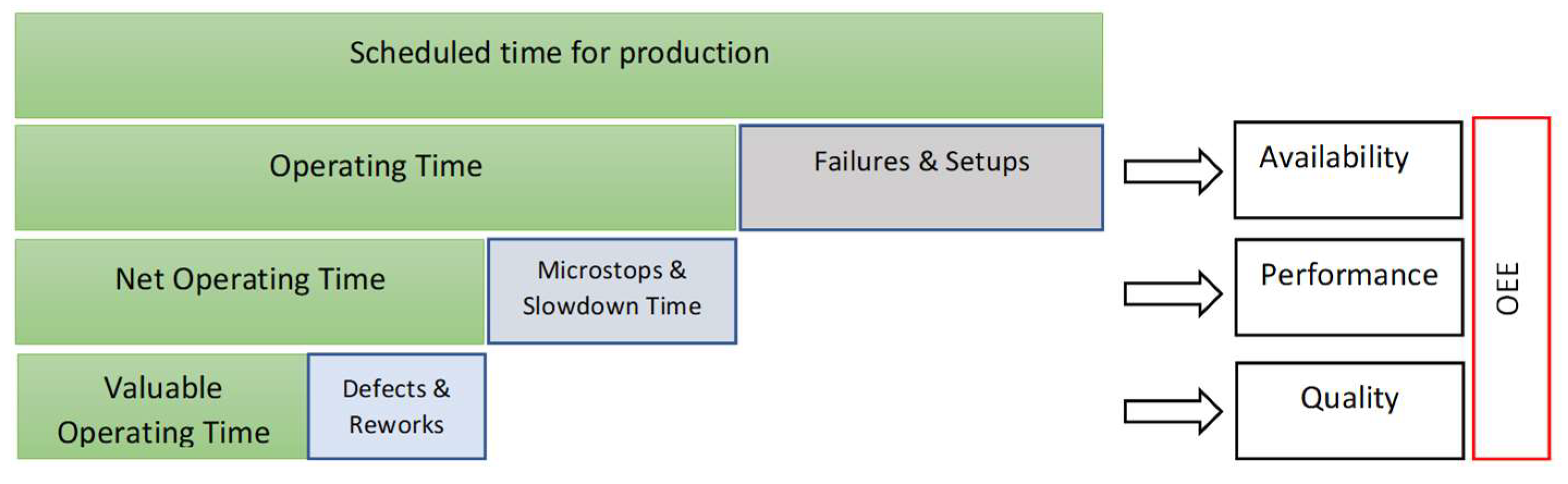

2.2. Overall Equipment Effectiveness (OEE)

2.2.1. Definition

- availability,

- process performance,

- quality rate

2.2.2. Variations of the OEE in Manufacturing Contexts

2.2.3. Applications of the OEE in Logistics

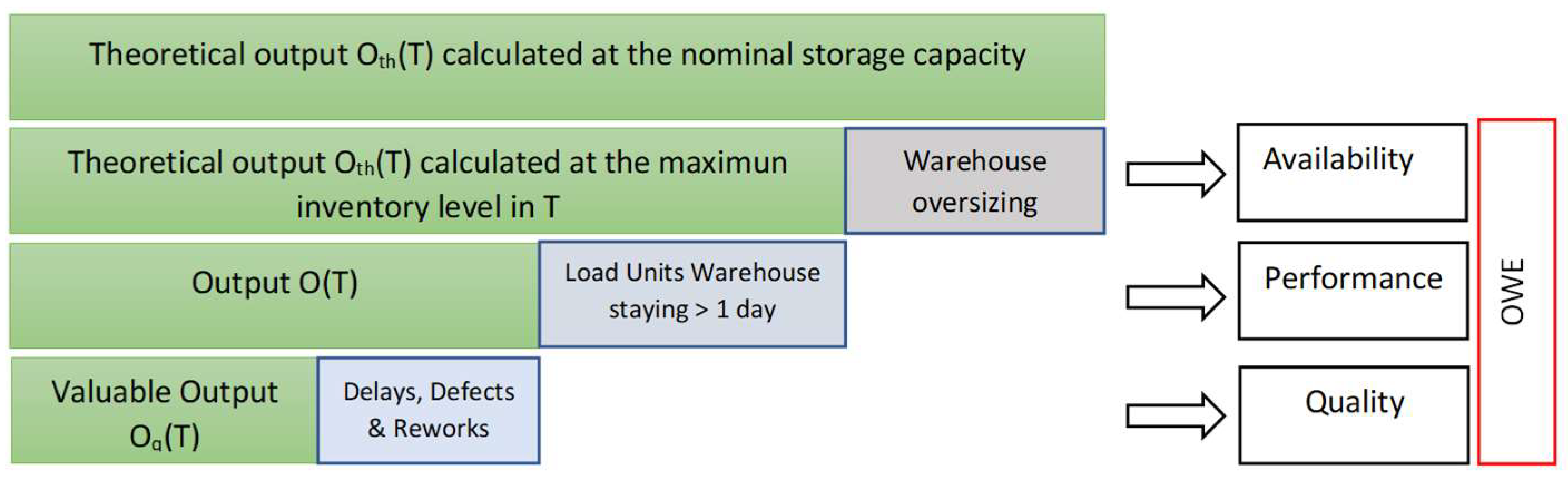

3. OWE: A New, Encompassing Warehouse KPI

3.1. Research Approach

- Process resources: resources involved in the production cycle.

- Logistics resources: resources that intervene during the storage and transportation of raw materials, semi-finished and finished products.

3.2. Mathematical Formulations

- input of goods (INPUT)

- time of use of the resource, T

- output of the goods (OUTPUT)

- the analysis has a time bucket t equal to one day, meaning that each UL has a minimum theoretical stay in the warehouse equal to one day, but nothing prevents choosing time buckets of a shorter duration.

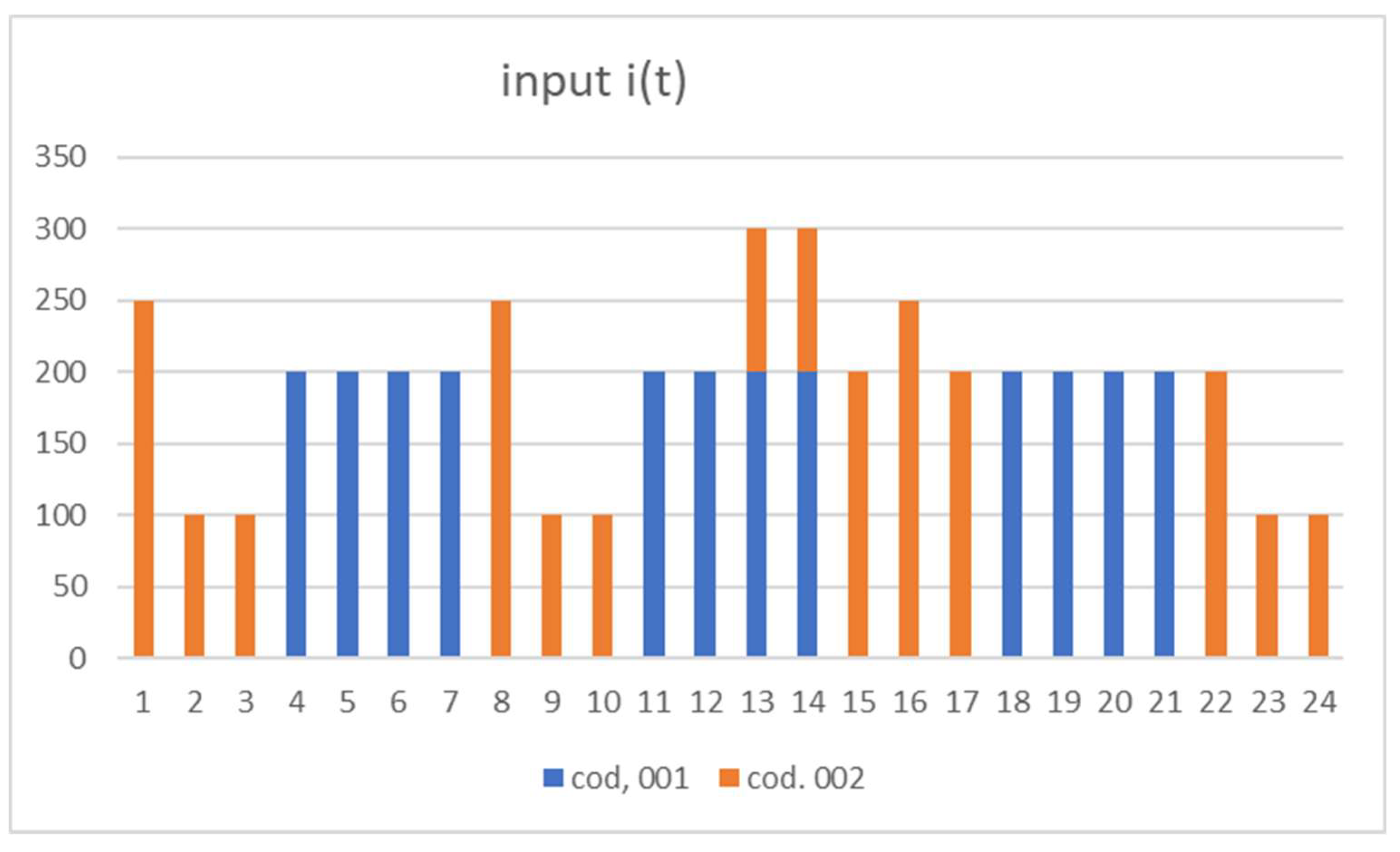

- i(t) is the input function in time bucket t and is defined in the interval 1 ≤ t ≤ T with t = 1, 2 , ..., T.

- o(t) is the output function in time bucket t and is defined in the interval 1 ≤ t ≤ T with t = 1, 2 , ..., T.

- There is an equivalence between ULs and storage locations, whereby each storage location holds only one UL.

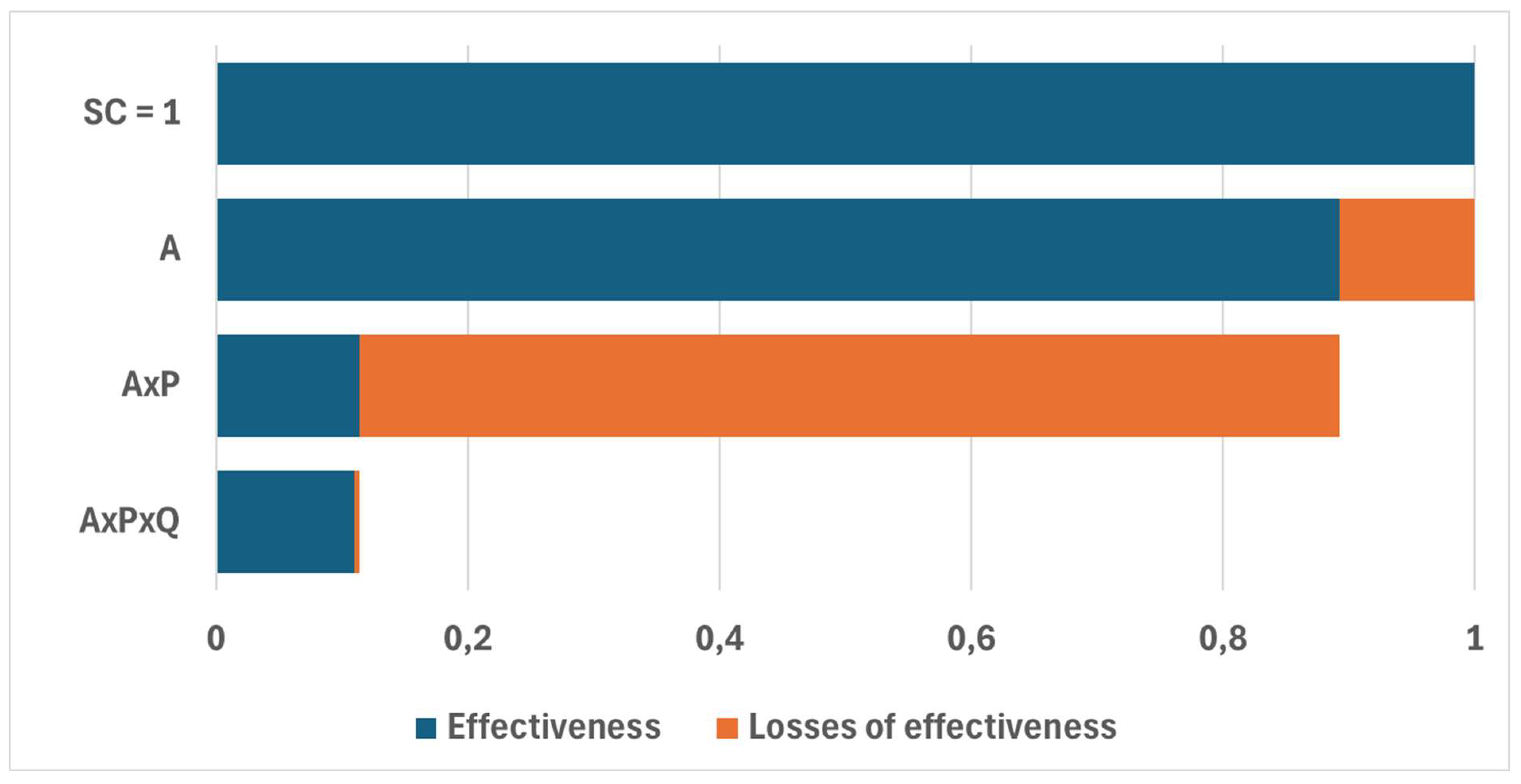

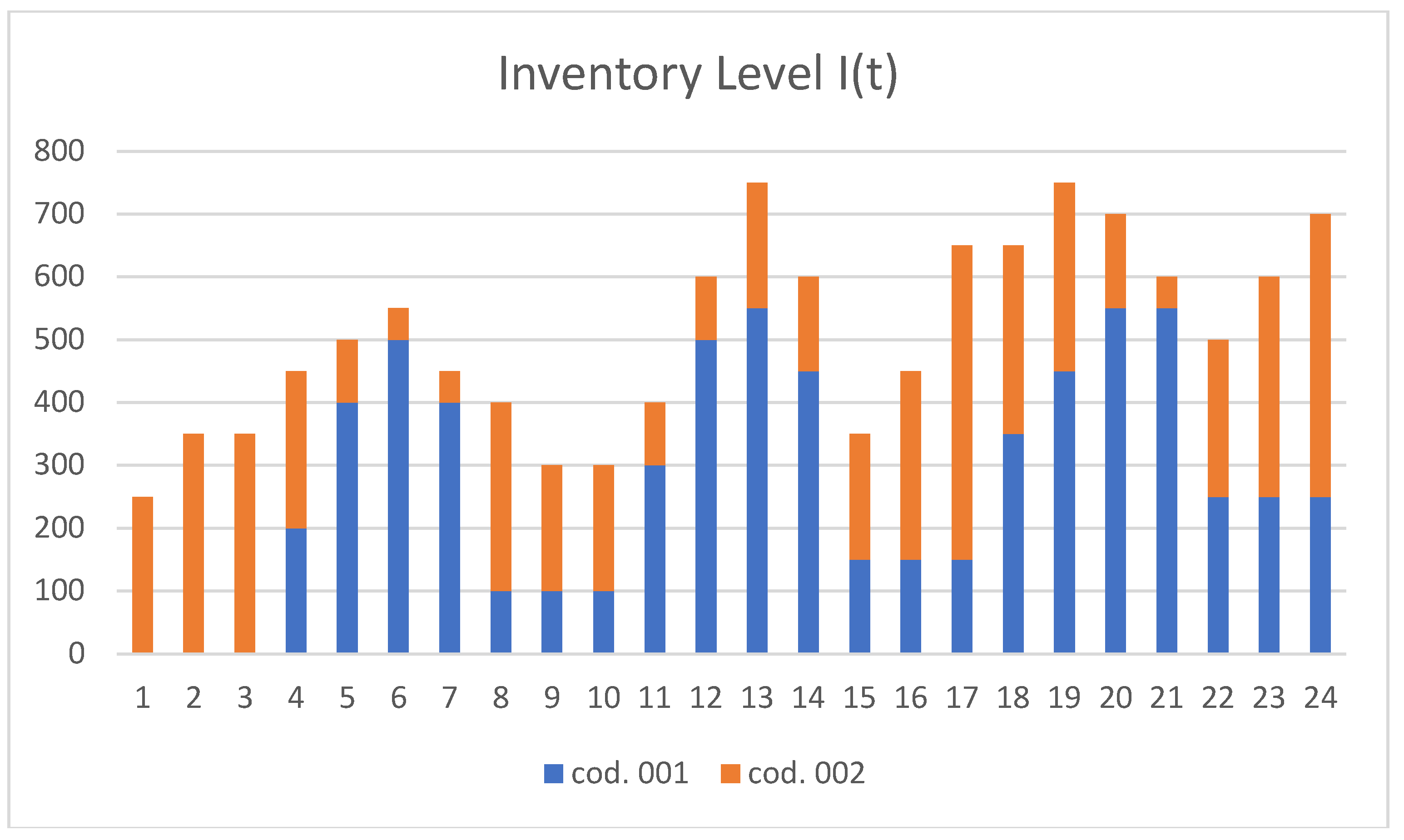

3.2.1. Availability

- Oth.max (T,Imax): maximum theoretical output needed to handle Imax, which is equal to Imax * T.

- Oth.max (T,SC): maximum theoretical output needed to handle the whole storage capacity, which is equal to SC*T.

3.2.2. Performance

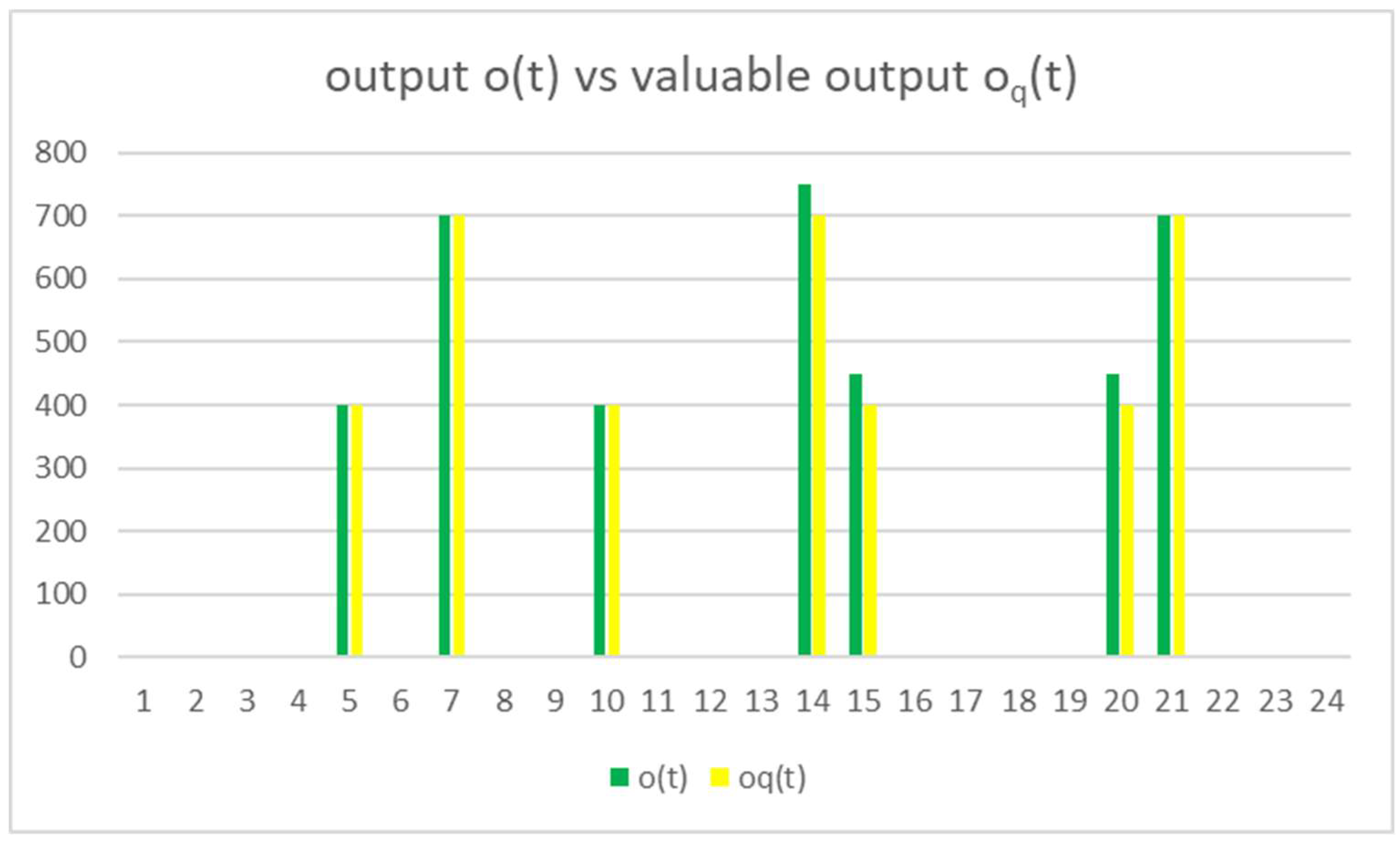

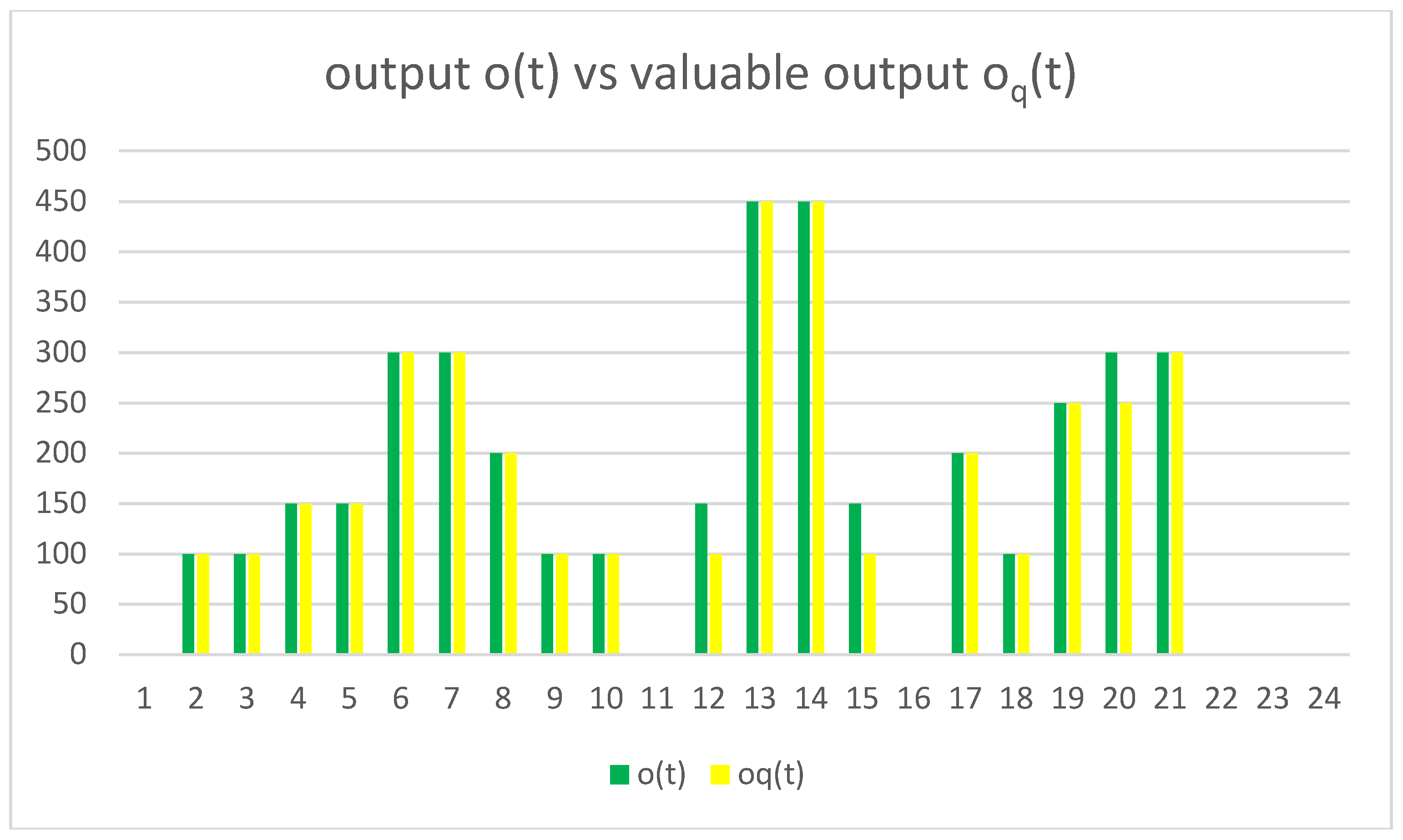

3.2.3. Quality

4. Case Study Application

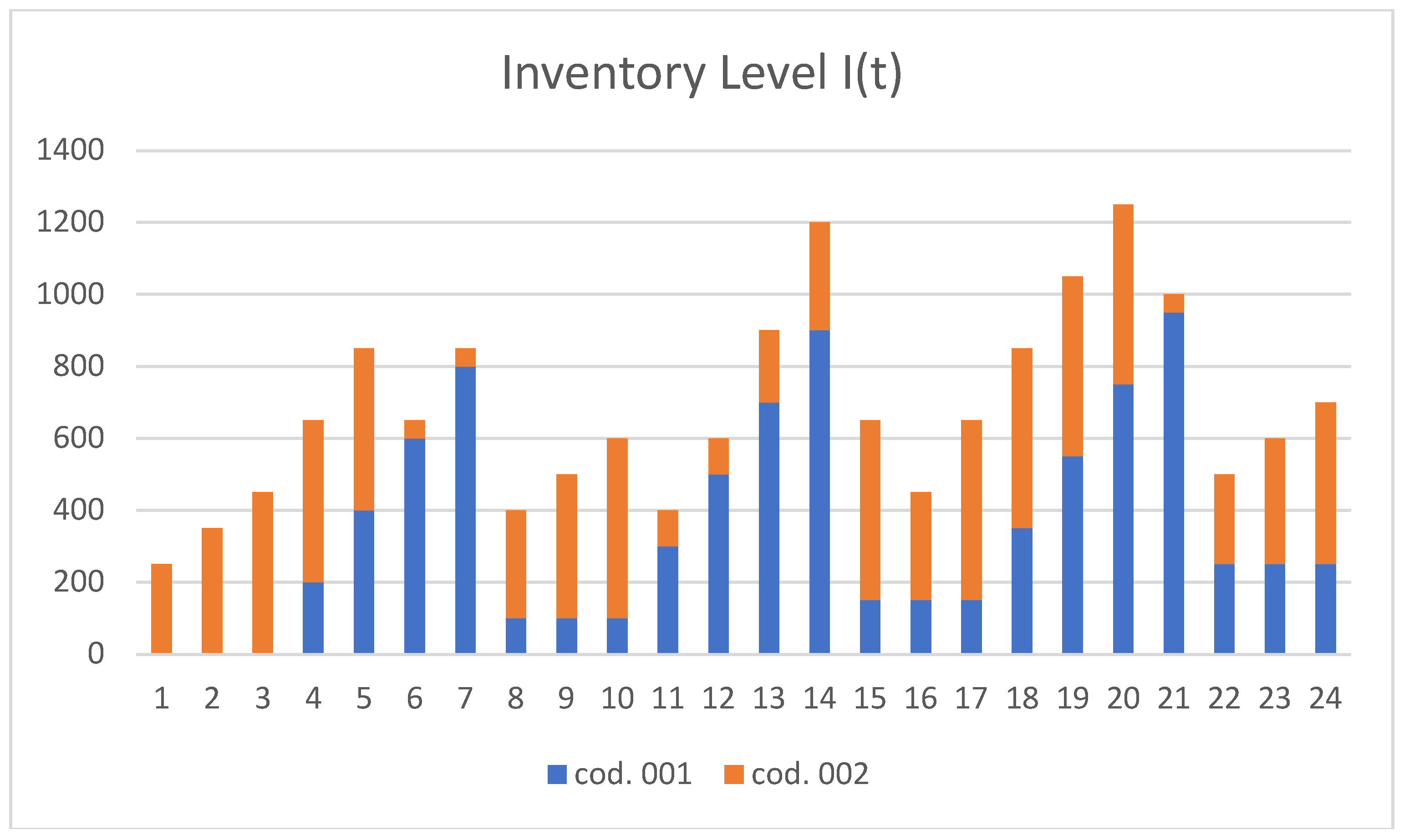

- The warehouse has a Storage Capacity of 1,400 locations.

- The input is considered concentrated at the beginning of the elementary unit of time and is realized in LUs.

- The output is considered concentrated at the end of the elementary time unit and is realized in LUs.

- The handling capacity is such that the input and output are realized.

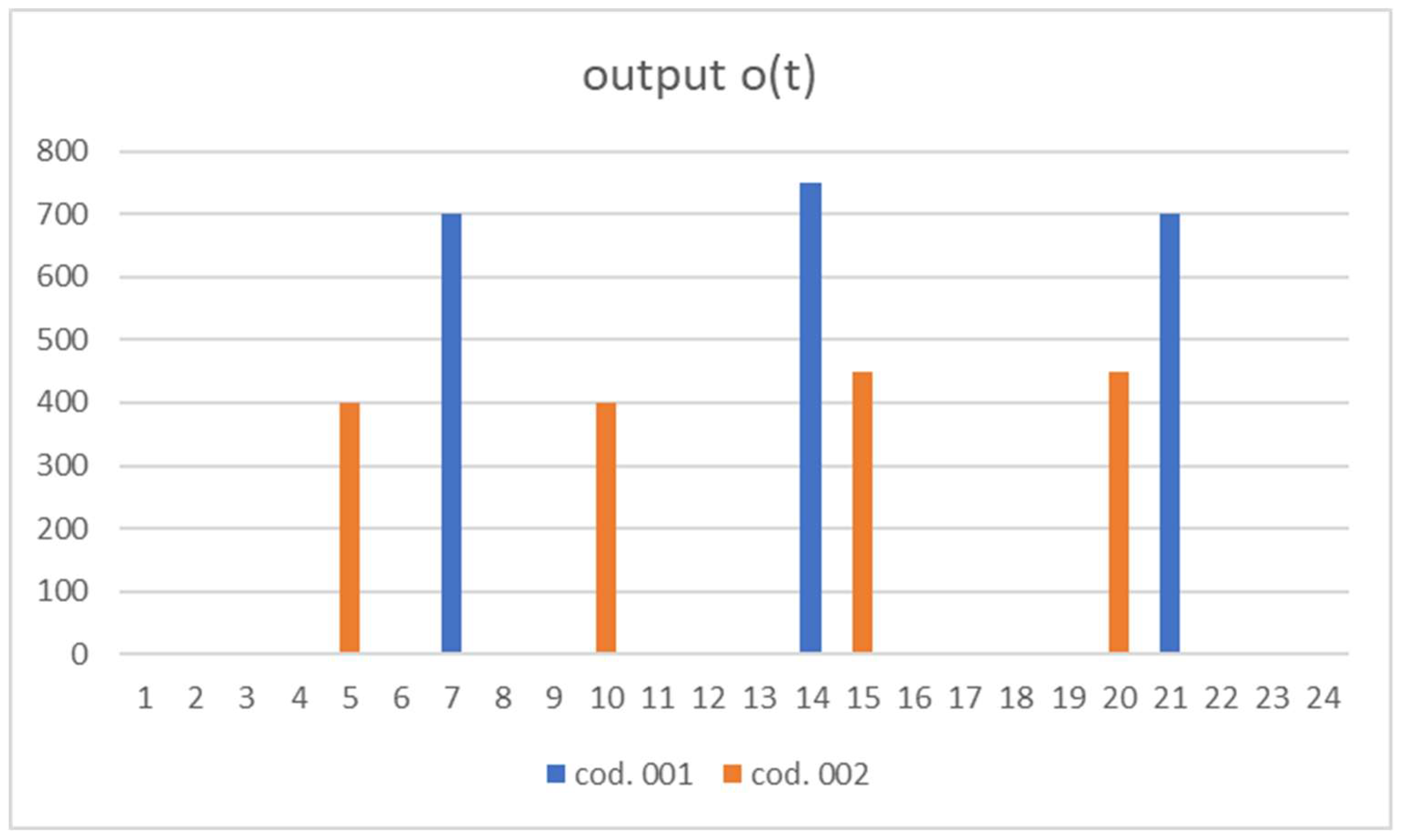

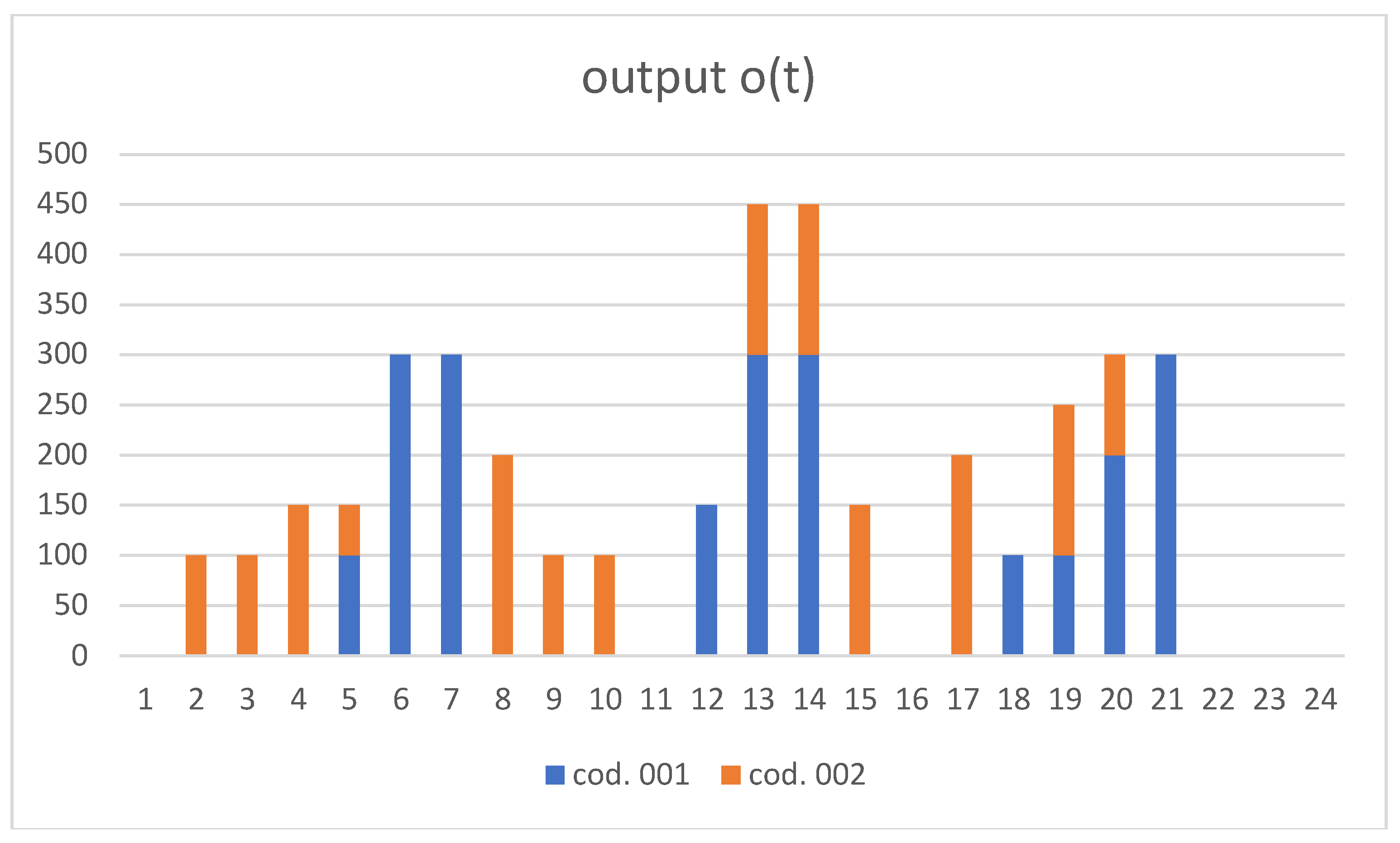

- For product 1 (cod 001), the output (1) is equal to 2,150 LUs in T.

- For product 2 (cod 002) the output (2) is equal to 1,700 LUs in T.

- The total output O(T) is 3,850 LUs in T.

4.1. Demand Scenario 1

- for product 1, in period 14 there was an amount of unfulfilled equal to 50 ULs.

- for product 2, in periods 15 and 20 there was an amount of unfulfilled equal to 50 LUs for a total of 100 undelivered products.

4.2. Demand Scenario 2

- the modification of the parameters A(T) and P(T)

- the same value of the OWE

- for product 1, in period 12 there was an amount of unfulfilled equal to 50 LUs.

- for product 2, in periods 15 and 20 there was an amount of unfulfilled equal to 50 LUs for a total of 100 undelivered products.

4.3. Analysis of Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Practical Implications

- Is the service level rendered to the customer sufficient?

- Is the stock and inventory management policy efficient?

- Is the physical warehouse being used introducing “waste” into the logistics process?

- The number of units that you are unable to deliver to customers.

- The low performance of inventory management policies.

- The under or over sizing of the warehouse, also in the case of automated warehouses, the too high number of system failures.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wong, W.P.; Soh, K.L.; Chong, C.L.; Karia, N. Logistics Firms Performance: Efficiency and Effectiveness Perspectives. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management 2015, 64, 686–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W. Logistics Network Structure and Design for a Closed-Loop Supply Chain in e-Commerce. IJBPM 2005, 7, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, N.H.; Abdul Rahman, N.S.F.; Md Hanafiah, R.; Abdul Hamid, S.; Ismail, A.; Abd Kader, A.S.; Muda, M.S. Revising the Warehouse Productivity Measurement Indicators: Ratio-Based Benchmark. Maritime Business Review 2021, 6, 49–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Prashar, A. Linking Resource Bundling and Logistics Capability with Performance: Study on 3PL Providers in India. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goshu, Y.Y.; Kitaw, D. Performance Measurement and Its Recent Challenge: A Literature Review. IJBPM 2017, 18, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachiappan, R.; Anantharaman, N. Evaluation of Overall Line Effectiveness (OLE) in a Continuous Product Line Manufacturing System. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonmez, V.; Testik, M.C. Using Accurately Measured Production Amounts to Obtain Calibration Curve Corrections of Production Line Speed and Stoppage Duration Consisting of Measurement Errors. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2017, 88, 3257–3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laosirihongthong, T.; Adebanjo, D.; Samaranayake, P.; Subramanian, N.; Boon-itt, S. Prioritizing Warehouse Performance Measures in Contemporary Supply Chains. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staudt, F.H.; Alpan, G.; Di Mascolo, M.; Rodriguez, C.M.T. Warehouse Performance Measurement: A Literature Review. International Journal of Production Research 2015, 53, 5524–5544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, S. Introduction to TPM: Total Productive Maintenance. Productivity Press, Inc., 1988, 1988, 129.

- Saleem, F.; Nisar, S.; Khan, M.A.; Khan, S.Z.; Sheikh, M.A. Overall Equipment Effectiveness of Tyre Curing Press: A Case Study. Journal of quality in maintenance engineering 2017, 23, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhetre, R.; Dhake, R. TPM Review and OEE Measurement in a Fabricated Parts Manufacturing Company. International Journal of Research in Engineering Applied Sciences 2012, 2, 1084–1094. [Google Scholar]

- Schiraldi, M.M.; Varisco, M. Overall Equipment Effectiveness: Consistency of ISO Standard with Literature. Computers Industrial Engineering 2020, 145, 106518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.H.; Dismukes, J.P.; Shi, J.; Su, Q.; Razzak, M.A.; Bodhale, R.; Robinson, D.E. Manufacturing Productivity Improvement Using Effectiveness Metrics and Simulation Analysis. International journal of production research 2003, 41, 513–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anvari, F.; Edwards, R.; Starr, A. Evaluation of Overall Equipment Effectiveness Based on Market. Journal of Quality in Maintenance Engineering 2010, 16, 256–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åhrén, T.; Parida, A. Overall Railway Infrastructure Effectiveness (ORIE): A Case Study on the Swedish Rail Network. journal of quality in maintenance engineering 2009, 15, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal, B.; Tugwell, P.; Greatbanks, R. Overall Equipment Effectiveness as a Measure of Operational Improvement–a Practical Analysis. International Journal of Operations Production Management 2000, 20, 1488–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsarouhas, P. Implementation of Total Productive Maintenance in Food Industry: A Case Study. Journal of Quality in Maintenance Engineering 2007, 13, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsarouhas, P. Equipment Performance Evaluation in a Production Plant of Traditional Italian Cheese. International Journal of Production Research 2013, 51, 5897–5907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foit, K.; Gołda, G.; Kampa, A. Integration and Evaluation of Intra-Logistics Processes in Flexible Production Systems Based on OEE Metrics, with the Use of Computer Modelling and Simulation of AGVs. Processes 2020, 8, 1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Villamizar, A.; Santos, J.; Montoya-Torres, J.R.; Jaca, C. Using OEE to Evaluate the Effectiveness of Urban Freight Transportation Systems: A Case Study. International Journal of Production Economics 2018, 197, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Rahman, N.S.F.; Karim, N.H.; Md Hanafiah, R.; Abdul Hamid, S.; Mohammed, A. Decision Analysis of Warehouse Productivity Performance Indicators to Enhance Logistics Operational Efficiency. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management 2023, 72, 962–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusrini, E.; Novendri, F.; Helia, V.N. Determining Key Performance Indicators for Warehouse Performance Measurement–a Case Study in Construction Materials Warehouse.; EDP Sciences, 2018; Vol. 154, p. 01058. [CrossRef]

- Frazelle, E. Supply Chain Strategy: The Logistics of Supply Chain Management; MCGraw-Hill Education, 2002; ISBN 0-07-137599-6.

- Kiefer, A.W.; Novack, R.A. An Empirical Analysis of Warehouse Measurement Systems in the Context of Supply Chain Implementation. Transportation journal 1999, 38, 18–27. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, G. Warehouse Management: A Complete Guide to Improving Efficiency and Minimizing Costs in the Modern Warehouse; Kogan Page Publishers, 2017; ISBN 0-7494-7978-7.

- Wang, H.; Chen, S.; Xie, Y. An RFID-Based Digital Warehouse Management System in the Tobacco Industry: A Case Study. International Journal of Production Research 2010, 48, 2513–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, T. Manufacturing Flexible Packaging: Materials, Machinery, and Techniques; William Andrew, 2014; ISBN 0-323-26505-7.

- De Groote, P. Maintenance Performance Analysis: A Practical Approach. Journal of Quality in Maintenance Engineering 1995, 1, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.; Pisa, R. Can Overall Factory Effectiveness Prolong Mooer’s Law? Solid state technology 1998, 41, 75–81. [Google Scholar]

- Garza-Reyes, J.A. From Measuring Overall Equipment Effectiveness (OEE) to Overall Resource Effectiveness (ORE). Journal of Quality in Maintenance Engineering 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muchiri, P.; Pintelon, L. Performance Measurement Using Overall Equipment Effectiveness (OEE): Literature Review and Practical Application Discussion. International journal of production research 2008, 46, 3517–3535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afy-Shararah, M.; Rich, N. Operations Flow Effectiveness: A Systems Approach to Measuring Flow Performance. International Journal of Operations Production Management 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braglia, M.; Castellano, D.; Frosolini, M.; Gallo, M. Overall Material Usage Effectiveness (OME): A Structured Indicator to Measure the Effective Material Usage within Manufacturing Processes. Production Planning Control 2018, 29, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, R.; Aguado, S. Overall Environmental Equipment Effectiveness as a Metric of a Lean and Green Manufacturing System. Sustainability 2015, 7, 9031–9047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Villamizar, A.; Santos, J.; Montoya-Torres, J.R.; Ormazábal, M. Environmental Assessment Using a Lean Based Tool. Service Orientation in Holonic and Multi-Agent Manufacturing: Proceedings of SOHOMA 2017 2018, 41–50.

- Butlewski, M.; Dahlke, G.; Drzewiecka-Dahlke, M.; Górny, A.; Pacholski, L. Implementation of TPM Methodology in Worker Fatigue Management-a Macroergonomic Approach.; Springer, 2018; pp. 32–41.

- Puvanasvaran, P.; Teoh, Y.S.; Ito, T. Novel Availability and Performance Ratio for Internal Transportation and Manufacturing Processes in Job Shop Company. Journal of Industrial Engineering and Management 2020, 13, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamali, A. IoT’s Potential to Measure Performance of MHE in Warehousing. Int. J. Biom. Bioinform 2019, 11, 93–99. [Google Scholar]

- Hackman, S.T.; Frazelle, E.H.; Griffin, P.M.; Griffin, S.O.; Vlasta, D.A. Benchmarking Warehousing and Distribution Operations: An Input-Output Approach. Journal of Productivity Analysis 2001, 16, 79–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kłodawski, M.; Jacyna, M.; Lewczuk, K.; Wasiak, M. The Issues of Selection Warehouse Process Strategies. Procedia Engineering 2017, 187, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gräßler, I.; Pöhler, A. Implementation of an Adapted Holonic Production Architecture. Procedia Cirp 2017, 63, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrillo, A.; De Felice, F.; Zomparelli, F. Performance Measurement for World-Class Manufacturing: A Model for the Italian Automotive Industry. Total Quality Management Business Excellence 2019, 30, 908–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanchanasevee, P.; Biswas, G.; Kawamura, K.; Tamura, S. Contract-Net-Based Scheduling for Holonic Manufacturing Systems.; SPIE, 1997; Vol. 3203, pp. 108–115. [CrossRef]

- Kotak, D.; Wu, S.; Fleetwood, M.; Tamoto, H. Agent-Based Holonic Design and Operations Environment for Distributed Manufacturing. Computers in Industry 2003, 52, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Metric | Equation | Variation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Factory Effectiveness (OFE) | Relationships among different machines and processes | [30] | |

| Overall Asset Effectiveness (OAE) | Losses due to business-related and other non-operationally related causes | [32] | |

| Overall Resources Effectiveness (ORE) | Manufacturing performance measurement system | [31] | |

| Overall Environmental Equipment Effectiveness (OEEE) | Concept of sustainability based on the calculated environmental impact | [35] | |

| Operations Flow Effectiveness (OFE) | Holistic view of material flow through the input-process-output cycles of a firm | [33] | |

| Overall Greenness Performance (OGP) | Environmental hierarchy of metrics according to Va (Value adding) processes | [36] | |

| Overall material usage effectiveness (OME) | Measure the effective material usage within manufacturing processes | [34] | |

| Operations Labour Effectiveness (OLE) | Improvement in safety and fatigue management | [37] |

| KPI | Availability | Process performance | Quality rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| OEE | Ability of the resource to be actually available to produce compared to the production schedule. (1 bis) |

Actual capacity that the resource can exert to generate value compared to the capacity that is assigned to it in the process design phase. (2 bis) | Ability of the resource to produce compliant parts. (3 bis) |

| OWE | Ability of the resource to be effectively available to maintain goods with respect to the actual planning of input and output flows. | Ability of the resource to maintain assets efficiently and taking into account the actual planning of input and output flows, this ability is expressed by comparison with ideal cases | Ability of the resource to make intact products available to the customer with complete and timely deliveries |

| OWE parameter | Objective |

|---|---|

| Availability | Warehouse planning allows undersized or oversized warehouses to be identified. It also takes into account the actual availability of compartments. |

| Performance | Effectiveness of stock management policies, taking into account the scheduling of Input and Output flows and stock levels. In addition, it enables to evaluate the different asset allocation criteria from a ‘static’ warehouse point of view. |

| Quality | Congruity of Flow Output with Demand, allows the correct sizing of the operating and safety stock to be verified |

| Variable | Definition |

|---|---|

| T | Reference time interval in which the analysis is carried out |

| Storage Capacity (SC) | Storage capacity of the warehouse under analysis, equals the number of available storage locations. |

| Imax(T) | Maximum inventory occurring in the warehouse during the analysis interval T. This value is calculated at the end of T. |

| O(T) | Output or outflow from the warehouse at T, the management of which within the warehouse gives rise to Imax(T). This value is taken at the end of T. |

| Oth,max(T) | The maximum theoretical output or outflow that can be managed in the interval T in a warehouse considering different amount of storage locations occupied. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).